Boyd v. Pointe Coupee Parish School Board Supplemental Brief for Plaintiffs as Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 26, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boyd v. Pointe Coupee Parish School Board Supplemental Brief for Plaintiffs as Amici Curiae, 1973. 73176184-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e1ce7693-8e44-4cd0-9f69-ab7a86f4f6b4/boyd-v-pointe-coupee-parish-school-board-supplemental-brief-for-plaintiffs-as-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

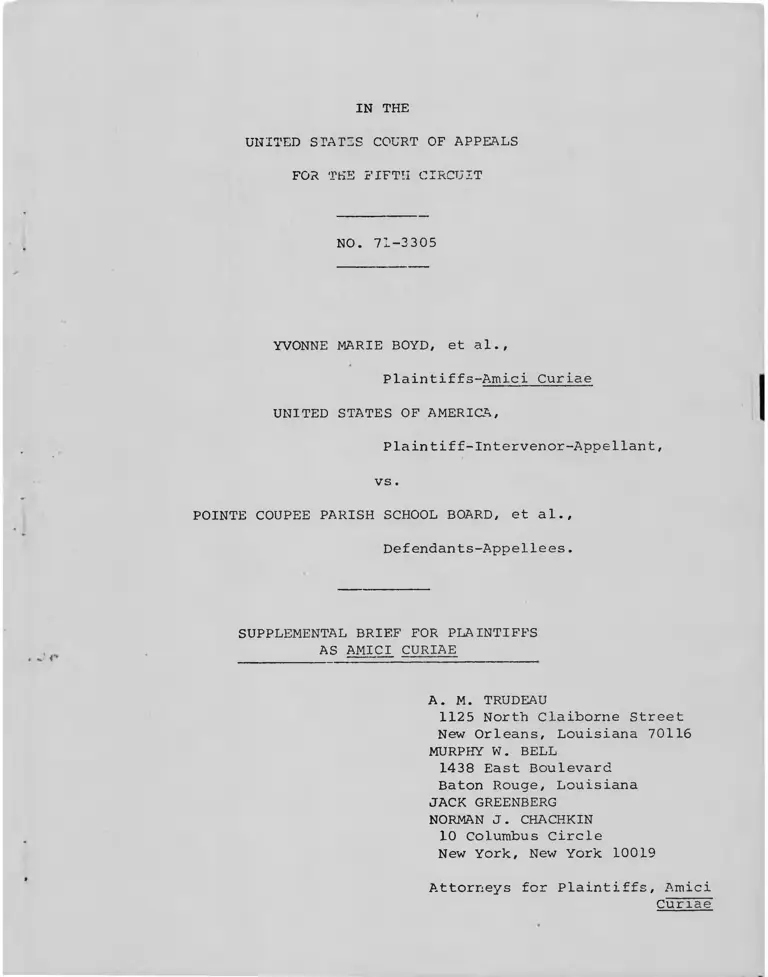

IN THE

UNITED STATIS COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71-3305

YVONNE MARIE BOYD, et al..

Plaintiff3-Amici Curiae

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant,

vs.

POINTE COUPEE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS

AS AMICI CURIAE

A. M. TRUDEAU

1125 North Claiborne Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70116

MURPHY W. BELL

1438 East Boulevard

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs, Amici

Curiae

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71-3305

YVONNE MARIE BOYD, et al..

Plaintiffs-Amici Curiae,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant,

vs.

POINTE COUPEE PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS

AS AMICI CURIAE

Plaintiffs, participating in this appeal as amici

curiae pursuant to the Order of this Court entered January

11, 1972, submit this Supplemental Brief in accordance with

1/the Court's directions contained in its Order of July 10, 1973.

The purpose of the brief is to identify the issues presented

1/ The Court's Order mistakenly identifies plaintiffs as the

appellants in its caption, and requires submission of a

supplemental brief by "appellants" in the body of the Order. To

avoid any misunderstanding, we are setting out our position in

this document; we understand the United States, appellant herein,

is also filing a supplemental brief.

on this record concerning public school desegregation in Pointe

Coupee Parish which are yet unresolved, and as to which the

parties continue to maintain adversary positions.

The judgment from which this appeal is prosecuted was

2/

issued by minute entry dated September 20, 1971 (and a copy

thereof is attached hereto as Appendix "AA"). The district

3/court denied the motion of the United States for supplemental

relief and appended to its judgment a statement of reasons for

its action which, we believe, can fairly be read as a ruling

upon each of the three issues which have been discussed in the

previous submissions of the parties to this appeal: (a) assign

ment of faculty among Pointe Coupee Parish public schools;

(b) assignment of students to classes in the "Upper Pointe Coupee"

(Batchelor-Innis) center; and (c) continuing maintenance of

LaBarre, Rosenwald, and St. Alma as all-black schools. C f -

2/ The order was actually entered October 6, 1971.

3/ Attached to this Supplemental Brief as Appendix "BB" is a

detailed statement of the history of this case which attempts

to unravel its tangled procedural skein. We would simply note

here that although defendants have in the past urged that the

government's motion in the district court was limited only to

the faculty assignment question, the record affirmatively re

flects both that the United States adopted the plaintiffs' and

plaintiff-intervenors' contentions as their own (see Minute

Entry of August 11, 1971, attached hereto as Appendix "CC"; Tr.

8 [Transcript of August 11, 1971 hearing, attached as Appendix

"B" to "Brief of Plaintiffs and Plaintiff-Intervenors" in this

cause filed December 20, 1971 in this Court]) and also that the

- 2 -

1 /note 3, supra. The remaining question, then, is whether these

issues still present live controversies affecting the operation

of Pointe Coupee Parish schools. We submit that they do.

The latest Hinds County report, with which the record

on this appeal was supplemented pursuant to this Court's order

of June 1, 1973, reveals that the violations of the Constitution

of which plaintiffs and the United States complained, and which

were sanctioned by the district court's order, yet continue.

LaBarre, Rosenwald and St. Alma schools are still all-black as

a result of the plan of student assignment approved by the

district court; classes at the Upper Pointe Coupee center are

almost totally segregated; faculty ratios at the various schools

range from 28.5% black (Poydras) to 93.1% black (Rosenwald).

Thus, the issues presented for resolution at the time this appeal

was filed remain unresolved.

3/ (continued)

various issues were brought to the attention of the district

court (e.g,, Tr. 40, 42, 44, 57-58, 65). See note 4 infra.

4/ Indeed, the court's order deals most explicitly with the

continued maintenance of LaBarre, Rosenwald and St. Alma

schools as all-black facilities, but the district court also

makes the explicit finding that the "Pointe Coupee Parish

School System is now, in fact, a unitary, non-discriminatory

school system within the meaning and intent of federal law."

In light of the presentation of the Singleton and Batchelor-

Innis assignment contentions to the district court, this language

can only mean that these contentions were passed upon and rejected.

-3

We believe, therefore, that the present unconsti

tutional conditions in the public schools of Pointe Coupee

Parish are the direct and continuing result of the order from

which this appeal was taken. They are thus properly before

this Court and their correction is required. Furthermore,

although the procedural posture of this matter is complicated

and perhaps even unwieldy, the case is properly here on appeal

and this Court has an obligation (taking into account the latest

enrollment and faculty figures by which the record has been

supplemented) to enforce the Constitution. Cf., e.q., Hall v.

St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417 F.2d 801 (5th Cir.), cert,

denied, 396 U.S. 904 (1969).

The Merits

Without attempting to duplicate the extensive material

already filed in this cause, we believe it would be helpful if

we very briefly summarized our contentions with respect to each

issue for the benefit of the Court.

1. Faculty. The government's motion for supplemental

relief in the district court alleged that faculty assignments

were not in compliance with Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Separate School Dist., 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969). The

district court denied the motion. As of October 12, 1971, the

ratios among the nine school facilities operated by the defen-

-4-

dants (treating Batchelor-Innis as a single school) ranged from

30% black (Livonia) to 95% black (Rosenwald). As noted above,

the most recent figures demonstrate variances from 28.5% black

to 93.1% black. This Court should direct entry of an order by

the district court requiring full compliance with Singleton.

«

2. Testing. Following remand of this case to the

district court for submission and approval of desegregation

plans other than freedom-of-choice, sub nom. Hall v. St. Helena

Parish School Bd., supra, an HEW-devised plan was entered. There

after, without hearing, the district court on August 21, 1970

granted a motion to modify the plan by, inter alia, assigning

students to academic or vocational campuses in the Batchelor-

Innis (Upper Pointe Coupee) area of the parish according to

their performance on standardized achievement tests. The latest

report indicates the resulting segregation of classes is nearly

total. The matter was raised and discussed before the district

court (Tr. 40, 44), which apparently believed the issue was

precluded by this Court's dismissal of an earlier appeal for

untimeliness even though this Court's Order (in No. 30467) stated

it was "without prejudice to further proceedings in the district

court which may be warranted in this school desegregation case"

(Tr. 62-63). The district court denied supplemental relief.

The classes continue segregated, in clear violation of this

-5-

Court's rulings from Anthony v. Marshall County B d . of Educ.,

419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969) through Moses v. Washington Parish

School Bd., 456 F.2d 1285 (5th Cir. 1972). As was done in

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd., 444 F.2d 1400, 446 F.2d 911

(5th Cir. 1971), this Court in this case should direct reinsti

tution, immediately, of the HEW plan for the Batchelor-Innis

area and elimination of the testing proposal.

3. Retention of all-black schools. Plaintiff-intervenors1

motion for further relief, adopted by the United States and by

the plaintiffs (Tr. 6, 8) specifically complained that the

continuance of three all-black schools in the parish meant that

a unitary school system had not been achieved. These resulted

from the abandonment of the HEW pairing plan allowed by the

August 21, 1970 district court order referred to above. The

district court dealt with this contention extensively in its

minute entry, concluding that these schools were "de facto"

segregated. Such a ruling is patently ridiculous and flies in

the face of the record and this Court's rulings in such cases

as Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ., 457 F.2d 1091 (5th Cir.

1972) and Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School Dist.,

467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972) (eii banc) , cert. denied, ___ U.S.

___ (1973). For the reasons we set out in our brief tendered

in No. 30467, the HEW plan must be reinstituted in these areas

of the parish also.

-6

CONCLUSION

Plaintiffs would respectfully pray that the judgment

of the district court be reversed with directions.

Respectfully submitted

A. M. TRUDEAU

1125 North Claiborne Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70116

MURPHY W. BELL

1438 East Boulevard

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J .CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs, Amici

Curiae

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 26th day of July, 1973,

I served two copies of the foregoing Supplemental Brief for

Plaintiffs as Amici Curiae upon the attorneys for the parties

herein, John F. Ward, Jr.,Esq., 206 Louisiana Avenue, Baton

Rouge, Louisiana, and Gerald Kaminski, Esq., United States

Department of Justice, Washington, D.C. 20530, by United States

mail, first-class postage prepaid.

Norman J. Chachkin

Attorney for Plaintiffs

-7-

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BATON ROUGE DIVISION

MINUTE ENTRY s

SEPTEMBER 20, 1971

WEST, J.

YVONNE MARIE BOYD, ET AL

VERSUS

POINTS COUPEE PARISH SCHOOL

BOARD, ET AL

CIVIL ACTION

NUMBER 3164

* * * * * * *

This matter carao on for hearing on a prior day on the

motion of the United States of America, intervenor herein, for

supplemental relief when, after hearing the evidence and arguments

of counsel, the Court took time to consider. Now, after due con

sideration, the motion of the United Statea of America for

supplemental relief is DENIED.

REASONS

The- e-vidence in this case show3 that this Court issued

an order on July 25, 1359, requiring implementation of integration

plans for the Pointe Coupee Parish schools. This order and plan

was affirmed by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals on January 6,

1970. Certain modifications to this plan were requested by the

School Board which, by order of this Court dated August 21, 1970,

were granted. That order was appealed and on November 13, 1970,

the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the appeal.

appendix aa

Pursuant to these orders, all students in the Pointe

Coupee Parish School System were assigned to schools on a

racially non-discriminatory basis. If all students had, in

fact, continued to attend the schools to which they had been

assigned, integration of the schools would have been complete,

and substantially in accordance with existing ratios of whites

to negroes in the system. But as a result of these assignments,

some 1800 or more students left the public school system to

attend private schools. The result was the re-establishment

of three all negro schools in the system. None of the white

students who left these schools were permitted to attend other

schools in the system. They left the public school system which,

of course, they had a legal right to do. Consequently, the re

establishment of the colored schools in the Pointe Coupee Parish

School System has in no way been brought about by State action.

The segregation resulting is purely de facto in nature. It would

be foolhardy to continue to reshuffle the student population

every time some students exercised their legal right to leave

the public school system in an effort to keep "spreading" the

white students among all of the schools. Somewhere the line must

be drawn between forced segregation and segregation which comes

about by lawful choice. The point has been reached in the Pointe

Coupee Parish System whore this Court must conclude (1) that the

orders of this Court pertaining to integration of schools have been

complied with? (2) that the Pointe Coupee Parish School Board

is operating a unitary, non-discriminatory school system? (3)

that there is. no State action involved in the re-segregation of

certain schools in the system? and (4) that whatever re-segregation

of schools now remains is no different from that remaining in many

northern areas — it is purely cle facto, resulting from the exercise

of n legal right by some white students to leave the public school

system. This is simply an inevitable result of forced integration

of schools and does not give rise to the supplemental relief

sought by the Government. The Pointe Ccupee Parish School Board

has not returned to a freedom of choice plan. Students in that

system must attend the school to which they are assigned if they

are to remain in the system. And if they do so, all schools

would be integrated in strict accordance with the law. In other

words, the students do not have any freedom of choice insofar as

what school in the system they v/ill attend. If they attend any,

they mu3t attend the one to which they have been assigned. But

they do, of course, have the choice of withdrawing from the system

entirely and attending private schools if they wish. The fact

that many of them exercise this choice does not supply any merit

to the contention that a dual system of schools has been re-established

by the School Board. If the students who have left the system choose

to return, they will, once again, be assigned to a school in accord

ance with the integration plan under which the School Board is forced

to operate. Thus, the fact that certain schools have become re

segregated involves no State action of any kind.

There is no credible evidence to show that there has

been any racial discrimination in the hiring or firing of

supervisory personnel. The evidence conclusively show3 that

supervisory personnel have been properly integrated and that

race is no longer a consideration in the employment of such

personnel. If race is not a factor, and if using qualifications

as the primary criteria results in an imbalance between white

and ne-gro personnel, so be it. There is nothing wrong with

such a result where no discriminatory intent or plan has been

shown. Ko such plan or intent has been shown here. The Pointe

Coupee Parish School System i3 now, in fact, a unitary, non—

discriminatory school system within the meaning and intent of

federal law. The supplemental relief sought i3 therefore denied.

UHITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

APPENDIX BB

PROCEDURAL HISTORY

Throughout the following description of the history

of this cause, the following terms will be used to describe

the various parties: the original plaintiffs will be referred

to as the "BOYD Plaintiffs;" the plaintiff-intervenors in the

district court as the "DOUGLAS Plaintiffs;" the defendants as

the "BOARD" and the United States as the "GOVERNMENT."

These proceedings originated with this Court's

invalidation of the Pointe Coupee Parish freedom-of-choice

desegregation plan, in light of Green v. County School Bd. of

New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), and its remand to the

district court for adoption and implementation of a new and

effective desegregation plan. 417 F.2d 801 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied, 396 U.S. 904 (1969). On July 25, 1969, the district

court ordered implementation of alternative plans on a phased

basis. The result of this order and the alternatives was that

all of the HEW-recommended sbhool pairings would be implemented

over a two-year period, rather than in the fall of 1969. The

BOYD plaintiffs had filed objections to the BOARD proposals

but these were overruled.

bl

On October 10, 1969, following the declaration

by the Governor of Louisiana of a so-called "freedom of choice"

school holiday for Monday, October 13, 1969, the DOUGLAS Plain

tiffs sought, and were granted, leave to intervene in this

action. (Judge West being temporarily absent from the district,

that motion was heard before and granted by Judge Mitchell, of

the New Orleans Division). Following an emergency appeal to

this Court, a temporary restraining order was issued barring

participation in the said "freedom of choice" holiday.

On or about August 10, 1970, the BOARD filed a Motion

in the district court to amend its desegregation plan by

zoning areas of the parish which had been, or were scheduled

to be, served by paired schools under the July 25, 1969 order.

On August 21, 1970, the BOYD plaintiffs mailed to counsel and

the district court, written objections to the BOARD'S motion.

However, on that same date (August 21), and without any hearing,

the district court entered an order approving the modifications.

Counsel for the BOYD plaintiffs did not receive

notice of the entry of the August 21, 1970 order. Consequently,

the BOYD plaintiffs filed no Notice of Appeal within the time

prescribed by the Singleton time schedule. On August 31, 1970,

however, the DOUGLAS plaintiffs did file a Notice of Appeal,

subsequently docketed as No. 30467 in this Court.

b2

On the same date, August 31, 1970, the DOUGLAS Plain

tiffs filed a Motion for Summary Reversal of the district court's

order. This document was never served upon counsel for the BOYD

Plaintiffs.

The first notice the BOYD Plaintiffs had that the

district court had approved the BOARD'S requested modifications

was upon receipt of the BOARD'S Motion to Dismiss the appeal

of the DOUGLAS Plaintiffs (for lack of standing) and opposition

to the summary reversal. Immediately thereafter, undersigned

counsel sent the following telegram to the members of the Panel

to which No. 30467 had been assigned:

Please be advised that plaintiffs Boyd

et al. were never notified either of

August 21 district court order or August

31 motion for summary reversal. Had we

been so advised we would also have filed

notice of appeal and sought summary

reversal. Plaintiffs do not wish at

this point however to delay consideration

of the appeal, which we urge has merit.

We will furnish the court with copies of

our opposition to the school board's

request for modification, which we filed

with the district court on the same day

that the plan was approved, and we

request the court's favorable consideration

of the arguments which we sought to bring

to the attention of the district court.

The material referred to was forwarded to the Court. On

September 23, 1970, the GOVERNMENT filed a Memorandum

suggesting a remand for further evidentiary proceedings. On

October 21, 1970, counsel for the BOYD Plaintiffs filed a

b3

brief amicus curiae together with a motion for leave to thus

appear. By order of October 26, 1970, this Court granted the

BOYD Plaintiffs leave to participate in the pending appeal as

amicus.

Thereafter, on November 13, 1970, upon motion of

the BOARD, the appeal of the DOUGLAS Plaintiffs was dismissed

for failure to file a timely brief, but "without prejudice to

further proceedings in the District Court as may be warranted

in this school desegregation case."

The BOYD Plaintiffs and Plaintiffs in five other

Baton Rouge Division school desegregation cases then filed

motions seeking inclusion of reporting provisions in the

desegregation decrees of the district court. The BOYD Plain

tiffs sought updated faculty and student information prior to

commencing the further proceedings in the district court

contemplated in this Court's 1970 Order dismissing the appeal.

That relief was subsequently ordered by this Court, sub nom.

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 443 F.2d 1181 (5th Cir.

1971) .

July 26, 1971, the DOUGLAS Plaintiffs filed a "Motion

for Further Relief" which the district court subsequently

scheduled for hearing August 11, 1971. August 10, 1971, the

b4

GOVERNMENT filed a "Motion for Supplemental Relief Counsel

for all parties appeared at Baton Rouge for the hearing on

August 11, 1971- At that time, as reflected in the minute entry

(Appendix "CC" infra), the district court dismissed the DOUGLAS

Plaintiffs from the action as intervenors, but the motion for

further relief was adopted by both the BOYD Plaintiffs and the

GOVERNMENT. As reported in the body of this Supplemental Brief,

the motions, and all relief sought by either the GOVERNMENT,

the BOYD Plaintiffs, or the DOUGLAS Plaintiffs, was denied by

the district court.

Following that hearing, on September 1, 1971, counsel

for the DOUGIAS Plaintiffs was associated with counsel for

the BOYD Plaintiffs.

Because they were informed that the GOVERNMENT would

appeal the district court's order, the BOYD Plaintiffs did not

file a separate appeal but determined to support the GOVERNMENT'S

appeal. Following a motion by the BOARD to limit their partici

pation on this appeal, this Court on January 11, 1972, permitted

the BOYD Plaintiffs to proceed herein as amici curiae.

b5

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

BATON ROUGE DIVISION

MINUTE ENTRY:

August 11, 1971

WEST, J.

YVONNE MARIE BOYD, ET AL

versus CIVIL ACTION

POINTS COUPEE PARISH SCHOOL

BOARD, ET AL

NO. 3164

This cause cane on for hearing this day on (1) motion by Intervening

plaintiff, Enmitt J. Douglas, for further relief; (2) defendants’ motion to

dismiss improper intervention and motion for further relief filed by such

improper intervenor; and (3) Government1s motion for supplemental relief.

PRESENT: Murphy W. Bell, Esq.

Attorney for intervenor, Emmitt J. Douglas

Norman Chachkin, Esq.

Attorney for plaintiffs

John F. Ward, Jr., Esq.

Attorney for defendants

Frank D. Allen, Jr., Esq.

Attorney for the Government

Counsel for defendants files a motion for summary judgment, and it is

DENIED.

The Court grants defendants' motion to dismiss Emnitt J. Douglas asai

improper intervenor, and counsel for plaintiffs and the Government adopt the

dismissed intervenor's motion for further relief.

Defendants file exhibit D-#l (school survey).

The Court hears the arguments of counsel, and the matter is SUBMITTED.

A P P E N D S c c