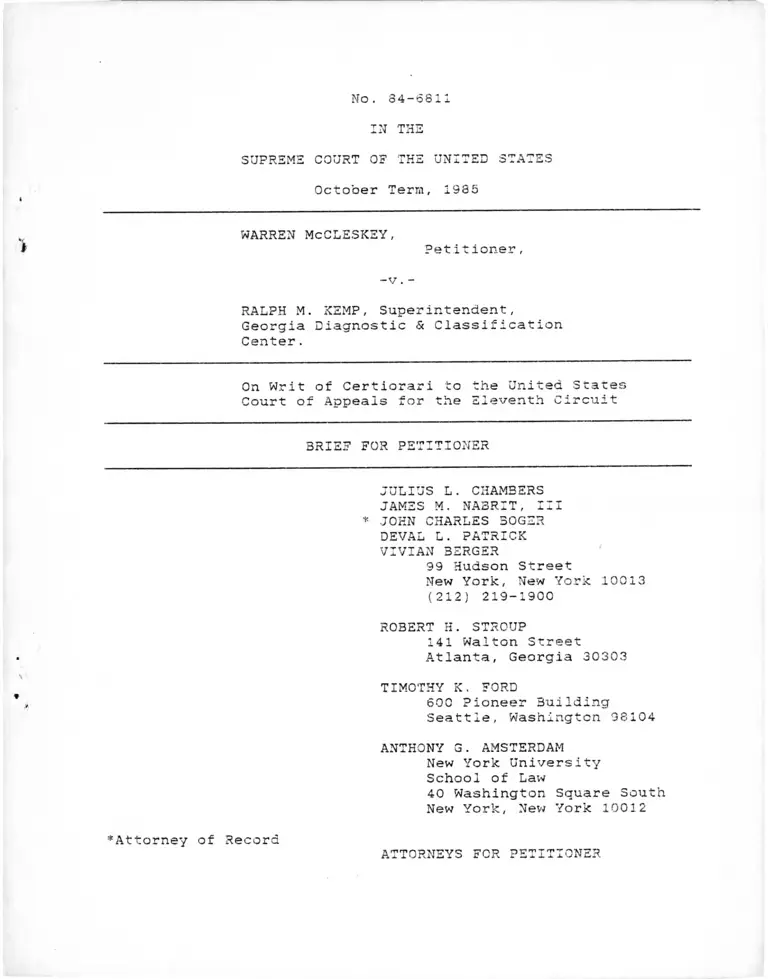

McCleskey v. Kemp Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

August 21, 1986

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCleskey v. Kemp Brief for Petitioner, 1986. a29fe85f-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e17eb03e-373f-4182-bb7e-2ffc19ac20b5/mccleskey-v-kemp-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

No. 84-6811

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1935

WARREN McCLESKSY,

Petitioner,

- v . -

RALPH M. KEMP, Superintendent,

Georgia Diagnostic & Classification

Center.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

3RIEF FOR PETITIONER

JULIUS L . CHAMBERS

JAMES M. NA3RIT, III

* JOHN CHARLES SOGER

DEVAL L. PATRICK

VIVIAN 3ERGER

99 Hudson Street

Mew York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

ROBERT H. STROUP

141 Walton Street

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

TIMOTHY K. FORD

600 Pioneer Building

Seattle, Washington 38104

ANTHONY 3. AMSTERDAM

New York University

School of Law

40 Washington Square South

New York, New York 10012

^Attorney of Record

ATTORNEYS FOR PP T T T n 3NER

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. To make out a prima facie case

under the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, must a condemned

inmate alleging racial discrimination in

a State's application of its capital

sentencing statutes present statistical

evidence "so strong as to permit no

inference other than that the results

are a product of racially discriminatory

intent or purpose?"

2. Is proof of intent to

discriminate a necessary element of an

Eighth Amendment claim that a State has

applied its capital statutes in an

arbitrary, capricious and unequal

manner?

3. Must a condemned inmate present

specific evidence that he was personally

discriminated against in order to obtain

either Eighth or Fourteenth Amendment

relief on the grounds that he was

i

sentenced to die under a statute

administered in an arbitrary or racially

discriminatory manner?

4. Does a proven racial disparity

in the imposition of capital sentences,

reflecting a systematic bias against

black defendants and those whose victims

are white, offend the Eighth or

Fourteenth Amendments irrespective of

its magnitude?

5. Does an average 20-point racial

disparity in death-sentencing rates

among that class of cases in which a

death sentence is a serious possibility

so undermine the evenhandedness of a

capital sentencing system as to violate

the Eighth or Fourteenth Amendment

rights of a death-sentenced black

inmate?

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ................

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BELOW ........

JURISDICTION ......................

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS INVOLVED

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ..............

A. Course of Proceedings . . .

B. Petitioner's Evidence of

Racial Discrimination: The

Baldus Studies ................

C. The Decisions Below . . . .

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................

I. RACE IS AN INVIDIOUS AND

UNCONSTITUTIONAL CONSIDERATION IN

CAPITAL SENTENCING PROCEEDINGS . . .

A. The Equal Protection

Clause Of The

Fourteenth Amendment

Forbids Racial

Discrimination In The

Administration Of

Criminal Statutes . .

B. The Eighth Amendment

Prohibits Racial Bias

In Capital Sentencing

II. THE COURT OF APPEALS

FASHIONED UNPRECEDENTED STANDARDS

OF PROOF WHICH FORECLOSE ALL

MEANINGFUL REVIEW OF RACIAL

i

1

2

2

2

2

7

18

23

32

32

41

iii

DISCRIMINATION IN CAPITAL

SENTENCING PROCEEDINGS .......... 45

A. The Court of Appeals

Ignored This Court's

Decisions Delineating

A Party's Prima Facie

Burden Of Proof Under

The Equal Protection

Clause 47

B. The Court of Appeals

Disregarded This

Court's Teachings On

The Proper Role Of

Statistical Evidence

In Proving Intentional

Discrimination . . . . 64

C. The Court Of Appeals

Erroneously Held That

Even Proven

Patterns Of Racial

Discrimination Will

Not Violate The

Constitution Unless

Racial Disparities Are

Of Large Magnitude ... 77

D. The Court Of Appeals

Erred in Demanding

Proof of "Specific

Intent To

Discriminate" As A

Necessary Element Of

An Eighth Amendment

C l a i m .............. 97

III. THE COURT SHOULD EITHER GRANT

PETITIONER RELIEF OR REMAND THE CASE

TO THE COURT OF APPEALS FOR FURTHER

CONSIDERATION UNDER APPROPRIATE LEGAL

STANDARDS........................ 104

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Pages

Alabama v. Evans,

461 U.S. 230 ( 1983)............ 95

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S.

625 ( 1972)................... 47,48

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S.

559 (1953).................... 76

Ballew v. Georgia,

435 U.S. 223 ( 1978)............ 84

Batson v. Kentucky, ___U.S.__,

90 L.Ed. 2d 69

( 1986)........... 24,26,27,33,47,74

Bazemore v. Friday, ___U.S___,

___ L.Ed. 2d___ "

(1986) 27,29,64,73,75,78,106

Briscoe v. Lahue,

460 U.S. 325 (1983)............ 38

Brown v. Board of Education,

346 U.S. 483 ( 1954).......... 32

Castaneda v. Partida,

430 U.S. 482

( 1977)........... 27,49,56,65,73,79

Chapman v. California,

386 U.S. 18 ( 1967)............. 108

Cleveland Board of Education v.

LaFleur, 414 U.S. 632 (1974)...39,44

vi

Coble v. Hot Springs School District

No.6, 682 F. 2d 721 (8th

Cir . 1982 )..................... 66

Eastland v. TVA,

704 F. 2d 613 (11th Cir. 1983).. 66

Eddings v. Oklahoma,

455 U.S. 104 ( 1982)............ 98

EEOC v. Ball Corp.,

661 F. 2d 531 (6th Cir. 1981)... 66

Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238

(1972)............ 24,31,41,97,107

Gardner v. Florida,

430 U.S. 349 (1977)....... 44,98,99

General Building Contractors Ass'n,

Inc. v. Pennsylvania, 458 U.S.

375 ( 1983)..................... 34

Giglio v. United States,

405 U.S. 150 ( 1972)............ 4

Godfrey v. Georgia,

446 U.S. 420

(1980)............ 25,31,42,57,98

Graves v. Barnes,

405 U.S. 1201 ( 1972)........... 95

Gregg v. Georgia,

428 U.S. 153

( 1976)......... 25,40,4 2,57,59,89,98

Hazelwood School District v. United

States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977).... 65

Ho Ah Kow v. Nunan, 12 Fed. Cas. 252

(No. 6546) (C.C. D. Cal. 1879).. 34

vii

Hunter v. Underwood, ___U.S.___,

85 L. Ed, 2d 222

(1985)................... 33,60,91

Jones v. Georgia,

389 U.S. 24 ( 1967)............. 48

Loving v. Virginia,

388 U.S. 1 ( 1967).............. 35

Lyons v. Oklahoma,

322 U.S. 596 ( 1944)............ 108

McClesky v. State, 245 Ga. 108, 263

S.E. 2d 14, cert, denied, 449

U.S. 891 ( 1980)................ 5

McCleskey v. Zant,

454 U.S. 1093 ( 1981)........... 6

McLaughlin v. Florida,

379 U.S. 184

(1964).................. 34,35,39

Mt. Healthy City Board of Educ. v.

Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977)...107,108

Neal v. Delaware, 100 U.S. 370

( 1881)......................... 49

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536

(1927)......................... 33

Papasan v. Allain, ___U.S.___,

___L. Ed. 2d__(1986)....... 29,78

Parker v. North Carolina,

397 U.S. 790 ( 1970)............ 108

Patton v. Mississippi,

332 U.S. 463 (1947)............ 76

Personnel Administrator of

Massachusetts v. Feeney,

viii

442 U.S. 256

(1976)..... 35,74

Rhodes v. Chapman, 452 U.S. 337

( 1981 )......................... 99

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113

(1973).... 39,43

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613

(1982)...................... 50,60

Rose v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545

( 1979)......................... 33

Rozecki v. Gaughan,

459 F. 2d 6 (1st Cir. 1972)..... 99

Segar v. Smith, 738 F. 2d 1249

(D.C. Cir. 1984)............ 66,76

Skinner v. Oklahoma,

316 U.S. 535 ( 1942)............ 39

Skipper v. South Carolina, ___U.S.

, 90 L. Ed. 2d 1 ( 1986)...... 104

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128

( 1940)..................... 32,45

Spain v. Procunier, 600 F. 2d 189

(9th Cir. 1979)................ 99

Stanley v. Illinois,

405 U.S. 645 (1972)......... 39,44

Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303 (1880)......... 34,41

Sullivan v. Wainwright, 464 U.S. 109,

(1983)......................... 93

Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324 ( 1977)........... 65

ix

Texas Dep't of Community Affairs v.

Burdine, 450 U.S . 248

(1981)......... ...... 29,48,75,

Turner v. Murray, U.S .

90 L. Ed. 2d 27

(1986)......... 24,33,56,76,1

Vasquez v. Hillery, U.S.

88 L. Ed. 2d 598

(1986)........................

Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Development

Corp., 429 U.S. 252

(1977)................ 28,50,52,

Vuyanich v. Republic National Bank,

505 F. Supp. 224 (N.D. Tex.

1980) vacated on other grounds,

732 F. 2d 1195 (5th Cir.1984)...

Wainwright v. Adams, 466 U.S. 964

(1984).........................

Wainwright v. Ford, 467 U.S. 1220

(1984).........................

Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229

(1976)............. 27,32,47,49,

Wayte v. United States, ___U.S.___,

84 L. Ed. 2d 547 (1985)........

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545

( 1967 )....................... 47 ,

Wilkins v. University of Houston,

654 F. 2d 388 (5th Cir. 1981),

vacated and remanded on other

grounds, 459 U.S. 809 (1982)....

76

03

24

59

66

93

93

74

49

56

66

X

Wolfe v. Georgia Ry. & Elec. Co.,

2 Ga. App. 499, ___, 58 S.E. 899

(1907)....................... 61

Wong Sun v. United States,

371 U.S. 471 ( 1963)......... 108

Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U.S. 356 (1886).........33,56

Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862

(1983).......................43,57

Zant v. Stephens, 456 U.S. 410

(1982) (per curiam).......... 43

Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 1254 (1)............ 2

28 U.S.C. § 2241 (c) (3)......... 106

Rule 406, F. Rule Evid............. 72

Former Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2534.1

(b)(2)....................... 5

Former Ga. Code Ann. § 27-2534.1

(b)(8)....................... 5

Other Authorities

D. Baldus & J. Cole, Statistical

Proof of Discrimination (1980).. 8

Baldus, Pulaski & Woodworth,

Arbitrariness and Discrimination

in the Administration of the

xi

Death Penalty: A Challenge to State

Supreme Courts, 15 Stetson L.

Rev. 133 ( 1986)............... 8

Baldus, Pulaski & Woodworth,

Comparative Review of Death

Sentences: An Empirical Study of

the Georgia Experience, 74 J.

Crim. Law & Criminology 661

(1983)...................... ; . . 8

Baldus, Pulaski, Woodworth & Kyle,

Identifying Comparatively

Excessive Sentences of Death: A

Quantitative Approach, 33 Stan.

L. Rev. 1 ( 1977)............. 8

Baldus, Woodworth & Pulaski,

Monitoring and Evaluating

Contemporary Death Sentencing

Systems: Lessons from Georgia,

18 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1375

(1985)......................... 8

Barnett, Some Distribution Patterns

for the Georgia Death Sentence,

18 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1327

( 1985)......................... 51

Bentele, The Death Penalty in Georgia:

Still Arbitrary, 61 Wash. U.L.Q.

573 (1985)..................... 59

Bowers & Pierce, Arbitrariness and

Discrimination Under Post-Furman

Capital Statutes, 26 Crime &

Delinq. 563 ( 1980).............. 51

Finkelstein, The Judicial Reception of

Multiple Regression Studies in Race

and Sex Discrimination Cases, 80

Colum. L. Rev. 737 (1980)....... 66

Fisher, Multiple Regression in Legal

xii

Proceedings, 80 Colum. L. Rev. 737

(1980).......................... 66

Gross, Race and Death: The Judicial

Evaluation of Evidence of

Discrimination in Capital

Sentencing, 18 U.C. Davis L. Rev.

1275 ( 1985)................... 81,90

Gross & Mauro, Patterns of Death:

Disparities in Capital Sentencing

and Homicide Victimization, 37

Stan. L. Rev. 27 (1985).... 51

H. Kalven & H. Zeisel, The American

Jury (1966 ).................... 84

B. Nakell & K. Hardy,

The Arbitrariness of the Death

Penalty, (1986)

(forthcoming)................. 100

Report of the Joint Committee on

Reconstruction at the First

Session, Thirty-Ninth Congress,

( 1866)......................... 37

Statement of Rep. Thaddeus Stevens,

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st

Sess. 2459 (1966); Accord,

statement of Sen. Pollard, Cong.

Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess.

2961 ( 1866).................... 37

Wolfgang & Riedel, Race, Judicial

Discretion and the Death Penalty,

407 Annals 119 (May 1973)...... 51

Wolfgang & Riedel, Race, Rape, and the

Death Penalty in Georgia, 45 Am. J.

Orthopsychiat. 658 (1975)...... 51

xiii

No. 84-6811

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1985

WARREN McCLESKEY,

Petitioner,

- v. -

RALPH M. KEMP, Superintendent,

Georgia Diagnostic &

Classification Center.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for

the Eleventh Circuit

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Eleventh

Circuit is reported at 753 F .2d 877

(11th Cir. 1985)(en banc). The opinion

of the United States District Court for

the Northern District of Georgia is

reported at 580 F. Supp. 338 (N.D. Ga.

1984) .

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals

was entered on January 29, 1985. A

timely motion for rehearing was denied

on March 26, 1985. The Court granted

certiorari on July 7, 1986. The

jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

CONSTITUTIONAL

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the Eighth and

the Fourteenth Amendments to the

Constitution of the United States.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Course of Proceedings

Petitioner Warren McCleskey is a

young black man who was tried in the

Superior Court of Fulton County,

Georgia, for the murder of a white

police officer, Frank Schlatt. The

homicide occurred on May 13, 1978 during

an armed robbery of the Dixie Furniture

2

Store in Atlanta. In a statement to

police, petitioner admitted that he had

been present during the robbery, but he

denied that he had fired the shot that

killed Officer Schlatt. (Tr.T. 453).1

Petitioner was tried by a jury

comprised of eleven whites and one

black. (Fed.Tr.1316). The State's case

rested principally upon certain disputed

forensic and other circumstantial

evidence suggesting that petitioner may

have fired the murder weapon, and upon

1 Each reference to the trial

transcript will be indicated by the

abbreviation "Tr.T," and to the

federal habeas corpus transcript, by the

abbreviation "Fed.Tr."

References to the Joint Appendix

will be indicated by the abbreviation

"J.A." and to the Supplemental Exhibits,

by "S.E." Petitioner's exhibits

submitted to the District Court during

the federal hearing were identified

throughout the proceedings by the

initials of the witness during whose

testimony they were introduced, followed

by an exhibit number. For example, the

first exhibit introduced during the

testimony of Professor David Baldus was

designated "DB 1."

3

purported

defendant

Evans. 2

confessions made to a co-

and to a cellmate. Offie

2 The co-defendant, Ben Wright, had

a possible personal motive to shift

responsibility from himself to

petitioner. Inmate Evans testified

without any apparent self-interest that

petitioner had boasted to him in the

cell about shooting Officer Schlatt.

However, the District Court later found

that Evans had concealed from

petitioner's jury a detective's promise

of favorable treatment concerning

pending federal charges. Holding that

this promise was "within the scope of

Giqlio [v. United States, 405 U.S. 150

(1972)]," (J .A . ), the District Court

granted petitioner habeas corpus relief:

"[G]iven the circumstantial nature of

the evidence that McCleskey was the

triggerman who killed Officer Schlatt

and the damaging nature of Evans'

testimony as to this issue and the issue

of malice . . . the jury may reasonably

have reached a different verdict on the

charge of malice murder had the promise

of favorable treatment been disclosed."

(J.A . ).

The Court of Appeals reversed,

holding that the detective's promises to

witness Evans were insufficiently

substantial to require full disclosure

under Giglio, and that any errors in

concealing the promises were harmless.

(J.A. ). Five judges dissented,

contending that Giqlio had plainly been

violated; four of the five also believed

that the concealed promise was not

4

The jury convicted petitioner on all

charges. Following the penalty phase,

it returned

aggravating

recommending

a verdict finding two

circumstances * 3 and

a sentence of death. On

October 12, 1978, the Superior Court

imposed a death sentence for murder and

life sentences for armed robbery. (J.A.)

After his convictions and sentences

had been affirmed on direct appeal,

McClesky v. State, 245 Ga. 108, 263

S.E.2d 146, cert, denied, 449 U.S. 891

(1980), petitioner filed a petition for

habeas corpus in the Superior Court of

Butts County, alleging, inter alia, that

harmless. (J.A. ) (Godbold, Ch.J.,

dissenting in part); id. at (Kravitch,

J., concurring).

3 The jury found that the murder

had been committed during an armed

robbery, former Ga. Code Ann. § 27-

2534.1(b)(2)(current version O.C.G.A. §

17-10-30(b)(2)), and that it had been

committed against a police officer.

Former Ga. Code Ann. § 27-

2534.1(b)(8)(current version O.C.G.A. §

17-10-30(b)(8)).

5

he had been condemned pursuant to

capital statutes which were being

"applied arbitrarily, capriciously and

whimsically" in violation of the Eighth

Amendment (State Habeas Petition, SI 10),

and in a "pattern . . . to discriminate

intentionally and purposefully on

grounds of race," in violation of the

Equal Protection Clause. (Id. SI 11).

The Superior Court denied relief on

April 8, 1981.

After unsuccessfully seeking review

from the Supreme Court of Georgia and

this Court, see McCleskey v. Zant, 454

U.S. 1093 (1981)(denying certiorari),

petitioner filed a federal habeas corpus

petition reasserting his claims of

systemic racial discrimination and

arbitrariness. (Fed. Habeas Pet. SHI 45-

50; 51-53). The District Court held an

evidentiary hearing on these claims in

August of 1983.

6

The evidence presented by petitioner

at the federal hearing is integrally

related to the issues now on certiorari.

In the next section, we will summarize

that evidence briefly; fuller discussion

will be included with the legal

arguments as it becomes relevant.̂

B. Petitioner's Evidence of Racial

Discrimination: The Baldus Studies

Petitioner's principal witness at

the federal habeas hearing was

Professor David C. Baldus, one of the

nation's leading experts on the legal 4

4 Discussion of the research

design of the Baldus studies appears at

pp. 50-55 infra. Statistical methods

used by Professor Baldus and his

colleagues are described at pp. 66-71.

The principal findings are reviewed at

pp. 80-89.

A more detailed description of

the research methodology of the Baldus

studies — including study design,

questionnaire construction, data

sources, data collection methods, and

methods of statistical analysis — can

be found in Appendix E to the Petition

for Certiorari, McCleskey v. Kemp, No.

84-6811.

7

use of statistical evidence. 5

Professor Baldus testified concerning

two meticulous and comprehensive studies

he had undertaken with Dr. George

Woodworth.5 6 and Professor Charles

5 Professor Baldus is the co

author of an authoritative text in the

field, D.Baldus & J. Cole, Statistical

Proof of Discrimination (1980), as well

as a number of law review articles

relevant to his testimony in this case.

Baldus, Pulaski, Woodworth & Kyle,

Identifying____Comparatively Excessive

Sentences of Death, 33 Stan. L. Rev. 601

(1980); Baldus, Pulaski & Woodworth,

Comparative Review of Death Sentences:

An Empirical Study of the Georgia

Experience, 74 J. Crim. Law &

Criminology 661 (1983); Baldus,

Woodworth & Pulaski, Monitoring and

Evaluating Contemporary Death Sentencing

Systems: Lessons From Georgia, 18 U.C.

Davis L. Rev. 1374 (1985); Baldus,

Pulaski & Woodworth, Arbitrariness and

Discrimination in the Administration of

the Death Penalty: A Challenge to State

Supreme Courts, 15 Stetson L. Rev. 133

(1986).

6 Dr. Woodworth is Associate

Professor of Statistics at the

University of Iowa and the founder of

Iowa's Statistical Consulting Center.

(Fed.Tr.1203-04). He has consulted on

statistical techniques for over eighty

empirical studies (id. 1203-04) and has

taught and written widely on statistical

issues. (GW 1).

3

Pulaski.7 Professor Baldus explained

that he had undertaken the studies to

examine Georgia's capital sentencing

experience under its post-Furman

statutes. The studies drew from a

remarkable variety of official records

on Georgia defendants convicted of

murder and voluntary manslaughter, to

which Professor Baldus obtained access

through the cooperation of the Georgia

Supreme Court, the Georgia Board of 7

7 Professor Charles A. Pulaski,

Jr., is Professor of Law at Arizona

State University College of Law,

specializing in criminal procedure.

Professor Pulaski did not testify during

the federal hearing.

Petitioner also presented expert

testimony from Dr. Richard A. Berk,

Professor of Sociology and Director of

the Social Process Research Institute at

the University of California at Santa

Barbara, and a nationally prominent

expert on research methodology,

especially in the area of criminal

justice research. He was a member of

the National Academy of Sciences'

Committee on Sentencing Research. Dr.

Berk gave testimony evaluating the

appropriateness of Baldus' method and

the significance of his findings.

9

Pardons and Paroles, and other state

agencies. These records included not

only trial transcripts and appellate

briefs but also detailed parole board

records, prison files, police reports

and other official documents. (S.E. 43).

Using a carefully tailored

questionnaire, Professor Baldus gathered

over five hundred items of information

on each case concerning the defendant,

the victim, the crime, the aggravating

and mitigating circumstances, and the

strength of the evidence. In addition,

the Baldus questionnaire required

researchers to prepare a narrative

summary to capture individual features

of each case. The full questionnaire

appears as DB 38 in the Supplemental

Exhibits. (S.E. 1-42). Employing

generally accepted data collection

methods at each step, Professor Baldus

cross-checked the accuracy of the data

10

both manually and by computer-aided

systems. (Fed.Tr.585-616).

Professor Baldus found that during

the 1973-1979 period, 2484 murders and

non-negligent manslaughters occurred in

the State of Georgia. Approximately

1665 of those involved black defendants;

819 involved white defendants. Blacks

were the victims of homicides in

approximately 61 percent of the cases,

whites in 39 percent. When Professor

Baldus began to examine the State's

subsequent charging and sentencing

patterns, however, he found that the

racial proportions were heavily

inverted. Among the 128 cases in which

a death sentence was imposed, 108 or Ql%

involved white victims. As exhibit DB

62 demonstrates, white victim cases were

nearly eleven times more likely to

receive a sentence of death than were

black victim cases. (S.E. 46). When the

11

cases were further subdivided by race of

defendant. Professor Baldus discovered

that 22 percent of black defendants in

Georgia who murdered whites were

sentenced to death, while scarcely 3

percent of white defendants who murdered

blacks faced a capital sentence. (S.E.

47) .

These unexplained racial disparities

prompted Professors Baldus and Woodworth

to undertake an exhaustive statistical

inquiry. They first defined hundreds of

variables, each capturing a single

feature of the cases.8 Using various

statistical models, each comprised of

selected groups of different variables

(see Fed. Tr. 689-705), Baldus and

Woodworth tested whether other

8 For example, one variable might

be defined to reflect whether a case was

characterized by the presence or absence

of a statutory aggravating circumstance,

such as the murder of a police victim.

(See Fed.Tr.617-22).

12

characteristics of Georgia homicide

cases might suffice to explain the

racial disparities they had observed.

Through the use of multiple regression

analysis, Baldus and Woodworth were able

to measure the independent impact of the

racial factors while simultaneously

taking into account or controlling for

more than two hundred aggravating and

mitigating factors, strength of evidence

factors, and other legitimate sentencing

considerations. (See. e.q., S.E. 51).

Professors Baldus and Woodworth

subjected the data to a wide variety of

statistical procedures, including cross-

tabular comparisons, weighted and

unweighted least-squares regressions,

logistic regressions, index methods,

cohort studies and other appropriate

scientific techniques. Yet regardless

of which of these analytical tools

Baldus and Woodworth brought to bear,

13

race held firm as a prominent determiner

of life or death. Race proved no less

significant in determining the

likelihood of a death sentence than

aggravating circumstances such as

whether the defendant had a prior murder

conviction or whether he was the prime

mover in the homicide. (S.E. 50).

Indeed, Professor Baldus testified that

his best statistical model, which

"captured the essence of [the Georgia] .

. . system" (Fed.Tr.808), revealed that

after taking into account most

legitimate reasons for sentencing

distinctions, the odds of receiving a

death sentence were still more than 4.3

times greater for those whose victims

were white than for those whose victims

were black. (Fed.Tr. 818; DB 82).

Focusing directly on petitioner's case,

Baldus and his colleagues estimated that

for homicide cases "at Mr. McCleskey's

14

level of aggravation the average white

victim case has approximately a twenty

[20] percentage point higher risk of

receiving a death sentence than a

similarly situated black victim case."

(Id. 1740).9 Professor Baldus also

testified that black defendants whose

victims were white were significantly

more likely to receive death sentences

than were white defendants, especially

among cases of the general nature of

9 These figures represent a

twenty percentage point, not a twenty

percent, increase in the likelihood of

death. Among those cases where the

average death-sentencing rate is .24 or

24-in-100, the white-victim rate would

be approximately .34 or 34-in-100, the

black-victim rate, only .14, or 14-in-

100. This means that the sentencing rate

in white victim cases would be over

twice as high (.34 vs. .14) as in black

victim cases. Thus, on the average,

among every 34 Georgia defendants

sentenced to death at this level of

aggravation for the murders of whites,

20 would likely not have received a

death sentence had their victims been black.

15

petitioner's. (Fed. Hab. Tr. 863-64).

Professor Baldus demonstrated that

this "dual system" of capital sentencing

was fully at work in Fulton County where

petitioner had been tried and sentenced

to death. Not only did county

statistical patterns replicate the

statewide trends, but several non-

statistical comparisons of Fulton County

cases further emphasized the importance

of race. For example, among those 17

defendants who had been charged with

homicides of Fulton County police

officers between 1973 and 1980, only

one defendant other than petitioner had

even received a penalty trial. In that

case, where the victim was black, a life

sentence was imposed. (Fed.Tr.1050-62).

The State of Georgia produced little

affirmative evidence to rebut

petitioner's case. It offered no

alternative model that might have

16

reduced or eliminated the racial

variables. (Fed. Tr. 1609). It did not

even propose, much less test the effect

of, additional factors concerning

Georgia crimes, defendants or victims,

admitting that it did not know whether

such factors "would have any effect or

not." (Id. 1569). The State expressly

declined Professor Baldus's offer,

during the hearing, to employ

statistical procedures of the State's

choice in order to calculate the effect

of any factors the State might choose to

designate and to see whether the racial

effects might be eliminated. 10

Instead, the State simply attacked

10 The District Court did accept

Professor Baldus's invitation and

designated a statistical model it

believed would most accurately capture

the forces at work in Georgia's capital

sentencing system. (Fed. Tr. 810; 1426;

1475-76; 1800-03; Court's Exhibit 1).

After analyzing this model, Professor

Baldus reported that it did nothing to

diminish the racial disparities. (See R.

731-52) .

17

the integrity of Professor Baldus1s data

sources (see Fed. Tr. 1380-1447), its

own official records. It also presented

one hypothesis, that the apparent racial

disparities could be explained by the

generally more aggravated nature of

white victim cases. The State's

principal expert never tested that

hypothesis by any accepted statistical

techniques (id. 1760-61), although he

admitted that such a test "would . .

.[have been] desirable." (Id. 1613).

Professors Baldus and Woodworth did test

the hypothesis and testified

conclusively on rebuttal that it could

not explain the racial disparities.

(Fed.Tr.1290-97; 1729-32; GW 5-8).

C. The Decisions Below

The District Court rejected

petitioner's claims. It faulted

petitioner's extraordinary data sources

because they had "not capture[d] every

18

nuance of every issue." (J.A. ). The

extensive Parole Board records, the

court complained, "present a

retrospective view of the facts and

circumstances . . . after all

investigation is completed, after all

pretrial preparation is made." (J.A. ).

Since such files, the court reasoned,

did not measure the precise quanta of

information available to each decision

maker — police, prosecutor, judge, jury

— at the exact moment when different

decisions about the case were made, "the

data base . . i s substantially

flawed." (Id.) As a related matter,

the District Court insisted that all of

Professor Baldus's statistical models of

the Georgia system -- even those

employing more than 230 separate

variables — were "insufficiently

predictive" since they did not include

every conceivable variable and could not

19

predict every case outcome. (J.A. ).

The District Court ended its opinion

by rejecting the legal utility of such

statistical methods altogether:

[M]ultivariate analysis is ill

suited to provide the court with

circumstantial evidence of the

presence of discrimination, and

it is incapable of providing the

court with measures of

qualitative difference in

treatment which are necessary to

a finding that a prima facie

case has been established . . .

To the extent that McCleskey

contends that he was denied . .

. equal protection of the law,

his methods fail to contribute

anything of value to his cause.

(J.A. )(italics omitted).

The majority of the Court of Appeals

chose not to rest its decision on these

findings by the District Court; instead

it expressly "assum[ed] the validity of

the research" and "that it proves what

it claims to prove." (J.A. ). Yet the

Court proceeded to announce novel

standards of proof that foreclose any

meaningful review of racial claims like

20

petitioner's. As its baseline, the

Court held that statistical proof of

racial disparities must be "sufficient

to compel a conclusion that it results

from discriminatory intent and purpose."

{J .A . ) (emphasis added).

"[S]tatistical evidence of racially

disproportionate impact [must be] . . .

so strong as to permit no inference

other than that the results are the

product of a racially discriminatory

intent or purpose." (J.A. ). The Court

also announced that even unquestioned

proof of racially discriminatory

sentencing results would not suffice to

make out an Equal Protection Clause

violation unless the racial disparities

were of sufficient magnitude: "The key

to the problems lies in the principle

that the proof, no matter how strong, of

some disparity is alone insufficient."

(J.A. ). "In any discretionary system,

21

some imprecision must be tolerated," the

Court stated, and petitioner's proven

racial disparities were "simply

insufficient to support a ruling . . .

that racial factors are playing a role

in the outcome sufficient to render the

system as a whole arbitrary and

capricious." (J.A. ). Finally, the

majority held that no Eighth Amendment

challenge based upon race could succeed

absent similar proof of purposeful State

conduct. Although "cruel and unusual

punishment cases do not normally focus

on the intent of the government actor .

. . where racial discrimination is

claimed . . . their purpose, intent and

motive are a natural component of the

proof" (J.A. ) and "proof of a disparate

impact alone is insufficient

unless . . . it compels a conclusion

that . . . race is intentionally being

used as a factor in sentencing." Id.

22

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The principal questions before the

Court on certiorari involve intermediate

issues of evidence and proof.

Fundamental constitutional values are

nonetheless at the heart of this appeal.

Our primary submission is that the lower

courts, by their treatment of

petitioner's evidence, have effectively

placed claims of racial discrimination

in the death penalty — no matter how

thoroughly proven — beyond effective

judicial review. To appreciate the

impact of the lower court's holding, it

is necessary at the outset to recall the

constitutional values at stake.

This country has, for several

decades, been engaged in a profound

national struggle to rid its public life

of the lingering influence of official,

state-sanctioned racial discrimination.

The Court has been especially vigilant

23

to prevent racial bias from weighing in

the scales of criminal justice. See,

e.q., Batson v. Kentucky, __U.S.__, 90

L.Ed.2d 69 (1986); Turner v. Murray,

__U.S.__, 90 L .Ed.2d 27, 35 (1986);

Vasquez v. Hillery, __U.S.__, 88

L.Ed.2d 598 (1986). A commitment

against racial discrimination was among

the concerns that led the Court to

scrutinize long-entrenched capital

sentencing practices and to strike down

statutes that permitted arbitrary or

discriminatory enforcement of the death

penalty. See, e.q., Furman v. Georgia,

408 U.S. 238 (1972).

In 1976, reviewing Georgia's then

new post-Furman capital statutes, the

Court declined to assume that the

revised sentencing procedures would

inevitably fail in their purpose to

eliminate "the arbitrariness and

capriciousness condemned by Furman."

24

153, 198Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S.

(1976)(opinion of Stewart, Powell &

Stevens, J.J.). Accord, id. at 220-26

(opinion of White, J.); see also

Godfrey v. Georgia, 446 U.S. 420, 428

(1980). It was appropriate at that time

for the Court to clothe Georgia's new

statutes with a strong presumption of

constitutionality — to assume,

"[a]bsent facts to the contrary," Gregg

v. Georgia, 428 U.S. at 225 (opinion of

White, J.), that its statutes would be

administered constitutionally: to reject

"the naked assertion that the effort is

bound to fail." Id. at 222. Yet the

presumption extended to Georgia in 1976

was not — and under the Constitution

could never have been — an irrevocable

license to carry out capital punishment

arbitrarily and discriminatorily in

practice.

Petitioner McCleskey has now

25

presented comprehensive evidence to the

lower courts that Georgia's post-Furman

experiment has failed, and that its

capital sentencing system continues to

be haunted by widespread and substantial

racial bias.

Faced with this overwhelming

evidence, the Court of Appeals took a

wrong turn. It accorded Georgia's

death-sentencing statutes what amounts

to an irrebuttable presumption of

validity, one no capital defendant could

ever overcome. It did so through a

series of rulings that "placed on

defendants a crippling burden of proof."

Batson v. Kentucky, 90 L.Ed.2d at 85.

Henceforth, a capital defendant, rather

than proving a prima facie case of

discrimination by demonstrating the

presence of substantial racial

disparities within a system "susceptible

of abuse" — thereby shifting the

26

burden of explanation to the State, see,

e.q., Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S.

482, 494-495 (1977); Washington v.

Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 241 (1976); Batson

v. Kentucky, supra — must present proof

so strong that it "permits no inference

other than . . . racially discriminatory

intent." No room is left in this

formulation for proof by ordinary fact

finding processes. Instead, a capital

defendant must anticipate and exclude at

the outset "every possible factor that

might make a difference between crimes

and defendants, exclusive of race."

(J.A. ).

This new standard for proof of

racial discrimination has no precedent

in the Court's teachings under the

Equal Protection Clause; it is contrary

to everything stated or implied in

Batson v. Kentucky, supra; Bazemore v.

Friday, __U.S.__, __L.Ed.2d__ (1986);

27

Arlington____Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252

(1977), and a host of the Court's

decisions expounding the principle of a

prima facie case.

Compounding the Court of Appeals'

new standard is the burden it imposed

upon statistical modes of proof, which

virtually forecloses any demonstration

of discriminatory capital sentencing by

means of scientific evidence. To be

sufficient, a statistical case must

address not only the recognized major

sentencing determinants, but also a host

of hypothetical factors, conjectured by

the Court, whose systematic relation to

demonstrated racial disparities is

dubious to say the least. (See J.A. )

This cannot be the law, unless there is

to be a "death penalty exception" to the

Equal Protection Clause. Just last Term,

the Court unanimously held that such a

28

approach torestrictive judicial

statistical evidence was unacceptable

error. Bazemore v. Friday, __L.Ed.2d at

(1986). See also Texas Department of

Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S.

248, 252 (1981) .

The Court of Appeals also concluded

that even proven, persistent racial

disparities in capital sentencing are

constitutionally irrelevant unless their

magnitude is great. This holding strays

far from the Constitution and the

record. The Equal Protection Clause

protects individuals against a little

state-sanctioned racial discrimination

as well as a lot; the law does not

permit a State to use the death penalty

infrequently, or discriminate when it

does, and defend by saying that this

discrimination is rare. Only last Term,

in Papasan____v. Allain, __U.S.__,

_L.Ed.2d __ (1986), the Court expressly

29

declined to apply "some sort of

threshold level of effect . . . before

the Equal Protection Clause's strictures

become binding."

In any event, the Court of Appeals

plainly misconceived the facts as much

as the law on this issue. As we will

show, one central flaw pervading its

decision was a serious misapprehension

of the degree to which race played a

part in Georgia's capital sentencing

system from 1973 through 1979.

Finally, the court announced that,

henceforth, in a capital case, proof of

"purposeful discrimination will be a

necessary component of any Eighth

Amendment claim alleging racial

discrimination. Such a rule contradicts

both precedent and principle. Under the

Eighth Amendment, this Court has held

that it is the State's obligation "to

tailor and apply its laws in a manner

30

that avoids the arbitrary and capricious

infliction of the death penalty."

Godfrey v. Georgia, 446 U.S. 420, 428

(1980). The federal task in reviewing

the administration of those laws "is not

restricted to an effort to divine what

motives impelled the[] death penalties,"

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. at 253

(Douglas, J., concurring), but, having

"put to one side" the issue of

intentional discrimination, id. at 310

(Stewart, J., concurring), to discern

whether death sentences are "be[ing] . .

. wantonly and . . . freakishly

imposed." Id. at 312.

Reduced to its essence, petitioner's

submission to the Court is a simple one.

Evidence of racial discrimination that

would amply suffice if the stakes were a

job promotion, or the selection of a

jury, should not be disregarded when the

stakes are life and death. Methods of

31

proof and fact-finding accepted as

necessary in every other area of law

should not be jettisoned in this one.

I.

RACE IS AN INVIDIOUS AND UNCONSTITUTIONAL

CONSIDERATION IN CAPITAL SENTENCING

PROCEEDINGS

A. The Equal Protection Clause Of

The Fourteenth Amendment Forbids

Racial Discrimination In The

Administration Of Criminal Statutes

In the past century, few judicial

responsibilities have laid greater claim

on the moral and intellectual energies

of the Court than "the prevention of

official conduct discriminating on the

basis of race." Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. at 239. The Court has striven

to eliminate all forms of state-

sanctioned discrimination, "whether

accomplished ingeniously or

ingenuously." Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S.

128, 132 (1940). It has forbidden

discrimination required by statute, see,

e.q ., Brown v. Board of Education, 346

32

U.S. 483 {1954); Nixon v. Herndon, 273

U.S. 536 (1927), and has not hesitated

to "look beyond the face of . . . [a]

statute . . . where the procedures

implementing a neutral statute operate .

. . on racial grounds." Batson v.

Kentucky, 90 L.Ed.2d at 82; Turner v.

Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970); Yick Mo v.

Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 373-74 (1886).

The Court has repeatedly emphasized

that "the core of the Fourteenth

Amendment is the prevention of

meaningful and unjustified official

distinctions based on race." Hunter v.

Erickson, 393 U.S. 385, 391 (1969). In

the area of criminal justice, where

racial discrimination "strikes at the

fundamental values of our judicial

system and our society as a whole," Rose

v. Mitchell, 443 U.S. 545, 556 (1979),

the Court has "consistently" articulated

a "strong policy . . . of combating

33

racial discrimination." ^d* at 558.

One of the most obvious forms that

such discrimination can take in the

criminal law is a systematically unequal

treatment of defendants based upon their

race. See McLaughlin v. Florida, 379

U.S. 184, 190 n.8 (1964), citing

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303,

306-08 (1880); Ho Ah Kow v. Nunan, 12

Fed. Cas. 252 (No. 6546)(C .C.D .Cal.

1879). Certainly, among the evils that

ultimately prompted the enactment of the

Fourteenth Amendment and cognate post-

Civil War federal legislation were state

criminal statutes, including the

infamous Black Codes, which prescribed

harsher penalties for black persons than

for whites. See General Building

Contractors_____Ass 1 n . ,______ Inc ._____ v ■

Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 375, 386-87

34

( 1982).11 jn this case, Professor Baldus

has reported that the race of the

defendant — especially when the

defendant is black and the victim is

white — influences Georgia's capital

sentencing process. The State of

Georgia has disputed the truth of this

claim, but has offered no constitutional

defense if the claim is true. Georgia

has never articulated, or even

suggested, any "permissible state 11

11 The Court has accordingly

insisted "that racial classifications,

especially suspect in criminal statutes,

be subjected to the 'most rigid

scrutiny' and, if they are ever to be

upheld . . . be shown to be necessary

to the accomplishment of some

permissible state objective, independent

of the racial discrimination which it

was the object of the Fourteenth

Amendment to eliminate." Loving v.

Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 11 (1967). See

also____Personnel____Administrator____of

Massachusetts v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256,

272 (1979); cf. McLaughlin v. Florida,

379 U.S. at 198 ("I cannot conceive of a

valid legislative purpose under our

Constitution for a state law which makes

the color of a person's skin the test of

whether his conduct is a criminal

offense")(Stewart, J., concurring).

35

interest" that would justify the

disproportionate infliction of capital

punishment in a discriminatory fashion

against black defendants.

Nor has Georgia claimed any

constitutional warrant to execute

murderers of white citizens at a greater

rate than murderers of black citizens.

The history of the Equal Protection

Clause establishes that race-of-victim

discrimination was a major concern of

its Framers, just as Professor Baldus

has now found that it is a major feature

of Georgia's administration of the death

penalty. Following the Civil War and

immediately preceding the enactment of

the Fourteenth Amendment, Southern

authorities not only enacted statutes

that treated crimes committed against

black victims more leniently, but

frequently declined even to prosecute

persons who committed criminal acts

36

against blacks. When prosecutions did

occur, authorities often acquitted or

imposed disproportionately light

sentences on those guilty of crimes

against black persons. 12

The congressional hearings and

12 See, e.q.. Report of the Joint

Committee on Reconstruction, at the

First Session, Thirty-Ninth Congress,

Part II, at 25 (1866)(testimony of

George Tucker, commonwealth

attorney)(The southern people "have not

any idea of prosecuting white men for

offenses against colored people; they do

not appreciate the idea."); id. at 209

(testimony of Lt. Col Dexter Clapp)("Of

the thousand cases of murder, robbery,

and maltreatment of freedmen that have

come before me, . . . . I have never yet

known a single case in which the local

authorities or police or citizens made

any attempt or exhibited any inclination

to redress any of these wrongs or to

protect such persons."); id. at 213

(testimony of Lt. Col. J. Campbell);

id., Part III, at 141 (testimony of

Brevet M.J. Gen. Wagner Swayne)("I have

not known, after six months' residence

at the capital of the State, a single

instance of a white man being convicted

and hung r sic 1 or sent to the

penitentiary for crime against a negro,

while many cases of crime warranting

such punishment have been reported to

me."); id., Part IV, at 76-76 (testimony

of Maj. Gen. George Custer).

37

debates that led to enactment of the

Fourteenth Amendment are replete with

references to this pervasive race-of-

victim discrimination; the Amendment and

the enforcing legislation were intended,

in substantial part, to stop it. As the

Court recently concluded in Briscoe v.

Lahue, 460 U.S. 325, 338 (1983), "[i]t

is clear from the legislative debates

that, in the view of the . . . sponsors,

the victims of Klan outrages were

deprived of 'equal protection of the

laws' if the perpetrators systematically

went unpunished." See discussion in

Petition for Certiorari, McCleskey v.

Zant, No. 84-6811, at 5-7.

Even without reference to the

Amendment's history, race-of-victim

sentencing disparities violate long-

recognized equal protection principles

applicable to all forms of state action.

The Court has often held that whenever

38

either "fundamental rights" or "suspect

classifications" are involved, state

action "may be justified only by a

'compelling state interest1 . . . and .

. . legislative enactments must be

narrowly drawn to express only the

legitimate state interests at stake."

Roe v . Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 135 (1973);

see also Cleveland Board of Education v.

LaFleur, 414 U.S. 632 (1974); Stanley v.

Illinois, 405 U.S. 645 (1972).

Discrimination by the race of victim

not only implicates a capital

defendant's fundamental right to life,

cf. Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535,

541 (1942), but employs the paradigmatic

suspect classification, that of race. In

McLaughlin v. Florida, supra, the Court

examined a criminal statute which

singled out for separate prosecution

any black man who habitually occupied a

room at night with a white woman (or

39

vice versa) without being married. The

statute, in essence, prosecuted only

those of one race whose cohabiting

"victims" were of the other race.

Finding no rational justification for

this race-based incidence of the law,

the Court struck down the statute.

The discrimination proven in the

present case cannot be defended under

any level of Fourteenth Amendment

scrutiny. Systematically treating

killers of white victims more harshly

than killers of black victims can have

no constitutional justification. *3 This 13

13 The Court identified in Gregg

v. Georgia, 428 U.S. at 183-84 (1976),

at least two "legitimate governmental

objectives" for the death penalty—

retribution and deterrence. The Court

noted that the death penalty serves a

retributive purpose as an "expression of

society's moral outrage at particularly

offensive conduct." 428 U.S. at 183.

The race of the victim obviously has no

place as a factor in society's

expression of moral outrage. Similarly,

if the death penalty is meant to deter

capital crime, it ought to deter such

crime equally whether inflicted against

40

would set the seal of the state upon the

proposition that the lives of white

people are more highly valued than those

of black people — either an "assertion

of [the] . . . inferiority" of blacks,

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. at

308, or an irrational exercise of

governmental power in its most extreme

form.

B. The Eighth Amendment Prohibits

Racial Bias In Capital Sentencing

Petitioner McCleskey has invoked the

protection of a second constitutional

principle, drawn from the Eighth

Amendment. One clear concern of both the

concurring and dissenting Justices in

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972),

was the possible discriminatory

application of the death penalty at that

time. Justice Douglas concluded that

the capital statutes before him were

black or against white citizens.

41

"pregnant with discrimination," 408 U.S.

at 257, and thus ran directly counter to

"the desire for equality . . . reflected

in the ban against 'cruel and unusual

punishments' contained in the Eighth

Amendment." Id. at 255. Justice

Stewart lamented that "if any basis can

be discerned for the selection of these

few sentenced to die, it is the

constitutionally impermissible basis of

r a c e . T h e s e observations illuminate

the holding of Furman, reaffirmed by the

Court in Gregg and subsequent cases,

that the death penalty may "not be

imposed under sentencing procedures that

created a substantial risk that it

[will] . be inflicted in an

arbitrary and capricious manner." Gregg

v. Georgia, 428 U.S. at 188; Godfrey v. 14

14 See id. at 364-66 (Marshall,

J., concurring); cf. id. at 389 n.12

(Burger, C.J., dissenting); id. at 449-

50 (Powell, Jr., dissenting).

42

at 428; Zant v .Georgia, 446 U.S.

Stephens, 456 U.S. 410, 413 (1982)(per

curiam).

The Court itself suggested in Zant

v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862, 885 (1983),

that if "Georgia attached the

'aggravating'' label to factors that are

constitutionally impermissible or

totally irrelevant to the sentencing

process, such as . . . the race . . . of

the defendant . . . due process of law

would require that the jury's decision

to impose death be set aside." This

Eighth Amendment principle tracks the

general constitutional rule that, where

fundamental rights are at stake,

"legislative enactments must be narrowly

drawn to express only the legitimate

state interests at stake." Roe v . Wade,

410 U.S. at 155. Legislative

classifications that are unrelated to

any valid purpose of a statute are

43

arbitrary and violative of the Due

Process Clause Cleveland Board of

Education v. LaFleur, 414 U.S. 632

(1974); Stanley v. Illinois, 405 U.S.

645 (1972). A legislative decision to

inflict the uniquely harsh penalty of

death along the lines of such an

irrational classification would be still

more arbitrary under the heightened

Eighth Amendment standards of Furman.

Cf. Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349,

357-58, 361 (1977)(plurality opinion);

id. at 362-64 (opinion of White, J.).

And nothing could be more arbitrary

within the meaning of the Eighth

Amendment than a reliance upon race in

determining who should live and who

should die.

44

II.

THE COURT OF APPEALS FASHIONED

UNPRECEDENTED STANDARDS OF PROOF WHICH

FORECLOSE ALL MEANINGFUL REVIEW OF

RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN CAPITAL

SENTENCING PROCEEDINGS

The crucial errors of the Court of

Appeals involve the "crippling burden of

proof" it placed upon petitioner and any

future inmate who would seek the

protections of the Federal Constitution

against racial discrimination in capital

sentencing. "[E]qual protection to

all," the Court long ago observed, "must

be given — not merely promised." Smith

v . Texas, 311 U.S. at 130. The opinion

below was all promise, no give. It

held, in effect: You can escape being

judged by the color of your skin, and by

that of your victim, if (but only if)

you can survey and capture every

ineffable quality of every potentially

capital case, and if you then meet

standards for statistical analysis that

45

are elsewhere not demanded and nowhere

susceptible of attainment.

Judged by these standards, the

research of Professor Baldus—

described by Dr. Richard Berk as "far

and away the most complete and thorough

analysis of sentencing that's ever been

done" (Fed.Tr.1766) — is simply not

good enough. Nor would any future

studies be, absent evidence that

apparently must "exclud[e] every

possible factor that might make a

difference between crimes and

defendants, exclusive of race." (J.A.

). As we shall demonstrate in the

following subsections, these manifestly

are not appropriate legal standards of

proof. They depart radically from the

settled teachings of the Court. They

have no justification in policy or legal

principle, and they trivialize the

importance of Professor Baldus's real

46

and powerful racial findings.

A. The Court of Appeals Ignored This

Court's Decisions Delineating A Party's

Prima Facie Burden Of Proof Under The

Equal Protection Clause

(i) The Controlling Precedents

In Batson v. Kentucky, the Court

recently outlined the appropriate order

of proof under the Equal Protection

Clause. " [ I ] n any equal protection

case, 'the burden is, of course,' on the

defendant. . . 'to prove the existence

of purposeful discrimination.' Whitus v.

Georgia, 385 U.S. [545], at 550 [1967]

..." 90 L.Ed. 2d at 85. "[The

defendant] may make out a prima facie

case of purposeful discrimination by

showing that the totality of relevant

facts gives rise to an inference of

discriminatory purpose." Washington v.

Davis, [426 U.S.] at 239-242:"

Once the defendant makes the

requisite showing, the burden

shifts to the State to explain

adequately the racial exclusion.

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S.

47

[625], at 632 [(1972)]. The

State cannot meet this burden on

mere general assertions that its

officials did not discriminate

or that they properly performed

their duties. See Alexander v.

Louisiana, supra, at 632; Jones

v. Georgia, 389 U.S. 24, 25

(1967). Rather the State must

demonstrate that "permissible

racially neutral selection

criteria and procedures have

produced the . . . result."

90 L.Ed.2d 85-86.

The approach is "a traditional

feature of the common law," Texas Pep't

of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450

U.S. at 255 n.8, which, in the context

of discrimination litigation, requires a

complainant to "eliminate[] the most

common nondiscriminatory reasons for the

[observed facts]," id. at 254, and then

places a burden on the alleged wrongdoer

to show "a legitimate reason for" those

facts, _id. at 255, thereby

"progressively . . . sharpening] the

inquiry into the elusive factual

question of intentional discrimination."

48

Id. at 255 n.3.15

Although the initial showing of

race-based state action required depends

upon the nature of the claim and the

responsibilities of the state actors

involved, Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S.

at 253 (Stevens, J., concurring),

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 494-

95 (1977); cf. Wayte v. United States,

__U.S.__, 84 L .Ed.2d 547, 556 n.10

(1985), the guiding principle is that

courts must make "a sensitive inquiry

into such circumstantial and direct

evidence of intent as may be available." 15

15The roots of this approach run

back at least as far as Neal v.

Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 (1881), where the

Court refused to indulge a "violent

presumption," offered by the State of

Delaware to excuse the absence of black

jurors, that "the black race in Delaware

were utterly disqualified, by want of

intelligence, experience or moral

integrity to sit on juries." 103 U.S.

at 397. Absent proof to support its

contention, the State's unsupported

assertion was held insufficient to rebut

the prisoner's prima facie case. Id.

49

Village of____Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp.,

429 U.S. 252, 266 (1977). Accord,

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 618

(1982). Among the most important

factors identified by the Court as

probative have been (i) the racial

impact of the challenged action, (ii)

the existence of a system affording

substantial state discretion, and (iii)

a history of prior discrimination.

(ii) Petitioner's Evidence

The prima facie case presented by

petitioner exceeds every standard ever

announced by this Court for proof of

discrimination under the Equal

Protection Clause. The centerpiece of

the case, although not its only feature,

is the work of Professor Baldus and his

colleagues, who have examined in

remarkable detail the workings of

Georgia's capital statutes during the

50

first seven years of their

administration, from 1973 through 1979.

The Baldus studies are part of a body of

scientific research conducted both

before and after Furman that has

consistently reported racial

discrimination at work in Georgia's

capital sentencing system.16 Baldus1s

research reached the same conclusions as

the earlier studies, but there the

resemblance ends: his work is vastly

more detailed and comprehensive than any

prior sentencing study in Georgia or

16 see, Wolfgang & Riedel, Race,

Judicial Discretion and the Death

Penalty, 407 Annals 119 (1973); Wolfgang

& Riedel, Race, Rape and the Death

Penalty in____Georgia, 45 Am. J.

Orthopsychiat. 658 (1975); Bowers &

Pierce, Arbitrariness and Discrimination

Under Post-Furman Capital Statutes, 26

Crime & Deling. 563 (1980); Gross &

Mauro, Patterns of Death: An Analysis

of Racial Disparities in Capital

Sentencing and Homicide Victimization,

37 Stan. L. Rev. 27 (1984); Barnett,

Some Distribution Patterns for the

Georgia Death Sentence, 18 U.C. Davis L.

Rev. 1327 (1985).

51

elsewhere.

The Baldus research actually

comprised two overlapping studies: the

first, a more limited examination of

cases from 1973-1978 in which a murder

conviction had been obtained at trial

(Fed.Tr.170); the second, - a wide-

ranging study involving a sample of all

cases from 1973 through 1979 in which

defendants indicted for murder or

voluntary manslaughter had been

convicted and sentenced to prison. (Id.

263-65). Most of Baldus' findings in

this case are reported from the second

study.

a. The Racial Disparities

"The impact of the official action

— whether it 'bears more heavily on one

race than another' . . . — provide[s]

an important starting point." Arlington

Heights. 429 U.S. at 266. Here, the

Baldus studies reveal substantial,

52

unadjusted racial disparities: a death-

sentencing rate nearly eleven times

higher in white-victim cases than in

black-victim cases. (Fed.Tr.730-33; S.E.

46). Professor Baldus testified that

these figures standing alone did not

form the basis for his analysis,

because they offered no control for

potential legitimate explanations of the

observed racial differences. (Fed. Tr.

734).66

Professor Baldus thus began collecting

data on every non-racial factor

suggested as relevant by the literature,

the case law, or actors in the criminal

justice system. His final

questionnaires sought information on

over 500 items related to each case

studied. (Fed.Tr.278-92; S.E. 1-42).

After collecting this vast

storehouse of data, Professor Baldus and

his colleagues conducted an exhaustive

53

series of analyses, involving the

application of increasingly

sophisticated statistical tools to

scores of sentencing models. The great

virtue of the Baldus work was the

richness of his data sources and the

extraordinary thoroughness of his

analysis. Throughout this research,

Baldus and his colleagues forthrightly

tested many alternative hypotheses and

combinations of factors, in order to

determine whether the initial observed

racial disparities would diminish or

disappear. (Fed.Tr.1082-83). Far from

concealing their results from scrutiny,

they exposed them to open and repeated

inquiry by others, soliciting from the

State and obtaining from the federal

judge in this case an additional

"sentencing model" which they then

tested and reported. (Fed.Tr.810; 1426;

1475-76)(R. 731-52).

54

The results of these analyses were

uniform. Race-of-victlm disparities not

only persisted in analysis after

analysis — at high levels of

statistical significance — but the race

of the victim proved to be among the

more influential determiners of capital

sentencing in Georgia. Professors

Baldus and Woodworth indicated that

their most explanatory model of the

Georgia system, which controlled 39

legitimate factors, revealed that, on

average, the murderers of white victims

faced odds of a death sentence over 4.3

times greater than those similarly

situated whose victims were black. (See

DB 82). Moreover, black defendants like

petitioner McCleskey whose victims were

white were especially likely to receive

death sentences.

b. The Opportunity for Discretion

The strong racial disparities shown

55

by Professor Baldus arise in a system

affording state actors extremely broad

discretion, one unusually "susceptible

of abuse." Castaneda v. Partida, 430

U.S. at 494. The existence of discretion

is relevant because of "the opportunity

for discrimination [it] . . . present[s]

the State, if so minded, to discriminate

without ready detection." Whitus v.

Georgia, 385 U.S. at 552. The

combination of strong racial disparities

and a system characterized by ample

State discretion has historically

prompted the closest judicial scrutiny.

See, e.q., Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S.

at 373-74.

Post-Furman capital sentencing

systems in general are characterized by

a broad "range of discretion entrusted

to a jury," which affords "a unique

opportunity for racial prejudice to

operate but remain undetected." Turner

56

v. Murray, 90 L.Ed. 2d at 35. The

Georgia system is particularly

susceptible to such influences, since

Georgia: (i) has only one degree of

murder, Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153,

196 (1976); (ii) permits a prosecutor to

accept a plea to a lesser offense, or to

decline to submit a convicted murder

case to a sentencing jury, even if

statutory aggravating circumstances

exist, _id. at 199; (iii) includes

several statutory aggravating

circumstances that are potentially

vague and overbroad, id. at 200-02 (at

least one of which has in fact been

applied overbroadly, Godfrey v. Georgia,

446 U.S. 420 (1980)); and (iv) allows a

Georgia jury "an absolute discretion" in

imposing sentence, unchecked by any

facts or legal principles, once a single

aggravating circumstance has been found.

Zant v. Stephens, 462 U.S. 862, 871

57

( 1983) .

Petitioner presented specific

evidence which strongly corroborated

this general picture. The District

Attorney for Fulton County, where

petitioner was tried, acknowledged that

capital cases in his jurisdiction were

handled by a dozen or more assistants.

(Dep. 15, 45-48). The office had no

written or oral policies or guidelines

to determine whether a capital case

would be plea-bargained or brought to

trial, or whether a case would move to a

sentencing proceeding upon conviction.

(Dep. 12-14, 20-22, 28, 34-38). The

District Attorney admitted that his

office did not always seek a sentencing

trial even when substantial evidence of

aggravating circumstances existed. (Dep.

38-39). Indeed, he acknowledged that

the process in his office for deciding

whether to seek a death sentence was

58

"probably . . . the same" as it had been

in the pre-Furman period. (Dep. 59-61).

These highly informal procedures are

typical in other Georgia jurisdictions

as well. See Bentele, The Death Penalty

in Georgia: Still Arbitrary, 61 Wash.

U. L.Q. 573, 609-21 (1985)(examining

charging and sentencing practices among

Georgia prosecutors in the post-Furman

period).

b. The History of Discrimination

Finally, "the historical background"

of the State action under challenge "is 17

17 This evidence is sufficient to

overcome the constitutional presumption

"that prosecutors will be motivated in

their charging decisions [only by] . . .

the strength of their case and the

likelihood that a jury would impose the

death penalty if it convicts." Gregg v.

Georgia, 428 U.S. at 225. Professor

Baldus performed a number of analyses on

prosecutorial charging decisions, both

statewide (Fed.Tr.897-910; S.E. 56-57),

and in Fulton County (Fed.Tr.978-81;

S.E. 59-60), which demonstrate racial

disparities in prosecutorial plea

bargaining practices.

59

one evidentiary source." Arlington

Heights, 429 U.S. at 267. See generally

Hunter v. Underwood,__U.S.__, 85 L.Ed.2d

222 (1985); Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S.

613 (1982). Petitioner supplemented

his strong statistical case with

references to the abundant history of

racial discrimination that has plagued

Georgia's past. Some of that history

has been set forth in the petition for

certiorari, and it will not be reviewed

in detail in this brief.

It suffices to note here that, for

over a century, Georgia possessed a

formal, dual system of crimes and

penalties, which explicitly varied by

the race of the defendant and that of

the victim. (See Pet. for Certiorari,

3-4). When de jure discrimination in

Georgia's criminal law ended after the

Civil War, it was quickly replaced by a

social system involving strict de jure

60

segregation of most areas of public

life, with consequent rampant de facto

discrimination against blacks in the

criminal justice system.18 (Id., 8-11).

This Court and the lower federal courts

have been compelled repeatedly to

intervene in that system well into this

century to enforce the basic

constitutional rights of black citizens.

(See cases cited in Pet. for Certiorari,

10n.l8. Unfortunately, the State's

persistent racial bias has extended to

the administration of its capital

statutes as well.

* * * *

In sum, petitioner presented the

District Court with evidence of

18 As a Georgia court held in

1907: "[E]quality [between black and

white citizens] does not, in fact,

exist, and never can. The God of nature

made it otherwise and no human law can

produce it and no tribunal enforce it."

Wolfe v. Georgia Ry. & Elec. Co.. 2 Ga.

App. 499, 58 S.E. 899, 903 (1907).

61

substantial racial discrimination in

Georgia's capital sentencing system,

after controlling for hundreds of non-

racial variables. He noted that this

highly discretionary system was open to

possible abuse, and he recited a long

and tragic history of prior

discrimination tainting the criminal

justice system in general and the

administration of capital punishment in

particular. Nothing more should have

been necessary to establish a prima

facie case under this Court's settled

precedents.

(iii) The Opinion Below

A majority of the Court of Appeals

found petitioner's evidentiary showing

to be "insufficient either to require or

to support a decision for petitioner."

(J.A. ). The court in effect announced

the abolition of the prima facie

standard, and required instead that

62

petitioner produce evidence "so great

that it compels a conclusion that the

system is arbitrary and

capricious," (J.A. ) and "so strong as

to permit no inference other than that

the results are the product of a

racially discriminatory intent or

purpose." (J.A. ). Petitioner failed

this test, the court concluded, in part

because his studies failed to take

account of "'countless racially neutral

variables,'" including

looks, age, personality,

education, profession, job,

clothes, demeanor and remorse,

just to name a few . . There

are, in fact, no exact

duplicates in capital crimes and

capital defendants.

(J.A. ).