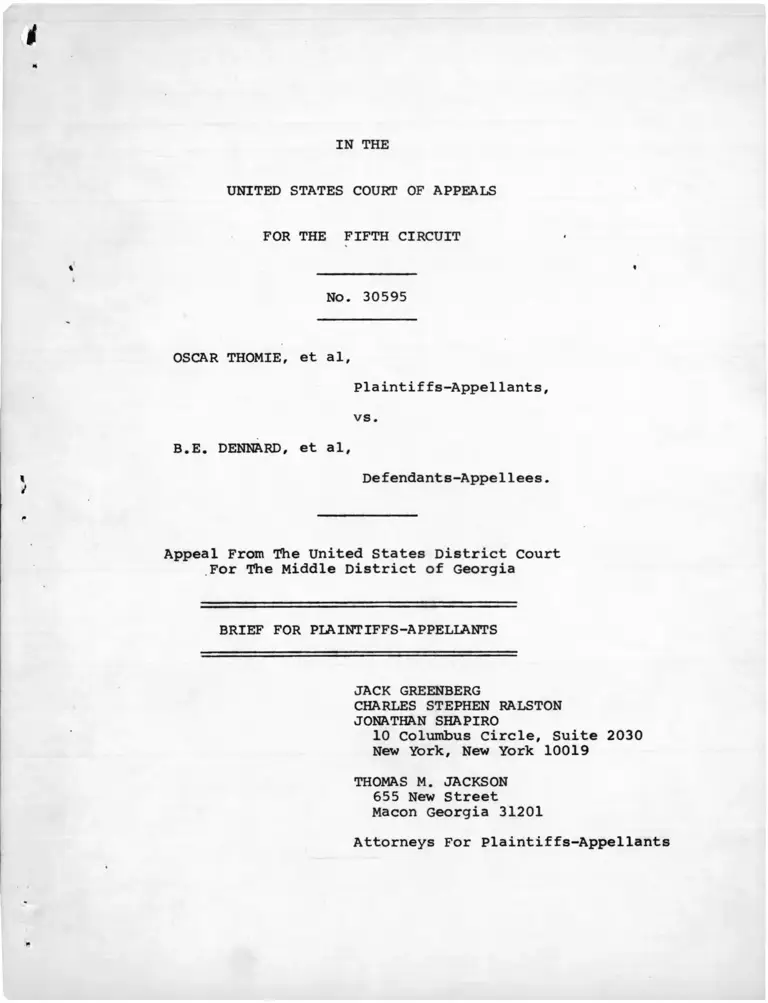

Thomie v. Dennard Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 17, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thomie v. Dennard Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1970. 9809a810-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/df6c68a6-5020-4416-b76d-8fb1207921af/thomie-v-dennard-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 30595

OSCAR THOMIE, et al.

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

B.E. DENNARD, et al,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District of Georgia

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

THOMAS M. JACKSON

655 New Street

Macon Georgia 31201

Attorneys For Plaintiffs-Appellants

Page

ISSUES PRESENTED ..................................... iii

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............................... 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS .................................. 5

ARGUMENT ............................................. 9

A. The Court Below Erred in Holding That

It was Barred From Issuing A Declaratory

Judgment Regarding The Constitutionality

Of The City Ordinance ................... 9

B. The Court Below Erred In Not Holding The

Perry Parade Ordinance Unconstitutional

On Its Face .............................. 12

C. The Court Below Erred in Not Enjoining

The Use Of Violence By Law Officers

Against Arrested Demonstrators ........... 17

CONCLUSION ........................................... 18

I N D E X

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE 19

Table of Cases

J\ A u , de>***$> r * j r w ' n o h ' t c . , £22s

t V ^ e i S ^ $*9H5fc 390.^.S 611 (1968), ............

Davis v. Francois, 395 F.2d 730 -----

(5th Cir. 1968) ....

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S 51 (1965)

. Guyot v. Pierce'- 372 F.2d 658 (5th cir. 1967)

t c> >o w

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S 496 (1938)

Kelly v. Page, 335 F.2d 114 (5th Cir. 1964)i/

LeFlore v. Robinson p 2d /cu-t, r>-

Nov. 12, 1970) ...7777. ---- (5th Clr*

LeFlorev. Robinson, slip op,

^Robinson v. Coopwood 292 F. Supp. 926

(N D. Miss. 1968), ajf^^-gtSt-FTaa li+f „ (5th Cir. 1969f.........

V'

«/

Sh1471®1969)h 7 : . ? ity ° f Birn,in9hai"" 394 U.S

Ware v. Nichols, 266 F. Supp 564 (N.D. Miss. 1967)

s m )iiT s»'!'w?llace- 24° f . supp. ioo(M.D. Ala. 1965) ............. _ _

y/ V° 1 V V ' 5 9

10

— »

>7 7 '/

10 " >' K »

12

10

18 3

17

b / 7iv/

— 10, 15,

^ 5

12

10

. / 1 r̂al L *^v -5<70 Cm.]; fa ^ ̂

Zwickler v. Koota, 387 U.S 241 (1967)

18

' V10

Statute

J 28 U.S.C. § 2283

'Tv U5c- $

<+U~h rj / <46 / i/ JT

5, 10,12

li

ISSUES PRESENTED

II.

III.

Whether the court below erred in holding that it

could not grant declaratory relief regarding the

constitutionality of a city parade ordinance

challenged on the ground it violated the First

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States?

Whether the parade ordinance of the City of Perry,

Georgia which contains no provision for judicial

review of denials of parade permits is unconstitu

tional on its face as violating the First Amendment?

Whether the court below erred in failing to make

firicli.ric}s of facts and failing to grant injunctive

relief when presented with evidence showing mis

treatment by law enforcement officers of arrested

demonstrators?

iii

TN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 30595

OSCAR THOMIE, et al,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

B.E. DENNARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District of Georgia

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an action commenced in the United States District

Court for the Middle District of Georgia seeking to challenge the

. , _ k* j- c-'-'constitutionality on its face and as applied of the-parade, ordin-/

U'l' \l */

ance^of Perry, Georgia^ a declaratory judgment was sought

*/ The full text of the Ordinance5 and of a i«oiifyin.j ^

amendment are as follows:

O-dhly )

that the ordinanc^/or^iairface and as applied violated freedom

of speech, assembly, and the right to petition for a redress of

grievances, as guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments

'■*/ (Continued)

PARADES AND PROCESSIONS

Sec. 13-1. SHORT TITLE --- This chapter shall hereafter

be known and may be cited as the "Parade Ordinance."

(Ord. of 5-9-63, § 1)

Sec» 13—2. DEFINITIONS -- (1) Parade and procession.

The terms "parade" and "procession" shall be synonymous

and interchangeable and shall consist of two or more

persons walking or riding on public streets and side

walks in the city for the purpose of display, or com

memoration.

(2) Participant. The term "participant" shall mean

and include any individual physically engaged in a parade

or procession and any other individual abetting same.

(3) Sponsor. The term "sponsor" shall mean and in

clude any person, firm, partnership, association, cor

poration, company, church, or organization of any kind.

(Ord. of 5-9-63, § 2)

Sec. 13-3. DECLARATION OF PURPOSE -- It shall be the

purpose of this chapter to provide continuing convenient

usage of the streets and sidewalks in the city, to the

general public in the pursuit of their lawful occupa

tions, activities, and travels, and in the furtherance

traffic safety to the citizens of the community.

(Ord. of 5-9-63, § 3)

Sec. 13-4. PARADE PERMITS -- REQUIRED --- It shall

be unlawful for any person to be a participant in any

parade not authorized by a parade permit issued by the

city clerk. (Ord. of 5-9-63, § 4)

Sec. 13-5. SAME -- PROCEDURE TO OBTAIN --- Each parade

shall have a sponsor who shall make written application

to the mayor and council, two weeks prior to date of

parade, requesting a parade permit. Such application

shall set forth the date contemplated; the time and

duration of same, the streets and sidewalks to be tra

versed, the kind and number of vehicles to be used,

if any, the approximate number of participants, the

-2-

/fe- 12

to the constitution (A. T®) (References are to Appellant's

Appendix (A); page citations are to the pagination found at the

top of each page). Injunctive relief was also requested

against the arrest and prosecution of persons for violating

the ordinance, and specifically against the prosecution of per

sons arrested on certain specified dates in the past# .

jV (Continued)

object and intent of the parade, and the individual interest

of the sponsor making the application.

(2) Such application shall be considered by the mayor

and council at a regular or special meeting and dependent

upon local exigency and in their discretion, the mayor and

city council may approve or disapprove same. if approved,

the city clerk shall issue the permit. if disapproved, the

city clerk shall remit deposit as required in Section 13-6. (Ord. of 5-9-63, § 5)

Sec. 13-6. SAME FEE The fee for a parade permit

shall be fifteen dollars and such amount shall be tendered

with the application. (Ord. of 5-9-63, § 5; Ord. of 6-1-65)

Cross reference --- Occupational license fees, § 11-13

Sec. 13-7. DURATION OF PARADE --- No parade shall exceed

thi^ty minutes in duration and the continuance of any parade

for a longer duration shall constitute a violation of this

Chapter. (Ord. of 5-9-63, § 6)

MINUTES: PERRY CITY COUNCIL, May 12, 1970

A motion by H.E. Smith, seconded by Dan Britton that the

Mayor be authorized to take applications for parade permit to

come up Spring Street and down Highway 41 at a minimum of

hour notice and to have discretion of issuing those per

mits as he sees fit until further notice for this purpose only.

The traffic control to control this situation will be left up

to the Chief of Police and Lt. Abernathy at their discretion.

The fifteen dollar fee will be collected for each occasion.

An injunction was also sought against any form of harassment or

intimidation of persons attempting to exercise their First

(7Amendment rights (A. 2&j

The action was commenced o n ' { ^ 4 ^ 1970, by the plain

tiffs as individuals and as representatives of the class of

black citizens who had in the past and who wished in the future

to exercise their First Amendment rights, but who had been arrestee

and threatened with prosecutions pursuant to the p m f e ordinance'^’

(A. 2-3). They wished to continue their constitutionally pro

tected activities but the pendency of prosecutions, the threat

of future arrests and prosecutions, and the use of violence by

police officials had the effect of discouraging them in so doing

so that the exercise of those rights had been deterred and chilled

N - h T(A. «=ae).

— A The defendants-appellees are officials of the city of

u . inrlnHinrr oh-iof of nnl iro ' rPerry, ftaorgjj, including the chief of police,' the

Chfiyi, i / u a/

•it+r attorney; M members of the pity, coun&trt; All o

-iv-C j

yor, the

members of the pityx couni

officials were responsib

ordinance*” Ct-v'Ji

lU ô cA j.

rs of the city/council- 7 1

le for the enforcement of 1

cruSLZ.„

Z.JJ, k

f thes<^

the challenged

1970, the district court held an eviden-

cV

inn Tnrr. trr-it1

-J— the hear; - < W i b u ^

trimr-ror— pr r -

USQ-—,

'7

5.3- r r ) .1 • ‘ trA* (A 4 ^ ̂/ (

Testimony was given (which is summarized bê Loy;) con- ,

c-7 CL̂£*̂yu,-fu*{ **< Trt. u / f 6 f CaM^ (tfj/

nts Briefly,cerning events

it dealt with demonstrations held by black citizens to protest

certain policies and actions by the city and the county board of

h£-c

cJ. J.

dtl ~ UA VU^V'^tvt

a. £o~f( sL " CnOyvdl UtUlt^, inu^cri^j L̂i\ cdh J k 0/ cn^'&ii (

education^ arrests made

of violence against arrested demonstrators.

On July 9, 1970, the district court handed down its

decision (A. 41>7 4-30). After reciting certain findings of

facts, the court held that it was barred from granting either

declaratory or injunctive relief. its conclusion was based on

the applicability of 28 U.S.C. § 2283, the federal anti-injunctic

statute, which it said barred enjoining pending state criminal

prosecutions. As a corollary, the court held that it could not

issue declaratory relief since that would have the effect also of

interfering with pending state prosecutions. Therefore, all 6 ^

or relief were denied without the court reaching the

Co-Â>-/Jc C 4 . 3 VO - S7 y 5“ J ,merits of the -hnllnngn tn tlm p m inli 111 iTI II 11 ITT' I III M IIM I 11 111 i ■ 11

grounds (A. 426-430).

The Court did not discuss the plaintiffs' request for a

declaration and injunction regarding the future enforcement of

the ordinance. Nor did it make any findings of facts concernino

or indeed discuss, the evidence dealing with police mistreatment

of demonstrators. f The court's order

on July 14, 1970

(A. •«•*•).

was entered

) and a timely notice of appeal was filed

Statement of Facts

The demonstrations giving rise to this case came out of

discontent among black citizens of Perry, Georgia, with acts and

omissions of local governing bodies. Primarily these involved

problems with the board of education. The demonstrations gave

b

/ T y r y ? & ** -te*

W. — *4. 'n ^urt.

Wh* Ob’#

rise to a number of arrests for parading without a permit in

violation of a city ordinance. Although testimony was given

concerning other problems in the community this statement of

facts will by and large be limited to the circumstances of the

demonstrations and arrests.

The Perry parade ordinance, set out in full in the margin

above, requires that two weeks before the proposed date of any

parade or procession (broadly defined as two or more persons

walking or riding in public streets and sidewalks for the purpose

of display or commemoration) an application for a permit must be

made to the mayor and council, accompanied with a $15.00 fee.

The application must set out the date, the time and diration of

the parade, the route, the number of participants, the object

and intent of the parade, and the interest of the sponsor making

the application. The application will be considered by the mayor

and council and they may approve or disapprove it "dependent upon

local exigency and in their discretion." No parade will last

more than thirty minutes. No provision is made for any judicial

review of a denial of a permit (A. 21-22).

In March, 1970, a white group marched to protest integra

tion of the schools. Both the fee and time period were waived

by the council (A. 420). Subsequently, black citizens asked for

and obtained a permit for a demonstration; on this occasion the

fee and time period were also waived (A. 420-421)

On May 4, 1970, however, an application by black citizens

for a demonstration later the same day was denied. on the next

-6-

day, May 5, another application was made for a demonstration to

be held on May 9, a Saturday. This was also denied by the

mayor and council, ostensibly because they believed the situation

in town was too "tense" (A. 220-221; 422). On May 9, black

citizens met in a building in Perry known as the Spring Street

Annex (A. 43). The group decided that despite the denial of

their application they would march to the Board of Education

offices (A. 49-50; 97-98). Before reaching their destination,

they were met by police officiers and placed under arrest for

marching without a permit (A.52). The people were crowded into

buses, and, according to the testimony of plaintiff Thomie, some

sort of chemical was sprayed into the bus he was in (A. 53-54; 147).

When the demonstrators were at the place of incarceration two of

the leaders were kicked and otherwise mistreated (A. 55-56).

The next day, Sunday, May 10, another group of black

citizens met at the annex to discuss the arrests of the day

before. They felt that the arrests were unjustified and decided

to try to march to the Board of Education by a different route to

protest. They were also stopped, arrested for parading without

a permit, and jailed (A. 164; 173-175; 189-190; 194-95). A

chemical was also sprayed on this group after they had been put

into a bus (A. 190). A similar occurrence took place on May 11

(A. 425).

On May 12, the city council met and adopted a resolution

giving the mayor discretion to permit marches along a specified

route on only four hours notice (A. 423). Subsequent to that,

-7-

a succession of parades and demonstrations were held without

incident (A. 423-424).

However, on Saturday June 6, another group was arrested

for parading without a permit at the courthouse. About forty

persons had resumed a meeting that had been interrupted by rain.

When the meeting was over, the whole group started out from the

courthouse to return to the Annex Square. They were stopped by

the police officers (after walking 15 or 20 feet) and placed

under arrest for parading without a permit (A. 352-355).

By agreement, a small number of persons were prosecuted

and convicted in state court for violating the parade ordinance.

The remainder of the cases were continued pending appeals and

disposition of the present action.

-8-

ARGUMENT

THE DECISION OF THE COURT BELOW CONFLICTS

WITH THE LAW OF THIS CIRCUIT AS ENUNCIATED

IN LeFORE V. ROBINSON

As shown by the statement of facts, this is another

in a continuing series of cases that raises the issue of the role

of the federal courts in ensuring that the rights peacably to

assemble, to petition for a redress of grievances, and to free

speech are not abridged. In this instance, lengthy discussion

is not required, since the case is governed in all significant

aspects by the recent decision of this court in LeFlore v.

Robinson, ______ F.2d ______ (5th Cir., Nov. 12, 1970).

In LeFlore, challenge was made to an ordinance of

Mobile, Alabama, that required a permit to be acquired before a

parade could be held. This Court disposed of a number of issues

which are present in this case, including:

(1) the power and duty of a federal court to issue a

declaratory judgment regarding a city ordinance pursuant to

which prosecutions are pending in state court; and

(2) the constitutionality of a parade ordinance that does

not provide for immediate court review of a denial of a permit.

A . The Court Below Erred in Holding That It Was

Barred From Issuing A Declaratory Judgment

Regarding The Constitutionality of the City

Ordinance

Although the decision of the court below began with

-9-

a statement of the facts as it saw them, the actual holding of

the court did not deal with the merits of this action. Rather,

it rested on the grounds that 28 U.S.C. § 2283 barred injunctive

relief against pending state prosecutions and that therefore

declaratory relief also could not be given. For these reasons,

all prayers for relief, declaratory and injunctive, were denied.

However, in LeFlore this Court specifically rejected

such an approach. Rather, it held that regardless of the ulti

mate resolution of the question of whether 42 U.S.C. § 1983 was

an exception to the anti-injunction statute, a federal court was

still required to examine challenged ordinances for constitutional

invalidity under the First Amendment, even when state prosecutions

are pending. LeFlore v. Robinson, slip op. pp. 11-14. This

holding was fully consistent with a long line of authority in

this Circuit, See, e.g., Davis v. Francois, 395 F.2d 730, 737,

n*13 (5th Cir. 1968); Ware v. Nichols. 266 F. Supp. 564 (N.D.

Miss. 1967); Guyot v. Pierce. 372 F.2d 658 (5th Cir. 1967).

The holding of this Court in both LeFlore and Davis

v. Francois were compelled by the decisions of the United States

Supreme Court in Zwickler v. Koota, 389 U.S. 241 (1967) and Cameron

Xi....Johnson, 390 U.S. 611 (1968). in both cases, the Supreme Court

made it clear that the question of granting a declaratory judgment

was to be considered before and wholly independently of whether a.,

injunction should or could be issued. Indeed, in Cameron, the

Court itself first decided the declaratory judgment question and

then declined to rule on whether 28 U.S.C. § 2283 was applicable

-10-

because of its decision on the first issue. Surely if 2283

barred any decision on the request for declaratory relief, as

the Court below held in the present case, the Supreme Court

would have so ruled and would not have decided the question of

whether the statute involved in Cameron was constitutional.

Thus, Cameron and LeFlore require reversal of the

decision below. in addition, however, there is an independent

reason why the court below erred in not reaching the merits of

the challenge to the constitutionality of the ordinance here

involved. The Complaint and proof herein clearly established

a continuing controversy over the validity of the ordinance.

Not only had the plaintiffs and members of their class demon

strated in the past and were arrested, but they desired to con

tinue their activities in the future (A. 17-18).

However, the past and threatened future enforcement of the

ordinance had and would have the effect of discouraging their

activities (A. 17-18; 162-163). Protection was sought

against not only the pending prosecutions, but against future

arrests for failures to comply with the challenged ordinance.

Thus, the plaintiffs clearly alleged, and proved,

a continuing controversy with city officials that could only

be resolved by a decision by the federal court as to whether the

parade ordinance was constitutional and had to be complied with.

Tbe resolution of this controversy would in no way involve or

require the enjoining of any pending state prosecutions and

-11-

hence 28 U.S.C. § 2283 was simply inapplicable to that aspect

of the case.

B. The Court Below Erred in not Holding The

Perry Parade Ordinance Unconstitutional

On Its Face

Since, under LeFlore, the Court below clearly erred

in not deciding the constitutionality of the parade ordinance of

Perry, Georgia (Sec. 13-1-13-7, Ordinances of Perry, Ga., see

above pp. 1 - 3 ), this Court could remand for an initial deter

mination by that court of the issue. However, plaintiffs-

appellants urge that it would be more appropriate for this Court

to decide the question now since it is squarely governed by the

decision in LeFlore.

In LeFlore, this Court held unconstitutional the

Mobile, Alabama, parade ordinance on a ground directly applicable,

viz., the absence in the ordinance of a provision "for prompt,

Commission-initiated judicial review" of a denial of a parade

permit (slip op. p. 35). Thus, the ordinance was invalid

under the rule of Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51 (1965), as

expanded in Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 394 U.S. 147(1969).

The Perry, Georgia, parade ordinance has precisely

the same infirmity. The procedures for acquiring a permit are

set out in Sec. 13-5 of the ordinance. They require that

persons seeking to hold a "parade" make written application to

the Mayor and council two weeks prior to the date of the

-12- i

parade. Certain information must be provided, including the

date, time and duration, the route, the approximate number of

participants, and "the object and intent of the parade, and

the individual interest of the sponsor making the application".

The application will be considered by the Mayor and council at

a regular or special meeting, and they may approve or disapprove

the application "dependent upon local exigency and in their

discretion". if the application is disapproved the city clerk

shall remit the fifteen dollar fee and that, as far as the

ordinance is concerned, is the end of the matter.

The vice of such a regulatory scheme, as explained

in LeFlore, is that the absence of any provision for judicial

review may in fact allow the exercise of an unbridled censorship

over the exercise of constitutional rights even when facially

adequate standards are set out in the statute. The Court

pointed out that this is particularly true when the definition

of "parade" is so sweeping so as to require advance notice to

the city of any march (slip op. pp. 35-36). The definition of

"parade and procession" in the Perry ordinance is at least as

** /

broad as that in the Mobile ordinance struck down in LeFlore"

t/ The subsequent amendment as to time will be discussed below.

1'll/ Compare: "The terms 'parade' and 'procession' shall be synony

mous and interchangeable and shall consist of two or more

persons walking or riding on public streets and sidewalks

in the city for the purpose of display, or commemoration"

Sec. 13-2, Perry City Ordinance;

W i t h 1parade' is any formal public procession, march, cere-

money, show, exhibition, pageant, or a group of persons or

vehicles containing persons moving onward in an orderly,

V

-13-

That these concerns are not merely theoretical is

amply demonstrated by the record in this case. The court below

made much of the fact that parade permits were given on a number

of occasions. But while it is commendable that First Amendment

rights were not totally denied in Perry, the issue in this case

is whether the ordinance led to denials in any instances. Thus,

on May 4, 1970, an application was made for a parade for later

that afternoon and was denied. No parade was held on that day

(A. 421 ). On May 5, another application was made for a

parade in the early afternoon of May 9. This was denied, but not

because of any of the specific standards of ordinance, e.g., con

venient usage of the streets, traffic safety, etc. Rather, it

was as the court below found because the Mayor and council decided

V

that a "tense" situation prevailed at that time (A. 422; 222).

Thus, the city departed from the standards of its own

ordinance and denied a permit because they, on the basis of facts

or information unchallengeable in any way, decided the town was

too tense. If the ordinance provided for an immediate judicial

review of this decision the plaintiffs would have been able to

**/(Continued)

ceremonious, or solemn procession, or any similar display in

or upon any street, park or other public place in the city."

Sec. 14-051, Mobile City Ord. (LeFlore v. Robinson, si.op.p.26)

A word should be said concerning the two-week advance notice

provision. This had become in effect inapplicable because

of a consistent policy of waiving it folloed by the Mayor and

council. Subsequently, on May 12, a resolution was passed

authorizing the Mayor to take applications on four hours

notice and to issue permits on his discretion alone.

-14-

challenge the decision, find out on what information it was based

and perhaps have it overturned in the four days between the denial

of the permit and the date they wished to march.

As it was, with no such avenue provided for in the

ordinance, on May 9 they were faced with either acquiescing in

the city's decision and giving up their First Amendment rights or

marching and subjecting themselves to criminal penalties. It

is precisely this dilemma that is impermissible under Freedman

and Shuttlesworth and that is the fundamental basis for the

decision in LeFlore.

Two other incidents may be briefly noted to show

the invalidity of the ordinance. On May 10, the day after the

incident described above, a group of persons attempted to march

to protest the arrests of the day before. Obviously, the

necessity for immediate expression of protest makes applicable

the language quoted in LeFlore (si. op. pp. 35-36) from Robinson

v. Coopwood, 292 F. Supp. 926, 934 (N.D. Miss. 1968), aff'd, 415

F .2d 1377 (5th Cir. 1969):

Advance notice is impossible where the demonstration

results from a spontaneous group desire, and, even

where there is sufficient time to give the requisite

notice, the requirement necessarily destroys the feeling

of security from official restraint and deters potential

marchers from participating.

On that day the demonstrators were arrested for parading without

a permit, as was another group demonstrating for the same reason

on May 11 (A, 164; 173-175; 425).

Finally, on a later occasion a group of demonstrater

-15-

held a meeting on the courthouse square. They were unmolested

during the meeting, but when the group (approximately 40 persons)

left at its conclusion 10 to 12 persons were arrested for parad

ing without a permit. Thus the police chief made an ad hoc,

and therefore unreviewable determination, that twelve people

leaving a peaceful meeting together was a parade. Again, the

necessity of the decisions in LeFlore and Robinson v, Coopwood is

vividly illustrated by this incident.

Thus, the direct applicability of LeFlore to the

Vpresent case is clear and the decision below must be reversed .

jk_/ Just as in LeFlore other provisions of the ordinance that

give rise to constitutional issues may be noted in passing

(See, si. op. p.28, n.13). Although the ordinance pur

ports to be concerned with traffic problems, by its terms

it gives a much broader grant of discretion to the city

council than does the Mobile ordinance. Thus Sec. 13-5

allows the council to grant or to deny permits "in their

discretion" and "dependent upon local exigency". That

this allows consideration of factors other than those set

out in the ordinance is, of course, illustrated by the

council's denial of the permit for the May 9 march because

it believed that the town was "tense".

Next, the two-week notice requirement is simply too

long to be justified. The fact that it was waived

regularly does not cure the problem, since waivers were

or were not given on the basis of no discernable standards

except the impermissible one of whether the council be

lieved it was wise in the particular case.

Finally, the May 12 resolution has the practical

effect of replacing the ordinance with a wholly different

scheme. It gives the Mayor alone ungoverned discretion

to allow or not allow parades on a specified route on

four-hours notice.

-16-

c. The Court Below Erred in Not Ernoining

The Use of Violence By Law Officers

Against Arrested Demonstrators

In yet another respect this case is strikingly

similar to LeFlore. In both, the issue of mistreatment of

demonstrators after arrest and during incarceration was raised

(see LeFlore, si. op. p. 41). In both, of course, the main

focus of the action was on the constitutionality, facially and

applied, of ordinances used against demonstrators. However,

violence by law enforcement officers after arrests, whether

such arrests be constitutionally valid or not, can have a power

ful deterrent effect on the free exercise of First Amendment rights.

The evidence in this case involved incidents that

occurred in connection with the May 9 arrests. Testimony, des

cribed more fully in the statement of facts above, was given

that arrested demonstrators were sprayed with a chemical after

they were placed in busses and that certain persons were mis

handled at the county prison farm. The district court, however,

made no findings of fact concerning these claims and issued no

injunctive relief against police violence.

No reasons were given for the court's failure to

deal with this issue, although it can be assumed that it believed

that since it could not interfere with pending criminal prosecu

tions, it also should do nothing regarding these other claims.

We believe that this was plainly error. Ever si

Kelly v. Page, 335 F.2d 114 (5th Cir. 1964) this Court has made

it clear that federal district courts have a responsibility to

-17-

protect persons against all forms of illegal interference with

V

the exercise of First Amendment rights . This includes pro

tection against unwarranted violence by law-enforcement officers.

See, Williams v. Wallace, 240 F. Supp. 100 (M.D. Ala. 1965).

Thus, in its order of remand, this Court should in

struct the district court to make findings concerning the alleged

mistreatment of demonstrators and to issue appropriate injunctive

relief if necessary.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons appellants pray that the

decision below be reversed with instructions to enter a declara

tory judgment that the Perry, Georgia, parade ordinance is un

constitutional and to issue such injunctive relief as may be

proper.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

THOMAS M. JACKSON

655 New Street

Macon, Georgia 31201

V' And indeed, in Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 (1938),

the Supreme Court also so held.

-18-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have served copies of the

attached Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellants and the Appellants'

Appendix on counsel for Appellees-Defendants by mailing the

same air-mail, postage prepaid to D.P. Hulbert, Esq. and Tom

W. Daniel, Esq., 912 Main Street, Perry, Georgia 31069.

i

Done this day of November, 1970.

C. i c . ' u , S [Isjhi

Attorney For Appellants-Plaintiffs.

-19-

f

r

4