Petition for Writ of Certiorari Motion for Leave and Brief Amici

Public Court Documents

20 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Petition for Writ of Certiorari Motion for Leave and Brief Amici, 0c80d675-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/dff0b59b-98e5-4fea-92eb-d43f7da6cf8e/petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-motion-for-leave-and-brief-amici. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

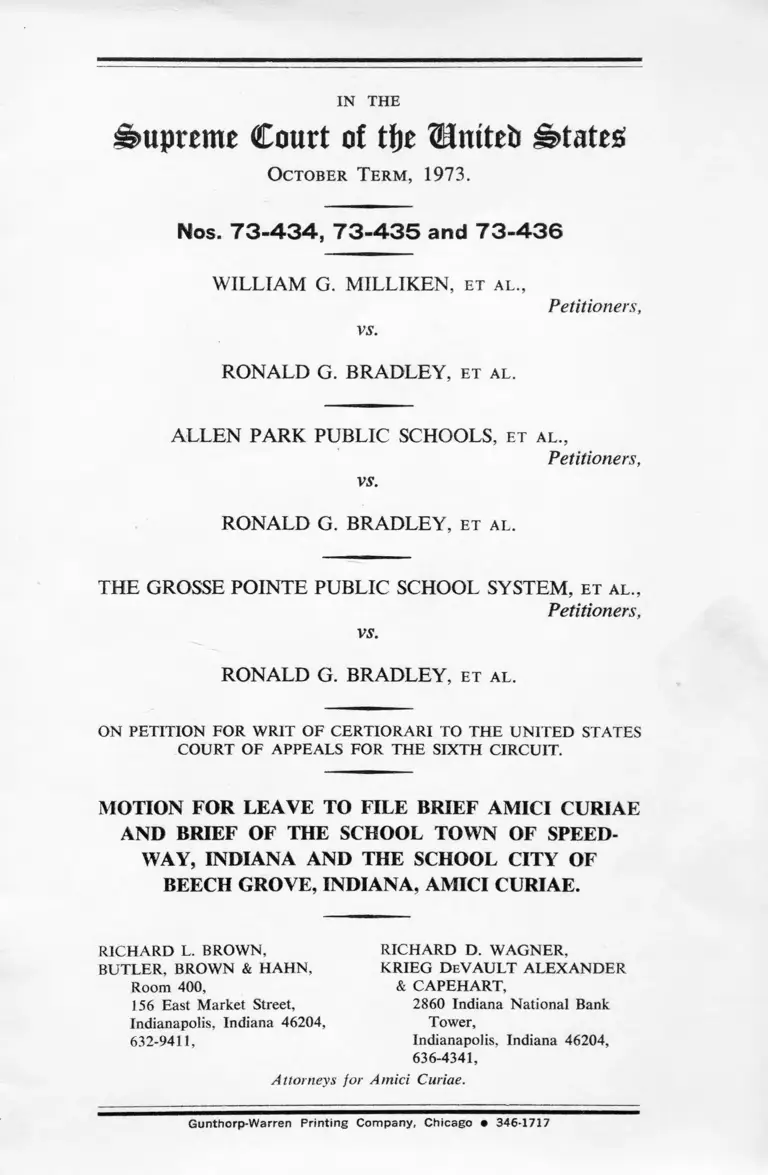

IN THE

Supreme Court ot tfje Uniteb States:

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1973.

Nos. 73-434, 73-435 and 73-436

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, e t a l .,

vs.

Petitioners,

RONALD G. BRADLEY, e t a l .

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, e t a l .,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, e t a l .

THE GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM, e t a l .,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, e t a l .

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICI CURIAE

AND BRIEF OF THE SCHOOL TOWN OF SPEED

WAY, INDIANA AND THE SCHOOL CITY OF

BEECH GROVE, INDIANA, AMICI CURIAE.

RICHARD L. BROWN,

BUTLER, BROWN & HAHN,

Room 400,

156 East Market Street,

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204,

632-9411,

RICHARD D. WAGNER,

KRIEG D eVAULT ALEXANDER

& CAPEHART,

2860 Indiana National Bank

Tower,

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204,

636-4341,

Attorneys for Amici Curiae.

Gunthorp-Warren Printing Company, Chicago • 346-1717

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfje Mntteb States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1 9 7 3 .

Nos. 73-434, 73-435 and 73-436

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, e t a l .,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, e t a l .

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, e t a l .,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, e t a l .

THE GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM, e t a l .,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, e t a l .

ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AMICI CURIAE.

2

The School Town of Speedway, Indiana and The School City

of Beech Grove, Indiana hereby respectfully move for leave to

file the attached Brief Amici Curiae in these cases. All attorneys

for the parties in these appeals have been contacted and their

consent requested to file such Brief. Some of such attorneys

have given such consent, but movants have been unable to ob

tain same from all such attorneys.

The interest of The School Town of Speedway, Indiana and

The School City of Beech Grove, Indiana, arises from the follow

ing facts. Both movants are school corporations created and

existing under Indiana law. They own and operate school sys

tems, which serve, respectively, the civil town of Speedway and

the civil city of Beech Grove, Indiana, two small Communities

adjacent to the City of Indianapolis.

On August 18, 1971, the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Indiana, after a trial of an action brought

by the United States, entered a judgment in which it found that

the Indianapolis Public School System (IPS) was guilty of seg-

regatory practices in the operation of its schools.1 The trial

court speculated in its opinion that a desegregation plan limited

to IPS would not remain demographically stable and that IPS

would at some future point have enrolled a higher percentage

of black students than was acceptable to the district court.

Subsequently an intervening complaint was filed and nineteen

school corporations and certain state officials added as defend

ants. Movants were among the added school corporations.

Following another trial, the court entered a judgment in which

it found, inter alia: (1) that the prior judgment against IPS

was res judicata against the added school corporations, and state

officials; (2) that none of the added school corporations were

guilty of segregatory practices; and (3) that all of the school

corporation defendants were amenable to orders effecting stu

dent transfers between such defendants in quantities designed

1. U. S. v. Bd. of School Commissioners, 332 F. Supp. 655,

aff’d., 474 F. 2d 81 (7th Cir. 1973), cert. den. 37 L. Ed. 2d

1041 (1973).

3

to achieve a prescribed degree of racial balance within IPS.

That decision is presently on appeal to the United States Court

of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.2 Thus, movants are in

volved in an action similar to the case at bar. A decision by

this Court in the instant action may provide precedent for the

Seventh Circuit’s decision.

Both the School Town of Speedway, Indiana and The School

City of Beech Grove, Indiana are independent school corpora

tions which have territorial boundaries coterminous with the

municipalities which they serve. As such entities, they have com

munity interests distinct and separate from other types of school

corporations which will be adversely affected if this Court ap

proves the power of district courts to enter orders such as those

made in the cases at bar. The distinct interests of school corpora

tions serving towns and cities has not heretofore been argued by

the parties in this appeal or considered in the Court of Appeals

below, and such interests are relevant to any disposition of this

appeal. Movants do not believe that the arguments made in the

attached Brief will be made by any other party to these appeals.

Respectfully submitted,

/ s / RICHARD L. BROWN,

BUTLER, BROWN & HAHN,

Room 400,

156 East Market Street,

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204,

632-9411,

RICHARD D. WAGNER,

KRIEG D eVAULT ALEXANDER

& CAPEHART,

2860 Indiana National Bank

Tower,

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204,

636-4341,

Attorneys for The School Town of Speedway, Indiana, and The School City

of Beech Grove, Indiana.

2. United. States, Plaintiff-Appellant and Donny Brurell Buckley,

et al., Intervening Plaintiffs-Appellees v. Board of School Com

missioners, et al., Nos. 73-1968 through 73-1984, in the Seventh

Circuit Court of Appeals.

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfje Urntrb States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1973.

Nos. 73-434, 73-435 and 73-436.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, e t a l .,

vs.

Petitioners,

RONALD G. BRADLEY, e t a l .

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, e t a l .,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, e t a l .

THE GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM, e t a l .,

vs.

Petitioners,

RONALD G. BRADLEY, e t a l .

ON p e t it i o n f o r w r it o f c e r t io r a r i t o t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s

c o u r t o f a p p e a l s f o r t h e s i x t h c i r c u i t .

BRIEF OF THE SCHOOL TOWN OF SPEEDWAY,

INDIANA AND THE SCHOOL CITY OF

BEECH GROVE, INDIANA,

AMICI CURIAE.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

------------- PAGE

Table of Authorities . ......................................................... i

Interest of Amici C u ria e ....................................................... 1

Argument ............................................................................... 2

Conclusion................................................................. 7

T a b l e o f A u t h o r it ie s .

Cases.

Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Ed., 369 F. 2d 55 (6th Cir.

1966), cert, den., 389 U. S. 847 (1967 )........................ 4

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U .S. 339 (1960 ).................. 5

Hunter v. Pittsburgh, 207 U. S. 161 (1907)...................... 5

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, ........

U. S.......... , 37 L. Ed. 2d 548 (1973)............................. 4

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 (1925 )........... 5

Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (D. N. J. 1971),

aff’d. per curiam, 404 U. S. 1027 (1972 )......................... 5

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 402 U. S. 1

(1971) .......................................................................... 5

United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellant, and Donny

Brurell Buckley, et al., Intervening Plaintiffs-Appellees

v. Bd. of School Commissioners, et al., Nos. 73-1968

through 73-1984, in the U. S. Court of Appeals, Seventh

Circuit ................................................................................. 2

U. S. v. Bd. of School Commissioners, 332 F. Supp. 655,

aff’d., 474 F. 2d 81 (7th Cir. 1973), cert. den. 37 L.

Ed. 2d 1041 (1973) ............................................................ 1

11

Statutes and State Constitution.

Bums Ind. Stat. § 28-2603 ................................................... 6

Indiana Constitution, Art. 2, § 2 .......................................... 6

Other.

P. Smith, As a City Upon a Hill, The Town in American

History (Alfred A. Knopf, 1 9 6 6 ) ................................. 2, 4, 7

U. S. Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Vol. 1,

Governmental Organization, 1972 Census of Govern

ments .................................................................................... 2

Will Herberg, Ed.: The Writings of Martin Buber (New

York: Meridian Books; 1956) ........................................ 4

1

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE.

The interest of The School Town of Speedway, Indiana and

The School City of Beech Grove, Indiana, arises from the

following facts. Both movants are school corporations created

and existing under Indiana law. They own and operate school

systems which serve, respectively, the civil town of Speedway

and the civil city of Beech Grove, Indiana, two small com

munities adjacent to the City of Indianapolis.

On August 18, 1971, the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Indiana, entered a judgment in which

it found that the Indianapolis Public School System (IPS) was

guilty of segregatory practices in the operation of its schools.1

The trial court speculated in its opinion that a desegregation

plan limited to IPS would not remain demographically stable

and that IPS would at some future point have enrolled a higher

percentage of black students than was acceptable to the district

court.

Subsequently an intervening complaint was filed and nine

teen school corporations and certain state officials added as

defendants. Movants were among the added school corpora

tions. Following another trial, the court entered a judgment in

which it found, inter alia: (1) that the prior judgment against

IPS was res judicata against the added school corporations and

state officials; (2) that none of the added school corporations

were guilty of segregatory practices; and (3) that all of the

school corporation defendants were amenable to orders effect

ing student transfers between such defendants in quantities

designed to achieve a prescribed degree of racial balance within

IPS. That decision is presently on appeal to the United States

1. U. S. v. Bd. of School Commissioners, 332 F. Supp. 655,

aff’d., 474 F. 2d 81 (7th Cir. 1973), cert. den. 37 L. Ed. 2d

1041 (1973).

2

Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit.2 3 Thus, movants are

involved in an action similar to the case at bar. A decision by

this Court in the instant action may provide precedent for the

Seventh Circuit’s decision.

ARGUMENT.

"It is not the time to try to say with final authority

what the town has meant in American life. Its mean

ings are profound and various. But of its importance

there can be no question.”*

One of the questions in the case at bar and in the action in

which these amici are parties is whether a federal district court

may order the busing of school students between separate, in

dependent school corporations in order to remedy discriminatory

practices found to exist in only one of such school corpora

tions. These amici believe that the far reaching impact of such

an order may be seen in clearer detail when viewed from the

vantage point of a school corporation which serves a city or

town separate and distinct from the school district in which

such discriminatory practices were effected.

Throughout this country, hundreds of school corporations

exist which have geographical boundaries coextensive with small

towns and cities.4 Several of such school corporations are

2. United States, Plaintiff-Appellant and Donny Brurell Buckley,

et al., Intervening Plaintiffs-Appellees v. Board of School Com

missioners, et al., Nos. 73-1968 through 73-1984, in the Seventh

Circuit Court of Appeals.

3. P. Smith, As a City Upon a Hill, The Town in American

History (Alfred A. Knopf, 1966), p. 307.

4. In 1972, the U. S. Bureau of the Census reported the

existence in the United States of 15,281 “independent school dis

tricts,” i.e., school districts which are administratively and fiscally

independent of any other government. Of this number, 597 of

such districts had coterminous “citywide” boundaries. The same

source reported a total of 1457 “dependent school districts” of which

247 had coterminous “citywide” boundaries. In total, there were,

in 1972, 844 “citywide” systems with 8.2 million pupils. U. S.

Dept, of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Vol. 1, Governmental

Organization, 1972 Census of Governments, pp. 3, 6, 8 and 40.

3

parties to these appeals. These amici are also school corpora

tions which have such territorial boundaries and which serve

small municipalities located in the State of Indiana.

Typical of such municipal school corporations is one of

these amici, The School Town of Speedway. The civil town of

Speedway, Indiana, which it serves, has a population of approxi

mately 17,500. The town is governed by a board of trustees

elected by the citizens of the town. The town board is em

powered to control all other municipal departments and ap

points their administrators. Schools which serve the com

munity are owned and administered by an independent corpora

tion created by statute and designated as The School Town of

Speedway. The administration of that school corporation is

vested in a three-man board of school trustees appointed by

the civil town board of trustees on a non-partisan basis. The

School Town of Speedway neither owns nor operates school

buses. All schools are physically located within the town

boundaries so that students have access thereto either by walk

ing or other means of transportation provided by the students

or their parents. The operational funds for the schools are

provided almost entirely through taxes paid by citizens of the

Town. Although this small community is geographically

dwarfed by the adjacent City of Indianapolis, it encompasses

large industries in which many of its citizens work. In short,

it is a distinct community whose citizens take pride in local

community projects and operations, and which has a municipal

government and school system responsive to the local problems

and needs of the community.

The rationale of state legislatures in fixing school boundaries

to the boundaries of the small towns and cities which they serve

is not limited to mere physical convenience:

[I]f we except the family and the church, the basic

form of social organization experienced by the vast major

ity of Americans up to the early decades of the 20th

Century was the small town. In the words of Thorstein

Veblen: “The country town is one of the great American

4

institutions; perhaps the greatest, in the sense that it has

and had and continues to have a greater part than any

other in shaping public sentiment and giving character to

American culture.”3

The real essence of a community is found in the fact that it

has a center, and the beginning of a community arrives when

its members have a common relation to the center.5 6 It is this

common relationship which gives vitality to a school system

serving the small community. The importance of this common

relationship becomes readily apparent when one views the chaos

of many big city school systems as contrasted to the stability

and quality of those found in smaller communities.

The small community, then, as many legislatures and educa

tors have found, provides a desirable environment for imple

mentation of a community-wide school system which can truly

give consideration to such important factors as home-school

communication, children attending school within the vicinity

of home, minimization of transportation safety hazards, economy

of cost and ease of pupil placement and administration. See

opinion of Mr. Justice Powell, concurring in part and dissent

ing in part, Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado,

........ U. S............, 37 L. Ed. 2d 548 (1973); Deal v. Cincinnati

Bd. of Ed., 369 F. 2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert, den., 389

U. S. 847 (1967).

It is thus beyond argument that towns and cities provide a

logical, reasonable and desirable setting for operation of in

dependent school corporations. The essential question is whether

federal courts can forcibly transfer children attending such a

school system, and otherwise disregard the independent nature

of such a system,7 in order to effect a judicially prescribed

degree of racial balance in a given geographical area.

5. P. Smith, supra, pp. vii-viii.

6. Will Herberg, Ed.: The Writings of Martin Buber (New

York: Meridian Books; 1956), p. 129.

7. In one of the district court orders entered in the case in

which these dmici were parties, the trial court has presumed the

power to consolidate all of the school corporations in the Indianapolis

Absent an overt, affirmative state act which contravenes a

Constitutionally protected right, federal courts have no power

to circumscribe the rights of the states to establish municipalities

and school corporations to serve the members of such com

munities. Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (D. N. J.

1971), aff’d. per curiam, 404 U. S. 1027 (1972); Gomillion v.

Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339 (1960); and Hunter v. Pittsburgh,

207 U. S. 161 (1907). These principles alone, in addition to

this Court’s rejection of the concept of “racial balance or mix

ing”, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 402 U. S.

1 at 24 (1971), provide sufficient authority for a reversal of

the lower courts in the instant case.

In an attempt to avoid the limitations found in the above

precedents and other cases, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals

in the cases at bar apparently adopted the theory that all school

corporations are agents of the state and since the state is

responsible for school matters, the rights of individual school

corporations could be ignored. Such a theory is flawed in many

respects. These amici wish to only point out that if this concept

is not rejected by this Court, it will allow one school corporation

to be held to answer for the wrongdoings of another. In ad

dition to the fact that guilt by association is anathema to our

jurisprudence, such a novel concept would effect a fundamental

deprivation of the Constitutional rights of the innocent school

corporation. Long ago this Court held that private corporations

created under state law for school purposes were entitled to the

protection afforded by the guarantees of the United States

Constitution. Pierce V. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 (1925).

No reason exists for holding that public school corporations

are to be treated differently.

Many other legal arguments could be discussed, but they will

undoubtedly be made by the parties to these appeals. It is the

area “along metropolitan lines”. Supplemental Memorandum of

Decision, entered December 6, 1973, by The U. S. District Court,

Southern District of Indiana, Cause No. IP 68-C-225, Slip Opinion,

p. 19.

5

6

practical and factual impact of the opinion of the Sixth Circuit

in the instant case which these amici wish to primarily empha

size. If that opinion is allowed to stand and becomes the law

of the land, judicial power in desegregation cases will know no

bounds. Students will be transported from the small towns and

cities in which they, their families and friends reside, into the

schools of large metropolitan areas. The burden of busing for

racial balance may fall upon school children who have always

walked to a nearby school (as is the case with most Speedway

students). Parental interest and participation in school affairs

will be frustrated. Many school officials are elected by voters

who reside within the territorial boundaries of the school cor

poration or district.8 Small town citizens may thus experience

the anomaly of being required to send their children to a school

system administered by officials over whom they exercise no

voting control. Every school corporation located in any degree

of proximity to a large metropolitan area will become amenable

to remedial racial balancing decrees, no matter how separate or

independent those school corporations may be. The touchstone

of judicial power will be demography, not equity.

8. This is the case for example, with respect to school officials

of the Indianapolis Public School System. See Indiana Constitution,

Art. 2, § 2; Burns Ind. Stats. § 28-2603. Thus in the case in which

these amici are parties, residents of Beech Grove and Speedway

cannot vote for Indianapolis school officials.

7

CONCLUSION.

The district courts involved in the cases with which this Brief

is concerned have promulgated decrees which eventually could

destroy one of the traditional fabrics of American life. Their

decrees formulate a blueprint for federally constituted school

systems which ignore the natural community interests of parents,

teachers and children. Our nation has drawn its life from small

communities, and it is itself a community of communities.9

This Court should not affirm a court decree which would forever

destroy the rights of the citizens of the towns and cities of this

nation to educate their children in school corporations designed

and established to serve individual communities.

Respectfully submitted,

RICHARD L. BROWN,

BUTLER, BROWN & HAHN,

Room 400,

156 East Market Street,

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204,

632-9411,

RICHARD D. WAGNER,

KRIEG D eVAULT ALEXANDER

& CAPEHART,

2860 Indiana National Bank

Tower,

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204,

636-4341,

Attorneys for The School Town of Speedway, Indiana, and The School City

of Beech Grove, Indiana.

9. P. Smith, supra, p. 14.

•‘r .