Biggers v. Tennessee Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Tennessee

Public Court Documents

March 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Biggers v. Tennessee Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Tennessee, 1967. 8696b4d8-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/df8cb972-370e-4fce-9814-708d77db145c/biggers-v-tennessee-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-tennessee. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

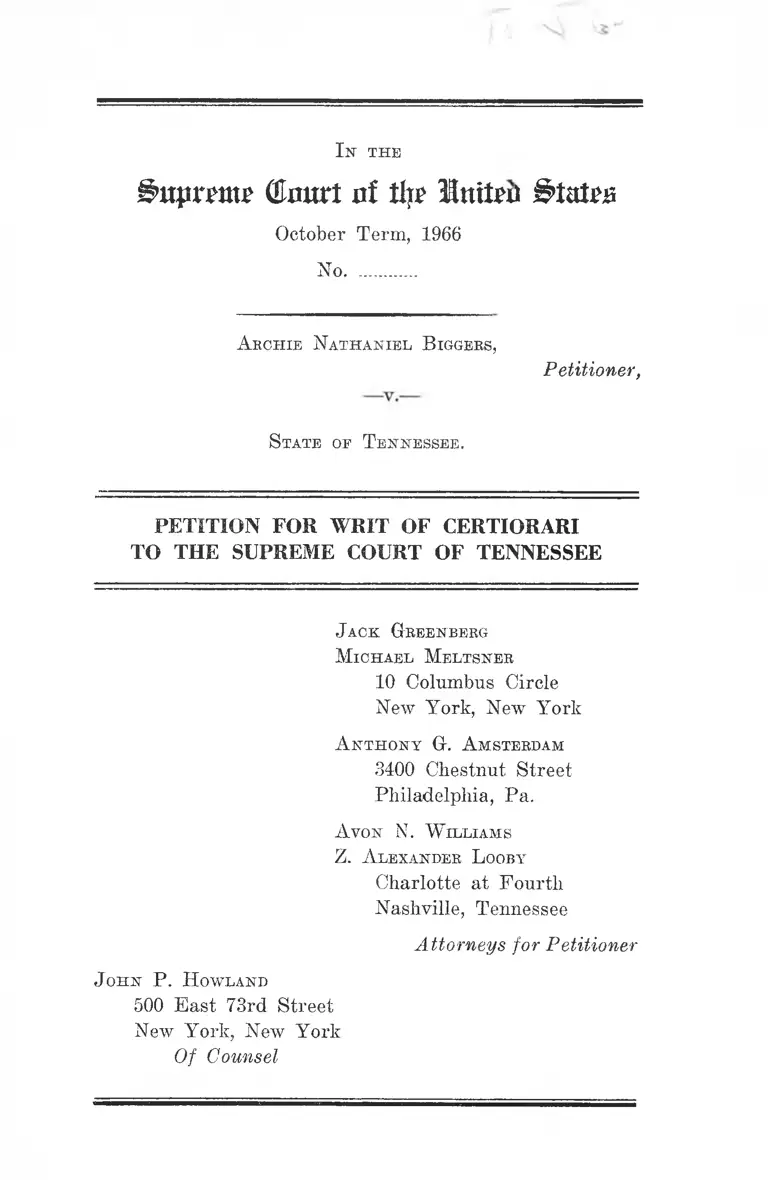

I n t h e

ir tjin w (flmtrt nf % InitTii States

October Term, 1966

No.............

A e c h ie N a t h a n ie l B iggees,

Petitioner,

S tate of T e n n e s s e e .

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE

J ack Greenberg

M ic h a e l M e l t sn e r

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

A n t h o n y G . A msterdam

3100 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

A von X. W illia m s

Z. A lexander L ooby

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioner

J o h n P. H owland

500 East 73rd Street

New York, New York

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinion Below ............... -......................... 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................... 1

Question Presented ......................... -............................ 2

Constitutional Provisions Involved ............................ 2

Statement .......................................................................... 2

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Below ............................................... 4

R easons fob Gba n tin g t h e W b i t :

I. Petitioner Was Denied His Rights Under the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment and the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to

the United States Constitution Under Circum

stances Similar to Those in Conflicting Court of

Appeals Cases Granted Certiorari and Presently

Pending Before This Court................................ 6

II. The Facts in This Case Show That Petitioner

Was Denied Due Process of Law and the Pro

tection of the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States ............. 8

C on clu sio n .....-......... -.............-................. -............................ -......... 14

A ppe n d ix

Opinion of Supreme Court of Tennessee ................... la

Denial of Rehearing ...............—............................ 6a

ii

T able of Cases

page

Carroll v. State, 212 Term. 464, 370 S.W.2d 523 ...... 4

DeLuna v. United States, 308 F.2d 140 (5th. Cir.

1962) ................... ..................... .................... ............. 12

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964) ................. 12

Holt v. United States, 218 U.S. 245 (1910) ................. 11

King v. State, 210 Tenn. 150, 357 S.W.2d 42 .............. 4

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) .......... ...... 11

Palmer v. Peyton, 359 F.2d 199 (4th Cir. 1966) ...... 13

Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757 (1966) .......... 11

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ........................ 8

Trustees of Monroe Avenue Church of Christ v. Per

kins, 334 U.S. 813 (1948) .......................................... 8

Wade v. United States, 358 F.2d 557 (5th Cir. 1966),

cert, granted 35 U.S.L. Week 3124 (Oct, 10, 1966) .... 7, 8

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U.S. 49 (1949) ........................ 11

United States ex rel. Stovall v. Denno, 355 F.2d 731

(2nd Cir. 1966) cert, granted 34 U.S.L. Week 3429

(June 20, 1966) ....................................... ................. 7} 8

S tatu tes I nvolved

28 U.S.C. §1257(3) ................. ....................................... 1

Tennessee Code Annotated, §39-3701 (1955) .............. 4

Ill

O t h e r A u t h o r it ie s

PAGE

Borehard, Convicting the Innocent (1932) ................ . 9

Frank, Not Guilty (1957) ..................... ..... ........... . 9

Gerber and Schroeder ed., Criminal Investigation and

Interrogation (1962) ....................... ........................... 9

2 Hawkins, Pleas of the Crown (8th ed. 1824) ........ 11

Jackson ed., Criminal Investigation (5th ed. 1962) ...... 9

8 Wigmore, Evidence (McNaughton rev, 1961) .......... 10

I n t h e

Crntrt at % Imtefc States

October Term, 1966

No.............

A r c h ie N a t h a n ie l B iggers,

—v.—

Petitioner,

S tate oe T e n n e s s e e .

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Tennessee entered

in the above entitled cause January 12, 1967, rehearing of

which was denied March 1, 1967.

Citation to Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Tennessee is

unreported and is printed in the appendix hereto, infra,

p. la. The opinion of the Supreme Court denying re

hearing is unreported and appears in the appendix hereto,

infra, p. 6a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Tennessee was

entered on January 12, 1967, infra, p. la. Rehearing

was denied March 1, 1967, infra, p. 6a. The jurisdiction

of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1257(3),

2

petitioner having asserted below and asserting here dep

rivation of rights secured by the Constitution of the United

States.

Question Presented

The petitioner, a 16 year-old Negro boy, was compelled

by the police, while alone in their custody at the police

station, to speak the words spoken by a rapist during the

offense almost eight months earlier for voice identification

by the prosecutrix.

Was the denial of petitioner’s right to personal dignity

and integrity by the police, and the failure to give him

benefit of counsel, provide him with a line-up, or with any

other means to assure an objective, impartial identification

of his voice by the prosecutrix a violation of petitioner’s

Fifth, Sixth and Fourteenth Amendment rights.

Constitutional Provisions Involved

This petition involves the Fifth, Sixth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

Early on the morning of August 17, 1965, Archie

Nathaniel Biggers, a Negro boy of 16 years, was arrested

by the police and allegedly identified by a woman as the

man who had attempted to rape her earlier that night

(Tr. 70). The story appeared on the first page of the

only morning newspaper in Nashville, The Nashville Ten

nessean, describing the defendant as “a burly 16 year-old

Negro youth.” Petitioner has never been tried on this

charge.

3

Later the same day the police went to the home of Mrs.

Margaret Beamer, the Negro prosecutrix, and requested

her to accompany them to the police station to “look at a

suspect” (Tr. 27-28, 57, 106, 109-110). Mrs. Beamer had

been raped on the night of January 22, 1965, almost eight

months earlier (Tr. 4-7, 20, 85-88). An intruder had en

tered her home and grabbed her in an unlit hallway

(Tr. 10). Hearing her mother’s screams, Mrs. Beamer’s

daughter ran into the hallway. She approached within

a foot of the rapist, whose face was turned toward her,

before being ordered by her mother to go back to her

bedroom (Tr. 129-132). The intruder then took Mrs.

Beamer to a patch of woods where he raped her (Tr. 4-7).

Neither Mrs. Beamer (Tr. 13) nor her daughter (Tr. 141)

could describe or identify the rapist. Although she once

identified a police photograph of a man as “having features”

like the rapist (Tr. 14a), Mrs. Beamer’s case lay dormant

for almost eight months for lack of clues.

When Mrs. Beamer saw Archie Biggers for the first time

he was being held at the police station in the custody

of five police officers (Tr. 112). Neither his parents nor rela

tives were present, nor had they been notified of the iden

tification (Tr. 103-104, 111, 155). He had no lawyer. The

police brought petitioner in Mrs. Beamer’s presence and

required him to repeat the words spoken by the rapist

at the time of the offense: “Shut up, or I ’ll kill you”

(Tr. 6, 7, 17, 47, 93, 108, 112-113, 156). From the sound

of these few words—the record does not reveal that the

petitioner said anything else (Tr. 17, 112-113)—spoken

eight months earlier during events which lasted from 15

to 30 minutes at most from the time that the prosecutrix

left her house until she returned (Tr. 30, 140-141), Mrs.

Beamer identified Archie Biggers as the man who had

raped her (Tr. 19). It was the same voice she was later

4

to describe at the trial as that of an “immature youth”

who “talked soft” in a “medium-pitched” voice (Tr. 17).

The identification of the petitioner by his voice, general

size, and skin and hair texture was the only evidence of

petitioner’s guilt1 (Tr. 17-19). Petitioner testified in his

behalf and emphatically denied committing the act charged

(Tr. 152, 154, 156). His stepfather, mother and seven

neighbors took the stand in his support as character

witnesses and testified to his excellent reputation for

truth, veracity, and good character (Tr. 185-186, 204-205,

210-212, 217-218, 224-226, 233-234, 242-245, 255-257).

On the basis of Mrs. Beamer’s identification evidence the

jury found Archie Biggers guilty of rape. He was sen

tenced to the State Vocational Training School for Boys

for twenty years (Tr. 292).

How the Federal Questions Were

Raised and Decided Below

The question of whether it was a violation of peti

tioner’s Fourteenth Amendment rights to compel him to

speak the words spoken by the rapist during the offense

for voice identification, without benefit of counsel or mini

mal procedural protections, was raised for the first time

in petitioner’s assignment of error and brief on appeal

to the Supreme Court of Tennessee filed November 7, 1966

(Ass. of Error and Br. 7, 14). Petitioner requested the

Supreme Court of Tennessee to waive its Rule 14(5),2

1 In Tennessee it is not mandatory that testimony of a violated female

be corroborated. Tennessee Code Annotated, §39-3701 (1955); Carroll v.

State, 212 Tenn. 464, 370 S.W.2d 523; King v. State, 210 Tenn. 150,

357 S.W.2d 42.

2 Rule 14(5) provides:

Motions for new trial and in arrest of judgment essential, when.—

Error in the admission or exclusion of testimony, in charging a jury,

5

and consider the question, although the error assigned

had not been made a basis for a motion for new trial.

The pertinent assignment of error was the following:

5. The conviction of the defendant solely on the basis

of an identification by prosecutrix predicated on his

being required to make statements reenacting the cir

cumstances of the offense while in custody without

benefit of counsel or warning of his right to have an

attorney with him and to remain silent, is unconsti

tutional and void as violating rights of defendant

secured by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States in that said

speech by defendant was, in effect, testimony against

himself involuntarily given by a juvenile under cir

cumstances so fundamentally unfair and oppressive

as to invalidate all evidence flowing therefrom under

said constitutional circumstances (Ass. of Error and

Br. 7-8, 14-16).

The Supreme Court of Tennessee waived Rule 14(5)

and decided the federal question raised by petitioner’s

assignment of error 5, renumbered 4 by the court, infra,

or refusing further instructions, misconduct of jurors, parties or

counsel, or other action occurring or committed on the trial of the

case, civil or criminal, or other grounds upon which a new trial is

sought, will not constitute a ground for reversal, and a new trial,

unless it affirmatively appears that the same was specifically stated

in the motion made for a new trial in the lower court, and decided

adversely to the plaintiff in error, but will be treated as waived, in

all eases in which motions for a new trial are permitted; nor will any

supposed matter in arrest of judgment be considered unless it appears

that the same was specifically stated in a motion, seasonably made

in the trial court, for that purpose, and held insufficient. This is a

court of appeals and errors, and its jurisdiction can only be exercised

upon questions and issues tried and adjudged by inferior courts,

the burden being upon the appellant, or plaintiff in error, to show

the adjudication, and the error therein, of which he complains.

6

pp. 4a, 5a. The court held that the voice identification test

had not violated petitioner’s constitutional rights against

self-incrimination because “the only thing he gave was

the sound of his voice to be used, along with other things,

solely for the purpose of identification” infra, p. 5a.

In his petition for rehearing to the Supreme Court of

Tennessee, petitioner renewed the allegations made in his

fifth assignment of error. The Supreme Court of Ten

nessee denied the petition, infra, p. 6a, on March 1, 1967.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Petitioner Was Denied His Rights Under the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and the

Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the United States Con

stitution Under Circumstances Similar to Those in Con

flicting Court of Appeals Cases Granted Certiorari and

Presently Pending Before This Court.

The facts in this case are starkly simple, but they raise

a critical question of the fairness and impartiality of

police identification practices. They reveal that Archie

Biggers was denied his right to a fair trial by police

practices which denied him elementary Fourteenth Amend

ment protections.

The only evidence against petitioner at trial was the

identification made by the prosecutrix, Mrs. Margaret

Beamer, that Archie Biggers was the man who had raped

her. Biggers, a 16 year old Negro was arrested early

on the morning of August 17, 1965 and charged with the

attempted rape of another woman (Tr. 70). Later the

same day, the police brought Mrs. Beamer, who had been

7

raped on the night of January 22, 1965, almost eight

months earlier (Tr. 4-7, 20, 85-88) to “look at a suspect”

(Tr. 27-28, 57, 106, 109-110). Unable to describe or identify

her assailant (Tr. 13) her case had remained without clues.

Asked to identify Biggers if she could, the first view she

had of the petitioner was of him alone in the custody

and presence of five police officers (Tr. 112). He had no

lawyer. The police then required him to speak the exact

words of the rapist spoken during the offense (Tr. 6, 7,

17, 47, 93, 108, 112-113, 156), on the basis of which she

identified petitioner as the rapist. These were the cir

cumstances surrounding the identification by the prosecu

trix.

The facts in this case raise the issue present in con

flicting Second and Fifth Circuit cases which this Court

has granted certiorari to determine. United States ex rel.

Stovall v. Denno, 355 F.2d 731 (2nd Cir. 1966), cert,

granted 34 U.S.L. Week 3429 (June 20, 1966); Wade v.

United States, 358 F.2d 557 (5th Cir. 1966), cert, granted

35 U.S.L. Week 3124 (Oct. 10, 1966). The Second Circuit,

sitting en banc, held that the defendant’s Fifth, Sixth and

Fourteenth Amendment rights were not violated when he

was taken to the victim’s hospital room for identification

without the benefit of a line-up or counsel, even though

arraignment had been postponed to allow him to obtain

counsel. The Fifth Circuit, in Wade v. United States,

supra, specifically adopted the view of the dissenting judges

in United States ex rel. Stovall v. Denno, supra. It ex

cluded testimony of the line-up on the ground that the

line-up had violated the defendant’s constitutional rights

because two witnesses had seen him in the custody of the

police shortly before the line-up, and defendant’s counsel

had not been notified and was not present at the line-up.

Archie Biggers, like Wade, was denied elemental protec

tions against suggestion and the right to counsel during

8

the test to identify his voice. Indeed, the circumstances

of Biggers’ identification were less conducive to impar

tiality than those in United States v. Wade, supra, and

the arguable necessity for speed in identification and

difficulty in arranging a line-up involved in United States

ex rel. Denno, supra, is not present in this case.

As the question presented in this case raises issues

similar to issues already pending before this Court, cer

tiorari is appropriate here. Compare Shelley v. Kraemer,

334 U.S. 1 (1948) with Trustees of Monroe Avenue Church

of Christ v. Perkins, 334 U.S. 813 (1948).

II.

The Facts in This Case Show That Petitioner Was

Denied Due Process of Law and the Protection of the

Fifth and Sixth Amendments to the Constitution of the

United States.

The voice identification of Archie Biggers was made in

a manner which could scarcely have been less conducive

to an impartial judgment. The sudden arrival of the

police to take her to “look at a suspect” (Tr. 27-28, 57,

106, 109-110) the first view of the petitioner in custody of

five policemen (Tr. 112) and the repetition of the rapist’s

words (Tr. 6, 7, 17, 47, 93, 108, 112-113, 156) merged to

create an atmosphere charged with suggestion that this

man was the rapist. Time, almost eight months, inevitably

dulls recollection, and increases the temptation to succumb

to suggestion.

The danger which is obvious and inherent in any iden

tification process involving sensory perception by a wit

ness is that extraneous factors may intervene to color and

prejudice what should be an objective decision. That sen-

9

sory perception, at very best, is not completely reliable

is clear from the documentation of supposedly “irrefutable”

identifications later proved incorrect. See Borchard, Con

victing the Innocent, p. xii (1932); Frank, Not Guilty,

p. 31 (1957).

To negate inference or suggestion from an identification

proceeding, a line-up is generally regarded as essential to

provide a mode of comparison by police authorities. See

Criminal Investigation and Interrogation, Gerber and

Scliroeder ed., §22.20 (1962); Criminal Investigation, Jack-

son ed. (5th ed. 1962) at pp. 41-42. The failure to provide

Archie Biggers with the protection of a line-up in a rape

case, considering his youth, the eight month period since

the rape and other circumstances is inexcusable. There

was no reason for the lack of a line-up, and every reason

to provide one. As Archie Biggers was being held in

police custody for an unrelated charge, this is not a case

of street identification immediately after arrest, nor even

a case where it was physically impossible to hold a line-up.

Nor was there need to identify Archie Biggers quickly.

Mrs. Beamer had been raped eight months earlier and

the time necessary to arrange a line-up certainly would

not have affected her identification. Indeed, the time lapse,

well known to the police, should have been sufficient to

mandate a line-up to police conscientiously seeking an im

partial, dispassionate identification.

Presented before Mrs. Beamer without a line-up, and in

the custody of five officers, Archie Biggers was required

to speak the words spoken by the rapist. He said nothing

else. Although this proceeding was supposedly held to

test the tone and timbre of petitioner’s voice, and upheld

by the Supreme Court of Tennessee on this basis, infra,

p. 5a, it would have been an extraordinary feat if the

prosecutrix could have ignored the particular words spoken

10

and concentrated solely on the sound of the voice making

them. Moreover, there was no reason to require the peti

tioner to speak the rapist’s words. Mrs. Beamer had not

indicated that the rapist spoke any word or combination

of words in a distinctive or unusual manner which would

aid identification. This fact was emphasized at trial when

she could only describe the voice as “medium-pitched,”

“immature” and “soft” (Tr. 17), The use of the rapist’s

words were an unwarranted suggestion that the speaker

was the rapist.

Identification, by whatever method, is similar to and has

much the same legal effect as self-incrimination. When, as

here, identification procedures cease to be objective because

the person being identified is required to do something

which improperly suggests that he and the offender are

the same person, the due process standard of fairness, in

cluding the right against self-incrimination, is violated.

The suggestion inherent in the use of the rapist’s words

is alone, and in combination with the total circumstances

of the case, a violation of due process.

The test of Biggers’ voice violated his Fifth Amendment

rights because he was compelled by the police to exercise

his will to speak. Requiring petitioner to make the posi

tive act of speaking and forming particular words vio

lated “the respect a government—state or federal—must

accord to the dignity and integrity of its citizens. To

maintain a ‘fair state-individual balance,’ to require the

government ‘to shoulder the entire load,’ 8 Wigmore, Evi

dence (McNaughton rev. 1961), 317, to respect the in

violability of the human personality, our accusatory sys

tem of criminal justice demands that the government seek

ing to punish an individual produce the evidence against

him by its own independent labors, rather than by the

cruel, simple expedient of compelling it from his own

mouth.” Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 460 (1966).

This is a restatement of this Court’s long-held view that

“the law will not suffer a prisoner to be made the deluded

instrument of his own conviction.” Justice Frankfurter in

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U.S. 49, 54 (1949), quoting from

2 Hawkins, Pleas of the Crown (46, §34) (8th ed. 1824).

This question is one of first instance before this Court.

In Holt v. United States, 218 U.S. 245 (1910), the leading-

case in this Court, Justice Holmes rejected the argument

that the Fifth Amendment was violated when the accused

was requested to model a blouse for identification. In

that case no exercise of the suspect’s will was required

since the blouse merely rested on his body, and might just

as well been held up against his body. Justice Holmes

appears to have recognized the Fifth Amendment’s pro

tection against the government overbearing an individual’s

will when he said, “[T]he prohibition of compelling a man

in a criminal court to be a witness against himself is a

prohibition against the use of physical or moral compul

sion to extort communications from him, not an exclusion

of his body as evidence when it may be material.” (218

U.S. at pp. 252-253) (emphasis supplied). It is obvious

that a person cannot be compelled to speak against his

will without “physical or moral compulsion.”

More recently, this Court held in Schmerber v. Cali

fornia, 384 U.S. 757 (1966) that a compulsory blood test

did not violate the Fifth Amendment. The court expressly

refused to adopt Professor Wigmore’s view that voice

identification does not violate the Fifth Amendment (foot

note 7, 384 U.S. at 763), and all past applications of the

distinction that the Fifth Amendment bars “testimony”

but not compulsion making the suspect a source of “real

or physical evidence” (384 U.S. at 764). The Wigmore

view that the Fifth Amendment bars only testimonial dis-

12

closures, 8 Wigmore, Evidence, §2263 (McNaughton rev.

1961), has been strongly challenged. Judge Wisdom, in

DeLuna v. United States, 308 F.2d 140, 145 (5th Cir. 1962),

said, “Professor Wigmore was consistently unfriendly to

the [Fifth Amendment] privilege, especially to its recog

nition when there was no direct coercion by the govern

ment and when there was no formal charge to which the

unanswered questions relate; his writings are an inex

haustible quarry of quotations for use against the policy

of the privilege.”

The true scope of the Fifth Amendment protects against

governmental overbearing of a person’s will. An individual

has the right to be protected from coercion designed to

make him do something controlled only by his will, which

is the heart of a person’s being and the source of his

individuality. To invade this sanctuary is to destroy the

well-spring of his integrity and dignity as a human being.

These are values that the Fifth Amendment seeks to shield

from governmental intrusion by “physical or moral com

pulsion.”

Archie Biggers was also denied his right to assistance

of counsel at the time of his identification, clearly a “critical

stage” in his case. Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478, 486

(1964). The police were without a clue to the identity of the

man who had raped Mrs. Beamer. If she could identify a

m an it would certainly form at least the basis for prosecu

tion. If counsel had been present he could have done several

things to insure an impartial test. He could have requested

a line-up, or alternatively some other plan to assure con

ditions designed to avoid suggestion. If present, counsel

could have questioned the prosecutrix during identification

before she had placed herself in the position of making a

positive identification. It is quite possible that his mere

presence would have served to counterbalance that of the

13

police, and the inherent suggestiveness of police station

identification of one in custody. Had counsel been present

he might have prevented the police from requiring the

petitioner to speak the words of the rapist, words which

carried an inherent suggestion of guilt. Or counsel might

have advised his client to remain silent.

The circumstances of this case, taken separately and in

combination, establish violations of the due process clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment, and through it, violations

of the Fifth and Sixth Amendments. An instructive decision

is Palmer v. Peyton, 359 F.2d 199 (4th Cir. 1966), where

the Fourth Circuit, sitting en lane, held without dissent

that a voice identification test without a line-up, in addi

tion to police failure to eliminate suggestions of guilt

before the test, violated due process. We believe the prin

ciple set forth by Judge Sobeloff in that case is equally

applicable here:

“In their understandable zeal to secure an identifica

tion, the police simply destroyed the possibility of an

objective, impartial judgment by the prosecutrix as

to whether Palmer’s voice was in fact that of the man

who had attacked her. Such procedure fails to meet

‘those canons of decency and fairness’ established as

part of the fundamental law of the land” (359 F.2d

at p. 202).

14

CONCLUSION

W h e r e fo r e , p e t i t io n e r p r a y s t h a t th e p e t i t io n f o r w r i t

o f c e r t io r a r i be g r a n te d a n d th e ju d g m e n t b e lo w re v e rs e d .

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

M ic h a e l M e l t sn e r

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

A von N. W illia m s

Z. A lexander L ooby

Charlotte at Fourth

Nashville, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioner

J o h n P. H owland

500 East 73rd Street

New York, New York

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Opinion of the Supreme Court of Tennessee

(January 12, 1967)

DAVIDSON CRIMINAL

A b c h ie N a t h a n ie l B iggebs,

vs.

Plaintiff in Error,

T h e S tate oe T e n n e s s e e ,

Defendant in Error.

Plaintiff in error, Archie Nathaniel Biggers, herein re

ferred to as defendant, appeals from a conviction of rape

for which he has been sentenced to serve twenty years (20)

years in the State Vocational Training School for Boys.

Defendant at the time of the crime was sixteen years old.

The victim, Mrs. Margaret B earner, is a married woman

with five children. On the night of 22 January 1965 she

was at home in her living room sewing. About 9 :00 p.m.

she started from her living room to the bed room, which

rooms are separated by a hall, and as she reached the hall

defendant, with a butcher knife in his hand, grabbed her

from behind pulling her to the floor. Her screams brought

her daughter out of a bedroom into the hall and when

the daughter saw what was happening she also began to

scream. Defendant said to Mrs. Beamer, “You tell her to

shut up or I ’ll kill you both.” Mrs. Beamer ordered the

daughter back into the bedroom. Defendant escorted Mrs.

Beamer out the back door of the house to a spot about

two blocks away where he had sexual relations with her.

Upon completion of the sexual act defendant ran away

and Mrs. Beamer, returning home, notified police. About

10:15 p.m. on this night Mrs. Beamer was medically ex

amined which revealed she had had sexual intercourse

within three (3) hours prior to that time.

During the early hours of 17 August 1965 defendant

was arrested for an incident occurring on this night of

his arrest and immediately taken to Juvenile Aid. Defen

dant’s mother came to Juvenile Aid and in her presence

he was fully advised of his constitutional rights. Later

on in the morning defendant was released to the Police

Department and Mrs. Beamer, at Police Headquarters,

identified defendant as the person who raped her on 22

January 1965.

Defendant as a witness in his own behalf denied any

knowledge of the crime. Several witnesses testified to his

good character.

The assignments of error are as follows:

1. The evidence preponderates against the verdict of the

jury and in favor of the innocence of the accused.

2. The defendant was prejudiced when a witness for

the State mentioned other offenses allegedly com

mitted by the defendant for which he was not on

trial and for which he had not previously been con

victed.

3. The defendant was prejudiced when the Attorney

General went outside the evidence in the case while

making his final argument to the jury.

4. The defendant was required to give evidence against

himself without having been advised of his consti

tutional rights.

5. The defendant was prejudiced by the action of the

Trial Court in refusing to require the State to furnish

him a transcript of the trial proceedings.

3a

The first assignment of error is predicated upon the

ground the identity of defendant by the victim was so

vague, uncertain and unsatisfactory and given under such

circumstances as not to have any substantial probative

value. This identification was made based upon the de

fendant’s size, voice, skin texture and hair. On identifica

tion the trial judge asked the victim, “All right. Is there

any doubt in your mind.” To which the victim replied,

“No, there’s no doubt.” Identification is a question of fact

for the jury. Stubbs v. State, 216 Tenn. —— , 393 SW2d

150 (1965). The first assignment of error is overruled.

Under the second assignment of error it is alleged

Thomas E. Cathey a member of the Metropolitan Police

Department, as a witness for the State, mentioned other

offenses allegedly committed by defendant. In defendant’s

brief these references to other crimes are described as

being “by inference.” We have carefully examined the

pages of the transcript cited and find no reference to other

crimes. The assignment of error is overruled.

Objection is made, under the third assignment of error,

to the following argument by the Assistant District Attor

ney General:

“In many parts of our United States, Gentlemen of

the Jury, a case of this nature would never go to

trial, and I am sorry to say, its all south of the State

of Tennessee, and that is because of this fine woman,

Mrs. Beamer’s environment, economic circumstances,

and situation, she is not considered in those states to

have any more rights than a dog and her reproductive

organs—

The argument above was not completed due to objection

by defendant which was sustained by the court. The As

sistant District Attorney General did not pursue this line

of argument further. Both the defendant and the victim

4a

were members of the Negro race a fact, of course, known

to the jury. It is insisted, under these circumstances, this

argument was an appeal to racial prejudice. We agree

this line of argument was improper, but in light of the

prompt action of the trial judge we think such was harm

less error. The third assignment of error is overruled.

Mrs. Beamer and defendant, for the purpose of possible

identification, were brought together at Police Head

quarters. Mrs. Beamer requested police have defendant

repeat in her presence some of the words her assailant

had used at the time of the rape. The words requested

were, “Stop or I ’ll kill you.” Defendant, upon instructions

of police, repeated these words and Mrs. Beamer bases

her identification of defendant as her assailant partly

upon his voice. Under the fourth assignment of error it

is alleged requiring defendant to speak these words for

the purpose of identification violated his constitutional

right against self-incrimination.

While the exact problem presented here has not been

before this Court, yet we think it is controlled by the logic

and reason used by the court in the case of Barrett v.

State, 190 Term. 366, 229 SW2d 516 (1950). The Barrett

case involved a defendant required to wear a hat at the

time he was being identified. This court, rejecting the

argument such was a violation of defendant’s privilege

against self-incrimination, quoted from Wigmore on Evi

dence, 3 Ed., Section 2265, p. 375 as follows:

“Unless some attempt is made to secure a communica

tion, written or oral, upon which reliance is to be

placed as involving his consciousness of the facts

and the operations of his mind in expressing it, de

mand made upon him is not a testimonial one.” 190

Tenn. 372.

5a

A thorough analysis of the problem presented can be

found in 8 Wigmore on Evidence, sec. 2265, at pp. 386, 396

(McNaughton, rev. 1961). In analyzing this constitutional

privilege Dean Wigmore lists eleven (11) principal cate

gories which he specifically states are not covered. Cate

gory No. 7 is : “Requiring a suspect to speak for identifica

tion.” A number of cases are cited for the proposition

a defendant’s rights are not violated when he is forced to

speak certain words solely for the purpose of identification.

See above citation in Wigmore.

In the instant case defendant was told what words to

say and in repeating them he did not give any factual

information tending to connect him with the crime; nor

could any reliance be placed on these words which would

indicate defendant was conscious of, or had knowledge of,

any facts of the crime. The only thing he gave was the

sound of his voice to be used, along with other things,

solely for the purpose of identification. Under these cir

cumstances we do not think defendant’s constitutional right

against self-incrimination was violated. The fourth as

signment of error is overruled.

Under T.C.A. 40-2037 et seq. the State is required to

furnish to an indigent defendant a transcript upon request.

The trial judge determines if the defendant is indigent

and in this case determined defendant was not indigent.

We find no error in this determination by the trial judge.

The fifth assignment of error is overruled.

Judgment affirmed.

6a

Denial of Rehearing by Supreme

Court of Tennessee

(March 1, 1967)

DAVIDSON CRIMINAL

A r c h ie N a t h a n ie l B iggers,

vs.

Plaintiff in Error,

T h e S tate of T e n n e s s e e ,

Defendant in Error.

P e t it io n to R eh ea r

Plaintiff in error has filed a petition to rehear as result

of our original opinion filed 12 January 1967. Rule 32 of

this court, inter alia, states:

A rehearing will be refused where no new argument

is made, and no new authority adduced, and no mate

rial fact is pointed out as overlooked.

Under this rule this petition to rehear is denied.

Ross W. Dyer, J.

Burnett, C J; Chattin & Creson, J J ;

Harbison, S J ;

Concur

MEIIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. 219