Thurgood Marshall Comment on Supreme Court's Ruling in Virginia Case

Press Release

June 9, 1959

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Thurgood Marshall Comment on Supreme Court's Ruling in Virginia Case, 1959. 3a6e3c81-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e185de91-25ee-4f3b-9326-d05583537558/thurgood-marshall-comment-on-supreme-courts-ruling-in-virginia-case. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

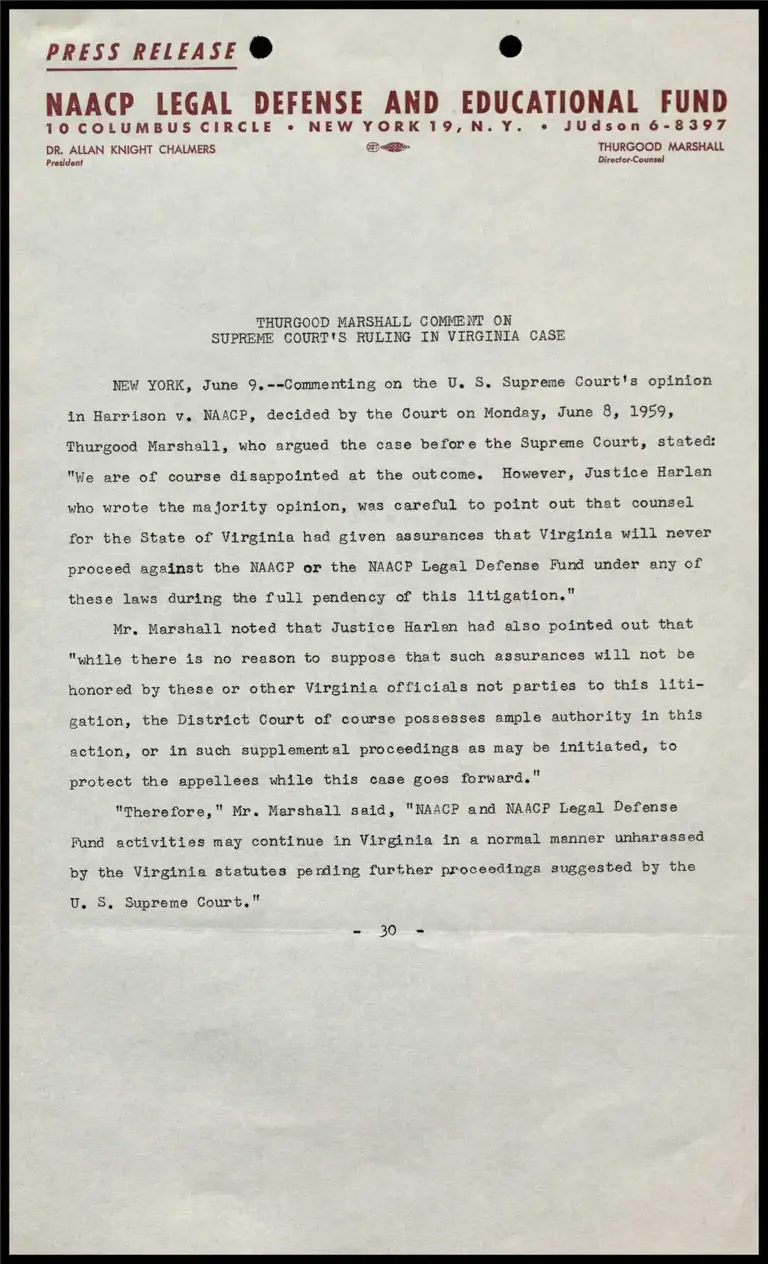

PRESS RELEASE @ &

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE + NEW YORK 19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS oS THURGOOD MARSHALL

President Director-Counsel

THURGOOD MARSHALL COMMENT ON

SUPREME COURT'S RULING IN VIRGINIA CASE

NEW YORK, June 9.--Commenting on the U. S. Supreme Court's opinion

in Harrison v. NAACP, decided by the Court on Monday, June 8, 1959,

Thurgood Marshall, who argued the case before the Supreme Court, stated:

"We are of course disappointed at the outcome. However, Justice Harlan

who wrote the majority opinion, was careful to point out that counsel

for the State of Virginia had given assurances that Virginia will never

proceed against the NAACP or the NAACP Legal Defense Fund under any of

these laws during the full pendency of this litigation."

Mr. Marshall noted that Justice Harlan had also pointed out that

"while there is no reason to suppose that such assurances will not be

honored by these or other Virginia officials not parties to this 1liti-

gation, the District Court of course possesses ample authority in this

action, or in such supplemental proceedings as may be initiated, to

protect the appellees while this case goes forward."

"Therefore," Mr. Marshall said, "NAACP and NAACP Legal Defense

Fund activities may continue in Virginia in a normal manner unharassed

py the Virginia statutes perding further proceedings suggested by the

U. S. Supreme Court."

SS 50" we