League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), Council #4434 v. Mattox Opinion

Public Court Documents

January 27, 1993

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), Council #4434 v. Mattox Opinion, 1993. c6223724-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e06cde16-cd04-4653-a0a5-d73ca2b2ddf0/league-of-united-latin-american-citizens-lulac-council-4434-v-mattox-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

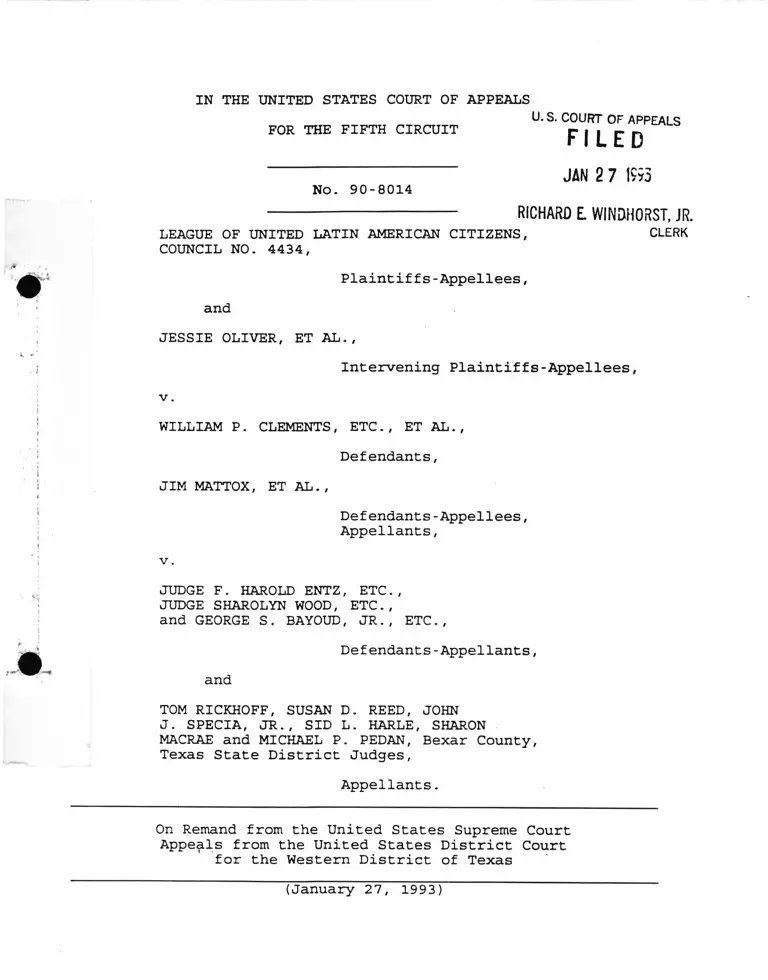

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT U. S. COURT OF APPEALS

FILED

JAN 2 7 1953No. 90-8014

-------------------------------------------------- RICHARD E. WINDHORST, JR.

LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN AMERICAN CITIZENS, CLERK

COUNCIL NO. 4434,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

and

JESSIE OLIVER, ET AL.,

Intervening Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

WILLIAM P. CLEMENTS, ETC., ET AL.,

Defendants,

JIM MATTOX, ET AL.,

Defendants-Appellees, Appellants,

v.

JUDGE F. HAROLD ENTZ, ETC.,

JUDGE SHAROLYN WOOD, ETC.,

and GEORGE S. BAYOUD, JR., ETC.,

Defendants-Appellants,

and

TOM RICKHOFF, SUSAN D. REED, JOHN

J. SPECIA, JR., SID L. HARLE, SHARON

MACRAE and MICHAEL P. PEDAN, Bexar County,

Texas State District Judges,

Appellants.

On Remand from the United States Supreme Court

Appeals from the United States District Court for the Western District of Texas

(January 27, 1993)

I. BACKGROUND............................................ 14

A. Texas' Method of Electing District Court Judges . . 14

B. Procedural History .............................. 16

II. THE ACCEPTED FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYZING SECTION 2

VOTE DILUTION CLAIMS............... 20

A. The Threshold Inquiry: The Gingles Factors . . . . 22

1. Size and Geographical Compactness of the

Minority Group .............................. 23

2. Political Cohesiveness of the Minority Group . 24

3. Legally Significant White Bloc Voting . . . . 27B. The Broader Inquiry: The Totality of the

Circumstances .................................... 32

1. The Senate Report Factors ..................... 33

a. History of discrimination touching the

rights of minorities to participate in

the political process................. 33

b. Extent of racially polarized voting . . . 34

c. Use of voting practices that enhance the

opportunity for discrimination........ 3 8

d. Minority access to the slating process . . 40

e. Lingering socioeconomic effects of

discrimination ........................ 41

f. Use of racial appeals in campaigns . . . . 41

g. Extent to which minority candidates have

been elected to public office.......... 42

h. Responsiveness of elected officials to

particular needs of the minority group . 4 6

i. Tenuousness of the policy underlying the

challenged practice.................... 4 7

2. Other Relevant Factors, Including Racial

Animus in the Electorate.................... 48

C. The Ultimate Inquiry: Unequal Opportunity to

Participate on Account of Race or Color.......... 51

III. THE PROPOSED BALANCING FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYZING

SECTION 2 VOTE DILUTION CLAIMS .......... 55

A. The Accepted Role of State Interests in Section 2Analysis........................................ 55

B. The Proposed Role for State Interests in Section 2Analysis........................................ 56

C. Problems with the Proposed Balancing Framework . . 59

1. The Legal P r o b l e m .............................59

a. Congressional intent .................... 59

b. Federalism principles.....................61

c. The Supreme Court's decision in Houston

Lawyers' Association .................. 67

2. The Practical P r o b l e m ......................... 73

3 . Summation..................................... 76

D. Applying the Proposed Balancing Framework in this

Case: Evaluating Texas' Asserted Interests . . . . 76

2

1. Identifying the Threatened State Interests . . 77

2. Scrutinizing the Threatened State Interests . 80

a. Texas' interest in preserving the

administrative advantages of the current

at-large system...........................81

b. Texas' interest in allowing judges to

specialize...............................82

c. Texas' linkage interest ................ 83

d. Texas' interest in preserving the

function of district court judges as

sole decision-makers.................. 9 0

3. Assigning a Weight to the Threatened StateInterests..................................... 96

IV. REVIEW OF THE DISTRICT COURT'S SECTION 2 LIABILITY

FINDINGS........................ ......................98

A. Standard of Appellate Review .................... 99

B. Review of the District Court's Vote Dilution

Findings Under the Accepted Section 2 Framework . . 101

1- Statistical Methodology .................... 101

2. Review of District Court's Vote Dilution

Findings......................................108

a. Bexar County........................... 109

(i) Gingles f a c t o r s .....................110

(ii) Totality of circumstances factors . 112

(iii) Ultimate vote dilution finding . . 117b. Dallas C o u n t y ......................... 118

(i) Gingles f a c t o r s .....................118

(ii) Totality of circumstances factors . 120

(iii) Ultimate vote dilution finding . .13 0

c. Ector County........................... 131

(i) Gingles f a c t o r s .....................132

(ii) Totality of circumstances factors . 134

(iii) Ultimate vote dilution finding . . 137d. Harris C o u n t y ......................... 13 8

(i) Gingles f a c t o r s .....................138

(ii) Totality of circumstances factors . 142

(iii) Ultimate vote dilution finding . . 147e. Jefferson County....................... 148

(i) Gingles f a c t o r s .....................148

(ii) Totality of circumstances factors . 151

(iii) Ultimate vote dilution finding . . 154

f. Lubbock County......................... 155

(i) Gingles f a c t o r s .....................155

(ii) Totality of circumstances factors . 158

(iii) Ultimate vote dilution inquiry . . 161g. Midland County......................... 162

(i) Gingles f a c t o r s .....................162

(ii) Totality of circumstances factors . 165

(iii) Ultimate vote dilution finding . . 167h. Taurrant County......................... 168

(i) Gingles f a c t o r s .....................168

3

(ii) Totality of circumstances factors . 170

(iii) Ultimate vote dilution finding . . 173

i. Travis C o u n t y .............. 174

3. Effect of District Court's Refusal to

Consider Partisan Voting Evidence .......... 177

a. The Partisanship Evidence............. 178

(i) History of partisan politics in

T e x a s ........................... 179

(ii) How partisan politics operate in

Texas district court elections . . . 180

(iii) The limitations of the

partisanship evidence........... 184

(iv) Summation of partisanship

evidence......................... 185b. The District Court's Treatment of the

Evidence............................. 186

c. The District Court's Error............. 188

d. The Effect of the Error; Whitcomb

Considered........................... 1904. Summation................................. 204

C. Review of the District Court's Vote Dilution

Findings Under the Proposed Balancing Framework . .205

V. R E M E D Y ............................................... 207

VI. CONCLUSION........................................... 210

DISSENT OF PATRICK E. HIGGINBOTHAM, Circuit Judge ............ 1

APPENDIX A TO JUDGE HIGGINBOTHAM'S DISSENT ................ 57

4

Before KING, JOHNSON and HIGGINBOTHAM, Circuit Judges.

KING, Circuit Judge:

This case is before us on remand from the Supreme Court's

decision in Houston Lawyers' Association v. Attorney General of

Texas. Ill S. Ct. 2376 (1991), in which the Court held that

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, applies to

all Texas judicial elections. We must now address a question

that is undoubtedly easier to frame than to answer. In

particular, we must decide whether the district court erred in

concluding that the method by which Texas elects district court

judges--as that method operates in nine counties--violates

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. After a careful review of

the record, we hold (1) that the district court correctly

concluded, in eight of the counties at issue, that Texas' method

of electing district court judges violates Section 2, but (2)

that the district court erred in finding a Section 2 violation in

Travis County. We therefore affirm the district court's decision

in part, reverse the decision in part, and remand the case to the

district court for consideration and imposition of an appropriate

remedy.

5

In view of the length of this opinion,1 a summary of the

pertinent facts and major legal conclusions may be helpful to the

reader:

As with all cases under the Voting Rights Act, this one is

driven by the facts. In this case, certain key facts are best

summarized by the following table which sets forth, with respect

to each of the nine Texas counties at issue, the population of

the relevant minority group, the total number of district court

judges elected in the county, the number of judges who are

members of the relevant minority group and the percentage of the

total number of district judges who are members of the relevant

minority group. *

' An explanation for the length of this opinion is in order. This case was tried and decided in 1989. Since then, it has

taken an unexpected detour to the Supreme Court and back. We

recognize that this panel may well not have the last appellate

word. The parties and amici have filed briefs totalling nearly

1200 pages and have raised an extraordinarily large number of

issues in what is, in reality, nine separate Voting Rights Act

cases. This opinion attempts to address all the issues raised,

with the hope of facilitating the ultimate resolution of the case

and minimizing the need for further consideration at our level of issues already briefed.

6

Number of Percentage of

judges who judges who are

are members members of

Relevant Total of the relevant

minority no. of relevant minority

County population* district judgesb minority group' group

Bexar 46.6% Hispanic 19 5 26.3%

Dallas 18.5% Black ~ 36 2d 5.5%

^Pctor 26.0% Black &

Hispanic

4 0 0.0%

Harris 19.7% Black 59 3 5.1%

Jefferson 28.2% Black 8 0 0.0%

Lubbock 27.0% Black &

Hispanic 5 0 0.0%

Midland 23.5% Black &

Hispanic

3 0 0.0%

Tarrant 11.8% Black 23 2e 8.7%

Travis 17.2% Hispanic 13 0 0.0%

* This data was taken from the 1980 Census

b These numbers reflect the total number of district judges elected in

the county as of 1989.

c These figures represent the number of judges who were on the bench

in 1989.

d These two Black judges were elected with virtually no support from

Dallas County's Black community.

c One of these Black judges was elected with very little support from

the Black community in Tarrant County, and the other judge obtained her

seat through appointment.

7

The table portrays graphically what is inescapable from the

record in this case--that in Texas district court elections,

minority voters have less opportunity than white voters to

participate in the political process and to elect representatives

of their choice. The powerlessness of Texas minority voters in

state district court elections stands in marked contrast to the

increasing ability of those voters to participate in the

political process and to elect representatives of their choice in

the context of federal and state legislative elections and in

local city council and school board elections. The strides that

minority voters have made in the latter elections are due in no

small part to the Voting Rights Act. In the years following the

passage of the Act, minority plaintiffs throughout the state

mounted successful challenges under Section 2 to at-large

election schemes for the federal and state legislative branches

and for local city councils and school boards. Thus, the face of

this state's legislative branch and of local government more and

more reflects the face of this state's people. By contrast, the

face of the judicial branch in Texas continues to be--as it has

always been-- overwhelmingly white.

The state of Texas and the other defendants argue that the

Voting Rights Act, so helpful to minorities in these other

contexts, affords minorities no relief in the context of the

election of state district judges. This is so, we are told,

because the state has a compelling interest in the maintenance of

the present electoral system--an interest which outweighs the

8

interest of minorities in having an opportunity equal to that of

the state's white citizens to elect district judges of their

choice. Specifically, we are told by the state that electing

district judges from an area no smaller than a county is

necessary to ensure that district judges are independent or

accountable to all litigants equally and that no particular group

will have undue influence over the decisions that must be made

alone by the district judge. We are told further that the

mechanism by which that interest is implemented is the state's

venue rules which operate to ensure the accountability of a state

district judge to all the citizens of the county in which he is

elected. Upon close inspection, we find, not surprisingly, that

the venue rules in Texas, like the venue rules in the federal

courts and in the courts of other states, are predicated on

considerations of convenience for the litigants and the

witnesses; in general, they afford a defendant some protection

from being forced to defend an action in a district court remote

from his residence in this vast state, or remote from the place

where the events underlying the controversy occurred and the

place where evidence is mos't likely available. In short, here as

elsewhere, the venue rules were not designed to ensure judicial

accountability.

What does ensure that state district judges are independent

and accountable to all litigants equally and that no particular

group will have undue influence over the decisions that must be

made are--first, the Texas Code of Judicial Conduct and second,

9

the integrity of the individual judges. The Texas Code of

Judicial Conduct charges judges with applying the law and states

that an honorable judiciary separated from the influence of

others is "indispensable to justice in our society." The Code

also stresses that "[a] judge should be unswayed by partisan

interest, public clamor, or fear of criticism." There is no

evidence in this record that judges elected with the support of

minorities will be any less obedient to the commands of the Texas

Code of Judicial Conduct than are state district judges who are

currently elected with the support of many other interest groups,

such as the personal injury bar and the defense bar. Nor is

there any support in this record for the proposition that persons

elected with the support of minorities would somehow be lacking

in the same high level of integrity that has in the past

characterized the Texas bench.

In summary, the compelling interest proffered by the state

and the other defendants for the maintenance of the current

system is, at best, little more than tenuous. Arrayed against it

is the Texas Constitution, which was amended by the Texas

legislature and by the voters of this state in 1985 to permit the

election of state district judges from areas smaller than a

county. The voters of this state have made provision for one of

the remedies available to the district court in this case--

namely, the remedy of subdistricting. Surely, the legitimate

state interests in this case can permissibly be defined, in part,

by this provision of its Constitution.

10

We turn finally to a brief summary of certain other

important legal issues involved in the decision of this case. In

particular, we have been asked by the state of Texas and several

state district judges to decide what Congress meant in the Voting

Rights Act when it prohibited voting practices that result in a

denial or abridgement of the right to vote "on account of race or

color."

With respect to the significance of Congress' use of the

phrase "on account of race" in Section 2, our holdings may be

summarized as follows: First, we hold that, under the plain

language of Section 2, minority plaintiffs must demonstrate that

the challenged election practice, under the totality of the

circumstances, results in the denial or abridgement of the right

to vote "on account of," or based on, race or color. See Chisom

v. Roemer. Ill S. Ct. 2345, 2363 (1991). The phrase "on account

of race or color" has been broadly defined by the Supreme Court

and by Congress. Specifically, the totality of circumstances

factors listed by Congress as relevant to a determination of

Section 2 liability, as well as the threshold factors for proving

vote dilution set forth in Thornburg v. Gingles. 478 U.S. 30

(1986), point to minority voters' unequal opportunity to

participate in the political process on the basis of race or

color. Thus, minority plaintiffs seeking to satisfy the "on

account of race or color" requirement --which is indisputably

their burden--may present evidence of the existence of racially

polarized voting, racial campaign appeals, a history of official

11

discrimination, the lingering socioeconomic effects of

discrimination, and other features of the current or past racial

climate of the community in question. Proof of some or all of

these factors raises an inference that racial discrimination is

responsible for minority plaintiffs' unequal opportunity to

participate in the political process.

Therefore, we reject the argument that "on account of race

or color" is a narrowly-defined phrase. In particular, we reject

the contention that Congress has defined the phrase "on account

of race or color" to require minority plaintiffs to present proof

that their unequal opportunity to participate in the electoral

process and elect representatives of their choice is "caused by

racial animus in the electorate." We also reject the related

argument that, to prove legally significant white bloc voting in

the context of partisan elections, as well as racially polarized

voting in such elections, minority plaintiffs must prove that

such voting patterns are caused by racial animus in the

electorate. While proof of the presence of racial animus in the

electorate would be a significant factor indicating that race or

color is in some way responsible for minority plaintiffs' unequal

opportunity to participate in the electoral process, the absence

of proof of racial animus in the electorate simply will not, by

itself, preclude a finding that minority plaintiffs have an

unequal opportunity to participate in the electoral process on

account of race or color.

12

We have also been asked to decide whether evidence of a

strong statistical correlation between the electoral success and

the party affiliation of a candidate can override or negate other

factors which Congress has indicated point towards vote dilution.

With respect to the evidence in several of the counties at issue

showing a strong statistical correlation between a candidate's

electoral success and his or her party affiliation, we hold that

the district court erred in refusing to consider the evidence.

The evidence is unquestionably relevant as an important feature

of the political landscape. And, to the extent the evidence

purported to demonstrate the absence of current racial animus in

the electorate, it was also relevant to the question of whether

race or color is responsible for the minority plaintiffs' unequal

opportunity to participate in the political process.

We further hold, however, that the district court's failure

to consider the particular evidence adduced in this case amounts

to harmless error. The so-called "partisanship evidence" in this

case was offered to demonstrate only that voters in elections in

large Texas counties, not knowing the race or names of district

court candidates, vote without specific racial animus toward

those candidates. The evidence did not purport to explain why

voters voted the way they did, but simply purported to rule out

specific racial animus towards candidates. Moreover, to the

extent that minority candidates find it harder, because of their

lack of financial resources, to mount a county-wide campaign on a

scale necessary to gain name recognition, the partisanship

13

evidence of straight-ticket voting reinforces rather than negates

minorities' unequal opportunity to participate in the political

process. Accordingly, we hold that, although it should not have

been excluded from consideration as legally irrelevant, the

partisanship evidence adduced here does not undercut the district

court's ultimate conclusion that minorities have an unequal

opportunity to participate in the political process, an unequal

opportunity that is tied to race or color.

I. BACKGROUND

This lawsuit, which is before this panel for a second time,

encompasses nine different voting rights cases. It concerns the

method by which Texas elects its district court judges in Bexar,

Dallas, Ector, Harris, Jefferson, Lubbock, Midland, Tarrant, and

Travis counties ("target counties"). Before we recount the

procedural history of this lawsuit, it will be helpful to outline

Texas' method of electing district court judges and to describe

how this method operates in the larger counties of the state.

A. Texas' Method of Electing District Court Judges

Texas elects its 386 state district judges in partisan

elections, which are conducted at the same time and in a

substantially similar fashion as other state partisan races.

Political parties nominate judicial candidates in general

primaries and runoffs, and a candidate must receive a majority of

the vote to qualify as the party's nominee. See Tex. Elec. Code

14

Ann § 172.003 (Vernon 1986). At the general election, judicial

candidates must run for a specifically numbered district court,

and their party affiliation is indicated on the ballot. To win

the general election, a judicial candidate needs only a plurality

of votes. Id. § 2.001.

One feature of Texas' method of electing state district

judges is unique--the size of the various judicial districts from

which such judges are elected. Since 1985, the Texas

Constitution has provided that judicial districts may not be

smaller than a county unless a majority of the voters of the

county authorizes smaller districts, see Tex. Const, art. V, §

7a(i), and to date, no district smaller than one county has been

authorized by voters from any Texas county.2 In addition,

although the Texas Constitution permits the creation of more than

one judgeship per judicial district, see Tex. Const, art V, § 7,

the legislature has seldom invoked this provision. Consequently,

as a general rule only one district judge is elected per judicial

district, and the judicial districts, although no smaller than a

county, vary in size from one county to six counties and in

population from approximately 1 3 , 0 0 0 to 2 . 5 million. See

generally The American Bench 2 1 3 8 - 5 4 (6th ed. 199 1) (breaking down

judicial districts in Texas according to the counties they

cover).

2 Stated another way, the Texas Constitution was amended in

1985 to provide for the first time that a county may subdivide

itself into smaller judicial districts than the full extent of

the county; such action requires a majority vote of the county.

15

Thus, Texas' method of electing district court judges

operates as an at-large system in the larger counties--including

the nine target counties--but not in the smaller counties- For

example, in Harris County, which according to the 1980 Census has

a population of some 2,409,544, there are fifty-nine (59)

overlapping, single-judge, county-wide judicial districts. The

persons running for those 59 positions may be voted on by all

1,685,024 registered voters in Harris County. By contrast, in

Milam County, which according to the 1980 Census has a population

of 22,732, there is only one judicial district. The registered

voters in that county cast their ballots for only one district

judge. See id.

B. Procedural History

On July 11, 1988, ten individuals, along with local and

state chapters of the League of United Latin American Citizens

(collectively, "Plaintiffs"), filed suit in federal district

court, seeking declaratory and injunctive relief. Plaintiffs

asserted that Texas' method of electing district court judges, as

that method operates in larger counties, (1) dilutes minority

voting strength in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act, and (2) violates the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments of

the United States Constitution. The named defendants in the

original lawsuit were: William P. Clements, the Governor of

Texas; Jim Mattox, the Attorney General of Texas, who is charged

with enforcing the laws of the state; George Bayoud, the

16

Secretary of State of Texas, who is charged with administering

the elections laws of the state; and members of the Judicial

Districts Board of Texas, which is charged with reapportioning

the districts from which Texas district court judges are elected

(collectively, "State Defendants").

Several months later, in March 1989, the district court

permitted several parties to intervene in the lawsuit. The

Houston Lawyers Association and the Texas Black Legislative

Caucus intervened on behalf of Plaintiffs, as did certain

individuals residing in Dallas County. Two Texas district court

judges--Sharolyn Wood, 127th District Court in Harris County, and

Harold Entz, 194 th District Court in Dallas County-- intervened in

their personal capacities on behalf of the State Defendants.

Plaintiffs originally challenged Texas' election method in

forty-four counties. By the time of trial, however, they had

narrowed their challenged to the nine target counties.

Plaintiffs proceeded on behalf of Black voters in Harris, Dallas,

Tarrant, and Jefferson counties, on behalf of Hispanic voters in

Bexar and Travis counties, and on behalf of Black and Hispanic

voters combined in Lubbock, Ector, and Midland counties.

The lawsuit was tried to the district court the week of

September 18, 1989. After considering all the evidence,

including much expert testimony, the district court rendered its

liability decision and made findings of fact and conclusions of

law. In its 94-page memorandum opinion of November 8, 1989, the

district court rejected the Plaintiffs' constitutional claims but

17

found their statutory claim meritorious. The district court

concluded that the Plaintiffs, on behalf of specified minority

voters in each of the nine target counties, demonstrated a

violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The district

court based its conclusion on its finding that Texas' current

method of electing district court judges in the nine target

counties "interacts with social and historical conditions" to

cause the minority voters in each of the nine counties to have

less opportunity than white voters "to elect their preferred

candidates."

On appeal, a divided panel of this court held that the

district court erred in concluding that Texas' method of electing

district court judges violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

in the nine target counties. See League of United Latin American

Citizens v. Clements. 902 F.2d 293 (5th Cir.), opinion on

rehearing en banc. 914 F.2d 620 (1990), rev'd and remanded. Ill

S. Ct. 2367 (1991). We reasoned that, although Section 2 applies

to some state judicial elections, it does not apply to elections

of state district judges. Id. at 308. In reaching this

decision, we focused specifically on the legislative history of

the Voting Rights Act, as amended in 1982, and the nature of

Texas district court judgeships. We noted that, unlike a judge

of a multi-member body, "the district judge in Texas does his

judging alone." Id. Because we concluded that "there can be no

share of such a single member office," we held that county-wide

elections of district judges "[do] not violate the Voting Rights

18

Act." Id. Accordingly, we reversed the judgment of the district

court.

On its own initiative, the members of this court decided to

rehear the case en banc. Over Judge Johnson's dissent, a

majority of this court concluded that Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act does not apply to any judicial elections. See League

of United Latin American Citizens. 914 F.2d 620, 631 (5th Cir.

1990) (en banc), rev'd and remanded. Ill S. Ct. 2367 (1991). In

reaching this conclusion, the majority relied primarily on

Congress' use of the word "representative" in Section 2. It

reasoned that Congress did not intend the term "representative"

to include state judges. The majority stated: "Should Congress

seek to install [the results] test for judicial elections, it

must say so plainly. Instead, it has thus far plainly said the

contrary." Id.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari for the limited purpose

of considering the scope of Section 2's coverage. See Houston

Lawyers' Ass'n v. Attorney General of Texas. Ill S. Ct. 2376,

2380 (1991). Relying on its decision in Chisom v, Roemer. Ill S.

Ct. 2354 (1991), which was issued the same day, the Court

concluded that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act applies to

Texas' method of electing district court judges. Id. at 2381.

The Court specifically held that " [i]f a State decides to elect

its trial judges, as Texas did in 1861, those elections must be

conducted in compliance with the Voting Rights Act." Id. at

19

2380. Accordingly, the Court reversed this circuit's en banc

decision and remanded the case for further proceedings.

II. THE ACCEPTED FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYZING SECTION 2

VOTE DILUTION CLAIMS

When Congress amended Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act in

1982, it sought "to clearly establish the standards . . . for

proving a violation of that section." S. Rep. No . 417, 97th

Cong., 2d Sess. 6, at 2 (1982), reprinted in 1982 U.S.C.C.A.N.

177, 178 [hereinafter S. Rep.].3 Congress specifically intended

to "make clear that proof of discriminatory intent is not

required to establish a violation of Section 2." S. Rep. at 2.

Congress also intended to restore "the legal standards under the

results test by codifying" the vote dilution framework embraced

in White v. Regester. 412 U.S. 755 (1973). Id. at 2.

As amended, Section 2 establishes the basic framework for

analyzing vote dilution claims. It provides:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting

or standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or applied by any State or political subdivision in a

manner which results in a denial or abridgement of the

right of any citizen of the United States to vote on

account of race or color, or in contravention of the

3 The Senate Report is the authoritative expression of

Congress' intent in amending Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

The House of Representatives did not draft its own report, nor

did it negotiate a conference committee report. The House

instead adopted the language of the Senate Report. Therefore,

the Senate Report serves in place of a conference committee

report and should be considered, next to the statute itself, the

most persuasive evidence of congressional intent. See generally Thornburg v. Gingles. 478 U.S. 30, 43-46 (1986).

20

guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2) of this title,

as provided in subsection (b) of this section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section is

established if, based on the totality of the

circumstances, it is shown that the political processes

leading to nomination or election in the State or

political subdivision are not equally open to

participation by members of a class of citizens protected by subsection (a) of this section in that its

members have less opportunity than other members of the

electorate to participate in the political process and

to elect representatives of their choice. The extent

to which members of a protected class have been elected

to office in the State or political subdivision is one

circumstance which may be considered: Provided. That

nothing in this section establishes a right to have

members of a protected class elected in numbers equal

to their proportion in the population.

42 U.S.C. § 1973. Subsection (a) makes clear that Congress

intended to codify a results test, and subsection (b) provides

guidance about how the results test is to be applied. See

Chisom. Ill S. Ct. at 2364. Under this framework, then, a

plaintiff can prevail "by showing that a challenged election law

or procedure, in the context of the total circumstances of the

local electoral process, ha[s] the result of denying a racial or

language minority an equal chance to participate in the electoral

process." S. Rep. at 16.

The basic framework set forth in the language of Section 2,

although it appears straightforward, has become increasingly

complex. Both the Supreme Court and Congress have elaborated on

this basic structure, and the product of their elaborations is a

two-part framework for analyzing vote dilution claims brought by

minority voters. Under the first part of this accepted Section 2

framework, a court must determine whether the minority voters

21

have satisfied a threshold test enunciated by the Supreme Court.

If minority voters satisfy the threshold test and demonstrate

that their ability to elect representatives of their choice is

being hindered by the challenged practice, a court must then ask

whether the minority voters have demonstrated certain factors

that Congress deemed relevant to the Section 2 inquiry--factors

that raise an inference of vote dilution. Ultimately, a court

must inquire whether minority voters have demonstrated an unequal

opportunity to participate in the political process on account of

race or color.

A. The Threshold Inquiry: The Gingles Factors

The Supreme Court first elaborated on the basic analytical

framework established by Section 2 in Thornburg v. Ginales. 478

U.S. 30 (1986), a case in which Black voters successfully

challenged North Carolina's multimember legislative redistricting

plan. Although the case produced a "complicated web of dissents,

concurrences, and plurality opinions,"4 a majority of the Court

agreed that at-large election procedures do not automatically

violate Section 2. Id. at 46. A majority of the Court also

agreed with the formulation of a three-part, threshold test for

analyzing claims that an at-large election scheme dilutes

minority voting strength. Under this threshold test, the

minority group challenging an at-large election scheme must

4 Sushma Soni, Note, Defining the Minority-Preferred

Candidate Under Section 2. 99 Yale L.J. 1651, 1653 (1990) .

22

demonstrate that (1) it is sufficiently large and geographically

compact to constitute a majority in a single member district, (2)

it is politically cohesive, and (3) the white majority votes

sufficiently as a bloc to enable it--in the absence of special

circumstances--usually to defeat the minority's preferred

candidate. Id. at 48-51. Failure to establish any one of the

Ginales factors precludes a finding of vote dilution, because

"[t]hese circumstances are necessary preconditions for

multimember districts to operate to impair minority voters'

ability to elect representatives of their choice. . . . " Id. at

50; see also Overton v. City of Austin. 871 F.2d 529, 538 (5th

Cir. 1989) (failure to establish any one of the Ginales factors

is fatal to plaintiffs' vote dilution claim).

1. Size and Geographical Compactness of the Minority Group

As stated above, to pass the Ginales threshold inquiry, the

minority group challenging an at-large election scheme must first

demonstrate that it is sufficiently large and geographically

compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district. To

satisfy this first Ginales factor, the minority group must

ordinarily be able to draw a single member district in which a

majority of the voting age population is minority. See Westweao

Citizens for Better Government v. City of Westweao. 946 F.2d

1109, 1117 n.7 (5th Cir. 1991) (Westweao III): Overton. 871 F.2d

at 536; see also Westweao Citizens for Better Gov't v. Westweao.

872 F.2d 1201, 1205 n.4 (5th Cir. 1989) (Westweao I) (noting that

evidence of size of "voting age" population is critical to a vote

23

dilution claim); Romero v. City of Pomona. 883 F.2d 1418, 1426

(9th Cir. 1989) ("eligible minority voter population, rather than

total minority population, is the appropriate measure of

geographical compactness"). This requirement, according to the

majority in Gingles, ensures that, in the absence of the

multimember district and at-large voting scheme, "minority voters

possess the potential to elect representatives. . . . " Gingles.

478 U.S. at 50 n.17 (emphasis in original). In other words, if

the minority group is not sufficiently large and geographically

compact, "the multimember form of the district cannot be

responsible for [minority] voters' inability to elect [their]

candidates." Id. at 50 (emphasis in original) (footnote

omitted).

2. Political Cohesiveness of the Minority Group

The minority group must also demonstrate that it is

"politically cohesive" to pass the Gingles threshold inquiry.

Id. at 51. One way of proving political cohesiveness, according

to the Gingles majority, is to show "that a significant number of

minority group members usually vote for the same candidates. . .

." Id. at 56; see also Citizens for a Better Gretna v. City of

Gretna. 834 F.2d 496, 501-02 (5th Cir. 1987), cert, denied. 492

U.S. 905 (1989). If the minority group is not politically

cohesive, or does not engage in significant bloc voting, "it

cannot be said that the selection of a multimember structure

thwarts distinctive minority group interests." Gingles. 478 U.S.

at 51 (citation omitted).

24

Although statistical evidence of racially polarized voting,

see infra Part II.B.l.b., is frequently employed to demonstrate a

minority group's political cohesiveness, other evidence may also

establish this second Ginales factor. We have on several

occasions indicated that Ginales allows minority voters to prove

their political cohesiveness even in the absence of statistical

evidence of racial polarization. See Westweao III. 946 F.2d at

1118 n .12; Brewer v. Ham. 876 F.2d 448, 453 (5th Cir. 1989). In

particular, political cohesiveness also may be demonstrated by

testimony from persons familiar with the community in question,

provided that such testimony is reinforced with other evidence or

is not otherwise rebutted. See Brewer. 876 F.2d at 453-54; see

also Overton. 871 F.2d at 536.

Political cohesiveness is related to, but distinct from, the

concept of racially polarized voting. The notion of political

cohesiveness contemplates that a specified group of voters shares

common beliefs, ideals, principles, agendas, concerns, and the

like such that they generally unite behind or coalesce around

particular candidates and issues. See Monroe v. City of

Woodville. 881 F.2d 1327, 1331 (5th Cir. 1989), modified. 897

F.2d 763, cert, denied. Ill S. Ct. 71 (1990). The term racially

polarized voting, on the other hand, describes an electorate in

which white voters favor and vote for certain candidates or

propositions, and minority voters vote for other candidates or

propositions. See Ginales. 478 U.S. at 53 n.21. (racial

polarization exists where there is a consistent relationship

25

between the race of the voter and the way in which the voter

votes or where minority voters and white voters vote

differently). Thus, while a showing of racially polarized voting

will frequently demonstrate that minority voters are politically

cohesive,5 a showing that minority voters are politically

cohesive will not, by itself, establish racially polarized

voting.

Finally, according to a majority of the Justices in Gingles.

to satisfy the second threshold factor minority voters need not

prove that the reason they vote for the same candidates is linked

to race or color. Justice Brennan, writing for three other

Justices, would have held that "the reasons [minority] and white

voters vote differently have no relevance to the central inquiry

of § 2." Gingles. 478 U.S. at 63 (Brennan, J., joined by

Marshall, Blackmun, and Stevens, JJ.). Although not entirely

agreeing with Justice Brennan, Justice O'Connor, writing on

behalf of three other Justices, agreed that defendants cannot

rebut statistical evidence of a minority group's political

cohesiveness by "offering evidence that the divergent racial

voting patterns may be explained in part by causes other than

race." Gingles, 478 U.S. at 100 (O'Connor, J., joined by

Burger, C.J., Powell and Rehnquist, JJ., concurring in the

5 Evidence of racially polarized voting does not, however,

automatically establish minority political cohesiveness. If, in

a certain community, white citizens vote only for candidates of

type A, while minority citizens are split in voting for

candidates of types X, Y, and Z, then there would be evidence of

racially polarized voting--minority and white voters voting

differently--but no evidence of minority political cohesiveness.

26

judgment). Justice O'Connor specifically stated that statistical

evidence of divergent racial voting offered solely to establish

the minority group's political cohesiveness may not be rebutted

by evidence indicating that there is "an underlying divergence in

the interests of minority and white voters." Id.

3. Legally Significant White Bloc Voting

Under the third Gingles factor, the minority group "must be

able to demonstrate that the white majority votes sufficiently as

a bloc to enable it--in the absence of special circumstances,

such as the minority candidate running unopposed--usually to

defeat the minority's preferred candidate." Gingles. 478 U.S. at

51 (internal references omitted). "In establishing this last

circumstance, the minority group demonstrates that submergence in

a white multimember district impedes its ability to elect its

chosen representatives." Id. As with demonstrating political

cohesiveness, a minority group can demonstrate white bloc voting

by introducing statistical evidence of racially polarized voting.

See Westwego III. 946 F.2d at 1118. Moreover, where statistical

evidence of racially polarized voting is used to establish white

bloc voting, the elections that will usually be most probative

are those in which the minority-preferred candidate is a member

of the minority group. See Westwego I. 872 F.2d at 1208 n.7.

The determinative question for this third Gingles factor "is

not whether whites generally vote as a bloc, but rather, whether

such bloc voting is legally significant." Monroe. 881 F.2d at

1332. Legally significant white bloc voting means white bloc

27

voting that usually defeats the minority group's preferred

candidate. Id. at 1333. As the Court recognized in Ginqles. "a

white bloc vote that normally will defeat the combined strength

of minority support plus white 'crossover' votes rises to the

level of legally significant white bloc voting." Ginqles. 478

U.S. at 56. It is "the usual predictability of the majority's

success," the Court continued, that "distinguishes structural

dilution from the mere loss of an occasional election." Id. at

51.

The amount of white bloc voting that rises to the level of

legal significance will vary from location to location. That is,

in determining whether white voting strength can generally

"minimize or cancel" minority voters' ability to elect

representatives of their choice, courts must look at a number of

factors. Id. at 56 (quoting S. Rep. at 28) . Among the factors

affecting the level of legally significant white bloc voting are:

(1) the nature of the allegedly dilutive electoral mechanism; (2)

the presence or absence of other potentially dilutive electoral

devices, such as majority vote requirements, designated posts,

and prohibitions against bullet voting; (3) the percentage of

registered voters in the district who are members of the minority

group; (4) the size of the district; and (5) in multimember

districts, the number of seats open and the number of candidates

in the field. Ginqles. 478 U.S. at 56.

Contrary to the arguments advanced by the State Defendants,

Judge Wood, and Judge Entz, a minority group is not required to

28

demonstrate that racial animus is responsible for a white bloc

voting pattern. A requirement of demonstrating racial animus

would, in the words of the Senate Report, be "unnecessarily

divisive because it [would] involve charges of racism on the part

of . . . entire communities." S. Rep. at 36. And, one of the

reasons Congress decided to amend Section 2 was to obviate the

need for such charges of racism. Id.* 6

6 Judge Higginbotham contends that five Justices in Gingles expressly held that the extent to which voting patterns are

attributable to causes other than racial political considerations

is an integral part of the racial bloc voting inquiry.

Dissenting Op. at 30-31. Indeed, in Judge Higginbotham's view,

the failure to demonstrate racial political considerations, or racial animus, in the electorate automatically defeats a vote

dilution claim, because the minority group will not be able to

demonstrate either legally significant white bloc voting or

racially polarized voting. After a careful reading of Gingles, we respectfully disagree.

We recognize that Justice O'Connor, in her Gingles

concurrence, disagreed with Justice Brennan's position that

explanations of divergent racial voting patterns are "irrelevant"

to the Section 2 inquiry. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 100 (O'Connor,

J-, joined by three Justices, concurring in the judgment). In

expressing her views on the use of statistical evidence to demonstrate racially polarized voting, however, she never

"expressly held" that racial political considerations are an

"integral part," much less a prerequisite, to a finding of racial bloc voting. Rather, she stated:

Insofar as statistical evidence of divergent racial

patterns is admitted solely to establish that the

minority group is politically cohesive and to assess

its prospects for electoral success. I agree that

defendants cannot rebut this showing by offering

evidence that the divergent racial voting patterns may

be explained in part by causes other than race, such as

an underlying divergence in the interests of minority

and white voters. I do not agree, however, that such

evidence can never affect the overall vote dilution

inquiry. Evidence that a candidate preferred by the

minority group in a particular election was rejected by

white voters for reasons other than those which made

that candidate the preferred choice of the minority

group would seem clearly relevant in answering the

29

question whether bloc voting by white voters will

consistently defeat minority candidates. Such evidence

would suggest that another candidate, equally preferred

by the minority group, might be able to attract greater

white support in future elections.

I believe Congress also intended that explanations

of the reasons why voters rejected minority candidates

would be probative of the likelihood that candidates

elected without decisive minority support would be

willing to take the minority's interests into account.

In a community that is polarized along racial lines,

racial hostility may bar these and other indirect

avenues of political influence to a much greater extent

than in a community where racial animosity is absent

although the interests of the racial groups diverge.

Indeed, the Senate Report clearly stated that one

factor that could have probative value in § 2 cases was

"whether there is a significant lack of responsiveness

on the part of elected officials to the particularized

needs of the members of the minority group. S. Rep.,

at 29. The overall vote dilution inquiry neither

requires nor permits an arbitrary rule against

consideration of all evidence concerning voting

preferences other than statistical evidence of racial

voting patterns. Such a rule would give no effect

whatever to the Senate Report's repeated emphasis on "intensive racial politics," on "racial political

considerations," and on whether "racial politics . . .

dominate the electoral process" as one aspect of "the

racial bloc voting" that Congress deemed relevant to

showing a § 2 violation. Id. at 33-34. Similarly, I

agree with Justice White that Justice Brennan's

conclusion that the race of the candidate is always

irrelevant in identifying racially polarized voting

conflicts with Whitcomb and is not necessary to the disposition of this case.

478 U.S. at 100-01 (emphasis added).

How this passage amounts to, as Judge Higginbotham states,

an "express holding" that racial political considerations are an

integral part of, or a prerequisite to, a finding of racially

polarized voting is not clear. A straightforward reading of this

passage, in our view, suggests that Justice O'Connor would

consider relevant anecdotal testimony indicating that, "in a

particular election," white voters rejected a minority-preferred

candidate for "reasons other than those which made that candidate

the preferred choice of the minority group." Such anecdotal

testimony would be relevant, in Justice O'Connor's words, to

"suggest that another candidate, equally preferred by the

minority group," might be able to attract greater white support

30

in the future. By making this statement, Justice O'Connor

recognized that the phenomenon of white bloc voting, as well as

racially polarized voting, is only significant if it persists

over time. Moreover, she also indicated that "explanations of

the reasons why voters rejected minority candidates" would be

probative of the totality of circumstances factor relating to the

"responsiveness of elected officials." See infra Part II.B.l.h.

Finally, Justice O'Connor recognizes that in a community

"polarized along racial lines," the added circumstance of "racial

hostility" may bar even "indirect avenues of political influence

to a much greater extentf than in a community where racial

animosity is absent although the interests of racial groups

diverge." Thus, when read in context, Justice O'Connor's Ginales

opinion is much more consistent with our treatment of racial

political considerations, or racial animus in the electorate, as

an "other factor" that is relevant to the "overall vote dilution

inquiry." rather than as a prerequisite to a finding of legally

significant white bloc voting. 478 U.S. at 101-02 (emphasis

added).

Finally, we note that Judge Higginbotham in another portion

of his dissent appears to reject the idea that a minority group

must demonstrate that racial animus is responsible for a white

bloc voting pattern. Judge Higginbotham concedes that it would

be unworkable to require plaintiffs to prove the absence of all

non-racial causes of voting behavior in order to demonstrate

legally significant white bloc voting. However, he clings to the

idea that evidence of partisan voting is somehow different from

other evidence suggesting the presence or absence of racial

political considerations or of racial animus in the electorate.

This differentiation between partisanship evidence and other

evidence is patently illogical. First, this approach would

appear to prevent an inquiry into the many reasons why people

vote for the candidates of one party or another. Second, if

evidence of partisan voting is sufficient to defeat a finding of

white block voting, why not other evidence suggesting the absence

of racial political considerations? If, as Justice O'Connor

suggests, the reasons why people vote the way they do are

relevant to the overall vote dilution inquiry, how can one stop

that inquiry at statistical correlations between the party

affiliations of the candidates and electoral success? Indeed,

why would such a rule not amount to an "arbitrary rule" against

consideration of all evidence concerning voting preferences

similar to the rule condemned by Justice O'Connor? Ultimately,

Judge Higginbotham's approach would needlessly confuse the narrow

Gingles factors with the broader inquiry into the totality of the

circumstances. The logical solution is to follow the approach

mandated by Congress and adopted by Justice O'Connor, i.e., to

consider evidence suggesting that divergent voting patterns are

not the result of racial political considerations in the totality of circumstances inquiry.

31

In sum, a minority group can satisfy the third Gingles

factor by showing that a substantial majority of white voters

consistently vote against the candidates preferred by minority

voters, such that the candidates preferred by the minority group

usually lose. It has never been the case, however, that for

white bloc voting to be legally significant, it must be shown to

be motivated by racial animus. See e.g.. Westwego III. 946 F.2d

at 1118-20 (concluding, without inquiring as to the cause of

voting patterns, that the record "unmistakably" demonstrated

legally significant white bloc voting). We decline to hold so

now.

B. The Broader Inquiry: The Totality of the Circumstances

Satisfaction of the Gingles factors, at least in this

circuit, does not by itself establish a violation of Section 2.

See Westwego III, 946 F.2d at 1116. The minority group must

further demonstrate that, under the totality of the

circumstances, "its members have less opportunity than other

members of the electorate to participate in the political process

and to elect representatives of their choice." 42 U.S.C. §

1973(b). Unlike the Gingles threshold inquiry, the totality of

circumstances inquiry is broad. It requires courts to make a

"searching practical evaluation of the 'past and present

reality'" of the community and to take a "'functional' view of

the political process." Gingles. 478 U.S. at 45. Although

courts typically should be guided by the factors mentioned in the

32

Senate Report accompanying the 1982 amendments to Section 2,

other factors may also be relevant. See Westwego III. 946 F.2d

at 1120.

1. The Senate Report Factors

The Senate Report accompanying the 1982 amendments to

Section 2 identifies seven "typical" factors and two "additional"

factors that may be relevant to an analysis of the totality of

the circumstances. These factors, which were derived from the

analytical framework used by the Supreme Court in White v.

Regester. 412 U.S. 755 (1973), as articulated by this court in

Zimmer v. McKeithen. 485 F.2d 1297, 1305 (5th Cir. 1973), af f * d

sub nom. East Carroll Parish School Bd. v. Marshall. 424 U.S. 636

(1976), are meant to aid a court in assessing whether "the

challenged system or practice, in the context of all the

circumstances in the jurisdiction in question, results in

minorities being denied equal access to the political process."

S. Rep. at 27. According to the Senate Report, a court must

"assess the impact of the challenged structure or practice on the

basis of objective factors, rather than making a determination

about the motivations which lay behind its adoption or

maintenance." Id. at 27 (emphasis added).

a. History of discrimination touching the rights of

minorities to participate in the political process. The first

factor mentioned in the Senate Report is "the extent of any

history of official discrimination in the state or political

subdivision that touched the right of the members of the minority

33

group to register, to vote, or otherwise to participate in the

democratic process." S. Rep. at 28. In listing this factor,

Congress made clear that it "was concerned not only with present

discrimination, but with the vestiges of discrimination which may

interact with present political structures to perpetuate a

historical lack of access to the political system." Westwego I.

872 F.2d at 1211-12. Evidence that is relevant under this factor

includes the use of poll taxes and literacy tests, as well as the

existence of racially segregated schools and public facilities.

See White. 412 U.S. at 768; Zimmer. 485 F.2d at 1306; see also

Andrew P. Miller and Mark A. Packman, Amended Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act: What is the Intent of the Results Test?. 36

Emory L.J. 1, 28 (19 87) .

b. Extent of racially polarized voting. The second factor

that Congress deemed relevant to an analysis of the totality of

the circumstances is "the extent to which voting in the elections

of the state or political subdivision is racially polarized." S.

Rep. at 29. This factor is one of the two most important in the

inquiry into the past and present reality of the challenged

electoral structure. Westwego III. 946 F.2d at 1120. It is, we

have stated, "the linchpin of a § 2 vote dilution claim. . . . "

Gretna. 834 F.2d at 499; see also Samuel Issacharoff, Polarized

Voting and the Political Process: The Transformation of Voting

Rights Jurisprudence. 90 Mich. L. Re v. 1833, 1848-49 (1990)

(opining that the inclusion of the racially polarized voting

inquiry in the Senate Report marked "a major shift in voting

34

rights law" and pointed to an "emerging doctrinal coherence for

claims of minority vote dilution").

As previously discussed, see supra Part II.A.2, racially

polarized voting "exists where there is a 'consistent

relationship between [the] race of the voter and the way in which

the voter votes,' . . . or to put it differently, where

'[minority] voters and white voters vote differently.'" Gingles,

478 U.S. at 53 n.21. Racially polarized voting is not, as Judge

Wood, Judge Entz, and the State Defendants suggest, racially

motivated voting, or voting caused by racial animus.7 See

7 Although the ultimate inquiry in a Section 2 case is

whether minority voters have an unequal opportunity to

participate in the political process on account of race or color.

see infra Part II.C., we decline to redefine the concept of

racially polarized voting to include a causation element. To

establish racially polarized voting, a minority group need not

prove that divergent racial voting patterns are motivated or

caused by racial animus in the electorate. Moreover, we decline

to hold that a multivariate analysis--i.e., an analysis that

investigates more variables than the race of the voters--is necessary to show racially polarized voting. In our view, such a

definition would be inconsistent with Congress' intent in

amending Section 2 and directing courts to "assess the impact of

the challenged structure or practice on the basis of objective

factors. rather than making a determination about the motivations

which lay behind its adoption or maintenance." S. Rep. at 27

(emphasis added). See generally. Richard L. Engstrom, The

Reincarnation of the Intent Standard: Federal Judges and At-

Large Election Cases. 28 How. L.J. 495, 498 (1985) (disapproving

the recent trend in federal courts to give a "second life" to the

intent requirement); cf. Kirksev v. City of Jackson. 663 F.2d

659, 662 (5th Cir. Unit A Dec. 1981) (holding that, because of

First Amendment concerns, the motivations of voters are not

subject to searching scrutiny by plaintiffs in a voting rights

case), clarified. 669 F.2d 316 (1982).

In refusing to redefine the concept of racially polarized

voting, however, we do not mean to say that evidence of the

presence or absence of racial animus in the electorate is

irrelevant to the totality of circumstances inquiry. See infra Part II.B.2.

35

Collins v. City of Norfolk. 816 F.2d 932, 935 (4th Cir. 1987)

("The legal standard for the existence of racially polarized

voting looks only to the difference between how majority votes

and minority votes were cast; it does not ask why those votes

were cast the way they were. . . Nor is racially polarized

voting simply "the tendency of citizens to vote for candidates of

their own race." Miller & Packman, supra. at 16. Rather,

racially polarized voting is an objective factor, which is

established by evidence demonstrating that "voters vote along

racial lines." Westwego III. 946 F.2d at 1122.

To say that racial polarization does not simply measure the

tendency of citizens to vote for candidates of their own race,

however, does not mean that evidence of such tendencies are

unimportant to the racial polarization inquiry. We recognized in-

Gretna that, in determining the existence of racial bloc voting,

"the race of the candidate is in general of less significance

than the race of the voter--but only within the context of an

election that offers voters the choice of supporting a viable

minority candidate." 834 F.2d at 503. Furthermore, we have

noted that "the evidence most probative of racially polarized

voting must be drawn from elections including both [minority] and

white candidates." Westwego I. 872 F.2d at 1208 n.7.*

* In his dissent, Judge Higginbotham, citing our opinion in

Gretna. suggests that the reason elections with a minority

candidate are most probative of racially polarized voting is

because we are trying to determine whether such voting is caused

by racial animus in the electorate. See Dissenting Op. at 33.

We disagree. Our decision in Gretna indicates that the reason

for focusing on these elections is --generally-- to ensure that we

36

Accordingly, in ascertaining whether a community's elections are

characterized by racially polarized voting, a court may properly

give more weight to elections in which the minority-preferred

candidate is a member of the minority group.

The Senate Report recognizes that racially polarized voting

is a relative concept by instructing courts to assess not only

the existence of racially polarized voting, but the extent of

such voting. Indeed, the existence of racially polarized voting

will frequently, if not always, be established by satisfying of

the second and third Gingles factors. See supra Parts II.A.2.,

II.A.3; see also Romero v. City of Pomona. 883 F.2d 1418, 1423

(9th Cir. 1989) (suggesting that the second and third Gingles

factors, political cohesiveness and white bloc voting, are the

"component parts" of racially polarized voting). Under the

totality of circumstances inquiry, the focus is on the degree of

racially polarized voting. When the pattern of racially

polarized voting is severe--that is, when minority and white

voters rarely engage in cross-over voting--an at-large election

scheme is more likely to dilute minority voting strength in

violation of Section 2. Conversely, when the pattern of racially

polarized voting is slight, and there is substantial cross-over

voting between minority and with voters, an at-large election

are considering elections "that offer[] voters the choice of

supporting a viable minority candidate," 834 F.2d at 503, or more

specifically, a minority candidate that is preferred by the minority group.

37

scheme is less likely to dilute minority voting strength in

violation of Section 2.

c. Use of voting practices that enhance the opportunity for

discrimination. The Senate Report also directs courts to

consider other voting practices that may interact with the

challenged election scheme to dilute minority voting strength.

In particular, courts are to consider "the extent to which the

state or political subdivision has used unusually large election

districts, majority vote requirements, anti-single shot

provisions, or other voting practices or procedures that may

enhance the opportunity for discrimination against the minority

group." S. Rep. at 29. Courts may also consider, at least in

the context of at-large elections, whether the state or political

subdivision employs what amounts to a numbered-post system and

whether the system lacks a district residency requirement. See

White v. Regester. 412 U.S. 755, 766 (1973) (discussing Texas'

"place" rule). The potential of such features to dilute minority

voting strength is well-documented. See generally Chandler

Davidson, Overview, in Minority Vote Dilution 5-8 (Chandler

Davidson ed. 1984).

Unusually large election districts may enhance vote dilution

in a least two ways: First, such districts may make it more

difficult for minorities to successfully campaign for office.

See Rogers v. Lodge. 458 U.S. 613, 627 (1982); see also Whitcomb

31=_Chavis. 403 U.S. 124, 143 (1971) (recognizing that, when

large, multimember districts have an enhanced tendency to

38

minimize or cancel out minority voting strength). Such districts

may also create the problem of overly long ballots, making "an

intelligent choice among candidates . . . quite difficult."

Lucas v. Colorado Gen. Assembly. 377 U.S. 713, 731 (1964).

The other features discussed above similarly enhance the

possibility of vote dilution. Majority vote requirements can

obstruct the election of minority candidates by giving white

voting majorities a "second shot" at minority candidates who have

only mustered a plurality of the votes in the first election.

See Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Constitutional Rights of the

Senate Comm, on the Judiciary. 94th Cong., 1st Sess. 491 (1975)

(testimony of Dr. Charles Cotrell); see also Jones v. City of

Lubbock. 727 F.2d 364, 383 (5th Cir. 1984); Manor v. Treen. 574

F. Supp. 325, 351 n.32 (E.D. La. 1983) (three-judge court).

Anti-single shot provisions prohibit voters from casting fewer

than all of their votes and effectively force minority voters to

cast votes for white candidates who may not be favored by

minority voters. Westwego III. 946 F.2d at 1113 n.3. Under a

numbered post system, candidates are required to run for a

designated seat. See White. 412 U.S. at 766. This requirement,

the Supreme Court has recognized, "enhances [the minority

group's] lack of access because it prevents a cohesive political

group from concentrating on a single candidate." Rogers. 458

U.S. at 627. Finally, where there is no requirement that

candidates reside in subdistricts of a multimember district, "all

39

candidates may be selected from outside [a minority group's]

residential area." White, 412 U.S. at 766 n.10.

d. Minority access to the slating process. The fourth

totality factor listed in the Senate Report is "whether members

of the minority group have been denied access" to any candidate

slating process. S. Rep. at 29. Slating has been defined as

"the creation of a package or slate of candidates, before filing

for office, by an organization with sufficient strength to make

the election merely a stamp of approval of the pre-ordained

candidate group." Overton. 871 F.2d at 534. The core inquiry as

to slating, we have stated, "is the ability of [minorities] to

get on the ballot." Hendrix v. Joseph, 559 F.2d 1265, 1268 (5th

Cir. 1977).

Where a slating organization exists, "the ability of

minorities to participate in that slating organization and to

receive its endorsement may be of paramount importance." United

States v. Marenao Countv Comm'n, 731 F.2d 1546, 1569 (11th Cir.)

(Wisdom, J., sitting by designation), cert, denied, 469 U.S. 976

(1984). We have indicated, however, that a slating

organization's endorsement of a few minority candidates will not

preclude a finding that the minority group lacks access to the

slating process, at least where those candidates are not

preferred by the minority group. Seg Velasquez v_.— City of

Abilene. 725 F.2d 1017, 1022 & n.l (5th Cir. 1984) (referring to

the Senate Report). Moreover, we have recognized that the

absence of a slating organization will not mitigate evidence of

40

an unequal opportunity to participate in the political process.

See McMillan v . Escambia Countv. 638 F.2d 1239, 1245 (5th Cir.),

cert, dismissed. 453 U.S. 946 (1981).

e. Lingering socioeconomic effects of discrimination.

Congress also has directed courts to consider "the extent to

which members of the minority group in the state or political

subdivision bear the effects of discrimination in such areas as

education, employment and health . . . ." S. Rep. at 29. In

doing so, Congress recognized that the lingering socioeconomic

effects of discrimination may hinder a minority group's "ability

to participate effectively in the political process." Id. Where

the minority group presents evidence that its members are

socioeconomically disadvantaged and that their level of

participation in politics is depressed, the group "need not prove

any further causal nexus between [its members') disparate

socioeconomic status and the depressed level of political

participation." Id. at 29 n.114.

f. Use of racial appeals in campaigns. The Senate Report

further directs courts, when looking at the present reality of

the community's political process, to consider "whether political

campaigns have been characterized by overt or subtle racial

appeals." S. Rep. at 29. The presence of this factor, Congress

undoubtedly recognized, could provide evidence that racial

politics dominate the political process. See id. at 33. The

absence of racial appeals, however, is not fatal to a minority

group's vote dilution claim under Section 2. As Judge Wisdom

41

recognized in Marengo Countv. overt political racism has

decreased over time. 731 F.2d at 1571. Therefore, while

"[e]vidence of racism can be very significant if it is presentt,]

. . . . its absence should not weigh heavily against a plaintiff

proceeding under the results test of [S]ection 2." Id.

g. Extent to which minority candidates have been elected to

public office. The "extent to which members of the minority

group have been elected to public office in the jurisdiction," S.

Rep. at 29, along with the extent of racially polarized voting,

are the two most important factors that the district court must

consider its analysis of the totality of the circumstances. See

Gingles. 478 U.S. at 48 n.15; Westwego III. 946 F.2d at 1120.

Indeed, minority candidate success is the only factor that is

mentioned in the language of Section 2 itself.9 Subsection (b),

which sets forth the totality of the circumstances standard,

9 Judge Higginbotham suggests that, because Congress

explicitly mentioned the extent to which minorities have been

elected as a totality of circumstances factor in the statute

itself, it should somehow take precedence over the extent to

which minorities have been able to elect candidates "of their

choice." Judge Higginbotham suggests that "it is quite possible"

that minority plaintiffs will not be able to demonstrate a lack

of electoral success," an element that is crucial to their claim,

"where black Republicans win and white Democrats lose."

Dissenting Op. at 20-21. Judge Higginbotham further states that

the Senate Report precludes courts from considering-- through a

filter--whether particular minorities who have won elections have

been the minority-preferred candidate. Dissenting Op. at 23-24.

We disagree. The Senate Report directs courts to consider the

"totality of the circumstances," and where a minority candidate

is elected with virtually no support from the minority community,

a court may reasonably take that fact into account in resolving

the ultimate question under Section 2 of whether minorities have

an equal opportunity to elect "representatives of their choice." 42 U.S.C. § 1973(b).

42

expressly provides: "The extent to which members of a protected

class have been elected to office in the State or political

subdivision is one circumstance which may be considered:

Provided. That nothing in this section establishes a right to

have members of a protected class elected in numbers equal to

their proportion in the population." 42 U.S.C. § 1973(b).

In the Senate Report, Congress indicated that the analysis

of minority candidate success should be a cautious, relative

inquiry. On the one hand, Congress recognized that, where "no

members of a minority group have been elected to office over an

extended period of time," the lack of success "is probative." S.

Rep. at 29 n.115. Congress cautioned, however, against giving

too much weight to the isolated instances of minority candidate

success. Citing our decision in Zimmer. Congress noted that "the

election of a few minority candidates does not 'necessarily

foreclose the possibility of dilution of the [minority] vote' in

violation of this section." S. Rep. at 29 n.115. If such

isolated successes were allowed to foreclose a Section 2 claim,

Congress continued, "the possibility exists that the majority

citizens might evade the section[, for example,] by manipulating

the election of a 'safe' minority candidate." Id.10

10 In his dissent, Judge Higginbotham recognizes that