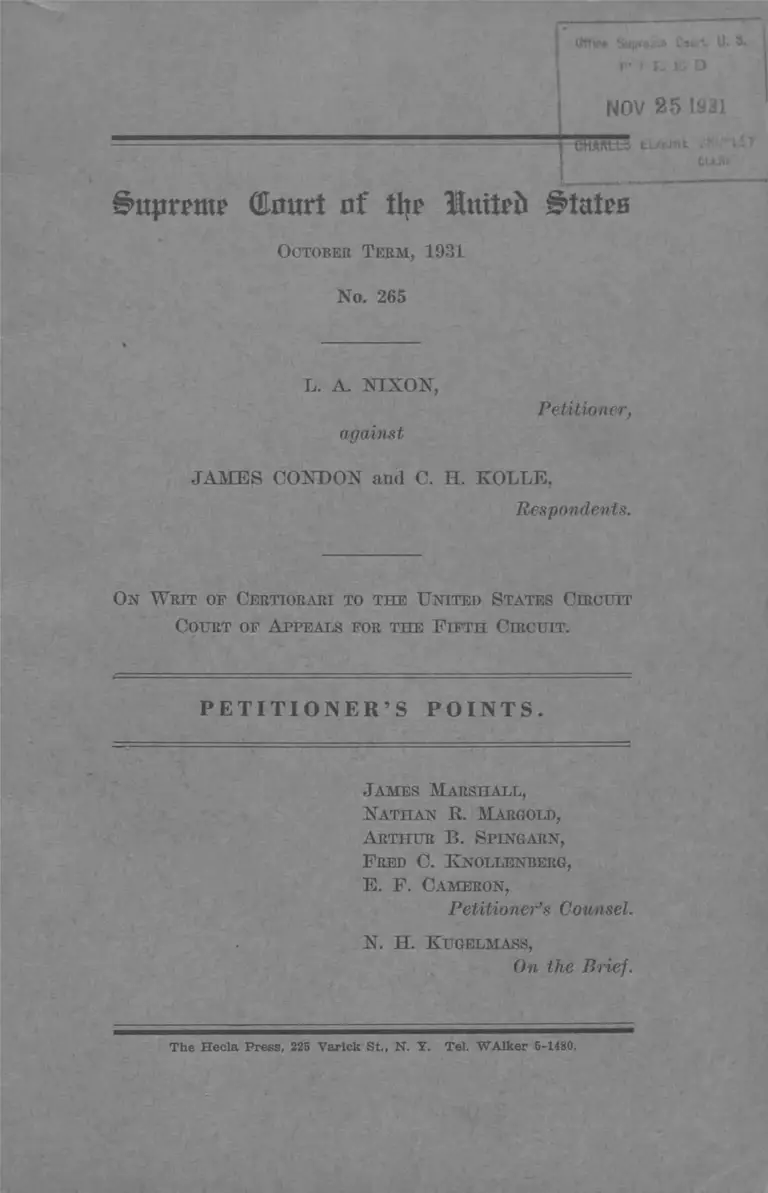

Nixon v. Condon Petitioner's Points

Public Court Documents

November 25, 1931

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Nixon v. Condon Petitioner's Points, 1931. 1ad6b2a1-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/df51eec6-0509-4011-97c6-742642d3d82f/nixon-v-condon-petitioners-points. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

Ufftee SupfSiii* Ciurt. U.

V' ' S, IS D

NOV 2 5 1931

fftMtUs tO*tnt . •

CM-S'

(Eourt of t\}t Ittiteb States

October Term, 1931

No. 265

L. A. NIXON,

Petitioner,

against

JAMES CONDON and C. H. NOLLE,

Respondents.

On W rit of Certiorari to the United States Circuit

Court of Appeals for the F ifth Circuit.

P E T I T I O N E R ’ S P O I N T S .

James M arshall,

N ath an R. Margold,

A rthur B. Spingarn,

F red C. K nollenberg,

E. F. Cameron,

Petitioners Counsel.

N. H. K ugelmass,

On the Brief.

The Hecla Press, 225 Varick St., N. Y. Tel. W Alker 5-1480.

SUBJECT INDEX.

PAGE

Preliminary Statement.................................................. 1

The Petition...................................................................... 2

The Resolution in Question.......................................... 3

The Statute in Question................................................. 3

Grounds of Demurrer..................................................... G

The Decision of the District Court............................. 0

The Decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals............ 7

Jurisdiction................................................................... . 8

Summary of Petitioner’s Argument............................... 13

P o i n t I—The interest protected in Nixon x. Herndon

was the right to vote in a primary and is the same

interest invaded here, and the classification rejected

by that case was based on race and color and is the

same classification applied here. The only question

before this Court is whether the invasion of this

interest and this classification were the result of

State action..................................................................15-17

P o i n t II—The petitioner in being deprived of the

right to vote at a primary because of his color was

denied the equal protection of the laws by the State

of Texas, in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment ......... ................................................................... 18-44

A. The power of respondents to deny petitioner’s

right to vote at the primary election was

derived from the resolution of the State

Democratic Executive Committee adopted

pursuant to authority granted by Chapter

67 of the Laws of 1927. Doth the statute

and the resolution adopted thereunder vio

lated the Fourteenth Amendment because

11

PAGE

they authorized and worked a classification

based on color............................................... 18-28

Legislative Intention................................ 18

The “Inherent Power” Argument........... 21

“ Recognition” of Power Argument........ 2G

B. Even if the Democratic State Executive Com

mittee in adopting the resolution restricting

voting at Democratic primaries to “white”

Democrats exceeded the powers delegated

to it by the Legislature in Chapter G7 of

the Laws of 1927, its action, though ultra

vires, constituted State action in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment because it

authorized and worked a classification

based on color...............................................28-31

C. The Democratic State Executive Committee,

acting in relation to primary elections, was

part of the governmental machinery of the

State. The resolution of that committee

restricting voting in Democratic primaries

to “white” Democrats was State action and

violated the Fourteenth Amendment and

afforded respondents no justification in de

nying to petitioner the right to vote........31-35

D. Respondents by reason of their office as judges

of election derived their power to deny the

petitioner the right to vote at the primary

election from the statutes of the State. In

applying that power to a State purpose in

such a way as to work a color classification

they violated the Fourteenth Amendment,

irrespective of Chapter 67 of the Laws of

1927 and the resolution of the Democratic

State Executive Committee......................35-44

Authority Vested in Judges of Election.. 36

Consequences of Abuse of Powers.......... 39

Expenses of Primaries.......................... 4:3

Ill

Foint III—The right of petitioner to vote in the pri

mal*}7 regardless of race or color was denied and

PAGE

abridged by the State of Texas, in violation of the

Fifteenth Amendment.................................................45-55

A Primary Vote is a Vote..................................... 45

Fifteenth Amendment Like Nineteenth................ 48

Historical Error...................................................... 49

The Newberry and Other Cases Distinguished.. 50

Petitioner’s Right to Vote Abridged Even if Not

Denied................................................................... 53

Point IV-—Conclusion................................................... 55-56

TABLE OF CASES.

Anderson v. Ashe, (52 Tex. Civ. App. 262..................... 52

Ashford v. Goodwin, 103 Tex. 491................................. 52

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U. S. 219................................... 18

Binderup v. Bathe Exchange, 263 U. S. 291............... 12

Bliley v. West (Circuit Ct.), 42 F. (2d) 101....... 8,32,56

Bliley v. West (District Ct.), 33 F. (2d) 177.............. 8

Briscoe v. Boyle, 286 S. W. 275 (Tex. Civ. A pp .). . .

23, 25, 26, 27, 32, 33, 48

Child Labor Tax Case, 259 U. S. 20............................. 18

Clancy v. Clough (Tex.), 30 S. W. (2d) 569... .27, 33, 43

Commonwealth v. Rogers, 63 N. E. Rep. 421 (Mass.) 48

Commonwealth v. Willcox, 111 Va. 849......................... 32

PAGE

Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U. S. 651............................... 49

Fidelity & Deposit Co. v. Tafoya, 270 U. S. 426.......... 28

Ford v. Surget, 97 U. S. 594......................................... 34

Friberg v. Scurry (Tex.), 33 S. W. (2d) 76.............. 27

General Investment Co. v. N. Y. Central R. R., 271

U. S. 228........................................................................ 12

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347......................... 21

Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 U. S. 251........................... 18

Hendricks v. The State, 20 Tex. Civ. App. 178, 49

S. W. 705...................................................................... 43

Home Tel. & Tel. Co. v. Los Angeles, 227 U. S. 278..

14,27, 28,29,31,34,35, 40

Hunt v. Reese, 92 U. S. 214................... ...................... 46

Kimbrough v. Barnett, 93 Tex. 301, 55 S. IV. 120 .... 43

King Mfg. Co. v. Augusta, 277 U. S. 100..................... 34

Koy v. Schneider, 110 Tex. 369.....................................52, 54

PACK

Lincoln v. Hapgood, 11 Mass. 350............................... 43

Lindgren v. United States, 281 U. S. 38....................... 22

Love v. Griffith, 266 U. S. 32.....................................8,10,11

Love v. Taylor (Tex.), 8 S. W. (2d) 795................... 27

Love v. Wilcox, 28 S. W. (2d) 515, 119 Tex. 256. . . .

19. 24, 26, 30, 31, 33

Moore v. Meharg, 287 S. W. 670 (Tex. Civ. App.) .. .34, 53

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368...............................8,21

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370..................................... 49

Newberry v. United States, 256 LT. S. 232... .14, 50, 51, 54

Nixon v. Condon (District Ct.), 34 F. (2d) 4 6 4 .... 1,6

Nixon v. Condon (Circuit Ct.), 49 F. (2d) 1012.... 1,7

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536... .4, 8,13, 15,16, 17, 45

Raymond v. Chicago Traction Co., 207 U. S. 20.......... 28

Robinson v. Holman, 181 Ark. 428; appeal dis., cert,

denied, 282 U. S. 805................................................ 11,56

Standard Scale Co. v. Farrell, 249 U. S. 571.............. 34

Swafford v. Templeton, 185 U. S. 487........................... 8

Turney v. Ohio, 273 U. S. 510......................................... 43

Waples v. Marrast, 108 Tex. 5, 184 S. W. ISO............ 34

Ward v. Love County, 253 U. S. 17............................... 8

Westerman v. Minims, 220 S. W. 178 (T ex.).............. 48

White v. Lubbock, 30 S. IV. (2d) 72 (Tex. Civ. App.) 27

Wiley v. Sinlder, 179 U. S. 58....................................... 8

Williams v. Bruffy, 96 U. S. 176................................... 34

Willis v. Owen, 43 Tex. 41............................................. 43

v i

Yarbrough, Ex parte, 110 U. S. 651............................. 49

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356................14,20,29, 41

TEXTS, LAW REVIEW ARTICLES, ETC.

PAGE

American Law Reports, 53: 595...................................

Bouvier’s Law Dictionary..............................................

Brown, Primary Disenfranchisement of the Negro,

23 Mich. Law Rev. 279.............................................32,53

Cornell Law Quarterly, 15: 267................................... 43

Funk & Wagnall’s Standard Dictionary..................... 46

Harvard Law Review, 43: 467................................. • • -3

Merriam & Overacker, Primary Elections (1928 Edi

tion ) ............................................................................32, 49

Michigan Law Review, 23: 279................................... 32, 53

Minnesota Law Review, 12: 321, 470...........................22,49

Sargent, Law of Primary Elections, 12 Minn. Law

Rev. 321, 470.............................................................. 22,49

Union League Club of Philadelphia, Essays on Poli

tics, 1868........................................................................ 49

University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 72: 2 2 2 .... 43

World Almanac................................................................ 53

Yale Law Journal, 39: 423......................................... 23

PROVISIONS OF CONSTITUTION.

Fourteenth Amendment.................5, 8,13,14,16, 29, 41, 56

Fifteenth Amendment................5, 6, 8,14,16, 29, 45, 53, 56

Nineteenth Amendment.................................................. 48

Article I, Section IV ......................... ..........................50, 51

FEDERAL STATUTES.

Judicial Code:

Section 24—

m ............................... ..................................... 5I1/ ......................................

..................................... 5,9

..................................... 5,12

(1 4 ) .................................... ..................................... 5,12

Revised Statutes

via

F ederal S t a t u t e s (continued)

United States Code:

Title 8—

Section 31.............................

Section 43.............................

Title 28, Section 41—

( 1) ......................................................

( 11) ...................................................................

( 12) ...................................................................

( 11) ...................................................................

PAGE

G, 8,10,14, 46

.............. 10

5,9

5.12

5.12

TEXAS STATUTES.

Laws of 1927, Chapter 67 (present Art. 3107, Rev.

Civ. Stat.).............................................2, 3, 4,16,18-31, 55

Tenal Code of 1925:

Title Six, Chapter 4—

Article 217............................................................. 38

Article 218............................................................. 38

Article 231............................................................. 38

Article 236.............................................................46,47

Article 241............................................................. 47

Generally............................................................38, 47, 48

Revised Civil Statutes of 1925:

Elections, Chapter 8—

Article 2954........................................................... 37

Article 2955........................................................... 38

Elections, Chapter 13—

Articles 3006-3007................................................. 36,37

Article 8093-a (former Art. 3107).....................4,15

Article 3104.......................................................... 36

Article 3107 (Chap. 67 of Laws of 1927)...........

2, 3, 4,16,18-31, 55

Article 3110 ...................................................... 22,33,48

Article 3121............................................................ 47

Generally.................................................................33, 36

Resolution of Democratic State Executive Commit

tee ..................................................2, 3,16,18-35, 39, 40, 55

Supreme (Court of tltr States

October T erm, 1931.

No. 265.

L. A. N i x o n ,

Petitioner,

against

J ames Condon and C. II. N olle,

Respondents.

PETITIONER’ S POINTS.

Preliminary Statement.

This case comes before this Court on writ of certiorari

to the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit, granted October 19, 1931 (R. 31), to review a

judgment entered in that court on May 16, 1931 (R. 30-31),

which affirmed a judgment of the United States District

Court for the Western District of Texas, filed July 31,

1929, dismissing the petition (R. 10).

The opinion of the District Court is printed in the

record at pages 15-27 and reported 34 F. (2d) 464.

The opinion of the Circuit Court of Appeals is printed

in the record at pages 28-30 and reported 49 F. (2d) 1012.

The petitioner, a citizen of the United States and of

the State of Texas, brought this action in the United States

District Court for the Western District of Texas against

the respondents, who were judges of election in Precinct

No. 9, El Paso County, Texas, to redress an injury which

he sustained by reason of the acts of the respondents in

their official capacities (R. 1).

The Petition.

The petitioner is a Negro. He was a bona tide member

of the Democratic Party of the State of Texas and in every

respect was entitled to participate in elections held within

that State, whether for the nomination of candidates for

office or otherwise (R. 2-3).

On July 28, 1928, a Democratic primary was held in the

State of Texas to select candidates, not only for State

officers, but also for United States Senator and Congress

men (R. 1-2). On that day the petitioner presented him

self at the polls and offered to take the pledge to support

the nominees of the Democratic primary election held on

that day and to comply in every respect with the valid

requirements of the laws of Texas, save as they violated

the privileges conferred upon and guaranteed to him by

the Constitution and laws of the United States, lie re

quested the respondents to supply him with a ballot and

permit him to vote at the Democratic primary election

held on that day and the respondents refused to permit

the petitioner to vote or to furnish him with a ballot and

stated as the reason that under instructions from the

Democratic county chairman, pursuant to resolution of

the State Democratic Executive Committee, adopted under

the authority of Chapter G7 of the Laws of 1927 of Texas,

only white Democrats were allowed to participate in the

Democratic primary then being held (R. 2-3). The re

spondents rilled that the petitioner was not entitled to

vote in the Democratic primary because he loas a Negro

(R. 3, 5). The resolution of the State Democratic Execu

tive Committee of Texas, under the terms of which re

spondents purported to act, reads as follows (R. 3) :

3

The Resolution in Question.

“ Resolved : That all white Democrats who are

qualified under the Constitution and laws of Texas

and who subscribe to the statutory pledge provided

in Article 3110, Revised Civil Statutes of Texas, and

none other, be allowed to participate in the primary

elections to be held July 28, 1928, and August 25,

1928, and further, that the Chairman and secretary

of the State Democratic Executive Committee be

directed to forward to each Democratic County

Chairman in Texas a copy of this resolution for

observance.” (Black type ours.)

The statute under the authority of which the Democratic

State Executive Committee adopted this resolution, Chap

ter G7 of the Laws of 1927, First Called Session (Article

3107, Chapter 13 of the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas),

gave authority to the State Executive Committee to pre

scribe qualifications of party members and determine who

shall be qualified to vote or participate in such political

party. The statute was passed as an “ emergency” meas

ure, because, as the statute itself proclaims, “the fact that

the Supreme Court of the United States has recently held

Article 3107 invalid, creates an emergency and an impera

tive public necessity that the constitutional rule requiring

bills to be read on three several days in each House be

suspended * * * ” (R. 4-5).

The Statute in Question.

“ A u t h o r i z i n g P o l i t i c a l P a r t i e s T h r o u g h S t a t e

E x e c u t i v e C o m m i t t e e s t o P r e s c r ib e Q u a l i

f i c a t i o n s o f T h e i r M e m b e r s .

(H. B. No. 57)

Chapter 67.

An Act to repeal Article 3107 of Chapter 13 of

the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas, and substi

tuting in its place a new article providing that

every political party in this State through its State

Executive Committee shall have the power to pre

scribe the qualifications of its own members and

shall in its own way determine who shall be quali

4

fied to vote or otherwise participate in such political

party, and declaring an emergency.

Be it enacted by the Legislature of the State of

Texas:

S f x t i o n 1. That Article 3107 of Chapter 13 of

the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas be and the same

is hereby repealed and a new article is hereby en

acted so as to hereafter read as follows:

‘A r t i c l e 3107. Every political party in this

State through its State Executive Committee

shall have the power to prescribe the qualifica

tions of its own members and shall in its own

way determine who shall be qualified to vote or

otherwise participate in such political party; pro

vided that no person shall ever be denied the right

to participate in a primary in this State because

of former political views or affiliations or because

of membership or non-membership in organiza

tions other than the political party.’

Sec. 2. The fact that the Supreme Court of the

United States has recently held Article 3107 invalid,

creates an emergency and an imperative public

necessity that the Constitutional Rule requiring

bills to be read on three several days in each House

lie suspended and said rule is hereby suspended, and

that this Act shall take effect and be in force from

and after its passage, and it is so enacted.

Approved June 7, 1927.

Effective 90 days after adjournment.”

The decision of this Court which was referred to by the

Texas Legislature was the case of Nixon v. Herndon, 273

U. S. 536, which held unconstitutional a statute of the

State of Texas which expressly prohibited Negroes from

participating in Democratic primary elections held in that

State.* It is alleged in the petition (and the history of

* The statute involved in Nixon v. Herndon, i.e., the old Article 3107:

“Article 3093a. All qualified voters under the laws and constitution

of the State of Texas who are bona fide members of the democratic party

shall be eligible to participate in any democratic party primary election,

provided such voter complies with all laws and rules governing party

primary elections; however, in no event shall a negro be eligible to par

ticipate in a democratic party primary election held in the State of Texas,

and should a negro vote in a democratic primary election, such ballot

shall be void and election officials are herein directed to throw out such

ballot and not count the same.” (Italics ours.)

5

the Act sustains the allegation) that Chapter 67 of the

Laws of 1927 was an attempt to evade the decision of this

Court in Nixon v. Herndon and to provide, by delegation

to the party Executive Committee, the disfranchisement of

Negroes which this Court held could not be done by direct

action of the Legislature (R. 5-6).

The petition also alleges that at the time of the passage

of Chapter 67 of the Laws of 1927 of Texas the Democratic

Party was the only political party in the State which held

a primary election and that the statute, when it referred

to the State Executive Committee, was enacted for the

purpose of preventing the petitioner and other Negroes

who were members of the Democratic Party from partici

pating in Democratic primary elections (Ii. 6). Further

more, the petition sets forth that there are many thousands

colored Democratic voters in the State of Texas situated

as is the petitioner; that Texas is a State which is nor

mally so overwhelmingly Democratic that nomination on

the Democratic ticket is equivalent to election, and that

the only real contest at the polls is that in the Democratic

primaries. And, finally, it is alleged that the acts of the

respondents in denying the petitioner the right to vote at

the Democratic primary in question were wrongful, un

lawful and without constitutional warrant and deprived

him of valuable political rights, to his damage in the sum

of $5,000 (R. 7-8).

This suit was brought under Section -11 of Title 28 of

the United States Code, subdivisions 1, 11, 12 and 14 being

applicable.

Judgment is demanded against the respondents (a) be

cause Chapter 67 of the Laws of 1927 of Texas and the

resolution of the Democratic State Executive Committee

thereunder denied the petitioner the equal protection of

the laws of Texas, in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States; (b) because

the petitioner’s right to vote at the primary election was

denied and abridged by the resolution of the Democratic

State Executive Committee and the action of the Legis

lature of Texas on account of his race and color, in viola-

G

tion of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution;

(c) because the resolution and statute in question are

contrary to Section 31 of Title 8 of the United States

Code; and (d) because the respondents, acting under a

delegation of State power, violated those sections of the

Constitution and that Act of Congress when they denied

the petitioner the right to vote on the ground that he is

a Negro (R. 6-7).

Grounds of Demurrer.

The respondents made a motion to dismiss. In addition

to controverting the allegations of the petition with respect

to the constitutionality of the statute and the proceedings

it was urged that the subject-matter of the suit is political

and that the Court was without jurisdiction to determine

the issues or to award the relief prayed for; that the alle

gations of the petition were not sufficient to constitute a

cause of action; that irrespective of statutory authority,

the State Executive Committee of a political party had

authority to determine who should comprise its member

ship. The motion also put into issue the allegation that

the petitioner was a Democrat (E. 8-10). The last ground

presents an issue of fact which could not be determined

on a motion addressed to the pleadings.

The Decision of the District Court.

Honorable Charles A. Boynton, District Judge, who

heard the motion, granted the motion to dismiss in an

opinion (R. 15-27, 34 F. [2d] 4G4) in which he said:

(1) that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States cannot be violated

except by some action properly to be characterized as State

action; (2) that Chapter G7 of the Laws of 1927 on its

face directs no action in violation of the Federal Constitu

tion; (3) that the action of the State Democratic Com

mittee and the judges of election, complained of in the

petition, was not State action, because (a) the members

of the committee and the judges of election were not paid

by the State, and so were not like the persons officiating

at the Illinois and Virginia primaries, who have been held

liable in damage to qualified citizens to whom they denied

the right to vote; (b) they were not officers of the State;

(c) they were acting only as private representatives of

the Democratic political Party, and (d) the members of

the Democratic Party possess inherent power to prescribe

the qualifications of those who may vote at its primaries,

irrespective of and without reference to Chapter 67 of

the Laws of 1927; and (4) that a primary election is not

an election within the meaning of the Fifteenth Amend-

ment, because (a) a political party is not a governmental

agency, and (b) at the time the Thirteenth, Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments were adopted, primary elec

tions were unknown and therefore may not be held to be

covered by these Amendments.

The Decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Circuit Court of Appeals, in affirming the District

Court, rendered an opinion by Bryan, C.J. (R. 28-30;

49 F. (2d) 1012), which held as follows: (1) that the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments apply to State ac

tion, not to action of private individuals or associations;

(2) that this case differs from Nixon v. Herndon, because

there the element of State action was supplied by the en

actment of a statute which expressly discriminated against

Negroes, whereas here the statute merely recognized an

existing power on the part of the Democratic State Ex

ecutive Committee to fix the qualifications of its members;

(3) that the election officials who rejected the petitioner

were appointed by the Democratic State Executive Com

mittee, and were not paid by the State, and (4) that the

decision in West v. Bliley is distinguishable because there

the State of Virginia conducted the primary and paid the

8

expenses thereof, whereas in Texas the State merely regu

lates a privately conducted primary election so as to secure

a fair and honest election.

Jurisdiction.

The jurisdiction of Federal Courts over this suit is pro

vided by Section 41, Title 28 of the United States Code

(Judicial Code, Sec. 24, as amended). It is there provided,

in subdivision 1, that the District Court shall have original

jurisdiction over “ * * * First. Of all suits of a civil

nature, at common law or in equity, * * * where the

matter in controversy exceeds, exclusive of interest and

costs, the sum or value of $8,000, and (a) arises under the

Constitution or laws of the United States, or treaties,

made or which shall be made, under their authority

* * * ??

This is a suit of a civil nature at common law for a sunt

in excess of $3,000 and the matter in controversy arises

under (1) the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States; (2) the Fifteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States; (3) Section 31,

Title 8 of the United States Code.

In similar circumstances this Court has assumed juris

diction.

Wiley v. Kinkier, 179 U. S. 58, G5.

Swafford v. Templeton, 185 U. S. 487.

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 3G8.

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 53G.

Ward v. Love County, 253 U. S. 17, 22.

Cf. Love v. Griffith, 26G U. S. 32.

In Bliley v. West, 42 F. (2d) 101, the Circuit Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit affirmed the order of the

District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia (33

F. (2d) 177, opinion by Groner, D.J.) overruling a de

9

murrer to a petition seeking the same relief as is sought

in this case. There, the Democratic State Convention,

like the Democratic State Committee here, adopted a

resolution that only white persons should participate in

Democratic primaries, and the petitioner, a Negro, was

not permitted to vote in a Democratic primary in the

State of Virginia. No attempt was made to bring that

case up for review by this Court.

The jurisdiction of this Court is not open to attack on

the ground that the subject-matter of the suit is “political.”

That argument was disposed of in Nixon v. Herndon,

supra*

Subdivision 11 of Section 41 of Title 28 of the Judicial

Code likewise gives a basis for jurisdiction by the Federal

Courts, for it authorizes suits for injuries on account of

acts done under the laws of the United States “ or to en

force the right of citizens of the United States to vote in

the several States.”

Subdivision 12 deals with suits concerning civil rights

and gives the District Courts jurisdiction “of all suits

authorized by law to be brought by any person for the

recovery of damages on account of any injury to his per

son or property or of the deprivation of any right or privi

lege of a citizen of the United States by any act done in

furtherance of any conspiracy mentioned in Section 47 of

Title 8.”

Subdivision 14 gives the Federal Courts jurisdiction

“ of all suits at law or in equity authorized by law to be

brought by any person to redress deprivation under color

of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage

of any State or any right, privilege or immunity secured

by the Constitution of the United States or of any right

secured by any law of the United States providing for

* See opinion o f Mr. Justice Holmes at page 540.

10

equal rights of citizens of the United States or of all per

sons within the jurisdiction of the United States.”

This is a suit at law to redress the deprivation of peti

tioner’s right to vote at a primary election in the State of

Texas. The deprivation was under color of a statute of

the State of Texas, to wit, Chapter 67 of the Laws of 1927,

and/or under color of a resolution adopted by the State

Democratic Executive Committee of Texas. The suit is

not only, however, to redress the deprivation of civil rights

by reason of the unconstitutional restraint upon the peti

tioner’s right of suffrage in violation of the Fourteenth

and Fifteenth Amendments, but it is also based specifically

upon the violation of a Federal statute, viz., Section 31,

Title 8 of the United States Code, which provides:

“ Section 31. Race, color, or previous condition

not to affect right to vote. All citizens of the United

States who are otherwise qualified by law to vote at

any election by the people in any State, Territory,

district, county, city, parish, township, school dis

trict, municipality, or other territorial subdivision,

shall be entitled and allowed to vote at all such

elections, without distinction of race, color, or pre

vious condition of servitude; any constitution, law,

custom, usage, or regulation of any State or Terri

tory, or by or under its authority, to the contrary

notwithstanding.”

Section 43 of Title 8 of the United States Code also

grants a right of action for violation of the right of fran

chise guaranteed by Section 31, supra.

It should be noted in this connection that not only can

didates for local office but also for United States Senator

and Congressman were nominated at the primary held in

Texas on July 28, 1928 (R. 2).

The authorities already cited demonstrate that in sim

ilar instances this Court has assumed jurisdiction.

In the recent case of Love v. Griffith, 266 U. S. 32, the

plaintiffs as qualified electors sought to enjoin as violative

of the Constitution the enforcement of a rule made by the

11

Democratic City Executive Committee of Houston, Texas,

that Negroes should not be allowed to vote at a particular

Democratic primary election. The injunction was denied

and the plaintiffs appealed to the Court of Civil Appeals

of Texas, which held that at the date of its decision,

months after the election, the cause of action had ceased

to exist and that the appeal would not be entertained on

the question of costs alone. The suit was brought to this

Court on writ of error and was dismissed, Mr. Justice

Holmes saying at page 34:

“If the case stood here as it stood before the

court of first instance it would present a grave

question of constitutional law and we should be

astute to avoid hindrances in the way of taking it up.

But that is not the situation. The rule promulgated

by the Democratic Executive Committee was for a

single election only that had taken place long before

the decision of the Appellate Court. No constitu

tional rights of the plaintiffs in error Avere infringed

by holding that the cause of action had ceased to

exist. The bill Avas for an injunction that could

not be granted at that time. There Avas no consti

tutional obligation to extend the remedy beyond

what was prayed.’’ (Black type ours.)

The “ grave question of constitutional law” which this

Court could not consider in Ix>ve v. Griffith, because in

that instance time had made the issue moot, has become

the vital point of conflict in the present suit.*

The Circuit Court of Appeals accepted jurisdiction of

this cause and decided the motion to dismiss upon the

merits without questioning the jurisdiction of the Federal

Court (R. 28-30).

The District Court after deciding the motion on the

merits evidently confused the question of jurisdiction and

the question of absence of merits in the discussion in the

last paragraph of the opinion (R. 27).

* Robinson v. Holman, 181 Ark. 428, appeal dismissed and certiorari

denied 282 U. S. 805, apparently on same grounds as Love v. Griffith.

12

This distinction between jurisdiction and merits has

been clearly set forth by this Court in Binderup v. Pathe

Exchange, 263 U. S. 291, at page 305,* and General Invest

ment Co. v. AT. Y. Central R. R., 271 U. S. 228, at page 230.f

As will be seen after the case of Nixon v. Herndon,

supra, has been analyzed the sole diffei*ence between that

case and this one is that there the respondents denied the

petitioner the right to vote at a Democratic primary be

cause the statute specifically forbade colored people to

vote in Democratic primaries, whereas in this case the

same petitioner was refused the right to vote at a Demo

cratic primary by the election officials on the ground that

a, resolution of the States Democratic Executive Commit

tee, adopted pursuant to authority granted by the Legis

lature, prohibited Negroes from voting at Democratic

primaries.

The only issue in this case is, then, the question of

whether the acts of the respondents was State action. If

it was State action, then Nixon v. Herndon is applicable.

This is clearly a question over which this Court has juris

diction. It presents a justiciable issue irrespective of the

merits of the contention. As the full nature of this issue

is demonstrated by the succeeding Points, for the sake of

brevity it will not be repeated here.

* In the Binderup case, Mr. Justice Sutherland said:

“Jurisdiction is the power to decide a justiciable controversy,

and includes questions of law as well as of fact. A complaint

setting forth a substantial claim under a federal statute presents

a case within the jurisdiction of the court as a federal court;

and this jurisdiction cannot be made to stand or fall upon the way

the court may chance to decide an issue as to the legal sufficiency

of the facts alleged any more than upon the way it may decide

as to the legal sufficiency of the facts proven. Its decision either

way upon either question is predicated upon the existence of juris

diction, not upon the absence of it.”

f i n the General Investment Company case, Mr. Justice Van Devanter

said:

“By jurisdiction we mean power to entertain the suit, consider

the merits and render a binding decision thereon; and by merits

we mean the various elements which enter into or qualify the

plaintiff’s right to the relief sought. There may be jurisdiction

and yet an absence of merits ( The Fair v. Kohler Die Co., 228

U. S. 22, 25 ; Geneva Furniture Co. v. Karpen, 238 U. S. 254, 258),”

* * *

13

We respectfully refer the Court to the ensuing argu

ment, not only as a demonstration of the merits of the

petitioner’s case, but also in support of the jurisdiction of

this Court.

Summary of Petitioner’s Argument.*

I. The interest protected in Nixon v. Herndon was the

right to vote in a primary and is the same interest invaded

here, and the classification rejected by that case was based

on race and color and is the same classification applied

here. There was no question in Nixon v. Herndon of State

action, that being implicit in the statute. That is the

only open question in this case under the Fourteenth

Amendment which was not disposed of in the former case.

II. The petitioner by being denied the right to vote at

the primary election because of his color was denied the

equal protection of the laws by the State of Texas in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The respond

ents’ action was action of the State of Texas, because—

A. The power of the respondents to deny the peti

tioner’s right to vote at the primary election was

derived from the resolution of the Democratic State

Executive Committee, which was adopted pursuant to

the authority granted to it by Chapter 67 of the Laws

of 1927. The respondents’ power was consequently

derived from the State and was not inherent in the

party.

B. Even if the Democratic State Executive Com

mittee in adopting the resolution restricting voting

at Democratic primaries to white persons exceeded

the powers delegated to it by the Legislature in Chap

* Even if the arguments made herein were all invalid, nevertheless the

petition alleges a cause of action which the State Court could not have

failed to entertain without itself violating the Fourteenth Amendment,

and of which the United States District Court had jurisdiction, in view of

the substantial Federal questions raised and argued herein. Having full

confidence in the arguments here presented, we do not wish unduly to

extend this brief and shall omit elaboration of this further argument

unless the Court requests otherwise.

14

ter G7 of the Laws of 1927, its action, though ultra

vires, was nevertheless State action.

C. The Democratic State Executive Committee,

acting in relation to primary elections, was part of

the governmental machinery of the State. In adopt

ing the resolution in question the action of the Com

mittee was State action and the resolution could not

therefore justify the denial of the petitioner's right

to vote.

I). Irrespective of Chapter 07 of the Laws of 1927

of Texas and the resolution of the Democratic State

Executive Committee the respondents, acting as

judges of election, when they denied the petitioner

the right to vote were applying to a public purpose

powers with which the State had vested them, and

consequently their action was State action as defined

in Home Tel. & Tel. Co. v. Ims Angeles, 227 U. S. 278,

and Tick Wo v. Hopkins, US U. S. 356.

III. The respondents’ denial of the petitioner’s right to

vote in the Democratic primary was in violation of the

Fifteenth Amendment.

(A) The same arguments with respect to State

action under the Fourteenth Amendment are appli

cable under the Fifteenth Amendment.

(B) The petitioner was both denied the right to

vote and his right to vote was abridged within the

meaning of the Fifteenth Amendment.

(C) The right to vote guaranteed by the Fifteenth

Amendment is not the same thing as an election re

ferred to in Article I, Section 4, of the Constitution

and Newberry v. United States, 256 U. S. 232, is inap

plicable.

(D) Section 31, Title 8, of the United States Code

prohibits discrimination by denying the right to vote

by reason of color and was violated by the action of

the respondents.

15

I.

The interest protected in Nixon v. Herndon was

the right to vote in a primary and is the same interest

invaded here, and the classification rejected by that

case was based on race and color and is the same

classification applied here. The only question before

this Court is whether the invasion of this interest and

this classification were the result of State action.

As the case at bar is really a sequel to Nixon v. Herndon,

273 U. S. 536, and in all respects except one identical with

that case, the determination of this question will be facili

tated by a preliminary consideration of Nixon v. Herndon

itself and a precise delimitation of the respects in which

it is controlling here.

There Nixon, the same petitioner, brought his suit in

the United States District Court for the Western District

of Texas to recover the sum of $5,000 in damages from the

judges of election, who, like the present respondents, had

refused to permit him to vote in a Democratic primary in

the State of Texas. The primary then, as in this case, was

held at El Paso for the nomination of candidates on the

Democratic ticket for United States Senator, for Repre

sentative to Congress and for State and local offices. Then,

as in this case, the judges of election refused to permit

the petitioner to vote in the Democratic party primary

solely because he was a Negro.

In that case it was sought to justify this discriminatory

classification based upon the petitioner’s color by a Texas

statute enacted in May, 1923, designated Article 3093-a

(the former Art. 3107, Texas Rev. Civ. Stat.), which pro

vided that “ in no event shall a negro be eligible to partici

pate in a Democratic party primary election held in the

State of Texas,” etc.

1G

Following the decision in Nixon v. Herndon that statute

was repealed and the new statute adopted.

Now the judges of election have sought to justify their

discrimination against the petitioner, based as it is on

his color, because of a resolution of the State Democratic

Executive Committee quoted supra, page 3, which was

adopted pursuant to Chapter G7 of the Laws of 1927 and

which restricts voting in Democratic primary elections to

“white Democrats.”

The statute of 1927 did not expressly render Negroes

ineligible to vote at Democratic primaries, but empowered

the State Executive Committees of such political parties

as held primary elections to determine who should be

qualified to vote at such primaries.*

In both cases petitioner contended that the deprivation

of his right to vote was in violation of the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments.

In that case, as in this case, the defendant judges of

election moved to dismiss the petition on the ground that

the subject-matter of the action was political, that it was

not within the jurisdiction of the court, that neither the

Fourteenth nor the Fifteenth Amendment nor any laws

adopted pursuant thereto applied to primary elections, and

that the petition failed to state a cause of action.

In Nixon v. Herndon this Court held:

(1) that it was unnecessary to determine whether

the petitioner was deprived of his right to vote within

the meaning of the Fifteenth Amendment, because he

had been deprived of civil rights under the Fourteenth

Amendment ;f

* The Democratic Party being the only party polling over 100.000 votes

in Texas was the only party required by law to hold primary elections.

t “The important question is whether the statute can be sustained. But

although we state it as a question, the answer does not seem to be open to

a doubt. W e find it unnecessary to consider the Fifteenth Amendment,

because it seems to us hard to imagine a more direct and obvious infringe

ment of the Fourteenth. That amendment, while it applies to all, was

passed, as we know, with a special intent to protect the blacks from dis

crimination against them” (pp. 540-541).

17

(2) that this deprivation of civil rights was accom

plished by an arbitrary classification, viz.: one with

out constitutional justification;*

(3) that this classification was the result of State

action ;f and

(4) that consequently the Fourteenth Amendment

was applicable and a common law right of action for

damages lay against the offending judges of election.^

The sole question before this Court is whether the action

of the respondents as judges of election in denying the

petitioner the right to vote was taken under State author

ity or was in effect action by the State itself. If this be so

the present case will then come within the category of

Nixon v. Herndon and the action of the respondents would

be without constitutional justification. In that event the

judgment appealed from must be reversed.

* “The statute of Texas, in the teeth of the prohibitions referred to,

assumes to forbid negroes to take part in a primary election the impor

tance of which we have indicated, discriminating against them by the

distinction of color alone” (p. 541).

f “States may do a good deal of classifying that it is difficult to believe

rational, but there are limits, and it is too clear for extended argument

that color cannot be made the basis of a statutory classification affecting

the right set up in this case” (p. 541).

$ “O f course the petition concerns political action but it alleges and

seeks to recover for private damage. That private damage may be caused

by such political action and may be recovered for in a suit at law hardly

has been doubted for over two hundred years, since Ashby v. White, 2 Ld.

Raym. 938, 3 id. 320, and has since been recognized by this Court. Wiley

v. Sinkler, 179 U. S. 58, 64, 65. Giles V. Harris, 189 U. S. 475, 485. See

also Judicial Code, Sec. 24 (1 1 ), (1 2 ), (1 4 ). Act of March 3, 1911, c.

231; 36 Stat. 1087, 1092. If the defendants’ conduct was a wrong to the

plaintiff, the same reasons that allow a recovery for denying the plaintiff

a vote at a final election allow it for denying a vote at the primary election

that may determine the final result” (p. 540, italics ours).

18

II.

The petitioner in being deprived of the right to

vote at a primary because of his color was denied the

equal protection of the laws by the State of Texas in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

A. The power o f respondents to deny peti

tioner’s right to vote at the primary election was

derived from the resolution of the State Demo

cratic Executive Committee adopted pursuant to

authority granted by Chapter 67 o f the Laws

o f 1927. Both the statute and the resolution

adopted thereunder violated the Fourteenth

Amendment because they authorized and worked

a classification based on color.

The language of the new Article 3107 as enacted by

Chapter 07 of the Laws of 1927 is broad enough to be an

authorization from the Texas Legislature empowering the

State Executive Committee of the Democratic Party to

determine, among other things, that only white Democrats

shall be qualified to vote at Democratic primary elections.*

If the Democratic Legislature of Texas could not con-

stitutionally forbid Negroes to vote at primaries in view

of the decision of this Court in Nixon v. Herndon, it could

nevertheless with a feeling of assurance entrust to the

Democratic State Committee power to enact such prohibi

tion and achieve the same end.f

Legislative Intention.

That it was the legislative intention to accomplish this

purpose and to evade and nullify that decision appears

from the face of the enactment. The statute expressly

indicates that the new' Article 3107 was being substituted

* See Chapter 67 of Laws of 1927, set forth in full at page 3, supra.

f This Court has held that a legislative body cannot accomplish by

indirection something which it is without power to do directly. Cf. Ham

mer v. Dagenhart, 247 U. S. 251, and Child Labor Tax Case, 259 U. S. 2Q.

And see Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U . S. 219.

19

for the one held unconstitutional, in order to take care of

the “emergency” created by the decision in Nixon v. Hern

don. What could this emergency be if not that Negroes

would be able to vote at the next primary election unless

some new method were devised to exclude them? If the

Legislature had intended to meet the emergency in such

a manner as to conform to, rather than circumvent the

decision of this Court which created the so-called emer

gency, it is unthinkable that the Legislature would not

expressly have stated in the new provision that the wide

language conferring authority on the Executive Committee

to determine who should vote at primary elections was

not to be construed to authorize the exclusion of Negroes

because of their race and color. The Legislature was ac

tively aware of the necessity of limiting the authority of

the State Committee, for it did .actually impose limitations

by the proviso which forbade the denial of the right to

vote at primary elections “because of former political

views or affiliations or because of membership or non

membership in organizations other than the political

party.” It would have been a simple matter to add the

words “ or because of race or color.” The failure of the

Legislature to do so in the light of the declared emergency

created by the invalidation of the former Article 3107

enacted in May, 1923, completely disposes of any and all

doubt as to the proper construction of the new statute of

1927. By providing that the Executive Committee “ shall

in its own way determine who shall be qualified to vote,”

Chapter 67 of the Laws of 1927 plainly delegated author

ity to the committee to determine among other things that

only white Democrats should be entitled to vote at Demo

cratic primary elections.*

* Senator Thomas P. Love, a member of the Texas Senate when Arti

cle 3107 was adopted in 1927, filed in his own behalf a brief in the Texas

Supreme Court in Love v. Wilcox, 28 S. W . (2d) 515, in which he was

plaintiff. In that brief he said that the statute had “no other purpose

whatsoever” than “to provide, if possible, other means by which Negroes

could be barred from participation, both as candidates and voters, in the

primary elections of the Democratic Party, which would stand the test

of the courts.” And see House Journal of First Called Session of the

Fortieth Legislature of Texas, at pages 302 ct seq., and arguments by

Representatives Faulk and Stout discussing Article 3107, which was House

Bill No. 57.

The Democratic State Executive Committee did “ in its

own Avay determine who shall be qualified to vote” by

providing that only “white Democrats” who are qualified

under the Constitution and laws of Texas and who sub

scribe to Article 3110 of the Revised Civil Statutes, should

have the right to vote in the primaries of July 28, 1928,

and August 25, 1928 (see Resolution supra, p. 3).

It would seem to follow as a matter of course that the

Democratic State Executive Committee was acting under

and pursuant to the authority which the Legislature had

conferred upon it.

The Legislature, then, having given to the Democratic

State Executive Committee the authority to fill in the

blank which it left in the statute as to the qualification

of voters at primaries, made the Democratic State Execu

tive Committee pro tanto its agency, and the old maxim

qui facit per alium facit per se is applicable.

It follows that the resolution of the Executive Commit

tee must be read as an integral part of the statute itself,

and when superimposed upon Chapter 67 of the Laws of

1927, this new section is identical with the old Article 3107

which was considered and condemned in Nixon v. Herndon.

Although the new Article 3107 makes no discrimina

tion against Negroes in so many words, this Court can

not accept the statute at its face value, but must go fur

ther and examine what has been accomplished behind and

by means of its bland exterior by the Democratic State

Executive Committee. In the words of Mr. Justice

Matthews in Yick 1 Vo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 373:

“ Though the law itself be fair on its face and

impartial in appearance, yet, if it is applied and

administered by public authority with an evil eye

and an unequal hand, so as practically to make

unjust and illegal discriminations between persons

in similar circumstances, material to their rights,

the denial of equal justice is still within the pro

hibition of the Constitution. This principle of

interpretation has been sanctioned by this court in

Henderson v. Mayor of New York, 92 U. S. 259;

21

Chy Lung v. Freeman, 92 U. S. 275; Ex parte Vir

ginia, 100 U. S. 339; Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S.

370; and Soon Hing v. Crowley, 113 U. S. 703.”

This Court has on other occasions rejected as uncon

stitutional statutes which sought to re-establish, the status

quo of the days before the adoption of the Fifteenth

Amendment by excluding Negro voters from the polls

through the medium of “grandfather clauses.”

Guinn v. United States, 238 U. S. 347.

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368.

The “ Inherent Power” Argument.

It is urged by the respondents and by the courts below

(R. 25, 30) that regardless of the statute there is inherent

power in the political party to prescribe the qualifications

of its own members and those entitled to vote at party

primary elections. It has been shown above that the

Democratic State Executive Committee intended to act

under the new Article 3107; but even if the Committee did

not intend to act under the statute it could not avoid

doing so. For assuming that such inherent power existed

before the Legislature of Texas manifested its intention

to take over the field of primary elections by enacting

legislation touching on every phase of the primary,

including the qualifications of voters, this power no

longer exists over the qualifications of voters at party

primaries.* It is sufficient that the Legislature has spoken

on this subject. It has invaded the field of the primary

and it must therefore be deemed to have assumed full con

trol of the situation.

The State being the supreme sovereignty, it must be

deemed to have superseded whatever sovereign powers

* This does not mean that for some purposes the Executive Committee

may not have inherent power still unaffected by the action of the Legis

lature; nor does it mean that if the Legislature had not acted with respect

to primaries, the parties would not have had jurisdiction over the com

position of the electorate at such primaries. These are matters that need

not now be questioned or decided.

22

political parties may previously have had with respect to

the control of primaries and party membership. Fruitful

analogy and ample support and authority are supplied by

the cases which have dealt with the relation of Congress

and the State Legislatures in connection with the Com

merce Clause and the State police powers.*

That the State has expressed itself in regard to pri

maries is evidenced by old Article 3107, considered in

Nixon v. Herndon, in which the Legislature specifically

provided the qualifications of voters at primary elections.

It also provided by Article 3110 of the Revised Civil

Statutes of 1925 a statutory pledge for voters, f

It is clear from the face of Chapter 67 of the Laws of

1927 that the Legislature did not relinquish its sovereignty

when it delegated its power to determine the qualifications

of voters at primaries to the party executive committees,

because (1) the new statute did not purport to withdraw

legislative sovereignty but merely to substitute a new pro

vision in place of the one declared unconstitutional, the

statute, to quote its own terms, being “ to repeal Article

3107 of Chapter 13 of the Revised Civil Statutes of Texas,

and substituting in its place a new article * * and

(2) the statute contains explicit limitations on the power

of the party executive committees forbidding them to deny

the right to participate in a primary “because of former

political views or affiliations or because of membership or

non membership in organizations other than the political

party.”

There is ample authority in the decisions of the Texas

courts to demonstrate that the Democratic Party in Texas

and its Executive Committee had ceased to have any in

*See article by Thomas Reed Powell, 12 Minn. Law Rev. 321, 470;

Lindgrcn v. United States, 281 U. S. 38, 46.

f “Art. 3110. Test on ballot. No official ballot for primary election

shall have on it any symbol or device or any printed matter, except a

uniform primary test, reading as follows: ‘I am a ........................ (inserting

name of political party or organization of which the voter is a member)

and pledge myself to support the nominee of this primary’ ; and any

ballot which shall not contain such printed test above the names of the

candidates thereon, shall be void and shall not be counted.”

See also Article 2955, qualifications for voters which are applicable to

primary elections. Texas Election Law pamphlet, p. 26.

2.2

herent power to prescribe qualifications of voters at Demo

cratic primary elections long before the resolution here in

question was adopted.*

In Briscoe v. Boyle, 286 S. W. 275 (Tex. Civ. App.,

1926), this very question was squarely presented and the

Court held that all inherent power in the premises ceased

to exist when the Legislature entered the field of primary

election regulation and enacted legislation concerning the

qualifications of voters at such elections.! In that case

a county Democratic executive committee adopted a reso

lution excluding from primary elections all who had voted

against any Democratic gubernatorial nominee in the pre

vious election. Fourteen such persons brought suit against

the judges of election to enjoin them from enforcing the

resolution. The injunction was denied in the lower court

but on appeal it was granted. The Texas Court of Civil

Appeals considered at length the legislative situation with

respect to primary elections and held that since the State

of Texas had legislated in detail concerning the qualifica

tions of voters at such elections, the political parties them

selves no longer had any power to prescribe qualifications

not made under authority of the statute. The Court said

at page 276:

“ Before the legislative department invaded the

province of party government, and assumed control

and regulation of party machinery, the right to say

who should and who should not participate in party

affairs was exercised by the party governments,

with which the courts would not concern them

selves.

But the Legislature has taken possession and con

trol of the machinery of the political parties of the

State, and, while it permits the parties to operate

that machinery, they do so only in somewhat strict

accordance with the rules and regulations laid down

in minute and cumbersome detail by the legislative

body. The statute designates the official positions

to be occupied in the parties, and, while it permits

the members of the parties to select such officials,

* And see 43 Harv. Law Rev. 467, 471; 39 Yale Law Journ. 423, 424.

t That case involved the old Article 3107 prior to its consideration by

this Court in Nixon v. Herndon.

21

they can do so only in the manner prescribed by the

statutes, which define the powers and duties of

those officials, beyond which they cannot lawfully

act. The statute prescribes the time, place, and

manner of holding primary elections. It prescribes

the forms of the ballots to be used, and the process

by which the election officials shall identify and

hand out the ballots and by which the voters shall

mark and deposit the ballots when voted. It pre

scribes the declaration to be made by the voter, and

the obligation to be assumed by him as a condition

precedent to the validity of his ballot. In fine, the

Legislature has in minute detail laid out the process

by which political parties shall operate the statute-

made machinery for making party nominations, and

has so hedged this machinery with statutory regu

lations and restrictions as to deprive the parties and

their managers of all discretion in the manipulation

of that machinery. * * *

I?y excluding negroes from participating in party

primary elections, and by legislating upon the sub

ject of the character and degree of party fealty re

quired of voters participating in such elections, the

Legislature has assumed control of that subject to

the exclusion of party action, thus depriving the

party of any power to alter, restrict or enlarge the

lest, of the right of the voter to participate in the

party primaries.’’ (Black type and italics ours.)*

The argument of “ inherent power” has been disposed

of by the Texas Courts in Lore v. Wilcox, l ib Tex. 256, 28

8. W. (2d) 515 (Texas, 1930), which involved the very

statute under consideration in this case. There the plaintiff

sought a mandamus to compel the Democratic State and

County Executive (Committees to place his name on a guber

natorial ballot of the Democratic primary and to desist

from enforcing a resolution passed in February, 1930,

by the Democratic State Executive Committee, which

precluded anyone from becoming a candidate at the Demo

cratic primaries if he had voted against the party in the

* The force of that decision was in no way diminished when this

Court invalidated the particular provision which excluded Negroes from

participating in primary elections. That was only one of many pro

visions regulating such elections and is clearly treated as such in Briscoe

v. Boyle. The principle o f the supreme sovereignty of the State over

primaries, as against that of the political parties, remains unimpaired.

1928 elections after having participated in the Democratic

primary of that year. The Executive Committee sought

to justify its action on the basis of its inherent power to

manage the affairs of the party and to determine who could

present his name for nomination at a primary. The Su

preme Court of Texas issued the mandamus, holding that

the Executive Committee had no inherent power to exceed

any of the limitations for which the Legislature had pro

vided in Article 3107. The Court no doubt had in mind

the possibility that its decision might be used as a basis

for attacking the Executive Committee resolution barring

Negroes from primary elections, and expressly stated that

it was not passing on that question. The Court guardedly

referred to Article 3107 as a “ recognition” by the Legisla

ture of the right of the Democratic Party to create an

Executive Committee and to confer on it various discre

tionary powers concerning the regulation of primary elec

tions. The Court pointed out, however, that the Legis

lature had limited the scope of this “ recognition” by the

proviso at the end of Article 3107 and construed this

proviso to apply to the exclusion of candidates for nomina

tion because of any form of past disloyalty to the party.

Here again inherent power is shown to have dissolved

upon the application of State sovereignty.*

The improper application of this power by the Legis

lature did not take it from the field of sovereignty and

restore the inherent power of the party Executive Com

mittee. If this had been so there would have been no such

“ emergency and an imperative public necessity” referred

to in Chapter 67 of the Laws of 1927. Only the lack of

inherent power to exclude Negroes could have created this

emergency, just as only the legislative intention to confer

a statutory power could have led the Legislature to meet

the emergency in the way it did.

Furthermore, the enactment of Chapter 67 of the Laws

of 1927 would automatically deprive the Democratic Ex

* The Briscoe case was cited as authoritative by the Supreme Court

in the Love case.

2 0

ecutive Committee of any inherent power to bar Negroes

from its primary elections if such inherent power had not

already been terminated by virtue of the prior enactment.

This is true whether, as we contend, the statute is a direct

delegation of authority to prescribe qualifications discrim

inating against Negroes or whether it be a mere general

authority to prescribe the qualifications of voters at pri

mary elections delegated by the Legislature.

Under Briscoe v. Boyle and Love v. Wilcox, supra, it

would have been impossible for the inherent power to

survive the creation of the statutory power. The two

powers could not exist side by side, and as between them

the one conferred by statute must prevail.

“ Recognition” of Power Argument.

This would be equally true if Article 3107 is regarded

as a “ recognition” by the Legislature of the existence of

power on the part of the Democratic Party to prescribe

through its Executive Committee that only white Demo

crats shall vote at its primary elections. It could not

reasonably be construed as a recognition of inherent power

because, as we have shown, it was a very plain recognition

to the contrary. But even if it had purported to be such

a recognition, it would have been a recognition of a non-

existing fact, it being clear that no inherent power could

have existed after the State sovereignty had taken over

the field. If such a recognition could have any effect at

all, it would have to be ms a recognition that the power

once had existed and as a declaration of a legislative in

tention that it should once again come into existence.

Whether this be regarded as the creation of a new power

or the recognition and restoration of an old one, the exist

ence of the power itself would be necessarily and wholly

dependent upon the force of the statute and hence would

be a statutory power, not an inherent one.

Moreover, there is no reason why a legislative “ recogni

tion” even of an existing inherent power should not turn

27

the inherent power into a statutory one. That is precisely

what was held in Briscoe v. Boyle, where the various statu

tory provisions as to how primary elections should l>e

conducted admittedly conferred powers on the Democratic

Party and its Executive Committee, which up to the time

of the legislative action the party and the committee had

enjoyed under their general inherent power to manage

their own affairs. There is no material difference in form

or substance between these statutory provisions (all but

one of which are still in force to-day) and the new Article

3107. If the latter can be regarded as a “ recognition” of

inherent power, then all the provisions must l>e regarded

as such; and this very recognition by the Legislature of

powers, whose existence and exercise had been a purely

private internal affair of the Democratic Party, would

itself supply the only expression of legislative intention

which is needed under the decisions in Brisco v. Boyle

to turn the private affair into a State affair and to trans

form the inherent power into a statutory power.

Other Texas authorities are to the same effect.*

The Texas cases, with one exception, all confirm our

contention that the party executive committees are

agencies of the State, subject to legislative control and

endowed with powers by the Legislature. The exception

to this rule is White v. Lubbock (Tex. Civ. App., 1930),

30 S. W. (2d) 72, which involved the right of a Negro

to vote in a primary, and where the Court held that the

party had inherent power to exclude Negroes. This would

indicate that only where a Negro is concerned do the usual

rules of construction and the common principles of sub

stantive law fall down. But even were the bulk of the

Texas cases not in accord with the view here urged, it

would be of no importance, because it was recognized

by this Court in the Home Telephone & Telegraph case

that the local conception of State action may differ from

the national conception of State action. In that case it

* Clancy V. Clough, 30 S. W . (2d) 569, which held that membership

on a City Democratic Executive Committee was itself subject to statutory

qualifications which could not be added to by the Committee; Love v.

Taylor, 8 S. W . (2d) 795; Friberg v. Scurry, 33 S. W . (2d) 762.

2S

was urged that because the municipal body which had

fixed the telejdione rates had exceeded its authority no

State action was involved. This Court refused to accept

that view, holding, on the contrary, that the action was

State action, the rates confiscatory and that the Fourteenth

Amendment applied “to every person whether natural or

juridical who is the repository of State power.” The em

phasis, therefore, was not upon whether power was prop

erly applied, but upon whether State power in fact existed.

So here the holding of the State Court that political par

ties have inherent power to exclude Negroes from primary

elections, and in so acting were not exercising state powers,

is not binding upon this Court.

In conclusion, we submit that the Executive Committee

had no inherent power to adopt the resolution which pro

vided that only white Democrats could vote in the primary

election. The only power which the committee could have

had, it received from the Legislature of the State. The

Legislature by the new Article 3107 intended the commit

tee to adopt such a resolution as was adopted and the

committee acted with this specific statute in mind. Under

the Texas authorities, no other action by the committee

would have been possible. The action of the committee,

therefore, and the action of the Legislature are equally

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

B. Even if the Democratic State Executive

Committee in adopting the resolution restricting

voting at Democratic primaries to “ white” Demo

crats exceeded the powers delegated to it by the

Legislature in Chapter 67, Laws o f 1927, its

action, though ultra vires, constituted State

action in violation o f the Fourteenth Am end

ment because it authorized and worked a classi

fication based on color.

Under the decisions of this Court in Home Tel. cC- Tel.

Co. v. Los Angeles, 227 U. S. 278, and the cases consistently

in accord therewith (Raymond v. Chicago Traction Co.,

207 U. S. 20; Fidelity d Deposit Co. v. Tafoya, 270 U. S.

426; cf. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356), it has become

definitely established that the limitations which the Four

teenth and Fifteenth Amendments impose upon State ac

tion apply not merely to the enactment of legislation by

State Legislatures but also, among other things, to action

taken pursuant to such statutes by those selected to act

thereunder. We may have a statute which is itself subject

to no constitutional objection, and which authorizes alto

gether proper action to be taken by designated persons on

behalf of the State. Yet, if these persons disobey the

statute and take action thereunder which, if taken by the

State, would be violative of the Fourteenth or Fifteenth

Amendment, their action is State action, permitting those

injured thereby to seek redress therefor by suit or action

in a Federal court. As this Court has said in Home Tel.

it- Teh Co. v. Los Angeles, supra (pp. 286-287) :

“ the provisions of the (Fourteenth) Amendment as

conclusively fixed by previous decisions are generic

in their terms, are addressed, of course, to the

states, but also to every person whether natural or

juridical who is the repository of state power. By

this construction the reach of the Amendment is

shown to be coextensive with any exercise by a

state of power, in whatever form exerted * * *

where an officer or other representative of the state

in the exercise of the authority with which he is

clothed misuses the power possessed to do a wrong

forbidden by the Amendment, inquiry concerning

whether the state has authorized the wrong is

irrelevant and the Federal judicial power is com

petent to afford redress for the wrong by dealing

with the officer and the result of his exertion of

power.” (Black type Ola's.)

In view of the considerations advanced under Toint II,

subdivision A, supra, it is clear, we submit, that the Demo

cratic State Executive Committee falls precisely within

the foregoing decision so far as concerns its action in

adopting the resolution limiting voting at the primary

election of July 28, 1928, to white Democrats. If its action

in adopting the resolution was not authorized by Article

30

3107, it necessarily was an abuse of the power to deter

mine the qualifications of voters at primary elections which

the committee possessed under that statute. It nevertheless

was action to which the reach of the Fourteenth Amend

ment extended, and being action which denied to Negroes

the equal protection of the laws, it was action which was

forbidden by that Amendment and which therefore was

void, because in the Home Telephone <& Telegraph case this