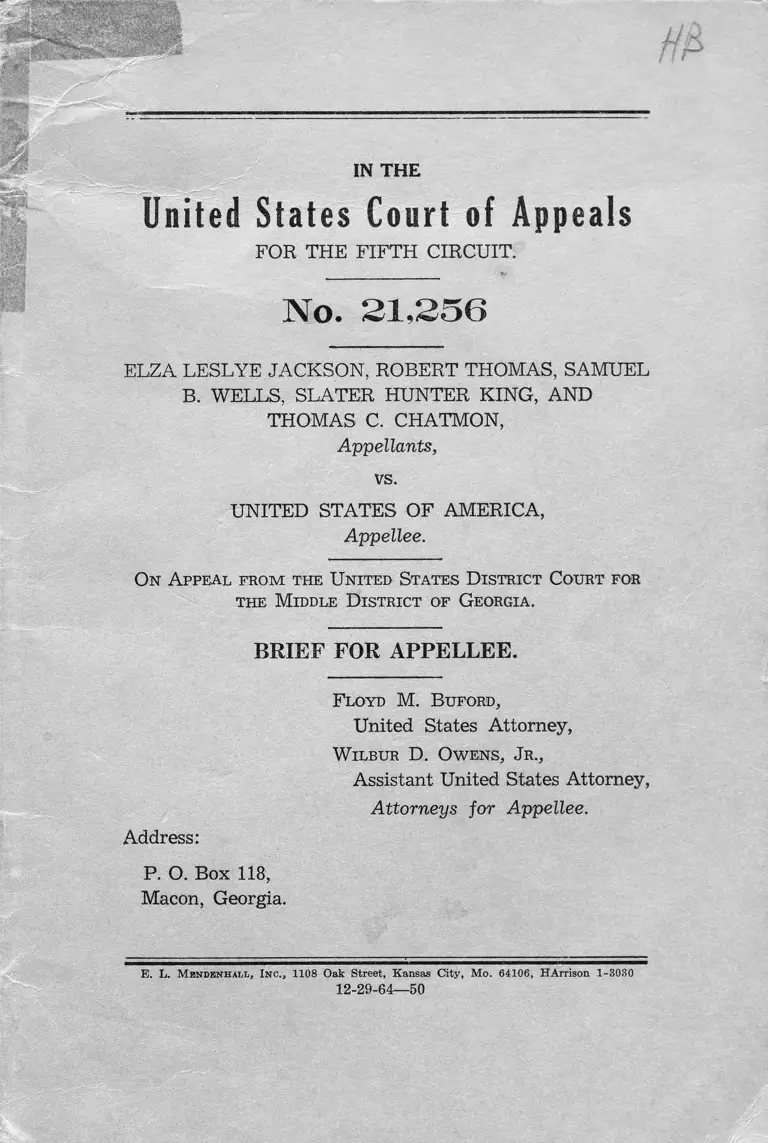

Jackson v. United States Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. United States Brief for Appellee, 1964. 99f409ec-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/df143b79-7e1b-4ea6-80d3-963ac49c17a9/jackson-v-united-states-brief-for-appellee. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT.

No. 21,256

ELZA LESLYE JACKSON, ROBERT THOMAS, SAMUEL

B. WELLS, SLATER HUNTER KING, AND

THOMAS C. CHATMON,

Appellants,

vs.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Middle District of Georgia.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE.

Address:

P. O. Box 118,

Macon, Georgia.

Floyd M. Buford,

United States Attorney,

W ilbur D. Owens, J r.,

Assistant United States Attorney,

Attorneys for Appellee.

E. L. M endenhall, I nc., 1108 Oak Street, Kansas City, Mo. 64106, HArrison 1-3030

12- 29 - 64— 50

INDEX

I. Statement of the Case ......................................... 1

II. The Overwhelming Evidence of Guilt Supports

the Denial of the Motions for Judgment of Ac

quittal Made by Appellants Jackson and K ing...... 2

III. A. Appellant Elza Leslye Jackson .. ..........- ........ 2

1. The Indictment—Jackson ......................... . 2

2. The Evidence—Jackson .............. .......... . 3

3. The Evidence Supports the Verdict............. 5

B. Appellant Slater Hunter King ....................... . 6

1. The Indictment—King ....... ................ . 6

2. The Evidence—King ..... ......................... ..... 7

3. The Evidence Is More Than Sufficient to

Support the Verdict of Guilty .... ................ 9

III. There Is No Basis for the Application of the At

torney-Client Privilege in Appellant Wells’ Case .... 10

A. The Evidence—Reverend Wells .................... . 10

B. The Law Applied to the Evidence—Reverend

Wells ........ ................. ..................... .......... ......... 13

IV. The Jury List from Which the Grand and Petit

Juries Which Indicted and Tried Appellants, Were

Selected, Was Composed in Accordance with the

Civil Rights Act of 1957 and the Decisions of the

Supreme Court of the United States ............ ......... 15

1. The Evidence Adduced Before the Trial Court __ 16

a. The 1959 Jury List ...................... ............... 16

b. The 1953 Jury List ................. ................. ... 20

c. Pre-1953 Jury Lists .... .................. ............... 21

d. Selecting Grand and Petit Juries ................. 22

II Index

e. The Court in Overruling Defendant’s Motion

Stated: ............................................................ 22

f. Statistical Information—1960 Census .......... 24

2. The Law .............................................................. 25

a. Statutory Law on Selection of Federal Jurors 25

b. Decisions of Federal Courts on State Jury

Composition Questions ........................ 29

1. The Supreme Court ................................ 29

2. Decisions of This Court on the Composi

tion of State Juries ......................... 33

c. Decisions on the Composition of Federal Ju

ries ................................................................. 36

1. The Supreme Court ................................... 36

2. The Circuit Courts of Appeal ......... ......... 38

d. The Jury System As Envisioned by the Judi

cial Conference and the Justice Department _ 39

e. Burden of Proof..... ........................................ 40

3. The Law Applied to Our Case ...."„........ ,............ 41

V. Conclusion _ 45

Certificate of Service .... .............1—............................. 45

Appendices—

Appendix from Rabinowitz:

B. Excerpts from 1960 Census............................... 47

C. Department of Justice Proposal for Amending

Section 1864, Title 18, United States Code .... 49

Cases Cited

Ah Ming Cheng v. United States, 300 F.2d 202 .... ..... 2

Akins v. Texas, 325 U.S. 398 ...................................... 33

Arnold and Dixon v. North Carolina, 32 U.S.L. Week.

4340 .......... ............................ ...............................29, 31,32

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 __ ...______________ 32

Ballard v. United States, 329 U.S. 187 ..................... 37

Bennett v. United States, 285 F.2d 567 ....... ............ . 2

Brownfield v. South Carolina, 189 U.S. 426 ................. 41

Cafritz v. Koslow, 167 F.2d 749 ............................... . 14.15

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 .....................................-33, 44

Chance v. United States, 322 F.2d 201 ............. 28-29, 38, 39

Collins v. Walker, 329 F.2d 100...................................... 33

Dow v. Carnegie-Illinois Steel Cor-p., 224 F.2d 414...... 38

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 ............................ 32

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U.S. 565 ........................... ... 30

Glosser v. United States, 315 U.S. 60 .................... 2, 36, 41

Gorman v. United States, 323 F.2d 51 ............................ 2

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 .............................. T31, 32

Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 ......... .............................31,33

Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57 .................. ............ ........ . 41

Johnson v. United States, 271 F.2d 597 .... ................... 2

Martin v. Texas, 200 U.S. 316 .... ................ ............ .... 30

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 ..........................—_ 30

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 ................ ........... 30, 31, 33

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 ............................... 32

Riggs v. United States, 280 F.2d 949 ______...______... 2

Rogers v. Alabama, 192 U.S. 226 _________ _______ 30

Smith v. Mississippi, 162 U.S. 592 ___...________ __41

Smith V. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 _______________ 31,33,36

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 308 __________ 29, 30

Tarrance V. Florida, 188 U.S. 519 _______________ 41

Thacker v. United States, 155 F.2d 90 ______ ______ 2

Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217 _____36, 37, 38

Thomas v. Texas, 212 U.S. 278 _________________ 33

Index h i

IV Index

United States v. Debrow, 346 U.S. 374 ______________ 5

United States v. Greenberg, 200 F. Supp. 382 ............. 29

United States, v. Kovel, 296 F.2d 918 _....................... 14

United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53___ 34, 35

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313 _______________ __ 33

Walker v. United States, 301 F.2d 94 ____________ 2

Miscellaneous

8 Wigmore, Evidence (McNaughton rev. 1961) 554 . 13

The Jury System in the Federal Courts—

26 F.R.D. 409, 421 __________ ________ 39-40, 41-43

28 U.S.C., Sections 1861-1864 .....................25,26,27,40,44

103 Cong. Rec. 13250, 13290, 13291 ............. ..... 27,28, 38

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT.

No. 21,256

ELZA LESLYE JACKSON, ROBERT THOMAS, SAMUEL

B. WELLS, SLATER HUNTER KING, AND

THOMAS C. CHATMON,

Appellants,

vs.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Middle District of Georgia.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE.

I. STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

Appellants’ Statement of the Case while generally

accurate is nevertheless incomplete and written with a view

towards Appellants’ argument. Appellee will therefore

rely on its own Statement which will be presented as a part

of each particular point of Appellee’s argument.

2

II. THE OVERWHELMING EVIDENCE OF

GUILT SUPPORTS THE DENIAL OF THE

MOTIONS FOR JUDGMENT OF ACQUITTAL

MADE BY APPELLANTS JACKSON AND

KING.

Only appellants Jackson and King question the suf

ficiency of the evidence to support their convictions of

perjury. In considering appellants’ denied motions for

judgment of acquittal and the “sufficiency or insufficiency

of the evidence to support the conviction, it is not . . . [this

court’s] function to weigh the evidence or to pass upon

the credibility of the witnesses. Judgment of conviction

must stand if there is substantial evidence to support the

judgment considering the entire record in a light most

favorable to the United States. Glasser v. United States,

315 U.S. 60 (1942); Walker v. United States, 5 Cir. 1962,

301 F.2d 94; Ah Ming Cheng v. United States, 5 Cir. 1962,

300 F.2d 202; Bennett v. United States, 5 Cir. 1960, 285 F.2d

567; Riggs v. United States, 5 Cir. 1960, 280 F.2d 949;

Thacker v. United States, 5 Cir. 1946, 155 F.2d 90; Johnson

V. United States, 4 Cir. 1959, 271 F.2d 596, 597;” Gorman v.

United States, 323 F.2d 51 (5th Cir., 1963).

The substantial evidence that supports the conviction

of appellants Jackson and King is:

A. APPELLANT ELZA LESLYE JACKSON.

1. The Indictment—Jackson.

The indictment charges that appellant Jackson com

mitted perjury on August 5, 1963, before a Grand Jury of

3

the United States District Court for the Middle District

of Georgia in that she did:

. . testify in substance that she, the defendant,

did not recall being present at the meeting held in

the office of [sic] Attorney C. B. King, Albany,

Georgia, on the afternoon of July 30, 1963 . .

2. The Evidence—Jackson.

Prior to Tuesday, July 30, 1963, a subpoena directing

each person to be in U. S. District Court, Macon, Georgia,

before a federal grand jury on Wednesday, July 31, 1963,

at 9:30 a.m. was served on each of the following persons:

Appellant Elza Leslye Jackson; Slater H. King; Samuel

B. Wells; Robert Thomas; Thomas Chatmon; Dora White;

Emma Perry; Edward Bryant, Jr.; Howard Seay and Sego

Thomas Gay. (G-2 through 11).

Attorney C. B. King has an office in Albany, Georgia,

which consists of two rooms—an outer reception room where

his secretary works and an inner private office which he

uses. In July, 1963, Mrs. Ann Waller Butler was his

secretary and Miss Elizabeth Holtzman, Mr. Frank Parker

and Mr. Dennis Roberts, none of whom were admitted to

the practice of law, were his law clerks. (R. 281-283).

Between 4:45 p.m. and 6:30 p.m., Tuesday, July 30,

1963, according to Mrs. Ann Waller Butler, secretary, a

group representing a church came to Attorney C. B. King’s

office. (R. 297). In addition to the church group, Mrs.

Elza Leslye Jackson, appellant; Slater King; Samuel Wells;

Thomas Chatmon; Robert Thomas; Mrs. Emma Perry;

Howard Seay; Sego Gay and Mrs. Dora White came to

Attorney King’s office. (R. 291-292). During that time

4

people were in both rooms of the office and the door

between the rooms was open. As many as 18 to 20, and

as few as 6 persons, were present together from 4:45 until

6:30 p.m. Some were seated and some were standing.

Slater King brought extra chairs to the office. At one

time all the people were seated. (R. 293). Miss Elizabeth

Holtzman talked to the entire group about the rights of

witnesses appearing before a federal grand jury. (R. 292-

293). Persons present asked questions. Appellant Jackson

was present for 15-25 minutes. (R. 294).

Miss Elizabeth Holtzman, a Harvard law student work

ing as law clerk, said that during the same time she saw as

many as 15 and as few as 6 people in the office of Attorney

C. B. King. Of those people she could name only Howard

Seay, Thomas Chatmon, Samuel Wells and appellant Jack-

son. For somewhat over an hour she stayed in Attorney

King’s private office. During that hour she talked about

the functions and the composition of the United States

grand jury. Questions were asked. (R. 300-305). While

in Attorney King’s private office she specifically saw

appellant Jackson, Howard Seay, Samuel Wells, Slater

King and Mrs. Butler. (R. 306).

Eddie Bryant, Jr., who had been subpoenaed to appear

in Macon before the grand jury (R. 308), went to Attorney

C. B. King’s office around 5:30 p.m., Tuesday, July 30.

Nine to 12 people were in the office when he arrived.

(R. 310). Appellant Jackson was there on his arrival. (R.

313). He heard a lady speak about coming to Macon to

appear before a grand jury. (R. 312). Reverend Wells

and appellant Jackson also had something to say about the

5

grand jury. (R. 314). He remembered only the following

names of people he saw: appellant Jackson, Robert

Thomas, Sego Gay, Miss Emma Perry and Vincent Collier.

(R. 312). He stayed in Attorney King’s office for about

one-half hour (R. 310), and when he left appellant Jackson

was still there. (R. 313).

Appellant’s grand jury testimony was read to the jury.

(R. 332-345).

Appellant Jackson said that her answers to the grand

jury were true when given. (R. 349). She also stated that

she had received an A.B. degree from Benedict College.

Otherwise appellant’s answers on cross-examination were

evasive. (R. 351-355).

3. The Evidence Supports the Verdict.

The essential elements of perjury are:

(1) an oath administered and authorized by a law

of the United States

(2) taken before a competent tribunal

(3) a false statement

(4) wilfully made

(5) as to facts material to the hearing.

United States v. Debrow, 1953, 346 U.S. 374. Appellant

Jackson questions only elements (3) and (4) and so just

contends that there was no false statement wilfully made.

Appellant Jackson, as shown by her grand jury testi

mony (R. 332-345), in sum and substance clearly told the

grand jury she did not recall being present at the meeting

held in the office of Attorney C. B. King, Albany, Georgia,

on the afternoon of July 30, 1963.

6

The testimony of all three witnesses—Mrs. Butler,

Miss Holtzman and Mr. Bryant—paints a vivid picture of a

gathering of persons who had received grand jury sub

poenas on the afternoon preceding the morning of their

appearance before the grand jury. How many persons?

According to Attorney King’s secretary as many as twenty.

Chairs were brought; all were seated. Miss Holtzman

talked about the rights of witnesses appearing before a

federal grand jury. Appellant Jackson, a college graduate,

according to Miss Butler and Mr. Bryant was present for

25-30 minutes, and as related by Mr. Bryant appellant also

had something to say to those present about the grand jury.

The only evidence that disputed the prosecution’s case

was appellant’s mere statement that her grand jury testi

mony was true.

It is thus apparent that the jury listened to practically

uncontradicted evidence from three witnesses; that the evi

dence was more than sufficient to support a finding of

guilty and that the trial court correctly denied appellant’s

motion for judgment of acquittal.

B. APPELLANT SLATER HUNTER KING.

1. The Indictment—King.

Appellant King was charged with committing perjury

by testifying before a grand jury of the United States

District Court for the Middle District of Georgia on August

5, 1963, in substance that:

“he . . . did not recall attending any type of meeting

during the week of July 29, 1963, through August 2,

7

1963, wherein he or others discussed the fact that this

Grand Jury was in session here in Macon, Georgia.”

(R. 824-825).

2. The Evidence—King.

As of July 20, 1963, appellant King, Elza Leslye

Jackson, Samuel Wells, Thomas Chatmon, Edward Bryant,

Jr., Robert Thomas, Mrs. Emma Perry, Howard Seay, Sego

Gay, Mrs. Dora White, and Eddie Brown had all received

subpoenas to appear in U. S. District Court, Macon, Georgia,

July 31, 1963, at 9:30 a.m. (R. 895; Gl-11).

Attorney C. B. King’s office in Albany, Georgia, con

sists of two rooms—an outer for reception and his secretary

and an inner private office. (R. 860). In July, 1963, Mrs.

Ann Waller Butler, secretary, and Miss Elizabeth Holtz-

man, Mr. Dennis Roberts, Mr. Frank Parker, law clerks

but not lawyers, worked for Attorney King. (R. 860-863).

Around 4:30 on the afternoon of July 30, Attorney King

telephoned his office and talked with Mrs, Butler, his

secretary, and Miss Holtzman, his law clerk. (R. 881-882).

Attorney King indicated he had a conference scheduled

and asked Miss Holtzman “to speak to the group . . . when

they came . . . [about] the functions and structure of the

Federal grand jury.” (R. 926-927). After the phone call,

the conference was held. (R. 884).

Between the phone call around 4:30 and when she left

the office around 6:15-6:30 p.m., Mrs. Butler saw Mrs.

Jackson, Samuel Wells, Thomas Chatmon, Robert Thomas,

Mrs. Emma Perry, Howard Seay, Sego Gay, Mrs. Dora

White and appellant Slater King come into the office of

8

Attorney C. B. King. (R. 861). According to Mrs. Butler,

appellant King arrived around 5:15-5:30 p.m,, and was

there 10 to 15 minutes. (R. 866). Mrs. Butler saw as many

as 18 and as few as 6 people in the office during the almost

two hour period. (R. 868). People were seated and

standing, but around 5:30, when appellant King was there,

they were all seated. (R. 866; 869). They were seated in

both rooms. (R. 930, Holtzman). Miss Holtzman talked

to the group as a whole about the rights of witnesses

appearing before federal grand juries (R. 871), and

Reverend Wells made remarks in the inner room about

the same subject. (R. 872-873).

Miss Elizabeth Holtzman told of being asked by Attor

ney C. B. King by telephone “to speak to the group, to these

people . . . when they came . . . [about] the functions and

structure of the federal grand jury . . .”. After the tele

phone conversation people came to the office. (R. 926-927).

Miss Holtzman stayed in the inner room, the room

usually used by Attorney C. B. King, from approximately

4:30 to about 6:15 (R. 934) (the entire time during which

the meeting took place). She “. . . discussed briefly the

functions and the structure of the federal grand jury”.

Questions were asked about her talk. (R. 931). In the

inner room she saw appellant Slater King. (R. 934). The

greatest number of people she saw was 15 and the least

number was 8 or 9. (R. 929-930). “. . . For the most part,

people were seated.” (R. 935). The defendant must have

also been seated because according to Miss Holtzman, “I

believe he did get up” to answer the telephone. (R. 941).

Eddie Bryant, Jr., was told by Robert Thomas that

there was to be a meeting. (R. 916). He went to C. B.

9

King’s office around 4:45. . . Most everyone in there

was talking . . . about coming up here to appear before the

jury . . . the grand jury.” (R. 899, 900). Eddie Bryant

stayed about 40 minutes. Slater King was there when he

got there (R. 904), during the time he was there (R. 902-

903), and when he departed, he left appellant King there.

(R. 904). Reverend Weils was also there the full time

Bryant was. (R. 907). A white girl (Miss Holtzman)

talked about coming up to Macon the next day. (R. 911).

Reverend Wells and Mrs. Jackson also talked. (R. 913).

The appellant King, a graduate of Fisk University (R.

995) admitted coming to the office of C. B. King, bringing

chairs and sitting down in the inner room. (R. 984). He

remembered seeing Mrs. Jackson, Mrs. Perry, Mrs. White,

Reverend Wells, Mr. Bryant, and Mr. Seay in the office.

(R. 998-999).

The appellant’s grand jury testimony consisting of

more than the two isolated questions selected by appellant

in his brief, p. 16, was read to the jury and introduced in

evidence. (R. 957-962).

3. The Evidence Is More Than Sufficient to Support the

Verdict of Guilty.

Like appellant Jackson, appellant King contends that

of the five essential elements of perjury heretofore listed,

the evidence fails to show (3) a false statement (4) wilfully

made.

As shown by the transcript of appellant’s grand jury

testimony the appellant clearly told the grand jury in sum

and substance that he did not recall attending any type of

10

meeting during the week of July 29, 1963, through August

2, 1963, wherein he or others discussed the fact that the

Grand Jury was in session in Macon, Georgia.

Appellant King asks this court to believe what the

trial jury would not believe—that together with other

people who had also been subpoenaed to be in Macon the

next morning before a grand jury, he was in the office of

Attorney C. B. King for a minimum of 15 (Mrs. Butler)

and maximum of 40 minutes (Mr. Bryant); he was seated

in the inner private office; everyone was talking about

coming to Macon to the grand jury; Miss Holtzman, Rever

end Wells, and Mrs. Jackson talked to the group about the

grand jury; he, a college graduate, did not know what was

being discussed. The record and this summation of the

evidence clearly shows that there was more than sufficient

evidence on which to reach a finding that appellant knew

the subject matter of the discussion in that office and to

aid the grand jury in its deliberations could have told the

grand jury of the meeting. The trial court correctly denied

appellant’s motion for judgment of acquittal.

III. THERE IS NO BASIS FOR THE APPLICA

TION OF THE ATTORNEY-CLIENT PRIVI

LEGE IN APPELLANT WELLS’ CASE.

A. THE EVIDENCE—REVEREND WELLS:

Mrs. Ann Waller Butler, secretary to Attorney C. B.

King, explained that of six particular people—appellant

Samuel Wells, Thomas Chatmon, Robert Thomas, Mrs.

Emma Perry, Slater King, and Mrs. Elza Jackson—only

one, Thomas Chatmon, had an appointment with C. B. King

11

the afternoon of July 30, 1963. (R. 630-631). C. B. King

was absent; in his absence a discussion took place. (R.

633). Twelve or 13 people attended the conference. Rever

end Wells didn’t arrive until around 6:00. (R. 644).

After this Mrs. Butler testified on page 655:

“A. Rev. Wells did say something to the people

that were sitting near him, but I don’t recall him having

something to say to the entire group. However, you

could hear what Rev. Wells was saying.”

Mr. Blasingame:

“Q. What was he saying?

“A. Now, as to what he was saying, I really

couldn’t say. I believe—no—he explained the condi

tions under which he felt that he had received his

subpoena. (Emphasis added).

“Q. What subpoena?

“A. A subpoena that said United States versus

Several.”

and the following objection was made:

“Mr. King: Now, if Your Honor pleases, I would

object to anything that Rev. Wells said in the office of

Attorney King, responsive to a conference or alleged

conference that was held in said office. The grounds

of the objection are that anything that he might have

said under these circumstances was a privileged com

munication and such privilege can only be waived by

the Defendant; and certainly this witness has no power

to waive that privilege.”

Appellant did not attempt to prove the existence of the

attorney-client privilege, and the court overruled the

objection. (R. 656).

12

Mrs. Butler then told the jury that Reverend Wells had

explained the conditions under which he felt that he had

received his subpoena. (R. 655). “. . . Rev. Wells indicated

to them [those present] to do just what Miss Holtzman

had advised them before he got there.” (R. 657).

Attorney King represented Reverend Wells in two

pending matters—a recent court matter in Albany and a

Marine Base administration matter. (R. 662). Reverend

Wells on this day came to the office, asked for Attorney

King and after learning that he was not in just went on into

the other office (where the other people were). (R. 665).

Miss Elizabeth Holtzman, a law student and law clerk,

after advising that the gathering began about 4:30 and the

doors between the two offices were open was asked on p.

684:

“Q. Would you tell us the subject-matter of your

conversation to the group?”

and the following objection was made;

“Now, if Your Honor pleases, I would object to

any information being elicited from this witness with

reference to any discussion or any talk or communica

tion that she might have had with [114] persons in

the office of Attorney King. The basis for the

objection is that this would be privileged matter and

such privilege would belong to those persons who were

present; and certainly she is in no position to waive the

privilege of others.”

Appellant did not attempt to lay an evidentiary foundation

for the objection; the court overruled the objection, and

the witness answered:

13

“A. Well, the subject matter of my conversation

was the structure and function of the grand jury.”

(R. 686).

Appellant Wells when testifying said he never made

appointments with Attorney King. On this particular

afternoon he didn’t think he had heard that a group was

meeting in C. B. King’s office. He went to the attorney’s

office to see him about personal business (R. 753)—Attor

ney King had represented him on the base where he works

and Rev. Wells had just gotten out of jail. (R. 745; 749;

750). He definitely did not go to Attorney King’s office to

attend any meeting. (R. 765). When he got into Attorney

King’s office, Rev. Wells saw some people in Attorney

King’s private office; and he just walked into the private

office and spoke to one or two or them. (R. 754).

B. THE LAW APPLIED TO THE EVIDENCE-

REV. WELLS.

“ (1) Where legal advice of any kind is sought (2)

from a professional legal adviser in his capacity as such,

(3) the communications relating to that purpose, (4) made

in confidence (5) hy the client, (6) are at his instance

permanently protected (7) from disclosure hy himself or

hy the legal adviser, (8) except the protection he waived.”

8 Wigmore, Evidence (McNaughton rev. 1961) 554. And

as appellant contends, “it has never been questioned that

the privilege protects communication to the attorney’s

clerks and his other agents (including stenographers) for

rendering his services.” ibid., p. 583.

14

Appellant, however, neglects to point out that the

burden of showing that the relation giving rise to the

attorney-client privilege existed, is on the person who

invokes the privilege, United States v. Kovel, 296 F.2d 918,

923 (2d Cir., 1961); and that “the mere relation of attorney

and client does not, ipso facto, establish the principle. If

the circumstances do not imply confidentiality to a com

munication between the client and his attorney privilege

does not attach . . Cajritz v. Koslow, 167 F.2d 749, 751

(D.C. Cir., 1948).

The appellant’s own testimony best demonstrates that

it was never his contention that he went to the office of

Attorney C. B. King for legal advice concerning appearing

before the federal grand jury. In fact not only did appel

lant by his own testimony deny seeking legal advice about

the grand jury, but appellant further testified that he got

no legal advice. Appellant now asks this court to forget

his contention that he got no legal advice and invoke the

attorney-client privilege to exclude testimony of the legal

advice he didn’t get. Clearly, even forgetting the incon

sistency between Mrs. Butler’s, Miss Holtzman’s and

appellant’s trial testimony, the evidence in this case does

not establish circumstances implying confidentiality.

Going further and assuming that appellant had at

tempted to establish the attorney-client relation by evi

dence, appellee could have shown the presence of Edward

Bryant, Jr., who was just told by Robert Thomas to be in

Attorney C. B. King’s office for a meeting (R. 916) and

was not there seeking legal advice from Attorney King or

his law clerk. Upon such a showing the relation of

15

attorney-client and the privilege flowing therefrom would

disappear for . . the presence of a third person (other

than the agent of either client or attorney) generally

rebuts the presumption of confidentiality . . Cafritz v.

Koslow, supra.

Clearly there is no basis for appellant’s assertion of the

attorney-client privilege.

IV. THE JURY LIST FROM WHICH THE GRAND

AND PETIT JURIES WHICH INDICTED AND

TRIED APPELLANTS, WERE SELECTED,

WAS COMPOSED IN ACCORDANCE WITH

THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1957 AND THE

DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT OF

THE UNITED STATES.

The jury list in question is the same jury list challenged

by the appellant in Rabinowitz v. United States, Fifth

Circuit, No. 21,256, already briefed and argued before this

court. We agree with appellants that tKis court may take

judicial notice of its own records. Brief for Appellants

p. 5.

The evidence which appellant rely upon in challenging

the jury composition was adduced on October 3, 1963. (R.

99). On October 14, 1963—almost two weeks later—the

hearing on the identical question in the Rabinowitz case

was held. (R. 141, Rabinowitz). Consequently all counsel

in Rabinowitz had the opportunity to benefit from the

initial exploration by Appellants on the jury composition

issue, and the Rabinowitz record is naturally more com

plete. Since the Rabinowitz record contains more, appellee

16

with the hope that it meets the court’s approval asks this

court to consider the Rabinowitz record.

As was said in Appellee’s Brief in Rabinowitz:

1. The Evidence Adduced Before the Trial Court.

“The Macon Division, Middle District of Georgia,,

comprises the counties of:

Baldwin, Bibb, Bleckley, Butts, Crawford, Hancock,

Houston, Jasper, Jones, Lamar, Monroe, Peach, Pu

laski, Putnam, Twiggs, Upson, Washington, and Wil

kinson. 28 U.S.C. 90(b) (2).

a. The 1959 Jury List—

“In 1959, William P. Simmons, a Republican and out

standing Georgia citizen and businessman whose home is

Macon, was first appointed Jury Commissioner for the

seventy (70) counties of the Middle District of Georgia.

John P. Cowart—Assistant United States Attorney from

March 12, 1934, United States Attorney from February 6,

1945, and Clerk from December 1, 1952—and Jury Com

missioner Simmons by direction of the court undertook

to revise the jury box for each of the seven divisions of

the Middle District of Georgia. (R. 181-182, 216, 227).

“The first indoctrination Commissioner Simmons had

was from the Judge (W. A. Bootle); he instructed Mr.

Simmons about his duties and responsibilities. From the

Judge or the Clerk, Mr. Simmons received a large mimeo

graphed publication. (R. 184). This publication, a manual

from the Administrative Office of the Courts, was also used

by the Clerk. (R. 228). Mr. Simmons and Mr. Cowart

17

became familiar with the jury qualifications set forth in

the Civil Rights Act of 1957. (R. 185, 227).

“In revising the Macon Division jury list, the Commis

sioner and the Clerk began with the existing prior jury

list—1953—and removed from that list the names of those

who had moved, were deceased, mentally infirm or physi

cally not able to serve. (R. 182, 230). After names were

removed, about 1,000 names were left from the 2205 names

on the 1953 jury list. (R. 220-221, 238).

“Mr. Simmons as President, Southern Crate and Veneer

Company, was traveling extensively throughout the Macon

and other divisions. (R. 216). In securing names of

prospective jurors he didn’t write to anybody asking them

to provide a list of jurors, nor go and say, ‘give me a list

of jurors’ to anybody. Commissioner Simmons, carrying

a little book and pad of paper, made inquiries in all the

counties and wrote down the names that he secured. (R.

194). Some year and a half or two years ago, thinking he

was through with his work as Jury Commissioner, Mr.

Simmons threw out his file. (R. 184). Because of this it

is difficult to recall specific instances and people. (R. 200).

He inquired specifically for the names of Negroes who

could serve on the jury (R. 205), recalled asking a few

Negroes for names (R. 192-193), and in every instance

where he talked to a white person, remembered that he

suggested that the white person give him the names of

competent Negro jurors. (R. 196).

“John Cowart sent his deputy clerk, Walter Doyle, into

each of the counties including those in the Macon Division

to secure names. (R. 230). Mr. Doyle went first to each

18

of the county courthouses and spoke to the Clerk of the

Court, the Ordinary, the Sheriff, Tax Officers and people

who worked in those offices. These people in his judg

ment knew the people in each community better than

anyone else. (R. 260). Mr. Doyle did not talk to Negroes

about prospective jurors, but did ask each person contacted

to give him all of the names they could of prospective

Negro jurors. (R. 261). The names secured by Deputy

Clerk Doyle were turned over to Clerk Cowart.

“Mr. Cowart, in addition to sending his deputy clerk

into the counties, wrote a good many letters to people. He

knows a lot of people in the counties of the Macon Division

and acquired probably more names in Macon than either

Mr. Doyle or Mr. Simmons. Mr. Cowart used the telephone

book some and talked to Negroes as well as white persons.

He had a number of sources from whom he got names.

(R. 230-232).

“Including the 1,000 names from the old 1953 list and

the new names they had acquired, Clerk Cowart and

/ Commissioner Simmons sent out between four and five

; | thousand jury questionnaires to people in the Macon

Division. (R. 237). The Clerk did not even have an idea

of how many questionnaires went to Negroes. (R. 239).

On the questionnaire, one of thirteen items to be filled out

pertained to the individual’s race. (D-2).

“A population census table was used for only one

thing—to prorate jurors according to counties and not in

any other manner. (R. 259).

“Neither Commissioner Simmons, Clerk Cowart nor

Deputy Clerk Doyle had any preconceived notion of how

19

many of the jurors should be Negroes. (R. 186, 241, 258,

266).

“From the 2,500-3,000 jury questionnaires that were

returned—all of which are on file in the Clerk’s office

and were available to defense counsel—the Commissioner

and the Clerk selected 1,985 names. (R. 237, 239). No

calculation has been made by either the Commissioner or

the Clerk of how many Negroes were selected. (R. 183,

225, 237).

“Neither Mr. Cowart nor Mr. Simmons, as defense

counsel has conceded (Appendix 104, Statement by Mr.

Rabinowitz), systematically or intentionally excluded

Negroes in selecting the 1,985 names. (R. 187, 259). They

did look at and use the race designation on the jury

questionnaire to make sure that Negroes were included,

but they had no particular number in mind. (R. 186, 188,

241). The only object was ‘. . . to get qualified Negroes

it was rather hard to do . . . because they (Negroes) are

just like women; they don’t want to be in the box and

they don’t want to serve’. (R. 241, Cowart). Mr. Cowart

and Mr. Simmons ‘attempted to be sure that all factions

and groups within the community were represented,

occupation-wise, sex and racially wise, but without at

tempting to measure it by the population precisely or to

have any given percentage represented by any vocational

or occupational group or by race or sex’. (R. 187,

Simmons).

“Using the race information on the 1959 jury question

naire forms as a source, the United States Attorney had

the following information about the 1959 jury list of the

Macon Division prepared for this case:

20

County No. of Jurors No. of Nej

Baldwin 137 8

Bibb 666 36

Bleckley 72 2

Butts 58 2

Crawford 47 5

Hancock 64 3

Houston 99 7

Jasper 57 4

Jones 67 5

Lamar 84 7

Monroe 70 5

Peach 123 8

Pulaski 58 3

Putnam 61 4

Twiggs 37 1

Upson 130 6

Washington 95 6

Wilkinson 60 5

Total 1,985 117

Five jurors did not indicate race. (R. 315-316). These

figures indicate 5.9% of the names on the 1959 jury list

are those of Negroes.

“The record does not show how many Negroes or whites

are qualified for jury service.

b. The 1953 Jury List.

“The 1953 jury revision was in progress when John

Cowart became Clerk. 1,897 names were on the 1953 list.

In 1954 after the Georgia Legislature made women eligible

for jury service (U. S. District Court jurors were then

21

governed by state qualifications), the names of 308 women

were added to the 1953 list. (R. 220-221).

“On the original 1953 jury list, which is kept in the

Clerk’s office and is available to and frequently used by

the public, there are C’s made with a red crayon by the

names of 40 jurors. (R. 249, 285-288). The entire jury

list is typewritten. (R. 257). The Clerk keeps a copy

for a check list and does not mark on the original. (R.

225). In preparing defendant’s affidavit in support of this

ground of the motion, Attorney Witt assumed that all

Negroes on the 1953 jury list had C’s by their names.

(R. 224, Rabinowitz). The defendant’s attorney, however,

stated that was not the defendant’s contention. (R. 222-

223). There is no record in the Clerk’s office to show

how many of the 1953 jurors were Negro. (R. 225). The

1953 jury questionnaire forms have been destroyed. (R.

289). John Cowart, Clerk, identified the names of 22

jurors on the 1953 list who are Negroes and do not have

red C’s by their names. (R. 251-257). Using the race in

formation on the 1959 accepted and rejected jury question

naire forms for comparison, the secretary to the United

States Attorney found an additional 97 Negro names with

out red C’s by their names. (R. 285-287). It is not possible

to say how many more Negroes there might be on the 1953

list. (R. 288, 291).

c. Pre-1953 Jury Lists.

“No evidence was introduced concerning the compila

tion of jury lists prior to 1953.

22

d. Selecting Grand and Petit Juries.

“The 1,985 names are placed and remain in a jury

box. The Court goes into open court, the jury box is

opened, and the judge picks name slips (containing only

name, age, occupation and address) from the jury box,

handing them in the order picked to a Marshal, who in

turn hands each name to a typist. After the typist has

prepared the jury list, the name slips are placed in a sealed

envelope which is marked to be opened two years from

date, and the sealed envelope is placed in the jury box.

(R. 246).

e. The Court in Overruling Defendant’s Motion Stated:

“The Court: All right. I am going to overrule

this motion. The Wiman case pays some considerable

attention to percentages, but there are other factors

in the Wiman case in addition to percentages, and

there are differences in the grand jury system of

selection and the result and the percentages relating

thereto in this case and in the Wiman case.

“Now just how far the Courts may go in the future

in looking at certain percentages and saying that will

do that won’t, and how much emphasis they are go

ing to pay to the matter of Negroes and Whites and

whether that is the controlling [590] element in the

percentages and in the ratio of representation on the

list I can’t say but I am satisfied, as counsel very com-

mendably concedes here, that there was no intentional

discrimination on the part of the Jury Commissioners

in this District. And while that is not controlling in

this case it is a factor of considerable importance.

23

“There are, perhaps, some practical difficulties in

selecting juries. For instance, in this case I don’t

know now how many questionnaires were sent out

to either White or Negroes. I don’t know what the

answers were to those questionnaires. I don’t know

how many Whites or many Negroes said ‘please don’t

put me on the list, please excuse me, my job will

interfere’, how many of them expressed a desire to

serve, how many expressed an unwillingness to serve.

“I may say this, that this jury list will be revised

from time to time. If the Negroes in this district

want to serve they can cooperate by giving to the

Jury Commissioners some reliable information about

themselves so that they can receive beyond any per-

adventure of a doubt all consideration that they are

entitled to receive. But that is a matter for the future.

“Taking this case as the facts present it and as

the law reads, I think I can not do anything except

overrule this motion.

“Now, do you have another one, perhaps a short

one? And I may just add to what I have been say

ing, I have heard a good bit of evidence about school

teachers. That might be a good [591] place to go for

information, probably would be, but it is a mighty

bad place to go to get a juror. The school teachers are

so busy that they will offer an excuse if you happen

to get one and he is summoned to court to serve. I

don’t doubt that they have an excuse. They ivant

to go back to the class room. I have had that ex

perience over and over and, of course, their excuse

would generally be honored if you had enough jurors

to serve without them.” (R. 293-294) Emphasis

added).

f. Statistical Information—1960 Census.

“Neither the Clerk nor the Jury Commissioner used

the 1960 census for any purpose other than the apportion

ment of the total number of jurors by counties. Neverthe

less, in looking at the Macon Division realistically and in

evaluating the evidence on jury selection, one must realize

that according to the 1960 census and in particular ex

cerpts therefrom—Appendix B, the Macon Division is

situated in the State of Georgia, a State whose people

have completed the following median years of education:

The eighteen (18) Macon Division counties contain 373,594

people of whom 39% are non-white. Of the total number,

„~204,321 are over 21 and 35% of those are non-white.

I 38.9% of the white and 11.6% of the non-white persons 25

J years and older have completed four years of high school

| or more.

“Even though its citizens are constantly working to

improve the economic status of all, we must realize that

in 1960 the Macon Division on an individual county for

county basis had a low of 20.6%, high of 67.2% and average

of 45.4% families whose total income was under $3,000.

All persons, including both white and non-white, had a

county by county median individual income ranging from

a county high of $3,418 to a low of $1,537, whereas just

the non-white individual income ranged from a county

high of only $1,036 to a low $657. All families—white

and non-white—including non-related individuals, had a

Urban Rural

(a) White persons 11.7 years

(b) Non-white persons 6.8

8.8 years

5.1

25

median income by county ranging from $5,051 to $1,907,

whereas the same for non-whites alone ranged from only

$2,174 to $1,204.

“It was in this State and Division—where all people

have less than a desired education and small incomes,

where the Negro population has the smallest share of edu

cation and income, and where the same comparative dif

ferences exist in all areas of life—that the jury box in

question was composed.

“2. The Law.

a. Statutory Law on Selection of Federal Jurors.

“Congress, as of 1959, had prescribed the following

criteria for federal jurors:

28 U.S.C. 1861. Qualifications of Federal jurors:

“Any citizen of the United States who has at

tained the age of twenty-one years and who has re

sided for a period of one year within the judicial dis

trict, is competent to serve as a grand or petit juror

unless—

“ (1) He has been convicted in a State or

Federal court of record of a crime punishable by

imprisonment for more than one year and his civil

rights have not been restored by pardon or amnesty.

“ (2) He is unable to read, write, speak, and

understand the English language.

“ (3) He is incapable, by reason of mental or

physical infirmities to render efficient jury service.

As amended Sept. 9, 1957, Pub. L. 85-315, Part V,

§ 152, 71 Stat. 638.”

26

28 U.S.C. 1862. Exemptions:

“The following persons shall be exempt from jury-

service:

“ (1) Members in active service in the armed

forces of the United States.

“ (2) Members of the Fire or Police depart

ments of any State, District, Territory, Possession

or subdivision thereof.

“ (3) Public officers in the executive, legisla

tive or judicial branches of the government of the

United States, or any State, District, Territory, or

Possession or subdivision thereof who are actively

engaged in the performance of official duties.’'

28 U.S.C. 1863. Exclusion or excuse from service:

“ (a) A district judge for good cause may ex

cuse from jury service any person called as a juror.

“ (b) Any class or group of persons may, for

. the public interest, be excluded from the jury panel

or excused from service as jurors by order of the

district judge based on a finding that such jury

service would entail undue hardship, extreme in

convenience or serious obstruction or delay in the

fair and impartial administration of justice.

“ (c) No citizen shall be excluded from service

as grand or petit juror in any court of the United

States on account of race or color.”

and the following manner of drawing the names of grand

and petit jurors:

27

28 U.S.C. 1864. Manner of drawing; jury commis

sioners and their compensation:

“The names of grand and petit jurors shall be

publicly drawn from a box containing the names

of not less than three hundred qualified persons at

the time of each drawing.

“The jury box shall from time to time be refilled

by the clerk of court, or his deputy, and a jury com

missioner, appointed by the court.

“Such jury commissioner shall be a citizen of

good standing, residing in the district and a well

known member of the principal political party in the

district, opposing that to which the clerk, or his

deputy then acting, may belong. He shall receive

$5 per day for each day necessarily employed in the

performance of his duties.

“The jury commissioner and the clerk, or his

deputy, shall alternately place one name in the jury

box without reference to party affiliations, until the

box shall contain at least 300 names or such larger

number as the court determines.

“This section shall not apply to the District of

Columbia.”

“In amending § 1861-4 in 1957 to eliminate state jury

qualifications from federal jurors, those who opposed the

[Church] amendment as enacted contended that the pro

vision does not go far enough:

“As Senator Douglas stated:

‘I may say that there are certain weaknesses in

the Church amendment. Although it removes the

28

disqualification that those who are incompetent to

serve on State grand and petit juries are incompetent

to serve on Federal juries it is still a fact that the

general procedure practice of selecting Federal juries

will not be changed in all probability. Nothing in

the amendment compels an affirmative change in the

practice of selecting juries, so that the likelihood is

that few Negroes will actually be called to serve on

juries.’ (Emphasis added). 103 Cong. Rec. 13250.

“Senator Clark went a step further and suggested the

affirmative action that was needed, Id., p. 13290:

‘It should require the nondiscriminatory selection

of jurors in proportion to the, population within the

district, without discrimination on account of race or

color.’ (Emphasis added).

and on pp. 13290-13291:

‘I suggest that unless strong mandatory language

is written into the proposed jury-trial amendment,

preferably in connection with section 1864, we shall

have done nothing more than to remove a qualifica

tion. That is good, but unless we put in place of that

qualification a requirement for the equitable, fair, and

just selection of jurors in proportion to their repre

sentation throughout the district, without concern for

race or color, I fear that we shall have done very

little to help the situation.’ (Emphasis added).

“Congress not only failed to include strong mandatory

language and a requirement for affirmative action, but as

indicated failed through its debates to even indicate that

it had any such intent. Chance v. United. States, 322 F.2d

29

201 (5th Cir., 1963); United States v. Greenberg, 200 F.

Supp. 382, 395 (S.D. N.Y. 1961).

b. Decisions of Federal Courts on State Jury Com

position Questions.

( 1 ) T h e S u p r e m e C o u r t.

“The Supreme Court of the United States beginning

in 1879—Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 308 and con

tinuing through recent decisions such as Arnold and Dixon

v. North Carolina, 32 U.S.L. Week. 4340 (U.S. Apr. 6, 1964),

in numerous cases has considered the deprivation of the

constitutional rights of Negro petitioners arising from the

exclusion of Negroes from state grand and petit juries.

“In Strauder v. West Virginia, supra, in considering

the case of a colored man and recently emancipated slave

who in 1874 having been indicted, tried, convicted and

sentenced for murder, complained that by state law only

white men could be grand and petit jurors, the Supreme

Court ‘observed that the first of these questions is not

whether a colored man, when an indictment has been pre

ferred against him, has a right to a grand or petit jury

composed in whole or in part of persons of his own race

or color, but it is whether, in the composition or selection

of jurors by whom he is to be indicted or tried, all per

sons of his race or color may be excluded by law, solely

because of their race or color, so that by no possibility

can any colored man sit upon the jury.’ (page 305, supra).

The Court reviewed the history of the adoption of the

Fourteenth Amendment and concluded that ‘its aim was

against discrimination because of race or color. As we

30

have said more than once, its design was to protect an

emancipated race, and to strike down all possible legal

discriminations against those who belong to it.’ Quoting

further from the Slaughter-House cases, 16 Wall. 36, ‘In

giving construction to any of these articles [amendments],

it is necessary to keep the main purpose steadily in view.

It is so clearly a provision for that race and that emer

gency, that a strong case would be necessary for its ap

plication to any other.’ (page 310, supra). And the Court

decided ‘Any State action that denies this immunity to

a colored man is in conflict with the Constitution,’ con

cluded the jury selection law discriminates against Ne

groes because of color and reversed in favor of petitioner,

(page 310, supra).

“Fifty-five years later the Supreme Court in Norris v.

Alabama, 1934, 294 U.S. 587, 589, was still saying:

‘Whenever by any action of a State, whether

through its legislature, through its courts, or through

its executive or administrative officers, all persons of

the African race are excluded, solely because of their

race or color, from serving as grand jurors in the

criminal prosecution of a person of the African race,,

the equal protection of the laws is denied to him, con

trary to the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution

of the United States. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100

U. S. 303; Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370, 397; Gibson

v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565. This statement was re

peated in the same terms in Rogers v. Alabama, 192

U. S. 226, 231, and again in Martin v. Texas, 200 U. S.

316, 319.’

31

“And today the principle is the same. Hernandez v.

Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954); Arnold and Dixon v. North

Carolina, supra.

“In the application of this basic constitutional principle

the Court has always been confronted with the question of

what it considers to be a prima facie evidentiary showing

of purposeful exclusion because of race. The evidence set

forth in each of the following cases where the court decided

there was a prima facie showing of purposeful racial ex

clusion, best illustrates what the Supreme Court deems

to be a sufficient prima facie showing:

Norris v. Alabama, supra, where the uncontradicted

testimony of men 50 to 76 years old showed that with

in their memory no Negro had served on any grand or

petit jury in the county in which the defendant was

indicted.

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940). From 1931

through 1938 of 384 grand jurors, 5 were Negroes; of

512 persons summoned for grand jury only 18 were

Negro; the custom being to take the first 12 names of

a 16 name list, of those 18 the names of' 13 appeared

last on the 16 name list; of the other five, 4 were num

bered between 13 and 16 and one was numbered 6;

only 5 Negroes ever served, one on each of 5 out of 32

grand juries; of those 5 the same individual served 3

times, so only 3 different individuals served; no

Negroes were on petitioner’s grand jury; the jury com

missioners admitted they did not select any Negroes.

Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400 (1941). Two of the

three jury commissioners whose duty it was to sum

mon 16 men, of whom 12 are selected for grand jury,

32

said they summoned white men known by them. An

Assistant District Attorney who had lived in Dallas

County 27 or 28 years and served as judge 16 years said

he never knew of a Negro being called to serve on

a grand jury.

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953). No Negroes

were on the jury panel. The evidence showed that in

the jury box names of qualified Negro jurors were

on yellow tickets and of white qualified jurors were

on white tickets.

Pierre v. Louisiana, 306 U.S. 354 (1938). The evi

dence showed the general venire to contain no Negro

names, and one-third of the population was Negro.

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954). It was

stipulated that Tor the past twenty-five years there

is no record of any person with a Mexican or Latin

American name having served on a jury commission,

grand jury or petit jury in Jackson County’.

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1957). An

all-white jury indicted the Negro defendant. Accord

ing to the evidence only one Negro had ever been

picked for grand jury duty within memory.

Arnold and Dixon v. North Carolina, supra. The

clerk of the trial court testified that ‘. . . in his 24

years as clerk he could remember only one Negro

serving on a grand jury, another having been selected

but excused’.

“In explaining the reasoning that supports such de

cisions, it was stated: ‘Our directions that indictments

be quashed when Negroes, although numerous in the com

munity, were excluded from grand jury lists have been

33

based on the theory that their continual exclusion indicated

discrimination and not on the theory that racial groups

must be recognized. Norris v. Alabama, supra; Hill v.

Texas, supra; Smith v. Texas, supra. The mere fact of in

equality in the number selected does not in itself show

discrimination. . .’. Akins v. Texas, 325 U.S. 398 (1944).

(Emphasis added).

“Percentage figures alone will not establish that

Negroes or any other cognizable class has been left off of

a jury panel to such an extent as to prima facie establish

intentional and systematic exclusion, Cassell v. Texas, 339

U.S. 282, 286 (1949), for ‘Fairness in selection has never

been held to require proportional representation of races

upon a jury. Virginia v. Rives, 100 U.S. 313, 322-323;

Thomas v. Texas, 212 U.S. 278, 282;’ Akins v. Texas, supra.

“The constitutional prohibition of purposeful exclusion

has also been expanded to mean that ‘An accused is en

titled to have charges against him considered by a jury in

the selection of which there has been neither [purposeful,

limited] inclusion nor exclusion because of race.’ Cassell

v. Texas, supra.

( 2 ) D e c i s io n s o f T h is C o u r t o n t h e C o m p o s it io n

o f S t a t e J u r ie s .

“On March 11, 1964 this court decided in Collins v.

Walker, 329 F.2d 100, that there was discrimination against

the accused because of his color where instead of present

ing his case to an all-white grand jury which was in session

at the time of his arrest, the accused was kept in jail for

six months at which time the same jury commissioners

34

purposely placed six Negroes on a list of twenty names

from which the district judge drew a grand jury of five

Negroes and seven whites. The case of the accused was

the only case presented to this grand jury.

“Before that this court considered the state jury com

position question in United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman,

(5th Cir. 1962) 304 F.2d 53, where the evidence showed

and the court considered that:

‘(a) The Grand Jury which indicted relator

included eighteen persons, none of whom were Negro,

‘(b) The petit jury of twelve persons which

tried and convicted relator included no Negroes.

‘(c) From October 5, 1948, through June, 1956,

there were twenty-eight grand juries of eighteen per

sons each. One Negro sat on each of three grand

juries and since January 6, 1953 (relator indicted in

1958 and tried in 1959) no Negro had been on a grand

jury.

‘(d) The jury rolls for the county contained

the following distribution of names by race and per

centage:

Total Negro

Sept. 30, 1955-Sept. 30, 1956 7,435 120

Oct. 1, 1956-Sept. 30, 1957 7,349 99

Oct. 1, 1957-Sept. 30, 1958 8,433 99 Negro

Oct. 1, 1958-Sept. 30, 1959 9,713 109 Percent’ge

32,930 427 1.3%

‘(e) Jury panels for the county contained the

following distribution of names by race and percent

age:

35

Total Negro

:Oct. 3, 1948-July 1, 1949 2,463 40

Oct. 2, 1949-July 1, 1950 2,343 29

Oct. 1, 1950-July 1, 1951 2,467 28

Sept. 30, 1951-July 1, 1952 2,456 16

Oct. 5, 1952-July 1, 1953 2,417 21

Oct. 4, 1953-July 1, 1954 2,401 16 Negro

Oct. 3, 1954-July 1, 1955 2,251 29 Percent’ge

16,798 139 0.82%

‘ (f) Prior to 1954 race was indicated on the jury

cards but no cards had racial marks after 1956. The

Jury Commissioners selected cards from the jury rolls

and thereby made up a jury box each time a judge

needed a jury box to select a jury from by lot.

‘(g) On the jury roll of approximately 9,000

names, about 600 names were replaced each year.

Therefore from the time racial marks were eliminated

(after 1956) until the grand jury which indicted re

lator was selected, at the most 1200 new names out

of 9,713 were added to the jury rolls. In reality the

jury rolls were only minutely changed from the time

when race was indicated on the jury rolls so that in

effect the Jury Commissioners were still discriminat

ing because of race.’

“The question T. Whether the all-white grand jury

. . . and the all-white petit jury . . . reflected a continuous

pattern of discrimination against Negroes . . .’ Id. p. 55,

was answered in the affirmative, the Court concluding

‘that the presence of no Negroes on the 18-man grand jury

which indicted Seals, and of two Negroes on the venire

of 110 persons from which came the petit jury which

36

convicted Seals and condemned him to death was not

a mere fortuitous accident but was the result of systematic

exclusion of Negroes from the jury rolls.’ Id. p. 67.

c. Decisions on the Composition of Federal Juries.

( 1 ) T h e S u p r e m e C o u r t .

“ ‘The deliberate selection of (all women) jurors from

the membership of (only one) particular private organiza

tions definitely does not conform to the traditional re

quirements of jury trial . . said the Court in comment

ing upon but not deciding one of the early challenges to

the composition of a federal jury. Glosser v. United States,

315 U.S. 60, 86 (1942).

“Dealing exclusively with a challenge to a federal jury

was the case of Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S. 217

(1945). There ‘both the clerk of the court and the jury

commissioner testified that they deliberately and inten

tionally excluded from, the jury lists all persons who

work for a daily wage’. Id. p. 221. In deciding that ‘the

evil lies in the admitted wholesale exclusion of a large class

of wage earners in disregard of the high standards of jury

selection,’ Id. at 225, the Supreme Court stated:

‘The American tradition of trial by jury, consid

ered in connection with either criminal or civil pro

ceedings, necessarily contemplates an impartial jury

drawn from a cross-section of the community. Smith

v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 130; Glasser v. United States,

316 U.S. 60, 85. This does not mean, of course, that

every jury must contain representatives of all the

economic, social, religious, racial, political and geo

graphical groups of the community; frequently such

37

complete representation would be impossible. But it

does mean that prospective jurors shall be selected by

court officials without systematic and intentional ex

clusion of any of these groups. Recognition must be

given to the fact that those eligible for jury service

are to be found in every stratum of society. Jury

competence is an individual rather than a group or

class matter. That fact lies at the very heart of the

jury system. To disregard it is to open the door to

class distinctions and discriminations which are ab

horrent to the democratic ideals of trial by jury.

‘The choice of the means by which unlawful dis

tinctions and discriminations are to be avoided rests

largely in the sound discretion of the trial courts and

their officers.’ Id. at 220.

“Bottoming its decision on Thiel v. Southern Pacific

Co., supra, a reversal was ordered in Ballard v. United

States, 329 U.S. 187 (1946), because women were excluded

from grand and petit federal juries, the court saying again,

‘The evil lies in the admitted exclusion of an eligible class

or group in the community in disregard of the prescribed

standards of jury selection’. Id. at 195. ‘The gist of our

ruling is contained . . .’ in the portion of Thiel quoted in

the preceding paragraph of this brief. Id. at 192. And

for the first time the Court held specifically that ‘. . . re

versible error does not depend on a showing of prejudice

in an individual case’. Id. at 195.

“Like the cases pertaining to state juries, the Supreme

Court as to federal jury questions requires evidence of

systematic and intentional exclusion.

38

( 2 ) T h e C ir c u it C o u r t s o f A p p e a l .

“Appellant and many others have urged upon this and

other courts that Thiel should be interpreted like it was

interpreted by the Third Circuit, to mean that more is re

quired of federal jury officials than that they not inten

tionally and systematically exclude any groups. They de

sire that Thiel also mean, as the Third Circuit Court stated

(we think erroneously), that what is required is that jury

officials not exclude “through neglect as well as through

intentional conduct”. Dow v. Carnegie-Illinois Steel Cor

poration, 224 F.2d 414 (3rd Cir., 1955). Such an argu

ment, of course, is founded upon the theory that federal

jury officials are guided affirmatively, as well as neg

atively, in their selection of jurors.

“The statutes (in 1955 and now) provide no affirma

tive requirements of the officials in gathering names for

the jury box. . . . In fact, some standard system to be fol

lowed was advocated by certain of the senators in the

debates over the Civil Rights Act of 1957, and the criticism

of the present system advanced was that there was no

such requirement. See Congressional Record, Vol. 103,

Pt. 10. The Congress did not, however, adopt these argu

ments and the law as it now stands places the officials

under no mandatory or positive commands; they are, on

the contrary, controlled by one negative requirement:

they may not discriminate, directly or indirectly.” (Em

phasis added). Chance v. United States, 322 F.2d 201, 205

(5th Cir., 1963).

39

“This court also answered the contention that accord

ing to Thiel exclusion results when juries do not represent

£a literal cross-section, of the community’ by stating:

‘At the most, the notion of a jury as a cross-sec

tion of the community is a conceptual one. A literal

cross-section is neither required nor desired. Those

persons who have been convicted of a crime and not

pardoned, those not competent in the English language,

and those mentally or physically infirm are disquali

fied under 18 U.S.C.A. § 1861. Many people and classes

are granted exemptions and exclusions under 28

U.S.C.A. §§ 1862, 1863. In many sections of this coun

try, a Spanish-speaking community is predominant. An

English-speaking jury is certainly not a “cross-section”

of such a community.’ Chance v. United States, supra,

Id. at 204.

d. The Jury System As Envisioned by the Judicial

Conference and the Justice Department.

“Among the twenty-one recommendations concerning

the selection of jurors and operation of the jury system,

made by a committee of district judges and approved by

the Judicial Conference of the United States in 1960,

were the following which are significant to our case:

T. In order that grand and petit jurors who

serve in United States district courts may be truly

representative of the community, the sources from

which they are selected should include all economic

and social groups of the community. The jury list

should represent as high a degree of intelligence, mo

rality, integrity, and common sense as possible.

‘II. The choice of specific sources from which

names of prospective jurors are selected must be en-

40

trusted to the clerk and jury commissioner, acting

under the direction of the district judge, but should

be controlled by the following considerations: (1)

the sources should be coordinated to include all groups

in the community; (2) economic and social status in

cluding race and color should be considered for the

sole purpose of preventing discrimination or quota

selection; . . The Jury System in the Federal

Courts, 26 F.R.D. 409, 421.

“After receiving the endorsement of the Judicial Con

ference of the United States at its September, 1962, meet

ing a draft bill ‘to improve and strengthen as well as to

provide uniformity in the jury selection process,’ was

transmitted to the Congress on January 25, 1963, by the

Honorable Robert F. Kennedy, Attorney General. Ap

pendix C. The proposed bill provides: ‘The sources of

the names and the methods to be used by the jury com

mission in selecting the names of persons who may be

called for grand or petit jury service shall be as directed

by the chief judge. The procedures employed by the jury

commission in selecting the names of qualified persons

to be placed in the jury box shall not systematically or

deliberately exclude any group from the jury panel on

account of race, sex, political or religious affiliation, or

economic or social status. . . .’ Id. § 1864(b).

e. Burden of Proof.

“It is, of course, incumbent on the defendant as the

moving party to offer distinct evidence in support of its

motions. Where a defendant submits formal affidavits and

there is no actual or implied stipulation by the prosecution

41

that affidavits may be accepted as proof, it is still incum

bent on the defendant to produce distinct evidence. De

fendant’s formal affidavits alone, even though in some in

stances uncontradicted, are not enough. Smith v. Missis

sippi, 162 U.S. 592; Tarrance v. Florida, 188 U.S. 519; cf.

Brownfield v. South Carolina, 189 U.S. 426; Glasser v.

United States, 315 U.S. 60, 87 (1941).

“Proportions are meaningless when the evidence does

not show how many were qualified for jury duty. Hoyt v.

Florida, 368 U.S. 57, 68 (1961).

3. THE LAW APPLIED TO OUR CASE.

“The Jury Commissioner and the Clerk in 1959 had the

task of selecting 1,985 jurors from the 204,321 people over

21 in the Macon Division—the difficult job of navigating

an uncharted sea to find a ship containing less than 1%

(.9%) of the population.

And the Appellant complains of:

—What was done

—What was not done

“What did they do? The evidence shows clearly that

having no affirmative statutory guides or duties, the Jury

Commissioner and the Clerk using their best judgment

and with no idea of how many persons—male, female, Ne

gro, white, rich, poor or otherwise—should be included on

the jury, went about securing names of prospective jurors

from many varied sources throughout the division. They

got white and Negro names from white people and. recalled

42

specifically asking Negroes for names of Negroes. Having

no idea of how many names by race, job or any other de

scription, they had, questionnaires were next mailed to

between four and five thousand persons in the Macon Divi

sion. 2,500-3,000 questionnaires came back. On the ques

tionnaire was a place to indicate race—using the race

designation only to make sure that Negroes were included

and without any particular number of Negroes or whites

in mind, 1,985 names were selected from the questionnaires.

Four years later the Clerk and Commissioner still did not

know how many of the 1,985 names were of Negroes. Re

search for this case by the United States Attorney’s office

first established that of the 1,985 names, 117 or 5.9% were

Negro.

“Appellant, though contending . . . that there was a

historical pattern of jury racial discrimination, proved

nothing.

“The evidence shows . . . that the Jury Commissioner

and the Clerk did not either in 1959 or years gone by

purposely discriminate against Negroes in the selection of

jurors.

“And now on appeal the appellant noticing the testi

mony of the Jury Commissioner:

‘A. . . . I undoubtedly recited the qualifications

to them [persons furnishing prospective Negro jurors],

including the statutory qualifications plus our desire

here to have jurors of integrity and good character and

intelligence.’ (R. 96, Simmons),

infers that this testimony indicates that contrary to the

1957 amendment to the Civil Rights Act, which eliminated

43

state jury qualifications, the jury commissioner and clerk

in searching for jurors of integrity, good character and in

telligence have been guided solely by the Georgia law’s

requirement to select ‘upright and intelligent citizens to

serve as jurors.’ This is connected by argument to the

selection of persons able to understand the cases being tried

in the courtroom, and then the desire to have good jurors

is alleged to be unconstitutional. To the contrary— ‘The

jury list should represent as high a degree of intelligence,

morality, integrity and common sense as possible.” The

Jury System in the Federal Courts, supra, p. 421.

“The evidence also does not show purposeful inclusion

of only a few Negroes because of race.

“Failing to find either the purposeful exclusion or in

tentional inclusion because of race that is rightly con

demned as unconstitutional, Appellant takes another tack

and says, wait—what the commissioner and clerk failed

to do, is the real constitutional complaint. The jury com

missioner and the clerk, appellant thinks, should have used

other selection methods and thereby insured an actual

numerical cross-section of the community. Given the task

of selecting 666 federal jurors from a Bibb County popu

lation of approximately 85,000 persons over 21, undoubt

edly each of appellant’s attorneys, appellee’s attorneys, the

Judges on this Honorable Court and those who read this

brief would choose a different manner and method of

selection. Here the jury officials acted not unconstitu

tionally, but merely differently from the way appellant

personally thinks they should have acted.

* * *

44

“So it is that the United States respectfully submits

that an application of the statutory and case law to the

facts shows clearly that:

The jury commissioner and the clerk having no

affirmative statutory duties, complied fully with 28

U.S.C. 1861-4.

In the total absence of evidence of continual, his

torical exclusion of Negroes from the jury because of

race and in view of the clear evidentiary showing

that the commissioner and the clerk were not moti

vated by race to either purposely include or exclude

Negroes, there is no deprivation of Appellant’s con

stitutional privilege “to have charges against him

(her in this case) considered by a jury in the selec

tion of which there has been neither inclusion nor ex

clusion because of race.” Cassell v. Texas, supra.

“It having never been the law that a jury must rep

resent a literal, true cross-section of the community’s

economic, social, religious, racial, political and geo

graphical groups, Appellant in the absence of syste

matic and intentional exclusion of any of these groups,

has not had her constitutional rights violated.”

Appellants Jackson, Thomas, Wells, King and Chatmon,

like Appellant Joni Rabinowitz, have not had their consti

tutional rights violated.

45

V. CONCLUSION.

Wherefore it is prayed that the just, legal convictions

of the appellants be in all respects affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,