Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v. Feeney Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

February 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v. Feeney Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amici Curiae, 1979. ee839d26-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e14096f4-76ca-44bf-a857-e1d4e725882a/personnel-administrator-of-massachusetts-v-feeney-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 13, 2026.

Copied!

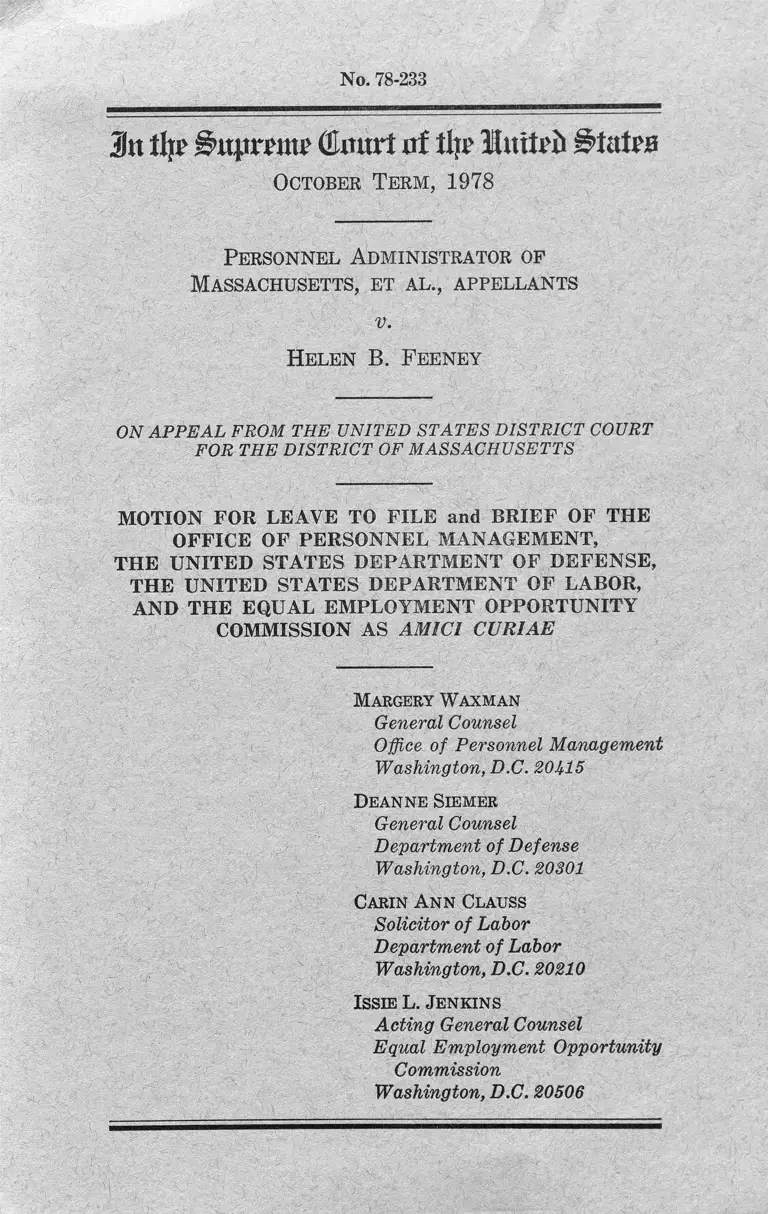

No. 78-233

3u tlrr kapron? (Emtrt uf % l u t t ^ States

O ctober T e r m , 1978

P e r so n n e l A d m in is t r a t o r of

M a ssa c h u se tts , e t a l ., a p p e l l a n t s

v.

H e l e n B. F e e n e y

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE and BRIEF OF THE

OFFICE OF PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT,

THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE,

THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR,

AND THE EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION AS AMICI CURIAE

Margery W axman

General Counsel

Office of Personnel Management

Washington, D.C. 20415

Deanne Siemer

General Counsel

Department of Defense

Washington, D.C. 20301

Carin A nn Clauss

Solicitor of Labor

Department of Labor

Washington, D.C. 20210

Issie L. Jenkins

Acting General Counsel

Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission

Washington, D.C. 20506

Jfu % ^ityirnttF (Em trt ttf tlji> lu ttr ii B U xU b

October Term, 1978

No. 78-233

Personnel Administrator of

Massachusetts, et al., appellants

v.

Helen B. Feeney

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS

MOTION OF THE

OFFICE OF PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT,

THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE,

THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR,

AND THE EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION FOR LEAVE TO FILE A BRIEF

AS AMICI CURIAE

The undersigned agencies move for leave to file the

annexed brief amici curiae to bring before the Court

certain considerations, not set forth in the briefs

hitherto filed, which we believe will be of interest to

the Court.

The Office of Personnel Management, which has as

sumed many of the functions of the Civil Service Com-

(1)

2

mission, manages federal employment operations and

has the primary responsibility for development of

policies governing federal civilian employment. Civil

Service Reform Act of 1978, Pub. L. No. 95-454, 92

Stat. 1119-1120; Reorganization Plan No. 2 of 1978,

43 Fed. Reg. 36037 (1978). As the central federal

personnel agency, OPM controls the examination and

ranking of job applicants and implementation of the

federal veterans’ preference. It, therefore, has an in

terest in insuring that the decision in this case does

not adversely affect the federal veterans’ preference

provisions. After reading ail the briefs filed in this

case, OPM believes that there is information available

concerning the differences between the Massachusetts

and the federal statute which is not contained in the

briefs and which should be presented to the Court.

The Department of Defense carries out the consti

tutional responsibility of the Executive Branch to

raise and support armies (Article I, Section 8, clauses

12 and 13). The Department has a direct interest in

encouraging and rewarding service in the armed

forces.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

and the Department of Labor have the major re

sponsibility for enforcing federal statutes prohibiting

discrimination on the basis of race or sex in employ

ment. EEOC also has been charged with the “ de

velop [ment] of uniform standards * * * and policies

defining the nature of employment discrimination on

the ground of race * * * [or] sex * * * under all Fed

eral statutes * * * and policies which require equal

3

employment opportunity.” Executive Order No. 12067,

43 Fed. Reg. 28967 (1978); see also Reorganization

Plan No. 1 of 1978, 43 Fed. Reg. 19807 (1978). The

Women’s Bureau of the Labor Department is respon

sible for “ formulat[ing] standards and policies which

shall promote the welfare of wage-earning women.”

29 U.S.C. 13. Thus, EEOC and the Department of

Labor have an interest in the standards for proving

purposeful employment discrimination. The Depart

ment of Labor also has the responsibility for a num

ber of programs which provide special benefits to

veterans.*

The undersigned agencies take no position on the

validity of the Massachusetts veterans’ preference

statute. We believe, however, that important con

siderations concerning the differences between the

federal and the state statute and the relevant proof

requirements have not been adequately addressed in

the briefs filed in this case. We, therefore, request

permission to file a short brief amici curiae setting

forth those considerations.

* 5 U.S.C. 8521 et seq. (Unemployment Compensation— Ex-

Servicemen) ; 29 U.S.C. 49 et seq. (Wagner-Peyser Act) ; 29

U.S.C. 801 et seq. (Comprehensive Employment and Train

ing Act of 1973) ; 38 U.S.C. 2001 et seq. (Job Counselling,

Training and Placement Services for Veterans) ; 38 U.S.C.

2011 et seq. (Employment and Training of Disabled and Viet

nam Era Veterans) ; 38 U.S.C. 2021 et seq. (Veterans’ Reem

ployment Rights).

4

Respectfully submitted.

Margery W axman

General Counsel

Office of Personnel Management

Deanne Siemer

General Counsel

Department of Defense

Carin A nn Clauss

Solicitor of Labor

Department of Labor

Issie L. Jenkins

Acting General Counsel

Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission

I authorize the filing of this motion and the at

tached brief.

February 1979

W ade H. McCree, Jr.

Solicitor General

INDEX TO THE BRIEF

Page

Interest of the Amici Curiae ............................ 1

Summary of Argument................... 2

Argument .............................................................. 5

CITATIONS

Cases:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 ............ 14

Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564.... 11

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339..... . 14

Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, 426 U.S. 88.. 5

Massachusetts Board, of Retirement v.

Murgia, 427 U.S. 307 _______ 11

Mathews v. Diaz, 426 U.S. 67 .................. 6

McGinnis v. Royster, 410 U.S. 263 .......... 13

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 ............ 6

Nashville Gas Co. v. Satty, 434 U.S. 136.. 11

Sugarman v. Dougall, 413 U.S. 634 ....... 6

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metro

politan Housing Development Corp.,

429 U.S. 252 _____ ______ __ ______ 12,13

Washington v. Danis, 426 U.S. 229 .......... 12,14

Constitution, statutes, and regulations:

United States Constitution, Article I, Sec

tion 8, clauses 12 and 13 ...................... 2, 5

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 712, 42

U.S.C. 2000e-ll ...................................... 3

Civil Service Reform Act of 1978, Pub.

L. No. 95-454, 92 Stat. 1119-1120 ....... 2

5 U.S.C, 3310 ............ .............. ................. . 6

5 U.S.C. 3313 ............................................... 6, 9

II

Statutes and regulations— Continued Page

5 U.S.C. 3318(a) ......................................... 9

29 U.S.C. 13 .................................................. 3

Executive Order No. 12067, 43 Fed. Reg.

28967 (1978) ........................ -.................. 3

Reorganization Plan No. 1 of 1978, 43

Fed. Reg. 19807 (1978) ........................ 3

Reorganization Plan No. 2 of 1978, 43

Fed. Reg. 36037 (1978) ........................ 2

Miscellaneous:

Blumberg, De Facto and De Jure Sex

Discrimination under the Equal Pro

tection Clause: A Reconsideration of the

Veterans’ Preference in Public Employ

ment, 26 Buffalo L. Rev. 3 (1977)....... 11

Brest, Palmer v. Thompson: An Approach

to the Problem of Unconstitutional Leg

islative Motive, 1971 Sup. Ct. Rev. 95.. 13,14

Comment, Veterans’ Public Employment

Preference as Sex Discrimination, 90

Harv. L. Rev. 805 (1977) .................... 12

Fleming & Shanor, Veterans’ Preferences

in Public Employment: Unconstitutional

Gender Discrimination?, 26 Emory L.J.

13 (1977) ______ __________________ 10

Note, Reading the Mind of the School

Board: Segregative Intent and the De

Facto/De Jure Distinction, 86 Yale L.J.

317 (1976) ........................................ 14

Veterans’ Preference Oversight Hearings,

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on

Civil Service of the House Committee

on Post Office and Civil Service, 95th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1977) .................... 8, 9,10,11

3n ^ i t j t n w (ftmtri o f il)t IntU 'fc i ’Jalrn

October T e r m , 1978

No. 78-233

P e r so n n e l A d m in istr a to r of

M a ssa c h u se tts , et a l ., a p p e l l a n t s

v.

H e le n B. F e e n e y

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS

BRIEF FOR THE

OFFICE OF PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT,

THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE,

THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR,

AND THE EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY

COMMISSION AS AMICI CURIAE

INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE

The Office of Personnel Management, the Depart

ment of Defense, the Department of Labor, and the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission wish to

present to the Court certain considerations, primarily

(1)

2

regarding the operation of the federal veterans’

preference program, which, we believe, have not been

fully addressed in the briefs of the parties and amici

curiae.

The Office of Personnel Management, which has as

sumed many of the functions of the Civil Service

Commission, manages federal employment operations

and has the primary responsibility for development

of policies governing federal civilian employment.

Civil Service Reform Act of 1978, Pub. L. No. 95-454,

92 Stat. 1119-1120; Reorganization Plan No. 2 of

1978, 43 Fed. Reg. 36037 (1978). As the central

federal personnel agency, OPM controls the exami

nation and ranking of job applicants and implemen

tation of the federal veterans’ preference. The De

partment of Defense carries out the constitutional

responsibility of the Executive Branch to raise and

support armies (Article I, Section 8, clauses 12 and

13). The Department has a direct interest in en

couraging and rewarding service in the armed forces.

OPM and the Department of Defense, therefore, have

an interest in insuring that the decision in this case

does not adversely affect the federal veterans’ pref

erence provisions.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

and the Department of Labor have the major re

sponsibility for enforcing federal statutes prohibiting

discrimination on the basis of race or sex in employ

ment. EEOC also has been charged with the “ develop-

[ment] of uniform standards * * * and policies defin

ing the nature of employment discrimination on the

3

ground of race * * * [or] sex * * * under all Federal

statutes * * * and policies which require equal em

ployment opportunity.” Executive Order No. 12067,

43 Fed. Reg. 28967 (1978); see also Reorganization

Plan No. 1 of 1978, 43 Fed. Reg. 19807 (1978). The

Women’s Bureau of the Labor Department is respon

sible for “ form ulating] standards and policies which

shall promote the welfare of wage-earning women.”

29 U.S.C. 13. Thus, EEOC and the Department of

Labor have an interest in the standards for proving

purposeful employment discrimination.1

The above agencies take no position on the validity

of the Massachusetts veterans’ preference statute.

We believe, however, that there are important con

siderations concerning the difference between the

federal and the state statute and the relevant proof

requirements which have not been adequately ad

dressed in the briefs previously filed in this case and

which will be of benefit to the Court.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. The national interest in compensating and re

warding veterans is different in quality and char

acter from that of the states and would support the

federal system of veterans’ preference regardless of

the decision in this case.

1 Although under Section 712 of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1%4, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-ll, veterans’ employment prefer

ences are expressly exempt from the proscriptions of Title

VII, the EEOC has a substantial interest in the proof re

quirements for employment discrimination generally.

4

Furthermore, the Massachusetts absolute prefer

ence and the federal point preference are substantially

different in both their operation and impact. Al

though each of the preferences adversely affects wom

en, the federal preference is significantly less burden

some on women seeking higher level positions. The

district court found that under the Massachusetts

absolute preference, “ [fjew , if any, females have ever

been considered for the higher positions in the state

civil service” (A. 218). In contrast, studies done by

the U.S. Civil Service Commission indicate that while

the proportion of women hired is lower because of the

federal veterans’ preference, women nevertheless have

constituted more than one-fourth of those hired for

federal jobs requiring professional or administrative

skills. Thus the federal point preference, which in

sures some measure of individual competition, is

considerably less extreme in effect than Massachu

setts’ absolute preference.

2. Although the extent and form of veterans’ bene

fits is a matter to be determined by the legislature,

not every veterans’ preference, no matter how irra

tional or extreme, must survive constitutional chal

lenge. Even though such legislation unquestionably

serves a legitimate goal, if an illicit motive was a

factor in the means chosen to accomplish that goal,

judicial deference is not required. Thus, the district

court could properly consider whether the extreme

form of preference chosen by Massachusetts had a

bearing on the issue of improper motivation.

5

In some circumstances, the method chosen by the

legislature may be so arbitrary and extreme in effect

as to warrant a finding of discriminatory intent. The

district court determined that Massachusetts’ absolute

preference fell within that category. Whatever the

validity of the district court’s view, it does not apply

to the federal preference.

ARGUMENT

We think it important to point out that neither the

federal, nor any other veterans’ employment prefer

ence, is necessarily implicated with the Massachu

setts scheme. Whatever the decision in this case, it

will not determine the validity of the federal prefer

ence. As discussed in the brief for the United States,

the federal government, acting pursuant to its con

stitutional responsibility to raise and support armies

(Article I, Section 8, clauses 12 and 13), has a

stronger and different interest than the states in

encouraging and rewarding service in the armed

forces— the goals of veterans’ preference. (Brief for

the United States as amicus curiae [hereafter U.S.

Brief] at 34-35). The Court recognized in Hampton

v. Mow Sun Wong, 426 U.S. 88, 100 (1976), that

“ there may be overriding national interests which

justify selective federal legislation that would be un

acceptable for an individual State.” Thus, in Hamp

ton, the Court held that a challenged regulation

excluding aliens from federal competitive civil serv

ice jobs required independent evaluation, even though

the Court had earlier held a similar state provision

6

unconstitutional in Sugarman v. Dougall, 413 U.S.

634 (1973). See also Mathews v. Diaz, 426 U.S. 67

(1976) (unholding a federal statute which denied cer

tain medicare benefits to aliens after striking a com

parable state provision); cf. Morton v. Mancari, 417

U.S. 535, 555 (1974) (holding that Congress’ “ unique

obligation” toward Indians justified an employment

preference for Indians in the Bureau of Indian A f

fairs). Similarly, the compelling national interest in

compensating veterans, which is different both in

quality and character from that of Massachusetts,

would in our view support the federal preference

regardless of the decision here.

Not only are the governmental interests in vet

erans’ legislation different, but the Massachusetts

statute and the federal statute are also substantially

different in their operation and impact. For the most

part, the federal program relies on a point preference,

thereby giving veterans some advantage over non-

veterans who receive the same raw score on a civil

service entrance examination. The Massachusetts

statute, on the other hand, establishes an absolute

preference, granting veterans priority over all other

job applicants regardless of their comparative scores.2

2 Although Congress has given disabled veterans first prior

ity to certain jobs (5 U.S.C. 3313), and restricted certain

unskilled jobs— those of guards, elevator operators, mes

sengers and custodians—to veterans, if any apply (5 U.S.C.

3310; see U.S. Brief at 4 ), these preferences are limited in

scope and justified by special considerations. The plight of

disabled veterans and the nation’s heightened obligation to

7

While there is no question that both statutes have a

disparate impact on women (U.S. Brief at 6, 35),

the federal statute has a less severe effect on women’s

opportunities for obtaining higher level positions.

The district court found that the negative impact of

the Massachusetts absolute preference on women is

“ dramatic” : “ [f]ew, if any, females have ever been

considered for the higher positions in the state civil

service” (A. 217, 218). Although 43 percent of those

hired by the state from 1963 to 1973 were women, a

large percentage of these were employed in lower

paying, traditionally female jobs for which men did

not apply or they were appointed under a defunct

practice allowing requisition of only women for cer

tain jobs (A. 197, 218, 263). The effect of the abso

lute preference is demonstrated in the 1975 Adminis

trative Assistant eligibility list, which served as a

pool for many state positions. As a result of the

veterans’ preference, the 41 women on the list lost

an average of 21.5 places each while the 63 male

veterans gained an average of 28 places each (A.

217). The district court found that “ [ i ] f the list

had ben compiled without the Veterans’ Preference,

nearly 40% of the women would have occupied the

top third of the list which is now occupied, with one

them warrant their special status. As to the few unskilled

jobs for which veterans are given priority, it is reasonable to

presume that veterans applying for such unskilled jobs are

more in need of assistance.

8

exception [a female veteran], by men” (A. 217-18).3 * * * * * * 10

Thus, as Judge Campbell recognized in his concurring

opinion on remand, the absolute preference “ makes it

virtually impossible for a woman, no matter how

talented, to obtain a state job that is also of interest

to males. Such a system is fundamentally different

from the conferring upon veterans of financial bene

fits to which all taxpayers contribute, or from the

giving to them of some degree of preference in gov

ernment employment, as under a point system, as a

quid pro quo for time lost in military service” (A.

268-69).

Studies done by the U.S. Civil Service Commission

indicate that the federal point preference is sig

nificantly less burdensome on women seeking higher

level jobs. The “ primary entry route” into profes

sional and management level federal jobs is the pro

fessional and administrative career examination

(PACE). Veterans’ Preference Oversight Hearings,

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Civil Service of

the House Committee on Post Office and Civil Service,

3 In his first dissent, Judge Murray noted that under the

federal preference the first woman would have ranked 18th on

the eligibility list and plaintiff would not have been reached

until at least 31 names were certified. (A. 240 n.14). How

ever, he incorrectly concluded that these women would not

have been considered for a position by overlooking the fact

that 43 positions held by provisional appointees could have

been filled from the list (A. 77-78). See Brief for Appellee at

10 n.13. This demonstrates that, as the number of vacancies

increases, women have a greater chance of being considered

under the federal system. Therefore, the impact on women of

the federal point preference is much less predictable than

Massachusetts’ absolute preference.

9

95th Cong., 1st Sess. 4 (1977) (Statement of Alan K.

Campbell, Chairman, U.S. Civil Service Commission).

Of those who passed the examination in 1975, 41

percent were female, 37 percent were male non-

veterans, and approximately 20 percent were vet

erans. Of those who were selected for employment,

women constituted 27 percent and veterans 34 per

cent. Therefore, veterans improved and women cor

respondingly declined in position by 14 percent after

addition of the veterans’ preference. Ibid*

At present, selection of employees is made from

those persons who score within the top five percent.

After the veterans’ preference and “ top-of-the-regis-

ter” provisions 5 are considered, women make up 29

percent of those in the top 5 percent. It has been

estimated that without the preference provisions, they

would constitute 41 percent of the top group— an

increase of 12 percent, Statement of Chairman

Campbell, Veterans’ Preference Oversight Hearings,

supra, at 4.5 Thus, while the federal veterans’ prefer- 4 5 6

4 Although the veterans’ preference provisions should also

operate to disadvantage^male nonveterans, they are in fact

hired in numbers comparable to their share of those who pass

the exam. Statement of Chairman Campbell, Veterans’ Pref

erence Oversight Hearings, swpra, at 4.

5 5 U.S.C. 3313 requires that disabled veterans be placed

at the top of the eligibility list for certain jobs. See note 2,

supra. Selection for a position must be made from among the

three available persons highest on the eligibility list. 5 U.S.C.

3318(a).

6 The effect of the federal veterans’ preference turns in

part on economic conditions. Thus, the adverse impact on

women is magnified at the present time because of large

numbers of applicants and few vacancies.

10

ence has an adverse impact on women’s job oppor

tunities, women are not completely foreclosed from

consideration and indeed constituted more than one-

fourth of those hired in 1975 for jobs requiring pro

fessional or administrative skills.7

As the foregoing discussion indicates, the Massa

chusetts statute, by creating an absolute life-long

preference throughout the civil service system, is one

of the most extreme veterans’ preference provisions.

See Fleming & Shanor, Veterans’ Preferences in Pub

lic Employment: Unconstitutional Gender Discrimi

nation?, 26 Emory L.J. 13, 16-18 (1977); see also

Veterans’ Preference Oversight Hearings, supra, at

10-12. The federal point preference, which, insures

some measure of individual competition, is consider

ably less drastic. Indeed, the district court found

that the existence of such effective less discriminatory

alternatives 8 supported its first conclusion that the

7 Despite this hiring ratio, women in federal employment,

as in the private labor force, remain clustered at the bottom

pay scales. Statement of Chairman Campbell, Veterans’

Preference Oversight Hearings, supra, at 4. Cf. Brief Amici

Curiae of the National Organization for Women, et al., at 4

n.l. This, of course, is attributable only in part to the vet

erans’ preference. Surveys by the Civil Service Commission

and the General Accounting Office indicate that a revision of

the preference would have a favorable impact on women in

some circumstances, but not others, depending on their occu

pation. Statement of Chairman Campbell, Veterans’ Prefer

ence Oversight Hearings, supra, at 4-5.

8 Although the degree of preference in the federal system is

less, the federal program is considered highly successful and

effective in meeting the goals set by the federal government,

which has the primary responsibility for compensating vet

11

absolute preference could not withstand constitutional

scrutiny (A. 219-20) and its conclusion on remand

that the statute was intentionally discriminatory (A.

265).

As the Solicitor General has stated, the extent and

form of veterans’ benefits is a matter for Congress

and the state legislatures (U.S. Brief at 36-37).

This is not to say, however, that any veterans’ pref

erence, no matter how extreme or irrational, must

survive constitutional challenge.9 There is no ques

tion that the ultimate purpose of the Massachusetts

statute and other veterans’ preference legislation— to

reward veterans— is legitimate. Even though legis

lation serves a legitimate purpose, however, an illicit

erans. See Veterans’ Preference Oversight Hearings, supra,

at 3. Veterans constitute approximately 50 percent o f the

federal service, while they make up only 25 percent of the

national labor force. Ibid.

9 We do not believe that an employment preference is indis

tinguishable from other forms of veterans’ benefits, such as

educational benefits and loan programs, which are paid out of

general tax revenues. Although an individual’s interest in

obtaining public employment is not fundamental, Massachu

setts Board of Retirement v. Murgia, 427 U.S. 307 (1976), it

is considered significant. See, e.g., Board of Regents v. Roth,

408 U.S. 564 (1972) ; Blumberg, De Facto and De Jure Sex

Discrimination under the Equal Protection Clause: A Recon

sideration of the Veterans’ Preference in Public Employment,

26 Buffalo L. Rev. 3, 68-69 (1977). Moreover, the veterans’

employment preference, unlike forms of financial benefits,

places a particular burden on women seeking the opportunity

for employment. Cf. Nashville Gas Co. v. Satty, 434 U.S, 136,

142 (1977) (distinguishing between a policy placing a burden

on employment opportunities and one which merely denies

women additional financial benefits).

12

motive may nevertheless have been a factor in the

choice of means adopted to accomplish that goal. As

the Court explained in Village of Arlington Heights

v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S.

252, 265 (1977), “ [rjarely can it be said that a legis

lature or administrative body operating under a

broad mandate made a decision motivated solely by

a single concern * * * When there is a proof that a

discriminatory purpose has been a motivating factor

in the decision * * * judicial deference is no longer

justified.” [Footnote omitted.] The statement in the

brief for the United States that “when the district

court found that the purpose of the veterans’ prefer

ence statute was to aid veterans and not to injure

women, that should have been the end of the matter”

(U.S. Brief at 31-32), should be read in context: it

was based both on the district court’s finding that the

prime objective of the Massachusetts statute was

worthy (A. 254, 264) and also on the statement in its

first opinion that the statue “was not enacted for the

purpose of disqualifying women from receiving civil

service appointments” (A. 212). However, the latter

conclusion was made before the decision in Washing

ton v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976), at a time when the

court believed that a disproportionate impact alone

was sufficient to require heightened scrutiny. It was

not a considered finding on the complex question of

illicit motivation. See Comment, Veterans’ Public

Employment Preference as Sex Discrimination, 90

Harv. L. Rev. 805, 810 n.45 (1977). Therefore, we

do not believe that the brief of the United States is

13

contrary to our position that the district court could

properly consider whether the extreme form of pref

erence chosen by Massachusetts had a bearing on the

issue of improper motivation (see U.S. Brief at

28-30).10 It is also significant that the Massachusetts

statute is unlike other facially neutral laws because

it directly incorporates the military’s explicit gender-

based classifications. That the discriminatory impact

is therefore both foreseeable and “ inevitable” (A.

260 n.7) does not in our view warrant heightened

scrutiny of the statute, but it is a factor to be con

sidered in determining the legislature’s motivation.

As stated in the brief for the United States, insofar

as the district court conclusively presumed a discrimi

natory purpose from the legislature’s awareness of

predictable disparate impact on women, it was in

error (U.S. Brief at 18-19, 26). Foreseeable dis

criminatory effect is, however, probative evidence of

a discriminatory purpose and in some contexts per

mits an inference of discriminatory intent, which

shifts the burden of rebuttal to the state (U.S. Brief

at 28-29). We believe that the degree of reasonable

ness in the legislature’s choice of means is probative

10 The Court noted in Village of Arlington Heights, supra,

429 U.S. at 265 n .ll, that “ ‘ [1]egislation is frequently multi-

purposed: the removal of even a “ subordinate” purpose may

shift altogether the consensus of legislative judgment support

ing the statute’ ” (quoting McGinnis V. Royster, 410 U.S. 263,

276-77 (1973)). See also Brest, Palmer v. Thompson: An

Approach to the Problem of Unconstitutional Legislative Mo

tive, 1971 Sup. Ct. Rev. 95, 104 (“ Every explicit or implicit

distinction made by a law may have objectives.” ).

14

of intent, as is the existence of effective less discrimi

natory alternatives.11 There is a point where the

method chosen by the legislature is so arbitrary and

extreme in effect as to warrant a finding of invidious

intent. See Washington v. Davis, supra, 426 U.S.

at 241-242 and 254 (Stevens, J., concurring); Gomil-

lion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) (an extreme

example in which the boundaries of Tuskegee were

changed from a square to a twenty-eight-sided figure,

excluding virtually all black voters). The district

court concluded that Massachusetts’ absolute perma

nent preference reached that point. Whatever the

validity of the district court’s view, we emphasize

that, as discussed above, the decision does not require

a finding that Congress was similarly motivated.12

11 Professor Brest explains: “ A conscientious decisionmaker

* * * considers the costs of a proposal, its conduciveness to the

ends sought to be attained, and the availability of alternatives

less costly to the community as a whole or to a particular

segment of the community. That a decision obviously fails to

reflect these considerations with respect to any legitimate

objective supports the inference that it was improperly moti

vated.” Brest, Palmer v. Thompson: An Approach to the

Problem of Unconstitutional Legislative Motive, supra, 1971

Sup. Ct. Rev. at 121-122. See also Note, Reading the Mind of

the School Board: Segregative Intent and the De Facto/De

Jure Distinction, 86 Yale L. J. 317, 337-340 (1976). Cf. Albe

marle Paper Co. V. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 425 (1975) (ex

istence of an effective less discriminatory alternative is evi

dence that more burdensome means were chosen as a “ pre

text” for discrimination).

12 The district court specifically noted that it was not passing

on the validity of the federal provisions (A. 220).

15

Respectfully submitted.

Margery W axman

General Counsel

Office of Personnel Management

Deanne Siemer

General Counsel

Department of Defense

Carin A nn Clauss

Solicitor of Labor

Department of Labor

Issie L. Jenkins

Acting General Counsel

Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission

February 1979

i t U. S . GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1 9 7 9 2 8 6 6 5 8 3 2 2