Rivers v Roadway Express Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

August 10, 1993

115 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rivers v Roadway Express Reply Brief, 1993. b822b286-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ddf5a914-dec7-4190-a2d7-6c74c4ad7570/rivers-v-roadway-express-reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

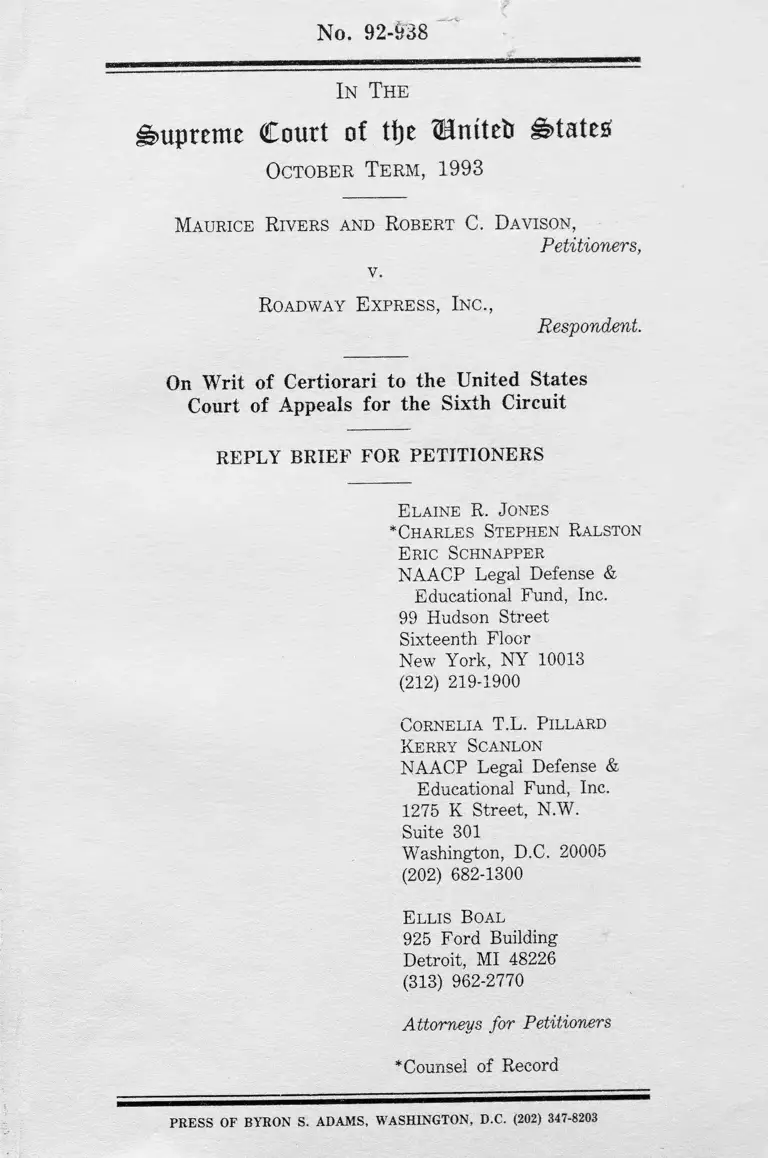

No. 92-938

In T h e

Supreme Court of tfje 'SHniteb

Octo b er T e r m , 1993

Maurice Rivers and Robert C. Davison,

Petitioners,

v.

Roadway E xpress, Inc.,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

Elaine R. Jones

‘Charles Stephen Ralston

Eric Schnapper

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Cornelia T.L. Pillard

Kerry Scanlon

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington. D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Ellis Boal

925 Ford Building

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 962-2770

Attorneys for Petitioners

‘Counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ARGUMENT ............................................. ......................... 1

I. THE 1991 CIVIL RIGHTS ACT ITSELF MAKES

CLEAR THAT § 101 APPLIES HERE ................. 1

A. The Statute’s Text and Structure Support

Application of § 1 0 1 ...................................... 1

B. The Identity Between § 1981 Prior to

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union and As

Amended By § 101, and the Virtually

Unanimous Acknowledgment in Congress

of that Identity, Confirm that § 101 is

Restorative .......................... 5

II. TH IS C O U R T SH O U LD R E A F F IR M

BRADLEY V RICHMOND SCHOOL BOARD,

AND APPLY § 101 HERE ................ 6

A. The Default Rule Respondents Advocate

Would Require the Courts to Make

Difficult and Unguided Distinctions

Between New Statutes that Apply to

Pending Cases and New Statutes that Do

Not ......................................................................... 7

B. Bradley Was Consistent With Prior Law . . . . 11

1. Supreme Court C ase s ...................................... 12

2. Court of Appeals Decisions .......................... 12

3. Treatises ............................................................ 12

4. State Constitutions and Laws . . . . . . . . . . 14

5. English Cases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

6. Prior Views of Respondent’s Counsel . . . . 15

C. Section 101’s Remedial and Procedural

Nature is Unaffected By Whether § 1981

is "A Distinct Positive Law" From Title

VII . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

III. T H I S C O U R T S H O U L D N O T

RETROACTIVELY CHANGE RULES ABOUT

STATUTORY APPLICABILITY UPON WHICH

CONGRESS HAS RELIED . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

CONCLUSION ----------------. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

11

APPENDICES B-O

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver,

415 U.S. 36 (1974).............. ............. ....................... 17

Bowen v. Georgetown University Hosp.,

488 U.S. 204 (1988) . . . . . . . . ----- . . . . . . . . . . 10

V Bowles v. Strickland,

151 F.2d 419 (5th Cir. 1945) ................... .. 11, 12

i Dargel v. Henderson,

200 F.2d 564 (Em. Ct. App. 1952) ........................ 12

Bradley v. Richmond School Board,

416 U.S. 696 (1 9 7 4 )............ passim

, Chevron US, Inc. v. National Resources Defense Council,

■ Inc.,

467 U.S. 837 (1 9 8 4 )........ 4

■ Cox v. Thomason,

2 C. & J. 498 (Ct. Exch. 1 8 3 2 )............ .. 15

Dash v. Van Kleeck,

5 Am. Dec. 291 (1811).......................... 14

Freeman v. Moyers,

1 A. & E. 338 (K. B. 1834) ................................. .. 15

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc.,

421 U.S. 454 (1 9 7 5 )................... 17

IV

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp. v. Bonjomo,

494 U.S. 827 (1990) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . passim

V Kimbray v. Draper,

3 Q.B. (L.R.) 160 (Q.B, 1868) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

— Larkin v. Saffarans,

15 F. 147 (C.C. W.D. Tenn. 1883) . . . . . . . . 11, 12

Leatherman v. Tarrant County,

113 S. Ct. 1160 (1993) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Lytle v, Household Manufacturing, Inc.,

494 U.S. 545 (1990) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Minority Police Officers v. City o f South Bend,

617 F. Supp. 1330 (N.D.Ind. 1985) . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union,

491 U.S. 164 (1989) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5, 17

< Pennsylvania v. Union Gas Co.,

491 U.S. 1 (1989)................... ........... ........... .. . 3, 16

A,Society v. Wheeler,

2 Gall. 139 (1814) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Sturges v. Carter,

114 U.S. 511 (1885) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Thorpe v. Housing Authority o f Durham,

393 U.S. 268 (1969) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

'dTowler v. Chatterton,

6 Bing. 258 (Ct. Com. Pleas. 1829) . . . . . . . . . . . 15

V

United States v. Burke,

112 S. Ct. 1867 (1992) . . . ___ . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

v United States v. McMann,

434 U.S. 192 (1977)....... .............................................4

Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio,

490 U.S. 642 (1 9 8 9 )........................ 3

Weaver v. Graham,

450 U.S. 24 (1981)............ ........... ....................... 1, 2

Williams v. Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway,

627 F. Supp. 752 (W.D.Mo. 1986) .......... ................6

•< Wright v. Hale,

6 Hurl. & Norm. 226 (Ct. Exchequer 1860) . . . . 14

STATUTES

i y Rules Enabling Act, 28 U.S.C. § 2027(a)........................ . 10

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ................... .............................. .. passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-e£ s e q ............................................. .. passim

MISCELLANEOUS

1 Kent, Commentaries on American Law ................... .. . 13

Smead, The Rule Against Retroactive

Legislation: A Basic Principle of

Jurisprudence, 20 Minn. L. Rev. (1936) . . . . . . . 14

ARGUMENT

I. THE 1991 CIVIL RIGHTS ACT ITSELF MAKES

CLEAR THAT § 101 APPLIES HERE

A. The Statute’s Text and Structure

Support Application of § 101

The central statutory construction question relating to

the applicability of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 is what

meaning to give to § 402(a). Respondents urge the Court to

abandon any effort to divine meaning from the language of

the statute. They argue that each of the key statutory

provisions which bear on the statute’s applicability —

§ 402(a), § 402(b) and § 109(c) — is devoid of meaning.

Evaluated under normal principles of construction, however,

these provisions are certainly as clear as the provisions this

court has readily construed in Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical

Corp. v. Bonjomo, 494 U.S. 827 (1990), and other cases.

Roadway’s only argument that the Act makes § 101

inapplicable is that the phrase "take effect upon enactment"

was routinely interpreted to apply only to conduct and trials

occurring after enactment. Roadway Br. at 15. The six court

of appeals decisions upon which Roadway relies in support of

this assertion simply do not hold that such language means

that a statute is not to be applied to pending cases. On the

contrary, four of Roadway’s cited cases expressly assert that

such language did not resolve the question of applicability of

the statutes at issue. The other two of Roadway’s cases rely

on different statutory language not present in the 1991 Act in

addition to the general effective date provision. See

Appendix B. Based on these cases, a Congress presumed to

know the existing law would have no basis whatsoever to

assume that "take effect upon enactment" means that the

statute shall not apply to pre-Act conduct.

In Weaver v. Graham, 450 U.S. 24 (1981), another case

upon which Roadway relies, this Court held that language

requiring application of new statutory provisions "on the

2

effective date of the act" must be read to mean that new

provisions did apply to pre-Act conduct. In Weaver, this

Court considered whether a Florida statute diminishing gain

time earned by convicted prisoners by its express terms

applied to gain time earned pre-enactment. The Court

determined that the statute on its face "[c]learly" would apply

"to prisoners convicted for acts committed before the

provision’s effective date." Id. at 31.1 Thus, under Weaver

the Court could, based on the language of § 402(a) alone,

construe § 101 to apply to pending cases addressing pre-Act

discrimination.

In addition to § 402(a), the sections excepting certain

pre-Act cases and conduct from the general rule —- §§ 402(b)

and 109(c) — support petitioner’s position that the Act

expressly applies. These exceptions must be read under

established canons to (i) have a meaning different from

(rather than redundant of) § 402(a) and2 (ii) describe the

only situations receiving the specific treatment they demand.3

The existence of specific exceptions suffices to make

clear the underlying rule even under the exacting standard

1 Once it determined that the statute would apply, the Court then

proceeded to determine that the gain-time amendment violated the ex post

facto clause, but in doing so the Court expressly distinguished its analysis

under the ex post facto clause from "the test for evaluating retrospective

laws in the civil context." Id. at 29, n. 13.

2 See Appendix C (listing Supreme Court cases retying on the anti

redundancy canon).

3 See Appendix D (listing Supreme Court cases relying on the

canon that the inclusion of one tiling implies the exclusion of others

("expressio unius est exclusio alterius"), including two during 1993).

3

applied in Eleventh Amendment cases.4 In Pennsylvania v.

Union Gas Co., 491 U.S. 1 (1989), the Court was faced with

precisely the same kind of indicia of intent that petitioners

point to here, and it held that those indicia sufficed to show

that CERCLA subjected the states to suit in federal court.

Under CERCLA, the general definition of "owners and

operators" was held to be ambiguous standing alone, id. at 8,

n. 2, but an exception that excluded states from liability under

certain circumstances made clear that states were otherwise

subject to suit. That exception acted as "an express

acknowledgement of Congress’ background understanding ...

that States would be liable in any circumstance ... from which

they were not expressly excluded." Id. at 8.

The substance of the Civil Rights Act supports

petitioners’ interpretation of § 402(a). Under Roadway’s

view, §§ 402(b) and 109(c) are redundant, and Roadway

implies that but for errors in final drafting these provisions

would have been eliminated. Roadway Br. at 23. On the

face of the statute, however, it makes sense that Congress

chose to bar application of the Act to pending cases only with

regard to §§ 109(c) and 402(b). While most of the 1991 Act

is procedural and remedial, § 109(c), in contrast, clearly made

illegal under Title VII conduct which had previously been

wholly legal. Section 402(b), which only makes the Act

inapplicable to Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio, 490 U.S.

642 (1989), was arguably a targeted effort to put to rest a

4 The proper standard of clarity according to which the 1991 Act

should be read is not a clear-statement rule, but the standard this Court

employed in Bonjonio. Under Bonjomo, whether the statute’s "plain

language" requires that it be applied to pending cases is determined by

"the most logical reading of the statute," 494 U.S. at 839, 838, which may

be "[ijmplicit," id., 839, and need not be "clear and unequivocal," as

Roadway asserts.

4

case in which, after sixteen years of litigation, plaintiffs had

not established any liability.5

Roadway and USI Film Products are, in effect,

arguing that they, too, should have been included in the

statute’s two express exceptions and obtained the same

treatment as defendants in cases by United States nationals

abroad under § 109(c) and the Wards Cove case under

§ 402(a). Roadway contends that the change made by § 101

is like the change made by § 109, even though for Roadway,

unlike for ARAMCO, the discrimination alleged was illegal

all along under Title VII, and § 101 has no subsection like

§ 109(c) limiting its applicability. USI Film Products

contends that providing for new remedies is unfair in a case

filed in 1989, but the change made by § 402(b) expressly drew

a different line, finding unfairness only in applying the Act to

old cases in which "a complaint was filed before March 1,

1975." It is thus respondents themselves, not petitioners, who

are "waging in a judicial forum a specific policy battle which

they ultimately lost." USI Film Products Br. at 16-17, quoting

Chevron US, Inc. v. National Resources Defense Council, Inc. ,

467 U.S. 837, 864 (1984).

Respondents seek to undercut the "most logical

reading" of the statute by reference to legislative history . But

where the language is reasonably clear, legislative history

must not be relied upon to create ambiguity. United States v.

McMann, 434 US 192, 199 (1977). After the language of the

Act was agreed upon, statements were made on the floor of

the Senate expressing conflicting views on its meaning. Prior

to enactment, however, the vast majority of voting members

expressed no position at all about the meaning of the

effective date provisions, and all that is known about most

5 The constitutionality of § 402(b) has been challenged in the Wards

Cove case.

5

members’ views is that they approved the statute’s text. This

is why the text should be given controlling effect.

B. The Identity Between § 1981 Prior to Patterson v.

McLean Credit Union and As Amended By § 101,

and the Virtually Unanimous Acknowledgment in

Congress of that Identity, Confirm that § 101 is

Restorative

Respondents concede that, if Congress intended § 101

to be restorative, such intent would be evidence in favor of

application of the section to existing cases: "To be sure, the

‘restorative’ purpose of a law ... may provide a suggestion of

Congress’ intent to act retroactively." Roadway Br. at 43.

That § 101 both was restorative and was intended to be is

made evident by a simple comparison of the state of law prior

to Patterson v. McLean Credit Union and after the Civil Rights

Act of 1991. It was well established prior to this Court’s

Patterson decision that § 1981 generally covered

discrimination in all aspects of employment. In addition to

this Court’s repeated assumption that § 1981 covered

discharge, and the Sixth Circuit’s numerous holdings to that

effect,6 the nearly 200 cases listed in Appendix E show that

prior to Patterson § 1981 was overwhelmingly construed to

cover discrimination in every aspect of employment now

included in § 101.7

6 See Petitioners’ Br. at 28, nn. 29, 28.

7 Defendants’ assertion that "the law under Section 1981 was in a

state of flux," Roadway Br. at 30, is completely refuted by the hundreds of

cases holding § 1981 applicable to all aspects of employment. Virtually

every federal judge in the United States who dealt with the issue prior to

Patterson held that § 1981 prohibited discriminatory discharge. In every

area of the law, no matter how settled, there is always some disagreement.

But the two lone district court cases upon which Roadway relies do not

change the reality that § 1981 was interpreted prior to Patterson to have

(continued...)

6

The overwhelming majority of the members of

Congress who spoke about the provision that was finally

enacted as § 101 characterized it as restorative. Appendix F

(listing references to § 1981 as rejecting Patterson to restore

prior law).7 8

II. THIS COURT SHOULD REAFFIRM BRAD LEY V

RICHMOND SCHOOL BOARD, AND APPLY § 101

HERE

If the statutory language is held to be unclear, the

question is what default rule of statutory applicability governs:

the established rule of Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416

U.S. 696 (1974), and Thorpe v. Housing Authority o f Durham,

393 U.S. 268 (1969), that new statutes generally do apply, or

a new rule purposed by respondents under which they might

not. Roadway urges the Court to overrule Bradley and

7(... continued)

the same coverage as it does amended by § 101. The court in Minority

Police Officers v. City o f South Bend, 617 F. Supp. 1330, 1352, n. 52

(N.D.Ind. 1985), was uncertain whether even the Fourteenth Amendment

prohibited intentional race discrimination in public employment. The

court in Williams v. Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Ry., 627 F. Supp. 752,

757, n. 5 (W.D.Mo. 1986), actually acknowledged the prevailing

assumption that Title VII and § 1981 "run parallel, except for the more

liberal damage potential of § 1981," and cited circuit court precedent to

that effect.

8 The fact that the statute as it was enacted says that it "expands"

and provides "additional" protections is not inconsistent with its

restorativeness, nor is President Bush’s reference to "expanded

protections." Viewed relative to the law immediately prior to passage of

the Act in 1991, the law did "expand" and "add" to § 1981 beyond the

contours Patterson accorded it. Viewed relative to the law as it stood prior

to Patterson, however, the 1991 Act restored § 1981. This wording does

not in any way affect the universality of congressional opinion that § 101

was, and was meant to be, restorative, and the necessary conclusion that

§ 101 should be applied here.

7

Thorpe. Respondents rely primarily on the concurring

opinion of Justice Scalia in Bonjomo. Under Justice Scalia’s

rule, new laws should be presumed to apply to pending cases

only where such application is deemed to be "prospective,"

but not where it would have a "retroactive" effect. 494 U.S.

at 841. Because the rule urged by Justice Scalia is contrary

to established law and is entirely unclear in scope, this Court

should reaffirm Bradley.

A. The Default Rule Respondents Advocate Would

Require the Courts to Make Difficult and

Unguided Distinctions Between New Statutes that

Apply to Pending Cases and New Statutes that Do

Not

Notwithstanding important disagreements about the

proper default rule, the parties agree about at least two

points: First, all agree that laws which render illegal conduct

which was legal when it was engaged in, or which eliminate

vested rights (such as property interests or accrued causes of

action), presumptively apply only to conduct occurring after

the new rule is adopted. Under Justice Scalia’s rule,

application of new laws under these circumstances would be

among the types of conduct labelled "retroactive." Under

Bradley, such application would be manifestly unjust.

The second point of agreement is that there is some

category of new laws which presumptively do apply to pre

enactment claims. Justice Scalia proposes to define the word

"retroactive" in such a way that application of some new laws

to pending cases would not be labelled "retroactive."9 Such

5 Roadway asserts that Rivers and Davison committed semantic

suicide by conceding that application of § 101 should be labelled

"retroactive," Roadway Br., at 13, but this assertion is simply false.

Petitioners in their brief, including at the pages cited by Respondent,

(continued...)

8

non-retroactive applications arguably include the attorneys’

fees statute at issue in Bradley,* 10 as well as at least some

procedural and other rules.11 Under Bradley, the category

of cases in which applications of new laws is presumptively

correct includes all laws the application of which would not

produce a manifest injustice, which has consistently been

understood to refer to changes in procedural and remedial

laws. See Appendix G. In essence, what the parties agree

about is simply that there are two categories of new laws —

those which presumptively apply to pending cases, and those

which presumptively do not. The dispute here concerns

where to draw the line between those two categories.

Respondents and Justice Scalia attack Bradley’’s

manifest injustice exception as a mechanism by which "[a]

rale of law, designed to give statutes the effect Congress

intended, has . . . been transformed to a rule of discretion,

giving judges power to expand or contract the effect of

legislative action." Bonjomo, 494 U.S. at 857, cited in

Roadway’s Br. at 49. This contention is baseless, for at least

two reasons:

First, the lower federal courts have implemented this

standard for over a century. The experience of the lower

’(...continued)

consistently pose the question as whether § 101 applies to their pending

claims, not as whether § 101 should be given "retroactive" effect. E.g.

Petitioners’ Br. at 9, 14.

10 See Bonjomo, 494 U.S. at 849 (Scalia, J., concurring).

11 See, e.g. Brief for the American Trucking Associations, et al, as

Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, at 18 (stating that "it may be that

most procedural changes are unlikely to have any retroactive effect (i.e. to

change the consequences of prior conduct) and may routinely be applied

to pending cases.... Application of such changes to pending cases have [sic]

only prospective effects").

9

courts has established a clear and workable distinction

between procedural and remedial changes in the law on one

hand and changes affecting vested rights or substantive

standards of conduct. See Appendix H; Appendix G. The

principal source of confusion is Justice Scalia’s own assertion

in his concurrence in Bonjomo that Bradley was an

aberration. See e.g., Appendix to Petition for Certiorari in

Landgraf v. USI Film Products, Inc., No. 92-757 (listing cases

applying and not applying the 1991 Civil Rights Act to

pending cases).

Second, this Court itself commonly uses a virtually

identical "justice" standard in its orders instructing lower

courts when to apply new rules to pending cases, presumably

finding it to be a clear standard for application of new rules

to pending cases. See Appendix I (listing orders applying new

rules to pending cases "insofar as just and practicable", or

unless doing so "would not be feasible or would work

injustice"). Justice Scalia himself has approved at least four

such orders, including one on April 17, 1990 — just two

weeks before the Bonjomo decision.

In place of the rule reaffirmed in Bradley, which has

been administered by the lower courts for over a century

without difficulty, Justice Scalia proposes an entirely new rule.

Justice Scalia’s rule will turn on an as-yet-to-be articulated

definition of the term "retroactive." Justice Scalia himself

concedes that adoption of his rule would "n o t... always make

it simple to determine the application in time of new

legislation." Id. at 857. Among the admitted problems with

his proposed approach is that "[i]t will remain difficult, in

many cases ... to decide whether a particular application is

retroactive." Id. Respondents and their amici repeatedly

assert that Justice Scalia’s rule is a clear, "bright-line" rule.

On the contrary, it is an unexplained rule with unforeseeable

consequences.

10

Respondents and Justice Scalia urge that the rule

against "retroactivity" in Bowen v. Georgetown Univ. Hosp.,

488 U.S. 204, 208 (1988), applies to changes in procedural

and remedial laws. Bowen held that "retroactive" rules could

not be promulgated without express statutoiy authority, but

this holding cannot include procedural and remedial rules.

Despite Bowen, and the absence of express authorization for

retroactive rulemaking in the Rules Enabling Act,12 this

Court has itself consistently ordered that amendments to the

Federal Rules be applied in pending cases. See Appendix I

(listing United States Supreme Court Orders applying new

rules to pending cases). These orders would be entirely

inconsistent with Bowen unless Bowen’s, dictate against

"retroactivity" did not extend to procedural changes in

governing law, but rather comported with Bradley in

presuming that such changes are applicable in pending cases.

Even under Justice Scalia’s rule against retroactive

application of new laws, § 101 should be applied here because

the changes that § 101 would cause in this case are not

"retroactive." Rivers and Davison seek application of § 101’s

procedures and remedies in a trial which has not yet

occurred. As explained in our opening brief, what is at stake

here is whether the right to a jury trial and damages under

§ 1981 as amended by § 101 will apply in a retrial of

plaintiffs’ discharge claims on a remand for a trial on these

claims that will occur in any event. Pet. Br., at 9. Whether

a jury will hear the discharge claims is a question that relates

to procedures for conducting a trial in the future. Similarly,

if the jury finds liability on the discharge claim, whether that

12 28 U.S.C. § 2027(a) grants the Court "power to proscribe general

rules of practice and procedure and rules of evidence for cases in the

United States district courts (including proceedings before magistrates

thereof) and courts of appeals." It includes no express grant of power to

apply new rules retroactively.

11

juiy will calculate only the extent of lost wages, or whether it

will also compensate for other harm the discrimination caused

the plaintiffs, is a question relating to the standard for a

decision that the jury has yet to make. Thus, under either

rule, § 101 should apply.

B. Bradley Was Consistent With Prior Law

In his concurrence in Bonjomo, Justice Scalia argued

that Bradley was inconsistent with prior decisions. As we set

forth below and in related Appendices, Bradley was in fact

fully consistent with the law prior to 1974. In reading

decisions prior to Bradley, it is important to bear in mind that

the way in which the courts used the term "retroactive"

changed over time. In the nineteenth century, the courts

generally used the term "retroactive" to refer only to those

laws which they believed should not apply to pre-enactment

claims. The courts labelled "retroactive" laws which, if

applied, would have eliminated accrued causes of action or

impaired vested rights. Application of new remedial and

procedural laws was termed "prospective," or "non

retroactive." "Retroactive" was then, much like "ex post facto"

is today, a conclusory label applied to those categories of

statutes which the courts believed did not properly apply to

pending cases.

The traditional prohibition against "retroactive" laws

is consistent with Bradley as elaborated in Bennett. See

Petitioners’ Br. at 39-45. It was when the courts began to use

the term "retroactive" to refer more generally to any

application of new law to pending cases that the default rule

was properly articulated as favoring retroactive application of

new laws in certain circumstances. See, e.g., Larkin v.

Saffarans, 15 F. 147, 150 (C.C. W.D. Tenn. 1883) (remedial

laws); Bowles v. Strickland, 151 F.2d 419, 420 (5th Cir. 1945)

(procedural laws). In sum, a rule recognizing the distinction

between applicability of new substantive laws and new

12

procedural or remedial changes has been made consistently

for more than a century, and all that has changed is the

language used to describe that rule.

1. Supreme Court Cases

We set forth in our opening brief Supreme Court

cases preceding Bradley which held that changes in procedural

and remedial rules presumptively apply to pending cases. Pet.

Br. at 31-36. We set forth below other authorities.

2. Court of Appeals Decisions

For almost a century prior to Bradley, and for the two

decades since, the lower federal courts consistently recognized

and regularly implemented a distinction between changes in

substantive obligations and changes in remedies or

procedures. One of the earliest decisions observed that the

presumption in favor of application of procedural and

remedial rules to existing claims was "in accordance with the

general rule that all remedial legislation shall be liberally

construed, and particularly should this be so where new

remedies are given." Larkin v. Saffarans, 15 F. 147, 150

(C.C. W.D. Tenn. 1883). That presumption in favor of

applying changes in procedure was understood to refer

broadly to "the procedural machinery provided to enforce"

existing rights. Bowles v. Strickland, 151 F.2d 419, 420 (5th

Cir. 1945). The distinction between the two presumptions

was, as one court put it, "settled rule" long before Bradley.

Dargel v. Henderson, 200 F.2d 564, 566 (Em. Ct. App. 1952).

Among the pre-Bradley circuit court opinions on this issue,

there does not appear to be a single dissent. Under this long-

established distinction, statutes providing for more complete

relief for conduct that was already actionable were construed

to apply to pending claims. See Appendix H.

3. Treatises

Justice Scalia in Bonjomo quotes Chancellor Kent’s

13

statement that "it cannot be admitted that a statute shall, by

any fiction or relation, have any effect before it was actually

passed." Bonjomo, 494 U.S. 855 (Scalia, J., concurring),

quoting J. Kent, Commentaries on American Law *455. But

Chancellor Kent goes on to explain that his objection is to a

law "affecting and changing vested rights," and emphasizes

that the doctrine quoted by Scalia

is not understood to apply to remedial statutes,

which may be of a retrospective nature,

provided they do not impair contracts, or

disturb absolute vested rights, and only go to

confirm rights already existing, and in

furtherance of the remedy ... adding to the

means of enforcing existing obligations.

Commentaries on American Law at *455-*456 (Emphasis

added). Justice Scalia also quotes Justice Story’s statement

that

retrospective laws are ... generally unjust; and

... neither accord with sound legislation nor

with the fundamental principles of the social

compact.

108 L. Ed. 2d at 856, quoting J. Story, Commentaries on the

Constitution, § 1398 (1851). Respondents rely on the same

quotation. Roadway Br. at 9. But Justice Story himself

defined "retrospective law" not to refer to any new statute

affecting pending cases, but as a

statute which takes away or impairs vested

rights acquired under existing laws, or creates

a new obligation, imposes a new duty, or

attaches a disability, in respect to transactions

or considerations past.

Society v. Wheeler, 2 Gall. 139 (1814). Over a century ago the

Supreme Court read Justice Story’s definition to mean that a

14

statute providing a new remedy to enforce an existing right

was not, even as applied to a pre-Act violation, a "retroactive

law." Sturges v. Carter, 114 U.S. 511, 519 (1885). By the end

of the nineteenth century, treatises uniformly made this

distinction. See Appendix I. The article by Instructor Smead

on which Justice Scalia and Respondents relied is expressly

about statutes which, if applied in pending cases, would

eliminate vested rights.13

4. State Constitutions and Laws

Justice Scalia noted in Bonjomo that a number of state

constitutions contain express prohibitions against "retroactive"

laws. 494 U.S. at 856. These state provisions have long been

construed, however, in a manner consistent with pre-Bradley

federal decisional law, not to forbid new legislation at

provided different remedies or procedural mechanisms to

enforce pre-existing obligations. See Appendix K. Cases

from other states also support the distinction upon which

petitioners rely. See Appendix L. Judge Kent’s opinion in

Dash v. Van Kleck is expressly limited to statutes which alter

vested rights. 5 Am. Dec. 291, 308, 309, 310, 312 (1811)

(opinion of Kent, J.); see also, id, at 302, 303, 306 (opinion of

Thompson, J.).

5. English Cases

Respondents contend that their rule "has an ancient

lineage," Roadway Br. at 9, but it is clear that the distinction

between statutes altering standards of conduct or vested

rights and statutes affecting procedures and remedies for

enforcing those standards and rights was established in Great

Britain by the mid-nineteenth century. The leading case was

Wright v. Hale, 6 Hurl. & Norm. 226 (Ct. Exchequer 1860),

13 Smead, The Rule Against Retroactive Legislation: A Basic Principle

o f Jurisprudence, 20 Minn. L. Rev. 775, 781, n. 22 (1936).

15

which applied to pending cases a newly enacted statute

limiting awards of costs. Baron Pollock explained that

"[t]here is a considerable difference between new enactments

which affect vested rights and those which merely affect the

procedure in courts of justice, such as those relating to the

service of proceedings, or what evidence must be produced to

prove particular facts.... Rules as to the costs to be awarded

in an action are of that description, and are not matters in

which there can be vested rights."14 English common law

does not support the rule respondents advocate, which would

reject application of any new rule that alters a party’s expense

associated with past conduct.

6. Prior Views of Respondent’s Counsel

Counsel for Respondent Roadway argues with great

force that Bradley is bad law, and has been repudiated by the

Supreme Court in cases such as Bowen and Bennett. The

same counsel told the Senate in May 1990, however, precisely

the opposite. He described Bradley as governing law under

14 6 Hurl. & Norm, at 230-31; see also id. at 231-32 (Channel, B.)

("In dealing with acts of parliament which would have the effect of taking

away rights of action, we ought not to construe them as having a

retrospective operation, unless it appears clearly that such was the

intention of the legislature; but the case is different where the Act merely

regulates practice and procedure"); Kimbray v. Draper, 3 Q.B. (L.R.) 160,

163 (Q.B. 1868) (Blackburn, J.) ("When the effect of an enactment is to

take away a right, prima facie it does not apply to existing rights; but

where it deals with procedure only, prima facie it applies to all actions

pending as well as future"); Towler v. Chatterton, 6 Bing. 258 (Ct. Com.

Pleas. 1829) (applying to pending case new statute regarding evidence

needed to place case outside limitations period); Cox v. Thomason, 2 C.

& J. 498 (Ct. Exch. 1832) (applying to pending case new rule of court

regarding taxation of costs). In Freeman v. Moyers, 1 A. & E. 338 (K. B.

1834), (holding applicable to pending cases a new statute rendering certain

unsuccessful plaintiffs liable for costs).

16

which, as petitioners here contend, new laws that affect

procedures and remedies are presumptively applicable to

pending litigation. See Appendix M.

C. Section 101’s Remedial and Procedural Nature is

Unaffected By Whether § 1981 is "A Distinct

Positive Law" From Title VII

Roadway does not contend that discriminatory

discharge was legal at the time it fired Rivers and Davison.

Because race discrimination in any aspect of employment,

including discharge, was prohibited under Title VII when

Roadway discharged Rivers and Davison, applying § 101 here

to authorize a jury trial and damages for the discharge claim

simply applies additional remedies and procedures for

conduct which has at all times been illegal. Whether § 1981,

as amended by § 101, is a "separate" or "distinct positive" law

from Title VII does not affect the fact that application of

§ 101 here is remedial. Cf. Pennsylvania v. Union Gas Co.,

491 U.S. at 8, n. 2 (reading separately enacted legislation "in

combination") (emphasis in original). The location of the

codification of § 1981 and Title VII in the statute books is

not determinative of whether application of the § 101 jury

trial and damages provisions in this case is remedial.15

13 Even if where § 101 is codified were determinative, § 101 is

properly viewed as remedial of discrimination prohibited by Title VII.

Title VII and § 1981 are both codified in Chapter 21 of Title 42 of the

United States Code. Section 101 is codified as § 1981(b). The 1991 Act

expressly recognizes the interrelationship between § 1981 and Title VII by

codifying the new Title VII damages provisions at § 1981A. Roadway’s

position is thus reduced to a contention that plaintiffs could prevail only

if Congress had also moved § 2000e-5(a) of Title VII to make it part of

§ 1981. Only the most arbitrary and unworkable doctrine would make

such a detail of statutory compilation determinative of whether § 101

applies to pending discrimination claims.

17

The federal courts have overwhelmingly rejected

Roadway’s reasoning that, where the substantive conduct at

issue was prohibited when engaged in, a new remedy does not

apply if the preexisting prohibition was established by a

different law from that in which the remedy was announced.

See Appendix N. The very cases upon which Roadway relies

support the conclusion that § 101 provides additional

remedies for employment discrimination which Title VII also

prohibits. See Roadway Br. at 27-29. For example, this

Court in Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454

(1975), characterized § 1981 as "a remedy," id. at 466, and

referred to Title VII as conferring "remedies" that are co

extensive with § 1981, id. at 459, and to Title VII and § 1981

as "two procedures" for enforcing the same rights. Id.16

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, 415 U.S. 36 (1974), similarly

emphasized that legislative enactm ents in the

nondiscrimination area, specifically including Title VII and

§ 1981, "have long evinced a general intent to accord parallel

or overlapping remedies against discrimination." Id. at 47.

Roadway mischaracterizes the issue presented by this

case when it asks whether § 101 should be applied to

"conduct which was adjudicated to be non-discriminatory

prior to the date on which Section 101 became law," Roadway

Br. at i, or to "trials occurring before the date of its

enactment." Id. at iii, iv, 8, 13, 26; see id. at 14. The question

is not whether § 101’s new remedies could require a new trial

of claims that were properly tried under pre-Act law, but

16 See e.g. Patterson v. McLean Credit Union, 491 U.S. 164 (1989)

(referring repeatedly to the different "remedies" and the "procedures"

§ 1981 and Title VII provide for the same conduct); United States v. Burke,

112 S.Ct. 1867, 1873 (1992) (explaining that "the circumscribed remedies

available under Title VII stand in marked contrast... to those available ...

under other federal antidiscrimination statutes....") (emphasis supplied).

18

whether § 101 should be applied to a new trial which will

occur in any event, without regard to whether § 101

applies.17

17 Although it declined to apply § 101, the Sixth Circuit remanded

the § 1981 retaliatory discharge claim for trial on the ground that the

district court’s dismissal of that claim turned on a misapplication of

Patterson. On remand, the jury — to which plaintiffs are already entitled

on the retaliation claim under Patterson, even apart from § 101 ■— may

find that Roadway did discriminate against the plaintiffs in their efforts to

enforce their contract rights. If the jury so finds, then the district court’s

factual finding of non-discrimination under Title VII cannot collaterally

estop the jury’s verdict, but will have to be vacated and a new Title VII

judgment entered consistent with the jury’s verdict. Lytle v. Household

Mf gInc . , 494 U.S. 545 (1990), cited in Hatvis v. Roadway Express, 973

F.2d 490, 495 (6th Cir. 1992), P.A. 9a-10a. Respondents did not raise for

consideration by this Court any issue of collateral estoppel. Cf

Leatherman v. Tarrant County, 113 S. Ct. 1160, 1162 at n. 1 (1993).

Roadway suggests that the district court’s Title VII determination

on the claim of discriminatory discharge would not be reopened because

"the court of appeals did not purport to remand on those claims; it

remanded only on the retaliation claims." Roadway Br., at 4 n. 1. As the

Court of Appeals recognized in its opinion, however, if the jury’s

determination on the common issues of fact relating to racial motive

differs from the judge’s, the Seventh Amendment requires that the jury’s

determination prevail. The district court will then have to vacate the

inconsistent Title VII determination. If the 1991 Act applies here, the jury

will determine the discharge claim as well as the retaliation claim, and

determine the propriety of damages on each; if not, the court will enter

a judgment on discharge. It is thus not a "free-standing jury trial right,"

Roadway Br. at 35, which Rivers and Davison assert, but a right to have

a jury on claims when those claims are to be adjudicated in any event.

The appellate court’s failure to vacate the Title VII judgment

does not affect plaintiffs’ rights under Lytle. It could well have been

considered premature for the court of appeals, rather than the district

court on remand, to vacate the Title VII judgment. If the jury decides

that no discrimination occurred, the Title VII judgment need not be

disturbed.

19

III. THIS COURT SHOULD NOT RETROACTIVELY

CHANGE RULES ABOUT STATUTORY

APPLICABILITY UPON WHICH CONGRESS HAS

RELIED

There is probably no area of the law where stare

decisis is of such practical importance, and so vital to

preserving the proper balance between Congress and the

courts, as the rules of statutory construction. The rules of

construction are a critical part of the context in which

Congress legislates; they control the terms, syntax and

structure which Congress must use to achieve a desired result.

Changing a rule of construction would be as disruptive of the

law-making process as a decision to change by judicial fiat the

meaning of a word commonly used in federal statutes. The

truism that Congress is presumed to legislate with a

knowledge of the law is particularly important, and realistic,

with regard to the principles of statutory construction.

Over the course of the last two decades, congressional

reports and individual members of Congress have repeatedly

referred to Bradley as establishing the rule of interpretation

regarding pre-Act claims. See Appendix O. Since 1974,

Congress has enacted more than 5000 Public Laws

encompassing 40,000 pages of Statutes at Large. Stat. at

Large, vols. 89-106. In the vast majority of these statutes,

Congress chose not to attempt to specify expressly which

provisions would and would not apply to pre-existing cases,

but decided instead to let that issue be determined through

judicial application of established legal principles. To now

alter the rules of interpretation applicable to those statutes

would wreak havoc with the intent and expectations of

Congress.

Bradley has proved to be a highly accurate method of

ascertaining congressional intent. Despite the frequency with

which this issue has arisen in the courts, it appears that

20

Congress has never overturned by legislation any of the

circuit court decisions before or after Bradley regarding the

applicability of particular statutes to pre-Act claims. Justice

Scalia’s concurrence in Bonjomo now proposes, paradoxically,

that the Court announce — and apply retroactively — a new

rule against the retroactive application of new rules.

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the court of appeals should be

reversed insofar as it did not apply the Civil Rights Act of

1991 petitioners’ pending claims.

Respectfully submitted,

C h a r l e s St e p h e n R a l s t o n

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

August 10, 1993

APPENDICES

INDEX TO APPENDICES

A1 Appellate Cases in Which the United States

Has Sought to Apply a New Statute to a Pre-

Existing Claim

B A p p e lla te D ecisions U pon W hich

Respondents Rely Construing "Take Effect

Upon Enactment"

C United States Supreme Court Decisions

Applying the Canon of Construction that No

Word in a Statute Should be Read to Be

Redundant

D United States Supreme Court Decisions

Recognizing the Canon of Construction

"Expressio Unius Est Exclusio Alterius"

E Lower Federal Court Decisions Prior to

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Interpreting

42 U.S.C. § 1981 to Cover All Conduct

Covered by § 1981 as Amended By § 101 of

the Civil Rights Act of 1991

F Legislative History References to § 101 as

Restoring Pre-Patterson Interpretation of

§ 1981

G Court of Appeals Decisions Since Bradley v.

Richmond Sch. Bd. Applying Statutes

Affecting Remedies and Procedures to

Pending Cases

APPENDIX DESCRIPTION

This was an Appendix to Petitioners’ opening brief.

2a

H Court of Appeals Decisions Prior to Bradley v.

Richmond Sch, Bd. Recognizing a Distinction

Between New Laws Affecting Standards of

Conduct or Vested Rights, Which Were

Presumed Inapplicable to Pending Cases, and

Methods for Enforcing Existing Rights, Which

Were Presumed Applicable

I United States Supreme Court Orders

Applying New Rules to Pending Cases Absent

Injustice

J Old Treatises Recognizing the Rule in Favor

of Application of New Remedial Procedural

and Restorative Statutes to Pending Cases

K Colorado, Montana, New Hampshire, and

Ohio Cases Interpreting the Respective State

C onstitu tional Provision P roh ib iting

"Retroactive" Statutes

L Other State Cases Interpreting Prohibitions

on "Retroactive" Statutes

M Prior View of Roadway Counsel Glen D.

Nager Expressed in Legislative History of

Civil Rights Act of 1991

N Court of Appeals Decisions Applying New

Statutes Providing Additional Remedies for

Conduct Already Illegal Under Other Law

O Decisions Citing to Legislative History In

Which Members of Congress Expressed Their

Reliance on Bradley v, Richmond School Bd.

APPENDIX B

Appellate Decisions Upon Which Respondents Rely

Construing "Take Effect Upon Enactment"

Court held phrase did not resolve applicability:

1. Leland v. Federal Ins. A d m ’r, 934 F.2d 524, 529 (4th

Cir.) cert, denied, 112 S. Ct. 417 (1991) (giving

credence to Bradley and analyzing question without

regard to statutory language about application upon

enactment, but rather concluding that no

congressional intent "is discernible from [Jeither the

language of the amendment itself []or from any other

indication of congressional intent")

2. Jensen v. Gulf Oil Refining & Marketing Co., 623 F.2d

406, 409 (5th Cir. 1980) (relying on Bradley and

holding "we do not find the statement that the

amendment prohibiting involuntary retirement before

age sixty-five shall take effect upon enactment

dispositive") (emphasis added).

3. Sikora v. American Can Co., 622 F.2d 1116,1120 (3rd

Cir. 1980) (citing Bradley in its exposition of the law

and stating "we turn to the statute under

consideration and find its language equivocal.

Congress simply provided that the amendment

prohibiting involuntary retirement before age 65

’shall take effect on the date of enactment of this

Act...’") (emphasis added). 4

4. Yakim v. Califano, 587 F.2d 149, 150-51 (3rd Cir.

1978) (relying on Bradley in holding that language in

§ 20 directing that statute take effect on the date of

enactment gives "no explicit direction on the

retroactivity issue," and proceeding to determine that

B-2

it was a different statutory subsection, § 15(c) which

"indicated] that Congress was aware of the

retroactivity problem and decided to limit such effect

to those cases eligible for a fresh review under the

Reform Act")(emphasis added).

Court also relied on different statutory language:

5. Condit v. United Air Lines, Inc., 631 F.2d 1136, 1140

(4th Cir. 1980) (citing Bradley, but deciding based on

text that the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, which in

addition to stating that it shall take effect upon

enactment states that it "shall not apply to any fringe

benefit program or fund, or insurance program which

is in effect on the date of enactment of this Act until

180 days after enactment of this Act," is inapplicable

where it would impose liability for actions under a

fringe benefit program which occurred 7 years prior

to the Act).

6. Schwabenbauer v. Board o f Education, 667 F.2d 305,

310 n. 7 (2d. Cir. 1981) (relying on Condit and the

same additional statutory language considered there

in order not to apply the Pregnancy Discrimination

Act where it would have "invalidated past conduct").

APPENDIX C

United States Supreme Court Decisions

Applying the Canon of Construction that

No Word in a Statute Should be Read to be Redundant

1. Sale v. Haitian Centers Council Inc., 113 S. Ct. 2549

(1993)

2. United States v. Nordic Village, Inc., 112 S. Ct. 1011,

1015 (1992)

3. Liljeberg v. Health Services Acquisition Corp., 486

U.S. 847, 859-60 n.8 (1988)

4. Mackey v. Lanier Collection Agency and Serv., Inc.,

486 U.S. 825, 837 (1988)

5. Kungys v. United States, 485 U.S. 759, 778 (1988)

6. Mountain States Tel. and Tel. Co. v. Pueblo o f Santa

Ana, 472 U.S. 237, 249 (1985)

7. Securities Industry A ss’n v. Bd. o f Governors o f

Federal Reserve System, 468 U.S. 207, 165 (1984)

8. Jewett v. Commissioner o f Internal Revenue, 455

U.S. 305, 315 (1982)

9. Colautti v. Franklin, 439 U.S. 379, 392 (1979)

10. Colgrove v. Battin, 413 U.S. 149, 184 (1973)

11. United States v. Menasche, 348 U.S. 528, 538-39

(1955)

12. Shapiro v. United States, 335 U.S. 1 (1948)

C-2

13. Singer v. U.S., 323 U.S. 338, 344 (1945)

14. Montclair v. Ramsdell, 107 U.S. 147, 152 (1883)

15. Market Co. v. Hoffman, 101 U.S. 112, 115-16 (1879)

APPENDIX D

United States Supreme Court Decisions

Recognizing the Canon of Construction

"Expressio Unius Est Exclusio Alterius"

1. Crosby v. United States, 506 U .S ,___, 122 L Ed. 2d

25, 30 (1993)

2. Leatherman v Tarrant County, 507 U .S .___, 122 L.

Ed. 2d 517, 524 (1993)

3. Sullivan v. Hudson, 490 U.S. 877, 891-93 (1989)

4. United States v. Wells Fargo Bank, 485 U.S. 351, 357

(1988)

5. California Coastal Comm’n v. Granite Rock Co.,

480 U.S. 572, 600 (1987)

6. Herman & MacLean v. Huddleston, 459 U.S. 375,

387 n.23 (1983)

7. Becker v. United States, 451 U.S. 1306, 1309 (1981)

8. Transamerica Mortgage Advisors, Inc. v. Lewis, 444

U.S. 11, 30 n.6 (1979) (White J., dissenting)

(criticizing the majority for implicitly applying the

canon, but recognizing the canon except where it

would constrict a statute’s remedial purpose)

9. Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153, 188

(1978)

10. National R.R. Passenger Corp. v. National A ss’n o f

R.R. Passengers, 414 U.S. 453, 458 (1974)

D-2

11. Evans v. Newton, 382 U.S. 296, 311 (1966) (White

J., concurring)

12. Nashville Milk Co. v. Carnation Co., 355 U.S. 373,

375-76 (1958)

13. Wilko v. Swan, 346 U.S. 427, 434 n.18 (1953)

14. SEC v. C.M. Joiner Leasing Corp., 320 U.S. 344, 350

(1943)

15. Neuberger v. Commissioner o f Internal Revenue, 311

U.S. 83, 88 (1940)

16. Ford v. United States, 273 U.S. 593, 611 (1927)

17. United States v. Barnes, 222 U.S. 513, 518-19 (1912)

18. Bend v. Hoyt, 38 U.S. 263, 271 (1839)

19. United States v. Arredondo, 31 U.S. 691, 724-25

(1832) (applying the canon).

APPENDIX E

Lower Federal Court Decisions Prior to

Patterson v. McLean Credit Union Interpreting

42 U.S.C. § 1981 to Cover All Conduct Covered by § 1981

as Amended By § 101 of the Civil Rights Act of 1991

FIRST CIRCUIT

Oliver v. Digital Equipment Corp., 846 F.2d 103 (1st Cir.

1988) (discharge; harassment; terms and conditions).

Rowlett v. Anheiser-Busch, Inc., 832 F.2d 194 (1st Cir.

1987) (discharge; retaliation).

Springer v. Seaman, 821 F.2d 871 (1st Cir. 1987)

(discharge).

Bums v. Sullivan, 619 F.2d 99 (1st Cir. 1980) cert, denied

449 U.S. 893 (1980) (promotion denial).

DeGrace v. Rumsfeld, 614 F.2d 796 (1st Cir. 1980)

(discharge; harassment)

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F.2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972) (hiring;

recruitment)

Townsend v. Exxon Company, U.S.A., 420 F. Supp. 189

(D.Mass. 1976) (refusal to rehire; discharge)

SECOND CIRCUIT

Tach v. Chemical Bank, 849 F.2d 775 (2nd Cir. 1988)

(retaliatory discharge).

E-2

Lopez v. S.B. Thomas, Inc., 831 F.2d 1184 (2d Cir. 1987)

(constructive discharge; harassment).

De Cintio v. Westchester County Medical Center, 821 F.2d

111 (2d Cir. 1987) (retaliation; discharge).

Hill v. Coca-Cola Bottling Co. o f N.Y., 786 F.2d 550 (2d

Cir. 1986) (discharge).

Martin v. Citibank, N.A., 762 F.2d 212 (2nd Cir. 1985)

(discharge).

Grant v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 622 F.2d 43 (2d Cir. 1980)

(retaliation).

Hudson v. International Business Machines, Inc., 620 F.2d

351 (2d Cir. 1980) cert, denied, 449 U.S. 1066 (1980)

(retaliation).

Powell v. Syracuse University, 580 F.2d 1150, cert, denied

439 U.S. 984 (1978) (2d Cir. 1978) (discharge).

Brown v. Ralston Purina, 557 F.2d 570 (2d Cir. 1975)

(discharge).

Carrion v. Yeshiva University, 535 F.2d 722 (2d Cir. 1976)

(discharge; promotion denial).

DeMatteis v. Eastman Kodak Co., 511 F.2d 306 (2d Cir.

1975). (discharge; retaliation).

Williams v. State University o f N.Y., 635 F. Supp. 1243

(E.D.N.Y. 1986) (discharge).

Almendral v. New York State Office o f Mental Health, 568

F. Supp. 571 (S.D.N.Y. 1983) aff’d in relevant part, 743

F.2d 953 (2d Cir. 1984) (promotion denial; discharge;

retaliation)

E-3

Ingram v. Madison Square Garden Center, Inc., 482 F.

Supp. 414 (S.D.N.Y. 1979) (hiring; terms and conditions;

promotion denial).

Patterson v. United Federation o f Teachers, 480 F. Supp.

550 (S.D.N.Y. 1979) (failure to represent).

Williams v. Interstate Motor Freight System, 458 F. Supp. 20

(S.D.N.Y. 1978) (discharge).

Lee v. Bolger, 454 F. Supp. 226 (S.D.N.Y. 1978)

(promotion denial).

THIRD CIRCUIT

Kelly v, Tyk Refractories Co., 860 F.2d 1188 (3rd Cir. 1988)

(discharge; constructive discharge).

Roebuck v. Drexel University, 852 F.2d 715 (3rd Cir. 1988)

(failure to grant tenure).

Lewis v. University o f Pittsburgh, 725 F.2d 910 (3rd Cir.

1983) cert, denied 469 U.S. 892 (1984) (promotion denial).

Wilmore v. City o f Wilmington, 699 F.2d 667 (3rd Cir.

1983) (promotion denial).

Walton v. Eaton Corp., 563 F.2d 66 (3rd Cir. 1977)

(discharge; harassment)

Wilson v. Sharon Steel Corp., 549 F.2d 276 (3rd Cir. 1977)

(discharge; terms and conditions).

Commonwealth o f Pa. v. Flaherty, 404 F. Supp. 1022 (W.D.

Pa. 1975) (hiring).

E-4

FOURTH CIRCUIT

Sharma v. Lockheed Engineering & Mgmt. Services, Co.,

Inc. 862 F.2d 314 (4th Cir. 1988) (discharge).

Hughes v. International Business Machines Corp., 848 F.2d

185 (1988) (promotion denial; terms and conditions)

Lilly v. Harris-Teeter Supermarket, 842 F.2d 1496 (4th Cir.

1988) (promotion denial; terms and conditions).

Crawford v. College Life Insurance o f America, 831 F.2d

1057 (4th Cir. 1987) (discharge)

McCausland v. Mason County Board o f Education, 649

F,2d 278 (4th Cir. 1981) cert, denied 454 U.S. 1090

(discharge).

Sledge v. I P Stevens & Co., 585 F.2d 625 (4th Cir. 1978)

cert, denied 440 U.S. 981 (1979) (hiring; promotion denial;

recall; terms and conditions).

Reynolds v. Abbeville County School District No. 60, 554

F.2d 638 (4th Cir. 1977) (discharge).

Roman v. E.S.B., Inc., 550 F.2d 1343 (4th Cir. 1976)

(discharge; hiring)

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 535 F.2d 257 (4th Cir.

1976) cert, denied 429 U.S. 920 (1976) (promotion denial;

hiring).

Day v. Patapapsco & Back Railroad Co., 504 F. Supp. 1301

(D.Md. 1981) (terms and conditions; seniority system)

E-5

FIFTH CIRCUIT

Johnson v. Chapel Hill Independent School District, 853

F.2d 375 (5th Cir. 1988) (failure to rehire; retaliation).

Hernandez v. Hill County Telephone Corp., 849 F.2d 139

(5th Cir. 1988) (hiring; promotion denial; retaliation).

Comeaux v. Unirogal Chemical Corp., 849 F.2d 191 (5th

Cir. 1988) (discharge).

Price v. Digital Equipment Corp., 846 F.2d 1026 (5th Cir.

1988).

Page v. US Industries, Inc., 726 F.2d 1038 (5th Cir. 1984)

(hiring; promotion denial).

Freeman v. Motor Convoy, 700 F.2d 1339 (5th Cir., 1983)

(hiring; seniority).

Adams v. McDougal, 695 F.2d 104 (5th Cir. 1983) (terms

and conditions; failure to rehire).

Williams v. New Orleans Steamship Association, 688 F.2d

412 cert, denied 460 U.S. 1038 (1982) (5th Cir. 1982)

(terms and conditions).

Pinkard v. Pullman-Standard, 678 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir.

1982) cert, denied 459 U.S. 1105 (1983) (discharge;

retaliation).

Payne v. Travenol Lab, 673 F.2d 798 (5th Cir. 1982)

(hiring; promotion denial).

Rivera v. City o f Wichita Falls, 665 F.2d 531 (5th Cir. 1982)

(hiring; promotion denial).

E-6

Bobo v. ITT, Continental Baking Company, 662 F.2d 340

(5th Cir. 1982) cert, denied 456 U.S. 933 (1982)

(discharge).

McWilliams v. Escambia County School Board, 658 F.2d,

326 (5th Cir. 1981) (transfer; demotion; promotion

denial).

Jackson v. City o f Kileen, 654 F.2d 1181 (5th Cir. 1981)

(discharge).

Whiting v. Jackson State University, 616 F.2d 116 (5th Cir.

1980) (discharge).

Crawford v. Western Electric, 614 F.2d 1300 (5th Cir. 1980)

(promotion denial).

Grigsby v. North Mississippi Medical Center, 586 F.2d 457

(5th Cir. 1978) (discharge; promotion denial; terms and

conditions).

Claiborne v. Illinois Central Railroad, 583 F.2d 143 (5th

Cir. 1978) cert, denied 442 U.S. 934 (1979) (promotion

denial; discharge).

Barnes v. Jones County School District, 575 F.2d 490 (5th

Cir. 1978) (discharge; demotion).

Parson v. Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp., 575 F.2d

1374 (5th Cir. 1978) cert, denied 441 U.S. 968 (1979)

(retaliation; promotion denial).

Prophet v. Armco Steel, Inc., 575 F.2d 579 (5th Cir. 1978)

(discharge)

Gamer v. Ciarrusso, 571 F.2d 1330 (5th Cir. 1978)

(retaliation; discharge; terms and conditions).

E-7

Jenkins v, Caddo-Bossier Association for Retarded Citizens,

570 F.2d 1227 (5th Cir. 1978) (discharge; promotion

denial; harassment; hiring)

Turner v. Texas Instruments, Inc., 555 F.2d 1251 (5th Cir.

1977) (discharge).

Harkless v. Sweeny, Ind., 554 F.2d 1353 (5th Cir. 1977) cert,

denied 434 U.S. 966 (1977) (failure to rehire).

Smith v Olin, 535 F.2d 862 (5th Cir. 1976) (discharge).

Faraca v. Clements, 506 F.2d 956 (5th Cir. 1975) cert,

denied 422 U.S. 1006 (1975) (failure to rehire).

Cooper v. Allen, 493 F.2d 765 (5th Cir. 1975) (hiring).

Belt v. Johnson Motor Lines, 458 F.2d 443 (5th Cir. 1972)

(promotion denial; terms and conditions).

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097 (5th Cir.

1970) cert, denied 401 U.S. 948 (1971) (discharge).

Quarles v. Northern Miss. Retardation Center, 455 F. Supp.

52 (N.D. Miss. 1978) aff’d, 580 F.2d 1051 (5th Cir. 1978)

(discharge).

SIXTH CIRCUIT

Erebia v. Chrysler Plastic Products Corp., 863 F.2d 47 (6th

Cir. 1988) (harassment).

Singala v. Electroha Corp., 862 F.2d 316 (6th Cir. 1988)

(discharge).

Simmonds v. Superior Pontiac Cadillac, Inc., 861 F.2d 721

(6th Cir. 1988) (discharge).

E-8

Horton v. Edgcomb Metals Company, 860 F.2d 1079 (6th

Cir. 1988).

Waller v. Thames, 852 F.2d 569 (6th Cir. 1988)

(harassment; constructive discharge).

Hill v. Duriron Company, Inc., 656 F.2d 1208 (6th Cir.

1981) (discharge)

Grano v. Department o f Development, 637 F.2d 1073 (6th

Cir. 1980) (terms and conditions)

Everson v. McLouth Steel Corp., 586 F.2d 6 (6th Cir. 1978)

(discharge)

Winston v. Lear-Siegler, 558 F.2d 1266 (6th Cir. 1977)

(discharge; retaliation)

Long v. Ford Motor Co., 496 F.2d 500 (6th Cir. 1974)

(discharge; terms and conditions; promotion)

Rodgers v. Peninsular Steel Co., 542 F. Supp. 1215 (N.D.

Oh. 1982) (hiring; promotion; harassment)

Hatton v. Ford Motor Co., 508 F. Supp. 620 (E.D. Mich.

1981) (discharge)

McGee v. Grand Rapids, 486 F. Supp. 584 (W.D. Mich.

1980), aff’d, 663 F.2d 1072 (6th Cir. 1981) (discharge)

SEVENTH CIRCUIT

Yarborough v. Tower Oldsmobile, Inc., 789 F.2d 508 (7th

Cir. 1986) (discharge).

E-9

Ramsey v. American Air Filter Co., 772 F.2d 1303 (7th Cir.

1985) (terms and conditions; harassment; layoff;

discharge).

Christensen v. Equitable Life Assurance Society, 767 F.2d

340 (7th Cir. 1985) cert, denied 474 U.S. 1102 (1985)

(constructive discharge).

Mason v. Continental III. National Bank, 704 F.2d 361 (7th

Cir. 1983) (promotion denial).

Ekamen v. Health and Hospitals Corporation o f Marion

County, 589 F.2d 316 (7th Cir. 1978) cert, denied 469 U.S.

821 (1984) (hiring; promotion; terms and conditions;

retaliation)

Flowers v. Cronch-Walker Corp., 552 F.2d 1277 (7th Cir.

1977) (discharge).

Stewart v. General Motors Corp., 542 F.2d 445 (7th Cir.

1976) cert, denied 433 U.S. 919 (1977) (discharge)

Gunn v. Dow Chemical Co., 522 F.Supp. 1172 (S.D. Ind.

1981) (terms and conditions; constructive discharge)

Dawson v. Pastrich, 441 F.Supp. 133 (N.D. Ind. 1977)

(hiring)

EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Tart v. Levi Strauss & Co., 864 F.2d 615 (8th Cir. 1988)

(discharge).

Lassiter v. Covington, 861 F.2d 680 (8th Cir. 1988)

(discharge).

E-10

Estes v. Dick Smith Ford, 856 F.2d 1097 (8th Cir. 1988)

(discharge)

Edwards v. Jewish Hospital o f St. Louis, 855 F.2d 1345 (8th

Cir. 1988) (discharge).

Scoggins v. Bd. o f Education o f the Nashville, Arkansas

Public Schools, 853 F.2d 1472 (8th Cir. 1988) (discharge).

Monroe v. Guardsmark, Inc., 851 F.2d 1065 (8th Cir.

1988). (discharge)

Pacheco v. Advertisers Lithographing, 657 F,2d 191 (8th Cir.

1981) (promotion denial; suspension).

Owens v. Ramsey Corp., 656 F.2d 340 (8th Cir. 1981)

(discharge)

Taylor v. Jones, 653 F.2d 193 (8th Cir. 1981) (discharge).

Johnson v. Bunny Bread Co., 646 F.2d 1250 (8th Cir. 1981)

(discharge; constructive discharge).

Setser v. Novack Investment Co., 638 F.2d 1137 (8th Cir.

1981) (retaliation).

Martin v. Arkansas Arts Center, 627 F.2d 876 (8th Cir.

1980) (discharge)

Middleton v. Remington Arms Co., Inc., 594 F.2d 1210 (8th

Cir. 1979) (discharge)

Hudak v. Curators o f the University o f Missouri, 586 F.2d

105 (8th Cir., 1978) cert, denied 440 U.S. 985 (1979)

(discharge; harassment; terms and conditions)

DeGraffenreid v. General Motors Assembly Division, 558

F.2d 480 (8th Cir. 1977) (discharge)

E -ll

Donaldson v. Pillsbury Co., 554 F.2d 825 cert, denied, 434

U.S. 856 (1977)(8th Cir. 1977) (discharge)

Thompson v. McDonnell Douglas Corp., 552 F,2d 220 (8th

Cir. 1977) (constructive discharge).

Stevens v. Junior College o f St. Louis, 548 F.2d 779 (8th

Cir. 1977) (discharge; retaliation)

Jimerson v. Kisco, 542 F.2d 1008 (8th Cir. 1976)

(discharge).

King v. Yellow Freight Systems, Inc., 523 F,2d 879 (8th Cir.

1975) (discharge)

Payne v. Ford Motor Co., 461 F.2d 1107 (8th Cir. 1972)

(terms and conditions)

Brady v. Bristol Meyers, Inc., 459 F.2d 621 (8th Cir. 1976)

(terms and conditions)

Poindexter v. Kansas City, Mo. Water Dept., 573 F. Supp.

647 (W.D. Mo. 1983) aff’d 754 F.2d 377 (8th Cir. 1984)

(discharge)

Robertson v. Doctor’s Hospital, 570 F.Supp. 663 (E.D. Ark.,

1983) (discharge)

Farrakhan v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 511 F. Supp. 893 (D.

Neb. 1980) (discharge)

Rose v. Eastern Neb. Human Services Agency, 510 F. Supp.

1343 (D. Neb. 1981) (discharge)

Lindsey v. Angelica Corp., 508 F. Supp. 363 (E.D. Mo.

1981) (hiring)

E-12

Madrigal v. Certaineed, 508 F. Supp. 310 (W.D. Mo. 1981)

(discharge)

Metcalf v. Omaha Steel Castings Co., 507 F. Supp. 679 (D.

Neb. 1981) (discharge)

Williams v. Trans World Air Lines, Inc., 507 F. Supp. 293

(W.D. Mo. 1980), aff’d , 660 F.2d 1267 (8th Cir. 1981)

(discharge)

Spearman v. Southwestern Bell, 505 F. Supp. 761 (E.D. Mo.

1980), aff’d 662 F.2d 509 (8th Cir. 1981)

Coleman v. General Motors, 504 F. Supp. 900 (E.D. Mo.

1980), (8th Cir. 1981) (discharge; retaliation)

Taylor v. Jones, 495 F.Supp. 1285 (E.D. Ark., 1980)

(non-renewal; discharge)

Setser v. Novack Investment Co., 483 F. Supp. 1147 (E.D.

Mo. 1980), rev’d on other grounds, 638 F.2d 1137, (8th Cir.

1980), vac’d and amended, 657 F.2d 962 (8th Cir. 1981)

(retaliation; hiring)

Sutton v. Addressograph-Multigraph Corp., 481 F. Supp.

1148 (E.D. Mo. 1979) (discharge)

Buckley v. City o f Omaha, 477 F. Supp. 754 (D. Neb. 1978)

aff’d, 605 F.2d 1078 (8th Cir. 1979)(discharge)

Slotkin v. Human Development Corp., 454 F. Supp. 250

(E.D. Mo. 1978) (retaliation; constructive discharge)

Mixon v. Hanley Ind., 454 F. Supp. 386 (E.D. Mo. 1978),

aff’d, 594 F.2d 869 (8th Cir. 1978) (failure to rehire;

discharge)

E-13

Oliver v. Moberly Missouri School District, 427 F. Supp. 82

(E.D. Mo. 1977) (hiring)

Mopkins v. St. Louis Die Casting Corp., 423 F. Supp. 132

(E.D. Mo. 1976), aff’d, 569 F.2d 454 (8th Cir. 1978)

(discharge)

Jimerson v. Kisco Co., 404 F. Supp. 338 (E.D. Mo. 1976),

aff’d, 542 F.2d 1008 (8th Cir. 1978) (discharge)

NINTH CIRCUIT

Brown v. Boeing Company, 843 F.2d 501 (9th Cir. 1988)

cert, denied, 488 U.S. 865 (1988)(discharge).

Mitchell v. Keith, 752 F.2d 385 (9th Cir. 1985) cert, denied,

M2 U.S. 1028 (1985)(discharge; retaliation)

Wiltshire v. Standard Oil Co., 652 F.2d 837 (9th Cir. 1981)

(discharge)

London v. Coopers & Lyhrand, 644 F.2d 811 (9th Cir.,

1981) (retaliation; discharge)

St. John v. Employment Development Corp., 642 F.2d 273

(9th Cir. 1981) (retaliation; discharge).

Shah v. Mt. Zion Hospital and Medical Center, 642 F.2d

268 (9th Cir. 1981) (discharge; retaliation)

Fong v. American Airlines, Inc., 626 F.2d 759 (9th Cir.

1980) (discharge)

Miller v. Bank o f America, 600 F.2d 211 (9th Cir. 1979)

(discharge).

E-14

Smallwood v. National Can Co., 583 F.2d 419 (9th Cir.

1978) (retaliation; terms and conditions)

Cooper v. Dept, o f Administration, State o f Nevada, 558 F.

Supp. 244 (D. Nev. 1982) (hiring)

Sethy v. Alameda County Water Dist., 545 F.2d 1157 (9th

Cir. 1976) (discharge; harassment)

Chatman v. U.S. Steel, 425 F. Supp. 753 (N.D. Ca., 1977)

(terms and conditions)

TENTH CIRCUIT

Skinner v. Total Petroleum, Inc., 859 F.2d 1439 (10th Cir.

1988) (retaliatory discharge; discriminatory discharge).

McAlester v. United Air Lines, Inc., 851 F.2d 1249 (10th

Cir. 1988) (discharge).

Hicks v. Gates Rubber Co., 833 F.2d 1406 (10th Cir. 1987)

(harassment).

Meade v. Merchants Fast Motorline, Inc., 820 F.2d 1124

(10th Cir. 1987) (discharge).

Whatley v. Scaggo Companies, Inc., 707 F.2d 1129 (10th

Cir. 1983) cert, denied, 464 U.S. 938 (1983) discharge).

Trujillo v. State o f Colorado, 649 F.2d 823 (10th Cir. 1981)

(retaliation; terms and conditions; hiring)

Shah v. Halliburton Co., 627 F.2d 1055 (10th Cir. 1980)

(discharge)

Manzanares v. Safeway Stores, 593 F.2d 968 (10th Cir.

1978) (terms and conditions)

E-15

Zuniga v. AMFAC Foods, Inc., 580 F.2d 380 (10th Cir.

1977) (discharge)

Taylor v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 524 F.2d 263 (10th Cir.

1975) (discharge)

Foster v. M.C.I., 555 F. Supp. 330 (D.Colo. 1983) aff’d, 773

F.2d 1116 (10th Cir. 1985) (discharge)

Whatley v. Skaggs, 502 F.Supp. 370 (D.Colo. 1980), aff’d,

707 F.2d 1129 (10th Cir. 1983) (discharge; demotion)

LaFore v. Emblem Tape & Label, 448 F.Supp. 824

(D.Colo. 1978) (discharge)

Apodaca v. General Electric Corp., 445 F. Supp. 821

(D.N.M. 1978) (discharge)

Enriquez v. Honeywell, Inc., 431 F. Supp. 901 (W.D. Ok.

1977) (terms and conditions)

ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

Baker v. Buckeye Cellulose Corp., 856 F.2d 167 (11th Cir.

1988) (retaliation).

Swint v. Pullman Standard, 854 F.2d 1549 (11th Cir. 1988)

(promotion denial; terms and conditions).

Zaklama v. Mt. Sinai Medical Center o f Greater Miami, 842

F.2d 291 (11th Cir. 1988) (discharge).

Graham v. Jacksonville, 568 F. Supp. 1575 (M.D.Fla. 1983)

(discharge)

Nation v. Winn-Dixie Stores, Inc., 567 F. Supp. 997

(N.D.Ga. 1983) (promotion; demotion)

E-16

Schwartz v. State o f Florida, 494 F. Supp. 574 (N.D.Fla.

1980) (hiring)

Johnson v. City o f Albany, Georgia, 413 F Supp. 782

(N.D.Ga. 1983) (hiring; promotion)

D.C. CIRCUIT

Frazier v. Consolidated Edison Corp., 851 F.2d 1447 (D.C.

Cir. 1988) (discharge).

Barber v. American Security Bank, 841 F.2d 1159 (D.C. Cir.

1988) (discharge).

Underwood v. District o f Columbia Armory Bd., 816 F.2d

769 (D.C. Cir. 1987) (promotion denial).

Carter v. Duncan-Huggins, Ltd., 727 F.2d 1225 (D.C. Cir.

1984) (terms and conditions).

Metrocare v. Washington Area Metro Area Transit Authority,

679 F.2d 922 (D.C. Cir. 1982) (discharge; failure to

promote).

Harris v. Group Health Association, Inc., 662 F.2d 869

(D.C.Cir. 1981) (discharge)

Weahkee v. Perry, 587 F.2d 1256, (D.C.Cir. 1978)

(discharge; promotion)

Payne v. Blue Bell, 550 F. Supp. 1324 (M.D.N.C. 1982)

(discharge).

Gray v. Greyhound Lines, East, 545 F.2d 169 (D.C.Cir.

1981) (terms and conditions; hiring)

E-17

Pope v. City o f Hickory, North Carolina, 541 F. Supp. 872

(W.D.N.C. 1981), aff’d 679 F.2d 20 (4th Cir. 1982)

(discharge; terms and conditions).

Cormier v. P.P.G. Industries, 519 F. Supp. 211 (W.D. La.

1981) aff’d, 702 F.2d 567 (5th Cir. 1982) (hiring;

promotion denial).

Adams v. Gaudet, 515 F. Supp. 1086 (W.D.La. 1981)

(hiring; promotion denial).

Fisher v. Dillard Univ., 499 F. Supp. 525 (E.D. La. 1980)

(discharge; terms and conditions).

Reynolds v. Sheet Metal Workers Local 102, 498 F.Supp.

952 (D.D.C. 1980), aff’d. 702 F2d. 221 (D.C.Cir. 1981)

(hiring; training)

Crawford v. Railway Express, Inc., 485 F. Supp. 914 (W.D.

La. 1980) (retaliation).

Johnson v. Olin Corp., 484 F. Supp. 577 (S.D. Tex. 1980)

(discharge)

Robertson v. Maryland State Department, 481 F. Supp. 108

(D.Md. 1978) (termination; failure to rehire)

Liotta v. National Forge Co., 473 F. Supp. 1139 (W.D. Pa.

1979) , aff’d in part, rev’d in part, 629 F.2d 903 (3rd Cir.

1980) (discharge; retaliation).

Walker v. Robbins Hose Co., 465 F. Supp. 1023 (D.Del.,

1979) (hiring).

Queen v. Dresser Industries, Inc., 456 F. Supp. 257 (D.Md.

1978) aff’d 609 F.2d 509 (4th Cir. 1979) (terms and

conditions).

E-18

Neely v. City o f Grenada, 438 F. Supp. 390 (N.D. Miss.

1977) (hiring; promotion denial).

Crocker v. Boeing Co., 437 F. Supp. 1138 (E.D. Pa. 1977),

aff’d, 662 F.2d 975 (3rd Cir. 1981) (hiring; lay-offs;

promotion denial; terms and conditions; harassment)

Winston v. Smithsonian Science Information Exchange, Inc.,

437 F.Supp. 456 (D.D.C. 1977), aff’d, 595 F.2d 888

(D.C.Cir. 1979) (discharge; terms and conditions)

Jaw a v. Fayettevill State Univ., 426 F. Supp. 218 (E.D.N.C.

1976) (discharge; terms and conditions; promotion denial;

retaliation).

Johnson v. Shreveport Garment Co., 422 F. Supp. 526

(W.D.La. 1976), aff’d, 577 F.2d 1132 (5th Cir. 1978)

(terms and conditions; promotion denial).

Morris v. Board o f Education, 401 F. Supp. 188 (D.DeL,

1975) (discharge; failure to rehire).

APPENDIX F

Legislative History References to

§ 101 as Restoring Pre-Patterson

Interpretation of § 1981

M E M B E R O R REFERENCE TO § 101

OTHER SOURCE OF THE CRA AS

W/ PAGE CITE RESTORATIVE

SENATE-FEBRUARY 7. 1990

Kennedy

(S1018)

"The Civil Rights Act of 1990 is

intended to overturn these Supreme

Court decisions and restore and

strengthen these basic laws. The

Patterson decision, interpreting the

1866 civil rights law . . . nullified the

only Federal antidiscrimination law

applicable to the 11 million workers

in . . . firms with fewer than 15

employees. Already the damage is

unmistakable . . . and [the decision]

should be overruled by Congress."

Jeffords

(S1021)

"The Civil Rights Act of 1990 was

drafted with the specific intention of

overruling dome of these decisions,

as well as to restore and strengthen

our civil rights laws. . . First. In

Patterson versus McLean Credit

Union, the Court reached the

astounding conclusion that [§ 1981]

pertained only to the formation of

F-2

MEMBER OR

OTHER SOURCE

W/ PAGE CITE

Hatfield

(S1023)

Simon

(S1024)

REFERENCE TO § 101

OF THE CRA AS

RESTORATIVE