Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief Amicus Curiae Landmark Legal Foundation Center

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oklahoma City Public Schools Board of Education v. Dowell Brief Amicus Curiae Landmark Legal Foundation Center, 1989. 16a7402d-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e14a1bfa-e950-4bd5-aac7-71e21ec8a7a8/oklahoma-city-public-schools-board-of-education-v-dowell-brief-amicus-curiae-landmark-legal-foundation-center. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

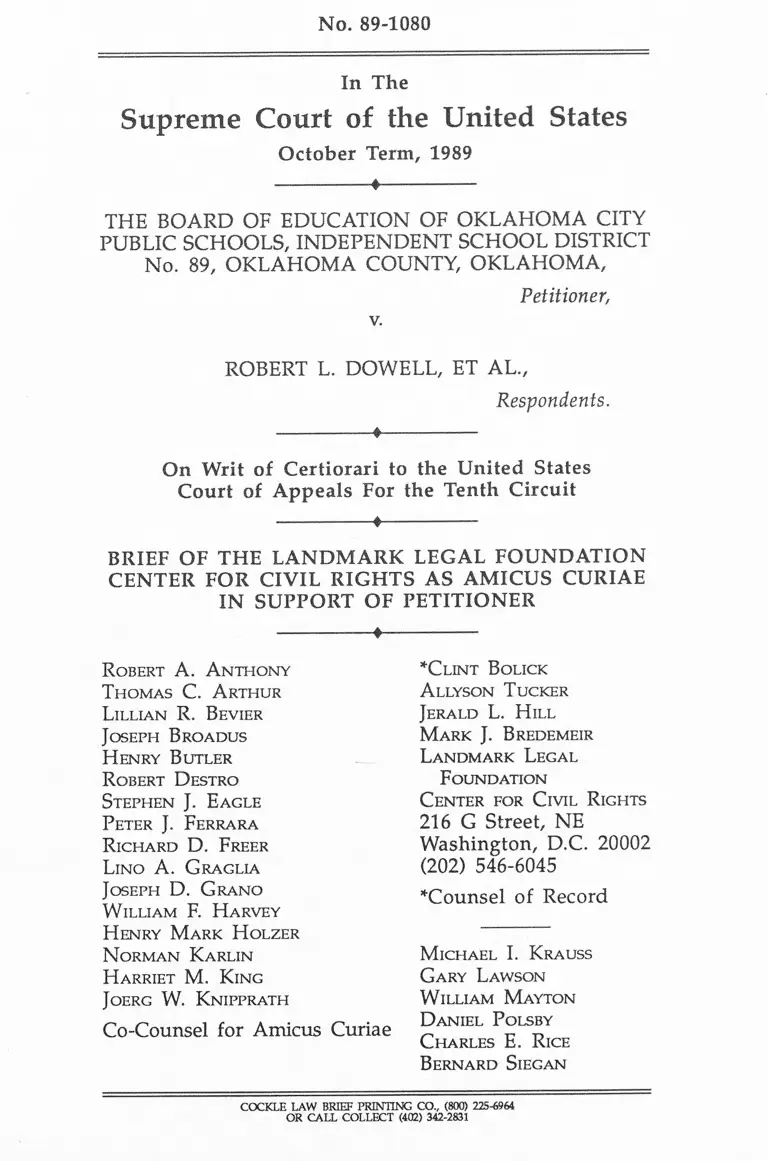

No. 89-1080

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1989

--------------- «---------------

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF OKLAHOMA CITY

PUBLIC SCHOOLS, INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT

No. 89, OKLAHOMA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA,

Petitioner,

v.

ROBERT L. DOWELL, ET AL.,

Respondents.

--------------- «---------------

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals For the Tenth Circuit

--------------- *---------------

BRIEF OF THE LANDMARK LEGAL FOUNDATION

CENTER FOR CIVIL RIGHTS AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

--------------- «---------------

R o bert A. A n th o n y

T h o m as C . A rthur

L illia n R . B evier

J oseph B ro a d u s

H enry B u tler

R o bert D estro

S teph en J . E a gle

P eter J . F erra ra

R ich a rd D . F reer

L ino A . G ra glia

J oseph D . G rano

W illia m F. H a rvey

H enry M a r k H o lzer

N o rm a n K a rlin

H a r riet M . K ing

JOERG W . KNIPPRATH

Co-Counsel for Amicus Curiae

*C lent B o lick

A llyson T ucker

J era ld L . H ill

M a rk J. B redem eir

L a n d m a rk L eg a l

F oundation

C en ter for C ivil R ights

216 G Street, NE

Washington, D.C. 20002

(202) 546-6045

’•'Counsel of Record

M ichael I. K rauss

G ary L awson

W illiam M ayton

D a n iel P o lsby

C h a rles E . R ice

B ern a rd S iegan

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

1

Table of Authorities............................................ ii

Interest of Amicus Curiae............................................ 1

Summary of Argument ........................... 2

Argument.................................................................... 4

I. THE REMEDIAL AUTHORITY OF THE COURTS

MUST END WHEN A SCHOOL DISTRICT AS

SURES THAT EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES

ARE AVAILABLE TO ALL ON EQUAL TERMS... 4

II. EXPERIENCE DEMONSTRATES THAT LONG

TERM COERCIVE MEASURES DESIGNED TO

MAINTAIN RACIAL BALANCE ARE INCON

SISTENT WITH THE OBJECTIVE OF EQUAL

EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES...................... 10

A. White flight............................................................ 11

B. Black flight and the burden of busing on

blacks............................................................. 13

C. Effects on educational achievement.............. 15

D. Availability of sound educational alterna

tives ................................................................. 17

E. A unitary school district reasonably may

consider these factors in determining educa

tional policies........................................ 19

CONCLUSION ............................................. 21

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

11

C a ses :

Brown v. Board of Educ. of Topeka, 892 F.2d 851 (10th

Cir. 1989) petition for cert, filed, No. 89-1681 .. 2, 4, 19

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Morgan v. Nucci, 831 F.2d (1st Cir. 1987) . . . . . . . . 4, 6, 9

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424 (1976).................... ......................................... 5, 8

Riddick v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 784 F.2d 521

(4th Cir.), cert, denied, 479 U.S. 938 (1986).......... 5, 9, 12

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971)............................... ............................5, 8

United States v. Overton, 824 F.2d 1171 (5th Cir.

1 9 8 7 ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ............................................. 6, 8, 9, 10

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado, 895

F.2d 659 (10th Cir. 1990), petition for cert, filed,

No. 89-1698 ....................................... ............. 2, 13, 14, 15

Pitts v. Freeman, 887 F.2d 1438 (10th Cir. 1989),

petition for cert, filed, No. 89-1290 ................................ 2

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

A rttct.es a n d B o o k s :

Alves and Willie, "Controlled Choice Assignment:

A New and More Effective Approach to School

Desegregation," 19 Urban Review (1987)......... . .18, 19

Armor, "After Busing: Education and Choice,"

Current (October 1989).................................................... 18

Armor, "School Busing," in Katz and Taylor, eds.,

Eliminating Racism (1988)............................................... 12

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Ascik, "An Investigation of School Desegregation

and Its Effects on Black Student Achievement,"

American Education (December 1984)................. .. 16

Bennett, "A Plan for Increasing Educational Op

portunities and Improving Racial Balance in

Milwaukee," in Willie and Greenblatt, School

Desegregation Plans That Work (1984)......................... 18

Bolick, C , Changing Course: Civil Rights at the

Crossroads (1988)................................................................ 15

Committee on the Status of Black Americans, A

Common Destiny (1989)..................................................... 16

Cuddy, "A Proposal to Achieve Desegregation

Through Free Choice," American Education (May

1983).................................................... ..........................14, 18

Graglia, L. Disaster by Decree (1976)..................... .. 15

Jennings, "Studies Link Parental Involvement,

Higher Student Achievement," Education Week,

(April 4, 1990)................. 14

National Institute of Education, School Desegrega

tion and Black Achievement (1984)....................... 13

Pride, R. and J. Woodard, The Burden of Busing

(1985)............................... ................................ 3, 12, 13, 14

Raspberry, "The Easy Answer: Busing," Washing

ton Post (Apr. 20, 1985).................................................. 10

Snider, William, "Voucher System For 1,000 Pupils

Adopted in Wisconsin," Education Week (March

28, 1990) ......................................... 18

Yarmolinsky, A., L. Liebman, and C. Schelling,

eds., Race and Schooling in the City (1981)......... 17

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

S tatutes a n d R u les :

Wise. St at. § 119.23 (1990)................................. 18

No. 89-1080

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1989

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF OKLAHOMA CITY

PUBLIC SCHOOLS, INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT

No. 89, OKLAHOMA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA,

Petitioner,

v.

ROBERT L. DOWELL, ET AL„

Respondents.

- ----------------------------- ♦----------------------- --

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals For the Tenth Circuit

---------------- ♦ ------------ -

BRIEF OF THE LANDMARK LEGAL FOUNDATION

CENTER FOR CIVIL RIGHTS AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER

--------------- *---------------

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Landmark Legal Foundation Center for Civil

Rights is a public interest law center dedicated to promot

ing the core principles of civil rights: equality under law

and individual liberty.

1

2

A vital aspect of this mission is the pursuit of equal

educational opportunities. We represent parents, school-

children, and teachers in a variety of cases raising issues

of equal educational opportunities and educational

choice.

We are joined as co-counsel by a number of distin

guished law professors who share our conviction that the

decision under review in this case is incompatible with

fundamental principles of justice and with sound public

policy.

--------------- #----------------

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

In a very real sense, the appearance of this case and

others like it1 before this Court is a cause for celebration -

specifically, a celebration of the triumph of our nation's

most cherished principles. These cases mark an important

epoch in America's quest to make good on its commit

ment to civil rights, for they present the question not of

how to remedy discriminatory educational systems, but

rather what happens when that task is accomplished.

This case does not require the Court to make new

law, but merely to apply well-established equitable prin

ciples. The dispositive principle in this case is that the

1 The three other cases pending on petitions for writs of

certiorari include Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, Colorado,

895 F.2d 659 (10th Cir. 1990), petition for cert, filed, No. 89-1698;

Brown v. Board of Edue. of Topeka, 892 F.2d 851 (10th Cir. 1989),

petition for cert, filed, No. 89-1681; Pitts v. Freeman, 887 F.2d 1438

(10th Cir. 1989), petition for cert, filed, No. 89-1290.

3

scope of judicial remedies is defined and limited by the

scope of the constitutional violation.

Mandatory busing is harsh medicine even in its lim

ited role as a remedy for egregious violations of constitu

tional rights. However critical the need to employ

extraordinary remedies, just as vital is the necessity to

restrict such measures to extraordinary circumstances.

For coercive measures such as busing that displace com

munity control over education can detract substantially

from the educational mission, to the detriment of the very

youngsters they are intended to benefit. Accordingly,

such measures should seek to spend themselves as quick

ly as possible so as to return discretion to those entrusted

with the high responsibility of educating our children.

As two scholars who have studied extensively the

impact of sustained busing in a community have ob

served, "The politics of race can only end when . . .

people no longer think of themselves in racial terms

above all else, but identify themselves first as parents or

teachers, . . . and only secondarily as black or white. . .

R. Pride and J. Woodard, The Burden of Busing 283 (1985).

The Court can hasten the arrival of that day by limiting

the use of coercive race-based remedies to the most ex

traordinary circumstances, and by allowing communities

that have accomplished the task of desegregation to turn

their attention to the task of pursuing educational objec

tives in a race-neutral fashion.

4

ARGUMENT

I. THE REMEDIAL AUTHORITY OF THE COURTS

MUST END WHEN A SCHOOL DISTRICT AS

SURES THAT EDUCATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES

ARE AVAILABLE TO ALL ON EQUAL TERMS.

At issue here is the question of when, if ever, judicial

supervision of a "unitary" school system ceases. The

Tenth Circuit, in its decision below reversing the contrary

ruling of the district court, departed from well-estab

lished equitable principles when it ruled, in essence, that

formerly segregated school districts must permanently

retain coercive measures designed to maximize racial bal

ance.

The constitutional right at stake in school desegrega

tion cases is "the opportunity of an education . . .

available to all on equal terms." Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954). The vindication of this right

throughout an entire school district represents the attain

ment of "unitary" status - what one court has aptly called

"the 'accomplishment' of desegregation." Morgan v. Nuc-

ci, 831 F.2d 313, 318 (1st Cir. 1987).

This Court has carefully delineated the authority of

courts to engage in remedial action in the desegregation

context. "The controlling principle consistently ex

pounded in our holdings is that the scope of the remedy

is determined by the nature and extent of the constitu

tional violation." Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717, 744

(1974).

The Court has established a number of specific lim

itations to ensure that desegregation decrees are tailored

to the scope of the violation. First, judicial remedies are

5

permissible only upon a finding of causation; racial im

balance cannot justify a race-conscious remedy unless the

"school authorities have in some manner caused uncon

stitutional segregation." Pasadena City Board of Education

v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 434 (1975). Second, coercive race

conscious remedies should play as limited a role as pos

sible in the desegregation process. Thus, this Court has

approved "the very limited use . . . of mathematical

ratios" only as "a starting point in the process of shaping

a remedy, rather than as an inflexible requirement."

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S.

1, 25 (1971). Third, the Court repeatedly has stressed that

the remedial goal is desegregation, not racial balancing.

"The constitutional command to desegregate schools does

not mean that every school in every community must

always reflect the racial composition of the school system

as a whole." Id. at 24. Finally, once the indicia of past

discrimination are removed from a dual school system,

courts are "not entitled" to take further steps "to ensure

that the racial mix desired by the court [is] maintained in

perpetuity." Spangler, 427 U.S. at 436.

Once unitary status is attained, the predicate for

further relief ends. Thereafter, remedial relief is permis

sible only if the school district "deliberately attempts]

to fix or alter demographic patterns to affect the racial

composition of the schools. . . Swann, 402 U.S. at 32;

accord, Spangler, 427 U.S. at 435.

In conformity with these standards, the Fourth Cir

cuit has held that once the underlying violation is cured,

as reflected by the attainment of unitary status, the trial

court is without authority to make further orders. Riddick

v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 784 F.2d 521, 535 (4th

6

Cir.), cert denied, 479 U.S. 938 (1986), More specifically, the

First Circuit has ruled that unitariness triggers the "man

datory devolution of power to local authorities," Morgan,

831 F.2d at 318 (emphasis in original); and that once the

school district has achieved desegregation goals in any

facet of its school system, the Court may not "perpetuate

an injunction requiring adherence to a particular formu

la" in that area. Id. at 326. The Fifth Circuit likewise has

adopted this approach. United States v. Overton, 824 F.2d

1171 (5th Cir. 1987).

Were Oklahoma City in any other circuit, this case

would not have appeared before this Court in its current

posture. By any reasonable measure, the school district

here has earned the right to pursue its educational mis

sion free from judicial control, precisely the conclusion

reached by the district court in this case.

The Oklahoma City school district was declared uni

tary in 1977, following an evidentiary hearing in which

the district court found that the Finger Plan, a compre

hensive remedial program that included massive cross

town busing, had eliminated all vestiges of state-imposed

racial discrimination (App. 2a). The court entered an

order declaring:

Now sensitized to the constitutional implica

tions of its conduct and with a new awareness of

its responsibility to citizens of all races, the

Board is entitled to pursue in good faith its

legitimate policies without the continuing con

stitutional supervision of this Court. The Court

believes and trusts that never again will the

Board become the instrument and defender of

racial discrimination so corrosive of the human

7

spirit and so plainly forbidden by the Constitu

tion.

Id. At that time, the district court relinquished jurisdic

tion over the case and returned the responsibility for

race-neutral educational decisions to the Board of Educa

tion of the Oklahoma City Public Schools.

For eight years following the unitary declaration, the

Oklahoma City School Board continued to implement the

Finger Plan. In 1984, however, it became apparent that

demographic changes had taken place within the school

district and that the Finger Plan, if continued on the

elementary level, would increase the burden of busing on

young black children in grades K-5 and lead to the clo

sure of a large number of schools in a predominantly

black area of the city. In response, the school board

adopted a Student Reassignment Plan, which was imple

mented for the 1985-86 school year. The plan eliminated

compulsory busing in grades one through four and reas

signed elementary students to their neighborhood

schools, which resulted in the existence of a number of

heavily black schools. The board retained a "majority to

m inority" transfer option which allowed students

assigned to a school in which they were in the majority

race to transfer to a school in which they would be in the

minority. The new plan also appointed an "equity officer"

who, assisted by an equity committee, would monitor all

schools to insure the equality of facilities, equipment,

supplies, books, and instructors (App. 5a).

Although the district court upheld this plan, finding

that it was nondiscriminatory and served valid educa

tional objectives (App. 17-19a), the Tenth Circuit re

versed. Viewing the Finger Plan as a permanent

8

injunction, the court placed the burden on the school

district to demonstrate changed circumstances to justify

modification of the injunction (App. 14a). The court con

cluded that the district failed to carry its burden, in part

because continued residential racial imbalance caused

similar racial imbalance in the schools (App. 19a).

The Tenth Circuit's rule that coercive desegregation

measures are in the nature of a permanent injunction and

modifiable only by a showing of significantly changed

circumstances amounts to a radical departure from deseg

regation jurisprudence. By sanctioning a remedy virtually

without end, the Tenth Circuit's rule, by definition, far

exceeds remedial authority as limited by the scope of the

constitutional violation. As the Fifth Circuit has observed,

the "difficulty with Dowell's approach is that it denies

meaning to unitariness by failing even to end judicial

superintendence of schools." Overton, 824 F.2d at 1175.

The Tenth Circuit's rule upsets as well the specific

boundaries of permissible judicial action established by

this Court. Its requirement of permanent adherence to

racial ratios confuses the constitutional right to equal

educational opportunities with the objective of racial bal

ance, an approach this Court has warned "would be

disapproved and [which] we would be obliged to re

verse." Swann, 402 U.S. at 24. It seeks to hold the school

district responsible for residential racial imbalance de

spite the absence of any showing that it is "in any manner

caused by segregative actions chargeable" to the district.

Spangler, 427 U.S. at 435. In sum, the Tenth Circuit's

imposition of extraordinary remedial measures long after

the wrong has been righted amounts to "a heady call for

raw judicial power." Overton, 834 F.2d at 1176.

9

The Tenth Circuit attempts to rationalize its sweeping

departure from well-established remedial principles by

invoking the procedural cover of a permanent injunction.

A court may not, however, evade limitations on its power

by emphasizing form over substance. As the other cir

cuits that have considered this issue have concluded,

affirmative relief is no longer warranted - or authorized -

when unitary status is achieved. See e.g., Morgan, Riddick,

and Overton, supra. To state it in the vernacular of an

injunction, the "changed circumstance" justifying the ter

mination of injunctive relief is unitary status; and a sig

nificant change it is, for it means that the dual system of

education no longer exits.

In a very real sense, school districts that have at

tained unitary status do operate under a permanent in

junction: the constitutional command of nondiscrimi

nation. Any individual is free to challenge school district

policies as intentionally discriminatory. This prospect

provides a sufficient safeguard to ensure that school dis

trict will not once again adopt discriminatory practices,

and to ensure swift and meaningful relief if they do. In

sum, the rule this Court should ratify is that the only

choice denied to a unitary school district is the choice to

discriminate.

The necessity of removing the scarlet "S" from school

districts that have accomplished the difficult task of

achieving a unitary educational system is supported as

well by the societal interest in encouraging districts to

undertake such efforts. As the Fifth Circuit has remarked,

"The carrot of unitariness can be a meaningful incentive

for school districts to desegregate only if we abide by our

promise to release federal control once the job is done."

10

Overton, 834 F.2d at 1176. For Oklahoma City, which has

successfully travelled the road to unitary status, the time

has come for the court to return to the community the

power to act in the best educational interests of its chil

dren.

II. EXPERIENCE DEMONSTRATES THAT LONG

TERM COERCIVE MEASURES DESIGNED TO

MAINTAIN RACIAL BALANCE ARE INCONSIS

TENT WITH THE OBJECTIVE OF EQUAL EDU

CATIONAL OPPORTUNITIES.

Equitable principles do not develop in a vacuum.

They reflect centuries of acquired wisdom and experience

with respect to the appropriate nature and extent of judi

cial interventions in personal disputes and societal ills.

Departures from these principles thus can produce unex

pected and tumultuous consequences. This risk is no

where more pronounced than in the context of school

desegregation, which affects directly the lives and oppor

tunities of our nation's most precious resource: its chil

dren.

A growing consensus is developing among scholars,

education officials, and parents that forced busing de

tracts from the educational mission. Though strongly

committed to equal opportunities for all youngsters,

many thoughtful individuals have concluded that such

opportunities are not optimally served by measures that,

in the words of columnist William Raspberry are "almost

monomaniacally concerned with the maximum feasible

mixing of races, with educational concerns a distant sec

ond." Raspberry, "The Easy Answer: Busing," Washington

Post, Apr. 20,1985, at A23. A number of factors associated

11

with busing contribute to these concerns, among them the

phenomenon of "white flight," the cost and disruption of

busing, and the availability of sound educational alterna

tives. We express no opinion on the salience of these

factors in any given situation; we are attorneys, not social

scientists. Our point is simply this: once a school district

has purged itself of a segregated school system, it should

once again have the discretion to act in the best educa

tional interests of its children.

In this case, the Oklahoma City School District deter

mined that the burden of busing borne by young black

students was too great. It concluded that neighborhood

schools - enhanced by an "effective schools" program

and combined with the opportunity to transfer - would

improve educational opportunities for these youngsters.

The notion that this policy reflected a return to a dual

system was rejected by the district court as "ludicrous

and absurd" (App. 44b).

Under these circumstances, this conclusion is cer

tainly unremarkable. What is remarkable, however, is the

Tenth Circuit's insistence on adherence to racial balance

as the permanent touchstone of a unitary school system's

educational policies. As we show below, numerous legiti

mate justifications exist for school districts to pursue

objectives other than racial balance. Indeed, a judicial

rule that prohibits or discourages alternatives may harm

most severely those who are the intended beneficiaries of

desegregation.

A. White Flight. A major problem endemic to man

datory busing plans is white flight - the loss of middle-

class white students who move away or enroll in private

12

schools. See e.g., Riddick, supra (approving school system's

return to neighborhood schools due in part to white

flight). The deleterious impacts of white flight are felt

most strongly by the black youngsters left behind.

Most studies on white flight "concur that larger, cen

tral-city school districts with sizable minority enrollments

experience significant long-term white flight following

mandatory busing plans." D. Armor, "School Busing," in

Katz and Taylor, eds., Eliminating Racism 266 (1988).

White flight today appears to be caused more by educa

tional concerns than by racism: in Los Angeles, where

busing resulted in massive white flight, rates of white

withdrawal were essentially unchanged regardless of

whether the new assigned schools were predominantly

white, black, or Hispanic. Id. at 269.

White flight is harmful primarily in two ways. First,

it frustrates the objectives of desegregation. Although

"mandatory [busing] plans do the best job of producing

racial balance," observes social scientist David J. Armor,

they do so "usually only at the cost of converting all

schools to predominantly minority status." Id. at 270-271.

Thus, "mandatory busing has aggravated the growing

racial isolation" of many cities. Id. at 271.

A second consequence of white flight is the loss of

vital community support for public schools. In their

study of the impact of long-term busing in Nashville,

Richard A. Pride and J. David Woodard found that white

flight

was a significant and continuing problem. . . .

Traditionally, the white middle class had been

the public schools' strongest ally; its members

13

had supported the schools politically, finan

cially, and, through countless hours of volunteer

labor, personally. Without their strong support,

the public schools could slip into mediocrity or

worse.

Pride and Woodard at 141. An overwhelming majority of

whites and a large plurality of blacks in Nashville ex

pressed the view2 that community support would return

following a restoration of neighborhood schools. Id. at

153.

Given the reality of white flight, a school board could

reasonably conclude that mandatory busing thwarts ef

fective desegregation and reduces prospects for quality

schooling, particularly for poor youngsters. Unitary

school districts therefore should have discretion to deal

with such problems.

B. Black Flight and the Burden of Busing on

Blacks. Justice Powell observed that "[a]ny child, white

or black, who is compelled to leave his neighborhood and

spend significant time each day being transported to a

distant school, suffers an impairment of his liberty and

privacy." Keyes, 413 U.S. at 247-248 (Powell, J., concurring

in part and dissenting in part). Black children, in particu

lar, "for years have borne the heaviest personal cost of

desegregation by enduring long bus rides, separation

from familiar surroundings, and curtailment of extracur

ricular activities." National Institute of Education, School

2 Surveys were taken on various educational issues in

Nashville between 1977-1981 after several years of court-im

posed busing.

14

Desegregation and Black Achievement 43 (1984) [henceforth

"NIE Study"].

Moreover, "abandonment of neighborhood schools

tends to limit parental participation in, and supervision

of, the operation of the school system and lessens the

importance of the school as a center of community con

cern and cohesion." Keyes, 413 U.S. at 246 (Powell, J.).

This diminished parental involvement is potentially dev

astating to black educational achievement, since studies

show a strong correlation between parental involvement

and higher student grades and test scores, positive stu

dent attitudes and behaviors, and improved school

atmospheres. Jennings, "Studies Link Parental Involve

ment, Higher Student Achievement," Education Week,

April 4, 1990, at 20.

Little wonder then that black parents are growing

increasingly skeptical about busing. As Pride and Wood

ard found in Nashville, "adults of both races believe that

busing is unfair," but such feelings "may be especially

acute among blacks, the very group the policy was de

signed to help." Id. at 284. Surveys in Nashville revealed

that 58% of black parents believed busing was harmful to

the educational development of white and/or black

school children, id. at 151; and that 38% of black parents

would enroll their children in private schools if they

could afford to do so. Id. at 153. A study in Boston found

that 75% of black parents involved in busing would pre

fer their children attend neighborhood schools of equal

quality. Cuddy, "A Proposal to Achieve Desegregation

Through Free Choice," American Education, May 1983, at

28-29.

15

Understandably, a sizable "black flight" away from

inner-city public schools has taken place in many cities.

Fully half the students in urban private schools (includ

ing Catholic schools) are black, and another third are

Hispanic. Moreover, half of urban private schools fami

lies are low-income. See C. Bolick, Changing Course: Civil

Rights at the Crossroads 108 (1988). In many private

schools, "low socioeconomic status minority youth are

scoring above the national average on standardized

tests." Cuddy at 26. Busing appears both a cause of the

desire of many black families to seek alternatives, as well

as an impediment to school districts in responding to

those desires.

The disproportionate burden of busing shouldered

by black youngsters thus provides a legitimate basis for

educational decisionmakers to reject racial balance poli

cies in favor of those that expand choices or improve

educational quality.

C. Effects on Education Achievement: Although

busing is costly in many ways,3 it provides few, if any,

offsetting educational benefits, particularly for its intend

ed beneficiaries. Despite nearly three decades of forced

busing, "there remains a persistent and large gap" be

tween black and white students in achievement test

scores, high school dropout rates, and college attendance

3 As Justice Powell remarked, "At a time when public

education is suffering serious financial malnutrition, the eco

nomic burdens of [busing] may be severe, requiring both initial

capital outlays and annual operating costs in the millions of

dollars." Keyes, 413 U.S. at 248 (Powell, J.). See also L. Graglia,

Disaster by Decree 264 (1976).

16

and completion rates. Committee on the Status of Black

Americans, A Common Destiny 378 (1989). The "assump

tion that integration would improve achievement of low

er class black children has now been shown to be fiction,"

according to James Coleman, whose 1966 study was cited

by many advocates of busing. See Cuddy at 26.

The NIE Study on desegregation and black achieve

ment,4 which produced "the most comprehensive and in-

depth treatment of the issue ever," reached "a definitive

conclusion: desegregation has small positive effects on

black student achievement in reading and no effects on

black achievement in math." See Ascik at 19. Even more

to the point, academic gains took place in school districts

with voluntary desegregation programs, while those with

mandatory plans reported either no gains or actual losses

in black student achievement. NIE study at 26. Other

studies have found that black students' educational and

occupational aspirations remained equal or fell below

those of whites following desegregation, and that blacks

in non-integrated schools have higher self-esteem than

blacks in integrated schools. See Committee on the Status

of Black Americans at 373-374.

4 The NIE study was conceived as "a way to reconcile the

disagreements" among social scientists on this issue. The study

was conducted by seven distinguished social scientists who

previously had reached divergent findings. The study pro

duced "remarkable convergence about the fundamental ques

tion." See Ascik, "An Investigation of School Desegregation

and Its Effects on Black Student Achievement," American Edu

cation, December 1984, at 17.

17

As David Armor has concluded, these findings raise

serious questions about compulsory desegrega

tion methods such as mandatory busing. There

is little justification for forcing . . . children into

expensive, time-consuming cross-town bus rides

when there is no educational advantage. . . . It

should be made clear to all . . . that simply

changing to schools that are more racially bal

anced than one's neighborhood school is no

guarantee of a superior education. Indeed, they

may be giving up possible advantages of special

programs in their own school — programs de

signed specifically to enhance education and

proven to work.

NIE Study at 60-61. The overwhelming weight of the data

thus suggests that policies designed primarily to promote

racial balance do nothing to promote - and may in fact

inhibit - efforts to improve educational quality.

D. Availability of Sound Educational Alternatives.

The failure of forced busing has prompted many advo

cates of expanded educational opportunities for blacks to

call for a different approach. Derrick Bell, among others,

has called for "educationally oriented relief" for past

racial discrimination that embraces policies that provide

"real opportunities for blacks without the cost and dis

ruption of busing." Bell, "Civil Rights Commitment and

the Challenge of Changing Conditions in Urban School

Cases," in A. Yarmolinsky, L. Liebman, and C. Schelling,

eds., Race and Schooling in the City 201 (1981).

Essential elements of successful programs for disad

vantaged minority students include school leadership,

parental participation, and teacher accountability. Id. Pol

icies geared to improved quality of instruction, classroom

18

morale, and stimulation in the home environment, con

cludes Herbert }. Walberg, are far preferable to racial

balancing, which "does not appear promising in the size

or consistency of its effects on learning of Black stu

dents." NIE Study at 187.

What now appears clear is that neighborhood schools

can provide high-quality educational opportunities even

if they are not racially balanced. See, e.g., Bell at 201.

Moreover, a number of wide-ranging reforms offer signif

icant potential for improving educational quality and ex

panding opportunities, such as magnet schools,5

"controlled choice,"6 district-wide open enrollment with

transportation,7 metropolitan area-wide or statewide

open enrollment, and vouchers.8 The State of Wisconsin

recently adopted a voucher program for Milwaukee's

most economically disadvantaged students, providing

free choice among nonsectarian private schools.9 Alterna

tives like these demonstrate that school officials acting in

good faith have a wide variety of options at their disposal

5 See, e.g. Bennett, "A Plan for Increasing Educational Op

portunities and Improving Racial Balance in Milwaukee," in

Willie and Greenblatt, School Desegregation Plans That Work 81

(1984).

6 See, e.g. Alves and Willie, "Controlled Choice Assign

ment: A New and More Effective Approach to School Deseg

regation," 19 Urban Review 67 (1987).

7 See, e.g. Cuddy, supra.

8 Armor, "After Busing: Education and Choice," Current,

October 1989, at 18-20.

9 Wise. Stat. § 119,23 (1990); see also William Snider,

"Voucher System For 1,000 Pupils Adopted in Wisconsin,"

Education Week, March 28, 1990.

19

to make "the opportunity of an education . . . available to

all on equal terms." Brown, 347 U.S. at 493.

E. A Unitary School District Reasonably May Con

sider These Factors in Determining Educational Poli

cies. The sum of the evidence strongly suggests that

"plans that mandatorily assign students to schools out

side of their immediate neighborhoods tend to destabilize

over time and have no inherent educational value." Alves

and Willie at 70. Policymakers legitimately may respond

to this evidence in any number of ways; what is essential

is that they have the discretion to do so. If unitary status

means anything, these real-world considerations compel

it to mean that school districts once again may turn their

primary focus toward educational objectives rather than

racial balance.

These are precisely the type of factors the Oklahoma

City school board took into account when it adopted its

revised plan. The district considered the desirability of

parental and community involvement that a partial re

turn to neighborhood schools would produce (App.

26b-28b). It considered the burden that would be borne

primarily by black students in continuing a forced busing

plan at the first-through-fourth grade levels (App. 7a). In

returning to neighborhood schools at these grade levels,

the district provided to parents the option to exercise

"majority to minority" transfers (App. 4a-5a). The district

also has operated an "effective schools" program that has

"resulted in overall academic gains at 8 of the 10 predom

inantly black elementary schools exceeding the average

gains made by black children nationally," placing the

school district "well on its way to becoming a nationally

recognized model urban school district" (App. 43a). All

20

of these factors convinced the district court that no fur

ther coercive measures were necessary.

Given its sustained and successful efforts in eradicat

ing its prior dual educational system, an order prohibit

ing Oklahoma City from acting in ways that are

demonstrably in the best educational interests of its

schoolchildren turns the notion of equity on its head.

Bigots no longer control the Oklahoma City schools; peo

ple who have demonstrated their commitment to equal

educational opportunities do. The time has arrived for

courts to recognize that in some places, like Oklahoma

City, times have changed.

The critical flaw of the Tenth Circuit's decision in this

case is that it lost sight of the fact that schoolchildren are

the intended beneficiaries of school desegregation, and

that their protected right is equal educational opportunity.

That right is subverted by a judicial rule that makes racial

balance rather than educational opportunities the perma

nent primary governing principle in a school system.

4-

21

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, we urge this Court to

reverse the decision of the Tenth Circuit.10

Respectfully submitted,

R o bert A . A n th o n y

T h o m a s C . A rth u r

L illia n R . B evier

J o seph B ro a du s

H enry B u tler

R o bert D estro

S teph en J . E a g le

P eter J . F erra ra

R ich a rd D . F reer

L in o A . G raglia

J oseph D . G ra n o

W illia m E H a rvey

H enry M a r k H o lzer

N o rm a n K a rlin

H a rriet M . K ing

J oerg W . K nipprath

M ich a el I. K rauss

G ary L a w son

W illia m M ayton

D a n iel P o lsby

C h a rles E . R ice

B ern a rd S ieg an

Co-Counsel for Amicus

* C lint B o lick

A llyson T ucker

J era ld L. H ill

M a rk J . B redem eir

Landmark Legal

Foundation

Center for Civil Rights

216 G Street, NE

Washington, D.C. 20002

(202) 546-6045

*Counsel of Record

10 We also ask the Court to grant certiorari, and to reverse

and remand in light of its decision in the instant case, the

decisions of the Tenth Circuit cited in footnote 1, supra, pre

senting unitary status issues in the Denver and Topeka deseg

regation cases.