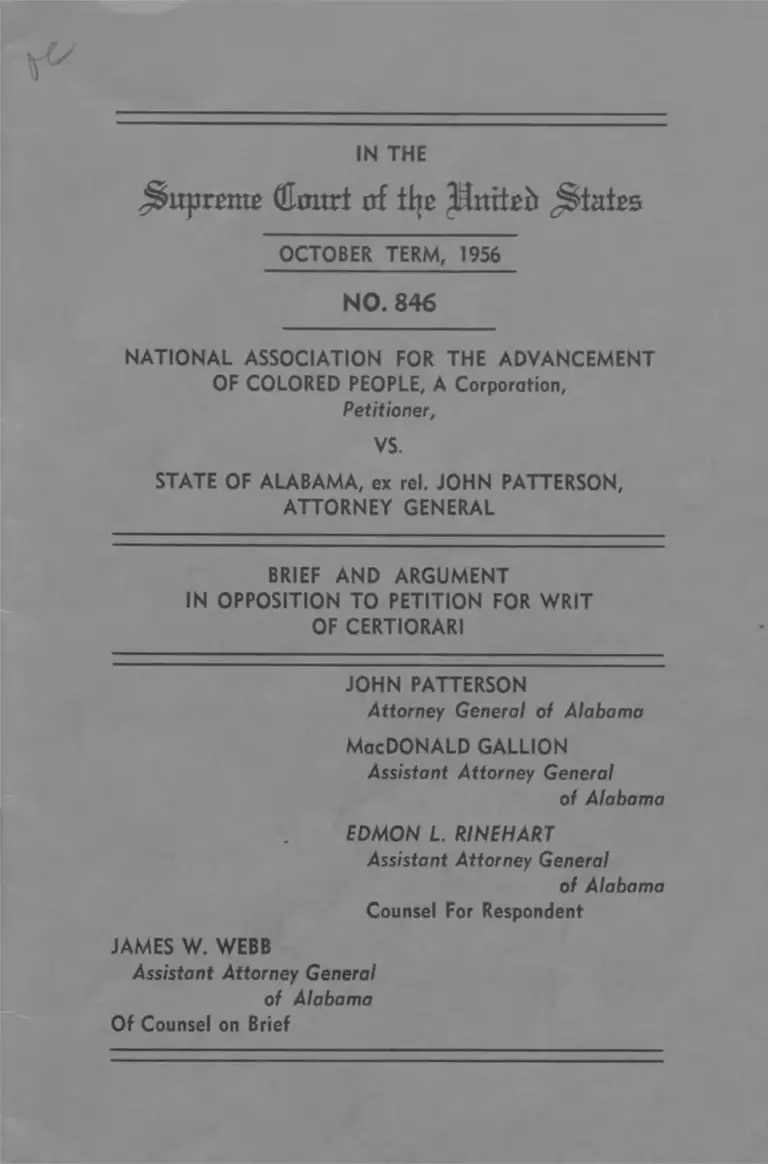

NAACP v. Alabama Brief and Argument in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

May 18, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Alabama Brief and Argument in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1957. 4d261028-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/de1054e8-7fd7-4437-b255-7548652a227e/naacp-v-alabama-brief-and-argument-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

V

IN THE

jiupmne (Eourt of ti|o Mnxttb j§tates

OCTOBER TERM, 1956

NO. 846

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT

OF COLORED PEOPLE, A Corporation,

Petitioner,

VS.

STATE OF ALABAMA, ex rel. JOHN PATTERSON,

ATTORNEY GENERAL

BRIEF AND ARGUMENT

IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR WRIT

OF CERTIORARI

JOHN PATTERSON

Attorney General of Alabama

MacDONALD GALLION

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

EDMON L RINEHART

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

Counsel For Respondent

JAMES W. WEBB

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

Of Counsel on Brief

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinion Below

Jurisdiction

Questions Presented

Statement of the Case

Argument ..............

Page

1

1

1

2

I. The Decision Below correctly decided all

Questions properly presented in the

State Courts ................................................. 9

II. No Constitutional Rights of Petitioner

were abridged by the State in the

Proceedings in the State Courts 14

Conclusion ....................................................................21

11

TABLE OF CASES CITED

Page

Adamson v. California, 332 U. S. 46 11

Asbury Hospital v. Cass County, 326 U. S. 207 12

Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U. S. 495 ................... 18

Ex parte Dickens, 162 Ala. 272, 50 So. 2 1 8 ........... 9

Ex parte King, 263 Ala. 487, 83 So. 2d 241 ........... 10

Ex parte Morris, 252 Ala. 551, 42 So. 2d 17 ......... 10

Ex parte National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People, 91 So. 2d 214,

91 So. 2d 220, 91 So. 2d 221 ...............................1, 7

Hague v. Congress of Industrial Organizations,

307 U. S. 514 ....................................................... 17

Hale v. Henkel, 201 U. S. 4 3 ................................... 16

Herndon v. Georgia, 295 U. S. 441, 442 13

Joint Anti-fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath,

341 U. S. 123, at 183 & 184 ............................... 19

International Ladies Garment Workers Union,

A. F. L. v. Seamprufe, Inc., 121 Fed. Supp. 175 17

Local 309, United Furniture Workers of America,

CIO v. Gates, 75 Fed. Supp. 620 17

National Safe Deposit Company v. Stead,

232 U. S. 58 11

Ill

Oklahoma Press Publishing Co. v. Walling,

327 U. S. 186 12

Pennekamp & the Miami Herald Publishing

Co. v. Florida, 328 U. S. 331 18

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 18

Powe v. United States, 109 Fed. 2d 147,

cert, denied 309 U. S. 679 17

Profile Cotton Mills v. Calhoun Water Co.,

189 Ala. 181, 66 So. 50 16

Rogers v. United States, 340 U. S. 367 ................. 16

State ex rel. Griffith v. Knights of the Klu

Klux Klan, 117 Kan. 564, 232 P. 254,

cert, denied 273 U. S. 664 12

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 ........................... 18

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542 ........... 17

United States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 41 18

United States v. United Mine Workers of

America, 330 U. S. 258 ....................................... 10

United States v. White, 322 U. S. 694 ................... 16

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375 ....................... 13

Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25, 27 ....................... 11

IV

STATUTES AND OTHER AUTHORITIES CITED

Title 7, Section 1061, Code of Alabama 1940 16

Title 10, Sections 192, 193 and 194,

Code of Alabama 1950 3

Constitution of Alabama 1901, Section 232 3

United States Code:

Title 28, Section 1257(3) ................................... 1

IN THE

Supreme Court of the litutn> States

OCTOBER TERM, 1956

BRIEF AND ARGUMENT

IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR WRIT

OF CERTIORARI

BRIEF AND ARGUMENT FOR RESPONDENT

OPINION OF THE COURT BELOW

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama

is reported in 91 So. 2d, at page 214.

JURISDICTION

The petitioner has applied for a writ of certiorari

from the Supreme Court of the United States to re

view the judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama,

rendered December 6, 1957, under the provisions of

Title 28, Section 1257(3), United States Code, Judici

ary and Judicial Procedure. (See petitioner’s brief,

page 2.)

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I.

Is any constitutional question presented by the

decision of the Supreme Court of Alabama, in view

of the issues presented to that Court by the petition-

2

er, its failure to follow prescribed Alabama proce

dures, and the long standing decisions of the Supreme

Court of the United States upon the applicability of

the First, Fourth, Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments,

to corporations?

II.

Has the petitioner, a membership corporation,

having neglected to avail itself of the proper remedy

to review the trial court’s order to produce, having

chosen to stand in contempt of that trial court in as

serting the alleged constitutional rights of its mem

bers, and having obtained review of the trial court’s

contempt order, but not reversal thereof, been denied

due process of law because its own contumacy has

precluded its further proceeding on the merits of the

main case, pending its purging itself of contempt?

III.

Has the petitioner, a membership corporation,

the constitutional right to refuse to produce records of

its membership in Alabama, relevant to issues in a

judicial proceeding to which it is a party, on the mere

speculation that these members may be exposed to

economic and social sanctions by private citizens of

Alabama because of their membership?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Upon June 1, 1956, the State of Alabama, on the

relationship of John Patterson, its Attorney General,

filed a bill in equity, against the petitioner, National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People,

a Corporation, in the Fifteenth Judicial Circuit, Mont

3

gomery County, Alabama. The gravamen of the bill

was that the corporation conducted extensive activi

ties in pursuance of its corporate purpose in Alabama

without having filed with the Secretary of State a

certified copy of its articles of incorporation and an

instrument in writing, under the seal of the corpor

ation, designating a place of business and an author

ized agent residing in Alabama, as required by Title

10, Sections 192, 193 and 194, Code of Alabama 1940,

thus doing business in Alabama in violation of Sec

tion 232 of the Constitution of Alabama 1901, and

Title 10, Section 194, Code of Alabama 1940.

The bill of complaint alleged irreparable harm

to the property and civil rights of the residents and

citizens of Alabama, for which criminal prosecutions

and civil actions at law afforded no adequate relief.

A temporary injunction and restraining order was re

quested, preventing the respondent below and its

agents from further conducting its business within

Alabama, from maintaining any offices and organiz

ing further chapters within the State. A permanent

injunction, in accordance with the prayer for tem

porary injunction, was also prayed for. Finally, an or

der of ouster expelling the corporation from organ

izing or controlling any chapters of the National As

sociation for the Advancement of Colored People in

Alabama, and exercising any of its corporate func

tions within the State, was requested.

On June 1, 1956, the Circuit Court of Montgom

ery County, Alabama, entered a decree for a tem

porary restraining order and injunction, as prayed for

and further enjoined until further order of the court

petitioner from filing any application, paper or docu

ment for the purpose of qualifying to do business in

4

Alabama. Service was had upon respondent corpor

ation, at its offices in Birmingham, Alabama.

On July 2, 1956, petitioner filed a motion to dis

solve the temporary restraining order and demurrers

to the bill of complaint which were set for hearing on

July 17. On July 5th the State filed a motion to re

quire petitioner to produce certain records, letters and

papers alleging that the examination of the papers

was essential to its preparation for trial.

The State’s motion was set for hearing on July

9, 1956. At the hearing, at which petitioner raised

generally but not explicitly both State and Federal

constitutional objections, the court issued an order

requiring production of the following items requested

in the State’s motion:

“1. Copies of all charters of branches or

chapters of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People in the State

of Alabama.

2. All lists, documents, books and papers

showing the names, addresses and dues paid

of all present members in the State of Ala

bama of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, Inc.

4. All lists, documents, books and papers

showing the names, addresses and official

position in respondent corporation of all per

sons in the State of Alabama authorized to

solicit memberships in and contributions to

the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People, Inc.

5

5. All files, letters, copies of letters, tele

grams and other correspondence, dated or oc

curring within the last twelve months next

preceding the date of filing the petition for

injunction, pertaining to or between the Na

tional Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, Inc., and persons, corpor

ations, associations, groups, chapters and

partnerships within the State of Alabama.

•

6. All deeds, bills of sale and any written

evidence of ownership of real or personal

property by the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, Inc., in the

State of Alabama.

7. All cancelled checks, bank statements,

books, payrolls, and copies of leases and

agreements, dated or occurring within the

last twelve months next preceding the date

of filing the petition for injunction, pertain

ing to transactions between the National As

sociation for the Advancement of Colored

People, Inc., and persons, chapters, groups,

associations, corporations and partnerships

in the State of Alabama.

8. All papers, books, letters, copies of let

ters, documents, agreements, correspondence

and other memoranda pertaining to or be

tween the National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People, Inc., and Au-

therine Lucy, Autherine Lucy Foster, and

Polly Myers Hudson.

11. All lists, books and papers showing

6

the names and addresses of all officers,

agents, servants and employees in the State

of Alabama of the National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People, Inc.

14. All papers, books, letters, copies of let

ters, files, documents, agreements, corres

pondence and other memoranda pertaining to

or between the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored people, Inc., and

Aurelia S. Browder, Susie McDonald, Clau

dette Colvin, Q. P. Colvin, Mary Louise

Smith and Frank Smith, or their attorneys,

Fred D. Gray and Charles D. Langford.”

The court then extended the time to produce un

til July 24th, and simultaneously postponed the hear

ing on petitioner’s demurrers and motion to dissolve

the temporary injunction to July 25.

On July 23, petitioner filed an answer on the

merits. In addition, petitioner averred that it had pro

cured the necessary forms for the registration of a

foreign corporation supplied by the office of the Sec

retary of State of the State of Alabama, and filled

them in as required. Petitioner attached them to its

answer and offered to file same if the court would

dissolve the order barring petitioner from registering.

At the same time petitioner filed a motion to set

aside the order to produce which motion was set down

for hearing on July 25th.

On July 25, 1956, the court heard oral testimony,

and argument of counsel and overruled the motion to

set aside and ordered the production of the items

stated in its previous order. Petitioner refused to com

ply with the court’s order, upon which the court ad

7

judged petitioner in contempt, assessed a fine of $10,-

000.00 against it as punishment for the contempt with

the further provision that unless the petitioner com

plied with the order to produce within five days the

fine would be increased to $100,000.00. The petition

er’s motion to dissolve the temporary injunction was

not heard in view of its contempt in refusing to obey

the order to produce.

Upon July 30, 1956, petitioner filed, with the trial

court, a motion to set aside or stay execution of the

contempt decree pending review by the Supreme Court

of Alabama. Petitioner also tendered miscellaneous

documents which it alleged to be substantial compli

ance. At all times the corporation refused to produce

the names and addresses of its members. This mo

tion was denied and petitioner then filed a motion in

the Supreme Court of Alabama, requesting stay of

execution of the judgment below pending review by

the appellate court. This motion or application was

also denied.1 On the same day the Circuit Court en

tered an order adjudging petitioner in further con

tempt, increasing the fine to $100,000.00, in view of

its continued refusal to obey the order to produce.

On August 8, petitioner filed a purported peti

tion for writ of certiorari in the Supreme Court of Ala

bama. After oral argument on August 13, 1956, the

Supreme Court of Alabama, denied the writ on the

grounds of its insufficiency.2

1. 91 So. 2d 220.

2. 91 So. 2d 221.

8

Thereafter on August 20, 1956, petitioner filed a

second petition for writ of certiorari.3 Upon December

6, 1956, the Supreme Court of Alabama, denied the

writ requested in this petition.

3 The grounds alleged by the petitioner in both the first and second

petitions for certiorari are as follows:

“Petitioner respectfully shows unto this Honorable Court as fol

lows:

1. That the Circuit Court erred in entering its order of July 11,

1956, requiring petitioner to produce certain documents and papers

set out therein.

2. That the Circuit Court erred in overruling petitioner’s motion

to set aside its order to produce.

3. That the Circuit Court erred in adjudging petitioner in con

tempt and assessing a $10,000 fine against it as punishment therefor.

4. That the Circuit Court erred in punishing petitioner $10,000

for contempt in excess of its statutory authority under Title 13,

Section 143 of the Alabama Code of 1940.

5. That the Circuit Court erred in overruling petitioner’s motion

to set aside and/or modify its order and judgment adjudging pe

titioner in contempt and/or stay execution of its judgment pending

review by this Court.

6. That the Circuit Court erred in adjudging petitioner in con

tempt and in assessing a $10,000 fine against it as punishment there

for.

7. That the Circuit Court erred in punishing and fining petitioner

$100,000 for contempt in excess of its statutory authority under

Title 13, Section 143 of the Alabama Code of 1940.

8. That the Circuit Court erred in granting the temporary re

straining order.

9. That the Circuit Court erred in failing to dissolve its injunc

tion and in refusing to permit petitioner to register with the Sec

retary of State after it had tendered compliance with its answer.

10. That all of the errors committed by the Circuit Court and set

forth above are in violation of petitioner’s right and the rights of

its members to due process of law and equal protection of the

laws secured under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States, and violate petitioner’s rights under the

commerce clause of the Federal Constitution.”

9

ARGUMENT

I.

THE JUDGMENT BELOW BASED UPON

STATE PROCEDURE DISPOSED OF ALL QUES

TIONS PROPERLY RAISED BY PETITIONER, AND

LEFT NO FEDERAL QUESTION TO BE RE

VIEWED BY THIS COURT.

In asserting its claim that the judgment below em

ployed the device of State procedure to preclude re

view by the United States Supreme Court, the pe

titioner attempts to show that the Supreme Court of

Alabama departed from a long standing State pro

cedure of permitting review of contempt proceedings

by certiorari. That opinion reveals the error of this

contention. It is clear that the Alabama Court reaf

firmed its rule that certiorari was the proper method

by which to review contempt, by citing, Ex parte D ick

ens, 162 Ala. 272, 50 So. 218. The gist of the opinion

is that if the petitioner felt aggrieved by the trial

court’s order to produce its proper remedy was a pe

tition for writ of mandamus in the Supreme Court to

compel the trial judge to set aside his order. By this

means the aggrieved party can obtain review without

the danger of a contempt citation. B u t petitioner

chose another course, though it had ample time in

which to have filed mandamus proceedings prior to

July 25, 1956. Petitioner chose to test the order to

produce by a refusal to obey based upon vaguely des

ignated constitutional rights. The Supreme Court of

Alabama then reviewed the contempt proceedings

with a view to determining if the trial court had jur

isdiction of the person, subject matter and whether it

10

had exceeded its authority. Its greatest preoccupation

was naturally with the nature of the contempt, civil

or criminal? It needs no extensive argument or cita

tion of authorities to show that its conclusion on this

point was sound. See Ex parte King, 263 Ala. 487, 83

So. 2d 241; and U nited States v. U nited M ine W orkers

of Am erica, 330 U. S. 258.

But the petitioner asserts that because, in Ex

parte Morris, 252 Ala. 551, 42 So. 2d 17, Morris, who

had refused to produce names of Klu Klux Klan mem

bers before a grand jury, obtained a review of a con

tempt citation by petition for certiorari, the Nation

al Association for the Advancement of Colored Peo

ple, has in some mysterious fashion been aggrieved in

the case at bar. However, it can readily be seen that

Morris’ contempt was occasioned by his refusal to

answer a question before a grand jury upon direct or

ders of a judge. He had no opportunity to test the pro

priety of the questioning by petition for mandamus

but because of the immediate action of the judge in

sentencing him to jail he was left to the remedy of

certiorari. It is otherwise, with petitioner herein who

had sixteen days in which to file his petition for man

damus to review the order to produce.

In any event, in both, Ex parte Morris, 252 Ala.

551, 42 So. 2d 17, and the case at bar, the Alabama

Supreme Court considered the rights of the petition

ers to refuse to produce their records on the grounds

of privilege against self-incrimination and security

against unreasonable searches and seizures. While cit

ing Federal cases to demonstrate that these rights had

not been violated, the Alabama court correctly treated

them as matters of State law, in view of the holding

11

of the United States Supreme Court, that the due

process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment does

not incorporate the first eight amendments to th e

United States Constitution. Adam son v. California,

332 U. S. 4 6 ; and W olf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25. Es

pecially, the Fourth Amendment has been held not to

be a monitor upon State rules concerning searches and

seizures unless the State action complained of was so

shocking as to amount to fundamental unfairness. N a

tional Safe Deposit Company v. Stead, 232 U. S. 58. It

is true that such cases as W olf v. Colorado, 338 U. S.

25, contain language supporting the proposition that

the Fourteenth Amendment implements the Fourth

Amendment as against State action. A reading of the

majority opinion at page 27, dispels this notion:

“The security of one’s privacy against ar

bitrary intrusion by the police—which is at

the core of the Fourth Amendment—is basic

to a free society. It is therefore implicit in

the ‘the concept of ordered liberty’ and as

such enforceable against the States through

the Due Process Clause. The knock at the

door, whether by day or by night, as a prelude

to a search, without authority of law but sole

ly on the authority of the police, did not need

the commentary of recent history to be con

demned as inconsistent with the conception

of human rights enshrined in the history and

the basic constitutional documents of Eng

lish-speaking peoples.

Accordingly, we have no hesitation in say

ing that were a State affirmatively to sanc

tion such police incursion into privacy it

12

would run counter to the guaranty of the

Fourteenth Amendment...

From the above it is evident that the court did

not decide that the Fourth Amendment in its de

tailed entirety was an inhibition upon State action

but rather that arbitrary oppressive police action is a

violation of due process.

Insofar as petitioner’s asserted rights under the

Commerce Clause of Article I, Section 8 of the United

States Constitution are concerned, it is submitted that

the extent and nature of its activities in Alabama are

the determinant facts for deciding what limitations

the State might place upon those activities. That the

State has power over foreign corporations, even the

power of ouster, is established law. See State Ex rel.

Griffith v. Knights of the Klu Klux Klan, 117 Kan.

564, 232 P. 254, cert, denied 273 U. S. 664; and As-

bury H ospital v. Cass County, 326 U. S. 207. The pe

titioner takes the anomalous position that its activi

ties are protected by the Commerce Clause and then

refuses the sovereign the right to examine its records

to ascertain the applicability of that Clause to those

activities and the corresponding limitation, if any,

upon the State’s power of control. A similar argument

was made in Oklahom a Press Publishing Co. v. W all

ing, 327 U. S. 186. This court refused it and held that

the Wages and Hours Administrator had the authority

to examine the newspaper’s records to determine

whether or not the Wages and Hours Laws applied

to the company and whether it was violating them.

We finally come to the privilege and immunities

clause of the First Amendment, as protected by the

Fourteenth Amendment, a right so vigorously as

13

serted by the petitioner in its application to this

Court. At no point does it appear that these rights, if

petitioner own any such, were urged by it before any

Court of Alabama. A multitude of cases lay down the

rule that the United States Supreme Court will not as

sume jurisdiction when a Federal question has not

been properly presented in the Federal court. One

such case is Herndon v. Georgia, 295 U. S. 441, in

which Mr. Justice Sutherland said at page 442:

“It is true that there was a preliminary at

tack upon the indictment in the trial court on

the ground, among others, that the statute

was in violation ‘of the Constitution of the

United States,’ and that this contention was

overruled. But, in addition to the insufficien

cy of the specification, the adverse action of

the trial court was not preserved by excep

tions pendente lite or assigned as error in due

time in the bill of exceptions, as the settled

rules of the state practice require. In that sit

uation, the state supreme court declined to

review any of the rulings of the trial court in

respect of that and other preliminary issues;

and this determination of the state court is

conclusive here. . . .”

More recently, the case of W illiam s v. Georgia,

349 U. S. 375, turned upon the fact that this Court

considered that the petitioner therein had raised a

Federal question in the manner prescribed and per

mitted by Georgia procedure but that the Georgia

court refused to consider the question raised. The dis

senting opinion took a contrary view of the Georgia

procedure but all Justices agreed that for the United

14

States Supreme Court to consider a Federal Constitu

tional question it must have first been properly raised

in the state court in accordance with state procedure.

n.

The petitioner herein argues that it was denied

due process of law by the totality of the State action

in the case to date. It is not entirely clear whether the

basis of this contention is the denial to the corporation

of a fair hearing or alternatively that because the pres

ent state of the case leaves it out of business in Ala

bama, and precluded from further contest in the Ala

bama courts pending its purging itself of contempt,

it has been denied certain rights guaranteed by the

privileges and immunities clause of Section 1 of the

Fourteenth Amendment. In addition, the corporation

seems to be asserting certain First Amendment rights

of its members and members of the Negro race in

general. It is somewhat difficult to detect the indi

vidual ingredients in its melange of asserted rights

and grievances.

The course of petitioner’s argument, if we may

change our metaphor, seems to be that, because the

State incidentally to an equity action against it, de

manded the names of its members possibly causing

harrassment and discouragement of these members by

private individuals, possibly causing them to discon

tinue membership in the corporation, possibly leading

to its ultimate weakening and demise, the rights of

both the members and the corporation to freedom of

speech, assembly, and redress of grievances have been

abridged by the State. Petitioner alleges that it is the

main effective voice of Negro citizens attempting to

assert their constitutional rights. Thus, it argues its

15

rights depend upon its members and its members’

rights upon it. They are together a sort of legal flagel-

latae spawning interdependant constitutional rights.

Tangential to the circle of this main argument is the

assertion of privilege against self-incrimination and

freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures.

In building up the picture of the State, acting

through its Attorney General and its courts to de

prive petitioner of its rights, request is made that

the Court take judicial notice of what is called “pub

lic information.” Petitioner’s brief, pages 19 through

25. While we do not agree that the elasticity of judicial

notice stretches to include all the various hearsay,

opinions and speculation included on these pages, if

it is petitioner’s contention that the great majority of

people in Alabama favor segregation, to that one fact

we accede.

However, in addition, the impression is given by

the footnotes on pages 23 through 25, of petitioner’s

brief, that somehow orthodox Alabama procedure was

departed from so as to place the corporation in the

position of having to disclose its membership ere it

could proceed to a hearing on its motion to dissolve

the temporary injunction and ultimately on the merits

of the case. This impression is false. The motion to

produce was granted on notice and hearing. Ample

time was given to contest it by mandamus or to com

ply. The material requested was relevant to proof of

the nature and method of petitioner’s business in Ala

bama. Such proof was relevant to determine whether

the temporary injunction should remain in effect and

whether or not a permanent injunction, and finally

an order of ouster should be granted. While it is true

that generally speaking oral testimony is not taken on

16

a motion to dissolve a temporary injunction, ex parte

affidavits of parties are permitted. Profile Cotton

M ills v. Calhoun W ater Co., 189 Ala. 181, 66 So. 50,

and Title 7, Section 1061, Code of Alabama 1940. The

names and addresses of petitioner’s members were

needed for the State’s preparation of affidavits in op

position to the motion to dissolve. Furthermore, the

course which the trial would take was uncertain.

Whether or not the temporary injunction was dis

solved, a trial on the merits could have followed im

mediately. In that event the State needed to examine

the corporation’s records to prepare its proof of the

allegations of the bill of complaint. While petitioner

admitted in its answer some of the State’s allegations

it denied solicitation of members for either the local

chapters or the parent corporation, or that it had or

ganized local chapters within the State. See petition

er’s brief, page 8. It would be a strange rule that a

party may not examine documents to aid in the prep

aration of a case until such time as trial on the merits

has commenced in court.

While the defenses to production of the requested

records of privilege against self-incrimination and

freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures are

peripheral to the petitioner’s arguments, a word con

cerning them is in order. That neither of these rights

is infringed upon by such an order to produce was

established as early as H ale v. H enkel, 201 U. S. 43,

and carried down to United States v. W hite, 322 U.

S. 694; and Rogers v. U nited States, 340 U. S. 367.

This brings us to the central question raised by

the petitioner. Does a corporation have the right to re

fuse to disclose the names of its members on the spec

ulation that they may be exposed to public scorn and

17

dislike and to possible unfair economic and social

pressures by private citizens? The answer is no.

First of all, neither the privileges and immunities

of the First Amendment nor the rights created by the

Fourteenth Amendment are protected against indi

vidual as contrasted with state action. United States

V . Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542; and Pow e v. United States,

109 Fed. 2d 147, (C. A. 5), cert, denied U nited States

v. Powe, 309 U. S. 679.

Secondly, and most important, a corporation may

not assert the privileges and immunities of its indi

vidual members. Whether this be considered merely

as a statement of the rule that a party may not as

sert rights personal to another party or more import

ant a statement that the rights to freedom of speech;

assembly and redress of grievances are reserved to

natural persons, it is still the law.

This Court has held:

“Natural persons, and they alone, are entitled

to the privileges and immunities which Sec

tion 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment secures

for ‘citizens of the United States.’ Only the

individual respondents may, therefore, main

tain this suit.” H ague v. Committee for Indus

trial O rganization, 307 U. S. 496, at page

514.

See also International Ladies Garment W orkers U n

ion, A. F. L. v. Seam prufe, Inc., 121 Fed. Supp. 165

(D. C. E. D. Okla.) ; and Local 309 U nited Furniture

W orkers of Am erica, C. I. O. v. Gates, 75 Fed. Supp.

620 (D. C. N. D. Ind.).

18

These cases would seem to dispose of all ques

tions, even those raised by the line of cases cited on

page 18 of petitioner’s brief. Of these only, United

States v. Rumely, 345 U . S. 41 and Pierce v. Society

of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510, would seem to support the

petitioner’s right to assert rights on behalf of its mem

bers or to claim that injury to its members was injury

to it. The other cases are distinguished by the fact

that the person or company asserted its own right.

For example, Burstyn, Inc. v. W ilson, 343 U. S. 495;

Pennekam p & the M iami Herald Publishing Co. v.

Florida, 328 U. S. 331, deal with direct censorship of

the press. Thom as v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516, involves an

attempt at prior censorship of a speech by a labor or

ganization. The right asserted was individual and

personal. Pierce v. Society Sisters, 268 U. S. 510, can

be explained on the theory that the denial of the right

of individuals to send their children to private schools

eliminated by state action the means of livelihood and

property rights of the private schools of Oregon. It is

distinguishable from the case at bar, on the grounds

that the statute operated on the individuals to pre

vent their doing business with private schools, and

thereby directly destroyed a property interest of those

schools. U nited States v. Rumely, 345 U. S. 41, is also

distinguishable. It deals principally with freedom of

the press. It is true that the court vindicated Rumely’s

refusal to disclose the names of the persons to whom

he sold his publications. There was no majority opin

ion holding that his refusal could be based upon con

stitutional grounds. Mr. Justice Black did say that the

freedom of the press was involved but it is clear that

what concerned him was harassment of the press by

public officials rather than the sensitivity of Rumely’s

readers who might be exposed to public gaze.

19

The words of Mr. Justice Jackson in the Joint

A ntifascist R efugee Com m ittee v. McGrath, 341 U . S.

123, at pages 183 and 184, are particularly apposite

to the case at bar:

“I agree that mere designation as subversive

deprives the organizations themselves of no

legal right or immunity. By it they are not

dissolved, subjected to any legal prosecution,

punished, penalized, or prohibited from car

rying on any of their activities. Their claim

of injury is that they cannot attract audi

ences, enlist members, or obtain contributions

as readily as before. These, however, are

sanctions applied by public disapproval, not

by law. It is quite true that the popular cen

sure is focused upon them by the Attorney

General’s characterization. But the right of

privacy does not extend to organized groups

or associations which solicit funds or mem

berships or to corporations dependant upon

the state for their charters. The right of in

dividuals to assemble is one thing; the claim

that an organization of secret undisclosed

character may conduct public drives for

funds or memberships is another. They may

be free to solicit, propagandize, and hold

meetings, but they are not free from public

criticism or exposure. If the only effect of the

Loyalty Order was that suffered by the or

ganizations, I should think their right to re

lief very dubious.”

The petitioner has attempted to make of this a

segregation case. It is not. It involves merely the power

20

of a state to compel foreign corporations operating

within its borders, whatever their purpose, whether

they be profit or non-profit, to conform to the laws

applicable to all foreign corporations enacted for the

protection of the citizens of Alabama. The merits of

the State’s proceeding in equity to enjoin and oust

the corporation from Alabama are not before this

Court. Perhaps they never will or should be. That the

petitioner is entitled ultimately to a hearing on the

merits of the case is basic to our law. But it is the pe

titioner’s own recalcitrance which has prevented its

proceeding to the merits. The rule of law forbidding

a party in equity who is in contempt of court contin

uing further with a case is neither novel nor unfair.

It makes the best of sense that a party who refuses to

divulge information necessary to the conduct of a case

should be prevented continuing with it. The petitioner,

on mere speculation of injury by private individuals

to what it construes to be the rights of its members,

refuses to deliver to the court a list of that member

ship. It also arrogates the constitutional rights of

its members to itself, asserting a dubious infringe

ment based not on State but on individual action. If

such resistance to the orderly process of a trial is per

mitted, corporations and particularly membership

corporations will be permitted to place themselves

above and outside the law. If we may be permitted a

supposition, no more far fetched than some of those

in petitioner’s brief, we pose the situation of a promi

nent labor leader, under investigation, who refuses to

produce records of his Union, even its membership,

on the grounds that those members might be incrimi

nated or perhaps because of the odious reputation of

the particular Union held up to public scorn with a

resulting fall in Union membership and Union power.

21

Can it be said that a Union official could refuse these

records on such a basis. The answer is no. How then

does the petitioner’s case differ? It does not. For

these reasons there is no merit in its refusal to obey

the order to produce issued by a court of Alabama,

having jurisdication of both person and subject mat

ter. *•

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons this petition for certi

orari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

JOHN PATTERSON

Attorney General of Alabama

v MacDONALD GALLION

Assistant Attorney General of

Alabama

EDMON L. RINEHART

Assistant Attorney General of

Alabama

Counsel For Respondent

JAMES W. WEBB

Assistant Attorney General

of Alabama

Of Counsel On Brief

22

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Edmon L. Rinehart, one of the attorneys for

the respondent, The State of Alabama, and a mem

ber of the Bar of the Supreme CourUof the United

States, hereby certify that on the ../ fl .—r day of May

1957, I served copies of the foregoing brief in opposi

tion on Arthur D. Shores, 1630 Fourth Avenue, North,

Birmingham, Alabama, by placing a copy in a duly

addressed envelope, with first class postage prepaid,

in the United States Post Office at Montgomery, Ala

bama, and on Thurgood Marshall, 107 West 43rd

Street, New York, New York, by placing two copies

in a duly addressed envelope, with Air Mail postage

prepaid, in the United States Post Office at Mont

gomery, Alabama.

I further certify that this brief in opposition is pre

sented in good faith and not for delay.

EDMON L. RINEHART

Assistant Attorney General of

Alabama

Judicial Building

Montgomery, Alabama