Draft Plaintiffs' Memorandum Opposing Motion for Summary Judgment

Working File

July 25, 1991

18 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Draft Plaintiffs' Memorandum Opposing Motion for Summary Judgment, 1991. 22e79ac4-a146-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/ddf7b9f4-477e-419a-8b33-9e18a1e8eeae/draft-plaintiffs-memorandum-opposing-motion-for-summary-judgment. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

AT

TS

RN

EY

S

AT

L

AW

i

[=a

~

= 4}

bot

[on

=

“ul

=

= %

-

0

&

)

a

~

I

iD

>

=

i

ET

*

H

A

R

T

Z

O

R

D

,

C

T

O

G

1

0

5

w=

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

A

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P.

C.

=

IL

LE

"T

ST

R

3

0

5

YI AI ded - = [gE =—yewy=—g py

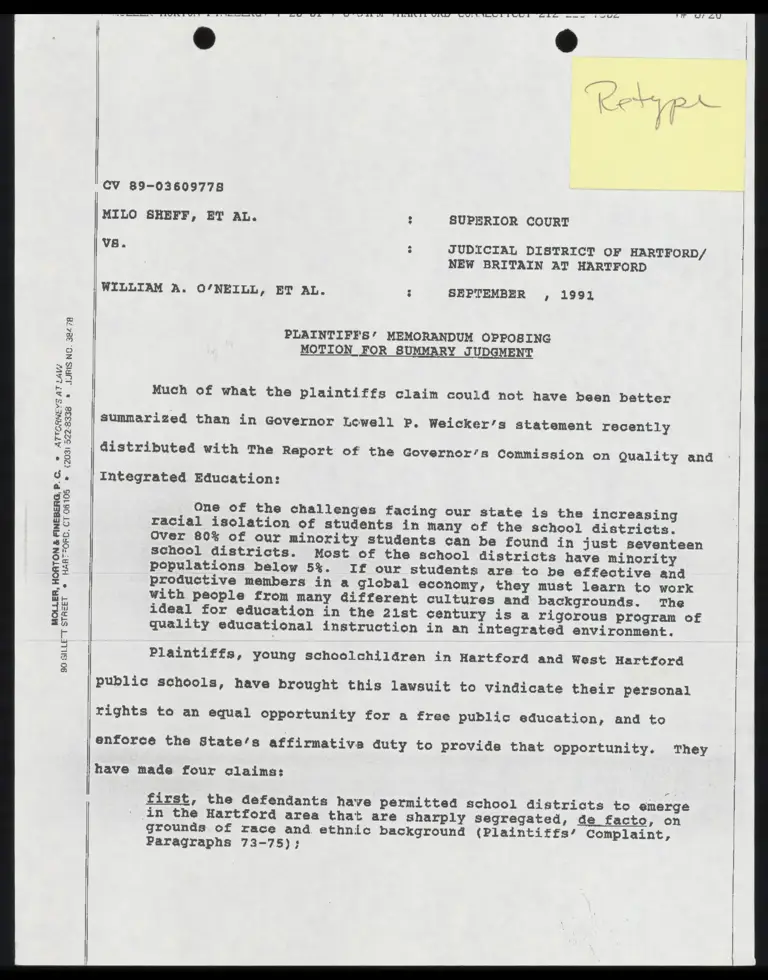

CV 89-03609778

MILO SHEFF, ET AL. SUPERIOR COURT

vse. JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF HARTFORD/

NEW BRITAIN AT HARTFORD

WILLIAM A. O/NEILL, ET AL. SEPTEMBER , 1991

PLAINTIFFS’ MEMORANDUM OPPOBING

MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

Much of what the plaintiffs claim could not have been better

summarized than in Governor Lewell P. Weicker’s statement recently

distributed with The Raport of the Governor’s Commission on Quality and

Integrated Education:

One of the challenges facing our state is the increasing racial isolation of students in many of the school districts. Over 80% of our minority students can be found in just seventeen School districts. Most of the school districts have minority populations below 5%. If our students are te be effective and productive members in a global economy, they must learn to work with people from many different cultures and backgrounds. The ideal for education in the 21st century is a rigorous program of quality educational instruction in an integrated environment.

Plaintiffs, young schoolchildren in Hartford and West Hartford

public schools, have brought this lawsuit to vindicate their personal

rights te an equal opportunity for a free public education, and to

enforce the State’s affirmativa duty to provide that opportunity. They

have made four claims:

first, the defendants have permitted school districts to emerge

~ in the Hartford area that are sharply segregated, de facto, on grounds of race and ethnic background (Plaintiffs’/ Complaint,

Paragraphs 73-75):

\J 5 GE TN ES ST J ’ EW A 11 UNL UI YO Ul Pale and tried Ea IE PPR SS Sy SFE. 1] o Ya

| pl » |

second, although the defendants recognize that this racial and economic segregation has seriously adverse educational effects, denying equal educational opportunity, they have permitted it to continue (Plaintiffs complaint, Paragraphs 76-78); third, the segregation that has arisen by race, by ethnicity and by economic status places Hartford schoolchildren at a severe

educational disadvantage, denies them an education equal to that afforded to suburban schoolchildren, and fails to provide a

majority with even a "minimally adequate education" (Plaintiffs’ Complaint, Paragraphs 79-80); and

fourth, under Connecticut’s education statutes, the defendants are obliged to correct thease problems, and their failure to have done 80 violates the scloolchildren’s rights (Plaintiffs’

Complaint, Paragraphs 81-82).

T

i

a

E

Y

S

A

r

o

e

n

The remedy plaintiffs seek is a declaration by this Court that

jon}

P=

_—

0

™m

Oo

z

v3

on

) — fl

Ad

oo

"

Lor]

2

oN

[3]

ul

5

jr}

£y the present circumstances violate the Connecticut Constitution, and an

injunction enjoining the defendants from failing to provide equal

educational opportunity.

The defendants have moved for summary judgment. They claim (1)

the conditions are not the result of state action, (2) the state has

satisfied its affirmative obligation and (3) the controversy is not M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P

.

C

.

+

a

GI

LL

ET

T

S

T

R

E

E

T

=»

H

A

R

T

F

O

R

D

,

CT

C8

10

5

=

justiciable. To a large extent this motion is simply a more voluminous

rehash of what has already been heard.

~

SC

Issues (1) and (3) were previously raised in the defendants’

motion to strike, which this Court denied on May 18, 19%0. Issua (1),

which concerns the construction which should be given to the three

State constitutional provisions in question, Article First, §51 and 20,

: FTE NE Ti did. LIV YL ER OE FE TARE TR LTE ERE Bul hay TR EE BEER T INL JIN. / A ET WR TN Ta ’ 2/ ZU

| * »

and Article Eighth, §1, was discussed in detail at PP. 1ll=14 of this

Court’s memorandum of decision on the defendants’ motion to strike.

This Court indicated that a conclusive disposition of this issue prior

to trial would not be appropriate. Likewise, the issue of

justiciability was discussed in detail at PP- 5-11 of the Court’s

[44]

fs . decigion, with the same result. These rulings being the law of the

: case, "a judge should hesitate to change" the ruling unless there is

Ba "some new or overriding cirecumstance.n Carothers v. Capozziello, 215 A

+ Conn. 82, 107, 574 A.24 1268 (May 22, 1990). The defendant points to

i no new or overriding circumstance to justify reexamination of these

s. issues before trial, Indeed, in their J0~page brief, there is not one

I: case cited that has been decided since May la, 1990.

+ The test for summary judgment is a strict one. Practice Book

4 §384 provides that summary judgment "shall be rendered forthwith if the

g pleadings, affidavits and any other proof submitted show that there is

Cf: no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is

J

GI

LL

ET

T

ST

R:

entitled to judgment as a matter of law.w Lees v., Middlesex Ins. Co.,

Cc

br

219 Conn. 644, 650, A.24 (1991). The defendants must show

the absence of any genuine issue as tc all material facts, which

under applicable principles of substantive law, entitle him to

judgment as a matter of law. To satisfy his burden the movant

must make a showing that it is quite clear what the truth is, and

that excludes any real doubt as to the existence of a genuine

issue of material fact. ‘

Fogarty v. Rashaw, 193 Conn. 442, 445, 476 A.24 582 (1984) [emphasis

added]. Fogarty is particularly apt, because there a summary judgment

12

03

]

52

2-

83

38

=

JU

RI

S

NC

.

38

47

6

”~

Le

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P.

C.

*

A

4

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT

1

A

QD

CI

LL

ET

T

ST

HE

ET

+

H

A

R

T

F

O

R

D

,

CT

C6

14

5

was held improper without even considering the opposition papers,

because the papers filed by the moving party were insufficient as a

matter of law. That is this case.

Dafendants’ "Fact 1", set out at Pp. 6=9 of their brief, is that

they have not affirmatively assigned children to the Hartford public

schools based on their race or other improper factors. But so what?

As the defendants recognize (p. 7), this is a de facto, not a de jure,

segregation case, so the fact claimed by the defendants is not

material,

As this Court noted in its prior decision (Pp. 12), the defendants

are really resurrecting Justice Loiselle’s dissent in Horton v.

Meskill, 172 Conn. 615, 658, 376 A.2d 359 (1977) (Horton I), that all

the constitution requires is that education be free. But the

majority’s holding that public education is "a fundamental right," that

"pupils in the public schools are entitled to equal enjoyment of that

right," and that "any infringement of that right must be strictly

scrutinized;" 172 conn. at 645, 646, 649; has been cited as racently as

Savage v. Aronson, 214 Conn. 256, 286, 571 A.2d 696 (1990); and was

expressly reaffirmed by a unanimous court in Horton v. Meskill, 19s

Conn. 24, 35, 486 A.24 1099 (1985) (Horton III).

As in their motion to strike, the defendants once again strain to

isolate constitutional provision that, as Horton I and Hortepn III held,

must be read together. The State == under Article Eighth, 81,

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P.

C.

»

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT

(A

IA

IL

LE

TT

ST

RE

ET

«

H

A

R

T

F

C

A

D

,

C

T

O

E

1

0

6

=

12

03

)

52

2-

83

38

«

JU

RI

S

NO

.

53

84

78

9

0

3

J v J-00FM THARTFORD CONNEC =212 226 2 F720

read in conjunction with Article First, §51 and 20 == is "required to

assure to all students in Connecticut’s frees public elementary and

secondary schools ‘a substantially equal educational opportunity, s/n

Horton III, 195 Conn. at 35.

The defendants misunderstand the concept of state action as it

applies to this case. Whether or not state action or inaction has

created the problem is irrelevant. In Horton, there was no finding

that the state created the wicle variations in property tax revenues

available to the various towns. Yet the Supreme Court in Horton I had

no trouble in finding that the State bora the affirmative

responsibility, in providing a free public education, to mitigate those

private economic differences.

Even the case the defendant most heavily rely on, Savage v.

Aronson, sites "the burden imposed on the stats by our decision in

Horton to insure approximate equality in the public educational

opportunities offered to the children throughout the state; . , . .»

214 Conn. at 286-87 [emphasis added].

Savage was a housing case. The 30-page opinion primarily

concerns procedural issues, the proper construction of state housing

statutes, and due process of law (pp. 257-286). The Horton issue

appears at the very end and the Supreme Court disposes of it quickly on

the ground that Horton does not "guarantee that children are entitled

mA

BY - MO

to receive their education at any particular school or that the state

must provide housing accommodations for them and their families close to the schools they are presently attending." 214 Conn. at 287.

The plaintiffs are making no such claim in the present case.

Indeed it is the opponents of an integrated education who trumpet the

glories of the neighborhood school. gavage does nothing to advance the

defendants’ cause. What it does do is reaffirm the vitality of Horton.

1

=r

@

”

=

ro

ul

3

i

Even if Fact 1 is considered material that merely puts the burden

Y

S

A

T

(

A

W

1 on the plaintiffs to provide evidence to sustain that fact. That is

3 so because the purpose of a summary judgment motion is to determine

H Whether there exists an issue of fact, but not to try it if it does.

g Epencer v. Good Earth Restaurant Corporation, 164 Conn. 194, 197, 319

£ A.2d 403 (1972). Bee Conference Center Ltd. Vv. TRC, 189 Conn. 212,

5 217, 228, 455 A.2d 857 (1983) (issue "necessarily fact bound require a

g full trial and preclude summary judgment"); Batick v. Seymour, 186

3 Conn. 632, 645-4s, 443 A.2d 471 (1982) ("genuine issue over the

5 defendant’s intentions"). The following show that there is no basis

a

for summary judgment. [MARTH2Z INSERT FACTUAL INFORMATION ON FACT 1]

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P.

C.

*

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT

L

A

W

30

G'

LL

ET

Y

S

H

E

E

T

=

H

A

R

T

F

C

R

D

.

C

T

Q

E

I

0

5

»

@

f=.

~~)

od

oy

JU

RI

S

NG

.

12

03

1

5

2

2

-

8

3

3

6

»

I Ad ry L H i Y "MOLLER HORION © INEBENG: (1-29-91 » o-0/EM HAKITORD CONNCCIICUISZ212 226 (092 TF 9/2

Defendants’ “Fact 2," set out at pp. 9-13, is that the plaintiffs

have not stated what the defendants should have done in the past to

address the problem. Once again, so what? The defendants do not sean

to understand that they, not the plaintiffs, have a duty under the

constitution. The plaintiffs are not complaining about what happened

in the past or why; they are complaining about a condition that exists

now. They are saying that condition violates the constitution ana the

defendants have a duty to change the condition. There certainly is no

suggestion in Horton I or III that Barnaby Horton had a duty to prove

what the defendants could have done to solve tha school finance problem

before he brought his lawsuit.

What the defendants may really be implying is that the plaintiffs

have no plan to solve the problem in the future. But that has to do

with the remedy, not liability. The plaintiffs will be prepared to

discuss the remedy when the Court wishes to do 20, but a motion fer

summary judgment is surely not the appropriate time,

In any event, the plaintiffs submit the following evidences to

show that, even if "Fact 2» is material, summary judgment would be

improper. Spencer v. Good Earth Restaurant Corporation, supra.

[MARTHA « INBERT FACTUAL INFORMATION ON FACT 2]

SENT BY:MOLLER HORTON FINEBERG; 7-29-91 ; 3:58PM HARTFORD CONNECTICUT-212 226 7592 #10720

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

FI

NE

BE

HA

G,

P.

C.

¢

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT

LA

W

47

9

<U

II

S

NO

,

38

12

03

1

52

2-

83

38

»

T

O

B

2

0

5

=

~ r=

EE

T

IL

LE

™T

ST

A

3

0

5

*

H

A

R

T

F

O

3

D

,

Defendants’ “Fact 3" set out at pp. 14-43, enumerates a

voluminous list of affirmative acts, supposadly taken by the state to

address its duty to provide all students an equal opportunity for a

free public education. Nothing is stated that remotely justifies

summary judgment.

As in Facts 1 and 2, sone of the statements in Fact 3 are

immaterial. For example, what difference does it make how much monay

is pouring into Hartford? This is a school desegregation, not a school

finance, case. Even if some of the statements are material on aome

issues, they fail to address all the material issues. For example, the

defendants’ evidence is silent on the issue of causation, for even if

every factual statement made by tha defendants im true, there remains a

| factual question about what result have been or will be accomplished.

In Lomangino v. Laghance Farms, Inc., 17 Conn. App. 436, 553 A.2d

197 (1989), a summary judgment for the defendant was reversed because

the defendant did not eliminate any factual question concerning the

issue of proximate cause. Quecting four Supreme Court cases, the

Appellate Court noted that “proximate cause is ordinarily a question of

fact." 17 Conn. App. at 440.

*

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT

L

A

W

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P.

C.

B

<r

44]

™

©

=

52]

[=

boa

=

®

44}

&

©

ol

N

i

™

oo

ol

ET

«

H

A

R

T

F

O

R

D

,

C

T

O

E

1

0

5

=

SI

LL

ET

T

£T

RE

30

35

In light of the admitted fact that the Hartford public schools

are about 90% ainovity and that the surrounding public schools, except

for Bloomfield and Windsor, average about 90% nen=minority (see

defendants’ answer to para, 33 of the Complaint), it is difficult to

sae how the defendants’ 29-pa¢e list of facts can possibly prove

anything other than the plaintiffs’ point that the defendants have made

a wholly inadequate attempt to address a monumental violation of

constitutional rights. The list on its face provides no basis to enter

a summary judgment.

The plaintiffs submit herewith the following evidence showing

there is no conceivable basis for summary judgment [MARTHA: INSERT

FACTUAL INFORMATION ON FACT 3]

W

e

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P

.

C

.

*

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT!

om

re

«+

23)

[x]

u

>

ui

vm

pos |

wy

-

[13

(3)

re)

CY

©

ol

13)

5

[A]

.

3)

Le] -

©

oO

a

(1'ny

Q

i

-

[1

=[

T

»

[vw

=

-

73]

13 .

—

wi

-

ad

oO

€)

&

? 7 Ll

The general philosophy of the defendants’ brief seems to be not

50 much the lengthy cataleg of state programs. Rather it seems to be a

philosophy of non=-justiciability. What the defendants are really

saying is that school desegregation is a difficult societal problem and

the courts should stay out of it.

The problem with this philosophy is the lack of judicial

authority to support it. Rather the courts have a special power and

obligation to see that all children in the state receive an equal

opportunity to a free public education.

This Court has already discussed the subject of justiciability in

the 1990 ruling. At page 9, this Court stated:

The fact that the legislative branch is given plenary

authority over a particular governmental function does not

insulate it from judicial review te determine whether it has

chose "a constitutionally permissible means of implementing that

power." Immigration & Naturalization Service v. Chadha, 462 U.S.

919, 940-41 (1983). "[T]he legality of claims and conduct is a

traditional subject for judicial determination", and such

adjudication may not be avoided on the ground of

nonjusticiability unless the particular function has been

assigned "wholly and indivisibly" to another department of

government. Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. at 245-46 (Douglas, J.

concurring).

In the light of Horton I and III, the defendants cannot possibly

claim that guaranteeing an equal opportunity te a free public education

"has been assigned ‘wholly and indivisibly to" the Legislature.

wl =

i 0

38

«

JU

RI

S

NC

.

38

47

-

31

05

=

20

3)

52

2-

33

TS

C

ET

®

HA

RT

FO

RL

C,

E

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P.

C.

+

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT

L

A

W

3

GI

LL

ET

T

ST

R

-

Article Eighth, §1, states that "the general assembly should

implement this principle [free public schools] by appropriate

legislation." The word "appropriate" signifies that legislative

discretion must be properly exercised; the qualifier plainly

contemplates judicial oversight of the appropriateness of legislative

action. This reading is fully supported, once again, by Horton I.

There, the Connecticut Supreme Court employs this precise

constitutional phrase as a basis for striking down Connecticut’s former

system of school finance:

[T]he . . . legislation enacted by the General Assembly to

discharge the state’s constitutional duty to educate its children

« » + Without regards to the disparity in the financial ability

of the towns to finance an educational program and with no

significant equalizing state support, is not appropriate

legislation’ (article eighth, §1) to implement the requirement

that the state provide a substantially equal educational

opportunity to its vouth in its free public elementary and

secondary schools,

172 Conn. at 649 (emphasis added). Under no coherent theory of

justiciabllity could the courts of Connecticut have jurisdiction to

raview the General Assembly’s judgments on school finance, yet ba

disempowered as_a matter of jurisdiction from reviewing the

legislature’s Article Eighth, §1, duties on another ground. Either 51

vests exclusive, unreviewable authority in the legislature, or it does

not. As Horton I, demonstrates, the Supreme court has already

authoritatively answered that question.

“]ll-

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT

L

A

W

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P.

C.

=

90

GI

LL

E'

T

ST

RE

ET

&

H

A

R

T

F

C

R

D

,

C

T

O

E

I

0

E

»

Ww

fe

wr

uw

az]

)

“

E) -

w

o

om

«

o~

[]

0)

©

oc

Ny

In one respect the present case is a stronger one for

justiciability than Horton. while Horton relies on the ecenstruction of

Article First, §§1, and 20, and Article Eighth, §1, the present case,

in addition to the same reliance, relies independently on the history

and language of Article First, §20.

The Supreme court recently stated:

We have also, however, determined in mome instances that the

protections afforded to the citizens of this state by our own

constitution go beyond those provided by the federal

constitution, as that document has been interpreted by the United

States Supreme Court.

gtate v, Marsala, 216 Conn. 150, 160, 579 A.2d 58 (1990). Accord:

Horton I, at 641-42; state v. Barton, 219 Conn. 529, 546, A.24d

(1991). Indeed, in talking about “the full panoply of rights" that

Connecticut citizens "have come to expect as their due," Barton cites

Horton I.

Article First, §20, is even stronger than the federal equal

protection clause, which has generally been the sole constitutional

of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). While the Fourteenth Amendment was

passed right after the Civil War, it says nothing expressly about

segregation. Article First, §20, on the other hand, states that "no

person shall be deniad the equal protection of the law nor be subjected

to segregation or discrimination in the exercise of his civil or

political rights because of . . . Pace... LY

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

.

P.

C.

&

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT

L

A

Y

JO

GI

LL

ET

T

ST

RE

ET

=

H

A

R

T

F

O

3

D

.

C

T

O

B

I

0

E

=

w

r=

=r

[<7]

I]

oO

=

w

tr

=

=

.

«Q

Ia)

"

0

oN

ty

iy

®

Q

Ey

"It cannot be presumed that any clause in the Constitution is

intended to be without effect: . . . . Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch

138, 174 (1803). "Unless there is some clear reason for not doing so,

effect must be given to every part of and each word in the

constitution." State v. Lamme, 216 Conn, 172, 177, 579 A.2d 484

(1990).

In Lamte, the Supreme Court examined the text and history of

Article Firat, §8, to determine if more rights should be given to

Connecticut citizens than under the federal constitution. If we

analyze the text of Article First, §20 carefully, we see that

segregation and discrimination are treated as in addition to equal

protection of the law, and that segregation is treated as in addition

to discrimination.

The plaintiffs claim that the right to attend integrated public

schools is one of their civil rights. As Brown itself stated 35 years

ago, separate schools are inherently unequal. 347 U,8. at 495.

Article First, 320, was added to the Connecticut Constitution in 1965.

At that time the framers knew about Brown and knew about the struggles

over desegregation after 1954. Thus they not only prohibited

discrimination, but they also prohibited segregation.

-]3=

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P.

C.

*

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT

L

A

W

SC

GI

LL

ET

T

ST

RE

ET

+

HA

R

FO

RL

C,

CT

D5

12

oh

~

xt

*

oO

>

wl

ac

a

—

#

=

[32]

ar

I |

™

[V2]

51

hi

ve

13

0

The term “segregation in §20 was specifically debated at the

1965 Constitutional Convention. Not only was it debated, but the word

was actually deleted in Committee, and reinserted on the floor of the

Convention after debate on its reinclusion See "Journal of the

Constitutional Convention" at 174. Bee also pp. 691-692 ("We have

spent a lot of time on this particular provision . . .M).

The debate demonstrates that the purpose of including the term

"segregation" was Yso that it [§20] would not be interpreted as an

exclusion or limit rights" (p. 691) and to provide as broad and as

expansive rights to equal protection as possible. See remarks of Mrs.

Woodhouse (p. 691) (Constitution should "unequivocally oppose the

philosophy and the practice of segregationn), Mr. Eddy (p. 691), Mr.

Kennally (p. 692) (equal protection clause "all inclusive" and "the very

strongest human rights principle that this convention can put forth to

the people of Connecticut"), and Mrs. Griswold (p. 693). In his

closing remarks, former Chief Justice Baldwin described §20 as

nsomething entirely new in Connecticut" (p. 1192). The debate also

eXpressly acknowledges that the new section, including the prohibition

against "sagregation", would apply to “rights of freedom in education."

(Page 694).

*

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT

L

A

V

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P.

C.

IL

LE

TT

ST

RE

ET

=

H

A

R

T

F

O

R

D

,

C

T

05

°0

5

»

U

R

I

S

YO

.

28

47

38

12

03

1

52

2-

83

38

=

ID

C

wd 0 ; er ed ld Nd Cd ed ed WJ

The term “segregation! was commonly used in 1965, as it is today,

to describe the actual separation of racial groups, without regard to

cause, Thus, in the influential Coleman Report in 1966, segregation is

described as a demographic phenomenon:

The great majority of American children attend schools that are

largely segregated -- that is, where almost all of their fellow

students are of the same racial background as they are.

James Coleman et al, Eguality of Educational Opportunity at 3.

Furthermore, at the time the Connecticut Constitution was

adopted, the U.8. 8upreme Court had not yet incorporated an intent

requirement into Brown and the lower courts were divided as to whether

municipalities could be held liable for purely de facto school

segregation. Against this background, if the framers had sought to

limit the meaning of the term segregation to "intentional" or "de jure"

actions, they certainly would have done so explicitly. Section 20 is

an appropriate and independent basis for the plaintiffs’ claims.

The only case the defendants seriously rely on for their

justiciability argument is Pellegrino v. O’Neill, 193 Conn. 670, 480

A.2d 476 (1984). As this Court noted, the defendants’ reliance is only

a plurality opinion, with a strong dissent by the current chief

justice.

=

Pellegrino involves a claim under Article First, §10, that civil

trials were being unconstitutionally delayed by the failure of the

Legislature to provide sufficient judges to handle the backlog of

cases, The plurality in Pellegrino were understandably reluctant to

maugment their numbers by writs of mandamus," 193 Conn. at 678, because

to do so, they reasoned, would be "to enhance [their] own

constitutional authority by trespassing upon an area clearly reserved

as the perogative of a coordirate branch of government." Id. No

similar danger of institutional self-aggrandizement exists in this

case. Furthermore, Horton I was reaffirmed after Pellegrino in Horton

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

EA

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P.

C.

*

A

T

T

O

A

N

T

Y

S

AT

L

A

Y

GC

G

I

L

L

E

T

™

S

T

R

E

E

T

=

H

A

R

T

F

O

R

D

,

ZT

5

1

0

%

«

[

2

0

3

5

2

2

-

8

3

2

3

®

J

U

R

!

S

A

D

38

4

III, which does not even mention Pelleqrine. Pellegrino has nothing to

do with the plaintiffs’ right to an equal opportunity for a free public

G ~

education.

—]1&=

*

A

T

T

O

R

N

E

Y

S

AT

L

A

W

MO

LL

ER

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

FI

NE

BE

RG

,

P.

C.

<0

[=

«J

[=]

oN

3

=

2.

1 od

= =]

=

Ww

oy

[42]

w

od

o™~

©

oa

&

[

wy

S

A

0

a

fr

oO

a

[+= oO

iL

j=

in

=1

oT

[

f=

FIN]

w

©

[.

&

-

Boe

Wd

-—

wd

a

o

on

Chief Justice Peters, the author of Horton III in 1985, had the

following to say one year later:

Third, courts must respond to changes in our moral

environment, to greater sensitivity to the rights of minorities

and women and children and the aged and the handicapped and

students and teachers -- the list, thank goodness, keeps growing.

«+ +» « That litigation increasingly turns to state law, and state

constitutions, as federal courts retreat from the commitments of

the Warren Supreme Court.

« « « Despite their imperfect access to an unclouded crystal

ball, courts are invelved in devising remedies for discriminatory

inequality in school systems, for inadequate treatment in mental

hospitals, for unsafe housing for the dispossessed, and for

unsatisfactory custodial arrangements for children caught up in

family instability.

Not all litigation, howaver, permits deference or allows

invocation of the passive virtues. In the face of uncertainty,

courts must resolve some questions, regrettably, because courts

are not the beast, but the only available decision-makers. . . ,

When litigants have exhausted other channels, however, when the

political process is unresponsive, and when other situations in

society have, in effect, thrown in the sponge, it is courts that

must respond to our society’s self-fulfilling prophecy that for

avery problem, there ought to be a law.

Patera, "Coping with Uncertainty in the Law," 19 Conn.L.Rev. 1, 3, 6

(1986). Bee also Peters, "Common Law Antecedents of Constitutional Law

in Connecticut," 53 Albany L.Rev. 259 (1989).

M

O

L

L

E

R

,

H

O

R

T

O

N

&

F

I

N

E

B

E

R

G

,

P

.

C

.

=

A

T

T

O

S

N

E

Y

S

AT

L

a

w

12

03

:

2

2

-

8

3

3

8

+

J

U

R

E

NO

38

47

8

I.

_.

£T

T

ST

RE

:

0

5

T

+

H

A

R

T

F

O

R

D

,

CT

03

10

5

e

We are told that "the Court stands at the crossroads in this

case," (Defendants’/ br. p. 5). What the defendants see is just a

mirage. The crossroads still lie ahead - at the end of a trial on the

merits. The motion for summary judgment should be denied.

PLAINTIYFS, MILO SHEFF, ET AL.

BY

-18~