McKennon v. Nashville Banner Publishing Co. Respondent's Brief in Opposition

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1994

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McKennon v. Nashville Banner Publishing Co. Respondent's Brief in Opposition, 1994. 157b98a2-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/df95cb5d-f0c2-4fce-95ce-b5b97f494f46/mckennon-v-nashville-banner-publishing-co-respondents-brief-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

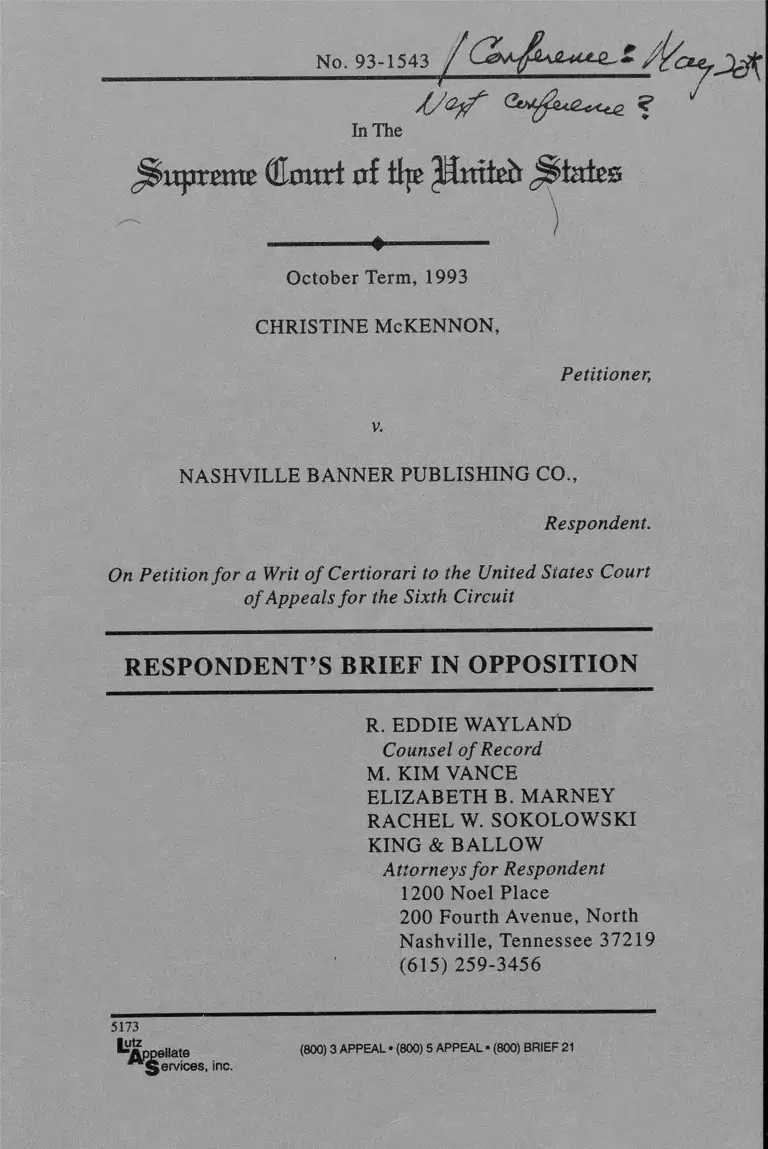

No. 93-1543

In The

Ji^uprttm (Court of tlje ptmiefr Jltates

October Term, 1993

CHRISTINE McKENNON,

Petitioner,

v.

NASHVILLE BANNER PUBLISHING CO.,

Respondent.

On Petition fo r a Writ o f Certiorari to the United States Court

o f Appeals fo r the Sixth Circuit

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

R. EDDIE WAYLAND

Counsel o f Record

M. KIM VANCE

ELIZABETH B. MARNEY

RACHEL W. SOKOLOWSKI

KING & BALLOW

Attorneys fo r Respondent

1200 Noel Place

200 Fourth Avenue, North

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

(615)259-3456

5173

lutz

■“Appellate

” §ervices, inc.

(800) 3 APPEAL • (800) 5 APPEAL • (800) BRIEF 21

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the courts properly denied Petitioner any remedy

based on her admittedly serious misconduct, her concession that

the doctrine of after-acquired evidence of wrongdoing applies to

the facts of her case, and her inability to show any pretext.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Question Presented ............................. ................................ i

Table of Contents .................................. ii

Table of Citations ........................................................... iii

Statement of the C a s e .......................................................... 1

A. The Proceedings B elo w ......................................... 1

B. Counter Statement of the Facts ............................. 3

Summary of A rgum ent........................................................ 7

Reasons for Denying the Writ ........................................... 8

I. RELIEF WAS PROPERLY DENIED TO

PETITIONER BECAUSE PETITIONER

ADMITS BOTH SERIOUS WRONGDOING

AND THE APPLICABILITY OF THE

DOCTRINE.............................................................. 8

A. All Circuits That Have Considered The

Doctrine Have Adopted It........................... 9

B. The Doctrine Fully Applies To The

Undisputed Facts Of This Case........... 11

C. The Facts Of This Case Would Entitle

Petitioner To No Relief. .................................. 13

II

Page

Ill

Contents

Page

II. SUMMARY JUDGMENT WAS PROPER

BECAUSE PETITIONER SHOWED NO

PRETEXT. ....................... 18

III. PETITIONER RELIES ON INAPPLICABLE

LAW AND POLICY............................. 21

Conclusion ............................................. 22

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases Cited:

ABF Freight System, Inc. v. NLRB, 114 S. Ct. 835 (1994)

........ ............................ .......................................... . . .1 5 ,1 6 ,1 7

Agborv. Mountain Fuel Supply Co., 810 F. Supp. 1247 (D.

Utah 1993) ......................... ...................... ...................... 10

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., A ll U.S. 242 (1986) . . . . 19,20

Benson v. Quanex Corp., 58 Fair Empl. Prac. Cases (BNA)

743 (E.D. Mich. 1992) ............................. ...................... 10

Bonger v. American Water Works, 789 F. Supp. 1102 (D.

Colo. 1992) ............ ....................................................... 10

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, A ll U.S. 317 (1986) . . . . . . . . . . 19

Churchman v. Pinkerton’s, Inc., 756 F. Supp. 515 (D. Kan.

1991) ......................................... .......................... 10

IV

DeVoe v. Medi-dyn, Inc., 782 F. Supp. 546 (D. Kan. 1992)

.................................................................................................. 10

Dotson v. United States Postal Service, 977 F.2d 976 (6th

Cir. 1992), cert, denied, 113 S. Ct. 263 (1992) ............. 9

Faulkner v. Super Valu Stores, Inc., 3 F.3d 1419 (10th Cir.

1993) .............................................................................. 9

George v. Meyers, No. 91-2308-0,1992 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

6419 (D. Kan. April 24,1992) ........................................ 10

Johnson v. Honeywell Info. Sys., Inc., 955 F.2d 409 (6th Cir.

1992)................ .................................................................. 3,9,10

Kristufek v. Hussmann Food Service Co., 985 F.2d 364 (7th

Cir. 1993) ................................................................... 9,11,13,14

Landgrafv. USI Film Prods., 1994 U.S. LEXIS 3292 (April

26,1994) ........................................................................ 21

Malone v. Signalj Processing Technologies, Inc., 826 F.

Supp. 370 (D. Colo. 1993)............................................. 10

Massey v. Trump’s Castle Hotel & Casino, 828 F. Supp. 314

(D.N.J. 1993).................................................................. 10

Mathis v. Boeing Military Airplane Co., 719 F. Supp. 991

(D. Kan. 1989)...................................... 10

Mitushita Electrical Industrial Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp.,

475 U.S. 574 (1986) ............ 18,19,20

Contents

Page

V

Contents

Page

Milligan-Jensen v. Michigan Technological Univ., 975

F.2d 302 (6th Cir. 1992), cert, granted, 113 S. Ct. 2991,

cert, dismissed, 114 S.Ct. 22(1993) ........ .. .3 ,9,17,18,21

Moodie v. Federal Reserve Bank, 831 F. Supp. 333 (S.D.

N.Y.1993) ................... ................................................ .. 10

O ’Day v. McDonnell Douglas Helicopter Co., 784 F. Supp.

1466 (D. Ariz. 1992), appeal docketed, No. 92-15625

(9thCir. 1992) .......... ............................ 10

O ’Driscoll v. Hercules, Inc., 12 F.3d 176 (10th Cir. 1994)

Pagliov. Chagrin Valley Hunt Club Corp., 1992U.S.App.

Lexis 15,399 (6th Cir. June 2 5 ,1 9 9 2 )........ ................ .. 9

Punahele v. United Air Lines, Inc., 756 F. Supp. 487 (D.

Colo. 1991) ............ ...................................................... 10

Redd v. Fisher Controls, 814 F. Supp. 547 (W.D. Tex. 1992)

Reed v. AMAX Coal Co., 971 F.2d 1295 (7th Cir. 1992)

................................. ................ ...................................... 9,14,15

Rich v. Westland Printers, 62 Fair Empl. Prac. Cases

(BNA)379(D.Md. 1993) ................................... .. 10

Russell v. Microdyne Corp., 830 F. Supp. 305 (E.D. Va.

1993) .......................... ........................ .. 10

Vi

Contents

Smith v. General Scanning, Inc., 876 F.2d 1315 (7th Cir.

1989) ............................................................................... 9

St. Mary’s Honor Ctr. v. Hicks, 113 S. Ct. 2742 (1993) . .18,19,20

Summers v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 864 F.2d 700

(10th Cir. 1988) ...................................3,9,13,14,21,22

Page

Sweeney v. U-Haul Co. o f Chicago, 55 Fair Empl. Prac.

Cases (BNA) 1257 (N.D. 111. 1991)............................... 10

Trentham v. K-Mart Corp., 806 F. Supp. 692 (E.D. Tenn.

1991) .................... 2

Wallace v. Dunn Constr. Co., Inc., 968 F.2d 1174 (11th Cir.

1992) ...................................................................9,11,14,15,21

Washington v. Lake County, III., 969 F.2d 250 (7th Cir.

1992) ..................................................... 9,10,11,14

Statutes Cited:

29U.S.C. § 6 2 1 ........................................................... 2

Tenn. CodeAnn. §4-21-101............................................... 2

Section 107 of the Civil Rights Act of 1991 21,22

vu

Contents

Page

Other Authority Cited:

Policy Guidance on Recent Developments in Disparate

Treatment Theory, N-915.063, EEOC Compl, Man.

(BNA)N:2119 ..................................... .......................... 22

1

No. 93-1543

In The

JSupmne (ttouri erf t\\t plmtefr

— ♦ .......— ------------

October Term, 1993

CHRISTINE McKENNON,

Petitioner,

v.

NASHVILLE BANNER PUBLISHING CO.,

Respondent.

On Petition for a Writ o f Certiorari to the United States Court o f

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

RESPONDENT’S BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. The Proceedings Below

On May 6, 1991, Petitioner filed this lawsuit in the United

States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee alleging

that her discharge from employment with Respondent the

2

Nashville Banner Publishing Co. (“the Banner”)1 violated the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act (“ADEA”), 29 U.S.C. § 621,

and the Tennessee Human Rights Act, Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-21-

101.2 (R. 1). After Petitioner’s responses to the Banner’s requests

for documents and Petitioner’s deposition revealed that she had

stolen proprietary and confidential documents from the Banner

during her employment as a confidential secretary for the Banner’s

Comptroller, the Banner moved for summary judgment. (R. 7-9).

The grounds for the motion for summary judgment (“Motion”)

were that Petitioner’s admission of theft left no genuine disputes of

material fact. Specifically, the Motion posited that Petitioner’s

admission that had the Banner known of the theft she could and

would have been discharged and the undisputed testimony of four

of the Banner’s principals precluded Petitioner from any relief

under the doctrine of after-acquired evidence of wrongdoing (“the

doctrine”). (R. 21-24).

Petitioner sought and was granted an extension of time to

respond to the Banner’s Motion. (R. 10 & 12). Both before and

during that time, Petitioner conducted discovery, taking the

depositions of four of the Banner’s principals.3

1. The Banner is a closely held private corporation, with no parent or

subsidiary company, in the business of publishing a daily newspaper known as

the Nashville Banner.

2. Analysis of Plaintiff’s age discrimination claim under Tenn. Code Ann.

§ 4-21-101 is the same as under the ADEA. Trentham v. K-Mart Corp., 806 F.

Supp. 692 (E.D. Tenn. 1991).

3. Specifically, Petitioner deposed Irby C. Simpkins, Jr., President of the

Banner and Publisher of the Nashville Banner; Edward F. Jones, Editor of the

Nashville Banner; Imogene Stoneking, Comptroller of the Banner and

Petitioner’s supervisor; and Elise D. McMillan, General Counsel and Executive

Vice President of the Banner.

3

After these depositions, Petitioner opposed the Banner’s

Motion by arguing that summary judgment should be denied

because her wrongdoing was not serious enough to warrant

termination. (R. 25). The district court granted the Banner’s

Motion, finding that the undisputed facts revealed that the nature

and materiality of Petitioner’s misconduct provided “adequate and

just cause for her dismissal as a matter of law, even though her

misconduct was unknown to the Banner at the time of her

discharge.” App. 17a.

On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit affirmed, holding that, based on the facts of this case, the

district court properly granted summary judgment. App. 2a.

Specifically, the Sixth Circuit relied on Summers v. State Farm

Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 864 F.2d 700 (10th Cir. 1988), and two prior

Sixth Circuit cases4 to hold that the doctrine applied to Petitioner’s

misconduct during her employment. App. 4-8a. In addition, the

Sixth Circuit rejected Petitioner’s argument that she was justified

in having a “lever with which to resist” a possible discharge, App.

8a, noting that adoption of this theory would justify an employee’s

taking money from her employer to support herself in anticipation

of unlawful discharge. App. 9a.

In her Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, Petitioner concedes the

applicability of the doctrine but asks this Court to select the

Eleventh Circuit’s approach to the remedies available under the

doctrine rather than that taken by the Sixth Circuit. Petition at 11.

B. Counter Statement of the Facts

In reviewing the Motion, the district court viewed the facts

in the light most favorable to Petitioner. However, the statement of

4. Johnson v. Honeywell Info. Sys. Inc., 955 F.2d 409 (6th Cir. 1992);

Milligan-Jensen v. Michigan Technological Univ., 975 F.2d 302 (6th Cir. 1992),

cert, granted, 113S.Ct. 2991, cert, dismissed, 114S.Ct. 22(1993).

4

the facts in the Petition is so misleading that Petitioner has in effect

attempted to recast the facts as developed by the record. Petitioner

has omitted many material facts developed in the proceedings

below and misstated other facts that are relevant to the disposition

of the Petition. Accordingly, the Banner presents the facts as they

appear in the record.5

Petitioner was an at-will employee who was one of nine

employees laid off October 31,1990, as part of a reduction in force

the Banner instituted to address financial concerns.6 (R. 2). From

March, 1989, through October 31, 1990, Petitioner held the

position of secretary to Imogene Stoneking, the Banner’s

Comptroller.7 (R. 1). Petitioner’s duties in this position included

maintaining personnel files, assisting in the preparation of the

Banner’s annual budget, processing time sheets, and doing various

other tasks assigned to her by Ms. Stoneking. (R. 1).

As secretary to the Comptroller, Petitioner had access to

confidential documents and information, including payroll data,

financial information, personnel files, and other confidential

records. (R. 8). In her deposition, Petitioner admitted that she

5. It should be noted that Petitioner fails to cite to any record other than the

district and appellate courts’ decisions.

6. In her statement of the facts, Petitioner concedes that she was aware of

the Banner’s financial concerns, but she adds an incorrect gloss to her factual

statement when she states that the Comptroller “began to suggest retirement,”

implying that the question of Petitioner’s retirement came up more than once. In

her deposition, Petitioner admitted that the Comptroller asked Petitioner about

her retirement plans once, and only once. (R. 39).

7. Contrary to her statement in her Petition, Petitioner was not employed

by the Nashville Banner Publishing Co. since May, 1951. Petitioner was

employed by the corporate defendant in this case only since 1971. (See

generally, R. 39).

5

understood that all of this information was confidential and

proprietary business information. (R. 39). Petitioner also admitted

that she understood that the Banner was relying upon her to

safeguard the confidentiality of the business and proprietary

information to which she had access as the Comptroller’s

secretary. (R. 39). She further admitted knowing that she was to

keep this information strictly confidential and that the failure to do

so could and would result in termination. (R. 39).

Thus, despite holding a position of trust with the Banner and

despite being fully aware of her obligation to maintain the

confidentiality of the information to which she was privy,

Petitioner admitted during her deposition that she surreptitiously

photocopied and removed from the Banner’s premises several

sensitive financial documents and personnel records.

Contrary to Petitioner’s implication in her Petition that the

documents she copied and took home were nothing more than

published “newspaper financial information,” Petition at 5 n. 2, the

stolen documents contained financial data of the Banner, its

officers, and others. Specifically, the Banner discovered during

Petitioner’s deposition that, before she was terminated, Petitioner

had copied the Nashville Banner Fiscal Period Payroll Ledger that

set forth salaries and related information pertaining to the Banner’s

owners, several management personnel, and certain administrative

staff. (R. 39). She also copied the Nashville Banner Publishing

Co.’s 1989 Profit and Loss Statement. (R. 39).

Petitioner admitted that in copying these documents she

intentionally disobeyed the Comptroller’s specific instructions to

shred them. (R. 39). Instead, she photocopied the documents and

used them for her own purposes. (R. 39). Knowing full well the

highly confidential nature of these documents and her duty to

maintain their confidentiality, Petitioner removed them from the

6

Banner’s premises and shared the information with her husband.8

(R. 39). Because Petitioner knew that she was not authorized to

take and use these documents for her own purposes, she copied and

removed them secretly, not telling the Comptroller or anyone else

at the Banner that she had copied these documents or that she was

removing them from the premises. (R. 39).

In addition to the documents she had been instructed to shred,

Petitioner secretly copied and removed from the Banner’s

premises several documents contained in the personnel file of a

Banner manager. (R. 39). Among these documents was a

confidential agreement entered into between the Banner and the

manager and a series of documents relating to that agreement. (R.

39). Petitioner admitted that she understood she was not authorized

to copy any of these documents, much less remove them from the

Banner’s premises and share the contents with anyone. (R. 39).

The first time the Banner became aware that Petitioner had

secretly copied and removed confidential financial and personnel

documents was during her deposition on December 18,1991.9 (R.

8. Petitioner divulged to her husband confidential and proprietary salary

information concerning the following individuals: Irby Simpkins, President of

the Banner and Publisher of the Nashville Banner; Brownlee Currey, Chairman

of the Board of the Banner; Elise McMillan, the Banner’s General Counsel and

Executive Vice-President for Administration; Imogene Stoneking, Comptroller;

Edward F. Jones, Editor of the Nashville Banner; Jack Gunter, Director of

Special Projects; and various secretaries. (R. 39).

Although Petitioner tries to understate the severity o f her misconduct, the

Banner was forced to obtain a protective order in the district court in order to

protect the proprietary and confidential information that Petitioner had put at the

unfettered disposal o f herself and her husband. (R. 6).

9. During discovery, Petitioner produced confidential and proprietary

documents belonging to the Banner. However, the Banner did not know when or

how Petitioner obtained these documents until her deposition.

7

8). Petitioner testified that she took these documents without

authorization from and without asking anyone at the Banner, that

she had been instructed to shred two of the documents she copied,

and that she understood that these actions could and would subject

her to termination. (R. 39). In her deposition, she testified that the

reason she copied and removed the documents was for her

“insurance” and “protection.” App. 12a.10

As a result of the discovery of Petitioner’s misconduct, the

Banner informed her by letter that her actions constituted

deliberate misconduct involving breach of trust and confidentiality

obligations essential to her position as a confidential secretary. (R.

8). In this letter, in his Affidavit, and in his deposition, the Banner’s

President stated that had the Banner been aware of Petitioner’s

breach of trust and misconduct at the time that it occurred or at any

time thereafter the Banner would have terminated her immediately.

(R. 8; R. 29). Similarly, in affidavits and again in deposition

testimony, every other member of the Banner’s management

involved in Petitioner’s employment stated unequivocally under

oath that they would have terminated or recommended termination

of Petitioner. (R. 8). Even though Petitioner’s counsel deposed

each of these managers, she is able to offer nothing to rebut their

testimony. App. 17a.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This Court should not grant certiorari because the facts of this

case would entitle Petitioner to no relief in any of the circuits that

have applied the doctrine. Therefore, summary judgment was

properly granted against Petitioner.

10. It was only in an affidavit filed three months after her deposition to

resist the Banner’s Motion that Petitioner decided that her intent in taking the

documents was to learn information about her job security concerns. (R. 28). The

Banner’s objection to Petitioner’s effort to recast the facts by way o f a sham

affidavit was mooted by the district court’s grant of the Motion.

8

All of the circuits that have considered the doctrine have

applied it, and Petitioner concedes the applicability of the doctrine.

Further, all of the circuits have recognized that the doctrine is to be

applied on a case-by-case basis and that there is no absolute rule

regarding the doctrine. Based on the facts of each case and on the

employer’s proof, the circuits have applied the doctrine either to

preclude all relief or to allow only limited relief. Therefore,

contrary to Petitioner’s contention, the circuits are not

“irreconcilably in conflict.” Close inspection of the cases reveals

that the differences between the circuits result not in the

application of the doctrine but from each set of facts presented.

In the present case, Petitioner disputes only the denial of back

pay by the Sixth Circuit. However, based on a case-by-case review,

the unique facts of this case would bar Petitioner from any relief,

including back pay, because the undisputed facts established that

she engaged in serious on-the-job misconduct and that this

misconduct would have led to her termination if her employer had

known about it while she was employed. Thus, based on the

undisputed material facts of this case, Petitioner would have been

denied relief under the approaches taken by all of the circuits that

have addressed the doctrine.

Therefore, this case is not a proper vehicle for the Court to

review the availability of back pay under the doctrine.

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

I.

RELIEF WAS PROPERLY DENIED TO PETITIONER

BECAUSE PETITIONER ADMITS BOTH SERIOUS

WRONGDOING AND THE APPLICABILITY OF THE

DOCTRINE.

Petitioner misleads the Court when she inaccurately states

9

that this case presents the same issue as Milligan-Jensen v.

Michigan Technological Univ., 975 F.2d 302 (6th Cir. 1992), and

that the circuits are in irreconcilable conflict over the issue. All that

Petitioner has done is to restate the question presented from

Milligan-Jensen, ignoring the obvious differences that the two

cases present. Based on the unique facts of the present case, any

conflicts between the circuits dissolve, making Petitioner’s

statement misleading and inaccurate.

A. All Circuits That Have Considered The Doctrine Have

Adopted It.

Specific articulation of the doctrine arose in Summers v. State

FarmMut. Auto. Ins. Co., 864 F.2d 700 (10th Cir. 1988). The Tenth

Circuit in Summers reasoned that, even though the employee’s on-

the-job misconduct was not the actual cause for the discharge,

summary judgment for the employer was proper because the

employee’s misconduct precluded any relief. Id. at 708. Since the

Summers decision11, the Sixth12, Seventh13, and Eleventh Circuits14

11. In addition to the Summers case, the Tenth Circuit has applied the

doctrine in two other cases: O ’Driscoll v. Hercules, Inc., 12 F.3d 176 (10th Cir.

1994) and Faulkner v. SuperValu Stores, Inc., 3F.3d 1419 (10th Cir. 1993).

12. Milligan-Jensen v. Michigan Technological Univ., 975 F.2d 302 (6th

Cir. 1992), cert, granted, 113 S. Ct. 2991, cert, dismissed, 114 S. Ct. 22 (1993);

Paglio v. ChagrinValley Hunt Club Corp., 1992U.S.App. Lexis 15,399 (6th Cir.

June 25, 1992); Dotson v. United States Postal Service, 977 F.2d 976 (6th Cir.

1992), cert, denied, 113 S. Ct. 263 (1992); Johnson v. Honeywell Info. Sys., Inc.,

955 F.2d 409 (6th Cir. 1992).

13. Kristufekv. Hussmann Foodservice Co., 985 F.2d 364 (7th Cir. 1993);

Washington v. Lake County, III., 969 F.2d 250 (7th Cir. 1992); Reed v. AMAX

Coal Co., 971 F.2d 1295 (7th Cir. 1992); Smith v. General Scanning, Inc., 876

F.2d 1315 (7th Cir. 1989).

14. Wallace v. Dunn Constr. Co., Inc., 968F.2d 1174 (11th Cir. 1992).

10

have recognized the applicability of the doctrine under certain

circumstances. In addition, district courts in many circuits15 have

applied the doctrine. Therefore, the circuits are not in

irreconcilable conflict over the doctrine.

Further, all of the circuits have applied the doctrine with care

to avoid having employers rummage through a discharged

employee’s file and ferret out minor infractions to justify after-the-

fact an otherwise discriminatory discharge. See, e.g., Johnson v.

Honeywell Info. Sys. Inc., 955 F,2d 409, 414 (6th Cir. 1992);

Washington v. Lake County, III., 969 F.2d 250, 255-56 (7th Cir.

1992). The standard for the doctrine is high to avoid just such

abuse. Thus, where — and only where — the employee’s

wrongdoing is of the magnitude that there would be just and proper

cause for termination and the evidence is undisputed that the

employer would in fact have discharged the employee does the

doctrine come into play.

15. The following is a representative, not exhaustive, list: Moodie v.

Federal Reserve Bank, 831 F. Supp. 333 (S.D. N.Y. 1993); Massey v. Trump’s

Castle Hotel & Casino, 828 F. Supp. 314 (D.N.J. 1993); Rich v. Westland

Printers, 62 Fair Empl. Prac. Cases (BNA) 379 (D.Md. 1993); Russell v.

Microdyne Corp., 830 F. Supp. 305 (E.D. Va. 1993); Agbor v. Mountain Fuel

Supply Co., 810 F. Supp. 1247 (D. Utah 1993); Malone v. Signalj Processing

Technologies, Inc., 826 F. Supp. 370 (D. Colo. 1993); O ’Day v. McDonnell

Douglas Helicopter Co., 784 F. Supp. 1466 (D. Ariz. 1992), appeal docketed,

No. 92-15625 (9th Cir. 1992); Benson v. Quanex Corp., 58 Fair Empl. Prac.

Cases (BNA) 743 (E.D. Mich. 1992); Redd v. Fisher Controls, 814 F. Supp. 547

(W.D. Tex. 1992);Bongerv. American Waterworks, 7 8 9 F. Supp. 1102 (D. Colo.

1992); DeVoe v. Medi-dyn, Inc., 782 F. Supp. 546 (D. Kan. 1992); George v.

Meyers, No. 91-2308-0,1992 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 6419 (D. Kan. April 24,1992);

Sweeney v. U-Haul Co. of Chicago, 55 Fair Empl. Prac. Cases (BNA) 1257 (N.D.

111. 1991); Churchman v. Pinkerton’s, Inc., 756 F.Supp. 515 (D. Kan. 1991);

Punahele v. United Air Lines, Inc., 756 F. Supp. 487 (D. Colo. 1991); Mathis v.

Boeing Military Airplane Co., 719F. Supp. 991 (D. Kan. 1989).

11

Those circuits that have adopted the doctrine have taken

slightly different approaches to how an employee’s serious and

material misconduct should affect his or her remedy. The Tenth and

Sixth Circuits and the Seventh Circuit in Washington have agreed

that serious misconduct should bar any remedy. The Eleventh

Circuit and the Seventh Circuit in Kristufek v. Hussmann

Foodservice Co., 985 F.2d 364 (7th Cir. 1993), have declined to cut

off all prospect of back pay under the specific facts that those cases

presented. Indeed, the Eleventh Circuit has stated unequivocally

that the scope of the remedy is best determined on a case-by-case

basis. Wallace v. Dunn Constr. Co., Inc., 968 F.2d 1174,1181 (11th

Cir. 1992).

B. The Doctrine Fully Applies To The Undisputed Facts Of

This Case.

All of the facts necessary to apply the doctrine are undisputed

in the present case. Petitioner admitted that she secretly copied

confidential and proprietary business information from the Banner

while she was employed there. Petitioner then removed the

documents from the Banner’s premises and shared the contents

with her husband and attorney.

Petitioner admitted knowing that this information was to be

kept strictly confidential and that the failure to do so could and

would result in termination. She also admitted that she

intentionally disobeyed specific instructions by her superior to

shred some of the documents. Petitioner also testified under oath

that she took confidential documents from a manager’s personnel

files, including information about the manager’s salary and related

matters, to use for her own benefit. Petitioner did not have

permission to take any of these documents.

The district court found Petitioner’s actions to be both

undisputed and the type of misconduct contemplated by the

doctrine.

12

The Court does not hold that any or all

misconduct during employment constitutes

just cause for dismissal or serves as a complete

defense to a wrongful discharge action. The

Court concludes, however, that Mrs.

McKennon’s misconduct, by virtue of its

nature and materiality and when viewed in the

context of her status as a confidential secretary,

provides adequate and just cause for her

dismissal as a matter of law, even though her

misconduct was unknown to the Banner at the

time of her discharge.

App. 16a-17 a.

In addition, the district court found that the undisputed

evidence showed that the Banner fully met its burden of proving

that Petitioner would have been terminated for her misconduct had

the Banner known about it while she was still employed there.

Under oath, the President and three top-level Banner managers all

testified unequivocally that had the Banner been aware of

Petitioner’s breach of confidentiality and misconduct at the time

that it occurred, or at any time thereafter, the Banner would have

terminated her immediately.16 The district court also found that

Petitioner was unable to offer any evidence even tending to show

that the Banner would have continued her employment had the

Banner known of her misconduct before her termination. App. 17 a.

Indeed, Petitioner admitted that she knew she could and would

have been discharged had she breached her duty of confidentiality.

(R. 39).

16. Contrary to the misleading impression in the Petition, the Banner’s

proof that it would have fired Petitioner was not based “solely” on affidavits

from the Banner’s principals. Petitioner’s counsel also took depositions of these

principals.

13

The district court properly applied the summary judgment

standard to the facts of this case and found that because there were

no genuine issues of material fact the Banner was entitled to

summary judgment as a matter of law.

C. The Facts Of This Case Would Entitle Petitioner To No

Relief.

The facts of this case differ from those in the cases Petitioner

cites.

Applying the facts of the instant case to the position taken by

the Seventh Circuit in Kristufek would not change the result

reached by the Sixth Circuit. The Seventh Circuit in Kristufek

stated that an employee can recover back pay only where the after-

acquired evidence involved a non-critical, non-fundamental job

requirement and the employer did not adequately show that the

employee would have been fired, not just that the employee might

have been fired, for the misconduct in question.17 Kristufek, 985

F.2d at 369.

In the present case, Petitioner admitted stealing confidential

and proprietary documents from the Banner. The after-acquired

evidence of theft clearly involved a critical and fundamental job

requirement. In keeping with the standards of the doctrine, the

district court found that Petitioner’s misconduct rose to the level of

being serious and material. Also, the district court found that the

Banner would have fired Petitioner for theft of the confidential and

proprietary documents. Therefore, even under the Seventh

17. The court in Kristufek distinguished Summers based on significant

factual and proof differences between the cases. In Kristufek, the employer did

not prove that it would have fired the employee for his misconduct, whereas in

Summers the employer met this burden. As in Summers, the Banner proved

unequivocally that it would have fired Petitioner.

14

the Seventh Circuit’s approach in Kristufek, Petitioner would not

be entitled to any relief.18

Only seven months before the Kristufek decision, the Seventh

Circuit relied on Summers in deciding Washington. Applying the

Summers rule, the Seventh Circuit panel affirmed summary

judgment in favor of the employer and concluded that the

employee was not entitled to relief because he would have been

fired for the later-discovered serious misconduct.19 Washington,

969 F.2d at 256-57. Curiously, the Seventh Circuit in Kristufek did

not mention its prior decisions in Washington or Reed. However,

from the different outcomes in Kristufek and Washington, it is clear

that the Seventh Circuit, like the Eleventh Circuit, has not adopted

a stringent rule regarding the doctrine but will decide each case on

its facts. This is contrary to Petitioner’s assertion that the Seventh

Circuit has taken an “intermediate position on this issue.” Petition

at 9.

Like the other circuits that have addressed this issue, the

Eleventh Circuit in Wallace, declined to adopt a rigid rule and

specifically stated that it will review the issue of after-acquired

18. Significantly, the court in Kristufek addressed the issue of damages

only after upholding the jury’s finding of discrimination. The court in Kristufek

held that sufficient evidence of discrimination was presented for the jury to find

pretext. Petitioner has presented no evidence of discriminatory pretext in this

case. See Section II, infra. Most o f the cases allowing limited relief under the

doctrine have involved evidence of discrimination.

19. Between the time of the decisions of Washington and Kristufek, the

Seventh Circuit decided Reed v.AMAXCoal Co., 971 F.2d 1295 (7th Cir. 1992).

In Reed, the court, upholding summary judgment for the employer on other

grounds, stated that under Summers the employer would have been entitled to

summary judgment had it proved that it would have fired the employee for the

misconduct at issue. Id. at 1298. If the employer had met its burden of proof, then

the employee would have been denied any relief. Id.

15

evidence on a case-by-case basis. 968 F.2d at 1178. Thus, in the

absence of a hard and fast rule, the Eleventh Circuit has implicitly

condoned denial of back pay in an appropriate situation, which the

present case presents. Therefore, the Eleventh Circuit’s decision in

Wallace is not “irreconcilably in conflict” with other circuits as

Petitioner asserts.

Petitioner concedes that the Eleventh Circuit in Wallace

recognized that wrongdoing can limit the relief available.

Notwithstanding its acceptance of the doctrine, the Eleventh

Circuit in Wallace hypothesized some extreme possibilities of

employer abuse. See 968 F.2d at 1180-81. The present case defies

the “parade of horribles” listed in Wallace, which do not occur in

the after-acquired evidence situation if the standards of the

doctrine are properly applied. The requirements that misconduct

be material and job related and that the employer carry its burden of

proving that it would have fired the employee had it known the

truth fully protect against any employer abuse. Actually, this case

presents the perfect scenario for the application of the doctrine:

Petitioner voluntarily divulged to the Banner and later admitted to

her serious misconduct. There is no evidence of employer abuse in

the present case.

Petitioner cites to this Court’s recent decision in ABF Freight

System, Inc. v. NLRB, 114 S. Ct. 835 (1994), stating that it deals

with a related issue. However, ABF is significantly distinguishable

from the present case and, therefore, is not applicable here.

First, ABF is not an after-acquired evidence case.20 The

employer in ABF knew prior to making the termination decision

that the employee had lied about why he was late to work. After the

employee was terminated, he again lied, this time under oath to an

20. The ABF decision does not mention or refer to the after-acquired

evidence doctrine and does not cite any after-acquired evidence cases.

16

NLRB Administrative Law Judge. Second, this Court in ABF did

not judge the merits of whether the employee should have been

reinstated with back pay, even though he committed perjury.

Rather, the only question was whether the agency had the

discretion to fashion the remedy it did in the case.21

However, this Court did not completely ignore the merits of

the agency’s decision. This Court agreed with the employer that,

consistent with its appraisal of the employee’s false testimony,

reinstatement and back pay should have been precluded. Id. at 839.

Justices Scalia and O’Connor in their concurring opinion invoked

the “unclean hands” doctrine and stated, “[t]he principle that a

perjurer should not be rewarded with a judgment — even a

judgment otherwise deserved — where there is discretion to deny

it, has a long and sensible tradition in the common law.” Id. at 842.

This statement applies with equal merit to the misconduct of theft

and deceit in the present case.

Third, because of the facts presented by ABF and the narrow

issue before it, this Court did not have to determine whether the

employer could prove that it would have fired the employee for the

misconduct as is required in after-acquired evidence cases. Again,

however, this Court did not completely ignore this issue. This

Court noted that “[t]he Board found that the record in this case

unequivocally established that ABF did not treat Manso’s

dishonesty ‘in and of itself as an independent basis for discharge or

any other disciplinary action.’” Id. at 838 n. 5 (citing 304 N.L.R.B.

585,590(1991)).

Fourth, as in after-acquired evidence cases that have allowed a

plaintiff limited relief in the form of back pay, there was direct

21. This Court’s decision to uphold the NLRB’s ruling was based on

mandatory deference to the agency in the absence of evidence that the agency’s

decision was arbitrary, capricious, or manifestly contrary to law. AFB, 114 S. Ct.

at 839.

17

evidence of unlawful conduct by the employer in support of the

employee’s contention that the termination decision was

pretextual. There is no evidence of pretext in the present case. See

Section II, infra. Therefore, this Court’s decision in ABF does not

restrict the application of the after-acquired evidence doctrine to

preclude relief in cases where the employer can prove that it would

have terminated an employee for serious on-the-job misconduct

discovered after the employee’s termination.

Contrary to Petitioner’s unfounded assertion, the facts

presented in the present case are more obviously compelling than

those in Milligan-Jensen, providing even stronger support to apply

the doctrine to preclude relief to Petitioner. Unlike the present

case, in Milligan-Jensen there was direct evidence of sex

discrimination by the employer.22 Petitioner’s attempt to argue that

Milligan-Jensen is somehow materially different from the present

case because it involved application fraud is also misguided. The

Sixth Circuit in both Milligan-Jensen and this case applied the

same standard: whether the employee would have been fired if the

employer had known of the serious misconduct. Once there is a

finding of “would have been fired,” whether the misconduct

occurred prior to or during employment is irrelevant. Milligan-

Jensen, 975 F.2d at 304-05 & n. 3.

Further, there is no proof that the Banner’s actions in any way

caused Petitioner to steal confidential and proprietary documents,

as Petitioner asserts.23 The district court found as a matter of law

22. Petitioner’s statement that this case presents facts that are arguably

more compelling than those in Milligan-Jensen has a paradoxically boomerang

effect because in that case there was direct evidence of discrimination, whereas

there is none in this case. See 975 F.2d at 303 (“You’re the woman, aren’t you?

. . . You’ve got the lady’s job.”). In this case, there is neither direct nor

circumstantial evidence of discrimination.

23. It goes without saying that stealing personal and proprietary

information has no connection to protection from any future alleged

discrimination.

18

that Petitioner’s motivation in stealing the documents was

irrelevant to the application of the doctrine. Therefore, when

compared to Milligan-Jensen,™the facts of the present case should

compel this Court to deny certiorari because the Sixth Circuit

clearly reached the proper result even in light of decisions from

other circuits.

II,

SUMMARY JUDGMENT WAS PROPER BECAUSE

PETITIONER SHOWED NO PRETEXT.

Petitioner offered no evidence to rebut the Banner’s proof that

she would have been terminated had it discovered her misconduct

while she was employed. App. 17a. In the absence of any showing

that the Banner’s explanations were pretextual, summary

judgment for the Banner was proper.

Just recently, this Court clarified the evidentiary formula for

proving pretext: “a reason cannot be proved to be ‘a pretext for

discrimination’ unless it is shown both that the reason was false

and that discrimination was the real reason.” St. Mary’s Honor Ctr.

v. Hicks, 113 S. Ct. 2742,2752 (1993) (emphasis in original). There

are no facts in this case to support even an inference, much less

proof, either that the Banner’s evidence that Petitioner would have

been discharged was false or that the Banner fabricated this reason

to discriminate against Petitioner.

Even if Petitioner had not admitted the applicability of the

doctrine to her case, summary judgment against Petitioner would

have been properly granted because she is unable to meet this

Court’s standard to survive summary judgment under Matsushita 24

24. Significantly, the Sixth Circuit in Milligan-Jensen reversed the district

court’s denial o f summary judgment and directed that judgment be entered in

favor of the employer.

19

Electrical Industrial Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp., 475 U.S. 574,

(1986); Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., A l l U.S. 242 (1986); and

Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, A l l U.S. 317, (1986). “[T]he plain

language of Rule 56(c) mandates the entry of summary judgment,

after adequate time to conduct full discovery and upon motion,

against a party who fails to make a showing sufficient to establish

the existence of an element essential to that party’s case, and on

which that party will bear the burden of proof at trial.” Celotex,

477U.S,at322.25

As the facts show, Petitioner had adequate time to conduct full

discovery. After Petitioner served interrogatories and document

requests and received timely responses, Petitioner sought and was

granted leave to complete additional depositions to rebut the

Banner’s Motion. Both before and after the extension of time,

Petitioner deposed four of the Banner’s principals.

Notwithstanding ample time to discover any pretext on the

part of the Banner, Petitioner found none. Petitioner made no

showing that the Banner fabricated evidence against her or treated

her differently from other employees. The record is clear that the

Banner fully carried its burden of proof and that Petitioner made no

showing that this proof was pretextual. See St. Mary’s Honor Ctr.,

113 S. Ct. at 2748. Accordingly, under this Court’s 1986 trilogy of

cases, summary judgment was proper.

25. The ultimate burden is on the non-moving party to show the existence

of a genuine issue of material fact: “[w]hen the moving party has carried its

burden under Rule 56(c), its opponent must do more than simply show that there

is some metaphysical doubt as to the material facts . . . . In the language of the

Rule, the non-moving party must come forward with ‘specific facts showing that

there is a genuine issue for trial.’ Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 56(e).” Matsushita, 475

U.S. at 586-87. (emphasis supplied). Finally, “the plaintiff must present

affirmative evidence in order to defeat a properly supported motion for summary

judgm ent,. . . even where the evidence is likely to be within possession of the

defendant, as long as the plaintiff had had a full opportunity to conduct

discovery.” Anderson, A ll U .S. at 257.

20

Petitioner’s hypothetical argument betrays a

misunderstanding of this trilogy of cases and of her ultimate

burden. Petitioner argues that if the Banner had known about and

terminated her for stealing the documents she could simply have

claimed that the reason for discharging her was pretextual and had

a jury trial on the issue. Petition at 10. This argument is without

merit.

Petitioner has the ultimate burden to come forward with more

than “some metaphysical doubt as to the material facts” in order to

present a jury question. Matsushita, 475 U.S. at 586-87. Petitioner

could not merely have “alleged that the Banner’s reason was a

pretext for age discrimination, and had a jury trial on the issue.”

Petition at 10. Rather, in the face of a properly supported motion

for summary judgment, Petitioner would be required to present

affirmative evidence of pretext, Anderson, A ll U.S. at 257, tending

to show that the Banner’s reason for termination was false or that it

would have continued her employment. St. Mary’s Honor Ctr. ,113

S.Ct. at 2751-54.

In the present case, Petitioner has come forward with not even

a scintilla of either pretext or discrimination. If Petitioner had been

able to show pretext, her hypothetical might have some credibility,

but the undisputed facts of the present case would not entitle

Petitioner to a jury trial on the issue of pretext. Thus, even if

Petitioner had not conceded that her misconduct warranted

application of the doctrine to her claim of discrimination, her case

would remain subject to summary judgment, contrary to

Petitioner’s hypothetical.

21

III.

PETITIO N ER RELIES ON INAPPLICABLE LAW

AND POLICY.

Petitioner’s reliance on Section 107 of the Civil Rights Act of

1991 (“CRA 1991”) both is misplaced and undermines her plea

that what she characterizes as the remedy “rule”26 by the Eleventh

Circuit be adopted. First, CRA 1991 is inapplicable to the ADEAin

regard to proof or remedy. Second, CRA 1991 does not apply to

conduct that occurred before the effective date of this Act,

November 21, 1991, and to a lawsuit filed before that date.

Landgrafv. USI Film Prods., 1994 U.S. LEXIS 3292 (April 26,

1994). Here, both the Banner’s reduction in force and the lawsuit

occurred well before November 21,1991.27

Petitioner points to the EEOC’s position taken in its amici

curiae brief in support of the grant of certiorari in Milligan-Jensen.

Whatever position that the EEOC takes when it is litigating in its

advocacy role is irrelevant here, but its policy guidance statements

are relevant. Before CRA 1991, which is the applicable time for

this case, the EEOC issued guidance directing its own staff to

follow Summers:

[/]n these circumstances, as in cases where

discrimination is proved through

circumstantial evidence, the employer may be

able to limit other relief available to the

plaintiff by showing that after-the-fact lawful

reasons would have justified the same action.

26. The Eleventh Circuit has not adopted an inflexible “rule.” Rather, the

Wallace decision adopted a case-by-case analysis.

27. Even if CRA 1991 were applicable, § 107(b) specifically disallows

any back pay, which is what Petitioner seeks.

22

For example, if a charging party is

terminated for discriminatory reasons, but the

employer discovers afterwards that she stole

from the company, and it has an absolute policy

of firing anyone who commits theft, then the

employer would not be required to reinstate the

charging party or to provide back pay.. . . See,

e.g. Summers v. State Farm Mutual Automobile

Insurance Co., 864 F.2d 700,48 EPD f 38,543

(10th Cir. 1988) (plaintiff entitled to no relief

where evidence that he falsified numerous

company records was discovered after

termination).. . .

Policy Guidance on Recent Developments in Disparate Treatment

Theory, N-915.063, EEOC Compl. Man. (BNA) N:2119 at 2132-

33 and n.17 (emphasis added).28 Under this guidance, then, the

Commission would not have sought any individual relief on behalf

of Petitioner where after-acquired evidence of misconduct showed

that termination was inevitable.

CONCLUSION

The Petition before the Court should be denied because the

Sixth Circuit’s judgment was proper in this case. Even under other

circuits’ approaches to the application of the doctrine, the result in

the present case would not be different. Petitioner concedes the

applicability of the doctrine to her admitted theft of her employer’s

confidential and proprietary documents. Petitioner admits that had

her employer known about the theft she could and would have been

discharged. At the same time that she concedes the applicability of

the doctrine to her admittedly serious wrongdoing, Petitioner is

28. After CRA1991, the EEOC changed its view of Summers. However.it

is the EEOC’s view of Summers before CRA 1991 that is instructive here

because, as previously stated, CRA 1991 does not apply to the present case.

23

asking this Court to reward her with money damages. This position

is untenable, especially in view of Petitioner’s failure to make any

showing of pretext. Therefore, it would not be a judicious

expenditure of the Court’s resources to review the present case.

Accordingly, the Banner respectfully requests that this Court

deny the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari.

Respectfully submitted,

R. EDDIE WAYLAND

Counsel o f Record

M. KIM VANCE

ELIZABETH B. MARNEY

RACHEL W. SOKOLOWSKI

KING &B ALLOW

Attorneys fo r Respondent

1200 Noel Place

200 Fourth Avenue, North

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

(615)259-3456