Houston v. City of Cocoa Defendants' Response in Opposition to Plaintiffs' Application for Attorneys' Fees and Costs

Public Court Documents

November 22, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Houston v. City of Cocoa Defendants' Response in Opposition to Plaintiffs' Application for Attorneys' Fees and Costs, 1991. 5e3b897f-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e2116e9a-30cf-49d7-9596-cfd129548085/houston-v-city-of-cocoa-defendants-response-in-opposition-to-plaintiffs-application-for-attorneys-fees-and-costs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

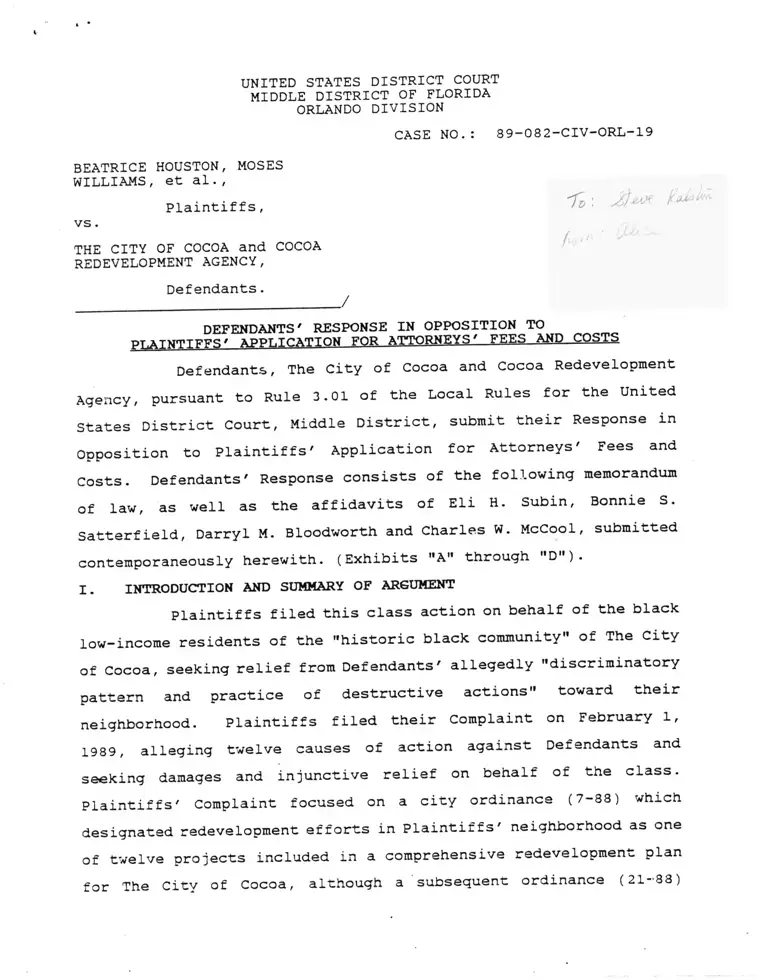

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

ORLANDO DIVISION

CASE NO.: 89-082-CIV-ORL-19

BEATRICE HOUSTON, MOSES

WILLIAMS, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

THE CITY OF COCOA and COCOA

REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY,

Defendants.

/

DEFENDANTS' RESPONSE IN OPPOSITION TO PTATNTIFFS' APPLICATION FOR ATTORNEYS' FEES AND COSTS

Defendants, The City of Cocoa and Cocoa Redevelopment

Agency, pursuant to Rule 3.01 of the Local Rules for the United

States District Court, Middle District, submit their Response in

Opposition to Plaintiffs' Application for Attorneys' Fees and

Costs. Defendants' Response consists of the following memorandum

of law, as well as the affidavits of Eli H. Subin, Bonnie S.

Satterfield, Darryl M. Bloodworth and Charles W. McCool, submitted

contemporaneously herewith. (Exhibits "A" through D ).

I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Plaintiffs filed this class action on behalf of the black

low-income residents of the "historic black community" of The City

of Cocoa, seeking relief from Defendants' allegedly "discriminatory

pattern and practice of destructive actions" toward their

neighborhood. Plaintiffs filed their Complaint on February 1,

1989, alleging twelve causes of action against Defendants and

seeking damages and injunctive relief on behalf of the class.

Plaintiffs' Complaint focused on a city ordinance (7-88) which

designated redevelopment efforts in Plaintiffs' neighborhood as one

of twelve projects included in a comprehensive redevelopment plan

for The Citv of Cocoa, although a subsequent ordinance (21-’83)

deleted the neighborhood from the redevelopment plan prior to

Plaintiffs filing this lawsuit. Plaintiffs sought to enjoin the

CITY'S redevelopment activities affecting their neighborhood and to

require the CITY to take affirmative actions to preserve and

rehabilitate the neighborhood, as well as substantial money damages

to the class Plaintiffs.

Once it became clear that the primary genesis for the

lawsuit was a misunderstanding by Plaintiffs concerning the

operation and effect of the challenged ordinance, negotiations

ensued and the parties reached a settlement in principle only

shortly after the Complaint was filed. On April 24, 1990, the

parties executed, a Consent Decree which was approved by the Court

and incorporated into a final judgment. Defendants agreed to

modify their redevelopment efforts and to take certain actions to

rehabilitate and improve the neighborhood, and agreed to pay a

nominal sum ($20,000 total to the 8 named Plaintiffs and nothing to

the 500 remaining class Plaintiffs). In return, Plaintiffs agreed

to voluntarily dismiss their Complaint with prejudice.

Despite this negotiated settlement, Plaintiffs have now

proclaimed themselves "prevailing parties" and seek more than $1.5

million in attorneys' fees and costs from Defendants. Plaintiffs'

fee application seeks a 100% multiplier "to compensate for the

contingent nature of the litigation" on a total lodestar of

$748,240.50, as compensation for 4,418.3 hours of time for

attorneys at hourly rates ranging from $125 to $240 and for a

paralegal and law clerk at hourly rates of $50 and $100.

Plaintiffs have not filed a Bill of Costs, but refer generally to

various aggregate costs in their fee application. Plaintiffs seek

this massive amount even though there was no trial and no formal

2

two-item Request fordiscovery (with the exception of a

Admissions).

Plaintiffs' are not entitled to any award of attorneys'

fees since they were not "prevailing parties." Even if this Court

finds that Plaintiffs have prevailed, they are not entitled to an

attorneys' fees and costs award remotely close to $1,517,331.20

because they have not met the burden of proof as to their

entitlement to any multiplier, much less a 100% multiplier; the

hourly rates of the non-Florida counsel used in the lodestar amount

are unnecessarily high; the attorneys' fees application is replete

with excessive, redundant or otherwise unnecessary time; and,

finally, the costs are poorly’ documented and excessive.

II. PLAINTIFFS ARE NOT ENTITLED TO AN AWARD OF ATTORNEYS' FEES

BECAUSE THEY WERE NOT "PREVAILING PARTIES."

Plaintiffs are not entitled to an award of attorney's

fees in this matter because they were not "prevailing parties"

within the meaning of the federal civil rights statute, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1988. Plaintiffs' application assumes that they are prevailing

parties without offering any factual or legal argument in support

of that conclusion. However, prior to any determination of the

merits of Plaintiffs' claims, Defendants entered into a Consent

Decree which constituted a compromise by both parties. Defendants

made no admission of liability nor were any concessions required by

law. Plaintiffs were simply not prevailing parties and are not

entitled to an award of attorneys' fees in this action.

3

A. The standard for awarding attorneys— fees under 42...U..S-._C.r_

5 1988 is discretionary. subnect--to--a--threshold

determination of prevailing party status.

Plaintiffs seek an award of attorneys' fees pursuant to

42 U.S.C. §1988. As amended, 42 U.S.C. §1988 provides in pertinent

part as follows:

In any action or proceeding to enforce a

provision of §§ 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985

1986 of this Title, Title IX of _ Public Law

92-318, or Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, the court, in its discretion may allow

the prevailing party, other than the United

States, a reasonable attorneys' fee as part of

the cost. (emphasis added).

As indicated by the statute, an award of attorneys' fees under 42

U.S.C. §1988 is discretionary. See Texas--State--Teachers

Association v. Garland Independent School— District, 489 U.S. 782

(1989). Furthermore, federal courts interpreting 42 U.S.C. §1988

have judicially imposed a very strict standard for classification

as a "prevailing party."

In Garland/ the Supreme Court recently defined a

"prevailing party" as one who "succeeded on a significant issue in

litigation" and achieved a result which, on a constitutional level,

"materially altered the legal relationship between itself and the

defendant." XI. at 791. A technical victory may be insufficient

to support prevailing party status. Id- at 792-93. See also

Crowder v. Housing Authority of the City Qf Atlanta/ 908 F.2d 843

(11th Cir. 1990).

The test for prevailing party status in the Eleventh

Circuit was set forth in Williams v ._Loath^pburv, 672 F. 2d 549 (5th

Cir. 1982), with two requirements: (1) a causal connection between

the filing of the suit and defendant's subsequent action affording

some significant relief to plaintiff, and (2) that defendant s

conduct was constitutionally .required by law, and not a wholly

gratuitous response to an action thac in itself was frivolous or

4

groundless. 672 F.2d at 551. Establishing that Plaintiffs' suit

was causally related to the Defendants' actions which improved

their condition is only half of the battle. Nadeau v. Helqemoe,

581 F.2d 275, 281 (1st Cir. 1978). A plaintiff must additionally

succeed on a significant issue in the litigation, and show that the

defendant engaged in unconstitutional behavior and that its

subsequent actions in response to plaintiff's complaint were

required by law. See Dunn v. The Florida Bar, 889 F.2d 1010, 1015

n.3 (11th Cir. 1989), cert, denied. 111 S.Ct. 46, 112 L.Ed.2d 22

(U.S. 1990) (no fees awarded when Defendant voluntarily amended

objectionable rule); Church__ of-- Scientoloqy-- Flag-- Services

organization. Inc, v. City of Clearwater, --- F. Supp. ----, 5

F.L.W. Fed. 393, 395 (M.D. Fla. 1991). O'Connor v. City and County

of Denver. 894 F.2d 1210, 1226 (10th Cir. 1990) (plaintiffs not

prevailing parties where city voluntarily amended challenged

sections of city code, since plaintiffs did not meet burden of

demonstrating unconstitutionality of repealed ordinance).

B. The Consent Decree__specifically— precludes— any

admission of liability bv Defendants-

Plaintiffs' Complaint was filed in February of 1989 and

within a matter of months the parties reached an agreement in

principle which subsequently led to the Consent Decree executed in

April of 1990. The agreement in principle was reached even before

the Court ruled on Defendants' Motion to Dismiss Plaintiffs

Complaint.

Xn the parties' joint memorandum seeking approval of the

Consent Decree, both parties represented to the Court that

settlement was preferable because litigation would be lengthy and

expensive for all concerned, "with the ultimate substantive and

5

remedial outcomes uncertain." In the Consent Decree itself,

Defendants did not admit any liability and maintained that the

claims asserted were without merit, but desired to settle to avoid

further expense, inconvenience, and the distraction of burdensome

litigation. See Consent Decree, p.2. Defendants wished to promote

a new spirit of harmony, cooperation, and unity in the City of

Cocoa and to collectively and cooperatively address the zoning,

housing and community development needs of Plaintiffs

neighborhood. Id. Defendants concluded that settling this lawsuit

on the terms contained in the Consent Decree was in the best

interest of the citizens of the City of Cocoa. Id.

Defendants did not at any point concede that any of their

actions challenged by Plaintiffs were unconstitutional, nor did the

Court make any such determination. Rather, Defendants made a

practical decision, based on economic and public policy

considerations, to compromise with Plaintiffs in resolving a

divisive and potentially costly dispute.

C. Plaintiffs did not vindicate a civil fight at i,ssue

in the litigation.

Consistent with the policy underlying 42 U.S.C. § 1988

Plaintiffs must vindicate a civil right at issue in the litigation

against the violation of that civil right to qualify as prevailing

parties. Dunn v. The Florida— Sail/ 889 F.2d 1010, 1014.

Achievement of the goal sought in the Complaint does not justify an

award of attorneys' fees unless that result is required by

constitutional factors. A plaintiff is not entitled to recover

attorneys' fees if the defendant simply complies with plaintiff s

demands and moots the case for reasons unrelated to the potential

merit of the suit. Whether activated by economic, political, or

6

purely personal concerns, a defendant may choose voluntarily to

make the change sought in the suit rather than undergo protracted

and expensive litigation. Id. at 1015. Defendants' conduct must

be required by law and not a wholly gratuitous response for reasons

unrelated to the potential merit of the suit. If Defendants'

conduct, although it may be to Plaintiffs' interest, is not

required by law, then Defendants must be held to have acted

gratuitously and Plaintiffs have not prevailed in a legal sense.

Id.

In Dunn, decided after the Supreme Court decision in

Garland, plaintiffs sought an amendment to a rule of The Florida

Bar regulating unauthorized practice of law. Plaintiffs alleged

that the rule unconstitutionally denied access to the legal system

to those unable to pay for matters such as divorce. 889 F.2d at

1011. During the pendency of the action, The Florida Bar Board of

Governors amended the challenged rule, and included changes

proposed by Plaintiffs' counsel in a letter to the Bar. !£• at

1012. Plaintiffs subsequently dismissed the case because i_hey

"obtained substantially all of the relief which they had sought."

There was no adjudication of the merits of Plaintiffs' claim, id.

at 1013. The Eleventh Circuit upheld the district court's denial

of attorneys' fees to plaintiffs, holding that plaintiffs had

failed the second prong of the beatheybuyv test. Id. at 1018. The

Eleventh Circuit held that it could not find that defendants took

their actions under any constitutional compulsion, but rather to

correct a wrong to serve the best interest of the citizens of the

state. The court specifically held that considerations of policy

and strategy, rather than any constitutional directive, motivated

7

defendants' conduct, and therefore precluded any award of fees to

plaintiffs. Id.

Here, Plaintiffs sought to prevent their "displacement

from their neighborhood, thus "removing them from access to basic

services and eliminating the black presence from the downtown

area." See Complaint, J 4. Their Complaint repeatedly refers to

Defendants' actions of alleged discrimination as depriving

Plaintiffs of "access to decent, safe, sanitary, and affordable

housing." See Complaint, KH 25, 86, 90, 91. However, there is no

constitutional right of access to dwellings of a particular

quality, nor is the assurance of adequate housing a constitutional

mandate. T.indsav v. Normet, 405 U.S. 56, 74 (1972). Low income

minority individuals have no constitutional right to be furnished

safe, sanitary and decent housing. Jaimes v.— Toledo Metropolitan

Hnnsinrr Authority. 758 F. 2d 1086, 1101 (6th Cir. 1985). Nor is

there any authority to support a constitutional right to a "black

presence" in any given geographical location.

The only basis offered by Plaintiffs in support of their

entitlement to attorneys' fees is that the Consent Decree secured

"extremely favorable results" for Plaintiffs. See Plaintiffs'

Application, f 9. However, this self-serving statement, even if

true, is simply not enough.

Plaintiffs have the burden of demonstrating that

Defendants' challenged behavior was unconstitutional and the result

achieved was required by law. However, Plaintiffs cannot (and have

not even attempted to) demonstrate that Defendants entered the

Consent Decree under any constitutional compulsion. Rather, it

appears clearly from the Consent Decree and other settlement

materials that Defendants settled the action to avoid the expense,

8

inconvenience and distraction of litigation, and because they made

a public policy decision to promote harmony and cooperation with

the residents of the Plaintiffs' neighborhood. Defendants' actions

are in harmony with principles of responsible dispute resolution

and efficient use of the Court system, and should not be punished

by an improper award of fees.

D. Piihl i r. policy considerations---dictate— that

Plaintiffs should not be awarded attorneys— fees.

Federal courts have expressed concern that awarding

attorneys' fees in all civil rights actions where the plaintiff

obtains some relief will unduly encourage private attorneys general

to commence all sorts of actions of whatever magnitude, even if of

negligible constitutional priority. Naprstek v. City of Norwich,

433 F. Supp. 1369, 1370 (N.D. N.Y. 1977). See also Gpgenside.J^

Arivoshi. 526 F. Supp. .1194, 1197 (D. Hawaii 1981) ("neither

Congress nor the Supreme Court intended that private attorneys

general need be encouraged to make mountains out of molehills. )

Indeed, it was for this reason that Congress specifically

considered and rejected the option of providing mandatory awards of

attorneys' fees in civil rights actions, wisely leaving such awards

to the courts' discretion, to be exercised as each case warrants.

Id. Moreover, the fear of a significant attorneys' fee award may

force Defendants to continue litigating an issue, not because they

wish to establish a legal principle or avoid meeting plaintiff's

concerns, but solely to escape if possible from onerous attorneys'

fees. Nadeau v. Helaemoe. 581 F.2d 275, 281 (1st Cir. 1978).

As set forth in the Affidavit of Charles W. McCool

(Exhibit "D"), the former City Manager of the City of Cocoa,

efforts by Defendants to resolve this dispute prior to the filing

9

of a lawsuit were rebuffed by Plaintiffs' counsel, who repeatedly

threatened that Plaintiffs' claims would cost the City "multi

millions" of dollars. Only after HUD representatives intervened

and discovered that many of Plaintiffs' grievances were based on

their misunderstanding of the operation and effect of Ordinance 7-

88 did Defendants perceive any possibility of reaching a

settlement. A subsequent meeting with Plaintiffs' representatives

led to the Agreement in Principle which essentially resolved the

dispute (except for the issue of attorneys' fees). If Plaintiffs

had pursued meaningful substantive discussions of their claims

prior to filing the lawsuit, it is likely that the parties could

have resolved the dispute without the intervening cost, time, and

animosities engendered by litigation. Plaintiffs brought claims

that Defendants deemed to be of questionable merit. However,

Defendants found it in the best interest of all citizens of the

City of Cocoa to avoid the expense and divisiveness of litigation

and settle the matter on terms which Defendants would have agreed

to prior to the filing of this lawsuit. See Affidavit of Charles

W. McCool (Exhibit "D"). Plaintiffs should not be rewarded for

"making a mountain out of a molehill" by burdening other citizens

of the City of Cocoa with unwarranted attorneys' fees.

III. PLAINTIFFS HAVE NOT SHOWN THAT ENHANCEMENT IS NECESSARY.

Courts should not generally increase the requested

lodestar amount since enhancement is reserved for "exceptional

cases" in which counsel was retained on a contingent basis and

there was a "real risk-of-not-prevailing" to some extent.

Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley Citizens'— Coupe i.j,— for Clean AiX/

483 U.S. 711, 730 (1987); Perkins v. Mobile Housing Board, 847 F.2d

735, 738 (11th Cir. 1988) (enhancement reserved for "rare cases").

10

Exceptional cases require a showing of exceptional results- Nogmah

v. Housing Authority of City of_Montgomery, 836 F.2d 1292, 1302

(11th Cir. 1988).

In addition to proving that counsel was retained on a

contingency basis with a risk of not prevailing and that the case

was exceptional, the party seeking an enhancement bears the burden

of "adduc[ing] affirmative evidence to show: (1) that it would have

faced substantial difficulty in locating counsel in the relevant

market without a contingency multiplier; and, (2) not that the

legal risks of the particular case warrant enhancement, but instead

that the rate of compensation for 'contingent fee cases as a class'

in the relevant market was different from cases in which payment_

was certain." Martin v. University of South Alabama, 911 F.2d 604,

611 (11th Cir.), reh'a en banc denied, 922 F. 2d 849 (11th Cir.

1990). Enhancement must be supported by more than simply

generalized findings that the number of competent civil rights

class action attorneys has diminished considerably. Id* at 612.

The Eleventh Circuit has also stated that enhancement must be

supported by "specific evidence . . . to show that the quality of

representation was superior to that which one would reasonably

expect in light of the rates claimed." Norman, 836 F.2d at 1302.

In this case, Plaintiffs have not met their burden.

First and foremost, there is no proof in the application that the

case indeed was taken on a contingent fee basis. Plaintiffs' fee

application does not contain a copy of any such agreement, nor is

there any affidavit testimony as to the particulars of the

contingent fee arrangement, nor as to the arrangement among the

three law firms representing the Plaintiffs.

11

Moreover, Plaintiffs have not shown how the consent

judgment produced exceptional results, which have been defined as

results that are out of the ordinary, unusual

or rare. Ordinarily, results are not

exceptional merely because of the nature of

the right vindicated or the amount recovered.

The law is usually faithful to its teachings,

and so an outcome that is not unexpected in

the context of extant substantive law will not

ordinarily be exceptional.

Norman. 836 F.2d at 1302.

Instead of including a specific showing of the

exceptional nature of the results obtained by the settlement of

this litigation, the fee application contains self-serving,

conclusory affidavits from Plaintiffs' counsel and their two

experts about the favorable nature of the settlement. Plaintiffs

supplemental Affidavit of Peter I. Shapiro, served November 1,

1991, contains but a single paragraph addressing, in general terms,

the results of the consent judgment and fails to analyze with any

specificity the substance of the disputed ordinance (7-88) or the

amended Comprehensive Plan, as enacted pursuant to the Consent

Decree. Mr. Shapiro's Affidavit does not have the necessary

framework from which to judge the results of the settlement.. On

the other hand, the Affidavit of Eli H. Subin (Exhibit "A")

analyzes the substance of Ordinance 7-88 and the amendments to the

comprehensive plan and concludes that the same result may have been

achieved without litigation. (pp. 12, 13). See also Affidavit of

Bonnie S. Satterfield (Exhibit "B," p.ll). Any plaintiff in civil

rights litigation must be mindful of the ruling in North Carolina

Dept, of Transportation v. Crest Street Community— Counc — lnc • >

479 U.S. 6 (1986), that an action under 42 U.S.C. §1988 may not be

maintained solely to recover fees.

12

Similarly, Plaintiffs have not submitted "specific

evidence" to show that the quality of their attorneys'

representation was superior to that which one would reasonably

expect from a $220 per hour lawyer who spends 399.3 hours on the

matter (Penda Hair); a $185 per hour lawyer who spends 325.3 hours

on the matter (Karl Coplan); a $175 per hour lawyer who spends

1,873.3 hours on the matter (Judith E. Koons); and a $170 per hour

lawyer who spends 1,191.2 hours on the matter (Jon C. Dubin).

Plaintiffs' counsel have also failed to submit persuasive

proof of the "substantial difficulties" in finding counsel in the

local or relevant market without a contingency multiplier, Martin

v university of -south Alabama, 911 F.2d at 612, (quoting Delaware

Valiev II. 483 U.S. at 733). Indeed, on this point, Plaintiffs

have only submitted the Affidavit of Peter H. Barber, which shows

no familiarity with Plaintiffs' claims and has but a single

paragraph devoted to the issue of enhancement, and the Affidavit of

Robert I. Shapiro which contains only general observations and

advances a "rationale [which] could be used to justify enhancement

in almost any civil rights case. . . . [and] a standard [that may]

be arbitrarily or unjustly applied." Maftjp v. University of South

Alabama. 911 F.2d at 612. Additionally, Mr. Shapiro's opinions on

the availability of civil rights counsel are also at odds with

those of Mr. Subin.

Because of the lack of detail contained in Barber's and

Shapiro's affidavits, this Court should not give much weight, if

any at all, to their opinions. The Eleventh Circuit in Norman v ._

Housing Authority of City of Montgomery. 836 F.2d at 1299, when

discussing opinion evidence of the reasonableness of the requested

lodestar rate, stated that, "[t]he weight to be given to opinion

13

evidence of course will be affected by the detail contained in the

testimony." Here, where Plaintiffs must meet the stiff burden of

proving that this is a "rare," "exceptional" case, the generalized,

conclusory statements concerning "the contingency nature of the

litigation" and the "extremely favorable results" of the litigation

are not sufficient to justify a multiplier of any amount, much less

for 100%. Moreover, the other statements concerning the riskiness

and complexity of Plaintiffs' case and theories are irrelevant to

the consideration of whether an enhancement is proper, since those

factors should be reflected in the lodestar, Martin v. Univepsitv

of Smith Alabama. 911 F.2d 611-612, which in itself is excessive.

IV. THE LODESTAR REQUESTED IS UNREASONABLE.

The calculation of a reasonable attorneys' fee is clearly

within the discretion of the trial judge, Hensley v. Sckerh^r.t , 461

U.S. 424, 437 (1983), and is determined by multiplying a reasonable

hourly rate times the number of hours reasonably expended. Norman,

836 F.2d at 1299. A reasonable hourly rate has been defined as

"the prevailing market rate in the relevant legal community for

similar services by lawyers of reasonably comparable skills,

experience, and reputation." id;., (citing 8itm—3Ls— Stenson, 465

U.S. 886, 895-96, n.ll (1984)). The Nprman court stated that the

fee applicant "bears the burden of producing satisfactory evidence

that the requested rate is in line with prevailing market rates. .

[the] satisfactory evidence necessarily must speak to rai.es

actually billed and paid in similar lawsuits." Id-

Plaintiffs have not met this burden. Instead, Plaintiffs

have submitted a generalized "affirmation" of a partner in a New

York law firm to attempt to justify the higher rates sought; this

14

"affirmation" exhibits no familiarity with the particulars of this

case, nor with the prevailing market rates in the Middle District

of Florida, nor with the rates actually billed and paid in similar

lawsuits. Likewise, the affidavits of Peter Barber and Robert I.

Shapiro do not address rates actually billed and paid in similar

lawsuits, and do not establish that it is customary to charge

$11,190 for the time of a law clerk (Ronald Slye). Finally,

Plaintiffs have violated the lesson of Hensley that "excessive,

redundant or otherwise unnecessary" hours should be excluded from

the fee petition. 461 U.S. at 434.

A. The lodestar hours are excessive, redundant or otherwise

unnecessary.

In addition to failing to meet the evidentiary burden,

Plaintiff's fee application does not follow the Norman court's

suggested framework which calls for "a summary, grouping the time

entries by the nature of the activity or stage of the case." 836

F.2d at 1303. A summary of time spent on this case would have been

especially helpful in analyzing the massive number of hours

expended, and Plaintiffs' failure to provide a summary grouping of

time entries creates a burden which would justify substantially

reducing the award of fees claimed. For the Court's convenience,

Defendant has prepared a summary and grouped the approximate time

entries into seven principal categories.1 When the approximate

"Defendants' summaries (Exhibit "E"), submitted simultaneously

herewith, reflect approximate amounts of time since w n y o

Plaintiffs' time records were not broken down by individual task

for each day. Since the time records of Judith E. Koons that are

attached to Plaintiffs' Application contain only a daily total for

her time, Defendants submit contemporaneously herewith as Exhibit

"F " an exhibit from her deposition, which are her records that

show the time she recorded daily for each task, as well as a dai y

total.

15

time entries are viewed in terms of the nature of the activity or

stage of the case, as below, it is clear that Plaintiffs' counsel

spent,, excessive and redundant time on this case.

Activitv Approximate Hours

1. Meetings, consultations and

telephone conferences with 985co-counsel

2 . Document review and editing

(other than Complaint) 1,070

3 . Drafting, editing and

reviewing the Complaint 250

4 . Legal research and memos of

law pre-Complaint 330

5. Legal research post-Complaint 160

6 . Fact investigation, client

meetings; and appearances at 1,015City board meetings

7 . Class certification/4.04 motion 155

Sub'-total2 3,965

In determining whether the hours billed are reasonable,

the fee applicant should bear in mind that , "[h]ours that are not

properly hill Ad to one's client also are not properly billed to

one's adversary pursuant to statutory authority." Bepslev v,.

Pnkerhart. 461 U.S. 424, 434 (citation omitted) (emphasis in

original). This type of analysis requires a recognition "that in

2The remainder of Plaintiffs' time appears to have been spent

on an administrative proceeding, speaking with the press,

traveling, opposing a motion to intervene (approximately 40 hours),

preparing the application for attorneys' fees (approximately 70

hours), speaking and meeting with persons other than clients or co

counsel, and on other miscellaneous tasks.

16

the private sector the economically rational person engages in some

cost benefit analysis." Norman 836 F.2d at 1301.

1. Excessive time.

For lawyers who hold themselves out to be experts in the

field of civil rights litigation, 4,418.3 hours is clearly

excessive for preparing and filing a complaint, obtaining class

certification, participating in a related administrative

proceeding,3 and negotiating a settlement.

When the time entries are analyzed by the nature of the

activity, it is clear that Plaintiffs could have expended

substantially fewer hours. Defendants' expert Eli H. Subin in his

affidavit (Exhibit "A," pp. 10-11) asserts that a skilled attorney

and a staff of one associate and one paralegal should have

reasonably expended no more than 80 hours to draft a complaint, 100

hours to negotiate the settlement and attend meetings of the City

Council, 100 hours to draft the settlement papers, and 154 hours

for miscellaneous tasks, for a total of 500 hours to accomplish all

of Plaintiffs' tasks in this litigation. S^e also Affidavit of

Bonnie S. Satterfield (Exhibit "B," p. 10).

The relative ease and speed with which the settlement was

achieved raises a question as to whether this case was even

necessary and certainly contradicts the Plaintiffs'

characterization of this dispute as a difficult and novel case

which would warrant an enormous attorneys' fees and costs award.

The lodestar can be reduced where it is found that the case was not

"Plaintiffs presumably request compensation for the

administrative agency proceeding but do not show why the same

should be compensable under 28 U.S.C. §1988.

17

novel and difficult. Winter v. Cerro Gordo— County., Conservation

Board. 925 F.2d 1069, 1074 (8th Cir. 1991).

2. Redundant hours.

This case exemplifies the statement made by the Norman

court that "[r]edundant hours generally occur where more than one

attorney represents a client." 836 F.2d. at 1301-1302. Although

the Eleventh Circuit Court also stated that " [t]here is nothing

inherently unreasonable about a client having multiple attorneys,

and they may all be compensated if they are not unreasonably doing

the same work and are being compensated for the distinct

contribution of each lawyer," Id^, it is clear that the time spent

in this case was redundant. For example, Jon Dubin and Judith E.

Koons spent approximately 160 hours drafting the Complaint, only to

present it to Penda Hair and have her spend approximately 60 hours

drafting the Complaint as well. (Deposition of Judy Koons pp.73-

74; 143-144).

Additionally, there were numerous meetings with clients

which were attended by both Judith E. Koons and Jon Dubin. In

fact, Judith E. Koons spent approximately 379 hours investigating

facts and meeting with the clients prior to filing the Complaint

and Jon Dubin and Mary Wright spent approximately 187 and 172

hours, respectively, on the same activity. Jean McCarroll is

seeking recovery for 89.2 hours, of which a maximum of about 9.4

hours was spent in an activity other than meeting and speaking with

co—counsel and reviewing documents or court papers. Similarly, of

John Boger's 40.0 hours, only 2.8 were spent in an activity other

than reviewing documents or court papers or speaking with co

counsel or staff members. Finally, all, of William Abbuel's 30.6

13

hours were spent in meetings and conferences or reviewing

documents.

In short, Plaintiff's fee application reveals that

counsel have not followed the guidelines suggested by §24.22 of the

Manual for Comdex Litigation, Second f 1985.1, which urges restraint

when many counsel are involved or otherwise the hours spent can be

"absurd." In this case, Plaintiffs spent an "absurd" amount of

time on many tasks, especially conferring among themselves for

approximately 985 hours.

3. Unnecessary hours.

The fee application is replete with unnecessary hours,

from Penda Hair and Jon Dubin spending approximately 7.1 and 15.7

hours, respectively, on press coverage, to Judith Koons attending

a luncheon (3.6 hours on 5/10/88); to time spent by Jon Dubin and

Penda Hair on tasks that should have been delegated to secretaries

or legal assistants. See Affidavit of Bonnie S. Satterfield

(Exhibit "B," p. 8).

V. PLAINTIFFS7 COSTS AND EXPENSES SHOULD BE DENIED OR REDUCED

This Court should exercise its discretion and deny

Plaintiffs' application for costs and expenses. The dispute was

settled favorably for both parties; the results of the Consent

Decree do not justify the costs and expenses sought; and

Plaintiffs' supporting documentation for the costs is inadequate.

Moreover, Plaintiffs have not followed the proper procedure, in

that they did not file itemized amounts sought in a. separate bill

of costs, which is required by Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(d) and 28 U.S.C.

§1920, Desisto College. Inc, v. Town of_Howey-in-the-Hfljs, 718

F.S. 906, 911 (M.D. Fla 1989), aff'd, 914 F. 2d 267 ( 11th Cir.

1990), nor have Plaintiffs shown why the costs should be properly

19

taxed against the City of Cocoa. See Crawford—Fitting Co_.—y_i— — ; T .

ci bbons. Inc. . 482 U.S. 437, 442 (1987). Finally, the Supreme

Court has recently ruled that the expert witness fees and other

costs sought by Plaintiffs are not recoverable under 42 U.S.C.

§1988. West Virginia Hospitals. Tnc. v. Casev, 499 U.S. ----, 113

L.Ed.2d 68 (1991).

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this Court should deny

Plaintiffs' Application for Attorneys' Fees and Costs relegating

all oarties to the settlement to bear their own expenses.

Respectfully submitted,

MATHEWS, SMITH & RAILEY, P-A-

By: __Lawrence G. Mathews, Jr.

Florida Bar No. 174813

Frank M. Bedell

Florida Bar No. 653942

255 S. Orange Ave., Suite 801

Post Office Box 4976

Orlando, Florida 32302-4976

Telephone: 407/872-2200

Telecopier: 407/423-1038

Attorneys for Defendant,

20

c e r t i f i c a t e o f s e r v i c e

I HEREBY CERTIFY that a true and correct copy of the

foregoing has been furnished by U.S. Mail this -- day of

P^Qv/ Qva/1/^_____ , 1991/ to James K. Green, Esq., James K.

Green, P.A., One Clearlake Centre, Suite 1300, 250 Australian

Avenue South, West Palm Beach, FL 33401; Judith E. Koons, Esq.,

Central Florida Legal Services, Inc., Rockledge Plaza, Suite F,

1255 South Florida Avenue, Rockledge, FL 32955; Julius Levonne

Chambers, Esq., Alice L. Brown, Esq., NAACP Legal Defense Fund,

Inc., 99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600, New York, NY 10013; Penda D.

Hair, Esq., NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., 1275 K

Street, N.W., Suite 301, Washington, D.C. 20005; Jean M.

McCarroll, Esq., Karl Coplan, Esq., Berle, Kass & Case, 45

Rockefeller Plaza, Suite 2350, New York, NY 10111; and Jon C.

Dubin, Esq., St. Mary's University Law School, One Camino Santa

Maria, San Antonio, TX 78228-8602.

MATHEWS, SMITH & RAILEY, P.A.

By: Lawrence G. Mathews, Jr.

Florida Bar No. 174813

Frank M. Bedell Florida Bar No. 653942

255 S. Orange Ave., Suite 801

Post Office Box 4976

Orlando, Florida 32802-4976

Telephone: 407/872-2200

Telecopier: 407/423-1033

Attorneys for Defendant,

c: \<*p51\SCOTTS\F««.Opp

11/22/91:owp