North Carolina Dept. of Transportation v. Crest Street Community Council Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

April 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. North Carolina Dept. of Transportation v. Crest Street Community Council Brief Amicus Curiae, 1968. 0bd814ba-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/df404352-3d48-4d8a-9556-c9e9239312f6/north-carolina-dept-of-transportation-v-crest-street-community-council-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

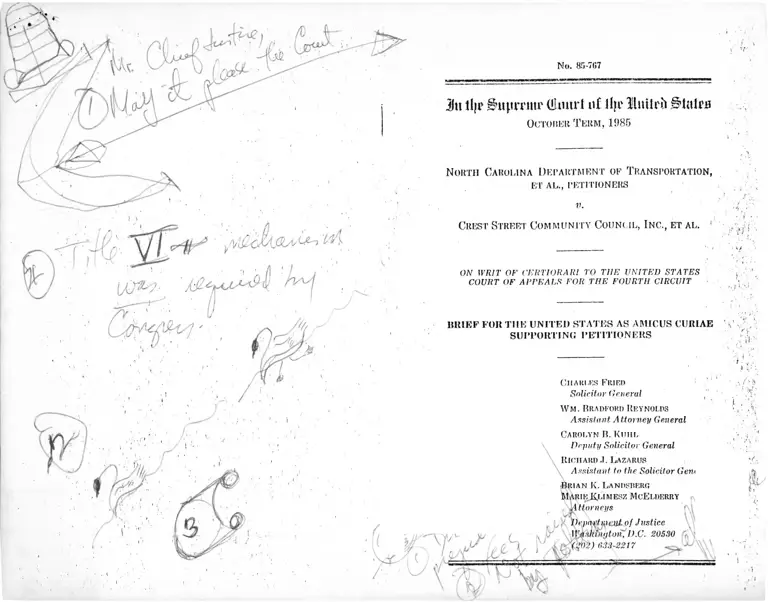

No. 85-707

jjtt il|i' ^upm ur (ihuui nf Jhik Muilrft ^luh'u

October Term, 1985

North Carolina Department of Transportation,

ET AL., PETITIONERS

V.

Chest Street Communi ty Council, Inc., et al.

‘■i ■ ■■ \j

ON WRIT OF' CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

SUPPORTING PETITIONERS

/

axXL___yLc— =4—csi

V c ' IkJ

Cl IA III. US FRIED

Solicitor General

W m . Bradford Reynolds

Assistant, Attorney General

Carolyn B. K uul

Deputy Solicitor General

Richard J. Lazarus

Assistant to the Solicitor General

Brian K. Landsherg

ilARIEjiUMESZ MCELDERRY

^Attorneys f\l\

* ............. W'u '/ Depart >\U’JiLof Justice

\VMkinuton,D.C. 20530 ' '

j 033-2217

_ _______

5K/

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether local community organizations are entitled

to recover their attorney’s fees under 42 U.S.C. 1988,

based on their having brought an alleged violation of

Title VI of the Civil Rights of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000d

et seq., to the attention of the appropriate federal

agency, and their having participated in informal

negotiations sponsored by the federal agency that re

sulted in a favorable settlement agreement.

(i)

Page

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of the United States............................................... 1

Statement.............................. 2

Summary of argument........................................................... 8

Argument:

Section 1988 does not authorize an award of attor

ney’s fees to complainants in Title VI administra

tive proceedings when their role is confined to noti

fication of the appropriate federal agency of a viola

tion of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and

to participation in informal agency-sponsored nego

tiations that result in a favorable settlement agree

ment ....................................... - ............................................ 11

A. Title VI administrative complainants are not

“part[ies]” to a “proceeding” to enforce Title

VI within the meaning of Section 1988 ................ 13

B. Application of Section 1988 to Title VI adminis

trative proceedings is inconsistent with the ra

tionale of the decisions of this Court implying a

private right of action to enforce Title VI and

threatens to disrupt agency enforcement efforts.. 24

Conclusion ................................................................................ 30

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Adams v. Bell, 711 F.2d 161, cert, denied, 465 U.S.

1021 .............................. 24

Alexander V. Choate, No. 83-727 (Jan. 9, 1985)..... 1

Arriola V. Harville, 781 F.2d 506........... 23

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677....2,17, 21,

24, 29

Chmvdhury V. Reading Hospital & Medical Center,

677 F.2d 317 ............................................................... 21

(III)

• Cases—Continued:

IV

Page

2Consolidated Rail Cm p. V. Darrone, 465 U.S. 624...

Guardians A ss’n V. Civil Service Comm’n, 463 U.S.

582 ......................................................................................2, 24, 25

Hensley V. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 ........... 29

New York Gaslight Club, Inc. V. Carey, 447 U.S.

54 ........................................................................... 6 ,7 ,1 9 ,2 0 ,2 6

Pennhurst State School & Hospital V. Halderman,

451 U.S. 1 ........................................ -............................... 26

Regents of the University of California V. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 .................................................................... 24, 25

Webb V. County Bd. of Educ., No. 83-1360 (Apr.

17, 1 9 8 5 )..................................................... 7, 10, 19, 20,28, 29

Statutes, regulations and rules:

Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. 551(3).... 22

Civil Rights Act of 1964:

42 U.S.C. 2000d et seq.......................................1, 2, 3, 8, 11

42 U.S.C. 2000d.............................................. 8

42 U.S.C. 2000d-l......................................................9 ,1 2 ,1 4

42 U.S.C. 2 0 0 0 e -5 (f)................................................. 20,21

42 U.S.C. 2000e-5 (f) ( 1 ) ........................................... 26

42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(g).................................................. 21

42 U.S.C. 2000e-5 (k ) ...............................................6 ,19 , 26

Education Amendments of 1972, 20 U.S.C. 1681

et seq.................................................................................... 2

Equal Access to Justice Act:

5 U.S.C. 504 .................................................................. 9, 22

28 U.S.C. 2412(d )....................................................... 9

28 U.S.C. 2412(d) (e ) ................................................ 22

Federal-Aid Highway Act, 23 U.S.C. 109(h) ........... 3

National Environmental Policy Act, 42 U.S.C. 4331

et seq.................................................................................... 3

Rehabilitation Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. 701 et seq. :

29 U.S.C. (Supp. V 1975) 7 9 4 ............................... 2

29 U.S.C. 794a............................................................ 2

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1973c............. 23

42 U.S.C. 1973J................................................................... 23

28 U.S.C. 1 3 2 ....................................................................... 19

28 U.S.C. 1 4 3 ....................................................................... 19

28 U.S.C. 1 5 1 ....................................................................... 19

V

Regulations and rules— Continued: Page

28 U.S.C. 1251........................................................................ 19

28 U.S.C. 1358 ....................................................................... 19

28 U.S.C. 1692....................................................................... 19

28 U.S.C. 1875(d) ( 2 ) ......................................................... 20

28 U.S.C. 1915....................................................................... 19

28 U.S.C. 1921 ....................................................................... 19

28 U.S.C. 2462 ...... 19

42 U.S.C. 1983........................................................................ 7 ,19

42 U.S.C. 1988 ............ passim

42 U.S.C. 3601 et seq............................................................ 3

7 C.F.R. Pt. 1 5 ....................................................................... 15

Section 1 5 .8 (c ) ............................................................ 16

Section 15.66................................................................. 16

13 C.F.R. Pt. 1 1 2 .................................................................. 15

15 C.F.R. Pt. 8 ....................................................................... 15

Section 8.11 (a) ............................................................ 16

22 C.F.R. Pt. 1 4 1 ................................................................... 15

24 C.F.R.:

Pt. 1 ................................................................................. 15

Pt. 2 :

Section 2 .2 3 ......................................................... 16

28 C.F.R. Pt. 42 Subpt. C ................................................. 15

29 C.F.R. Pt. 31..................................................................... 15

32 C.F.R. Pt. 3 0 0 ................................................................. 15

34 C.F.R.:

Pt. 1 00 ............................................................................. 15

Section 100.7(d) ................................................ 16

Pt. 101:

Section 101.23 ..................................................... 16

38 C.F.R. Pt. 1 8 .................................................................... 15

Section 18b.l 8 ....... 16

41 C.F.R. Pt. 101-6.2.......................................................... 15

43 C.F.R. Pt. 1 7 ................................................................... 15

45 C.F.R.:

Pt. 8 0 ............................................................................... 15

Section 80.7(d) .................................................. 16

VI

Regulations and rules— Continued: Page

Pt. 81:

Section 81 .23 ....................................................... 16

Pt. 1 203 ........................................................................... 15

49 C.F.R. Pt. 21 .................................................................. 15

Section 21.5(b) (3) .................................................... ' 4

Section 2 1 .1 1 ................................................................ 16

Section 21.11 (b) ......................................................... 15,17

Section 21.11 ( c ) .......................................................... 4 ,15

Section 21.11 (d) (1) .................................................. 4

Section 21.11 (d) (2 ) ................................................... 16

Section 2 1 .1 3 ............................................. 16

Section 21 .15 ................................................................. 16

Section 21.15 ( a ) .......................................................... 16

Section 21.17 ........................... 16

Exec. Order No. 12,250, 3 C.F.R. 298 (1 9 8 0 )............. 2, 15

Fed. R. Civ. P. 17-25 ........................................................... 23

Miscellaneous:

122 Cong. Rec. (1976) :

p. 3 5116 .......................................................................... 18

p. 35124 .......................................................................... 18

29 Fed. Reg. 16273-16309 (1964).................................... 15

H.R. Rep. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976)....... 20, 28

S. Rep. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976)............ 20

Hit lljr §ujtrnttP (Smtrt nf % luitrft §latrs

October T erm, 1985

No. 85-767

North Carolina Department of Transportation,

ET AL., PETITIONERS

v.

Crest Street Com m unity Council, Inc., et al .

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE U N ITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

SUPPORTING PETITIONERS

IN TER EST OF TH E U NITED STATES

Federal agencies have the primary enforcement re

sponsibility under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000d et seq., for ensuring that any

program or activity receiving federal financial as

sistance does not unlawfully discriminate on the basis

of race, color, or national origin. Accordingly, fed

eral agencies have promulgated implementing regula

tions setting forth Title VI investigation and enforce

ment procedures. As this Court has frequently noted,

the Department of Justice played a central role both

in the drafting of Title VI and in the development

of the various agencies’ implementing regulations.

See, e.g., Alexander v. Choate, No. 83-727 (Jan. 9,

(1)

2

1985), slip op. 7 n .l l ; Guardians Ass’n v. Civil Serv

ice Comm’n, 463 U.S. 582, 592 (1983) (opinion of

White, J . ) ; see also Exec. Order No. 12,250, 3 C.F.R.

298 (1980) (Department of Justice responsible for

approving and coordinating federal agency Title VI

programs). The issue in this case, whether attorney’s

fees are available under 42 U.S.C. 1988 for time

spent participating in agency enforcement proceed

ings, requires consideration of the nature of Title VI

administrative proceedings and the relationship of the

federal agency enforcement process to private Title VI

enforcement. If attorney’s fees are made available,

the enforcement scheme Congress created will be al

tered in a manner that threatens to interfere with

federal agencies’ administrative enforcement respon

sibilities.1

STATEM ENT

This case concerns whether a person who complains

to a federal agency that a recipient of federal funds

is engaging in discrimination in violation of Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000d

et seq., may recover attorney’s fees under 42 U.S.C.

1988 for time spent in informal negotiations spon

sored by the federal government to resolve those al

legations. Respondents are several local civic and

1 The federal interest in this case extends to federal agency

enforcement of both Title IX of the Education Amendments

of 1972, 20 U.S.C. 1G81 et seq., and Section 504 of the Re

habilitation Act of 1973, 29 U.S.C. (Supp. V 1975) 794, both

of which were generally patterned after Title VI (see Cannon

V. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677, 684-685 (1979) (Tit.

IX ) ; Consolidated Rail Corp. V. Darrone, 465 U.S. 624, 626,

632-633 n.13 (1984) (§ 5 04 )). The attorney’s fee provision

of 42 U.S.C. 1988 applies to Title IX and the attorney’s fee

provision of the Rehabilitation Act, 29 U.S.C. 794a, uses

language similar to that contained in Section 1988.

3

church organizations representing the interests of

residents of a stable, cohesive, predominately black,

neighborhood (Crest Street) in Durham, North Caro

lina (Pet. App. 2). They complained to the United

States Department of Transportation (USDOT) that

petitioners, two state transportation agencies and the

state official in charge of both agencies, had violated

Title VI. The merits of the dispute were entirely

resolved through USDOT’s informal conciliation ef

forts (id. at 22-25). Respondents then filed this law

suit for the sole purpose of recovering attorney’s fees

for time spent participating in the agency’s negotia

tion process. The district court dismissed the com

plaint for failure to state a claim, but the Fourth

Circuit reversed (id. at 1-21, 22-40).

1. In September 1978, two of the respondents sub

mitted a “ complaint” with USDOT alleging, inter

alia, that petitioners’ proposed highway extension

project would violate various federal environmental,

transportation, and civil rights laws, including the

National Environmental Policy Act, 42 U.S.C. 4331

et seq., the Federal-Aid Highway Act, 23 U.S.C.

109(h), and Titles VI and VIII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000d et seq., 3601 et seq.

(Pet. App. 23 & n .l; J.A. 73-96). Respondents sought

to prohibit further planning or construction of the

highway project by petitioners until the project was

brought into compliance with these federal laws (Pet.

App. 24). Respondents’ Title VI claim was based on

the allegation that the highway extension project was

receiving federal financial assistance and that its

proposed location would, by destroying the Crest

Street neighborhood, displace a disproportionately

large number of blacks (J.A. 80-81, 86).

4

2. Having received “ information indicat[ing] a

possible failure to comply with [Title VT]” USDOT

initiated an investigation of petitioners’ “ practices

and policies” (see 49 C.F.R. 21.11(c)) (Pet. App.

24). In February 1980, USDOT informed petitioners

that its investigation had resulted in a preliminary

finding of reasonable cause to believe that the pro

posed highway extension would be a prima facie vio

lation of Title VI and USDOT’s implementing regula

tions (Pet. App. 3, 24; J.A. 97-99).1a Accordingly,

USDOT pursued “ informal means” (see 49 C.F.R.

2 1 .1 1 (d )(1 )) resolving petitioners’ apparent non-

compliance by initiating informal negotiations with

petitioners (Pet. App. 4, 24). Representatives of the

Federal Highway Administration, the City of Dur

ham, and opponents of the highway, including re

spondents, participated in these negotiations (ibid.).

By February 1982, respondents and petitioners had

reached a preliminary agreement on freeway design,

relocation assistance benefits, and other assistance

to mitigate the project’s adverse impact, and were

continuing to negotiate on remaining aspects of al

leged discrimination (id. at 4, 25).

In August 1982, with negotiations ongoing, peti

tioners moved to dissolve a 1973 judicial decree that 2

2 The letter from USDOT referred specifically to 49 C.F.R.

21.5 (b) (3 ) , which provides:

In determining the site or location of facilities, a recipient

or applicant may not make selections with the purpose

or effect of excluding persons from, denying them the

benefits of, or subjecting them to discrimination under

any program to which this regulation applies, on the

grounds of race, color, or national origin; or with the

purpose or effect of defeating or substantially impairing

the accomplishment of the objectives of the Act or this

part.

D

had enjoined the proposed highway extension based

on noncompliance with various federal environmental

and transportation laws, unrelated to Title VI (Pet.

App. 5, 25). On October 15, 1982, respondents moved

to intervene in that pending judicial action, alleging

violation of federal environmental, transportation,

uniform relocation assistance, and civil rights laws,

including Title VI (ibid.’, J.A. 100-102). On De

cember 14, 1982, without ever having acted on re

spondents’ intervention motion, the district court en

tered a consent judgment dissolving the injunction

and dismissing the original lawsuit upon which the in

junction was based (Pet. App. 5-6; J.A. 153-157). The

consent judgment also announced that on November

19, 1982, respondents and petitioners had reached

agreement on those matters remaining in controversy

and, accordingly, respondents did not oppose dissolu

tion of the injunction, yet “ reserve[d] their claim for

attorney[ ’ ] s fees against [petitioners]” (Pet. App. 6

n.6; J.A. 155). Respondents signed the consent judg

ment in their capacity as applicants for intervention

(J.A. 156). Petitioners and respondents and the City

of Durham executed a Final Mitigation Plan, which

provided respondents with substantial relief, in a pub

lic ceremony the day after the court order (Pet. App.

6; J.A. 108-130).

3. On November 30, 1983, respondents filed this

action against petitioners for recovery of attorney’s

fees based on 42 U.S.C. 1988 (Pet. App. 27; J.A.

3-52). Respondents claimed they were “prevailing

parities']” within the meaning of that statutory pro

vision and, accordingly, entitled to recovery of at

torney’s fees (J.A. 8-9). The fee request covered

five years and eight months— from the date re

b

spondents first hired legal counsel to the date of the

announcement of the Final Mitigation Plan— and

totaled 1,261.25 hours of attorney time, all but 87

hours of which was time spent prior to the motion to

intervene, and over half of which occurred prior to

initiation of the USDOT informal conciliation process

(Pet. App. 30; J.A. 10-52).

The district court granted petitioners’ motion to

dismiss for failure to state a claim and for judgment

on the pleadings (Pet. App. 22-40). The court held

that Section 1988 does not authorize an award of at

torney’s fees for work performed in Title VI federal

agency administrative proceedings (Pet. App. 35-36).

The court distinguished on several grounds this Court’s

ruling in New York Gaslight Club, hie v. Carey, 447

U.S. 54 (1980), that identical language relating to at

torney's fees for private enforcement of Title VII (see

42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(k)) did include work performed in

Title VII state administrative proceedings (Pet. App.

33-34). In particular, the district court noted that

for Title VI, unlike Title VII, exhaustion of adminis

trative remedies is not required prior to filing a pri

vate lawsuit, those remedies “ not [being] integral

parts of [respondents’ ] federal court remedy” (id. at

34, 35 ).3 According to the district court, “ adminis

trative proceedings under Title VI * * * seem par

ticularly unsuited for an award of fees because in

dividuals, beyond filing an administrative complaint,

have little input or control into the decisional process”

(ib id .); the complainant “ is not a mandatory party

to the USDOT investigation nor to any action or in

3 The court rejected (Pet. App. 36-37) respondents’ conten

tion that it was reasonable for them to believe in September

1978 (the date respondents filed their administrative com

plaint) that exhaustion of administrative remedies was

necessary.

t

action taken with respect to the recipient of federal

funds” (id. at 37). Finally, the court concluded (id.

at 38) that respondents were not entitled to attorney’s

fees for the small portion of time allocated to the

effort to intervene in the pending district court law

suit. Specifically, the court found that “ there [was]

no evidence that the * * * effort[] * * * significantly

contributed to the execution of * * * [or] was even a

catalyst to the Plan” (id. at 39).

4. The court of appeals reversed (Pet. App. 1-

21). At the outset, the court noted that petitioners

“ concede that [respondents] gained substantial re

lief that was causally related to their administrative

complaint and that [respondents] therefore are ‘pre

vailing parties’ ” (id. at 8). The court went on to

hold (id. at 8-13) that the word “ proceeding” in Sec

tion 1988 embraced “ administrative proceeding,” re

lying on New York Gaslight Club, hie. v. Carey, su

pra, and that the USDOT proceeding initiated by re

spondents’ complaint was a “ proceeding to enforce”

Title VI, within the meaning of Section 1988. The

court of appeals reasoned, moreover, that federal ad

ministrative proceedings under Title VI could be

“ analogized to * * * mandatory [administrative] pro

cedures” because “ [t]hey are the primary and per

haps the only remedy for violation of * * * [T ] itle

[V I ]” (Pet. App. 13).

The court rejected petitioners’ contention that

Webb v. County Ed. of Educ., No. 83-1360 (Apr. 17,

1985), supported denial of respondents’ claim for

attorney’s fees. In Webb, this Court held that a

party who had prevailed in his 42 U.S.C. 1983 law

suit was not entitled to recovery of attorney’s fees

for time spent in state administrative proceedings

pursuing state law claims that related to the same

incident. The court of appeals concluded that Webb

8

stood for the proposition that administrative pro

ceedings could be the proper subject of a Section

1988 attorney’s fees claim so long as the procedures

were “ important parts of the statutory enforce

ment scheme [,•]” which, the court held, Title VI fed

eral administrative procedures were (Pet. App.

18). Finally, the court of appeals concluded that

Section 1988 authorized an independent action to

recover attorney’s fees for time spent in an adminis

trative proceeding, but that “ [e]ven i[ f ] some type

of court action were required to trigger § 1988’s fee

provision, [respondents] would still have a claim to

fees by virtue of their proposed complaint and mo

tion to intervene in the [pending district court]

action” (id. at 20).

SUM M ARY OF ARGUMENT

The court of appeals’ decision below, awarding re

spondents attorney’s fees under Section 1988 for

time spent in Title VI administrative proceedings,

misapplies 42 U.S.C. 1988 and rests on a misconcep

tion of the role of private parties, such as respondents,

in Title VI administrative proceedings. Section

1988 provides that “ [i]n any action or proceeding to

enforce a provision of” certain civil rights laws, in

cluding Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. 2000d et. seq., the court may award the “ pre

vailing party” attorney’s fees as part of the party’s

costs. Title VI prohibits any discrimination on the

basis of race, color, or national origin in any program

or activity receiving federal financial assistance (42

U.S.C. 2000d) and, to that end, confers upon federal

agencies dispensing federal financial assistance the

primary responsibility for enforcing that mandate.

Specifically, Title VI authorizes each agency to termi

9

nate or refuse to grant financial assistance, or to

pursue other authorized means of achieving Title VI

compliance, upon an express finding (on the record)

of a Title VI violation, provided that the agency first

determines that Title VI “ compliance cannot be se

cured by voluntary means” (42 U.S.C. 2000d-l).

An individual or group may, as respondents did here,

set in motion a federal agency investigation and com

pliance review by notifying the agency of an alleged

Title VI violation, but the private complainant is not

a formal “ party” to those agency efforts, as required

by Section 1988, nor are the agency’s efforts to secure

voluntary means o f compliance “ proceeding^]” to

enforce Title VI, within the meaning of Section 1988.

By express congressional design, Title V i’s adminis

trative enforcement scheme relies on internal federal

agency proceedings, within which the agency, as in

vestigator and enforcer, possesses wide discretion to

devote investigation resources, promote conciliation

efforts, devise remedial schemes, and make funding

termination determinations.

Nor is there any basis for supposing that Congress

had a different understanding of the nature of Title

VI administrative proceedings when Congress enact

ed Section 1988. The legislative history surrounding

enactment of Section 1988 reveals that Congress in

tended that Section 1988 would apply only to private

Title VI enforcement actions brought in court; there

is no suggestion that Section 1988 would apply to

Title VI administrative proceedings, especially in

formal agency-sponsored negotiations, which are not

even within the embrace of an attorney’s fee provi

sion, such as the Equal Access to Justice Act, 5

U.S.C. 504, 28 U.S.C. 2412(d), that specifically al

10

lows awards for time spent in administrative pro

ceedings.

Section 1988 applies, in all events, only to an ad

ministrative proceeding that is an “ integral” com

ponent of private enforcement of federal civil rights

law (see Webb v. County Bd. of Educ., No. 83-1360

(Apr. 17, 1985), slip op. 6 ), and Title VI adminis

trative proceedings do not fit this description. Indeed,

a major consideration leading to this Court’s en

dorsement, with our support, of an implied private

right of action to enforce Title VI in court, was the

absence of a private administrative enforcement

mechanism in Title VI. The practical effect of re

spondents’ (and the court of appeals’ ) expansive

reading of private enforcement of Title VI would be,

however, to convert the federal agency enforcement

mechanism into the very avenue for private enforce

ment that this Court had assumed Title VI to lack.

Congress enacted Title VI pursuant to its power under

the Spending Clause and, consequently, the force of the

Title VI nondiscrimination mandate depends on a po

tential grantee of federal financial assistance accept

ing the funds, including the conditions attached to

their receipt. It is no doubt largely for this reason

that Congress instructed federal agencies to enforce

Title VI primarily through securing “ voluntary” com

pliance. Respondents’ view of the role of private en

forcement in administrative proceedings takes no ac

count of these significant congressional concerns and

threatens to undercut the effectiveness of Title VI.

Finally, any argument that our vieAV of private en

forcement of Title VI will promote the premature

filing of private lawsuits is without merit. The avail

ability of a private right of action to sue a recipient

of federal financial assistance in court is always lim

i t

ited by the federal agency’s right to use its admini

strative process to resolve the controversy either on

its own or, should the agency prefer, with the assist

ance of both the complainant and the recipient. Con

sequently, a preemptive filing of a lawsuit by a

complainant would not entitle the complainant to an

award of attorney’s fees in the event (as in this

case) that the federal agency efforts led to a favor

able resolution. Otherwise, private causes of action

to enforce Title VI, implied by the judiciary, could

usurp the federal agency enforcement mechanism of

Title VI, expressly created by Congress. We can not

suppose that Congress intended such a result in en

acting either Title VI itself or the attorney’s fee pro

vision of Section 1988.

ARGUM ENT

SECTION 1988 DOES N OT AUTHORIZE AN AW AR D

OF ATTO R N EY’S F E E S TO COM PLAINANTS IN

TITLE VI AD M IN ISTR ATIVE PROCEEDINGS W H E N

TH EIR ROLE IS CONFINED TO NOTIFICATION OF

THE APPROPRIATE FED ER AL AGENCY OF A VIO

LATION OF TITLE VI OF TH E CIVIL RIGHTS

ACT OF 1964 AND TO PAR TICIPATION IN INFOR

M AL AGENCY-SPONSORED NEGOTIATIONS TH A T

RESULT IN A FAVORABLE SETTLEM EN T AGREE

M ENT

The decision of the court of appeals below, revers

ing the district court’s dismissal of respondents’

claim for attorney’s fees, fundamentally misconceives

the federal agency administrative enforcement scheme

of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

2000d et seq., expressly created by Congress for the

investigation and resolution of allegations of Title

VI violations. The statutory language of Title VI,

its legislative history, and decisions of this Court re

12

fleet the settled view that the administrative enforce

ment process created by Congress is exclusively a fed

eral agency enforcement mechanism, in which private

parties, such as respondents, have no statutorily de

fined investigatory or enforcement role, and may par

ticipate only at the invitation of the appropriate fed

eral agency. Congress deliberately chose to provide

federal agencies with wide discretion in investigat

ing and remedying Title VI violations, largely in

response to the special nature of requirements, such

as those in Title VI, that depend on the recipient’s

continued acceptance of federal funding.

The court of appeals incorrectly assumed, however,

that Congress created the administrative enforcement

framework to provide for private enforcement of

Title VI. Under the court of appeals’ reading of

Title VI, private individuals or groups, such as re

spondents, have formal “ party” status in internal

federal agency enforcement and remedial efforts and

are entitled to an award of attorney’s fees for “ pre

vailing” based on their participation in agency ef

forts to resolve Title VI disputes. In this case, the

agency “ proceeding[s]” in which respondents partici

pated were a series of informal negotiations spon

sored by USDOT to promote, pursuant to explicit

statutory command (see 42 U.S.C. 2000d-l), “ volun

tary means” of Title VT compliance. We believe that

the court of appeals’ construction of Title VI is at

odds with congressional intent and would undermine

the ability of federal agencies to investigate allega

tions of Title VI violations and, if found, to remedy

the problem, particularly through voluntary means,

as required by the statute. Certainly, nothing in

Section 1988 supports such a dramatic reworking of

federal agency enforcement of Title VI. For this

reason, we support reversal of the decision of the

court of appeals below and agree with petitioners

that respondents’ claim for attorney’s fees should be

dismissed.

A. Title VI Administrative Complainants Are Not

“Partfies]” To A “Proceeding” To Enforce Title VI

Within The Meaning Of Section 1988

Respondents base their claim for attorney’s fees

on 42 U.S.C. 1988, which provides that “ [i] n any

action or proceeding to enforce a provision o f” cer

tain civil rights laws, including Title VI, the court

may award the “ prevailing party” attorney’s fees as

part of the party’s costs. Although we have no quar

rel with the notion that respondents’ cause “ pre

vailed,” in the sense that the Final Mitigation Plan

extends substantial relief to those interests repre

sented by respondents, we do not believe that respond

ents meet the remainder of Section 1988’s require

ments. Respondents participated in the informal ne

gotiations sponsored by USDOT, but without the

formal “ party” status required by Section 1988. And

those informal negotiations were, in all events, not

“ proceeding [s] to enforce * * * Title VI” within the

meaning of Section 1988.4 *

4 Examination of the record suggests that petitioners’ ap

parent concession below, noted by the court of appeals (Pet.

App. 8 ), that respondents were “ prevailing parties” was

directed to respondents’ “prevailing” status, and not to their

status as formal “parties.” As described by the court of

appeals, petitioners admitted only that respondents “ gained

substantial relief that was causally related to their adminis

trative complaint” (ibid.). W e do not read this “concession”

as disturbing the separate argument, relied on in part by the

district court (id. at 37), that respondents did not possess

formal “party” status in the informal negotiations sponsored

by USDOT.

14

The structure of Title VI makes clear that federal

agency enforcement proceedings are meant to focus

primarily on assuring the funding recipient’s com

pliance with Title VI rather than on providing indi

vidualized relief to victims of discrimination. Title

VI contemplates that the federal agency will func

tion in a classic law enforcement capacity, represent

ing the public interest rather than enforcing the

rights of particular complainants. The statute de

fines the funding recipient’s rights and the funding

agency’s enforcement tools, but it does not define any

role in the investigation or enforcement process for a

person who complains of the recipient’s conduct.

In Title VI, Congress conferred upon those federal

agencies dispensing federal financial assistance the

primary responsibility for ensuring that programs or

activities supported do not discriminate on the basis

of race, color, or national origin (42 U.S.C. 2000d-l).

Title VI authorizes each agency to terminate or re

fuse to grant assistance to a recipient of federal

financial assistance, or to pursue other authorized

means to achieve Title VI compliance, upon an express

finding on the record, after opportunity for hearing,

of a Title VI violation (ibid.). Termination of or

refusal to grant assistance is limited both to the par

ticular recipient (including any part thereof) found

to be in noncompliance, and to the particular pro

gram in which noncompliance is found. The statute

provides, moreover, that the agency may not take

remedial action until after advising the recipient of

the failure to comply and after determining that

“ compliance cannot be secured by voluntary means”

(ibid.).

Reflecting this express statutory mandate, the vari

ous federal agencies, with the advice and approval of

15

the Department of Justice (see Exec. Order No. 12,250,

3 C.F.R. 298 (1980)), have promulgated Title VI im

plementing regulations that establish an administra

tive procedural framework for using complaints as a

tool in Title VI enforcement rather than considering

complaint resolution as an end in itself. Typically, the

regulations outline an enforcement scheme that relies

on pre-commitment compliance reviews, periodic com

pliance reports, and compliance investigations (in

the event that subsequently acquired information sug

gests the possibility of a violation).6 Although

USDOT regulations, like those of most federal agen

cies, provide that the Secretary will investigate upon

receiving any “ information indicat[ing] a possible

failure to comply with [Title V I ]” (49 C.F.R. 21.11

( c ) ) , complaint by a person who claims to be a vic

tim of unlawful discrimination is only one possible

source of such information (49 C.F.R. 21.11(b)).

To effect compliance, the agency must first use “ in

formal” or “voluntary” compliance efforts before

resort to a formal adjudicatory hearing that could

6 See generally ACTION, 45 C.F.R. Pt. 1203; Department of

Agriculture, 7 C.F.R. Pt. 15; Department of Commerce, 15

C.F.R. Pt. 8 ; Department of Defense, 32 C.F.R. Pt. 300;

Department of Education, 34 C.F.R. Pt. 100; General Services

Administration, 41 C.F.R. Pt. 101-6.2; Department of Health

and Human Services, 45 C.F.R. Pt. 80 ; Department of Hous

ing and Urban Development, 24 C.F.R. Pt. 1 ; Department of

the Interior, 43 C.F.R. Pt. 17; Department of Justice, 28 C.F.R.

Pt. 42 Subpt. C ; Department of Labor, 29 C.F.R. Pt. 31; Small

Business Administration, 13 C.F.R. Pt. 112; Department of

State, 22 C.F.R. Pt. 141; Department of Transportation, 49

C.F.R. Pt. 21; Veterans Administration, 38 C.F.R. Pt. 18.

The first Title VI regulations were published on December 4,

1964. See 29 Fed. Reg. 16273-16309.

10

lead to a funding cut-off (49 C.F.R. 21.13)." In those

circumstances when evidence of discrimination has

been supplied by a person who claims to be a victim,

the regulations provide only that the complainant

should be advised of the results of USDOT’s investi

gation (49 C.F.R. 2 1 .1 1 (d )(2 )). Even when formal

administrative hearings are held, the complainant is

only advised of the time and place of the hearings

(49 C.F.R. 21 .15(a)). The complainant plays no

formal role in any of the administrative proceedings

(49 C.F.R. 21.11, 21.13, 21.15, 21.17). Indeed, the

regulations of many federal agencies explicitly pro

vide that a complainant is not a “ party” to any

agency proceedings resulting from his complaint.7

8 See also 7 C.F.R. 15.8(c) (Department of Agriculture);

15 C.F.R. 8.11(a) (Department of Commerce); 34 C.F.R.

100.7(d) (Department of Education); 45 C.F.R. 80.7(d)

(Department of Health and Human Services).

7 Those agencies that have formally promulgated detailed

Title VI procedural regulations expressly declare the nonparty

status of the complainant. See, e.g., 34 C.F.R. 101.23 (Depart

ment of Education) (“A person submitting a complaint pur

suant to [the Department’s complaint procedure] is not a

party to the proceedings governed by [these regulations], but

may petition, after proceedings are initiated, to become an

amicus curiae.” ) ; 7 C.F.R. 15.66 (Department of Agriculture)

(“ person submitting a complaint * * * is not a party” ) ; 24

C.F.R. 2.23 (Department of Dousing and Urban Development)

(same) ; 38 C.F.R. 18b.l8 (Veterans Administration) (same) ;

45 C.F.R. 81.23 (Department of Health and Human Services)

(same). The USDOT Title VI regulations, which do not

include such detailed procedural regulations, do not explicitly

declare the nonparty status of the complainant, but the im

port of the regulations is clear, given that the complainant

is provided with no formal role in any of the proceedings.

The nonparty status of a complainant is also confirmed by

the lenient standards established by the USDOT regulations

17

Thus, consistent with the deliberate congressional

statutory design, the administrative framework for

ensuring compliance with the Title VI nondiscrimi

nation mandate is primarily a mechanism for the

federal agency to ensure compliance with Title VI,

rather than an avenue for private enforcement. The

submission of a complaint by private entities, such

as respondents in this case, provides only one of

several means of triggering initiation of the federal

agency administrative compliance review and enforce

ment process. The proceedings that result remain

under the exclusive control of the federal agency,

within which the government, as investigator and

enforcer, possesses wide discretion to devote investi

gation resources, promote conciliation efforts, devise

remedial schemes, and make fund-termination de

terminations. As described by this Court in Cannon v.

University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677, 707 n.41 (1979)

(citations omitted), in the context of Title IX (which

was patterned after Title V I ) :

[The statute] confers a benefit on a class of per

sons * * * [but does not] assure those persons

the ability to activate and participate in the

administrative process contemplated by the stat

ute. * * * [T]he complaint procedure adopted by

[the federal agency implementing regulations]

does not allow the complainant to participate in

the investigation or subsequent enforcement pro

ceedings. Moreover, even if those proceedings

result in a finding of a violation, a resulting

for defining who can be a complainant. Under USDOT regula

tions, a person does not have to allege that he has been sub

jected to unlawful discrimination, or even that he represents

others who have been. (49 C.F.R. 2 1 .1 1 (b )). To be a com

plainant, it is enough to allege that “ any specific class of per

sons [is] be[ing] subjected to discrimination * * *” (ibid.).

XU

voluntary compliance agreement need not in

clude relief for the complainant. Furthermore,

the agency may simply decide not to investigate

— a decision that often will be based on a lack of

enforcement resources, rather than on any con

clusion on the merits of the complaint.

The decision of the court of appeals below, by

assuming complainants had formal “party” status,

misapprehended the true nature of the proceedings

and, as a result, misapplied Section 1988.

2. Examination of the legislative history surround

ing the enactment of Section 1988 further confirms

the view that Congress did not intend to apply Sec

tion 1988 to Title VI administrative proceedings.

During the 1976 debates on Section 1988 on the floor

of the House of Representatives, several members

questioned the significance of the reference in Sec

tion 1988 to Title VI, on the ground that it was not

clear that Title VI provided for a private right of

action. See 122 Cong. Rec. 35116 (1976) (remarks

of Rep. Q u ie); see also ibid, (remarks of Rep. Bau

man). Rather than suggest that Section 1988 would

apply to “ prevailing complainants” who participated

in the federal administrative process provided by

Title VI (then reflected in the implementing regula

tions of the various federal agencies), a major pro

ponent of the bill simply replied: “ This bill merely

creates a remedy in the event the courts determine

that an individual may sue under these statutes” (id.

at 35124) (remarks of Rep. Railsback); see also id.

at 35116 (same). No Member of Congress suggested,

or appears to have seriously contemplated, that Sec

tion 1988 would apply to Title VI apart from any

judicially created private right of action to enforce

Title VI in courts. Respondents, however, do not base

19

their Section 1988 claim for attorney’s fees on such a

judicially created private right of action to enforce

Title VI in court. Their novel claim is based instead

on participation in federally sponsored informal nego

tiations, available under the statute totally apart

from any private enforcement rights implied by this

Court subsequent to the enactment of Section 1988.

3. Contrary to respondents’ view (Br. in Opp. 9-

13), neither New York Gaslight Club, Inc. v. Carey,

447 U.S. 54 (1980), construing a virtually identical

attorney's fee provision applicable to Title VII (42

U.S.C. 2000e-5(k)), nor Webb v. County Bd. of

Educ., No. 83-1360 (Apr. 17, 1985), construing Sec

tion 1988 in the context of a claim for attorney’s

fees based on a successful action brought under Sec

tion 1983, supports respondents’ cause. Indeed, these

two decisions are better read as supporting no fee

award in the circumstances of this case. Most funda

mentally, although Carey certainly stands for the

proposition that the term “proceeding” in an attor

ney’s fee provision may include an administrative

proceeding, Webb makes clear that under Section

1988 a person is not automatically entitled to an

attorney’s fees award for participation in any ad

ministrative proceeding related to that person’s civil

rights claim.8 Instead, a court entertaining a Sec

8 The meaning of the term “proceeding” is not, of course,

generally confined to administrative proceedings and refers

more typically to types of judicial proceedings. See, e.g., 28

U.S.C. 1251 (original and exclusive jurisdiction lies in this

Court for “actions or proceedings” involving ambassadors and

other foreign officials and for “ actions or proceedings by a

State against citizens of another State or against aliens” ) ;

see also 28 U.S.C. 132, 143, 151, 1358, 1692, 1915, 1921, 2462.

For that reason, the inclusion of the term “ proceeding” in an

attorney's fee provision does not, by itself, compel the con

clusion that Congress intended to extend awards to all admin-

20

tion 1988 claim must consider the nature of the ad

ministrative proceeding, particularly whether the pro

ceeding is an “ integral” component of the private

enforcement scheme (Webb, slip op. G). As explained

in Webb (id. at 5-7), the prevailing litigants in Carey

were entitled to attorney’s fees for time spent in ad-

>ministrative proceedings only because those proceed

ings were an essential, indeed mandatory, part of

private enforcement of the relevant statutory scheme

(Title V II). In contrast, the prevailing litigant was

not entitled to attorney’s fees for time spent in the

administrative proceedings in Webb because they were

“ not any part of the proceedings to enforce § 1983”

(id. 6-7).

A similar comparison of the nature of the adminis

trative “ proceedings” at issue in this case to those in

Carey compels, as in Webb, the conclusion that Sec

tion 1988 does not authorize an award of attorney’s

fees to respondents. Here, unlike in Carey (447 U.S.

at 65; see 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(f)) and as in Webb *

istrative proceedings. For instance, 28 U.S.C. 1 8 7 5 (d )(2 ),

which provides for attorney’s fees awards to an employee who

prevails in his claim that an employer unlawfully discrim

inated against the employee based on his service on a jury,

refers to “ any action or proceeding,” even though the statute

nowhere contemplates any administrative proceedings. In

Carey, moreover, the Court looked not just to the word “pro

ceeding,” but more broadly to the legislative history and struc

ture of Title VII before concluding that administrative pro

ceedings were covered by the relevant attorney’s fee provi

sion (see 447 U.S. at 62-64). In contrast, as this Court noted

in Webb (slip op. 7 n.16), there are “ numerous references in

[Section 1988’s] legislative history to promoting the enforce

ment of the civil rights statutes ‘in suits,’ ‘through the courts’

and by ‘judicial process’ ” (quoting S. Rep. 94-1011, 94th

Cong., 2d Sess. 2, 6 (1976) ; IT.R. Rep. 94-1558, 94lh Cong.,

2d Sess. 1 (1 9 7 6 )).

21

(slip op. 6), respondents were not required to partici

pate in the administrative proceedings for which they

now claim entitlement to attorney’s fees. See, e.g.,

Chowdhury v. Reading Hospital & Medical Center,

677 F.2d 317, 322 (3d Cir. 1982) ( “ exhaustion of

the agency funding termination procedures * * * [is

not] a prerequisite to a private action” ), cert, denied,

463 U.S. 1229 (1983).° Even more importantly, how

ever, the relationship of the federal administrative

proceedings to the interest of the individual complain

ant is fundamentally different in Titles VI and VII.

The federal (and related state) administrative pro

ceedings under Title VII, unlike Title VI, are statu

torily designed to resolve the individual complainant's

claim of discrimination; the Equal Employment Op

portunity Commission (EEOC), for instance, is em

powered to bring civil suits on the individual’s behalf,

seeking reinstatement, back pay, and injunctive relief

(see 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(g)). Title VII, moreover,

specifically contemplates the EEOC “entering] into

a conciliation agreement to which the person ag

grieved is a party” (42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(f) (emphasis

added)).

In contrast, the Title VI administrative process, as

described above, is consciously directed not to the

interests of the individual complainant, but more

broadly concerned with the relationship of the fed

eral agency to the recipient of federal financial as

sistance. The complainant is not even a formal

“ party” even when the agency holds a formal ad-

0 As this Court has previously noted, the position of the

federal government has been that private enforcement of

Title IX (or Title V I) does not require prior exhaustion of

administrative remedies. See Cannon V. University of Chicago,

441 U.S. at 687-688 n.8.

ministrative hearing, much less when the agency con

ducts “ informal” negotiations and “voluntary” con

ciliation. The complainant may participate only

when invited by the federal agency. Hence, while

the federal administrative framework of compliance

review and enforcement is an essential part of Title

VI enforcement, it is not an “ integral” component of

frrivcLte Title VI enforcement; Section 1988 applies

only to the latter circumstance.

4. Finally, we note that an extension of the scope

of attorney’s fee awards to include informal agency

negotiations, such as those that took place in this

case, would be unprecedented. Even in the Equal

Access to Justice Act, 5 U.S.C. 504, 28 U.S.C. 2412

(d ) (3 ) , where Congress expressly authorizes attor

ney’s fee awards for time spent in administrative

proceedings, the scope of the term “ proceedings” is

limited to adversary adjudications and does not em

brace informal agency proceedings, such as the in

formal negotiations at issue in this case. Fee awards

under the Equal Access to Justice Act are further

limited to a “ party” to the adjudicatory proceedings

(ibid.), which, as described above, is a status respond

ents did not possess.10

10 The Equal Access to Justice Act defines “ party,” by refer

ence to the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. 5 51(3 ), as

“a person or agency named or admitted as a party, or prop

erly seeking and entitled as of right to be admitted as a

party * * * [or] admitted by an agency as a party for limited

purposes.” Respondents would not meet this definition. If

every person who complained to a federal agency about a vio

lation of Title VI automatically became a party to the federal

compliance review and enforcement process, the administra

tive scheme would become so cumbersome as to be ineffective.

A recent Fifth Circuit decision, Arriola v. Har-

ville, 781 F.2d 506 (1986), construing Section 14 of

the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. 1973Z,

similarly cuts against respondents’ claim for attor

ney’s fees. Section 14 of the Voting Rights Act con

tains an attorney’s fee provision virtually identical

to Section 1988, authorizing fees to a prevailing party

in “ any action or proceeding to enforce the voting

guarantees” of the Constitution (42 U.S.C. 1973J)-

In Arriola, the Fifth Circuit concluded that indi

viduals who participate in the preclearance process

under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C.

1973c, are not entitled to an award of fees, relying

on the nonadversary nature of the preclearance proc

ess and the limited role of third parties in the process

(781 F.2d at 510). The Fifth Circuit stressed several

factors, including how (1) “ ‘action or proceeding’

commonly refers to some sort of adversary proceed

ing in the nature of a traditional lawsuit” (ibid. ) ;

(2) “ [t]he preclearance process was developed * * *

to avoid a judicial decision” (ibid, (emphasis in

original)); and (3) “ interested individuals and

groups have none of the rights o f parties” (ibid.).

These same factors are present in this case and

equally support dismissal of respondents’ Section 1988

claim.

Just as there are rules that govern who may be a party to a

lawsuit (see Fed. R. Civ. P. 17-25), so too there must be a

procedure for limiting the parties to the federal administra

tive process. That respondents participated in the agency’s

informal conciliation efforts did not, moreover, convert the

federal administrative process into an alternative forum for

the complainant to engage in an adversary “proceeding” with

the federal-aid recipient, within the meaning of Section 1988.

B. Application Of Section 1988 To Title VI Administrative

Proceedings Is Inconsistent With The Rationale Of

The Decisions Of This Court Implying A Private Right

Of Action To Enforce Title VI And Threatens To Dis

rupt Agency Enforcement Efforts

1. Denial of respondents’ attorney’s fees claim

does not detract, moreover, from the important, yet

distinct, role o f private enforcement of Title VI en

dorsed by this Court. A majority of this Court, with

the urging of the federal government, has adopted the

view that there exists a “private right of action,”

implied by the judiciary, to enforce both Title VI and

Title IX against the recipients of federal funds. See

Regents o f the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265, 419-420 & n.26 (1978) (opinion of

Stevens, J.) citing U.S. Supp. Br. Amicus Curiae at

24-34 (Bakke) ; Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441

U.S. at 702 & n.33, 707-708 & nn. 41 & 42; see also

Guardians Ass’n v. Civil Service Comm’n, 463 U.S.

582, 593-595 (1983) (opinion of White, J .). Re

spondents, however, seek to expand and alter the role

of private enforcement of Title VI in a manner that

ignores the rationale of those earlier decisions and

that threatens to interfere with federal enforcement

efforts.

In particular, this Court allowed private rights of

action under Title VI in part to avoid “ the dis

ru ption ] of [agency’s] efforts efficiently to allocate

its enforcement resources” that a suit to compel either

agency investigation or termination of agency fund

ing would create (Cannon, 441 U.S. at 707 n.41).

The Court was also motivated by its understanding

of the nature of administrative agency enforcement,

which was not, by congressional design, intended to

protect the interests of the individual complainant

(ibid.; see also Adams v. Bell, 711 F.2d 161, 167

25

(D.C. Cir. 1983) ( “ [t]he primary mechanism [for

private enforcement] is a Title VI suit against the

{recipient] itself” ), cert, denied, 465 U.S. 1021

(1984)). The Court discounted the potential for

interference between the express congressional fed

eral agency enforcement scheme and private rights

of action, implied by the judiciary, on the ground,

suggested by us, “ that if the possibility of inter

ference arises in another case, appropriate action can

be taken by the relevant court at that time” (441

U.S. at 706 n.41).

The practical effect of respondents’ expansive read

ing of private enforcement of Title VI, however,

would be to convert the federal agency enforcement

mechanism into an avenue for private enforcement,

ignoring the original impetus for implying private

rights of action and also interfering with the express

congressional agency enforcement scheme.11 While

the potential for such interference always offers a

reason for limiting a judicially implied private right

of action, the need is especially great in a case, such

as this one, which arises in the context of congres

sional exercise of its power under the Spending

Clause. “ This is because the receipt of federal funds

under typical Spending Clause legislation [such as

Title VI] is a consensual matter: the State or other

grantee weighs the benefits and burdens before ac

cepting the funds and agreeing to comply with the

conditions attached to their receipt” (Guardians Ass’n

v. Civil Service Comm’n, 463 U.S. at 596 (opinion of

11 See University of California V. Bakke, 438 U.S. at 419

n.26 (opinion of Stevens, J.) (“ Arguably, private enforcement

of th[e] ‘elaborate mechanism’ [for federal agency enforce

ment] would not fit within the congressional scheme.” ) (cita

tions omitted).

2(3

White, J . ) ; cf. Pennhurst State School <6 Hospital v.

Halderman, 451 U.S. 1, 17-18 (1981)). No doubt

for this reason, in Title VI, Congress instructed the

federal agencies to rely in the first instance on in

formal conciliation efforts and voluntary means of

compliance to resolve Title VI violations. Respond

ents’ view of the role of private enforcement, includ

ing application of Section 1988 to their participation

in informal agency-sponsored negotiations, takes no

account of these significant congressional concerns

and would unduly expand the role of private enforce

ment of Title VI in a manner that threatens the pre

eminent federal enforcement role.12

12 There is also no clear authorization for a lawsuit, such as

respondents’, filed for the sole purpose of recovering attorney’s

fees under Section 1988. The plain words of Section 1988 do

not appear to contemplate such a filing; the statute merely

provides a court with discretion to award the prevailing party

attorney’s fees “ [i]n any action or proceeding to enforce

* * * * Title V I” (42 U.S.C. 1988). Respondents, however,

have not filed this action “ to enforce * * * Title V I” and, con

sequently, do not appear to fall within the terms of the stat

ute. To be sure, this Court has (in dicta) previously inti

mated in the context of reviewing the attorney’s fee provision

applicable to Title VII (42 U.S.C. 2000e-5(k)) that “ [i]t

would he anomalous to award fees to the complainant who is

unsuccessful or only partially successful in obtaining [admin

istrative] remedies, but to deny an award to the complainant

who is successful in fulfilling Congress’ plan that federal poli

cies be vindicated at the [administrative] level” (Carey, 447

U.S. at 66 ; but see id. at 70-71 (Stevens, J., concurring)).

These concerns, however, are not so weighty in the Title VI

context where the administrative enforcement framework is

not (as discussed previously) an indispensable element of

private enforcement. Title VII, moreover, expressly authorizes

a civil suit in federal court (see 42 U.S.C. 2000e-5 (f) (1 ) ) ,

while private enforcement of Title VI depends on a right of

27

In this case, for example, there were never any

formal agency administrative proceedings. Instead,

USDOT initiated informal negotiations with peti

tioners, respondents, and other groups interested in

the highway project, as part of the agency’s efforts

to promote voluntary means of compliance. It is

hardly consistent with the informal or voluntary

nature of those negotiations to suggest that partici

pation of complainants, such as respondents, triggers

the attorney’s fee provision of Section 1988. Indeed,

application of Section 1988 would likely stifle mean

ingful informal settlement discussions, contrary to

Congress’ explicit wishes in Title VI. Rather than

working freely with others to reach a consensus posi

tion, complainants who have a potential ability to

recover attorney’s fees may be more likely to adopt

an adversary posture consistent with the expectation

that they would ultimately be reimbursed for their

expenses. For this reason, the prospect that fees

could be recovered against the recipient might lead

to a refusal to allow the complainant to participate

in the negotiations (leaving the federal agency and

the recipient to work out the agreement)

2. Finally, respondents may argue that our theory

of the relationship between private and federal agency

enforcement would have the effect of scuttling effec-

action implied by the judiciary; consequently, maintenance of

respondents’ lawsuit depends on a further expansion of the

scope of private rights of action under Title VI.

,s Alternatively, should complainants continue to participate,

application of Section 1988 could change the ultimate terms

of the agreement; the recipient, knowing that it faces the

prospect of attorney’s fees, could simply be less willing to

agree to incur expenses associated with the merits of the

dispute.

tive informal negotiations by promoting the prema

ture filing of lawsuits by parties who wish to be in

a position to recover their attorney’s fees. See H.R.

Rep. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 7 (1976) ( “A

‘prevailing party’ should not he penalized for seeking

an out-of-court settlement, thus helping to lessen

[court] congestion.” ). “ We cannot assume[, how

ever,] that an attorney would advise the client to

forego an available avenue of relief solely because

§ 1988 does not provide for attorney’s fees for work

performed in the * * * administrative forum” (Webb,

slip op. 7 n.15). But, in all events, any such argu

ment would underestimate the full import of our view

of the proper relationship between private enforce

ment of Title VI and the federal administrative

framework for compliance review and enforcement

under Title VI.

Simply put, a complainant may not be required to

exhaust the federal administrative proceedings, but

the absence of an exhaustion requirement does not

place private judicial enforcement on an equal (let

alone higher) footing than federal agency enforce

ment. Rather, exhaustion is unnecessary only because

the administrative remedy, while central to Title VI

enforcement, was not intended to be an avenue of

private relief, not because private judicial enforce

ment can ignore the administrative enforcement

framework expressly created by Congress. Private

enforcement, which is permitted by inference from

the statutory scheme, should always be tempered by

the needs of the explicit statutory requirements of

federal agency administrative enforcement and com

pliance review. Hence, if requested by the federal

government, a court should normally stay a private

Title VI enforcement action pending completion of

federal administrative efforts, including investiga

tion, conciliation efforts, and remedial determinations,

in order to avoid any potential interference between

private enforcement and the federal agency’s own

enforcement efforts. See Cannon, 441 U.S. at 687

n.8.14 A preemptive filing of a lawsuit by a com

plainant consequently would not necessarily entitle

the complainant to an award of attorney’s fees in the

event (as in this case) that the federal agency efforts

led to a favorable resolution. The availability of a

private right of action to sue a recipient in court does

not mean that a private complainant is completely

free to seek judicial relief without any regard to the

federal agency’s right, in the first instance, to make

reasonable efforts to resolve the controversy either

on its own or, should the agency prefer, with the

assistance of both the complainant and the recipient.

To be sure, under our view, private enforcement

might occasionally be stayed pending federal agency

enforcement efforts, but we believe that result is

consistent with the statutory scheme envisioned by

Congress when enacting Title VI.* * * 18

14 Of course, the converse is equally true. The federal agency

is not generally obliged to act first and may simply defer to the

private enforcement proceeding.

18 Of course, hypothetical circumstances may exist where a

private individual might be able to maintain a legitimate claim

for attorney’s fees for time spent in administrative proceed

ings under the theory that time spent in those proceedings

was “reasonably expended on the litigation * * *” (Webb, slip

op. 8 (emphasis in original), quoting Hensley v. Eckerhart,

461 U.S. 424, 433 (1983)). This would require at least a

showing that a “ discrete portion of the work product from

the administrative proceedings was work that was useful and

of a type ordinarily necessary to advance the * * * litigation”

(Webb, slip op. 9 ). Here, of course, there was no litigation

ou

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the court of appeals should be

reversed.

Respectfully submitted.

C harles F ried

Solicitor General

W m . B radford Reynolds

Assistant Attorney General

Carolyn B. K u iil

Deputy Solicitor General

R ichard J. L azarus

Assistant to the Solicitor General

B rian K. Landsberg

M arie K lim esz M cE lderry

Attorneys

A pril 1986

and, accordingly, such an alternative showing is not available

to respondents. Respondents’ effort to intervene in a pending

(non-Title V I) lawsuit, never acted on by the district court,

was incidental to the settlement agreement and does not sup

ply the necessary threshold “ litigation.” As the district court

found (Pet. App. 39), “ there is no evidence that the * * *

effort[] * * * significantly contributed to the execution of

* * * [or] was even a catalyst to the [Final Mitigation] Plan.”

f t U. R. ROVKRNMINT PRINTING OFMCI| 1 0 0 0 4 9 1 0 0 7 2 0 1 8 3