Sweeny Independent School District v. Harkless Brief for Respondents in Opposition

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sweeny Independent School District v. Harkless Brief for Respondents in Opposition, 1970. 6241489d-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e0704d0f-f270-4281-8791-6f9794b21a86/sweeny-independent-school-district-v-harkless-brief-for-respondents-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

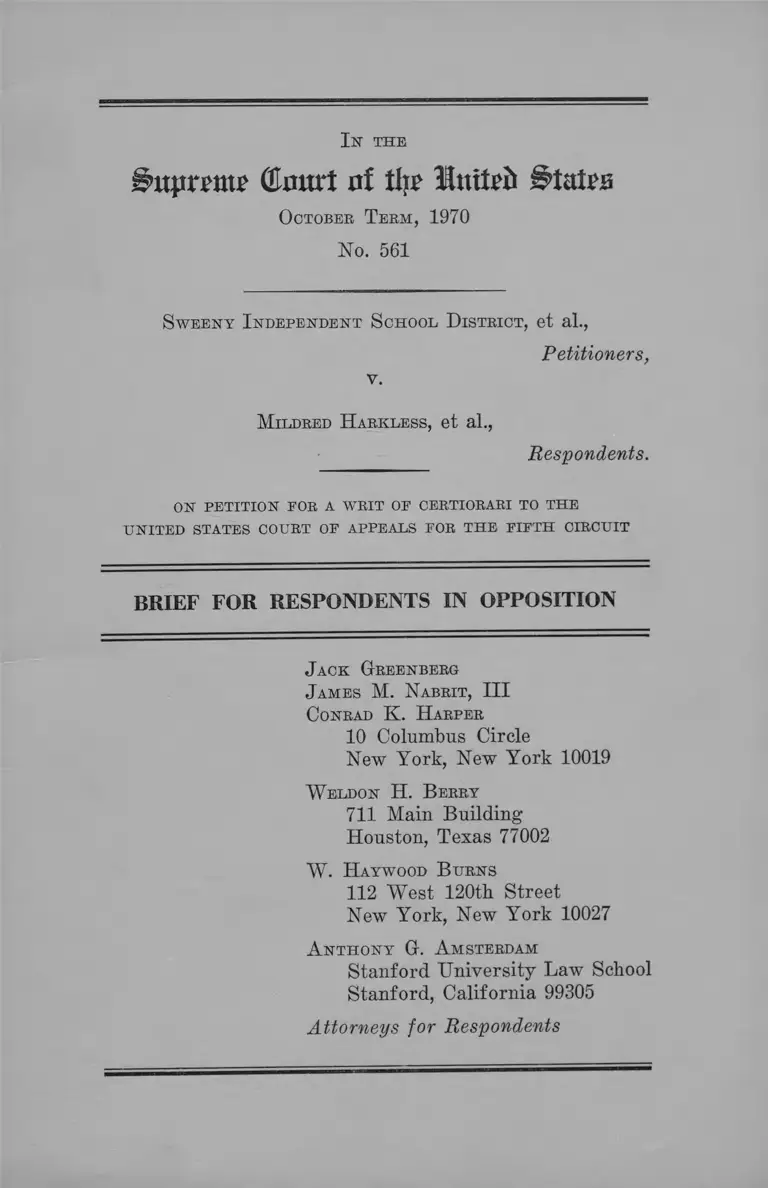

I n the

g>itpnw (Eourt of tip UntPft States

October Term, 1970

No. 561

Sweeny I ndependent School D istrict, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

M ildred H arkless, et al.,

Respondents.

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Conrad K. H arper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

W eldon H. B erry

711 Main Building

Houston, Texas 77002

W . H aywood B urns

112 West 120th Street

New York, New York 10027

A nthony G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 99305

Attorneys for Respondents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinion Below .................................................................... 1

Questions Presented ........................................................ 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ....... 2

Statement ............................................................................ 4

Reasons foe Denying the W bit

I. Review by This Court Is Unnecessary Where It

Is Now Well Settled That School Officials Are

Subject to 42 U.S.C. §1983 ..................................... 7

II. Certiorari Should Be Denied Because the Issue

Whether a School District Is Liable Under 42

U.S.C. §1983 Is Premature ................................... 10

III. Certiorari Should Be Denied Because the Issue

Whether Jury Trial Was Properly Granted Is

Premature and May Be Mooted .......................... 11

Conclusion .................................................................................... 12

Table of A uthorities

Cases:

Aetna Ins. Co. v. Paddock, 301 F.2d 807 (5th Cir.

(1962) ............................................................................. 11

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) .............................. 8, 9

Bonner v. Texas City Independent School District,

305 P. Supp. 600 (S.D. Tex. 1969) ............................. 10

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ....... 7

11

PAGE

Daniel v. Paul, 395 U.S. 298 (1969) .................................. 10

Davis v. County School Board, decided sub nom. Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .............. 8, 9

Davis v. Mann, 377 U.S. 678 (1964) .............................. 8, 9

Ex Parte Young, 209 U.S. 123 (1908) .............................. 8

Griffin v. County School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) .... 8, 9

Hurwitz v. Hurwitz, 136 F.2d 796 (D.C. Cir. 1943) .... 11

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ......................4, 5, 7, 9

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927) .......................... 8

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) .......................... 8, 9

Rinaldi v. Yeager, 384 U.S. 305 (1966) ....... 8, 9

Salazar v. Dowd, 256 F. Supp. 220 (D.Colo. 1966) ....... 7

Sanberg v. Daley, 306 F. Supp. 277 (N.D. 111. 1969).... 7

Schetter v. Housing Authority of City of Erie, 132

F. Supp. 149 (W.D. Pa. 1955) ..................................... 11

WMCA v. Lomenzo, 377 U.S. 633 (1964) ...................... 8, 9

Wolf v. Calla, 288 F. Supp. 891 (E.D. Pa. 1968) ........... 11

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions:

First Amendment.................. ........................................... 2

Seventh Amendment ......................................................... 2

Fourteenth Amendment

28 U.S.C. § 1331 ...........

28 U.S.C. § 1343(3) .....

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ...........

...............1, 2, 8,10

....................2, 3,10

...............2, 3, 4,10

1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9,10

I n the

iatpmtu? (to rt at tln> Htttfrft States

Ogtobee Teem, 1970

No. 561

Sweeny I ndependent S chool District, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

M ildred H arkless, et al.,

Respondents.

ON PETITION EOR A WRIT OE CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OE APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

Opinion Below

Since the filing of the petition for a writ of certiorari,

the opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit and the dissenting opinion of Judge Jones

have been reported at 427 F.2d 319, 324.

Questions Presented

1. Under 42 U.S.C. §1983 and the Fourteenth Amend

ment may equitable relief, including back pay for black

teachers discriminatorily not rehired because of school de

segregation, be awarded against a school district’s board

of trustees and superintendent sued only in their official

capacities ?

2

2. Assuming arguendo that school officials are liable to

equitable remedies under 42 U.S.C. §1983 for racial dis

crimination, should certiorari be granted to decide whether

the school district is also liable!

3. Assuming arguendo that school officials are liable to

equitable remedies under 42 U.S.C. §1983 for racial dis

crimination, should certiorari be granted to decide whether

the Fourteenth Amendment, together with 28 U.S.C.

§1343(3) or 28 U.S.C. §1331, authorize this action inde

pendent of 42 U.S.C. §1983!

4. Should certiorari he granted on the issue of jury trial

where:

(a) The Fifth Circuit, for the district court’s guid

ance, reversed the grant of jury trial in an equi

table action;

(b) pending motions in the district court may moot the

jury trial issue;

(c) the jury trial issue is not clearly presented because

the district court denied motions which, if re

viewed here, would likely dispose of this case on

the grounds that the arguable bases for jury trial

no longer existed or the demand for jury trial was

untimely !

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the First, Seventh and Fourteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution. This case

also involves the following statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1331.

(a) The district, courts shall have original jurisdic

tion of all civil actions wherein the matter in eontro-

3

versy exceeds the sum or value of $10,000, exclusive

of interest and costs, and arises under the Constitu

tion, laws, or treaties of the United States.

(b) Except when express provision therefor is other

wise made in a statute of the United States, where the

plaintiff is finally adjudged to he entitled to recover

less than the sum or value of $10,000, computed with

out regard to any set off or counterclaim to which the

defendant may be adjudged to be entitled, and exclu

sive of interests and costs, the district court may deny

costs to the plaintiff and, in addition, may impose

costs on the plaintiff.

28 U.S.C. §1343(3).

The district courts shall have original jurisdiction

of any civil action authorized by law to be commenced

by any person:

* * #

(3) To redress the deprivation, under color of any

State law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or

usage, of any right, privilege or immunity secured by

the Constitution of the United States or by any Act

of Congress providing for equal rights of citizens or

of all persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States.

42 U.S.C. §1983.

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordi

nance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or

Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any

citizen of the United States or other person within

the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Con

stitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured

in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper

proceeding for redress.

4

Statement

Respondents are ten black teachers who were not rehired

for the 1966-67 school year by the Sweeny Independent

School District. The instant action, charging racial dis

crimination, was filed May 23, 1966, seeking the equitable

remedies of injunctive relief and back pay in the United

States District Court for the Southern District of Texas

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1343(3), 42 U.S.C. §1983, and the

Fourteenth Amendment (A. 1-14, 61-62, 83-84, 206-18J.1

Respondent black teachers named as defendants the school

district, the superintendent of schools, and the members of

the district’s board of trustees in both their individual and

official capacities. But at the time of voir dire examina

tion of the jury panel2 on March 3, 1969, and because of

the unwillingness of some members of the panel to assess

a monetary award against the defendants individually (A.

224-40), respondents’ counsel moved to dismiss the official

defendants in their individual capacities (A. 232). The

motion was granted leaving as defendants only the school

district and the individual defendants in their official ca

pacities (A. 237-39).

Subsequently, during trial, and in response to a sugges

tion by the district court that because of Monroe v. Pape,

365 F.S. 167 (1961) subject matter jurisdiction over the

reiuainiug defendants might be lacking, petitioners moved,

to dismiss on this ground (A. 244-49. 253-54' On March

U\ 1969, the case was submitted to the jury m special

C " ̂ a \ un X '-'tU'C u -titf v j r r “ x ir .

'N Vid V ; u A -ss; v. ^ ^UlTjU A? STT

V ' A n n ' N X \ ^ 4 VNt V . 5 t V- ' » v . ' T. . M

NN N>.N N \ . -X X v I V . X - , 99• A n ; o - r A

( H | j | i l i v y ' \ \ w ^ v v V ' V ' A S n . . . . J j T ’ * / ' i S > S ' R r

V W V V S '*NN\4v ' " P ,V> v < ' '-sv tv,... y . X X t C C.

5

interrogatories and the jury rendered a verdict.3 But the

district court, on June 6, 1969, dismissed the second

amended complaint without resolving any other issues on

the grounds that Monroe v. Pape, supra, did not permit

recovery against the school district and its officials sued

in their official capacities.

3 The jury found that (A. 118-23) :

Question Number 1: Do you find from a preponderance of

the evidence that any plaintiff’s race (Negro) was a factor

in the failure of the Board of Trustees of The Sweeny Inde

pendent School District to offer re-employment for the school

year 1966-67 ?

Answer: “No”

Question Number 2A: Do you find from a preponderance of

the evidence the Board of Trustees of the District, on the

occasion^ of its regular meeting of March 8, 1966, or at any

time prior thereto, decided that the professional (teaching)

staff of the system (District) would have to be reduced as a

result of desegregation?

Answer: “Yes”

Question Number 2B: If, but only if, you have answered

Question Number 2A “Yes” , you will answer this question:

Do you find from a preponderance of the evidence that when

the Board determined at the March 8, 1966 meeting not to

offer plaintiffs re-employment for the school year 1966-67, the

qualifications of any plaintiff to teach in the District was

not and had not been fairly and impartially evaluated and

compared with the qualifications of all other teachers who

taught in the system (District) during school year 1965-66.

without consideration of the fact such plaintiff was a Negro '

Answer: “No”

Question Number 3A : It is undisputed in the record that a ;

ter March 8, 1966 the Board of Trustees decided to A'a : a

new teachers from outside the system (not employed b\ A s

District during 1965-66), to fill vacancies for the year hss <

created by the displacement of teaching staff result mg free

desegregation. Bearing this in mind, do you find from a pre

ponderance of the evidence that before 'filling any such vs

6

On appeal, the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit, on June 2, 1970, reversed, 2-1, holding that

a school district and its officials are liable to suit under

42 U.S.C. §1983 and that in an equitable action for injunc

tive relief and back pay, jury trial is not required.

caney, the Board failed to determine that any plaintiff was

not qualified to fill any such vacancy ?

Answer: “No”

Question Number 3B: With respect to any plaintiff whose

name you have written in the space next above provided, do

you find from a preponderance of the evidence that the Board

failed to evaluate the qualifications of such plaintiff to fill

such vacancy fairly and impartially ?

Answer: No Answer

Question Number 4: Do you find from a preponderance of the

evidence that the Superintendent Fred Miller and the Board

of Trustees acted in good faith at all times and in every

respect in the process of the Board’s decision not to offer any

plaintiff re-employment for the school year 1966-67?

Answer: “Yes”

Question Number 5: Do you find from a preponderance of

the evidence that a factor relied upon by the Board in reach

ing its decision not to offer any plaintiff re-employment for

the year 1966-67 after the filing of this law suit on May 23,

1966, was the fact that any such plaintiff was a party to

this law suit?

Answer: “Yes”

I f you have answered this Question Number 5 “Yes” , then

in the space next provided write the name of each plaintiff

with respect to which you have so found; but, if you have

answered the question “No” , you will not write any* name in

such space.

Mildred Hartless, John P. Jones, Robert C. Woodard, Willie

Dotson, Rillion F. Jammer, Benjamin F. Periston and Velma

L. Shelby

7

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

I.

Review by This Court Is Unnecessary Where It Is

Now Well Settled That School Officials Are Subject to

42 U.S.C. §1983.

At least since Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) it has been clear that 42 U.S.C. §1983 grants a right

of action for the racially discriminatory conduct of school

officials. Petitioners’ argument to the contrary is both

frivolous and revolutionary (see Petition for a Writ of

Certiorari at 10-11). Petitioners assert that Monroe v.

Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961)—a case not involving equitable

relief for official racial discrimination—somehow reduced

the power of federal courts to curb racially discriminatory

school boards. Monroe merely held that the city of Chi

cago was not liable in damages, in a respondeat superior

context, for the torts of its police officers. We agree with

the Court of Appeals that footnote 50 of the Monroe

opinion, 365 U.S. at 191, means that earlier cases decided

by this Court allowing equitable relief against municipali

ties do not permit the inference, after Monroe, that dam

age actions may be maintained against municipalities un

der the doctrine of respondeat superior. 427 F.2d at 322.

Similarly, officials not personally involved in deprivation

of civil rights are also not subject to § 1983. Salazar v.

Dowd, 256 P. Supp. 220, 223 (D. Colo. 1966); Sanberg v.

Daley, 306 F. Supp. 277 (N.D. HI. 1969). The instant case

is one, however, where respondeat superior is not at issue

since the school board members named as defendants were

the officials who actually refused to rehire respondent black

teachers.

This Court has repeatedly exercised its power over state

officials sued only in their official capacities under § 1983

8

or the Fourteenth Amendment.4 * E.g., Ex Parte Young,

209 U.S. 123,159-60 (1908) (state attorney general) ;B Baker

v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) (state officials, including the

secretary of state and the attorney general) ;6 Reynolds v.

v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 537 (1964) (state election officials);

WMCA v. Lorenzo, 377 U.S. 633, 635 (1964) (state election

officials); Davis v. Mann, 377 U.S. 678, 680 (1964) (state

election officials); Griffin v. County School Board, 377 U.S.

218, 228 (1964) (county board of supervisors) ;7 Rinaldi v.

4 Significantly in Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927) Mr.

Justice Holmes, writing for the Court, held that the Fourteenth

Amendment forbids state court judges to bar blacks from voting

in a Democratic primary election as required by state statute. The

action was brought against the judges of elections for damages

of $5000. 273 U.S. at 539. The amended petition, founded upon

the predecessor of §1983 and other statutes (R. at 4-5), sought

relief against the officials only as officials (R. at 3) :

The amended petition sought “ . . . to redress an injury

which he [plaintiff] sustained by reason of the acts of defen

dants in their official capacities discriminating against him by

reason of his race and color, in violation of the constitution

and laws of United States.” (emphasis supplied)

In their motion to dismiss the defendant judges raised claims,

inter alia, of failure to state a cause of action and the court’s

inability to grant relief (R. at 8 ) ; the motion to dismiss was sus

tained and the cause dismissed (R. at 9). This dismissal was, of

course, reversed by this Court in Nixon v. Herndon, supra.

6 The state attorney general was sued only in his official capacity

as is made clear in the following papers contained in the Young

record on file in this Court: Petitioner’s Petition for Writs of

Habeas Corpus and Certiorari and Motion for Leave to file, at 8,

15 (copy of original bill of complaint annexed to Petition) ■ Peti

tioner’s Brief on Hearing of Rule to Show Cause, at 6-8.

6 Record, at 5, Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962).

7 The district court below misapprehended the importance of

the Griffin holding by erroneously asserting Griffin was not a

§1983 case. 300 F. Supp. at 805. But Griffin did in fact arise under

the Act of April 20, 1871, now codified in part and 42 U.S.C. §1983.

The Griffin litigation began in 1961 by the filing of an amended

supplemental complaint in Davis v. County School Board, decided

sub nom. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). The

9

Yeager, 384 U.S. 305 (1966) (state prison officials and

county treasurer) ,8 Nor must it be forgotten that in Monroe

itself, it was the City of Chicago, not any of its officials,

which was held not subject to damages under § 1983.

In view of this list of precedents before and after Mon

roe, petitioners take two position: (1) this Court did not

mention Monroe in those cases postdating 1961; and (2)

several lower federal courts have held officials not subject

to § 1983. (Petition for a Writ of Certiorari at 10-12.) The

first position perpetuates a misunderstanding of what Mon

roe held. It is not necessary for this Court to mention

Monroe in cases where it does not apply. Since Monroe

involved a municipality sued for damages as respondeat

superior, its holding does not affect claims for injunctive

and monetary relief against officials sued in their official

capacities for their own acts, as in Rinaldi; nor does Mon

roe’s holding affect claims for equitable relief against offi

cials sued in their official capacities to enjoin those officials

from acting unconstitutionally as in Baker v. Carr, Rey

nolds v. Sims, WMCA v. Lomenzo, Davis v. Mann, and

Griffin.

Petitioners’ second position—i.e., that 55 federal cases

have concluded contrary to the Fifth Circuit, that § 1983

does not apply to officials—involves imprecision as to the

holdings of those cases. Only one of the 55 cases is in point

because it involved, as here, equitable relief from racial

discrimination by officials not sued as respondeat superior.

amended supplemental complaint—while adding new parties such

as the county board of supervisors— did not disturb the original

statutory basis of the action, i.e., §1983. Davis Record at 5, Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954); Record at 20, Griffin

v. County School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964).

8 In Rinaldi, the officials specifically claimed by way of defense

that the acts complained of were done in their official capacities.

Record at 1, 13-16, Rinaldi v. Yeager, 384 U.S. 305 (1966).

10

This case9 was decided subsequent to the district court

opinion below by the same district court judge whose deci

sion in the instant case was reversed by the Fifth Circuit.

The other 54 cases did not involve non-vicarious liability

in equity for official racial discrimination. For this reason,

petitioners have shown no conflict between the Fifth Cir

cuit’s opinion below and other federal courts. In short,

the Fifth Circuit was plainly right in holding school offi

cials liable for racial discrimination.

II.

Certiorari Should Be Denied Because the Issue

Whether a School District Is Liable Under 42 U.S.C.

§1983 Is Premature.

In view of the well-settled law, set out in Argument I,

that school officials are liable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for

racial discrimination, it is premature for this Court to

reach the question whether a school district is also liable.

This is so because equitable relief against the school offi

cials would, as a practical matter, satisfy the claims of

respondent black teachers and make academic the issue

of school district liability. While it was proper for the

Fifth Circuit to decide the question of school district lia

bility for the guidance of the district court, this Court does

not sit to render advisory opinions; therefore the issue of

school district liability need not be faced here. See, e.g.,

Daniel v. Paul, 395 U.S. 298, 300 n. 1 (1969).10

9 Bonner v. Texas City Independent School District, 305 F. Supp.

600, 616 (S.D. Tex. 1969).

10 For essentially similar reasons— and the added fact that the

Fifth Circuit did not reach the question— it is also unnecessary for

this Court to decide whether the Fourteenth Amendment together

with 28 U.S.C. §1343(3) or 28 U.S.C. §1331 authorize this action

independent of 42 U.S.C. §1983.

11

III.

Certiorari Should Be Denied Because the Issue

Whether Jury Trial Was Properly Granted Is Premature

and May Be Mooted.

For the guidance of the district court, which dismissed

the complaint without reliance on the verdict, the Fifth

Circuit below also held that jury trial had been erroneously

granted. This issue, brought to this Court’s attention by

petitioners, is premature for these reasons: (a) since the

Fifth Circuit predicated reversal upon the well-settled law

discussed in Argument I, other grounds for the Fifth Cir

cuit’s action need not be faced here; (b) the jury trial issue

may be mooted by subsequent district court proceedings;

(c) the jury trial issue is not clearly presented on this

record. The first of these reasons is self-evident and it also

applies to other issues in this case discussed in Argument

II, supra. The second of these reasons rests upon the fact

that the special verdict set out supra at pp. 5-6, n. 3, is

arguably construable for seven of the ten respondents or

for the petitioners; consequently the district court can

hardly enter judgment unclarified by its own findings.

These findings may, in effect, render the verdict advisory

and thus well within established equity practice. See Hur-

witz v. Hurwitz, 136 F.2d 796 (D.C. Cir. 1943); Aetna Ins.

Co. v. Paddock, 301 F.2d 807 (5th Cir. 1962); Wolff v. Calla,

288 F. Supp. 891 (E.D. Pa. 1968), Schetter v. Housing Au

thority of City of Erie, 132 F. Supp. 149 (W.D. Pa. 1955).

Furthermore, in the district court, respondent black teach

ers have pending motions for judgment n.o.v. and for new

trial. If either of these motions is granted, the jury trial

question is moot on this record.

Finally, the jury trial question is inextricably connected

to respondent black teachers’ right to dismiss that portion

12

of their second amended complaint arguably giving the

right to jury trial (A. 71, 84-86, 89-95, 249-52) as well as

the arguably untimely demand for jury trial by peti

tioners.11 It is likely, therefore, that the right to jury trial

cannot be decided on this record because of these factors;

in which case, the certiorari jurisdiction should not be

exercised.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. N abrit, III

Conrad K. H arper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

W eldon H. B erry

711 Main Building

Houston, Texas 77002

W. H aywood B urns

112 West 120th Street

New York, New York 10027

A nthony G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 99305

Attorneys for Respondents

11 Petitioners waived their right to jury trial on the original

complaint but demanded jury trial on the first amended complaint

which did not change the relief sought but only added a due process

of law theory to the equal protection of the laws claim in the

original complaint (A. 61-63). Over respondents’ objections, the

district court permitted jury trial as to all issues merely because

an additional theory had been added. 278 P. Supp. 637 (A. 95-100)

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219