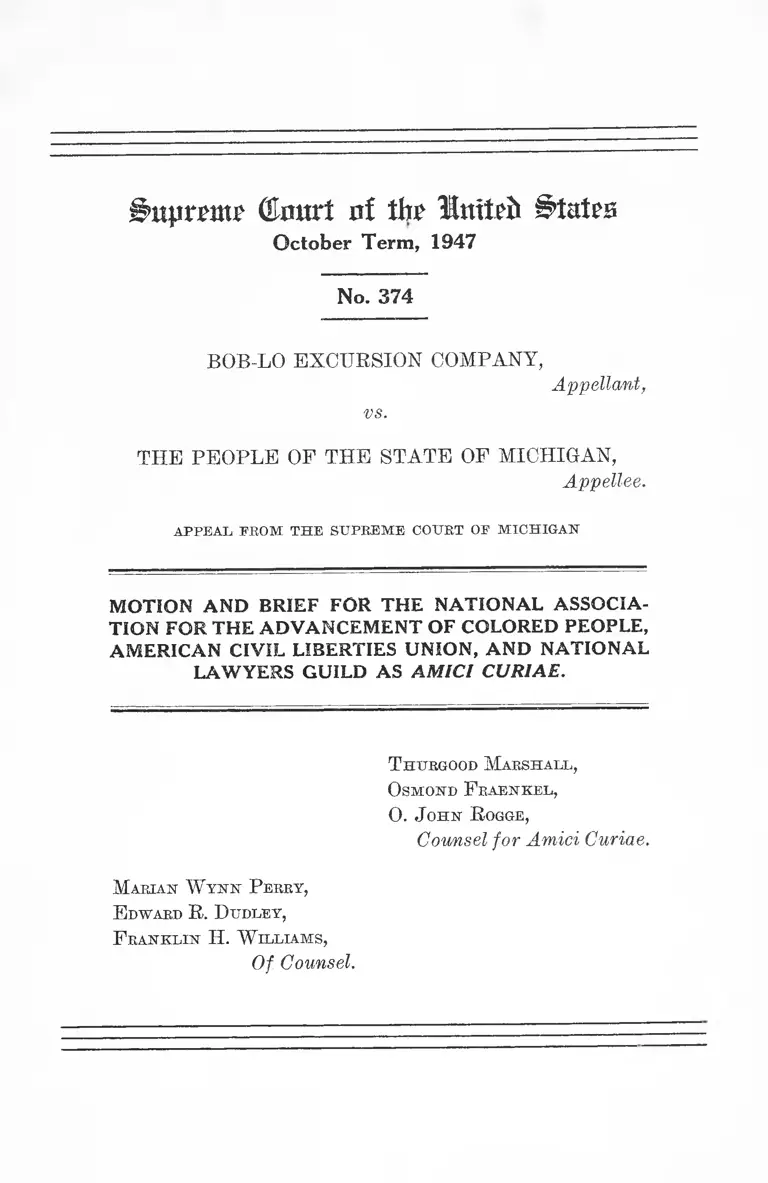

Bob-Lo Excursion Company v. People of the State of Michigan Motion and Brief for the NAACP, American Civil Liberties Union, and National Lawyers Guild as Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1947

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bob-Lo Excursion Company v. People of the State of Michigan Motion and Brief for the NAACP, American Civil Liberties Union, and National Lawyers Guild as Amici Curiae, 1947. 4f368b0a-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e0edd8aa-f616-4791-93e5-3e6335cfc56a/bob-lo-excursion-company-v-people-of-the-state-of-michigan-motion-and-brief-for-the-naacp-american-civil-liberties-union-and-national-lawyers-guild-as-amici-curiae. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

Srij.tmm' (Emtrf of f e United States

October Term, 1947

No. 374

BOB-LO EXCURSION COMPANY,

Appellant,

vs.

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF MICHIGAN,

Appellee.

A P P E A L PR O M T H E S U P R E M E CO U RT OP M IC H IG A N

MOTION AND BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIA

TION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, AND NATIONAL

LAWYERS GUILD AS AMICI CURIAE.

T hurgood M arsh a ll ,

O sm ond F r a e n k e l ,

O. J o h n R ogge,

Counsel for Amici Curiae.

M arian W y n n P erry ,

E dward R . D udley ,

F r a n k l in H. W il l ia m s ,

Of Counsel.

I N D E X

PAGE

M otion ___________________________________________________ 1

Motion for Leave to File Brief as Amici Curiae___ 1

B r i e f _____ ________________________________________________ 3

Opinions Below ___________________________ 3

Statute Involved ___________________________ 3

Question Presented____________________________ 3

Constitutional Provision and Statute Involved____ 4

Statement of tlie Case________________________ 4

A r g u m e n t :

I—Analysis of appellant’s claim of unconstitu

tionality _______________________________ 5

II—The Michigan Civil Rights Statute may consti

tutionally be applied to the appellant herein___ 6

The State of Michigan may in the absence of

federal legislation remove obstacles to the

free flow of interstate and foreign commerce.. 11

Conclusion ________________________________ 14

11

Table of Cases

PAGE

Civil Eights Cases, 109 U. S. 3------------------------------- 7

Cooley v. Port Wardens, et al., 12 How. 299------------- 6

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160----------------------- 9

Ex Parte Endo, 323 I T . S. 283____________________ 10

Gilman v. Philadelphia, 3 Wall. 713------------------------ 11

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 IT. S. 485____________________ 6, 7,8

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81---------------- 10

Illinois C. E. Co. v. Illinois, 163 U. S. 142_______ ___ 13

In Be Drnmond Wren, 4 D. L. R. (1945) 674-------------- 13

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214-------------- 10

Monongahela Navigation Co. v. U. S., 148 U. S. 312----- 11

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373------------6, 7, 8,10,13,14

Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88--------- 9

Sands v. Manistee Eiver Improvement Co., 123 U. S. 288 11

Southern Pacific v. Arizona, 325 U. S. 761_________ 7

Steele v. L. & N. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192_______________ 10

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen & En-

ginemen, 323 U. S. 210________________________ 10

Wisconsin v. Duluth, 96 U. S. 379--------------------------- 11

Other Authority

Dowling, Interstate Commerce and State Power-Re

vised Version, 47 Col. Law Rev. 547 (1947)_______ 7

Statutes.

Racial Discrimination Act, Session Laws of Province of

Ontario, 1944, Chapter 51-------------------------------- 12

United Nations Charter, Article 55, Article 56_______ 13

U. S. Constitution, Article I, Section 8 (3)---------------- 4

Michigan Statutes Annotated (1946), Sections 28.343_ 4

Supreme ( to r t nf tljr Itutrft ^tatrs

October Term, 1947

No. 374

B ob-L q E xcursion C o m pa n y ,

Appellant,

vs.

T h e P eo ple op t h e S tate of M ic h ig a n ,

Appellee.

A PPEA L PR O M T H E S U P R E M E CO U RT OP M IC H IG A N

MOTION AND BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIA

TION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, AND NATIONAL

LAWYERS GUILD AS AMICI CURIAE.

Motion for Leave to File Brief as Amici Curiae.

To the Honorable the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

The undersigned, as counsel for and on behalf of the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the

National Lawyers Guild, respectfully move that this Honor

able Court grant'them leave to file the accompanying brief

as amici curiae.

2

Consent of the attorney for the appellant and the attor

ney for the appellee to the filing of this brief has been

obtained.

Special reasons in support of this motion are set forth

in the accompanying brief.

T hukgood M a rsh a ll ,

O sm ond F r a e n k e l ,

0 . J o h n R ogge,

Counsel for Amici Curiae.

© o u r ! n f tty H tt t f r f c S t a t e s

October Term, 1947

No. 374

B ob-L o E xcu rsio n C o m pa n y ,

vs.

Appellant,

T h e P eo ple of t h e S tate of M ic h ig a n ,

Appellee.

A PPEA L FR O M T H E S U P R E M E COU RT O F M IC H IG A N

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, AMERICAN

CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, AND NATIONAL LAWYERS

GUILD AS AMICI CURIAE.

O pinions Below.

S ta tu te Involved.

The opinion below and the statute involved are set forth

in full in the record and in the briefs for both parties filed

herein.

Q uestion Presented.

The Specification of Errors urged by appellant is sum

marized by it as follows: “ The questions here presented to

3

4

the Court are in reality but one, viz: the Michigan Civil

Bights Statute is either unconstitutional as violating the

commerce clause of the Federal Constitution, or at least

may not constitutionally be applied to defendant when en

gaged in its foreign commerce business.” 1

Constitutional Provision and Statute Involved.

The United States Constitution Article I, section 8, (3)

provides: “ Congress shall have power . . . (3) to regulate

commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several

states . . . ”

The Michigan Civil Rights Statute provides:

“ All persons within the jurisdiction of this state

shall be entitled to full and equal accommodations,

advantages, facilities and privileges of inns, hotels,

restaurants, eating houses, barbershops, billiard

parlors, stores, public conveyances on land and water,

theatres, motion picture houses, public educational

institutions, in elevators, on escalators, in all methods

of air transportation and all other places of public

accommodation, amusement, and recreation, where

refreshments are or may hereafter be served, subject

only to the conditions and limitations established by

law and applicable alike to all citizens and to all citi

zens alike, with uniform prices” (Act No. 117, Pub.

Acts 1937; Stat. Ann. 1946, Cum. Supp. Sec. 28.343).

Statement of the Case.

The appellant herein is a private corporation for profit

organized “ to lease, own and operate amusement parks in

Canada and to charter, lease, own and operate excursion

steamers and ferry boats in interstate and foreign com

merce, together with dock and terminal facilities pertaining

thereto . . . ” (R. 5).

1 Appellant’s brief, page 4.

5

In June, 1945, its agents compelled a Negro, the com

plaining- witness, to disembark from one of its ships while

at the wharf in Detroit and denied her accommodations on

its ship solely because of her race or color. It is admitted

that the refusal to carry the complaining witness as a pas

senger was pursuant to an established policy of the appel

lant not to permit Negroes to be passengers on its boats

(R. 10,11).

The trip in question was one of the usual trips made by

appellant’s steamers from Detroit to Bob-Lo Island in

Canadian waters. During the trip the boats are part of the

time in Canadian waters and part of the time in United

States waters. Appellant does not carry any passengers

from Canada to the island but carries only passengers from

Michigan to the island on round-trip tickets.

Because of the refusal to carry the complaining witness

as a passenger on one of its steamers solely because of her

race or color, appellant was prosecuted and convicted under

the Michigan Civil Rights Statute. The conviction was

affirmed by the Supreme Court of Michigan and on appeal to

this Court probable jurisdiction was noted.

ARGUMENT.

I.

Analysis of appellant’s claim of unconstitutionality.

The argument of appellant is divided into two points (a)

appellant is engaged in foreign commerce; (b) the Michi

gan Civil Rights Statute involved may not constitutionally

be applied to appellant when engaged in sncli foreign com

merce on account of the commerce clause of the Federal

Constitution.

6

The Supreme Court of Michigan held that appellant in

the instant case was engaged in foreign commerce (R. 39),

The real contention of appellant is that since it is engaged in

“ foreign commerce” it is subject only to possible regula

tion by Congressional action and that in the absence of Con

gressional action regulating them it is free to exclude pas

sengers solely because of race or color. Of course, the tech

nical position of the appellant is that for the above reasons

it is not subject to liability under the Michigan Civil Rights

Statute.

The appellant relies almost entirely upon the decisions of

this Court in Hall v. DeCuir 2 and Morgan v. Virginia.3

II.

The Michigan Civil Rights Statute may constitu

tionally be applied to the appellant herein.

It is the contention of the appellant that in the absence

of specific federal legislation the question of the selection

of passengers is left to the unrestrained will of appellant.

The position of appellant on this point is in direct oppo

sition to a long line of decisions of this Court which affirm

the doctrine set forth in the case of Cooley v. Port Wardens,

et al., 12 How. 299, that the granting to Congress of the

power to regulate interstate and foreign commerce did not

of itself deprive the states from exercising authority over

this subject matter.

Where a state statute is challenged as violating the

commerce clause each case must be considered on its own

facts with this Court as the final arbiter as to whether the

2 95 U. S. 485.

3 328 U. S. 373.

7

particular statute violates the commerce clause.4 In the

absence of an affirmative showing of a burden on interstate

or foreign commerce there can not be a violation of the

commerce clause. Where the facts of the particular case

establish a “ burden” on interstate or foreign commerce,

this Court must then weigh the interests of the state and

the national interests.5

It is the policy of appellant of excluding all Negroes

from its ships which obstructs the free flow of passengers

in commerce. On the other hand, the Michigan statute pro

hibiting such a policy is an aid to the free flow of commerce.

In the instant case the interest of the State of Michigan

in enforcing its civil rights statute is in furtherance of the

purpose of the national interests. The purpose of the

Michigan Civil Eights Act is to prohibit individuals and

corporations carrying on businesses of public accommoda

tion therein mentioned from doing what the state is pro

hibited from doing under the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution.6

The appellant herein relies on Hall v. DeCuir and

Morgan v. Virginia, and insists that on the basis of these

two cases this court must hold that the Michigan Civil

4 Southern Pacific v. Arizona, 325 U. S. 761; Morgan v. Virginia,

328 U. S. 373; see also Dowling, Interstate Commerce and State

Power—Revised Version, 47 Col. Law Rev. 547 (1947).

5 Ibid.

6 The Michigan Civil Rights Act, originally enacted in 1885, is

designed to implement the Fourteenth Amendment in areas where

the Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, specifically held the federal

government could not act. Thus the acts of appellants prohibited by

the Michigan act are those of which this Court stated individuals

“must be amenable therefor to the laws of the state where the

wrongful acts are committed,” at p. 17.

8

Eights Statute involved in this case cannot constitutionally

be applied to it.

In the case of Hall v. DeCuir, the Louisiana statute pro

hibited segregation on common carriers because of race, but

this court found that the statute violated the commerce

clause because the carrier operated between Louisiana and

Mississippi, which latter state might subsequently adopt a

regulatory statute differing from the one in Louisiana.

However, since the decision in Hall v. DeCuir, this court has

consistently followed the rule that each case must be consid

ered on its own facts and that state statutes regulating com

merce will only be declared unconstitutional as in violation

of the commerce clause where the facts in the particular

case clearly demonstrate the existence of a burden on inter

state or foreign commerce and that the burden is inconsis

tent with national interests.

In the case of Morgan v. Virginia, this Court made an

independent examination of the effect of the statute to de

termine whether it unduly burdened commerce. The statute

requiring the segregation on motor carriers and requiring

the driver of the vehicle to shift passengers according to

race was compared with the varying types of statutes in

existence in states bordering Virginia, as well as other

states in which the carrier operated. This Court also ex

amined the statutes of those states which also made varying

definitions of the word “ Negro.” After considering these

factors this Court found that the Virginia statute did place

an unreasonable burden on interstate commerce. On the

other hand, in the instant case the Michigan statute removes

9

all possible burdens of this type by prohibiting segregation

and such a statute is clearly not a burden on commerce but

an aid to the free flow of commerce.

If a state statute which requires a carrier to provide its

passengers with separate accommodations according to their

race and color is void as applied to interstate carriers be

cause it puts an unconstitutional burden on them, to say

that a state statute which in effect prohibits such a burden

is likewise a burden on interstate commerce is clearly a

non sequitur.

This Court has always fully protected goods moving in

interstate commerce from discriminatory regulations by

carriers and states. There is a higher national interest in

volved in protecting the “ right of persons to move freely

from state to state” than is present in cases concerning the

movement of goods.7

7 See concurring opinions in Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160.

In upholding a section of the New York Civil Rights Act, Mr.

Justice R e e d , speaking for the majority of the court, stated, “We

see no constitutional basis for the contention that a state cannot pro

tect workers from exclusion solely on the basis of race, color or creed

by an organization, functioning under the protection of the state,

which holds itself out to represent the general business needs of

employees”. Railway Mail Association v. Corsi, 326 U. S. 88, 94.

And in a concurring opinion in the same case, Mr. Justice F r a n k

f u r t e r stated, “Certainly the insistence by individuals on their pri

vate prejudices as to race, color or creed, in relations like those now

before us, ought not to have a higher constitutional sanction than

the determination of a State to extend the area of non-discrimination

beyond that which the Constitution itself exacts;” Ibid, at page 98.

10

In determining the relative weights of state and national

interests as to “ state safety regulations” of interstate car

riers, this Court has followed its rule of considering each

case on its own merits and has thereby upheld such regula

tory statutes as those involved in the full train crew laws

while declaring invalid state laws limiting the number of

cars on railroad trains.

On the question as to who shall be transported in inter

state commerce and the manner in which passengers shall

be transported, there is also a recognizable difference in the

type of statute involved in the Morgan case and the type of

statute involved in this case. The national interests in

volved in the method of handling passenger traffic are two

fold: (1) there is the over-all national interest of free flow

of commerce, and (2) there is the national interest that no

distinction because of race, color or national origin shall be

permitted in areas subject to national control.

Despite the absence of a requirement for equal protec

tion of the laws in the Fifth Amendment, our national gov

ernment is prohibited from making distinctions on the basis

of race and color since such distinctions are considered ar

bitrary and inconsistent with the requirements, of due

process except where national safety and the perils of war

render such measures necessary.8

8 Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81; Korematsu v. United

States, 323 U. S. 214; Ex parte Endo, 323 U. S. 283; and see also:

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co., 323 U. S. 192; Tunstall v.

Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen & Enginemen, 323 U. S. 210.

11

The State of Michigan may in the absence of

federal legislation remove obstacles to the free

flow of interstate and foreign commerce.

By delegating to the federal government the power to

regulate interstate and foreign commerce, the several states

intended to keep the channels of commerce “ open and free

from obstruction . . . imposed by the state or otherwise.” 9

It was not intended, and such delegation has never been

construed by this Court, to remove from the states all power

to act in relation to interstate commerce, hut rather to give

the federal government the power “ to remove such obstruc

tions when they exist and to provide . . . against occurrence

of the evil and the punishment of offenders.” 10

That the states may improve navigable waters by the

erection of docks and the removal of obstructions to com

merce is unquestioned. Thus, in Monongahela Navigation

Co. v. U. 8.,11 this Court said of the action taken under state

authority to build locks improving the river that ‘ ‘ The legis

lature of the state creating this corporation . . . has come

in aid of Congress.” 12

Similarly, in Sands v. Manistee River Improvement

Company,13 this Court found that a state statute organizing

a corporation and authorizing it to collect tolls for the cut

ting of channels and removal of obstructions in a navigable

river did not conflict with the power of Congress to regulate

such waters in the absence of Congressional action. The

Court reiterated the principle that the constitutional pro-

9 Gilman v. Philadelphia, 3 Wall, 713, 725.

i°

11 148 U. S. 312.

12 Ibid., 334. See also Wisconsin v. Duluth, 96 U. S. 379.

13123 U. S. 288.

12

visions “ did not contemplate that such navigation might

not be improved by the removal of obstructions.” 14

The free flow of commerce, which the federal government

has an interest to maintain and a right to regulate, can be

hampered as well by the discriminatory refusal of a carrier

to transport as by physical obstructions. Since the states

may, in the absence of federal action, enact laws and author

ize the erection of docks, dams, locks and other physical

improvements, and may remove obstructions in the form of

adverse currents, shallow channels, log jams, etc., in aid

of interstate and foreign commerce, the state may likewise

act “ in aid of Congress” to remove the obstruction to com

merce caused by appellant’s absolute refusal to transport

Negroes.

The simple fact is that only by compliance with the

Michigan Civil Eights Act can commerce be freed; only in

securing compliance with this or a similar statute can com

merce be increased by the transportation of additional

classes of persons, and all this will be done in furtherance

of commerce, rather than in obstruction of it.

The appellant placed much emphasis upon the “ foreign”

or “ international” nature of their enterprise to substanti

ate their claim of exemption from the anti-discrimination

provisions of the Michigan Civil Rights Act. Quite the op

posite result flows, however, from the international aspects

of this case from that desired by the company. In the first

place, the province of Ontario has had an anti-discrimina

tion law since 1944 15 forbidding publication of discrimina

tory advertisements, notices, symbols or emblems, and in

1945 an Ontario court held that the participation of Canada

14 Ibid.

15 Racial Discrimination Act, Session Laws 1944, Chap, 51.

13

in the United Nations had unalterably fixed the public policy

of Ontario and the Dominion in opposition to racial discrim

ination 16. The requirements of the Michigan Civil Rights

Act are, therefore, in conformity with the provisions of

Ontario statutes and common law and no burden is placed

upon the appellant by the requirement that it not discrim

inate against prospective passengers.

Furthermore, all that appellant is asked to do under the

Michigan Civil Rights Act is to cooperate in carrying out

the obligations of this country under the United Nations

Charter of which both the United States and the Dominion

of Canada are signatories. Thus, Articles 55 and 56 of the

United Nations Charter provide that each member of the

United Nations shall take joint and separate action to pro

mote “ universal respect for and performance of human

rights and fundamental freedoms for all, without distinc

tion as to race, sex, language or religion” .

In view of the decision of this Court defining the nature

of burdens upon commerce, under the facts in this case, no

burden is imposed. Thus, it cannot be said that the provi

sions of state law forbidding discrimination “ impair the

usefulness of [the] facilities” 17 of a carrier which passes

between two ports only, each of which is in a country pledged

by the United Nations Charter to oppose racial discrimina

tion. Furthermore, it cannot be said that the anti-dis

crimination provision in any way “ infringes the require

ments of national uniformity” 18 of the United States, in the

light of the provisions of the United Nations Charter.

18 In re Drummond, Wren, 4 D. L. R. (1945) 674.

17 Illinois Central R. Co. v. Illinois, 163 U. S. 142, 154.

18 Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 385.

14

Conclusion.

This Court in the light of its recent decisions should de

termine that the Michigan Civil Rights Act far from being

unconstitutional (1) is in fact an aid to the free flow of com

merce ; and, (2) is in keeping with the national interest not to

discriminate, because of race, creed or national origin. Thus

segregation statutes similar to the one involved in the

Morgan case are unconstitutional while statutes similar to

the Michigan one are valid.

It is therefore respectfully submitted that the appeal

should be dismissed.

Respectfully submitted,

T htjrgood M a rshall ,

O sm ond F r a e n k e l ,

O. J o h n R ogge,

Counsel for Amici Curiae.

M arian W y n n P erry ,

E dward R. D u d ley ,

F r a n k l in H. W il l ia m s ,

Of Counsel.

»212 [6362]

L awyers P ress, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C.7 ; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300