Eastland v. Tennessee Valley Authority Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

May 20, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Eastland v. Tennessee Valley Authority Brief Amicus Curiae, 1983. 45f1ed6d-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e0f9084a-99a9-41fa-a425-2f5e7c61e3e3/eastland-v-tennessee-valley-authority-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

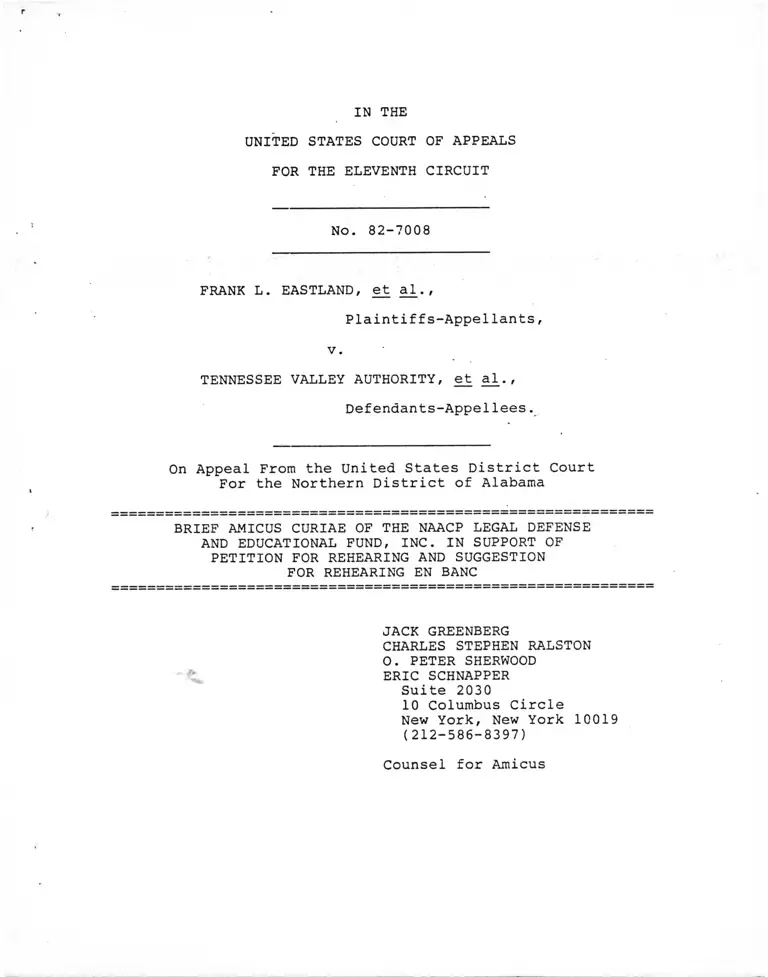

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 82-7008

FRANK L. EASTLAND, et al. ,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Alabama

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. IN SUPPORT OF

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESTION

FOR REHEARING EN BANC

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

0. PETER SHERWOOD

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212-586-8397)

Counsel for Amicus

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 82-7008

FRANK L. EASTLAND, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal From the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Alabama

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. IN SUPPORT OF

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND SUGGESTION

FOR REHEARING EN BANC

The amicus NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., submits this brief because of our ongoing respon

sibilities as counsel in a substantial number of Title VII

and other discrimination cases now pending in this circuit

and this court. We urge that rehearing be granted in this

case, not because the panel opinion is necessarily incorrect,

although we believe that is the case, but because the reasoning

of that opinion is as baffling as it is far reaching. The

opinion's often contradictory statements of legal principles,

at times compounded by the manner in which those principles

are applied, will necessarily produce enormous confusion

among litigants and the lower courts regarding how discrim

ination is to be proved, who is entitled to challenge discrim

inatory practices, and under what conditions trial court

findings may be affirmed on appeal. We set out below the

novel questions raised, but not answered, by the panel opinion.

We believe that the efficient administration of justice

would be best served if the May 2 opinion were modified to

make clear here and now what it has decided, rather than

leaving that task for "clarification" over a period of years

by panels with other membership and perhaps different views.

(1) what are the appropriate standards for

determining the scope of a class?

The district judge in this case drastically narrowed

the scope of the proposed class. Progressively eliminated

from the group of blacks that the named plaintiffs could

represent were employees outside the OACD department, employees

represented by the Tennessee Valley Trades and Labor Council,

managerial employees, unsuccessful applicants, and administrative

employees. (P. 2868). After insisting on "careful attention

to the requirements of Rule 23," the May 2 opinion concludes

that the trial court "did not abuse its discretion in narrow

ing the class" (P. 2869). What those requirements are, and

what standards are to be applied to any exercise of trial

court discretion, are critical to the correctness of the

panel decision, and to its significance for future trial and

appellate litigation.

-2-

The decision's analysis of these requirements and

standards, however, which we would have thought central to

the appeal, is limited to an assertion that the trial judge

determined that "the representative parties lacked sufficient

nexus with the putative class members to adequately protect

their interests." (Id..) The panel explains neither what

it believes, or what the trial court believed, this "nexus"

test to require. The result is worse than merely obscure,

for although this analysis is opaque by itself, the facts

disclosed by other aspects of the opinion raise even more

questions. There is, for example, considerable controversy

about when in a Title VII action successful applicants can

represent a class that includes unsuccessful applicants; in

this case, however, one of the named plaintiffs, Eastland,

was an unsuccessful applicant. If applicants cannot represent

applicants, who can? The exclusion of TVA employees outside

the OACD department would appear to have some basis if there

were no questions of law or fact common to both OACD and

non-OACD employees. But the panel opinion itself holds,

correctly in our view, that proof of discrimination against

non-OACD employees is "corroborative evidence" relevant to

the claims of black OACD workers. (P. 2872). If the exis

tence of such common issues does not provide the requisite

"nexus," what more was required?

As counsel for plaintiffs in a number of class actions

now pending in this circuit, we are unable to discern from

-3-

the May 2 opinion what type of evidence is now necessary or

even relevant to determining the scope of a class. Since

the actual circumstances of this case appear to provide

precisely the elements hitherto thought sufficient for a

certification including at least some of the excluded groups,

no trial judge in this circuit can reasonably be expected to

understand the new rules for defining the scope of the class.

Any defendant could find in the panel opinion some basis for

insisting that a trial court enjoys unlimited and standardless

discretion to define a class as narrowly as it pleases. The

panel may not have intended to establish such a rule, or to

revolutionalize or even alter the standards for certifying

or defining a class, but the language and details of its

opinion invite the contrary conclusion.

(2) Where a plaintiff has shown that black employees

earn significantly less than whites, how many.

possible reasons for that difference must it

eliminate in order to establish a prima facie

case of discrimination?

Here, as in many other Title VII cases, the plaintiffs

sought to prove the existence of racial discrimination by

showing that black employees earned less than whites. The

plaintiffs, of course, did not limit their case to this

disparity alone; they also affirmatively established that

the wage differential was not the result of differences in

seniority or education, since the disparity remained even

when these circumstances were taken into account. The issue

on appeal was what more, if anything, plaintiffs were re

quired to prove.

-4-

The difficulty with this aspect of the May 2 decision

is not that it fails to articulate any relevant standard,

but that it appears to announce four different rules. TVA

objected to plaintiffs' statistics because they did not take

into consideration possible differences in the employees'

pre-TVA work experience. The panel rejected this contention,

insisting that if a defendant believed such an additional

variable would explain away the wage disparity, the defendant

could not merely speculate that that might be the case, but

had the burden of adducing credible evidence to support its

claim:

In light of the fact that TVA's own regressions

did hot account for this variable ... the omission

should not have substantially impaired the validity

of Eastland's model. "A defendant's claim that the

plaintiff's model is inadequate because a variable

. has been omitted will ordinarily ride on evidence

showing (a) that the qualification represented by

the variable was in fact considered, and (b) that

the inclusion of the variable ... changes the results

of the regression so that it no longer supports the

plaintiff." (P. 2874, n. 14) (emphasis added).

Elsewhere, in discussing promotion discrimination, the opinion

indicates there may be some important exculpatory explanations

that a plaintiff must disprove even if the defendant itself

never offers evidence to support them; plaintiff's statistics

regarding promotion rates, this passage suggests, must be

limited to individuals with "the minimum objective qualifica

tions necessary for one to be eligible for promotion." (P.

2877) (Emphasis deleted). Third, the court states that the

value of a statistical analysis "depends in part upon the

inclusion of all major variables likely to have a large

effect" (P. 2875, see also id. n. 15); on this view a plaintiff

is not required to disprove any particular non-racial explanation,

-5-

but the number and significance of the factors the plaintiff

does prove irrelevant determine the weight to be given to

the plaintiff's statistical evidence. Finally, a fourth

passage appears to hold that a plaintiff must consider each

and every conceivable non-discriminatory cause for the salary

disparities, and affirmatively demonstrate that none of them

was responsible for these differences. Thus the panel held

that proof of average wage disparities between blacks and

whites of equal length of service, job schedule, and education,

did "not demonstrate discrimination because the other factors

%

which influence salary are not considered." (P. 2872)

The differences among these standards is of critical

importance to the resolution of many if not most Title VII

cases. If a plaintiff is required, in order to establish a

prima facie case of discrimination, to disprove in advance

every possible non-racial explanation for differences in the

treatment of blacks and whites, proof of discrimination will

be virtually impossible. If there are certain "important"

defense explanations which a plaintiff must anticipate and

disprove, the opinion provides no guidance as to what they

are. In the face of this opinion, plaintiffs' counsel cannot

know what they are required to prove to establish a prima

facie case, defense counsel cannot know when they are

obligated to put on a case of their own, and the trial courts

are told only that there are at least four possible standards

for assessing evidence of this kind.

-6-

(3) May present employees challenge discrimination in their

initial assignments?

Prior to the decision in this case there was, so far as

we are aware, no dispute that if an employee was assigned to

a job on the basis of race, he or she could bring suit under

Title VII. Such discrimination traditionally occurs during

the initial assignment of new workers. Many of the Title

VII cases in this circuit, and the old Fifth Circuit, involved

attempts by blacks to win the right to move into jobs which

had traditionally been reserved i*n this way for whites.

In this case, however, the district court forbad present

employees from litigating such assignment claims. The panel

opinion summarizes and appears to approve the district court

action in the following language:

The certification order limited the class to past

and present employees, thereby excluding hiring

or applicant claims. The district court refused

to consider the initial assignment claims because

they were "applicant claims" .... [T]he finding that

... initial assignment is part of the hiring process

is not clearly erroneous. (P. 2871, n. 9)

The rule apparently sanctioned by the court of appeals is

that the legality of a practice injuring members of a class

cannot be litigated on behalf of the class if that same

practice also injures individuals who are not members of the

class. OACD's insistence that it hires applicants "for

specific positions" is not, of course, different in kind

from the widespread pre-1965 practice of hiring blacks

for certain positions and whites for others. We do not

-7-

understand what legally relevant meaning could be given to a

finding that "initial assignment is part of the hiring process."

If, as part of the hiring process, newly selected employees

are assigned to jobs on the basis of race, it is those employees

who are injured by that practice. Except where assignment

policies affect hiring decisions because only "white" positions

are vacant, assignment practices would not themselves injure

unsuccessful black applicants who were rejected on account

of race; thus in many cases unsuccessful applicants would

lack standing^to challenge assignment practices. If success

ful applicants cannot challenge such discriminatory practices

because the practices are "part of the hiring process," and

unsuccessful applicants cannot challenge them for want of

standing, no one can attack them at all. Read literally,

the panel opinion appears to hold that at times, either as a

matter of law or in the discretion of the trial court,

discrimination in initial assignment is simply immune from

attack. Since the panel cannot have intended to legalize

this form of discrimination, the meaning of its opinion is

entirely unclear.

The unusual conclusions to which this approach leads

are illustrated by the panel's discussion of the promotion

claims of plaintiff Nash. Nash complained that he had been

denied promotion into an M schedule job because of his race.

The panel opinion notes:

-8-

In defining the class the district court excluded

employees on the M schedule and subsequently ruled

that promotions to the M schedule were not a part

of the case. We have already determined that the

court did not abuse its discretion in narrowing the

class. (P. 2880)

The logic of the discussion of assignment claims is here

taken to the natural but extreme conclusion that an in

dividual who is the victim of discrimination cannot

challenge that discriminatory practice if it also injured

other individuals who are not part of a certified class.

Here, as with assignments, the panel cannot conceivably have

intended to announce or approve such a rule, but what it did

intend the quoted passage to mean is a matter of conjecture.

(4) Can proof of discrimination in promotion or assignments

be proved by disparities in overall wages

Part 1(c)(1) of the May 2 opinion holds unequivocally,

and correctly in our view, that proof of disparities in the

salaries of blacks and whites may be used to establish dis

crimination in promotions or assignments:

Higher salaries generally coincide with higher

level jobs. If blacks at TVA earn less than

whites it is because they are assigned to lower

ranking, lower paying positions (p. 2872)

The panel noted that Fifth Circuit precedent supports the

use of wage disparities to prove such discrimination. (Id.)

The panel's analysis of the record in this case, however,

appears to disavow this standard. Plaintiff offered a statis

tical analysis of OACD wages which showed that blacks were

paid less than whites even when education, length of service,

and "a large number of variables" were taken into account.

-9-

(P. 2876). The panel, however, dismissed this evidence of

discrimination because it failed to "control for job category."

(Id.) There are five job schedules and several score job

categories within the relevant units of OACD. "Controlling

for job category" meant that allegedly underpaid blacks were

compared only with whites in the'same job category, not with

similarly or less qualified whites in other job categories.

Thus the TVA analysis relied on by the panel demonstrated

decisively that the differences in the wages of comparable

black and white employees were due in large measure to the

fact that a disproportionate number of whites were in»the

better paid categories, while blacks were more frequently in

the lower paid job categories.

This analysis might weigh in favor of the defendant if

the plaintiffs were complaining only about promotion dis

crimination within each category, not between categories,

and if the categories were so different (e.g. lawyers,

physicists, foreign language translators) that no employee

ever moved from one to the other. In fact, however, promo

tions did occur into the better paying job categories (see,

e.g., P. 2880), and the existence of discrimination in such

promotions was expressly alleged by the plaintiffs (Id.).

Thus, although salary disparities may in theory be used

to prove discrimination in promotions and assignments, that

evidence can, in light of the May 2 decision, be "rebutted"

by a showing that the reason blacks make less is "simply

because they are more highly represented" (P. 2876) in the

poorly paid jobs due to disparities in assignment or promotion.

-10-

This "rebuttal" consists of precisely the kind of discrim

ination the plaintiff is seeking to prove. The panel's

actual resolution of the case seems squarely.to make proof

of such discrimination literally self-defeating.

(5) Does Pullman-Standard Co. v. Swint apply to affirmances

of erroneous trial court decisions?

In Pullman-Standard Co. v. Swint, 72 L.Ed. 2d 66 (1982),

the Supreme Court delineated the respective roles under the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure of the federal district

courts and courts of appeals. Where the trial court's decision

is tainted by some error, the court of appeals is not ordinarily

authorized to decide on its own the factual questions at

issue, or to speculate about how the district court would

have decided the case had that error not occurred or about

how the lower court might act on remand. Puliman-Standard

appears to sanction the affirmance of a trial court's conclu

sion on the merits only under two circumstances: (1) where

those conclusions, and the premises on which they are based,

have been found to be correct as a matter of law and not

clearly erroneous as a matter of fact, and (2) where, although

there were lower court errors, the record would compel in a

second appeal the ultimate conclusion initially reached by

the trial court even if, on remand, that court were to arrive

at the opposite result. In all other situations a case must

be remanded for a fresh decision by the district court.

The affirmance in this case, however, falls into neither

of those categories. It introduces and turns on two apparently

novel doctrines, — first, that certain allegedly erroneous

findings relied on by the trial court need not be reviewed

-11-

if they are "surplusage," and second, that a trial court's

refusal to consider relevant evidence may at times be "not

error." Both doctrines seem outside the language, and incon

sistent with the reasoning, of Puliman-Standard.

The plaintiffs in this court attacked the trial court's

subsidiary findings regarding promotion rates and labor

market comparisons; the panel, rather than undertaking to

decide whether the findings were correct, expressly "disregard[ed]

these findings as surplusage." (P. 2877 n. 18). If evidence

regarding promotion rates was irrelevant, the trial court

errred by relying on it; if such evidence was indeed relevant,

the correctness of the trial court's ultimate conclusion

necessarily turned on whether it had properly resolved the

disputes regarding that evidence. Either way it is difficult

to understand how that conclusion of non-discrimination

could be upheld without an examination of the allegedly

faulty premises on which it was based.

A similar problem is raised by the district court's

dismissal as "irrelevant" of proof of discrimination against

blacks outside of the OAC department. (P. 2872, Data Set

B). The panel found that this evidence "could have been

considered as corroborative evidence," i.e. that it was

relevant, but also held that its rejection "was not error."

(Id.) How a refusal to consider relevant evidence can be

"not error" is not explained. The trial court in any event,

did not think it could consider such evidence; whether, in

light of appellate direction to do so, it might have reached

the same ultimate conclusion on the merits is a matter of

speculation.

-12-

Although the "surplus finding" and "not error" rule

appear critical to the outcome of the panel decision, neither

their rationale nor their scope is explained. Both open new

questions, to which they provide no answers, regarding

whether trial judges, or district court litigants, are

really obligated to conform their actions to the substantive

legal standards announced by the appellate courts. Both

raise novel issues, which they do not purport to resolve,

about the degree to which erroneous district court decisions

are now-to be exempt from reversal or even scrutiny.

For the above reasons the petition for rehearing should

be granted, and the case reheard en banc.

CONCLUSION

Respectfully submitted

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

0. PETER SHERWOOD

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212-586-8397)

Counsel for Amicus

-13-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 20th day of May, 1983, I

served three copies each of the Brief Amicus Curiae of the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., and a copy

of the Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae, on

counsel for the parties, by causing them to be deposited in

the United States mail, first class postage prepaid, addressed

to:

Paul Saunders Cravath Swaine & Moore

One Chase Manhattan Plaza

New York, New York 10005

Richard T. Seymour

Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights

Inder Law

733 Fifteenth St., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005 •

Herbert S. Sanger, Jr.

General Counsel

Tennessee Valley Authority

Knoxville, Tennessee 37902

Bernard E. Bernstein

Bernstein, Susano, Stair & Cohen

Sixth Floor

First Tennessee Bank Building

Knoxville, Tennessee 37902

Melvin Radowitz

Jacobs & Langford, P.A.

1000 Rhodes-Haverty Building

134 Peachtree St., N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303