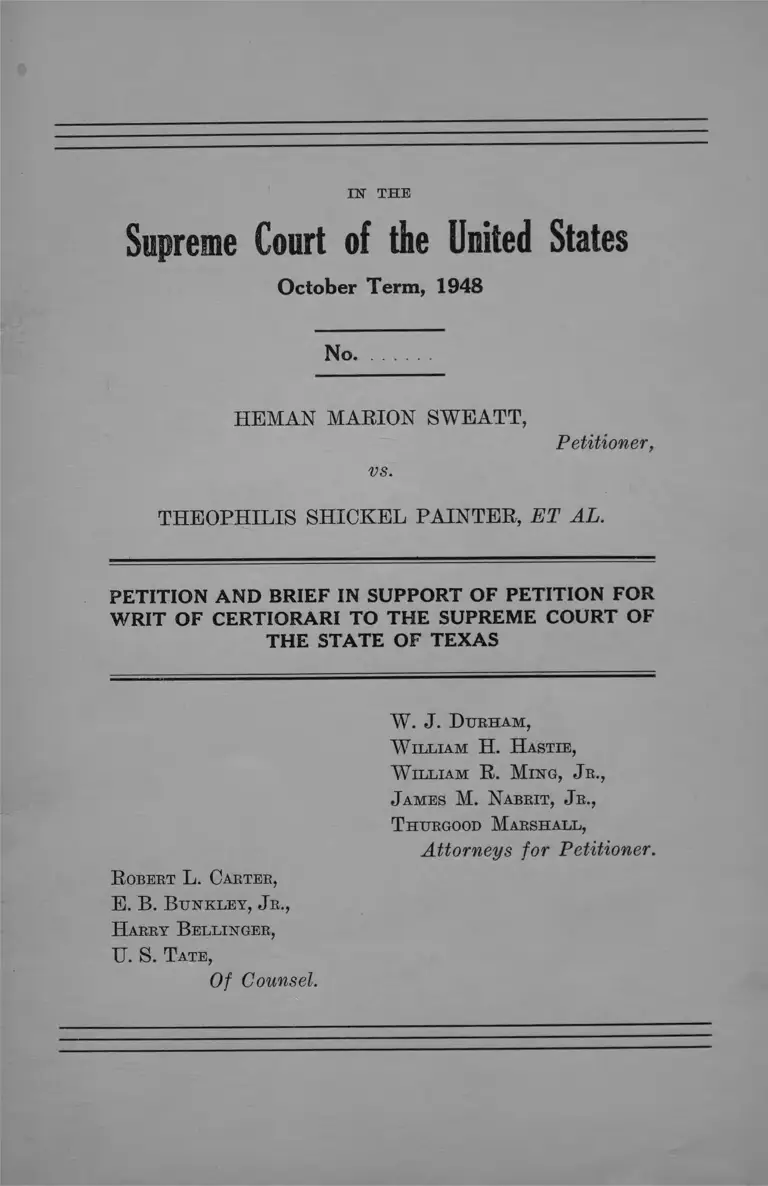

Sweatt v. Painter Petition and Brief in Support of Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sweatt v. Painter Petition and Brief in Support of Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1948. 26fa4f97-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e05a31d9-ce8e-44e1-8bf5-1ee99ef00588/sweatt-v-painter-petition-and-brief-in-support-of-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

IN' THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1948

No.

HEMAN MARION SWEATT,

vs.

Petitioner,

THEOPHILIS SHICKEL PAINTER, ET AL.

PETITION AND BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR

W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF

THE STATE OF TEXAS

W . J. D urham ,

W illiam H . H astie,

W illiam R . M ing , J r .,

J ames M. N abrit, J r .,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

R obert L. Carter,

E. B. B u n kley , Jr.,

H arry B ellinger,

U. S. T ate,

Of Counsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Petition por W rit op Certiorari

Part One— Summary Statement of the Matter In

volved __________________________________ 2

I. Statement of the Case ________________________ 2

First Hearing -___________________________ 3

Second H earing___________________________ 3

Hearing on the Merits ___________________ 3

II. Summary of Testimony ____________________ 5

A. The Two Law Schools __________________ 6

Physical Plant _________________________ 7

Library ____________________________ 7

Faculty _______________________________ 7

Student Body _________________________ 7

B. The Unreasonableness of C o m p u l s o r y

Racial Segregation in Public Legal Edu

cation ____________________________________ 9

C. Inequalities Inherent in Segregated School

Facilities ________________________________ 11

P art Two— Opinion of the Court B elow _____________ 12

Part T hree—Jurisdiction __________________________ 13

Part F our— Question Presented ___________________ 13

Part F ive—Reasons Relied Upon for Allowance of

the Writ _________________________________________ 13

Conclusion _________________________________________ 14

11

PAGE

B rief in S upport T hereof

Opinion of the Court Below _____________________ 15

Jurisdiction __ 15

Statement of the Case____________________________ 16

Errors Belied U pon______________________________ 16

A rgument

I. The question whether a state which undertakes

to provide legal education for any of its citi

zens can satisfy the requirements of the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment by establishing a law school for Negroes

separate from the law school it provides for all

other persons is of great public importance and

should be decided by this Court in this case 17

II. The inconsistency between the judicial approval

of laws imposing racial distinctions in Plessy

v. Ferguson and the judicial disapproval of

similar distinctions and classifications in more

recent decisions should lead this Court to re

view and disavow the doctrine of Plessy v.

Ferguson___________________________________ 23

III. This Court should review and reverse the judg

ment below to prevent the several states from

being free to restrict Negroes to public edu

cational facilities clearly inferior to those pro

vided for all other persons similarly situated

through the device of arbitrary judicial deci

sion that such discriminatory action provides

“ substantial equality” _____________________ 28

Co n c l u sio n_______________ _______________________ 33

I ll

Table of Cases

PAGE

Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe R. R. Co. v. Vosburg, 238

IT. S. 5 6 ________________________________________ 27

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U. S. 45______________ 26

Bluford v. Canada, 32 F. Supp. 707__________________ 29

Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28_______ 26

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60____________________ 25

Colgate v. Harvey, 296 U. S. 404____________________ 14, 27

Connolly v. Union Sewer Pipe Co., 184 U. S. 540______ 27

Cory v. Carter, 48 Ind. 337___________________________ 24

Cotting v. Kansas City Stock Yards Co., 183 U. S. 79__ 27

Cummings v. County Board of Education, 175 U. S.

528 ___________________________________________ 23,24

Dawson v. Lee, 83 Ky. 49___________________________ 24

I

Ex Parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339______-_______________ 26

Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S. 147_____________________ 25, 30

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78_...._______________ 23, 24, 25

Gulf Colorado & Sante Fe R. Co. v. Ellis, 165 U. S. 150.. 27

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485________________________ 23, 26

Hartford Steam Boiler Insurance and Inspection Co. v.

Harrison, 301 U. S. 459___________________________ 27

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400__________________________ 25

Johnson v. Board of Trustees (File No. 625, U. S. Dist.

Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky)_______ 30

IV

PAGE

Lehew v. Brnmmell, 103 Mo. 546________ 1_______ ___ 24

Louisiana ex rel. Hatfield v. Louisiana State University

(File 25,550, State Court for the 19th Judicial Dis

trict) ----------------------------------------------------------------- 30

Louisville Gas & Electric Company v. Cohen, 277 U. S.

32-------------------------------------------------- -------------------- 27

Mayflower Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297 U. S. 266__________ 27

McCabe v. Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe R. Co., 235

U. S. 151 ______________________________________ 23, 26

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, et al., No. 614,

October Term, 1948______________________________ 30

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337___23, 25, 29

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80________________ 26

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373____________________ 26

Ovama v. California, 332 U. S. 633__________________ 14, 25

Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478 ______________________ 30

People v. Gallagher, 93 N. Y. 438______________________ 24

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537______ 14, 23, 24, 25, 28, 29

Powers Mfg. Co. v. Saunders, 274 U. S. 490__________ 27

Quaker City Cab Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 U. S. 389___ 27

Royster Guano Co. v. Virginia, 253 U. S. 412__________ 27

Roberts v. Boston, 5 Cush. (Mass.) 198______________ 24

Shelley v. Kraemer. 334 U. S. 1 ____________________ 14. 25

Sipuel v. Board of Regents. 332 U. S. 631______2. 23. 25.30

Skinner v. Oklahoma. 316 U. S. 535 __________________ 27

Smith v. C&hoon. 2S3 U. S. 553____________ __________ 27

V

Southern Ry. Co. v. Greene, 216 U. S. 400____________ 27

State, ex rel. Michael v. Whitham, 179 Tenn. 250 ______ 29

State, Games v. McCann, 21 Ohio St. 210____________ 24

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303______________ 25

Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission, 332 U. S.

410___________________________________________ 14, 25

Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U. S. 312____________________ 27

Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S. 3 3 __________________ ’_____ 26

Virginia v. Rieves, 100 U. S. 313_____________________ 26

Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36____________________________ 24

Wrighten v. Board of Trustees, 72 F. Supp. 948_____24, 29

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 __________________ 25

Other Authorities

Argument of Charles Sumner, Esq., Against the Consti

tutionality of Colored Schools in the case of Sarah C.

Roberts v. Boston, 1849___________________________ 20

Ballantine, The Place in Legal Education of Evening

and Correspondence Law Schools, 4 Am. Law School

Rev. 369 (1918) _______ :_________________________ 21

Boyer, Smaller Law Schools, Factors Affecting Their

Methods and Objectives, 20 Oregon Law Rev. 281

(1941) _________________________________________ 21

“ Higher Education for American Democracy,” A Re

port of the President’s Commission on Higher Edu

cation, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washing

ton, December, 1947 _____________________________ 19

Holmes, “ The Use of Law Schools” in Collected Legal

Papers (1920)___________________________________ 21

PAGE

PAGE

Journal of Negro Education (1945), Vol. XIV, Fall

Number ________________________________________

McCormick, The Place and Future of the State Univer

sity Law School, 24 N. C. L. Rev. 441____________ 21,

Otto Klineberg, Negro Intelligence and Selective Migra

tion (N. Y., 1935) _______________________________

Peterson & L. H. Lanier, ‘ ‘ Studies on the Comparative

Abilities of Whites and Negroes,” Mental Measure

ment Monograph, 1929 ___________________________

Report of Board of Officers on Utilization of Negro

Manpower in the Post-War Army (February, 1946)

Simpson, “ The Function of a University Law School,”

49 Harv. L. Rev. 1068 __________________________20,

Sixteenth Census of the United States, Vol. I ll, Part

IV (1940) ______________________ _______________

Stone, “ The Public Influence of the Bar,” 48 Harv. L.

Rev. 1 __________________________________________

The Black and White of Rejections for Military Service,

Montgomery, Ala., American Teachers Association,

1944 __________________________________________ 18,

“ To Secure These Rights,” The Report of the Presi

dent’s Committee on Civil Rights, U. S. Government

Printing Office, 1947 _____________________________

Townes, Organization and Operation of a Law School, 2

Am. Law School Rev. 436 (1910)_________________

19

22

22

22

18

22

20

22

22

18

21

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1948

No.

H e man M arion S weatt,

Petitioner,

vs.

T heophilis S hickel P ainter, et al.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF TEXAS

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

Petitioner respectfully prays that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment of the Supreme Court of Texas

denying his application for writ of error to review the

judgment of the Court of Civil Appeals which had affirmed

the judgment of the District Court of Travis County dis

missing petition for writ of mandamus to compel respon

dents to admit petitioner to the University of Texas School

of Law.

2

P A R T O N E

SUMMARY STATEMENT OF THE MATTER

INVOLVED

I

Statement of the Case

This case is believed to present for the first time in this

Court a record in which the issue of the validity of a state

constitutional or statutory provision requiring the separa

tion of the races in professional schools is clearly raised.1

It is the first record which contains expert testimony and

other convincing evidence showing the lack of any reason

able basis for racial segregation at the professional school

level, its inherent inequality and its effect on the students,

the school and the state.

Over a period of two years three hearings were held in

the trial court. The first presented a situation in which the

state excluded Negroes entirely from its state-supported

law school facilities. The second came after the state had

proposed to undertake the establishment of a Negro law

school, and the third hearing took place subsequent to a

specific tender of segregated legal training of sorts by the

state. Throughout the three hearings, petitioner challenged

the validity of the constitutional and statutory provisions

of the state requiring racial segregation of students and the

resulting exclusion of petitioner from the law school of the

University of Texas because of his race as contravening

the Fourteenth Amendment.

1 There are two other cases involving a similar question. Mc-

Laurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, et al., No. 614, October Term,

1948 is now pending before this Court on direct appeal. Sipuel v.

Board of Regents, et al., 332 U. S. 631 was retried in the local court,

and a record made including testimony of experts in the fields of legal

training, anthropology and sociology. That case is now pending on

appeal before the Supreme Court of Oklahoma.

3

F irst H earing

On May 16, 1946 petitioner filed in the 126th District

Court of Travis County, Texas, a petition for a writ of

mandamus alleging that he had been refused admission to

the law school of the University of Texas solely because of

race and color (R. 403-408). On June 17, 1946 a hearing

was held, and on June 26th the district court entered an

order finding that the refusal to admit petitioner was a

denial of the equal protection of the laws for the reason

that no provision had been made for legal training for him.

The court, however, refused to grant the writ at that time

and gave the respondents six months to provide a course

of legal instruction substantially equivalent to that afforded

at the University of Texas setting the next hearing date for

December 17th (R. 424-426).

S econ d H earing

At the December 17th hearing it appeared that the state

had done no more than authorize the instruction of Negroes

at a non-existent law school to he established at Houston

(R. 426-432). Yet, the district court entered a final order

dismissing the petition for a writ of mandamus on the

ground that “ the said order of June 26, 1946 has been com

plied with in that a law school or legal training substantially

equivalent to that offered at the University of Texas has

now been made available to the Relator” (R. 433).

This judgment was appealed to the Court of Civil Ap

peals, and on March 26,1947 the judgment of the trial court

was set aside without opinion and the cause remanded gener

ally for further proceedings without prejudice (R. 434-435).

H earin g on the M erits

On May 1, 1947 respondents filed their first amended

original answer alleging that “ The Constitution and laws

4

of the State of Texas require equal protection of the law

and equal educational opportunities for all qualified persons

but provide for separate educational institutions for white

and Negro students” (R. 415). It was further alleged that

the refusal to admit petitioner was therefore not arbitrary

or in violation of the Constitution of the United States since

“ equal opportunities were provided for relator in another

state-supported law school” (R. 415).

On May 8, 1947 relator filed his second supplemental

petition pointing out that the proposed law school for

Negroes did not meet the requirements of the equal protec

tion clause and that the continued refusal to admit peti

tioner to the law school of the University of Texas was in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and that “ insofar

as respondents claim to be acting under authority of the

Constitution and laws of the State of Texas their continued

refusal to admit the relator to the law school of the Uni

versity of Texas is nevertheless in direct violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States” (R. 412). It was also alleged that “ such consti

tutional and statutory provisions of the State of Texas as

applied to Relator are in direct violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States” (R.

413).2

Thereafter, respondents filed their first supplemental

answer reaffirming their reliance upon the validity of the

provisions of the Constitution and laws of Texas requiring

racial segregation in public education (R. 420).

From May 12 to May 18, 1947, hearing was had and tes

timony was taken before the district court, sitting without

_ 2 At the trial o f tins case, the responsible officials of the University

t r Texas ~ a ;e :r dear rSat they refused adtvissicrt to the petitioner

7 tit; r - and 1 - V; . - ; ■

at the races in rubiic education (R. 40-41. 5o. 161)'

5

a jury, and on June 17, 1947 judgment was entered for

respondents. The judgment concluded that “ the constitu

tional right of the State to provide equal educational op

portunities in separate schools being well established and

long recognized by the highest state and federal courts, and

the facts in this case showing that Relator would be offered

equal if not better opportunities for the study of law in such

separate school, the petition for Writ of Mandamus should

be denied’ ’ (R. 440). (Italics ours.)

The Court of Civil Appeals affirmed the judgment of the

lower court on February 25, 1948 (R. 445-460). Motion for

rehearing was filed on March 11, 1948 (R. 461-464) and was

denied on March 11, 1948 (R. 465), with opinion appearing

in the record at pages 460-461.

On September 29, 1948 application for writ of error to

the Supreme Court of Texas was denied without opinion,

and on October 27,1948 motion for rehearing was overruled

(R„ 471).

On January 12, 1949 this Court issued an order extend

ing time to file this petition for writ of certiorari up to and

including March 23, 1949 (R. 472).

II

Summary of Testimony

The testimony offered by the respondents was limited

to the question of the alleged physical equality between

the law school at the University of Texas and the law school

for Negroes. The respondents produced no evidence to

justify the state’s constitutional and statutory provisions

requiring the segregation of the races in public law schools.

On the other hand, petitioner offered the uncontradieted

testimony of expert witnesses showing: (1) that there is

6.

no rational basis for compulsory racial segregation in public

education; (2) that there are no recognizable racial differ

ences as to capacities between students of different races;

and (3) that compulsory racial segregation in public edu

cation is harmful to the students of all groups and the

community. Petitioner also produced expert testimony

showing that it is impossible for a law school student to get

an education in a school limited to one racial group equal

to that obtained in a law school to which all other groups

are freely admitted. Expert testimony offered by the peti

tioner also showed the inevitable inequalities inherent in a

'public school system maintained on a basis of racial segre

gation.

A

T h e T w o L aw S ch ools

Although Negroes have always been excluded from the

University of Texas because of their race or color, the State

of Texas has never offered them “ separate but equal”

facilities (R. 56). As Dean Pettinger, a witness.for respon

dents who has studied educational facilities for Negro and

white students in Texas for thirty years, stated: “ I am un

able to think for the moment of colored institutions and

white institutions which do have equal facilities with which

I have been associated” (R. 33).

When petitioner applied for a legal education the only

law school in existence maintained by the State of Texas

was the one at the University of Texas (R. 425).

The University of Texas has been in existence since

the last century. The law school has been in existence for

more than fifty years and is recognized and accredited by

every association in the field (R. 90-91). The Negro school

had just been opened in March, 1947 and was not ac

credited by any agency (R. 96, 25).

7

P h ysica l P lant

The proposed Negro law school was to be set up in the

basement3 of a building in downtown Austin consisting of

three rooms of moderate size, one small room and toilet

facilities (E. 36). There were no private offices for either

the members of the faculty or the dean. The space for this

law school had been leased for a period from March to

August 31, 1947 at $125 a month, and the authorities were

negotiating for a new lease after that period (E. 41). It

was freely admitted that “ there is no fair comparison in

monetary value” between the two schools (E. 43). There

was no assurance as to where the proposed law school

would be located after August 31st, and it was not even

certain as to what city it would be in after August 31st

(E. 52-53).

L ibrary

While the law school at the University of Texas had a

well-rounded library of some 65,000 volumes (E. 133), the

proposed Negro school had only a few books, mostly case

books for use of first-year students (E. 21-22). However,

the students at the proposed law school for Negroes had

access only to the law library in the state capitol directly

across the street, a right in common with all other citizens

of the State of Texas (E. 45). A library of approximately

10,000 volumes had been requisitioned on February 25, 1947

(E. 40) but was not available for use at the time of the

opening of the Negro school on March 10 nor at the time

of the trial of this case (E. 44). The University of Texas

law school had a full-time, qualified and recognized law

librarian with two assistants (E. 139). The Negro law

3 Pictures of the building of the Law School at the University of

Texas and the basement quarters of the so-called Negro law school

appear in the record at pages 385-387 and 389.

8

school had neither librarian nor assistant librarians (R.

74, 80, 128).

It was admitted that the library at the state capitol, a

typical court library and not a teaching library, was not

equal to the one at the University of Texas, and did not

meet the standards of the Association of American Law

Schools (R. 134, 138, 145). It was also admitted that even

if the requisitioned boohs were actually obtained the library

would not then be equal to the library already in existence

at the law school of the University of Texas (R. 151).

F acu lty

The University of Texas Law School has a faculty con

sisting of sixteen full-time and three part-time professors

(R. 369-371). The proposed faculty for the Negro school

was to consist of three professors from the University of

Texas who were to teach classes at the Negro school in

addition to their regular schedule at the University of

Texas (R. 59, 84, 87).4 The comparative difference in value

between full-time and part-time law school professors was

freely acknowledged and it was admitted that the proposed

“ faculty” did not meet the standards of the Association

of American Law Schools (R. 59, 91-92).

S tu d en t B od y

There were approximately eight hundred fifty students

at the law -ehool of the University of Texas (R. 76). From

the record it appears that all qualified students other than

Negroes were admitted. There were no students at the

proposed Negro school at the date of opening nor at the

time of the trial 3. 162 . A.though several Negroes had

made inquiry concerning the school, none had applied for

* -i v is use sccwr. mar :mcss ter the lean and taeoitv members

iawtbed vert tc remain at the Unrrarsttr o f T ea s . R. 4e-N" .

9

admission (R. 162). If petitioner had entered this school

he would have been the only student.

The law school of the University of Texas had a moot

court, legal aid clinic, law review, a chapter of Order of the

Coif, and a scholarship fund (R. 102-105). None of these

were present or possible in the proposed Negro law school,

and Charles T. McCormick, dean of the two law schools,

testified that he did not consider these to be factors ma

terial to a legal education but rather, that they were “ ex

traneous matters” (R. 106).

B

T h e U nreasonab len ess o f C om p u lsory R acia l

S egrega tion in P u b lic L ega l E d u cation

Dr. Robert Redfield, Chairman of the Department of

Anthropology at the University of Chicago, testified, as an

expert, that there is no recognizable difference as to ca

pacities between students of different races and that scien

tific studies had concluded that differences in intellectual

capacity or ability to learn have not been shown to exist

between Negroes and other students. He testified that as a

result of his training and study in his specialized field for

some twenty years, it was his opinion that given a similar

learning situation with a similar degree of preparation, one

student would do as well as the other, on the average, with

out regard to race or color (R. 192-194).

Dr. Redfield testified further that the main purpose of

education is to develop in every citizen, in accordance with

the natural capacities of such citizen, the fullest intellectual

and moral qualities and the most effective participation in

the duties of citizenship (R. 192).

Dean Ear] G. Harrison of the University of Pennsyl

vania Law School, testifying as an expert in the field of

1 0

legal education, summed up the purposes of legal education

as follows: “ The studies that I have reference to have

pointed out in general that there are four objectives of law

school education. One is, of course, to prepare the prac

titioner. Second, is to prepare and train law teachers.

Third, is to train and prepare men for legal research, and

the fourth objective is to train and prepare men and women

for public service” (E. 220).

Professor Malcolm Sharp of the law faculty of the Uni

versity of Chicago testified as an expert in the field of legal

education and explained in detail the purposes of legal

training for public service giving examples of the benefits

to society of Negro lawyers trained for public service in

non-segregated law schools (E. 344-346).5

The experts on legal education also testified as to the

patent inequality between the two law schools and the im

possibility of equality between the schools. They agreed

that it was absurd to speak of any institution that has one

student as a law school (E. 216-217, 349-350). They stressed

the need for competition among students of all classes as

an absolute necessity for a legal education (E. 218, 344,

347). They testified that moot court, Order of the Coif,

scholarship fund, law reviews and legal aid clinics were

most important for a well-rounded legal education and that

they were "not by any means extraneous” (E. 221. 347).

*“Q. Xaw. ss a resnlr of year studies and your teaching ex-

terrmce. along with your experience in the Association of American

Law Scfsrois. wrali yea state arietiy the recognized purposes of a

taw school is of today?

“A. The purpese :t a !asr school is. i f eterse , first: to train to r

• ' ' :: tot ' ■ the w ' ir ~ ij The - : - -.

l a s been heenam g h r and a a e important. a s all o f the leading

scratds inne mo: crate-i r i r h o for peshfatss o t o c 'h a service, as

h 'T v g s ire m ilei :c to 5 L ® * * ranrkec extent, a.hninisr~.tr.ve

nr• • : ; Toe •.

mere ami mere i r s a x r x t~ :w ~tt far xa* rcr.vse. O : c o rse .

the w a rTmg: A m in e rs mrS saacLrs i s the r e h i“

11

These expert witnesses also testified that a sizeable body

of students of all races, classes and walks of life was of

major importance to an adequate legal education. They

denied that one Negro or a few Negroes at a segregated law

school could under any circumstances obtain a legal educa

tion equal to that obtained at the University of Texas (E.

227, 343, 344, 347, 350, 351, 352).

Each of the expert witnesses offered by the petitioner

testified that compulsory racial segregation in public educa

tion not only made it impossible for the Negro to get an

education equal to that offered to the students in the other

school but was harmful to the segregated Negro students,

the students in the other schools, and the community in gen

eral (E. 194-196, 198-199, 227, 341).

c

Inequalities Inherent in S egrega ted S ch oo l F acilities

The petitioner offered in evidence several reports of

governmental agencies, federal and state, showing without

exception the inequalities in educational facilities in segre

gated schools throughout the states where segregated

schools are required (E. 248). The petitioner also offered

the testimony of Dr. Charles Thompson, documented by

recognized governmental reports, showing conclusively

that wherever separate schools were maintained under

state law for Negro students, these schools were without

exception inferior to the schools maintained for students

of other racial groups. The comparison was broken down

into each category recognized by educators as valid for

comparison purposes (E. 228-283).° An appendix showing 6

6 Dr. Thompson’s testimony was admitted into the record but by

final order of the District Judge was ordered stricken from the record

as being beyond the scope of the pleadings and issues and immaterial

and irrelevant (R. 441).

12

in detail the inequalities in segregated school systems is

tiled herewith as “ Petitioner’s Appendix” .

Petitioner also offered the testimony of Donald G.

Murray who had been admitted to the law school of the

University of Maryland as a result of legal action and who

was the first Negro to be admitted to a law school in a

state where segregation is required in public schools. Ob

jection to this testimony was sustained but the testimony

was placed in the record on a bill of exceptions (R. 288).

This testimony showed that although dire consequences

were predicted by state officials of Maryland if Murray was

admitted to the law school, it developed that his admission

brought about no untoward results (R. 288-291).

P A R T T W O

OPINION OF THE COURT BELOW

The Court of Civil Appeals in affirming the judgment

of the lower court based its decision on existence of and the

validity of the state’s policy of segregation and found that

“ the State at the time of the trial had provided and made

available to Relator a course of instruction in law as a first

year student, the equivalent or substantial equivalent in its

advantages to him of that which the State was then pro

viding in the University of Texas Law School. We are not

dealing here with abstractions but with realities” (R. 149).

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Texas refusing

application for writ of error (R. 4461 and order overruling

motion for rehearing were made without an opinion (R. 17).

The opinions o f the trial court are discussed in Part One.

13

P A R T T H R E E

JURISDICTION

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title 28,

United States Code, section 1257 this being a case involving

rights secured under the Fourteenth Amendment. Peti

tioner ’s cause is founded upon rights secured by the Consti

tution of the United States.

P A R T F O U R

QUESTION PRESENTED

May the State of Texas Consistently With the Requirements

of the Fourteenth Amendment Refuse to Admit Petitioner

Because of Race and Color to the University of Texas

School of Law?

P A R T F I V E

REASONS RELIED UPON FOR ALLOWANCE

OF THE W RIT

I

The courts of Texas, and of many states, while pretend

ing to observe the requirements of equal protection of the

laws in educational matters, approve the exclusion of

Negroes from adequate public law schools, thus denying to

large numbers that equality of educational opportunity

which is the very foundation of democracy. The courts’

theory presupposes that the equality guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment can be realized in a pattern of com

pulsory racial segregation in public education. The extent

of this practice and the severity of its impact on the com

munity are such as to warrant consideration by this Court.

14

II

The court below relied on Plessy v. Ferguson. The in

consistency between the judicial approval of laws imposing

racial distinctions in Plessy v. Ferguson and the judicial

disapproval of similar distinctions and classifications in

more recent decisions including Oyama v. California,

Shelley v. Kraemer, Tdkahashi v. Fish <& Game Commission

should lead this Court to review the correctness of the doc

trine of Plessy v. Ferguson and overrule it.7

III

This Court should review and reverse the judgment be

low to prevent the several states from being free to restrict

Negroes to public educational facilities clearly inferior to

those provided for all other persons similarly situated

through the device of arbitrary judicial decision that such

discriminatory action provides “ substantial equality” .

CONCLUSION

W herefore, it is respectfu lly subm itted that this petition

fo r w rit o f certiorari to rev iew the judgm ent o f the court

below, should be granted.

W. J. D u rham ,

W illiam H. H astie,

W illiam R. Mihg, Jr.,

J ames M. Nabrit, J r .,

T hurgood M arshall,

R obert L. Carter, Attorneys for Petitioner.

E. B. B u u kley , J r .,

H arry B ellihger,

U. S. T ate,

Of Counsel.

7 Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537; Oyama v. California, 332

U. S. 633; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1; Takahashi v. Fish and

Game Commission, 332 U. S. 410. As to this Court’s disapproval

of unreasonable classifications generally, see, for example, Colgate v.

Harvey, 296 U. S. 404.

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1948

No.

H em an M arion S weatt,

Petitioner,

vs.

T heophilis S hickel P ainter, et al.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR W RIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF TEXAS

Opinion of the Court Below

The opinion of the Court of Civil Appeals can be found

at page 445 of this record, and that of the District Court of

Travis County is reported at page 438.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court rests upon Title 28, United

States Code, Section 1257. The District Court of Travis

County entered judgment for respondents on June 17, 1947.

15

16

Judgment was affirmed by Court of Civil Appeals, Febru

ary 25, 1948. Application for writ of error was refused by

Supreme Court of Texas on September 29, 1948 (R. 466).

Motion for rehearing was overruled on October 27, 1948

(R. 471). On January 12,1948 this Court extended the time

for filing this petition for writ of certiorari until March 23,

1949 (R. 472).

Statement of the Case

Pertinent facts involved in this case are set out in the

petition itself, and therefore, are not restated here.

Errors Relied Upon

The Court erred in refusing to consider evidence show

ing discriminatory features inherent in enforced racial

separation at the professional school level.

The Court erred in predicating its decision upon Plessy

v. Ferguson and in disregarding principles serving the basis

for more recent decisions of this Court in conflict with the

rationale of that case.

The Court erred in refusing to hold that the racial classi

fication here complained of was arbitrary and unreasonable

within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Court erred in finding that the law school for

Negroes at Austin was the “equivalent or substantial equi

valent of the law school of University of Texas” .

The Court erred in finding that the constitutional and

statutory provisions of the State of Texas requiring segre

gation in public education were consistent with the require

ments of the Fourteenth Amendment.

17

A R G U M E N T

I

The question whether a state which undertakes to

provide legal education for any of its citizens can sat

isfy the requirements of the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment by establishing a law

school for Negroes separate from the law school it pro

vides for all other persons is of great public impor

tance and should be decided by this Court in this case.

The education of the youth of our nation, formerly the

responsibility of the parent, has now become a recognized

function of government. This has become a matter of

national importance. The individual states have provided

public education through the graduate and professional

school levels. Most of the states provide educational facili

ties without regard to the race or creed of the student.

However, seventeen of the states have insisted upon either

the complete exclusion or the segregation of Negroes in

public education.1 The record of these states has brought

down the national level of education. The question of the

legality of such racial segregation, which amounts to actual

exclusion from the regular recognized state university, is of

great public importance.

The seventeen southern states where a pattern of edu

cational segregation is sanctioned and enforced by state law

comprise the area of our country which is least able to

afford either the financial or the educational hazards created

by a dual system of education. The burden on the treasury

in maintaining a dual system of education cannot help but

1 Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky,

Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Okla

homa, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, West Virginia.

18

be reflected in a deprivation of educational opportunities

and facilities for all groups.

The impact of this policy of segregation is felt not only

by the minority group, but the nation as a whole. In the

most critical period of June-July, 1943, when the nation

was crying for manpower, 34.5% of the rejections of

Negroes from the armed forces were for educational de

ficiency. Only 8% of the white selectees rejected for mili

tary service failed to meet the educational standards.2

The official War Department report on the utilization of

Negro manpower in the postwar Army says that “ in the

placement of men who were accepted, the Army encountered

considerable difficulty. Leadership qualities had not been

developed among the Negroes, due principally to environ

ment and lack of opportunity. These factors had also af

fected development in the various skills and crafts.” 3

■ Eecognizing that segregation constitutes a menace to

American freedom and was indefensible, the President’s

Committee on Civil Eights unequivocally recommended its

elimination from American life.4 In the same year, the

2 The Black and White of Rejections for Military Service, Mont

gomery, Ala., American Teachers Association, 1944, p. 5.

3 Report of Board of Officers on Utilization of Negro Manpower

in the Post-War Army (February, 1946), p. 2.

4 “To Secure These Rights” , The Report of the President’s Com

mittee on Civil Rights, U. S. Government Printing Office, 1947, p.

166 “ The separate but equal doctrine has failed in three important

respects. First, it is inconsistent with the fundamental equalitari-

anism of the American way of life in that it marks groups with the

brand of inferior status. Secondly, where it has been followed, the

results have been separate and unequal facilities for minority peoples.

Finally, it has kept people apart despite incontrovertible evidence that

an environment favorable to civil rights is fostered whenever groups

are permitted to live and work together. There is no adequate de

fense of segregation.” Ibid.

19

President’s Commission on Higher Education, in its report

on education in the United States said:5

“ The time has come to make public education at

all levels equally accessible to all, without regard to

race, creed, sex or national origin.”

This, too, is the almost unanimous conclusion of scholars

and students who have studied the problem.

The professional skills developed through graduate

training are among the most important elements of our

society. Their importance is so great as to be almost self-

evident. Teachers pass on skills and knowledge from one

generation to another. Engineers create and service the

technology that has been bringing more and more good to

more and more people. Doctors and dentists guard the

health of their people. Lawyers guide their relationships

in a complicated society.

Racial inequality in education has resulted in a loss to

the nation of the development of these professional skills in

a great part of our population. Because of the limited op

portunities open to Negroes in professional education, in

the United States in 1940, there was one white physician

for every 735 white citizens, but only one Negro doctor for

every 3,651 Negroes.6 And one wMte lawyer served 670

whites, but there was only one colored lawyer for every

12,230 Negro citizens.7 In the petitioner’s native state of

Texas, the same deprivation of professional services exists.

In 1940 in Texas, one white lawyer served 709 whites,

5 “ Higher Education for American Democracy” , A Report of the

President’s Commission on Higher Education, U. S. Government

Printing Office, Washington, December, 1947, p. 38.

8 Journal of Negro Education (1945), Vol. XIV , Fall number,

p. 511.

7 Ibid, p. 512.

20

whereas there was only one Negro lawyer for every 40,191

Negroes.8

Perhaps even more important than the harriers which

segregation offers to the development of leadership and

professional skills is its corrosive effect npon the funda

mentals of a democratic society. Neither white nor Negro

Americans can maintain complete and foil allegiance to the

basic tenet npon which our government is founded—“ that

all men are created equal'’—when pupils are being forcibly

kept apart in the public- schools because of their racial iden

tity.

It is essential for the successful development of our

country as a nation of free people that the sympathies and

tolerance which we wish practiced in later life be fostered

in the classroom. “ And since according to our institutions,

all classes meet, without distinction, in the performance of

civil duties, so should they all meet, without distinction of

color, in the school, beginning there those relations of

equality which our Constitution and laws promise to ah." ■

Enforced separation in the law sehooL moreover, is par

ticularly pernicious because of the vital importance which

the lawyer marntain^in our. society. Law is “ a public pro

fession charged with inescapable social responsibilities."1'1

The prime purpose of legal training must be not merely, as

Mr. Justice Honweg has said, “ to make men smart, but to

* r/n fata j# Sixteenth Census of the Uiated States: Popu-

,',i t, Reportslsy States (AMD).

' or C-.srlet 'rscscer, Esqp Agdmst die Gmacra j ja-

‘■;cy or Ovor-e: x'f.tfx; ir. on* c m Samk C. Roberts v. Bottom*

■ Wf. ZXy 20 '/»

,4 .-.w.-.yif,’'. 1 m s’vxi'xv.m o f a U rn m stv Law School". 49

L U*y, I«m , W72,

21

make them wiser in their calling” ,11 and “ to train men for

public service.” 12

The testimony of the expert witnesses in legal education

called by the petitioner 13 is amply supported by other ex

perts. Eminent authorities in the field of legal education

have demonstrated that there are certain features of a law

school which are necessary to a proper legal education which

can only be found in a full-time, accredited law school.14

Some of these are: a full-time faculty,15 a varied and inclu

sive curriculum,16 an adequate library, well-equipped build

ing and several classrooms,17 a well-established, recognized

law review and a moot court.18

Equally essential to a proper legal education in a demo

cratic society is the inter-change of ideas and attitudes

which can only be effected when the student-body is repre

sentative of all groups and peoples. Exclusion of any one

11 Holmes, “ The Use of Law Schools” in Collected Legal Papers

(1920), pp. 39-40.

12 Malcolm Sharp, testimony at p. 341 in Record. See also Mc

Cormick, “ The Place and Future of the State University Law School,”

24 N. C. L. Rev. 441, “ As we rebuild our curricula, it seems that

more attention should be given to the knowledge that a lawyer needs

in order to be a community leader— such matters as planning, zoning,

and housing come to mind—and to the adaptation of the public law

courses not only to the needs of the lawyer serving private clients,

bat to the requirements of graduates who will enter the service of

the slate and national governments,”

. l- ■ h o u r o ; v j. u n r , v : a , a a: ;/.<•/; r th< pet ' ion

at pages 9 to l i ,

bee kon-er “ smaller \>.w iybools factors Affecting 1 heir

ICeihrU am ' J o t r : ■ 20 Oregon lu-vv !'<-/ 2U f 3941;

24 / ":C

*J w l,

T wa*r. C''ttan za',<rr a</i UjAtatiou </■ >- / m o o . 2

.Ant Lav V,ooo he CViOy, fcallantita o> V & tj »

Ln:"-aa".e o <■ '/■■■’/,> ' < hr. -Jo.'.

x s :'r j. Lerer-r- YjY/_

k' C o r 1 / m// 1'aetv‘ AlfeeUng 1 net'

2' '/SV 7- R* 22 ' !9 S

22

group on the basis of race, automatically imputes a badge

of inferiority to the excluded group—an inferiority which

has no basis in fact.19 The role of the lawyer, moreover, is

often that of a law-maker, a “ social mechanic” , and a

“ social inventor.” 20 A profession which produces future

legislators and social inventors to whom will fall the social

responsibilities of our society, can not do so on a segregated

basis.21

It is evident that even if it were possible to construct a

law school building for Negroes equal in all respects to the

one now in existence at the University of Texas with a

library equal in all respects, with a faculty of equal num

ber and equal ability (if possible), the separate law school

could not meet the recognized requirements set out above.

Actually, in so far as legal education is concerned, an equal

education is impossible in a jim-crow law school.

Even apart from this, it is absurd to speak of a school

with only one student as a law school. In the field of legal

education, even more so than in other fields of public edu

cation, the blind adherence to the practice of compulsory

racial segregation not only deprives the individuals in

volved of the equality of law, but deprives the state and the

nation of properly trained specialists necessary to our

government.

19 “ The Black and White of Rejections for Military Service,”

American Teachers Association, August, 1944, page 29; Otto Kline-

berg, “ Negro Intelligence and Selective Migration,” New York,

1935; J. Peterson & L. H. Lanier, “ Studies in the Comparative Abili

ties of Whites and Negroes,” Mental Measurement Monograph, 1929.

20 Simpson, “ The Function of a University Law School,” 49

Harv. L. Rev. 1068, 1072. See also McCormick, “ The Place and

Future of the State University Law School,” 24 N. C. L. Rev. 441.

21 Simpson, op. cit., p. 1069. See also Stone, “ The Public Influ

ence of the Bar,” 48 Harv. L. Rev. 1.

23

II

The inconsistency between the judicial approval of

laws imposing racial distinctions in Plessy v. Ferguson

and the judicial disapproval of similar distinctions and

classifications in more recent decisions should lead this

Court to review and disavow the doctrine of Plessy v.

Ferguson.

In upholding the denial of petitioner’s application for a

writ of mandamus, the Court of Civil Appeals said: “ The

validity of state laws which require segregation of races in

state-supported schools, as being, on the ground of segre

gation alone, a denial of due process, is not now an open

question. The ultimate repository of authority to construe

the Federal Constitution is the Federal Supreme Court. We

cite chronologically, in a note below, the unbroken line of

decisions of that tribunal recognizing or upholding the

validity of such segregation as against such attack.” In

support of this proposition, Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U. S. 485;

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537; Cummings v. County

Board of Education, 175 U. S. 528; McCabe v. Atchison, T.

<& 8. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 151; Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S.

78; Missouri ex ret. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337; Sipuel

v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 were cited.

Plessy v. Ferguson raised in this Court for the first time

the question of the constitutionality of a state statute en

forcing segregation based upon race and color. In that

case, a Louisiana statute requiring the separation of Negro

and white passengers was held to be consistent with the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Yet

the opinion appears to rely heavily upon the leading state

case in this field—-and the only one of the cited cases dis

24

cussed in the majority opinion22—Roberts v. Boston, 5

Cush. (Mass.) 198 (1849), decided almost twenty years be

fore the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment. Yet, it

was the very diversity of opinion, so pronounced in 1849,

on the reasonableness of legal distinctions based on race

which the Fourteenth Amendment sought to settle. Ante

bellum justifications of segregation have no more logical

place in the interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment

than antebellum notions of voting restrictions have in de

fining the scope and meaning of the Fifteenth Amendment.

In addition, Plessy v. Ferguson was decided upon plead

ings which assumed a theoretical equality within segrega

tion rather than on a full hearing and evidence which would

have revealed equality to be impossible under a system of

segregation.

An examination of the other decisions of this Court upon

which the lower court relied shows that the doctrine of

Plessy v. Ferguson has not been reexamined nor seriously

challenged.

In Cummings v. Board of Education, supra, the issue of

the validity of the segregation statute was not even raised.

In fact plaintiffs there acquiesced in the use of taxes levied

to support segregated schools at the elementary and inter

mediate grammar school levels. The main purpose of the

suit was to secure an injunction forcing the discontinuance

of a high school for whites since no school was being

maintained for Negroes. This remedy the Court considered

improper.

In Gong Lum v. Rice, supra, again the question was not

raised. The primary issue there was whether a Chinese

22 Other cases cited in the opinion include: People v. Gallagher,

93 N. Y. 438; and Ward v. Flood, 48 Cal. 36; State, Gdrnes v. Mc

Cann, 21 Ohio. St. 210; Lehew v. Brummell, 103 Mo. 546; Cory v.

Carter, 48 Ind. 337; Dawson v. Lee, 83 Ky. 49.

25

could be excluded from the white schools under the segre

gation statutes of Mississippi, and could be classified as a

colored person and required to attend the Negro school.23

In the Gaines case, supra, although the doctrine of

Plessy v. Ferguson was repeated, it was neither examined

nor applied. There the main issue before the Court was

whether a qualified Negro applicant could be excluded from

the only state supported law school. The Court decided that

question in the negative.

In Sipuel v. Board of Regents, supra, the doctrine

of Plessy v. Ferguson was neither raised, examined, re

peated nor applied. The Court specifically stated that the

appellant was entitled to receive educational benefits at the

same time and as soon as it was offered to applicants of

any other group. Moreover in Fisher v. Hurst, 333 U. S.

147, the same case, supra, this Court was asked to issue an

original petition for a writ of mandamus to compel com

pliance with its mandate there. The Court denied the writ

on the grounds that the original Sipuel case had specifically

not raised the issue of the validity of the segregation stat

utes and that procedurally the question could not be con

sidered on the petition for writ of mandamus.

23 It is true that Mr. Chief Justice T a f t , op. cit., supra, at page

85 in discussing the issue said: “ Were this a new question it would

call for very full argument and consideration, but we think that it

is the same question which has been many times decided to be within

the constitutional power of the State Legislature to settle without

intervention of the Federal Courts under the Federal Constitution.”

Therefore, even if this decision is construed as raising the issue of the

validity of school segregation statutes, it is clear that the doctrine was

not examined and that Plessy, v. Ferguson was relied upon without

question.

26

This is the group of cases upon which the separate but

equal doctrine under the Fourteenth Amendment is said to

depend.24 The inconsistencies between the “ separate but

equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson and the reasoning

and holdings of a considerable body of decisions of this

Court become readily apparent when analysis is made in

terms of the fundamental question, common to all, whether

racial differences can be made the bases for legislative dis

tinctions in the face of the Fourteenth Amendment. Except

in Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, and the decisions which rely

uncritically upon it, this Court has consistently concluded

that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the states from

making racial differences and other arbitrary distinctions

the bases for general classifications. This impressive and

carefully considered group of cases includes: Takahashi v.

Fish & Game Commission, 332 U. S. 410, 420 L. ed. 1096,

1101; Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633, 640, 646; Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 20, 23; Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118

IJ. S. 356, 373, 374; Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 82;

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400, 404; Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U. S. 303, 307, 308; Truax v. Raich, 239 IT. S. 33, 41, 42;

24 Another case in point but not relied upon by the court below

is Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U. S. 45. That case appears

to accept the doctrine insofar as the power of the state to place

conditions on a corporate charter. Hall v. DeCuir, supra; McCabe v.

Atchison, T. & S. F. R. Co., 235 U. S. 151; Mitchell v. United States,

313 U. S. 80 were decided under the Commerce Clause of the Federal

Constitution and need not be considered in a decision as to the validity

of the equal but separate doctrine within the meaning of the Four

teenth Amendment. The foundation of even those cases, however,

seems to have been shaken. Compare Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S.

373; Bob-Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U. S. 28.

27

Virginia v. Rieves, 100 U. 8. 313, 322; Ex Parte Virginia,

100 U. S. 339, 344, 345.25

These cases merely apply to racial distinctions the gen

eral constitutional principle applicable in all other areas.

Their rationale is merely a part of and consistent with the

basic principle that all governmental classifications must be

based upon a significant difference having a reasonable rela

tionship to the subject matter of the statute. Southern

Railway Co. v. Greene, 216 U. S. 400, 417; Gulf Colorado d

Sante Fe Railway Co. v. Ellis, 165 U. S. 150, 155; Connolly

v. Union Sewer Pipe Co., 184 IT. S. 540, 559, 560; Atchison

Topeka d Santa Fe Railway Co. v. Vosburg, 238 U. S. 56,

60, 61; Royster Guano Co. v. Virginia, 253 U. S. 412, 416,

417; Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U. S. 553, 566, 567; Hartford

Steam Boiler Inspection d Insurance Co. v. Harrison, 301

U. S. 459, 462, 463; Colgate v. Harvey, 296 IT. S. 404, 422,

423; Mayflower Farms v. Ten Eyck, 297 U. S. 266, 274;

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 IT. S. 535, 541, 542; Louisville Gas

d Electric Co. v. Cohen, 277 U. 8. 32, 37; Quaker City Cab

Co. v. Pennsylvania, 277 IT. S. 389, 400; Powers Mfg. Co. v.

Saunders, 274 IT. S. 490, 493; Truax v. Corrigan, 257 IT. S.

312, 337; Cotting v. Kansas City Stock Yards Co., 183 IT. S.

79, 106, 107.

25 Takahashi v. Fish & Gdme Commission; Yick Wo v. Hopkins

and Truax v. Raich involved the right to engage in a useful occupa

tion. Oyama v. California, Shelley v. Kraemer and Buchanan v.

Warley involved the right to own, occupy, sell and lease real prop

erty. Hill v. Texas, Strauder v. West Virginia, Virginia v. Rieves

and E x Parte Virginia, involved the right of Negroes to be free of

discrimination in the selection and composition of grand and petit

juries.

Despite the different problems involved, the Court made the

same fundamental approach to each case. Underlying each decision

is the basic proposition that race alone cannot be a valid criterion upon

which to sustain governmental action under the 14th Amendment.

Finding on examination that the real purpose and effect of the state’s

action ̂was racial discrimination, no difficulty was encountered in

declaring the action unconstitutional.

28

Neither the decision nor the rationale of Plessy v. Fer

guson can he reconciled with this impressive body of au

thorities.

The Court below in relying on Plessy v. Ferguson and in

ignoring this body of cases has improperly and mistakenly

construed the limitations of the Fourteenth Amendment as

applied to the instant case. For not only is Plessy v. Fer

guson inconsistent with many decisions of this Court, but it

was wrongly decided. In sustaining a statute based upon

a difference in the color of citizens, this Court made a

radical departure from the body of cases, cited supra, under

which such a distinction would have necessarily been con

strued as arbitrary and therefore unlawful. In requiring

that a classification be based upon a significant difference

having a reasonable relationship to the subject matter of the

statute, that body of decisions rests upon a sound founda

tion. The same principle should be controlling in the in

stant case. Any other approach makes the equal protection

clause meaningless. Insofar as Plessy v. Ferguson affects

the application of that principle to the instant case, it

should not be followed.

Ill

This Court should review and reverse the judgment

below to prevent the several states from being free to

restrict Negroes to public educational facilities clearly

inferior to those provided for all other persons simi

larly situated through the device of arbitrary judicial

decision that such discriminatory action provides “sub

stantial equality” .

Texas and sixteen other states have insisted that public

education can only be furnished on a basis of racial distinc

29

tion between students. The purpose of this practice is to

exclude Negroes from the recognized state educational in

stitutions. The record in this case, as in other cases, will

demonstrate that these states first establish facilities for

non-Negroes. Later, either as a result of legal action or

other compulsion, separate institutions have been estab

lished for Negroes.

The record in this case, the record in similar cases,

governmental and private studies, demonstrate clearly that

the separate Negro facilities are never equal to the facilities

established for other groups. In short, we have been unable

to find a single recognized study of public education on a

segregated basis which reveals equality of opportunity as

between the segregated and non-segregated schools. The

Negro school is invariably an inferior school.

The “ separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v.

Ferguson, relied upon by Texas and the other southern

states is based on the hypothesis that equal facilities can be

realized in a segregated school system. The record in this

case and in other cases has demonstrated the invalidity of

such a hypothesis. It is clear not only that the doctrine of

“ separate but equal” has not produced equality, but can

never provide the equality required by the Fourteenth

Amendment.

This separate but equal doctrine has brought about con

stant and continual litigation. Negroes have gone to the

courts in Missouri,26 South Carolina,27 Tennessee,28 Louisi

26 Missouri, ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra; Bluford v. Canada,

32 F. Supp. 707 (1940) (Appeal dismissed 119 F. (2d) 779 (C. C.

A. 8th)).

27 Wrighten v. Board of Trustees, 72 F. Supp. 948.

28 State, ex rel. Michael v. Whitham, 179 Tenn. 2S0, 165 S. W.

(2d) 378 (1942).

30

ana,29 30 31 Oklahoma,80 Maryland,81 Kentucky,32 and Texas in

order to secure educational advantages equal to those being

offered to all other qualified persons. The formula con

stantly invites such court action. In all instances this has

meant loss of time and years out of an individual’s career,

while his case pursues its way through the courts. This

very fact shows the weakness of the doctrine.

The states are more interested in maintaining segrega

tion than in affording equality. Hence the separate but

equal doctrine has now become the “ separate but substan

tially equivalent’ ’ doctrine. The record in this case is a

clear example of the circuitous route forced upon a Negro

litigant seeking only to enforce a right recognized as belong

ing to every other qualified applicant except those who

happen to be Negroes.

Petitioner in this case applied for admission to the exist

ing state law school on February 26, 1946. All qualified

students other than Negroes who applied at the same time

and who successfully passed their examinations are now

either practicing law or are ready to take the bar examina

tion for that purpose. On the other hand, the petitioner,

solely because of his race and color, after long, extended

and involved litigation is still without a legal education.

29 Louisiana, ex rel. Hatfield v. Louisiana State University (File

25,520, State Court for the 19th Judicial District).

30 Sipuel v. Board o f Regents, supra; Fisher v. Hurst, supra;

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, No. 614, U. S. Supreme

Court, Oct. Term, 1948.

31 Pearson v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 Atl. 590 (1936).

32 Johnson v. Board of Trustees (File No. 625, U. S. Dist, Court

for the Eastern Dist. o f Kentucky).

31

At the first hearing in this case, although the trial court

concluded that petitioner had been denied rights guaranteed

by the Constitution, nevertheless, because of the separate

but equal doctrine, it refused to issue the order for the

necessary relief and allowed the state six months in which

to set up the facility separate from that in existence at the

University of Texas. At the end of the six months’ period

the trial court again reverted to the separate but equal doc

trine and found that petitioner had been given substantially

equivalent educational opportunities to that afforded to

whites at the University of Texas on the mere promise of

the state to establish a law school for Negroes in Houston.

At the third hearing, this same court in the face of peti

tioner’s testimony which conclusively established that the

facilities in the basement law school at Austin, faculty,

library and in all respects were in no way equal or substan

tially equivalent to the law school at the University of Texas

found that this makeshift school established over night in a

basement of a building afforded to petitioner “ equal if not

better opportunities for the study of law,” than he could

obtain at the University of Texas.

The Court of Civil Appeals in the face of this clear

evidence showing that the Negro school was inferior to

the white school agreed with the petitioner that there could

be no substantial equality, the two words being incom

patible in themselves, but said the Court:

“ This is of course true in pure, as distinguished

from applied, mathematics. ‘ Equality’ like all ab

stract nouns must be defined and construed accord

ing to the context or setting in which it is employed.

Pure mathematics deals with abstract relations,

predicated upon units of value which it defines or

assumes as equal. Its equations are therefore exact.

But in this sense there are no equations in nature;

32

at least not demonstrably so. Equations in nature

are manifestly only approximations (working hy

potheses) ; their accuracy depending upon a proper

evaluation of their units or standards of value as

applied to the subject matter involved and the ob

jectives in view. It is in this sense that the decisions

upholding the power of segregation in public schools

as not violative of the fourteenth amendment, em

ploy the expressions ‘ equal’ and ‘ substantially equal’

and as synonymous” (E. 449).

The most authoritative studies made on public education

in the United States clearly indicate that the Negro insti

tutions are vastly inferior to the whites. Yet when faced

with the necessity of holding Negro institutions to be in

ferior to the white and therefore to order the admission of

the Negro to the white institution, courts have fallen back

on the formula “ substantially equivalent” to justify their

decision to refuse the admission of the Negro into the white

institution.

If it were not for the constitutional and statutory pro

visions requiring segregation in public education in Texas,

there could be little doubt that the lower courts would have

ordered the admission of the petitioner. If it were not for

the existence of the “ separate but equal” doctrine, the

lower courts would have had no difficulty in declaring that

said constitutional and statutory provisions were unreason

able classifications and therefore unlawful. But for the

“ separate but equal doctrine” , the Texas courts would not

have been able to justify the Negro law school as “ substan

tially equivalent” and would have declared the constitu

tional and statutory provisions to be unreasonable classi

fications in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Therefore, the only way for the petitioner in this case

and other qualified Negroes to obtain a legal education equal

33

to that obtained by all other qualified applicants is by ad

mission to the recognized state institutions. The only way

this can be accomplished is for this Court to reconsider the

doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson and overrule it.

CONCLUSION

W herefore, it is respectfu lly subm itted that this petition

fo r w rit o f certiorari to review the judgm ent o f the court

below , should be granted.

W. J. D urham ,

W illiam H. H astie,

W illiam E. M ing, J r .,

J ames M. Nabrit, J r .,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

E obert L. Carter,

E. B. B u n kley , J r .,

H arry B ellinger,

U. S. T ate,

Of Counsel.

f

Lawyers Press, Isc ., 165 William St., N. Y. C. 7; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300