Morrow v. Crisler Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 10, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Morrow v. Crisler Brief for Appellants, 1972. 3d3dddcc-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e1f6ad79-fb8d-4b67-b149-9b2ee23a1e09/morrow-v-crisler-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

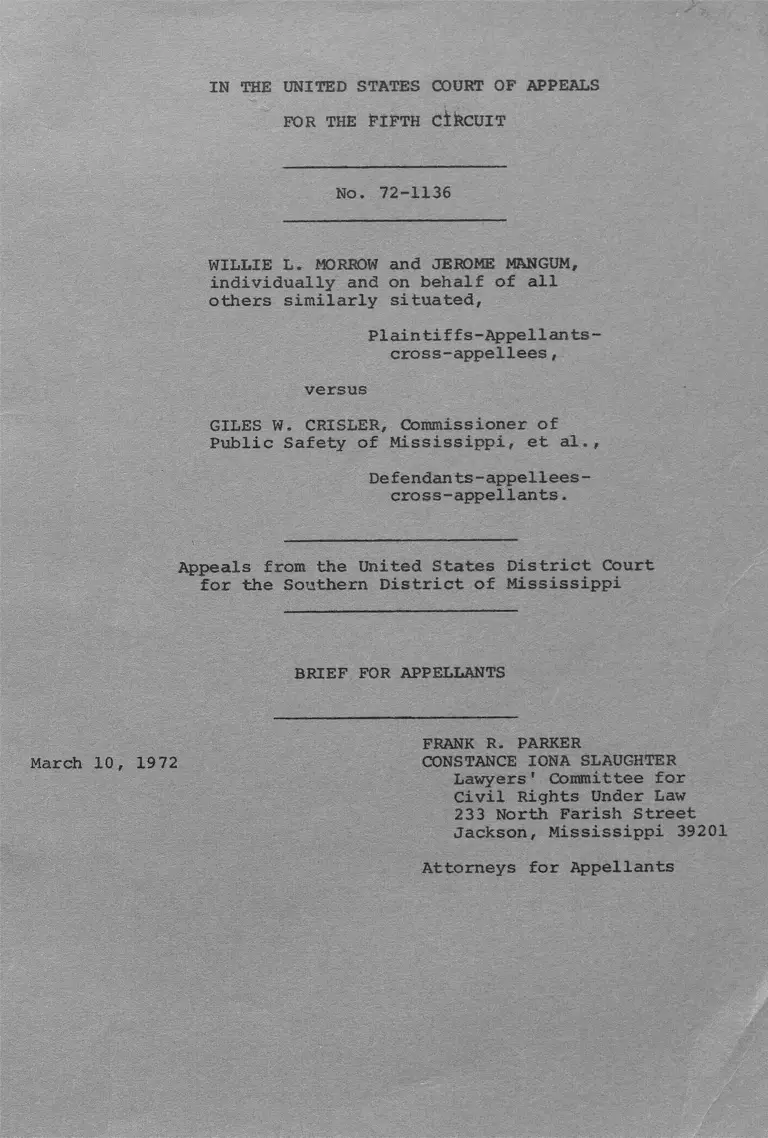

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH C±kCUIT

No. 72-1136

WILLIE L. MORROW and JEROME MANGUM,

individually and on behalf of all

others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-

cross-appellees,

versus

GILES W. CRISLER, Commissioner of

Public Safety of Mississippi, et al.,

Defendants-appellees-

cross-appellants.

Appeals from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

FRANK R. PARKER

March 10, 1972 CONSTANCE IONA SLAUGHTER

Lawyers' Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

233 North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

Attorneys for Appellants

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-1136

WILLIE L. MORROW and JEROME MANGUM,

individually and on behalf of all

others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-

cross-appellees,

versus

GILES W. CRISLER, Commissioner of

Public Safety of Mississippi, et al.,

Defendants-appe1lees-

cross- appellants .

Appeals from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Mississippi

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY FIFTH CIRCUIT LOCAL RULE 13(a)

The undersigned, counsel of record for appellants,

certifies that the following listed parties have an interest in

the outcome of the case. These representations are made in

order that Judges of this Court may evaluate possible disqualifr-

ua uj-uu c-'jl jouibuan l uoj ^gl_l i\uic j_ \ a. / *

Plaintiffs and identified plaintiff class member:

Willie L. Morrow, Jerome Mangum, Owen G. Coker.

Defendants: Governor of Mississippi, Commissioner

of Public Safety, Chief of Patrol, Personnel Officer

of the Mississippi Department of Public Safety.

Other: State of Mississippi, and all employees of

the Mississippi Department of Public Safety.

FRANK R. PARKER

Attorney of record for appellants.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Page

ii

1

3

A. Proceedings Below 3

B. The Decision Below 3

C. The Issues On Appeal 11

D. Jurisdiction 14

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN

DENYING PLAINTIFFS SPECIFIC

RELIEF IN THE FORM OF EMPLOYMENT

OFFERS, BACK WAGES, AND OTHER

BENEFITS. 15

A. The Proper Legal Standard 16

B. The Defense 17

C. Plaintiffs' Evidence 21

D. Checking Back 23

E. The Rights of Plaintiffs to

Specific Relief 24

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO ORDER AFFIRMATIVE HIRING RELIEF

FOR MINORITY PERSONS AS A CLASS. 28

A. The Weight of Authority in This

and Other Circuits. 29

B. The Rationale For Aflirmative

Class Relief in This Case. 33

C. The Available Affirmative Remedies 38

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO ENJOIN THE ADMINISTRATION OF

UNVALIDATED EMPLOYMENT TESTS. 42

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO GRANT ATTORNEY'S FEES AT THE RATE

REQUESTED BY PLAINTIFFS. 44

V. THE DISTRICT COURT WAS WITHOUT

JURISDICTION TO GRANT DEFENDANTS'

MOTION TO MODIFY JUDGMENT. 48

CONCLUSION 52

\

-l-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE

Ackermann v. United States, 340 U.S. 193, 71

STCFTTO9 , 9T'T7rEcTr“r0T-C19 50) . .......................... 50,52

Annat v. Beard, 277 F.2d 554 (5th Cir. 1960) ,

cert, denied, 364 U.S. 908 (1960) . . . . . , . . . , . .49

Armstead v. Starkville Munv Sep. School Dist.,

3T5~~F. Supp. 5F0 (N. D . Miss". TT7T7 I 7~7 . . . . . . . . 44

Arrington v. Massachusetts Bay Transo. Auth.,

w f . suPp T ^ T 5 T ^ i i r ^ i ^ r T ‘9T¥r“rT~r". . . . . . . . .44

Baker v. Columbus Mun. Sep. School Dist., 329

F. Supp. 706.(N7d7 Miss. 157TJ 7 ~ 44

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711

C7th cTFrrroT) : . . . ........... .. .27,35

Bradley v. School Bd. of City of Richmond, Va.,

5T f .r .D7*~TS“T e7d 7~W7_TT7T1 I I ; 1 ) I ~. . . . . . .45,46

Camp v. Boyd, 229 U.S. 530, 33 S.Ct. 785, 57

L.Ed. T3T7 (1913) . . . . . . . . . . . . .26

Carr v. Conoco Plastics, Inc., 423 F.2d 57 (5th

Cir. IFT0T7 certT d'eniecTT-"400 U.S. 951 (1970) . . . . . 34

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir. 1972)

Ten banc77 reversing in part 452 F.2d 315

(1971) , affirming In part and reversing In

part 3 EPD 1[ 8205 (D. Minn. 1971). . . . . . . . . . . .30,37,40,44

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Bd. of Educ.,

o c a xn ->a t_oo rum mu TTTcTc'i emu iwrvrv i a 1 1

Chambers v. United States, 451 F.2d 1045 (Ct. Cl. 1971) . . . . . 41

Clark v. American Marine Corp., 437 F.2d

959 (5th Cir. 19 7lTT~af firming 320 F. Supp.

709 (E.D. La. 1970) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Clark v. American Marine Corp.T 304 F. Supp. 603

[E.D. LiT“T970T ........ ............................... 45

Contractors Ass'n of Eastern Pennsylvania v. Secretary

of~Labor, 442 F.2d 15rT5^~ClK~TJ7IT~. . . . . .41

Colbert v. H-K Corp., 444 F.2d 1381 (5th Cir. 1971)........ 42

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metal Co., 442 F.2d 1078

"7.5th Cir. 1971) 7™. . . ................................ 27

-ii-

Dyer v. Love, 307 F. Supp. 9 74 (N.D. Miss. 1969) 45

Fears v. Burris Mfg. Co. , 4 EPD Ijf 7535, 7536 (5th

Cir. 1T7T7 .......................... .............. .. .45

Ferrell v. Trailmobile, Inc., 223 F.2d 697 (5th Cir.

' T 3 3 3 ) --- ~ ... - ' * “ 49t *

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 91 S.Ct.

BH, 28- L(Ed.'2d 138 (1971) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42,44

Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School Dist., 427

F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400

U.S. 991 (1971) ............................ .. . . . .. . 27

Hicks v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 310 F. Supp. 536

TE.D. La.~T3701 . 7 . 41,44

Horton v. Lawrence Co. Bd. of Educ., 449 F.2d 793

T3EE Cir7 137X7 ~ ~ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Interstate Circuit, Inc. v. United States, 306

---3757 2337 59 EX CTE7~~7r67, 8TT7:X37~5TD~T1939) . . . . . . . 22

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th

CxrT 196U7 — ....................... .. . . 35

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 417 F.2d

ITZZ (5tF~CTFr'r9^97 TT~TT~7 . . . . . . . . . . . . .27,34

Klapprott v. United States, 335 U.S. 601, 69 S.Ct.

387T7 33 L.F^r~2W~TTTW) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .50

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971) . . . .45,47

Lee v. Macon Co. .Bd. of Educ. (Muscle Shoals

School Svs tem), No'. 71-2963. 5Tfi Ci'r. . Dec. 28. 19 71 3 6.26

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 444 F.2d 143

(5 th CTf 7 1'97I)~ . . . . . . 7 . . . . . ........... .. . .45

Local 53, Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d

T0T7 (5th CxrT 7T559) .............................. . . 25,29,35,39,4

Local 189, United Papermakers v. United States, 416

F.Zd 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397

U.S. 919 (1970) ........ ............................. . ?2

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145, 85 S.Ct.

"5T7TT3 L.Ed72'd"T0'9" (TF6 5) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Lyle v. Teresi, 327 F. Supp. 683 (D. Minn. 1971) . . . . . 45

McFerren v. Co. Bd. of -Educ. of Fayette Co. , 4 EPD

li 7532 (6Xh Cir. 1972T~7 ; 7 7~~............... . . . .

-iii-

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises,

— rsth.cirT 1970) . . r . . . .

Inc., 426 F.2d 534

45

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375, 90

---37ct. F T O T ^ ^ lTe d."2d '393 (1970). . ........... .. 45

NAACP v. Allen, No. 3561-N, M.D. Ala., Feb. 10, 1972 . . . 32,40

NAACP v. Thompson, 357 F.2d 831 (5th Cir. 1966),

cert. denied, 385 U.S. 820 (1966) . . . . . . . . . . . .37

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400, 88

STCt. 9’ETT~T§ L . Ed. 2d 1263 (IT68) . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Norman v. Young, 422 F.2d 470 (10th Cir. 1970) . . . . . . 49

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433 F.2d

421' (8th Cir. 1970) . . . . .~T'T~T~T............... . .16,35,45,4 7

Penn v. Stumpf, 308 F. Supp. 1238 (N.D. Cal. 1970) . . . . .34

Perkins v. Mississippi, No. 30410, 5th Cir., Jan.

T4~ 19 72 ........ .............. .. 37

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 411 F.2d

99 8 (5th Cir. 19 691 \ . .............27

Ridley v. Phillips Petroleum Co., 427 F.2d 19 (10th

~Clr. 19 70T“7~'. . . . .................................... 50

Rinieri v. News Syndicate Co., 385 F,2d 818 (2d

CirT 19 67) . . 7 . . T 7 “. .............................. 52

Rios v. Enterprise Assn. Steamfi'ttersy Local 638, 326

F. SuppTTTg (s.D.N.Y. T57TJ T ........ .. . . . .

1 • -T- _ _ -i •_ m ---- a a a rn n

AUU1HO UJ.i V • JJUXXJ.A uj. C<. • / -a. ~i * u. « t~4

CirT "197lJ~’liert:̂ filed, 40 U.S.L.W.

(9/28/71) ............... ..

Rolfe v. Co. Bd. of Educ, 391 F.2d 77

•7 O '1 I A +-V,

3251

(6th Cir. 1968)

Singleton v. Jackson Mun. Sep. Sch. Dist., 419 F.2d

T2TlTT5th crFTT5W) (en~banc) , cert, denied, 396

U.S. 1032 (1970) .......... . . . . . . . . . .

Strain v. Philpott, 331 F. Supp. 836, 4 EPD

1111 7521, 7562 (M.D. Ala. 1971) . . . . .

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. l7~_9T_sTct7 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554 (1971).

United States ex rel. Tillery v . Cavell, 294 F .2d

12 (3d Cir. 196TT) cert, denied, 370 U.S.

945 (1962) ....................................

25

. 27,35

. 16

16

32

30

49

-xv-

United States v. Central Motor Lines, Inc. , 325 F.

Supp. 478 (W.D.N.C. 1970) . . . . . ................... 25

United States v. City Of Jackson, 318 F.2d 1

(5th Cir. 1963), on rehearing 320 F.2d 870 . . . . . . . 37

United States v. Frazer, 317 F. Supp. 1079 (M.D.

Ala. 1 9 7 0 ) ..................... ‘........... .. 32,39

United States v. Georgia Power Co. , 3 EPD 1i 8318

(N.D. Ga. 1971) . . . . . 7 T ........................... 46

United States v. Hayes Intern11 Co'rp. , 415 F.2d 1038

(5th Cir. 1969) . . . 7 7. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .32,38

United States v. Hayes Intern'! Corp., No. 71-1392,

5th Cir., Feb. 22, 19 72 . . . . ~........ .. 31

United States v. IBEW, Local No. 38, 428 F.2d

144 [6th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 943

(1970)........................................ 29

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d

418 (5 tin "Cir. 1971) cert, filed, 40 U.S.L.W. 3379

(2/7/72) . ............. 32,43,44

United States v. Jefferson Co. Bd. of Educ., 372

F.2d 836, aff'd en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967)

cert, denied, 389 U.S. ’840 (1967) . . . . . . . . . . . .16,35

United States v. Ladner, 238 F. Supp. 895 (S. D.

Miss. 1 9 6 5 ) .............................................. 23

United States v. Local 86 Ironworkers, 443 F,2d

544 (1971), cert, denied, 40 U.S.L.W. 3264 (11/19/71). . 30,41

United States v. Pickett's Food Service, 360 F.2d 338

(5th. Cir. 19 66) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . JZ

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, 416 F.2d 123

(8th Cir. 1969) ......................................... 29

United States v. Woodall, 438 F.2d 1317 (5th Cir. 1970)

(en banc) ~ . . . ............................ 23

Vogler v. McCarty, Inc., 451 F.2d 1236 (5th Cir. 1971) . . 31

-v-

Statutes and Regulations Page

28 United States Code

§ 1291 • • • • ................................ 15,48

§ 1 3 3 1 .......................................... 4

§ 1343 . ............................ 4

§ 2201 ................................................................4

§ 2202 ................................. 4

42 United States Code

§ 1981 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ............ 4,7

§ 19 82 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

§ 1983 ........................ .. 4,7,27

Title VI, Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2 0 0 0d . . . . ' . ............................... 4

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2Q00e . . . . . . . . . . . . . .... * * * 26 and passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (j) . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

42 U.S.C. § 2000e--5 (g) . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Mississippi Code

§ 4 065.3 (Re comp .1956). * * .........* • *37

§ 8665 (4) (Re comp.1956) . . . . . . . . . . . 2 3

Mississippi Classification Law,

§§ 8935-01 to 8935-14 (Supp. 1971) . . . . . 43

Miss. Laws, 1938, ch. 143 • ................. .. 5

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

2T_cTFTirrT6WT~T~':^ r~7 r~. . . . . ~ : “ . . .43,44,53

Executive Order No. 11246, 3 C.F.R. 402 (1970) • • • 41

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure

Rule 3(a) ................................. 49

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Rule 7 ( b ) ...................................... 49,50

Rule 2 3 ........................... - . . . . 33

Rule 52(a)............ .......................17

Rule 59(a) ................... . . . . . . . . 50

Rule 59(e) . . ................. .............. 44

Rule 60(a) .. ............. .................. 49

Rule 60(b)................................. * 48-51

Rule 65(d)......................................-vi-

Office of Federal Contract Compliance, Guidelines

on Employee Selection Procedures, 35 Fed. Reg. 19307

(Oct. 2, 19 71) .......................................44

Other Authorities

Cooper and Sobol, "Seniority and Testing Under

Fair Employment Laws: A General Approach to

Objective Criteria in Hiring and Promotion,"

82 Harv. L. Rev. 159 8 (1969) ............... .. 42

C. McCormick, Evidence (1.954) . .......................... 23

7 Moore, Federal Practice (2d ed. 1970) . . . . . . . . . 49

Note, "Developments in the Law--Employment Discrimi

nation and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964," 84 Harv. L. Rev. 1109 (1971) .................... 41

Note, "Legal Implications of the Use of

Standardized Ability Tests in Employment

and Education," 68 Colum. L. Rev. 691 (1968). . . . . . 42

2 Wigmore, Evidence (3d ed. 1940) . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

-vxi-

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ii

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 3

A. Proceedings Below 3

B. The Decision Below 3

C. The Issues On Appeal 11

D. Jurisdiction 14

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN

DENYING PLAINTIFFS SPECIFIC

RELIEF IN THE FORM OF EMPLOYMENT

OFFERS, BACK WAGES, AND OTHER

BENEFITS. 15

A. The Proper Legal Standard 16

B. The Defense 17

C. Pxaintiffs' Evidence 21

D. Checking Back 23

E. The Rights of Plaintiffs to

Specific Relief 24

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO ORDER AFFIRMATIVE HIRING RELIEF

FOR MINORITY PERSONS AS A CLASS. 28

7\ rnl-, TYT/~\ 4 /-tT-i 4- -P 71 in 4-Vi /s 4 4- . » -» nTU 4 —•

and Other Circuits. 29

B. The Rationale For Affirmative

Class Relief in This Case. 33

C. The Available Affirmative Remedies 38

III. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO ENJOIN THE ADMINISTRATION OF

UNVALIDATED EMPLOYMENT TESTS. 42

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING

TO GRANT ATTORNEY'S FEES AT THE RATE

REQUESTED BY PLAINTIFFS. 44

V. THE DISTRICT COURT WAS WITHOUT

JURISDICTION TO GRANT DEFENDANTS'

MOTION TO MODIFY JUDGMENT. 48

CONCLUSION 52

TABLE OF CONTENTS

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-1136

WILLIE L. MORROW and JEROME MANGUM,

individually and on behalf of all

others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs~appellants-

cross-appellees,

versus

GILES W. CRISLER, Commissioner of

Public Safety of Mississippi, et al.,

Defendants-appellees-

cross -appellants .

Appeals from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Whether the plaintiffs and one member of the

plaintiff class, who were refused application forms to apply

for patrolman positions on the all-white Mississippi Highway

Patrol, were subjected to the defendants' pattern and practi

of racial discrimination in hiring and employment practices

and therefore are entitled to offers of employment, back pay

for wages lost, and other financial benefits and emoluments

lost as a result of one defendant's refusal to provide them

with application forms.

2. Whether, having found that the defendants and

their predecessors engaged in unlawful racially discriminatory

employment practices up to the eve of the trial resulting in

the total exclusion of blacks from other than the most menial

service positions since 1938, the district court erred in

failing to order affirmative hiring relief for qualified black

persons as a class to overcome the effects of past discrimination.

3. Whether, having found that the defendants had used

as a condition of employment with the Highway Patrol intelligence

and spelling tests which had not been validated for a relationship

with good job performance, the district court erred in failing to

order an unequivocal prohibition against the use of unvalidated

employment tests as a condition for employment.

4. Whether the amount of the award of attorney's fees

was adequate as a matter of law and on the facts presented,

especially when it is inconsistent with uncontradicted evidence

on the record showing the average s Lcmuard hourly for civil

cases in the area.

5. Whether the district court had jurisdiction to grant

a motion for relief from judgment to exempt defendants from the

terms of the final injunction in filling certain specified positions,

while these appeals were pending, when the motion failed to allege

an adequate reason for relief from judgment, or any reasons at

all, and when the defendants failed to meet their burden of proof,

or to present any evidence at all, why the motion should have been

granted.

2-

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an appeal in an affirmative suit for equitable

relief on behalf of two black plaintiffs and those similarly

situated who were refused application forms to apply for

positions on the all-white Mississippi Highway Patrol and who

were otherwise denied equal employment opportunities with the

Patrol and the Department of Public Safety. The district court

granted partial judgment for the plaintiffs, but failed to grant

specific relief to the unsuccessful black applicants, sufficient

affirmative relief by way of minority preference or quota hiring

to overcome the effects of past discrimination, an unequivocal

prohibition against the use of unvalidated employment tests, or

adequate attorney's fees. Further, after the final judgment had

been rendered, the district court modified it to exempt several

important positions from the terms of the decree.

A . Proceedings Below

Plaintiffs Willie L. Morrow, a black Vietnam veteran

with police experience j_n the; Air Force, and Jerome Manmim. a

black college student, unsuccessfully sought application forms

to apply for patrolman positions at the Personnel Office of the

all-white Mississippi Highway Patrol on June 1, 1970 (Morrow),

June 4, 1970 (Morrow and Mangum) and on June 12, 1970 (Mangum)

1/

App. 47-172. Believing that they had been refused application

forms because of their race, they commenced this action on July

1/ The abbreviation "App." refers to pages in the Appendix

filed in this appeal.

-3-

J2/

30, 1970 on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated

seeking declaratory and injunctive relief against racial discrimi

nation in hiring and other employment practices by the Highway

Patrol and the Mississippi Department of Public Safety, of which

the Highway Patrol is a part. Their complaint alleged Federal

jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1343 to secure

rights guaranteed by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the

United States Constitution, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 through 1983, and

because Federal funds had been granted to the Patrol, Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d et seq.

Declaratory relief also was requested under 28 U.S.C. §§ 2201

and 2202. App. 1-13.

The defendants are the Governor of Mississippi, the

chief executive officer of the state who has general supervisory

authority over the Department and Patrol (App. 441), the

Commissioner of Public Safety, the chief executive officer of

the Department and Patrol (id.), the Assistant Commissioner of

Public Safety who is also the Chief of Patrol (App. 441-42), and

the Personnel Officer of the Department and Patrol responsible

ror personner puixcitb auu ijiuucuuj.cd . £App. 112) .

The district court on February 12, 1971 denied motions

to dismiss the action and for summary judgment in an opinion

holding that the district court had jurisdiction of the parties

and the subject matter of the complaint, that the complaint met

2/ The district court in its final decision defined the class

to include "all qualified Negroes who have applied or will apply

in the future for employment with the Mississippi Department of

Public Safety and/or the Mississippi Highway Safety Patrol, all

the present Negro employees of the Department and the Patrol,

and all future employees of the Department and the Patrol."

App. 462.

-4-

the requirements of a Federal class action, that the defendants

were not immune from the action, and that the allegations of the

plaintiffs and the statistics presented precluded summary judg-

-1/ment (Opinion R. 104, Order R. 125). The defendants answered

on February 19, 1971 admitting the race and residence of the

plaintiffs and the official capacities and responsibilities of

the defendants, but denying the other material factual and

legal allegations of the complaint (App. 16-19), A motion

for preliminary injunction to freeze new white hiring pending

final decision was denied on June 10, 1971 when the defendants

agreed to postpone an imminent recruit training class and

finally to provide the black applicants with application forms

(Opinion R. 355, Order R. 358).

In the absence of an agreement between the parties to

settle the lawsuit, a final hearing was held on June 28 and 29,

1971, The plaintiffs produced 33 documentary exhibits, including

depositions and employment statistics contained in answers to

interrogatories, which were admitted in evidence, and the testimony

of six witnesses: (1) and (2) plaintiffs Morrow and Mangum, who

testified regarding the refusal of defendant Snodgrass to provide

them with application forms for patrolman positions in June,

1970, and again on June 1, 1971 (3) Owen Glenn Coker, a black

Vietnam combat veteran who was turned down in his requests to

defendant Snodgrass for application forms in January and April,

1971, (4) Gary E. Brown, a native white Mississippian who

3/ The abbreviation "R." refers to pages in the Record on

Appeal. The decision of the district court denying defendants'

motion to dismiss is reported at 3 CCH Employment Practices

Decisions (hereinafter "EPD") 1[ 8119.

-5-

succeeded in obtaining an application form from the Patrol

personnel office in early June, 1970, (5) Edwin N. Williams,

a white Mississippi newspaper reporter who called Highway Patrol

headquarters in June, 1970, regarding the availability of

application forms and was told he coul'd go down to the head

quarters and pick one up, and (6) Aaron E. Henry, president

of the Mississippi State Conference of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People and life-long resident of

Mississippi, who testified regarding the reputation of the

Highway Patrol for racial discrimination in employment.

The defendants produced five documentary exhibits

showing for the first time a written policy banning discrimina

tion in hiring and employment, which had been issued in writing

a week before the trial, and called two witnesses, defendant

Commissioner of Public Safety Giles W. Crisler and defendant

Personnel Officer Charles E. Snodgrass, who denied the charges

of racial discrimination in hiring practices but failed to offer

any explanation for the statistics presented.

The United States through the Civil Rights Division

of the Department of Justice had been permitted to participate

amicus curiae by order signed June 1, 1971 and filed a memorandum

supporting plaintiffs' case but offered no evidence.

B . The Decision Below

The district court found that the Mississippi Highway

_4/

Patrol, established in 1938 , has never in its history employed

a black person as a sworn officer even though blacks have always

comprised a substantial percentage of the state's population

4/ Miss. Laws, 1938, ch. 143.

-6-

and currently represent 36.7 percent of the total (1970 Census)

5/

(App. 450). As of April 15, 1971, the court found that of the

27 bureaus within the Department of Public Safety, only two--the

Maintenance Bureau and the Training Academy— had any black

employees at all, and these were employed in the most menial

positions as janitors in the Maintenance Bureau and cooks at

the Training Academy. The employees of all the other bureaus

within the Department all were white, including all clerical

and secretarial personnel and sworn officers. The Department

employed a total of 743 persons, and only 17 of these, the

janitors and cooks, were black, and these statistics had been

the same since 1968. The defendant administration since January

1, 1968, had hired 107 persons for patrolmen, all of whom were

white. App. 450-51.

The Court held that these statistics, unrebutted and

unexplained by the defendants, showed "a pattern and practice

of racial discrimination in hiring and employment practices,

albeit unintentional, in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981 and

03 .̂Hpp . *2 u u / .

The district court also found racial discrimination

in the recruitment, selection and training of applicants.

"Favoritism and partiality have been shown to those applicants

[hired for positions with the Department and the Patrol] having

relatives, friends and acquaintances on the all-white Patrol"

5/ At the time of trial the Patrol had an estimated 378 sworn

uniformed white officers (Crisler testimony, App. 280).

-7-

and the court found this to be a factor accounting for the

racial composition of the Department and Patrol (App. 457).

The application forms used by the Department and Patrol required

the listing of the applicants' relatives employed by the State

and his friends and acquaintances employed by the Patrol, and

of the 107 whites hired as patrolmen during the defendant

administration, all but twelve listed friends or acquaintances

employed by the Patrol and forty-two listed relatives employed

by the State (App. 455). Concerning recruiting, the court found

that although there were television and radio stations and

newspapers which reached a large portion of the black community

in Mississippi, neither the Department nor the Patrol had

advertised the availability of jobs in any of those media or

in any other news media in the State (id.). Most of the presently

employed patrolmen learned of vacancies and the acceptance of

applications through word of mouth communications from incumbent

patrolmen who were their friends or relatives, and the majority

of the clerical positions in the Department were filled by walk-

ins, many of whom were recommended by incumbent employees (App. 454).

The court further determined that the officers of the

Public Relations Bureau carried on a recruitment program by

presenting speeches and programs for civic clubs, church groups,

and student groups throughout Mississippi, and that included in

those programs were presentations on the employment opportunities

and qualifications for positions with the Department and Patrol.

The audiences for such programs have been predominantly white.

Further, prior to the trial the Public Relations Bureau had

shown to groups of students as part of career day programs a

film on the operations of the Law Enforcement Officers Training

Academy in which all the recruits, officers, instructors, and

-8-

other Academy personnel were white except the black cooks and

food servers in the cafeteria. App. 455-56.

On the issue of testing, the district court found that

the defendants had required applicants for patrolmen positions

to pass two tests, the Otis Quick Scoring Mental Ability Test

and an oral spelling test of which no record is kept, neither of

which "has been validated to determine whether there is a

significant correlation between high scores on the test and good

performance as a patrolman" (App. 453).

Prior to the promulgation of a new regulation resulting

from this lawsuit, the Department of Public Safety had no written

rules or regulations prohibiting the use of derogatory racial

terms or epithets by patrolmen, and terms such as "nigger" had

been used by patrolmen in addressing blacks (App. 456).

Finally, the court found that black persons had been

discouraged from applying for positions with the Department and

Patrol because these agencies "have had a reputation throughout

the State of Mississippi, and particularly among the Black

communities, as being an all-White Department and Patrol" because

-P 4_U ^ —IT „-U 4 -U -------------1 i J _ < - . ■> — -■

w WJ_ u x c r a t i U X a u u <J J_ "UXie

bias shown toward applicants having relatives, friends and

_§/acquaintances on the Patrol force (App. 457).

6/ The evidence also shows that black people in Mississippi are

not only aware of the racially discriminatory hiring policies of

the Patrol, but also view the Patrol as a repressive force of the

white community against the black community, which image also would

deter applications from blacks. The Mississippi Commission on Law

Enforcement, the state law enforcement planning agency appointed

by the Governor, approved in its 1970 report the conclusion of a

study by the International Association of Chiefs of Police, which

defendant Commissioner Crisler also approved by his affirmative

vote for adoption, which states:

"A synthesis of the opinion of the Negro

community about the Mississippi Highway

Safety Patrol seems to suggest that it,

-9-

On cn O jL> ci S X S OX

admitted by defendants (see Pre-Trial Stipulation of Facts

(Tr. Ex. P-8) par. 7 ) and uncontradicted in the record, the

district court entered a detailed decree which declares the

rights of the plaintiffs and plaintiff class and enjoins

defendants and their successors in office from discrimination

against black applicants or employees in hiring, training,

assignments, transfers, promotions or discharges. The court also

ordered a five-year freeze on hiring qualifications and standards,

prohibited preferences or favoritism toward friends or relatives

of incumbent employees, ordered discontinuation of visual aids

implying a whites-only hiring policy in recruiting, required

notice and advertising to the black community prior to filling

new vacancies, required recruitment at black educational

institutions, prohibited use by Department employees of deroga

tory racial epithets, and required extensive record-keeping to

insure compliance with the decree. APP- 475.

(cont1d)

too, represents in the Negro mind

another repressive force of the white

community. This feeling appears to be

based upon several factors. One, already

mentioned, is that the Highway Patrol has

appeared as a secondary police force at the

scene of disturbances in which Negroes,

and particularly young Negroes, were the

focal point of attention. A second cause

for the feeling is based upon the allegation

that there is differential treatment of

Negroes in the manner of enforcement of

traffic laws by the Highway Safety Patrol.

This appears to be particularly acute in

the rural areas of the state. A third

reason for the feeling would be that the

Highway Safety Patrol is an all-white

institution. It is acknowledged by most

people concerned that no significant effort

has been made to integrate the Patrol."

(App. 2 87-88).

-10-

C. The Issues On Appeal

In spite of the overwhelming statistical and other

evidence demonstrating a pervasive general policy of the defendants

of denying equal employment opportunities to black applicants

and employees, the district court held that plaintiffs Morrow and

Mangum had not been discriminated against because of race when

they were denied application forms, but that this refusal was

solely because of an employment freeze or embargo in force and

effect during that period caused by a lack of funds to hire new

employees (App. 462-63) . The court also found, however, that

the three applicants, Morrow, Mangum and Coker "met all objective

prerequisites and requirements to permit them to apply for member

ship on the Patrol" (App. 445), that the application forms of

patrolmen hired during the defendant administration contained six

v(actually eight) applications bearing dates within the period of

this so-called embargo (App. 447), that the defendant Personnel

Director Snodgrass admitted accepting the completed application

form of a white applicant, Richard B. Peden, only three days

7/ The collection of aDDlication forms of appl i wnt-s for- ps-t-rn) -

man positions who have been hired since January 1, 1968 (Trial

Exhibit P-11) shows the names of the following whites with the

indicated dates of their applications for patrolman positions:

Clyde Dennis Faust

Chelsie Wayne Miller

Tommy Gail Walters

Larry Wayne Muse

James Clyde Wall

Richard Breeland Peden

Dennis Wayne Abel

Joseph Samuel Gonce

March 9, 1970

March 16, 1970

April 23, 1970

May 4, 1970

May 7, 1970

June 15, 1970

September 17, 1970

September 17, 1970

These forms are reproduced in the Appendix, pp. 500-507. All of

these applicants were enrolled in the September, 1970 recruit

training class and subsequently appointed to patrolmen positions.

See defendants' answers to plaintiffs' second interrogatories,

par. 11 (Tr. Ex. P-15).

-11-

after denying Mangum an application and eleven days after denying

Morrow an application (App. 449), and that three months after

refusing application forms to blacks the defendants had convened

an all-white recruit school of twenty-two white recruits (some

of whom had applications bearing dates within the so-called

embargo period) "without notice to the Court or the plaintiffs"

(App. 436). The court also denied specific relief to the plaintiffs

on the basis 'of testimony that defendant Snodgrass had requested

them to return to his office in September, 1970 and they had failed

to do so (App. 463).

Also in its final order the court denied plaintiffs'

request for affirmative hiring relief in the form of a minority

preference or a racial quota system that would increase the number

of blacks on the Patrol to approximate the percentage of blacks

in the state as a whole. (Judgment % D, App. 483). The court

failed to give any specific reasons in its decision for refusing

to grant this requested relief.

The provisions of the final order regarding tests do not

require validation of all tests administered to applicants for

p o s i t w i t h the Department or Patrol. In par. 2(b) of the

order, the court banned the use of any standardized general

intelligence test or the Otis Quick Scoring Mental Ability Test

"or any other tests which have not been validated nor proved to

be significantly related to successful job performance, but

simultaneously in the same paragraph required that all tests be

conducted in compliance "with the regulations adopted by the

[Mississippi] Classification Commission, including the giving of

examinations which are standard nationally approved tests that

are administered in an objective manner" (App. 477-78). The

-12-

regulations of the Mississippi Classification Commission, if

they exist, do not appear in the record and the decree does not

require validation of MCC-approved unvalidated tests.

The court in its final decree awarded counsel for the

plaintiffs only $500 in attorney's fees in the absence of any

record on hours spent on the case or the standard hourly rate

in the area (App. 483). Plaintiffs then filed a motion to amend

judgment to increase the amount of the award to $6060 and supported

the motion with an itemization of time spent on the case, which

was not contested by defendants, and affidavits showing the general

hourly rate ($30 per hour) charged by attorneys for civil cases in

the Jackson area (App. 488-93, 496-97). The defendants responded

with affidavits showing the standard rate allowed by the state on

state legal work performed by private attorneys ($15 per hour) and

the hourly rate charged by one attorney on criminal cases appealed

to the state supreme court ($15 per hour) (App. 494-96). The

court denied plaintiffs' request to assess at the $30 per hour

rate, but did alter its judgment to assess at the $15 per hour

rate, increasing the award to $3000 (App. 498).

__ _ n i____ j._i_ — ~ - r -P 4 4- r-< f t n o 1 -in r lrrm o r\ +-

I l i iC C UiO UJ- on J ------------------ ------ j - ------ •

and after the notices of appeal and cross—appeal haa been filed,

the district court modified its judgment without the presentation

of any additional evidence and over the objections of the plaintiffs

to exempt filling the positions of Commissioner of Public Safety,

Assistant Commissioner of Public Safety (Chief of Patrol) Chief

Investigator, Director of the Law Enforcement Officers Training

Academy, Assistant Director of the Law Enforcement Officers Training

Academy, eight positions on the Governor s security force, and

-13-

the Executive Secretaries to the Commissioner and Assistant

Commissioner from the terms of the order, except that a simple

ban on racial discrimination in filling these positions was

_8/

retained. As a practical matter, this exemption of these

positions relieves defendants in filling these positions from

the decree's prohibitions on: use of unvalidated tests, applying

new standards or qualifications fox* five years, use. of application

forms encouraging nepotism or showing favoritism toward relatives

or friends of incumbent employees, filling positions without prior

advertising designed to reach the black community, and use of

derogatory racial terms and epithets, and also frees defendants

from record-keeping showing who has applied and the action taken

on applications, promotions, and discharges in these positions.

No reasons were given for the necessity of this modification of

the final judgment either in the motion filed by -the defendants

or in the order allowing these exemptions.

D. Jurisdiction

The district court rendered its final decision

granting part of the relief requested by plaintiffs on September

29 , 1971 (App. 432-74), reported at 4EPD 1[ 7563), and a conforming

Judgment and Order For Declaratory and Injunctive Relief was

entered on October 18, 1971 (App. 475-84, reported at 4 EPD

1[ 7541). Within 10 days of the final order, plaintiffs filed their

__§/ The motion for relief from judgment and the district court's

order granting the motion are included in the Addendum attached

hereto, Exhibits B and C.

-14-

motion to amend judgment on the issue of attorney's fees (App.

488), and on November 30, 1971 an order was entered increasing

the amount of the award of attorney's fees (App. 498) (reported

at 4 EPD 1[ 7584). Plaintiffs appealed from the final judgment,

as amended, on December 21, 1971 (R. 494), and the defendants

filed a cross-appeal on January 3, 1972 (R. 495). Subsequently

on January 13, 1972, the defendants filed their motion to modify

the judgment to exempt five executive, eight security force, and

two secretarial positions from the detailed compliance provisions

of the order (R. 499) and that motion was granted in an order

modifying the final judgment entered on January 14, 1972 (R. 502).

Plaintiffs took a second appeal from this Order on February 11,

1972.

The Court has jurisdiction of these appeals as

appeals from final orders pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN DENYING

PLAINTIFFS SPECIFIC RELIEF IN THE FORM

OF EMPLOYMENT OFFERS, BACK WAGES, AND

OTHER BENEFITS.________________________

The district court erred in failing to require defendants

to offer plaintiffs (and plaintiff class member Coker) recruit

positions in the next recruit training class, back wages lost as

a result of the refusal of the defendants to provide them with

application forms, and other benefits plaintiffs would have

gained if they had been allowed to apply and accepted for enroll

ment in the September, 1970, recruit training class. This error

15-

is based on the failure of the district court to apply the

appropriate legal standard to judge the facts presented and

the clearly erroneous factual conclusions resulting from the

failure to apply the proper legal standard.

A. The Proper Legal Standard

The finding of the district court that Morrow, Mangum,

and Coker were not denied applicationforms to apply for Patrol

positions because of their race is inconsistent with its holding

that the defendants were guilty of a "pattern and practice of

racial discrimination in hiring and employment practices" (App.

466). A strong statistical showing of a pervasive general

policy of racial discrimination in the hiring of blacks furnishes

a "strong inference" that a black applicant rejected during this

period was refused employment for racial reasons. Parham v.

Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433 F.2d 421, 428 (8th Cir.

1370). This court repeatedly has held in the teacher employment

cases that when a black teacher or principal suffers adverse

administrative action with regard to his employment, and when

the educational processes had historically been segregated, the

_£/

V\ 1 1 ’V"* ̂ (71 n f~ \ "P n 'Vv (~i T •»—%/"■» ~! VN f t f VI 1" V-N M P 1 v-1 ^ J- /-> w. r-4 -1— — — J — \ - — _ »

onto the defendant state agency to prove that its adverse

employment action is non-discriminatory. Lee v. Macon Co. Bd.

of Educ. (Muscle Shoals School System), No. 71-2963, 5th Cir. ,

Dec. 28, 1971 (slip op. at 19); United States v. Jefferson Co.

Bd. of Educ., 372 F.2d 836, 895, aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d 385

(5th Cir. 1967), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 840 (1967). Accord:

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Bd. of Educ., 364 F.2d 189 (4th

Cir. 1966) (en banc); Rolfe v. Co. Bd. of Educ., 391 F.2d 77

9/ Singleton v. Jackson Mun, Sep. Sch. Dist., 419 F.2d 1211

(5th Cir. 1969"), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 1032 (1970).

-16-

(6th Cir. 1968). Under these circumstances the defendant state

agency with a prior history of racial discrimination must show

by "clear and convincing evidence" that its action was taken for

other than racial reasons. Chambers, supra, 364 F.2d at 192.

The defendants in this case, whose discrimination (and

that of their predecessors) goes back to 1938 and who failed to

comply with the mandate of the Constitution until forced to do so

by litigation, stand in the same position and should be judged by

the same standards applied to other state agencies in the above-

cited cases. The district court in this case, by failing to draw

the required presumption of racial discrimination from the failure

of the defendants to perform the simple act of providing these

black applicants with application forms, failed to apply the proper

9 a/

legal standard in judging the facts presented.

B . The Defense

Judged by the proper legal standard, what "clear and

convincing evidence" have the defendants presented to show that

their refusal for one year (up until June, 1971) to provide plain

tiffs with application forms to apply for Patrol positions was

justified for other than racial reasons? Their defense is that

when the plaintiffs visited the Personnel Office and requested

application forms to join the all-white Highway Patrol there just

happened to be in effect for the first time anyone can remember,

App. 289-90 (Crisler); App. 381-82 (Snodgrass), an employment

freeze or embargo on the hiring of new patrolmen and other

personnel. The testimony of the defendants is vague and

9a/ And therefore its findings of fact on this issue are not

insulated from full review by the "clearly erroneous" restriction

of Rule 52(a), F.R. Civ. P. United States v. Jacksonville Terminal

Co., 451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, filed, 40 U.S.L.W. 3379

(2/7/72); United States v. Pickett's Food Service. 360 F.2d 338,

341 (5th Cir. 1966).

-17-

contradictory on the details of this alleged freeze, Commissioner

Crisler testified that this freeze was instituted "about the

middle of the year," May or June or "somewhere thereabouts"

(App. 290) and ended "after July, somewhere thereabouts" (id.).

Personnel Director Snodgrass, on the.other hand, testified that

the freeze commenced "in February or early March, I think it was

the latter part of February" (App. 318) and ended on June 30 to

replace clerical personnel (App. 358) and in the latter part of

July for patrolman positions (App. 367).

Commissioner Crisler initially testified that he

instructed Snodgrass "to cease employing and accepting applica

tions on anyone" (App. 291) but later changed his testimony to

say that he "advised him .[Snodgrass] to stop employment and I

assume that would be the same as not accepting applications too"

(App. 292, emphasis added). There is nothing in Commissioner

Crisler's testimony to indicate that he specifically conferred

with Snodgrass or instructed his personnel officer either to

cease accepting or giving out applications or that he even under

stood the freeze to include an embargo on distributing applications,

ana tns wanness dvuiutiu i_luu3 on that rscuc (App.

10/

291-97). Snodgrass initially testified on direct examination

that it was the "decision of the Commissioner" (App. 320) not

to give out any applications during this period, but then changed

his testimony to say that it was "a joint idea" (id.) and then

10/ The district court found that the Commissioner of Public

Safety "did not specifically instruct Snodgrass not to give out

any application forms" (App. 447).

-18-

changed his testimony again on cross-examination to say that

not giving out applications was his own idea, that he discussed

it with the Commissioner, and that the Commissioner specifically

approved the alleged policy of not giving out any new applica

tion forms (App. 354-55).

The defendants testified that all these alleged actions

and instructions were made orally, and nothing about this alleged

hiring freeze was reduced to writing (App. 293 (Crisler), App. 354

(Snodgrass)). The defendants called no witnesses from the

financial department to support the testimony that the freeze

was required by lack of funds, which testimony from the defendants

admittedly was vague and incompetent (App. 355-56), and the

defendants' testimony was not corroborated by anyone not a

defendant who could give independent testimony that the freeze

existed or that anyone other than the plaintiffs had been

refused application forms.

The Director of the Public Relations Bureau, Thomas G.

Sadler, whose bureau handles, among other things, the recruitment

program of the Department of Public Safety and Highway Patrol,

~ n ^ 4̂ ^ ■>-. -̂3 +- <-< * o 4- T3 +- o m e n 4- g r~t rR -{- g 4~ 1 f l p f l TTl h*S.Cv

deposition that as far as he knew there have never been any

employment embargoes or freezes on hiring for the Highway Patrol

(Sadler dep., June 3, 1971, Tr. Ex. P-1, pp. 14-15).

Even if the Highway Patrol was precluded for lack of

funds from hiring any new personnel at the time the plaintiffs

requested application forms, the Record does not reveal any good

reason why a freeze on new hiring prevented the defendants upon

plaintiffs' request from handing out application forms which

could have been returned when the freeze was lifted and new

-19-

hiring resumed. Snodgrass testified that at the time plaintiffs

requested applications from him he had the forms available in

his office (App. 350) and there was no physical reason preventing

him from giving the forms to the plaintiffs (App. 364). Snodgrass'

stated reason for the alleged freeze on giving out applications

was that when he took office as Personnel Director there were in

the files between one and two thousand pending applications for

Patrol positions, which he then threw away, and he did not want

to create another backlog or build-up of applications for six or

eight months during a hiring freeze which would have required

each application to be up-dated for current information at the

end of the freeze (App. 316-20). But even this concern did not

preclude the defendant from offering the plaintiffs application

forms to permit them to collect the documents required with

instructions to return them with current information in September,

or whenever the new fiscal year began and the freeze lifted.

Further, and to negate the entire defense, Snodgrass

admitted in his testimony that his alleged policy did not prevent

him from giving preferential treatment to a white applicant,

Pickard B. Peden , whose a p p l I p a t - i n n h o s c lm i h h o d l v- a r p p n t p r l o n n r

about June 15, 1970, three days after refusing plaintiff Mangum

an application form and eleven days after refusing plaintiff Morrow

an application form (App. 336-38, 358-64). After accepting

Peden's completed application form "as a courtesy to a fellow

officer" also white, who handcarried the application to Snodgrass,

Snodgrass put it in his desk drawer and processed it "when we

began processing other applications" (App. 338) apparently without

any up-dating before Peden was enrolled in the September, 1970

recruit class. This testimony on Snodgrass's part is tantamount

-20-

to an admission of racial discrimination on the part of the

11/

Department's Personnel Officer.

Such is defendants' case. Judged by the proper legal

standard which the district court should have applied, defendants

have failed to rebut by "clear and convincing evidence" the

necessary presumption that their failure to px'ovide plaintiffs

with application forms was part of the over-all "pattern and

practice of racial discrimination in hiring and employment

practices" which the district court found to exist. In fact,

Snodgrass's admitted preferential acceptance of Peden's applica

tion at the same time he was denying plaintiffs application forms

negates the defense and further reinforces the presumption.

C. Plaintiffs' Evidence

This conclusion of racial discrimination, then, can be

reached even without a detailed analysis of the testimony of

plaintiffs' white witnesses which, without explanation, is not

discussed in the decision of the district court. At the same

time the plaintiffs were refused application forms for Patrol

employment, Gary E. Brown, a native white Mississippian, requested

as a test and did receive from a secretary in the Personnel Office

at Patrol headquarters in Jackson .an application form for Patrol

employment (App. 198-211). Similarly, Edwin N. Williams, a

reporter for the Greenville Delta-Democrat Times and also a

white Mississippian, called Patrol headquarters on June 19, 1970,

11/ Both defendants admit that when the new hiring commenced,

after this lawsuit had been filed and the defendants had been

served with process, no effort was made to contact the plaintiffs

to offer them application forms to allow them to be enrolled in

the September, 1970, all-white recruit training class (App. 307-

OS, 380).

-21-

and was told by an officer in the Public .Relations Bureau

that he could go down to Patrol headquarters and pick up an

application and that it did not have to be filled out there

(App. 211-223). Their testimony is consistent with the finding

of the court regarding defendants' policy of discrimination and

is uncontradicted and unimpeached in the record.

The district court's failure to apply the proper legal

standard is perhaps most strikingly illustrated by its treatment

of the most recent application forms of white persons hired for

patrolmen positions, six of which bear dates between February

and July, 1970 (App. 500-507). Snodgrass testified that there

was no regular procedure: governing dates on applications, and

that the date on the application could reflect "the day he [the

applicant] got it [the application form], the day he filled it

out or the day he mailed it in and in some instances when he

forgets to date it, I put a date on it [when it is received, as

in Peden's case]" (App. 336). Three of the four possible

explanations for the dates on the applications support the

inference of racial discrimination, and the district court

should have required the defendants to rebut the inference by

direct evidence. Since the defendants failed to produce their

own patrolmen to testify regarding the circumstances of their

applications, which they had the power to do, the only rational

inference is that such testimony would have been adverse to

defendants' case. Interstate Circuit, Inc, v. United States,

306 U.S. 208, 226, 59 S.Ct. 467, 83 L.Ed. 610 (1939); 2 Wigmore,

Evidence §§ 285-91 (3d ed. 1940).

-22-

D. Checking Back

The district court, in denying specific relief to the

plaintiffs, placed great emphasis on the testimony that Snodgrass

asked them to return to his office in September and they failed

12/

to do so, against the advice of their attorney. First, if they

were denied application forms in June, 1970, because of their race,

which the Record clearly shows, then they had no obligation, after

the lawsuit was filed, further to test the defendants' discrimina

tory policy. As Jerome Mangum put it, "If I went back in September

I would still be black" (Tr. 124). Second, although there is

evidence that Snodgrass may have asked the plaintiffs to return in

September, his own testimony reveals that he gave them no specific

assurances that they would receive application forms if they did

so: "He [Morrow] was told as all the rest of them were, that he

could check back the first part of September and we would probably

know something by then." (App. 327). (Emphasis added.) In response

to two leading questions by the district judge, Snodgrass served

his own cause by assuring the court that if the plaintiffs had

t — - — i - t 2 — ^ s .X . J r * - f t ^ 1 4- V i r v r l i n l - n r*f~\ 11 y 4-

X. £* / W V L-J. J. *-> U—L U i i v j w x - / j v * . * * . - / - — — — _ — -

required the plaintiffs to testify on cross-examination regarding

conversations with and advice from their attorneys on whether they

should repeat their futile visits to Patrol headquarters in

September, 1970, (App. 110-11, 160). This testimony is hearsay

and immaterial, and the ruling of the district judge requiring

plaintiffs to testify to advice from counsel regarding litigation

strategy violates the privilege of the client to refuse to dis

close confidential communications between himself and his attorney.

C. McCormick, Evidence, ch. 10, esp. § 100 (1954). See Miss. Code

§ 8665(4); United States v. Ladner, 238 F. Supp. 895 (S.D. Miss.

1965). This is not an instance where disclosure may be required

on grounds of waiver of privilege by prior voluntary disclosure

or because of a challenge to the effectiveness of counsel or the

performance of his duties, United States v. Woodall, 438 F.2d

1317 (5th Cir. 1970) (en banc), upon which the district court

apparently relied in overruling the objection (App. Ill, 160).

-23-

"checked back" in September they would have been given application

forms and would have been processed for enrollment in the recruit

training class which began September 20 (App. 324-25). But these

retrospective assurances at the time of trial are contradicted

and impeached by the more contemporary affidavit of Snodgrass

himself, executed on August 24, 1970, and filed with the court on

September 17, 1970, in which he implied that the next recruit class

was full and unequivocally stated:

"Any person desiring to make application to become

a uniform [sic] member of the Highway Patrol would

be discouraged from doing so at this time, but upon

their insistence would be allowed to do so. A

prospective applicant would be informed that there

is no hope for his employment within the next six-

month period and advised to recheck with the

personnel office after six months." App. 14.

If the plaintiffs were denied application forms for

Patrol employment because of their race, they are entitled to

specific relief regardless of their failure to "check back" in

September after their suit had been filed. Further, even if

they had checked back in September, the evidence on file with the

court at that time indicates that they would "be discouraged"

from applying and that there would be "no hope" for employment

E . The Rights of Plaintiffs To Specific Relief

The district court in its decision specifically held

that Morrow, Mangum and Coker at the time of their requests for

application forms "met all objective prerequisites and require

ments to permit them to apply for membership on the Patrol"

(App. 445). Defendant Snodgrass, the Personnel Director, after

carefully listening to all the testimony in the case, admitted

that he knew of nothing which would disqualify the plaintiffs

-24-

from applying for or being trained and hired for patrolmen

positions (App. 35Q-51). He also testified that there were white

applicants who had been accepted for training in the September,

1970, recruit training class who were less qualified by way of

prior police experience and educational background than the

plaintiffs and Coker (App. 391).

(1) Employment offers. Black applicants for employ

ment who have not been allowed to apply or who have not been

hired because of a policy of racial discrimination in hiring

are entitled to specific relief, including offers of the first

available employment for which they are qualified. This Court in

Local 53, Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir.

1969), held that requiring the defendant union immediately to

admit four minority group applicants into membership and to

refer nine others for work was appropriate specific relief to

rectify the union's discriminatory admissions and referral

practices. Similarly, in United States v. Ironworkers Local 86,

443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, ___ U.S. , 40

U.S.L.W. 3264 (Nov. 19, 1971), the Ninth Circuit approved a decree

n r r l b r i yq rr V n n 1 r l i n r r n r v r i p f v - i

referrals to previous racial discriminatees along with an affirma

tive recruiting program. The preliminary injunction issued in

United States v. Central Motor Lines, Inc., 325 F. Supp. 478 (W.D.

N.C. 1970) required the employer to hire six black drivers

"promptly", apparently within two weeks from the date of the order.

Also, Rios v. Enterprise Assn, Steamfitters, Local 638, 326 F.

Supp. 198 (S.D. N.Y. 1971) (preliminary injunction requiring union

to admit three plaintiff applicants to full membership); Clark v.

American Marine Corp., 304 F. Supp. 603 (E.D.La. 1969) (reinstate

-25-

ment of plaintiffs required after discriminatory refusal to

rehire) .

Offers of employment are not only required in cases

arising out of violations of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

13/

of 1964, but also in instances of employment discrimination

by state agencies, as in the teacher discharge cases where this

Court uniformly has required school boards to reinstate discrimi-

nated-against teachers and principals to their former positions

or to equivalent positions within the school system. See, e.g.,

Lee v. Macon Co. Bd. of Educ. (Muscle Shoals School System),

supra. It is not enough that the defendants merely have agreed

to process the now completed application forms of Morrow, Mangum,

and Coker, if they retain the discretion not to enroll them in

the next recruit training class: "A court of equity ought to do

justice completely, and not by halves." Camp v. Boyd, 229 U.S.

530, 551, 33 S.Ct. 785, 57 L.Ed. 1317 (1913).

(2) Back pay and other lost benefits. When persons

have been denied employment for racial reasons, equity requires

that they be restored to the financial position in which they

WCllicl U CXV'"' ”U X. JC* J-U— ------1.. T-----------------------.------J3-----------------I ~ 1 ml____T_________ _ _

award is not punitive in nature, but is equitable relief designed

to restore the recipients to the economic status they would have

attained but for the wrongful acts of the defendant. Thus back

pay awards are expressly authorized in Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(5)(g), where they are "an

integral part of the statutory equitable remedy" for relief from

employment discrimination, Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.,

13/ 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.

-26

417 F.2d 1122, 1125 (5th Cir. 1969), and are normally granted

to successful plaintiffs in such cases. Culpepper v. Reynolds

Metal Co., 442 F.2d 1078 (5th Cir. 1971); Pettway v. American

Cast Iron Pipe Co. , 411 F.2d 998, 1007 (5th Cir. 1969);

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971)

cert, filed,40 U.S.L.W. 3251 (9/28/71); Bowe v. Colgate-

Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th Cir. 1969). Back pay awards

and other equitable financial relief also are part of the

"comprehensive remedy" of 42 U.S.C. § 1983, invoked here, "for

the deprivation of federal constitutional and statutory rights."

Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School Dist., 427 F.2d 319, 322

(5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 991 (1971). See also,

Horton v. Lawrence Co. Bd. of Educ., 449 F.2d 793 (5th Cir. 1971)

McFerren v. Co. Bd. of Educ. of Fayette Co., 4 EPD <j[ 7652 (6th

Cir. 1972); cf. Chambers V. United States, 451 F.2d 1045 (Ct. Cl.

1971) (applicant discrimination violative of Federal Executive

14/Order). Thus plaintiffs are entitled to the wages, seniority,

insurance and retirement benefits and the other emoluments of

office they would have received had they been allowed to

i u i ciiiwx jjccu aC u-c; va. r u i cao jju lxuxiucu j-ii

September, 1970, and subsequently hired in patrolmen positions.

14/ During 1970 and 1971 patrolmen were paid $400 per month

during recruit training and $490 per month after appointment.

Pre-Trial Order, Stipulations of Fact (Tr. Ex. P-8) par. 7(10).

-27-

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN FAILING TO

ORDER AFFIRMATIVE HIRING RELIEF FOR

MINORITY PERSONS AS A CLASS.___________

The district court in its final order denied the

request of plaintiffs for such affirmative hiring relief as would

require the defendants to increase the number of black officers on

the Highway Patrol, by minority preference or a racial quota

system, so that the percentage of blacks on the Patrol would

not significantly differ from the percentage of blacks in the

population of the state (36.7 percent) (judgment, par. D, App.

483). The court in its memorandum decision did not specifically

give any reasons for denying this relief. The denial apparently

was based on the representation of defendants that between the

trial and the date of the decision defendants had begun processing

application forms from 29 white applicants and 5 black applicants

and the court's finding that the defendants "have now begun

to take many steps toward and have made substantial progress in

promulgating policies and programs designed to insure equal

treatment to citizens of all colors . . (App. 461-62) a

* C f c r C v ,n A +- vn -v- /-> — 4- -v- -i o 1 nvoTm il r t a f i on n -f w r i f f p n n n l i C'i P> c;

prohibiting racial discrimination in employment practices.

Neither the fact that defendants may formally have

abandoned some of their racially discriminatory practices

during the course of litigation nor the finding that defendants

are now making "substantial progress" toward complying with

Federal constitutional guarantees should deter Federal courts

from exercising their duty where necessary to render a decree

requiring such affirmative action as will eliminate all the

-28-

effects of past discrimination. United States v. IBEW, Local

No. 38, 428 F.2d 144 (6th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400 U.S.

943 (1970); Local 53, Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d

1047, 1055 (5th Cir. 1969) ; cf. United States v. Sheet Metal

Workers, 416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969).

A. The Weight of Authority in This and Other

Circuits.________________________

The district court, by refusing to require affirmative

hiring relief for the class of discriminatees, under the circum

stances of this case abused its discretion by failing to follow

the teachings of the Supreme Court, applied in the employment

discrimination cases, that district courts have "not merely the

power but the duty to render a decree which will so far as

possible eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past as well

as bar like discrimination in the future." Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145, 154, 85 S.Ct. 817, 13 L.Ed.2d 709 (1965).

The relevant decisions in this and other circuits generally hold

that where the discriminatory employment practices of an employer

over a period of time result in an absence of, or severe dispro-

force or in certain job categories, district courts have a duty

to order affirmative employment relief to the disadvantaged class

to overcome the present effects of prior discrimination.

Thus, the Eighth Circuit in a very recent en banc

decision in a challenge to the discriminatory employment practices

of the all-white Minneapolis Fire Department, reversed a decision

of a panel of that court vacating a district court order requiring

defendants to give an absolute preference in new hiring to 20

-29-

minority applicants, and ordered the defendants to follow a one-

for-two hiring ratio (one minority group person for every two

whites hired) until 20 qualified minority group persons had been

hired. Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir. Jan. 7, 1972),

modifying and affirming 3 EPD i! 8205 (D. Minn. 1971). The full

court based its decision on the following considerations: (1) the

approval given by the Supreme Court in recent school cases to

mathematical ratios as "a starting point in the process of shaping

a remedy," Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S.

1, 25, 91 S.Ct. 1267, 28 L.Ed.2d 554 (1971); (2) the reputation

of the fire department in the black community for discrimination

in hiring practices, deterring black persons from applying without

assurances that blacks would be hired on more than a token basis;

(3) the testing procedures, used to rank applicants for considera

tion, which had not been validated to show any relationship to

successful job performance; and (4) while a one-to-one hiring

ratio might be required in areas with substantial minority

population, a one-to-two ratio would be more suitable to

Minneapolis conditions (6.4 percent minority, 4.4 percent black).

O 4 -w> 4 1 —n -v * 1 x -r 4— V T -I w 4- V n /'"* 4 4 - i - -i -w-N -T T-*-^ J — —̂ -L- ^

86 Ironworkers, 443 F.2d 544 (1971), cert, denied, 40 U.S.L.W.

3264 (Nov. 19, 1971) affirmed as necessary to overcome past

discrimination a district court order which, inter alia, ordered

three unions to establish "special" apprenticeship programs to

train overage and experienced blacks and to fill future training

classes to insure 30 percent black participation to the extent

that qualified blacks are available. See 315 F. Supp. 1202, esp.

-30-

at 1247-48 (W.D. Wash. 1970). The court also followed the weight

of authority in rejecting the defendants' contentions that such

relief established "racial preferences" in violation of the anti

preference prohibitions of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 f 42 U.S.C. § 2000e~2(j) .

In ordering affirmative hiring relief to the class of'

discriminatees, these circuits generally have been following the

lead of this Court set in the landmark Vogler decision, supra, in

which the Court sustained a district court injunction ordering, in

addition to immediate union admission and work referrals for

thirteen named individuals, one-for-one work referrals to provide

job opportunities previously denied minority group persons. In

its recent decision reviewing an adjustment to the procedures for

referring white worker's , the Court once again sustained the one-

for-one referral system as within the power of the court "to shape

remedies that will most effectively protect and redress the

rights of Negro victims of discrimination." Vogler v. McCarty,

Inc., 451 F. 2d 1236 (5th Cir. 1971).

This Court repeatedly has held that although an employer

m a y have abandoned discriminatory employment practices ana aaoptea

racially neutral employment criteria, even these criteria are

inadequate if they perpetuate or fail to eliminate the present

effects of prior racial discrimination. In these circumstances

district courts have the duty to grant affirmative relief to the

class of persons formerly discriminated against to eradicate the

present effects of prior discrimination: "Affirmative action is

necessary to remove these lingering effects." United States v.

Hayes Intern'1 Corp., No. 71-1392, 5th Cir., Feb. 22, 1972 (slip

-31-

opinion at 7, emphasis added). See Also, United States v. Jackson

ville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971) cert, filed, 40

U.S.L.W. 3379 (2/7/72) ; Local 189, United Fapermakers v. United

States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919

(1970); United States v. Hayes Intern11 Corp., 415 F.2d 1038

(5th Cir. 19 69) .

The most recent district court decision in this circuit

bearing on the issue presented in NAACP v. Allen, Nos. 3561-N,

2709-N, M.D. Ala., Feb. 10, 1972, opinion and order attached. A

black applicant who had been refused an application form and other

plaintiffs succeeded in proving on facts similar to this case a

"blatant and continuous" pattern of racial discrimination in hiring

by the Alabama Department of Public Safety, both as to state

troopers and supporting personnel. Correctly finding that courts

have the duty to eliminate the present effects of past discrimina

tory practices which have "permeated the Department of Public

Safety's employment practices", the district court ordered an end

to discrimination, one-for-one hiring until the state police force

is 25 percent black, training courses to include 25 percent black

participation, and one-for-one hiring fox' clerical, score taxrai,

and other supporting personnel. See also, Strain v. Philpott, 331

F. Supp. 836, 4 EPD UK 7521, 7562 (M.D.Ala. 1971) (ordering 50

percent black hiring ratio) and United States v. Frazer, 317 F.

Supp. 1079 (M.D.Ala. 1970) (ordering temporary appointments in

ratio of black to white population).

To summarize, most of the courts to consider cases of

employment discrimination have held that the duty of Federal

courts to eliminate the effects of past discrimination includes

the duty to fashion affirmative relief for minority persons as

32-

a class which guarantees, through a minority preference or

remedial quota, employment opportunities for the previously

deprived class. The courts have held that this affirmative

class relief should be provided despite (or possibly consistent

with) evidence that the defendants have abandoned their past

discriminatory practices, have adopted facially neutral criteria,

and are attempting in good faith to comply with the law, and also

in conjunction with (and not relying exclusively on) other

affirmative programs which include publicity and recruitment in

the black community. When such programs are designed to overcome

past discrimination, they are not preferential to the disadvantage

of whites, but are only remedial toward achieving a goal which

would have obtained but for the illegal discrimination. The

weight of authority in this and other circuits regarding the

requirements of affirmative relief dictates a modification of the

district court's order.

B. The Rationale For Affirmative Class

Relief In This Case

(1) The notion of the class action. The district

court permitted the plaintiffs uo maintain this suit as a class

action as provided by Rules 23(a) and 23(b)(2), F.R. Civ. P.

15/

(App. 462).

15/ Plaintiffs in their complaint defined the plaintiff class

to include

"all qualified Negroes who have applied or will in

the future apply for employment with the Mississippi

Department of Public Safety and/or the Mississippi'

Highway Safety Patrol, all qualified Negroes who have

been deterred from applying for employment with the