Duhon v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 12, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Duhon v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1973. 2d379b49-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dfbec290-93e7-4e21-bbc4-d818ecc486f3/duhon-v-goodyear-tire-and-rubber-company-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

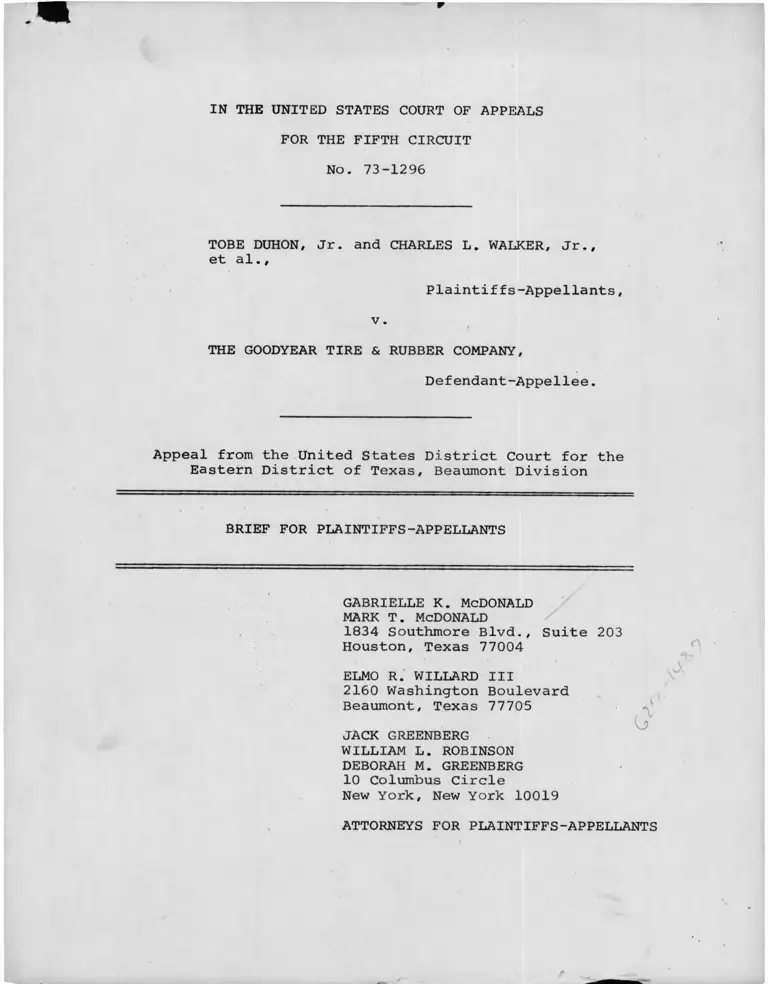

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-1296

TOBE DUHON, Jr. and CHARLES L. WALKER, Jr., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v .

THE GOODYEAR TIRE & RUBBER COMPANY,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Texas, Beaumont Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

GABRIELLE K. MCDONALD MARK T. MCDONALD 1834 Southmore Blvd., Suite 203

Houston, Texas 77004

ELMO R. WILLARD III 2160 Washington Boulevard

Beaumont, Texas 77705

JACK GREENBERG

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

DEBORAH M. GREENBERG 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-1296

TOBE DUHON, Jr. and CHARLES jL. WALKER, Jr., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v .

THE GOODYEAR TIRE & RUBBER COMPANY,

Defendant-Appellee.

CERTIFICATE

The undersigned counsel for plaintiffs-appellants

Tobe Duhon, Jr. and Charles L. Walker, Jr., et al. in

conformance with Local Rule 13(a) certifies that the

following listed parties have an interest in the outcome

of this case. These representations are made in order

that Judges of this Court may evaluate possible disqualifi

cation or recusal:

1. Tobe Duhon, Jr. and Charles L. Walker, Jr.,

Plaintiffs.

2. Class of black employees and prospective employees

of Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company whom plaintiffs represent.

3. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, defendant.

Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CASES .................................... ii

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW.......... iv

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............................ 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS ................... .......... 4

A. Background Information ............. 4

B. An Overview of Defendants Discriminatory

Practices ............................. 6

1. Job Assignment and Promotion

Policies ....................... 6

2 . Supervisory Positions ............ 8

3. Employment of Blacks in Craft Jobs .. 9

4. Exclusion of Blacks from Office

and Clerical Work ............... 10

5. Segregated Facilities ............. 10

C. High School Education Requirement ....... 11

D. Testing .................................. 12

E. Individual Plaintiffs .................... 14

1. Tobe Duhon, Jr........... 14

a. Charles L. Walker, Jr.... 18

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court Erred in Failing To Find

That Goodyear's High School Diploma Requirement Violates Title VII And In Not

Enjoining The Use Of That Requirement .... 20

A. The District Court, Having Found That

Defendants 1 Education Requirement

Was Discriminatory, Should Have Found

That Such Requirement Was Unlawful... 20

i

21

B. The District Court Should HaveEnjoined Further Use of Defendant's

High School Education Requirement....

II. The District Court's Ruling That Defendant

Had Not Unlawfully Discriminated Against

Plaintiffs Is Based Upon An Erroneous

View Of The Applicable L a w ...... ........ 21

III. The Court Below Erred In Failing To Grant

Any Relief To Blacks Whose Seniority Status

Was Adversely Affected By Goodyear's

Discrimination............................. 23

IV. The Court Below Failed To Apply The Proper

Legal Standards In Determining Whether

Goodyear Discriminated Against Blacks In

Promotion To Supervisory Jobs And Assignment

To Craft Jobs ............................. 26

V. The District Court's Denial Of Back Pay To

Plaintiffs And The Class They Represent Was

Erroneous As A Matter Of L a w ............... 27

VI. The District Court Erred In Failing To

Award Counsel Fees to Plaintiffs ............ 2 9

CONCLUSION .......................................... 30

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ...............................

TABLE OF CASES

Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc., 444 F.2d 687

(5th Cir. 1971) .................................. 10, 26

Clark v. American Marine Co., 320 F. Supp. 709

(E.D. La. 1970), aff'd 437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir.

1971) 29

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co., 421 F.2d 888,

(5th Cir. 1970) 21

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401U.S.424 (1971) ... 20,21,22, 24

Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School District,

427 F .2d 319 (5th Cir. 1971) .................. 28

Lea v. Cone Mills, 438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971) ..... 29

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970)................. 23, 25

IX

Moody v. Albermarle Paper Company, No. 72-1267(4th Cir., February 2 0, 19 73) ................ 27, 2 8

Oatis v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1968) .............................. 2

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971) ............................ 27, 28

United States v. Georgia Power Company, No. 71-3447 (5th Cir., Feb. 14, 1973) ............... 20, 25, 27, 28, 29

United States v. Hayes International Corp.,

415 F .2d 1038 (5th Cir. 1969) ................ 10, 26, 27

United States v. Hayes International Corp.,456 F .2d 112, 120 (5th Cir. 1972) ............ 14

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS

28 U.S.C. §1291 ................................. 1

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII

42 U.S.C. §§2000e et seq.......................... Passim

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f) ............................ 28

42 U.S.C. §2 000e-5 (g) ............................ 21

42 U.S.C. §2000e-6 (a) ............................ 28

Federal Rules of Civil Procedures, Rule 23(b)(2) .. 2

iii

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. A. Whether the District Court erred in failing

to rule that defendant's use of a high school education

requirement to screen persons for hiring# job assignment

and promotion is unlawful, in light of its finding that

the requirement disproportionately excluded black applicants

and the absence of any showing of relationship of the re

quirement to successful job performance?

B. Whether the District Court erred in failing

to enjoin defendant's use of a high school education re

quirement?

2. Whether the District Court erred in ruling that

defendants had not unlawfully discriminated aginst plain

tiffs because of race and dismissing the action with costs

taxed against plaintiffs, in the face of its finding of

fact that defendant's use of a high school education re

quirement and the Bennett and Wonderlic tests discriminated

against blacks?

3. Whether the District Court erred in failing to

order affirmative relief with respect to modifying defendant's

discriminatory seniority system or the adjustment of black

employees' seniority which is adversely affected by the

education and testing requirements?

4. Whether the District Court failed to apply the proper

legal standard in finding that Goodyear had not discriminated

against blacks in promotion to supervisory jobs and assignment

to craft jobs?

IV

5. Whether the District Court erroneously failed to

award plaintiffs and the class of 32 blacks hired prior to

September 13, 1965 back pay lost as a result of defendant's

discrimination?

6. Whether the District Court erroneously failed to

award plaintiffs attorneys' fees?

v

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-1296

TOBE DUHON, Jr. and CHARLES L. WALKER, Jr.,

et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v . i

THE GOODYEAR TIRE & RUBBER COMPANY,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, Beaumont Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This case of racial discrimination in employment comes

here on appeal from a final judgment of the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Texas, Beaumont Division,

entered October 17, 1972. The appeal presents issues arising

from the failure of the court below to follow the settled law

of the Supreme Court of the United States and of this Circuit

and to grant relief from the effects of a chemical company's

racially discriminatory hiring, assignment, transfer, and promotion

practices. This Court has jurisdiction of the appeal under 28

U.S.C. § 1291.

On February 4, 1967 Stephen N. Shulman, then

Chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

(EEOC), having reasonable cause to believe that a violation

of Title VII had occurred, filed a written charge with the

EEOC alleging violation by Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.

(Goodyear or Defendant), at its Beaumont Chemical Plant

(Plant) of rights guaranteed under Title VII of the Civil

1/Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq. (792a). On

or about April 25, 1969 the EEOC rendered a decision finding

reasonable cause to believe that the charge f led by the

Chairman was true (794a). Plaintiff-Appellant Tobe Duhon, Jr.,

a member of the class aggreived by the practices and policies

maintained by Goodyear which were alleged in the charge filed

by the Chairman to be unlawful, subsequently received a letter

dated May 28, 1970 from the EEOC authorizing him to institute

a lawsuit against Goodyear within thirty (30) days of receipt

thereof (798a).

2/Plaintiffs timely filed this suit as a Rule 23(b)(2)

class action on behalf of all other similarly situated black

persons under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000 et seq. on June 30, 1970. The complaint alleges historic

and continuing racial discrimination by Goodyear in hiring, job

assignment, transfer, promotion, seniority, and other terms and

conditions of employment (5a-lla). Goodyear answered this

complaint on August 6, 1970, denying plaintiffs' allegations

1/ This form of citation is to pages of the Appendix.

2/ The other plaintiff-appellant, Charles L. Walker, Jr.,

is also a member of the class aggreived by the practices

complained of in Chairman Shulman's charge. It is not, of course, necessary that he too have received a right-to-sue letter from the EEOC, under this Circuit's settled law. See Oatis v. Crown-Zellerbach Corp. 398 F.2d 496, 499 (1968).

-2-

generally (12a - 17a). On November 18, 1971 plaintiffs filed

an amended complaint to clarify and make more specific the

allegations contained in their original complaint relating to

proceedings before the EEOC and to invoke the jurisdiction of

the Court pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1981 (18a - 28a). Goodyear

answered this amended complaint on December 1, 1971, denying

plaintiff's allegations generally (29a - 34a).

After extensive discovery and a pre-trial conference,

the action came on for a trial of four days, held March 15, 16,

17 and 20, 1972 before the Honorable Joe J. Fisher (52a -791a) .

Following submission of post-trial pleadings, the District

Court on September 15, 1972 handed down its memorandum opinion

and findings of fact and conclusions of law (38a - 48a). The

Court found that Goodyear's use of a high school education

requirement and its use of the Wonderlic Personnel Test and

Bennett Test of Mechanical Comprehension resulted in discrimi

nation in the employment of black employees (40a). The Court

enjoined the use of these tests (47a - 48a) which the Court

found Goodyear already had stopped using (39a, 40a) but did

not enjoin the use of the high school education requirement.

The Court also found that Goodyear's system of division seniority

was not "designed, intended or used to discriminate against any

employee" (41a) although it did find "that portion of the senior

ity system which requires the same high school diploma and Wonder

lic and Bennett test criteria as pre-employment is discriminatory

and a violation of Title VII even though such criteria was con

tinued by the Defendant in good faith and without any intent to

discriminate against blacks" (41a - 42a). Apart from enjoining

-3-

JL

the reinstitution of the Bennett and Wonderlic tests, the

Court granted no relief to plaintiffs and ruled that plaintiffs

had failed to prove that Goodyear unlawfully discriminated

against them (48a). Judgment was entered October 17, 1972,

enjoining reinstitution of the Bennett and Wonderlic tests

and dismissing the action with costs taxed against plaintiffs

(49a). Plaintiffs timely filed their Notice of Appeal on

November 3, 1972 (51a).

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A . Background Information.

Goodyear hired the name plaintiffs, Tobe Duhon, Jr.,

and Charles L. Walker, Jr., black men, in the job classifica

tion of laborer in 1961 and 1964, respectively. Each plaintiff

sought promotion into a better and higher paying job than

laborer, but until 1967 in the case of Mr. Duhon, and 1970

in the case of Mr. Walker, they had been denied such advance

ment pursuant to Goodyear's policies and practices.

The defendant, The Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., Beaumont

Chemical Plant, is engaged in the business of producing several

types of synthetic rubber by chemical processes (65a). The

plant is divided into nine seniority divisions — Production-

Rubber, Production-Wing Chemicals, Maintenance, Utility Opera

tion, Warehousing-Shipping, Raw Materials, Transport Drivers,

Transport Attendant and Labor Group (1021a) . As of June 14,

1971 it employed in these divisions a total of 367 whites

(855a-887a) and 68 blacks (847a-853a).

Under Goodyear's seniority system an employee begins

to accrue division seniority on his first day of employment in

a particular division (540a, 1021a). Promotions are made

on the basis of division seniority (108a, 1022a). If an employee

transfers from one division to another, his division seniority

begins anew; he retains seniority in his former department for

use in case of a reduction in force, but is not permitted to

bring that seniority to the new department to which he trans

ferred.

Prior to Title VII's effective date (July 2, 1965),

blacks were hired only as laborers. The first time a black

was hired directly into a non—laborer job was September 13,

1965 (889a). White employees hired contemporaneously with

pre-September 13, 1965 blacks have had an opporutnity to ac

crue all of their seniority in non-labor departments. No

black hired prior to September 13, 1965 has had a like oppor

tunity, for even if he has transferred out of the Labor Depart

ment, he lacks some years of division seniority accrued by a

white hired at the same time but directly into the non-labor

department.

When the plant was first opened in 1961 there was

no separate labor division. Laborers were assigned to the

departments where they worked and carried their department

seniority in that department. On July 21, 1964, 19 days

after the passage of Title VII, Goodyear consolidated all of

the laborers, all of whom were black, into one department

and transferred their seniority to that Labor Department

(538a, 895a). If an employee later transferred out of the

Labor Department to one of the departments in which he had

-5-

previously worked, he would start in that department with no

division seniority even if he had worked in that division

prior to July 21, 1964 (604a).

B. An Overview of Defendant's Discriminatory Practices.

1. Job Assignment and Promotion Policies.

When Goodyear first staffed the Beaumont Chemical/

Plant, it received approximately 5,000 applications for about

100 jobs (73a, 525a, 532a). Prior to September 13, 1965, 32

blacks were hired, all into the job classification of laborer

(847a - 851a), the least skilled and lowest paid job in the

plant (42a). During this same period 195 whites were hired,

all but six into jobs higher than that of laborer (855a - 870a)

In order to be hired into a job other than that of laborer, an

applicant was required to have a high school education (65a - 66a)

and to attain a satisfactory score on the Bennett and Wonderlic

tests (586a - 587a). 23 of the 32 blacks hired from the opening

of the plant until September 13, 1965, met the education require-

at the time of their hire (847a — 851a). Goodyear's assertion

that none of the blacks attained satisfactory scores on the pre

employment tests (586a - 587a) must be evaluated in the light

of the personnel manager's testimony that there was no fixed

cut-off score (73a, 75a) . The record indicates that a white,

L. Call, who had one year of college and received a score of

26 on the Wonderlic and 38 on the Bennett test, was hired as

an operator (855a) while a black, J. Parker, who had 2 years

of college and received 29 on the Wonderlic and 36 on the

Bennett, was hired as a laborer (850). The record further

shows that four whites had scores of 18 or less on the Wonderlic

and never took the Bennett, yet were hired in 1961 into non-labor

-6-

jobs (855a-858a).

Industrial Employment Associates of Houston contracted

with Goodyear to assist it in securing employees (100a). Indus

trial Employment Associates tested employees initially and

referred them to Goodyear for employment. Goodyear's personnel

manager testified that if Industrial Employment Associates re

ferred someone to Goodyear for a particular job Goodyear knew

that the person met the minimum qualifications for that job

(101a). Industrial Employment Associates referred plaintiff

Walker for employment as a Helper after testing him (897a).

However, Goodyear employed Mr. Walker as a laborer.

On April 16, 1962, three black laborers were for the

first time allowed to transfer to other jobs (847a-848a).

From that date to July 2, 1965, only nine more black laborers

3/transferred to other jobs (847a-850a). Between July 2,

1965 and June,1971, an additional eighteen c£the 32 blacks

hired into the Labor Department before September 13, 1965 were

transferred out (847a-851a). Two of these, however, L. Lincoln

and L. Raven, are in labor type jobs (847a). As of June, 1971,

one of these 32 blacks remained in the Labor Department (R.Andrus)

and one had quit (S. Aclese) (847a, 950a). All of the blacks

transferred out of the Labor Department were performing their

jobs satisfactorily (111a, 687a).

The transfer of each, with the exception of L. Lincoln

and L. Raven, who hold the position of transportation attendant,

was delayed until satisfactory performance on the Wonderlic

and Bennett tests was achieved. Seven were required to secure

3/ One of these, C. Donatto, quit in 1967 (847a).

-7-

their G.E.D. certificate ae a condition of oligibiiity for

transfer (847a - 851a). Prior to July 2, 1965, there werei

a total of 236 transfers and promotions in non-labor department

jobs and only 17 of those were received by black employees;

this includes the transfers of the 12 blacks who transferred

out of laborer jobs prior to July 2, 1965, and five additional

promotions within non-labor departments. When these men were

allowed to transfer, they of course carried with them none of

their division seniority, for the reasons discussed above.

All of the 6 whites hired into labor jobs prior to

September 13, 1965, transferred out of the Labor Department

in less than four months. Only two of the 32 blacks hired

before September 13, 1965 have transferred out in less than

four months, while nine have remained in laborer jobs more than

six years (847a - 850a). Goodyear did not hire a single white

into the position of laborer until September 21, 1964 (79a,

868a).

2. Supervisory Positions.

As of the time of trial, the Company employed only

one black supervisor who is in the Warehouse and Shipping

Department (562a). There was testimony by blacks (S. Aclese

and H. Cooper) that they trained white employees in the Ware

house Shipping Department (432a - 433a, 454a - 455a) who were

classified as warehousemen & shippers (431a, 453a), whereas

the blacks were classified as laborers (429a - 430a, 452a - 453a).

Additionally, one black testified that he trained a white employee

who eventually became supervisor for the Warehouse and Shipping

-8-

Department (435a). Goodyear's personnel manager testified

that supervisors are selected by temporarily upgrading employees

to the position in order to make the determination of whether

they are qualified. The factors that the Company look to are

demonstrated ability to handle the job, job experience, health,

attendance and scores on the tests (559a - 560a). At all times

the supervisor in the Labor Department, which has been either

entirely or predominantly black, has been a white person who

himself has never worked as a laborer (621a - 622a).

3. Employment of Blacks in Craft Jobs.

The Maintenance Department includes four craft

categories— mechanic, instrument-electrician technician,

toolroom attendant and vehicle repairman, and materials salvage

and repairman. These are among the highest paying jobs in the

plant (939a).

Tobe Duhon became the first black ever to be employed

in the Maintenance Department, when he was transferred to the

job of mechanic third class on November 30, 1970 (197a, 199a,

847a). As of June 14, 1971, he was still the only black in

the Maintenance Department (847a - 853a). There were, as of

June 14, 1971, 109 whites in the Maintenance Department (855a -

887a).

As early as 1963, Mr. Duhon had attempted to present

his qualifications to be considered for transfer to the Main

tenance Department as a mechanic (914a). Vocational training,

which Duhon had received in 1963 (287a - 288a), was sufficient

background for that job (780a - 783a).

Duhon's qualifications were clearly superior to those

of some of the whites who were considered to have had sufficient

mechanical experience to be employed as mechanics and who had

-9-

acquired their experience by working in rice fields or as

deck hands. One of defendant's witnesses, a staff engineer

who had been master mechanic when the plant opened, admitted

that such experience as these whites had was not a sufficient

qualification for that job (780a - 783a).

4. Exclusion of Blacks from Office and Clerical Work.

There was no testimony at trial with respect to the

hiring and assignment of blacks to office and clerical jobs.

However, the Plans for Progress and Equal Employment Opportunity

Employer Information Reports for the years 1965 through 1971

(803a - 814a) clearly show a policy and practice of excluding

blacks from these jobs. The first and only black to be listed

in the category "Office and clerical" appears in the 1971

report. Goodyear, as of the time of that report, employed a

total of 22 office and clerical workers (814a). In light of

these statistics it is not surprising that the EEOC found,in

a decision dated June 3, 1971 relating to a charge filed by

Plaintiff Duhon, reasonable cause to believe that Defendant

was discriminating against blacks with respect to office and

clerical hiring policy (913a).

5. Segregated Facilities.

Defendant admits that it maintained racially

segregated locker rooms (598a), had two lunch rooms, one

used by blacks and one by whites (600a - 601a), and gave

4/ This finding is consistent with prior decisions that

statistical evidence can be used to raise an inference of discrimination. See, Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc., 444 F. 2d

687, 689 (5th Cir. 1971); United States v. Hayes International

Corp., 415 F. 2d 1038, 1043 (5th Cir. 1969).

-10-

one company picnic for whites and one for blacks (600a)

because it was, at least as to the locker rooms, following

the custom in the area (601a). It posted a notice on

February 8, 1963, advising the employees of the requirements

! Vof the Executive Order to integrate (Def. Ex. 11). However,

despite the fact that 13 blacks were hijred between February 8,

1963 and December 31, 1965̂ the first black to be assigned to

the white locker room was Plaintiff Duhon, who was assigned

there only in 1966, after having testified about Goodyear's

i

segregated facilities at a United States Civil Rights Com

mission hearing (207a). The Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission found in its Decision relating to the Chairman's

charge that the defendant unlawfully maintained segregated

facilities (797a). The Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion again found in its Decision dated June 3, 1971 that

defendant was unlawfully maintaining segregated locker room

facilities (911a, 913a).

C. High School Education Requirement

From the time it began operations in 1961, Goodyear

has required that all persons hired into any of the hourly

paid jobs except laborer have a high school diploma or GED

certificate (65a - 66a, 87a). Since September, 1964, when the

first white person was hired into the Labor Department (79a),

the Company has imposed this educational requirement as a

condition of employment in the Labor Department as well (606a-

607a). In order for a person hired into the Labor Department

to transfer out, he must possess a high school diploma or

obtain a GED certificate (79a, 595a - 596a). The Company

5/ This form of citation, and "Pi. Ex. ____", are to exhibits

of the parties which were admitted into evidence at trial, but are not reproduced in the Appendix. •

- 11 -

I

Never sought to learn whether there is a correlation between

its education requirement and job performance (69a-70a, 81a).

To the contrary, Goodyear's personnel manager testified that

two whites who did not possess high school diplomas and were

hired into jobs as utilities operator and production operator

performed their work satisfactorily (597a). It is undisputed,

and the Court below found, that this requirement has a dis

proportionate impact on blacks, inasmuch as non-whites complete

fewer years of high school than whites in Texas (39a, 901a).

D . Testing

6/From 1961 until March or April, 1971 (87a) Goodyear

required, in addition to a high school diploma or GED certifi

cate, that a person seeking a non-laborer job attain satisfac-

Vtory scores on the Wonderlic Personnel Test, Form II and the

8/Bennett Test of Mechanical Comprehension, Form AA (72a) . This

requirement applied to applicants for both hiring and transfer

into non-laborer jobs (81a - 82a). Beginning in September 1964,

this requirement was also made applicable to persons hired into

the Labor Department (606a-607a). However, apart from certain

job postings which set forth a cut-off score (82a) (and even in

these cases it was admitted that deviations might be acceptable

(83a)) there was no fixed cut-off score for hiring or transfer

(73a, 75a-77a, 81a-84a). Black employees were simply advised

6/ The court below found that Goodyear discontinued use of

the tests on March 1, 1971, (39a) but there is no evidence in

the record of the precise date.

7/ See 823a-825a.

8/ See 826a-842a.

-12-

on different occasions that they had not done well enough on

the Wonderlic and Bennett tests to transfer out of the Labor

Department (191a, 326a, 349a, 362a - 363a, 379a, 394a - 395a).

Each black employee hired prior to September 13, 1965 (the

date on which the Company first hired a black directly into

a non-labor department job Tr. 26, (78a)), had to retake the

Wonderlic and Bennett tests at least once, to transfer out of

the Labor Department.

At least until 1967, defendant permitted members of

the class to retake these tests only one additional time (the

first time having been prior to employment), and only after

the lapse of six months and a showing that additonal knowledge

or training had been acquired which might improve the prior

test scores (615a, 888a). Thus, from September, 1962 until

some time in 1967, black employees were prohibited from taking

the Wonderlic and Bennett tests a third time and thereby from

qualifying to transfer out of the Labor Department (363a, 394a).

In 1967 the defendant changed its policy and many were retested

(847a - 851a). Some members of the class took the test as many

as five times„ Some members of the class had to retake both

tests even if they had previously received a satisfactory score

on one. (847a - 851a). The average test scores of blacks were

lower than the average test scores of whites on both tests (843a).

Despite the existence of this disparate scoring pat

tern, at no time was Goodyear's use of the Wonderlic and Bennett

tests for hiring and transfer purposes validated. Goodyear's

first attempt to conduct a validation study of these tests

occurred after it was advised by the Atomic Energy Commission

that because of the requirement of the Executive Order governing

-13-

non-discrimination by government contractors, it would be

required to validate these tests or cease using them (87a).

At that time Goodyear retained the services of a psychologist

to prepare a validation study. The study showed that there

was no correlation between performance on the Wonderlic and

Bennett tests and job performance (86a).

/

E. Individual Plaintiffs

1. Tobe Duhon, Jr. J

Plaintiff Tobe Duhon, Jr., a black male, was employed

by the defendant on October 23, 1961 as a laborer in the main

tenance department (906a). At the time he was hired, he had

not completed high school, having been forced by the death of

his mother to leave school and go to work (971a). However, he

did carry certification as a mechanic, oiler and fireman in

9/the Merchant Marine (188a- 189a). Before Mr. Duhon was

employed, he was given the Bennett and Wonderlic tests (184a,

847a). Until September 27, 1964 he worked in the maintenance

department (906a), Dept. Ill (1021a), and for at least part of

that time he worked with the mechanics, and according to his

testimony, did essentially the same work as the mechanics,

who were all white (185a - 186, 190a - 191a, 285a - 287a).

Since he was not classified as a mechanic, he was not given a

tool box, so Mr. Duhon had to work out of the other men's tool

boxes. In late 1962 Mr. Duhon tried to bid on a mechanic's

job, but was told that he was not qualified because he did not

9/ The only additional qualifications acquired by Mr. Duhon

for the job of mechanic between 1961, when he was first employed,

and 1970, when he finally entered the maintenance department,

were the completion in 1963 of two semesters of mechanics' shop

at a vocational school (287a - 288a).

-14-

have a high school diploma (186a - 187a). In January, 1963I

Mr. Duhon wrote to the plant manager 'requesting an opportunity

to present his qualifications as a mechanic (914a) and received

a letter from the plant manager declining his request for a

conference and telling him to talk with his supervisor and the

personnel manager (982a). Mr. Duhon testified that he did not

do so "because a lot of times there is some things involved in

Civil Rights that the supervisors have no part of that you

should talk with management" (315a).

On April 1, 1963 Mr. Duhon received his GED certi

ficate (189a, 847a. ) He took the Wonderlic and Bennett tests

for the second time on December 10, 1963 because he wanted

to be upgraded to the job of mechanic (190a) and was told

that he had failed (191a). He was not allowed to take the

tests again until January 31, 1967, the same date on which

several of the blacks hired in the Labor Department prior to

September 13, 1965 took the test (847a - 851a). Having taken

the tests three times, Duhon was finally told that he had passed

the tests (193a). He transferred to the job of operator helper

in the Utilities Department on February 20, 1967 and was promoted

to the position of operator on August 21, 1967 (847a, 906a).

Although he wanted to work in the maintenance department, he

accepted a vacancy in Utilities because he was convinced he

10 ,would never be permitted to transfer to maintenance (193a - 195a).

On December 1, 1970, Duhon was finally transferred back

into the Maintenance Department, Dept. Ill, as a mechanic third

class (847a, 906a), the job he had first bid on in 1962. He

was the first black to hold that job (205a). On December 6,

10/ No black had ever held a job in the Maintenance Depart

ment as Duhon knew (205a).

-15-

1.071, Duhon won promoted to inccliani c mocoik! class (000a).

Ills division seniority began on November 30, 1070, despite the

fact that his service record shows that the Maintenance Depart

ment is the same one in which he was originally employed as a

laborer for almost three years, from his date of hire until

July 27, 1964, six days after the Labor Department was created

(906a). Division seniority is not used in the maintenance de

partment for promotion, but it is used for shift preference

(685a - 686a). Duhon was denied a shift preference in

September of 1971 because he did not have sufficient division

seniority. Had he been able to utilize his plant seniority

to pick the shift he wanted, he would have bemable to continue

his education (204a).

As early as 1962, Duhon began to complain about

Goodyear's unequal treatment of black employees. On July 11,

1962 he filed a complaint with the President's Committee on

Equal Employment Opportunity protesting the company's high

school education and test requirements and stating that he felt

his work experience qualified him for a mechanic's job (979a -

980a). The case was closed for lack of cause (981a). On

August 17, 1964 Duhon filed another complaint with the President's

Committee complaining about Goodyear's job assignment, upgrading

policies, harassment and segregated locker rooms (984a - 986a).

Again the President's Committee found "no evidence to substan

tiate the allegations of discrimination" (983a).

In 1965 Duhon testified against Goodyear at a hearing

held by the United States Commission on Civil Rights (207a).

His first charge filed with the EEOC, on April 19, 1966 (987a -

988a) was dismissed (997a). On March 12, 1968 Duhon filed

-16-

another charge with the EEOC (907a). With respect to this

charge the Commission found, on June 3, 1971, probable cause

to believe that Defendant had violated Title VII by engaging

lin racially discriminatory employment practices with respect

to "locker room facilities, pre-employment tests, office and

clerical hiring policy and working environment" (913a).

Fellow employees and supervisors began to harass

Duhon after he filed charges. The first time he filed a

charge he was called in by the master mechanic, Mr. Charles

Gilmer, and asked who put him up to filing the charge (209a-

210a). Mr. Gilmer, who was called by the defendant as a

witness (771a), did not deny this. When Mr. Duhon was trans

ferred into the white locker frrom in 1966, a strong chemical

was thrown into his locker (213a). Mr. Barga, the personnel

manager, admitted that a strong chemical odor was coming from

the locker and that he told Duhon that if he didn't keep his

locker closed he could expect further prombles (577a-578a).

The company took no further action with respect to the incident

(215a, 630a).

On February 3, 1971, when Duhon was working with

two white employees setting up an A-frame, part of it slipped,

pinning Duhon against a deck railing. A wrench fell, hitting and

breaking his safety helmet (219a-220a). One of the men with

whom he was working and the shift foreman, who observed the

incident, testified that it was an accident (719a, 759a). After

Duhon reported the incident to Mr. Barga, Mr. Barga told him he

was lying (220a).

On February 18, 1971 Duhon found a white cross painted

on his tool box (221a). At first he tried to ignore it, but

-17-

when his L el low employees continued to taunt him about it lie

complained to Mr. Barga and suggested that he should try to

find out who did it. Mr. Barga told Duhon that he (Duhon)

was "a Martin Luther King" and had to ignore things like

that (222a). In addition, Mr. Duhon complained to Mr. Barga

about his fellow workers putting "KKK" on their hats and

drawing signs of a person hanging with Duhon's name on them

(229a - 230a).

Mr. Barga admitted that he never issued a warning

letter to any of the employees about whom Mr. Duhon has com

plained, because he didn't find evidence of harassment (630a).

The Court below found that Duhon's career was "filled

with unpleasant incidents" but that plaintiff failed to prove

that Goodyear was responsible for or tolerated any known

harassment. The court termed the incidents "meaningless,

innocuous occurrences to which Mr. Duhon ascribed ulterior

motivation," citing the "crane accident when Duhon's hat was

knocked off" and the "stink bomb in his locker" (46a - 47a)

2. Charles L. Walker, Jr.

Goodyear hired plaintiff Charles L. Walker, a

black man, on May 25, 1964 (850a). He had a high school

diploma (850a). He was tested by Houston Industrial Employ

ment Associates (320a) and was referred to Goodyear for a job

as a helper, a non-labor job (897a). However he was employed

as a laborer (850a). Although Walker bid on other jobs he

was told he didn't qualify (324a) and he remained a laborer

until May 18, 1970, when he was transferred to the Warehouse

Shipping Department (850a). Walker retook the Bennett and

Wonderlic tests on January 31, 1967 and on May 2, 1968.

-18-

Each time he was told that he hadn't passed (325a - 326a).

However, in 1970 he was told he could move into the Warehouse

and Shipping Department (328a). In June 1971 he transferred

to the job of operator helper in the Wing Chemical Department

(330a). His seniority for the purpose of promotion dates from

his date of transfer into that department (331a).

I

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING TO FIND THAT

GOODYEAR’S HIGH SCHOOL DIPLOMA REQUIREMENT VIOLATES

TITLE VII AND IN NOT ENJOINING THE USE OF THAT

REQUIREMENT.

A. The District Court, Having Found That

Defendants * Education Requirement Was

Discriminatory, Should Have Found That

Such Requirement Was Unlawful.

The court below found that since the opening of

the Beaumont Chemical Plant in December 1961, Goodyear

has required completion of high school or attainment of

the GED certificate for employment in all positions above

11/that of laborer (39a). The court below also found that

the high school education requirement excluded a dispropor

tionate number of black applicants from employment opportu

nities (39a - 40a). No attempt was ever made to establish

the relationship of the high school education requirement

to job performance (69a - 70a, 81a), to say nothing of

showing its business necessity. It is at this point in

time a matter of hornbook law that such a requirement vio

lates Title VII. See Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401

U.S. 424 (1971); United States v. Georgia Power Company,

No. 71-3447 (5th Cir., Feb. 14, 1973), slip op. at 21.

11/ it is undisputed that this requirement applied to both

initial hire and transfer (65a - 66a, 79a). It is also un

disputed that, commencing in September 1964, this requirement

was extended to apply to hire into the Labor Department (606a-

607a) and was still in use at the time of trial (87a).

-20-

Tho district court was patently in error jn failing to find

that Goodyear's use of the high school education requirement

constituted an unlawful employment practice.

B. The District Court Should Have Enjoined

Further Use of Defendant's High School Education Requirement.

As of the time of trial, Goodyear still required

the high school diploma or GED certificate as a condition

of transfer from the Labor Department and as a condition

of hire into any job (87a). As of June 14, 1971, there

remained one black employee, R. Andrus (850a), who was still

blocked from transfer out of the Labor Department because he

lacked a high school education. In addition, all black

applicants for employment were affected by the education

requirement. While the district court in its decree enjoined

the use of the Wonderlic and Bennett tests for pre-employment

or transfer purposes, it inexplicably failed to enjoin use

of the education requirement. Since the high school educa-

tion requirement is plainly unlawful, this Court must reverse

the district court's denial of relief with respect to said

requirement. 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g); Griggs v. Duke Power

Company, supra. Such injunctive relief is crucial to the

effective implementation of Title VII as a public policy

against discrimination. See Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals

Co^, 421 F .2d 888, 891, 894 (5th Cir. 1970).

II. THE DISTRICT COURT'S RULING THAT DEFENDANT HAD NOT

UNLAWFULLY DISCRIMINATED AGAINST PLAINTIFFS IS BASED UPON AN ERRONEOUS VIEW OF THE APPLICABLE LAW.

The district court's finding that plaintiffs failed

to prove that defendant unlawfully discriminated against them,

-21-

and its dismissal of the action with costs assessed against

plaintiffs is apparently founded on the court's conclusion

that plaintiffs failed to prove any malicious intent on the

part of defendants. The court did find that defendant's edu

cation and testing requirements resulted in discrimination

against black employees (40a), and even though it erroneously

failed to grant relief with respect to the education require

ment it did enjoin reinstitution of the Bennett and Wonderlic

tests. However, the court below stressed throughout its

that the tests, high school education requirement,

seniority system, and promotional practices were imposed with—

out respect to race, and without any intent to discriminate

against blacks. Findings of Fact Nos. 4, 7, 8, 16 (40a-46a).

Thus, it is clear that the court below erroneously believed

intent to discriminate is a necessary pre—requisite to

® finding that Title VII has been violated. This view was

explicitly rejected by the Supreme Court of the United States

in Griggs v . Duke Power Co., supra:

... [G]ood intent or absence of discrimina

tory intent does not redeem employment pro

cedures or testing mechanisms that operate

as built-in headwinds" for minority groups

and are unrelated to measuring job capability.

-- Congress directed the thrust of the Act

to the consequences of employment practices, not simply the motivation.

401 U.So at 432 (emphasis in original).

This Court had previously held that the granting

of injunctive, and, a fortiori, declaratory, relief, does

not depend upon the motivation underlying the adoption or

use of discriminatory practices;

-22-

Section 706(g) limits injunctive (as opposed to declaratory) relief to cases in which the em

ployer or union has "intentionally engaged in" an

unlawful employment practice. Again, the statute,

read literally, requires only that the defendant

meant to do what he did, that is his employment

practice was not accidental.

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v. United

States, 416 F.2d 980, 996 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied,

397 U.S. 919 (1970)(emphasis in original).

The district court's dismissal of the action thus

was based on a clearly erroneous application of the law to the

facts as found by the court, and should be reversed.

III. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN FAILING TO GRANT ANY

RELIEF TO BLACKS WHOSE SENIORITY STATUS WAS

ADVERSELY AFFECTED BY GOODYEAR'S DISCRIMINA

TION.

All blacks hired by Goodyear prior to September 13,

1965 were hired into the position of laborer (78a, 847a-851a).

In order to transfer to a job other than that of laborer,

these employees had to meet Goodyear's unlawful educational

and testing requirements (79a, 81a-82a). Of the 32 blacks

hired by Goodyear prior to September 13, 1965, 30 had trans

ferred to non-laborer jobs by June 1971 (847a-851a). However,

Goodyear's discriminatory education and testing policies kept

them from transferring for as many as six years (847a-851a).

Pursuant to Goodyear's seniority system, these employees'

division seniority, which was used, inter alia, for promotion

(108a) and shift selection (685a-686a) purposes, began on the

day they transferred to non-laborer jobs, putting them at a

considerable disadvantage vis a_ vis white employees who had

always been hired directly into non-laborer jobs, and had

never, until September 20, 1964, been hired into laborer

-23-

jobs. Thus black employees (class members) presently sufler

adverse effects rooted in Goodyear's past hiring, transfer

and seniority practices.

The Court below found that Goodyear's seniority

system "was not designed, intended or used to discriminate

against any employee because of race, color, religion, sex

or national origin, but was designed for the purpose of

giving promotional opportunities within a seniority division

to those employees who had gained valuable experience in

similar job groups in such seniority division" (41a). The

significance of defendants "intent" is discussed above. The

Court did not, and on the record could not, find any business

necessity for the seniority system. Indeed, Goodyear's

personnel manager and manager of engineering both testified

that once an employee has achieved the required knowledge and

qualifications for promotion, the use of plant seniority rather

than division seniority would create no problem (110a, 691a-

693a) .

As discussed above, it is apparent that the education

and testing requirements imposed by Goodyear are unlawful

under Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra. While Goodyear's seniority

system may not, as the district court found, have been "designed,

intended or used to discriminate against any employee because

of race," it is beyond question that the Court below committed

error in granting no relief whatever with respect to the system.

This Court recently made a clear statement, which on the facts

of this case is controlling, as to the duty of the Court to

alter a seniority system which perpetuates the effects of

12/ it should be noted that even laborers who were transferred

to non-laborer jobs prior to July 21, 1964, the date the Labor

Department was established, carried no division seniority over

to their new jobs (847a-850a). -24-

12/

pant d.i wcriminnLJon nntl Mm im lu rn o f UiaL remedy s

Pull enjoyment of Title VII rights sometimes

requires that the court remedy the present effects

of past discrimination. See Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145, 154 (1965). This includes

both redressing the continuing effects of discri

minatory seniority systems, Local 189, United

Paperworkers v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th

Cir. 1969); United States v. Jacksonville Terminal

Co., supra; United States v. Hayes International

Corp., supra. and affirmative action to alter a

seniority system which is not discriminatory on

its face. If the present seniority system in fact

operates to lock in the effects of past discrimi

nation, it is subject to judicial alteration under

Title VII. Local 53, International Association

of Heat and Frost Insulators and Asbestos Workers

v. Vogler, 497 F.2d 1047, 1052 (5th Cir. 1969);Local 153, supra at 991.

Most courts, in molding appropriate remedies,

have adhered to the "rightful place" theory, ac

cording to which blacks are assured the first oppor

tunity to move into the next vacancies in positions which they would have occupied but for wrongful

discrimination and which they are qualified to fill.

Note, Title VII, Seniority Discrimination and the

Incumbent Negro, 80 Harv. L. Rev. 1260, 1268 n. 2

(1967). This is the theory which should be applied

here.

United States v. Georgia Power Co., supra, slip op. at 44-45.

Every black employee hired before September 11, 1965

has suffered from Goodyear's discriminatory education and test

ing policies and its policies of not permitting black employees

to carry to non-labor departments the seniority accrued in

those departments as laborers prior to July 1964. Therefore,

the only remedy that can possibly be adequate will be to allow

these employees to use their plant seniority for all purposes

for which division seniority is presently used. This Court

should direct the district court on remand to enter a decree

so providing.

-25-

IV. THE COURT BELOW FAILED TO APPLY THE PROPER LEGAL

STANDARDS IN DETERMINING WHETHER GOODYEAR DISCRI

MINATED AGAINST BLACKS IN PROMOTION TO SUPERVISORY

JOBS AND ASSIGNMENT TO CRAFT JOBS.

As of June 14, 1971, there were 109 whites and

one black, Tobe Duhon, in Goodyear's Maintenance Department

(847a-853a, 855a-887a). As of March 31, 1971, Goodyear

employed 21 whites and one black in office and clerical jobs (814a).

Between September 24, 1965 and January 1, 1971 Goodyear pro

moted 23 employees to supervisory jobs. One, L. Meredith,

was black (943a-949a). While these ratios are not con

clusive proof of past or present discrimination, they do

present a prima facie case. See, United States v. Hayes

International Corp., 456 F.2d 112. 120 (5th Cir. 1972);

Bing v. Roadway Express. Inc., 444 F.2d 687, 689 (5th Cir.

1971) .

As to jobs in the Maintenance Department, the court

below found that " [t]o be employed as a third class mechanic

any employee, regardless of race, must first have at least

one year's relevant craft experience" (43a). There was no

finding that such a requirement was founded on business

necessity.

The court below made no finding with respect to the

exclusion of blacks from office and clerical jobs.

As to supervisory positions, the District Court

found that " [t]here is no evidence that racial considerations

have ever been a factor in evaluating these characteristics"

and that " [t]he evidence fails to establish that any qualified

black has ever been intentionally overlooked for a supervisory

position in favor of a less qualified white employee." (45a-46a).

-26-

On facts strikingly similar to those in the instant

case, this Court in United States v. Hayes International

Corporation, supra, held that the statistical showing was

sufficient in itself to raise the inference of racial dis

crimination and that the burden was on the employer to show

a lack of qualified blacks. This Court held that the District

Court had failed to apply theproper legal standards and re

manded the case for further hearing and determination. 456 F.2d

at 120. The Court should do no less in this case.

V. THE DISTRICT COURT'S DENIAL OF BACK PAY TO

PLAINTIFFS AND THE CLASS THEY REPRESENT WAS ERRONEOUS AS A MATTER OF LAW.

Based on its finding that plaintiffs had failed to

prove that Goodyear unlawfully discriminated against them,

the court below denied back pay to plaintiffs and to the class.

If this Court reverses the district court’s finding of no

unlawful discrimination, it should direct that the district

court develop the facts relating to plaintiffs' and the class

members' entitlement to wages lost as a result of defendant's

education, testing and seniority practices. See United States

v. Georgia Power Company, supra, slip op. at 31-32; United

States v. Hayes International Corp., supra, at 121 (5th Cir.

1972; Moody v. Albemarle Paper Company, No. 72-1267 (4th Cir.,

February 20, 1973), slip op. at 15-16; Robinson v. Lorillard

Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971).

Back pay is "an integral part of the whole of relief

which seeks not to punish the respondent but to compensate the

victim of discrimination," United States v. Georgia Power

Company, supra, slip op. at 30. Accord, Harkless v. Sweeny

-27-

Independent School District, 427 F.2d 319,324 (5th cir. 1971);

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., supra at 802. Indeed, in many

cases like this one no relief other than back pay can even

partially remedy the injuries suffered during long years of

unlawful discrimination.

All members of the class have suffered economic loss

as a result of Goodyear's discriminatory practices and back

pay should be awarded on a class-wide basis. United States

13/

v. Georgia Power Company, supra, slip op. at 25-26; Moody

v. Albemarle Paper Company, supra, slip op. at 15.

It should be noted that all of the 30 blacks hired

before September 13, 1965 who have finally been allowed to

transfer to non-laborer jobs are performing satisfactorily

(111a, 687a). There is nothing on the record to indicate

that these employees acquired, during the period they were

confined to laborer jobs, any experience or training which

would better qualify them for non-laborer jobs. The only

difference between the situation of these blacks at the time

they were hired into laborer jobs and at the time they were

transferred to non-laborer jobs, in many cases more than

six years later, was that they had met Goodyear's discrimi

natory, non-job-related education and testing requirements.

Thus their entitlement to an award based upon the difference

between the pay they would have received but for Goodyear's

discriminatory practices and their actual earnings is clear.

13/ in the Georgia Power case, this Court held that class-wide

back pay could be awarded in a pattern or practice suit brought

by the Attorney General pursuant to 42 U.SoC. § 2000e-6(a),

even though this section does not explicitly provide for back pay.

A fortiori, back pay can be awarded to the class in an action

brought under 42 U»S0C„ § 2000e-5(f).

-28-

VI. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING TO AWARD

COUNSEL FEES TO PLAINTIFFS.

Had the district court not erred by failing to grant

injunctive relief as to the high school education requirement

and the seniority system and had it not erred in finding that

plaintiffs had failed to prove that defendant unlawfully

discriminated against them, it would have been required, under

the holding of this court in Clark v. American Marine Co.,

320 F. Supp. 709 (E.D. La. 1970), aff'd 437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir.

1971), to award reasonable attorneys' fees. Accord, United

States v. Georgia Power Company, supra, slip op. at 45; Lea

v. Cone Mills. 438 F.2d 86, 88 (4th Cir. 1971). If the court

agrees with our arguments with respect to the substantive

issues of this case, it should direct the district court to

award plaintiffs reasonable counsel fees in accordance with

the standards set forth in Clark v. American Marine Co., supra.

-2 9-

I

i

CONCLUSION

We respectfully urge this Court to hold that the

decision below was in error in each of the respects set forth

herein, and in reversing to enter an appropriate order correct

ing each of the district court's enumerated errors. This

Court's order should hold that (1) Goodyear's use of its

high school education requirement for transfer and hiring

must be enjoined; and (2) Goodyear has discriminated against

black employees in its hiring, assignment, transfer and

seniority practices.

The Court should also remand with instructions to enter

a decree providing full and effective relief for such dis

crimination. Such relief should specifically include:

(1) the use of full plant seniority for all purposes by black

employees hired prior to September 13, 1965; (2) an order

that back pay may be granted to plaintiffs and class members,

and proceedings to determine the amounts and distribution

thereof; and (3) an award of reasonable counsel fees to

plaintiffs.

This Court should further instruct the district court

to hold further proceedings to determine (1) whether Goodyear

discriminated against blacks in promotion to supervisory

positions and assignment to craft jobs, and (2) the amounts

-30-

and distribution of back pay.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON DEBORAH M. GREENBERG

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

GABRIELLE K. MCDONALD MARK T. MCDONALD

1834 Southmore Blvd.

Suite 203

Houston, Texas 77004

ELMO R. WILLARD III

2160 Washington Boulevard

Beaumont, Texas 77705

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

-31-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Tobe Duhon, Jr., et al. hereby certifies that on the 12th

day of March, 1973,she served copies of the foregoing

brie'f for Plaintiff s-Appellants upon counsel of record

for the other parties as listed below, by placing said

copies in the United States mail, airmail postage prepaid.

John B. Abercrombie, Esq.

Richard R. Brann, Esq.

3000 Ore Shell Plaza

Houston, Texas 77002.

Tobe Duhon, Jr., et al.

-32-