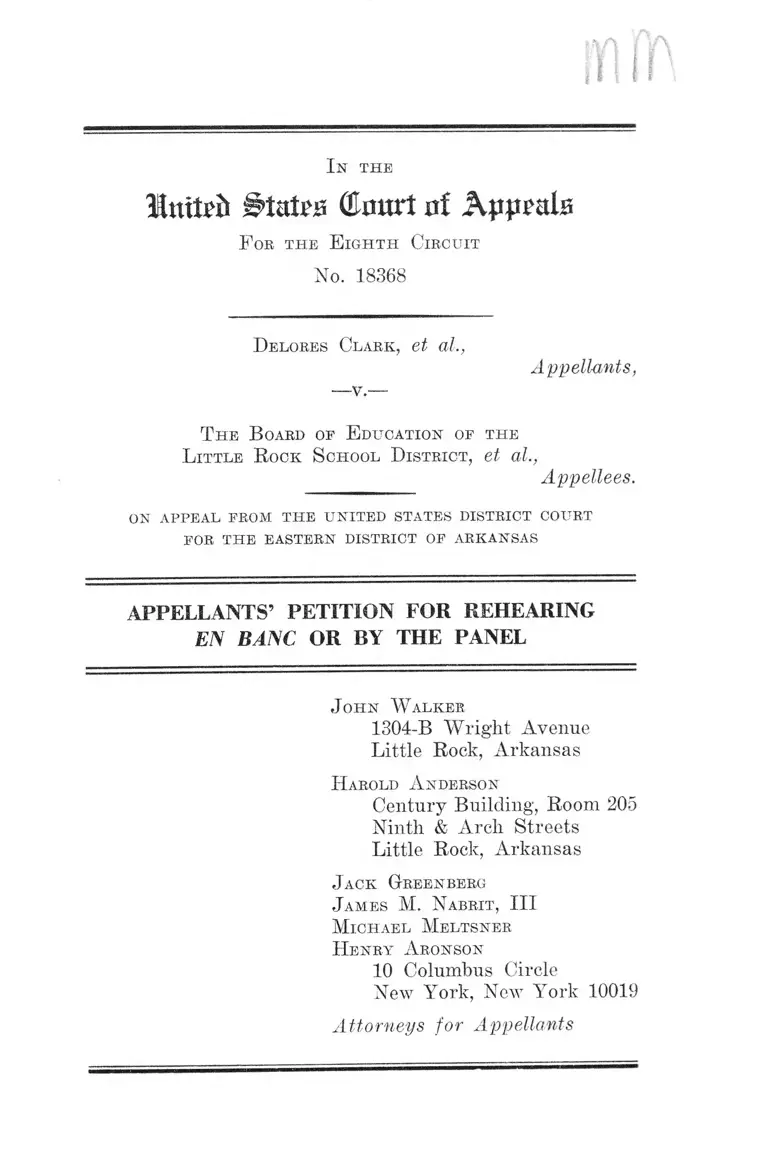

Clark v. Little Rock Board of Education Appellants' Petition for Rehearing En Banc or By The Panel

Public Court Documents

January 13, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clark v. Little Rock Board of Education Appellants' Petition for Rehearing En Banc or By The Panel, 1967. 2f7ab8a4-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/de40b457-c087-4d07-b5e0-1814014d9674/clark-v-little-rock-board-of-education-appellants-petition-for-rehearing-en-banc-or-by-the-panel. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

In the

Imfrft States (Emtrt of Appals

F ob the E ighth Circuit

No. 18368

Delores Clark, et al.,

-v.-

Appellants,

T he B oard oe E ducation of the

L ittle Rock School District, et al.,

Appellees.

o n a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS

APPELLANTS’ PETITION FOR REHEARING

EN BANC OR BY THE PANEL

John W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

H arold A nderson

Century Building, Room 205

Ninth & Arch Streets

Little Rock, Arkansas

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Michael Meltsner

H enry A ronson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

In t h e

Ittttefc (Hiwrt nl Appeals

F ob the E ighth Circuit

No. 18368

Delobes Clark, et al.,

—v.-

Appellants,

T he B oard of E ducation oe the

Little B ock S chool District, et al.,

Appellees.

on appeal from the united states district court

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS

APPELLANTS’ PETITION FOR REHEARING

EN BANC OR BY THE PANEL

Appellants respectfully petition this Court for rehearing

en banc, or in the alternative by a panel of the Court, of

the Court’s approval of the lateral transfer provision in

the Little Bock, Arkansas school desegregation plan. This

provision denies mandatory, annual freedom of choice as

signment (except during the First, Seventh and Tenth

grades) by which all students must express a preference

for assignment which is granted absent overcrowding, in

which case all students are assigned on the basis of resi

dential proximity to school. Appellants seek rehearing

because (1) subsequent to the Clark decision (December 15,

1966) a conflict has developed between constitutional

2

standards for desegregation prevailing in this circuit and

those prevailing in the Fifth Circuit by the decision of

the later court in United States v. Jefferson County Board

of Education, et al, No. 23345 (Dec. 29, 1966) and (2) the

Clark decision rests on a demonstrably false factual prem

ise as to the burden of Negro students under the lateral

transfer plan.

I.

The Fifth Circuit has adopted as constitutionally re

quired minimum standards in free choice plans applicable

to all districts within that circuit a mandatory free-choice

provision in all grades which conflicts directly with the

lateral transfer provision approved in Clark v. Board of

Education (pp. 10-13 of slip opinion). As of December 29,

1966, the Fifth Circuit requires school boards to comply

with the following provision:

(b) Annual Exercise of Choice. All students, both

white and Negro, shall be required to exercise a free

choice of schools annually.

(c) Choice Period. The period for exercising choice

shall commence on March 1 and end on March 31 pre

ceding the school year for which the choice is to be

exercised. No student or prospective student who

exercises his choice within the choice period shall be

given any preference because of the time Avithin the

period when such choice was exercised.

(d) Mandatory Exercise of Choice. A failure to

exercise a choice within the choice period shall not

preclude any student from exercising a choice at any

time before he commences school for the year with

respect to which the choice applies, but such choice

may be subordinated to the choices of students who

exercised choice before the expiration of the choice

period. Any student who has not exercised his choice

of school within a week after school opens shall be

assigned to the school nearest his home where space

is available under standards for determining avail

able space which shall be applied uniformly through

out the system, (slip opinion App. A, p. 2a, United

States v. Jefferson County Board of Education).

The Court in United States v. Jefferson County School

Board in requiring annual, mandatory choice reasoned as

follows:

“In place of permissive freedom of choice there must be

a mandatory annual free choice of schools by all students,

both wrhite and Negro. ‘If a child or his parent is to be

given a meaningful choice, this choice must be afforded

annually.’ Kemp v. Beasley, 8 Cir. 1965, 352 F.2d 14, 22.

The initial assignment, within space limitations, should be

made by a parent or by a child over fifteen without regard

to race. This mandatory free choice system would govern

even the initial assignment of students to the first grade

and to kindergarten. At the minimum, a freedom of choice

plan should proved that: (1) All students in desegregated

grades shall have an opportunity to exercise a choice of

schools. Bradley v. School Board Richmond, Va., 4 Cir.,

1965, 345 F.2d 310, vacated and remanded, 1965, 382 U.S.

103; (2) where the number of applicants applying to a

school exceeds available space, preferences will be deter

mined by a uniform non-racial standard, Stell v. Savanna.lt-

Chatham County Board of Education, 5 Cir. 1964 333 F.2d

55, 65; and (3) when a student fails to exercise his choice,

he will be assigned to a school under a uniform non-racial

standard, Kemp v. Beasley, 8 Cir. 1965, 352 F.2d 14, 22.

(emphasis supplied)” (slip opinion pp. 49, 50)1

The conflict between the decision in Clark, supra, and

the Fifth Circuit ruling in United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education merits reconsideration by the

Court. The seriousness of a conflict with the Fifth Cir

cuit is plan for it means that the constitution is to mean

different things in different states. Only the United States

Supreme Court can resolve such a conflict but before a

matter of such sensitivity, involving the constitutional

rights of so many, is presented to the Supreme Court,

every opportunity for resolution should be explored.

Re-examination of Clark, supra, in light of United States

v. Jefferson County Board of Education, is also supported

by the paiticular circumstances of that case. The opinion

disposes of seven cases argued and extensively briefed

during the summer of 1966 by attorneys for numerous

Negro students and parents, the United States and school

boards from three states. The opinion of the court with

footnotes, runs to over 100 pages and includes the most

far ranging review and discussion of the theory and prac

tice of school desegregation in recent years. The decision

includes a comprehensive, specific, decree which district

courts are to adopt in order to insure uniformity and

regularity. (Significantly, one of the reasons for the draft

ing of this decree with standards no lower than those of

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, is the

actual experience of the Fifth Circuit that school boards

faced with lower judicial standards than those set forth

by the Guidelines of the Department have managed to

1 It should be noted that the Fifth Circuit relied, in part, on language

in an earlier decision of this Court, Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14, 22

which appears inconsistent with the approval of lateral transfer by a

different panel of the Court in Clark.

5

obtain decrees in federal court providing for only minimum

desegregation efforts.)2

Tbe critical passage in thfi Court’s opinion in Clark

upholds lateral transfer and rejects a mandatory annual

free choice requirement, as follows:

In the plan before us the students are required to

choose before entering the first, seventh and tenth

grades. They are not, however, “locked” to their

initial choice. They are afforded an annual right to

transfer schools if they so desire. The failure to

exercise this right does not result in the student being

assigned to a school on the basis of race. Rather, the

student is assigned to the school he is presently at

tending*, by reason of a choice originally exercised

solely by the student, (emphasis in original.) (P. 11

of slip opinion.)

5 Facts overlooked by the Court render the last sentence

of the quoted passage inaccurate/

The Court has concluded that the annual voluntary

“right” to request and obtain transfer constitutes a suffi

cient desegregation plan because it permits Negro students

to seek annual placement in a desegregated school on

similar terms to the mandatory free choice which takes

place in the first, seventh, and tenth grades, the only dis

tinction between the two being that in the first, seventh,

and tenth grades all students choose schools rather than

only those seeking transfer. In short, the premise is that

.. 2 “ In Louisiana alone twenty school boards obtained quick decrees

providing for desegregation according to plans greatly at variance with

the Guidelines.” ( United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

p. 17 of Slip Opinion).

II

a real, unencumbered and not illusory opportunity for

admission to a desegregated school exists for those who

desire it.

Contrary to the assumption of the Court, however,

Negro students are “ locked” to their initial choice and

seriously burdened in escaping from “ Negro” schools be

cause under this plan they can only exercise their lateral

transfer “ right” to the extent that the school they choose

is not overcrowded.

“Lateral transfers will be made as requested unless the

choice results in overcrowding at the school chosen.”

(Report and Motion, see pp. 10a, 11a of Appellants

Reply Brief.)

As the lateral transfer request will be granted only

to the extent there are vacancies, the difference between

the capacity of each school and the number of students

presently attending such schools sets the ceiling for the

successful exercise of the lateral transfer provision. I f

a school is enrolled up to its capacity no lateral transfer

is possible. In fact, white students are also “ locked in”

in the sense that they are protected in retaining their

original assignment. As the lateral transfer “ right” is

necessarily limited by capacity of the school applied to,

it is a fundamentally different “ right” than that granted

under the mandatory freedom of choice provision (operat

ing during the first, seventh and tenth grades) because

in those grades all students choose school assignments and

when a school will be overcrowded assignment is deter

mined for all students (not just those seeking a change

in assignment) solely on the basis of residential proximity

to the school.3

To show that this is no abstract difference (between operation of

mandatory, annual free choice and lateral transfer) we call the court’s

7

Secondly, the Little Hock Plan approved by this Court

was not adopted until April 23, 1965. (See Opinion, p. 3a

of Appellants’ Eeply Brief.) The first year in which the

present combination freedom of choice—lateral transfer

plan operated was the 1966-1967 school year. Previously,

the Board employed the Arkansas Pupil Assignment Lawr,

an assignment system which this Court has condemned, to

assign students initially on the basis of race (see pp. 3, 4,

of slip opinion in Clark v. School Board)}

Necessarily then students presently in the second, third,

fourth, fifth and sixth grades, and the eighth and ninth

grades will not have an unburdened choice of schooling

if they determine to seek desegregation until they reach

either the seventh and tenth grades, respectively. In

the case of students in the eleventh grade they will never

have an unburdened choice. These Negroes are “ locked in”

to the extent there is not sufficient classroom space avail

able in schools to which they desire to attend as discussed

above. In addition, they are presently attending particular

schools by reasons of their race for they were all assigned * 4 *

attention to the fact that under the transfer plan in operation in 1965,

53 Negro transfer applications out o f 188 were rejected (Brief of

appellees, p. 29).

4 There may be some question as to whether the freedom o f choice—•

lateral transfer plan first went into operation during the 1965-66 school

year or during the 1966-67 school year, and therefore, whether students

in the second, eighth and eleventh grades have been assigned on the basis

of the Arkansas Pupil Placement Act or subsequent to a mandatory

choice. Appellants believe the record shows that 1966-67 was the first

year of legitimate free choice but resolution of this question does not

effect their challenge to the assumption on which approval of the trans

fer plan rests for the fact remains that Negro students in other grades

are “ locked in” and burdened because they were initially assigned on the

basis o f race and can only transfer to the extent space is available. In

this regard it is relevant that in Clark, supra, Slip Opinion p. 13, the

eourt found the notice provisions of the Little Eoek plan defective and,

therefore, no students presently attending publie school in Little Rock

has really been given a constitutionally adequate free choice.

8

under the old, unconstitutional pupil assignment approach

prior to approval of the present freedom of choice—lateral

transfer plan by the district court in 1965. They are by

reason of their initial assignment and the “overcrowding”

restriction on successful transfer in the same position as

the students in Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir.

1965), who were forced to use burdensome transfer provi

sions to extricate themselves from initial racial assign

ment.6 It is erroneous to say of these students as the

Court premised, see supra, p. 5, that they are “ assigned

to the school [they are] presently attending by reason

of a choice originally exercised solely by the student.”

This Court does not need to be told of the significance

of the Little Rock School case to desegregation of the

schools of Arkansas and, indeed, the nation as a whole.

Because of the clear conflict between the Fifth Circuit

and this Court and because the reasoning in Clark, supra,

rests on factual assumptions as to the kind of choice avail

able to Negro students which we believe are incorrect,

plenary reconsideration of this appeal is appropriate and

serves the interests of justice.

6 In recent months, lateral transfer provisions, having the effect of

limiting transfer rights of Negro students by the capacity of the schools

to which assignment is sought have been approved in several Arkansas

school districts. See e.g., Marks v. The Nero Edinburg School District,

No. FB 66 C-71 (E.D. Ark. Dec. 22); Jackson v. Marvell School District,

No. N66 C-35 (E.D. Ark. Dec. 22, 1966). The public importance of the

validity of lateral transfer is magnified by the fact that in these cases,

as here, Negro students presently attending school will not have a choice,

uninfluenced by capacity limitations, to leave their racially assigned

“Negro” schools until they reach the seventh and tenth grades.

9

Wherefore,

granted.

appellants pray that the petition be

Respectfully submitted,

John W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

H arold A nderson

Century Building, Room 205

Ninth & Arch Streets

Little Rock, Arkansas

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

M ichael Meltsner

Henry A ronson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

10

Certificate of Counsel

This is to certify that this petition is submitted in good

faith and that I believe it to be meritorious.

M ichael Meltsnek

Attorney for Appellants

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that copies of the foregoing were mailed

to Herschel Friday, Esq., attorney for appellees, at his

office this 13th day of January, 1967, air mail, postage

prepaid.

Attorney for Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. 219