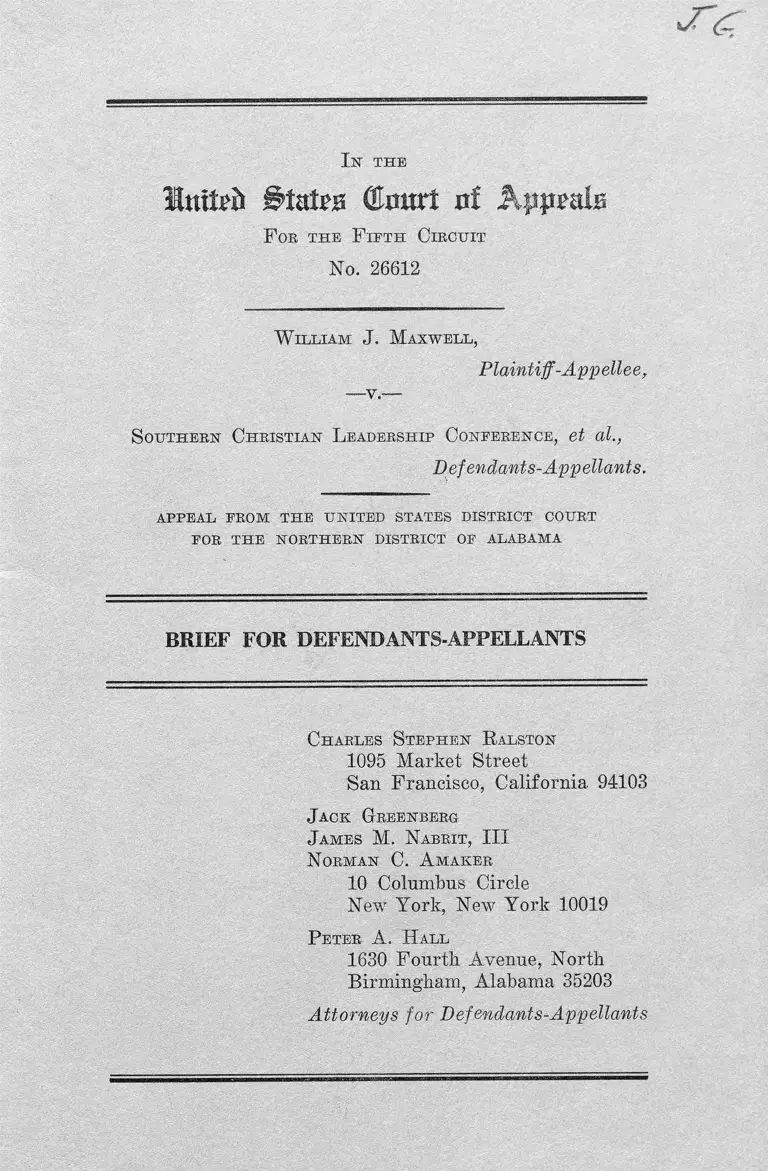

Maxwell v. Southern Christian Leadership Conference Brief for Defendants-Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 2, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maxwell v. Southern Christian Leadership Conference Brief for Defendants-Appellants, 1968. d1c5a644-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e13609e8-8d0a-4dfe-8e31-33b2d39382d6/maxwell-v-southern-christian-leadership-conference-brief-for-defendants-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

BUUb (Emtrt uf Kppmlz

F oe th e F if t h Circu it

No. 26612

W illiam J . M axw ell ,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

S outhern C h ristian L eadership C onference, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

A P PE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTR IC T COURT

FOR T H E N O R T H E R N D ISTR IC T OF ALAB A M A

BRIEF FOR DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

Charles S teph en R alston

1095 Market Street

San Francisco, California 94103

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

N orman C. A m akeb

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

P eter A. H all

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Defendants-Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of the Issues Presented for R eview ....... . 1

Statement of the Case ........ ....... ...................................... 2

Statement of the Facts ............ .......................................... 4

Introduction .................................................................. 4

1. The Liberty Supermarket Demonstrations ..... 6

2. The Events of February 22, 1968 ....................... 10

A rgu m en t

Introduction.................................................... 14

I. The Evidence Does Not Show That Any Agents

or Employees of Appellant Were Authorized to

Take Part in Its Behalf in the Demonstrations

in Question Here ...................................................... 15

II. The Evidence Was Insufficient in Law and Fact

to Establish Liability for Plaintiff’s Injuries Be

cause of the Acts of SCLC Employees Either

for Negligence or for the Establishment of a

Nuisance ...................................................................... 22

III. The Evidence Was Insufficient to Support the

Amount of Damages Awarded ................................. 27

IV. The Granting of Damages Against SCLC Here

Constituted an Abridgement of Rights of Free

Speech and Assembly Protected by the First and

Fourteenth Amendments ........ 29

Conclusion ................ 33

Certificate of Service.......... ....... ....... ...... ..................... . 34

11

T able of C ases

PAGE

Brazier v. Cherry, 293 F.2d 401 (5th Cir. 1961) ........... 15

Foster & Creighton Co. v. St. Paul Mercury Indemnity

Co., 264 Ala. 581, 88 So.2d 825 (1956) ....................... 25

McPherson v. Taniiami Trailways, Inc., 383 F.2d 527

(5th Cir. 1967) .................... ........... -.......... -.................. 15, 21

Martin v. Anniston Foundry Co., 259 Ala. 633, 68 So.2d

323 (1953) ....... .................. ........................................-...... 16

Morgan v. City of Tuscaloosa, 268 Ala. 493, 108 So.2d

342 (1959) ..................-...................................................22,25

NAACP v. Overstreet, 221 Ga. 16, 142 S.E.2d 816

(1965), cert. dism. as imprevidently granted, 384

IT.S. 118 (1966) ..................... .........................................30,31

Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F.2d 110 (5th Cir. 1963) ........... 15

New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964) ....... 29

Perfection Mattress & Spring Co. v. Windham, 236

Ala. 239, 182 So. 6 (1938) .......................................... 16

Republic Iron & Steel Co. v. Self, 192 Ala. 403, 68 So.

328 (1915) ......................................................................16,17

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ........................... 29

Sullivan v. Alabama Power Co., 246 Ala. 262, 20 So.2d

224 (1945) ..... ............. ......... ............................................. 22

Trans-America Insurance Co. v. Wilson, 262 Ala. 532,

80 So.2d 253 (1955) ........................... ..................... .....15,16

PAGE

Wade v. Brisker, 233 Ala. 585, 173 So. 64 ................... 19

Walker Comity v. Davis, 221 Ala. 195, 128 So. 144

(1930) ....... ........... ........ ............. ...................................... 25

Wells v. Henderson Land & Lumber Co., 200 Ala. 262,

76 So. 28 (1917) ..... ........ ........................ .................... . 16

Whiteman v. Pitrie, 220 F.2d 914 (5th Cir. 1955) .......21, 27

Wilson & Co. v. Clark, 67 So.2d 898 (1953) ............... 19

Ill

In the

Irntfii BUUb (tart of Appeals

F ob, th e F if t h C ibchit

No. 26612

W illiam J. M axw ell ,

— v . —

Plaintiff-Appellee,

S outhern C hristian L eadership Conference, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

appeal ebom th e united states distbict court

EOB T H E N O R T H E R N DISTRICT OF ALAB A M A

BRIEF FOR DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

Statement of the Issues Presented for Review

1. Did the court below err in denying defendant-appel

lant’s motions for directed verdict, judgment notwith

standing the verdict, and for a new trial, made on the

grounds that under the lav/ and the evidence the defen

dant corporation could not be held liable for injuries

suffered by the plain tiff-appellee ?

2. Was the verdict of the jury, both as to holding

defendant-appellant liable and as to the amount of dam

ages, supported by the law and the evidence?

3. Were defendant-appellant’s rights under the First

Amendment denied by the awarding of damages against

it as a result of its activities as shown by the evidence?

2

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from the denial of motions for a

directed verdict, a judgment notwithstanding the verdict,

and for a new trial and from the jury verdict in a civil

action for damages. This action was begun by a three-

count complaint by plaintiff-appellee, William J. Maxwell,

against the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

(S.C.L.C.), defendant-appellant, and unnamed persons

(Sup. App. 7-9j.1 The said unnamed persons were never

identified during the course of this action and no other

parties were ever joined as defendants.

The action was originally brought in state court, the

plaintiff alleging that the defendant had negligently and

intentionally caused injuries to be inflicted on the plain

tiff. A petition for removal was filed in the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Alabama on

the grounds of diversity of citizenship, the plaintiff being

a citizen of the State of Alabama and the defendant a

corporation organized under the laws of the State of

Georgia with its offices there (S.A. 1-5). The required

jurisdictional amount was satisfied since the action sought

$150,000 worth of damages on each count. The plaintiff

did not contest the removal of the action.2

1 The record on appeal is reproduced in two appendices. All

references herein will be to the second, the Supplemental Appendix

(S.A.) which contains all pleadings as well as the transcript of

testimony at trial.

2 The defendant challenged service of process in the action on

the ground that it was not doing any business in the State of

Alabama at the time of the filing of the action so that there was

no jurisdiction in either the state or federal court over it. After

receiving affidavits from both sides on the motion, the district court

ruled against the defendant. This question is not at issue in the

present appeal.

3

Following a pre-trial conference and discovery, trial was

had in this case on March 4 and 5, 1968 before a jury.

On the day of the trial the plaintiff filed an amendment

to his complaint dropping the original two counts and

substituting three others therefor. The district court al

lowed only two of the amended counts, one alleging neg

ligence on the part of the defendant and the other alleging

that defendant created a nuisance which resulted in in

juries to the plaintiff (S.A. 60-64). Prior to trial, defen

dant filed a motion to dismiss on the ground of failure

to state a cause of action and a general denial of all

material allegations in the complaint. In addition, de

fendant raised an affirmative defense, viz., that at all

times complained of, the defendant was engaged in acts

protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to

the Constitution of the United States and hence could not

be held liable in damages (S.A. 55-56). At the close of

the evidence in the case, defendant moved to amend its

answer to raise the additional defense of contributory

negligence and assumption of risk by the plaintiff. The

district court allowed the motion and instructed the jury

on that question (S.A. 322).

At the trial defendant made an oral motion for a di

rected verdict at the close of the plaintiff’s evidence (S.A.

260). It renewed its motion at the close of its case and

before the matter was submitted to the jury. This motion

was taken under advisement by the court and was subse

quently reduced to writing and filed with the court (S.A.

324; S,A. 68). The jury found for the plaintiff on both

counts and returned a verdict of $45,000 (S.A. 66-67).

Within ten days after the return of the verdict, the de

fendant filed a motion for judgment notwithstanding the

verdict, renewing its motion for a directed verdict made

at the close of the testimony, or, in the alternative, for

a new trial (S.A. 74-82). The district court denied all the

4

motions of the defendant on the condition that the plain

tiff remit the amount of his medical costs since he was

treated at a Veterans Administration hospital (S.A. 84-

85). Upon a remittitur being made by the plaintiff, a judg

ment was entered in the amount of $41,000. A timely no

tice of appeal was tiled by the defendant and a supersedeas

bond was filed and approved by the district court in the

amount of $45,000 (S.A. 87-90).

Statement of the Facts

Introduction

In February, 1966, demonstrations were held on the

premises of the Liberty Supermarket, a store in the Negro

section of Birmingham, Alabama. The demonstrations

were to protest an incident which had occurred at the

Supermarket sometime earlier in which Negro customers

had been arrested following an altercation with store

policemen. In addition, the demonstrations protested the

lack of employment of Negroes in the store, approximately

seventy-five percent of whose customers were Negroes.

On February 22, 1966, plaintiff, who is also a Negro, went

to Liberty Supermarket and parked his car in the lot

while a demonstration was taking place. While he re

mained in his car, another car driven by a white customer

left the parking lot. In so doing, it drove through a line

of marchers who, at the time, were proceeding through

the lot. When the car got to the exit and was waiting

for automobile traffic to allow him to proceed, a group of

demonstrators and pickets on the sidewalk came up to the

car. Subsequently, the following events, which will be set

out in more detail below, took place. The white driver, who

had no connection with S.C.L.C. or with the demonstration,

fired from seven to eight shots into the crowd of Negro

5

demonstrators. One of the bullets bit and injured tbe

plaintiff who bad gotten out of bis car to observe what

was happening.

One year later, tbe plaintiff filed the present action

against tbe Southern Christian Leadership Conference,

alleging that it was responsible for bis injuries. The com

plaint as amended sought recovery on two bases. One was

that defendant SCLC had negligently caused a condition

to arise which resulted in injuries to him and thus violated

its legal duty to insure his safety. The second count al

leged that SCLC had created a nuisance which it should

have known would result in danger to persons in the

vicinity and, as a result of which, plaintiff suffered in

juries.

At trial, a number of matters were in dispute. These

included: first, the extent to which, if any, SCLC was

engaged in the planning, sponsoring, or carrying out of

the demonstration; second, the events of February 22nd,

plaintiff’s actions on that evening and the participation,

if any, of any persons connected with SCLC in the dem

onstrations then; and third, whether the actions of SCLC’s

employees, to the extent they participated in the Liberty

Supermarket demonstrations at all, were protected by the

First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

and hence could not result in civil liability.

The remainder of this statement of facts will be divided

into two main parts. The first will deal with the back

ground of the demonstrations at the Liberty Supermarket

and evidence regarding SCLC’s participation in them; the

second will deal specifically with the events of February

22, 1966, the evening on which plaintiff was injured.

6

1. The Liberty Supermarket Demonstrations

Liberty Supermarket is located in an area in Birming

ham, Alabama, in which Negroes primarily reside. Most

of its customers are Negro residents of the area. Early

in 1966 an incident occurred at the Supermarket in which

a number of Negro shoppers were arrested after an alter

cation with a store policeman. Considerable feeling was

generated within the Negro community because of the

incident and because no Negroes were employed by the

store as full-time cashiers (S.A. 264).

As a result, meetings were held at various Negro churches

at which persons attending were urged to participate in

demonstrations at the store to protest the conditions there.

Witnesses testified concerning meetings during the week

of February 18, 1966 (S.A. 98; 111; 126). The meetings

were described as being regularly scheduled evening meet

ings whose purpose was to discuss matters of interest to

the Negro community, particularly relating to civil rights

(S.A. 108-109). Apparently the issues of greatest impor

tance at the time were the Liberty Supermarket matter and

a voter registration drive being conducted in Birmingham

by the defendant-appellant, Southern Christian Leadership

Conference (S.A. 121; 135).3

Various speakers would address the meetings with re

gard to the matters of interest, including both the regis

tration effort and the demonstrations at Liberty. Predom

inant among these were ministers of local Negro churches,

including the Beverends J. E. Lowery, Fred Shuttlesworth,

and Edward Gardner (S.A. 104; 109; 127). These three

were also members of or connected with the Interdenomi

3 The ultimate result of the voter registration drive was the

sending of federal registrars into Birmingham pursuant to the

Voting Rights Act of 1965.

7

national Ministerial Alliance of Greater Birmingham and

Jefferson County and the Alabama Christian Movement

for Human Rights (S.A. 128; 264; 277). Both organiza

tions are composed primarily of local Negro ministers.

In addition, the three ministers are associated in some

capacity with the Southern Christian Leadership Confer

ence (S.C.L.C.).4 Reverend Lowery was, in 1966, on the

board of directors of the corporation and was, at the time

of trial in this case, chairman of the board (S.A. 261-62).

Reverend Shuttlesworth was secretary of the corporation,

and Reverend Gardner was a member of a local planning

committee when S.C.L.C. held its national convention in

Birmingham in August, 1965 (see, Plaintiff’s Exhibit 1,

pp. 6, 11).

Reverends Gardner and Lowery testified directly, how

ever, that their activities with regard to the Liberty Super

market demonstrations were in no way connected with

their relationships with S.C.L.C. Rather, they were act

ing as private citizens, as ministers, and as leaders of

the Birmingham Negro community and of the local organ

izations (S.A. 264; 152; 269-272). As to Reverend Shuttles

worth, the police officer called as a witness by the plain

tiff testified that there was nothing in his notes of Shut-

tlesworth’s speech that indicated that he was speaking

about Liberty Supermarket with relation to S.C.L.C.

Rather, “his speech was made as an individual.” (S.A.

135.)

All three ministers participated in organizing and car

rying out the demonstrations at Liberty. They spoke at

their and others’ churches urging persons to take part

and led demonstrations on various days. Reverend Gard

4 S.C.L.C. is a corporation organized under the laws of the State

of Georgia, with its offices in Atlanta.

8

ner was in charge of the pickets on the night of the in

cident here in question, February 22, 1966. He testified

that the pickets had been instructed to be nonviolent and

peaceful, and to the best of his knowledge these instruc

tions were carried out (S.A. 274-275). Reverend Lowery

testified that although he had picketed on other occasions

at Liberty he was not there on February 22nd when the

shooting of the plaintiff took place (S.A. 144-145; 155-156).

There was testimony that Reverend Shuttlesworth was at

the scene of the shooting, but after it took place. It was

not clear whether he arrived before or after the incident

(S.A. 242-243; 256-257).

The evidence regarding the connection of SCLC with

the Liberty Supermarket demonstrations was as follows.

SCLC is a corporation organized under the laws of the

State of Georgia. It is not a membership organization,

but, like other corporations, has officers and employees

(S.A. 288-289). An employee of SCLC, Hosea Williams,

was in Birmingham at the time. Mr. Williams is director

of Voting Registration for the corporation (see Plaintiff’s

Ex. 1, p. 12). He had been assigned to Birmingham, along

with a few SCLC workers, by the corporation as part of

a voter registration campaign being conducted by it in

Alabama and Birmingham during the last months of 1965

and the first months of 1966 (S.A. 263-264). The testimony

was that this was the only activity he had been sent to

Birmingham to carry out.

In furtherance of the registration drive, Mr. Williams

would appear at meetings in various Negro churches in

the community. On February 18, 1966, he spoke at such a

meeting when both voter registration and Liberty Super

market were discussed. During his speech he talked about

voter registration, in connection with which, according to

9

a police officer who attended, he referred specifically to

SCLC (S.A. 120-121). He also spoke about Liberty Super

market, but made no reference to SCLC (S.A. 123). He

called for persons to go to the Supermarket the next day,

February 19th, and to demonstrate in order to end dis

criminatory hiring practices (S.A. 105). In addition, there

was some testimony that Mr. Williams actually went to

the Supermarket to take part in demonstrations at some

unspecified date (S.A. 140). However, there was no evi

dence that he, or any other SCLC employees, were there

on February 22nd before the incident in question here,

but only that two employees, not including Mr. Williams,

were seen there some time after the shooting in the crowd

that had gathered (S.A. 243-44; 255). Indeed, all who

testified as to the events of February 22nd said that they

had not seen him there. Nor was there any testimony

that he or any other SCLC employees had been involved

directly in the organization or direction of the demon

strations on that particular evening.

In addition to this testimony, there was introduced into

evidence by plaintiff a copy of a press release that had

been handed out prior to the shooting, on February 18

(Plaintiff’s Exhibit 26). The release deplored the in

cident involving customers and a store policeman and

complained of the lack of employment of Negroes as

cashiers. The release stated that negotiations had failed

and called for the Negro community to withdraw from

patronizing the store until certain demands were met. At

the bottom of the release appeared five names, including

Hosea Williams’, Reverend Lowery’s, and Reverend Gard

ner’s. No organizational affiliations were given, nor was

any claim made that the five were speaking on behalf of

any organization (S.A. 251-252).

10

A television reporter testified that at some time during

this period, either before or after the shooting, he spoke

with Mr. Williams. He stated that Mr. Williams told

him that:

There had been a group picketing there who Hosea

indicated to us, or told me that they had some in

volvement with, in other words, he said it was

S.C.L.C............ (S.A. 250).

Finally, there was introduced into evidence, as plain

tiff’s Exhibit 5, a button showing two clasped hands with

“ SCLC” and “Southern Christian Leadership Conference”

on it. A police officer testified that he had seen persons

engaged in the demonstrations wearing such buttons and

had picked up one from the supermarket’s parking lot

(S.A. 163). Reverend Lowery testified that the buttons

had been donated to SCLC and were handed out freely

across the country at public meetings. Thus, anyone at

tending such meetings could acquire a button and wear it

at any time (S.A. 267-268).

Eventually the dispute between the Negro community

and the supermarket was resolved through negotiations.

A Negro attorney who handled the negotiations for Liberty

testified that he negotiated solely with representatives

from the local community. At no time were representa

tives of SCLC involved, and SCLC was not a party to

the final agreement (S.A. 291).

2. The Events o f February 22, 1968

On the evening of February 22, 1966, there were demon

strations at Liberty Supermarket. Sometime during the

day or early evening a group of pickets began to march

along the sidewalk. According to a witness, Mr. Simon

11

Armstrong, who relieved another person on the picket

line at about eight o’clock, the picketers remained on the

sidewalk since they had instructions not to go on the

supermarket premises (S.A. 300-301). Reverend Gardner

was in charge of these pickets, and he testified that they

were under instructions to be nonviolent and peaceful at

all times (S.A. 274-275). There was no evidence that any

employees of SCLC participated in, directed, or controlled

any of the demonstrations that day, or that any were

on the scene until after the shooting took place. Indeed,

Mr. Armstrong testified that he was there because he had

heard his pastor and other local ministers ask for people

to picket (S.A. 299).

Shortly before 10:00 p.m. another group of Negroes,

variously estimated as being between 75 and 150 strong,

marched through the parking lot (S.A. 159; 168-169). At

the same time an automobile driven by a white man, who

apparently had just left the supermarket, began moving

out towards the exit to the street. It was testified that

the motor was loud and was being raced (S.A. 160-161).

When the driver came to the group marching through the

lot, he slowed the car, raced its motor, and passed through

the line of marchers (Ibid). One witness testified that

some demonstrators had to jump out of the car’s path

(S.A. 179). Two witnesses testified that some people in

the group yelled something at the car as it passed through

(S.A. 161; 175). The car proceeded through the exit from

the parking lot until it was blocking the sidewalk. It

stopped, evidently waiting for a break in the traffic along

the street so that it could proceed (S.A. 179).

At this point, a number of things occurred. The per

sons who had been picketing had ceased, and were walking

up the sidewalk in a group to go to a prayer meeting. The

automobile was blocking their way and they stopped until

12

it passed (S.A. 301-304). One witness, who was within five

or six feet away, testified that he heard no one shout at

the ear at this point and saw no one touch it (S.A. 305).

At the same time, persons from within the parking lot

came up to the car (S.A. 161-162). Apparently, this group

included persons who had been in the line of march through

which the car had passed as well as at least some persons

who were merely watching the demonstrations (S.A. 169;

179).

A number of witnesses testified that they saw the rear

lights of the car moving up and down and back and forth.

They surmised from this that the car was being rocked

by people in the crowd around the car (S.A. 175; 161).

At least one of the witnesses, however, admitted that the

movement of the lights could have been caused by the

driver making the car go backwards and forwards (S.A.

172-173). Another witness testified that this in fact was

what the driver was doing (S.A. 312). Witnesses also

testified that they heard persons in the crowd shout “ get

him,” while one witness said that there were no shouts

prior to the shooting but that afterwards some persons

shouted “get the license number” as the car drove away

(S.A. 200; 313).

In any event, while the crowd was around the car the

driver fired a volley of about five shots into it (S.A. 199).

There was a pause of some indeterminate length and

then three or four more shots were fired, making eight

or nine in all (S.A. 166; 175; 199). About five persons

were wounded by the shots, including a witness at the

trial, Mr. Simon Armstrong, and the plaintiff-appellee,

Mr. William J. Maxwell. There was no evidence that the

gunman was connected in any way with S.C.L.C. or with

the demonstration.

13

The plaintiff testified as to his own acts on the evening

as follows. He went to Liberty Supermarket at about ten

minutes to ten ostensibly to do some shopping (S.A. 190).

When he arrived at the store he parked a short distance

inside the entrance and close to the demonstrators, even

though there were only eight to ten other cars and he

could have gotten close to the store itself (S.A. 199; 167).

Even though the store closed at ten o’clock, the plaintiff

did not get out of his car to proceed with his shopping.

Instead, he remained in his car for five to ten minutes

admittedly watching the demonstrators (S.A. 207). He

saw the other automoble go through the line of marchers

and stop at the exit. He testified that he saw the people

come up around the car and rock it. He then heard five

pistol shots fired (S.A. 208-209). Instead of remaining in

his car where he was safe, he got out, apparently trying

to see what was going on. There was a second volley of

shots, and he was hit by one of the bullets (S.A. 208-209).

The plaintiff received serious injuries to his internal

organs which required two operations at the local Veterans’

Administration Hospital. As a result he was not able to

work for a considerable period of time during which his

employer lent him twenty-five dollars a week which he

has been paying back since he returned to work. He is

now working as a truck driver and laborer, at which job

he from time to time lifts fairly heavy objects. He is re

ceiving a higher pay now than he was before the shooting

(S.A. 193-198; 201-202). A physician testified that it could

not be said whether plaintiff would have to continue having

a drainage tube in his body, since often such wounds heal

sufficiently after the passage of time (S.A. 224-226). No

evidence was introduced as to whether plaintiff’s lifespan

or earning capacity had been shortened, although he did

testify that he still had difficulty sleeping.

14

ARGUMENT

Introduction

Basically, the defendant-appellant contends that in this

case the plaintiff has sued the wrong defendant. As it has

been shown by the statement of facts, and as it will be more

fully developed below, the defendant Southern Christian

Leadership Conference (S.C.L.C.) was not responsible

either in fact or in lawT for plaintiff’s injuries. The proper

defendant should have been the man—whose identity is

known—who fired the shot that injured William Maxwell.

One can only speculate as to why SCLC was sued. It was

probably assumed that a judgment could be won against a

prominent civil rights organization in a case involving a

civil rights demonstration. SCLC, then led by the late Dr.

Martin Luther King, Jr., had been active in Alabama over

a period of time attempting to achieve racial justice, spe

cifically in the area of voting. The action was brought

against it even though it is clear that the demonstrations

were planned, led, and carried out by people in the local

community because of grievances that affected them and

which they felt should be corrected.

Thus, this case raises an important and significant issue

—whether an organization can be subjected to onerous legal

judgments on no more basis than its continuing efforts,

protected by the constitutional guarantees of freedom of

speech and assembly, to achieve racial justice. The future

of attempts to bring about political and social change in

our society by legal means may well hang in the balance.

In arguing that the judgment below must be reversed

and that either a judgment for defendant or a new trial

must be granted, appellant SCLC recognizes its burden

when faced with an adverse jury verdict. However, deci

15

sions of this Court make it clear that even a jury verdict

must comport with the law and the evidence. Brazier v.

Cherry, 293 F.2d 401 (5th Cir. 1.961); Nesmith v. Alford,

318 F.2d 110 (5th Cir. 1963); McPherson v. Tamiami Trail-

ways, Inc., 383 F.2d 527 (5th Cir. 1967). In arguing why

the verdict was erroneous, there will be discussed issues of

traditional private and business law—questions of the au

thority of an agent, probable cause, independent interven

ing cause, etc. However, again, the real issue here is wheth

er the effective exercise of rights protected by the First

Amendment may be crippled by the stretching of a tenuous

and fragile chain of causation.

I.

The Evidence Does Not Show That Any Agents or

Employees o f Appellant Were Authorized to Take Part

in Its Behalf in the Demonstrations in Question Here.

The defendant-appellant, SCLC, is a corporation. As

such, of course, it can act only through its agents, employ

ees, and officers. See, e.g., Trans-America Insurance Co. v.

Wilson, 262 Ala. 532, 80 So.2d 253 (1955). In this part of

the argument, appellant will show that there was insufficient

evidence to support any finding that any agent was acting

within the scope of his authority insofar as he may have

participated in the Liberty Supermarket demonstrations.

Therefore, no tort liability could be imposed on the cor

porate defendant. In part II of the argument it will be

shown that even assuming authority to act on behalf of

SCLC, the acts of its employees were not sufficient to estab

lish responsibility for plaintiff’s injuries.

A. The law of Alabama, which governs here, as to the

tort liability of a corporation is essentially the same as

16

other states and may be briefly stated. A corporation can

act only by and through its duly authorized officers and

agents. However, the fact that the persons whose actions

are complained of are employees of or are connected in

some way with the corporation is not enough, The corpo

ration can he held liable in tort only as a result of acts by

agents done within the line or scope of the duties and au

thority given by it. Trans-America Insurance Co. v. Wilson,

supra. Moreover, even where the activities of the employee

or agent are similar to those within the scope of his em

ployment, if they are shown to be done for or in conjunc

tion with others and not within the scope of employment,

the corporation will not be liable. Martin v. Anniston

Foundry Co., 259 Ala. 633, 68 So.2d 323, 327 (1953). See

also, Perfection Mattress & Spring Co. v. Windham, 236

Ala. 239, 182 So. 6, 8 (1938).

And, as was stated in an early decision:

The principal is responsible, not because the servant

acted in his name, or under color of his employment,

but because the servant was actually engaged in and

about his business and carrying out his purposes. Re

public Iron & Steel Co. v. Self, 192 Ala. 403, 68 So.

328, 329 (1915).

If, on the other hand, the employee is not engaged in the

corporation’s business, but is “ impelled by motives that are

wholly personal to himself,” then his commission of a tor

tious act is purely his personal wrong. Ibid. See also, Wells

v. Henderson Land & Lumber Co., 200 Ala. 262, 76 So. 28

(1917).

Finally, the burden of introducing competent evidence

demonstrating that the employee was acting within the

scope of his authority is on the plaintiff. Trans-America

Insurance Go. v. Wilson, 262 Ala. 532, 80 So.2d 2oo (19o5).

17

Thus,

[T ]o authorize the submission of the question to the

jury, the evidence must tend to show that the wrong

was committed by the agent while he was executing

his agency, and not from a motive or a purpose of his

own, having no relation to the business of the master.

Republic Iron & Steel Go. v. Self, 192 Ala. 403, 68 So.

328, 329 (1915).

B. The issue thus presented is, in light of the above

principles, was there evidence showing that any persons

directed or led the demonstrations involved here while act

ing as agents of defendant-appellant and within the scope

of their employment and the authority given them by SCLC.

The testimony at trial focused on two groups of persons

who might be considered to be agents. The first consisted

of the local Negro ministers, Reverends Lowery, Gardner,

and Shuttlesworth. The second consisted of individuals who

admittedly were SCLC employees, Hosea Williams and two

or three persons working under him on a voter registration

drive.

Whether the three ministers were acting as agents of

SCLC may be quickly disposed of. Reverend Gardner, who

was in charge of the demonstrations on the night in ques

tion, February 22nd, testified positively that he was acting

as a private citizen, as a local minister, and with and on

behalf of local organizations of ministers. He denied that

he was working with or on behalf of SCLC. There was no

evidence whatsoever that he was an employee or officer of

the corporation. The only connection he was shown to have

had with it was that in the summer of 1965 he was a mem

ber of a local planning committee in connection with SCLC’s

national convention held in Birmingham that year (PI. Ex.

1, p. 11). There was nothing to show any continuing au

18

thority of any sort, much less authority in February of

1966 to conduct the Liberty Supermarket demonstrations in

the name of or in behalf of SCLC.

As to Reverend Shuttlesworth, it is clear that he was

an officer of SCLC, its secretary, at the time of the demon

strations. However, not only is there no evidence that he

was acting in that capacity with regard to the demonstra

tions, but the testimony of plaintiff’s witness, as set out in

the statements of facts, supra, was to the contrary. Rev.

Shuttlesworth was a minister in Birmingham and as such

was active in the affairs of the city, particularly as they

related to equal civil rights. A police officer, testified that

he heard Shuttlesworth speak at a church on February 21

regarding Liberty Supermarket. The police officer testified

directly that Shuttlesworth spoke not with relation to SCLC

or in his capacity as an officer thereof, but “as an individ

ual” (S.A. 135).

Reverend Lowery was on the board of directors of SCLC

in February, 1966, and was chairman of the board at the

time of the trial here. Again, he is a local minister and is

a member of local organizations active in civil rights activi

ties. He testified positively that at no time did he partici

pate in the demonstrations as a representative or agent of

SCLC. His actions were as a private individual and in con

junction with other local ministers. No evidence was intro

duced showing that he had any authority to act on behalf

of SCLC or that he at any time held himself out as doing so.

Hosea Williams and the two or three other SCLC em

ployees may be dealt with together, since the latter were

apparently sent to work with him on voter registration in

Birmingham. Mr. Williams is an employee of the corpora

tion, with the title of director, voter registration (PL Ex. 1,

p. 12). Defendant-appellant does not deny either that W il

liams is an employee of SCLC or that he, as an individual,

19

participated in some degree and at some time in the Liberty

Supermarket demonstrations. However, the cases cited

above make it clear that that is not enough to establish

liability on the corporation’s part. We do deny that he so

participated on behalf of the corporation or that he was

authorized to do so. His acts were done as an individual

and not in furtherance of his employer’s affairs or within

the scope of his employment.

Indeed, there was only one item of testimony that pur

ported to connect Williams’ participation in the demon

strations with SCLC. Mr. Jim Cunningham, a local tele

vision reporter, testified that he had spoken to Williams

sometime during this general period, although he could not

say whether it was before or after the shooting. He said

that Williams told him that “they” had been picketing at

Liberty, and that:

There had been a group picketing there who Hosea

indicated to us, or told me that they had some involve

ment with, in other words, he said it was S.C.L.C.

(S.A. 250).

This vague statement, however, is not enough to estab

lish, as a matter of law, that Williams was acting within

the scope of the authority given him by SCLC. As a gen

eral rule, of course, an agent’s out-of-court declarations

are not competent against the principal to show scope of

authority unless there is other evidence to show that the

statement itself was within the authority of the agent to

make. Wade v. Brisker, 233 Ala. 585, 173 So. 64. Although

this rule has been relaxed somewhat in Alabama, it has been

relaxed in cases where other evidence has shown the general

scope of the agent’s authority, particularly where ques

tions of contractual liability and ostensible authority wTere

involved. See, e.g., Wilson <& Co. v. Clark, 67 So.2d 898

20

(1953). Here, of course, all the direct evidence as to the

scope of Williams’ authority as given by SCLC clearly

establishes that he was sent to Birmingham to act in his

capacity as director of voter registration. In the face of

this clear evidence, the vague recollection that Williams

“ indicated” that “they” had “ some involvement with” the

demonstrations is simply insufficient as a matter of law to

carry plaintiff’ s burden of proof that an employee or agent

of the corporation was acting on its behalf and under au

thority given by it so as to establish responsibility for the

demonstrations on the part of SCLC.

One or two other items should also be mentioned. Plain

tiff introduced as Exhibit 5 a button bearing the words

“Southern Christian Leadership Conference” with clasped

hands, which was said to be representative of buttons some

demonstrators were wearing. The testimony of Reverena

Lowery, however, made it clear that these buttons had been

distributed at public meetings over a long period of time.

The wearing of them did not indicate employment, agency,

or any connection with SCLC, but only that the wearer

subscribed to its principles of achieving racial justice

through non-violent means. Finally, it was testified at first

that a copy of the February 18 release with Hosea W il

liams’ name, together with those of four others, was picked

up at an “ SCLC office.” The same witness subsequently

testified, however, that a number of organizations, includ

ing local ones, used the facilities of the office, particularly

to reproduce statements. Thus, it could not be said that

the statement was put out by SCLC (S.A. 251-252).

To summarize this part of the argument, the overwhelm

ing thrust of the testimony at trial was that the demon

strations at Liberty Supermarket arose out of incidents

that affected the local Black community; in response, local

21

ministers, acting as such and as representatives of local

organizations, decided to demonstrate at the store; the min

isters urged people to participate, and organized, led, and

directed the demonstrations. At the time, SCLC had in

Birmingham persons whose job was voter registration and

who had been sent there for that specific purpose. Indi

viduals, who were such SCLC employees, decided, as indi

viduals, to participate in the locally organized and run

demonstrations. They were not authorized to do so in the

name or on behalf of SCLC, and there is no legally suffi

cient evidence that they did so. The only connecting link

of any sort was an unauthorized, out-of-court, vague state

ment by one employee.

Thus, the court below was in error in refusing to direct

a verdict for the defendant corporation or to render a judg

ment notwithstanding the verdict. See, McPherson v. Tami-

ami Trail Tours, Inc., 383 F.2d 527 (5th Cir. 1967). And

in light of the direct and positive evidence against any

authority on the one hand, and the vague and ambiguous

piece of testimony on the other, the trial court was also in

error in refusing to grant a new trial. Although the denial

of a new trial is not generally reviewable on appeal, it is

reviewable where there has been an abuse of discretion.

Here there was such an abuse. As has been shown, not only

was there little or no evidence showing agency, but the

overwhelming weight of the evidence was against such a

finding Cf., Whiteman v. Pitrie, 220 F.2d 914, 919 (5th

Cir. 1955).

22

II.

The Evidence Was Insufficient in Law and Fact to

Establish Liability for Plaintiff’ s Injuries Because of

the Acts of SCLC Employees Either for Negligence or

for the Establishment o f a Nuisance.

For the purpose of this argument, it will he assumed

that the employees of SCLC, viz., Hosea Williams and

those working under him, were given authority to partici

pate to some extent on the corporation’s behalf in the

Liberty Supermarket demonstrations.6 However, even un

der that assumption, liability on the part of SCLC for the

injuries sustained by plaintiff was not established by the

evidence.

It is established law, in Alabama as in other jurisdic

tions, that in order for a plaintiff to recover either for

negligence or for nuisance, he must establish that his in

juries have occurred as a result of acts of the defendant

which it should have reasonably foreseen would have re

sulted in the injuries. There must be shown to have been

an unbroken chain of causation from the acts to the injury.

See, e.g., Sullivan v. Alabama Power Co., 246 Ala. 262, 20

So.2d 224 (1945); Morgan v. City of Tuscaloosa, 268 Ala.

493, 108 So.2d 342 (1959).

The evidence here falls far short of this standard. It

must be kept in mind precisely what it was that SCLC’s

employees were shown to have done. First, Williams, to

gether with others, issued a statement on February 18

stating that the Negro community would withdraw patron

6 No such assumption is made as far as the local ministers are

concerned, however. The evidence, as shown above, is uncontra

dicted as to the basis for their actions, viz., that they were acting

as individuals and in conjunction with local organizations.

23

age from the store as a result of certain incidents until

the store adopted certain policies (PI. Ex. 26). Second, he

spoke at a church meeting that evening urging people there

to follow him the next day, February 19, to take part in

a picket line. And third, at some unspecified dates he, with

other persons who were also SCLC staff employees, took

part in picketing.

There was no evidence that he or any other SCLC work

ers were at Liberty Supermarket on February 22 or took

part in, led, or directed the picketing then.6 Reverend

Gardner, a local minister acting independently of SCLC,

testified that he was in charge of the demonstrators on

February 22 and that they were under instructions to be

peaceful and non-violent at all times (S.A. 274-275). A

demonstrator, who was one of those shot, testified that he

was there because his pastor and other local preachers

had been picketing and had asked for help (S.A. 299).

After picketing had been going on for some time on that

evening, on the sidewalk and apparently peacefully and

without incident, a number of things occurred. A group

of marchers came through the parking lot. A car, driven

by a white customer drove through the line of march, racing

its engine and forcing some persons to jump aside. It

went out of the exit and stopped, blocking the sidewalk

while waiting for the street traffic to clear. A group of

picketers, on their way to a prayer service came up to the

car, as did some of those from the group of marchers.

There was testimony that some people in the group began

to rock the car, in direct contradiction to the instructions

they had been given by Reverend Gardner. The driver

6 There was testimony that two SCLC employees were seen on the

premises after the shooting as part of a “ large crowd” of persons

from the community that “congregated moments after the shoot

ing” (S.A. 244).

24

fired five shots into the crowd, paused, then fired three or

four more times. Plaintiff, who had been sitting in his car

watching the demonstrators and the entire series of events

for five or ten minutes, got out after the first volley of

shots, evidently to better see what had happened. As a

result, he was hit by one of the second series of bullets.

Thus, in this case there was only the most tenuous and

speculative chain of causation between the defendant

and the actual act that caused injury to the plaintiff.

There was no evidence that SCLC had any respon

sibility for or connection with the February 22 demon

strations at all or indeed that it had acted negligently

at any time. Local people were involved in the planning

and leading of demonstrations throughout this period,

and the evidence is clear that they organized and led

the one on the date in question. SCLC’s participation,

assuming again that there was any, generally was limited

to one of its employees calling for people to take

part in a demonstration three days earlier and his dem

onstrating himself at some earlier unspecified date. Thus,

S.C.L.C. could not be held responsible for any nuisance,

if there was any, created on February 22.

Moreover, the persons who led the February 22 demon

strations had issued orders for the participants to be

peaceful and nonviolent. Apparently, these orders were

being carried out when the automobile pushed its way

through a group of demonstrators, thus touching off the

series of events that culminated in shots being fired. Cer

tainly it is stretching the chain of causation far past its

breaking point to hold SCLC responsible, in light of what

it was actually shown to have done, for the driver’s initial

conduct, the response of one group of marchers in viola

tion of specific instructions to it, the unforeseeable over

25

response of the driver in firing into the crowd, and the

actions of plaintiff in deliberately removing himself from

his car, a place of safety, and, out of curiosity about the

first volley, placing himself in a position where he was

in direct danger of being shot.

Again, the principles of law that must govern are clear.

A remote cause of an injury, where there are independent

intervening causes is not actionable. See Morgan v. City

of Tuscaloosa, 268 Ala. 493, 108 So.2d 342 (1959). More

over, when the plaintiff voluntarily placed himself in a

position that he should have foreseen to be dangerous as

a reasonable man, he assumed the risk inherent in the

situation and he may not recover, at least not from SCLC.7

See Foster & Creighton Co. v. St. Paul Mercury Indemnity

Co., 264 Ala. 581, 88 So.2d 825 (1956); Walker County v.

Davis, 221 Ala. 195, 128 So. 144 (1930).

In sum, there simply was no evidence showing a con

tinuing unbroken sequence of events from acts of SCLC

to plaintiff’s injuries. The chain is too tenuous to allow

recovery under any standard of law and it was error to

allow the matter to go to the jury, not to enter a judg

ment notwithstanding the verdict, and not to have granted

a new trial (see eases cited supra). Similarly, there was a

total lack of evidence showing responsibility for the crea

tion of a nuisance on the date in question or at any other

time.

Reverend Lowery, testifying as a member of the board

of SCLC, stated flatly that Williams was sent to Birming

ham to act in the capacity in which he was employed by

SCLC, viz., director of voter registration. He, and those

working under him, were to conduct a voter registration

7 Of course plaintiff’s acts would not have absolved from liability

the person who deliberately fired the shots that injured him.

26

drive in Birmingham, which they did in late 1965 and 1966

(see, Plaintiff’s Ex. 16). This, according to Lowery, was

all that Williams was authorized to do on behalf of SCLC,

and further, this was all he did do as an employee of the

corporation.

Again, it is not denied that Williams took part in the

Liberty Supermarket demonstrations, working with the

local ministers and individuals in the Black community.

His participation, as shown by the evidence, consisted in

urging persons to go down to the store and demonstrate

at a church meeting on February 18, in issuing a statement

together with four local ministers, also on February 18,

and in actually taking part in one or two demonstrations

on some unspecified dates. In his speech on the 18th he

called for persons to go down with him on the next day,

February 19, although there was no direct evidence plac

ing him at the scene on that day. It is clear, however,

that he was not at the store on the night of the shooting,

i.e., February 22.

The police officer who testified concerning the February

18 speech stated that his notes mentioned SCLC only in

connection with the voter registration drive and not with

regard to Liberty Supermarket (S.A. 120-123). Similarly,

the statement issued on February 18 made no mention of

SCLC and did not indicate any affiliation by Mr. Williams’

name. Indeed, a local minister, Rev. N. IT. Smith, who

was not shown to have any connection with defendant,

was designated chairman of what was evidently an ad hoc

group (PL Ex. 26).

27

III.

The Evidence Was Insufficient to Support the Amount

of Damages Awarded.

The jury rendered a verdict in the amount of $45,000.

Defendant-appellant moved that the amount be set aside

and a new trial awarded on the question of damages in

that actual damages were proven only in the amount of

$4,107.00 (S.A. 81-82). Subsequently, the Court ordered a

remittor in the amount of the hospital expenses, i.e., $3057,

on the grounds that a veteran was not entitled to recover

the value of hospital care provided free by the government

(S.A. 84-85). The resulting judgment in the amount of

$41,943 was then affirmed despite the motion for a new

trial.

Although a denial of a motion for a new trial on the

ground that the damages awarded were excessive is not

ordinarily reviewable, this Court has ordered a new trial

when there appeared to be no basis in the evidence for

the amount. Thus, in Whiteman v. Pitrie, 220 F.2d 914 (5th

Cir. 1955), a judgment in the amount of $30,000 was held

excessive and a new trial ordered.

The facts in Whiteman were similar to those in this

case. There, no substantial loss in future earnings was

shown, since the plaintiff was employed at a higher paying

job than before the accident. Here, plaintiff testified that

at the time of the shooting he was averaging between $75

and $80 per week. At the time of trial he was making

about $106 per week and had been for two months. He

was not able to work from late February 1966 until around

the first week of June, 1966, or for about sixteen weeks.

At $75 per week his loss of earnings would be about $1200.

28

In Whiteman, there was no loss of earnings since the

plaintiff’s employer continued to pay him wages.

In Whiteman, the plaintiff suffered substantial perma

nent loss of the use of one arm. Here, there was little

evidence of any permanent loss or damage. Plaintiff still

had a drainage tube in him, but his doctor testified that

it could not be said to be a permanent condition (S.A.

224). Plaintiff was still able to do his work as a truck

driver which included handling heavy articles. He testified

that his injury bothered him at times at night. There was

no evidence as to permanent dimunition of earning power,

or shortening of either his work or physical life.

Despite the showing of actual damages only in the

amount of $1200, the Court upheld an award of more than

$41,000. Although some of this might be accounted for

as compensation for pain and suffering, in light of the

failure to show permanent injury or any impairment of

earning capacity, the judgment must be viewed, as was

the one in Whiteman, to be the product of sympathy or

bias on the part of the jury or to be in the nature of

punitive damages. As this Court made clear there, these

are not the proper bases for the assessment of damages

and defendant-appellant is entitled to a new trial on that

issue.

29

IV.

The Granting of Damages Against SCLC Here Con

stituted an Abridgement of Rights of Free Speech and

Assembly Protected by the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments.

As shown in Part II, supra, the verdict of the jury below

cannot stand in the face of accepted and standard prin

ciples of tort liability. When viewed in light of constitu

tional requirements, the judgment of the court below must

certainly be reversed. Defendant-Appellant claimed as a

defense that during the time in question here its actions

were protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments’

guarantees of freedom of association, assembly and speech.

These points were argued to the trial court as a matter of

law in defendant’s motions for directed verdict, judgment

notwithstanding the verdict, or for a new trial.

It is clear under decisions by the United States Supreme

Court that constitutional guarantees cannot be abridged by

judgments of courts rendered in lawsuits by private liti

gants. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948); New York

Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964). It is also clear that

when nonfrivolous constitutional claims are asserted it is

the duty of the court to make an independent examination

of the record to resolve the issue. This is particularly the

case when First Amendment claims are asserted.

Here, the claim is that to the extent that SCLC was in

volved at all in the Liberty Supermarket demonstrations8

its actions were fully within the bounds of freedom of

association, assembly, and speech. Again, as in Part II, it

8 Again, this argument assumes, solely for the sake of argument,

that there was sufficient evidence to support a finding that SCLC,

as a corporation, was involved.

30

is important to note what the evidence did and did not show.

SCLC did not fire the shots that wounded plaintiff; it did

not cause plaintiff to get out of his car and put himself in

danger; it did not rock the assailant’s car; and it did not

drive the car through the line of marchers. Indeed, there

is no evidence that SCLC or any of its agents or repre

sentatives was on the scene prior to the shooting, or that

they took part in, led, organized, or directed the demon

strators on that evening. The evidence was that the organ

izing and leadership was carried out by persons acting

independently of SCLC, and they had instructed the dem

onstrators to conduct themselves at all times peacefully

and nonviolently.

All the evidence showed that SCLC did, through its

agents, was to state that Negroes would stop patronizing

the store until conditions there were corrected, to ask for

volunteers to demonstrate on a particular day, and to take

part in other demonstrations on one or two occasions. There

was no evidence that any of the demonstrations participated

in by SCLC people were other than peaceful and orderly.

There was no evidence that the defendant ever urged any

thing but peaceful demonstrations and picketing or that it

participated in, sponsored, or condoned any unlawful acts

whatsoever.

Thus, this case presents squarely an issue crucial to the

continued vitality of fundamental constitutional rights:

Whether an organization can be subjected to crippling judg

ments on no evidence of any wrongdoing on its part because

of injuries at best remotely stemming from its efforts to

bring about racial justice? In this connection, this case

may be contrasted with that of NAACP v. Overstreet, 221

Ga. 16, 142 S.E.2d. 816 (1965), cert. dism. as improvidewtly

granted, 384 U.S. 118 (1966). There, a branch of the

N.A.A.C.P. organized and carried out a boycott against a

31

store in Savannah., Georgia, on the grounds that the owner

had assaulted a Negro boy who had worked for him. The

owner sought, and was awarded, damages for the loss of

business and goodwill he suffered as a result of the boycott

and demonstrations. The Supreme Court of Georgia af

firmed on a number of bases, among them a finding that

there was in fact no valid racial dispute and that therefore

no legitimate basis for the boycott existed. Over a strong

dissent, the Supreme Court dismissed the writ of certiorari,

which had been limited to the sole question of whether the

national N.A.A.C.P. could be held liable for acts of one of

its branches.

In that case, the action was brought by the store owner

himself to seek compensation for the damages intended by

the demonstrators, the loss of his business. Moreover, the

suit was against those who had in fact conducted the dem

onstrations. Violence was found to have been inflicted by

the demonstrators themselves on the store owner and his

customers—those against whom the demonstrations were

aimed. Both the local N.A.A.C.P. and the national office

were served with the papers in the suit attempting to halt

the demonstrations, and the latter did not attempt to dis

avow the local branch.

In Overstreet, in other -words, damages were sought to

rectify the intended effects of the demonstrations. The

demonstrations themselves were found to have no valid

basis and to have been illegally conducted. Here, SCLC’s

participation, if indeed there was any, was of an entirely

different character. At no time was it shown to have urged

or to be responsible for any illegal or violent acts; on the

contrary, those in charge of the demonstrations had in

structed that they be peaceful and nonviolent. In Over-

street, the damages were precisely those intended and

brought about, and encouraged, by the demonstrators; here,

32

the injury to plaintiff was fortuitous, unintended and un

foreseeable by those seeking to rectify the situation at

Liberty, and wholly unrelated to their aims and intentions.

In his dissent to the dismissal of certiorari in Overstreet

Mr. Justice Douglas, joined by three other members of the

Court, warned of the paralyzing effect of an award of

damages under the circumstances there. Here, the result of

Overstreet, which barely failed to be overturned, has been

stretched far beyond even its dubious limits. If the judg

ment below is affirmed, an organization active in the crucial

area of civil rights may be subjected to liability on a show

ing of nothing more than that it was carrying out a program

of voter registration in an Alabama city; some of its em

ployees participated in unrelated demonstrations carried

out by members of the local community; the employees did

no more than urge people to join them in demonstrations

on specific dates; on an occasion when no such employees

or agents were present or in charge some demonstrators

became involved in an incident unrelated to the purposes

of the demonstrations; a person, not a demonstrator and

obviously unsympathetic to their cause, fired into the crowd

injuring a bystander. To impose liability under these cir

cumstances would go far in undermining the right of asso

ciation so vital to a free society.

In summarizing defendant-appellant’s argument, it must

be emphasized that we do not argue that the plaintiff should

not have been recompensed for his injuries. Again, how

ever, his relief lay not against SOLO but against the one

that fired the shots. To hold otherwise would not only fly

in the face of the law and the evidence, as it pertains to

traditional principles of agency and corporate liability for

tort, but would seriously and adversely affect the activities

of those who are attempting to achieve racial equality

through associating and acting within constitutional limits.

33

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the judgment below must be

reversed with instructions either to enter a judgment on

behalf of the defendant-appellant, or to grant a new trial.

Respectfully submitted,

Chables S teph en R alston-

1095 Market Street

San Francisco, California 94103

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. R abbit, III

N orman C. A m akeb

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

P eter A. H all

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Defendants-Appellants

34

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that I have served a copy of the attached

Brief for Defendants-Appellants on counsel for the plain

tiff-appellee, Mr. Jerry 0. Lorant, 1010-1016 Frank Nelson

Building, Birmingham, Alabama 3520J by IJnited States

mail, postage prepaid, on this the -- day of De

cember, 1968.

Attorney for Defendants-Appellants

MEiLEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. «€11P»219