Corrigan v. Buckley Appellants' Points

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1925

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Corrigan v. Buckley Appellants' Points, 1925. c9daa372-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e13f7b52-26d8-4b46-99a5-7a5f3313a7a5/corrigan-v-buckley-appellants-points. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

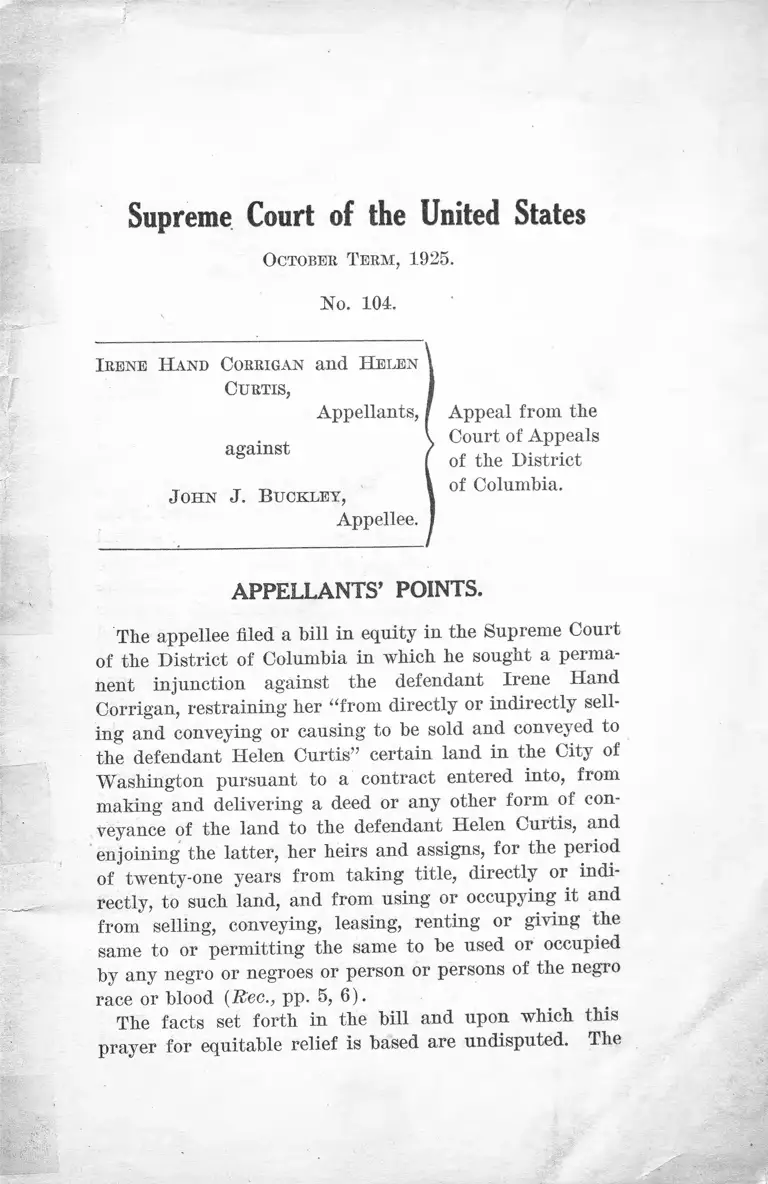

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1925.

No. 104.

Irene Hand Corrigan and Helen

Curtis,

Appellants,

against

John J. Buckley,

Appellee.

APPELLANTS’ POINTS.

The appellee filed a bill in equity in the Supreme Court

of the District of Columbia in which he sought a perma

nent injunction against the defendant Irene Hand

Corrigan, restraining her “ from directly or indirectly sell

ing and conveying or causing to be sold and conveyed to

the defendant Helen Curtis” certain land in the City of

Washington pursuant to a contract entered into, from

making and delivering a deed or any other form of con

veyance of the land to the defendant Helen Curtis, and

enjoining the latter, her heirs and assigns, for the period

of twenty-one years from taking title, directly or indi

rectly, to such land, and from using or occupying it and

from selling, conveying, leasing, renting or giving the

same to or permitting the same to be used or occupied

by any negro or negroes or person or persons of the negro

race or blood (Bee., pp. 5, 6).

The facts set forth in the bill and upon which this

prayer for equitable relief is based are undisputed. I he

Appeal from the

Court of Appeals

of the District

of Columbia.

2

appellee is tlie owner of premises known as 1719 S Street,

N. W., Washington. The appellant Irene Hand Corrigan

was the owner of premises known as 1727 S Street, N. W.,

Washington. On June 1, 1921, Buckley, Mrs. Corrigan

and twenty-eight other persons, all of whom at the time

owned twenty-three other parcels of land improved by

dwelling houses adjacent and contiguous to and in the

same immediate neighborhood as the lands of the appellee

and Mrs. Corrigan and severally situated on both the

north and south sides of S Street between New Hampshire

Avenue and 18th Street, N. W., in the City of Washington,

entered into a covenant which is set forth in the Record

at pages 6-9.

This instrument, after reciting that the parties who

executed it are tlie oivners of real estate located in the

District described and that they “desire, for their mutual

benefit, as well as for the best interests of the said com

munity and neighborhood, to improve—in any legitimate

way further the interests of said community,” provides

that the parties thereto mutually covenant, promise and

agree with each other and for their respective heirs and

assigns “that no part of the land now owned by the parties

hereto, a more detailed description of said property being

given after the respective signatures hereto, shall ever be

used or occupied by or sold, conveyed, leased, rented, or

given, to Negroes or any person or persons of the Negro

race or blood. This covenant shall run with the land and

bind the respective heirs and assigns of the parties here

to for the period of twenty-one (21) years from and after

the date of these presents.”

All the persons who executed this covenant are white

persons, a large number of whom occupied, resided in and

made their homes, and continued to occupy, reside and

make their homes in the premises described (Rec., p. 2).

On September 26, 1922, Mrs. Corrigan entered into a

sales contract with Mrs. Curtis, by which the latter agreed

to purchase from Mrs. Corrigan and she agreed to sell

3

and convey to Mrs. Curtis the premises 1727 S Street,

Northwest, which instrument was duly recorded in the

office of the Recorder of Deeds of the District of Colum

bia (B e e pp. 3, 9, 10). Mrs. Curtis is a person of the

Negro race and blood.

A number of parties to the covenant thereupon “ objected

and protested to the defendant Corrigan against the ex

ecution or carrying out by her of the terms and provisions

of said contract of sale,” but on November 8, 1922, she

definitely stated “that she would not fight the said con

tract of sale, that is to say, would not refuse to execute

and carry out the terms and conditions thereof, nor would

she refuse to sell and convey to the defendant Curtis the

land and premises involved as aforesaid, nor would she

refuse to make, sign, seal and deliver a deed to the same

to said defendant last named, * * * and now is threat

ening to execute and carry out and is about to execute

and carry out the terms and provisions of the aforesaid

contract of sale and in pursuance thereof to sell and con

vey to the defendant Curtis the land and premises in

volved as aforesaid and to make, sign, seal and deliver

a deed to the same to said defendant Curtis” (Bee., pp.

4 , 5 ).

After setting forth these facts, the bill of complaint

alleges (Bee., p. 5) :

“ 14. That if the threats aforesaid are fulfilled and

carried out and the defendant sells and conveys to

the defendant Curtis the said land and premises and

makes, signs, seals and delivers a deed to the same to

said defendant Curtis, irreparable injury will be done

to the plaintiff and to the other persons who are

parties to the aforesaid indenture or covenant and

that plaintiff has no plain, adequate or complete

remedy at law; and plaintiff further avers that he is

entitled to specific performance on the part of the

defendant Corrigan of her said agreements and cove-

4

mints as set out in the said Indenture or Covenant

mentioned and described in paragraph 6 of this bill

and to have the terms and provisions of said Indenture

or Covenant specifically enforced in equity by means

of an injunction preventing both the said defendants

Corrigan and Curtis from carrying into effect the said

contract of sale mentioned and described in paragraph

7 of this bill.’ '

Mrs. Curtis moved to dismiss the bill of complaint on

the grounds that the alleged indenture or covenant was

void, in that it attempts to deprive her and others of

property without due process of law ; abridges the privi

leges and immunities of citizens of the United States, and

other persons within this jurisdiction, of the equal pro

tection of the law, and is forbidden by the Fifth, Thir

teenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of

the United States and the laws enacted in aid and under

the sanction of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amend

ments {Bee., p. 11).

As appears from the opinion of the Supreme Court of

the District of Columbia “the defendant urges very

strongly in her brief that such a restriction is against

public policy and the point is perhaps one that should be

considered” {Bee., p. 14). The Court thereupon discussed

at length this point and passed upon it, and decided it

adversely to the contention of Mrs. Curtis.

Mrs. Corrigan also moved to dismiss the complaint on

the ground that the alleged indenture is void, that it is

contrary to and in violation of the Constitution of the

United States, and that it “ is void in that the same is

contrary to public policy” {Bee., p. 17).

Both of these motions were overruled and both of the

parties electing to stand on their motions to dismiss the

Court permanently enjoined both of them in conformity

with the prayer of the bill of complaint {Bee., pp. 17-19).

An appeal was thereupon taken by both defendants to

5

the Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia, where

error was assigned not only on the ground of the con

stitutional questions above stated, but also that the Court

erred in holding that the covenant set out in the bill

was not void as against public policy and in not holding

to the contrary (Bee., p. 19). The Court of Appeals af

firmed the decree of the Supreme Court (B e e p. 25), and

thereafter an appeal to this Court was allowed (R e c pp.

25-27).

Assignments of Error.

Among the Assignments of Error are the following

(Rec., p. 26) :

“3. The Court erred in holding that the indenture

or covenant set out in appellee’s bill of complaint

is not void as against public policy.”

“4. The Court erred in holding to the contrary.”

“5. The Court erred in not holding that the said

indenture or covenant is void in that it deprives the

defendants, appellants, and others, of property with

out due process of law.”

“ 6. The Court erred in holding to the contrary.”

“ 7. The Court erred in not holding that the said

indenture or covenant is void in that it abridged the

privileges and immunities of citizens of the United

States, including the defendants, appellants, Irene

Hand Corrigan and Helen Curtis, and other persons

within this jurisdiction.”

“8. The Court erred in holding to the contrary.”

“9. The Court erred in not holding that the said

indenture or covenant is void in that it denied to

the said defendants, the said Irene Hand Corrigan

and Helen Curtis, and other persons within this juris

diction, the equal protection of the law.”

“10. The Court erred in holding to the contrary.”

6

“11. The Court erred in not holding that the said

indenture or covenant is void in that it is forbidden

by the Constitution of the United States and espe

cially by the Fifth, Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amend

ments thereof, and the laws enacted in aid and under

the sanction of the said Fifth, Thirteenth and Four

teenth Amendments.”

“ 12. The Court erred in holding to the contrary.”

POINTS,

I.

The decrees of the Courts below constitute a viola-

tion of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the

Constitution, in that they deprive the appellants of their

liberty and property without due process of law.

This proposition is the legitimate and logical conse

quence of the unanimous decision rendered by this Court in

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S., 60. There it was at

tempted, by legislation in the form of a city ordinance,

to forbid colored persons from occupying houses as resi

dences, or places of abode, or public assembly, on blocks

where the majority of the houses were occupied by white

persons for those purposes, and in like, manner forbidding

white persons when the conditions as to occupancy were

reversed, and which based the interdiction upon color and

nothing more.

Here the decrees of the Supreme Court and the Court

of Appeals of the District of Columbia have forbidden

Mrs. Corrigan, a white person, from selling to Mrs.

Curtis, a colored person, and Mrs. Curtis from buying, a

house in the residential district of Washington, solely

because Mrs. Curtis is of Negro race or blood, and for

bidding Mrs. Curtis, her heirs and assigns, for a period of

twenty-one years, from taking title to this property, from

7

using or occupying it, and from selling, conveying, leasing,

renting or giving it* to or permitting it to be used or oe-

cuped by any Negro or Negroes or persons of the Negro

race or blood.

The question that was to be determined in Buchanan v.

Worley was thus stated by Mr. Justice Day (p. 75) :

“ The concrete question here is : May the occu

pancy, and, necessarily, the purchase and sale of prop

erty of which occupancy is an incident, be inhibited

by the State, or by one of its municipalities, solely

because of the color of the proposed occupant of the

premises ?”

In the course of the discussion of this proposition, it

was said:

“Property is more than the mere thing which a

person owns. It is elementary that it includes the

right to acquire, use, and dispose of it. The Con

stitution protects these essential attributes of prop

erty. Holden v. Hardy, 169 U. S., 366, 391. Prop

erty consists of the free use, enjoyment, and disposal

of a person’s acquisitions without control or diminu

tion save by the law of the land. 1 Blackstone’s Com

mentaries (Cooley’s Ed.), 127.”

The opinion then considers the history of the Thirteenth

and Fourteenth Amendments, quoting from the Slaughter

House Cases, 16 Wall., 36; Stra-uder v. West Virginia, 100

U. S., 303, and Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S., 339, 347.

A part of the quotation from Strauder v. West Virginia

consisted of these passages (p. 77) :

“What is this (the Fourteenth Amendment) but

declaring that the law in the States shall be the same

for the black as for the white; that all persons,

whether colored or white, shall stand equal before the

8

laws of the States, and, in regard to the colored race,

for whose protection the amendment was primarily

designed, that no discrimination shall he made against

them by law because of their color? * * * The Four

teenth Amendment makes no attempt to enumerate

the rights its designed to protect. It speaks in gen

eral terms, and those are as comprehensive as pos

sible. Its language is prohibitory; but every prohi

bition implies the existence of rights and immunities,

prominent among which is an immunity from in

equality of legal protection, either for life, liberty, or

property. Any State action that denies this immunity

to a colored man is in conflict with the Constitution.”

The quotation from Ex parte Virginia, supra, is espe

cially important:

“Whoever, by virtue of public position under a

State government, deprives another of property, life,

or liberty, without due process of law, or denies or

takes away the equal protection of the laws, violates

the constitutional inhibition; and as he acts in the

name and for the State, and is clothed with the State’s

power, his act is that of the State.”

It is proper to pause at this point to refer to the de

cision in Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S., 313, rendered con

currently with Ex parte Virginia, where Mr. Justice

Strong said:

“ It is doubtless true that a State may act through

different agencies,—either by its legislative, its ex

ecutive, or its judicial authorities; and the prohibi

tions of the amendment extend to all action of the

State denying equal protection of the laws, whether

it be action by one of these agencies or by another.

Congress, by virtue of the fifth section of the Four

teenth Amendment, may enforce the prohibitions

9

whenever they are disregarded by either the Legisla

tive, the Executive, or the Judicial Department of

the State.”

We add a further quotation from the opinion in Ex

parte Virginia (pp. 346, 347) :

“We have said the prohibitions of the Fourteenth

Amendment are addressed to the States. * * * They

have reference to actions of the political body de

nominated a State, by whatever instruments or in

whatever modes that action may be taken. A state

acts by its legislative, its executive or its judicial

authorities. It can act in no other way.”

In United States v. Harris, 106 U. S., 629, 639, this

Court said:

“When the State has been guilty of no violation of

its provisions; when it has not made or enforced any

law abridging the privileges or immunities of citizens

of the United States; when no one of its departments

has deprived any person of life, liberty, or property

. without due process of law, or denied to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection, of the

laws; when, on the contrary, the laws of the State,

as engcted by its legislative, and construed by its

judicial, and administered by its executive depart

ments, recognize and protect the rights of all persons,

the amendment imposes no duty and confers no power

upon Congress.”

So in Scott v. MoNeal, 154 U. S., 34, it was held that

the prohibitions of the Amendment extended to “all acts

of the State, whether through its legislative, its executive,

or its judicial authorities.”

And in Chicago, Burlington & Quincy R. R. Co. v.

Chicago, 166 U. S., 226, 233, Mr. Justice Harlan, said:

10

“ But it must be observed that tbe prohibitions of

the amendment refer to all the instrumentalities of

the State, to its legislative, executive and judicial

authorities, and, therefore, whoever by virtue of

public position under a State government deprives

another of any right protected by that amendment

against deprivation by the State, violates the con

stitutional inhibition; and as he acts in the name and

for the State, and is clothed with the State’s power,

his act is that of the State.”

Further Mr. Justice Harlan says (pp. 234, 235) :

“But a State may not, by any of its agencies, dis

regard the prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Its judicial authorities may keep within the

letter of the statute prescribing forms of procedure

in the courts and give the parties interested the full

est opportunity to be heard, and yet it might be that

its final action would be inconsistent with that amend

ment. In determining what is due process of law re

gard must be had to substance, not to form.”

See also Home Telephone & Telegraph Co. v. Los

Angeles, 227 U. S., 278, where it was again declared that

these provisions of the Constitution are generic in terms

and are addressed not only to the States, but to every per

son, whether natural or judicial, who is the repository of

State power, and that their reach is co-extensive with any

exercise by a State of power in whatever form asserted.

The same effect has been given to the due process clause

of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution. Seventy

years ago, in Murray’s Lessee v. Hoboken Land & Im

provement Co., 18 How., 276, Mr. Justice Curtis said:

“ It is manifest that it was not left to the legisla

tive power to enact any process which might be de

vised. The article is a restraint on the legislative

11

as well as on the executive and judicial powers of

the Government

In Hovey v. Elliott, 167 U. S., 409, this Court was

called upon to determine the effect of an order rendered

by the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia at

General Term in a contempt proceeding, which decreed

that the defendants’ answer be stricken out and removed

from the files of the court because of non-compliance on

their part with the requirements of a decree previously

rendered by the court, and that the cause should then

proceed as if no answer had been interposed. It w~as

held that the action of the court was a violation of the

Fifth Amendment. Mr. Justice White, in the course of

his comprehensive opinion, said:

“ To say that courts have inherent power to deny all

right to defend an action and to render decrees with

out any hearing whatever is, in the very nature of

things, to convert the court exercising such an au

thority into an instrument of wrong and oppression,

and hence to strip it of'that attribute of justice upon

which the exercise of judicial power necessarily de

pends” (p. 414).

Again, on page 417, he said, in words which could be

well applied here:

“ If the legislative department of the government

were to enact a statute conferring the right to con

demn the citizen without any opportunity whatever

of being heard, would it be pretended that such an

enactment would not be violative of the Constitution?

If this be irue, as it undoubtedly is, how can it be

said that the judicial department, the source and foun

tain of justice itself, has yet the authority to render

lawful that which if done under express legislative

12

sanction would be violative of the Constitution? If

such power obtains, then the judicial department of

the government sitting to uphold and enforce the

Constitution is the only one possessing a power to

disregard it. I f such authority exists then in conse ̂

quence of their establishment, to compel obedience to

lam and to enforce justice courts possess the right

to inflict the very wrongs which they were created to

prevent

Beturning to the opinion in Buchanan v. Warley, sup

plemented by these utterances, which include in the con

stitutional inhibition not merely executive and legislative

invasions of the right sought to be protected, but also

those of the judicial arm of the Government, we find that,

in giving legislative aid to these constitutional provisions,

Congress made two statutory declarations, which consti

tute Sections 1977 and 1978 of the United States Bevised

Statutes. The first of these reads:

“All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal bene

fit of all laws and proceedings for the security of per

sons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and

shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties,

taxes, licenses and exactions of every kind, and no

other.”

Section 1978 declares:

“All citizens of the United States shall have the

same right in every State and Territory as is enjoyed

by white citizens thereof to inherit, purchase, lease,

sell, hold and convey real and personal property.”

After referring to the authorities and statutes cited by

13

Mm, Mr. Justice Day very appropriately asked : “ In the

face of these constitutional and statutory provisions, can

a white man be denied, consistently with due process of

law, the right to dispose of his property to a purchaser by

prohibiting the occupation of it for the sole reason that the

purchaser is a person of color intending to occupy the

premises as a place of residence?” He answered (p. 78) :

“ The statute of 1866, originally passed under sanc

tion of the Thirteenth Amendment, 14 Stat., 27, and

practically reenacted after the adoption of the Four

teenth Amendment, 16 Stat., 144, expressly provided

that all citizens of the United States in any State

shall have the same right to purchase property as is

enjoyed by white citizens. Colored persons are citi

zens of the United States and have the right to pur

chase property and enjoy and use the same without

laws discriminating against them solely on account of

color. Hall v. DeCuvr, 95 U. S., 485, 508. These en

actments did not deal with the social rights of men,

but with those fundamental rights in property which

it was intended to secure upon the same terms to

citizens of every race and color. Civil Rights Cases,

109 U. S., 3, 22. The Fourteenth Amendment and

these statutes enacted in furtherance of its purpose

operate to qualify and entitle a colored man to ac

quire property without State legislation discriminat

ing against him solely because of color.”

The opinion then refers to and distinguishes Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U. S., 537, and other cases, which will be

considered later.

The final paragraph of the opinion states the deliberate

conclusion of this Court:

' “We think this attempt to prevent alienation of

the property in question to a person of color was

not a legitimate exercise of the police power of the

14

State, and is in direct violation of the fundamental

law enacted in the Fourteenth Amendment of the

Constitution preventing State interference with prop

erty rights except by due process of law. That being

the case the ordinance cannot stand.”

We have, therefore, the solemn pronouncement of this

tribunal, that it was not within the legislative power of the

State, or any of its instrumentalities, to forbid Mrs. Corri

gan from selling her house to Mrs. Curtis, or the latter

from purchasing and occupying it.

For the reasons considered in Buchanan V. 'Worley, it

would have been beyond the legislative power to have en

acted that a covenant in the precise terms of that involved

in the present case should be enforceable by the courts by

suit in equity and by means of a decree of specific perfor

mance, an injunction, and proceedings for contempt for

failure to obey the decree. It seems inconceivable that, so

long as the legislature refrains from passing such an en

actment, a court of equity may, by its command, compel

the specific performance of such a covenant, and thus give

the sanction of the judicial department of the Government

to an act which it was not within the competency of its

legislative branch to authorize.

As has been shown, this court has repeatedly included

the judicial department within the inhibitions against the

violation of the constitutional guaranties which we have

invoked.

We cannot emphasize too strongly that the immediate

consequence of the decrees now under review is to bring

about that which the legislative and executive departments

of the Government are powerless to accomplish. It would

seem to follow that by these decrees the appellants have

been deprived of their liberty and property, not by indi

vidual, but by governmental action. These decrees have all

the force of a statute. They have behind them the sov

ereign power. It is not Buckley, the appellee, but the sov

ereignty, which speaks through the Court, that has issued

15

a mandate to the appellants which prevents Mrs. Corrigan

from selling, leasing or giving her property to Mrs. Curtis,

and the latter from acquiring and occupying the property,

simply because she is of the negro race or blood.

In rendering these decrees, the Courts which have pro

nounced them have functioned as the law-making power.

It is they who are seeking to effectuate the policy of racial

segregation based on color. They have virtually an

nounced to all colored persons: “You shall not inherit,

purchase, lease, sell or hold real property for the acquisi

tion of which you have entered into a contract, simply be

cause you are of the negro race or blood.” They have told

those of the white race who have entered into a covenant

such as is referred to in the decrees: “You shall not sell,

lease or give your property to any person of the negro race

or blood.”

They have practically declared: “ If the owners of prop

erty in a particular locality, however extensive its area

may be, see fit to agree on such a policy of segregation,

these Courts, sitting in equity, may nevertheless by their

decrees enforce such a policy, even if it be conceded that

they would be prohibited from doing so by the decision of

the Supreme Court of the United States if the legislative

branch of the Government had established a like policy.”

To test the incongruity of such a situation, let us sup

pose that after the decision in Buchanan v. Worley the

Common Council of the City of Louisville had adopted an

ordinance permitting the residents of the same districts

which were affected by the ordinance which this Court had

declared unconstitutional, to enter into a covenant in the

precise terms of that which the Courts below have enforced

in this case, would it not at once have been said that it was

an intolerable invasion of the Constitution as interpreted

by this Court. But that is exactly what has been done in

the present case by the adjudications which are now here

for review.

Or let us suppose, that after the rendition of these de

16

crees, Mrs. Corrigan, standing on her constitutional rights,

had executed a deed of the premises here in question to

Mrs. Curtis, and the latter had proceeded to occupy them,

would it have been within the competency of the court to

have imprisoned either or both of them as for a contempt

of court? The exercise by the Court of its power to enforce

its decrees through the medium of contempt proceedings,

would be nothing more or less than the enforcement of the

policy of racial segregation based on color, in violation of

the letter and spirit of the Constitution as interpreted in

Buchanan v. Warley.

After Buchanan v. Warley had been remanded by this

Court to the Kentucky Court of Appeals for further pro

ceedings not inconsistent with the opinion rendered, would

this Court have countenanced an amendment of the decree

which it had reversed, providing that ninety per cent, of

the residents of the district in which segregation had been

attempted might enter into a covenant in precisely the

same terms as the ordinance and that, thereupon, such

covenant should be in full force and effect?

In Gondolfo v. Hartman, 49 Fed. Rep., 181, Judge Ross

said (p. 182) :

“ It would be a very narrow construction of the con

stitutional amendment in question and of the decisions

based upon it, and a very restrictive application of the

broad principles upon which both the amendment and

the decisions proceed, to hold that, while the State and

municipal legislatures are forbidden to discriminate

against the Chinese in their legislation, a citizen of the

State may lawfully do so by contract, which the Courts

may enforce. Such view is, I think, entirely inadmis

sible. Any result inhibited by the Constitution can no

more be accomplished by contract of individual citi

zens than by legislation, and the Court should no

more enforce the one than the other. This would seem

to be very clear.”

17

After citing Kennett v. Chambers, 14 How., 49, the opin

ion continues (p. 183) :

“But the principle governing the case is, in my

opinion, equally applicable here, where it is sought to

enforce an agreement made contrary to the public pol

icy of the government, and in violation of the prin

ciples embodied in its Constitution. Such a contract

is absolutely void and should not be enforced in any

court, certainly not in a court of equity of the United

States.”

In Plessy v. Ferguson, as pointed out by this Court,

there was no attempt to deprive all persons of color of

transportation in the coaches of a public carrier. The ex

press requirements of the statute there challenged were

for equal, though separate, accommodations for the white

and colored races.

On the other hand, in McCabe v. Atchison, Topeka &

Santa Fe By. Co., 235 U. S., 151, a statute which allowed

railroad companies to furnish dining cars for white peo

ple and to refuse to furnish them for colored people, was

held to be unconstitutional.

The Applicability of Constitutional Amendments to the

District of Columbia.

In the opinion rendered by the Supreme Court of the

District of Columbia in the present case it was suggested

{Bee., p. 12) that the Court of Appeals of the District

had held that the Fourteenth Amendment was not in force

in the District of Columbia, citing Siddons v. Edmonston,

42 App. D. C., 459; at the same time adding that since

the provisions of that Amendment are, so far as concerns

the question here involved, as broad at least as those ol

the Fifth and Thirteenth Amendments and if the provi

sions of the Fourteenth Amendment would not, if applica

ble, sustain the defendants’ contention, it was unnecessary

18

to consider the other two Amendments (District of Colum

bia v. Brooke, 214 U. S., 138, 149). In that view of the

case, the Court decided that the Fourteenth Amendment

did not sustain the defendants’ contention.

We have already considered that aspect of the subject.

We deem it appropriate, however, to call attention to the

decisions which we contend render applicable to the Dis

trict of Columbia the several constitutional amendments

to which reference has been made.

In Downes v. Bidioell, 182 U. S., 244, 259, 263, the ap

plicability of the Constitution to the District of Colum

bia was exhaustively considered. Referring to Loughbor

ough v. Blake, 5 Wheat., 317, attention was called to the

fundamental fact that the District of Columbia consisted

of territory which had been originally a part of the States

of Maryland and Virginia. Subsequently, in 1846, the

portion of the territory granted by Virginia was retro

ceded to that State (9 II. S. St. L., 35; Evans v. United

States, 31 App. D. C., 544). Therefore the territory that

now constitutes the District of Columbia was Maryland

territory. Consequently, as said by Mr. Justice Brown:

“ It had been subject to the Constitution and was

a part of the United States. The Constitution had

attached to it irrevocably. There are steps which can

never be taken backward. The tie that bound the

States of Maryland and Virginia to the Constitution

could not be dissolved, without at least the consent

of the Federal and State governments to a formal

separation. The mere cession of the District' of

Columbia to the Federal government relinquished the

authority of the States, but it did not take it out of

the United States or from under the aegis of the Con

stitution. Ueither party had ever consented to that

construction of the cession. If, before the District

was set off, Congress had passed an unconstitutional

act, affecting its inhabitants, it would have been void.

19

If done after the District was created, it would have

been equally void; in other words, Congress could not

do indirectly by carving out the District what it could

not do directly. The District still remained a part

of the United States, protected by the Constitution.

Indeed, it would have been a fanciful construction to

hold that territory which had been once a part of

the United States ceased to be such by being ceded

directly to the Federal government.”

It was accordingly held that Article I, Section 8, of the

Constitution, which gave Congress the power “to lay and

collect taxes, imposts and excises” which “shall be uni

form throughout the United States,” extended to the Dis

trict of Columbia. This conclusion, so far as it affected

the District of Columbia, was approved in the opinion of

Mr. Justice Brown, although he and four other Justices

of this Court did not consider the constitutional provi

sion there under consideration as applicable to the Terri

tories. On the other hand, however, the members of the

Court who were in the minority, namely, Chief Justice

Fuller, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer and Mr.

Justice Peckham, went even further than Mr. Justice

Brown, and held that the constitutional provision followed

the flag and operated throughout “the geographical

unit knoAvn as the United States,” “ our great Republic,

which is composed of States and Territories” (182 U. S.,

356). It follows that a majority of the Court recognized,

that the Constitution applied to the District of Columbia.

It has been held expressly that the Fourth Amendment,

relating to searches and seizures, Stoutenburgh v. Frasier,

16 App. D. C., 229, Curry v. District of Columbia, 14 App.

D. C., 423; the Fifth Amendment, Wight v. Davidson, 181

U. S., 371, Moses v. United States, 16 App. D. C., 428; the

Eighth Amendment, concerning excessive bail, fines and

unusual punishments, Stoutenburgh v. Frazier, 16 App.

D. C., 229; and the provisions relating to jury trials, Cal-

20

Ian v. Wilson, 127 U. S., 510, are all applicable to the

District of Columbia.

In Gurry v. District of Columbia, supra, the Court said:

“Ho more in the District of Columbia than any

where else within the United States, could the legis

lature of the Union pass a bill of attainder or an

ex post facto law, or dispense with trial by jury, or

establish a religion, or authorize unreasonable

searches. All the general limitations imposed by the

Constitution upon its authority are as applicable in

the District of Columbia as in any other part of the

United States. And not only are these express limita

tions applicable, but * * * all the ‘implied limita

tions which grow out of the nature of all free gov

ernments’ are equally applicable. The ‘exclusive’

power of legislation over this District which is vested

in Congress by the Constitution, must be assumed to

extend only to all lawful subjects of legislation; and

invasions of those fundamental individual rights,

which lie at the foundation of the social compact, and

for the maintenance of which free governments exist,

are not lawful subjects of legislation.”

In Lappin v. District of Columbia, 22 App. D. C., 68,

75, Mr. Justice Shepard said:

“It must be conceded that the Fourteenth Amend

ment, which expressly declares that no State shall

deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the laws, does not purport to extend to

authority exercised by the United States. But it

does not follow that Congress in exercising its power

of legislation within and for the District of Columbia

may, therefore, deny to persons residing therein the

equal protection of the laws. All of the guaranties

of the Constitution respecting life, liberty, and prop

21

erty are equally for the benefit and protection of all

citizens of the United States residing permanently

or temporarily within the District of Columbia, as of

those residing in the several States. Gallan v. Wil

son, 127 U. S., 510; United States ex rel. Kerr v. Ross,

5 App. D. C., 211, 217; Gurry v. District of Columbia,

11 App. D. C., 123.”

In Gallan V. Wilson, supra, Mr. Justice Harlan said (p.

519) :

“And as the guarantee of a trial by jury, in the

third article, implied a trial in that mode and accord

ing to the settled rules of the common law, the enu-

meration in the Sixth Amendment, of the rights of

the accused in criminal prosecutions, is to be taken

as a declaration of what those rules were, and is to

be referred to the anxiety of the people of the States

to have in the supreme law of the land, and so far

as the agencies of the General Government were con

cerned, a full and distinct recognition of those rules,

as involving the fundamental rights of life, liberty

and property. This recognition was demanded and

secured for the benefit of all the people of the United

States, as well those permanently or temporarily re

siding in the District of Columbia, as those residing

or being in the several States. There is nothing in

the history of the Constitution or of the original

amendments to justify the assertion that the people

of this District may be lawfully deprived of the bene

fit of any of the constitutional guarantees of life, lib

erty and property—especially of the privilege of trial

by jury in criminal cases.”

In the opinion of Mr. Justice Brown in Downes V. Bid-

well, supra, Gallan v. Wilson was declared to be in line

with Loughborough v. Blake.

In Smoot v. Heyl, 227 U. S., 518, which related to the

22

validity of a building regulation adopted by the Commis

sioners of the District of Columbia, -which was challenged

on the ground that it was “unconstitutional and void be

cause its effect is to deprive your complainants of their

property without due process of law and just compensa

tion,” this Court, in assuming jurisdiction, necessarily de

cided that the due process clause of the Constitution was

applicable to the District of Columbia; and in the subse

quent case of Walker v. Gish, 260 U. S., 447, in which the

validity of a regulation relating to party walls in the City

of Washington was challenged on the same ground, this

Court likewise considered the due process clause as ap

plicable to the District of Columbia.

In Block v. Hirsh, 256 XL S., 135, in which the consti

tutionality of the Rent Laws of 1919 enacted for the Dis

trict of Columbia was attacked on the ground that .they

involved the taking of property not for public use and

without due process of law, this Court elaborately dis

cussed their constitutionality; as it did in Ghastleton Cor

poration v. Sinclair, 264 U. S., 543, that of the act passed

in 1922, whereby it was attempted to extend the duration

of these laws.

In Adkins v. Children’s Hospital, 261 U. S., 525, which

related to the constitutionality of the District of Colum

bia Minimum Wage Law, this Court declared the law to

be in contravention of the Constitution, particularly of

the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment.

When, therefore, the Court below (Bee., p. 12), in the

face of these decisions, based its assertion that the Four

teenth Amendment was not in force in the District of

Columbia, on the alleged authority of Siddons v. Edmon-

ston, 42 App. D. C., 459, it is not surprising that we find

that the Court there confined itself to a bald statement

which as the context shows was clearly obiter,

“The prohibition in this Amendment, to which the

appellee refers, applies to the States and not to the

District of Columbia.”

23

It is, however, surprising that the citation in support of

that assertion is District of Columbia v. Brooke, 214 U. S.,

138, when it distinctly appears that in that case, this Court

declared it to be unnecessary to determine whether or not

the Fourteenth Amendment applied to the District of Co

lumbia, because it was conceded that the Fifth Amend

ment unquestionably did, and that it was not more exten

sive in its provisions than the Fourteenth Amendment.

Therefore, reaching the conclusion that the legislation

which was challenged on the ground that it denied the

equal protection of the laws, merely involved such classifi

cation as had frequently been regarded as permissible

under the Fourteenth Amendment, it was upheld as consti

tutional.

Hence, this Court did not in District of Columbia v.

Brooke render a decision warranting its citation as author

ity for the proposition asserted.

It would seem, however, that if, as adjudged in Lough

borough v. Blake and Downes v. Bidwell, the Constitution

became irrevocably attached to the land which originally

was a part of Maryland, upon its incorporation into the

District of Columbia, the Constitution in its entirety be

came applicable to the District of Columbia. The Thir

teenth Amendment, which abolished slavery and involun

tary servitude, certainly did; that portion of the Four

teenth Amendment which related to citizenship, unques

tionably did; as did the Fifteenth, Sixteenth and nine

teenth Amendments.

The suggestion that, because the prohibitions of Section

1 of the Fourteenth Amendment, against the abridgment of

the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United

States and against the deprivation of any person of life,

liberty and property without due process of law and the

denial to any person “within its jurisdiction” of the equal

protection of the laws” , begin with the words “bio State”

and “Nor shall any State” , they do not apply to the Dis

trict of Columbia, is a proposition that disregards the

24

manifest intention which gave rise to this Amendment and

the historical conditions out of which it arose. Prom a con

stitutional standpoint, the District of Columbia at that

time was regarded as on the same level with the State of

Maryland, of which it had constituted a part.

To give so narrow an interpretation to the word “ State”

ignores not only the history of the District of Columbia,

but also the fact that it was the very nucleus of the storm-

centre out of which emerged the Fourteenth Amendment,

that it was there that not only the Civil War had its most

important setting, but where the pre-war and the post-war,

scenes of the great drama which culminated in the adop

tion of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments were

enacted. It is, therefore, as inconceivable that the District

of Columbia is to be excluded from the operation of the

Fourteenth Amendment as that it was intended to exclude

it from the operation of the Eighteenth Amendment.

This Court had occasion in Geofroy v. Riggs, 133 IT. S.,

258, to consider the phrase “ States of the Union” as con

tained in a clause of a treaty between the United States

and France which related to the right of Frenchmen to en

joy the privilege of possessing personal and real property

in “the States of the Union” . There the question arose as

to whether under this treaty, a citizen of France could take

land in the District of Columbia by descent from a citizen

of the United States. It was held that the District of Co

lumbia, as a political community, was one of “ the States of

the Union” within the meaning of that term as used in the

treaty, Mr. Justice Field saying in support of that conclu

sion:

“ This article is not happily drawn. It leaves in

doubt what is meant by ‘States of the Union’. Ordi

narily these terms would be held to apply to those

political communities exercising various attributes of

sovereignty which compose the United States, as dis

tinguished from the organized municipalities known

as Territories and the District of Columbia. And yet

25

separate communities, with an independent local gov

ernment, are often described as states, though the ex

tent of their political sovereignty be limited by rela

tions to a more general government or to other coun

tries. Halleck on Int. Law, c. 3, sections 5, 6, 7. The

term is used in general jurisprudence and by writers

on public law as denoting organized political societies

with an established government. Within this defini

tion the District of Columbia, under the government

of the United States, is as much a State as any of

those political communities which compose the United

States. Were there no other territory under the gov

ernment of the United States, it would not be ques

tioned that the District of Columbia would be a State

within the meaning of international law; and it is not

perceived that it is any less a State within that mean

ing because other States and other territory are also

under the same government. In Hepburn v. Elisey, 2

Cranch, 445, 452, the question arose whether a resident

and a citizen of the District of Columbia could sue a

citizen of Virginia in the Circuit Court of the United

States. The Court, by Chief Justice Marshall, in de

ciding the question, conceded that the District of Co

lumbia was a distinct political society, and therefore a

State according to the definition of writers on general

law; but held that the act of Congress in providing for

controversies between citizens of different States in

the Circuit Courts, referred to that term as used in the

Constitution, and therefore to one of the States com

posing the United States. A similar concession, that

the District of Columbia, being a separate political

community, is, in a certain sense, a State, is made by

this Court in the recent case of Metropolitan Railroad

Go. v. District of Columbia, 132 U. S., 1, 9, decided at

the present term.”

In Talbot v. Silver Bow County, 139 U. S., 444, Mr. Jus

tice Brewer, referring to a statute of Montana Territory

26

which undertook to tax the shares of a national bank pur

suant to Section 5219 of the Revised Statutes, which con

ferred the power of taxation upon the legislature of each

State, no reference being made to Territories, said:

“But it would militate much against its national

character if banks organized under it (the national

banking system) were subjected to local taxation in

one part of the Union, and exempted from it else

where. ISTo such intent ought lightly to be imputed to

Congress. * * *

Still further, while the word ‘State’ is often used in

contradistinction to ‘Territory’, yet in its general pub

lic sense, and as sometimes used in the statutes and

the proceedings of the government, it has the larger

meaning of any separate political community, includ

ing therein the District of Columbia and the Territor

ies, as well as those political communities known as

States of the Union. Such a use of the word ‘State’

has been recognized in the decisions of this Court.”

Then follow quotations from Hepburn v. Elisey, Metro

politan Railroad Go. v. District of Columbia and Qeofroy

v. Riggs, supra.

At all events, there can be no question but that the due

process clause of the Fifth Amendment applies to the Dis

trict of Columbia, and, as has been shown, the same inter

pretation that has been given to the Fourteenth Amend

ment as to its applicability to the action of the judicial as

well as of the executive and legislative departments of the

Government, has been given to the Fifth Amendment.

The Right to Review the Rulings on Public Policy on

this Appeal.

The appeal to this Court has been taken pursuant to Sec

tion 250 of the Judicial Code, for the purpose of present

ing the constitutional questions thus far considered. That

37

merce, gives to every absolute owner of property who

is sui juris the power to control and dispose of such

property and subject the same to the payment of his

debts, we are fully aware of the fact that many other

authorities may and have been cited to the contrary.”

In Barnard v. Bailey, 2 Harrington (Del.), 56, a con

dition in a devise that the devisee should not dispose of

the property to the blood kin of either the testator or the

devisee, was held to be bad.

In Williams V. Jones, 2 Swan (Tenn.), 620, there was

a bequest to A on condition that she should not dispose

of the property so as to allow either of four persons to

get it. The condition was declared to be void.

In Brothers v. McCurdy, 36 Pa. St., 407, a testator di

rected that land devised to his son should not be sold to

any person for the purpose of making brick or carrying

on a brickmaking business, and more especially that he

should not sell it to Lotz and Beasley, and declared that

the devise of the lot was to be void in case of a sale con

trary to his will, in which event the lot was to be held

in common by the testator’s other heirs. The gift over

was adjudged to be void.

See also He Rosher, L. B. 26 Ch. Div., 801, 816, and Re

Dugdale, L. R. 38 Ch. Div., 176, 179, in both of which

cases In re Macleay, L. R. 20 Eq., 186, was disapproved,

as it likewise was in Manierre v. Welling, 32 R. S., 104.

In Renaud v. Tourangeau, L. R., 2 Privy Counsel App.,

4, where a testator in Lower Canada devised real estate to

her children, providing that they should in no way alien

ate the property until twenty years after his death, the

Judicial Counsellor, per Lord Romilly, held that the re

striction “was not valid either by the old law of France,

or the general principle of jurisprudence.”

In 4 Kent’s Commentaries, 131, Chancellor Kent, dis

cussing this general subject, said:

“ Conditions are not sustained when they are re-

38

pugnant to the nature of the estate granted or in

fringe upon the essential enjoyment and independent

rights of property and tend manifestly to public in

convenience. A condition annexed to a conveyance

in fee or by devise that the purchaser and devisee

should not alien, is unlawful and void. If the grant

be upon condition that the grantee shall not permit

waste or not take the profits, or his wife not have

her dower or the husband his curtesy, the condition

is repugnant and void, for those rights are insepar

able from the estate in fee. Nor could a tenant in

tail, though his estate was originally intended as a

perpetuity, be restrained by any proviso in the deed

creating the estate from suffering a common recovery.

Such restraints were held by Lord Coke to be ab

surd and repugnant to reason and to “ the freedom

and liberty of freemen.” The maxim which he cites

contains a just and intelligent principle worthy of

the spirit of the English law in the best ages of Eng

lish freedom: iniqnum est ingenuis hominibus non

esse liberam rerum suarum alienationem. If, how

ever, a restraint upon alienation be confined to an in

dividual named to whom the grant is not to be made,

it is said by very high authority to be a valid con

dition. But this case falls within the general princi

ple and it may be very questionable whether such a

condition would be good at this day. In Newkirk v.

Newkirk (2 Caines, 345), the Court looked with a

hostile eye upon all restraints upon the free exercise

of the inherent right of alienation belonging to es

tates in fee; and a devise of lands to a testator’s chil

dren in case they continued to inhabit the town of

Hurley, otherwise not, was considered to be unrea

sonable and repugnant to the nature of the estate.”

To the same effect are the following decisions:

Clark v. Clark, 99 Md., 356; 58 Atl. Rep., 24;

29

“ The public policy of this State (New York) when

the legislature acts is what the legislature says that

it shall be.”

Where would one be more likely to arrive at the sources

from which our public policy is derivable than by explor

ing the Constitution and statutes of the United States

and the adjudications of this Court? A student of our

history like DeTocqueville, Bryce or von Holst would at

once be struck by the inconsistency of the principle laid

down in Buchanan V. Warier/, with that expressed in the

opinions rendered in the present case by the Courts below.

It would appear to be obvious that, where a legislature

is prohibited from sanctioning a particular policy, indi

viduals may not enter into contracts in direct derogation

of the same policy. Surely that which a legislature can

not sanction should not be compelled to be done by a

decree of a court of equity enforcing specific performance

of an agreement between third parties, which is the equiva

lent of such legislation and is productive of identical re

sults.

If such a contract as that involved in the present case

is valid as affecting a limited area, it would be equally

effective if it included an entire .city, a county, or a State.

If the Constitution could be evaded as it is attempted to

be by the device here employed, it would not be difficult

to create a situation bearing the elements of a contract

that would prevent a colored person from owning realty,

or from taking up his habitation, in any State or in any

part of a State.

(2) The covenant is- not only one which restricts the

use and occupancy by negroes of the various premises cov

ered by its terms, but it also prevents the sale, conveyance,

lease or gift of any such premises by any of the owners

or their heirs and assigns to negroes or to any person or

persons of the negro race or blood perpetually, or at least

30

for a period of twenty-one years. I t is in its essential

nature a contract in restraint of alienation and is, there

fore, contrary to public policy.

In the present case it is to be observed that the parties

to the instrument sought to be enforced in this action have

covenanted that no part of the land therein described

owned by them “ shall ever be used or occupied by or sold,

conveyed, leased, rented, or given to negroes or any per

son or persons of the negro race or blood” (Bee., p. 7). It

binds the parties, their respective heirs and assigns, for

all time. It is true that in the succeeding sentence it is

declared that the covenant “ shall run with the land * * *

for the period of twenty-one years from and after the date

of these presents.” That does not, however, cut down

the covenant as between the parties so as to limit it to

a period of twenty-one years. But whether the covenant

be regarded as a perpetual covenant or as one running for

twenty-one years only, it is equally opposed to public

policy.

The subject of such restraints is learnedly discussed in

DePeyster v. Michael, 6 is. Y., 497, by Chief Judge Bug

gies. He points out that they were of feudal origin; cre

ative of a violent and unnatural state of things, contrary

to the nature and value of property and the inherent and

universal love of independence; that they arose partly

from favor to the heir and partly from favor to the lord,

“and the genius of the feudal system was originally so

strong in favor of restraints upon alienation, that by a

general ordinance, mentioned in the Book of Fiefs, the

hand of him who wrote a deed of alienation was directed

to be struck off” (p. 498). To deal with this tyranny the

statute of Quia Emptores was enacted in 18 Edward I,

which provided “that from henceforth it shall be lawful

for any freeman to sell, at his own pleasure, his lands

and tenements, or part of them, so that the feoffee shall

hold the same lands and tenements of the chief lord of

the same fee, by such service and customs as the feoffee

held before.”

31

As Chief Judge Buggies says (p. 500) :

“The effect of this statute is obvious. By declaring

that every freeman might sell his land, at his own

pleasure, it removed the feudal restraint which pre

vented the tenant from selling his land, without the

license of his grantor, who was his feudal lord. This

was a restraint imposed by the feudal law, and was

not created by express contract in the deed of con

veyance; it was abolished by this clause in the stat

ute. By changing the tenure from the immediate to

the superior lord, it took away the reversion from

the immediate lord; in other words, from the grantor,

and thus deprived him of the power of imposing the

same restraint, by contract or condition expressed in

the deed of conveyance. The grantor’s right to re

strain alienation immediately ceased, when the stat

ute put an end to the feudal relation between him and

his grantee; and no instance of the exercise of that

right, in England, since the statute was passed, has

been shown, or can be found, except in the case of

the king, whose tenure was not affected by the stat

ute, and to whom, therefore, it did not apply.

The reason given by Lord Coke, why a. condition

that the grantee shall not alien, is void, is as follows:

‘For it is absurd and repugnant to reason, that he

that hath no possibility to have the land revert to

him, should restrain his feoffee of all his power to

alien. And so it is, if a man be possessed of a term

for years, or of a horse, or any other chattel, real

or personal, and give or sell his whole interest or

property therein, upon condition that the donee or

vendee shall not alienate the same, the condition is

void, because his whole interest and property is out

of him, so that he hath no possibility of reverter; and

it is against trade and traffic, and bargaining between

man and man.’ ”

32

In Potter v. Couch, 141 U. S., 296, 313, Mr. Justice Gray

said:

“But the right of alienation is an inherent and in

separable quality of an estate in fee simple. In a

devise of land in fee simple, therefore, a condition

against all alienation is void, because repugnant to

the estate devised. Lit., Sec. 360; Co. Lit., 206b, 223a;

4 Kent Com., 131; McDonogh v. Murdock, 15 How.,

367, 373, 412. For the same reason, a limitation over,

in case the first devisee shall alien, is equally void,

whether the estate be legal or equitable. Howard v.

Carusi, 109 IT. S., 725; Ware v. Cann, 10 B. & G,

433; Shaw v. Ford, 7 Ch. D., 669; In re Dugdale, 38

Ch. D., 176; Corbett v. Corbett, 13 P. D,, 136; Steib

v. Whitehead, 111 Illinois, 247, 251; Kelley v. Meins,

135 Mass., 231, and cases there cited. And on princi

ple, and according to the weight of authority (not

withstanding opposing dicta in Cowell v. Springs Co.,

100 U. S., 55, 57, and in other books), a restriction,

whether by way of condition or of devise over, on

any and all alienation, although for a limited time,

of an estate in fee, is likewise void, as repugnant to

the estate devised to the first taker, by depriving him

during that time of the inherent power of alienation.

Roosevelt v. Thurman, 1 Johns., Oh. 220; Mandlebaum

v. McDonell, 29 Mich., 77; Anderson v. Cary, 36 Ohio

St., 506; Twitty v. Camp, Phil. Eq. (No. Car.) 61; In

re Rosher, 26 Ch. D., 801.”

Especial attention is called to the exhaustive opinion

in Manierre v. Welling, 32 R. I., 104, where many cases

are cited and ably reviewed, and where one of the import

ant conclusions reached in the case next to be cited was

adopted:

“We are entirely satisfied there has never been a

time since the statute quia emptores when a restric-

33

tion in a conveyance of a vested estate in fee sim

ple, in possession or remainder, against selling for a

particular period of time, was valid by the common

law. And we think it would be unwise and injurious

to admit into the law the principle contended for by

the defendant’s counsel, that such restrictions should

be held valid, if imposed only for a reasonable time.

It is safe to say that every estate depending upon

such a question would, by the very fact of such a

question existing, lose a large share of its market

value. Who can say whether the time is reasonable,

until the question has been settled in the Court of

last resort; and upon what standard of certainty can

the Court decide it? Or, depending as it must upon

all the peculiar facts and circumstances of each par

ticular case, is the question to be submitted to a jury?

The only safe rule of decision is to hold, as I under

stand the common law for ages to have been, that a

condition or restriction -which would suspend all

power of alienation for a single day, is inconsistent

with the estate granted, unreasonable and void.”

Equally important is the classic opinion of Mr. Jus

tice Christiancy in Mandlebaum v. McDonell, 29 Mich.,

79, from which the foregoing excerpt is taken. That deci

sion was approved not only by this Court in Pottei v.

Couch, 141 IT. S., 315, 316, but also by the English Court

of Chancery in Tie Posher, L. B. 26 Ch. Div., 801, an un

usual compliment, especially since it resulted in the re

jection of the decision of Sir George Jessel in lie Macleay,

L. E. 20 Eq., 186.

The significance of this proposition is regarded as a

justification for the citation of the following pertinent

decisions.

In Smith v. Clark, 10 Md., 186, a devise of a woodlot

to the testator’s wife and daughters “ on the express con

dition that the same is not at any time to be cleared or

34

converted into arable land,” and a further condition that

the land “ shall be at all times held together by those

who may be entitled to the same by virtue of the will,”

was held to be void.

In McCullough’s Heirs v. Gilmore, 11 Pa. St., 370, the

testator declared it to be his will and desire that a certain

farm “ fall into the possession of W, laying this injunction

and prohibition not to leave the same to any but the le

gitimate heirs of W ’s father’s family at his W ’s decease.”

This restraint on the power of alienation was held to be

void.

In Bennett v. Chapin, 77 Mich., 527, it was held that

when a restriction in a conveyance of a vested estate in

fee simple, in possession or remainder, is against selling

for a particular time, such restriction is invalid. Mr.

Justice Long said:

“ Such restraints are not favored in the law. It is

true that many restrictions or qualifications upon the

rights of the devisee or grantee may be made effectual

by making the estate itself dependent upon such con

dition ; but where the estate granted is absolute, such

restriction can impose no legal obligation upon the

devisees, or limit their power over the estate, when

the observance or violation of the restriction can

neither promote nor prejudice any interest but their

own. This rule was very fully discussed by this Court

in Mandlebaum v. McDonell, 29 Mich., 87, and in

support of this principle the Court cited Hall v. Tufts,

18 Pick., 459; Bank v. Davis, 21 Id., 42; Brandon v.

Robinson, 18 Yes., 429; Doebler’s Appeal, 64 Pa. St.,

9; Craig V. Wells, 11 N. Y., 315.

Aside from these reasons, however, we think the re

strictions upon the sale cannot be upheld. ISTo such

restrictions are valid. When a restriction in a con

veyance of a vested estate in fee simple, in possession

or remainder, is against selling for a particular time,

35

such a restriction is invalid. When a person is en

titled absolutely to property, any provision postpon

ing its transfer or payment to him is void. Gray,

in his rules against Perpetuities, thus states the rule:

‘Suppose property is given to trustees in trust to

pay the principal to A when he reaches thirty. When

any other person than A is interested in the prop

erty, when, for instance, there is a gift over to B if

A dies under thirty, the trustee will retain the prop

erty for the benefit of B ; but when no one but A is

interested in the property, when, should he die before

thirty, his heirs or representatives would be entitled

to it, when, in short, the direction for postponement

has been made for A ’s supposed benefit, such direc

tion is void, in pursuance of the general doctrine that

it is against public policy to restrain a man in the

use or disposition of the property in which no one but

himself has any interest.’

The principle is generally held to be that all rights

of property are alienable, and that a condition or re

striction which would suspend all power of alienation

for any length of time is inconsistent with the estate

granted, and void.”

In Attioater v. Attwater, 18 Beavan, 330, a devise of cer

tain real estate to A “to become his property on attain

ing the age of twenty-five years, with the injunction never

to sell it out of the family, but if sold at all it must be

to one of his brothers hereinafter named,” wms held to be

in restraint of alienation, and void.

In Billing v. Welch, Irish Rep., 6 Common Law, 88, a

covenant by the grantee of land that he, his heirs and as

signs would not alien, sell or assign to any one except his

or their child or children without the license of the

grantor, was declared void on the authority of the opinion

of Lord Romilly in Attwater v. Attwater, supra.

In Schermerhorn v. Negus, 1 Denio, 148, a provision in

36

a devise to children that no part of the land should he

aliened by any of the children or their descendants ex

cept to each other or their descendants, was held bad.

To the same effect are the decisions in Johnson v. Pres

ton, 226 111., 447, 462, and Pardue v. Givens, 54 N. C.,

306.

In Anderson v. Carey, 36 Ohio St., 506, the testator de

vised a farm to his two sons, Thomas and Lincoln, upon

condition that they should not be allowed to sell and dis

pose of it until the expiration of ten years from the time

his son Lincoln arrived at full age, except to one another,

nor to mortgage or encumber it in any manner whatsoever

except in the sale to one another. It was held that the

restraint attempted to be imposed was void as repugnant

to the devise and contrary to public policy. Mr. Justice

Mcllvaine said:

“ Instead of giving to his sons an estate in the land

less than a fee simple the intent and purpose was to

give them the fee simple but to eliminate therefrom

this inherent element of alienability for a limited

period or to incapacitate his devisees, although sui

juris, from disposing of their property for the same

limited period, to wit, until the younger should ar

rive at thirty-one years of age—each and both of

which purposes was repugnant to the nature of the

estate devised. By the policy of our laws it is of the

very essence of an estate in fee simple absolute, that

the owner, who is not under any personal disability

imposed by law, may alien it or subject it to the pay

ment of his debts at any and all times; and any at

tempt to evade or eliminate this element from the

fee simple estate, either by deed or by will, must be

declared void and of no force. * * * In holding

that such restraint is repugnant to the nature of the

estate devised and is void as against public policy,

which, in this State, in the interests of trade and com-

27

procedure was pursued in Smoot v. Heyl, 227 U. S., 518,

and in Walker v. Gish, 260 U. S., 447.

In the first of these cases it was also decided that the ap

peal brought the entire case here, thus enabling this Court

to determine not merely the question of constitutionality,

but all other questions involved in the record.

Horner v. United States, No. 2, 143 U. S., 570;

Penn Mutual Life Ins. Go. v. Austin, 168 U. S.,

695.

This is in conformity with the procedure under Section

238 of the Judicial Code as laid down in numerous cases.

Pursuing the procedure thus authorized we will proceed

to discuss other questions presented by the record and set

forth in the assignments of error—

II.

The covenant the enforcement of which has been

decreed by the Courts below Is contrary to public

policy.

(1) The public policy of this country is to be ascer

tained from its Constitution, statutes and decisions, and

the underlying spirit illustrated by them.

The constitutional provisions considered under Point I

unmistakably indic;ite that the segregation of colored peo

ple from white people and the statutory prohibition

against the occupancy by colored persons of houses in re

stricted areas, are contrary to the genius of our institu

tions. An act which the legislature is prohibited from

doing or authorizing must in its essence, necessarily be

opposed to public policy. So, likewise, whatever the leg

islative branch of the Government inhibits must he an

offence against public policy.

28

As has been shown, Section 1978 of the Revised Stat

utes declares that all citizens of the United States shall

have the same right in every State and Territory as is en

joyed by white citizens thereof, to inherit, purchase, lease,

sell, hold and convey real and personal property. One

would suppose that, if in the face of such a declaration

a contract is entered into calculated to prevent the inheri

tance, purchase, lease, sale, holding and conveyance of

real property by colored citizens of the United States in

any State or Territory, such a contract is repugnant to

our policy. It certainly was not intended that, if the white

citizens of Washington agreed among themselves that

they would not sell or lease any real property lying within

the territorial limits of that city to a colored person, such

an agreement would be enforceable as consonant with the

controlling public policy.

And so when this Court has announced that legislation

looking to the prevention of the acquisition of realty with

in a specified district by colored persons, is contrary to

the Constitution and laws, it would seem to follow that

a covenant between the white residents of that same dis

trict intended to prevent the acquisition of realty by col

ored persons, was contrary to our public policy.

In Vidal v. Girard’s Executors, 2 How., 127, Mr. Justice

Story pointed out that the policy of Pennsylvania on a

particular subject was indicated by its Constitution and

laws and judicial decisions. This view has been frequently

adopted.

Hartford Fire Ins. Co. v. Chicago, M. & St. P.

R. R. Co., 70 Fed. Rep., 201, 202;

Hollins v. Drew Theological Seminary, 95 Y. Y.,

172;

Cross v. United States Trust Co., 131 1ST. Y., 344;

People V. Hawkins, 157 1ST. Y., 12.

In Messer smith v. American Fidelity Co., 232 N. Y.,

161, 163, Judge Cardozo said:

39

Winsor v. Mills, 157 Mass., 362; 32 N. E. Rep.,

352;

Latimer v. Waddell, 119 1ST. C., 370; 26 S. E. Rep.,

122;

Re Schilling, 102 Mich., 612;

Zillmer v. Landgutb, 94 Wis,, 607; 69 if. W. Rep.,

568;

Jones v. Port Huron Engine & Thresher Go., 171

111., 502; 49 if. E. Rep., 700.

That the natural operation of such a covenant as that

under consideration is opposed to the public welfare, is il

lustrated by the allegations of the bill of complaint. It

there appears (Rec., pp. 4, 5) that after Mrs. Corrigan had

entered into the contract to sell her residence to Mrs. Cur

tis, a number of the other parties to the covenant protested

against her act. Whereupon Mrs. Corrigan wrote to these

persons stating “ in effect that her personal interests made

it imperative that she dispose of said lands and premises at

once.” She offered, however, to sell the premises to them

on the same terms as were provided in the contract of sale

to Mrs. Curtis, provided they would indemnify her, but the

plaintiff alleges “that such proposal last named has not

been and will not be accepted by plaintiff, nor, so far as

plaintiff is aware and believes, by any of the other parties

to said indenture or covenant.”

By reason of this covenant Mrs. Corrigan, therefore,

however imperative her needs, is prevented from selling

her property to a willing purchaser at a price which her

co-covenantors are unwilling to pay. She is thus at their

mercy, as are her creditors. The market value of her prop

erty is consequently seriously impaired, and as the years

go on and surrounding conditions are likely to change, its

marketability may become more and more lessened, and

with it its assessable value, to the serious detriment of the

public.

40

(3) Independently of our public policy as deduced from

the Constitution, statutes and decisions, with respect to

the segregation of colored persons and the fact that the

covenant sued upon is in restraint of alienation, we con