Alexander v. Riga Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Appellants Urging Reversal

Public Court Documents

June 3, 1999

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Alexander v. Riga Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Appellants Urging Reversal, 1999. 19d3c37f-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e16a66fc-5afb-4e64-b3e8-d21062e45bc4/alexander-v-riga-brief-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae-supporting-appellants-urging-reversal. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

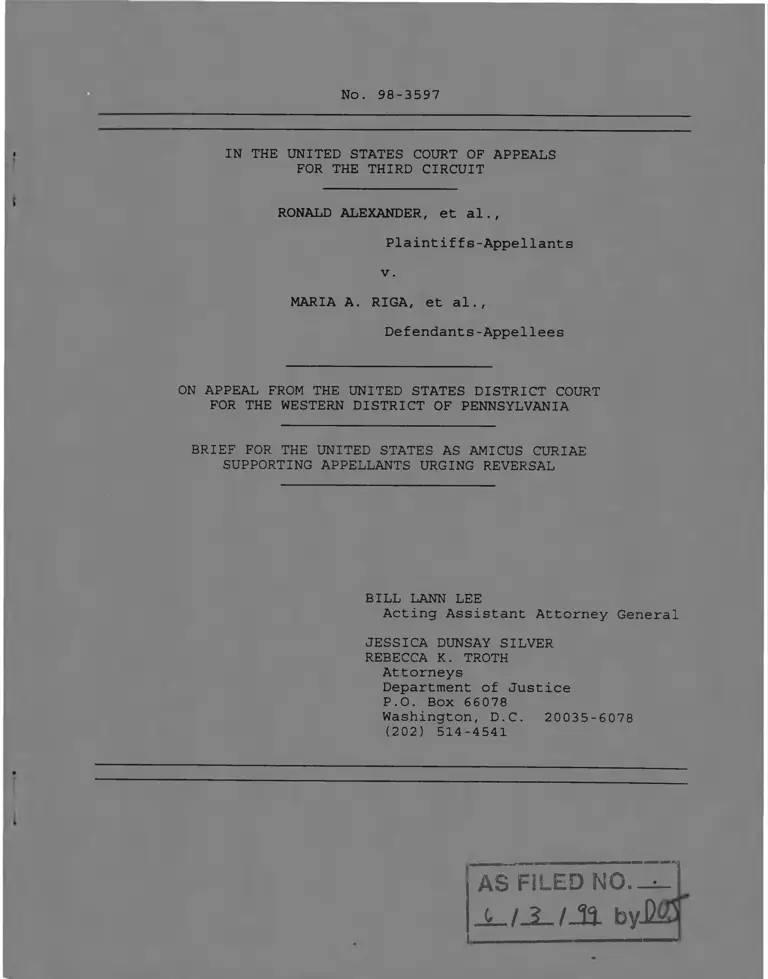

No. 98-3597

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

RONALD ALEXANDER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

MARIA A. RIGA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

SUPPORTING APPELLANTS URGING REVERSAL

BILL LANN LEE

Acting Assistant Attorney General

JESSICA DUNSAY SILVER

REBECCA K. TROTH

Attorneys

Department of Justice

P.O. Box 66078

Washington, D.C. 20035-6078

(202) 514-4541

AS FILED NO.—

A -.I3 -IJX b y !

memrt

Caroline M itchell

Attorney & Counsellor at Law

3700 Gulf Building

707 Grant Street

Pittsburgh, P ennsylvama U.S.A . 15219-1913

412-232-3131

Fax 412-456-2355

email - cmitcpghpa@aol.com

Ju n e 14, 1999

Steve R alston, E squire

NAACP Legal Defense and

E ducationa l F und , Inc.

99 H udson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

D ear Mr. R alston an d Ms. Troth:

Rebecca K. T roth, E squire

D epartm en t of Ju s tic e

P.O. Box 66078

W ashington, DC 20035-6078

I am pleased to enclose for Legal Defense F u n d ’s u se a copy of the

am icus filed by the U.S. D epartm ent of Ju s tic e and I am forw arding a

copy of the Legal Defense F u n d ’s b rief to Rebecca Troth. T h an k you so

m u ch for your respective briefs. I am su re the Third C ircuit will be m ost

in te res ted in the am ici’s views on these im portan t issues.

Best regards,

Caroline M itcfiett

Caroline Mitchell

cm /p ink

E nclosure - Copies of Brief

mailto:cmitcpghpa@aol.com

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

STATEMENT OF THE I S S U E S ......................................... 1

IDENTITY AND INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES AS

AMICUS CURIAE .............................................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ..............................................2

A. Proceedings Below ..................................... 2

B. Statement Of F a c t s .................................... 4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT............................................11

ARGUMENT:

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED AS A MATTER OF LAW

IN REFUSING TO SUBMIT THE ISSUE OF PUNITIVE

DAMAGES TO THE J U R Y ................................... 13

A. Punitive Damages Serve Important Statutory-

Purposes .......................................... 1 3

B. No Finding Of Outrageous Conduct Is

Required For A Jury To Consider Punitive

D a m a g e s .......................................... 1 4

C. Punitive Damages Can Be Awarded Absent An

Award Of Compensatory D a m a g e s .................. 18

II. PLAINTIFFS ARE ENTITLED TO A HEARING ON

INJUNCTIVE R E L I E F ................. •................. 22

C O N C L U S I O N .................................................... 2 5

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES:

Asbury v. Brougham. 866 F.2d 1276 (10th Cir. 1989) ......... 18

Basistfl V. Weir, 340 F .2d 74 (3d Cir. 1965) . . . 15, 19, 20, 21

Beacon Theatres. Inc, v. Westover, 359 U.S. 500 (1959) . . . 24

i

CASES (continued): PAGE

Bolden v. Southeastern Pennsylvania Transo. Auth_.__(..SEPTA) ,

21 F . 3d 29 (3d Cir. 1994) .............................. 15

Burnett v. Grattan. 468 U.S. 42 (1984) ...................... 15

Campos-Orrego v. Rivera. No. 98-1318, 1999 WL 254470

(1st Cir. May 4, 1 9 9 9 ) ................................... 21

Fountila v. Carter. 571 F.2d 487 (9th Cir. 1978) ........... 20

Hennessv v. Penril Datacomm Networks._Inc •, 69 F.3d 1344

(7th Cir. 1995) 20

Keenan v. Philadelphia. 983 F.2d 459

(3d Cir. 1 9 9 2 ) ............................................ 17

LeBlanc-Sternberg v. Fletcher. 67 F.3d 412 (2d Cir. 1995),

cert, denied, 518 U.S. 1017 (1996) ............... 21, 23

Louisiana v. United States. 380 U.S. 145 (1965)............. 22

Marable v. Walker. 704 F.2d 1219 (11th Cir. 1 9 8 3 ) ........... 23

Miller v . Apartments & Homes of New Jersey._Inc.,

646 F . 2d 101 (3d Cir. 1981) ........................19, 22

People Helpers Found.._Inc. v. Richmond,

12 F . 3d 1321 (4th Cir. 1 9 9 3 ) .......................... 21-22

Raain v. Harry Macklowe Real Estate Co., 6 F.3d 898

(2d Cir. 1 9 9 3 ) ............................................ 18

Rogers v. Loether. 467 F.2d 1110 (7th Cir. 1972),

aff'd on other grounds, sub nom Curtis v. Loether,

415 U.S. 189 (1974) ................................. 19, 20

Rowlett V. Anheuser-Busch,_Inc.,, , 832 F.2d 194

(1st Cir. 1987) 17

Samaritan Inns, Inc, v. District of Columbia. 114 F.3d

1227 (D.C. Cir. 1997) 18

Sandford v. R. L, Coleman Realty Co.. 573 F.2d 173

(4th Cir. 1978) 23

Savarese v. Acriss. 883 F.2d 1194 (3d Cir. 1989) . . 15, 16, 17

Smith v. Wade. 461 U.S. 30 (1983)...........................passim

li

CASES (continued): PAGE

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park. Inc.. 396 U.S. 229

(1969).................................................... 15

Temple Univ. v. White. 941 F.2d 201 (3d Cir. 1991),

cert, denied, 502 U.S. 1032 (1992)..................... 23

Timm v. Progressive Steel Treating. Inc.. 137 F.3d 1008

(7th Cir. 1998) 21

United States v. Balistrieri. 981 F.2d 916 (7th Cir. 1992),

cert, denied, 510 U.S. 812 (1993) ................. 17, 18

United States v. Yonkers Bd. of Educ.. 837 F.2d 1181

(2d Cir. 1987), cert, denied, 486 U.S. 1055 (1988) . . . 22

United States v. Paradise. 480 U.S. 149 (1987) ............. 22

STATUTES:

Fair Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. 3601, seq................. passim

42 U.S.C. 3612 (a) 2

42 U.S.C. 3612 (c) 2

42 U.S.C. 3612 (o* ( 3 ) ........................................ 2

42 U.S.C. 3 6 1 3 ...............................................2

42 U.S.C. 3613 (c) .................................2, 12, 14

42 U.S.C. 3 6 1 4 ...............................................2

42 U.S.C. 3614(d) 2

Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. 1396, £t seq. ............... 23

42 U.S.C. 1982 ................................................ 22

42 U.S.C. 1983 ............................................ passim

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY:

H.R. Rep. No. 711, 100th Cong., 2d Sess. (1988) ......... 13, 14

RULES:

Fed. R. App. P. 2 9 ( a ) .......................... ................. 2

- iii -

MISCELLANEOUS: PAGE

Robert G. Schwemm, Housing Discrimination: Law and

Litigation § 25.3(2)(b) (1990 & Supp. 1997) . 12, 14, 22-23

9 WRIGHT & MILLER, Federal Practice and Procedure:

Civil 2d § 2338 (2d ed. 1994) .......................... 24

IV

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

No. 98-3597

RONALD ALEXANDER, et al.,

Plaint if fs-Appe Hants

v .

MARIA A. RIGA, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

SUPPORTING APPELLANTS URGING REVERSAL

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

The United States will address the following issues:

1. Whether the district court erred in refusing to submit

the issue of punitive damages to the jury after the jury found

that defendants had discriminated on the basis of race in

violation of the Fair Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. 3601, £t seq.. but

awarded neither compensatory nor nominal damages.

2. Whether the district court erred in refusing to hear

evidence on plaintiffs' request for injunctive relief after the

jury found that defendants had discriminated on the basis of race

in violation of the Fair Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. 3601, seq.

IDENTITY AND INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

The Attorney General is responsible for all federal court

enforcement of the Fair Housing Act by the United States. Under

- 2 -

42 U.S.C. 3614, the Attorney General is authorized to bring an

action alleging a pattern or practice of discrimination in

violation of the Fair Housing Act. In such an action, the United

States is authorized to seek injunctive relief and monetary

damages on behalf of persons aggrieved by such discrimination.

See 42 U.S.C. 3614(d). In addition, if an individual elects

under 42 U.S.C. 3612(a) to pursue a charge of discrimination in a

civil action, pursuant to 42 U.S.C. 3612(o), the Secretary of

Housing and Urban Development shall authorize the Attorney

General to file a civil action on behalf of the aggrieved person.

In such a case, the United States is authorized to seek the same

equitable and monetary relief on behalf of any aggrieved person

that such individual could obtain in a private suit under 42

U.S.C. 3613, including "actual and punitive damages." 42 U.S.C.

3612(o)(3), 3613(c). The issues in this case involve the scope

of relief available under the Act and their resolution will

affect the Attorney General's enforcement program. The United

States files this brief pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 29(a).

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Proceedings Below

In January 1996, plaintiffs Ronald and Faye Alexander and

the Fair Housing Partnership of Greater Pittsburgh, Inc. (FHP)

sued apartment owners Joseph and Maria Riga for discriminating

against them in the rental of an apartment in violation of the

-3-

Fair Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. 3601 (App. 19-30).17 The complaint

sought compensatory and punitive damages, along with declaratory

and injunctive relief. Plaintiffs repeated their request for the

various forms of relief in Plaintiffs' Amended Pretrial Narrative

Statement (filed May 23, 1997) (R. 33). The Statement contains a

one-page description of the equitable relief sought, including an

order requiring the posting of fair housing notices and a cease

and desist order prohibiting defendants from discriminating on

the basis of race.

After eight days of trial, on May 22, 1998, the jury

answered a set of special interrogatories and found that

defendant Maria Riga had discriminated against the Alexanders

(Tr. 902-903).2/ The jury, however, declined to award

compensatory or nominal damages and found that Maria Riga's

discriminatory conduct was not "a legal cause of harm to the

plaintiff [s] " (Tr. 902-904). The jury also found that Maria Riga

had discriminated against the FHP but again declined to award any

damages, although it did find that Maria Riga's actions were "a

legal cause of harm" to the FHP (Tr. 903-904) . The court, having

bifurcated the deliberations for the purpose of considering

punitive damages, then refused to submit to the jury the issue of

i7 "App. __ " refers to the appendix filed by appellants.

"Tr. __" refers to the trial transcript. "Mem. Op. __" refers to

the Memorandum opinion the district court entered on October 13,

1998, which is found at page 940 of appellants' appendix.

"R- __ " refers to entries in the district court docket sheet.

J Maria Riga's husband, Joseph, is the co-owner of the

apartment building but was out of the country during the events

at issue in this case (Tr. 509).

-4-

punitive damages (Tr. 907). The court entered judgment in favor

of the defendants (R. 80).

On May 28, 1998, plaintiffs filed post-trial motions:

M) to enter a judgment notwithstanding the verdict, to issue an

additur of nominal damages in the amount of one dollar for each

plaintiff, or to grant a new trial on compensatory, punitive, and

nominal damages or, in the alternative, award punitive damages as

a matter of law against both Maria and Joseph Riga; (2) for a

hearing on injunctive relief; (3) for attorney's fees, costs and

expenses; and (4) to grant plaintiffs judgment as a matter of law

(App. 921-938). Defendants moved to 'tax costs against the

plaintiffs (R. 87).

On October 13, 1998, the district court denied the

plaintiffs' motions except for the FHP's motion to have judgment

entered in its favor, denied defendants' motion to tax costs, and

entered judgment (App. 939, 961-962). Plaintiffs filed a timely

notice of appeal on November 5, 1998 (App. 3).

B . Statement Of Facts

1. Ronald and Faye Alexander are a black couple who began

apartment hunting in September 1995 (Tr. 8, 367-369) . On

September 17, 1995, Faye Alexander saw an advertisement in the

Sunday newspaper for an apartment at 5839 Darlington Road in the

Squirrel Hill area of Pittsburgh, which is a predominantly white

neighborhood (Tr. 9-10, 15, 697). After making an appointment to

see the apartment at noon on Monday, September 18, the Alexanders

changed the appointment to 1:00 (Tr. 9-18). The Alexanders

-5-

arrived a few minutes early and waited for the apartment's co

owner, Maria Riga, who is white (Tr. 16-17, 375-376). Ms. Riga

and her husband owned the entire building on Darlington Road,

which had four apartments in addition to the one at issue here

(Tr. 506-507). When Ms. Riga arrived, she walked up to the

Alexanders' car and said they should not have changed the

appointment since they had "just missed the apartment" (Tr. 18).

Although Ms. Riga said she had tried to call to tell them, there

was no message on their answering machine or a number on the

Caller I.D. when they got home (Tr. 19-20, 379).

Over the next several weeks, Maria Riga continued to

advertise the apartment at 5839 Darlington Road in the Sunday

newspapers. At the same time, Ms. Riga repeatedly denied the

apartment was available in response to the Alexanders' inquiries.

After seeing the same advertisement in the newspaper on Sunday,

September 24, 1995, they began to suspect that Maria Riga had

lied to them about the apartment's availability (Tr. 21-22, 381-

382). On Tuesday, September 26, Ronald Alexander called a

friend, Robin McDonough, to see if she would check on the

apartment (Tr. 383-384). Robin McDonough is white (Tr. 202-204)

Ms. McDonough reported to Alexander that when she called the

number in the advertisement, Ms. Riga told her the apartment was

available and made an appointment to show it to her, which

McDonough later canceled (Tr. 202-205, 383).

On that same Tuesday, September 26, Ronald Alexander called

Maria Riga and left a message using a different name, James

- 6 -

Irwin, because he thought it would allow him to determine if Riga

was being honest with him (Tr. 383-384) . A woman called back and

Alexander made an appointment, as James Irwin, to see the

apartment on Friday, September 29, at 11:30 (Tr. 384-385). When

he got to the apartment building that morning, Alexander saw an

"Apartment for Rent" sign in front and Maria Riga sitting on the

top porch step (Tr. 389-391). As he walked up to her, Alexander

said he was James Irwin and that he had an 11:30 appointment (Tr.

391). Maria Riga responded that she had come "all this way" but

had forgotten her keys (Tr. 392). Alexander asked if he could

reschedule and Maria said yes, and that he had her number (Tr.

392-393). Alexander, however, could see that she had covered up

a set of keys with her hand as he was standing there and as he

walked away, he heard the keys scrape as she got up and entered

the building (Tr. 392-394). Alexander called and left messages

asking to reschedule but Riga never called back (Tr. 395-397).

Before his appointment at the apartment that morning,

Alexander had met with an attorney, Caroline Mitchell (Tr. 385).

After the incident with the keys, Alexander called Mitchell to

report what had happened (Tr. 394). Alexander and Mitchell spoke

later in the afternoon with Andrea Blinn, the testing coordinator

of the Fair Housing Partnership of Pittsburgh, Inc. (FHP) (Tr.

48-49, 60, 394) .

As a result of that conversation, Andrea Blinn of the FHP

arranged to have a test of Ms. Riga's practices to see whether

she was discriminating against potential renters on the basis of

-7-

race (Tr. 60-61). FHP was concerned about the report of alleged

discrimination in Squirrel Hill, a predominantly white area,

because such an "unchecked act of discrimination, though it may

be small, can have a very strong impact upon the overall

S0gi-ega.tion in our community" by discouraging other black people

from seeking housing in that area (Tr. 697-698).

One of the testers was a white male, Dennis Orvosh, and the

other was a black female, Daria Mitchell (Tr. 62). Both testers

made appointments for the next day, September 30 (Tr. 67-69).

Dennis Orvosh appeared for his appointment at 11:00 (Tr. 264-

265). He met Maria Riga, who showed him the apartment and said

it was available immediately (Tr. 268). Orvosh told Maria Riga

that he would talk to his wife about the apartment and would get

back to her if they wanted to rent the apartment or see it again

(Tr. 268). At Andrea Blinn's request, he called Maria Riga back

on Monday, October 2, to make another appointment to see the

apartment (Tr. 269-270). Ms. Riga confirmed it was still

available (Tr. 270). Orvosh then called the next day to cancel

the appointment, after confirming again that it was still

available (Tr. 271).

Daria Mitchell, the black tester, made an appointment to see

the apartment at 1:00 on Saturday, September 30, but arrived at

1:24 because she had the wrong address (Tr. 295-302) . Ms.

Mitchell called and rescheduled the appointment for 5:30 that

afternoon (Tr. 302). When Daria Mitchell arrived at the

apartment at 5:30, she saw Maria Riga talking with a white male

- 8 -

(Tr. 303). Maria Riga told Daria Mitchell that the man's name

was Jeff and that he had filled out an application for the

apartment (Tr. 303). Riga showed Mitchell the apartment but told

her that Jeff was "going to get the apartment" (Tr. 304). Riga

promised Mitchell that "if anything became available, she would

call [her]" (Tr. 304-305).

The man with whom Maria Riga was speaking when Daria

Mitchell arrived was Jeffrey Lang, a private detective Caroline

Mitchell had hired (Tr. 139-147, 197-198). On that Saturday,

September 30, 1995, Lang called the number in the September 24

advertisement for the Rigas' apartment and a woman, who

identified herself as Carla, returned his call (Tr. 143-145) .

He made an appointment to see the apartment and when he arrived

at about 5:00, the woman who had said she was "Carla" admitted

her name was Maria Riga (Tr. 151-156) . Riga showed him the

apartment (Tr. 151-156) . Although he had not asked for one, Riga

gave Lang a rental application and said she wanted him to move in

(Tr. 157-162) . Lang never said he intended to rent the apartment

but said only that it was nice and that he would like his wife to

see it (Tr. 169, 183-184).

As Lang was leaving, he and Riga saw Daria Mitchell coming

toward the building (Tr. 166). Lang asked Riga "if this was the

5:30 appointment and Maria rolled her eyes and went on to state

that it was and that this woman was, quote, driving me up a wall,

unquote" (Tr. 166). Maria Riga then said that she would "have to

tell" Ms. Mitchell that she had given him an application (Tr.

-9-

166). When Ms. Mitchell walked up onto the porch, Maria Riga

told Ms. Mitchell in a "harsh" tone that "I'll show you the

apartment, but I already gave this gentleman an application" (Tr.

167-168). Even though Daria Mitchell had asked Maria Riga to let

her know if the apartment became available, Riga never called

Mitchell to let her know that Lang had not rented the apartment

and that it was still available (Tr. 303-305) .

An advertisement for the apartment was again in the

newspaper on Sunday, October 1 (Tr. 397-398). Ronald Alexander

called again, identified himself as James Irwin and asked if the

apartment was still available (Tr. 398). Maria Riga said it had

been rented (Tr. 398), contrary to her representations to Orvosh

on October 2 and 3 (Tr. 270-271). When Alexander said he liked

the building and asked her to call him if space became available,

Riga said she would take his number but that she did not

anticipate any apartments becoming available soon (Tr. 399).

After leaving several more messages that were .not returned,

Alexander reached Riga later that week. She again denied there

was an apartment available (Tr. 404-408) .

The Alexanders saw yet another advertisement for the

apartment in the Sunday paper on October 8, and Ronald Alexander

called using his real name (Tr. 410). This time, Maria Riga said

that she had placed the ad prematurely since the people had not

vacated the apartment and it was not available to be seen (Tr.

410). At Ronald Alexander's request, Robin McDonough called Riga

about the apartment to see if Riga was "discriminating against the

- 10 -

Alexanders because they were black (Tr. 411). McDonough called

Maria Riga and arranged to see the apartment on October 9 (Tr.

206-207, 412-413). Maria Riga showed Robin McDonough the vacant

apartment the next day and said that it was available immediately

(Tr. 208). Maria Riga's treatment of McDonough was "cordial"

(Tr. 208) .

Maria Riga continued to place ads for the apartment through

the first week of November (Tr. 595). She finally rented the

apartment to a couple on November 18, 1995 (Tr. 363-364, 748;

Exh. 23). Mr. Sinha, the husband, was from India, and the wife

evidently was not a member of any minority group (Tr. 742). At

trial, Maria Riga denied she had ever seen the Alexanders or had

any appointments with them (Tr. 556-560, 596, 738)

2. In denying the Alexanders' request to submit the

punitive damages issue to the jury, the district court found that

punitive damages were precluded because the jury's refusal to

award damages showed that it "did not consider the conduct of

Mrs. Riga to have been the result of an evil motive or intent or

to have involved .reckless or callous indifference to the

federally protected rights of plaintiffs." Mem. Op. at 10 (App.

949). In the court's view, it thus "would be inappropriate to

permit the jury to award punitive damages to them." Mem. Op. at

10 (App. 949). The court also held that more than intentional

discrimination is required for the jury to enter punitive damages

-- that "outrageous conduct on the part of Mrs. Riga 'beyond that

which may attach to any finding of intentional discrimination'"

- 11 -

was required. Mem. Op. at 11 (App. 950). It was significant in

the court's view that "Mrs. Riga's conduct did not cause [Faye

Alexander] to cry, to become ill, to suffer any emotional

distress or to seek medical or psychological care, and Mr. •

Alexander testified that, although he suffered emotional distress

as a result of Mrs. Riga's conduct, he sought no medical

attention or psychological counseling." Mem. Op. at 11 (App.

950) .

The court denied plaintiffs' request to present evidence on

the need for injunctive relief, asserting that plaintiffs had

waived the request because, although it had been a significant

portion of the complaint and the pretrial statement, plaintiffs

had not repeated the request until six days after the jury trial.

Mem. Op. at 15 (App. 954). The court also found that even if

plaintiffs had not waived the request, there was no need for

injunctive relief since there was no evidence of a continuing or

recurrent violation. Mem. Op. at 16 (App. 955). Plaintiffs

filed a notice of appeal on November 5, 1998 (App. 3).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The jury found here that Maria Riga had intentionally

discriminated against Faye and Ronald Alexander because they were

black, and the evidence showed a calculated pattern of repeatedly

refusing to show the apartment or give truthful information to

black potential renters. Despite the jury verdict of liability

for this pattern of blatant racial discrimination, the defendants

will suffer no adverse consequences for the actions of Ms. Riga

- 12 -

because the district court refused to consider further relief.

Thirty years after Congress declared racial discrimination

unlawful and ten years after Congress amended the Act to

strengthen enforcement (in part by eliminating the cap on

punitive damages), this is an untenable result.

Punitive damages and injunctive relief are two of the most

effective means of enforcing the Act and are intended to change

the behavior of violators, as well as those who might violate the

Act in the future. They are especially important in the context

of the Fair Housing Act since " [m]ost fair housing cases do not

involve major economic losses." Robert G. Schwemm, Housing

Discrimination: Law and Litigation § 25.3(2) (b) at 25-19 (1990 &

Supp. 1997). Under the language of the punitive damages

provision of the statute, 42 U.S.C. 3613(c), and the standards

governing the award of punitive damages under civil rights

statutes, see Smith v. Wade. 461 U.S. 30 (1983), the court erred

in refusing to submit the issue of punitive damages to the jury.

Similarly, the purposes of the Fair Housing Act to prevent and

deter housing discrimination are frustrated by the court's

erroneous refusal to even hear evidence on the need for equitable

relief after a jury finding of intentional discrimination.

-13-

ARGUMENT

I

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED AS A MATTER OF LAW

IN REFUSING TO SUBMIT THE ISSUE OF

PUNITIVE DAMAGES TO THE JURY

A. Punitive Damages Serve Important Statutory Purposes

In amending the Fair Housing Act in 1988, Congress found

that, twenty years after the Act's passage, "discrimination and

segregation in housing continue to be pervasive." H.R. Rep. No.

711, 100th Cong., 2d Sess. 15 (1988). Congress cited several

regional studies that demonstrated that blacks continue to face a

significant probability of being discriminated against in both

housing sales and rentals. H.R. Rep. No. 711 at 15. Congress

also cited a national study by the Department of Housing and

Urban Development that concluded that "a black person who visits

4 agents can expect to encounter at least one instance of

discrimination 72 percent of the time for rentals and 48 percent

of the time for sales." H.R. Rep. No. 711 at 15.

Congress concluded that in spite of the clear national

policy articulated in the Act since 1968, the Act provided "only

limited means for enforcing the law," which Congress viewed as

"the primary weakness in existing law." H.R. Rep. No. 711 at 15.

Weaknesses in the Act's enforcement by private parties included

"lack of private resources" and "disadvantageous limitations on

punitive damages." H.R. Rep. No. 711 at 16. As the House Report

stated: " [t]he Committee believes that the limit on punitive

damages served as a major impediment to imposing an effective

-14-

deterrent on violators and a disincentive for private persons to

bring suits under existing law." H.R. Rep. No. 711 at 40. As a

result, Congress amended the Act to remove the $1000 limitation

on the award of punitive damages that had been part of the Act

originally. The Act now provides, under 42 U.S.C. 3613(c), that

"the court may award to the plaintiff actual and punitive

damages." Such damages are intended to ensure effective

enforcement and deterrence -- major purposes of the Fair Housing

Act. These purposes are distinct from Congress' intent to

compensate individuals for actual damages incurred as a result of

discriminatory housing practices since it is often difficult to

prove that substantial losses were caused by such discrimination.

See Robert G. Schwemm, Housing Discrimination: Law and Litigation

§ 25.3(2)(b) (1990 & Supp. 1997).

B. No Finding Of Outrageous Conduct Is Required For A Jury

To Consider Punitive Damages_____________________________

The district court misconstrued the statutory provision

allowing punitive damages when it held that such damages could

not be awarded absent a showing of "outrageous" conduct that, for

example, caused Faye Alexander to "cry, to become ill, [or] to

suffer any emotional distress or to seek medical or psychological

care." Mem. Op. at 11 (App. 950). The court confused the sort

of evidence that would justify compensation for actual injury

with the evidence required to support an award of punitive

damages.

It is well-established that where a cause of action arises

out of a federal statute, federal, not state, law governs the

-15-

scope of the remedy available to plaintiffs. Burnett v. Grattan.

468 U.S. 42, 47-48 (1984); Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park._Inc.,

396 U.S. 229, 240 (1969). The rationale for the rule is that

Congress did not intend to subject the rights of individuals

under federal remedial legislation to the vagaries of various

state laws, which "would fail to effect the purposes and ends

which Congress intended." Basista v. Weir. 340 F.2d 74, 86 (3d

Cir. 1965) . Consistent with this principle, this Court has a

"policy of striving for federal uniformity in the area of damages

in civil rights cases." Savarese v. Agriss. 883 F.2d 1194, 1207

(3d Cir. 1989). As they strive for such uniformity, courts "must

bear in mind that the civil rights laws are intended in part to

provide broad, consistent recompense for violations of civil

rights." Bolden v. Southeastern Pennsylvania Transp. Auth.. 21

F.3d 29, 35 (3d Cir. 1994) (citing Basista. 340 F.2d at 74).

In Smith v. Wade. 461 U.S. 30, 51 (1983), the Supreme Court

established the standard for the award of punitive damages for a

deprivation of a federally protected civil right, and rejected

the claim that the threshold showing required to submit the issue

of punitive damages to a jury is higher than the standard for

liability and compensatory damages. In an action under 42 U.S.C.

1983, the Court held that a "reckless or callous disregard for

the plaintiff's rights, as well as intentional violations of

federal law, should be sufficient to trigger a jury's

consideration of the appropriateness of punitive damages."

-16-

461 U.S. at 51 . 11 A plaintiff need not show ill will, evil

purpose, or malicious intent to be entitled to punitive damages.

See 461 U.S. at 48 ("punitive damages * * * may be awarded not

only for actual intent to injure or evil motive, but also for

recklessness [and] serious indifference to or disregard for the

rights of others"); 461 U.S. at 51 (the district court did not

err in not requiring "actual malicious intent"). Importantly,

punitive damages, unlike compensatory damages, are "never awarded

as of right, no matter how egregious the defendant's conduct."

461 U.S. at 52. The question whether to award such damages is

left to the discretion of the jury. Ibid.

This Court has applied Smith v. Wade to requests for

punitive damages under federal civil rights statutes and reversed

a district court for applying a standard similar to the one the

district court applied here. In Savarese v. Agriss. 883 F.2d

1194, 1204 (3d Cir. 1989), a 42 U.S.C. 1983 action, the district

court instructed the jury that plaintiffs had to show by a

preponderance of the evidence that " [d]efendants have engaged in

conduct that was so outrageous, so vicious, so intentionally

harmful that they should be punished for that conduct." 883 F.2d

at 1205. This Court reversed and held that the instructions

17 Application of the standard announced in Smith v. Wade in

the context of punitive damages under 42 U.S.C. 1981a(b)(1) is at

issue in the Supreme Court in Kolstad v. American Dental Ass'n.

No. 98-208 (argued March 1, 1999). The United States filed an

amicus brief in that case supporting petitioner and arguing that

the standard of reckless indifference to federal rights contains

no "outrageousness" requirement.

-17-

could have led the jury to believe that a reckless disregard of

an individual's federally protected rights was insufficient to

support an award of punitive damages. 883 F.2d at 1205.A/

In Keenan v. Philadelphia, 983 F.2d 459, 469-470 (3d Cir. 1992),

this Court applied Smith v. Wade and upheld punitive damages in a

Section 1983 action for discrimination, retaliation, and

violation of First Amendment rights. This Court determined that

defendants' repeated deliberate acts of discrimination based on

sex "exhibited a reckless or callous disregard of or indifference

to the rights of [the plaintiffs]" justifying the imposition of

punitive damages. 983 F.2d at 470. This Court thus has rejected

a requirement of egregious or outrageous conduct, finding that

acts of intentional discrimination in deliberate or reckless

disregard of plaintiffs' civil rights are sufficient to warrant

punitive damages. Cf. Rowlett v. Anheuser-Busch. Inc.. 832 F.2d

194, 206 (1st Cir. 1987) ("[a]fter all, can it really be disputed

that intentionally discriminating against a black man on the

basis of his skin color is worthy of some outrage?").

While this Circuit has not had occasion to apply Smith v.

Wade in the context of the Fair Housing Act, other courts of

appeals have found its application appropriate there as well.

In United States v. Balistrieri. 981 F.2d 916 (7th Cir. 1992),

cert, denied, 510 U.S. 812 (1993), the Seventh Circuit held in a

- Thus, although the district court here cited Savarese to

support its refusal to submit the punitive damages issue to the

jury, Mem. Op. at 10 (App. 949), the case in fact supports

reversal of its ruling.

-18-

case involving housing testers that the district court erred in

directing a verdict for the defendant on punitive damages where

there was evidence of intentional racial discrimination. The

court found that "[t]he jury could reasonably find from the

defendants' systematic practice of treating black apartment

seekers less favorably than whites that the defendants

consciously and intentionally discriminated against potential

black renters." 981 F.2d at 936. See also Samaritan Inns. Inc.

v. District of Columbia. 114 F.3d 1227 (D.C. Cir. 1997) (applying

Smith v. Wade to claims for punitive damages under the Fair

Housing Act); Ragin v. Harry Macklowe Real Estate Co.. 6 F.3d 898

(2d Cir. 1993) (same); Asbury v. Brougham. 866 F.2d 1276, 1282

(10th Cir. 1989) (same).

Discriminating against potential renters on the basis of

race has been illegal for over thirty years. There was never any

suggestion in this case that Ms. Riga did not understand what

discrimination was or that it was illegal to discriminate (see

Tr. 741-743) . Under the correct standard, a jury would be fully

justified in awarding punitive damages to the Alexanders in

response to Maria Riga's systematic, deceitful, and repeated

refusal to show the apartment to black potential renters.

C. Punitive Damages Can Be Awarded Absent An Award Of

Compensatory Damages________________________________

The language of the Fair Housing Act does not limit the

availability of punitive damages to cases in which compensatory

damages have been awarded. Imposing such a requirement on the

award of punitive damages would frustrate Congress's purpose in

-19-

allowing punitive damages and in removing the limit on such

awards when it amended the Act in 1988. The issue whether to

award punitive damages is distinct from the issue whether the

plaintiffs have suffered compensable harm. The purpose of

punitive damages is to punish and deter, whereas the purpose of

compensatory damages is to compensate the plaintiffs for any

actual harm they have suffered. See Smith v. Wade. 461 U.S. at

54 (when considering punitive damages, the court should focus on

the character of the defendant's conduct and whether it calls for

deterrence and punishment over and above that provided by

compensatory awards).

As a threshold matter, whether punitive damages can be

awarded absent an award of compensatory damages in a case arising

under a federal statute is, as noted above, an issue governed by

federal law. See Miller v. Apartments & Homes of New Jersey.

Inc.. 646 F.2d 101, 108 (3d Cir. 1981) (federal law governs

availability of contribution under the Fair Housing Act); Basista

v. Weir. 340 F.2d 74, 86-87 (3d Cir. 1965) (federal common law

governs issue of punitive damages in case under 42 U.S.C. 1983).

Applying federal law, the courts of appeals for the Ninth and

Seventh Circuits have found that punitive damages are recoverable

under the Fair Housing Act absent an award of actual damages.

In Rogers v. Loether. 467 F.2d 1110 (7th Cir. 1972), aff'd on

other grounds, sub nom Curtis v. Loether. 415 U.S. 189 (1974),

the district court found in a Fair Housing Act case that the

plaintiff had suffered no actual damages, but assessed punitive

- 20 -

damages of $250. The court of appeals, although reversing

because the trial court had incorrectly denied defendant a jury

trial, considered the language of the Fair Housing Act and

concluded that it "does not require a finding of actual damages

as a condition to the award of punitive damages." 467 F.2d at

1112 & n .4. In Fountila v. Carter. 571 F.2d 487, 491-492 (9th

Cir. 1978), also a Fair Housing Act case, the Ninth Circuit,

citing Rogers v. Loether. similarly concluded that actual damages

are not a prerequisite for entry of punitive damages.

Other courts, including this Court, have reached the same

conclusion under other federal civil rights statutes. In Basista

v. Weir. 340 F.2d 74, 85-88 (3d Cir. 1965), this Court held that

actual damages were not required for an award of punitive damages

in a 42 U.S.C. 1983 case alleging illegal arrest and wrongful

incarceration by police officers. The court noted that:

* * * there is neither sense nor reason in the

proposition that such additional damages may be

recovered by a plaintiff who is able to show

that he has lost $10, and may not be recovered by

some other plaintiff who has sustained, it may be, far

greater injury, but is unable to prove that he is

poorer in pocket by the wrongdoing of defendant.

340 F.2d at 88, quoting Press Pub. Co. v. Monroe. 73 F. 196, 201

(S.D.N.Y), appeal dismissed, 164 U.S. 105 (1896). In Hennessy v.

Penril Datacomm Networks._Inc.. 69 F.3d 1344, 1351-1352 (7th Cir.

1995), the court held that compensatory damages were not required

for an award of punitive damages under Title VII, finding that

the state common law rule that " [pjunitive damages may not be

assessed in the absence of compensatory damages" had no

- 21 -

applicability to a federal civil rights action. See also Timm v.

Progressive Steel Treating._Inc.. 137 F.3d 1008, 1010 (7th Cir.

1998) (jury's award of punitive damages in Title VII sexual

harassment suit may stand despite no compensatory or back pay

award; “[e]xtra-statutory requirements for recovery should not be

invented”); cf. Campos-Orrego v. Rivera. No. 98-1318, 1999 WL

254470, at *6-*7 (1st Cir. May 4, 1999) (citing Basista v. Weir

and allowing punitive damages without an award of compensatory

damages as long as plaintiff made a proper request for nominal

damages)

The only Fair Housing Act case in which a court of appeals

has held that compensatory damages are required for an award of

punitive damages is People Helpers Foundation. Inc, v. Richmond.

12 F.3d 1321 (4th Cir. 1993) . In that case, the court conceded

that, in enacting the Fair Housing Act, Congress “did not limit

punitive damages to situations in which compensatory damages have

been first awarded” and that “[t]here is no established federal

^ The jury did not award nominal damages in this case,

although plaintiffs requested nominal damages before and after

the jury returned its verdict (Tr. 841, 905-906; App. 926-928).

The jury instruction on nominal damages here, to which the

plaintiffs did not object, provided that "if you find that the

plaintiffs are entitled to verdicts in their favor * * * but you

do not find that the plaintiffs sustained substantial actual

damages, then you may return a verdict for the plaintiffs in some

nominal sum, such as one dollar on account of actual damages."

Mem. Op. at 5 (App. 944) (emphasis added). The court of appeals

for the Second Circuit has held that "it is plain error for the

trial court to instruct a jury only that, if the jury finds such

a violation [of the Fair Housing Act], it "may" award such

damages, rather than that it must do so." LeBlanc- Sternberg v.

Fletcher. 67 F.3d 412, 431 (2d Cir. 199-5), cert, denied, 518 U.S.

1017 (1996) .

- 22 -

common law rule that precludes the award of punitive damages in

the absence of an award of compensatory damages.” 12 F.3d at

1326. Nevertheless, the court adopted the state common law tort

rule and vacated the district court's $1 punitive damages award.

The district court here did not purport to adopt state common law

tort rules, but in any event, as explained above, application of

state common law to damages under the Fair Housing Act is

inappropriate because it undermines the statute's purposes. See

generally Miller v. Apartments & Homes of New Jersey. Inc.. 646

F.2d 101, 106-108 (3d Cir. 1981) (under Fair Housing Act and 42

U.S.C. 1982, courts are to adopt rules "to further, but not to

frustrate, the purposes of the civil rights acts").

II

PLAINTIFFS ARE ENTITLED TO A

HEARING ON INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

The plaintiffs also asserted claims for injunctive relief

but the district court refused to hear evidence on the claims

after the jury decided the legal issues. That ruling was

erroneous. Once illegal discrimination has been proved, "[a]

district court has 'not merely the power but the duty to render a

decree which will so far as possible eliminate the discriminatory

effects of the past as well as bar like discrimination in the

future.'" United States v. Yonkers Bd. of Educ.. 837 F.2d 1181,

1236 (2d Cir. 1987), cert, denied, 486 U.S. 1055 (1988) (citing

United States v. Paradise. 480 U.S. 149, 171 (1987) (plurality),

citing Louisiana v. United States. 380 U.S. 145 (1965)); see also

Robert G. Schwemm, Housing Discrimination: Law and Litigation

-23-

§ 25.3(2) (b) (1990 & Supp. 1997) ; cf. Temple Univ. v . White. 941

F .2d 201, 215 (3d Cir. 1991), cert, denied, 502 U.S. 1032 (1992)

(court required to order equitable relief that cures the

violation of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. 1396 seq.. but

is no "broader than necessary to correct the violation"). While

injunctive relief is normally left to the district court's

discretion, the court's refusal here to hold a hearing or

consider injunctive relief after the jury found a violation of

the Fair Housing Act was an abuse of discretion. LeBlanc-

££.grnberg v. Fletcher. 67 F.3d 412, 432 (2d Cir. 1995) (reversing

district court decision refusing to enter injunctive relief after

the jury found that defendants had violated the Fair Housing Act,

42 U.S.C. 1983, and 42 U.S.C. 1985(3)); see also Sandford v. R .

L. Coleman Realty Co.. 573 F.2d 173 (4th Cir. 1978) (district

court's refusal to award injunctive relief against realty company

with policy of discriminating against blacks in rentals and sales

reversed as “clear error’’); Marable v. Walker. 704 F.2d 1219,

1220-1221 (11th Cir. 1983) (district court's injunction, which

merely prohibited landlord from applying rental criteria in a

racially discriminatory manner against plaintiff or anyone else,

was inadequate and did not afford relief required).

Contrary to the district court's finding, the plaintiffs'

complaint and the pretrial memorandum explicitly preserved their

claim for equitable relief. It would have been improper for the

court to consider the claims for equitable relief before the jury

decided the legal claims, and " [a]fter the legal claim has been

-24-

determined the court, in the light of the jury's verdict on the

common issues, may decide whether to award any equitable relief."

9 Charles Alan Wright & Arthur R. Miller, Federal Practice and

Procedure: Civil 2d § 2338 at 223 (2d ed. 1994), citing Beacon

Theatres. Inc, v. Westover. 359 U.S. 500 (1959). The fact that

plaintiffs waited six days after the jury verdict to seek a

hearing on equitable relief should in no way be viewed as a

waiver of such claims, and we know of no case in which a waiver

was found under similar circumstances.

The district court's conclusion that such relief was in any

event unnecessary also is not supported by the record since

plaintiffs sought to introduce evidence of other violations by

Maria Riga in renting other apartments (Tr. 801-815) . The

district court excluded such evidence at trial because, in the

court's view, the case "was a disparate treatment, not a

disparate impact, case." Mem. Op. at 14 (App. 953). The

district court obviously was confused about the sort of evidence

relevant to a claim of discrimination, but even if the district

court properly excluded such evidence at the liability stage,

evidence of other discriminatory acts was clearly relevant to the

need for injunctive relief.

Consideration of injunctive relief is important in cases

such as this in which the jury does not award compensatory

damages and defendants suffer no adverse consequences as a result

of their illegal conduct. Andrea Blinn, now the executive

director of the Fair Housing Partnership of Greater Pittsburgh,

-25-

Inc., testified that the area in which the Alexanders sought to

find an apartment was predominantly white (Tr. 697). An

"unchecked act of discrimination" in a white neighborhood such as

the discrimination proved here can have a snowball effect and

perpetuate segregation by discouraging not only the actual

victims of the discrimination from seeking housing in that area,

but others who learn about it (Tr. 697). The district court had

a duty to consider equitable relief, and its failure in this

regard requires a remand for proper consideration of the

evidence.

CONCLUSION

The district court's judgment should be reversed and the

case remanded for consideration of appropriate relief.

Respectfully submitted,

BILL LANN LEE

Acting Assistant Attorney General

JESSICA DUNSAY SILVER

REBECCA K. TROTH

Attorneys

Department of Justice

P.0. Box 66078

Washington, D.C. 20035-6078

(202) 514-4541

CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE

Pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(C), the undersigned

certifies that this brief complies with the type-volume

limitations of Fed. R. App. P. 32(a)(7)(B). Based on the word-

count in the word-processing system, the brief contains 6545

words. If the court so requests, the undersigned will provide an

electronic version of the brief and/or a copy of the word

printout.

Rebecca K. Troth

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify on June 3, 1999, that I caused to be served

two copies of the foregoing Brief for the United States as Amicus

Curiae Supporting Appellants Urging Reversal by first-class mail,

postage prepaid, on:

Caroline Mitchell

3700 Gulf Building

707 Grant Street

Pittsburgh, PA 15219-1913

Timothy O'Brien

1705 Allegheny Building

429 Forbes Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15219

Thomas M . Hardiman

Titus & McConomy

20th Floor

Four Gateway Center

Pittsburgh, PA 15222

REBECCA K.

Attorney

TROTH

\

i