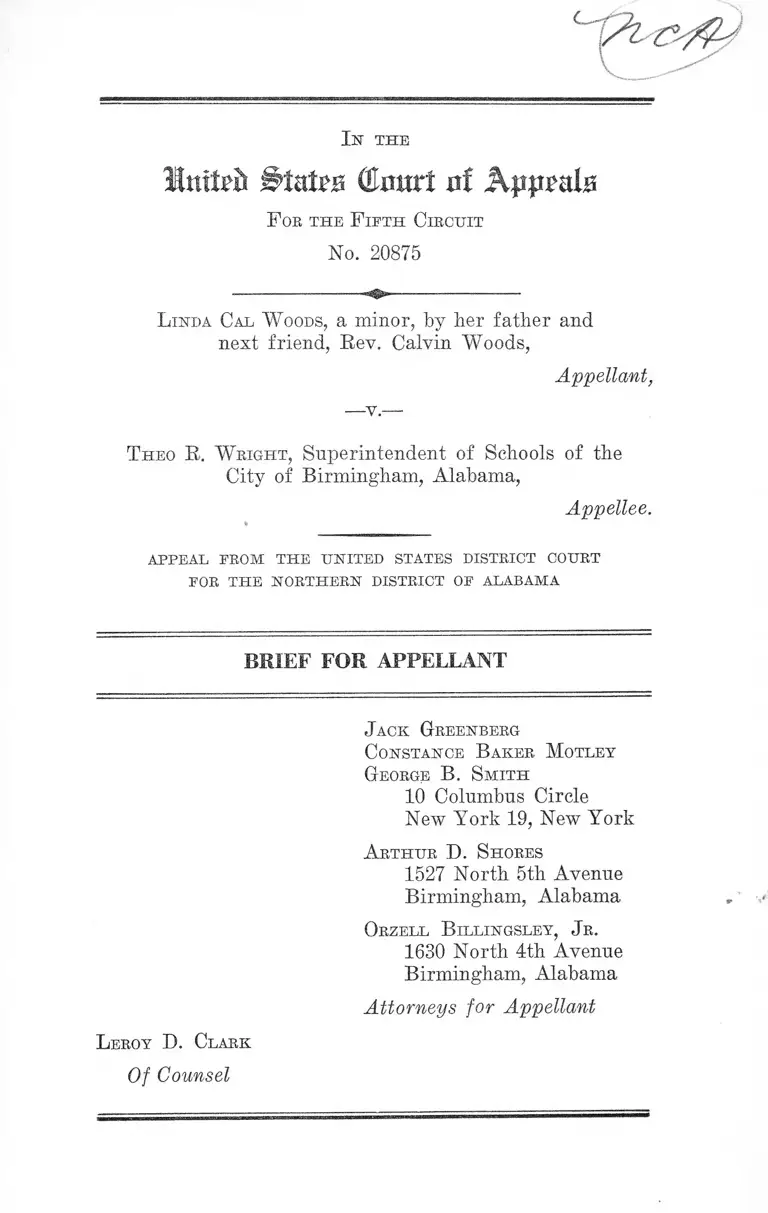

Woods v. Wright Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Woods v. Wright Brief for Appellant, 1964. 0bc6ae78-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dfdd6f6f-9176-4641-bf96-353b481c8047/woods-v-wright-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

c r

V

I s the

InlW BtnUn tour! uf Appralu

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 20875

L inda Cal W oods, a minor, by her father and

next friend, Eev. Calvin Woods,

Appellant,

— v —

T heo E. W eight, Superintendent of Schools of the

City of Birmingham, Alabama,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Jack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

George B. Smith

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

A rthur D. Shores

1527 North 5th Avenue

Birmingham, Alabama

Orzell B illingsley, J r .

1630 North 4th Avenue

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Appellant

Leroy D. Clark

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Statement of the C ase........................................................ 1

Specification of Errors ...................................................... 4

A rgument

I The Order of the District Court Is an Appeal-

able Order Both Under Section 1291 and Section

1292(a) (1) of Title 28, United States C ode....... 4

II The Suspension and Expulsion of the Negro

Students Without Notice or Hearing Violated

Bights Secured by the Due Process Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States................................................ 7

III Appellee’s Directive Is a Restraint on the Lib

erty of Expression Guaranteed by the First

and Fourteenth Amendments ............................... 9

IV Appellant’s Suspension Is a Denial of Due

Process Because It Results From an Alleged

Violation of an Unconstitutional Ordinance....... 11

Conclusion .................................................................................. 15

A ppendix

Birmingham Code, Section 1159 ................................... la

Certificate of Service.......................................................... 2a

PAGE

11

T able of Cases

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F. 2d

993 (4th Cir. 1940), cert. den. 311 U. S. 693 ............... 15

Baltimore Contractors v. Bodinger, 348 U. S. 176....... 6

Baltimore and Ohio R.R. Co. v. United Fuel Gas Com

pany, 154 F. 2d 545 (4th Cir. 1946) ............................. 5

Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U. S. 294 ........... 4

Brunson v. Board of Trustees of School District No. 1,

311 F. 2d 107 (4th Cir. 1962) ....................................... 6

Calloway v. Farley, 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1121............... 8

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 ...............9,10,12,13

Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp., 337 U. S.

541 ...................................................................................... 5,6

Connell v. Dulien Steel Products, 240 F. 2d 414 (5th

Cir. 1957) .......................................................................... 5

De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 ................................... 9

Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294 F.

2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961), cert. den. 368 U. S. 930 ....8,14,15

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 299 .......................9,10

Enelow v. New York Life Ins. Co., 293 U. S. 379 ........... 6

Ettelson v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 317 U. S. 188 6

Fields y . South Carolina,------ U. S . ------- , 11 L. ed. 2d

107 ...................................................................................... 9,10

Forgay v. Conrad, 6 How. (47 U. S.) 201....... ............... 4, 5

General Electric Co. v. Marvel Rare Metals Co., 287

U. S. 430 ............................................................................ 6

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652 ................................... 9

PAGE

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 U. S. 496 .10,12,13

Kennedy v. Lynd, 306 F. 2d 222 (5th Cir. 1962) ........... 5

Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp. 174

(M. D. Tenn. 1961) — ............................................. 8,14,15

Kunz v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 ..................................... 12

Largent v. Texas, 318 IT. S. 418 .......................-............ 12,13

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 .......................................... 12

Maxwell v. Enterprise Wall Paper Mfg. Co., 131 F. 2d

400 (3rd Cir. 1942) .......................................................... 6

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 ....................................... 10

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268 ............................... 12

Poulos v. New Hampshire, 345 U. S. 395 ......................... 13

King v. Spina, 166 F. 2d 546 (2nd Cir. 1948) ................. 6

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 .....................................12,13

Schneider v. Irvington, 308 U. S. 147 ...........................12,13

Sears, Roebuck and Company v. Mackey, 351 U. S. 427 5

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 ....................................... 15

Slochower v. Board of Education, 350 U. S. 551........... 15

Stack v. Boyle, 342 U. S. 1 ................................................ 5

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313.......................................... 12

Stromberg v. California, 283 IT. S. 359 ...........................9,13

Swan v. Board of Education of the City of New York,

unreported (S. D. N. Y. September 10, 1962) aff’d

319 F. 2d 56 (2nd Cir. 1963) ....... ........................ - .... 8

Swift and Co. v. Compania Colombiana, 339 U. S. 684 5

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 IT. S. 1 ....... ........................... 10

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516..... ............. -......... -10,12,13

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 IT. S. 8 8 ................................... 10

Ill

PAGE

IV

United Public Workers of America v. Mitchell, 330

U. S. 7 5 .............................................................................. 15

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961) 5

PAGE

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 ...............................

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183...............................

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 .................................

Woods v. Wright, ------ F. 2d ------ (5th Cir. May 22,

1963) ..................................................................................

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284.......................................

9

15

13

5

13

I n th e

Ituteii ©Hurt nf Appeals

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 20875

L inda Cal W oods, a minor, by her father and

next friend, Rev. Calvin Woods,

Appellant,

Theo R. W eight, Superintendent of Schools of the

City of Birmingham, Alabama,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOE THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from the denial by the district court

of appellant’s motion for a temporary restraining order

and/or preliminary injunction enjoining the appellee

Superintendent of Schools from suspending or expelling

the minor appellant and others similarly situated from the

public schools of Birmingham, Alabama because they had

been arrested for parading without a permit. This case

has been here before on appellant’s motion for an injunc

tion pending appeal which was granted on May 22, 1963.

The minor appellant, an eleven year old Negro girl and

fifth grade student, was summarily suspended from a Bir

2

mingham public school pursuant to a direction by appellee

dated May 20, 1963 (R. 9, 10). Appellee acted after a vote

of the Board of Education of the City of Birmingham

(R. 9, 10). She was one of approximately 1,080 Negro

students expelled or suspended because they had been

arrested “ for parading without a permit” (R. 9). No

hearings were held or set to determine the propriety of

the dismissals. The students were simply told that not

enough time remained in the school term, to hold any hear

ings (R. 10).

The directive of May 20 permitted the students to make

up the time lost by attending summer school which began

June 3, 1963 (R. 10), the cost of which was approximately

$24.00 plus additional expenses of travel, etc. (R. 20). If

they did not attend summer school, they could re-enter

school in the fall but would have “ to complete the full

grade or semester from which they were suspended or

expelled” (R. 10).

The appellant, Linda Cal Woods, was suspended be

cause she had been arrested for parading without a license,

on Saturday, May 4, 1963, a non-school day, while peace

fully participating in a protest against racial segregation.

At the time of her arrest, she was walking on the sidewalk

with her two sisters and several other persons, about ten

in number, two abreast. She was carrying a sign which

read, “ Segregation is Unconstitutional!” She and her

companions were at all times peaceful and had been given

instructions by her father to remain so at all times when

he gave her permission to participate.

On May 21, 1963, appellant, by her father and next

friend, filed a complaint and a motion for temporary

restraining order and/or preliminary injunction enjoin

ing the appellee from carrying into effect the suspension

3

or expulsion of the Negro students, refusing to expunge

any notation of the dismissals from their records, or pe

nalizing the members of the class in any other way (R. 7).

On the same day, a hearing was held before Judge Allgood

on the motion for a temporary restraining order. The

appellee and Board of Education of the City of Birming

ham had been notified and were represented. No court

reporter was present. Judge Allgood refused (though not

formally) to issue the temporary restraining order and

set another hearing for the following day. On May 22,

1963 a further hearing was held, seemingly on the motion

for a preliminary injunction. Again, both sides were rep

resented but no court reporter was present. The district

court denied relief on the same day (R. 21).

On May 22, 1963, appellant filed two notices of appeal,

one appealing from the denial of the temporary restrain

ing order and the other appealing from the denial of the

preliminary injunction. Following the filing of these

notices, Judge Allgood amended his order to provide that

appellant’s motion for a preliminary injunction would be

taken under consideration by the court and a. date for the

hearing would be set (R. 24, 26, 27). No date has ever

been set for this hearing.

Appellant, upon filing notice of appeal, moved in this

Court for an injunction pending appeal. On May 22, 1963

Chief Judge Elbert P. Tuttle issued such an injunction

requiring the reinstatement of the minor appellant and all

other Negro children similarly situated.

On December 4, 1963 time for filing this brief was ex

tended until January 26, 1964.

4

Specification of Errors

The District Court erred in:

(1) refusing a temporary restraining order and pre

liminary injunction enjoining the appellee and others from

suspending or expelling the appellant and all others simi

larly situated and from refusing to expunge any and all

notations of the dismissals from their permanent records,

(2) refusing to enjoin the imposition of any other penal

ties or disciplinary action against the appellant and others

similarly situated for participating in peaceful racial pro

tests,

(3) refusing to hold that the suspension and expulsion

of the Negro students was in violation of said students’

First Amendment rights,

all of which was contrary to the due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.

ARGUMENT

I

The Order of the District Court Is an Appealable

Order Both Under Section 1291 and Section 1292

(a) (1 ) of Title 28 , United States Code.

Section 1291 of Title 28, United States Code gives the

Courts of Appeals “ jurisdiction of appeals from all final

decisions of the district courts of the United States.” In

determining what constitutes a “ final” decision, Section

1291 has long been given a practical rather than technical

construction. Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U. S.

294, 306; For gay v. Conrad, 6 How. (47 U. S.) 201, 202;

5

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772, 778 (5th Cir. 1961);

Baltimore and Ohio R.R. Co. v. United Fuel Gas Co., 154 F.

2d 545, 546 (4th Cir. 1946). Although the denial of a tem

porary restraining order is ordinarily not appealable, see

Connell v. Dulien Steel Products, 240 F. 2d 414 (5th Cir.

1957), and assuming that the district court’s order was

such a denial,1 this case falls within the rule of United

States v. Wood, supra at 778 that an appeal may be taken

from a temporary restraining order “ determining substan

tial rights of the parties which will be irreparably lost if

review is delayed until final judgment. . . . ” 2 * * * 6

The order of the district court is also appealable under

§1292(a)(l) of Title 28, United States Code. That section

permits appeals from “ Interlocutory orders of the district

courts of the United States . . . granting, continuing, modi

fying, refusing or dissolving injunctions, or refusing to

dissolve or modify injunctions . . . ” In determining what

orders are “ interlocutory” for purposes of §1292(a)(l),

1 The original order of the district court denied the motion for

a temporary restraining order but did not refer to a preliminary

injunction in any way. After two notices of appeal were filed,

one from the denial of a restraining order and one from the denial

of a preliminary injunction, the original order of the district

court was amended to say that the motion for a preliminary in

junction would be heard at a later date (R. 24, 26, 27).

2 Other decisions have permitted appeals from orders not tech

nically final where irreparable harm wrould render worthless a

delayed appeal. Woods v. W right------ F. 2 d -------- (5th Cir. May

22, 1963) ; Stack v. Boyle, 342 U. S. 1, appeal possible from denial

of motion to reduce bail; Swift and Co. v. Compania Colombia.na,

339 U. S. 684, appeal from an order vacating the attachment of a

ship in a libel action for lost cargo; Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial

Loan Corp., 337 U. S. 541, appeal from the denial of a request to

require the plaintiff to give security for reasonable expenses and

counsel fees in a stockholder’s derivative action. See also Sears,

Roebuck and Company v. Mackey, 351 U. S. 427; For gay v. Conrad,

6 How. (47 U. S.) 201; Kennedy v. Lynd, 306 F. 2d 222 (5th Cir.

1962).

6

courts look not to the terminology used but to “ the sub

stantial effect of the order made.” Ettelson v. Metropoli

tan Life Ins. Co., 317 U. S. 188; Enelow v. New York Life

Ins. Co., 293 U. S. 379; General Electric Co. v. Marvel Rare

Metals Co., 287 U. 8. 430; Ring v. Spina, 166 F. 2d 546 (2nd

Cir. 1948). Orders which “have a final and irreparable

effect on the rights of the parties,” Cohen v. Beneficial In

dustrial Loan Corp., supra at 545, or are of “ serious, per

haps irreparable consequence,” Baltimore Contractors v.

Bodinger, 348 U. S. 176, 181 or are “ effective upon . . .

rendition and . . . drastic and far reaching in effect,”

Maxwell v. Enterprise Wall Paper Mfg. Co., 131 F. 2d 400,

402 (3rd Cir. 1942), are appealable under §1292(a)(1).

There can be no real dispute that the appellant and

others similarly situated suffered irreparable harm as the

result of suspensions and expulsions pursuant to the direc

tive of the appellee. Graduation for many students was

prevented. A school semester for all was destroyed. In

addition, given the short time remaining in the semester,

no further effective court proceedings were possible—be

yond, of course, what occurred. The issues would have

become moot and ousted this court from jurisdiction.

Though the time lost could be made up in summer school,

this was only at a substantial cost to the persons involved.

The fact of suspension or expulsion became a part of the

students’ permanent records to be sent to any potential

schools or employers.

Moreover, in addition to the appealability of the district

court’s, order because of irreparable harm, the order is

appealable under §1292(a)(l) because it, in effect, denies

the relief requested in the suit. This test, of the denial,

in effect, of requested injunctive relief, was applied in

Brunson v. Board of Trustees of School District No. 1, 311

F. 2d 107 (4th Cir. 1962). There, forty-two Negro children

7

brought a class action to desegregate the schools of Claren

don County, South Carolina. Upon motion, the district

court issued an order striking all plaintiffs other than the

first named, Bobby Brunson, and all allegations appropri

ate to a class action from the complaint. Brunson was

given twenty days to file an amended complaint consistent

with the court’s order. A few days after this order, Brun

son graduated, making the issues moot as to him. He could

not file a new complaint, have a trial, and obtain a decision

on the merits. Nor could he contest the lower court’s order

striking the other plaintiffs in an appeal after a trial on the

merits. The other Negro plaintiffs were left to individual

actions and relief. Since they were in effect denied the

injunctive relief requested for the reorganization of the

entire school system, appeal was permitted under §1292

(a )(1 ). Similarly, in this case, the appellant and other

Negro students sought relief from the loss of the semes

ter in school.

II

The Suspension and Expulsion o f the Negro Students

W ithout Notice or Hearing Violated Rights Secured by

the Due Process Clause o f the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution o f the United States.

At school on May 20, 1963, appellant Linda Cal Woods

was handed a letter suspending her for the balance of the

semester (R. 5). In similar manner, without notice or an

opportunity to be heard, approximately 1,080 other Negro

students were dismissed from public schools in Birming

ham, Alabama (R. 5,9,10,12, 20). This procedure flagrantly

disregarded not only previous cases directly in point but

constitutional principles deeply rooted in the traditions

of our country.

8

In Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, 294

F. 2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961), cert, denied 368 U. S. 930, this

court condemned the expulsion of several Negro students

from a tax-supported college without the constitutional

safeguards of notice and hearing. Though the “miscon

duct” for which the students had been expelled was never

definitely specified, all of them had participated in a

peaceful protest against racial segregation of a lunch grill

in the basement of the Montgomery County Courthouse.

In reversing, this court held (at p. 157):

In the disciplining of college students there are

no considerations of immediate danger to the public,

or of peril to the national security, which should pre

vent the Board from exercising at least the funda

mental principles of fairness by giving the accused

students notice of the charges and an opportunity to

be heard in their own defense. Indeed, the example

set by the Board in failing so to do, if not corrected

by the courts, can well break the spirits of the ex

pelled students and of others familiar with the injus

tice, and do inestimable harm to their education.

See also Knight v. State Board of Education, 200 F. Supp.

174 (M. D. Tenn. 1961). Thirteen Negro students had

been arrested as “ Freedom Riders” in Jackson, Missis

sippi. The Court relied on the Dixon case. See also Swan

v. Board of Education of the City of New York (S. D.

N. T. September 10, 1962), aff’d 319 F. 2d 56 (2nd Cir.

1963), citing with approval the Dixon case but dismissing

the complaint on the grounds that the statute of limitations

had run, and Calloway v. Farley, 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1121

(E. D. Va. 1957) in which a temporary restraining order

was obtained enjoining the imminent expulsion of Negro

students from public schools in Richmond, Virginia.

9

Appellee’s Directive Is a Restraint on the Liberty of

Expression Guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth

Amendments.

The loss of an education is not the sole consequence

of the suspension and expulsion of the students. Of equal

importance is the detrimental effect on the exercise of

freedoms secured by the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments. It has long been established that these First

Amendment freedoms are protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment from invasion by the states. Edwards v.

South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229; Fields v. South Carolina,

—— XJ. S .----- , 11 L. Ed. 2d 107; Cantwell v. Connecticut,

310 U. S. 296; DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 IT. S. 353; Stro'tn-

berg v. California, 283 U. 8. 359; Whitney v. California,

274 U. S. 357; and Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652.

The activity in which the appellant was engaged is closely

akin to the activity of Negro students in Edwards. There

187 Negro students had engaged in an orderly protest

against racial segregation by marching to and through

the South Carolina state house grounds in Columbia,

South Carolina. The Supreme Court of the United States

reversed convictions for breach of the peace stating that

their actions represented an exercise of First Amend

ment freedoms “ in their most pristine and classic form.”

Edwards v. South Carolina, supra, at 235.

Here the appellant, with the permission of her father, en

gaged in an orderly demonstration against racial segrega

tion by walking two abreast on the sidewalk with her two

sisters and several other persons. Like the Negro students

in Edwards she was exercising First Amendment rights “ in

their most pristine and classic form.” In the past, the pro

III

10

tection of First Amendment freedoms has been regarded

as so precious that they could only be abridged by the

state upon a showing that a compelling state interest

demanded it. Edwards v. South Carolina, supra; Fields v.

South Carolina, supra; Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516;

Cantwell v. Connecticut, supra; Thornhill v. Alabama, 310

U. S. 88; Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. 8. 496; Near v. Minne

sota, 283 U. S. 697. No compelling interest on the part of

the state or on the part of the school officials has been

shown. The record is completely devoid of evidence of

disorder or violence of any kind.

It is of no consequence that the action and the beliefs

of the appellant were controversial in the area where she

lived. As stated in Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, 4:

“ [A] function of free speech under our system of gov

ernment is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve

its high purpose when it produces a condition of un

rest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they

are, or even stirs people to anger. Speech is often pro

vocative and challenging. It may strike at prejudices

and preconceptions and have profound unsettling ef

fects as it presses for acceptance of an idea. That is

why freedom of speech . . . is . . . protected against

censorship or punishment, unless shown likely to pro

duce a clear and present danger of a serious substan

tive evil that rises far above public inconvenience,

annonyance, or unrest. . . There is no room under our

Constitution for a more restrictive view.

11

IV

Appellant’ s Suspension Is a Denial of Due Process

Because It Results From an Alleged Violation of an

Unconstitutional Ordinance.

Aside from the constitutional deprivations resulting

from lack of notice or hearing for actions protected by the

First and Fourteenth Amendments, appellee’s directive

inflicts additional punishment for an alleged but unproved

violation of an ordinance unconstitutional on its face and

as applied. Section 1159 of the Birmingham Code, the

ordinance the students were charged with violating, reads

as follows:

Section 1159. P arading.

It shall be unlawful to organize or hold, or to assist

in organizing or holding, or to take part or participate

in, any parade or procession or other public demon

stration on the streets or other public ways of the city,

unless a permit therefor has been secured from the

commission.

To secure such permit, written application shall be

made to the commission, setting forth the probable

number of persons, vehicles and animals which will be

engaged in such parade, procession or other public

demonstration, the purpose for which it is to be held or

had, and the streets or other public ways over, along

or in which it is desired to have or hold such parade,

procession or other public demonstration. The com

mission shall grant a written permit for such parade,

procession or other public demonstration, prescribing

the streets or other public ways which may be used

therefor unless in its judgment the public welfare,

peace, safety, health, decency, good order, morals or

12

convenience require that it be refused. It shall be un

lawful to use for such purposes any other streets or

public ways than those set out in said permit.

The two preceding paragraphs, however, shall not

apply to funeral processions.

The use of Section 1159 against the appellant here con

flicts with a long line of Supreme Court decisions holding

such ordinances unconstitutional as a prior restraint on

free expression because they set no standards for a grant

of a permit, but leave this determination to the unfettered

will of a public official. See Staub v. Baxley, 355 U. S. 313

(permit from Mayor required of certain organizations be

fore soliciting members); Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S.

268 (permit from Park Commissioner required for public

meeting); Runs v. New York, 340 U. S. 290 (permit from

police commissioner required for religious assembly on a

public street); Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 (prohibit

ing sound trucks on the streets without a license from the

chief of police); Thomas v. Collins, 323 IT. S. 516 (requir

ing permit from the Secretary of State before a union

organizer could carry on activities in the State of Texas);

Largent v. Texas, 318 U. S. 418 (requiring permit from the

Mayor to canvass); Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296

(requiring permit from the secretary of the public welfare

council to disseminate religious propaganda); Schneider v.

Irvington, 308 U. S. 147 (permit from police chief required

of canvasser); Hague v. C. I. O., 307 IT. S. 496 (permit

from the Director of Public Safety required for public

assembly); and Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (permit

from the City Manager required to distribute pamphlets).

Section 1159 leaves to the commission not only a determi

nation of what constitutes a “ parade” but also of actions

injurious to the “ public welfare, peace, safety, health, de

cency, good order, morals or convenience.” These words

13

are similar to those used in ordinances in the cited cases

and held to be insufficient checks on the discretion of public

officials. Thus permits could be refused to prevent “ annoy

ance or inconvenience,” Saia, supra at 558; if deemed

“ proper or advisable,” Largent, supra at 419; for lack of

“ reasonable standards of efficiency and integrity,” Cant

well, supra at 302; for lack of “good character,” Schneider,

supra at 157; and to prevent “ riots, disturbances or dis

orderly assemblage,” Hague, supra at 504.

Poulos v. New Hampshire, 345 U. S. 395 offers no sup

port for the constitutionality of Section 1159. Although

that case upheld a conviction for violation of an ordinance

requiring a permit for use of a park, the New Hampshire

courts had construed the ordinance to allow no discretion

to the public official to refuse a permit, but only to consider

such things as the time, place, and manner of holding the

assembly.

Section 1159 is equally unconstitutional as applied to the

conduct of these students. By failing to specifically define

such things as “ parade” or acts endangering the “ public

welfare” it falls within the rule that “ a generally worded

statute which is construed to punish conduct which cannot

constitutionally be punished is unconstitutionally vague to

the extent that it fails to give adequate warning of the

boundary between the constitutionally permissible and con

stitutionally unpermissible applications of the statute.”

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284, 10 L. Ed. 2d 349, 355;

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507; .Stromberg v. Cali

fornia, supra.

Since"'§1159 is unconstitutional, there was no obligation

on the part of appellant or the other Negro students to

obey it. Thomas v. Collins, supra; Largent v. Texas, supra.

Because appellee’s directive only compounded the injury

14

received from the arrest pursuant to the ordinance, it also

runs counter to the dictates of due process.

It is no answer to the grave denials of due process to

say that a school or university must possess wide latitude

in disciplining its students. Both the Dixon and Knight

cases conceded this, but replied that such power was “ not

unlimited and cannot be arbitrarily exercised.” Dixon,

supra at 157. In Knight the court added (at p. 179):

It may be conceded that a state college or university

must necessarily possess a very wide latitude in dis

ciplining its students and that this power should not

be encumbered with restrictions which would embar

rass the institution in maintaining good order and

discipline among members of the student body and a

proper relationship between the students and the

school itself. It may further be conceded that it is a

delicate matter for a court to interfere with the in

ternal affairs and operations of a college or university,

whether private or public, and that such interference

should not occur in the absence of the most compelling

reasons.

Nevertheless, the authorities uniformly recognize

that the governmental power in respect to matters of

student discipline in public schools is not unlimited

and that disciplinary rules must not only be fair and

reasonable but that they must be applied in a fair and

reasonable manner. Dixon v. Alabama State Board

of Education, supra, 294 F. 2d at page 157.

Nor can due process deprivations be justified by the

argument that attendance at a public school is a privilege

and not a right. Even the grant of a privilege cannot be

conditioned upon the relinquishment of the constitutional

rights to notice and hearing, exercise of free speech, and

15

punishment only for violation of valid statutes. Shelton

v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479; Slochower v. Board of Educa

tion, 350 U. S. 551; Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183;

United Public Workers of America v. Mitchell, 330 U. S.

75; Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education, supra;

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F. 2d 993

(4th Cir. 1940), eert. denied 311 U. S. 693; Knight v. State

Board of Education, supra.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the judgment of the dis

trict court should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Constance Baker Motley

George B. Smith

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

A rthur D. Shores

1527 North 5th Avenue

Birmingham, Alabama

Orzell B illingsley, Jr.

1630 North 4th Avenue

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Appellant

L eroy D. Clark

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Birmingham Code

Section 1159. Parading.

It shall be unlawful to organize or hold, or to assist in

organizing or holding, or to take part or participate in,

any parade or procession or other public demonstration

on the streets or other public ways of the city, unless a

permit therefor has been secured from the commission.

To secure such permit, written application shall be made

to the commission, setting forth the probable number of

persons, vehicles and animals which will be engaged in

such parade, procession or other public demonstration, the

purpose for which it is to be held or had, and the streets or

other public ways over, along or in which it is desired to

have or hold such parade, procession or other public

demonstration. The commission shall grant a written per

mit for such parade, procession or other public demon

stration, prescribing the streets or other public ways which

may be used therefor unless in its judgment the public

welfare, peace, safety, health, decency, good order, morals

or convenience require that it be refused. It shall be un

lawful to use for such purposes any other streets or public

ways than those set out in said permit.

The two preceding paragraphs, however, shall not apply

to funeral processions.

2 a

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that on th e .........day of January, 1964,

I served a copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellant upon

Reid B. Barnes, Attorney for Appellee, Exchange Security

Bank Building, Birmingham, Alabama, by depositing a

copy thereof addressed to him as indicated herein in the

United States mail, airmail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellant

3 8