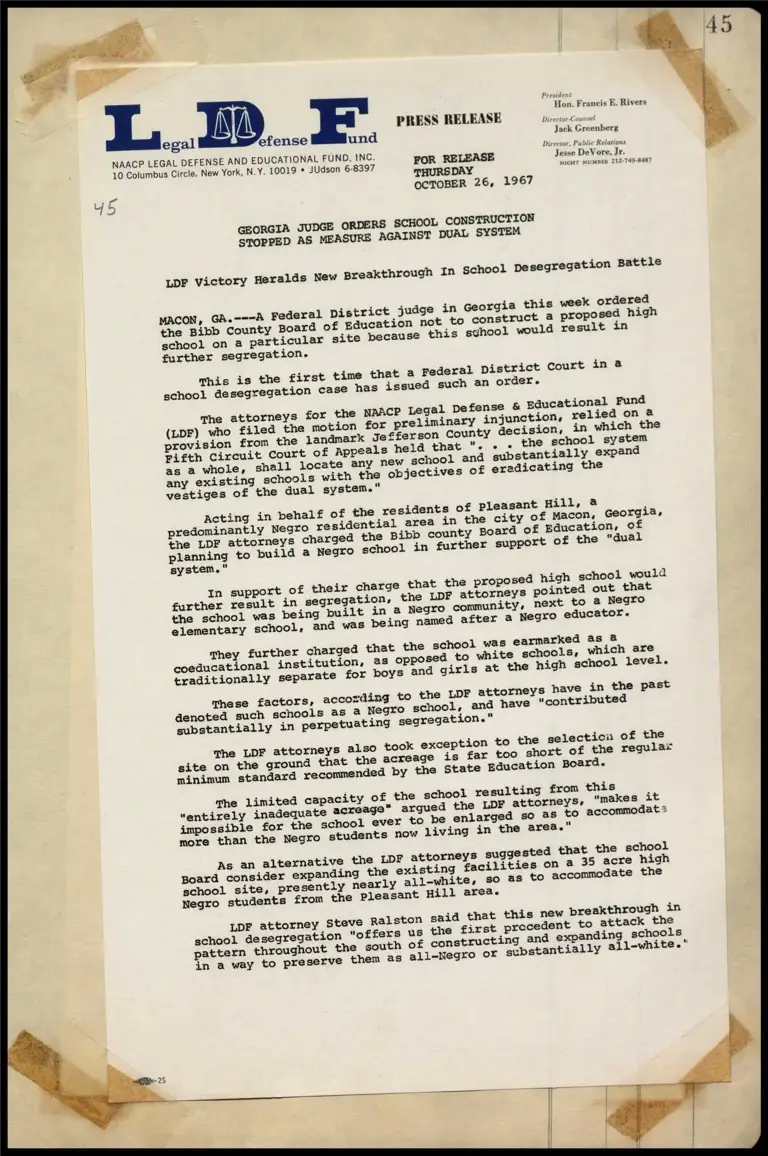

Georgia Judge Orders School Construction Stopped as Measure Against Dual System

Press Release

October 26, 1967

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 5. Georgia Judge Orders School Construction Stopped as Measure Against Dual System, 1967. 67055233-b892-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/df53f64a-5744-4f78-bace-2cf61c93303a/georgia-judge-orders-school-construction-stopped-as-measure-against-dual-system. Accessed February 02, 2026.

Copied!

5 Tid... EF.

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

10 Columbus Circle, New York, N.Y. 10019 * JUdson 6-8397

Gy

GEORGIA JUDGE ORDERS

STOPPED AS MEASURE AGAINST DUAL SYSTEM

LDF Victory Heralds

MACON, GA.---A Federal District

the Bibb County

further segregation.

This is the

The attorneys for the

(LDF) who filed the motion

as a whole,

any existing

vestiges of the dual system."

Acting in pehalf

residential

planning to build a Negro school in further support of the

of their charge

in segregation,

built in

In support

further result

the school was being

elementary school, and was

a

They further charged

coeducational institution,

traditionally separate for boys

These factors,

denoted such schools as 4 Negro

substantially in perpetuating segregation."

The LDF attorneys also took exception to the selection of the

that the acreage is

site on the ground

minimum standard recommended by

The Limited capacity of

“entirely inadequate acreage

impossible for the school ever to

more than the Negro students now

As an alternative the LDF attorneys suggested

Board consider expanding the existing

school site, pre sently

Negro students from the Pleasant Hill area.

LDF attorney Steve Ralston said that this

"offers us the

the south of constructing and expanding schools

to preserve them as all-Negro or substantially all-white." school desegregation

pattern throughout

in a way

New Breakthrough In School De

Board of Education not to

school on a particular site because this school would result in

first time that 4

school desegregation case has issued such an order.

NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund

for preliminary injunction,

provision from the landmark Jefferson County decision,

Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals held that "

shall locate any new school and substantially expand

schools with the objectives

of the residents of Pleasant Hill, a

the LDF attorneys pointed out that

being named after

that the school was earmarked as 4

as opposed to white

accozding to the

the school resulting from

" argued the LDF attorneys,

President

Hon. Francis E. Rivers

PRESS RELE! Director

Jack Gre: enberg

Director, Public Relations

Jesse DeVor

NIGHT NUMBER 212 FOR RELEASE 749-8487

THURSDAY

OCTOBER 26, 1967

SCHOOL CONSTRUCTION

segregation Battle

judge in Georgia this week ordered

construct a proposed high

Federal District Court in @

relied on a

in which the

the school system

of eradicating the

area in the city of Macon, Georgia,

Board of Education, of

"dual

that the proposed high school would

Negro community, next to a Negro

a Negro educator.

schools, which are

and girls at the high school level.

LDF attorneys have in the past

school, and have “contributed

far too short of the regular

the State Education Board.

this

"makes it

be enlarged so as to accommodat=

living in the area."

that the school

facilities on @ 35 acre high

so as to accommodate the

new breakthrough in

first precedent to attack the

“In the future" he continued, “we can force school Boards to

locate schools and to plan constructions and expansion so as to

integrate them and break down the identity of white and Negro

schools."

|

The LDF attorneys who handled the case were: Charles Stephen

Ralston and James Finney of New York city, and Thomas Jackson of

Macon, Georgia.

=30

NOTE: The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is

a separate and distinct organization from the NAACP, serving as the

legal arm of the entire civil rights movement and representing

members of all groups as well as unaffiliated individuals.