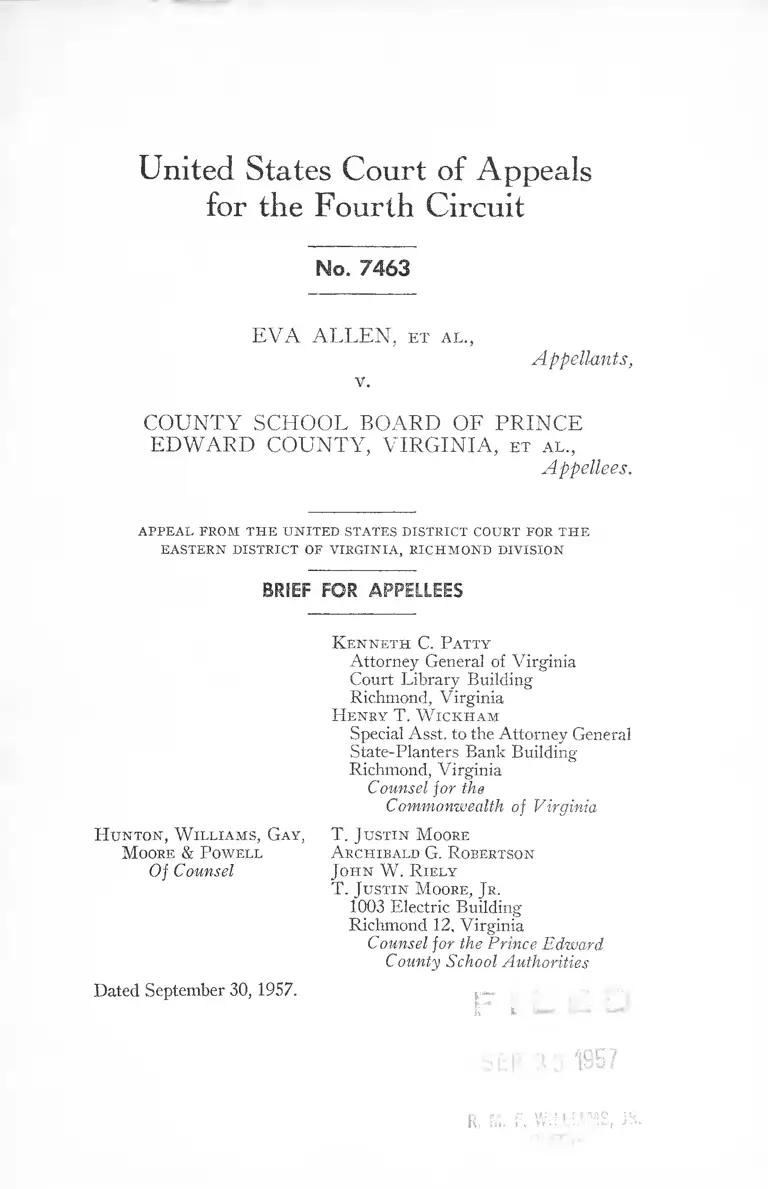

Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, VA Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

September 30, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Allen v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, VA Brief for Appellees, 1957. 1db1ed8b-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/de2551b5-7ff1-4acd-ba8a-3aee1b875809/allen-v-county-school-board-of-prince-edward-county-va-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

U nited S tates C ourt of A ppeals

for the F o u rth C ircuit

No. 7463

EVA ALLEN, e t a l .,

Appellants,

v.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE

EDWARD COUNTY, VIRGINIA, et a l .,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM T H E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR T H E

EASTERN DISTRICT OF V IRG IN IA , RICHM OND DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

H unton , W illiams, Gay,

Moore & P owell

Of Counsel

Dated September 30, 1957.

K enneth C. Patty

Attorney General of Virginia

Court Library Building

Richmond, Virginia

H enry T. W ickham

Special Asst, to the Attorney General

State-Planters Bank Building

Richmond, Virginia

Counsel for the

Commonwealth of Virginia

T. Justin Moore

A rchibald G. Robertson

John W . R iely

T. Justin Moore, Jr.

1003 Electric Building

Richmond 12, Virginia

Counsel for the Prince Edward

County School Authorities

F I L E D

R, M. F, WILLIAMS, JR-

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I. Introduction ............................................................................. 1

II. Statement o f the Ca s e ......................................................... 2

III. Question P resented ..................................................................... 5

IV. A rgument ........ 5

1. The Broad Discretion Vested in the District Court......... 5

2. The Exercise of Discretion ............................................... 9

V. Conclusion ......... 15

TABLE OF CASES

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 831 (C. A. 8, 1957) ........................... 13

Avery v. Wichita Falls Independent School District, 241 F. 2d 230

(C. A. 5, 1957), cert, denied, 353 U. S. 938 (1957) ......... ....... 15

Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 103 F.

S. 337 (E. D. Va. 1952), reversed, 347 U. S. 483 (1954), 349

U. S. 294 (1955), on mandate 142 F. S. 616 (E. D. Va. 1955)

2, 3, 6, 7

School Board of Charlottesville v. Allen, 240 F. 2d 59 (C. A. 4,

1956), cert, denied, 353 U. S. 910, 911 (1957) .......................

School Board of Newport News v. Atkins, .... ...... F. 2d .......... .

(C. A. 4, July 13, 1957) 13

I .

INTRODUCTION

In its final determination in the original school segrega

tion cases, of which this is one, the Supreme Court rejected

suggestions that it take forthright action to end segregation

in the public schools at once. It recognized that local con

ditions varied and it authorized local judges to vary the

remedies that they authorized on the basis of local condi

tions as they determined their relationship to the problem.

This was a broad and unfettered grant of discretion.

Here an able judge, familiar with local conditions, has

availed of that discretion to arrest the exercise of judicial

power for a temporary period because of impelling cultural

and civic factors.

The appellants pursue a relentless course. They are not,

of course, the named appellants; they are the organized

Negro N.A.A.C.P. lobby who appear as ever by the same

counsel. They seek to overturn not only the District Court

but the Supreme Court. They assert that the Supreme Court

was sociologically wrong in thinking that local factors are

important; they assert that immediate amalgamation is

always the best solution (Appellants’ Brief, pp. 14-5).

We rely here on the action of the Supreme Court, and

we rely in confidence, even if principles of sociology are to

replace principles of law in judicial determinations. We

accept the rule of discretion; we suggest that the only ques

tion at issue here is whether this Court can say that, in the

light of the school segregation decisions and the facts of

record here, it would be unreasonable for a reasonable judge

to hold that immediate action was not required. To state

that issue is to answer it; the District Court should there

fore be affirmed.

2

II.

STATEMENT OF TH E CASE

_ This case has never been to this Court before, but its

history is long. Although for unexplained reasons a new

plaintiff heads the list of appellants, it is still Davis v.

County School Board of Prince Edward County, 103 F. S.

337 (E. D. Va. 1952), reversed, 347 U. S. 483 (1954),

349 U. S. 294 (1955), The proceedings before that reversal

are too familiar to require restatement here.

After the second Supreme Court opinion, the case came

back to the three-judge District Court. A number of plead

ings were filed (P. A. 1-131)- On July 18, 1955, the three-

judge District Court entered a final decree as follows:

“That the defendants be, and they are hereby, re

strained and enjoined from refusing on account of race

or color to admit to any school under their supervision

any child qualified to enter such school, from and after

such time as the defendants may have made the neces

sary arrangements for admission of children to such

school on a non-discriminatory basis with all deliberate

speed as required by the decision of the Supreme Court

m this cause; but the court finds that it would not be

practicable, because of the adjustment and rearrange

ment required for the purpose, to place the Public

School System of Prince Edward County, Virginia,

upon a non-discriminatory basis before the commencing

of the regular school term in September 1955 as re

quested by the plaintiffs, and the court is of the opinion

that the refusal of the court to require such adjustment

and rearrangement to be made in time for the said

September 1955 school term is not inconsistent with the

public interest or with the decision of the SuDreme

Court----- ” (P. A. 15)

t \ The,inilV!? f - A. refer to the Appendix to the Brief for the Appel

lants ; the initials A. A. refer to the Appendix to this brief.

3

No appeal was taken from that final order but the matter

was retained on the docket. There the matter rested for

nine months. But the appellants were restive; on April 23,

1956, they filed a Motion for Further Relief (P. A. 15-24).

This motion is the origin of the present appeal. The plead

ing was a long one. It reviewed prior proceedings in the

case. It came next to a review of action considered by the

appellants to be relevant that had been taken by the Com

monwealth of Virginia over the preceding nine months. It

asserted that no additional time was necessary “in the public

interest” in order to effect desegregation (P. A. 23). It

accordingly requested immediate desegregation effective with

the opening of the schools in the fall of 1956 {ibid.).

The appellees answered this pleading by a showing of

facts (P. A. 24-7; A. A. 12-26). The pattern of State action

was reviewed, and developments in Prince Edward County

were detailed for the District Court. These facts must

appear irrelevant to the appellants, for they do not present

them to this Court along with their brief; they will, how

ever, be found in the appendix to this brief, and they consti

tute, of course, the factual basis for the decision on appeal

here.

The three-judge District Court met and dissolved itself

on its own motion since no issue of the constitutionality of

a statute remained.2 Before any decision by the single Dis

trict Judge, the appellees filed a further motion. In it, they

asserted that the appellants had failed to exhaust admin

istrative remedies provided by recent Virginia legislation

and to seek remedies available to them under the final order

then existing (P. A. 28). The case was then argued and

submitted.

2142 F. S. 616 (1956).

4

The opinion of the District Court is a very careful and

thorough one (P. A. 29-48). The Court first reviewed

prior proceedings in the case (P. A. 29-30) and then came

to the recent Virginia legislation. The conclusion reached

was that, on the record as it then was, the effect of those

statutes was not before the Court (P. A. 31-4).3 The Dis

trict Court then passed to the propriety of granting to the

appellants the relief that they so impetuously sought. The

breadth of discretion permitted by the Supreme Court in the

light of varying local conditions was made manifest (P. A.

35-8). The Court then reviewed conditions in Prince Ed

ward County and the problems presented for its schools

(P. A. 40-3). It was clear from the record that, regardless

of State statutes, the schools would be closed entirely if inte

gration were to be required. The effect on children and

teachers of abandonment of the public schools was weighed

(P. A. 44-5). The conclusion reached was that the dangers

of granting relief much outweighed the asserted losses of

the appellants. The allowance of additional time was held

“imperative” (P. A. 47). Accordingly, no action on the

Motion for Further Relief was taken, but the appellants

were given leave to renew it after a reasonable time (P. A.

47-8).

This opinion was handed down on January 23, 1957. An

order conforming to the opinion was entered on March 26,

1957 (P. A. 48), and this appeal followed.

3The appellants now seek half-heartedly to object to this conclusion

(Brief, pp. 17-18). But all of that is immaterial here. Those statutes

have already been before this Court and are now before both the Su

preme Court of Appeals of Virginia and the Supreme Court of the

United States.

5

III.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Only a single question is in fact presented by this case:

In the light of the broad range of judicial discretion

specifically granted to local courts by the Supreme

Court in school segregation matters, was it an abuse of

discretion on the part of the District Court in the light

of the facts shown of record here to refuse to order

immediate integration of the public schools of Prince

Edward County, Virginia?

Clearly the answer to this question should be in the nega

tive.

IV.

ARGUMENT

1.

The Broad Discretion Vested in the

District Court

The appellants in essence urge in this case that immediate

integration is the only course to be permitted in the public

schools of Prince Edward County, Virginia. This argument

seeks to overturn the explicit ruling of the Supreme Court

in the school segregation cases.

In its 1954 decision in this case, the Supreme Court

called for reargument on the question of relief. It posed

five possible solutions to be considered by it. They were:

(1) admit Negroes forthwith to the school of their choice;

(2) appoint a special master to hear evidence and recom

mend to the Supreme Court detailed decrees on how to

integrate;

6

(3) formulate specific decrees in the Supreme Court for

each case without the assistance of a special master;

(4) fix a time limit in which desegregation must be begun

and carried forward as recommended by the Attorney

General of the United States; or

(5) remand the cases to the District Courts to consider and

enter further decrees in the light of local conditions.

The Supreme Court refused to take hasty or generalized

action; it recognized that any single rule was impossible.

It chose the fifth alternative over the opposition of the

successful appellants there and of the United States. Its

reasons for doing so were made clear:

“Full implementation of these constitutional princi

ples may require solution of varied local school prob

lems. School authorities have the primary responsi

bilities for elucidating, assessing, and solving these

problems; courts will have to consider whether the

action of school authorities constitutes good faith im

plementation of the governing constitutional principles.

Because of their proximity to local conditions and the

possible need for further hearings, the courts which

originally heard these cases can best perform this judi

cial appraisal. Accordingly, we believe it appropriate

to remand the cases to those courts.” (349 U. S. at p.

299)

The Supreme Court was content to give only general

directions to the District Courts:

“In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the

courts will be guided by equitable principles. Tradi

tionally, equity has been characterized by a practical

flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a facility for

adjusting and reconciling public and private needs.

7

These cases call for the exercise of these traditional

attributes of equity power. At stake is the personal

interest of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools

as soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis. To

effectuate this interest may call for elimination of a

variety of obstacles in making the transition to school

systems operated in accordance with the constitutional

principles set forth in our May 17, 1954, decision.

Courts of equity may properly take into account the

public interest in the elimination of such obstacles in a

systematic and effective manner. But it should go with

out saying that the vitality of these constitutional princi

ples cannot be allowed to yield simply because of dis

agreement with them.” {Id. at p. 300)

The District Court here was struck by the care with which

the Supreme Court had acted. It referred to that Court’s

language as to the variety of local conditions and problems

and continued:

“Bearing in mind that the only legal issue in this

case pertains to a right guaranteed by the Constitution,

this language coupled with the action of the Court, takes

on significance which can hardly be over emphasized.

It is elementary law that one deprived of a right guar

anteed by the Constitution ordinarily is afforded im

mediate relief. Notwithstanding this fundamental prin

ciple, the Supreme Court in this case has seen fit to

specifically declare that while the plaintiffs are entitled

to the exercise of a constitutional right, in view of the

grave and perplexing problems involved, the exercise

of that right must be deferred. With that declaration

the Court used equally forceful language indicating that

it realizes that conditions vary in different localities.

Consequently, instead of simply declaring the right and

entering a mandate accordingly, it has seen fit in the

exercise of its equity powers to not only defer until a

later date the time when the right may be exercised,

8

but to clearly indicate that the time of exercising such

right may vary with conditions. A realization of the

effect of this action on the part of the Court is of su

preme importance to an understanding of the course to

be pursued by the Courts of first instance. At the risk

of being repetitious, I again recall that: Before laying

down those principles, the Court considered and rejected

the suggestion that negro children should be forthwith

admitted to schools of their choice; rejected the sug

gestion that it formulate detailed decrees; rejected the

suggestion that a special master be appointed by it to

hear evidence with a view to recommending specific

terms for such decrees and adopted the proposal that

the Court in the exercise of equity powers direct an

effective gradual adjustment under the order of the

Courts of first instance. Further, the Court considered

and rejected the suggestion that a specified rule of

procedure be established for the District Courts but

placed upon those Courts the responsibility of consider

ing, weighing and being guided by conditions found to

prevail in each of the several communities to be affected

by their decrees.” (P. A. 37-8)

The District Court then passed to a formulation of the

rule established by the Supreme Court. This was done with

great care as follows:

“Boiled down to its essence, in the Second Brown

Case the Court after pointing out that the local school

authorities have the primary responsibility of finding

a solution to the varied local problems, proceeded to

observe that the District Courts are to consider whether

the actions of the local authorities are in good faith;

and that by reason of their proximity to local condi

tions those Courts can best appraise the conduct of the

local authorities. It is then pointed out that in so

appraising, the Courts should be guided by the tradi

tionally flexible principles of equity for adjusting and

reconciling public and private needs. To be considered

9

is the personal interest of the plaintiffs, as well as the

public interest in the elimination of obstacles in a sys

tematic and effective manner. During this period the

Courts should retain jurisdiction of the cases. The

Court has here clearly and in unmistakable terms placed

upon the District Judges the responsibility of weighing

the various factors which prevail in the respective locali

ties affected. There is here a recognition of the obvious

fact that in one locality in which conditions permit, a

change may be effected almost immediately. In other

localities a specified period appropriate in each case

may be feasible and a definite time limit fixed accord

ingly. In yet other communities a greater time for com

pliance may be found necessary. It is clear that the

Court anticipated the application of a test of expediency

in such cases so that an orderly change may be accom

plished without causing a sudden disruption of the way

of life of the multitude of people affected.” (P. A.

38-9)

This analysis is, we submit, a correct one. It presents a

path to solution that is moderate and considerate; yet no

opportunity is permitted for evasion in the end. It author

izes the courts to take into account the welfare of the people

as a whole and to perform the traditional function of a court

of equity to weigh the injury to the plaintiff against the

damage that will result from the grant of the relief

requested.

This determination by the District Court was right. It

was authorized by the Supreme Court. This breadth of per

mitted discretion must not be overlooked in a review of the

application of the rule so formulated.

2.

The Exercise of Discretion

The question faced by the District Court was to apply

this rule to the facts of the case before it.

10

That is not the same question as the one presented to this

Court. The question here is quite different: with recogni

tion of the broad area of discretion given to the local Dis

trict Courts to evaluate all factors in a particular local

situation, can this Court say that the District Court abused

its powers in delaying immediate integration ? Is it incredi

ble that a reasonable judge acting within the framework so

established by the Supreme Court could have found it proper

to delay integration? We submit that negative answers to

these questions are required.

To test this result, we turn to the facts. The District

Court saw them in quite a different way from that in which

they are presented here by the appellants. It found Prince

Edward County to be a locality which had slowly but steadily

made an economic recovery from the poverty which pre

vailed there following the War Between the States. It

found that racial relations had improved in recent years

and that school facilities now provided for Negro children

were equal or superior to those for the white. But public

sentiment had changed sharply since the Supreme Court

acted, and the school authorities had been hard pressed to

keep open the public schools of the County. These officials

have no taxing power under Virginia law and, while they

prepared and submitted annual budget requests to the Board

of Supervisors (the County tax-levying body), funds have

been appropriated to the school authorities only on a month

to month basis. Moreover, the Board of Supervisors has

publicly announced its intention to cut off further appropria

tions if the County schools are mixed racially at this time.

More than 4,000 residents of the County have signed a

petition supporting this position of the Board of Super

visors ; they are elected, but the school officials are not (P. A.

40-3). The total population of the County is about 15,000

(A. A. 17), so the signers were more than a quarter of all

11

the people. Tentative and substantial plans have been made

for a private school system for white pupils in the event

of immediate integration, but no similar provision had been

made for the Negro (P. A. 45). The District Court found

it uncontroverted that race relations were more strained

than at any time during the present generation (P. A. 43).

It further found as a fact that, if the requested relief were

granted, permanent injury to children of both races would

result (P. A. 47). It concluded:

“A sudden disruption of reasonably amicable racial

relations which have been laboriously built up over a

period of more than three and a quarter centuries would

be deplorable. At any reasonable cost, it must be

avoided.” (P. A. 46)

This does not mean inaction for an indefinite period. The

District Court said:

“I believe the problems to be capable of solution but

they will require patience, time and a sympathetic

understanding. They cannot be solved by zealous advo

cates, by an emotional approach, nor by those with

selfish interests to advance. The law has been an

nounced by the Supreme Court and must be observed

but the solution must be discovered by those affected

under the guidance of sensible leadership. These facts

should be self evident to all responsible people.” (P. A.

43-4)

and it added:

“Many minds are now engaged in seeking an equita

ble solution to the problem. . . . It is inconceivable that

any of the litigants or other persons affected would

willingly see the public school system abolished or an

interruption in the education of the children of the

county.” (P. A. 47)

12

The District Court concluded that the appellees “have

done all that reasonably could be required of them in this

period of transition” (P. A. 46-7). That result of necessity

follows because:

“It is imperative that additional time be allowed the

defendants in this case, who find themselves in a posi

tion of helplessness unless this Court considers their

situation from an equitable and reasonable viewpoint.”

(P. A. 47)

This is an impressive and thoughtful review of local con

ditions leading to a considered conclusion. The appellants

assert first that it is sociologically wrong and, as an after

thought, add that it is legally wrong.

We do not propose to argue sociology to this Court. We

note that some of the cited names (Brief, pp. 14-5) are the

same as those of witnesses who were discredited in the

original hearing of this case; we likewise note with interest

the absence of the name of Gunnar Myrdal. We have no

doubt that we could obtain or have prepared a list of articles

equally imposing in length and expressing views diametrical

ly opposed to those held by the cited experts. We suggest

that facts (of which this Court may take judicial notice) as

to events in Arkansas, North Carolina and Tennessee make

absurd the argument that immediate integration is the only

proper path.

This is the only case that has come before this Court (or

any other court of which we are aware) where the uncon

tradicted evidence shows that all public schools in the area

will be closed if integration is ordered at the present time.

We reemphasize that this result will occur not as the result

of State statutes but because of united local sentiment that

will cut off all local funds for the support of the schools. This

is not Charlottesville, Arlington, Newport News or Norfolk

13

where other District Courts have not found that such facts

exist. In Newport News and Norfolk, the District Court

expressed the opinion that the schools would continue re

gardless of the order entered. In those cases, under differ

ent facts, the District Courts exercised their discretion to

require desegregation to begin more rapidly and their deci

sions have been upheld by this Court as being within the

broad range of discretion allowed to the District Courts.4

But the review of discretion is the same without regard

to how it has been exercised. The same principles apply no

matter whether or not a District Court concludes that inte

gration should be required at the present time. The District

Court decided here that immediate desegregation is not

required on the basis of the facts of record before it and this

Court’s decisions from other Virginia localities support its

action regardless of what the appellants suggest (Brief, pp.

10-11, 15). In the joint appeal in the Charlottesville and

Arlington cases Chief Judge Parker, speaking for this

Court, summarized the reasons for affirming the lower

courts’ orders by saying:

“There is no basis for the contention that either of

the judges below abused his discretion. . . . ” (240 F.

2d at p. 64)

It is appropriate here to note the language of the Eighth

Circuit Court of Appeals in the Little Rock, Arkansas, case.5

There the District Court denied the Negro request for an

injunction to speed up integration in Little Rock. In affirm

ing this action the Circuit Court, speaking through Judge

Vogel, said:

i School Board of Charlottesville v. Allen, 240 F. 2d 59 (C. A. 4,

1956), cert, denied, 353 U. S. 910, 911 (1957) ; School Board of New

port News v. A tkins,.....F. 2 d ....... (decided July 13, 1957).

5 Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 (C. A. 8, 1957).

14

“Appellants cite to us several cases where Federal

Courts have used their injunctive powers to speed up or

effectuate integration. Willis v. Walker, D.C.W.D.

Ky. 1955, 136 F. Supp. 177; Thompson v. County

School Board of Arlington County, D.C.E.D. Va.

1956, 144 F. Supp. 239; Clemons v. Board of Educa

tion, 6 Cir., 1956, 228 F. 2d 853, certiorari denied 1956,

350 U. S. 1006, 76 S. Ct. 651, 100 L. Ed. 868; Booker

v. State of Tennessee Board of Education, 6 Cir., 1957,

240 F. 2d 689. These decisions serve only to demon

strate that local school problems are 'varied’ as referred

to by the Supreme Court. A reasonable amount of time

to effect complete integration in the schools of Little

Rock, Arkansas, may be unreasonable in St. Louis,

Missouri, or Washington, D. C. The schools of Little

Rock have been on a completely segregated basis since

their creation in 1870. That fact, plus local problems

as to facilities, teacher personnel, the creation of teach

able groups, the establishment of the proper curriculum

in desegregated schools and at the same time the main

tenance of standards of quality in an educational pro

gram may make the situation at Little Rock, Arkansas,

a problem that is entirely different from that in many

other places. It was on the basis of such 'varied’ school

problems that the Supreme Court in the second Brown

decision remanded the cases there involved to the local

District Courts to determine whether the school author

ities, who possessed the primary responsibility, have

acted in good faith, made a prompt and reasonable start,

and whether or not additional time was necessary to

accomplish complete desegregation.” (243 F. 2d at pp.

363-4)

We believe that subsequent events in Little Rock have

proved the wisdom of this decision.

Those who are familiar with conditions in Prince Edward

County or who have read the record in this case will immedi

ately realize that conditions there are difficult in the extreme.

15

The District Court has weighed the factors that it was

instructed to weigh by the Supreme Court. These factors

include the right of Negro children to attend integrated

schools as soon as feasible, the overall public interest in

volved, the necessity for adjustment in attitudes, and the

planning required to devise an integrated system. It very

properly concluded that integration should not come here

at once. This is not due to any fault on the part of the school

authorities. Indeed, they are responsible community leaders

who have had to fight to keep the public schools of the

County open in any manner. This fight has had to be car

ried on without tax-levying powers and within the frame

work of State law. Who could have done more? Who in

Prince Edward County can finally bring about integration

if these men cannot ? The District Court wisely exercised its

discretion in favor of allowing them more time for the

moment.6 Its decision should be affirmed.

V.

CONCLUSION

In the rural area of Prince Edward County, the continu

ance of public education hangs on the decision in this case. A

wise judge, familiar with local affairs, has exercised the

broad discretion conferred on him by the Supreme Court to

defer compulsory immediate integration. The choice pre

sented by the appellants here is a limited one: they say that,

. 81?, this connection the Court’s attention is invited to the interest-

mg dissent filed by Judge Cameron in the recent school case of Avery

v. Wichita Falls Independent School District, 241 F. 2d 230 (C. A. S

1957), cert, denied, 353 U. S. 938 (1957), where he states:

The Supreme Court has recognized as imposed upon the

District Courts responsibilities of statesmanship in addition to

the duty to pass upon legal points.”

16

without regard to the excellent schools that they now have,

the schools must either integrate or close. The choice is

not so radically narrow, as the District Court pointed out.

Its action should be affirmed.

Dated September 30, 1957.

Respectfully submitted,

K enneth C. P atty

Attorney General of Virginia

Court Library Building

Richmond, Virginia

H enry T. W ickham

Special Asst, to the Attorney General

State-Planters Bank Building

Richmond, Virginia

Counsel for the

Commonwealth of Virginia

H unton , W illiams, Gay, T. Justin Moore

Moore & P owell A rchibald G. Robertson

0} Counsel John W. R iely

T. Justin Moore, Jr.

1003 Electric Building

Richmond 12, Virginia

Counsel for the Prince Edward

County School Authorities