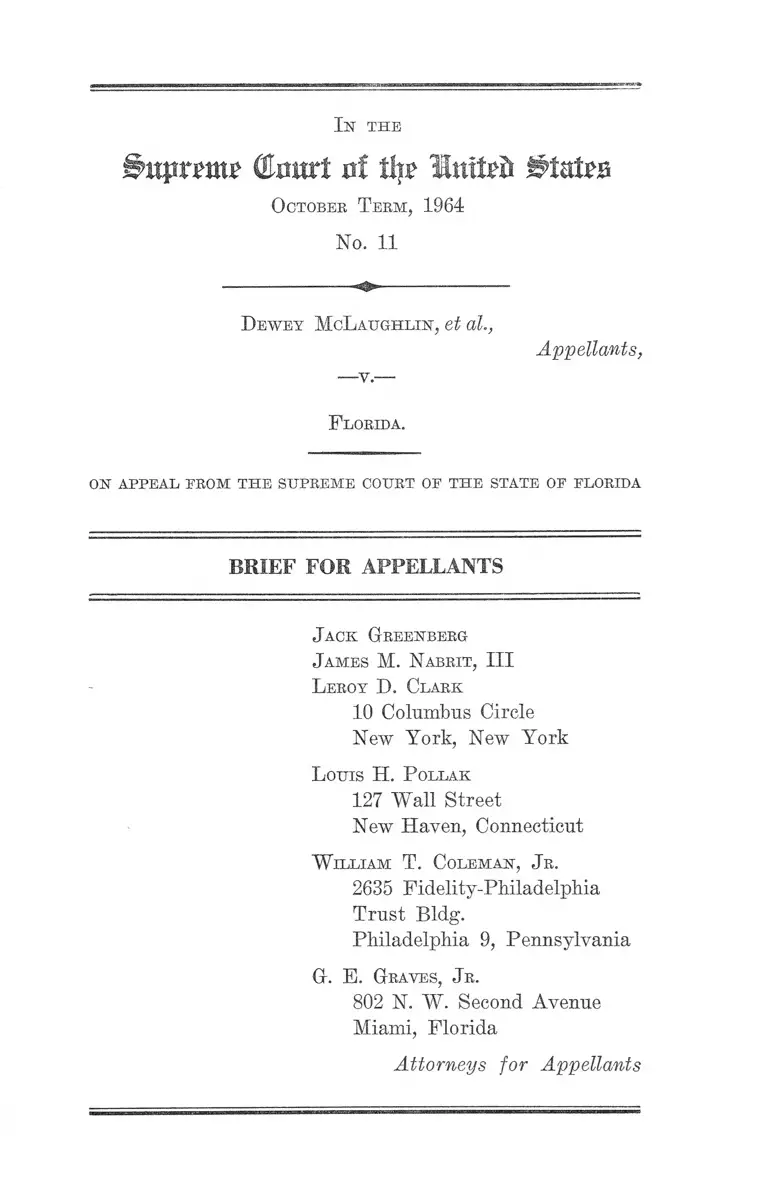

McLaughlin v. Florida Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McLaughlin v. Florida Brief for Appellants, 1964. 43287a69-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ddcebdf8-2467-45a4-b074-a4cd3292a557/mclaughlin-v-florida-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

I k t h e

(Emtrt ni % ImW

October T eem, 1964

No. 11

D ewey McL aughlik, et al.,

Appellants,

F lorida.

OK APPEAL EEOM THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF FLOEIDA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ack Greekberg

J ames M. Nabeit, III

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Louis H. P ollak

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut

W illiam T. Colemak, Je.

2635 Fidelity-Philadelphia

Trust Bldg.

Philadelphia 9, Pennsylvania

G. E. Graves, Je.

802 N. W. Second Avenue

Miami, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinion Below ............... ...................... ........ ............. -....... - 1

Jurisdiction ..............................................- .......................... 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved------ 2

Questions Presented ...................................-....... —- —- 4

Statement ..................................- .....................................—- 4

Summary of Argument ....................................... -.....-...... - 7

A bgxjment :

I. Appellants Were Convicted Under a Law

Which Makes Race an Element of the Crime,

Punishing a Negro and a White Person for

Acts Not Prohibited When Done by Persons

of the Same Race, and Thus Violates the Due

Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment ....... ............. ........... - 9

II. Appellants Were Denied Rights Under the

Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment by Florida’s Mis

cegenation Laws Which Had the Effect of

Requiring the Jury to Disregard Evidence of

a Common Law Marriage If It Decided That

One Appellant Was White and That the

Other Was Negro .................................... .......... 15

III. Appellants Were Denied Due Process Be

cause Either There Was No Proof of Their

Race or Florida’s Racial Definition Is Vague 27

11

PAGE

Conclusion .......................................................................... 31

A ppendix :

States Repealing Miscegenation Laws in Recent

Years .......................................................................... la

States Repealing Miscegenation Laws in Last Cen

tury ............................................................................ 2a

States Never Enacting Statutes Which Prohibit

Interracial Marriage ............................................... 2a

States at Present Prohibiting Interracial Mar

riages ......... 3a

Table op Cases

Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U. S. 203 .... 13

Anderson v. Martin, 379 U. S. 399 ...................................12, 26

Bell v. Maryland,'------ U. S .------- , 12 L. ed. 2d 822 ....... 25

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ........ ............................ 12

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ....12,13,14, 25

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ................... 8,12,13,14, 26

Burns v. State, 48 Ala. 195 (1872) ...............................24, 26

Callen v. Florida, 94 So. 2d 603 (Fla. 1957) ....... ........... 11

Campbell v. State, 92 Fla. 775, 109 So. 809 (1926) ....... 18

Chaachou v. Chaachou, 73 So. 2d 830 (Fla. 1954) ____ 16

Cloud v. State, 64 Fla. 237, 60 So. 180 (1912) ............... 11

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U. S. 385 .... 30

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ......................... ..................... 25

Dorsey v. State Athletic Commission, 168 F. Supp. 149

(E. D. La. 1958), aff’d 359 IT. S. 533

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160 ...

13

13

Ill

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903, affirming, 142 F. Supp.

PAGE

707 (M. T). Ala. 1956) ..... ....... ....... ....................... 13,14, 26

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565 ............ ................ 13

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683 .......13,14, 25, 26

Green v. State, 58 Ala. 190 (1877) ......... ....... ............. . 24

Grice v. State, 76 Fla. 751, 78 So. 984 (1914) ............... 12

Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U. S. 650 ............................... 12

Hill v. United States ex rel. Weiner, 300 U. S. 105....... 14

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81 .... .............. 12

Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879, reversing 223 F. 2d

93 (5th Cir. 1955) ........... ................ ............ -----............ 13

Jackson v. Alabama, 348 U. S. 888 ....... ................ -......... 18

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 6 1 ............. ................. ....13, 26

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214----------------12, 20

Langford v. State, 124 Fla. 428,168 So. 528 (1936) ------ 11

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U. S. 451 ...... ...... ......... —. 30

LeBlanc v. Yawn, 99 Fla. 467, 126 So. 789 (1930) ____ 17

Lewis v. State, 53 So. 2d 707 (Fla. 1951) .................... 18

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267 --------- -------------13, 26

Lonas v. State, 50 Tenn. 287 (1871) .................... ......... 20

Luster v. State, 23 Fla. 339, 2 So. 690 (1887) ............... 11

Malloy v. Hogan,------ U. S .------- , 12 L. ed. 2d 653 ------ 18

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390 .................... ............ . 19

Missouri Pacific Railway Co. v. Kansas, 248 U. S. 276 25

Moore v. Missouri, 159 U. S. 673 ......... ............... ......... 14

Naim v. Naim, 350 U. S. 891, app. dismissed 350 U. S.

985 ................ .............. .............. ................ -....... - ............ 18

National Prohibition Cases, 253 U. S. 350 ...... .............. 25

Navarro, Inc. v. Baker, 54 So. 2d 59 (Fla. 1951) ........ 16

Orr v. State, 129 Fla. 398, 176 So. 510 (1937) ------------ 18

IV

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U. S. 583 ....... ............... 7, 8,13,14,18

Parramore v. State, 81 Fla. 621, 88 So. 472 (1921) ....... 10

Penton v. State, 42 Fla. 560, 28 So. 774 (1900) ............ 11

Perez v. Lippold, 32 Cal. 2d 711,198 P. 2d 17 (1948) ....19, 21,

26

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244 ..... ............. 8,13,14, 26

Pinson v. State, 28 Fla. 735, 9 So. 706 (1891) _______ 11

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 .... ........... ................ 13, 20

Scott v. Georgia, 39 Ga. 321 (1869) ...... ........ ....... ........... 21

Scott v. Sanford, 19 How. 393 ........................................... 24

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ......... .......... .................. 14, 26

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535 ...... ....... ....... ........ 19

State v. Jackson, 80 Mo. 175 (1883) ........... ................... 21

State v. Pass, 59 Ariz. 16, 121 F. 2d 882 (1942) ........... 20

Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192............... 13

Thomas v. State, 39 Fla. 437, 22 So. 725 (1897) ........ . 11

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199 ............. ............. 28

Thompson’s Estate, In re, 145 Fla. 42, 199 So. 352

(1940) .............................. ............ ......... ........................... 17

Wall v. Altbello, 49 So. 2d 532 (Fla. 1950) ................... 25

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 ........ ............... .......... 26

Whitehead v. State, 48 Fla. 64, 37 So. 302 (1904) ____ 11

Wildman v. State, 157 Fla. 334, 25 So. 2d 808 (1946) ....10,11

Williams v. Bruffy, 96 U. S. 176 ....................................... 2

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 ........... .................. .... 13, 26

Statutes

Ala. Code, 1940, §301(31c) ................. .................. .......... 14

Fla. Act. Jan. 23, 1832, §§1, 2 ........................................... 25

F. S. A. Constitution, Declaration of Rights, §12........... 18

F. S. A. Constitution, Art. 16, §24 ...............................2, 8,15

F. S. A. §731.29 .................................................................... 25

F. S. A. §741.11..... .....................................................3, 8,15, 25

PAGE

Y

F. S. A. §741.12 ..............

Fla. Stat. Anno., §741.13

Fla, Stat. Anno., §741.14 .

Fla. Stat. Anno., §741.15 .

Fla. Stat. Anno., §741.16

F. S. A. §1.01(6) - .... .......

F. S. A. §798.01 ................

F. S. A. §798.02 ________

F. S. A. §798.03 ............. .

F. S. A. §798.04 ________

F. S. A. §798.05 ...............

S. C. Code, 1952, §5377 ...

28 U. S. C. §1257(2) ........

42 U. S. C. §1981......... .

....................3, 8,15

........................ 16

............. .......... 16

....................... 16

.............. ........ . 16

........3, 8, 27, 28, 29

________ ____ 12

_______________________ _____ . 11,12

...................... 11,13

........ ......... ..... 11

1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9,10,

11,12,13,15, 27

............... 14

......... ............ . 2

........................ 26

PAGE

Other A uthorities

Beals and Hoijer, An Introduction to Anthropology

(1953) .................................................................... -.......... 23

46 Cong. Globe, part 4, p. 3042 (39th Cong., 1st Sess.) .. 25

Dobzhansky, “ The Bace Concept in Biology,” The Sci

entific Monthly, LII (Feb. 1941) ................................... 21

Hankins, The Racial Basis of Civilization (1926) ....... 23

Kroeber, Anthropology (1948) ~........ .......... —-....... 23

Montague, An Introduction to Physical Anthropology

(1951) .............. ................. -....... -...................... -............. - 23

Montague, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy

of Race (4th ed. 1964) ...... - ................. 21, 22, 23, 29

Note, 58 Tale L. J. 472 (1949) ......... .... ............................ 22

Note, “ Bights of Illegitimates Under Federal Stat

utes,” 76 Harv. L. Bev. 337 (1962) ..... .................. ...... 25

VI

PAGE

Rand-McNally, Cosmopolitan World Atlas ................... 29

UNESCO, “ Statement on the Nature of Race and Race

Differences—by Physical Anthropologists and Genet

icists, September 1952” ................................................. 22

Weinbnrger, “ A Reappraisal of the Constitutionality of

Miscegenation Statutes,” 42 Cornell L. Q. 208 (1957) 22

Yerkes, “ Psychological Examining in the U. S. Army”,

15 Mem. Nat. Acad. Sci. 705 (1921) ........................... 23

In t h e

^>uprmp Court of flir Inttef* ^fatro

October T erm, 1964

No. 11

Dewey McLaughlin, et al.,

Appellants,

F lorida.

ON APPEAL EROM THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Opinion Below

The Criminal Court of Record In and For Dade County,

Florida did not render an opinion. The opinion of the

Supreme Court of Florida is reported in 153 So. 2d 1

(1963) (R. 99).

Jurisdiction

Appellants were convicted in the Criminal Court of Rec

ord In and For Dade County, Florida, on June 24, 1962

of violating Florida Statutes Annotated §798.05. They ap

pealed to the Supreme Court of Florida, contending that

the convictions and the Florida laws involved violated the

equal protection and due process clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment. On May 1,1963, the Supreme Court of Florida

affirmed the convictions and decided in favor of the validity

of F. S. A. §798.05 under the Constitution of the United

2

States (R. 99). Petition for rehearing in the Supreme

Court of Florida was denied May 30, 1963 (R. 105).

Appellants filed Notice of Appeal in the Supreme Court

of Florida on August 29, 1963 (R. 106), and a Jurisdic

tional Statement in this Court, October 28, 1963. Probable

jurisdiction was noted April 27,1964 (377 II. S. 974). Juris

diction of this Court on appeal rests on 28 U. S. C. §1257(2).

Williams v. Bruffy, 96 U. S. 176, 182-184. Appellants, more

over raised substantial questions as to the constitutionality

of their convictions under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved

1. Petitioners were convicted of violating F. S. A.

§798.05 (Vol. 22, Title 44, p. 277) which provides:

§798.05—Negro man and white woman or white man

and negro woman occupying same room.

Any. negro man and white woman, or any white man

and negro woman, who are not married to each other,

who shall habitually live in and occupy in the night

time the same room shall each be punished by im

prisonment not exceeding twelve months, or by fine

not exceeding five hundred dollars.

2. This case also involves Fla. Const., Art. 16, §24 (Vol

ume 26A, p. 450) :

§24—Intermarriage of white persons and negroes pro

hibited.

All marriages between a white person and a negro, or

between a white person and a person of negro descent

to the fourth generation, inclusive, are hereby forever

prohibited.

3

3. F. S. A. §741.11 (Vol. 21A, Title 42, p. 58):

§741.11—Marriages between white and negro -persons

prohibited.

It is unlawful for any white male person residing or

being in this state to intermarry with any negro female

person; and it is in like manner unlawful for any white

female person residing or being in this state to inter

marry with any negro male person; and every marriage

formed or solemnized in contravention of the provi

sions of this section shall be utterly null and void, and

the issue, if any, of such surreptitious marriage shall

be regarded as bastard and incapable of having or re

ceiving any estate, real, personal or mixed, by inheri

tance.

4. F. S. A. §741.12 (Vol. 21A, Title 42, p. 59):

§741.12—Penalty for intermarriage of white and negro

persons.

If any white man shall intermarry with a negro, or if

any white woman shall intermarry with a negro, either

or both parties to such marriage shall be punished by

imprisonment in the state prison not exceeding ten

years, or by fine not exceeding one thousand dollars.

5. F. S. A. §1.01 (Vol. 1, Title 1, p. 124):

§1.01—Definitions.

. . . (6) The words “ negro” , “ colored” , “colored per

sons” , “ mulatto” or “ persons of color” , when applied

to persons, include every person having one-eighth or

more of African or negro blood.

6. This case also involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

4

Questions Presented

Whether the conviction of appellants violates the equal

protection and due process clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution, where:

(1) The State has created an offense, F. S. A. §798.05,

expressly defined in terms of race which punishes inter

racial couples for engaging in certain conduct while not

punishing such conduct by two persons of the same race?

(2) Appellants were denied a full jury consideration of

an ingredient of the crime, i.e. the absence of a common

law marriage, by jury instructions based on Florida’s laws

prohibiting Negroes and whites from marrying?

(3) There was either no evidence to satisfy Florida’s

racial definition in F. S. A. §1.01(6)—an essential part of

the crime created by F. S. A. §798.05— or the definition is

so vague and indefinite as to establish no standard of crimi

nality?

Statement

Appellants were arrested February 28, 1962 and charged

with having violated F. S. A. §798.05 in that “ the said

Dewey McLaughlin, being a Negro man, and the said Con

nie Hoffman, also known as Connie Gonzalez, being a white

woman, who were not married to each other, did habitually

live in and occupy in the nighttime the same room” (R. 3).

Appellants were convicted by a jury and each was sentenced

to thirty days in the County Jail at hard labor and fined

$150.00, plus costs, and in default of such payment to an

additional 30 day term (R. 7-9).

In April 1961, appellant Connie Hoffman began residing

in an “ efficiency” apartment at 732 Second Street, Miami

Beach, Florida (R. 22). The landlady testified that she

5

first saw appellant Dewey McLaughlin in either December,

1961 or February, 1962 (E. 23, 25). She questioned Connie

Hoffman about the identity of Mr. McLaughlin and was

told he was her husband (E. 3). Appellant Hoffman then

“ signed in” Mr. McLaughlin as her husband (E. 23). Mr.

McLaughlin, born in Honduras, but apparently an Ameri

can citizen, was then employed by a Miami Beach hotel

(E. 82).

The landlady claimed that appellants thereupon began

living together for a period of ten or twelve days (E. 24,

26). She stated that she observed McLaughlin showering

in the bathroom one evening, heard him talking to appel

lant Hoffman at 10:00 at night, and noticed his clothing

hanging in the apartment (E. 29, 30, 26). Moreover, she saw

him going in and out of the apartment during this period

(E. 29). Although she claimed to see McLaughlin enter the

apartment every evening, she was not certain that he in

fact remained there through the night (E. 26, 29, 30). Al

though she saw McLaughlin leave appellant Hoffman’s

apartment at least twice early in the morning, she asserted

that she did not know if he lived there every day during

this period (E. 26, 29, 30). Disturbed by the presence of

a colored man in her apartments, she reported the situation

to the police (E. 23).

Detectives Stanley Marcus and Nicolas Valeriana of

the Miami Beach Police Department went to Hoffman’s

apartment at 7 :15 p.m., February 23, 1962, to investigate a

charge of neglect of her minor son (E. 35, 44). They

knocked at the door and a man’s voice answered, “ Connie,

come in,” but the door was not opened (E. 51). Valeriana

went to the back of the apartment and found McLaughlin

leaving through the rear door (E. 70). In the questioning

which followed, McLaughlin admitted that he had been liv

ing there with Hoffman (E. 46) and that on one occasion

he had had sexual relations with her (E. 47). The detec

6

tives also observed a few pieces of McLaughlin’s wearing

apparel in the room (R. 45). Appellant Hoffman came to

the police station where McLaughlin was being held and

while there stated that she was living with him but thought

that this was not unlawful (R. 48). At trial Detective

Valeriana identified her as a white woman, using his “many

personal observations and experiences” as a standard (R.

59). On the basis of his “ factual contacts, experiences and

observations,” he characterized Dewey McLaughlin as a

Negro (R. 58, 65).

Joseph DeCesare, a secretary in the City Manager’s

Office, testified that while securing a civilian registration

card, McLaughlin stated in January 1961 that he “ was

separated and that his wife’s name was Willie McLaughlin”

(R. 74, 75). Dorothy Kaabe, a child welfare worker in

the Florida State Department of Public Welfare, testified

that in an interview on March 5, 1962, appellant Hoffman

stated that she began living with McLaughlin as her com

mon law husband in September or October 1961 (R. 83, 84).

March 1, 1963, an information was filed against appel

lants charging them with violating F. S. A. §798.05 (R. 3).

Motion to quash the information on grounds that it was

vague and deprived them of due process and equal pro

tection of the laws was denied (R. 5, 6). Motions for a

directed verdict arguing that F. S. A. §1.01(6) (defining

the term “ Negro” as used in F. S. A. §798.05) was vague

(R. 61) and that race remained unproven were made and

denied (R. 88-89).

The trial judge instructed the jury that in Florida a

Negro and a white person could not have been lawfully

married, either by common law or formal ceremony (R. 94).

Appellants were convicted by a jury and sentenced to

30 day jail terms and fines of $150 (R. 7-9).

7

A motion for new trial was filed alleging error in the

court’s failure to quash the information as a violation of

Fourteenth Amendment rights (E. 10, 11) and was denied

(R. 11).

On appeal to the Supreme Court of Florida appellants

assigned errors relying on the due process and equal pro

tection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment (R. 12).

The Court, in affirming the conviction, discussed only

F. S. A. §798.05 which it found constitutional in light of

Pace v. Alabama, 106 U. S. 583 (R. 99-102). Its jurisdic

tion derived from the trial court’s passing on the validity

of a state statute (R. 99).

In the Florida Supreme Court, appellant’s brief also

argued that the instruction to the jury on Florida’s mis

cegenation law contravened the Fourteenth Amendment

(Tr. of Record (on file in this Court) 180-183). The State

urged that miscegenation laws were constitutional and that

the instruction could only be harmless error (Tr. of Record

195-199). Appellants sought rehearing, attempting to se

cure the Florida Supreme Court’s discussion of this issue

(R. 102-103), but rehearing was denied without opinion

(R. 105).

Summary of Argument

I.

Appellants were convicted of a crime under an explicitly

racial Florida law, which punishes an interracial couple

for acts which are not prohibited if committed by persons

of the same race. No other Florida statute, including the

lewdness law (F. S. A. §798.02), contains the identical ele

ments of the crime defined in F. S. A. §798.05 used to con

vict petitioners. Florida has advanced no justification for

the racial distinctions made by this law. The racial clas

8

sification is unreasonable, and this Court should strike it

down as it has every other segregation law from Buchanan

v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 to Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S.

244. This case is different from Pace v. Alabama, 106 IT.' S.

583, but if the reasoning of Pace extends to cover this case,

Pace should be overruled as inconsistent with many sub

sequent decisions in this Court.

II.

The trial court’s jury instructions based on Florida’s laws

prohibiting interracial marriages (F. S. A. Const., Art. 16

§24; F. 8. A. §§741.11, 741.12) prevented the jury from

considering appellants’ possible common law marriage. The

jury instruction was not harmless since Florida recognizes

common law marriage, there was sufficient evidence to go

to the jury on the question, and the state had the burden

of proving that appellants were not married to each other.

The states have power to control many aspects of mar

riage, but no power to prohibit marriage on the basis of

irrational discriminations. Florida has advanced no reason

to support this racial distinction. Arguments advanced by

other states fly in the face of all scientific knowledge which

rejects the theories of “ pure races,” and Negro inferiority.

The miscegenation laws are relics of slavery based on race

prejudice. State enforcement of these laws violates the

Fourteenth Amendment for the same reasons that all segre

gation laws have been invalidated.

III.

To convict under F. S. A. §798.05 Florida had to prove

that McLaughlin was a “ Negro” (as defined in F. S. A.

§1.01(6)), and that Hoffman was “ white” (nowhere defined

in Florida law). The state made no effort to prove race by

reference to the Florida statutory definition (decreeing

9

that a Negro is a person with “ one-eighth or more of A fri

can or Negro blood” )- The definition is meaninglessly cir

cular and based on assumptions contrary to scientific fact.

If the definition is taken literally the conviction violates

due process, being based on no evidence of an element of

the offense. But Florida relied on an “ appearance” test,

sanctioned by the trial judge, using opinion testimony by a

policeman to prove race. The appearance test removes any

pretense of statutory clarity and depends entirely on vary

ing individual perceptions. This standard is far too vague

to support criminal convictions. The vagueness of legal

definitions of race vitiates crimes depending upon a per

son’s race.

A R G U M E N T

I.

Appellants Were Convicted Under a Law Which Makes

Race an Element of the Crime, Punishing a Negro and

a White Person for Acts Not Prohibited When Done by

Persons of the Same Race, and Thus Violates the Due

Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

The statute under which the appellants were prosecuted

and convicted, F. S. A. §798.05, proscribes the habitual

occupancy of a room by an interracial couple.1 As an osten

sible effort to restrain illicit sexual relations, the statute

might seem to fall within the state’s traditional power to

1 “ 798.05 Negro man and white woman or white man and Negro

woman occupying same room.

Any negro man and white woman, or any white man and

negro woman, who are not married to each other, who shall

habitually live in and occupy in the nighttime the same room

shall each be punished by imprisonment not exceeding twelve

months, or by fine not exceeding five hundred dollars.”

1 0

punish acts which affront public morality. Yet, the means

by which Florida purports to serve this goal violate the

Fourteenth Amendment by introducing a racial distinction

into the State’s criminal laws, by a statute in which sexual

relations are not even an element of the crime.

Section 798.05 defines a crime that can be committed

only by two persons of opposite sex, when one is Negro and

the other is white. Appellants submit that no Florida stat

ute punishes similar conduct by persons of the same race.

But Florida has argued that F. S. A. §798.05 covers the

same act which is punished irrespective of race by F. S. A.

§798.02 which prohibits (and provides a greater penalty

for) lewd and lascivious association and cohabitation.2 The

relevant Florida decisions, though, leave little room for

such an interpretation.

There are three elements of the offense created by

§798.05: 1) there must be a habitual occupancy of and

living in a room in the nighttime, 2) the offenders must be

a Negro man and white woman or white man and Negro

woman, and 3) they must be persons who are not married

to each other. Parramore v. State, 81 Fla. 621, 88 So. 472

(1921); Wildman v. State, 157 Fla. 334, 25 So. 2d 808

(1946); and see charge to jury at R. 93. Sexual relations

between the parties are not a necessary element of the

crime created by §798.05. Parramore v. State, supra.

On the other hand, it is well established that to convict

for lewd and lascivious association and cohabitation

2 “F.S.A. §798.02. Lewd and lascivious behavior.

If any man and woman, not being married to eaeh other,

lewdly and lasciviously associate and cohabit together, or if

any man or woman, married or unmarried, is guilty of open

and gross lewdness and lascivious behavior, they shall be pun

ished by imprisonment in the state prison not exceeding two

years, or in the county jail not exceeding one year, or by fine

not exceeding three hundred dollars.”

(§798.02), the state must prove “ both a lewd and lascivious

intercourse and a living together as in the conjugal rela

tion between husband and wife.” Wildman v. State, supra,

25 So. 2d at 808; Pinson v. State, 28 Fla. 735, 9 So. 706

(1891); Whitehead v. State, 48 Fla. 64, 37 So. 302 (1904);

Luster v. State, 23 Fla. 339, 2 So. 690 (1887); Cloud v.

State, 64 Fla. 237, 60 So. 180 (1912); Langford v. State,

124 Fla. 428, 168 So. 528 (1936). Sexual intercourse is

very definitely an element of this crime, and single or

occasional acts of incontinence will not sustain a con

viction under §798.02. Wildman v. State, supra; Penton

v. State, 42 Fla. 560, 28 So. 774 (1900); Thomas v. State,

39 Fla. 437, 22 So. 725 (1897).

Clearly, §798.05 (living in the same room) and §798.02

(lewdness) are distinct both on their face and as inter

preted. Florida, in fact, has simultaneously prosecuted

persons under both statutes, and in reversing both convic

tions the Florida Supreme Court gave no indication that

it regarded the laws as identical.3 Wildman v. State, 157

Fla. 334, 25 So. 2d 808 (1946). It is notable that in reversing

the convictions under both statutes in Wildman, supra,

the case was remanded for new trial without the slightest

intimation that the state could not again proceed on both

charges. Wildman is apparently still good law; it was fol

lowed in Callen v. Florida, 94 So. 2d 603 (1957).

Florida, thus, has created a specific crime, relating ex

clusively to interracial couples. Mere proof that an un

married man and woman of the same race habitually occu

3 It would have been unusual for the Florida Supreme Court,

unless clearly compelled, to attribute to its legislature the mean

ingless gesture of duplication. It has not done so. Surely the

legislature had some difference in mind when it set different pun

ishments in §798.02, and §798.05. Compare §798.03 (fornication

generally: 3 months imprisonment and $30 fine) with §798.04

(white person and Negro living “ in adultery or fornication” : 12

months imprisonment and $1,000 fine).

pied a room in the nighttime would not establish a crime

under Florida law.4

By labeling “ criminal” conduct that might be otherwise

innocent, merely because the parties are of different races,

Florida has violated its duty to afford to all persons the

equal protection of the laws. “Distinctions between citi

zens solely because of their ancestry are by their very

nature odious to a free people whose institutions are

founded upon the doctrine of equality.” Hirabayashi v.

United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100. And see, Korematsu v.

United States, 323 U. S. 214, 216; Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 347 U. S. 483; Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U. S. 650;

Anderson v. Martin, 379 U. S. 399.

Florida, however, has not advanced (and cannot advance)

any constitutionally acceptable basis for making the con

duct described by §798.05 a crime only when persons of dif

ferent races are involved. Surely, there is no justification

for eliminating solely on a racial basis the requirements

of proof that the state must meet in other crimes against

public morality. The racial classification is unreasonable,

is not clearly related to any legitimate governmental ob

jective, and violates the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. Cf. Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 U. S. 60; Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497.

4 Cf. Grice v. State, 76 Fla. 751, 78 So. 984 (1914), where de

fendants were acquitted of adultery (F. S. A. §798.02) since there

was no showing of sexual relations though there was evidence they

frequently slept in the same room along with others. Such conduct

would seem covered by a charge under F. S. A. §798.05 if persons

of different races engaged in it. The Court said that the “mere

living together of two persons of opposite sexes, either of whom

is married to a third person, does not constitute the offense of

living in an open state of adultery, but there must be acts of sexual

intercourse between them to constitute adultery. . . . ” The adul

tery law (§798.01) is the analogue of the lewdness law (§798.02)

for persons married to others.

As early as 1896, this Court said that criminal justice

must be administered “ without reference to consideration

based on race,” Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565, 591.

From Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, to Peterson v.

Greenville, 373 U. S. 244, the Court has repeatedly struck

down laws attempting to require separation of the races

by imposing criminal penalties. See e.g. Dorsey v. State

Athletic Commission, 359 U. S. 533, affirming 168 F. Supp.

149 (E. D. La. 1958) (interracial boxing a crime; held,

unconstitutional); Holmes v. Atlanta, 350 U. S. 879, re

versing 223 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir. 1955) (desegregated golf

matches criminal; held unconstitutional); Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S.

903, affirming 142 F. Supp. 707 (M, D. Ala. 1956); John

son v. Virginia, 373 XJ. S. 61; Lombard v. Louisiana, 373

U. S. 267; Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284.

In short, “ race is constitutionally an irrelevance” (Ed

wards v. California, 314 U. S. 160, 185), and “ . . . dis

criminations based on race alone are obviously irrelevant

and invidious.” Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U. S.

192, 203; cf. Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 XJ. S.

203 (Justice Stewart dissenting); Goss v. Board of Educa

tion, 373 U. S. 683, 687-688. In the words of the first Jus

tice Harlan, the Constitution is “ color blind,” Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 XJ. S. 537, 558 (dissenting opinion). The

decision below is in the teeth of this Court’s repeated hold

ings that racial segregation laws are invalid.

This case is somewhat different from Pace v. Alabama,

106 XJ. S. 583, where the conduct alleged was criminal irre

spective of the race of the parties, although greater penal

ties were proscribed when the offenders were not of the

same race. Here no penalties are provided for men and

women of the same race who commit the acts mentioned in

F. S. A. §798.05. (Substantially lower penalties are inflicted

under the fornication law—F. S. A. §798.03.) But appel

lants have no hesitancy in urging that Pace should be over

ruled if its reasoning is thought to extend to this case, and

to support the distinction made here. The Pace decision

rested on the notion that the state can treat an act differ

ently when committed by persons of different races, and

punish it as a “ different” crime. The silent premise is that

the states can segregate the races. Pace stands as an iso

lated vestige of the “ separate but equal” era inconsistent

with the entire development of the law of equal protection

since Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, or per

haps even since Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60. This

Court has cited Pace only two times in the eighty-two

years since it was decided and race discrimination was not

an issue in either of those cases.5 6 It ought to be overruled.

Probably no segregation law would ever have been invali

dated if this Court followed the reasoning of Pace that

equality is assured merely because Negro and white co

defendants are liable to the same punishment. Indeed, most

segregation laws struck down in recent years have been

indiscriminately applicable to both Negro and white vio

lators of the segregation commands,6 but have neverthe

less been invalidated on the ground that states serve no

legitimate governmental functions by segregating the races.

Cf. Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U. S. 244; and see Goss v.

Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683, 687-688; Shelley v.

Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1, 22.

5 See, e.g., Moore v. Missouri, 159 U. S. 673, 678 (1895) ; Hill v.

United States ex rel. Weiner, 300 U. S. 105, 109 (1937).

6 See, for example, the segregation laws invalidated in Brown v.

Board of Education (Briggs v. Elliott), 347 U. S. 483 (S. C. Code

1952, §5377), and Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903, affirming 142

F. Supp. 707, 710 (M. D. Ala. 1956) (Ala. Code 1940, §301 (31c)).

15

II.

Appellants Were Denied Rights Under the Due Proc

ess and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment by Florida’ s Miscegenation Laws Which

Had the Effect of Requiring the Jury to Disregard Evi

dence of a Common Law Marriage If It Decided That

One Appellant Was White and That the Other Was

Negro.

The trial court’s instructions to the jury based on Flor

ida’s miscegenation laws deprived appellants of the possi

bility of acquittal on the ground of common law marriage

because of race. As the language of the statute makes

clear, marriage of the parties absolutely vitiates any prose

cution based upon F. S. A. §798.05. The trial court, how

ever, instructed the jury so as to effectively prohibit it

from finding that appellants were married if it found that

one was white and the other was Negro.7 This instruction

was required by Florida Constitution, Art. 16, §24,8 and by

F. S. A. §§741.II9 and 741.12,10 which prohibit and penalize

marriages between white and Negro persons.11

7 In charging the jury the judge said (R. 94) :

“ I further instruct you that in the State of Florida it is

unlawful for any white female person residing or being in

this state to intermarry with any Negro male person and every

marriage performed or solemnized in contravention of the

above provision shall be utterly null and void.”

8 “24. Intermarriage of white persons and negroes prohibited

Sec. 24. All marriages between a white person and a negro,

or between a white person and a person of negro descent to

the fourth generation, inclusive, are hereby forever prohibited.”

9 “ 741.11 Marriages between white and negro persons prohibited

It is unlawful for any white male person residing or being

in this state to intermarry with any negro female person; and

it is in like manner unlawful for any white female person

residing or being in this state to intermarry with any negro

male person; and every marriage formed or solemnized in

Before dealing with the constitutionality of the misce

genation laws, we shall treat the state’s argument that the

jury instruction was harmless even if erroneous and that

the validity of the miscegenation laws may not be decided

in this case. The error was harmful, and several factors

lead to the conclusion that the binding jury instruction may

have deprived appellants of an opportunity for acquittal.

First, Florida gives full recognition to common law mar

riage and accords it the same legal incidents as a formal

marriage. Chaachou v. Chaachou, 73 So. 2d 830 (Fla.

1954); Navarro Inc. v. Baker, 54 So. 2d 59 (Fla. 1951).

Indeed, in this case the trial judge instructed the jury as

to Florida law on common law marriage (R. 94). This

implies that he deemed the marriage issue sufficiently in

volved to require the jury to decide it, if it found that ap

pellants were of the same race.

Secondly, the evidence taken in its most favorable light

tends to establish that appellants had contracted a common 10 11

contravention of the provisions of this section shall be utterly

null and void, and the issue, if any, of such surreptitious

marriage shall be regarded as bastard and incapable of having

or receiving any estate, real, personal or mixed, by inherit

ance.”

10 “ 741.12 Penalty for intermarriage of white and negro persons

If any white man shall intermarry with a negro, or if any

white woman shall intermarry with a negro, either or both

parties to such marriage shall be punished by imprisonment in

the state prison not exceeding ten years, or by fine not ex

ceeding one thousand dollars.”

11 In addition, Florida prohibits county judges from issuing mar

riage licenses to Negro and white couples (F. S. A. §741.13), and

ministers and other persons from performing a ceremony of mar

riage for an interracial couple (F. S. A. §741.15). The penalties

for violations are respectively 2 years imprisonment and $1,000

fine (F. S. A. §741.14) and one year and $1,000 (F. S. A. §741.16).

17

law marriage. There was enough evidence elicited from

the State’s witnesses to create an inference of common-law

marriage so as to constitute a jury question.

Although there was testimony that McLaughlin had in

January 1961 made a statement that he was “ separated”

from Willie May McLaughlin (whose last address he did

not know) (R. 74), there was no explanatory or corroborat

ing evidence before the jury indicating a prior legal mar

riage, or that a prior wife was still alive, or that there

had been no divorce during the intervening year before this

charge was brought. Appellant Hoffman held herself out

in conversations with her landlady and in “ signing in” at

the apartment as being married to McLaughlin (R. 23).

She did the same thing in conversation with a welfare

worker who testified that appellant said that “ she began

living with Mr. McLaughlin as her common-law husband”

(R. 84). Whatever the effect of the other statements men

tioned by the welfare worker—who seemingly did not dis

tinguish between a “ ceremonial” marriage and a “ legal”

one—any conflicts or inconsistencies should have been re

solved by the jury. All of these matters might have been

weighed by the jury in appraising the evidence if the

instruction had been different.

Statements by the parties to each other of present and

binding intention to be married effect a common law mar

riage in Florida. LeBlanc v. Yaivn, 99 Fla. 467, 126 So.

789 (1930); In re Thompson’s Estate, 145 Fla. 42, 199 So.

352 (Fla. 1940). The testimony of the parties that they

uttered to each other words of present intention provides

the best evidence of common law marriage. But, where the

best evidence cannot be obtained, reputation and cohabita

tion will raise and support a presumption of common law

marriage, LeBlanc v. Yawn, supra. Appellants did not tes

tify and could not be required to, as they enjoyed constitu

tional privileges against self incrimination in this criminal

18

proceeding. F. S. A. Const., Declaration of Eights, §12; see

also Malloy v. Hogan, ------ U. S. ------ , 12 L. ed. 2d 653.

Since their own testimony—the best evidence—was there

fore not available, testimony as to reputation and cohabita

tion could have sufficed to satisfy a jury.

Thirdly, the burden was on the State to demonstrate

beyond a reasonable doubt that appellants were not mar

ried. Although the attorney general has argued that Florida

cannot be forced to prove a negative and that marriage

constitutes an affirmative defense to be proved by the

defendants, Florida law seems to be otherwise. In his

charge the trial judge listed non-marriage as one of the

elements to be proved (R. 93). In Orr v. State, 129 Fla.

398, 176 So. 510, 511 (1937), where defendants were prose

cuted under a law punishing “ [wjhoever, not standing in

the relation of husband or wife . . . maintains or assists the

principal or accessory before the fact or gives the offender

any other aid, knowing that he has committed a felony

. . . ” , the court held that the burden of proving the non

existence of common law marriage rested upon the state.

Well-settled rules of Florida practice, moreover, require

the state to prove each and every element of the offense

and the allegations in the information. See, Campbell v.

State, 92 Fla. 775, 109 So. 809 (Fla. 1926); Lewis v. State,

53 So. 2d 707 (Fla. 1951). The information filed against

appellants charged them with “not being married” (R. 3).

Thus the constitutionality of the miscegenation law is

involved. This Court has never ruled on the issue. Pace

v. Alabama, supra, did not involve a marriage. Although

the statute in Pace forbade intermarriage (as well as

adultery and fornication) no charge of intermarriage was

made. No decision on the merits of this issue was rendered

in either Naim v. Naim, 350 U. S. 891, app. dismissed 350

U. S. 985, or Jackson v. Alabama, 348 U. S. 888 (denial of

certiorari).

19

The states have traditionally exercised a great degree of

control over the institution and incidents of marriage. Yet,

in this matter, as in others, the state’s power is not un

trammelled, but must yield to the constitutional strictures

of due process and equal protection. Cf. Meyer v. Ne

braska, 262 U. S. 390. The right to marry is a protected

liberty under the Fourteenth Amendment ; it is one of the

“ basic civil rights of man.” Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S.

535, 541. In Meyer v. Nebraska, supra, the Court declared

(262 U. S. 390, 399):

While this Court has not attempted to define with

exactness the liberty thus guaranteed [by the Four

teenth Amendment], the term has received much con

sideration, and some of the included things have been

definitely stated. Without doubt, it denotes not merely

freedom from bodily restraint, but also the right of

the individual to . . . marry, establish a home and bring

up children. . . .

The right to choose one’s own husband or wife is clearly

a right going to the very heart of personal liberty and

freedom. A government that interferes with personal

choice in marriage is regulating one of the most vital areas

of its citizens’ lives. The due process and equal protection

clauses surely prevent the states from engaging in irra

tional discriminations in this vital area of personal

liberty.12

Therefore, it is not enough for Florida to insist that it

can, without limit, abridge the liberty of persons to marry

under the guise of the police power. Who would doubt, for

12 Cf. Perez v. Lippold, 32 Cal. 2d 711, 198 P. 2d 17, 19 (1948) :

“Marriage is thus something more than a civil contract subject

to regulation by the state; it is a fundamental right of

free men. There can be no prohibition of marriage except for

an important social objective and by reasonable means.”

20

example, that Florida could not validly ban marriages be

tween Republicans and Democrats, or between redheads

and brunettes. The states cannot prohibit marriage on any

irrational basis they choose. In prohibiting marriage on

a racial basis, Florida has advanced no rational justifica

tion for the discrimination effected.

But while it has advanced no reasons, those which it

might be expected to bring forth in an effort to validate

its miscegenation laws are plainly suspect. On their face,

these racial laws run counter to the “ color-blindness” of

the Constitution. Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, 558

(dissenting opinion); cf. Koremutsu v. United States, 323

U. S. 214.

Some courts have upheld miscegenation statutes, predi

cating their reasonableness on beliefs in the value of

“ racial purity.” It has been said that a purpose is pre

venting the mixing of “ bloods.” State v. Pass, 59 Ariz.

16, 121 P. 2d 882 (1942). In Lonas v. State, 50 Tenn. 310,

311 (1871), the Court stated:

The laws of civilization demand that the races be kept

apart in this country. The progress of either does

not depend on an admixture of blood.

# * #

[Intermarriage would be] a calamity full of the sad

dest and gloomiest portent . . . .

A Georgia court announced that:

Such [moral and social] equality does not exist and

never can. The God of nature made it otherwise, and

no human law can produce it and no human tribunal

can enforce it. . . . From the tallest archangel in

Heaven, down to the meanest reptile on earth, moral

and social inequalities exist and must continue to exist

21

through all eternity. (Scott v. Georgia, 39 Ga. 321, 326,

(1869).)

Some courts have found a justification for these laws in

the state’s power to preserve and ensure the health of their

citizens, as Missouri’s court did in 188313 and as a Georgia

court did in 1869.14

Clearly all of these grounds for miscegenation15 laws

rest on theories long deemed nonsensical throughout the

world’s community of natural scientists. The idea of ‘‘pure

races” has long been abandoned by science. The distin

guished American geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky has

said:

The idea of a pure race is not even a legitimate ab

straction; it is a subterfuge used to cloak one’s igno

rance of the phenomenon of racial variation. (Dob

zhansky, “ The Race Concept in Biology,” The Scientific

Monthly, LII (Feb. 1941), pp. 161-165.)

13 “ It is stated as a well authenticated fact that if the issue of

a black man and a white woman and a white man and a black

woman intermarry, they cannot possibly have any progeny, and

such a fact sufficiently justifies those laws which forbid the inter

marriage of blacks and whites. . . . ” State v. Jackson, 80 Mo. 175,

179 (1883).

14 “ The amalgamation of the races is not only unnatural, but is

always productive of deplorable results. Our daily observations

show us, that the offspring of these unnatural connections are gen

erally sick and effeminate, and that they are inferior in physical

development and strength to the full-blood of either race. . . .

Such connections never elevate the inferior race to the position

of superior, but they bring down the superior to that of the inferior.

They are productive of evil, and evil only, without any correspond

ing good.” (Emphasis added.) Scott v. Georgia, 39 Ga. 321, 323

(1869).

15 Even the word “miscegenation,” to refer to intermarriage, was

reportedly invented as a hoax in an 1864 political pamphlet con

nected with a presidential campaign. See discussion in Montague,

Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race, 400 (4th ed.

1964).

22

And see the many scientific authorities rejecting the “ pure

race” idea collected in Weinberger, “ A Reappraisal of the

Constitutionality of Miscegenation Statutes,” 42 Cornell

L. Q. 208, 217, n. 68“

The 1952 UNESCO Statement On The Nature of Race,16 17

prepared by distinguished natural scientists from around

the world, concludes:

There is no evidence for the existence of so-called

“ pure” races. Skeletal remains provide the basis of

our limited knowledge about earlier races. In regard

to race mixture, the evidence points to the fact that

human hybridization has been going on for an indefi

nite but considerable time. Indeed, one of the processes

of race formation and race extinction or absorption is

by means of hybridization between races. As there is

no reliable evidence that disadvantageous effects are

produced thereby, no biological justification exists for

prohibiting intermarriage between persons of different

races.

Similarly, other pseudoscientific props for racism, includ

ing the notions of biological disadvantages of race mixture,

and the assumption that cultural levels depend on racial

factors, are completely undermined by modern scientific

knowledge.18 For example, the 1952 UNESCO Statement,

swpra, concludes by saying:

16 See also Note, 58 Yale L. J. 472 (1949).

17 The full title is : “ Statement on the Nature of Race and Race

Differences—by Physical Anthropologists and Genticists, Septem

ber 1952,” published by UNESCO. The statement, published in

numerous publications by UNESCO (as well as a similar 1950

UNESCO statement of social scientists) is conveniently available

in Appendix A of Montague, op. cit., 361 et seq.

18 The importance of environmental factors in determining cul

tural levels was noted by the court in Perez v. Lippold, 32 Cal. 2d

711, 198 P. 2d 17, 24-25 (1948). Major contemporary research

9. We have thought it worth while to set out in a

formal manner what is at present scientifically estab

lished concerning individual and group differences.

(1) In matters of race, the only characteristics which

anthropologists have so far been able to use effectively

as a basis for classification are physical (anatomical

and physiological).

(2) Available scientific knowledge provides no basis

for believing that the groups of mankind differ in their

innate capacity for intellectual and emotional develop

ment.

(3) Some biological differences between human

beings within a single race may be as great or greater

than the same biological differences between races.

(4) Vast social changes have occurred that have not

been connected in any way with changes in racial type.

Historical and sociological studies thus support the

view that genetic differences are of little significance

in determining the social and cultural differences be

tween different groups of men.

(5) There is no evidence that race mixture produces

disadvantageous results from a biological point of

view. The social results of race mixture whether for

good or ill, can generally be traced to social factors.

And see, generally, Montague, Man’s Most Dangerous

Myth: The Fallacy of Race (4th ed. 1964), for a noted

anthropologist’s full discussion of the most recent scien

tific evidence and research on race. •

demonstrating the absence of any relation between race and cul

tural achievement is found in Beals and Hoijer, An Introduction

to Anthropology 195-198 (1953) ; Hankins, The Facial Basis of

Civilization 367-371 (1926); Kroeber, Anthropology 190-192

(1948) ; Ashley Montague, An Introduction to Physical Anthro

pology 352-381 (1951) ; Yerkes, “ Psychological Examining in the

U g A rm y” 15 Mem. Nat. Acad. Sci. 705-742 (1921).

24

Actually, the miscegenation laws never really rested on

any firm scientific foundation nor were they intended to

serve a scientific purpose. Miscegenation laws grew out

of the system of slavery and were based on race prejudices

and notions of Negro inferiority used to justify slavery,

and later segregation.

Chief Justice Taney said in Scott v. Sanford, 19 How.

393, 409 (1857):

[The miscegenation laws] show that a perpetual and

impassable barrier was intended to be erected between

the white race and the one which they had reduced to

slavery, and governed as subjects with absolute and

despotic power, and which they then looked upon as so

far below them in the scale of created beings, that in

termarriages between white persons and negroes or

mulattoes were regarded as unnatural and immoral,

and punished as crimes, not only in the parties, but in

the persons who joined them in marirage. . . . This

stigma, of the deepest degradation, was fixed upon the

whole race (emphasis added).

As an earlier Alabama court, which found a miscegena

tion statute unconstitutional, announced in Burns v. State,

48 Ala. 195, 197 (1872) :19

It cannot be supposed that this discrimination was

otherwise than against the negro, on account of his

servile condition, because no state would be so unwise

as to impose disabilities in so important a matter as

marriage on its most favored citizens, without con

sideration of their advantage.

The fact that the miscegenation doctrine relates to the

caste system, rather than to any design to protect race

19 Burns was overruled in Green v. State, 58 Ala. 190 (1877).

25

“purity” , is confirmed by the harsh treatment of the chil

dren of such marriages.20

These are laws with a “ purely racial character and pur

pose,” like the regulations in Goss v. Board of Education,

373 U. S. 683, 688. Miscegenation laws are “ relics of slav

ery” 21 and their enforcement by the states violates the

Fourteenth Amendment.22 This Court has struck down

numerous segregation laws rejecting all manner of state

claims of Negro inferiority, and claims of the legitimacy

of governmentally required and encouraged racism. Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; Cooper v. Aaron, 358

20 For example, F. S. A. §741.11 declares that the issue of inter

racial marriages “shall be regarded as bastards.” It, in addition,

renders them “ incapable of having or receiving any estate, real,

personal or mixed by inheritance.” Florida, where the parents are

of one race, has modified the rigors of the common law dealing

with bastardy. F. S. A. §731.29. This latter class of illegitimate

children can inherit property from the mother. Through acknowl

edgment by the father they are enabled to inherit through him.

Wall v. Altbello, 49 So. 2d 532 (1950). Yet, issue of interracial

marriages cannot be legitimized and can never inherit property.

Children can ordinarily be legitimized by the subsequent marriage

of the parents. Where, however, the parents are of different races,

F. S. A. §741.11 prevents them from legitimizing their children

in this manner. See also, Note, “Rights of Illegitimates Under

Federal Statutes,” 76 Harv. L. Rev. 337 (1962), for the possible

impact of Florida miscegenation laws on federally created rights.

21 Of. Bell v. Maryland,------ U. S. — —, 12 L. ed. 2d 822, 871,

877 (separate opinion of Justice Douglas). F. S. A. §741.11 is

derived from Fla. Act. Jan. 23, 1832, §§1, 2. Miscegenation laws

now remain in effect in only nineteen states; see appendix, infra.

22 Florida’s belated argument that the Fourteenth Amendment

is not binding on it because improperly proposed in the Senate is

frivolous. But responsive to Florida’s argument concerning the

vote needed to propose a constitutional amendment, see National

Prohibition Cases, 253 U. S. 350, 386 (two-thirds of those present) ;

cf. Missouri Pacific Bailway Co. v. Kansas, 248 U. S. 276. On June

8, 1866, the Senate had a quorum; 44 members were present; 33

of those present (far more than two-thirds) voted in favor of the

proposed amendment. 46th Cong. Globe, part 4, p. 3042 (39th

Cong., 1st Sess.).

2 6

U. S. 1; Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683; John

son v. Virginia, 373 U. S. 61; Peterson v. Greenville, 373

U. S. 244; Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U. S. 267; Wright

v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284; Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S.

526; Anderson v. Martin, 379 U. S. 399; Shelley v. Kraemer,

339 U. S. 1; Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60; Gayle v.

Browder, 352 U. S. 903.23 The logic of those eases compels

the same result here.

The issue is whether under our Constitution Negroes

will have the same personal liberties and the same status

as citizens given to white Americans. There can be but

one answer if the purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment

are to be realized in our law.

23 Cf. Perez v. Lippold, 32 Cal. 2d 711, 198 P. 2d 17 (1948)

(invalidating California’s miscegenation law; and see Burns v.

State, 48 Ala. 195 (1872), holding an Alabama miscegenation law

violative of the Fourteenth Amendment and a federal statute

(now 42 U. S. C. §1981) as well. (As noted above Burns was

overruled by a later Alabama Court.)

27

III.

Appellants Were Denied Due Process Because Either

There Was No Proof of Their Race or Florida’ s Racial

Definition Is Vague.

In order to convict under F. S. A. §798.05, Florida was

required to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that appellant

McLaughlin was a Negro and that appellant Hoffman was

white. Florida law has attempted to define “ Negro,” but

there is no attempt at all to define a white person. The

definition of “ Negro” in F.S.A. §1.01(6) is:

. . . (6) The words “negro,” “ colored,” “ colored per

sons,” “mulatto” or “persons of color,” when applied

to persons, include every person having one-eighth or

more of African or negro blood.

At the trial in this case the prosecution made no pretense

of proving race (an element of the crime) by reference to

the statutory rule—“ one-eighth or more of African or negro

blood.” Instead, the prosecutor relied on a policeman’s

opinion as to the race of both appellants (R. 65), and Ms

opinion was admittedly based merely upon observation of

them.

The State surely failed to satisfy the literal requirements

of F. S. A. §1.01(6) as to either appellant. This is quite

evident from a colloquy between the Court and counsel.

Defense counsel objected to opinion evidence on appellants’

race saying that the State was bound by the statutory defi

nition which mentioned “blood” ; that there was no such

thing as “Negro blood” ; and that the statute was thus

vague (R. 61). The trial judge, after expressing doubt as

to his power to declare a state law unconstitutionally

vague, said that this one had to be given a “ common sense”

construction and that it must refer to “ anyone whose blood

is y8th from a Negro ancestor” (R. 62). When counsel

pointed out that there was no proof concerning appellant’s

ancestors, the Court said, “ Then we come back to the ap

pearance again” (R. 63), and ruled that “ anybody who had

considerable experience in dealing and associating with

Negro people and white people will be able to testify to

some extent at least as to the race of particular persons”

{Id.), and that any doubts were going to be “ up to the

jury” (Id.). The policeman was then allowed to express

his opinion that McLaughlin was a Negro and Hoffman

was white.

It may be noted that the instruction to the jury con

sisted of a reading of F. S. A. §1.01(6) and a statement

that an element of the crime was:

. . . That one defendant in this case has at least one-

eighth Negro blood, and that the other defendant has

more than seven-eighths white blood (R. 93).

If the statutory definition and the instruction to the jury

are taken literally so as to require proof about “ blood”

(or even if “blood” is taken to mean “ ancestors” ), there

was a complete absence of proof of an essential element

of the crime and the conviction denied due process under

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U. S. 199. There was no at

tempt to prove that appellant Hoffman had more than

seven-eighths “white blood” or that appellant McLaughlin

had more than one-eighth “Negro blood.” Such an effort

would have been doomed to failure. In the first place, the

notion of “ Negro blood” and “white blood” rests on the

misconception, entirely contrary to the known facts but

nevertheless common, that there is some identifiable differ

ence between “ Negro blood” and “white blood.” 24 Secondly,

24 See Montague, op. cit. supra at 287, 288:

“ The blood of all human beings is in every respect the same,

with only two exceptions, that is, in the agglutinating prop-

29

there was still a failure of proof even using the idea that

the statute refers to ancestors. The definition in §1.01(6)

is circular insofar as it uses the notion of “ Negro blood”

to define the word “ Negro” and meaningless in its use of

“African blood” to define “Negro.” Obviously, there are

citizens of African nations belonging to every ethnic and

anthropological classification. But, in any event, there was

no evidence to connect McLaughlin with Africa. The rec

ord shows only that he was born in La Ceiba,23 Honduras

(R. 82). Finally, blood has nothing to do with hereditary

characteristics. Montague, op. cit., CL. 14.

The appearance test upon which Florida ultimately re

lies removes the last pretense of statutory clarity. It totally

fails to provide a sufficiently definite standard to meet the

requirements of due process. It is based on witnesses’ and

jurors’ opinions of a person’s race, depends on their shift

ing and subjective perceptions influenced by stereotypes

erties of the blood which yields the four blood groups and in

the Rh factor. But these agglutinating properties of the four

blood groups and the twenty-one serologically distinguishable

Rh groups are present in all varieties of men, and in various

groups of men they differ only in statistical distribution. This

distribution is a matter not of quality but of quantity. There

are no known or demonstrable differences in the character of

the blood of different peoples, except that some traits of the

blood are possessed in greater frequency by some than by

others.

* * * #

“ . . . In short, it cannot be too emphatically or too often

repeated that in every respect the blood of all human groups

is the same, varying only in the frequency with which certain

of its chemical components are encountered in different popu

lations. This similarity cuts across all lines of caste, class,

group, nation, and ethnic group. Obviously, then, since all

people are of one blood, such differences as may exist between

them can have absolutely no connection with blood.”

25 A Central American city, far from Africa; Rand-McNally

Cosmopolitan World Atlas, p. 56.

HO

and conditioned by their differing personal experiences.

In the “never-never land” of the appearance test, a per

son’s race is not an objective fact at all, but depends en

tirely on other persons’ views of him. Differences of opin

ion and perception as to the race of persons are a common

place of life which inevitably flow from the multitude of un

satisfactory definitions. This standard obviously leaves

the jurors to their own devices in determining race on any

basis they choose. To make such a subjective ad hoc evalu

ation the basis for criminal conviction violates elemental

standards of fairness. To make a man conduct himself on

the basis of a preliminary guess as to what his race will

be in the opinion of some future unknown witnesses and

jurors who will use no precise standards places liberty on

a slippery surface unworthy of a civilized system of crimi

nal law. Cf. Connolly v. General Construction Co., 269

U. S. 385. This test is easily as nebulous as the phrase

“ known to be a member of a gang” and the term “ gangster”

in the New Jersey law invalidated in Lanzetta v. New

Jersey, 306 IT. S. 451. The vagueness of legal definitions

of race is a substantial reason why the creation of crimes

depending on the race of parties violates the Fourteenth

Amendment.

31

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully submitted

that the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted.

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

L eroy D. Clark

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

Louis H. P ollak

127 Wall Street

New Haven, Connecticut

W illiam T. Coleman, Jr.

2635 Fidelity-Philadelphia

Trust Bldg.

Philadelphia 9, Pennsylvania

G. E. Graves, Jr.

802 N. W. Second Avenue

Miami, Florida

Attorneys for Appellants

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX

STATES REPEALING- MISCEGENATION LAWS

IN RECENT YEARS

1. Arizona (1962): Laws 1962, ch. 14, §1, deleting a

portion of Ariz. Rev. Stat. §25-

101 (1956).

2. California (1959): - Stat. 1959, eh. 146, §1, at 2043,

repealing Cal. Civ. Code §§60,

69 (1954).

3. Colorado (1957): Colorado Laws 57, §1, at 334,

repealing Colo. Rev. Stat. §§90-

1-2, 90-1-3 (1953).

4. Idaho (1959): Laws 1959, ch. 44, §1, at 89, de

leting Idaho Code Ann. §32-206

(1947).

5. Montana (1953): Laws 1953, eh. 4, see. 1, repeal

ing Laws 1909, ch. 49, secs. 1-5.

6. Nebraska (1963): Neb. Sess. Laws, at 736 (1963),

repealing Rev. Stat. of Neb.

§§42-103, 42-328 (1948).

7. Nevada (1959): Nev. Stat. 1959, at 216, 217, re

pealing Nev. Rev. Stat. tit. 11,

eh. 122, 180 (1957).

8. North Dakota (1955): N.D. Stat. 1955, ch. 246, §1, re

pealing N.D. Code §14-03-04.

9. Oregon (1951): O. R. S. §106.210 (1963), repeal

ing Ore. Code Law Ann. §§23-

1010, 63-102.

10. South Dakota (1957): S.D. Sess. Laws 1957, ch. 38,

repealing S.D. Code §14.990

(1939).

Sess. Laws 1963, eh. 43, repeal

ing Utah Stat. §30-1-2 (1953).

11. Utah (1963):

2a

STATES REPEALING MISCEGENATION LAWS

IN LAST CENTURY

1. Iowa: Omitted—1851.

2. Kansas: Omitted—1857. Laws c. 49 (1857).

3. Maine: Repealed 1883. Laws p. 16 (1883).

4. Massachusetts: Repealed 1840. Acts, c. 5 (1843).

5. Michigan: Prior interracial marriages legalized

in 1883. Act 23, p. 16 (1883).

6. New Mexico: Repealed 1886. Laws p. 90 (1886).

7. Ohio: Repealed 1887. Laws p. 34 (1887).

8. Rhode Island: Repealed 1881. Acts, Jan. Sess. p. 108

(1881).

9. Washington: Repealed 1867. Laws pp. 47-48 (1867).

STATES NEYER ENACTING STATUTES WHICH

PROHIBIT INTERRACIAL MARRIAGE

1. Alaska 2. Connecticut 3. Hawaii

4. Illinois 5. Minnesota 6. New Hampshire

7. New Jersey 8. New York 9. Pennsylvania

10. Vermont 11. Wisconsin

3a

STATES AT PRESENT PROHIBITING

INTERRACIAL MARRIAGES

(PENALTIES FOR INFRACTIONS

ARE INDICATED)

1. Alabama: Ala. Const. §102; Ala. Code, Tit. 14, §360

(1958); 2-7 imprisonment (idem.).

2. Arkansas: Ark. Stat. §55-104 (1947); 1 year imprison

ment and/or $250 fine (Ark. Stat. §41-106).

3. Delaware: Del. Code Ann., Tit. 13, §101 (1953); $100

fine in default of which imprisonment for not more

than 30 days (Del. Code Ann., Tit. 13, §102).

4. Florida: Fla. Const, art. XVI, §24; Florida Stat.

§741.11 (1961); maximum 10 years imprisonment

and/or maximum fine of $1,000 (Fla. Stat. §741.12).

5. Georgia: Ga. Code Ann., §53-106 (1933); 1 to 2 years

imprisonment (Ga. Code Ann. 53-9903).

6. Indiana: Ind. Ann. Stat. §44-104 (Burns, 1952); im

prisonment of 1 to 10 years and fine of $100-1000

Ind. Ann. Stat, (Burns. 1952) §10-4222.

7. Kentucky: Ky. Rev. Stat. §402.020 (1943); fine of $500

to $1000 and if violation continued after conviction,

imprisonment of 3 to 12 months (K.R.S. §402.990).

8. Louisiana: La. Civil Code Art. 94 (Dart. 1945); 5 years

imprisonment (La, Rev. Stat. Ch. 14, §79).

9. Maryland: Md. Ann. Code Art. 27, §398 (1957); im

prisonment from 18 months to ten years (idem.).

10. Mississippi: Miss. Const, art. 14, §263; Miss. Code Ann.

§459 (1942); Imprisonment up to 10 years (Miss.

Code Ann. §2000, 1960).

11. Missouri: Mo. Rev. Stat, §451.020 (1959); 2 years in

state penitentiary; and/or a fine of not less than $100,

and/or imprisonment in county jail for not less than

3 months (Mo. Rev. Stat. §563.240).

4a

12. North Carolina: N. C. Const, art. XIV, §8; N. C. Gen.

Stat. §51-3 (1953); 4 months to 10 years imprison

ment (N. C. Gen. Stat. §14-181).

13. Oklahoma: Okla. Stat., Tit. 43, §12 (1961); 1 to five

years and up to $500 fine (Okla. Stat., Tit. 43, §13).

14. South Carolina: S. C. Const, art. 3, §34; S. C. Code

§20-7 (1952); imprisonment for not less than 12

months, and/or fine of not less than $500 (idem.).

15. Tennessee-. Tenn. Const, art. (11), §14; Tenn. Code

Ann. §36-402 (1956); 1 to 5 years imprisonment, or,

on recommendation of jury, fine and imprisonment

in county jail (Tenn. Code Ann. §36-403).

16. Texas: Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. art. 4607 (1948); 2 to 5

years imprisonment (Tex. Penal Code art. 492).

17. Virginia: Va. Code Ann. §20-54 (1953); 1 to 5 years

(Va. Code Ann. §20-59).

18. West Virginia: W. Ya. Code Ann. §4697.

19. Wyoming: Wyo. Stat. §20-18 (1957); $1000 fine and/or

imprisonment up to 5 years (Wyo. Stat. §20-19).

38