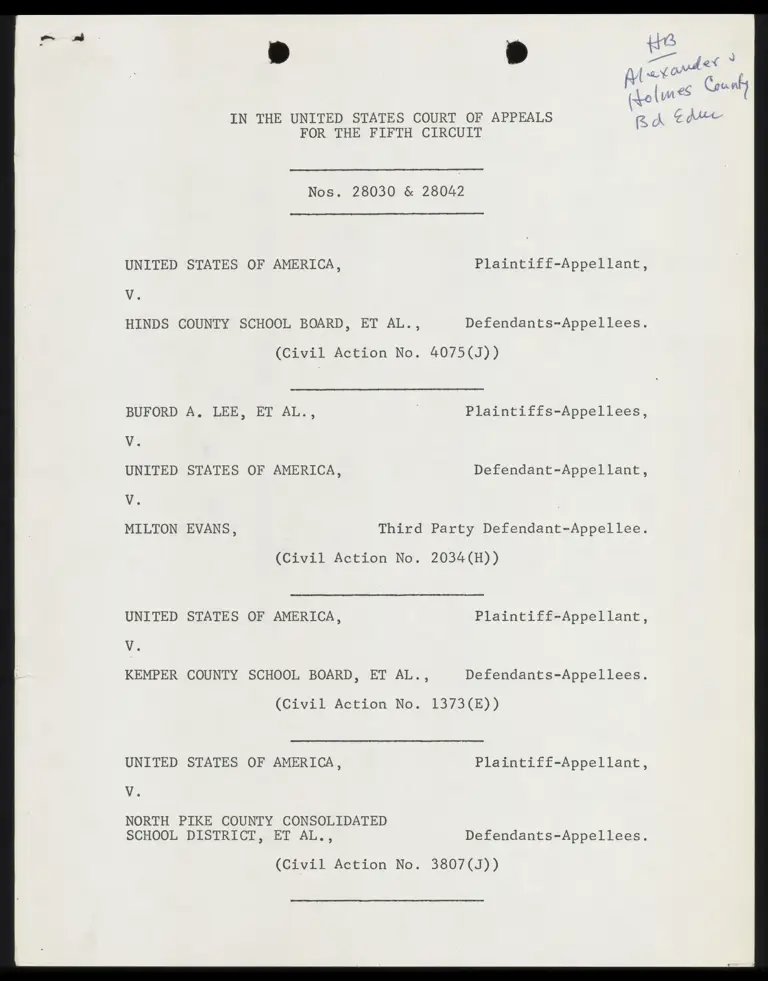

List of Consolidated Cases

Public Court Documents

1969

6 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. List of Consolidated Cases, 1969. 4886eb61-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdd81421. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/df083929-13f6-41a6-b936-4c4795b6cfac/list-of-consolidated-cases. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

{2 a * 4

his

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS CLA

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 28030 & 28042

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

y.

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL., Defendants~Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 4075(J))

BUFORD A. LEE, ET AL., : Plaintiffs-Appellees,

V.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Defendant-Appellant,

y.

MILTON EVANS, Third Party Defendant-Appellee.

(Civil Action No. 2034(H))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

KEMPER COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL., Defendants-Appellees.

{Civil Action No. 1373(E))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

NORTH PIKE COUNTY CONSOLIDATED

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL., Defendants~Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 3807(J))

® »

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

Vv.

NATCHEZ SPECIAL MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL., Defendants=-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1120(W))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

MARION COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL,, Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 2178(H))

JOAN ANDERSON, ET AL., Plaintiffs~Appellants,

y.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant,

V.

THE CANTON MUNICIPAL SCHOOL

DISTRICT, ET AL. and THE MADISON

COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL. Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 3700(J))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

SOUTH PIKE COUNTY CONSOLIDATED

SCHOOL DISTRICT, EY AL. Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 3984(J))

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, ET AL.,

V.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

ET AL.,

(Civil Action No.

Plaintiffs~Appellants,

Defendants~-Appellees.

3779(J))

ROY LEE HARRIS, ET AL.,

V.

THE YAZOO COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION, ET AL.,

(Civil Action No.

Plaintiffs~-Appellants,

Defendants~-Appellees.

1209(W))

JOHN BARNHARDT, ET AL.,

y.

MERIDIAN SEPARATE SCHOOL DISTRICT,

ET AL.

(Civil Action No.

Plaintiffs~Appellants,

Defendants~Appellees.

1300(E))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

V.

Plaintiff-Appellant,

NESHOBA COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL. ,Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1396 (E))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

y.

NOXUBEE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT,

ET AL.,

(Civil Action No.

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Defendants-Appellees.

1372(F))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

y,

LAUDERDALE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT,

ET AlL., Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1367(E))

DIAN HUDSON, ET AL. Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plrintiff-Tntervénovsdppellint,

yY,.

LEAKE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL., Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 3382(J))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

Vv.

COLUMBIA MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL

DISTRICT, ET AL., Defendants=-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 2199(H))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

y,

AMITE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AL., Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 3983(J))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

COVINGTON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT,

ET Al., : Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 2148(H))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

LAWRENCE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT,

ET AL., Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 2216(H))

JEREMIAH BLACKWELL, JR., ET AL., Plaintiffs~Appellants,

y.

ISSAQUENA COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCA=-

TION, ET AL., Defendants~Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1096 (W))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

WILKINSON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT,

ET AL., Defendants~Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1160(W))

CHARLES KILLINGSWORTH, ET AL., Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V.

THE ENTERPRISE CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL

DISTRICT and QUITMAN CONSOLIDATED

SCHOOL DISTRICT, Defendants=-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1302(E))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

LINCOLN COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT,

ET AlL., Defendants~Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 4294(J))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

Vv.

PHILADELPHIA MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET AlL., Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1368(E))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellant,

V.

FRANKLIN COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT,

FT AlL., Defendants~Appellees.

{Civil Action Fo. 4256(3))

ON APPEAL FROM

THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI