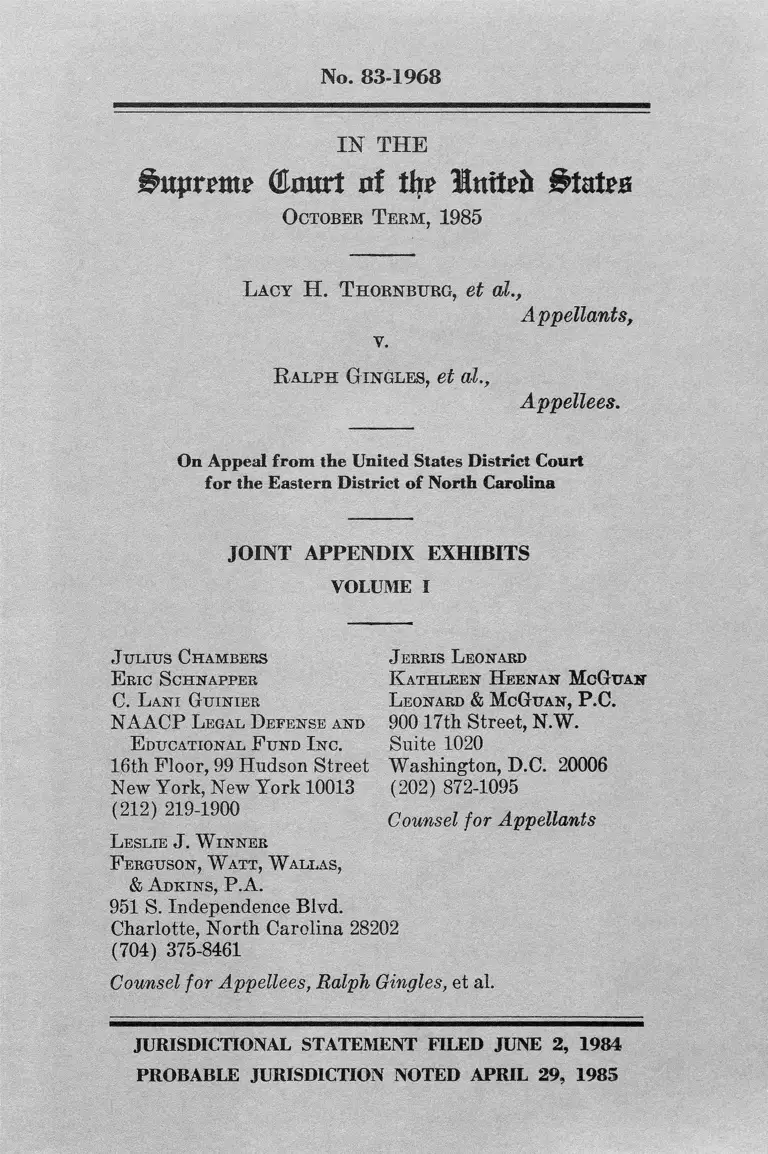

Thornburg v. Gingles Joint Appendix Exhibits Vol. 1

Public Court Documents

June 2, 1984 - April 29, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thornburg v. Gingles Joint Appendix Exhibits Vol. 1, 1984. 5afe1323-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e1fd6f3a-4347-49da-94c6-65a5843624b0/thornburg-v-gingles-joint-appendix-exhibits-vol-1. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

No. 83-1968

IN THE

(Etfurt at % Irnteii States

O c t o b e r T e r m , 1985

L a c y H. T h o r n b u r g , et al.,

Appellants,

R a l p h G i n g l e s , et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of North Carolina

JOINT APPENDIX EXHIBITS

VOLUME I

J erris L eonard

K a t h l e e n H e e n a n M c G u a n

L eonard & M c G u a n , P.C.

900 17th Street, N.W.

Suite 1020

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 872-1095

Counsel for Appellants

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

(704) 375-8461

Counsel for Appellees, Ralph Gingles, et al.

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT FILED JUNE 2 , 1984

PROBABLE JURISDICTION NOTED APRIL 29 , 1985

J u l iu s C h a m b e r s

E r ic S c h n a p p e r

C . L a n i G u in ie r

N A A C P L eg al D e f e n se a n d

E d u c a t io n a l F u n d I n c .

16th Floor, 99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

L e slie J . W in n e r

F e r g u so n , W a t t , W a l l a s ,

& A d k in s , P .A .

951 S. Independence Blvd.

Ex-1

PUGH/EAGLIN PLAINTIFFS’ EXHIBIT NO. 4

Table 1-A

Comparison of Black Population and Black

Representation in the North Carolina Legislature

1940-1982

Year

# of

Blacks

Population

Total Popu

lation

7c

Black

NC Senate

# o f 7t

Blacks Black

NC House

# o f %

Blacks Black

1940 981,298 3,571,623 28 0 0 0 0

1942 0 0 0 0

1944 0 0 0 0

1946 0 0 0 0

1948 0 0 0 0

1950 1,078.808 4,061,929 27 0 0 0 0

1952 0 0 0 0

1954 0 0 0 0

1956 0 0 0 0

1958 0 0 0 0

1960 1,156,870 4,556,155 25 0 0 0 0

1962 0 0 0 0

1964 0 0 0 0

1966 0 0 0 0

1968 0 0 1 .8

1970 1,126,478 5,082,059 23 0 0 2 1.6

1972 0 0 \>*_> 2.5

1974 2 4 4 o

1976 2 4 4 ■).

1978 1 2 3 2.5

1980 1,316,050 5,874,429 22 1 2 3 2.5

1982 1 2 11® 9.1

Sources: Thad Eure. X o rth C a ro lin a L e y i s la t ire D ire c to r 19S1-19S2. 198C4-19S4

Thad Eure. X o r t l i C a ro lin a M a n u a l. Raleigh: Publications Division. 1941-1979

LJ.S. Bureau of Census, 1940, 1950, 1900. 1970. 19X0

::Six of these were elected from majority black districts that the General Assembly was forced to draw by the

Federal Courts.

PLAINTIFF S EXHIBIT

11 App 3 Gingles

Appendix 3: “Effects of Multimember House and State Senate Districts

in Eight North Carolina Counties, 1978-1982”

CONDENSED SUMMARY TABLE 1

KEY (X,Y,Z,Q)

X = number of black

candidates

Y = total number of candidates

(including blacks)

Z = number of winning-

candidates

Q = number of winning black

candidates

Level of White Voter Support for Black Candidates vs. Black Voter Support for Black Candidates in Eight North Carolina Counties, House and Senate

Primary and General Elections in which there was at least one Black Candidate, 1978-1982.*

Proportion of Proportion of Proportion of Proportion of

white voters black voters white voters black voters

for black for black for black for black

GENERAL candidate(s) candidate(s) PRIMARY candidate(s) candidate(s)

(5) Mecklenburg & Cabarrus

(1, <>, 4, 1) 1978 Senate .41 .94 (i, 5. 4, 1) 1978 Senate .47 .87

(i, 5, 4, 0) 1980 Senate .2:1 .78

(1,7, 4, 0) 1982 Semite .94 (i. (i, 4, 1) 1982 Senate .32 .83

(9) Mccklenbui g

(1, (>, 4, 1) 1978 Senate .40 .94 (i, 5, 4, 1) 1978 Senate .50 .87

(i, 5, 4, 0) 1980 Senate .25 .79

(1, 1(5, 8, 0) 1980 House .28 .92 (i. lit. 8, l) 1980 House .22 .71

(1, 7, 4, 1) 1982 Senate .31 .94 (i, (!, 4, 1) 1982 Senate .33 .83

(2, 18, 8, 1) 1982 House .42 .29 .92 .88 (2, 9, 8, 2) 1982 House .50 .30 .79 .71

(5) Cabarrus

(1, (5, 4, 1) 1978 Senate .38 .92 (I, 5, 4, (1) 1978 Senate .35 .75

(1, 5, 4, 0) 1980 Senate .21 .79

(1, 7, 4, 0) 1982 Senate .37 .94 (1, li, 4, 0) 1982 Senate .80 .70

Polk wins in

1982 Meek. Sen.

goner.

Alexander loses

in 1978 Cabarrus

primary.

Polk loses in

1982 Cabarrus

primary.

Ex-2

TABLE 1 (continued)

Proportion of Proportion of

white voters black voters

for black for black

GENERAL candidate(s) candidate(s)

((>) Durham

(1, 4, 2, (l) 1978 Senate .17 .05

(Rep. B)

(1, 3, 3, 1) 1978 House .48 .79

(1, 3, 3, 1) 1980 House .49 .90

(1, 4, 3. 1) 1982 House .48 .89

(7) Forsyth

(2, 9, 5, 0) 1978 House .82 .88 .95 .25

(1 Rep B) .82 .90

(1, 10, 5, 0) 1980 House .42 .40 .87 .94

(2, 8, 5, 2)

(5) Wake

1982 House

(1, f>, 13, 1) 1980 House .44 .90

(1, 17, <>, 1) 1982 House .45 .91

(3) E-W-N

(5)

Edgecombe

1982 County

(2, 4, 2) Commissioner .88 .80 .91 .94

Proportion of Proportion of

white voters black voters

for black for black

PRIMARY candidate(s) candidate(s)

.89 .92

(2, 7, 8, 1) 1978 House .10 .10

X

.82 .90

No Primary 1980 House X

(2, 4, 8, 1)' 1982 House .20 .87

(8, 10, 5, 1) 1978 House .28 .08 .17 .70 .29 .58

(1, 8, 2, 0) 1980 Senate .12 .01

(2, 7, 5, 1) 1980 House .40 .18 .80 .30

(2, 11, 5, 2) 1982 House .25 .80 .80 .91

(1, 12, 0, 0) 1978 House .21 .70

(1, 9, 0, 1) 1980 House .81 .81

(1, 15, 0, 1) 1982 House .89 .82

1982 House (1, 7, 4, 0) .04 .00

1982 1st Cong

Primary (1, 8, 2, 1) .02 .84

1982 2nd Cong-

Primary (1, 2, 1, 0) .05 .91

1982 House (1, 7, 4, 0) .02 .08

1982 1st Cong-

Primary (1, 8, 2, 1) .02 .84

1982 2nd Cong

Primary (1, 2, 1, 0) .08 .97

1982 County 0 0 .04 .02

Commissioner (4, 10, 8, 2) .14 .27 .75 .82

Michaux wins in

Edgecombe

Ex-3

TABLE 1 (continued)

GENERAL

(4) Wilson

(5) Nash

Proportion of Proportion of Proportion of Proportion of

white voters black voters white voters black voters

for black for black for black for black

candidate(s) candidate(s) PRIMARY candidate(s) candidate(s)

1982 House (1, 7, 4, 0) .02 .70

1982 1st Cong- .00 .9(5

Primary (1, 3, 2, 0) .07 .98

1982 2nd Cong .82 .77

Primary (1, 2 , 1, 0)

1970 County

Commissioner (1, 1 , 7,0)

1970 House

1982 1st Cong-

(1, 7, 4, 0) .02 .58

Primary (1, 3, 2, 1) .00 .73

1982 2nd Cong-

Primary (1, 2, 1, 0) .00 .81

1982 County

Commissioner (1, <>, 3, 0) .09 .82

:4n Edgecombe, Wilson and Nash there was only black candidate for House or Senate in the period 197X-19H2. Data for those counties are based in addition on a 1970 County Commission race in

Wilson, 1982 Congressional Primaries, and Edgecombe and Nash 19X2 County Commission Primaries and Ceneral Elections.

N - 58

Actual district races - MO House & Senate (P&G)

1 County Commissioner (P&(1)

2 Cong Primaries

M<>

Ex-4

Ranking of White Voter Support for Black Candidates vs. Black Voter Support for Black Candidates in Eight North Carolina Counties,

House and Senate Primary and General Elections in which there was at least one Black Candidate, 1978-1982.*

CONDENSED SUMMARY TABLE 2

Ranking of white Ranking of black Ranking of white Ranking of black

voters for black voters for black voters for black voters for black

GENERAL candidate(s) candidate(s) PRIMARY candidate(s) candidate(s)

(5) Mecklenburg & Cabarrus

(1, <), 4. 1) 1978 Senate 4 1 (i, 5, 4, 1) 1978 Senate last 1

a, 5, 4, 0) 1980 Senate last 1

(1, 7, 4, 0) 1982 Senate (i 1 (i, <», 4, 1) 1982 Senate 5 1

(9) Mecklenburg

(1, (i, 4, 1) 1978 Senate 4 1 (i, 5, 4, 1) 1978 Senate last 1

(i, 5, 4, 0) 1980 Senate last 1

U, Hi, 8, 0) 1980 House last 1 (i. 13, 8, 1) 1980 House 10 1

(1, 7, 4, 0) 1982 Senate 0 1 (i, 0, 4, 1) 1982 Senate 5 1

(2, 18, 8, 1) 1982 House 7 14 1 2 (2, 9, 8, 2) 1982 House 7 last 1 2

(5) Cabarrus

(1, (i, 4, 1) 1978 Senate 5 1 (1, 5, 4, 0) 1978 Senate last 1

(1, 5, 4, 0) 1980 Senate last 1

(1, 7, 4, 0) 1982 Senate 0 1 (1, (i, 4, (1) 1982 Senate 5 1

((>) Durham

(1,4, 2, (!) 1978 Senate last 2,

(Rep B)

(1, 3, 3, 1) 1978 House last 1 (2, 7, 3, 1) 1978 House last <) 2 1

(1. 3, 3, 1) 1980 House last 1 N( Primary 1980 House X X

(1, 4, 3, 1) 1982 House 1 (2, 4, 3, 1) 1982 House next to last last 2 1

(7) Forsyth

(2, !), 5, 0) 1978 House last next to last 1 (j (3, 10, 5, 1) 1978 House 7 last 8 a 2 l

(1 Rep B) (1, 3, 2, 0) 1980 Senate last i

(1, 10, 5, 0) 1980 House last 1 (2, 7, 5, 1) 1980 House next to last last 1 2

(2. 8, 5, 2) 1982 House last next to last 2 1 (2, 11, 5, 2) 1982 House 8 4 1 2

Alexander loses

in 1078 Cabarrus

primary.

Polk loses in

1982 Cabarrus

primary.

Ex-5

(6) Wake

(1, 13, 6, 1)

(1, 17, (i, 1)

(3) E-W-N

(5) Edgecombe

(3, 4, 3, 2)

(4) Wilson

TABLE 2 (continued)

GENERAL

1982 County

Commissioner

Ranking of white Ranking of black Ranking of white

voters for black voters for black voters for black

candidate(s) candidate(s) PRIMARY candidate(s)

0 1 (1, 12, (), 0) 1978 House 9

3 1 (1, 9, 0, 1) 1980 House 8

(1, 15, 6, 1) 1982 House 5

1982 House

1982 1st Cong-

(1, 7, 4, 0) last

Primary

1982 2nd Cong-

(1, 3, 2, 1) last

Primary (1, 2, 1, 0) last

1982 House

1982 1st Cong-

(1, 7, 4, 0) last

Primary

1982 2nd Cong-

(1, 3, 2, 1) last

Primary (1, 2, 1, 1) last

2 3 2 1 1982 County (4, 10, 3, 2) last tied for last

Commissioner

1982 House

1982 1st Cong-

(1, 7, 4, 0) last

Primary

1982 2nd Cong-

(1, 3, 2, 0) last

Primary

1970 County

(1, 2, 1, 0) last

Commissioner (1, 13, 7, 0) 11

Ranking of black

voters for black

candidate(s)

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

4 3 2 1

1

1

1

1

Miehaux wins in

Edgecombe only

Ex-6

(4) Nash

TABLE 2 (continued)

Ranking of white Ranking of black Ranking of white Ranking of black

voters for black voters for black voters for black voters for black

candidate(s) candidate(s) PRIMARY candidate(s) candidate(s)

1976 House (1, 7, 4, 0) 7 1

1982 1st Cong

Primary (1, 3, 2, 1) tied for last 1

1932 2nd Cong

Primary (1, 2, 1, 0) last 1

1982 County

Commissioner U, 6, 3, 0) 6 1

*ln Edgecombe, Wilson and Nash there was only black candidate for House or Senate in the period 11)78-1982. Data for those counties are based in addition on a 197(5 County Commission race in

Wilson, 1982 Congressional Primaries, and Edgecombe and Nash 1982 County Commission Primaries and General Elections.

N = 53

Actual district races - 30 House & Senate (P&G)

•1 County Commissioner (P&G)

_2 Cong Primaries

:«}

Ex-7

Level of White Voter Support for Black Candidates vs. Black Voter Support for Black Candidates in Eight North Carolina Counties,

House and Senate Primary and General Elections in which there was at least one Black Candidate, 1978-1982.*

CONDENSED SUMMARY TABLE 3

Proportion of Proportion of Proportion of Proportion of

the votes cast the votes cast the votes cast the votes cast

by white by black by white by black

voters which voters which voters which voters which

go to the black go to the black go to the black go to the black

candidate(s) candidate(s) candidate(s) candidate(s)

GENERAL PRIMARY

P’wn P'nii f^WB P'm; P'm,

(5) Mecklonbui g & Cabarrus

(1, 6, 4, 1) 1978 Senate .16 .38 (1, 5, 4, 1) 1978 Senate .10 .53

(1, 5, 4, 0) 1980 Senate .09 .52

(1, 7, 4, 0) 1982 Senate .11 .40 (1, 6, 4, 1) 1982 Senate .12 .49

(9) Mecklenburg

a , <i, 4, i) 1978 Senate .15 .38 (1, 5, 4, 1) 1978 Senate .17 .55 Alexander

(1. 5, 4, 0) 1980 Senate .09 .53 loses in 1978

(1, 1(>, 8, 0) 1980 House .05 .23 (1, 13, 8, 1) 1980 House .04 .34 Cabarrus

a , 7,4, i) 1982 Senate .11 .47 (1, 6, 4, 1) 1982 Senate .11 .53 primary.

(2, 18, 8, 1)

(5) Cabarrus

1982 House .12 .48 (2, 9, 8, 2) 1982 House .17 .54

<1, «, 4, 1) 1978 Senate .14 .31 (1, 5, 4, 0) 1978 Senate .15 .37 Polk loses in

(1, 5, 4, 0) 1980 Senate .09 .37 1982 Cabarrus

(1, 7, 4, 0) 1982 Senate .18 .27 (1, 6, 4, 0) 1982 Senate .16 .38 primary

(6) Durham

(1. 4, 2, 0) 1978 Senate .12 .03

(Rep. R)

(1, 3, 3, 1) 1978 House .28 .36 (2, 7, 3, 1) 1978 House .10 .99

U, 3. 3, 1) 1980 House .82 .35 No Primary 1980 House X X

(1, 4, 3, 1) 1982 House .20 .78 (2, 4, 3, 1)' 1982 House .35 .91

(7) Forsyth

(2, !), 5, 0) 1978 House .16 .34 (3, 10, 5, 1) 1978 House .14 .63

(1 Rep B) (1, 3, 2, 0) 1980 Senate .07 .51

(1, 10, 5, (I) 1980 House .07 .24 (2, 7, 5, 1) 1980 House .15 .55

(2, 8, 5, 2) 1982 House .21 .55 (2, 11, 5, 2) 1982 House .15 .55

Ex-8

TABLE 3 (continued)

GENERAL

(5) Wake

(1, 13, 0, 1) 1980 House

(1, 17, (>, 1) 1982 House

(3) E-W-N

(5) Edgecombe

1982 County

(2, 4, 3, 2) Commissioner

(4) Wilson

Proportion of Proportion of Proportion of Proportion of

the votes cast the votes cast the votes cast the votes cast

by white by black by white by black

voters which voters which voters which voters which

go to the black go to the black go to the black go to the black

candidate(s) candidate(s)

PRIMARY

candidate(s) candidate(s)

P'1 Wl! P'.m l"wn P'nu P'.m

.09 .19 (1, 12, 0, 0) 1978 House .05 .40

.09 .18 (1, 9, 0, 1) 1980 House .09 .50

(1, 15, 0, 1) 1982 House .10 .41

1982 House

1982 1st Cong-

(1, 7, 4, 0) .01 .36

Primary

1982 2nd Cong-

0 , 3, 2, 1) .02 .90

Primary (1, 2, 1, 0) .05 .94

1982 House

1982 1st Cong-

(1, 7, 4, 0) .01 .31

Primary

1982 2nd Cong-

(1, 3, 2, 1) .02 .92

Primary (1, 2, 1, 0) .02 .99

1982 County

.40 .08 Commissioner (4, 10, 3, 2) .02 .87

1982 House

1982 1st Cong-

(1, 7, 4, 0) .01 .52

Primary

1982 2nd Cong

(1, 3, 2, 0) .07 .98

Primary (1, 2, 1, 0) .07 .99

1970 County

Commissioner (1, 13, 7,0) .05 .30

Michaux wins

in Edgecombe

only

Ex-9

TABLE 3 (continued)

Proportion of Proportion of Proportion of Proportion of

the votes cast the votes cast the votes cast the votes cast

by white by black by white by black

voters which voters which voters which voters which

go to the black go to the black go to the black go to the black

candidate(s) candidate(s)

PRIMARY

candidate(s) candidate(s)

197(5 House

1982 1st Cong-

(1, 7, 4, 0) .01 :3l

Primary

1982 2nd Cong-

a . a, 2, i) .07 .79

Primary

1982 County

(1, 2, 1, 0) .0(5 .82

Commissioner (1,0, 3, 0) .04 .49

*In Edgecombe, Wilson and Nash there was only black candidate for House or Senate in the period 11)78-11)82. Data for those counties are based in addition on a 197(5 County Commission race in

Wilson, 1982 Congressional Primaries, and Edgecombe and Nash 1982 County Commission Primaries and General Elections.

N - 58

Actual district races - MO House & Senate (P&G)

•1 County Commissioner (P&G)

2 Cong Primaries

Mb

Ex-10

PLAINTIFF’S EXHIBIT 11, APP. 6#4 Gingles

APPENDIX 6 to “Effects Multimember Districts”

Black Legislative Representation in States with Black Population over 15%

Percent

Predominantly single

member districts in areas # of Black

Predominantly single

member districts in areas # of Black

Predominantly single

member districts in areas

population of Black concentration as Reps, in of Black concentration as Reps, in of Black concentration as

Black (1970) of July 1977 July 1977 of July 1982 July 1982 of July 1983

Alabama 26.4 YES 15 YES 16 YES

Arkansas 18.6 NO 4 NO 5 NO

Florida 15.5 NO 3 NO 5 YES

Georgia 25.9 YES 23 YES 22 YES

Louisiana 29.9 YES 10 YES 13 YES

Maryland 17.9 * 19 * 21 **

Mississippi 36.8 NO 4 YES 17 YES

North Carolina 22.4 NO 6 NO 4 YES & NO

South Carolina 30.5 YES 13 YES 15 YES

Tennessee 16.1 YES 11 YES 12 YES

Virginia 18.6 NO 2 NO 5 NO

# of Black

Reps, in

July 1983

20

5

12

24

13

23

17

13

20

13

1977 (omitting Maryland) 1982 (omitting Maryland) 1982 (omitting N.C. & Maryland)

Average # of Black Representatives in States with

Predominantly Single Member Districts in Black Areas 3.8 (TOTAL — 19, N = 5) 4.8 (TOTAL - 19, N 4) (i (TOTAL = 12, N = 2)

Average # of Black Representatives in States with

Predominantly Single Member Districts in Black Areas 14.5 (TOTAL — 72, N — 5) 15.8 (TOTAL - 95, N — 0) 18.4 (TOTAL ~ 129, N — 7)

*:> member districts used throughout, Blacks only elected from majority Black mmds.

**mix of 1, 2, and .'» person districts, Blacks only elected from majority Black mmds and smds, with one exception

Ex-11

Success in General Elections

Wo o f candidates th at Lose by party race)

1910-1982 „„„ 1982

fetlOOtyo

W B W B

Democrats Republicans

100

9 0

s o

TO

60

50

AO

30

20

10

0

2 ^ V - 5 ° T o

O ~ 0 ° l o

2 = 2 8 .5 7 o

1 N /A

W B W B

Democrats Republicans

Exhibits

Ex-12

Participation in General Elections

1% o f candidates o f each p arty by race)

1970-1982

I 5 8 ” % 5 %

B W B

Democrats Republicans

1982

2 b H < ? 0 %

W B W B

Democrats Republicans

E X H I B I T 1 9

Gingles

Ex-13

Ex-14

PLAINTIFF’S EXHIBIT 20 GINGLES

The Disadvantageous Effects of At-Large Elections

On the Success of Minority Candidates

For the Charlotte and Raleigh City Councils

Bernard Grofman

Professor of Political Science

School of Social Sciences

University of California, Irvine

Irvine, California

May 20, 1983

I. Campaign Expenditures in the District-Based

and At-Large Component of the Charlotte City Council and

Raleigh City Council Elections in 1979 and 1981

We would like to test the hypothesis that at-large elec

tions are more expensive to run than district-based cam

paigns. Intuitively it would seem very reasonable that at-

large elections, involving as they do larger constituen

cies, would be more costly.1 However, there are a number

of methodological problems in empirically validating what

might appear commonsensically obvious; even though the

few available studies (e.g., Grofman 1982; Jewell 1982) all

support the truth of the proposed hypothesis:

(1) There are differences in spending patterns between

incumbents and non-incumbents. Moreover, those differ

ences are complicated by the considerable incumbency

advantage in raising money versus the countervailing

lesser need of highly visible incumbents to spend money

to win elections. Also the magnitude of the incumbency

1 Campaign funds are often spent somewhat differently in at-large

than in district elections; for the latter, use of city-wide media (e.g.,

radio, TV, city newspapers) is less efficient than for the former and

this may reduce somewhat the cost advantages produced by the

smaller scope of district-based campaigns.

Ex-15

advantage is often different in at-large than in single

member district elections.

(2) Both at-large and district races contain candidates

who run with little chance of victory (and with minimal

campaign expenses), but the number of such candidates is

generally greater in at-large elections.

(3) Many candidates largely finance city council cam

paigns through their own funds, and such personal re

sources vary widely, introducing idiosyncratic features

which are hard to control for because of the small number

of mixed system elections for which we have campaign

funding data available for analysis.

Nonetheless, each of these methodological problems

associated with analyzing comparative campaign expen

ditures across different types of election systems may be

solved (or at least mitigated) if (1) we distinguish between

incumbent and non-incumbent expenditures (2) for both

incumbents and non-incumbents we focus on the expendi

tures of the winning candidates, and (3), we combine data

so as to obtain a larger sample size and more reliable data

estimates. We shall look at Charlotte City Council and

Raleigh City Council campaign expenditures patterns,

combining 1979 and 1981 data.

In Charlotte there were four at-large seats and seven

district seats in both the 1979 and 1981 elections (see

Appendices 1 and 2). Combining data for the two elections

we find winners at large averaged over $12,000 on cam

paign expenditures (whether they were incumbent or

non-incumbent); while in the district based elections, win

ning challengers spent ony $5,815 and winning incum

bents spent only $3,198 (see Table 1). Thus, campaign

costs in Charlotte City Council at-large elections were, on

average, more than twice those for district elections in

that city.

Ex-16

In Raleigh, for both the 1979 and the 1981 election,

there were two at-large seats and five district seats (see

Appendices 3 and 4). Combining data for the two elections

we find incumbent winners at-large spent an average of

$9,105 while incumbent district winners spent an average

of only $5,344; non-incumbent at-large winners spent an

average $11,925 while non-incumbent district winners

spent on average only $5,213. Thus, at-large campaign

costs in Raleigh at-large city council elections were, on

average, roughly twice those for district elections in that

city.

II. Success of Black Candidates in the District-Based

and At-Large Component of Charlotte City Council

and Raleigh City Council Elections

The considerably higher expenditures required to run a

successful at-large race in Charlotte imposes a burden on

minority groups (such as blacks) who are economically

disadvantaged. This financial burden, combined with ra

cial bloc voting which makes for a greater difficulty of

black success in at-large race with a primarily white elec

torate as compared to a district race with a primarily

Black electorate (e.g., Charlotte Districts 2-3), has meant

that Blacks are disproportionately excluded from the at-

large council seats in Charlotte. In the period 1977-1981,

of the 21 district seats contested, Blacks won 6 (28.6%);

while of the 12 at-large seats contested Blacks won only 2

(16.7%), despite the fact that there were more Black

candidates for the four at-large seats than for the seven

district seats. In the preceding period, 1945-1975, under

a pure at-large system, Black representation was even

less, averaging only 5.4% (Heilig and Mundt 1981; see also

Heilig, 1978; Mundt 1979).

As in Charlotte, Black electoral success in Raleigh was

considerably greater in the district than in the at-large

component of the city council elections in 1977-1981. Of

Ex-17

the 15 district seats contested, Blacks won three (20.0%),

while of the six at-large seats contested, Blacks won no

seats (0.0%), despite the fact that there were propor

tionally about as many Black candidates contesting the at-

large elections as contesting the district elections. This

finding of greater minority success in a district-based

system (or the district-based component of a mixed sys

tem) than under an at-large or multi-member district

system has been repeated in a large number of munici

palities and other jurisdictions where there exists a sub

stantial minority population and patterns of polarized

voting (see esp. Engstrom and McDonald 1981; Karnig

and Welch 1978,1979; Grofman 1981; and overviews of the

literature in Engstrom and McDonald 1984 forthcoming

and in Grofman 1982b).

“Indeed, few generalizations in political science ap

pear to be as well verified as the proposition that at-

arge elections tend to be discriminatory toward

black Americans” (Engstrom and McDonald, 1984

forthcoming).

III. Summary

We examined the campaign expenditure patterns for

the at-large and district components of Charlotte and

Raleigh, North Carolina city council elections and found

that successful at-large election campaigns are more ex

pensive to run than successful district compaigns. We

then looked at the success of black candidates in recent

Charlotte and Raleigh city council races and found dra

matically greater success for black candidates running in

the district-based elections than for those running for the

city-wide seats. In reducing their likelihood of obtaining

office if they do seek it, and/or in increasing the amount of

money which must be spent to achieve office, at-large

elections in Charlotte and Raleigh had a discriminatory

effect on Black candidates, when compared with district

elections in the same cities.

Tahiti'

Campaign Expenses: Charlotte City Council, 1979-1981

Winning Incumbents2

dartre District

$12,194 (N = 12) ,198 (N = 9)

Winning Non-Incumbents

At-large District

1979

expenditures

average (N = 2)

$5,700

4,945

$5,326

$ 554

1,084

1,907

2,699

5,784

2,914

5,075

$3,031

(N = 2)

(N = 5)

$18,142

19,100

$18,021

None

Winning Incumbents Winning Non-Incumbents

At-large District At-large District

$3,119 $7,014 $8,717

1,936 5,292 2,913

1981 2,777 average $0,153 (N = 2) $5,815

expenditures $18,452 4,531 (N = 2)

19,009 4,800

average (N = 2) $19,001 (N = 5) $3,433 (N = 5)

Winning Incumbents Winning Non-Incumbents

At-large District At-large District

1979 and average

1981 (N = 1)

combined

* There were not enough winning blank candidates to make it feasible to separately tabulate by race of candidate. The raw data on which this

research note.

-In liffil and l'lfil all incumbents running for reelection to the Charlotte City Counity won reflection. In 1SI7!) » of 11 incumbents sought

$12,287 (N = 2) $5,815

table was based Is provided as appendices to this

reflection; in 1981, 7 of 11 did.

Ex-18

Tablet2

Campaign Expenses: Raleigh City Council, 1979-1981

Winning Incumbents Winning Non-Incumbents

1979

expenditures

average (N = l)

At-large District At-large District

$3,598

$3,598

$15,723

4,187

257

5,048

$ 6,304

$10,016

$10,016

ItOOl OO

€/3-

Winning Incumbents Winning Non-Incumbents

At-large District At-large District

1981 $5,310

expenditures $14,611 1,301 $13,834 $1,463

average ( N=l ) $14,611 (N = 4) $4,383 (N = 1) $13,834 (N = 1) $1,463

Winning Incumbents Winning Non-Incumbents

At-large District At-large District

1979 and

1981 average $9,105 (N = 8) $5,344 (N = 2) $11,925 <N = 2) $5,213

combined (N 2)

•There were not enough winning black candidates to make it feasible to separately tabulate by race of candidate. The raw data on which this table was based is provided as appendices to this

research note.

Ex-19

Ex-20

N.

J

W 1 I 1 T 1 P E O P L E

WAKEUP

&EFO«E I T 'J T O O LATE

YOUM AYNOT MZVS ANOTM m CMANCB

DO YOU WANT?

PLAINTIFF'S

EXHIBIT

25

G i r d l e s

Negroes working beside you, your wife ond daughters in your

mills and factories?

Negroes eating beside you in alT public eotmg places?

Negroes riding beside you, yoiir wife and your daughters in

buses, cabs and trains?

Negroes sleeping in the same hctels pry) rooming houses?

Negroes teaching and disciplining your children in school?

Negroes sitting with you and your family at all public meetings?

Negroes Going to white schools and white children oping to Negro

schools? *

Negroes to occups the some hospital rooms with you and vour

wde and daughters? i

Negroes as sour foremen and overseers in the mills?

Negroes using vour toilet facilities?

Northern political labor leaders here recently ordered thet

ell doors be opened to Negroet on union property. This will

lead to whites ond Negroes working ond tiring together in

the South es they do in the North, Do you want that?

FRANK GRAHAM FAVORS MINGLING OF THE RACES

HI ADMITS THAT HI FAVORS MIXING NIGROIS AND WHITIS — HI SAYS SO IN

TH I RtPORT HI SIGNID. (Far Proof of This, Used Page 167, Ciril Rights Report.)

DO YOU FAVOR THIS — WANT SOME MORE OF IT?

IF YOU DO, VOTE FOR FRANK GRAHAM

■ U T IF Y O U D O N ' T

V O T E FOR AND HELP E L E C T

w m i s m r m i©? s e b m h o b

HE WILL UPHOLD THE TRADITIONS OF THE SOUTH

KNOW THE TRUTH COMMITTEE

Ex-21

300

Number

o f Black

Elected

Officials

Years (1970- 1981)

Number o f Black Elected Officials

in North Carolina (1970 "L98D

G ingles

Ex-22 Exhibit,41

Ex-23

PLAINTIFF’S EXHIBIT

52

Gingles

For Congress

Dear Fellow Democrat:

Tuesday, July 27th is a very important day for Democrats in

Durham County. It is a day when you have a chance and

obligation to influence the direction in which our national

government w ill move during the critical years ahead.

That choice is whether you want to be represented in Congress by

a big-government, free-spending liberal, or whether you want to

be represented by a person whose thinking is much more in tune

with the majority of our people.

I think the choice is very clear.

My opponent's liberal record is well-known.

While serving in the state legislature, among other things, he

sponsored a bill which would have raised your personal income

taxes by as much as 40 percent.

He also sponsored a bill which could have forced you to pay

dues to a labor union whether you wanted to or not.

I am opposed to hjs kind of liberal thinking and I believe the

majority of the people in our district are too.

Ex-24

I want you to know that I am opposed to higher taxes, i plan to

introduce a constitutional amendment which would require a

balanced federal budget, which would force the government to

live within its means.

That would cause interest rates to come down which would revive

agriculture, help industry grow and create more jobs for our

people, thereby bringing down unemployment.

I have also made a commitment to open a fully-staffed

Congressional Office in Durham, so that you w ill never be more

than a local phone call away from help with your problems with

the Federal Government.

I know it's July and it's hot. Many folks are on vacation. Many are

busy with tobacco. It's easy not to stop and take the time to vote,

but you must.

Our polls indicate that the same well organized block vote which

was so obvious and influential on the 1 st Primary w ill turn out

again on July 27. My opponent w ill again be bussing his

supporters to the polling places in record numbers.

If you and your friends don't vote on July 27 my opponent's block

vote w ill decide the election for you.

A Congressm an We Can Be Proud Of

Paid for by the Tim Valentine for Congress Committee.

C.T. Lane, Treasurer, P.O. Box 353, Rocky Mount, N.C. 27801

A copy of our report is filed with the Clerk of the House and is

available for purchase from The Federal Election Commission,

Washington, D.C. 20515

Ex-25

Your vote w ill make the difference.

Please join me in voting on Tuesday, July 27. I promise to be a

Congressman of whom you can be proud.

Sincerely,

Tim

Valentine

P.S. CALL TO ACTION

Please take the time to become personally involved in my

campaign by listing below the names of five friends and

neighbors, along with their telephone numbers, and call them on

Tuesday, July 27 to make sure that each one votes.

NAME TELEPHO N E #

Valentine

For Congress

Ex-26

For Congress

Durham Headquarters

202 Corcoran Street

Durham, N.C. 27701

July 21, 1982

Dear Registered Voter,

We ask that you consider the voting pattern and

results of the June 29 primary. There were many many

precincts in Durham that voted over 60% of their

registration, while our precinct only voted around 45%.

If you object to this domination-—if you are

resentful of having others elect your officials—then you

should vote on July 27.

Join us in proving to ourselves that Tim Valentine

can carry Club Boulevard precinct.

Regards,

Jim Dickson

Ex-27

From the Durham Morning Herald

June 50, 1982

Precinct Valentine Michaux Ramsey

Club Blvd. 264 209 282

Burton 9 1260 14

Hillside 1 883 9

Whitted 1 419 5

Shepard 2 744 9

Hillandale 302 192 313

A Strong Voice Fo r Our D istric t

Paid for by the Tim Valentine for Congress Committee.

C.T. Lane, Treasurer, P.O. Box 353, Rocky Mount, N.C. 27801

A copy of our report is filed with the Clerk of the House and is

available for purchase from The Federal Election Commission,

Washington, D.C. 20515

Ex-28

DEFENDANT’S EXH IBIT 1

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

Suite 801 R a l e ig h B u ild in g

5 W est H a r g e t t St r e e t

R a l e ig h , North Ca r o l in a 27601

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Chairman

Members

MRS. ELLOREE M. ERWIN

Charlotte

WILLIAM A. MARSH, JR.

Durham

MRS. RUTH TURNER SEMASHKO

Horse Shoe

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Raleigh

JOHN A. WALKER

North Wilkeshoro

November 30, 1981

SPECIAL MEMORANDUM

SUBJECT: Increased Voter Registration

FROM: Robert W. Spearman, Chairman

Alex K. Brock, Director

TO: All County Board Members and Supervisors

At its meeting on November 9, 1981, the State

Board of Elections adopted and endorsed the goal of

increased voter registration in North Carolina as a top Board

priority.

The Board has directed us to communicate with

each of you about its interest and concern in this important

area.

A successful effort to increase voter registration

will require pooling the efforts, talents, energy and ideas of

Ex-29

local board members, supervisors, elected officials, state

board members and staff with the political parties, civic

groups and all interested citizens.

We would request that at your next local board

meeting you consider what specific steps can be taken in

your county and statewide to make it easier and more

convenient for citizens to register to vote. We also request

you provide our board with the voting age population in your

county, based on the most recent U.S. census.

We would very much appreciate any guidance

and suggestions you can give us as to steps the state board

and its staff can take to increase registration, whether those

be by adopting or altering regulations, recommending

legislation to the General Assembly, sponsoring registration

drives or other techniques.

We are aware that certain voter registration

techniques work better in some areas than in others. Among

the approaches that you may wish to consider using in your

county are:

1. Running public service spots on TV or radio

telling citizens the specific times and places thay can

register.

2. Encourage local political parties to work with

precinct judges, registrars and special registration commis

sioners to have special voter registration days at community

centers, schools and shopping centers.

3. Request local county (and municipal) officials

to include information about how and where one can register

in mailings that are routinely sent out from county or city

offices (e.g., with tax listing notices, water and sewer bills,

etc.).

4. In counties where such a system is not

already in place, work with local library officials and library

trustees to have public library employees designated as

Ex-30

special library registration deputies. (This is already autho

rized by G.S. 163-80 (6 ).)

5. Use supervisors, deputy supervisors of elec

tions and local election board members as registrars for

special registration efforts in schools, community centers,

nursing homes, etc. (This is already authorized by G.S.

163-35 and 163-80.)

We very much look forward to working with you

on voter registration and we would certainly appreciate any

suggestions you can pass along to us.

DUPLICATE THIS FOR ALL BOARD MEMBERS

Ex-31

DEFENDANT’S EXHIBIT 2

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

Suite 801 R a l e ig h B u ildin g

5 W est H a r g e t t St r e e t

R a l e ig h , North Caro lin a 27601

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Chairman

Members

MRS. ELLOREE M. ERWIN

Charlotte

w il l ia m a . m a r s h . JR.

Durham

MRS. RUTH TURNER SEMASHKO

Horse Shoe

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Raleigh

JOHN A. WALKER

North Wilkesboro

December 14, 1981

TO: WORTH CAROLIWA COUWTY ELECTIONS BOARDS AND

SUPERVISORS

Recently questions have been raised, concerning com

pensation of registrars, judges and special registration

commissioners in voter registration efforts. Often the

questions have come up when a civic or community group

desires to have a qualified person eligible to register voters

present at a rally, picnic, dinner or some other community

occasion. In such situations, the following principles should

be followed.

1. Under State law any registrar, judge of election or

special registration commissioner can register voters any

where in the county without regard to the precinct of the

applicant unless the local board has restricted the authority

of the registrar, judge or special commissioner. G.S. 173-67.

The State Board strongly encourages the use of

registrars, judges and special registration commissioners for

Ex-32

special registration efforts and suggests that any local board

rules restricting their authority be reexamined.

2. There is no state law requirement that registrars,

judges or special registration commissioners be compensated

for registering voters. Frequently registrars and judges

register voters (as opposed to performing their election day

duties) on a volunteer basis without pay. (However, some

county boards do pay for special registration work performed

at public libraries or other places, and it is perfectly proper

to do so.)

3. Private groups may not compensate registrars,

election judges, or special registration commissioners. G.S.

163-275.

4. If a private group (e.g. civic club, community

association, etc.) is willing to or desires to reimburse a

county for the cost of paying registrars for special registra

tion efforts it may properly do so. The proper procedure to

follow is for the group to make a contribution to the board of

county commissioners for the purpose of special voter

registration and the commissioners could then appropriate

the funds to the local Board of Elections for such purpose.

Robert W. Spearman

Chairman, State Board of

Elections

Alex K. Brock

Executive Secretary-Director,

State Board of Elections

Senior Deputy Attorney General

DUPLICATE FOR ALL BOARD MEMBERS

Ex-33

DEFENDANT’S EXHIBIT 3

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

Suite 801 R a l e ig h B u ildin g

5 W est Ha r g e t t St r e e t

Raleigh, North C a ro lin a 27601

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Chairman

Members

MRS. ELLOREE M. ERWIN

Charlotte

WILLIAM A. MARSH, JR.

Durham

MRS. RUTH TURNER SEMASHKO

Horse Shoe

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Rale i oh

JOHN A. WALKER

North Wilkesboro

January 29, 1982

TO: COUNTY BOARD MEMBERS ANT) SUPERVISORS

FROM: BOB SPEAR MATT, CHAIRMAN

ALEX BROCK, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

SUBJECT: CITIZEN AWARENESS YEAR AND VOTER

REGISTRATION

At the request of the State Board of Elections,

Governor James Hunt has designated 1982 as a Citizen

Awareness Year in which a maximum effort will be made to

increase North Carolina voter registration.

The State Board will sponsor two major voter

registration drives, from April 15, 1982 to July 5, 1982

before the primary and from September 1 to October 4

(when registration closes for the general election.)

The voter registration drive is officially spon

sored and is nonpartisan. All political parties and civic

groups are invited and encouraged to participate.

Ex-34

Obviously, the success of this effort will depend

very much upon you because you are the public officials most

familiar with the election process and closest to its day-to-

day operation.

There will be two main thrusts to the voter

registration drive: (1 ) Maximum publicity of existing voter

registration opportunities and (2 ) Provision of special

registration opportunities to maximize participation.

The State Board intends to take all possible steps

to maximize statewide publicity, including holding press

conferences and providing public service spots to radio and

television stations. We request that your local board take

similar steps in your county or municipality. Specifically, you

may wish to consider the following:

Check with local T.V. and radio stations to

determine if they will produce and broadcast public service

spots telling county citizens when and where they can

register to vote. (The spot announcements can be made by

different board members.)

Issue press releases on Citizen Awareness Year

in your area and registration opportunities.

Post signs or notices with registration informa

tion in public places (e.g. county offices, stores, community

bulletin boards.)

Check with county and municipal officials to see

if they would agree to have basic voter registration informa

tion included with routine official mailings (e.g. with tax

notices or municipal water bills.)

Special Registration Opportunities.

In addition to publicizing existing registration

opportunities, we need to take extra steps to reach groups

whose registration has historically been low. Situations vary

in different areas of the State, but frequently groups with low

registration include elderly citizens, young people, and

Ex-35

minority groups. We request you consider using the following

outreach techniques during Citizen Awareness Year, particu

larly from April 15, 1982 to July 5, 1982 and September 1 to

October 4, 1982.

1. Staff registration tables in evening hours at

places where large groups of people congregate (shopping

centers are often excellent.)

2. Have a “registration day” in the spring and

again in the fall in local public high schools and community

colleges; on these days send registrars and commissioners to

register students and faculty at their educational institutions.

3. Send registrars or commissioners for special

registration events to residential areas where registration is

low. These may include nursing homes, public housing or

mobile home parks.

4. Upon request; supply registrars or commis

sioners for special events being run by community groups,

such as banquets, dinners, picnics, athletic contests, church

suppers, etc. (Very frequently, this can be done without any

cost to the board because registrars or commissioners will

donate their time and not expect to be paid.)

We expect that local boards will receive requests

from political parties and community groups for assistance

in special registration efforts during Citizens Awareness

Year.

When you receive such requests, try to be as

helpful as you can in answering questions, supplying voter

registration information and where necessary, helping to

find registrars, judges, and special registration commis

sioners who can assist in registering voters at special

events.

Paid Pol. Adv.

W H A T NORTH CAROLINA NEWSPAPERS

SAY A B O U T VOTER REGISTRATION

GOV. H U N s, REV . JACKSON M E E T — Governor Jim Hunt and the Rev.

Jesse Jackson met in the Executive Mansion March 11 to discuss a number of

mutual concerns, including voter registration . . .

T h e C a r o l in i a n , 3 - 1 8 - 8 2

“ He (Jesse Jackson) said Gov. Jim Hunt, an expected

Senate candidate in 1984, had fa limited future— unless

we register/ * *

Greensboro Daily N e w s . 5 - 76-83

"W e must register at least 200,000 black voters in North

Carolina in the next two months." (Jesse Jackson)

News a n d O b s e r v e r , 4 -2 2 -3 3

"Gov. James B. Hunt, Jr. wants the State Board of

Elections to boost minority voter registration in

North Cuiolina . . . L PI Chapel Hill Newspaper, 11-10-81

Ask Yourself:

Is This A Proper Use Of Taxpayer Funds?

fW 6r Sw*#* v -— ••••

Ex-36

Ex-37

GINGLES EXHIBIT #56

Mecklenburg County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 291,442 107,006 404,270

Percent of Population 72.1 26.5

Percent of Population Below

Poverty 5.5 25.7 10.9

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000 61.7 27.9 53.6

Mean Income 27,209 15,519 24,462

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income 57.0%

Total Number of Housing

Units 111,223 34,209

Number of Renter Occupied 36,949 2,056

Percent Renter Occupied 33.2 60.1

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available 5.0 26.5 10.0

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 9.9 25.0

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980) 24.0

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980) 16.9

Ex-38

GINGLES EXHIBIT #57

Forsyth County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 182,647 59,403 243,683

Percent of Population 75.0 24.4

Percent of Population Below

Poverty

Percent of Family Income

6.9 25.6 11.6

over $20,000 56.2 28.6 50.2

Mean Income

Ratio Black to White Mean

25,355 15,101 23,188

Income 59.56%

Total Number of Housing

Units 69,699 19,885

Number of Renter Occupied 19,320 11,934

Percent Renter Occupied

Percent Units with No Vehi-

27.7 60.0

cle Available 5.9 27.4 10.7

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 16.7 26.6

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980) 22.0

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980) 20.3

Ex-39

GINGLES EXHIBIT #58

Durham County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 95,818 55,424 152,785

Percent of Population 62.7 36.3

Percent of Population Below

Poverty 7.6 24.9 14.0

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000 57.8 28.5 47.9

Mean Income 24,984 15,357 21,719

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income -61.47%

Total Number of Housing

Units 36,792 18,343

Number of Renter Occupied 13,953 11,462

Percent Renter Occupied 37.9 62.5

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available 6.9 25.2 13.0

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 14.6 26.6

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980) 33.6

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980) 24.9

Ex-40

GINGLES EXHIBIT #59

Wake County—Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 231,561 65,553 301,327

Percent of Population 76.8 21.8

Percent of Population Below

Poverty 6.2 23.4 10.0

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000 63.7 28.7 56.8

Mean Income 26,893 15,347 24,646

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income 57.07%

Total Number of Housing

Units 85,664 19,793

Number of Renter Occupied 29,609 11,021

Percent Renter Occupied 34.6 55.7

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available 4.5 21.0 7.6

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 9.3 28.2

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980)

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980)

Ex-41

GINGLES EXHIBIT #60

Wilson County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 39,943 22,981 63,132

Percent of Population 63.3 36.4

Percent of Population Below

Poverty 9.6 37.8 20.0

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000 45.5 17.1 36.5

Mean Income 21,687 12,241 18,732

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income 56.44% 14.0

Total Number of Housing

Units 14,725 6,781

Number of Renter Occupied 4,818 4,368

Percent Renter Occupied 32.7 64.4

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available 7.1 29.1 14.0

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 23.0 44.2

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980) 32.4

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980) 23.0

Ex-42

GINGLES EXHIBIT #61

Edgecombe County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 27,428 28,433 55,988

Percent of Population 49.0 50.8

Percent of Population Below

Poverty 9.6 30.5 20.2

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000 44.2 20.2 33.3

Mean Income 20,476 13,592 17,360

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income -66.38%

Total Number of Housing

Units 10,246 8,117

Number of Renter Occupied 2,782 4,258

Percent Renter Occupied 27.2 52.5

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available 7.7 26.2 16.0

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 23.8 40.3

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980) 46.7

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980) 34.6

Ex-43

GINGLES EXHIBIT #62

Nash County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 44,745 22,089 67,153

Percent of Population 66.6 32.9

Percent of Population Below

Poverty 8.9 41.8 19.9

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000 46.7 13.9 37.5

Mean Income 21,785 11,434 18,937

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income 52.49%

Total Number of Housing

Unifs 16,982 6,391

Number of Renter Occupied 4,933 3,763

Percent Renter Occupied 29.0 58.9

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available 6.7 27.2 12.3

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980) 29.4

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980) 13.2

Ex-44

GINGLES EXHIBIT #63

Halifax County— Demographic Data

Population

Percent of Population

Percent of Population Below

Poverty

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000

Mean Income

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income

Total Number of Housing

Units

Number of Renter Occupied

Percent Renter Occupied

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980)

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980)

White

27,559

49.8

Black

26,053

47.1

Total

55,286

12.6 47.8

37.9

19,042

12.9

10,465

27.1

15,479

-54.96%

10,680

2,800

26.2

7,201

3,520

48.9

10.2 32.3 19.0

25.6 51.5

44.0

35.2

Ex-45

GINGLES EXHIBIT #64

Northampton County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 8,824 13,709 22,584

Percent of Population 39.1 60.7

Percent of Population Below

Poverty 11.6 38.2 28.1

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000 34.9 15.3 24.0

Mean Income 19,964 12,942 16,080

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income 64.83%

Total Number of Housing

Units 3,248 3,849

Number of Renter Occupied 549 1,261

Percent Renter Occupied 16.9 32.8

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available 10.5 27.9 19.9

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 23.1 54.6

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980) 56.2

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980) 51.4

Ex-46

GINGLES EXHIBIT #65

Hertford County— Demographic Data

Population

Percent of Population

Percent of Population Below

Poverty

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000

Mean Income

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income

Total Number of Housing

Units

Number of Renter Occupied

Percent Renter Occupied

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980)

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980)

White

10,285

44.0

Black

12,810

54.8

Total

23,368

10.4 34.7 24.3

41.8

20,465

20.5

13,194

31.2

16,946

64.47%

3,727

950

25.5

3,709

1,452

39.1

10.0 28.1 19.2

21.9 48.1

56.2

51.4

Ex-47

GINGLES EXHIBIT #66

Gates County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 4,192 4,664 8,875

Percent of Population 47.2 52.6

Percent of Population Below

Poverty 7.9 30.5 19.7

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000 43.4 22.1 33.4

Mean Income 21,025 13,204 17,380

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income -62.8%

Total Number of Housing

Units 1,605 1,274

Number of Renter Occupied 265 343

Percent Renter Occupied 16.5 26.9

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available 7.2 21.9 13.7

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 21.3 43.4

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980) -49 .4

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980) 47.8

Ex-48

GINGLES EXHIBIT #67

Martin County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 14,334 11,555 25,948

Percent of Population 55.2 44.5

Percent of Population Below

Poverty

Percent of Family Income

10.8 40.3 24.1

over $20,000 * * *

Mean Income

Ratio Black to White Mean

* * *

Income -ijc

Total Number of Housing

Units *

Number of Renter Occupied

Percent Renter Occupied

Percent Units with No Vehi-

*

>fc

cle Available *

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 25.2 47.9

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980)

Percent Voters that is Black 40.6

(1980) 33.1

*not available

Ex-49

GINGLES EXHIBIT #68

Bertie County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 8,488 12,441 21,024

Percent of Population 40.6 59.2

Percent of Population Below

Poverty 13.2 40.7 29.4

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000 32.0 12.8 22.0

Mean Income 17,649 12,502 15,008

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income 70.8%

Total Number of Housing

Unite 3,346 3,533

Number of Renter Occupied 678 1,293

Percent Renter Occupied 20.3 36.6

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available 8.8 24.2 16.6

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 28.8 45.1

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980) 54.5

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980) 44.2

Ex-50

GINGLES EXHIBIT #69

Washington County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 8,346 6,410 14,801

Percent of Population 56.4 43.3

Percent of Population Below

Poverty 10.9 35.9 21.7

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000 48.5 22.4 38.9

Mean Income 20,868 13,019 17,998

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income 62.39%

Total Number of Housing

Units 3,052 1,670

Number of Renter Occupied 596 624

Percent Renter Occupied 19.5 37.4

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available 7.6 30.1 15.6

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 22.2 43.9

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980) 39.1

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980) 34.0

Ex-51

GINGLES EXHIBIT #70

Chowan County— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 7,294 5,210 12,558

Percent of Population 58.1 41.5

Percent of Population Below

Poverty 8.8 45.4 24.0

Percent of Family Income

over $20,000 41.5 9.5 29.1

Mean Income 20,622 10,704 16,877

Ratio Black to White Mean

Income 51%

Total Number of Housing

Units 2,765 1,559

Number of Renter Occupied 587 738

Percent Renter Occupied 21.2 47.3

Percent Units with No Vehi

cle Available 7.5 30.3 15.8

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Education

or Less 23.2 48.9

Percent Voting Age Popula

tion that is Black (1980) 38.1

Percent Voters that is Black

(1980) 31.2

Ex-52

GINGLES EXHIBIT #70A

North Carolina— Demographic Data

White Black Total

Population 4,460,570 1,319,054 5,881,766

Percent of Population 75.8 22.4

Percent of Population

Below Poverty 10.0 30.4 14.8

Percent of Family In

come over $20,000 43.8 21.5 39.2

Mean Income 21,008 13,648 19,544

Ratio Black to White

Mean Income 64.9%

Total Number of

Housing Units 1,624,372 391,379

Number of Renter

Occupied 442,060 191,925

Percent Renter

Occupied 27.2 49.03

Percent Units with No

Vehicle Available 7.3 25.1 10.8

Percent Over 25 with

Eighth Grade Educa

tion or Less 22.0 34.6

Percent Voting

Ex-53

DEFENDANT’S EXHIBIT 1

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

Suite 801 R a l e ig h B uilding

5 W est H a r g e t t St r e e t

R a l e ig h , North Ca ro lin a 27601

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Chairman

Mkmhers

MRS. ELLOREE M. ERWIN

Charlotte

william A. MARSH, JR.

Durham

MRS. RUTH TURNER SEMASHKO

Horsk Shoe

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Raleigh

JOHN A. WALKER

North Wilkekhoro

November 30, 1981

SPECIAL MEMORANDUM

SUBJECT: Increased Voter Registration

FROM: Robert W. Spearman, Chairman

Alex K. Brock, Director

TO: All County Board Members and Supervisors

At its meeting on November 9, 1981, the State

Board of Elections adopted and endorsed the goal of

increased voter registration in North Carolina as a top Board

priority.

The Board has directed us to communicate with

each of you about its interest and concern in this important

area.

A successful effort to increase voter registration

will require pooling the efforts, talents, energy and ideas of

Ex-54

local board members, supervisors, elected officials, state

board members and staff with the political parties, civic

groups and all interested citizens.

We would request that at your next local board

meeting you consider what specific steps can be taken in

your county and statewide to make it easier and more

convenient for citizens to register to vote. We also request

you provide our board with the voting age population in your

county, based on the most recent U.S. census.

We would very much appreciate any guidance

and suggestions you can give us as to steps the state board

and its staff can take to increase registration, whether those

be by adopting or altering regulations, recommending

legislation to the General Assembly, sponsoring registration

drives or other techniques.

We are aware that certain voter registration

techniques work better in some areas than in others. Among

the approaches that you may wish to consider using in your

county are:

1. Running public service spots on TV or radio

telling citizens the specific times and places thay can

register.

2. Encourage local political parties to work with

precinct judges, registrars and special registration commis

sioners to have special voter registration days at community

centers, schools and shopping centers.

3. Request local county (and municipal) officials

to include information about how and where one can register

in mailings that are routinely sent out from county or city

offices (e.g., with tax listing notices, water and sewer bills,

etc.).

4. In counties where such a system is not

already in place, work with local library officials and library

trustees to have public library employees designated as

Ex-55

special library registration deputies. (This is already autho

rized by G.S. 163-80 (6 ).)

5. Use supervisors, deputy supervisors of elec

tions and local election board members as registrars for

special registration efforts in schools, community centers,

nursing homes, etc. (This is already authorized by G.S.

163-35 and 163-80.)

We very much look forward to working with you

on voter registration and we would certainly appreciate any

suggestions you can pass along to us.

DUPLICATE THIS FOR ALL BOARD MEMBERS

Ex-56

DEFENDANT’S EXHIBIT 2

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

Suite 801 R a l e ig h B u ildin g

5 W est H a r g e t t St r e e t

R a l e ig h , North C aro lin a 27601

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Chairman

Memhers

MRS. ELLOREE M. ERWIN

Charlotte

WILLIAM A. MARSH, JR.

Durham

MRS. RUTH TURNER SEMASHKO

Horse Shoe

ROBERT W.. SPEARMAN

Raleigh

JOHN A. WALKER

North Wilkeshoro

December 14, 1981

TO: NORTH CAROLINA COUNTY ELECTIONS BOARDS AND

SUPERVISORS

Recently questions have been raised concerning com

pensation of registrars, judges and special registration

commissioners in voter registration efforts. Often the

questions have come up when a civic or community group

desires to have a qualified person eligible to register voters

present at a rally, picnic, dinner or some other community

occasion. In such situations, the following principles should

be followed.

1. Under State law any registrar, judge of election or

special registration commissioner can register voters any

where in the county without regard to the precinct of the

applicant unless the local board has restricted the authority

of the registrar, judge or special commissioner. G.S. 173-67.

The State Board strongly encourages the use of

registrars, judges and special registration commissioners for

Ex-57

special registration efforts and suggests that any local hoard

rules restricting their authority he reexamined.

2. There is no state law requirement that registrars,

judges or special registration commissioners he compensated

for registering voters. Frequently registrars and judges

register voters (as opposed to performing their election day

duties) on a volunteer basis without pay. (However, some

county hoards do pay for special registration work performed

at public libraries or other places, and it is perfectly proper

to do so.)

3. Private groups may not compensate registrars,

election judges, or special registration commissioners. G.S.

163-275.

4. If a private group (e.g. civic club, community

association, etc.) is willing to or desires to reimburse a

county for the cost of paying registrars for special registra

tion efforts it may properly do so. The proper procedure to

follow is for the group to make a contribution to the board of

county commissioners for the purpose of special voter

registration and the commissioners could then appropriate

the funds to the local Board of Elections for such purpose.

Robert W. Spearman

Chairman, State Board of

Elections

Alex K. Brock

Executive Secretary-Director,

State Board of Elections

Senior Deputy Attorney General

DUPLICATE FOR ALL BOARD MEMBERS

Ex-58

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

Suite 801 R a l e ig h B u ildin g

5 W est H a r g e t t St r e e t

R a l e ig h , North Ca ro lin a 27601

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Chairman

Members

MRS. ELLOREE M. ERWIN

Charlotte

WILLIAM A. MARSH, JR.

Durham

MRS. RUTH TURNER SEMASHKO

Horse Shoe

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Raleich

JOHN A. WALKER

North Wilkesboro

DEFENDANT’S EXHIBIT 3

January 29, 1982

TO: COUNTY BOARD MEMBERS ANT) SUPERVISORS

FROM: BOB SPEARMAN, CHAIRMAN

ALEX BROCK, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

SUBJECT: CITIZEN AWARENESS YEAR AND VOTER

REGISTRATION

At the request of the State Board of Elections,

Governor James Hunt has designated 1982 as a Citizen

Awareness Year in which a maximum effort will be made to

increase North Carolina voter registration.

The State Board will sponsor two major voter

registration drives, from April 15, 1982 to July 5, 1982

before the primary and from September 1 to October 4

(when registration closes for the general election.)

The voter registration drive is officially spon

Ex-59

sored and is nonpartisan. All political parties and civic

groups are invited and encouraged to participate.

Obviously, the success of this effort will depend

very much upon you because you are the public officials most

familiar with the election process and closest to its day-to-

day operation.

There will be two main thrusts to the voter

registration drive: (1 ) Maximum publicity of existing voter

registration opportunities and (2 ) Provision of special

registration opportunities to maximize participation.

The State Board intends to take all possible steps

to maximize statewide publicity, including holding press

conferences and providing public service spots to radio and

television stations. We request that your local board take

similar steps in your county or municipality. Specifically, you

may wish to consider the following:

Check with local T.Y. and radio stations to

determine if they will produce and broadcast public service

spots telling county citizens when and where they can

register to vote. (The spot announcements can be made by

different board members.)

Issue press releases on Citizen Awareness Year

in your area and registration opportunities.

Post signs or notices with registration informa

tion in public places (e.g. county offices, stores, community

bulletin boards.)

Check with county and municipal officials to see

if they would agree to have basic voter registration informa

tion included with routine official mailings (e.g. with tax

notices or municipal water bills.)

Special Registration Opportunities.

In addition to publicizing existing registration

opportunities, we need to take extra steps to reach groups

Ex-60

whose registration has historically been low. Situations vary

in different areas of the State, but frequently groups with low

registration include elderly citizens, young people, and

minority groups. We request you consider using the following

outreach techniques during Citizen Awareness Year, particu

larly from April 15, 1982 to July 5, 1982 and September 1 to

October 4, 1982.

1. Staff registration tables in evening hours at

places where large groups of people congregate (shopping

centers are often excellent.)

2. Have a “registration day” in the spring and

again in the fall in local public high schools and community

colleges; on these days send registrars and commissioners to

register students and faculty at their educational institutions.

3. Send registrars or commissioners for special

registration events to residential areas where registration is

low. These may include nursing homes, public housing or

mobile home parks.

4. Upon request; supply registrars or commis

sioners for special events being run by community groups,

such as banquets, dinners, picnics, athletic contests, church

suppers, etc. (Very frequently, this can be done without any

cost to the board because registrars or commissioners will

donate their time and not expect to be paid.)

We expect that local boards will receive requests

from political parties and community groups for assistance

in special registration efforts during Citizens Awareness

Year.

When you receive such requests, try to be as

helpful as you can in answering questions, supplying voter

registration information and where necessary, helping to

find registrars, judges, and special registration commis

sioners who can assist in registering voters at special

events.

Ex-61

DEFENDANT’S

EXHIBIT

14

North Carolina Voter Registration February,

1982-October, 1982

White Voters

Non-White

Voters All Voters

Registered Registered Registered

2/9/82 2,081,836 401,962 2,483,798

3/31/82 2,108,211 416,735

6/1/82 2,160,579 455,368

10/4/82 2,201,189 470.638 2,671,827

Absolute

Increase

2/9/82 to 6/1/82 78,743 53,406 132,149

% increase

2/9/82 to 6/1/82 3.7% 13.2% 5%

Absolute

Increase

2/9/82 to 10/4/82 119,353 68,676 188,029

% increase

2/9/82 to 10/4/82 5.7% 17% 7.5 %

Approximate Percent of Voting Age Population*

Registered

2/9/82 58.6%

6/1/82 61.7%

10/4/82 63.1%

*based upon February, 1982 population statistics.

Ex-62

Voter Registration Increases For Selected Counties From

February 1982 to October 1982

County

Increase

White

Registered

Voters

%

Increase

Forsyth 4,105 4%

Mecklenburg 6,493 4%

Wake 4,416 4%

Durham 2,246 5%

Nash 802 4%

Edgecombe 215 2%

Wilson 952 5%

Halifax 676 5%

Bertie 431 10%

Chowan 131 3%

Gates 141 6%

Hertford 456 9%

Martin 202 3%

Northampton 1,029 22%

Washington 195 4%

Increase

Non-White

Registered

Voters

%

Increase

Total %

Increase

All

Voters

2,880 13% 6%

2,896 9% 5%

2,292 11% 5%

3,565 21% 9%

1,620 37% 10%

3,310 54% 19%

2,193 46% 14%

2,507 36% 16%

1,126 32% 20%

223 14% 6%

451 21% 13%

1,143 31% 18%

539 16% 7%

1,903 42% 32%

403 18% 9%

Ex-63

DEFENDANT’S EXHIBIT 15

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS

Suite 801 R a l e ig h B u ildin g

5 W est H a r g e t t St r e e t

R a l e ig h , North Ca ro lin a 27601

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Chairman

Members

MRS. ELLOREE M. ERWIN

Charlotte

WILLIAM A. MARSH. JR.

Durham

MRS. RUTH TURNER SEMASHKO

Horse Shoe

ROBERT W. SPEARMAN

Raleigh

JOHN A. WALKER

North Wilkesboro

January 14, 1983

Governor James B. Hunt

State Capital

Raleigh, North Carolina

Lieutenant Governor James

Green

Legislative Office Building

Raleigh, North Carolina

Speaker Liston Ramsey

North Carolina House of

Representatives

Raleigh, North Carolina

Gentlemen and Senator Woodard:

In recent months the North Carolina Board of

Elections has given careful consideration to possible recom

mendations to you concerning the conduct and administra

tion of the election laws.

Representative J. Worth

Gentry

North Carolina House of

Representatives

Raleigh, North Carolina

Senator Wilma C. Woodard

North Carolina State Senate

Raleigh, North Carolina

Ex-64

We have received proposals from interested citizens,

political parties, county election boards and other groups.

We wish to recommend the following six items for

legislative action in the 1983 Session. As you are aware the

State board and County Boards have in the last year made

extensive efforts to ease access to voter registration, and our

recommendations include several items in this very impor

tant area.

1. Authorization to permit the State Election Board

to name Department of Motor Vehicle drivers license

examiners as special registration commissioners.

This would enable citizens to complete voter registra

tion application when they obtain or renew their driver’s

license. Such a system has worked very well in Michigan; it

has recently been recommended by Governor Robb in

Virginia and voters in Arizona adopted it by referendum in

the recent November election. This proposal is supported by

the North Carolina Division of Motor Vehicles.

2. Legislation to permit voter registration at public

high schools with school librarians as registrars.

We are all aware that registration rates among young

people are low and need to be raised. This proposal should

lead to substantial registration increases.

3. Require public libraries to permit voter registra

tion. Public library registration has been extremely success

ful in many counties in the state. The concept is strongly

supported by county election boards.

4. Legislation providing for simultaneous issuance

of absentee ballot application and absentee ballot itself.

This reform would reduce postage costs and make it

easier for qualified persons to vote absentee without

eliminating any of our existing safeguards.

5. Amendment of G.S. 163-22.1 to permit State

Elections Board to order a new election when legally

Ex-65

appropriate, after hearings have been held and findings of

fact made hy a county hoard.

This would clarify the authority of the State Board to

order a new election without unnecessarily duplicating

hearings already held hy a county hoard. The amendment

would save time, money and expedite the resolution of

election contests.

6. Authorization of constitutional amendment to

grant State Board authority to issue regulations to deal with

“out of precinct” voting problem.

Citizens and election officials alike are frustrated hy

the situation where persons move from one precinct to

another within a county hut fail to transfer their registra

tion. When registration has not been changed by election day