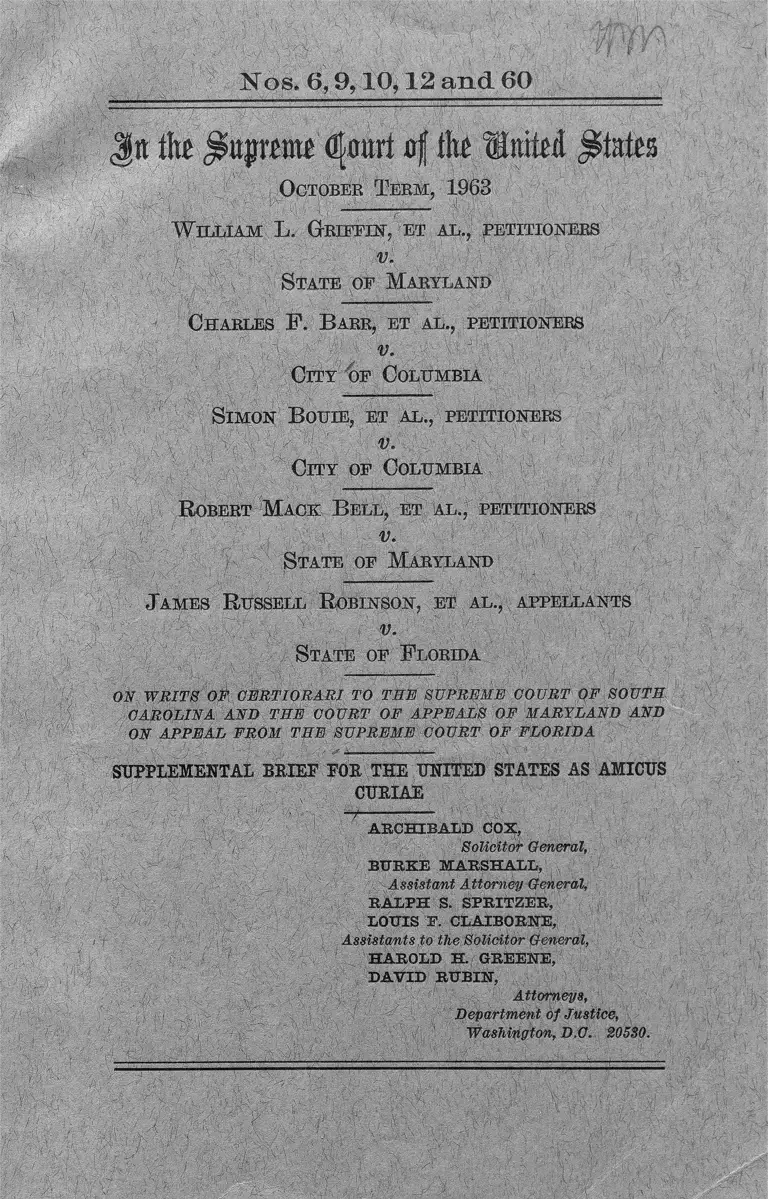

Griffin v. Maryland Supplemental Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Griffin v. Maryland Supplemental Brief Amicus Curiae, 1964. 290e59c5-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/de17861c-5848-4a31-b771-2a5e9cc2abd1/griffin-v-maryland-supplemental-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 19, 2026.

Copied!

N o s . 6 ,9 ,1 0 ,1 2 a n d 60

Jtt fte (§mxt of t h SttM States

October Term, 1963

W illiam L. Griffin. et al., petitioners

: V. ' ■ -

State of Maryland

Charles F . B arr, et al., petitioners

City op Columbia

v.

Simon B ouie, et al., petitioners

v.

City op Columbia

R obert Mack Bell, et al., petitioners

' v . -

State op Maryland

J ames R ussell Robinson, et al., appellants

' v.

State op F lorida

ON W R IT S OF CERTIO RARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH

CAROLINA AND THE COURT OF APPEALS OF M ARYLAND AND

ON APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOE THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS

CUEIAE

*7-----------

ARCHIBALD COX,

Solicitor General,

BURKE MARSHALL,

Assistant Attorney General,

R A LPH S. SPRITZER,

LOUIS P. CLAIBORNE,

Assistants to the Solicitor General,

HAROLD H„ GREENE,

DAVID RUBIN,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.O. 20530.

I N D E X

Pse<4

Question presented_________________________________ 5

Argument:

Introductory----------------------------------------------------- 7

I. The refusal to allow Negroes to eat with other

members of the public or to share amusement

in these places of public accommodation was an

integral part of a wider system of segregation

established by a combination of governmental

and private action to subject Negroes to caste

inferiority________________________ 21

A. Acts of racial discrimination in places of

public accommodation are parts of a

community-wide practice stigmatizing

Negroes an inferior caste____________ 23

B. The States have shared in establishing the

system of racial segregation of which dis

crimination in places of public accommo

dation is an inseparable part_______ 40

Slavery and the free Negro before the

Civil W ar_____________________ 41

Emancipation and its aftermath____ 45

Jim Crow and segregation_________ 50

II. For a State to give legal support to a right to main

tain public racial segregation in places of public

accommodation, as part of a caste system

fabricated by a combination of State and

private action, constitutes a denial of equal pro

tection of the laws________________________ 64

A. Where racial discrimination becomes effec

tive by concurrent State and individual

action, the responsibility of the State

under the Fourteenth Amendment de

pends upon the importance of the ele

ments of State involvement compared

with the elements of private choice___ 66

i719- 946— 64 (X)

II

II. For a State to give legal support, etc.—Continued

B. In the present cases the elements of State

involvement are sufficiently significant,

in relation to the elements of private

choice, to carry responsibility under the Page

Fourteenth Amendment_____________ 80

1. The States are involved through

the arrest, prosecution and con

viction of petitioners_________ 80

2. The States are involved in the

practice of discriminating

Argument—Continued

against Negroes in places of

public accommodation because of

their role in establishing the

system of segregation of which

it is an integral part__________ 90

3. The States are involved in the dis

crimination because of their

traditional acceptance of re

sponsibility for, and detailed

regulation of, the conduct of the

proprietors of places of public

accommodations towards the

general public to which they

have opened their businesses___ 93

4. These cases involve no substantial

element of private choice______ 104

C. The imposition of State responsibility

would give effect to the historic purposes

of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments--------------------- 111

_______________________________________ . 145Conclusion

r«

CITATIONS

Cases in this Court: ijage

American Federation of Labor v. Swing, 312 U.S. 321__ 81

Anderson v. Martin, No. 51, this Term, decided January

13, 1964____________________________ 62

Avent v. North Carolina, 373 U.S. 375______________ 26

Bailey v. Patterson, 368 U.S. 346, 369 U.S. 31______ 26

Barr v. Columbia, No. 9, certiorari granted, 374 U.S.

804 _____ ________________________________ 26

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249_________________ 72

Bell v. Maryland, No. 12, certiorari granted, 374 U.S.

805 _______________________________________ 26

Black v. Cutter Laboratories, 351 U.S. 292__________ 82

Bouie v. Columbia, No. 10, certiorari granted, 374 U.S.

805_________________________________________ 26

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454_________________ 26

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483________ 50, 111

Buchanan v. War ley, 245 U.S. 60_________________ 89

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715_ 3,

15, 26, 68, 69, 70, 72, 88, 102

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296___________ __ 81

Child Labor Tax Case, 259 U.S. 20_______ ________ 80

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3____________________ 9,

10, 66, 73, 78, 94, 95, 135, 136

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 220

F. 2d 386, affirmed, 350 U.S. 877_______________ 58

District of Columbia v. Thompson, 346 U.S. 100_____ 30

Drews v. Maryland, No. 3_______________________ 26, 31

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229___________ 26

Florida, ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 347 U.S.

971, 350 U.S. 413, 355 U.S. 839_____________60

Ford v. Tennessee, No. 15__________ :_____________ 26

Fox v. North Carolina, No. 5_____________________ 26

Garner v. Louisiana, Briscoe v. Louisiana, Hoston v.

Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157_________ ___________ 26, 31, 62

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U.S. 903, affirming 142 F. Supp.

707_________________________________________ 68

Gober v. Birmingham, 373 U.S. 374________________ 26

Griffin v. Maryland, No. 6, certiorari granted, 370 U.S.

935, reargument ordered, 373 U.S. 920__________ 26

Hamm v. Rock Hill, No. 105_____________________ 26

IV

Cases in this Court—Continued Page

Henry v. Virginia, 374 U.S. 98___________________ 26

International Ass’n of Machinists v. Street, 367 U.S.

740_______________________________________ 71,73,89

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U.S. 61_________________ 63, 111

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267_____ _________ 3, 15,

26, 27, 65, 68, 70, 72, 90, 94

Lupper v. Arkansas, No. 432________ !___ ________ 26

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501______________ 20, 69, 110

McCabe v. A.T. cfe S.F. By. Co., 235 U.S. 151_______ 68

Mitchell v. Charleston, No. 8_____________________ 26

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167____________________ 84

Monroe v. Pape, 367 U.S. 167_____________ ___ ___ 118

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n., 347 U.S.

971, reversing and remanding 202 F. 2d 275______ 68

Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113___________________ 94, 110

NAACP v. Webb’s City, No. 362__________________ 26

National Labor Relations Board v. Southern Bell Co.,

319 U.S. 50_________________________________ 19, 109

Pennsylvania v. Board of Trusts, 353 U.S. 230______ 15, 71

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U.S. 244________________3,17,

26, 40, 55, 65, 68, 70, 72, 90, 107

Public Utilities Comm. v. Poliak, 343 U.S. 451______ 71, 95

Railroad Company v. Brown, 17 Wall. 445__________ 30

Railway Employees’ Dept. v. Hanson, 351 U.S. 225- 15, 71, 89

Randolph v. Virginia, 374 U.S. 97 (remanded)_______ 26

Rice v. Sioux City Memorial Park Cemetery, 347 U.S.

942_________________________________________ 82

Robinson v. Florida, No. 60, probable jurisdiction

noted, 374 U.S. 803_____________________ 2, 26, 28, 106

Scott v. Sandford, 19 How. 393___________________ 36

Shelly v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1_____- ___________ 13, 72, 88

In re Shuttlesworth, 369 U.S. 35___________________ 26

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 373 U.S. 262___ 26

Slaughter-House Cases, 16 Wall. 36______________ 112, 141

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 149____ ______________ 69

Steele v. Louisville cfe N. R. Co., 323 U.S. 192_ 68, 71, 89, 103

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303____________ 111

Swift <& Co. v. United States, 196 U.S. 375________ 19, 109

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U.S. 154________________ 26

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461_____ ____ ___ 19, 69, 109

Texas cfe N. 0. R. Co. v. Brotherhood of Railway & S.S.

Clerks, 281 U.S. 548_________________________ 19 ,109

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U.S. 199______________ 31

V

Cases in this Court—Continued Page

Thompson v. Virginia, 374 U.S. 99------------------------ 26

Turner v. City of Memphis, 369 U.S. 350----------------- 26, 68

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542----------------- 66

United States v. Harris, 106 U.S. 629---------------------- 66

United States v. Rumely, 345 U.S. 41---------------------- 80

Williams v. North Carolina, No. 4---------- 26

Wood v . Virginia, 374 U.S. 100-------------------- 26

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284---------------- 26

Other cases:

Abstract Investment Co. v. William 0. Hutchinson,

22 Cal. Reptr. 309_______ ______ :-------------------- 88

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750------- ----------- -— 71

jfennett v. Mellor (1793) 5 Term R. 273------ - 94

Bohler v. Lane, 204 F. Supp. 168--------------------------- 57

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 _— 103

Bowen v. Independent Publishing Company, 230 S.C.

509, 96 S.E. 2d 564------------- --------------------------- 59

Boyer v. Garrett, 183 F. 2d 582-.-------------------------- 58

Bryan v. Walton, 14 Ga. 185-------------------------------- 37

Capitol Federal Savings and Loan Ass’n v. Smith, 316

P. 2d 252-_______________________ ---------------- 83

Carlisle v. J. Weingarten, Inc., 137 Tex. 220, 152 S.W.

2d. 1073-_--____________ ____ : -------— --------- 32

Catlette v. United States, 132 F. 2d 902 ---------------- - 83

Clifton v. Puente, 218 S.W. 2d 272------------------------- 83

Coger v. The North West. Union Packet Co., 37 Iowa

145_________________________________________ 130

Coke v. City of Atlanta, Ga., 184 F. Supp. 579---------- 68

Cook v. Patterson Drug Co., 185 Va. 516, 39 S.E. 2d

304-.----------------- ----- ----------------------------------- 35

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore City,

220 F. 2d 386______________________________ -- 58

DeAngelis v. Board, 1 R.R.L.R. 370----------------------- 57

Department of Conservation <& Development v. Tate,

231 F. 2d 615----------- ----------------- ------------------ 68, 71

Derrington v. Plummer, 240 F. 2d 922------------- 68, 71, 111

Donnell v. State, 48 Miss. 661------------------------------- 129

Ferguson v. Gies, 82 Mich. 358---------- 123

Grant v. Knepper, 245 N.Y. 158, 156 N.E. 650--------- 102

Hamilton v. State, 104 So. 345----------------------------------- 31

Hendrickson v. Hodkin, 276 N.Y. 252, 11 N.E. 2d 899_ 102

Hinson v. United States, 257 F. 2d 178— . — ..--------- 101

VI

Jones v. Marva Theatres, Inc., 180 F. Supp. 49_____ 57, 88

Joseph v. Bid-well, 28 La. Ann. 382________________ 129

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library of Baltimore City,

149 F. 2d 212_____________________________ 58, 69, 71

Kidd v. Thomas A. Edison, Inc., 239 Fed. 405_____ 102

Lane v. Cotton (1701) 12 Mod. 472______________ __ 94

Law v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 78 F.

Supp. 346___________________________________ 58

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004___ ____ ____ 68

Lynch v. United States, 189 F. 2d 476______________ 83

Madden v. Queens County Jockey Club, 296 N.Y. 249,

72 N.E. 2d 697, certiorari denied 332 U.S. 761____ 103

McDuffie v. Florida Turnpike Authority, 7 E.R.LJl.

505_________ 68

McKibbin v. Michigan C. and S.C., 369 Mich. 69, 119

N.W. 2d 557_________________________________ 103

Miller v. Gaskins, 11 Fla. 73____________________ 42

Nelson v. Natchez, 19 So. 2d 747__________________ 31

Picking v. Pennsylvania Railroad Company, 151 F. 2d

240-________________________________________ 83

Pinate v. Dolby, 1 Dallas 167____________________ 36

Pontardawe R. C. v. Moore-Gwyn, 1 Ch. 656, 98 L.J.

Ch. 424_____________________________________ 101

Renjro Drug Co. v. Lewis, 149 Tex. 507, 235 S.W. 2d

609_________________________________________ 32

Sauvinet v. Walker, 27 La. Ann. 14, affirmed, 92 U.S.

90__________________________ 129

Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Hospital, No. 8908 (C.A. 4,

November 1, 1963)________________________ 71

Simonsen v. Thorin, 120 Neb. 684, 234 N.W. 628----- 92

Slavin v. State, 249 App. Div. 72, 291 N.Y. Supp. 721. 92

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, Inc., 220 F. Supp.

1________________________________________ 68, 69,71

State v. Brown, 195 A. 2d 379____________________ 82, 85

Thompson v. The Baltimore City Passenger Railway

Co_________________________________________ 51

Thompson v. Lacy (1820), 3 Barn, and Aid. 283_____ 94

Warbrook v. Griffin (1609), 2 Brownl. 254__________ 94

White’s Case (1558) Dryer 158b__________________ 94

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d

845_________________________________________ 103

Willis v. McMahon, 89 Cal. 156__________________ 77

Other cases—Continued Pags

VII

Wood v. Hogan, 215 F. Supp. 53,--------------------------- 103

Yarbrough v. State, 101 So. 231 (Ala.)--------------------- 32

U.S. Constitution and statutes:

Thirteenth Amendment._7, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 21, 45, 60, 64,

65, 111, 113,114

Fourteenth Amendment-------------------------------------- 6,

7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 20, 21, 22, 41,48, 60,

64, 65, 66, 70, 78, 79, 81, 84, 86, 88, 91, 96, 110,

111, 114, 118, 127.

Section 1_____________________________ 66,117, 140

Section 5__________________________ 20, 66,117, 140

Fifteenth Amendment_________________________ 7,10,

12, 13, 14, 15, 21, 60, 64, 65, 111, 114

Civil Eights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27-------------------- 45, 48,

113, 114, 117, 118,124,127, 131

Civil Eights Act of 1875, 18 Stat. 335-------------------- 30,

74,113,124,131,133

Civil Eights Act, 28 U.S.C. 1343__________________ 83

Ku Klux Act of 1871, 17 Stat. 13_________________ 113

Supplementary Freedmen’s Bureau Act, 14Stat. 173. 113, 114

State constitutions and statutes:

Alabama:

Const., 1875, Art. X III, § 1--------------------------- 49

Laws:

1868, p. 148___________________________ 49

1873, p. 176____________________________ 49

City codes:

Birmingham Code, 1944:

§ 369_____________________________ 56

§ 859_____________________________ 56

§ 939_____________________________ 56

§ 1110____________________________ 56

§ 1604____________________________ 56

Gadsden Code, 1946, § 8-18______________ 56

Montgomery Code, 1952:

§ 10-14___________________________ 56

§ 13-25___________________________ 56

§ 25-5_____________________ 56

§ 28A-2____ 56

§ 28A-5___________________ 56

§ 34-5____________________________ 56

Ch. 20-28_________________________ 56

Other Cases—Continued pSg*

VIII

State constitutions and statutes—Continued

Alabama—Continued

City Codes—Continued

Selma Code (1956 Supp.): Pag»

§ 627-1______________________ 56

§ 627-6____________________________ 56

Alaska Stat., 1962, § 11.60.230________________ ___ 31

Arkansas:

Laws, 1873:

Pp. 15-19_________________________ 49, 77,128

P.423________________________________ 49

Stat. Ann., § 71-1801__________________ ____ 61

California Civ. Code, § 51_______________________ 31

Colorado Rev. Stat., 1953, § 25-1-1_______________ 31

Connecticut Gen. Stat. (1962 Supp.), § 53-55______ 31

Delaware Code Ann., § 24-1501__________________ 61

District of Columbia Code., 1961, § 47-2907________ 31

Florida:

Const., 1885:

Art. XII, § 12__________________________ 50

Art. XVI, § 24_________________________ 59

Codes:

Administrative:

Ch. 1700:

§ 8.06_________________ 2, 57, 62, 91, 99

§ 16__________________________ 97

Ch. 175:

§ 175-1_______________________ , 97

§ 175.1.03_____________________ 99

§ 175-2_______________________ 97

§ 175-4_______________________ 97, 98

§ 175.4.02_____________________ 98

State Sanitary Code: Ch. VII, § 6________ 2

Digest Laws, 1881: Pp. 171-172______________ 51

Laws:

1842, ch. 32____________________________ 44

1847-1848, ch. 155______________________ 44

1856', ch. 794, 795_______________________ 44

1858-1859, ch. 860______________________ 44

IX

State constitutions and statutes—Continued

Florida—Continued

Laws—Continued

1865-1866: Page

Pp. 23-39__________________________ 48

P. 25, ch. 1466, § 14________________ 48

Pp. 41-43, ch. 1479, §§ 1, 3 , — . _____ 48

1873:

Ch. 1947___ 76

Ch. 1947, p. 25____________________49, 128

1881, ch. 3283, p. 86___________ 50

1887, ch. 3743, p. 116___________________ 52

1891, ch. 4055, p. 92____________________ 51

1895, ch. 4335, p. 96_______ ____________ 50, 54

1897, ch. 4167, pp. 107-108______________ 54

1903, ch. 5140, p. 76____________________ 58

1905:

Ch. 5420, p. 99_____________________ 54

Ch. 5447, § 1, p. 132________________ 54

1907:

Ch. 5617, p. 99_____________________ 53

Ch. 5617, § 6, p. 100________________ 54

Ch. 5619, p. 105________ 53

1909:

Ch. 5893, § 1, p. 40_________________ 53

Ch. 5967, pp. 171, 171-172___________ 54

1913, ch. 6490, p. 311___________________ 54

Rev. Stat. 1892, p. V III_____________________ 51

S tat.:

§ 1.01(6)______________________________ 59

§ 228.09__________________________ 50,63

§§ 352.03-352.18_______________________ 60

Ch. 154_______________________________ 97

Ch. 381_______________________________ 97

Ch. 509_______________________________ 97

§ 509.032__________________________97, 99

§ 509.211__________________________ 98

§ 509.221__________________________ 97

§ 509.271______________________ 97

§ 509.292__________________________ 98

§ 509.092__________________________ 61

§ 509.141__________________________ 61

§§ 741.11-741.16_______________________ 59

§ 871.04_______________________________ 99

§§ 950.05-950.08_______________________ 63

X

State constitutions and statutes—Continued

Florida—Continued

City codes and ordinances: Par«

Dade County Code, § 2-77______________ 97

Jacksonville City Codes:

1917, § 439____________ ___________ 58

1953:

§§ 39-65, 39-70________________ 58

§§ 39-15, 39-17________________ 58

Miami Code:

Ch. 25___________ 97

Ch. 35____________________________ 97

Tampa City Code, § 18-107--------------------- 58

Emergency Ordinance No. 236 of the City of

Delray Beach, reprinted in 1 R.R.L.R. 733

(1956)___ 63

Georgia:

Laws:

1870, pp. 398, 427-428___ _____________ 49, 128

1872, p. 69_____________________________ 49

City Codes:

Atlanta, 1942:

§ 36-64.____________ 56

§ 38-31___________________________ 56

§ 56-15___________________________ 56

Augusta, 1952, § 8-2-26_________________ 56

Idaho Code (1963 Supp.) § 18-7301----------------------- 31

Illinois Stat., 1961, § 38-13.1_____________________ 31

Indiana Stat. (1963 Supp.) § 10-901---------------------- 31

Iowa Code, 1962, § 735.1________________________ 31

Kansas Laws, 1874, p. 82________________________ 130

Kansas (1961 Supp.) § 21-2424----------------------------- 31

Kentucky Laws: 1873-1874, p. 63------------------------- 49

Louisiana:

Const., 1868, Art. 13_______________________49, 128

Acts:

1869, p. 37________________________ 49, 76, 128

1870, p. 57.__________________________ 76, 128

1872, p. 29_____________________________ 128

1873:

P. 156________________________ 49, 77, 128

P. 157_____________________________ 77

1954, No. 194, repealing former La. R.S. 4:3-

4____________ ______________________ 61

XI

State constitutions and statutes—Continued

Louisiana)—Continued

City codes and ordinances:

Monroe Code, 1958: Page

§ 4-24____________________________ 56

§7-1_____________________________ 56

New Orleans:

Code, 1956, § 5-61.1________________ 56

Com’n Council Ord. No. 4485 (1917)---- 57

Shreveport Code, 1955:

§ 8.2___ 56

§ 8.3___________ 56

§11-47_________ 56

§ 24-36___________________________ 56

§24-56_________- _________________ 56

Maine Rev. Stat. (1963 Supp.) § 137-50___________ 31

Maryland:

Const., 1851, Art. I, § 1------------ 42

Codes:

1860:

Art. 66, § 56_______________________ 43

Art. 66, § 74_______________________ 43

Art. 66, §§ 76-87___________________ 43

1939, Art. 59, § 14___________ 63

1957:

Art. 25, § 14_______________________ 104

Art. 27:

§ 398__________________________ 59,60

§ 506__________________________ 104

Art. 43, §§ 200, 202, 203, 209_________ 103

Art. 56, §§ 178-179_________________ 103

Art. 78A, § 14______________________ .63

1963 Supp., § 49B-11----- 31

Laws:

1801:

Ch. 90___________________________ 42

Ch. 109______________________ 43

XII

State constitutions and statutes—Continued

Maryland—Continued

Laws—Continued

1805, ch. 80__________ - ________________ 43

1809, ch. 83____________________________ 42

1810, ch. 33______________________ 42

1825- 1826, ch. 93_____________________ 43

1826- 1827, ch. 229, § 9________________ 43

1846-1847, ch. 27____ 43

1854, ch. 273______________ 43

1870, ch. 392, pp. 555-556, 706----------------- 50, 54

1872, pp. 650-651_______________________ 50

1882, ch. 291, p. 445____________________ 54

1884, ch. 264, p. 365____________________ 50

1898, ch. 273, pp. 814-817-------------------- --- , 50

1904:

Ch. 109, p. 186_________ ___ - - - - - - 53, 54

Ch. 110, p. 188_____________________53, 54

1908:

Ch. 248, p. 88______________________ 53

Ch. 292, p. 86____ - - - - - - __________ 53

Ch. 617, p. 85______________________ 53

1910, ch. 250, pp. 234, 237-246,-_________ 54

1963, chs. 227, 228_____________________ 60, 104

City and county codes and ordinances:

Baltimore:

City Code, 1950, Art. 12, §§ 24, 107--- 103

Ordinances:

December 19, 1910, #610----------- 58

April 7, 1911, #654______________ 58

May 15, 1911, #692_____________ 58

September 25, 1913, #339----------- 58

Montgomery County Code, 1960, §§ 15-7,

15-8, 15-11, ch. 75__________- - - - - - - - - - 104

Massachusetts:

Acts, 1865, ch. 277, p. 650__________________ 76, 130

Laws, 1956, § 272-92A-------------------------------- 31

Michigan Stat., 1962, §28.343------------------------------ 31

Minnesota Stat., 1947, § 327.09---------------------------- 31

XXXI

State constitutions and statutes—Continued

Mississippi:

Code Ann., § 2046.5-------------------------------------- 61

Laws:

1865:

Ch. 4:

§1------------ — — -------------------- 46

§2____________________________ 46

§ 3--------1-------------------------------- 46

§ 4___________________________ 46

§ 5 ____________~---------------------- 46

§ 6___________________________ 46

§ 7___________________________ 46

§ 8___________________________ 46

1865, ch. 5:

§ 1_______________________________ 46

§ 4_______________________________ 46

1865, ch. 6, § 6___ 46

1873, p. 66____________________________49, 128

City codes:

' Jackson, 1938, § 546______ _ .7__________ 56

Meridian, 1962, § 17-97_____ ___________ 56

Natchez, 1954, § 5.6____________________ 56

Montana Key. Code, 1962, § 64-211______________ 31

Nebraska Rev. Stat., 1954, § 20-101---------------------- 31

New Hampshire Rev. Stat. (1963 Supp.) § 354.1------ 31

New Jersey Stat., 1960, § 10:1-2--------------------------- 31

New Mexico Stat. (1963 Supp.) § 99-8-3---------------- 31

New York:

Laws, 1873, p. 303--------------------------------------- 130

Stat., IX, pp. 583-584— ----------- 76

Civ. R., §40___________________- — ---------- 31

North Carolina city codes:

Asheville, 1945:

§2-5-109_______ 56

§ 2-7-120_____________________________ 56

§ 3-23-636__________—_________________ 56

Charlotte, 1961:

§ 11-11-2 (b)J__________________________ 56

§ 13—13—11____________________________ 56

§ 13-13-15 (a)__________________________ 56

XIV

North Dakota Code (1963 Supp.) § 12-22-30_______ 31

Ohio Rev. Code, 1954, § 2901.35__________________ 31

Oregon Rev. Stat., 1961, § 30.670_________________ 31

Pennsylvania Stat., 1963, § 18-4654_______________ 31

Rhode Island Gen. Laws, 1957, § 11-24-1--------------- 31

South Carolina:

Constitutions:

1895:

Art. I l l , §33_______________________ 59

Art. XI, §8________________________ 50

Codes:

1882, §§ 1369, 2601-2609________________ 51

1962:

§20-7______________________________59,60

§§ 35-51-35-54_____________________ 103

§§ 35-130-35-136___________________ 103

§ 35-142___________________________ 103

§ 40-452__________________________ 63

§ 58-551____________________________60,61

§§ 58-714—58-720__________________ 60

§§ 58-1331—58-1340_-_____ 60

§ 58-1333__________________________ 36

§§ 58-1491—58-1496________________ 60

Statutes at large :

7 Stat. 461, §§ 2, 7 (1822)____________ 44

7 Stat. 463 (1823)_____. . . ________ _ 44

14 Stat. 179 (1869)_________________ ' 49

14 Stat. 386 (1870)__________________ 49

Acts:

1865:

No. 4730__________________________ 47

No. 4731:

§ I ____________________________ 47

§ IV__________________________ 47

§ X ----------------------------------------- 47

§ XIV_________________________ 47

§ X X II________________________ 47

§ XXIV_______________________ 47

§ XXVII______________________ 47

State constitutions and statutes—Continued page

XV

State constitutions and statutes—Continued

South Carolina—Continued

Acts—Continued

1865—Continued

No. 4732:

§ V---------- 47

§ V II_________________________ 47

§ X X _________________________ 47

§ X X IX _______________________ 47

§ X X X I_______________________ 47

§ X X X II______________________ 47

§ X X X III_____________________ 47

No. 4733:

§§ XV-LXXI__________________ 47

§XXXV______ - ______________ 47

§ LX X II______________________ 48

§ LX X XI-X CIX_______________ 48

1886-1887, No. 288, p. 549----------------------- 51

1888-1889, No. 219, p. 362----------------------- 51

1896, No. 63, p. 171-------- 50

1898, No. 483, pp. 777-778---------------------- 53

1900:

No. 246, pp. 443-444------------------------ 54

No. 262, pp. 457-459------------------------ 53, 54

1904, No. 249, p. 438------------------------------ 53

1905, No. 477, p. 954____________________ 53

1906:

No. 52, p. 76_______________________ 55

No. 86, pp. 133-137________________ 50, 54

1911, No. 110, p. 169------------------------------ 54

1917, p. 48 (S.C. Code (1962), § 5-19)-------- 55

1918, No. 398, pp. 729, 731---------------------- 54

1924, p. 895 (S.C. Code (1962), § 5-503).— 55

1934, No. 893, p. 1536----------------------------- 54

XVI

State constitutions and statutes—Continued

South Carolina—Continued

City codes and ordinances:

Columbia ordinances: Pag®

§2-73_________ 103

§§ 12-27—12-33____________________ 103

Greenville City Code, 1953:

. §8-1______________________________ 55

§ 16-35____________________________ 55

§31-1_____________________________ 55

§ 31-2_____________________________ 55

§31-4_____________________________ 55

§31-5______________________________ 55,63

§ 31-6____________________________ 55

§ 31-7_____________________________ 55

§31-8___ 55

§ 31-9____________________________ 55

§ 31-10___________________________ 55

§ 31—12____________________________ 55,63

§ 37-30____________________________ 55

Greenwood City Code, 1952, ch. 24________ 56

Spartanburg:

City Codes:

1949, § 23-51___________________ 63

1958:

§ 28-45____________________ 57

§28-76 (a)_________________ 57

Plumbing Code, 1961, § 921.1__ 57

South Dakota Laws, 1963, ch, 58_________________ 31

Tennessee:

Code Ann., § 62-710___________ 61

Laws 1868-1869, p. 14_____________________ 49

Vermont Stat., 1958, § 1451___________________ 31

Virginia:

City codes:

“ Danville, 1962, § 18-13___________________ 53,63

Norfolk, 1950, § 9-30___________________ 56

Washington Rev. Code, 1962, § 49.60.215__________ 31

Wisconsin Stat., 1958, § 942.04----------------------------- 31

Wyoming Stat. (1963 Supp.) § 6-83.1--------------------------- 31

Congressional material:

Cong. Globe, 2d Cong., 2d Sess., p. 381____________ 132

Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 839_________ 124

P. 1156-1157______________________________ 124

P. 2989___________________________________ 115

XVII

Congressional material—Continued Page

Cong. Globe, 38th Cong., 2d Sess., p. I l l —.............. 116

P. 177____________________________________ 115

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 39----------— 114, 120

P. 41________________________________ ___ 119, 138

P .4 2 _______________________ — _________ 120

P .4 3 ___________________________ - _______ 120

Pp. 96, 342, 1157, 1270-1271___- _____________ 138

P. I l l __________________________________ 116, 120

P. 154____________________________________ 115

Pp. 113, 363, 499, 598, 623, 628, 936, 1268, 1270-

1271, 2940, App. 158_________ - __________ 138

P. 318____________________________________ 121

P. 322________ ___ ___________ . . . ______ 114, 121

P .341-----------------— ,-------—----------------- 117

Pp. 343, 477, 541, 606, 1122, 1157-_______ — 138

P.474-476_______________- - - - - ______ _ 117,121

Pp. 474-476, 503, 1124, 1159__________ - ____ 114

Pp. 476, 599, 606, 1117, 1151, 1154, 1159, 1162,

1263________________ 115

Pp. 476-477, 1117, 1122, 1291____________ _ — 116

Pp. 570-571_______________________________ 116

P. 589____________________________ 116

P.630____________________________________ 116

App. 67______________________ ____ -----__ 116

P.477_________________- _______ — 121

P. 500, 1120, 1268, 1290-1293________________ 115

P. 503_____________________________ 114

P. 516-517________________________________ 122

P. 541____________________________________ 125

Pp. 601-602, App. 70_______________________- 138

P.684____________________ 118

P.916______ ,______ _________________ _____ 125

P.936-943________________________ - - - - - - 125,126

P. 943_____________________ 113

P. 1117, 1159______________________________ 113

P. 1124___________________________________ 113

P. 1290-1293________________ - _________ ___ 115

P. 1366__________________________ 121

P. 1679______________________- ____________ 126

P. 1832____________- _______ -____ — ------- 136

P. 2459_________________________________ 118, 141

719- 946— 64-----------2

XVIII

Congressional material—Continued

Congressional Globe—Continued pag0

Pp. 2459, 2462, 2465, 2467, 2538_________ 118

Pp. 2461, 2511, 2961________________________ 118

Pp. 2465, 2542_______________________ 142

Pp. 2498, 2503, 2530, 2531, 2459, 2510, 2539,

2961, 3034___________ 118

P. 2765_________ 141

P. 2766___________________________________ 118

P. 2897___________________________________ 118

P. 3037___________________________________ 115

App. 68-71________________ 125

App. 183__________________________________ 126

Cong. Globe, 42d Cong., 2d Sess., p. 244___________ 131

Pp. 381, 381-383_____________________ 124, 131, 142

Pp. 382-383_______________________________ 132

P. 1582___________________________________ 133

2 Cong. Rec. 11, 340, App. 361, 3452, 4081-4082, 4116,

4171, 4176_____________________ 124, 132, 134, 135, 142

3 Cong. Rec. 1005, 1006, 1011, 1870, 2013________ 133, 135

Hearing before the Senate Committee on Commerce

on S. 1732, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 324-326____ 28

House Bill No. 86, approved May 16, 1963 (Florida)__ 98

House Rep. No. 30, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., Part II,

pp. 4, 61, 126, 177___________________________ 48, 122

Journal of Joint Committee on Reconstruction, S. Doc.

No. 711, 63d Cong., 3d Sess., p. 17______________ 139

S. 9, 39th Cong., 1st Sess________________________ 114

S. 60, 39th Cong., 1st Sess_______________________ 114

S. 61, 39th Cong., 1st Sess_____________________ 114, 121

Senate Exec. Document No. 2, 39th Cong., 1st Sess.,

pp. 516-517__________________________________ 122

Miscellaneous:

Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (1954)_______________ 38

Annotation, 46 A.L.R. 2d 1287„_________________ 59

5 Bacon, Abridgement of the Law— Inns and Inn

keepers (1852)__________________________________ 94

Baltimore American, April 30, 1870, p. 1, col. 6, p. 2,

col. 1_________________________________________ 51

Baltimore American, November 11, 1871, p. 2, col. 2,

November 14, 1871, p. 2, col. 1, p. 4, col. 3______ 51

XIX

Baltimore Sun, November 13, 1871, p. 4, col. 2_____ 51

Biekel, The Original Understanding and the Segregation

Decision, 69 Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1955)___ 113, 137, 139, 141

Bilbo, Take Your Choice, Segregation or Mongrelization

(1947)_____________________________________ 38

3 Blackstone, Commentaries, (Lewis ed., 1897), p. 166_ 30, 94

Bradley, J., unpublished draft of letter by, March 12,

1871, on file, The New Jersey Historical Society,

Newark, New Jersey-___________________________ 76

10 Broek, The Antislavery Origins oj the Fourteenth

Amendment (1951)____________________________ 113

Burdick, The Origin of the Peculiar Duties oj Public

Service Companies, 11 Col. L. Rev. (1911) 514____ 30

Cable, “The Freedman’s Case in Equity” (1884) and

“The Silent South” (1885)_________________ 129

Cable, The Negro Question (Turner ed., 1958)_______ 129

Cash, The Mind oj the South (1941)_______________ 38, 40

Cleghorn, “The Segs,” Esquire (January 1964)_______ 38

Collins, The Fourteenth Amendment and the States

(1912)_______________________________ - - - - - - - 113

Collins, Whither Solid South (1947)__________________ 38

Commission on Inter-racial Problems and Relations

to the Governor and General Assembly, Annual Re

port 1957__________________________- ________ 28

•Conard, The Privilege oj Forcibly Ejecting an Amuse

ment Patron, 90 U. of Pa. L. Rev. (1942)_________ 30

Dollard, Caste and Class in a Southern Town (1957

ed.)___________ __________________________ '__ 38

Doyle, The Etiquette oj Race Relations in the South

(1937)_______________________________________ 40,42

Dummond, Antislavery (1961)____________________ 37

Flack, The Adoption oj the Fourteenth Amendment

(1908)_____________________- ______ 113,118,127,132

1 Fleming, Documentary History oj Reconstruction

(1906)__________ 45

Frank and Munro, The Original Understanding oj

“Equal Protection oj the Laws,” 50 Col. L. Rev.

Miscellaneous—Continued Page

Frazier, The Negro in the United States (1957)___ 36, 37, 38

XX

George, The Biology of the Race Problem (1962)_____ 38

Graham, Our “Declaratory” Fourteenth Amendment,

7 Stan. L. Rev. (1954) 3_______________ 113

Greenburg, Race Relations and American Law (1959) _ 62

Hand, L., The Speech of Justice, 29 Harv. L. Rev.

(1916) 617_________ _____________ . . . _________ 144

Handlin, Race and Nationality in American Life (1957). 38

Harris, The Quest for Equality (1960)_____ 65, 113, 118, 142

Henkin, Shelley v. Kraemer, Notes for a Revised

Opinion, 110 U. Pa. L. Rev. (1962) 473__________ 84, 85

Horowitz, The Misleading Search for “State Action”

Under the Fourteenth Amendment, 30 So. Cal. L.

Rev. (1957) 208________________________________ 84

II Hurd, The Law of Freedom and Bondage in the

United States (1862)______________ _________ 37, 44, 45

James, The Framing of the Fourteenth Amendment

(1956)_____________________ 113

Johnson, C., Patterns of Segregation (1943)_________ 35

Kendrick, Journal of the Joint Committee on Recon

struction (1914)______________________________ 113

Konvitz & Leskes, A Century of Civil Rights (1961) _ 38

Lewinson, Race, Class, and Party (1932)___________ 38

Lewis, Prof. Thomas P., The Role of Law in Regulating

Discrimination in Places of Public Accommodation

(p. 14)____________________ _________ ____.___ 33

Lomax, The Negro Revolt (1962)____________ 38

Mangum, The Legal Status of the Negro (1940)______ 62

Manual of Practice for Florida’s Food and Drink

Services Based on the Rules and Regulations of the

Florida State Board of Health and State Hotel and

Restaurant Commission (July 1960)________ 2, 3, 97, 100

McPherson, Political History of the United States

During the Period of Reconstruction (1871)_______ 45

Mechem, Outlines of the Law of Agency (4th ed.) § 382_ 102

Murray, States Laws on Race and Color (1950)______ 62

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (Rev. ed., 1962)____38, 40

Miscellaneous—Continued page

XXI

National Cyclopedia of American Biography, V (1907). _ 129

X X X V III-■______________________ - - - - - - - 129

Nye, Fettered Freedom (1949)_________ ___________ 113

1 Op. Atty Gen. 659__________________________ 44

Page, The Negro: The Southerner’s Problem (1904)___ 38

Peters, Civil Rights and State Action, 3 Notre Dame

Lawyer 303_________________________- _______ 65

Pollitt, Dime Store Demonstrations: Events and Legal

Problems of First Sixty Days, 1960 Duke L.J. 315- _ 25, 35

Prosser, Toils:

(1941 ed.) 194, 323-325, 330, 723_________ 90, 92, 101

(1955 ed.) 188-189, 430— _________________ 101, 102

Putnam, This is the Problem!, The Citizen (Citizens’

Councils of America, Nov. 1961--._______________ 38

4 R.R.L.R. 733______________ 63

Randall, The Civil War and Reconstruction (1937)___ 113

Restatement Torts, Secs. 321, 330(d), 364, 431,

551(2)----------------------- -------------- ------------- 32, 92, 101

Roche, Civil Liberty in the Age of Enterprise, 31 U. of

Chi. L. Rev. 103_____________________________ 65, 76

Rowland, Courts, Judgesand Lawyers of Mississippi,

1798-1935 (1935), pp. 48-49___________________ 129

Role of Law in Regulating Discrimination in Places of

Public Accommodation, The, Conference on “Dis

crimination of the Law”, November 22-23, 1963__ 33

Saenger, The Social Psychology of Prejudice (1953)__ 38

Shaw, Man and Superman (1916 ed.)______________ 37

Shufeldt, The Negro, A Menace to American Civilization

(1907)___________________________________ __ 38

Smith, L ., Killers of the Dream (1949)_____________ 40

Southern Regional Council, Inc., Civil Rights: Year-

End Summary (Dec. 31, 1963, mimeograph)______ 26

Southern Regional Council, Inc., The Student Protest

Movement: A Recapitulation (September 1961)____ 26

Southern Regional Council, Report, The Student

Protest Movement: Winter 1960 (April 4, 1960, rev.)- 25, 35

Southern Standard Building Code, 1957-1958;

§ 2002.1

Miscellaneous—Continued Page

57

XXII

Stephenson, Race Distinctions in American Law Saga

(1910)___________________________________ 30,76,77

Storey, Bailments, §§ 475, 476 (7th ed., 1863)______ 94

1 Street, Foundations oj Legal Inability (1906)______ 91

3 Stroud, Judicial Dictionary (1903), p. 2187_______ , 30

Swisher, Roger B. Taney (1936) p. 154____________ 44

Tindall, South Carolina Negroes 1877-1900________ _ 51

Tumin, Desegregation (1958)_____________________ 38

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Freedom to the Free

(1963)______________________________________ , 48

Van Alstyne and Karst, State Action, 14 Stan. L. Rev.

3 (1961)_____________________________________ 84

Warsoff, Equality and the Tm w (1938)______________ 113

Weyl, The Negro in American Civilization (1960)__ 36, 37, 44

Wheeler, Law oj Slavery (1837)___________________ 42

Williams, The Twilight of State Action, 41 Texas L. Rev.

347 (1963)___________________________________ 84

Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (1955)__ 27, 51

Woodson, The Negro in Our History (6 ed. 1932)____ 36

Woof ter, Southern Race Progress— The Wavering Color

Line (1957)__________________________________ 38

Wright, The Free Negro in Maryland (1921)________ 37

Wyman, The Law of the Public Callings as a Solution

of the Trust Problem, 17 Harv. L. Rev. 156 ( 1 9 0 3 ) 3 0

Miscellaneous—Continued

J t t the Supreme (Sfmtrt of the United s ta tes

October Term, 1963

No. 6

W illiam L. Griffin , et al., petitioners

v.

State of Maryland

No. 9

Charles F . B arr, et al., petitioners

v.

City of Columbia

No. 10

Simon B ouie, et al., petitioners

v.

City of Columbia

No. 12

Robert Mack B ell, et al., petitioners

v.

State of Maryland

No. 6 (f

J ames Russell R obinson, et al., appellants

v.

State of F lorida

ON W R IT S OF CERTIO RARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH

CAROLINA AND THE COURT OF APPEALS OF M ARYLAND AND

ON APPEAL FROM THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS

CURIAE

This brief is filed pursuant to the Court’s order of

November 18, 1963, inviting the Solicitor General,

pursuant to his suggestion, to file a brief expressing

(i)

2

the views of the United States upon “ the broader

constitutional issues which have been mooted” in

these cases.

We confine the brief to those issues, but believe it

appropriate to note two somewhat narrower grounds

specially applicable to Robinson v. Florida, No. 60,

which came to our attention in preparing to argue the

broader issues.

1. At the time petitioners Robinson et al. were

arrested, there was in effect a regulation of the

Florida Board of Health applicable to restaurants

(Florida State Sanitary Code, Chapter VII, Section

6), which provided:1

Toilet and lavatory rooms must be provided for

each sex and in case of public toilets or where

colored persons are employed or accommodated

separate rooms must be provided for their use.

Each toilet room shall be plainly marked, viz:

“White Women,” “Colored Men,” “White

Men,” “ Colored Women.”

1A Manual of Practice for Florida's Food and Brink Serv

ices based on the Rules and Regulations of the Florida State

Board of Health and State Hotel and Restaurant Commission,

published in July 1960 (one month before petitioners were

arrested), prescribed (pp. 140-141) :

“4.6.7—Toilet and hand washing facilities

“ (a) Basic requirement—In every food and drink service

establishment adequate toilet and hand washing facilities shall

be available for employees and guests. Separate facilities shall

be provided for each sex and for each race whether employed

or served in the establishment. Toilet rooms shall not open

directly into a room in v/hich food or drink is prepared, stored

or served.”

The substance of the regulation quoted in the text was

reissued on June 26, 1962, and is now part of Florida Admin

istrative Code, Chapter 170C, Section 8.06. See pp. 99-100,

infra.

3

While the regulation does not require segregation

in the parts of the restaurant where customers are

eating, the regulation not only gives official support

to the principle of racial segregation but puts the

proprietor who desires to serve both races indiscrimin

ately to the financial burden of providing duplicate

toilets and lavatories.2 Thus, the regulation would

seem to impose sufficient State pressure to bring the

case within Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U.S. 244, and

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267.

2. The views expressed by Mr. Justice Stewart in

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715, 726, would also seem to require reversal in the

Robinson ease.

Chapter 509 of Florida Statutes Annotated sets

forth a comprehensive code of regulation for public

lodging and public food service establishments. Sec

tion 509.092, however, provides—

Public lodging and public food service estab

lishments are declared to be private enterprises

and the owner or manager of public lodging

and public food service establishments shall

have the right to refuse accommodations or

service to any person who is objectionable or

undesirable to said owner or manager.

2 A restaurant serving fewer than 100 people at one time

would be required to have one toilet and one lavatory for

women, one toilet, one urinal and one lavatory for men, pro

vided that no Negroes were accommodated. I f Negroes were

accommodated, the facilities would have to be duplicated. See

A Manual of Practice for Florida's Food and Drink Services,

supra, p. 141.

4

It is undisputed that petitioners were refused serv

ice only because they were either Negroes or in the

company of Negroes (R. 19-20, 29).

Section 509.141, the statute under which petitioners

were convicted, authorizes the manager to eject any

person who, in his opinion, is a—

person whom it would be detrimental to such

* * * restaurant * * * for it any longer to

entertain.

•The managers invoked this section because they be

lieved that enforcing segregation accorded with the

wishes of a majority of the people of the county and

any contrary course would be detrimental to the

business.

The statute in Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority allowed a proprietor to refuse to se rv e -

persons whose reception or entertainment by

him would be offensive to the major part of his

customers * * *.

In Burton, Mr. Justice Stewart said—

There is no suggestion in the record that the

appellant as an individual was such a person.

The highest court of Delaware has thus con

strued this legislative enactment as authorizing

discriminatory classification based exclusively

on color. Such a law seems to me clearly viola

tive of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Here, as in Burton, there is no suggestion in the

record that any appellant as an individual was a per

son deemed detrimental to the business because per

sonally offensive to other customers. Whites were

automatically served and Negroes and groups contain

5

ing Negroes were automatically excluded. Here, as

in Burton, therefore, the highest court of the State

has construed its legislation as authorizing a discrimi

natory classification based exclusively upon color.3

Such a law is invalid equally with the Delaware legis

lation, and the convictions thereunder should be

reversed.4

We turn now to the broader issue.

QUESTION PRESENTED!

In four of these five cases petitioners peacefully

entered premises thrown open by the proprietor to the

general public for the service of food and refresh

ments; in the fifth, they entered an amusement park

offering entertainment to the public at large. In each

3 See also the statement of the trial court at R. 36. The in

stant case would seem even clearer than Burton, for the statute

was enacted in 1957 in a context of systematic segregation.

4 I t has been suggested that Mr. Justice Stewart’s opinion

in Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority should be read as

saying that there was no suggestion in the record that appel

lant’s race made him “offensive to the major part of [the res

taurant’s] customers.” Examination of the record makes it

plain that this cannot be the meaning. The case was decided on

cross motions for summary judgment. The third affirmative de

fense asserted the restaurant’s right as a private business to

refuse refreshment “to persons whose reception or entertain

ment would be offensive to the major part of its customers and

would injure its business,” and that the defendant “is there

fore not bound to serve the plaintiff in its restaurant.” Trans

cript of Record, p. 8, No. 164, October Term, 1960. On motion

for summary judgment, that allegation would be taken as true.

The nub of the matter, therefore, was that plaintiff was re

fused service not as an offensive individual but upon the ground

that a majority of the customers desired a racial classification.

The situation in the instant case is the same.

6

ease, although, otherwise acceptable, petitioners were

refused service and asked to leave on the ground that

they were Negroes or were in the company of Negroes.

This was done pursuant to the proprietor’s policy of

denying service to Negroes as a class, although he

rendered service to all other members of the public,

without discrimination, to the extent of his facilities.

In three of the cases Negroes were invited into the

premises to buy goods, and their patronage was sought

for all purposes except the service of food to be eaten

there in the presence of white patrons.

In each instance petitioners refused to leave the

premises when requested. They were arrested by

the local police, prosecuted and subsequently convicted

of criminal trespass or an equivalent crime. The

relevant State laws afforded Negroes and non-Negroes

technical equality in the limited sense that they gave

no member of the public an enforeible right to enter

tainment or service in the establishments involved.48

The question presented is whether the convictions

are invalid under the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, when it appears (as we shall

argue)—

(1) that the convictions gave legal effect to a com

munity-wide practice under which non-Negroes are

automatically served in establishments of public ac

commodation while Negroes are automatically segre

4a The briefs previously filed in these cases present full state

ments of the facts and proceedings below. We have epitomized

the essential elements to the extent necessary to present the

broad constitutional issue.

7

gated or excluded in order to stigmatize them as

members of an inferior race, and

(2) that the practice, is an integral paid of the

fabric of a caste system woven of threads of both

State and private action.

ARGUMENT

INTRODUCTORY

For nearly a century, a nation dedicated to the

faith that all men are created equal nonetheless tole

rated Negro slavery and still more widely espoused,

in laws and public institutions, as well as private

life, the thesis that the Negro is a servile race destined

to be set apart as an inferior caste neither sharing nor

deserving equal rights and opportunities with other

men. A great war resulted. At the end the Thirteenth,

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments not only

abolished human bondage but purported to eradicate

the imposed public disabilities based upon the false

thesis that the Negro is an inferior caste. Before

their government, the Amendments taught, in the

eyes of the law, all men—men of all races-—are cre

ated equal.

Slavery was in fact abolished. The twin promise of

civil equality failed of immediate performance. State

laws were enacted, customs were promoted by public

and private action, institutions and ways of life were

established, all upon the pervasive thesis that, although

human bondage was forbidden, Negroes were still an

inferior caste to be set apart, neither sharing nor

entitled to equality with other men.

8

One of the pivotal points in the State-promoted

system of public segregation and subjection became

separation in all places of public transportation, en

tertainment or accommodation.5 There the brand of

inferiority burns the deepest; there the wrong is the

greatest; for there no element of private association,

personal choice or business judgment enters the de

cision—only the willingness to join in the imposition

of the public stigma of membership in an inferior

caste. There the Negro asks most insistently whether

we mean our declarations and constitutional recitals

of human equality or are content to live by, although

we do not profess, the theories of a master race.

That is the question petitioners raised when they

entered and sought service in these places of public

accommodation. They raised the question in various

forms. They raised a moral, and therefore in a sense

5 Throughout this brief we frequently use the term “places of

public accommodation” as a convenient shorthand description

of the soda fountains or lunch counters, restaurants and amuse

ment park involved in these cases. The phrase seems apt to

describe all establishments which throw their premises open

to the public at large (except for any racial restrictions), which

invite the patronage of the general public without selection

either in the invitation or rendition of service, and which

furnish lodging, food or drink, entertainment, amusement or

similar services. The meaning might extend far enough to

include gasoline service stations which “feed” the automobiles,

just as the adjacent restaurant feeds the traveler. The exact

limits are unimportant for it is the characteristics of the soda

fountains or lunch counters, restaurants and amusement park

described later in this brief that are legally significant and the

expression is merely a shorthand way of describing them. If

other establishments were shown to have the same characteris

tics, the same legal consequences would follow.

9

a persona] question, as they presented it to the pro

prietors of the establishments in which they were

arrested. The question became legislative as the dem

onstrations pressed the Congress and the States to

consider whether to require establishments holding

themselves out to the public to serve all members of

the public without regard to race. It became a ques

tion for government, also, when the managers of the

establishments called upon State authority to support

a right to evict petitioners and thus join in maintain

ing the system of stigmatizing Negroes an inferior

caste. When the State intervened, a constitutional

issue was raised—how far and in what circumstances

does the Fourteenth Amendment permit a State to

support the system of public segregation of Negroes

for the purpose of stigmatizing them as an inferior

caste.

Only the last question is here. It is manifestly dif

ferent from both the moral question posed for the

individual and the policy questions presented to Con

gress and State authorities, but it is nonetheless re

lated to the ideal of civil equality. While the Four

teenth Amendment does not lay upon individuals and

non-governmental institutions the standards of con

duct applicable to the States and does not compel a

State to exercise all its regulatory power to abolish all

forms of private (i.e., non-governmental) discrimina

tion, the Amendment does reach State-sponsored in

equality in every form. In the Civil Bights Cases,

1 0

109 U.S. 3, 11, the Court drew the fundamental dis

tinction :

It is State action of a particular character

that is prohibited. Individual invasion of indi

vidual rights is not the subject-matter of the

amendment. * * *

The distinction is deeply imbedded not only

in our fundamental law but in our national

life. It is essential to a free, pluralistic so

ciety. It is a product of our moral philosophy,

which values freedom because it calls upon man to

exercise his noblest quality—the power of choice be

tween good and evil. Freedom, in this sense, is free

dom to be foolish as well as wise, to be wrong as

well as right. While the State may sometimes limit

the choice, especially in the regulation of business

conduct, there is room for legislative judgment.

Nothing in the Constitution prevents a State which

has always scrupulously stayed its hand, from con

tinuing to prefer the course of private self-deter

mination, at least for those who have not opened

their premises to the public and perhaps even for those

whose businesses are affected with a public interest.

It would be equally false to ideals secured by the

Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments,

however, to permit a State to use the cloak of private

choice to hide affirmative State support for a caste

system heavily infused with governmental action.

We unqualifiedly accept the fundamental distinction

laid down in the Civil Bights Cases. Moreover, in

applying it, we take for granted the proposition that

the mere fact of State intervention through the courts

11

or other public authority in order to provide sanctions

for a private decision is not enough to implicate the

State for the purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In a civilized community, where legal remedies and

sovereign authority have been substituted for private

force, private choice in the use of property or busi

ness or social relations often depends upon the sup

port of sovereign sanctions. Where the only State

involvement is color-blind support for every property-

owner’s exercise of the normal right to choose his

business visitors or social guests, proof that the partic

ular property-owner was motivated by racial or reli

gious prejudice is not enough to convict the State of

denying equal protection of the laws.

But that is not this case. We deal here not with

individual action but with a community-wide, public

custom of denying Negroes the opportunity of break

ing bread with their fellow men in public places in

order to subject them to a stigma of inferiority as

an integral part of the fabric of a caste system woven

of threads of both State and private action. The re

fusal to allow an individual to eat at a lunch counter

generally open to all orderly members of the public,

when viewed in isolation, can be fairly described in

legal terms as a businessman’s exercise of the right

to select his customers, or as the property owner’s ex

ercise of the right to choose whom he will permit

upon his premises. Depending upon his motive, the

manager’s act may be petty, vindictive, immoral, a

harsh business judgment, or even justifiable; but in

the absence of statute his right is absolute. But his

tory and an appreciation of current institutions

719- 946— 64-------------3

12

(whose meaning is partly a product of history) show

that racial segregation in places of public accommoda

tion cannot be viewed as merely a series of isolated

private decisions concerning the use of property or

choice of customers, or even as a widespread private

custom unrelated to governmental action. The inci

dents are not separable. The custom is infused with

official action both in its origins and implementation.

The legal concepts applicable to isolated incidents are

not more adequate to capture the truth of racial segre

gation in places of public accommodation than chemi

cal formulas for body content are sufficient to describe

mankind. By way of illustration, Hitler’s pogroms

were not mere instances of assault, battery and mali

cious destruction of property.

To break the institution into its components even

for the purposes of analysis loses some of the reality,

but in our argument we emphasize, first, that the

essence of the practice of racial segregation in places

of public accommodation is not the management of

property or the selection of customers but the stig

matization of the Negro as an untouchable member

of an inferior caste. Its only function is to preserve,

despite the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments, the essence of the earlier disabilities

associated with slavery but extended more widely

through the Nation. Segregation in places of public

accommodation does not involve the management of

property or selection of customers in any true sense.

These are public places, made so by the proprietors’

voluntarily inviting the public at large to use them.

Between proprietor and customer there is only the

13

most casual and. evanescent of all business relation

ships. Any orderly person is served, always and

automatically, except those branded as members of an

inferior race. There is none of the continuity or

selectivity that enters into employment; and none of

the personal contact or need for mutual trust, con

fidence and compatibility that characterizes the doctor-

patient and lawyer-client relationships. The virtual

irrelevance of the legal concepts of private property

is vividly demonstrated by the practice of many de

partment stores. They solicit the patronage of Ne

groes, invite them onto the property and into the

store, make sales in other departments—some even

furnish food to eat away from the counter—but then

they deny the Negro the privilege of breaking bread

with other men. Manifestly, it is the stigma—the

brand of inferiority—that is important, not presence

on the premises or the character of customers.

Second, we show that the practice of stigmatizing

Negroes as an inferior caste by refusing to serve them

in places of public accommodation together with their

fellow men is a product of State action in the nar

rowest sense, although not currently required by law,

because it is an important and inseparable part of a

system of segregation established by a combination

of State and private action. When the Thirteenth,

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments outlawed

slavery and sought also to eradicate the public disa

bilities relegating Negroes to the status of an inferior

caste, respondents and some sister States were unwill

ing to eliminate all vestiges of the caste system from

their jurisprudence, official policies and public insti

14

tutions and leave the development of business, pro

fessional and social relations to private choice. State

statutes and municipal ordinances, on a wide scale,

required segregation in places of public accommoda

tion, upon common carriers, and in places of public

entertainment. State laws provided for segregation

in related areas such as schools, court houses and

public institutions. State policies expressed, in count

less other ways, the notion that Negroes should be

treated as an inferior caste. The community-wide

fabric of segregation thus was filled with the threads

of law and government policy woven by government

through the warp of custom laid down by private

prejudice. The system is all of a piece. Segregation

in places of public accommodation cannot be severed

and appraised in isolation. One cannot tell what

would happen if the threads of State law and State

policy were pulled from the cloth, save that mani

festly it would be changed.

After developing these two points in the hope of

clarifying the true nature of the institution with

which the cases are concerned, we return to the legal

question—whether a State which has fostered the

practice of racial segregation in places of public

accommodation in order to preserve the stigma upon

the Negro as an inferior caste, contrary to the promise

of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend

ments, may now, consistently with the requirements

of the Fourteenth Amendment, use the sovereign au

thority of its police and courts to sanction the eviction

of Negroes, pursuant to the practice, as an exercise of

private choice.

15

It is a settled principle that a State cannot exeul- j

pate itself merely by showing that the racial segrega- j

tion or some other invasion of fundamental interests

was contingent upon the decision of private individ

uals. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1; Pennsylvania v.

Board of Trusts, 353 U.S. 230; Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715; Lombard v. Louisi

ana, 373 U.S. 267; Railway Employees’ Dept. v. Han

son, 351 U.S. 225. This is not to retract our previous y

acknowledgement that neither recognition of a right

of private choice in a business subject to public regu

lation nor the use of State power to safeguard the

choice once made is automatically sufficient to impli

cate the State for the purposes of the Fourteenth

Amendment. It is to assert, in a complex, civilized

community where public and private action are inter

woven and interdependent, that the determination of a

State’s responsibility under the Fourteenth Amend

ment depends upon a judgment upon the size and im

portance of the elements of State involvement in rela

tion to the elements of private action, both measured

from the standpoint of the fundamental aims of the

constitutional guarantees.

The framers of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and F if

teenth Amendments were not content merely to forbid

human bondage. They were equally determined to re

move the widespread public disabilities, associated

with slavery, that branded the Negro an inferior caste

excluded from the promise that in America all men

are created equal. This is the heart of the guarantees

of the privileges and immunities of citizens, of equal

voting rights, and of equal protection of the laws.

16

The Fourteenth Amendment, it must be emphasized

required major changes in State laws: the old slave

codes were to be repealed; civil disabilities in owning-

property, in contracting and in the laws of inheritance

were to be eradicated; there were to be no State barri

ers to business opportunities and the professions; nor

were the States left free passively to watch Negroes

suffer individual wrongs at the hands of private per

sons in situations in which the State would intervene

to protect non-Negroes.

On the other hand, the Amendments left most social

and business associations to private choice. Where

the law did not compel social intercourse, business as

sociations and other private relationships among

whites, the Amendment did not require them between

whites and Negroes. Whether a Negro won equality

and acceptance in the private world outside the sphere

of government once freed from the public stigma of

civil disabilities would depend upon his own capacities

and efforts, hampered perhaps by personal prejudices

but freed from the caste system.

In historical terms it can hardly be denied that any

State intervention in support of the preservation of

the caste system in an everyday element of public life

defeats the promise of the Amendments. In stricter

legal terminology, the elements of State “ involve

ment” in these cases are sufficient, we submit, to carry

State “ responsibility” for the constitutional injustice.

The State is involved because its police intervened,

its officials prosecuted the petitioners, and its courts

convicted and sentenced them as a result of racial dis

17

crimination. The discrimination became operative

through the State’s action. The State cannot close

its eyes to what all other men see.

The State is further involved because the discrimi

nation occurred in public places, voluntarily thrown

open by the proprietors to the community at large.

It occurred in a segment of public life in which the

rights and duties—the relationships between the pro

prietor and the invited public—have always been a

special concern of the legal system. In each of the re

spondent States, but especially in Florida, the rela

tionship between these places of public accommodation

and the general public is so closely supervised as to

involve the State in all its aspects.

The States are involved through their support of

the system of segregation. For both the Negro and

the white supremacists, discrimination in places of

public accommodation is a pivotal point in the caste

system. The respondents and neighboring States

commanded segregation for many years on a broad

front. Between State policy and the prejudices and

customs of the dominant portions of the community

there was a symbiotic relation. The prejudices and

customs gave rise to State action. Legislation and

executive action confirmed and strengthened the

prejudices, and also prevented individual variations

from the solid front. State involvement under such

conditions is too clear for argument, even though

segregation might be the proprietor’s choice in the

absence of legislation. Cf. Peterson v. Greenville, 373

U.S. 244.

1 8

State responsibility does not end with the bare re

peal of laws commanding segregation in places of

public accommodation. The very history of the caste

system belies the claim of legal innocence when the

State, in these and similar cases, intervenes to sup

port its central stigma. The State is responsible for

the momentum its action has generated. The law is

filled with instances of liability for the consequences

of negligent or wrongful acts carried through a chain

of cause and effect until the connection between the

wrong and the consequences has become too attenu

ated to be a substantial factor in the harm. Until

time and events have attenuated the connection, the

respondents continue to bear responsibility for the

conditions, which they shared in creating, that result

in branding Negroes an inferior caste. They have

not wiped the slate clean.

We recognize that treating the discrimination as

a consequence of State action for the purposes of im

posing a measure of State responsibility will, to a

corresponding extent, lessen the opportunities and

protection for private choice. Decision here requires

striking a balance with liberty and equality in oppos

ing scales. The “liberty” asserted is hardly conse

quential. These are all business premises thrown

open to the public. The proprietors have voluntarily

foregone virtually all power of choice concerning the

customers they serve. There is no element of per

sonal selection or personal judgment. Non-Negroes

are served automatically; Negroes are automatical^

19

segregated or excluded. With rare exceptions there

is no other basis of choice.

There may be instances where the racial choice is

purely private in the sense that the proprietor would

make it even if the States had been truly neutral

and no community system of segregation had been

preserved. While our reasoning would sweep them

under the one conclusion until the caste system is

eliminated from public places, there is no unfair

ness in this conclusion. When the proprietor of a

place of public accommodation discriminates against

Negroes in a community which practices segregation,

he knows that he is joining in the enforcement of a

caste system and his acts take on the color of the

community practice and suffer the common disability

resulting from the community wrong. “ [T]hey are

bound together as the parts of a single plan. The plan

may make the parts unlawful.” Sivift & Co. v.

United States, 196 U.S. 375, 396; Terry v. Adams,

345 U.S. 461, 470, 476 (Mr. Justice Frankfurter

concurring). The risk that some proprietors may

lose State protection for an arbitrary choice not

influenced by the State’s previous conduct is not

great enough to permit the continuance of support

for the caste system, which is a product of State

involvement. Cf. Texas & N.O.R. Go. v. Brother

hood of Railway & S.S. Clerks, 281 U.S. 548; Na

tional Labor Relations Board v. Southern Bell Co.,

319 U.S. 50.

These problems, moreover, lie in an area where

there is little basis for the plea of private rights.

The proprietors of places of public accommodation

2 0

open their property and business to public use.

While the dedication cannot supply affirmative ele

ments of State involvement, it is relevant in weigh

ing the significance of those elements for the pur

poses of the Fourteenth Amendment. “ The more an

owner, for his advantage, opens up his property for

use by the public in general, the more do his rights

become circumscribed by the statutory and consti

tutional rights of those who use it.” Marsh v.

Alabama, 326 U.S. 501, 506.

The choice of affirmative remedies for State in

volvement in a system of segregation in places of

public accommodation rests with Congress imder Sec

tion 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. We do not

argue that .Negroes would have a direct action against

such an establishment to secure the services of food

or admission to entertainment. Our contention is

simply that a State which has contributed to this

evil custom may not constitutionally take steps to aid

its enforcement in public places. The same reasoning

that interdicts State action in the form of arrests and

criminal prosecution equally condemns State support

for the caste stigma in the recognition of a legal

privilege to use private force against the person.

Whoever first resorts to violence is guilty of a breach

of the peace, be he the Negro seeking to enter and

be served or the operator seeking to evict him. The