Fullilove v. Kreps Brief for the Asian American Legal Defense Fund as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Fullilove v. Kreps Brief for the Asian American Legal Defense Fund as Amicus Curiae, 1979. 32be6b78-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/deb2bfd4-9468-477a-aa63-147899c650ab/fullilove-v-kreps-brief-for-the-asian-american-legal-defense-fund-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

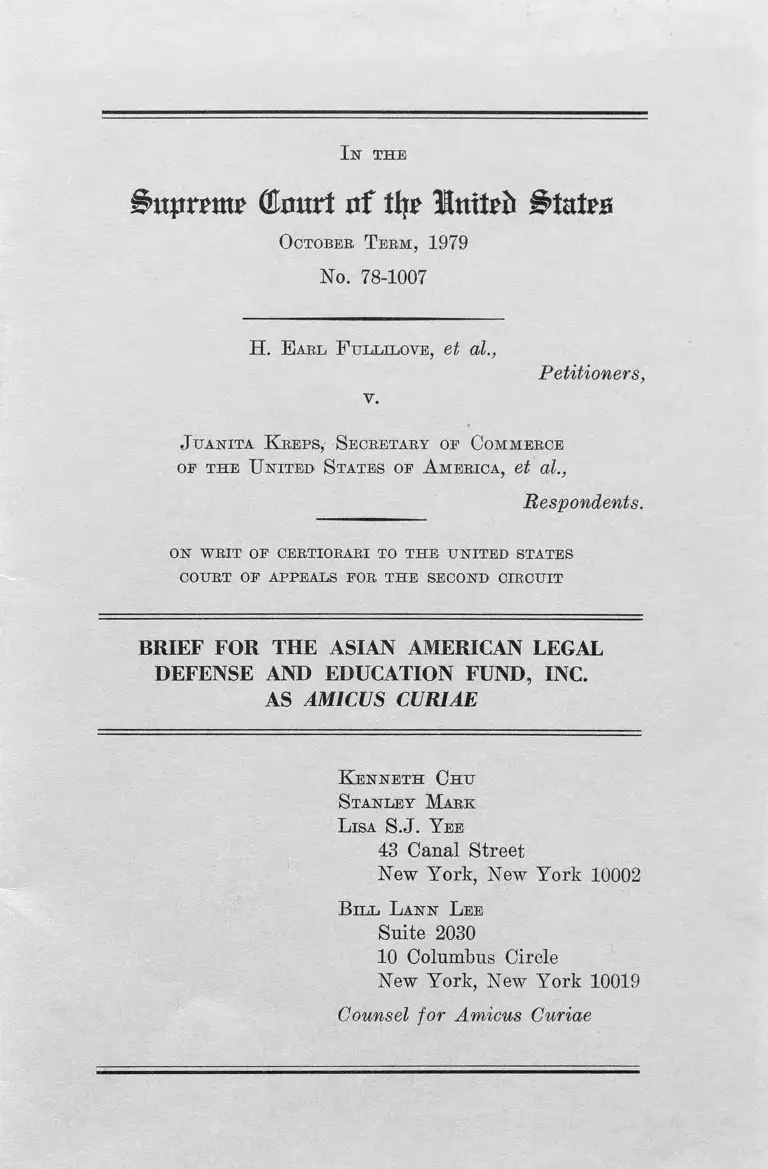

In t h e

Supreme (Emtri of thr Httttrii States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1979

No. 78-1007

H. E a r l F u l l il o v e , et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

J u a n it a K r e p s , S e c r e t a r y o f C o m m e r c e

OE THE UNITED' STATES OE AMERICA, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OE CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC.

AS AMICUS CURIAE

K e n n e t h C h u

S t a n lea ' M a r k

L is a S.J. Y e e

43 Canal Street

New York, New York 10002

B il l L a n n L e e

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

“ X-

INDEX

Page

Interest of Amicus ............. . 2

Summary of Argument ................ ..... 3

Argument:

I. The Purpose of the Set-Aside

Provision is to Redress the

Exclusion of Minority Busi

nesses, Including Asian Amer

ican Enterprises , from the

Mainstream of American Eco

nomic Life. .... . 3

II. Asian Americans are Still

Subject to the Vestiges of

Prior Economic Discrimina

tion Imposed by Law. ......----- 12

III. The Set-Aside Provision of

the Public Work Employment

Act of 1977 is a Necessary

and Proper Means of Pro

moting the Development of

Minority Businesses. ...... 17

Conclusion 22

-Xi~

Table of Authorities

Cases;

T. Abe v. Fish and Gains Gamin,

9 Cal. App.2d 300, 49 P.2d 608

(1935) ® ........ .........a. 16

Cockrill v. California, 268 U.S. 258

(1924) ...................... ....... 15

Frick v. Webb, 263 U.S. 326 (1923) ...... 15

Fullilove v. Kreps, 584 F.2d 600

(2d Cir. 1978) ......... . 7,21

In re Hong Yen Chang, 84 Cal. 163

(1890) ................ ........----.... 14

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641

(1966) ••••••»••*••••••»••••••«••*••.•• 19

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) ..... 19

Oyarna v. State of California,

332 U.S. 633 (1948) ........... . 15

Slaughter House Cases, 83 U.S. 36

(1873) ___ .......................----- 20

Takahashi v. Fish and feme Ccnnin,

334 U.S. 410 (1948) ................. 16

Terrance v. Thetipson, 263 U.S. 197

(1923) ................... .......... ... 15

The Chinese Exclusion Case,

130 U.S. 581 (1889) .............. 14

Page

- l i i -

Page

United States v. Operating Engineers,

4 F.E.P. Cases 1088 (N.D. Cal. 1972) .. 11

United States v. Wong Kim Ark,

169 U.S. 649 (1898) ..... ............ 20

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber,

_U.S. , 99 S. Ct. 2721 (1979) ...10,20,21

University of California Regents

v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978) .....___ 17,20

Webb v. O'Brien, 263 U.S. 313

(1923) ........................ 15

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356

(1886) ....... 12,13,14

Constitutions, Statutes and Regulations:

Chinese Exclusion Act, 22 Stat. 58

(1882) ........................ 14

Public Works Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C.

§ 6709 ......... 4

Public Works Employment Act of 1977,

42 U.S.C. §§ 6701 et seq. ...... ..3,4,18

Small Business Act of 1958, 15 U.S.C.

§ 637(a), as amended (1978) ........... 5

S. 1647, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. (1979) ... 16

California Const, of 1879, art. XIX,

§§ 2-3 14

Foreign Miners* License Tax, Act of

Apr. 13, 1850, ch. 97,§§ 1 et seq.

1850 Cal. Stat. 221 ................. . 13

Idaho Const, of 1890, art. 13, § 5 ..... 14

Municipal Reports, 1871-72 ........ — ... 13

Other Authorities:

P. Chiu, Chinese Labor in California,

1850-1880 (1967) ...................... 13

F. Chuman, The Bamboo People: The Law

and Japanese Americans (1976) ......... 12,16

123 Cong. Rec. H 1436-40 (daily ed.

Feb. 24, 1977) ........................4,5,6,10

123 Cong. Rec. S 3910 (daily ed. Mar.

10, 1977) ................... 4,5,6,18,19

M. Coolidge, Chinese Irnmigratian (1909).. 12,13

R. Daniels, The Politics of Prejudice (1962) 15

S. Doctors and A. Huff, Minority Enter-

prise and the President's Council

(1973) ............................... 6

Executive Order 9066 (1942), rescinded

Feb. 19, 1976 ......................... 16

Executive Order 11458 (1969), superseded

Oct. 13, 1 9 7 1 ...... 5

Ferguson, The California Alien Land Law

and the Fourteenth Amendment, 35 Cal.

L. Rev. 61 (1947)

-iv-

Page

15

~v~

Hearings Before the Subccrnm. on Economic

DeveToptient of the House Ccarni. on

Public Works and Transportation, 95th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1977) ........... 4

House Subcesmi, on Small Business Admin.

Oversight and Minority Business

Enterprise, Sumrrary of the Activities

of the Cornu on Small Business, 94th

Cong. (1976) ..................... . 7

Y. Ichihashi, Japanese in the United

States (1932) ...... ................ . 15

Page

H. Kitano, Japanese Americans; The

Evolution of a Subculture (1969) .... 15

M. Konvitz, The Alien and the Asiatic

in American Law (1946) ......... 15

I. Light, Ethnic Enterprise in America;

Business and Welfare Among Chinese,

Japanese and Blacks (1972) ..... . 13

S. Lyman, The Asian in the West (1970).. 13,14

S. Lyman, Chinese Americans (1974) .... 13

McGovney, The Anti-Japanese Land Laws

of California and Ten Other States,

35 Cal. L. Pev. 7 (1947) ............ 15

P. Murray, States' Laws on Race and

Color (1951) ... ............... ...... 12 -

New York State Advisory Cornea., U.S.

Ccrren'n on Civil Rights, The Forgotten.

Minority: Asian Americans in New

York City (1977) ................. . 11

-VI-

E. Sandmsyer, The Anti-Chinese Movenent

in California (1939) ................ 12,13,14

Page

U.S. Dept, of Ccranerce, Bureau of the

Census, Minority-Owred Business:

1969 (1971) ..... ........... ........ 8

U.S. Dept, of Ccranerce, Bureau of the

Census, 1972 Survey of Minority-

Owned Business Enterprises, Minority-

Owned Business, MB 72-4 (1975) ...... 8

U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of the

Census, 1972 Survey of Minority-

Owned Business Enterprises, Minority-

Owned Businesses: Asian Americans,

American Indians, and Others, MB

72-3 (1975) ........... ........... . 8

U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Economic

Development Admin., Guidelines for

10% Minority Business Participation

in Local Public Works Grants (1977).. 19

U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Office of

Minority Business Enterprise,

.Report of the Task Force on Edu

cation and Training for Minority

Business Enterprise (1974) .......... 6,8,9

U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Office of

Minority Business Enterprise, Amsun

Associates, Socio-Economic Analysis

of Asian American Business Patterns

(1977) ............... ............... 8,10

U.S. Goran1 n on Civil Rights, Minorities

and Women as 'Government Contractors

(1975) ..... ............... ......... 6,10

-vil

li. S. Dept, of Health, Education &

Welfare, Urban Associates, Inc.,

A Study of Selected Socio-Economic

Characteristics of Ethnic Minorities

Based on the 1970 Census, Vol. II;

Aslan Americans (1974) (HEW Publ.~

No. (OS) 75-121) ............... ......

U.S. Dept, of Labor, Manpower Admin., R.

Glover, Minority Enterprise in

Construction (1977) ..................

U.S. Dept, of Transportation, Federal

Highway Admin., F. Wu, P. Chen, Y.

Okano, P. Woo, Involvement of Asian

Americans in Federal-Aid Highway

Construction (1978) ..................

U.S. General Accounting Office, Minority

Firms on Local Public Works Projects

— Mixed Results (1979) ..............

Page

17

10

11

10,18

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1979

No. 78-1007

H. EARL FULLILOVE, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

JUANITA KREPS, SECRETARY OF COMMERCE

OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE ASIAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATION FUND, INC. AS

AMICUS CURIAE

Interest of Amicus

The Asian American Legal Defense and Education

Fund is a non-profit corporation established under

the laws of the States of California and New York

in 1974 in order to assist Asian Americans through

out the nation in 'the protection of their civil

rights through the prosecution of lawsuits and the

dissemination of public information. Amicus has

found that much of its work concerns discrimina

tion on the basis of race and national origin in

the job market and economic opportunity generally

as a result of the historic exclusion of Asians

from the mainstream of American business life and

the legacy of overt economic discrimination sanc

tioned by law. It is the experience of amicus

that affirmative action programs such as the Con

gressional minority business enterprise set-aside

program upheld by the court below are necessary

to overcome burdens on equal opportunity for Asian

*

Americans.

-2-

*The parties have consented to the filing of this

brief amicus curiae, and letters of consent have

been filed with the Clerk.

-3-

SUMMAKY OF ARGUMENT

The minority set-aside provision of the Public

Works Employment Act of 1977 was enacted as a

means of bringing minority businesses, including

Asian American enterprises, into full and equal

participation in the economic life of the nation.

The legislation is one of a set of recent Congres

sional programs specifically designed to redress

documented discriminatory exclusion of minority

firms from dominant business activity. This ex

clusion of Asian Americans, as is true of other

racial minority groups, is a vestige of prior le

gal restraints which limited and relegated Asians

to marginal areas of economic endeavor. It was

therefore appropriate for Congress to take steps

to overcame the continuing effects of prior dis

crimination in an area of great national concern

pursuant to the enforcement powers conferred by

the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.

ARGUMENT

I. THE PURPOSE OF THE SET-ASIDE PROVISION

IS TO REDRESS THE EXCLUSION OF MINORITY

BUSINESSES, INCLUDING ASIAN AMERICAN

ENTERPRISES, FROM THE MAINSTREAM OF

AMERICAN ECONOMIC LIFE.

The Public Works Employment Act of 1977, 42

U.S.C. §§ 6701 et seq., was passed by Congress as

-4-

an antirecession measure targeted for areas of

high unenployment. Section 103(f)(2) of the Act,

42 U.S.C. § 6705(f)(2), provides, in pertinent

part, that "no grant shall be made under this chap

ter for any local public works project unless the

applicant gives satisfactory assurance to the Sec

retary that at least 10 per centum of the amount

of each grant shall be expended for minority busi

ness enterprises," i.e., enterprises owned in sub

stantial part by "citizens of the United States

who are Negroes, Spanish-speaking, Orientals, In

dians, Eskimos, and Aleuts." The set-aside provi

sion was proposed "to strengthen the nondiscrimi

nation provision contained in the ...Act", section

110 of the Public Works Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. §

6709, — ^in order (a) to provide minority business

es "a fair share" of construction contracts and

related business to be generated by the Act-/ and

(b) to fight unenployment in minority areas.—/

1. Hearings Before the Subcoirm. on Economic De-

velopment of the House Comm, on Public Works and

ihransportation, 95th Cong., lst~Siis.V 939

(1977)(Rep. Conyers).

2. 123 Cong. Rec. H 1436 (daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977)

(Rep. Mitchell).

3. 123 Cong. Rec. S 3910 (daily ed. Mar. 10, 1977)

(Sen. Brooke); 123 Cong. Rec. H 1440 (daily ed. Feb.

24, 1977)(Rep. Biaggi).

-5-

The proponents of the legislation nade clear

that the set-aside provision m s part and parcel

of a decade of substantial federal efforts to en

courage minority business through direct grants,

loans, loan guarantees, and procurement of goods

and services.—^ On March 5, 1969, President Nixon

issued Executive Order 11458 which established the

Office of Minority Business Enterprise under the

Department of Comerce to develop and coordinate

expanded federal efforts. The agency with the

greatest implementation responsibility was the

Small Business Administration ("SBA"), which in

1972 spent over one-half of federal funds allo

cated for minority business assistance. Among the

programs administered by the SBA is a set-aside

program for minority federal procurement contracts

pursuant to section 8 (a) of the Small Business Act,

15 IJ.S.C. § 637(a), vhich was specifically cited

as precedent for the public works act set-aside

5/provision.— Other federal agencies with programs

to assist minority businesses, including, in sore

.instances, set-aside programs, were the Commerce

4. See, e.g,, 123 Cong. Pec. H 1437 (daily ed.

Feb. 24, 1977)(Rep. Mitchell); 123 Cong. Rec. S

3910 (daily ed. Mar. 10, 1977)(Sen. Brooke).

5. Id.

—6—

Department’s Economic Development Administration,

the Department of Housing & Urban Development, the

Department of Health, Education & Welfare, the

Department of the Interior, the Department of

Transportation, and the Federal Aviation Adminis

tration, as well as state and local agencies.—^

Indeed, the public works set-aside provision

was expressly intended to supplement and strength

en existing federal minority business programs.—^

Representative Mitchell, the author of the provi

sion, pointed out that only 1 percent of all govern

ment contracts went to minority businesses and that

existing federal programs had not yet been able to

increase the amount.—^ Congress was well aware of

6. See, U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Office of Minor

ity Business Enterprise, Report of the Task Force

cn Education and Training for Minority Business

Enterprise 47-75 (1974) (hereinafter "OMBE Task

Force Report"); U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights, Mi-

norities and Wcroen as Government Contractors 102-

104 (1975); see also, S. Doctors & A. Huff, Mi

nority Enterprise and the President's Council 17- 30 (19?3)-

7. 123 Cong. Rec. H 1436-37 (Rep. Mitchell),

H 1440 (Rep. Biaggi) (daily ed. Feb. 24, 1977);

123 Cong. Rec. S 3910 (daily ed. Mar. 10, 1977)

(Sen. Brooke).

8. Id.

-7-

the need for the legislation because the problem

of "a business system which has traditionally ex

cluded measurable minority participation” was

fully documented in reports of federal agencies

with responsibilities for promoting minority busi-

■ 9/ness.— Thus, while minority persons were 17 per-

9. See, e.g., House Subcoran. on Small Business

Admin. Oversight and Minority Business Enterprise,

Summary of Activities of the Comm, on Snail Busi

ness, 94th Cong., 182-183 (1976):

"The very basic problem.. .is that,

over the years, there has developed a

business system which has traditionally

excluded measurable minority partici

pation. In the past mare than the pre

sent, this system of conducting busi

ness transactions overtly precluded mi

nority input. Currently, we more often

encounter a business system which is

racially neutral on its face, but be

cause of past overt social and economic

discrimination is presently operating,

in effect, to perpetuate these past in

equities. Minorities, until recently

have not participated to any measurable

extent, in our total business system

generally, or in the construction in

dustry, in particular. However, in

roads are now being made and minority

contractors are attempting to 'break-

into' a mode of doing things, a system,

with which they are empirically unfamil

iar and which is historically unfamil

iar with them."

Cited by the court below, 584 F.2d 600, 606 (2d

Cir. 1979).

-8-

cent of the nation’s population, they control only

4 percent of the total number of business enter

prises, Gross receipts of all minority-owned busi

nesses in 1969 were less than 1 percent of the to

tal receipts for all American businesses and

roughly equal to the 1972 sales of the General

Electric Company alone, .and the combined assets of

minority-owned businesses equalled 0,3 percent of

all business assets in 1971.— ^

The situation of Asian American business enter

prises is comparable to that of other minority

firms. Asian American businesses comprise 0.5

percent of total businesses, and the typical Asian

American business is a sole proprietorship without

paid employees engaged in. retail trade or person

al service with annual gross receipts of under

$25,000.— ^ One-third of all Asian American firms

10. OMBE Task Force Report at 17-19; see general

ly, U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of the Census,

Minority-Owned Business: 1969 1-2 (1971); U.S.

Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, 1972 Sur-

vey of Minority-Owned Business Enterprises, Minor-

ity-Qwned Business, MB 72-4 (1975) . ~~ ' ~ ~ ~

11. U.S. Department of Commerce, Office of Minor

ity Business Enterprise, Amsun Associates, Socio-

Economic Analysis of Asian American Business Pat

terns 5-26 (1977) (hereinafter "OMBE Study")-*- see

generally, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of

the Census, 1972 Survey of Minority-Owned Busi

ness Enterprises, Minority-Owned Easinesses: Asian

Americans, American Indians, and Others (1975).

-9~

had less than $5,000 in gross receipts in 1972,

and a little over two-thirds had gross receipts

of under $25,000. 63 percent of all Asian Amer

ican firms are engaged in retail trade and person

al service (which includes laundry, cleaning

and garment services, barber shops, beauty shops,

etc.) business. The nearly 90 percent of Asian

American businesses that are sole proprietorships

account for only about one-half of the receipts of

all Asian American businesses. More than three-

fourths of Asian American businesses operate with

out paid employees. In 1972, 61 percent of all

Asian American employer firms had less than five

employees and 99 percent had less than fifty em

ployees; the 0.5 percent of Asian American employ

er firms which had more than 100 employees are

still considered small businesses by the SBA.

In particular, Asian American construction con

tractors are typical of minority contractors.

Specific problems of minority construction con

tractors were cited in the debate on the public

works set-aside provision: Minority firms could

not compete successfully against the older,

larger, and more established non-minority firms,

and minorities we re unfamiliar with bidding pro

cedures and often needed assistance in handling

the administrative work required under federal

-10-

contracts.— ^ Only 4 percent of Asian American

businesses are engaged in construction work in

contrast to 10 percent of all American businesses.

Average receipts per Asian American firm were half

of total American firms, and three-quarters of the

Asain American construction businesses were sole

proprietorships with no paid employees. Employer

firms are small, averaging eight employees per

firm.— /

The degree of discrimination encountered by

minorities in the construction industry is so

great that it had "(j)udicial findings of exclu

sion from crafts on racial grounds are so numerous

as to make such exclusion a proper subject for

judicial notice". United Steelworkers of America

v. Weber, __U.S.___, 99 S. Ct. 2721, 2725 n.l

(1979) . Asians, like other minorities, have been

unable to enter skilled trades in the construction

12. 123 Cong. Rec. H 1437 (Rep. Mitchell), H 1439

(Rep. Karsha), H 1440 (Rep. Conyers) (daily ed.

Feb. 24, 1977); see generally, U.S. Conm'n on Civil

Rights, Minorities and Women as Government Contract

ors (1975); U.S. Dept, of Labor, Manpower Admin.,

R. Glover, Minority Enterprise in Construction

(1977); U.S. Gen'1 Accounting Office, Minority

Firms On Local Public Works Projects— Mixed Results

(1979).

13. OMBE Study at 39, 52-53.

-11-

industry in any appreciable numbers in areas of

substantial Asian population because of racially

exclusionary policies of construction unions;

indeed, they are practically invisible, see, e.g.,

United States v. Operating Engineers, 4 F.E.P.

Cases 1088 (N.D. Cal. 1972). One study found that

Asian participants in the Federal Highway Adminis

tration highway construction-related trades and

apprenticeship training, who successfully completed

their training, nevertheless ware unable to enter

apprenticeship programs because of racial discrim

ination against Asians within the construction

industry in California.— ^ Another striking example

is the recent protracted efforts of Asian American

groups and government agencies to convince builders

and contractors to employ Asians in trainee con

struction jobs at Confucius Plaza, a federally-

supported residential and commercial complex in the

. 15/heart of New York City's Chinatown.—

14. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal

Highway Admin., F. Wu, P. Chen, Y. Okano, P. Woo,

Involvement of Asian Americans in Federal-Aid High

way Construction (1978).

15. See, New York State Advisory Comm, to the U.S.

Comm'n on Civil Rights, The Forgotten Minority:

Asian Americans in New York City 28-29 (1977)T~~

-12-

II. ASIAN AMERICANS ARE STILL SUBJECT TO

THE VESTIGES OF PRIOR

CRIMINATION IMPOSED BY LAW,

Asian Americans have been subjected to state-

imposed discrimination since their earliest arrival

in the mid-1800!s. The early history of Asian

American wage earners and businessmen reflects

their participation in diverse occupations and

industries. However, in each area in which Asian

Americans became competitive in the pursuit of

their livelihood with the white population, pro

hibitive statutes and ordinances were enacted or

discrirninatorily applied against Asians: indeed,

the history of Asian Americans in the western

states, to which they first immigrated, is largely

the history of legally-imposed exclusion from the

mainstream of business life and restriction to

separate and lesser economic pursuits Yick

Vfc> v . Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886), in which this

Court struck down an ordinance regulating laundry

buildings which San Francisco authorities adminis

tered "with an evil eye and an unequal hand" to

exclude Chinese from an entire occupation, and for

16. The history of legally-enforced discrimination

and exclusion of Asians is set forth in M. Coolidge,

Chinese Immigration (1909) (hereinafter "Coolidge");

E. Sandmeyer, The Anti-Chinese Movement in Califor

nia (1939) (hereinafter "Sandmeyer1'); F. Churran, The

Bamboo People: The Law and Japanese Americans (1976)

(hereinafter "Chuman"). See generally P. Murray,

States' Laws on Race and Color (1951).

-13-

which "no reason for it exists except hostility to

the race and nationality to which petitioners

belong," id. at 374, was but one, and by no means

the most invidious, part of the structure of racial

discrimination and exclusion sanctioned by law.

The earliest Asian immigrants were the Chinese

who began arriving in substantial numbers in 1847.

The Chinese arrived as contract laborers to work

in the mines and later on the railroads. In the

1870's, following the completion of the railroads,

Chinese entered a broad range of agricultural and

manufacturing industries. They were also self-

17/

employed as laundrymen, darestics, and peddlers.—

However, Chinese miners were subject to a foreign

miner's tax enforced only on them,— 'and San Fran-

19/

cisco imposed a vehicle tax on Chinese laundrymen—

17. The history of the Chinese in the West is set

forth in Coolidge, supra note 16; Sandmeyer, supra

note 16; S. Lyman, The Asian in the West 9-26

(1970); S. Lyman, Chinese Americans (1974); see

also P. Chiu, Chinese Labor in California, 1850-

1880 (1967); I. Light, Ethnic Enterprise in America:

Business and Welfare Amtijg~QiInese, Japanese and

Blacks (1972).

18. Foreign Miners' License Tax, Act of Apr. 13,

1850, ch. 97, § 1 et seg., 1850 Cal. Stat. 221.

See Coolidge at 36.

19. Municipal Reports, 1871-72, 550; see Sand-

ireyer at 52.

-14-

Chinese peddlers were prohibited from using poles

and baskets, a traditional method of transporting

goods and food.— ̂ The California State Consti

tution of 1879 expressly forbade the employment of

any Chinese, directly or indirectly, by any Cali-

21/fomia corporation or governmental entity.—

While that provision did not survive constitutional

challenge, other prohibitive statutes and ordinances

22/were widely enacted throughout the western states.—

What discriminatory laws and court rulings failed

to achieve, physical violence and anti-Chinese

sentiment completed. Finally in 1882 the first

Chinese Exclusion Act was passed prohibiting further

immigration and setting off a policy of curtailment

23/which continued into the middle of this century.—

20. S. Lyman, The Asian in the West 23 (1970).

21. California Constitution of 1879, art. XIX, §§

2-3. See Sandmeyer at 71-74.

22. See, e.g., Idaho Constitution of 1890, art.

13, § 5 (public works); Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118

U.S. 356 (1886) (San Francisco laundry building

ordinance); In re Hong Yen Chang, 84 Cal. 163 (1890)

(attorneys).

23. Chinese Exclusion Act, 22 Stat. 58 (1882).

See The Chinese Exclusion Case, 130 U.S. 581 (1889).

Japanese immigration began in the 1850 !s but did

not reach significant numbers until 1891. Like the

Chinese who came before them and in partial response

to the labor shortage brought about by the prohibi

tions against further Chinese inmigration, the

Japanese also entered the agricultural, mining and

railroad industries. In Colorado and Utah they

branched out into the smelting and refining indus

tries and in the Northwest, into the lumbering in

dustries. The Japanese also engaged in the fishing

24/and canning industries.— - However, numerous

"alien land laws" were passed to prohibit the

Japanese from owning any legal interest in real

25/property,— and lav® were passed prohibiting

Japanese from engaging in commercial fishing by

-15-

24. The history of the Japanese in California is

set forth in Y. Ichihashi, Japanese in the United

States (1932) «- R. Daniels, The Politics of Pre

judice (1952); H. Kitano, Japanese Americans: The

Evolution of a Subculture (1969) .

25. See, e.g., Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U.S. 197

(1923) (Washington statute); Webb v. O'Brien, 263

U.S. 313 (1923); Frick v. Webb, 263 U.S. 326 (1923);

Cockrill v. California, 268 U.S. 258 (1924); Oyaira

v. State of California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948) . See

generally M. Konvitz, The Alien and the Asiatic in

American Lav; 157-70 (1946); McGovney, The Anti-

Japanese Land Laws of California and Ten Other

States, 35 Cal. L. Rev. 7 (1947); Ferguson, The

California Alien Land Law and the Fourteenth

Amendment, 35 Cal. L. Rev. 61 (1947).

-16-

forbidding the issuance of fishing licenses or the

sale of fish by Japanese.— ^ From 1923 to 1933

bills aimed at the Japanese were proposed in vir

tually every session of the California legislature

to prohibit the employment of aliens in government

27 /and by contractors for public work projects,— -

The uprooting of Japanese American families under

Executive Order 9066 wiped out their agricultural,

fishing and small business enterprises. Although

the economic and personal losses can never be fully

recompensed, bills proposing economic redress for

Japanese American internees are being considered

28/by Congress.— Koreans, Pilipinos, and later

Asian immigrants arriving after the Chinese and

Japanese were subject to similar official treat

ment.

While the express legal structure and sanction

that "put the weight of government behind racial

26. Takahashi v. Fish and Game Coran'n, 334 U.S.

410 (1948); T. Abe v. Fish and Game Coirm'n, 9 Cal.

App. 2d 300, 49 P.2d 608 (1935).

27. See Chuman at 111 n.10 (and bills cited there

in) .

28. See, e.g., S. 1647, 96th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1979) .

hatred and separatism"— ' has faded in the modem

postwar era, its effects have not teen eliminated

root and branch. Asian American business activity

remains concentrated in the marginal areas to which

they were relegated by state-imposed discrimination,

small retail trade and personal service enterprises,

see supra. Many of these enterprises operate in

Chinatowns and Little Tokyos throughout the nation.— ^

III. THE SET-ASIDE PROVISION OF THE PUBLIC

TORE EMPLOYMENT ACT 0FT977~IS~A ~

NECESSARY AND PROPER M A N S OF PRO

MOTING THE DEVELOPMENT OF MINORITY

BUSINESSES.

“17-

Senator Brooke, the Senate sponsor, explained

why the set-aside provision is "entirely proper,

appropriate ate necessary."

It is necessary because minority businesses

have received only 1 percent of the Federal

contract dollar, despite repeated legisla

tion,, Executive orders and regulations

mandating affirmative efforts to include

minority contractors in the Federal contracts

pool.

29. University of California Regents v. Bakke,

438 U .S . 265,357-58 (19781 (Brennan, J.)

30. See generally U.S. Dept, of Health, Education

& Welfare, Urban Associates, Inc., A Study of

Selected Socio-Economic Characteristics of Ethnic

Mnorities Based on the 1970 Census, Vo.i.'~l:i7

Asian Americans (1974) (HEW Publ. No. (OS) 75-121).

-18-

It is a proper concept, recognized for

example in this committee's bill which sets

aside up to 2-1/2 percent for projects re

quested. by Indians or Alaska Native villages.

And, the Federal Government, for the last

10 years in. programs like SBA's 8(a) set-

asides, and the Railroad Revitalization Act’s

minority resources centers, to name a few,

has accepted the set-aside concept as a

legitimate tool to insure participation by

hitherto excluded or unrepresented groups.

It is an appropriate concept, because

minority businesses’ work forces are prin

cipally drawn from residents of communities

with severe and chronic unemployment. With

more business, these firms can hire even

more minority citizens. Only with a healthy,

vital minority business sector can we hope

to make dramatic strides in our fight

against the massive and chronic unemploy

ment which plagues minority communities

throughout this country.31/

Experience to date in implementing the Public

Works Employment Act set-aside provision has shown

that it has enabled new minority firms to develop

and existing ones to survive, it has provided

minority firms with valuable technical and manager

ial assistance and experience, and it has exposed

non-minority prime contractors to a wider range of

bidders,

, 32/ work.— -

including moinority firms,for subcontract

31. 123 Cong. Rec. S 3910 (daily ed. Mar. 10,

1977) .

32. U.S. Gen'l Accounting Office, Minority Firmns

on Local Public Works Projects— Mixed Results 13-

15 (1979) . Although not without administrative

problems, the set-aside program has resulted in

benefits to minority firms.

The effects of the set-aside provision will be felt

by minority businesses outside of the construction

industry as well. Public works grants include

contracts for engineering, landscaping, accounting,

guard services, other professional or supervising

services, and supplies. Just as minority con

struction firms can be expected to stimulate the

hiring and employment of minority construction

workers, they can be also expected to stimulate

minority businesses engaged in other secondary and

33/related industries.— -

Amicus respectfully submits that the set-aside

provision is a constitutionally permissible exer

cise of Congressional power to enforce the guaran

tees of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments

and a proper exercise of the spending power. Con

gress has broad powers both to determine the means

by which the intent of the post-Civil War amend

ments are enforced, Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S.

641, 650-51 (1966), and to set the terms upon

which its monetary allotments are conditioned.

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563, 569 (1974). Certainly,

the post-Civil War amendments were not intended to

33. See 123 Cong. Rec. S 3910 (daily ed. Mar. 10,

1977) (Senator Brooke); Economic Development Admin.,

Guidelines for 10% Minority Business Participation

in Local Public Vforks Grants (1977).

-19-

-20-

prohibit measures designed to remedy the effect of

the nation's past treatment of racial minorities.

The Congress that passed the Thirteenth and Four

teenth Amendments and early civil rights acts is

the same Congress that passed the 1866 Freedmen!s

Bureau Act, which provided many of its benefits

and protections only to black freedmen then subject

to the Black Codes, University of California Re

gents v. Bakke, supra, 438 U.S. at 396-98 (Marshall,

J.) .

The Congressional set-aside provision, like the

affirmative action plan in United Steelworkers of

America v. Weber, supra, 99 S. Ct. at 2730, was

"designed to break down old patterns of racial

segregation and hierarchy." The purposes of the

set-aside provision mirror those of the Thirteenth

and Fourteenth Amendments. The specific inclusion

of Asian American business enterprises in the set-

aside program was appropriate because the protect

ions of the post-Civil War amendments and -the civil

rights acts we re specifically intended to protect

the rights of "Chinese coolie labor" as well as

black freedmen, Slaughter House Cases, 83 U.S. 36

(1873) , and that "the application of the Amend

ment to the Chinese race was considered and not

overlooked." United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169

U.S. 649, 697-99 (1898). Again like the affirma

tive action program permitted in Weber, supra, the

the set-aside provision "does not unnecessarily

trammel the interests of the white employees" and

contractors, 99 S. Ct. at 2730, since the set-aside

was for only 0.25 percent of federal funds expended

yearly on construction work in the United States

and the burden of being dispreferred was thinly

spread among nonminority businesses, conprising

96 percent of the construction industry. Fulli-

love v. Kreps, 584 F.2d at 607-608. Last, the

public works employment set-aside program is "a

temporary measure; it is not intended to itaintain

racial balance, but simply to eliminate a manifest

racial imbalance." Weber, supra, 99 S. Ct. at

2730.

-22-

con c l u s i o n

For the reasons above, the opinion and judgment

of the Second Circuit should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

KENNETH CHU

STANLEY MARK

LISA S.J. YEE

43 Canal Street

New York, New York 10002

BILL LANN LEE

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Amicus Curiae

MEILEN PRESS IN C — N. Y. C.