Northwest Austin Municipal Utility Distr. One v. Holder Brief of Barbara Lee et al. as Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

March 25, 2009

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Northwest Austin Municipal Utility Distr. One v. Holder Brief of Barbara Lee et al. as Amici Curiae, 2009. e066a4ea-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e0a7540a-2009-48a5-b68a-500f80058b15/northwest-austin-municipal-utility-distr-one-v-holder-brief-of-barbara-lee-et-al-as-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

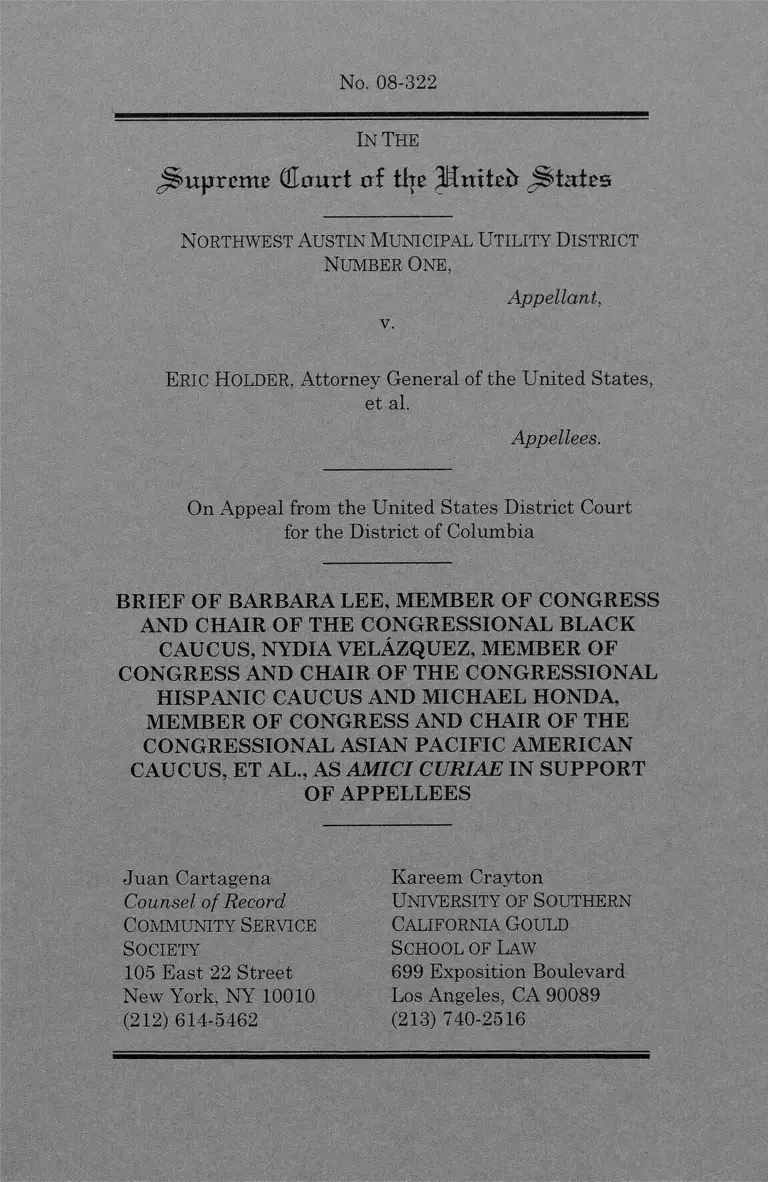

No. 08-322

In The

Jinpreme (Hourt ci ttje JMnitefr S tates

Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District

Number One ,

Appellant,

ERIC H older, Attorney General of the United States,

et al.

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

BRIEF OF BARBARA LEE, MEMBER OF CONGRESS

AND CHAIR OF THE CONGRESSIONAL BLACK

CAUCUS, NYDIA VELAZQUEZ, MEMBER OF

CONGRESS AND CHAIR OF THE CONGRESSIONAL

HISPANIC CAUCUS AND MICHAEL HONDA,

MEMBER OF CONGRESS AND CHAIR OF THE

CONGRESSIONAL ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN

CAUCUS, ET AL., AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT

OF APPELLEES

Juan Cartagena

Counsel of Record

Com munity Service

Society

105 East 22 Street

New York, NY 10010

(212) 614-5462

Kareem Crayton

University of Southern

California Gould

School of Law

699 Exposition Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA 90089

(213) 740-2516

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.......................................... ii

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE................................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................................. 2

ARGUMENT................................................ 4

I. The Diversity in Contemporary Politics Is a

By-Product of Steadfast Voting Rights

Enforcement............................... 4

II. Expansion and Retrenchment in the Long

Struggle to Extend the Franchise to Minority

Voters...........................................................................9

III. Congress Found That Minority Voters Face

Ongoing Voting Discrimination in the

Covered Jurisdictions..................................... .......13

IV. Preclearance Is a Crucial Tool for Realizing

America's Democratic Goals..................................20

CONCLUSION................ 24

APPENDIX A

Listing of Amici Curiae............................... 25

APPENDIX B

Racial Gaps in Voter Registration.............................. 30

APPENDIX C

Members of Congressional Asian Pacific

American Caucus....................................................... 31

11

APPENDIX D

Members of Congressional Black Caucus............ 33

APPENDIX E

Members of Congressional Hispanic Caucus........ 35

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Bartlett v. Strickland, No. 07-689, 2009 WL 578634,

(U.S. 2009)...................................... ...................... ..........9

Johnson v. DeGrandy 512 U.S. 997 (1994)....... 22

Lopez v. Monterey County, 525 U.S. 266 (1999)...... 14

NAMUDNO u. Mukasey, 573 F. Supp. 2d 221 (D.D.C.

2008)................................................................................ 13

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301

(1966)...............................................................................10

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1875)....11

United States v. Reese, 92 U.S. 214 (1875)............... 11

Constitutional Provisions

U.S. Const, amend. X IV ..........................................2, 20

U.S. CONST, amend. XV......................................2, 11, 20

Statutes

42 U.S.C. § 1973 (West 2006).............................passim

Legislative Materials

152 Cong. Rec. H5143-5164 (daily ed.

July 13, 2006)................................................ ...passim

H.R. Rep. No. 109-478 (2006)..........................passim

IV

Reauthorizing the Voting Rights Act’s Temporary

Provisions: Policy Perspectives and Views from the

Field: Hearing on S. 2703 Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution, Civil Rights and Prop. Rights of the S.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. (2006)... 16, 18

Renewing the Temporary Provisions of the Voting

Rights Act: Legislative Options After LULAC v. Perry:

Hearing on S. 2703 Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution, Civil Rights and Prop. Rights of the S.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. (2006).......... 17

The Continuing Need for Section 5 Pre-Clearance:

Hearing on S. 2703 Before the S. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. (2006).................................. 19

To Examine the Impact and Effectiveness of the

Voting Rights Act: Hearing on H.R. 9 Before the

Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. (2005)......................................17

Voting Rights Act: An Examination of the Scope and

Criteria for Coverage Under the Special Provisions of

the Act: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution, H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th

Cong. (Oct. 20, 2005)....................................................... 7

Voting Rights Act: Section 5—Preclearance

Standards: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th

Cong. (2005)..................................................................10

Voting Rights Act: Section 203 Bilingual Election

Requirements: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution, H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong.

(Nov. 8, 2005)............................................................... 12

V

Voting Rights Act: The Continuing Need for Section 5:

Hearing Before the Suhcomm. on the Constitution of

the H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. (2005)..14

Voting Rights Act: Section 5 of the Act—History,

Scope, and Purpose: Hearing on H.R. 9 Before the

Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. (2005).....................................17

Other Authorities

Alvaro Bedoya, The Unforseen Effects of Georgia v.

Ashcroft on the Latino Community, 115 YALE L.J.

2112 (2006)..................................... ............................. 18

David Bositis, J o in t Ce n te r f o r P o l it ic a l &

E c o n o m ic St u d ie s , B la c k E le c te d O f f ic ia l s : A

St a t is t ic a l Su m m a r y 2000 (2002).............................6

Brief of Appellant Northwest Austin Municipal

Utility District Number One, NAMUDNO v. Holder,

No. 08-322 (2009)............................. 9

Brief for Intervenors-Appellees Rodney and Nicole

Louis, et al.; Lisa and David Diaz, et al.; Angie

Garcia, et al.; and People for the American Way,

NAMUDNO v. Holder, No. 08-322

(2009).....................................................................16, 19

Brief of Reps. John Conyers, Jr. et al. as Amici

Curiae in Support of Appellees, NAMUDNO v.

Holder, No. 08-322 (2009).............................................15

David S. Broder & Kenneth Cooper, Asian Pacific

Caucus Wash. Post May 22, 1994 at 10......................7

VI

Chandler Davidson & Bernard Grofman, Eds.

Quiet Revolution in the South (1994)................... 6

Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote

(2000) ........................................................................................ 10, 11

J.. Morgan Kousser, The Voting Rights Act & Two

Reconstructions in CONTROVERSIES IN MINORITY

VOTING 135. (Bernard Grofman & Chandler

Davidson eds., 1992).........................................4, 10, 11

John Lewis, Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of

the Movement (1999).................................................. 5

NALEO Educ. Fund, Nat’l Ass’n of Latino Elected

& Appointed Officials, 2008 General Election

Profile: Latinos in Congress and State

Legislatures After Election 2008: A State-By -

State Summary (2008).................................................6

National Asian Pacific American Political

Almanac 2007-08 (Don T. Nakanishi & James S. Lai

eds., 13th ed.

2007)................................................................................. 7

Sandra D. O’Connor, Thurgood Marshall: The

Influence of a Raconteur, 44 STAN. L. Rev. 1217

(1992)...............................................................................22

Vll

C. V a n n W o o d w a r d , T he Fu tu r e of th e P a st

(1989)............................................... ............................... 4

C. V a n n W o o d w a r d , R e u n io n a n d R e a c t io n

(1956)..............................................................................11

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Amici curiae1 are elected members of the

United States House of Representatives.2 These

elected officials include 41 members of the

Congressional Black Caucus (“CBC”), 23 members of

the Congressional Hispanic Caucus (“CHC”), and 11

members of the Congressional Asian Pacific

American Caucus (“CAPAC”) (collectively, the “Tri-

Caucus”).3 These caucuses were established to

provide representation and constituency service for

millions of American voters from communities whose

experiences with racial discrimination in voting

prompted passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The growth of each caucus’s membership has made

Congress more racially diverse and inclusive, in large

part due to the successful enforcement of the Voting

Rights Act’s preclearance provisions in covered

jurisdictions. Many of these members publicly

1 Letters of consent by the parties to the filing of this brief

have been lodged with the Clerk of Court pursuant to Rule of

the Supreme Court of the United States 37.3. In accordance

with Rule of the Supreme Court of the United States 37.6, amici

curiae certify that no counsel for a party authored this brief in

whole or in part and that no person or entity, other than amici

curiae and their counsel, made a monetary contribution to the

preparation or submission of this brief.

2 A complete listing of all amici is attached as Appendix A.

3 Each of the three caucuses has at least one member who

is a U.S. Senator. The signatories to this brief are all members

of the U.S. House of Representatives. Further, some members

belong to multiple caucuses. See Appendices C-E.

2

supported and cast floor votes in favor of extending

the preclearance provisions in 2006.4

The two issues presented in this case are (1)

whether petitioner-appellant, a local utility district in

Texas, is entitled to preclearance “bailout”, under

Section 4(a) of the Voting Rights Act and (2) if not,

whether the recently renewed preclearance

provisions of the Act remain a constitutionally valid

exercise of Congress’s authority to root out racial

discrimination in the area of voting as embodied by

Section 2 of the Fifteenth Amendment and Section 5

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Because of the Act’s

effective record of deterring discrimination in the

voting process, amici have an interest in defending

the preclearance regime to secure the voting rights of

the millions of Americans they serve.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Amici curiae strongly contend that the

preclearance requirement outlined in Section 5, 42

U.S.C. § 1973 [hereinafter Section 5], of the Voting

Rights Act remains a permissible and effective

statutory tool for eliminating and deterring voting

discrimination in the political process. Section 5

helps to ensure that state and local jurisdictions do

not implement discriminatory voting changes that

4 Other members took office following the reauthorization

of the Voting Rights Act in 2006, but signal their support for the

legislation by joining as amici herein.

3

might otherwise deny or abridge the right to vote

with respect to race.

Steadfast enforcement of the Voting Rights

Act, which provides opportunities for voters to

participate in the political process and to elect their

candidates of choice, has led to greater diversity in

Congress along with many state and local legislative

bodies. But these changes are of a relatively recent

vintage. This is particularly so when compared to the

extended period in which the denial and abridgement

of the franchise was the norm.

While the advancements for minority voters

are rightly lauded, the lesson of America’s difficult

history of race and politics teaches that these gains

are often fragile. The efforts to secure greater levels

of political incorporation for racial minority groups

have played and continue to play an important role in

American Democracy. Yet, as the Jim Crow

experience following the derailed Reconstruction

aptly demonstrates, withdrawing federal protections

that effectively remedy and deter discrimination

effectively should be approached with great care.

In light of this history along with a thorough,

carefully reviewed record of ongoing voting

discrimination in those jurisdictions covered by

Section 5, Congress renewed the preclearance

requirement with an overwhelmingly bi-partisan vote

in 2006. See 152 CONG. REC. H5148 (daily ed. July

13, 2006) (statement of Rep. Melvin Watt) (noting

that the re authorization was “the product of a long

4

term, thoughtful, and thorough bipartisan

deliberation” and that the Voting Rights Act is

“arguably the most carefully reviewed civil rights

measure in our Nation's history.”). That extension

was fully warranted to help complete the important

task commenced in 1965 — to ensure that every

American, regardless of race, enjoys an equal voice in

our nation’s governance. Accordingly, this Court

should find that the reauthorization of Section 5 was

within the proper scope of Congressional enforcement

authority under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments.

ARGUMENT

I. The Diversity in Contemporary Politics Is

a By-Product of Steadfast Voting Rights

Enforcement.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 “is about

protecting the most basic and significant civil right [ ]

for all American citizens, the right to vote.” 152

CONG. REC. H5152 (daily ed. July 13, 2006)

(statement of Rep. Grace Napolitano). Many describe

the initial passage of the Voting Rights Act as the

start of America’s Second Reconstruction. J.. Morgan

Kousser, The Voting Rights Act & Two

Reconstructions in CONTROVERSIES IN MINORITY

VOTING 135, 136-37. (Bernard Grofman & Chandler

Davidson eds., 1992); see also C. Vann Woodward,

Th e Fu tu r e o f th e Pa s t 199 (1989). The Act came in

the aftermath of an era characterized by rampant

discrimination and brutality. Amici John Lewis (D-

5

GA) reminded Congress in 2006 about the immediate

events in March, 1965 that first moved Congress to

enact this landmark statute. Long before he was

elected to political office, Representative Lewis was a

disenfranchised minority voter seeking to have his

voice heard: “When we marched from Selma to

Montgomery in 1965, it was dangerous. It was a

matter of life and death. I was beaten, I had a

concussion at the bridge. I almost died. I gave blood,

but some of my colleagues gave their very lives.” 152

CONG. REC. H5164 (daily ed. July 13, 2006)

(Statement of Rep. John Lewis); see also John Lewis,

W a l k in g w ith th e W in d : A M e m o ir of th e

MOVEMENT (1999). Passage of the Voting Rights Act

has helped to transform the political landscape in a

variety of ways, and signs of the change are evident

in today’s politics.5

For minority groups that have experienced

unlawful political exclusion, electing preferred

candidates is an important barometer of their

incorporation. On this score, notable gains have been

made in legislatures at the state and federal levels.

These gains are attributable, in large part, to the

important protections and safeguards provided by the

Voting Rights Act and its Section 5 preclearance

5 One of the primary concerns of the Act is increasing

political participation. Data on registration and turnout during

the relevant enforcement period shows signs of progress for all

three non-white communities. See Appendix B. Still, a sizable

lag in these measures remains - particularly for Hispanic and

Asian American populations -- relative to the national average.

6

remedy. See 152 CONG. REC. H5152 (daily ed. July

13, 2006) (statement of Rep. Linda Sanchez) (“The

Voting Rights Act plays a critical role in fulfilling the

promise of American democracy. It has given voice to

minority communities, and without it, many black,

Hispanic, and Asian American leaders would not be

holding elected office today.”). However, these gains

remain fragile as a result of ongoing racially

polarized voting and its manipulation by officials. By

working to protect districts where minorities have an

opportunity to elect candidates of choice, Section 5 of

the Voting Rights Act has led to increased diversity

in our nation’s state and federal legislative bodies.

See generally QUIET REVOLUTION IN THE SOUTH.

(Chandler Davidson & Bernard Grofman eds., 1994).

At the state level, the number of black legislators

in preclearance states has grown since the last

renewal of Section 5 in 1982. Between 1984 and

1998, the number of black state legislators increased

by at least fifty percent in several covered

jurisdictions, including South Carolina, Georgia,

Florida, New York and Mississippi. David Bositis,

J o in t Ce n te r fo r P o l itic a l & E c o n o m ic St u d ie s ,

B l a c k E le c te d O f f ic ia l s : A S t a t is t ic a l Su m m a r y

2000 (2002), The ranks of Hispanic state legislators

also show similar gains, rising from a national total

of 69 in 1985 to 233 by 2006. Their advancement has

been most pronounced in the States of California,

Florida, Texas, and Arizona (all of which are, in

whole or in part, subject to preclearance review).

NALEO E d u c . Fu n d , Na t ’l A ss ’n of La tin o E le c te d

& A pp o in te d O f f ic ia l s , 2008 G e n e r a l E le c tio n

7

P r o f il e : La t in o s in C o n g r e ss a n d Sta te

L e g isla tu r e s A f t e r E l e c t io n 2008: A S ta t e -By -

S ta te SUMMARY (2008). Asian Americans now serve

in a total of 90 state legislative seats nationwide.

N a t io n a l A s ia n Pa c if ic A m e r ic a n P o l itic a l

A lm a n a c 2007-08, 82 (Don T. Nakanishi & James S.

Lai eds., 13th ed. 2007).

Amici themselves provide the clearest evidence of

a changed environment in Congress. See, e.g., Voting

Rights Act: An Examination of the Scope and Criteria

for Coverage Under the Special Provisions of the Act:

Hearing Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution, H.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. (Oct. 20, 2005)

(statement of Rep. Sanchez), at 111 (noting that “as

the only Latina on the House Judiciary Committee,”

the hearings regarding the re authorization of the

VRA are "significant to me and thousands [of]

residents in my home state of California").

When they first organized, the CBC and CHC

collectively numbered fewer than two dozen

members. Over the last two decades, however, these

groups have grown and have expanded their

geographical reach. See Appendices C-E. The

establishment of CAPAC in 1994 was another

important milestone; its ten founding members

represented progress when compared to the arrival of

the lone Asian-American member of Congress who

8

served in the 1950s.6 These groups collectively help

make the current Congress a significantly more

representative body that better reflects the racial

diversity of our nation.7 Moreover, these members

are often at the center of legislative action; many

hold key policymaking roles on Capitol Hill.

Critically, these signs of progress at the state

and federal levels are directly linked to the critical

benefits afforded by Section 5. In addition, this

progress is an indicator that Section 5 operates

successfully to prevent discrimination in many forms.

Amici have well-founded concerns about the potential

for backsliding and retrenchment in the absence of

Section 5’s crucial protections. Throughout the

reauthorization process, several amici urged their

colleagues to support reauthorization in light of the

significant work left to do. See, e.g., 152 CONG. Rec.

H5146 (daily ed. July 13, 2006) (statement of Rep.

John Conyers) (“And though there is much to

celebrate, efforts to suppress or dilute minority

votes...are still all too common. I am proud of the

progress we have made, but the record shows that we

haven't reached a point where the particular

6 See e.g., David S. Broder & Kenneth Cooper Asian Pacific

Caucus WASH. P ost May 22, 1994, at A10 (discussing the

membership and purposes of the CAPAC).

7 The current session of the U.S. House of Representatives

also includes Rep. Keith Ellison of Minnesota (a member of the

CBC) the country’s first Congressman of Muslim faith and Rep.

Joseph Cao of Louisiana (a member of the CAPAC) its first

Vietnamese-American Congressman.

9

provisions in the act should be allowed to lapse”); id.,

at H5148, (statement of Rep. Watt) (“We should be

clear: although the successes of the Voting Rights

Act have been substantial, they have not been fast

and they have not been furious. Rather, the

successes have been gradual and of very recent

origin. Now is not the time to jettison the expiring

provisions that have been instrumental to the success

we applaud today. In a Nation such as ours, we

should want and encourage more Americans to vote,

not fewer.”); id., at H5164 (statement of Rep. Lewis)

(“Yes, we have made some progress. We have come a

distance. We are no longer met with bullwhips, fire

hoses, and violence when we attempt to register and

vote. But the sad fact is, the sad truth is

discrimination still exists, and that is why we still

need the Voting Rights Act. And we must not go

back to the dark path. We cannot separate the

debate today from our history and the past we have

traveled.”).

II. Expansion and Retrenchment In The Long

Struggle to Extend the Franchise to

Minority Voters.

A common theme found in the briefs filed by

opposing parties and their aligned amici is that we

have entered an era in which discrimination no

longer seriously threatens the political rights of

minority voters. See, e.g., Brief for Appellant

Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District Number

One, NAMUDNO v. Holder, No. 08-322, at 1-2, 27.

10

That notion simply is not consistent with America’s

long experience with regulating the right to vote,

particularly when it comes to extending the franchise

to non-white citizens. Nor is it consistent with the

record that was before Congress in 2006. As Justice

Kennedy only recently observed, “racial

discrimination and racially polarized voting are not

ancient history.” Bartlett v. Strickland, No. 07-689,

2009 WL 578634, at *16 (U.S. 2009). These recent

steps toward full political incorporation remain

fragile and therefore ought to be guarded carefully.

This is precisely what Congress sought to do by

carefully studying the effects of Section 5 and

subsequently reauthorizing the preclearance remedy.

The voluminous Congressional record supporting

the 2006 renewal includes testimony from scholars,

litigators, historians, experts and others arguing that

the right to vote has been contested at almost every

point in this nation’s history. See Voting Rights Act:

Section 5—Preclearance Standards: Hearing Before

the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H. Comm, on

the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 67 (2005) While the

historical evolution in America has been one in which

we have moved to extend the franchise to previously

excluded citizens, that movement has regrettably

included periods of retrenchment and retraction.

A l e x a n d e r K e y s s a r , T he R ig h t to V ote 106 (2000).

As Congress recognized in the 2006 reauthorization,

the nation’s 19th century Reconstruction experience

provides a very poignant and telling illustration of

our nation’s voting rights struggle.

11

Ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870

marked an important stage of the effort to secure the

fundamental right of citizenship regardless of race.

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 326

(1966). Within five years of the Amendment’s

ratification, Congress passed bills prohibiting voter

intimidation and bribery, establishing federal

supervision of Congressional elections, and banning

extralegal political violence. Kousser, supra at 138-

39. During this period, black political participation

spiked in Southern states, and black state and

federal legislators from this region grew to 324 by

1872 — the high point of the Reconstruction era. Ibid.

However, the nation’s commitment to

enfranchise freedmen gave way to political

compromise in 1877. C. VANN WOODWARD REUNION

A nd R e a c t io n 210-20 (1956). The twenty-five years

that followed included the dismantling and reversal

of anti-discrimination laws. Absent federal

protections, black voters and officeholders had no

effective means to defend against a widespread

campaign to roll back their hard-won gains. Tactics

used to restrict or dilute the franchise included

gerrymandering, statutory suffrage restriction, and

constitutional disfranchisement. All of these

manipulative devices utilized state power and were

designed with a patently unconstitutional goal - to

eliminate every element of black political influence in

the South permanently. The strategy was feasible

because the federal government had prematurely

retreated from the goal of giving full force and effect

to the Fifteenth Amendment. See, e.g., United States

12

v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542, 559 (1875); United States

v. Reese, 92 U.S. 214 (1875).

The change of fortunes for black political

incorporation after 1877 was as precipitous as it was

predictable. KEYSSAR, supra, at 114. As Southern

disfranchising tactics became more successful, white

supremacists regained political power in state and

local government. They then moved quickly to

entrench their control over the political process by

establishing a racially-exclusive political system. As

a consequence of more restrictive and discriminatory

provisions, black participation in all forms

evaporated in the South. By 1898, the number of

black state and federal lawmakers in the former

Confederacy had plummeted to ten. The lone black

member of Congress, George White from North

Carolina, left office in 1901.

Blacks were not the only Americans subjected

to these indignities of second-class citizenship.

Following the Mexican-American War, the 1848

Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo granted citizenship to

thousands of Hispanics who were living in the areas

acquired by the United States. Thereafter, Mexican-

Americans in particular, and Hispanics and general

were saddled by a variety of state laws, including

literacy tests, specifically designed to prevent them

from exercising their right to vote. Chinese

Americans were also barred from voting during this

era. See Noting Rights Act: Section 203 Bilingual

Election Requirements: Hearing Before the Subcomm.

on the Constitution, H. Comm, on the Judiciary,

109th Cong, at 6 (November 8, 2005) (statement of

13

Rep. Mike Honda) (noting ongoing voting

discrimination faced by the Asian and Pacific

American community and observing that "Chinese-

Americans could not vote until the Chinese Exclusion

Acts of 1882 and 1892 were repealed in 1943" and

"[f]irst-generation Japanese-Americans could not vote

until 1952, because of the racial restrictions

contained in a 1790 naturalization law. . . ").

The ugly and prolonged period of racial

disfranchisement between 1877 and 1965 is

assailable both due to the denial of constitutional

rights and governance that remained largely

unresponsive to the concerns of minority citizens.

During these years, national and state government

actors embarked on programs that largely erased any

semblance of equality for non-whites. Meanwhile,

legislative efforts to prohibit lynching, segregation in

housing and education, and other indignities met

with incessant filibusters in the U.S. Senate leaving

millions of minority citizens without effective

representation or redress.

III. Congress Found That Minority Voters

Face Ongoing Voting Discrimination in

the Covered Jurisdictions

The historical record summarized above teaches

that backsliding and retrenchment in the absence of

Section 5 hold dire consequences for minority voters.

The potential for backsliding was a significant

concern in the 2006 Congressional decision to renew

the Act. Amici and other members of Congress also

heard testimony that helped illustrate these risks

14

from witnesses describing discriminatory voting

changes that the Section 5 preclearance provision

kept at bay. NAMUDNO v. Mukasey, 573 F. Supp.

2d 221, 247-265 (D.D.C. 2008) Although Congress

reviewed evidence from a variety of souces, amici

highlight three categories here:

1. Non-Compliance with Section 5

One category of evidence demonstrating the

ongoing need for preclearance enforcement is the

persistent unwillingness of some jurisdictions to

submit voting changes for review. As Congress

found, this resistance illustrates a naked refusal by

some jurisdictions to comply with the basic pre

approval requirements codified within Section 5. See

H.R. REP. No. 109-478, at 41-44 (2006); see also 152

Cong. Rec. H.5143 (daily ed. July 13, 2006)

(statement of Rep. F. James Sensenbrenner)

(“[Hjistory reveals that certain States and localities

have not always been faithful to the rights and

protections guaranteed by the Constitution, and some

have tried to disenfranchise African American and

other minority voters through means ranging from

violence and intimidation to subtle changes in voting

rules. As a result, many minorities were unable to

fully participate in the political process for nearly a

century after the end of the Civil War. The VRA has

dramatically reduced these discriminatory practices

and transformed our Nation's electoral process and

makeup of our Federal, State, and local

governments.”).

15

Three particular instances of non-compliance

deserve special note. First, officials in the state of

South Dakota made plain their disdain for the review

process by avoiding the preclearance mandate for

almost thirty years, leaving hundreds of voting

changes unexamined. Voting Rights Act: The

Continuing Need for Section 5: Hearing Before the

Subcomm. on the Constitution of the H. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 12 (2005) (statement of

Laughlin McDonald). Officials subsequently found

that several of these unsubmitted voting changes

threatened the rights of Native American voters.

Congress also found persuasive similar findings

made by this Court in Lopez v. Monterey County, 525

U.S. 266, 273 (1999), that officials in Monterey

County, California had wrongfully implemented state

election law changes that had not undergone

preclearance review. This Court also found that

related laws dating as far back as 1979 had not, but

should have been, submitted for federal preclearance.

H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 42 (2006). In addition,

Congress received evidence showing that federal

courts in Monroe, Louisiana enjoined local elections

in 1991 due to unreviewed changes in that

jurisdiction’s election scheme. Id. at 43; see also Brief

of Reps. John Conyers, Jr. et al. as Amici Curiae in

Support of Appellees at 17, NAMUDNO v. Holder,

No. 08-322 (2009).

Congress examined far more examples of

jurisdictions failing to comply with the mandate of

Section 5. But these examples are representative of

16

the kinds of cases that led Congress to find that more

time was needed to assess the effect of and

compliance with the preclearance mechanism in the

covered jurisdictions.

2. Continued Preclearance Objections

A second category of record evidence that

Congress reviewed is the significant number of

proposed election changes that warranted

preclearance objections. H.R. R e p . No. 109-478 at 21

(2006). More than four decades after the enactment

of Section 5’s preclearance requirement, some state

and local jurisdictions continue to invite multiple

objections. These objections offer extremely valuable

insight about the frequency with which the

preclearance remedy successfully prevents

discriminatory changes in the election process from

taking hold. See Brief for Intervenors-Appellees

Rodney and Nicole Louis, et al.; Lisa and David Diaz,

et al.; Angie Garcia, et al.; and People for the

American Way at 30-33, NAMUDNO v. Holder, No.

08-322 (2009) [hereinafter Brief for Intervenors-

Appellees],

The redistricting of Louisiana’s state legislature

offers one of the clearest examples of a state that has

been especially resistant to change. Every initial

redistricting plan adopted at the start of the decade

has failed to satisfy the requirements for

preclearance; indeed, the state has received at least

one objection for this plan in every cycle since 1965.

17

Reauthorizing the Voting Rights Act’s Temporary

Provisions: Policy Perspectives and Views from the

Field: Hearing on S. 2703 Before the Subcomm. on the

Constitution, Civil Rights and Prop. Rights of the S.

Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 132 (2006)

[hereinafter S. Hearing 109-822] (statement of Debo

P. Adegbile); Brief for Intervenors-Appellees, supra,

at 34—35,).

Other jurisdictions have shown a proclivity for

pursuing suspiciously-timed election changes. In

Freeport, Texas, for example, the Department of

Justice objected to a proposed change to an at-large

system in 2002, just after a Hispanic- preferred

candidate won office for the first time in a single

member district. To Examine the Impact and

Effectiveness of the Voting Rights Act: Hearing on

H.R. 9 Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution of the

H. Comm, on the Judiciary, 109th Cong. 7 (statement

of the Hon. Jack Kemp, former Member of Congress,

former Sec’y of Hous. & Urban Dev.) (2005); Voting

Rights Act: Section 5 of the Act—History, Scope, and

Purpose: Hearing on H.R. 9 Before the Subcomm. on

the Constitution of the H. Comm, on the Judiciary,

109th Cong. 47 (2005) (testimony of Anita S. Earls).

In Monterey County, California, a similar case

involved the local school board. There, white board

members sponsored a public ballot measure to

prevent more Hispanic- preferred candidates from

winning seats on that body. In objecting to that

change, the Attorney General found that the

proposed shift to at-large elections “contained

18

language that was expressed in a tone that ‘raises the

implication that the petition drive and the resulting

change was motivated, at least in part, by a

discriminatory animus.’” Renewing the Temporary

Provisions of the Voting Rights Act: Legislative

Options After LULAC v. Perry: Hearing on S. 2703

Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution, Civil Rights

and Prop. Rights of the S. Comm, on the Judiciary,

109th Cong. I l l (2006) (statement of Joaquin G.

Avila). In each instance, preclearance objections

helped to shield minority voters from the

discriminatory effects of proposed election changes.

3. Racially Polarized Voting

The Congressional record assembled evidence

that revealed the deleterious effects of pervasive and

persistent racially polarized voting in the covered

jurisdictions. H.R. Rep. No. 109-478, at 34—35 (2006).

Racially polarized voting facilitates purposeful

discrimination because it permits jurisdictions to

design methods of election or adopt devices that

interact with the polarization to prevent minority

voters from electing candidates of choice. Id, at 34.

Witnesses before Congress testified about several

cases in which racially polarized voting patterns

maintained an “election ceiling” that limited the

political opportunity for non-white voters and their

preferred candidates. Id. This pattern held true in

cases for voters in different minority communities.

As late as 2000, for instance, neither Hispanic nor

19

Native American candidates had ever won an election

in a majority-white election district. Id. Since 1966,

racial polarization remained a significant obstacle

across the South to the success of black candidates

for state legislative office outside of majority-black

constituencies: “There is little support for the

optimistic view that blacks will win many House

seats in white majority districts.” S. Hearing 109-822,

supra, at 183 (statement of David T. Canon).

Similarly, Hispanics are “rarely elected outside of

Latino majority districts.” Alvaro Bedoya, The

Unforseen Effects of Georgia v. Ashcroft on the Latino

Community, 115 YALE L.J. 2112, 2136 (2006).

Additional evidence heard by Congress adds

detail about the negative effects that polarization can

have on minority- preferred candidates. Congress

received testimony, for example from Professor

Theodore Arrington, describing polarization as “a

pervasive feature of American politics.” The

Continuing Need for Section 5 Pre-Clearance:

Hearing on S. 2703 Before the S. Comm, on the

Judiciary, 109th Cong. 9 (2006) (testimony of

Theodore S. Arrington).

There was also testimony that revealed the

continuing existence of outright racial appeals in

some jurisdictions— further evidence of continuing

voting discrimination. In fact, in one successful

campaign of a black candidate in North Carolina with

the last name “Campbell,” the candidate elected to

use a soup label rather than his own picture for all of

his campaign literature. Id. at 141 (statement of

20

Anita S. Earls). Another example concerns a white

voter in Southwestern Virginia who told a black

Congressional candidate, who had attended a local

political function: “It’s a pleasure to meet you. You

speak very well. You would have done a lot better if

you had not made an appearance here because you

have a white last name...and we’re all voting for

those candidates.” Id. at 140.

The examples described above are far from

exhaustive. See, e.g., Brief for Intervenors-Appellees,

supra, at 14-52. Indeed, other evidence considered by

Congress, and detailed in the parties’ briefs, includes

the Department of Justice’s requests for more

information (MIRs) regarding proposed voting

changes; the deployment of federal observers to

jurisdictions where minority voters face polling place

barriers; Section 5 enforcement actions; judicial

preclearance actions; and evidence yielded by

litigation under other provisions of the VRA,

including Section 2. Congress also heard powerful

and compelling evidence from a significant number of

witnesses, including constituents represented and

served by amici, who helped animate the experience

of minority voters throughout the covered

jurisdictions.

In its totality, the record presented to Congress

was replete with evidence showing problems that

were widespread, intransigent, and recent. These

lamentable findings quite vividly illustrate the extent

21

to which the preclearance requirement remains

necessary to accomplish the transformative goals of

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

IV. Preclearance Is a Crucial Tool for

Realizing America’s Democratic Goals.

Amici contend that the preclearance requirement

provides crucial protection for minority voters, many

who live in jurisdictions they represent and serve in

Congress. However, these voters are not the only

ones whose core political rights are at stake in this

case. The continued enforcement of Section 5 also

advances an even larger institutional goal that

inures to the benefit of every American citizen -

pluralist democracy. In this sense, Section 5 helps to

ensure that all citizens in the United States enjoy the

benefit of a more accessible and equal political

system.

Pluralist democracy recognizes the value of

diversity within the political process, which can help

produce a fuller, more comprehensive national policy.

This notion is not at all foreign to the reasoning that

led the Founders to establish the U.S. Constitution.

They envisioned a nation that was sensitive to

differences in ethnicity and class, and one that could

employ these diverse interests in its dynamic system

of governance and representation. One would be

hard pressed to find a better expression of the

pluralist ideal than in the motto E pluribus unum -

out of many, one.

22

This principle is especially important in

representative institutions like legislatures, whose

main goal is to address the needs of the public. As

House Minority Leader during the floor debate of the

2006 renewal, Representative Nancy Pelosi (D-CA)

conveyed this point well: “We all know that America

is at its best when our remarkable diversity is

represented in our Halls of power. We also know that

we will still have a great distance to go in order to

live up to our Nation's ideals of equality and

opportunity.” 152 CONG. R e c . H5162. (daily ed. July

13, 2006). A democratic institution based upon

pluralism provides the building blocks necessary for

politics to function well. Democratic pluralism helps

establish a level playing field for individuals with

cross-cutting interests and ideas to engage in the

“push[ing], haul[ing], and trad[ing]” that is commonly

associated with politics. See Johnson v. DeGrandy

512 U.S. 997, 1020 (1994). Put another way, it

provides the opportunity for coalition-building and

compromise to emerge.

Many of the views relevant to shaping public

policy are a function of life experience. Of course,

common experience is not always bound up with

membership in a particular racial group. However,

our nation’s history is a unique one in which race

has, at times, played a significant role in shaping life

opportunities and outcomes. Thus, race may be one

of the factors that inform perspectives and highlight

otherwise overlooked effects of a policy proposal. In

similar vein, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor

23

acknowledged the unique contributions to oral

arguments and this Court’s conferences that the late

Justice Thurgood Marshall imparted upon the court

precisely because of his “life experiences.” Sandra D.

O’Connor, Thurgood Marshall: The Influence of a

Raconteur, 44 STAN. L. Rev. 1217, 1217 (1992).

In all of the manners described above, theVoting

Rights Act helps government move closer to

achieving the goals of a pluralist democracy. It

establishes the forum for more meaningful

deliberation in institutions, encourages more

comprehensive and responsive policymaking, and

ultimately strengthens the bond of accountability

between voters and their governing institutions. As

our country grows increasingly diverse, our

governmental institutions must have the capacity to

respond to complex problems.

The genius in the design of our constitutional

system is that it remains open to innovative methods

of making our Union more perfect. The Voting

Rights Act and Section 5 are perhaps the best

examples of this commitment to improving our

democracy. Congress has, in light of historical

experience and ample evidence of the present effects

of long-term discrimination, found that the

preclearance requirement remains an effective tool in

this nation’s ongoing struggle to guarantee an equal

right to vote to all, regardless of race. Accordingly,

amici urge this Court to uphold Section 5 as a

reasonable exercise of Congressional power and as a

24

fully warranted effort by Congress to continue the

solemn task of perfecting our Union.

CONCLUSION

For all of these reasons, amici urge this Court to

uphold the decision below and find that the

preclearance provision remains a constitutionally

valid exercise of legislative enforcement authority

pursuant to the Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments.

Juan Cartagena

Counsel of Record

Com m unity Service

Society

105 East 22 Street

New York, NY 10010

(212) 614-5462

Respectfully submitted,

Kareem U. Crayton*

University of Southern

California Law School

699 Exposition Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA 90089

(213) 740-2516

March 25, 2009

* Assisted by Anna Faircloth (USC Law School, ’10) and

Katy Sharp (USC Law School ’10)

25

APPENDIX A

LISTING OF AMICI CURIAE

Tri-Caucus Chairs

Barbara Lee, Member of Congress and Chair,

Congressional Black Caucus (CBC)

Nydia M. Velazquez, Member of Congress and

Chair, Congressional Hispanic Caucus (CHC)

Michael M. Honda, Member of Congress and

Chair, Congressional Asian Pacific American

Caucus (CAPAC)

Congressional Black Caucus

Sanford D. Bishop, Jr., Member of Congress

Corrine Brown, Member of Congress

G.K. Butterfield, Member of Congress

Andre Carson, Member of Congress

Donna Christensen, Delegate to Congress

Yvette D. Clarke, Member of Congress

William Lacy Clay, Jr., Member of Congress

Emanuel Cleaver, II, Member of Congress

James E. Clyburn, Member of Congress

John Conyers, Jr., Member of Congress

Elijah E. Cummings, Member of Congress

Artur Davis, Member of Congress

Danny K. Davis, Member of Congress

26

Donna F. Edwards, Member of Congress

Keith Ellison, Member of Congress

Chaka Fattah, Member of Congress

Marcia L. Fudge, Member of Congress

A1 Green, Member of Congress *

Alcee L. Hastings, Member of Congress

Jesse L. Jackson, Jr., Member of Congress

Sheila Jackson-Lee, Member of Congress

Eddie Bernice Johnson, Member of Congress

Henry C. Johnson, Member of Congress

Carolyn Cheeks Kilpatrick, Member of Congress

John Lewis, Member of Congress

Kendrick B. Meek, Member of Congress

Gregory W. Meeks, Member of Congress

Gwen Moore, Member of Congress

Eleanor Holmes Norton, Delegate to Congress

Donald M. Payne, Member of Congress

Charles B. Rangel, Member of Congress

Laura Richardson, Member of Congress

Bobby L. Rush, Member of Congress

David Scott, Member of Congress

Robert C. Scott, Member of Congress *

Bennie G. Thompson, Member of Congress

Edolphus Towns, Member of Congress

Maxine Waters, Member of Congress

Diane E. Watson, Member of Congress

Melvin L. Watt, Member of Congress

27

Congressional Hispanic Caucus

Joe Baca, Member of Congress

Xavier Becerra, Member of Congress *

Dennis A. Cardoza, Member of Congress

Jim Costa, Member of Congress

Henry Cuellar, Member of Congress

Charles A. Gonzalez, Member of Congress

Raul M. Grijalva, Member of Congress

Luis V. Gutierrez, Member of Congress

Ruben Hinojosa, Member of Congress

Ben Ray Lujan, Member of Congress

Grace F. Napolitano, Member of Congress

Salomon P. Ortiz, Member of Congress

Ed Pastor, Member of Congress

Pedro R. Pierluisi, Member of Congress

Silvestre Reyes, Member of Congress

Ciro D. Rodriguez, Member of Congress

Lucille Roybal-Allard, Member of Congress

Gregorio Sablan, Member of Congress *

John T. Salazar, Member of Congress

Linda Sanchez, Member of Congress

Jose E. Serrano, Member of Congress

Albio Sires, Member of Congress

28

Congressional Asian Pacific American

Caucus

Neil Abercombie, Member of Congress

Xavier Beccerra, Member of Congress

Madeleine Z. Bordallo, Delegate to Congress

Eni F.H. Faleomavaega, Member of Congress

A1 Green, Member of Congress

Mazie K. Hirono, Member of Congress

Doris O. Matsui, Member of Congress

Gregorio C. Sablan, Member of Congress

Robert C. Scott, Member of Congress

David Wu, Member of Congress *

*Also a Member of the CAP AC

29

APPENDIX B*

Racial Gaps In Voter Registration &

Turnout

’ Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Table A l. Located at

h ttp :. w w w .c e n s i i s .a o v / D Q P u l a t i o n / w w w / s o c o>. .

http://www.censiis.aov/DQPulation/www/so