Plaintiffs' Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1967

26 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Green v. New Kent County School Board Working files. Plaintiffs' Reply Brief, 1967. 43d3178f-6d31-f011-8c4e-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/de4dd5c7-066b-41df-9027-e3d4b89e7dfc/plaintiffs-reply-brief. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

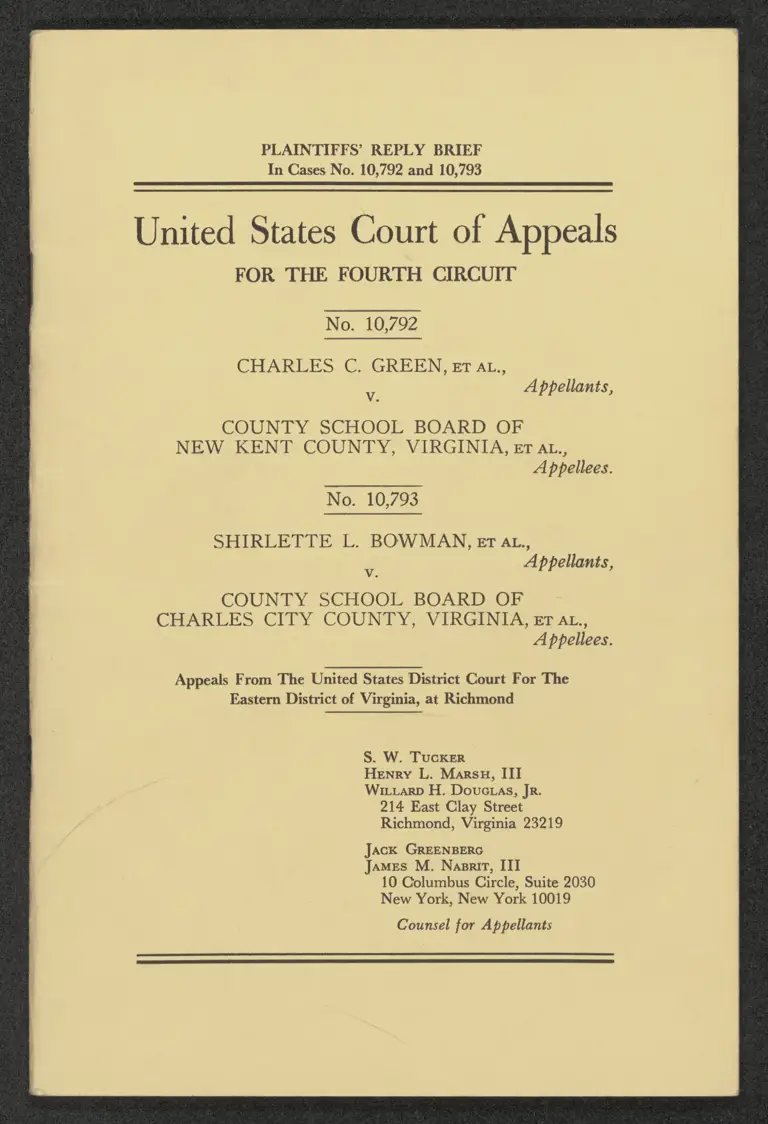

PLAINTIFFS’ REPLY BRIEF

In Cases No. 10,792 and 10,793

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 10,792

CHARLES C. GREEN, ET AL,,

V.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF

NEW KENT COUNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL,

Appellees.

Appellants,

No. 10,793

SHIRLETTE L. BOWMAN, ET AL,,

Appellants,

V.

COUNTY SCHOOL. BOARD OF

CHARLES CITY COUNTY, VIRGINIA, FT AL,

Appellees.

Appeals From The United States District Court For The

Eastern District of Virginia, at Richmond

S. W. Tucker

Henry L. MarsH, III

WiLLarp H. DoucLas, Jr.

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Jack GREENBERG

James M. Nasri, III

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ARGUMENT

The Supreme Court, In 1955, Rejected Freedom Of Choice .... 1

There Is No Sound Basis For Freedom Of Choice In The

Instant Cases o.oo. Lind il ls 6

The Basic Factual And Legal Assumptions Of Briggs v.

Elliott Were Unsound o.oo. ini. ni il 7

Racial Segregation IS Discrimination ......ooc..ii anil 9

The Court’s Viable Judgments Do Not Permit Freedom Of

Choice In The Subject Coufies c..siceiorenitosiorratosioerroetenss 10

Public Officials Should Be Reminded That The Time For

#¥Deliberate Speed’ Has Expired ....o.....in-doodioiieecnniens 13

CONCLUSION orien otsiasitsiirinsinssesststinsssisions inns sisi seeiacsorindssts 15

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Bell v. School Board of the City of Staunton, (W.D. Va. No.

65-C-6-H; September 14, 1866) ....cccoiiviiiiiiiiiiiiiiovemiiivnii 14

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1934) ..........ci.. ii 2,6 10; 13

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond (Bradley I) 317

F.24 429 (Ath Cir. 196%) vooioiiiinisl dviing ittninisinioniinesss 8

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond (Bradley IT) 345

F-24310 (1968) con.onsrnctiinie eo 0 ice boon 792 12,13

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, ........ Bs: ;

26 S.Ct 224 151. ed 24 187 (1965) .......s..socoovo encase. 13, 15

Briggs v. Ello, 132 FV. 2d 776 (ED. S.C. 1955) ...... 7: 8.9: 11

Brown v. Board of Education (Brown I), 347 U.S. 483

(1954) vidi dn lille an 2:01 13

Page

Brown v. Board of Education (Brown II), 349 U.S. 294

E00 VERT ae ER Cr AS 34.9

Brown v. Board of Education, 139 F. Supp. 470 (D.C. Kan. 1955)

Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County, 332 F. 2d

A52 {Ah Clr, 1968) ci ddd hd tienh 11,

Cameron v. Board of Education of the City of Bonner Springs,

182 Kan. 39, 318 P, 24 983 (December 7, 1957) ....-tciviicsocsens

Carson v. Warlick, 238 VF. 24 724 (4th Cir. 1956) «.....ccooinncciconne

Cooper v.. Aaron, 353. US. F (1988), outshine iotiids

Dillard v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, 308 F. 2d

920: (4th Cina 1962) tities i Bini iris perimin osininba le

Dillard v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville, 374 U.S.

7S EAGER Oe mL ST RE el et

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683 (1963) ....

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 377

US. 218 (1954) 1.0 i iii

Hill v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 282 F. 2d 473 (1960)

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72

00,01 EEL ONO a Tae VE Nee lo 11;

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta County (W.D. Va. No.

65-C-5-H, August 6, 1960)..............ccoiinconiruisentiesoisissstsincsiminess

Kilby v. County School Board of Warren County (W.D. Va. No.

530, OCtODBL 7, YI00). .oi.icccvsiisuscissmmmssnsivbntuosiiossmnansinntissonssrssnsste

Rogers v. Paul, ........ 1S... + 86 S.Ct. 258 (1965Y; 15 1. 2d

203 (106%)... at) Rit rR eit vires

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.

2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965)

Swann v. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

Fi2d..... , 4th Cir. No. 10,207, October 24, 1966

7)

11

6

13

14

14

Page

Taylor v. Board of Education of New Rochelle, 191 F. Supp.

131: (SD: NY. 1961) ve 14

Watson v. City of Memphis, 3731.8. 526 (1963) ...;.co.onenesivicen 15

Other Authorities

Acts of Assembly

Extra Session 1956, Chrapler 70 coon icine Brteniittse ie 8

Extra Session 1959, Clapter 71 ........inide ie ccnecisasioiss 8

Richmond News Leader

November 3, 1066 i.e ie ba 14, 15

Richmond Times Dispatch

November 3, 1066... ieee 14, 15

NOVEMBRE 4, YO0B. ... cocci ovmiceriindiiicenvmnss tis horns stor siiuntosamasass 14

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 10,792

CHARLES C. GREEN wraL,

Appellants,

V.

COUNTY SCHOOL, BOARD OF

NEW KENT COUNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL,

Appellees.

No. 10,793

SHIRLETTE I. BOWMAN, gr AL,

Appellants,

V.

COUNTY SCHOOL, BOARD OF

CHARLES CITY COUNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL,

Appellees.

Appeals From The United States District Court For The

Eastern District of Virginia, at Richmond

PLAINTIFFS REPLY BRIEF

ARGUMENT

The Supreme Court, In 1953, Rejected Freedom Of Choice

Counsel for the school boards suggests, and the appel-

lants agree, that if we hope ever to find refuge from the

2

stormy seas of litigation in the area of racial segregation

in public schools, we must at least remember what the light-

house looked like. We submit that the broad outlines were

pictured on May 17,1954, viz:

“In each of these cases, minors of the Negro race,

through their legal representatives, seek the aid of the

courts in obtaining admission to the public schools of

their community on a nonsegregated basis. In each

instance, they have been denied admission to schools

attended by white children under laws requiring or

permitting segregation according to race.

kt fi

“We conclude that in the field of public education the

doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate

educational facilities are inherently unequal. There-

fore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly

situated for whom the actions have been brought are,

by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived

of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment.” [Emphasis added.] Brown

v. Board of Education, (Brown 1), 347 U.S. 483, 487,

495 (1954).

“We have this day held that the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the

states from maintaining racially segregated public

schools. The legal problem in the District of Columbia

is somewhat different, however. * * * The ‘equal pro-

tection of the laws’ is a more explicit safeguard of pro-

hibited unfairness than ‘due process of law,” and,

therefore we do not imply that the two are always

interchangeable phrases.” [Emphasis added.] Bolling

v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 498 (1954)

Those unyielding principles having been settled, the Court

again faced, requested re-argument upon, and thereafter

3

made its subsequent decision with respect to, two possible

courses, viz:

“(a) Would a decree necessarily follow providing that,

within the limits set by normal geographic school dis-

tricting, Negro children should forthwith be admitted

to schools of their choice, or

“(b) May this Court, in the exercise of its equity

powers, permit an effective gradual adjustment to be

brought about from existing segregated systems to a

system not based on color distinctions.” Brown Vv.

Board of Education (Brown 11), 349 U.S. 294 (1955)

footnote 2.

Question (a), first posed to counsel on June 8, 1953

(345 U.S. 972), troubled the Supreme Court because it was

considering something of much more disturbing potential

than an annual choice of a Negro parent to enroll his child

in a racially segregated school or in a school attended by

white children. The Court was considering the non-waivable

constitutionally protected civil right of every Negro child to

be enrolled forthwith in the public school attended by simi-

larly situated white children. [“At stake is the personal

interest of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools as

soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis’ Brown v.

Board of Education (Brown II), 349 U.S. 294, 300

(1955).] State maintenance of racially segregated schools

being forbidden by the Fourteenth Amendment, how might

a court decline to enjoin forthwith the operation of any

such school? Would not every Negro child be entitled at

any hour of any day to leave a racially segregated school

and demand enrollment in the school attended by similarly

situated white children? Could the state be permitted to

plead its unconstitutional maintenance of the segregated

a

I

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4

school in which it had suffered the Negro child to be

enrolled in violation of the state’s duty not to deny that child

the equal protection of the laws and thus frustrate the

child’s immediate assertion of his or her constitutional

right? Would a decree necessarily follow which would in-

evitably invite daily chaos and confusion in all segregated

school systems; or might the Court, in the exercise of its

equity powers, permit school boards to effect gradual ad-

justments from segregated systems to systems not based

on color distinctions?

In further fashioning the lighthouse, the Court considered

briefs and arguments of counsel for the Negro school chil-

dren and briefs and arguments of counsel for the United

States, for the States of Virginia, Kansas, Delaware, South

Carolina, Florida, North Carolina, Arkansas, Oklahoma and

Texas, and for the District of Columbia. The Court was

well informed of the “substantial steps to eliminate racial

discrimination in public schools” which had been taken in

several states and it noted the “substantial progress” which

had been made in the District of Columbia and in the com-

munities in Kansas and Delaware involved in this litigation.

(Brown 11, 349 U.S. at 299) Even then, the City of Balti-

more had removed the racial limitations from its pre-exist-

ing policy under which transfer because of changes of resi-

dence had been routinely approved and transfers for other

reasons might be approved by the two principals involved

or by the appropriate Assistant Superintendent. In the light

of all of this, the Court considered the two alternatives:

one which would permit Negro children and their parents

to haphazardly bring about racial desegregation in a school

system and the other which would require the school au-

thorities to systematically “effectuate a transition to a

racially nondiscriminatory school system.” (Brown II, 349

a

5

U.S. at 301) The Court deliberately rejected the notion of

Freedom of Choice which it had posed in its question (a).

In so doing, it postponed the vindication of the immediate

rights of the children who had prevailed, in order to permit

the school authorities then before the Court to desegre-

gate their respective school systems with the kind of efh--

ciency and dispatch which would effect the nondiscrimina-

tory school assignments of the children then before the

Court (‘the parties to these cases”) with all deliberate

speed. That the lighthouse, as completed in 1955, was un-

mistakably recognizable to those who would but look is

illustrated by this 1957 holding and judgment of the Su-

preme Court of Kansas: ;

“We therefore hold that the maintenance of a segre-

gated grade school for colored children by the Board of

- Education of the City of Bonner Springs is racial

discrimination in public education and must yield to

the principle that such discrimination is unconstitu-

tional in that it deprives the children of the minority

group of equal educational opportunities. It amounts

to a deprivation of the equal protection of the laws

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Fed-

eral Constitution.

“It is therefore by the court ordered and adjuged that

a peremptory writ of mandamus issue to each and all

of the named defendants, directing them to proceed

with reasonable diligence to integrate the public grade

schools in the school district of Bonne Springs, Wyan-

dotte County, Kansas, and to comply with the order of

this court in no event later than the commencement of

the fall term of school in 1958.” Cameron v. Board of

Education of the City of Bonner Springs, 182 Kan.

39,318 P. 24,938 (Dec. 7, 1957).

6

There Is No Sound Basis For Freedom Of Choice In The

Instant Cases

Many divergent courses have been deliberately set in

order to avoid the plain and obvious holding of the Supreme

Court that the Equal Protection Clause prohibits the states

from maintaining racially segregated schools. In this case

the school authorities suggest that the “more explicit safe-

guard of prohibited unfairness” which the Fourteenth

Amendment holds out to Negro children living in the several

states should be withheld in the case at bar because Dr.

James M. Nabrit, Jr. (whom appellees misidentify as James

M. Nabrit, III, of counsel for the instant appellants) did

not urge the Supreme Court to grant “Equal Protection”

relief for the Negro children residing in the District of

Columbia whom he represented in Bolling v. Sharpe, supra.

Then after quoting at length from Brown I, (stopping

just short of what the Court stated to be its holding in that

case) they jump to two sentences in the subsequent opinion

of the District Court in that case (the Topeka, Kansas case)

which suggest that court’s view of the meaning of the term

“desegregation”; entirely overlooking the fact that the

three judge district court wrote those two sentences when

reviewing “a good faith beginning to bring about complete

desegregation’ under a plan the “central principle” of which

was that “except in exceptional circumstances, school chil-

dren irrespective of race or color shall be required to attend

the school in the district in which they reside and that color

or race is no element of exceptional circumstances warrant-

ing a deviation from this basic principle.” Brown v. Board

of Education, 139 F. Supp. 470 (D. C. Kan. 1955).

The siren song “Freedom of Choice” has lured us from

the equal protection principle that the states are forbidden to

7

maintain racially segregated schools. The doctrine “sprang

forth fully armed” from Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. 2d 776

(E. D. S. C. 1955)—one of the very cases in which it had

been rejected by the Supreme Court just forty-five days

earlier. It serves as the basis for the decision of this Court

in Bradley 11 (Bradley v. School Board of the City of Rich-

mond, 345 F. 2d 310 (1965)) on which the appellees rely.

We do not argue that freedom of choice is constitutionally

impermissible in a situation where “a system of free trans-

fers is the only means by which many Negroes can attend

integrated schools.” (Swann v. The Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, ...... FE. 2 uu 4th Cir. No.. 10,207

October 24, 1966, citing, at footnote 5, Bradley 11.) We

merely argue that where, as here, racially segregated schools

could not exist but for “{reedom of choice” beiween the

school attended by white children and the (constitutionally

impermissible) segregated school, freedom of choice must

be condemned for what it clearly is—the means by which

the state continues to maintain a racially segregated school

and without which such racially segregated school would

cease to be.

The Basic Factual And Legal Assumptions Of Briggs v.

Elliott Were Unsound

Where the Briggs opinion says: “Nothing in the Consti-

tution or in the decision of the Supreme Court takes away

from the people freedom to choose the [public] school they

attend,” it ignores the fact that prior to 1954, and even when

it was being penned, people had no such freedom to choose

—certainly not with respect to the racial composition of the

schools and, as a general rule, not with respect to the loca-

tion of the schools. In Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724

—

—

—

—

\

8

(4th Cir. 1956), Judge Parker (Judges Sobeloff and Bryan

concurring) wrote:

“Somebody must enroll the pupils in the public schools,

they cannot enroll themselves; but we can think of no

one better qualified to undertake the task than the offi-

cials of the schools and the school boards having the

schools in charge.”

Seven years later, in Bradley v. School Board of the City of

Richmond (Bradley 1), 317 F. 2d. 429 (4th Cir. 1964),

Judge Boreman (Judges Bryan and Bell concurring) again

recognized the traditional function of school authorities in

promulgating rules governing the assignment of students to

schools, saying:

“That there must be a responsibility devolving upon

some agency for proper administration is unques-

tioned.”

The General Assembly of Virginia, by a Pupil Placement

Act (Acts 1956 Extra Session, chapter 70), purported to

“divest” local school boards and superintendents of all au-

thority to determine the school to which any child may be

admitted. By chapter 71 of the Acts of Assembly, Extra

Session 1959, it permitted localities to exempt themselves

from the Pupil Placement Act, authorizing local school

- officials in such localities “to fix attendance areas and adopt

such other additional rules and regulations . . . relating to

the placement of pupils as may be to the best interest of

their respective school districts and the pupils therein.” The

1966) repeal of these statutes does not erase the historical

fact that when Briggs v. Elliott was written the “freedom

[to choose among public schools], which the court said was

9

not taken away by the Brown decisions, had never existed,

at least not in Virginia.

Where the Briggs opinion says that the Constitution

“merely forbids the use of governmental power to enforce

segregation” it simply ignored the equal protection basis of

Brown 1 (as distinguished from the due process basis of

Bolling v. Sharpe) and the plain directive of Brown II that

the school board, under the supervision of the District

Court, “effectuate a transition to a racilaly nondiscrimina-

tory school system.” As Judge Wisdom observed in Single-

ton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 348 F. 2d

729 (5th Cir. 1965), Briggs “is inconsistent with Brown

and the later development of decisional and statutory law

in the area of civil rights.”

Racial Segregation IS Discrimination

Much has been written to undergird an unrealistic dis-

tinction between the word “discriminate” (which school

boards now concede they may not do) and the generically

included word “segregate” (which school boards contend

they may continue to do with regard to Negro children

whose parents are timid or indifferent). The opinion of this

Court in Bradley II, judgment in which was vacated, ......

US. ...... 8S. Ct. 224, 15 1. ed. 137 (19653), notes

that the Court in Brown II used the term “discrimination.”

On that basis this Court reasoned that by avoiding present

or future discrimination a school board may comply with

the Fourteenth Amendment. In the instant case, the school

authorities seek to reach the same conclusion by urging

selected definitions of “segregate” and “desegregate.”

The subject of the 1954 School Segregation Cases was

racial segregation in the public schools. The word “segrega-

tion” or a word of the same derivation appears in the text

10

of Brown 1 at least fifteen times and in the footnotes at

least ten times. The broader term “discrimination” appears

but once in the text (and three times in the accompanying

footnote 5) where the Court pointed out that its first cases

construing the Fourteenth Amendment interpreted it “as

proscribing all state-imposed discriminations against the

Negro race.” In Brown I, the Court was considering one

form of discrimination; i.e., separation of children by race

in the public schools “under laws requiring or permitting

segregation according to race” (347 U. S. at 488), and held

that particular form of discrimination to be violative of the

Equal Protection Clause.

In the companion case of Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U, S.

497 (1954), the Court used a derivative of “segregate” six

times and the word “discrimination” but twice; the thrust

of the opinion being that racial segregation in the public

schools of the District of Columbia is a discrimination

which is “so unjustifiable as to be violative of due process.”

No semantic analysis of the 1954 opinions can suggest the

Court’s unawareness of the obvious fact that racial segre-

gation in the public schools is an invidious discrimination.

Similarly, there is no basis for a suppositon that the Court

was excluding the concept “racial segregation” when, in

Brown 11, it alluded to its previous declaration of “the

fundamental principle that racial discrimination in public

education is unconstitutional” and stated its conclusion that

“la] 11 provisions of federal, state, or local law requiring

or permitting such discrimination must yield to this prin-

ciple.”

This Court’s Viable Judgments Do Not Permit

Freedom Of Choice In The Subject Counties

In Dillard v. School Board of the City of Charlottesville,

308 F. 2d 920 (4th Cir. 1962), this Court adopted an opin-

11

ion prepared by Senior Judge Soper which adhered to the

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958), rather than to the

earlier Briggs v. Elliott, supra, interpretation of Brown

and to the Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria,

278 F. 2d 72 (1960), approach to its implementation. Char-

lottesville’s “racial minority” transfer exception to its geo-

graphic assignment plan was condemned because the

wmherent “purpose and effect of the arrangement” was to

retard integration and retain the segregation of the races.

The denial of certiorari in that case (374 U.S. 827) follow-

ing the decision in Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville,

373 U.S. 683 (1963), vindicated this Court’s underlying

premise (as to which there had been vigorous dissent) that

the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees integrated schools.

In Buckner v. County School Board of Greene County,

332 F. 2d 452 (4th Cir. 1964), the District Court had re-

fused an injunction and entered order of dismissal “beliey-

ing the case to be moot because all of the individual infant

plaintiffs were in schools chosen by their parents or legal

guardians.” This Court’s opinion reviewed the many earlier

decision pointing to ‘“‘the obligation of local school author-

ities to take affirmative action.” Following its observation

that Cooper v. Aaron, supra interpreted the Brown decisions

as requiring state authorities “to devote every effort toward

initiating desegregation and bringing about the elimination

of racial discrimination in the public school system’ this

Court made this significant and compelling observation :

“It is these school officials, not the infant plaintiffs or

their parents, who are familiar with the operation of

the school system and know the administrative prob-

lems which may constitute the only legitimate ground

for withholding the immediate realization of consti-

tutionally guaranteed rights.”

12

If this Court’s holding in Bradley 11 (“A system of free

transfers is an acceptable device for achieving a legal deseg-

regation of schools.”) should be limited to the factual situa-

tion in the City of Richmond, then it would not apply here.

New Kent County, having but two schools, offers but one

choice which white parents are likely to take; it offers and

since 1962 has offered to Negro parents a choice between

the (all-Negro) George W. Watkins School and the New

Kent County School which white children attend. Theo-

retically (and according to the plan of the New Kent

County School Board and the plan of the Charles City

County School Board, both submitted to and approved by

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare and the

District Court), the choice for Indian parents in New Kent

County is limited to these two schools. However, according

to an affidavit of Richard M. Bowman dated September

16, 1966 (printed as an appendix hereto), Indian children

are yet being transported by school bus from New Kent

County to Samaria Indian School in Charles City County.

In New Kent, where white and non-white citizens live

in all sections of the county, the maintenance of the George

W. Watkins School as a racially segregated school would

instantly cease if the school authorities would but effect a

geographical division of the county into two areas, each to

be served by one school.

The adoption of “Freedom of Choice” in Charles City

County does not overcome the historical and present fact

that the county has three sets of overlapping, racially ori-

ented, school attendance zones. Depending upon their re-

spective areas of residence, Negro children attend Ruthville

School or Barnetts School. White children, regardless of

their residence, attend Charles City School. Indian children

13

attend Samaria Indian School. Since the provision for free

transfers means nothing to white children or Indian chil-

dren, we have for all practical purposes the dual attendance

zones which were condemned in Jones v. School Board of

the City of Alexandria, supra.

If, on the other hand this Court’s holding in Bradley 11

is not limited to the factual situation in the City of Rich-

mond, then we urge that this Court’s judgment in that case

was vacated and that the Supreme Court expressly held

the subject open for further judicial review (Bradley v.

School Board of the City of Richmond, ...... 1.5....:86 5,

Ct. 224,15 L. ed 2d 187 (1965) ). The purpose and effect of

the arrangements in these counties being to retain racial

segregation, decision here is controlled by Brown I, Bolling

v. Sharpe, Brown 11, Dillard v. School Boar dof the City of

Charlottesville, and Buckner v. County School Board of

Greene County (all hereinabove cited). The instant county

school boards should be enjoined forthwith from maintain-

ing racially segregated schools, there being no adminis-

trative problems to constitute “the only legitimate ground

for withholding the immediate realization of constitutionally

guaranteed rights” (Buckner, supra).

Public Officials Should Be Reminded That

The Time For “Deliberate Speed” Has Expired

When we look at the many areas in community life in

which Americans have accepted the end of the “separate but

equal” farce, we view the confusion which persists with

respect to public schools as tragic. District judges face this

quandary: If, as Bradley II would indicate, school boards

satisfied constitutional requirements by adopting “Freedom

of Choice” conformably with guidelines promulgated by the

14

Department of Health, Education and Welfare then should

the court go further and enjoin the maintenance of racially

segregated schools, or should action seeking such relief be

summarily dismissed? The compromise solution of retaining

the case on the docket without requiring a time table as indi-

cated in Hill v. School Board of the City of Norfolk, 282 F.

2d 473 (1960), promises unending frustration and con-

gested court dockets. Where school boards have discon-

tinued the maintenance of segregated schools, litigation has

ended; e.g., Kilby v. County School Board of Warren

County (W.D. Va. No. 530), final order entered October 7,

1966; Bell v. School Board of the City of Staunton (W. D.

Va. No. 65-C-6-H), final order entered September 14, 1966;

and Kier v. County School Board of Augusta County (W.

D. Va. No. 65-C-5-H), final order entered August 6, 1966.

On November 2, 1966, by a secret ballot, the delegates to

the convention of the Virginia Education Association (pri-

marily composed of white public school teachers) voted

1,229 to 250 to merge with the Virginia Teachers Associa-

tion (composed of Negro school teachers) ; and on the next

day the delegates to the convention of the latter organization

voted 217 to 7 to merge with the former." Thus have Vir-

ginia’s public school teachers demonstrated their under-

standing of the “lesson in democracy” the Brown decision

was intended to be. (Taylor v. Board of Education of New

Roclielle, 191 F. Supp. 181 (S. D. N.Y. 1961))

Simultaneously, and in deplorable contrast, the Virginia

Association of School Administrators (which includes the

121 Division Superintendents of Schools), by an over-

whelming voice vote, condemned and deplored, inter alia,

! Richmond News-Leader, November 3, 1966, page 1; Richmond

Times-Dispatch, November 3, 1966, page 1; Richmond Times-Dis-

patch, November 4, 1966, page 1.

15

the guidelines and regulations of the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare requiring evidence of faculty de-

segregation.” The invasion of their administrative preroga-

tives as perceived by these officials is a difficulty which they

have elected to endure rather than forthrightly end the

maintenance of segregated schools.

“Basic to the remand was the concept that desegregation

must proceed with ‘all deliberate speed,” and the problems

which might be considered and which might justify a decree

requiring something less than wmmediate and total desegre-

gation were severely delimited.” | Emphasis added] Watson

v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S, 526, 331 (1963). “THE

TIME FOR MERE ‘DELIBERATE SPEED HAS

RUN OUT.” Griffin v. County School Board of Prince

Edward County, 377 U.S. 218, 234 (1964). “Delays in

desegregation of school systems are no longer tolerable.”

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, ...... U.S.

Wa 36 85.Ct. 224, 226, 15 1. ed 2d 187, 189 (1965); Rogers

v. Paul, ..... 1S. ....., 36 S.Ct. 358 360, 15 1. ed 24 245,

267 (1965). :

CONCLUSION

It being all too clear that the inherent purpose and effect

of the arrangements adopted by the school boards are to

retain segregation of nonwhite children from others simi-

larly situated, and there being no conceivable legitimate

ground for withholding the immediate realization of rights

which the Constitution guarantees to infants and which in-

fants are incapable of waiving, these cases should be re-

manded with direction that decrees be entered enjoining the

respective school boards from continuing the operation and

2 Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 3, 1966, page B-3; Rich-

mond News Leader, November 3, 1966, page 13.

16

maintenance of any racially segregated public school and

to do so not later than the commencement of the 1967-68

school session.

Respectfully submitted,

S. W. Tucker

Of Counsel for Appellants

S. W. Tucker

Henry L. MarsH, 111

WiLLarp H. DoucLas, Jr.

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Jack GREENBERG

James M. Nasrrr, 111

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Appellants

17

APPENDIX

Affidavit

The affiant is a resident of Charles City County, Virginia

and is one of the parties plaintiff in the action styled Shir-

lette L.. Bowman, et al vs. County School Board of Charles

City County, Virginia, et al., pending in the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Rich-

mond, Division, as Civil Action No. 4265.

During the current (1966-67) school session, particularly

on September 12, 1966, athant observed New Kent County

School Bus No. 33 driven by Kermit Bradley transporting

twelve or more Indian school children from New Kent

County, where they reside, to Samaria School in Charles

City County where they presently attend school with other

children of the Indian Race who live in Charles City County.

Given under my hand this 16th day of September, 1966.

/s/ Ricaarp M. BowMAN

STATE OF VIRGINIA

' CITY OF RICHMOND, to-wit:

Subscribed and sworn to before me, a Notary Public in

and for the City of Richmond, in the State of Virginia, this

16th day of September, 1966.

My commission expires on the 18th day of September,

1969.

NOTARIAL

SEAL

/s/ EvALyN W. SHAED

Notary Public