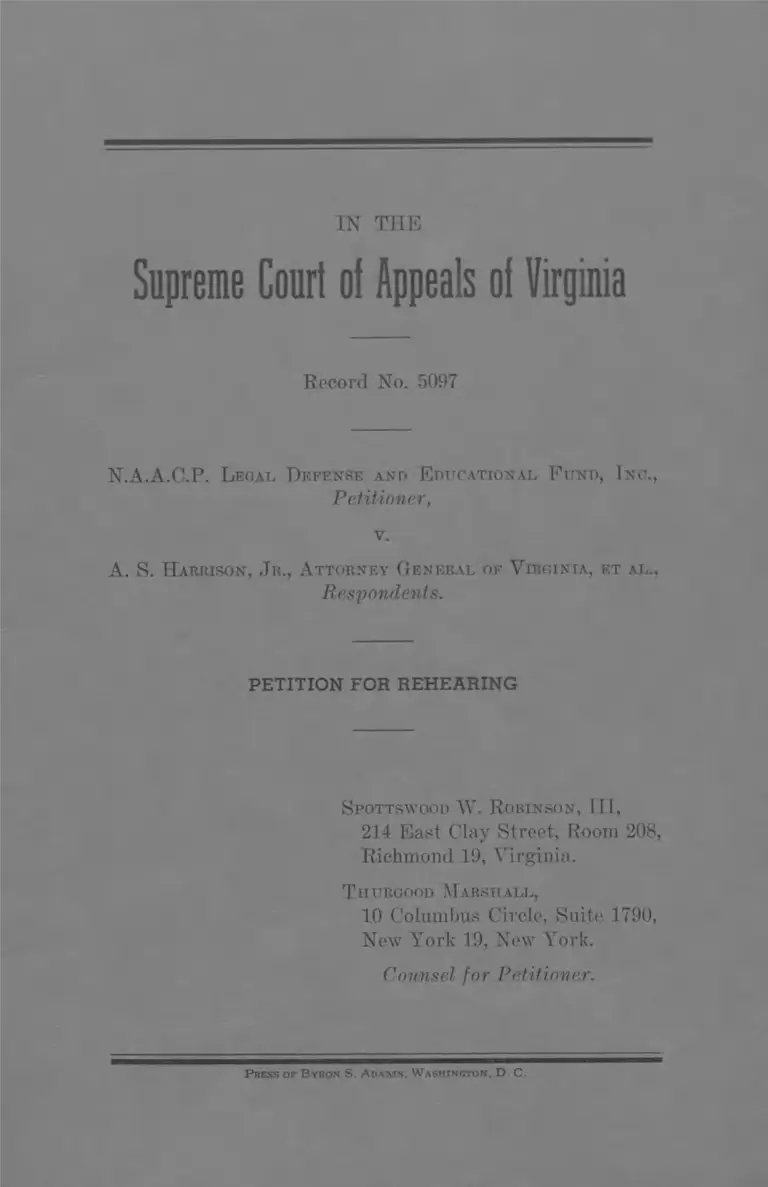

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. v. Harrison Petition for Rehearing

Public Court Documents

September 30, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. v. Harrison Petition for Rehearing, 1960. 5576513a-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/de84039e-176c-4def-a59e-f98477a19900/naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-inc-v-harrison-petition-for-rehearing. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

Record No. 5097

N.A.A.C.P. L egal, D e f e n s e a n d E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , Tn c .,

Petitioner,

v.

A . S . H a r r is o n , J r ., A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l of V ir g in ia , et a l .,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR REHEARING

S po t t sw o o d W. R o b in s o n , III,

214 East Clay Street, Room 208,

Richmond 19, Virginia.

T h u rg o o d M a r s h a l l ,

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 1790,

New York 19, New York.

Counsel for Petitioner.

P ress of B yron S . A d a m s . W ashington . D . C.

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

Statement ............................................................................ 1

Argument ............................................................................ 3

I. The Ruling That Chapter 33 Applies To Peti

tioner’s Activities Is Not Supported By The

Record And Conflicts With The Applicable De

cisional L a w ............................................................ 3

II. The Constitutional Validity Of Chapter 33 Was

Not An Issue Before The Court On This Appeal 9

Conclusion .......................................................................... 10

Certificate ............................................................................ 11

TABLE OF CITATIONS

C ases

Ackerman v. State, 124 Tex. Cr. Rep. 125, 61 S.W. 2d

116 (1933) ....................................................................

Ariola, In re, 252 App. Div. 61, 297 N. Y. S. 100 (1937)

Bayles, Ex parte, 42 Okla. Cr. Rep. 28, 274 P. 485 (1929)

Brown, Re, 389 111. 516, 59 N.E. 2d 855 (1945)..............

Buder, In re, 358 Mo. 796, 217 S.W. 2d 563 (1949) . . . .

Chicago Bar Asso., People ex rel., v. Bamborough, 255

111. 92, 99 N.E. 368 (1912) .......................................

Clark, Re, 161 App. Div. 630, 146 N. Y. S. 1030 (1914)

Colorado Bar Asso., People ex rel., v. Betts, 26 Colo.

521, 58 P. 1091 (1899) ...............................................

Crafts v. Lizotte, 34 R. I. 543, 84 A. 1081 (1912 )..........

Gillespie v. People, 188 111. 176, 58 N. E. 1007 (1900) ..

Gordon v. Coolidge, 10 Fed. Cas. Co. 5,606 (C. C. D.

Me.) ..............................................................................

Government Employees v. Windsor, 353 U. S. 364 ___ 2,

Harris, Re, [1897] 3 Terr. L. R. (Can.) 7 0 ....................

Harrison v. National Association for the Advancement

of Colored People, 360 U. S. 1 6 7 ............................. 4

Helfant, Re, 228 App. Div. 479, 240 N. Y. S. 242 (1930) 6

O

)

(0

0

5

—'

1

05

CT

5C

5

05

O

*

<l

—

3

GO

ii Index Continued

Page

Huff, In re, 371 111. 98, 20 N.E. 2d 101 (1939 ).............. 6

Kelley v. Boyne, 239 Mich. 204, 214 N. W. 316 (1927).. 8

Klingensmith v. Kepler, 41 Ind. 341 (1872), 50 Ind. 432

(1875) ......................................................................... 6

Laird v. State, 156 Tex. Cr. Rep. 345, 242 S.W. 2d 374

(App. 1951) ................................................................ 8

Lawton v. Steele, 119 N. Y. 226, 23 N. E. 878 (1890) . . . 7

Luce, Re, 83 Cal. 303, 23 P. 350 (1890) ......................... 6

McCaughey, Re, [1883] 3 Ont. Rep. 425 ....................... 6

McCloskey, Ex parte, 82 Tex. Cr. Rep. 531, 199 S. W.

1101 (1918), affirmed McCloskey v. Tobin, 252 U. S.

107 (1920) .................................................................. 8

McCloskey v. Tobin, 252 U. S. 107 (1920 ).....................

Maloney, Re, 35 N. D. 1, 153 N. W. 385 (1915 ).............. 6

Marrell, In re, 1 App. Div. 2d 328, 119 N. Y. S. 2d 772

(1956) .......................................................................... 8

Morris, People ex rel., v. Moutray, 166 111. 630, 47 N. E.

79 (1897) .................................................................... 6

Moses, People ex rel., v. Adams, 172 Misc. 143, 14

N. Y. S. 780 (1939) .................................................... 8

Mugler v. Kansas, 123 U. S. 623 (1887) ....................... 7

N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

v. Patty, Civ. No. 2436, reported sub nom National

Association for the Advancement of Colored Peo

ple v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503, vacated Harrison v.

National Association for the Advancement of Col

ored People, 360 U. S. 1 6 7 ....................................... 2

Parkins v. State, 116 Tex. Cr. Rep. 52, 28 S.W. 2d 137

(1930) .......................................................................... 8

People ex rel. Chicago Bar Asso. v. Bamborough, 255

111. 92, 99 N.E. 368 (1912) ....................................... 6

People ex rel. Colorado Bar Asso. v. Betts, 26 Colo.

521, 58 P. 1091 (1899) ............................................... 6

People ex rel. Morris v. Moutrav, 166 111. 630, 47 N. E.

79 (1897) .................................................................... 6

People ex rel. Moses v. Adams, 172 Misc. 143,14 N. Y. S.

2d 780 (1939) .............................................................. 8

People v. Galerson, 276 N. Y. 656, 13 N.E. 2d 47 (1938) 8

People v. Gottleib, 8 Cal. App. 2d 763, 50 P. 2d 509

(1935) 8

People v. Levine,161 i\iisc. 336, 291 N. Y.' S. 1001 (1936) 8

People v. Levy, 8 Cal. App. 2d 763, 50 P. 2d 509 (1935) 8

Page

People v. Meola, 193 App. Div. 487, 184 N. Y. S. 353

(1920) .......................................................................... 8

People v. Winter, 288 N. Y. 418, 43 N.E. 2d 470 (1942) 7, 8

Port Huron v. Jenkinson, 77 Mich. 414, 43 N. W. 923

(1889) .......................................................................... 7

Porter v. Vance, 14 Lea. 629 (Tenn. 1885).................... 6

Priddy v. McKenzie, 205 Mo. 181, 103 S. W. 968 (1907) 6

Rockmore, Re, 130 App. Div. 586, 117 N. Y. S. 512

(1909) .......................................................................... 6

Rosenberg, In re, 413 111. 567, 110 N.E. 2d 186 (1953).. 6

Ross, Re, [1897] 16 Ont. Rep. 482 ................................. 6

Speetor Motor Service v. Walsh, 135 Conn. 37, 61 A. 2d

89 (1948) .................................................................... 9

State v. Breslin, 67 Okla. 125, 369 P. 897 (1917 ).......... 6

State v. Schultz, 242 Iowa 1328, 50 N.W. 2d 9 (1951) .. 7

State v. Strasburg, 60 Wash. 128,110 P. 1027 (1910) .. 7

United States v. Burdett, 9 Pet. 682 U.S. 1835 ............ 7

United States v. Dotterweich, 320 U. S. 277 (1943) . . . 7

Warner v. Griswold, 8 Wend. 665 (N. Y. 1832)............ 6

Worthan v. State, 189 Ala. 395, 66 So. 686 (1914 )___ 8

Yale v. State Bar, 16 Cal. 2d 175, 105 P. 2d 112 (1940) 6

S t a t u t e s

Virginia Acts of the General Assembly, Extra Session

1956:

Chapter 33 .................................................1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9

Chapter 36 .............................................................. 9

Virginia Code (1950):

Sec. 54-74 ................................................................ 1,5

Sec. 54-78 ................................................................ 1

Sec. 54-79 ................................................................ 1

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

Annotated Cases, 1917B, 16-17....................................... 6

Canfield, Corporate Responsibility for Crime, 14 Col.

L. Rev. 469 (1914) ..................................................... 7

Francis, Criminal Responsibility for the Corporation,

18 111. L. Rev. 305 (1924) ......................................... 7

Index Continued iii

IV Index Continued

Page

Gausewitz, Criminal Law—Re Classification of Certain

Offenses as Civil Instead of Criminal, 12 Wis. L.

Rev. 365 (1937) ........................................................ 7

Hall, Principles of Criminal Law 279-322 (1947 )........ 7

Laylin and Tuttle, Due Process and Punishment, 20

Mich. L. Rev. 614 (1922) ........................................... 7

Perkins, Criminal Law 702-703 (1957) ......................... 7

Sayre, Public Welfare Offenses, 33 Col. L. Rev. 55

(1933) .......................................................................... 7

Sayre, Criminal Responsibility for the Acts of Another,

43 Harv. L. Rev. 689 (1930) .................................... 7

IN THE

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

Record No. 5097

N.A.A.C.P. L egal , D e f e n s e a n d E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , I n c .,

Petitioner,

v.

A. S. H a r r is o n , J r ., A t t o r n e y G e n e r a l of V ir g in ia , e t a l .,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR REHEARING

To the Honorable Judges of the

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia:

Petitioner, N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., appellant in the above-styled case, respectfully

represents that it is aggrieved by the opinion and judgment

or decree entered by this Court on the 2nd day of Septem

ber, 1960, affirming so much of a final order of the Circuit

Court of the City of Richmond as declared that Chapter

33 of the Acts of the General Assembly, Extra Session

1956, codified as Sections 54-74, 54-78, 54-79 of the Code

of Virginia of 1950, as amended, 1958 Replacement Volume,

construed in the light of the constitutional contentions

2

theretofore made by petitioner in the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Divi

sion, in a cause captioned N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Incorporated v. Patty, Civ. No. 2436,

and reported sub nom National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503,

vacated Harrison v. N.A.A.C.P., 360 U.S. 167, one, applies

to and prohibits certain of the customary activities of peti

tioner and, two, the evidence shows that petitioner, its

officers and attorneys employed or retained by it or to

whom it may contribute monies or services, are engaged

in the improper solicitation of legal business and employ

ment in violation of Chapter 33.

Upon careful consideration of the opinion and judgment

or decree of this Court in the foregoing particulars, peti

tioner is of the opinion that this Court’s holding thereon

is erroneous and in serious conflict with the decisional

law and legal authorities apposite to the criminal and

disciplinary liability of petitioner, its officers, attorneys

and agent, under Chapter 33 for the conduct and activities

shown by the evidence material and relevant to the issue

raised thereon in the pleadings, particularly to the issue

of fact finally presented. Petitioner also feels obligated,

in any event, to bring to the attention of this Court that

the judgment or decree entered herein against it is errone

ous insofar as it adjudges or decrees that “ Chapter 33,

Acts of Assembly, Extra Session, 1956, is a constitutional

and valid enactment,” because neither petitioner’s plead

ings and prayers in the court below nor assignments of

error and conclusions urged in this Court raised this issue:

rather, petitioner merely sought a construction of the Act

“ in the light of constitutional objections presented in the

[Federal] District Court.” cf. Government Employees v.

Windsor, 353 U.S. 364, 366. These considerations constrain

petitioner to present this petition for rehearing and for

the vacation or modification of the aforesaid holding and

judgment or decree.

3

ARGUMENT

I

The Ruling Thai Chapter 33 Applies to Petitioner's Activities

Is Not Supported by the Record and Conflicts With the

Applicable Decisional Law

Chapter 33 was elaborately analyzed in the petition for

appeal (pp. 26-28, 35-37). That analysis, briefly put, was

that petitioner’s conduct could not violate Chapter 33 unless

it amounted to an improper solicitation of business for an

attorney or for itself; and, unless either petitioner or its

regional counsel in Virginia improperly solicited business,

Chapter 33 is inapplicable. With this, the Court appears

to agree: the provisions of Chapter 33 “ deal with solicita

tion of any legal or professional business or employment,

either directly or indirectly,” (Opinion, p. 15), and, to the

extent that the former law was amended, the Act “ broadens

the offense specified which theretofore made it unlawful

for any person, corporation, partnership or association

to act as a runner or capper for an attorney at law or to

solicit any business for him, to make it unlawful for a

person, association or corporation to solicit any business

for an attorney at law or any other person, corporation

or association” (Id., p. 17).

The Court, however, considering the evidence material

and relevant to issues raised as to Chapter 33 on the plead

ings, particularly the final issue of fact presented, con

cluded that petitioner’s conduct violated Chapter 33. And,

therefore, petitioner submits that the record does not sus

tain this conclusion.

At the outset, it should be said that any assumption that

petitioner supplies services or monies in all Virginia litiga

tion in which the N.A.A.C.P. is interested or identified goes

beyond the record herein. In those litigations which the

record shows that petitioner rendered services or monies,

or both, the evidence is as follows:

4

In the Prince Edward County school case, the firm of

which the regional counsel was then a member was con

tacted directly by the parties who by written authorizations

directly employed the firm as counsel (ft. 120; PI. Ex. R-9,

p p . 211-215) ;*

In the Norfolk school case, three attorneys were directly

engaged by the parties with authority to enlist other

counsel, pursuant to which the regional counsel was by

them associated (R. 114-115; PI. Ex. R-9, p. 219);

In the Newport News school case, two attorneys were

directly retained by the parties and authorized to associate

other counsel, and the Fund’s regional attorney associated

with them at their request (R. 107, 137, 139, 141, 144, 148,

151, 152, 156, 162, 164, 209; PI. Ex. R-9, p. 219);

In the Arlington school case, the Fund’s regional counsel

came into the case on request from counsel directly re

tained by the parties pursuant to authority from the clients

to associate additional counsel (R. 116-118, 166-167, 173,

176, 179, 185-186; PI. Ex. R-9, p. 220);

In the Charlottesville school case, counsel directly en

gaged by the parties associated, pursuant to authority so

to do, additional counsel of whom the Fund’s regional

counsel was one (R. 110, 192, 196, 199, 202, 204, 206; PL

Ex. R-9, pp. 216-219);

In the Warren County school case, the Fund’s regional

counsel, on request of the attorney directly employed by

the parties, associated with him (R. 130).

The executive secretary of the State Conference testified

that he did not refer any of the parties to these cases to

* References “ R. .. ” are to the record in this case, and those ‘ ‘ PI. Ex. 9,

p. are to the printed record in Harrison v. National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People, 360 U.S. 167, which is Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 9

in the record in this case. All such references are to the page numbers

printed in the upper left and right corners of the page rather than to the

original page numbers.

5

the Conference’s legal staff but that, rather, the parties

directly employed their counsel (R. 62-63). Nor is there

evidence to suggest that petitioner brought about the em

ployment by the parties of the attorneys they selected.

Petitioner submits that the record is devoid of evidence

upon which it might be concluded that there was solicitation

in any of these cases either by it or by its regional counsel.

In each instance the employment of initial counsel was

direct, in one such instance its regional counsel was one

of those directly employed, and in the others he associated

at the request of the parties’ attorneys expressly or im

plicitly authorized to request his association (PI. Ex. R-9,

pp. 334, 388). This was in line with petitioner’s general

policy by which assistance is not afforded unless and until

the party or his personally-retained attorney specifically

requests it (PI. Ex. R-9, pp. 253, 270-271, 272, 280, 290, 319).

Petitioner further submits that the conclusion that it

has violated the statute is not supported by the evidence.

It is not shown that its regional attorney solicited employ

ment in any case, or accepted compensation from anyone

except petitioner, or accepted employment from anyone

except the parties in consequence either of direct engage

ment by them or association at the request of their retained

counsel. Nor is it shown that petitioner participated in

any way save to afford assistance to the litigation after

counsel had been engaged.

The record does not establish impropriety on the part of

counsel directly engaged insofar as their employment is

concerned. Even if there were, there is no evidence indica

tive of knowledge thereof by petitioner or its counsel.

Such knowledge would be essential to the conclusion that

the statute was violated, Sec. 54-74(6), and to any con

clusion that its assistance was otherwise improper.

Whoever may have violated Chapter 33, assuming pro

arguendo that someone is blameworthy, the record surely

6

sustains no conclusion other than that petitioner and its

regional attorney in Virginia have not violated it and are

blameless.

Of course, it has long been true that each member of a

law firm, irrespective of whether he participated in or

knew of the transaction, is civilly liable to a client for the

misconduct of any of the firm’s members within the scope

of their authority. See, e.g., Warner v. Griswold, 8 Wend.

665 (N.Y. 1832); Gordon v. Coolidge, 10 Fed. Cas. No.

5,606 (C.C.D. Me., per Justice S tory ); Priddy v. McKenzie,

205 Mo. 181, 103 S.W. 968 (1907); Anno: Ann. Cas. 1917B,

16-17. But it is also well settled that one member of a

law firm is not subject to disbarment or discipline because

of the misconduct of any member without knowledge of,

or consent to or participation in, the transaction. Compare

Klingensmith v. Kepler, 41 Ind. 341 (1872), 50 Ind. 432

(1875); Porter v. Vance, 14 Lea. 629 (Tenn. 1885); Re Luce,

83 Cal. 303, 23 P. 350 (1890); Re Rockmore, 130 App. Div.

586, 117 N.Y.S. 512 (1909); Re Clark, 161 App. Div. 630,

146 N.Y.S. 1030 (1914); In re Maloney, 35 N.D. 1, 153 N.W.

385 (1915); State v. Rreslin, 67 Okla. 125,169 P. 897 (1917);

In re Huff, 371 111. 98, 20 N.E. 2d 101 (1939) and Yale v.

State Bar, 16 Cal. 2d 175, 105 P. 2d 112 (1940)1 with

People ex rel Colorado Bar Asso. v. Betts, 26 Colo. 521,

58 P. 1091 (1899); People ex rel. Morris v. Moutray, 166

111. 630, 47 N.E. 79 (1897); People ex rel. Chicago Bar Asso.

v. Bamborough, 255 111. 92, 99 N.E. 368 (1912); Re Helfant,

228 App. Div. 479, 240 N.Y.S. 242 (1930); Re Brown, 389

111. 516, 59 N.E. 2d 855 (1945); In re Buder, 358 Mo. 796,

217 S.W. 2d 563, 576 (1949); and In re Rosenberg, 413 111.

567, 110 N.E. 2d 186 (1953). Similarly, where attorneys,

although not general partners, are associated together,

one is not subject to disciplinary sanctions because of an

associate’s misconduct unless he has knowledge of or par

1 See also Re MeCaughey [1883] 3 Ont. Rep. 425; Re Ross [1895] 16 Ont.

Rep. 482; Re Harris [1897] 3 Terr. L. R. (Can.) 70.

7

ticipates in it. Compare Crafts v. Lizotte, 34 R. I. 543,

84 A. 1081 (1912) with In re Ariola, 252 App. Div. 61, 297

N.Y.S. 100 (1937).

Moreover, since in Anglo-American jurisprudence crimi

nal liability is essentially personal and individual and is

also dependent upon proof of individual causation, the

doctrine of liability without fault or “ strict liability”

has never been accepted in criminal law except with regard

to a limited species of offenses variously classified as

public welfare or regulatory or civil offenses. Sayre, Crimi

nal Responsibility for the Acts of Another, 43 Harv. L. Rev.

689, 720 (1930); Sayre, Public Welfare Offenses, 33 Col.

L. Rev. 55 (1933); Gausewitz, Criminal Law—Re Classifica

tion of Certain Offenses as Civil Instead of Criminal, 12

Wis. L. Rev. 365 (1937); Hall, Principles of Criminal Law

279-322 (1947). And even the application of “ strict lia

bility” to such offenses is unreasonable, unjust and con

stitutionally suspect. Mugler v. Kansas, 123 U.S. 623, 661

(1887); United States v. Dotterweich, 320 U.S. 277, 285-286

(1943, dissenting opinion); Ex parte Rales, 42 Okla. Cr.

Rep. 28, 274 P. 485, 486 (1929); State v. Strasburg, 60

Wash. 128, 110 P. 1027 (1910); Gillespie v. People, 188 111.

176, 58 N.E. 1007 (1900); Lawton v. Steele, 119 N.Y. 226,

23 N.E. 878 (1890); Port Huron v. Jenkinson, 77 Mich.

414, 43 N.W. 923 (1889). See also State v. Schultz, 242

Iowa 1328, 50 N.W. 2d 9 (1951); Canfield, Corporate Re

sponsibility for Crime, 14 Col. L. Rev. 469, 480 (1914);

Francis, Criminal Responsibility for the Corporation, 18

III. L. Rev. 305 (1924); Laylin and Tuttle, Due Process and

Punishment, 20 Mich. L. Rev. 614 (1922). Cf. United States

v. Rurdett, 9 Pet. 682 (U.S. 1835); People v. Winter, 288

N.Y. 418, 43 N.E. 2d 470 (1942). Indeed, in view of these

latter considerations, it is not surprising that the direct

or indirect solicitation of legal or professional business

does not fall within the eight categories of offenses for

which criminal sanctions are imposed under the doctrine of

strict liability. See Perkins, Criminal Law 702-703 (1957).

8

Nor is it surprising that there are only a handful of prose

cutions revealed in the reported decisional law of the

thirty-odd states with statutes which make it a criminal

offense for attorneys or others, or both, to solicit legal

business for an attorney or themselves.2 See Worthan v.

State, 189 Ala. 395, 66 So. 686 (1914); People v. Gottleib

{People v. Levy) 8 Cal. App. 2d 763, 50 P. 2d 509 (1935);

Kelley v. Boyne, 239 Mich. 204, 214 N.W. 316 (1927);

People v. Galerson, 276 N.Y. 656, 13 N.E. 2d 47 (1938);

People ex rel. Moses v. Adams, 172 Misc. 143, 14 N.Y.S.

2d 780 (1939); People v. Levine, 161 Misc. 336, 291 N.Y.S.

1001 (1936); People v. Meola, 193 App. Div. 487, 184

N.Y.S. 353 (1920); People v. Winter, 288 N.Y. 418, 43

N.E. 2d 470 (1942) ;3 Ex parte McCloskey, 82 Tex. Cr.

Rep. 531, 199 S.W. 1101 (1918), affirmed McCloskey v.

Tobin, 252 U.S. 107 (1920); Ackerman v. State, 124 Tex.

Cr. Rep. 125, 61 S.W. 2d 116 (1933); Laird v. State, 156

Cr. Rep. 345, 242 S.W. 2d 374 (1951); Parkins v. State,

116 Tex. Cr. Rep. 52, 28 S.W. 2d 137 (1930), and none of

these cases was sustained on the merits absent a record

which clearly established actual knowledge, consent or

participation in the solicitation of such business or em

ployment. Were this not the case, petitioner, in the light

of the authorities cited above, suggests that the consti

tutionality of this legislation would not have been upheld

in the Galerson, Kelley, Adams and McCloskey cases, supra.

Therefore, petitioner submits, the Court’s ruling that

Chapter 33 applies to petitioner’s activities is not sup

ported by the record herein and conflicts with applicable

decisional law and apposite authorities.

2 Alabama, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii,

Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota,

Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New

Jersey, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon,

Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia,

Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming.

3 Cf. In re Marrell, 1 App. Div. 2d 328, 149 N.Y.S. 2d 772 (1956).

9

II

The Constitutional Validity of Chapter 33 Was Not An Issue

Before the Court on This Appeal

In its opinion, the Court concluded that “ chapter 33

is a valid regulation of the practice of law, enacted under

the police power of the State, and is not violative of any

constitutional restrictions,” and, in its judgment or decree,

affirmed the order appealed from “ in so far as it holds

that Chapter 33, Acts of Assembly, Extra Session, 1956, is

a constitutional and valid enactment.” Petitioner submits

that the Court erred in making such determination as to it.

The history of this litigation in the Federal District

Court, prior to institution of suit in the court below, is

set forth in the petition for appeal herein (pp. 2-3). As

was then pointed out, the District Court entered judgment

retaining jurisdiction as to Chapters 33 and 36 pending

interpretation of these laws by the courts of Virginia. For

this purpose only, suit was brought in the court below.

Conformably to Government Employees v. Windsor, 353

TJ.S. 364, petitioner sought construction of the laws in

the light of its constitutional contentions made in the

District Court.

Neither in its pleadings nor in its prayers did petitioner

present the question whether Chapter 33 is constitutionally

valid; that issue it left for future decision by the District

Court. For this reason, the court below made no ruling

or adjudication on this question (R. 31). Nor was the

issue raised by the assignment of error or conclusions

presented to this Court. (R. 51-54). The function of this

Court was therefore limited to interpretation of the laws

in question, leaving to the District Court decision on all

other issues, Spector Motor Service v. Walsh, 135 Conn.

37, 61 A. 2d 89, 92,105 (1948), and it is therefore submitted

that, in any event, the opinion and judgment or decree of

this Court should be modified accordingly.

10

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, petitioner prays that this

Court will review and rehear this case, and vacate or

modify its decision and its judgment or decree herein in

the particulars specified in this petition.

Respectfully submitted,

N.A.A.C.P. L e g a l D e f e n s e an d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d , I n c .

By: S po t t sw o o d W. R o b in s o n , III,

214 East Clay Street, Room 208,

Richmond 19, Virginia.

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l ,

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 1790,

New York 19, New York.

Counsel for Petitioner.

11

CERTIFICATE

I hereby certify that on the 30th day of September, 1960,

three copies of the foregoing petition for rehearing were

mailed, with first class postage prepaid, to each of the fol

lowing persons at their respective addresses shown:

David J. Mays, Esquire,

Counsel for Respondents,

State-Planters Bank Building,

Richmond, Virginia.

Henry T. Wickham, Esquire,

Counsel for Respondents,

State-Planters Bank Building,

Richmond, Virginia.

Honorable Albertis S. Harrison, Jr.,

Attorney General of Virginia,

Supreme Court Building,

Richmond, Virginia.

S po tt sw o o d W. R o b in s o n , III,

Of Counsel for Petitioner

.