Bazemore v. Friday Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bazemore v. Friday Brief for Petitioners, 1985. 6e1d8e12-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e21f02f2-7215-4ef8-acd2-a485c60ecd2c/bazemore-v-friday-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

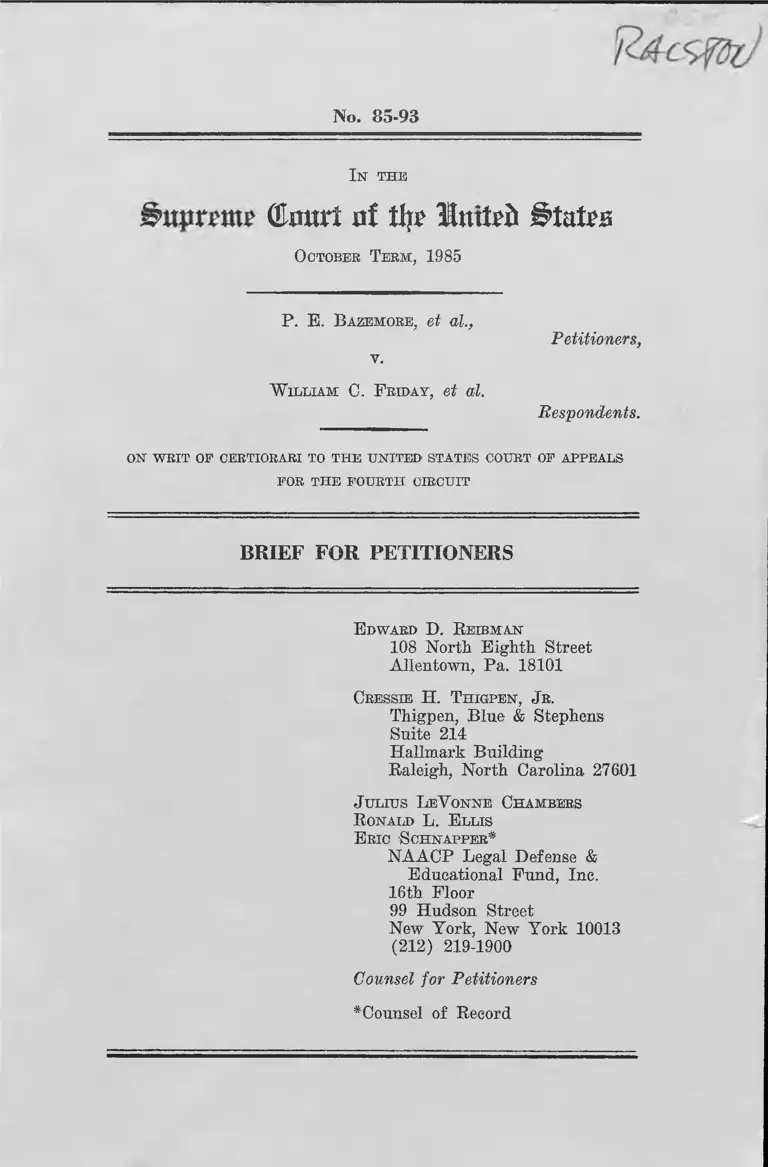

No. 85-93

In t h e

Qkmrt ni % Intfrd States

October Term, 1985

P. E. B azemobe, et al.,

v.

W illiam C. F riday, et al.

Petitioners,

Respondents.

on w r it op certiorari to t h e u n ited states court op appeals

EOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

E dward D. Reibman

108 North Eighth Street

Allentown, Pa. 18101

Cressie H. Thigpen, J r.

Thigpen, Blue & Stephen's

Suite 214

Hallmark Building

Raleigh, North Carolina 27601

J ulius LeVonne Chambers

R onald L. E llis

E ric S chnapper*

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Ine.

16th Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Petitioners

*Counsel of Record

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

(1) Do Title VII and the Fourteenth

Amendment permit a state to intentionally

pay black employees less than white

employees in the same job, so long as the

original decision establishing that

discriminatory wage differential was not

itself the subject of a separate charge or

action?

(2) Did the court of appeals err in

holding that statistics may not be treated

as probative evidence of discrimination

unless the statistical analysis considers

every conceivable non-racial variable?

(3) May a state satisfy its obli

gation to desegregate a de jure system by

i

adopting a freedom of choice plan that

fails?

(4) May an employer immunize itself

from liability for employment discrimi

nation by delegating its employment

decisions to a discriminatory third party?

(5) Did the court of appeals err in

holding that this case should not be

certified as a claim action?*

* The parties to this litigation are set

forth at pp. iii-vi of the petition.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Pa9e

Questions Presented ............. i

Table of Authorities ............. v

Opinions Below »....-............... 2

Jurisdiction ....... 2

Statement of the Case ........... 6

Statement of the Facts ........... 18

Summary of Argument ....... 23

ARGUMENT

I. Title VII and the Four

teenth Amendment Prohibit

A Public Employer From

Applying, As Well as

Establishing, a Racially

Based Salary System ..... 23

(1) Salary Discrimination

Is A Continuing Vio

lation of the Equal

Pay Act ............. 25

(2) Neither Teamsters

nor Evans Supports

the Decision Below .. 32

(3) Salary Discrimination

Is A Continuing vio

lation of the Four

teenth Amendment ....

- iii -

40

Page

Petitioners Established

the Existence of Post-

1965 Intentional Salary

Discrimination ........... 45

(1) Petitioners® Statis

tics Established a

Prima Facie Case of

Discrimination ...... 47

(2) Respondents Failed

to Rebut That Prima

Facie Case .......... 60

Title VII and the Four

teenth Amendment Place

on Public Agencies a Non-

Delegable Duty to Act in

a Non-Discriminatory

Manner .................... 71

The Courts Below Erred in

holding NCAES Had No Obli

gation to Disestablish a

State Created System of

Government Sponsored Single

Race 4-H and Extension

Homemaker Clubs .......... 87

(1) The History of the

Clubs ............... 87

(2) The Applicable Legal

Requirments ........ 94

IV

Page

V. The Courts Below Erred in

Refusing to Certify this

Case as a Class Action .... 99

CONCLUSION ......... 1 1 Q

APPENDIX: Statutes, Regulations, and

Constitutional Provisions

Involved ..... 1 a

v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Aooad v. Detroit Board of Educa

tion, 431 U.S. 209 (1977) ... 88

Adickes v. S . H. Kress Co., 398

U.S, 144 ( 1970) ... ......... 79

Alston v. School Board of Norfolk,

112 F .2d 992 (4th Cir.

1940) ........ ............ ... 41

Arizona Governing Board v.

Norris, 403 U.S. 1073

(1983) ..... ......... . ..... 21 ,76,79

Bell v. Georgia Dental Ass'n, 231

F.Supp. 299 (N.D. Ga.

1964) ...... ................. 82

Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U.S. 715

(1961 ) .............. 79

Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S.

440 ( 1982) ...... 56

Corning Glass Works v. Brennan,

417 U.S. 188 (1974).. 18,19,25,26,28

30-31

County of Washington v. Gunther,

452 U.S. 161 ( 1981 ) ....... 19,26,27

Craig v. Boren, 429 U.S. 190

(1 976) .............. 41,51

Craik v . Minnesota State Univer

sity Bd., 731 F.2d 465 (8th

Cir. 1984) 67,72

vi

Page

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S.

321 ( 1977) ............. 20,49,62,64

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin,

417 U.S. 156 { 1974) .......... 22,107

Falcon v. General Telephone Co.,

628 F.2d 369 (5th Cir.

1980) ........... 70

General Building Contractors v.

Pennsylvania, 458 U.S. 375

( 1982)....................... 82-85

General Telephone Co. v . EEOC,

446 U.S. 318 (1980) ....... 23,100-02

Green v. County School Bd., 391

U.S. 430 (1968) .......... 42,97,98

Griffin v. County School Bd.,

377 U.S. 218 ( 1964) ........ 42

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401

U.S. 424 (1971) .............. 68,83

Guardians Association v. Civil

Service Commission, 630 F .2d

79 (2d Cir. 1980) ..... ..... 64

Guinn v. United States, 238

U.S. 347 (1915) .............. 43

Hazelwood School District v .

United States, 433 U.S.

299 (1977) . ....... ...... 16,56,58,60

vii

Page

Laffey v. Northwest Airlines, Inc.,

567 F .2d 429 (D.C. Cir„

1978) 37

Lee v. Macon County, 267 F.Supp.

458 (M.D. Ala. 1966) ........ 86

Lee v. Washington, 390 U.S. 333

(1968) ......... 109

Mayor v . Educational Equality

League, 415 U.S. 605

( 1974) ............. ........ 56,58,60

Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d

696 (5th Cir. 1962) ............ 82

Movement for Opportunity v.

General Motors, 622 F .2d

1235 (7th Cir. 1980) ........ 70

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370

(1890) .................... 50,58,59

Norman v. Missouri Pacific

Railroad, 414 F .2d 73

(8th Cir. 1969) ............. 37

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U.S.

463 ( 1947).................. . 20,62

Paxton v. Union National Bank,

688 F .2d 552 (8th Cir.

1982) .............. 55

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S.

537 (1895) ................... 41

- viii -

s-efeaver- v . Rhodes , 416 0. S . 232

(1974) ....... ....... ....... 88

Smith v. Allwright, 321 u.S.

649 ( 1944) .................. 80

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100

U.S. 303 (1880) ............. 42

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Bd. of Ed., 402 U.S.

1 (1971) .......... 42

Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324 (1977) --- 24,32-34,50,52,

55,60,75

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 457

(1953) ...... 81

Texas Department of Community

Affairs v. Burdine, 450

U.S. 248 (1981) .......... 54,67

Thorpe v. Housing Authority

of Durham, 393 U.S.

268 (1969) 95

Trout v. Lehman, 702 F.2d 1044

(D.C. Cir. 1983) ..... 65,70

Turner v, Fouche, 396 U.S. 346

(1970 ).......... 68

United Airlines v. Evans, 431

U.S. 533 ( 1 977) ............ 24,32-34

ix

Page

United States v. SCRAP, 412 U.S.

669 (1973) ..... . 63

Vulcan Society v . Civil Service

Comm'n , 490 F.2d 387

(2d Cir. 1973) .............. 54

Wallace v. United States, 389

U.S. 215 (1967) ............. 85

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S.

229 (1976) .................. 43

Williams v. New Orleans

Steamship Ass'n, 673 F .2d

742 (5th Cir. 1982) ......... 72

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions

Fourteenth Amendment, U.S.

Constitution ....... i,3,5,40-45,84

Fifteenth Amendment, U.S.

Constitution ..... 80

Civil Rights Act of 1964,

Title VI ............ 3,5,95,96

Civil Rights Act of 1964,

Title VII ............ passim

Equal Pay Act, 28 U.S.C.

§206(d )(1) ....... 18,19,25-30,51

28 U.S.C. § 1 254( 1 )...... 2

42 U.S.C. § 1981 82-84

x

Page

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2 (a) ....... . 32

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h) ........... 27

Section 703(h), Title VII,

Civil Rights Act of 1964 ... 33-34,39

Ore. Rev. Stat. § 137.350 ........ 37

Other Authorities

7 C.F.R. § 15.3(b)(6)(i) ....... 22,95-96

Rule 23, Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure ....... 22,102-03,

106-07

Rule 401, Federal Rules of

Evidence ..................... 53

110 Cong. Rec. (1964) ........... 28,30

H.R. Rep. 914, 8 8th Cong.,

1st Sess. ( 1964) ........... 36,53

"Perpetuation of Past Dis

crimination", 96 Harv. L.

Rev. 828 ( 1983) ........ :... 42,82

xi

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the court of appeals

is reported at 751 F.2d 662, and is set

out at pp. 346a-481a of the Appendix to

the Petition for Writ of Certiorari. The

order denying rehearing, which is not

reported, is set out at pp. 482a of that

Appendix. The district court's memorandum

of decision regarding class claims, dated

October 9, 1979, which is not reported, is

set out at J. App. 73-87. The district

court's memorandum of decision of August

20, 1982, regarding class claims, which is

not reported, is set out at pp. 3a-207a of

the Petition Appendix. The district

court's memorandum of decision regarding

2

individual claims, dated September 17,

1982, is set out at pp. 216a-345a of the

Petition Appendix.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals

was entered on December 10, 1984. A

timely petition for rehearing and sugges

tion for rehearing en banc was denied by

an evenly divided court on April 15, 1985.

July 14, 1985, was a Sunday. The petition

for writ of certiorari was filed on July

15, 1985, and was granted on November 12,

1 985 . Jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

STATEMENT OP THE CASE

This is an action seeking to redress

racial discrimination in the operation of

the North Carolina Argicultural Extension

1

Service (NCAES). NCAES is a federally

The complaint named as defendants a number

of specific NCAES officials as well as the

counties which jointly operated the NCAES

3 -

funded state agency which provides

assistance to farmers and others through

out North Carolina, and which organizes

and assists the system of 4-H and exten

sion homemaker clubs in the state.

Petitioners filed this action in November

1971, alleging that NCAES had engaged in a

variety of practices violating, inter

alia, Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights

Act and the Fourteenth Amendment. Peti

tioners subsequently amended their

complaint to include an allegation that

NCAES had violated Title VII of the 1964

Civil Rights Act, as amended in 1972, by

engaging in employment discrimination.

Several federal officials were initially

program. For simplicity this brief refers

to actions of all of these defendants as

actions of NCAES; this use of terminology

should not be understood to suggest that

only the defendant agency, as such, was

responsible for or involved in the

disputed activities.

4

named as defendants in this action. in

April, 1972, the United States intervened

as a party-plaintiff, and the district

court subsequently realigned the federal

defendants as plaintiffs-intervenors.

The private plaintiffs filed several

motions seeking certification of this case

as a class action, and seeking to certify

all the counties in North Carolina as a

defendant class. Each of these motions

was denied. The trial of this action

focused on four distinct claims which

remain in dispute. First, petitioners

alleged that different base salaries

established prior to 1965 for black and

white workers in the same job had remained

in effect, and that blacks hired before

1965 thus continued to be paid less than

their white colleagues. Second, peti

tioners alleged that for more than a

decade after 1965 respondents continued to

5

engage in intentional racial discrimi

nation in compensation. Third, peti

tioners alleged that respondents had

engaged in intentional racial discrimi

nation in selecting the paid county

chairman responsible for supervising the

NCAES office in each county. Fourth,

petitioners asserted that continued state

assistance to several thousand single race

4—H and extension homemaker clubs violated

both Title VI and the Fourteenth Amend-

2

ment.

The district court

the court of appeals

petitioners' claims.

and a majority of

rejected all of

Judge Phillips

In addition to these claims of systematic

class wide discrimination, petitioners

sought to prove the existence of discrimi

nation against a number of specific

individuals. The courts below, in re

jecting those individuals claims, ex

pressly premised those decisions on their

view that there had been no systematic

discrimination. Pet. App. 380a, 218a n.70 (sic) .

6

dissented from the panel opinion, insist

ing that the denial of relief was error as

a matter of law. A timely petition for

rehearing and suggestion for rehearing en

banc was denied by an equally divided

court.

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

Prior to 1965 NCAES was avowedly

organized along strictly racial lines.

There were separate black and white

offices in every county, servicing

exclusively black and white citizens

respectively. NACES maintained separate

wage systems for black and white employ

ees, deliberately paying black workers

less than similarly situated whites doing

3

the same job. Both courts below found

that these racially based salary differen

tials continued well past 1971, the year

3 Pet. App. 30a, 120a, 359a, 380a, 384a,

389a, 399a.

7

4

in which this action was filed, and the

court of appeals concluded that those

5

disparities persist to this day. NCAES'

Director testified that the dual salary

system had originally been established

because there was less of a demand for

black workers than for comparable whites:

[Black home economics agents could be

hired at a lower salary than white

agents could. [B]lack agricultural

agents could be hired and retained at

a lower salary than white agricul

tural agents.

Pet. App. 30a-31a, 122a-23a, 201a, 359a,

360 .

The fourth circuit noted, "the Extension

Service admits that, while it had made

some adjustments to try to get rid of the

salary disparity resulting on account of

pre-Act discrimination, it has not made

all the adjustments necessary to get rid

of all of such disparity." Pet. App.

389a-90a.

C.A. App. 999. "C . A. App." refers to the

court of appeals appendix. Because the

underlying record is particularly volumin

ous and unwieldly, ten copies of the court

of appeals appendix have been lodged with

the clerk.

NCAES provided substantial material

and other assistance to several thousand

NCAES sponsored 4-H and extension home

maker clubs across the state? these clubs

were organized along strictly racial

lines, and NCAES employees who worked with

these clubs were assigned on a racial

basis. The NCAES operation in each county

was overseen by a paid employee known as

the county chairman. When this position

was first created in 1962, NCAES expressly

directed that it be given to the highest

ranking white employee in each county.

Every new chairman appointed between 1962

and 1965 was white.

The practice of fixing salaries or

raises on the basis of race did not end in

1965. In 1971 the Director of NCAES wrote

9

a memorandum describing the specific

reasons why race still affected salary

decisions:

Obviously one of the areas where we'd

be checked on is salary...,, Our

salaries for women and non-white men

on average are lower. Our figures

verify. Due to several factors -

The competitive market — This

is not acceptable as a reason

though.

Tradition - not just in

Ext[ension Service].

Less county support for

non-white positions.

Petitioners demonstrated that NCAES

consistently paid blacks lower salaries

than were paid to whites holding the same

positions. A direct comparison of the

average salaries of blacks and whites

working as associate agricultural agents,

the single largest job title, revealed a

persistent and substantial disparity:

7 J. App. 129; C.A. App. 1606-07; see also

J. App. 90-92.

10

Associate Agricultural

1970-81 8

Agents

Year Average Average Difference

White Black in Average

Salary Salary Salary

1970 $ 9,876 $ 8,956 $ 920

1971 10,240 9,558 682

1973 10,292 9,797 495

1 974 10,244 9,840 404

1976 12,711 1 1 ,885 826

1 979 14,754 13,518 1,236

1980 15,253 14,485 768

1981 17,035 15,849 1,186

These d i spar i ties were particularly sig-

nificant for two reasons. First, since

associate agent is a lower level job,

virtually all of the employees whose wages

are reflected in this table were hired

after 1 965. Second, in every year the

average tenure of black workers was

greater than that of white workers holding

8 Average salaries for individual years are

set forth in C.A. App. 1 562; GX 95; PX 50;

PX 100; and GX 98.

Petitioners offered

9

the same position.

data showing similar disparities in the

average salaries paid to blacks and whites

1 0

in other positions. The accuracy of these

calculations was not questioned by

respondents or by either court below.

Both parties also offered evidence in

the form of regression analyses, which

calculated differences in the average

salaries of blacks and whites who were not

only in the same job, but also had the

same education, tenure, and sex. Experts

for both the government and NCAES utilized

essentially identical statistical methods,

and arrived at essentially similar

results.

See sources cited n. 8 , supra.

See sources cited n .8 , supra; J. App. 128.

In the case of associate home economics

agents, the disparity rose from $358 in

1970 to $411 in 1981 .

Salary Disparities:

Average Amount by which Salaries of

Whites Exceeded Salaries of Blacks with

Same Position/ Education, Tenure and Sex

Year Government Defense

Regression..

Analysis

Regression._

Analysis

1 974 $257-337 $364-381

1975 312-395 384-391

1981 158-248 310-415

Experts for both sides agreed that these

salary disparities were statistically

s ign i f icant at least as late as 1975.

(Pet . App. 117-119). In an effort to

ascertain whether these disparities were

Pet. App. 117a-119a, 444a; C.A. App.

399-418, 1568, 1601; GX 123 at 289, 297,

310 (for 1974); GX 124 at 33, 39, 48, 60

(for 1975); GX 122 at 37, 46, 55 (for

1981).

Pet. App. 140a, 444-45a; C.A. App. 1681,

1693-1715; see also J. App. 159. For both

analyses differences in each year depend

on the order in which the variables were

considered. These figures do not include

adjustments for quartile ratings, which

petitioners contended was a major method

used by NCAES to discriminate in salaries

13

due to performance ratings, the defense

expert modified his analyses to compare

black and white employees with the same

ratings. That adjustment actually in

creased the demonstrated disparity in

13

wages for 1975, indicating that on average

blacks were being paid less than whites

even though NCAES believed the blacks were

doing better work than whites.

The record also showed that the

pre-1965 practice of naming only whites as

county chairman continued with little

change. Because of state requirements

that county chairmen have extensive

experience within NCAES, virtually the

only individuals considered for or

promoted to the position of county

13 J . App. 445a; C .A . App. 1716.

- 14

14

chairman are full agents. During the last

two decades blacks have constituted

1 5

approximately 25% of full agents. Since

1 963 the numbers of blacks and whites

promoted to the position of county

16

chairman were as follows:

PercentPeriod White Black Black

1962-1967 11 5 0 0%1968-1975 51 1 1 .7%1976-1981 46 5 9.8%1962-1981 2 1 2 6 2 .6%

A number of facts regarding how this

disparity came about are not in dispute.

NCAES has never promoted a black to a

Since 1972 all new county chairmen have

previously served as full agents. C.A.

App. 1755.

1 5 GX 100; C.A. App. 1562.

16 J. App. 127; GX 74; C.A.App. 1745. The

names and race of each applicant and

appointee from 1 968 through May 1981 are

set out in J. App. 114-26 and C.A. App.

1736-1742. The applicants are also listed

in the chart following Pet. App. 419a in

the court of appeals® opinion.

15

county chairmanship for which a white male

also applied. In every instance in which

a black and a white male applied for the

position of county chairman, the white

17

male was chosen. There were only six

blacks appointed county chairman during

this 19 year period; in four instances

only blacks had applied for the posi-

18

tion, and in the other two cases the only

19

white applicants were women. In the case

of vacancies for which both black and

white males applied, the number of black

appointees, 0, is 4.5 standard deviations

There were such 20 such vacancies . ( C . A.

App. 1736-40; chart following p. 419a of

the Petition Appendix.)

Carl Hodges (1971 ) , B. T. McNeill ( 1976 );

Leroy James (1978) and Hoven Royals

( 1980). See C . A. App. 1736-40; chart

following page 419a of the Petition

Appendix.

In 1979 L.C. Cooper was selected over

Emily Ballinger. C .A. App. 1 737 . In 1 981

Willie Featherstone was chosen over Ellen

Willis. 751 F .2d 652, 678.

16

below the statistically expected number.

In the case of vacancies applied for by

blacks and either white males or white

females, the number of standard deviations

20

is 3.8.

As a general rule NCAES selects a

single applicant for promotion to county

chairman; that name is then sent for

approval to county officials, and almost

invariably the counties accept NCAES'

choice. (Pet. App. 78a). Prior to 1975,

however, NCAES followed a different

procedure when both blacks and whites

applied for a vacancy; in such cases NCAES

ordinarily approved two applicants, a

black and a white, and sent both names to

21

the county officials. Where the final

on The standard deviations are calculated

using the chi-square methodology of

Hazelwood School District v. United

States, 433 U.S. 299, 311 n.17 (1977).

21 This occurred in over three-fourths of all

such pre-1975 vacancies. See sources

17

decision was thus delegated to a county,

the county always chose the white appli

cant. Beginning in 1975, NCAES followed a

different practice, in all but one

instance referring only a single name to

22

the county involved. In every case in

which a black and a white male applied for

a vacancy, and NCAES decided to select

only a single applicant, NCAES chose the

white applicant.

The only action taken by NCAES to

modify the de jure systems of 4-H and

extension homemaker clubs was to adopt a

freedom of choice plan. That plan had, as

Judge Philips noted in his dissenting

opinion below, only a "minimal" effect.

(Pet. App. 471a). On two occasions NCAES

briefly adopted proposals for affirmative

cited, n. 1 7, supra. In every instance it

selected the white. Id.

22 Id.

18

steps to disestablish this dual system; in

both instances the proposal was rescinded

at the request of NCAES' trial counsel,

who warned that such efforts to integrate

the 4-H extension clubs would "lower the

standards for our program inasmuch as we

will be forced to accept 4-H club members

. . who may not have the . . . talent to

participate in club activities." (J. App.

157; C.A . App. 1904} .

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. Title VII forbids an employer to

base an employee's compensation on a

racially motivated base wage or wage

scale, regardless of whether that base

wage or scale was established prior to

1965 . Salary discrimination is a con

tinuing violation of the Equal Pay Act,

and pre-Act discriminatory salary differ

entials became illegal on the effective

date of that Act. Corning Glass Works v.

19

Brennan, 417 U.S. 188 (1974). The

standards of the Equal Pay Act are

appl icable to an equal-pay-for-equal-work

claim under Title VII. County of Wash

ington v. Gunther, 452 U.S. 161 (1981).

In the instant case both courts below

found that prior to 1965 NCAES set

different base salaries for blacks and

whites doing the same job, and that those

salary differentials remained in effect

until at least the mid-1970's.

II. Evidence of a disparity in the

average salary of blacks and whites in the

same job is sufficient to establish a

prima facie case of salary discrimination.

Such evidence establishes a prima facie

case of salary discrimination under the

Equal Pay Act, Corning Glass Works, 417

U.S. at 197, and the same standard applies

under Title VII. Experts for both

petitioners and respondents agreed there

20

were statistically significant disparities

in the average salaries of blacks and

whites with the same job, education and

tenure. Petitioners were not obligated to

demonstrate that no possible additional

variable might have explained away those

disparities. Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433

U.S. 321 (1977).

defendant cannot rebut proof of

statist ical disparities merely by

hypothesizing that some non-racial factor

might have explained these differences. A

defendant must prove that the non-racial

factor on which it relies would in fact

account for the proven disparities. Patton

v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463 (1947).

Respondents made no effort to meet that

burden, but merely offered speculation

that the salary disparities might have had

a legitimate non-racial cause.

21

H I . An employer cannot escape its

responsibilities under Title VII by

delegating employment decisions to a third

party. Arizona Governing Board v. Norris,

403 U.S. 1073 (1983). In this case NCAES

has never promoted a black to the position

of a county chairman if a white male also

applied for the vacancy. The court of

appeals erred in holding that this

practice could be defended by evidence

that NCAES frequently permitted county

officials to decide whom NCAES would

promote.

IV. Prior to 1965 NCAES established

a de jure system of separate black and

white 4-H and extension homemaker clubs.

In 1 965 NCAES adopted a freedom of choice

plan that failed; the number of single

race clubs today is virtually the same as

it was 20 years ago. Respondents' failure

to disestablish this dual system violates

22

the applicable federal regulations. 7

C.F.R. § 15.3 (b)(6)(i). Petitioners also

offered substantial evidence indicating

that members of these clubs continue to be

recruited on a racial basis. The lower

courts erred in failing to resolve the

latter claim.

V. The fourth circuit held that

class certification was inappropriate

because petitioners had not demonstrated

that the proposed class was injured by any

"legally cognizable wrong." There were of

course statewide NCAES practices of which

petitioners complained; the fourth

circuit, holding that those practices were

lawful, concluded that the case thus

presented no "legally cognizable wrongs."

The court of appeals erred in basing

certification on its view of the merits

of the claims involved. Eisen v. Carlisle

& Jacquelin, 417 U.S. 156 (1974).

23

The district court believed that

class certification was impermissible

because the United States had filed a

pattern and practice action raising

similar issues. That decision was

inconsistent with the intent of Congress

to provide overlapping private and

governmental remedies for violations of

Title VII. General Telephone Co, v. EEOC,

446 U.S. 318 (1980).

ARGUMENT

I. TITLE VII AND THE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT PROHIBIT A PUBLIC

EMPLOYER FROM APPLYING, AS WELL

AS ESTABLISHING, A RACIALLY

BASED SALARY SYSTEM

Both courts below found that the wage

rates of blacks hired prior to 1965 had

for racial reasons been set at levels

lower than the salaries of comparable

whites, and that these racially based wage

disparities continued until at least the

24

mid- 1 970's. (See pp. 6-7, supra) . The

court of appeals, however, held that only

the establishment of such a racially

tainted wage system, but not the actual

utilization of that system, constituted

discrimination. (Pet. App. 380a-82a)

Because the base wages of petitioners such

as Bazemore were established prior to

1 965, while the instant action was only

commenced in 1971, the fourth circuit

reasoned that NCAES was entitled to

continue indefinitely paying petitioners

lower salaries than the wages paid to

their comparable white colleagues. The

court of appeals believed that this result

was compelled by this Court's decisions in

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324

(1977) and United Airlines v. Evans, 431

U.S. 533 (1977). The fourth circuit's

decision conflicted with the opinions of

seven other circuits, which have held that

25

salary d iscrimination is a continuing

violation of Title VII. See cases cited,

Petition, pp. 17-22.

(1) Salary Discrimination Is A

Contming Violation of the

Equal Pay Act

The question of whether salary

discrimination constitutes a continuing

violation of Title VII is, we urge,

controlled by this Court's construction of

the related provisions of the Equal Pay

Act of 1963. In Corning Glass Works v.

Brennan, 417 U.S. 188 (1974) this Court

held that salary discrimination is a

continuing violation of the Equal Pay Act,

and that that Act thus forbids an employer

to continue to use discriminatory pre-Act

salary scales. In Corning Glass male

workers hired prior to 1964 had been given

higher base salaries than women doing the

same work. The Court explained:

26

The differential -- reflected a job

market in which Corning could pay

women less than men for the same work.

That the company took advantage of

such a situation may be understandable

as a matter of economics, but its

differential nevertheless became

illegal once Congress enacted into law

the principle of equal pay for equal

work.

23417 U.S. at 205. (Emphasis added). The

decision in Corning Glass is, for several

reasons dispositive of the same issue

under Title VII.

First, in County of Washington v.

Gunther, 452 U.S. 161 (1981), every member

of this Court agreed that the substantive

standards of the Equal Pay Act should

apply to an action under Title VII

alleging a denial of equal compensation

See also id. at 208 ("If ... the work

performed by women on the day shift was

equal to that performed by men on the

night shift, the company became obligated

to pay the women the same base wage as

their male counterparts on the effective

date of the Act.")(Emphasis added)

27

for equal work. The Equal Pay Act,

adopted in 1963, requires covered em

ployers to give women the same salaries

paid to men doing the same work. 29 U.S.C.

§206 (d ) ( 1 ) . The Equal Pay Act authorizes

an employer to utilize certain salary

differentials, and the Bennett Amendment

to Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h),

extends that authorization to Title VII

claims of salary discrimination against

women. Although the Court in Gunther was

sharply divided as to the meaning of the

Bennett Amendment, both the majority

24 25

opinion and the dissenters agreed that the

substantive standards of the Equal Pay Act

would be applied to an equal-pay-for-

equal-work claim under Title VII. Both

452 U.S. at 175 ("The Bennett Amendment

clarified that the standards of the Equal

Pay Act would govern ... Title VII ....").

25 452 U.S. at 190, 191-2, 200-01.

28

opinions emphasized that Senator Clark,

the floor manager of Title VII, had

explained to his colleagues that "[t]he

standards in the Equal Pay Act for

determining discrimination as to wages, of

course, are applicable to the comparable

26

situation under Title VII" If, as this

Court has already held in Corning Glass,

the use of discriminatory pre-Act base

wages violates the Equal Pay Act, the

continued use of such base wages is also

a violation of Title VII.

Second, if salary discrimination were

treated as a continuing violation of the

Equal Pay Act, but not of Title VII, a

number of anomalies would result. if,

prior to 1963, a white woman and a black

man were both being paid less than a white

452 U.S. at 172 n.12 (majority opinion),

192 (dissenting opinion). The quoted

statement appears at 110 Cong. Rec. 7217

( 1 964) .

26

29

man doing the same work, Corning Glass

gives the woman a right to have her salary

raised to the level of the white man,

whereas under the fourth circuit decision

the black man could be paid an inferior

salary for the rest of his life. Simi

larly, although under the Equal Pay Act a

female worker can challenge at any time

a discriminatory pay differential estab

lished after 1965, a black worker, under

the fourth circuit decision, must file an

EEOC charge within 180 days of the

creation of that differential, or be

forever barred from redressing that

discrimination. Nothing in the legislative

history of Title VII suggests that

Congress could have intended to thus

provide blacks with more limited protec

tions against salary discrimination than

was already enjoyed by women under the

Equal Pay Act. Those members of Congress

30

who successfully urged that Title VII

extend to sex discrimination expressly

disavowed any intention to confer upon

women any greater rights or remedies than

27would be enjoyed by blacks.

Third, the decision in Corning Glass

accurately reflects the ongoing nature of

salary determinations, and thus of salary

discrimination. Hiring and promotion

decisions may often be discreet, isolated

and generally final actions, but the

salaries paid to particular individuals,

and for specific jobs, are ordinarily

under continuous, or at least repeated,

review. The legislative history of the

Equal Pay Act highlighted the systematic

manner in which American industry fixes

27 '110 Cong. Rec. 2581 (Rep. St. George)

(Women "do not want special privileges);

2583 (Rep. Kelly) (urging that "all

persons, men and women, possess the same

rights"); 2584 (Rep. Watson) ("equal

rights for all people").

31

the salaries for positions and individ

uals, generally focusing on four specific

factors, skill, effort, responsibility

and working conditions. Corning Glass

Works v. Brennan, 417 U.S. at 199-202.

Where an employer had for racial or sexist

reasons set an inappropriately low salary

for an individual or position, application

of these "well defined and well-accepted"

industry principles should ordinarily lead

to a correction of that discrimination.

417 U.S. at 201. Congress understandably

regarded as culpable an employer that,

ignoring the generally accepted practice

of job evaluation, persisted in applying

pre-Act salary differentials rooted in

discrimination. That culpability is the

same whether the discrimination at issue

was on the basis of sex or of race.

32

(2) Neither Teamsters nor Evans

Support the Decision Below

Teamsters and Evans provide no basis

for the decision of the fourth circuit.

Both courts below found that NCAES was

knowingly paying black workers less than

white workers doing precisely the same

job, relying on racially discriminatory

base wage rates established prior to the

effective date of Title VII. Such a

practice clearly falls within the literal

language of Title VII, which forbids an

employer "to discriminate against an

individual with respect to his compensa

tion ... because of such individual's

race." 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a). Teamsters

v. United States expressly held that as a

general matter Title VII forbids the

utilization of practices which operate to

perpetuate the effects of pre-Act dis

crimination:

- 33

Congress "procsribe[d] .. practices

that are fair in form, but discrimi

natory in operation" ... One kind of

practice "fair in form, but discrimi

natory in operation" is that which

perpetuates the effects of prior

discrimination. As the Court held in

Griggs [v. Duke Power Co]: "Under the

Act, practices ... neutral on their

face, and even neutral in terms of

intent, cannot be maintained if they

operate to 'freeze' the status quo of

prior discriminatory practices." 431

U.S. at 349.

The continued use of a racially explicit

base wage has precisely such a forbidden

consequence.

In Teamsters this Court held that the

use of a seniority system that perpetuated

the effects of past discrimination would

have violated Title VII "[w]ere it not for

§ 703(h)." 431 U.S. at 350. Both Team

sters and Evans relied on the terms of

section 7 0 3 (h) , which expressly permits

the utilization of a bona fide seniority

system " [n]otwithstanding any other

provision of [Title VII]. It was because

34

of just such a bona fide seniority system

that blacks had been denied the promotions

sought in Teamsters, and that the plain

tiff had been denied the additional wages

sought in Evans. In rejecting the

seniority-related claims in those cases,

the Court described section 703(h) as

conferring "immunity" on bona fide

seniority systems, 431 U.S. at 350, a term

which made clear that section 703(h)

created an exception to the general Title

VII prohibition against practices perpet

uating the effects of earlier discrimi

nation. The result in Teamsters and Evans

thus turned on the particular favored

treatment for seniority systems that was

demanded during the debates on Title VII

and that was embodied in the language of

section 703(h) .

35

Nothing in the terms or legislative

history of Title VII reflects any compar

able desire to immunize racially motivated

pre-Act salary systems or base wages,

should those systems or wages continued to

be utilized after the effective date of

Title VII. If an employer, prior to

28

1965, had been paying blacks less than

whites for doing identical work, the

literal language of the statute required

that those salaries be adjusted to the

same level when Title VII became effective

on July 1, 1965. The proponents of Title

VII noted with grave concern the different

Since this is an action against a state

agency, the relevant effective date of

Title VII is March 24 , 1972 , the effective

date of the1972 amendments extending the

coverage of that statute to state and

local governments. The fourth circuit

assumed, as do we, that the issue in this

case, whether pre-1972 state salary

systems are actionable under Title VII,

turns on whether Title VII, as originally

enacted, required alteration of pre-Act

private employer salary differentials.

36

median salaries of blacks and whites,

emphasizing that this disparity placed "an

entire segment of our society ... into a

29

condition of marginal existence." Aware,

as they were, that blacks were being paid

less than whites for performing the same

jobs, it is inconceivable that the

Congress which adopted Title VII intended

to freeze an entire generation of blacks

into that position of inequality, or to

provide equal pay for equal work only for

blacks whose base salaries were estab

lished after July 1, 1965.

The decision of the fourth circuit

entails consequences inconsistent in a

variety of ways with other aspects of

Title VII. Title VII forbids an employer

to intentionally assign a lower wage to a

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.,

pt . 2, 28 (additional views of Reps.

McCulloch, et al.)(1964)

29

- 37

particular position because most or all of

the employees in that position are black

or female. See County of Washington v.

Gunther, 452 U.S. 161 (1981). But such

discriminatory wage systems ordinarily

were established, as was the case in

30

Gunther, long prior to the adoption of

Title VII or the beginning of the limita

tions period that would be relevant to a

31

const itut ional claim. If , as the fourth

circuit has held, only the creation of

such discriminatory wage scales, but not

their application, is unlawful, then

30 The existence of separate position for

female prison guards dated from prior to

1955. See note at Ore. Rev. Stat. §

137.350.

31 .See, e.g. Norman v . Missouri Pacific

Railroad, 414 F.2d 73, 84-85 (8th Cir.

1969) (system established in 1930’s);

Laffey v . Northwest Airlines, Inc., 567

F.2d 429, 437-38 (D.C.~Cir. 1978) (system

established in 1947) .

38

Gunther and the principle it establishes

would be a dead letter.

The decision below would also

emasculate the statutory and constitu

tional prohibitions against racial

discrimination in the fixing of salaries

for particular employees. Unlike discrim

ination in promotions or assignments, the

effects of which are often obvious to all

involved, the existence of discrimination

in compensation is only rarely apparent,

since the victims of that practice

usually do not know the salaries of their

white colleagues, and ordinarily have no

method of comparing their wages with those

of others doing the same work. in a

substantial proportion of all reported

32

Title VII wage compensation cases, the

plaintiffs were not able to detect that

32 See cases cited, Petition, pp. 17-22.

39

statutory violation until long after the

deadline for filing a charge with regard

to the intial act establishing their

salaries„

The decision of the fourth circuit

affords to salary scales a degree of

protection far greater than that which

Title VII provides even for seniority

systems. To justify salary disparities

under section 703(h), a defendant must

prove both that those disparities were the

result of seniority system, and that the

system itself was bona fide; if defendant

failed to establish that both the creation

and maintenance of a seniority system were

untainted by a discriminatory purpose, the

affirmative defense authorized by section

703(h) would be unavailable. The fourth

circuit decision regarding salaries would

create a far more sweeping defense,

holding that wage disparities caused by

40

pre-Act salary scales are unlawful regard

less of whether those scales were in fact

racially motivated. Thus pre-Act salary

scales would enjoy a far greater degree of

protection than pre-Act seniority systems,

even though only seniority systems are

afforded any degree of immunity under the

actual language of Title VII. There is no

reason to believe that the framers of

Title VII intended any such incongruous

result.

(3) Salary Discrimination Is a

Continuing Violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment

The fourth circuit rejected without

explanation petitioners' claim that the

utilization of racially tainted base wages

violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

Although those wage scales pre-dated Title

VII and thus were not when established

violative of that statute, those scales

41

were at all times unconstitutional under

the Fourteenth Amendment. Even Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U .S . 53 7 (1895), condemned

such unequal treatment, and the fourth

circuit itself expressly forbade salary

discrimination by state agencies as early

as 1940. Alston v. School Board of

Norfolk, 112 F . 2d 992 (4th Cir. 1940),

cert, denied 311 U.S. 693 ( 1940). The

disposition of petitioners' constitutional

claim is necessary since, if sustained,

that claim would entitle them to back pay

for a period commencing in 1968, whereas

the back pay period for their Title VII

claim begins March 14, 1972, the effec

tive date of the 1972 amendments.

Corning Glass recognized that the use

of discriminatory base wages constituted a

present violation of the Equal Pay Act

because it "operated to perpetuate the

effects of the company's prior illegal

42

practice of paying women less than men for

equal work." 417 U.S. at 209-10 . For

over a century, and in a variety of

circumstances, this Court has condemned as

unconstitutional actions which perpetuate

the effect of prior intentional racial

33

discrimination. See "Perpetuation of Past

Discrimination", 96 Harv, h. Rev. 828

(1983). Although an equal protection claim

requires proof of a discriminatory motive,

it is not necessary that that motive and

the injury complained of be contemporane

ous, so long as the injury can be

"ultimately ... traced to a racially

discriminatory purpose." Washington v.

Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 240 ( 1976). The most

egregious devices that perpetuated past

_

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ., 402 U.S. 1, 21 (1971); Green v.

County School Bd. , 391 U.S. 430 , 438

(1968); Griffin v. County School Bd., 377

U.S. 218, 232 (196471 STrauder v. West

Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 306 (1880).

43

discrimination were the infamous grand

father clauses, which based a citizen's

right to vote on whether his or her

ancestors had been eligible to vote prior

to the adoption of the Fifteenth Amend

ment. This Court struck down those

clauses because they made racial criteria

in effect before the Civil War "the

controlling and dominant test of the right

of suffrage" more than half a century

later. Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S.

347, 364-65 (1915).

In the instant case NCAES' racially

explicit pre-1965 salary decisions were

literally "the controlling and dominant

test" for ascertaining what salary

pe-titioners would be paid in the years

that followed. If the North Carolina

legislature had in 1964 fixed petitioner

Bazemore's salary by statute, intention

ally setting it at a lower level because

44

of his race, this Court would not hesitate

to declare unconstitutional the continued

enforcement of such a law. Surely the

result is no different where, as here, the

racially motivated state practice com

plained of was taken pursuant to an

administrative decision rather than a

state statute. Similarly, if a state

agency in 1900 had established salary

scales for specific jobs based on the race

of the employees holding those positions,

the fourth circuit would hold that that

decision was only actionable at the

beginning of the century; the applicable

limitations period, on this view, would

expire decades before present black

employees were hired or even born. Such a

construction of the Fourteenth Amendment

would read into the Constitution itself

the very evil condemned in the grandfather

clause cases.

45

The factual findings of the courts

below that racially motivated pre-1965

salary disparities continued until at

least the mid 1970 ' s thus compels the

conclusion that respondents violated both

Title VII and the Fourteenth Amendment,,

The burden is on the respondents to

establish the date on which the continuing

effects of those salary disparities

finally ended. This claim should be

remanded to the trial court for appro

priate proceedings to determine the amount

of back pay awarded, and to fashion any

necessary injunctive relief.

II. PETITIONERS ESTABLISHED THE

EXISTENCE OF POST-1965 INTEN-

TIONAL SALARY DISCRIMINATION

Petitioners claimed and sought to

prove at trial that the practice of

intentional salary discrimination did not

end in 1965, but continued for more than a

46

decade thereafter. Petitioners offered

undisputed evidence that, even among

individuals hired after 1965, the average

salary of black workers was consistently

lower than the average salary of whites

holdng the same position and with the same

education and tenure. (See pp.9-13,

supra).

Both courts below, however, regarded

this evidence as fatally defective. (Pet.

App. 141a, 389a-91 a) Neither the district

judge nor a majority of the fourth

circuit panel thought it particularly

surprising or significant that for years

blacks had been paid less than whites for

doing the same job. Even though peti

tioners had shown a substantial and

persistent disparity in the wages paid to

blacks and whites in the same job, the

courts below held that petitioners were

legally obligated to demonstrate that

47

there was no possible legitimate explana

tion for those disparities. Respondents

never offered any evidence demonstrating

that consideration of additional variables

would in fact have eliminated the apparent

salary d isparities, and both courts below

held that such evidence was entirely

unnecessary. The court of appeals and

district court relied on somewhat differ

ent lines of reasoning in reaching this

conclusion.

( 1 ) Petitioners' Statistics Estab-

lished A Prima Facie Case of

Discrimination

The fourth circuit concluded that the

statistical analyses offered by peti

tioners were entirely "unacceptable as

evidence of discrimination" (Pet. App.

391). Evidence that whites make more than

blacks for doing the same job, the

appellate court insisted, is entitled to

48

no weight whatsoever as proof of salary

discrimination. On the court of appeals'

view, the statistics in this case did not

even meet the minimal standard necessary

to establish a prima facie case, and the

defendants were thus under no obligation

to offer any defense at all to that

evidence. Unless a plaintiff demonstrated

that no conceivable additional factor

could explain away a statistical dispar-

ity, the court of appeals held that

evidence that blacks are paid, hired , or

promoted or given raises less often than

whites would be devoid of weight or

34

significance.

34 The majority opinion rejected the individ

ual claims of salary discrimination on a

similar theory. Petitioners offered

statistical comparisons of their wages

with the wages of white agents with the

same education tenure, job title and

county. The majority dismissed that

evidence on the ground that such compari

sons did not also consider possible

additional job qualifications or differ

ences in job performance. (Pet. App.

49

The Court has repeatedly rejected

similar arguments that statistical

evidence must be absolutely conclusive in

order to be probative. In Dothard v.

Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 ( 1977), the

plaintiffs relied on population statistics

to show that an employer's hiring criteria

had an adverse impact on women. The

defendant argued that the plaintiffs

should have been required to demonstrate

the impact of those criteria on actual

applicants. This Court disagreed,

explaining, "The plaintiffs in a case such

as this are not required to exhaust every

378a, 379a). Both the majority and Judge

Phillips agreed that the district court's

decision rejecting the individual claims

would have to be reversed if there was

proof of a pattern and practice of salary

discrimination. (Pet. App. 380a, 467a).

The district court acknowledged that its

disposition of the individual claims

turned on its view that there was no

systematic salary discrimination. Pet.

App. 218a n.70 [sic.]

50

possible source of evidence." 431 U.S. at

331. In Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 321 (1977), the employers objected in

a similar way to evidence that it employed

a far smaller proportion of minorities

than were present in the population. The

employer insisted that half a dozen

factors not considered in the plaintiff's

analysis might have explained away that

disparity, and presented an expert on

statistics to criticize the plaintiff's

35

methodology. But this Court held that the

plaintiff itself was under no obligation

to "fine tun[e]" its statistics. 431 U.S.

at 342 n. 23. See also Neal v. Delaware,

103 U.S. 370, 395 (1890).

In a case such as this in which

petitioners allege they are not being

given equal pay for equal work, the

See Brief for Petitioner T .I.M .E.-D.C.,

Inc., pp. 18-20 .

51

allocation of the burden of proof should

be the same as is applied under the Equal

Pay Act. In an Equal Pay Act case, once a

plaintiff has met her burden of "showing

that the employer pays workers of one sex

more than workers of the opposite sex for

equal work, the burden shifts to the

employer to show that the differential is

justified". Corning Glass Works v,

Brennan, 417 U.S. 188, 197 ( 1974). A

demonstrable disparity in the average

salary paid women and men in the same job

would be sufficient to satisfy a plain

tiff's burden under Corning Glass. Since

the substantive standard of the Equal Pay

Act and Title VII are the same in an

equal-pay-for-equal-work case, that same

evidence, adduced here to demonstrate the

existence of racial discrimination, was

also sufficient to meet plaintiffs'

burden.

52

The same standard is entirely

appropriate in a Title VII case. Here, as

in Teamsters "it is ordinarily to be

expected that nond iscriminatory" salary

policies will result in comparable

salaries for blacks and whites whom an

employer itself has classified in the same

position. 431 U.S. at 339 n. 20. The

legislative history of Title VII, more

over, demonstrates, that the Congress

adopted that measure because it believed

the existence of nationwide racial

discrimination was established by statis

tics demonstrating substantial differences

in the median salaries of black and white

36

workers.

The court of appeals apparently

believed that statistics could be treated

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.,

pt. 2, 28 (additional views of Reps.

McCulloch, et al.) (1964).

53

as reliable evidence only if the analysis

was so refined as to rule out any plaus

ible non-racial explanation for a demon

strated disparity. But statistical

evidence need not be conclusive in order

to be admissible or relevant,* rather,

statistical evidence, like other types of

proof, need only have a "tendency to make

the existence of [discrimination] ... more

likely...." Fed. Rules of Ev., Rule 401.

Statistical evidence which meets that

standard is not, unless unrebutted,

dispositive by itself of the litigation;

such evidence merely shifts to the

defendant the burden of adducing evidence

that the disparity was caused by the

application of a legitimate non-discrimi-

natory criterion. Cf. Texas Department of

54

community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S.

248, 254 (1981); Vulcan Society v. Civil

Service Comm'n , 490 F .2d 387, 392 (2d Cir.

1973).

In order to provide probative

statistical evidence that a challenged

selection procedure is being applied in a

discriminatory manner, a plaintiff must

(a) identify the procedure in dispute, (b)

identify the group of applicants or

employees to whom that procedure is

37

applied, and (c) demonstrate a disparity

In a case where a plaintiff challenges

only a selection procedure for hiring or

promotions, the appropriate universe for

comparison purposes is the group of

applicants. Because applicant flow data

is often unavailable or unreliable, the

courts have properly accepted workforce

statistics as evidence of the composition

of the applicant group. See, e.g.,

Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 337 n.7. In an

action regarding internal promotions, the

relevant workforce, of course, is the

group of employees eligible for promotion.

Paxton v. Union National Bank, 688 F.2d

552, 564 (8th Cir” 1982) Where a plain

tiff alleges that applicant flow is

tainted by racial discrimination, the

55

between the racial composition of that

initial group and the group ultimately

selected, e . g . , for hiring, promotions,

cases, or jury service. The appropriate

degree of statistical refinement will thus

turn on the specific nature of a plain

tiff's claims. Where a defendant's

selection process involves a number of

different factors or procedures, a

plaintiff may either challenge the process

as a whole, as occurred in this case, or

focus his or her objection on only a

specific aspect of that process. Connec

ticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440 (1982).

I n Hazelwood School District v.

United States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977), the

government alleged there was intentional

discrimination in the manner in which

composition of the applicant group should

be compared with that of the relevant

workforce.

56

Hazelwood selected new teachers from the

area pool of teachers. Because the United

States did not attack Hazelwood's practice

of considering only trained educators, it

was that pool of trained educators, rather

than the entire population, whose composi

tion was compared with Hazelwood's hiring

rate. 433 U.S. at 308-312. In Mayor v.

Educational Equality League, 415 U.S. 605

(1974), where the plaintiffs alleged

intentional discrimination in the selec

tion of members of an Educational Nominat

ing Panel, the city charter required the

mayor to chose most of those members from

among individuals who headed certain

public and civic organizations. The

plaintiffs did not attack the legality or

legitimacy of this city charter require

ment 415 U.S. at 620. Under those

circumstances the Court held that "the

relevant universe for comparison purposes

57

consists of the highest ranking officers

of organizations and institutions speci

fied in the city charter,, not the popula

tion at large," 415 CJ.S. at 620-21 . An

asserted qualification requirement may be

used to narrow the universe for comparison

only if a plaintiff challenges neither the

legitimacy of that requirement nor the

manner in which it was applied. As a

practical matter it will at times be

difficult to calculate a universe of

comparison which matches exactly the group

to which a challenged procedure applies.

Evidence regarding the composition of that

group need not be conclusive; a defendant

is free to offer more refined data which

it believes better approximates the

composition at that group.

Neither Hazelwood nor Educational

Equality League, however, suggested that

the plaintiffs in such cases were obli-

58

gated to buttress such statistics with

evidence foreclosing the possibility that

potential black appointees were less

qualified than the whites selected. In

Neal v. Delaware the lower court had

assumed, in the absence of evidence to the

contrary, that "the great body of black

men residing in th[e] state are utterly

unqualified by want of intelligence, ex

perience or moral integrity, to sit on

juries" 103 U.S. at 394. This Court

refused to indulge in any such "violent

assumption." 103 U.S. at 397. Neal

forbade federal as well as state courts

from requiring a plaintiff, as part of his

or her statistical analysis, to overcome

any presumption that blacks are ordinarily

less skilled and capable than whites. Both

Title VII and the Fourteenth Amendment

forbid a public agency to rely on any such

assumption in making employment decisions;

59

surely it is equally improper for a

federal court, in resolving an employment

discrimination claim, to rely on that very

impermissible assumption of racial

38

differences.

In the instant case the challenged

practice was the fixing of initial

salaries and raises for employees holding

the same position. Accordingly, the

"relevant universe for comparison pur

poses" was all employees in the same job.

The average salaries of black and white

workers represented the cumulative effect

of such disputed salary decisions regard

ing each of those employees. The result

ing statistical analyses were as complete

as those deemed acceptable in Teamsters,

— — ____ — ------- ----------38 The district judge’s decision in the

instant case relies in part on precisely

such an assumption, arguing at length it

was "common knowledge" that black college

graduates were in general less educated

than whites. (Pet. App. 196a-98a).

60

Hazelwood and Educational Equality League,

and were clearly sufficient to establish a

prixna facie case of salary discrimination.

(2) Respondents Failed to Rebut That

Prima Facie Case~

The district court acknowledged that

petitioners' statistical evidence was both

probative and sufficient to create a prima

facie case, but held that that evidence

had been rebutted by respondents. (Pet.

App. 130a-31a, 149a-50a) Respondents,

however, did not offer statistical

evidence demonstrating that the proven

disparities were the result of racially

neutral job related criteria for fixing or

raising salaries. On the contrary, the

statistics offered by respondents revealed

essentially the same disparities proven by

petitioners. The "defense" accepted by

the trial court consisted merely of

testimony that there were 9 nonracial

61

factors which had not been included in the

statistical analyses offered by either

party. (Pet. App. 133a-36a) Respondents

did not offer, and the trial court

regarded as entirely unnecessary, evidence

that inclusion of these additional

variables would _in fact have eliminated

the apparent disparities. On the trial

court's view a defendant could conclu

sively rebut significant statistical

evidence of racial disparities simply by

offering speculation that the inclusion of

other variables might have yielded a

different result.

This Court has repeatedly held that

such unsubstantiated speculation is

entitled to no weight in rebutting a prima

facie case of discrimination. in Patton

v. Mississippi, 332 U.S. 463 (1947), the

state suggested that the paucity of black

jurors might have been due to a lack of

62

qualifications among black citizens. This

Court observed " [ I j f it can possibly be

conceived that all of them were disquali

fied for jury service we do not doubt

that the State could have proved it." 332

U.S. at 469. (Emphasis added) The

state's mere speculation that blacks were

unqualified "wholly failed to meet" the

statistical evidence offered by Patton.

Id. In pothard v. Rawlinson this Court

again held that a defendant had to do more

in response to such statistical evidence

than merely hypothesize the existence of

possible explanations. "If the employer

discerns fallacies or deficiencies in the

data offered by the plaintiff, he is free

to adduce countervailing evidence of his

own. In this case no such effort was

made." 433 U.S. at 331. These decisions

make clear that a defendant who wishes to

rebut a prima facie case must offer

63

substantial evidence, not merely "an

ingenious academic exercise in the

conceivable." United States v. SCRAP,412

U.S. 669, 688 (1973).

As Judge Phillips emphasized in his

dissenting opinion in this case, the

effective use of statistical evidence in a

discrimination case would be impossible if

such evidence could be rebutted merely by

testimony that the statistical analysis

did not

include a number of other independent

variables merely hypothesized by

defendants .... [T]o apply such a

rule generally would effectively

destroy the ability to establish any

Title VII pattern or practice claim

by this means of proof. [I]t will

always be possible for Title VII

defendants to hypothesize yet another

variable that might theoretically

reduce a race-effect coefficient

demonstrated by any multiple re

gression analysis that could-be con

ceived. (Pet. App. 448a-49a). 9

Other lower courts have recognized that

plaintiffs could never meet the onerous

burden established by the opinion below.

See, e.g., Guardians Association v. Civil

Service Commission, 630 F.2d 79, 88 n .7

64

Judge Phillips stressed, as did this Court

in Dothard, that there was no "evidence

that the inclusion of other variables

would in fact reduce" the disparities in

the wages of blacks and whites in the

same. (Pet. App. 450a) (Emphasis in

original).

Lower courts, all too familiar with

the speculative ingenuity of Title VII

defendants, have consistently and properly

refused to accept such speculation as an

adequate response to statistical evidence.

[U] nquantified, speculative and

theoretical objections to the prof

fered statistics are properly given

little weight by the trial court:

"When a plaintiff submits accurate

statistical data, and a defendant

alleges that relevant variables are

excluded, defendants may not rely on

hypothesis to lessen the probative

value of plaintiff's statistical

proof. Rather, defendant . . . must

either rework plaintiff's statistics

(2d Cir. 1980).

65

incorporating the omitted factors or

present other proof undermining plaintiff s claims."

Trout v. Lehman, 702 F.2d 1044, 1102 (D.C.

Cir. 1 983 ), vacated on other grounds sub

nom. Lehman v. Trout, 79 L.Ed.2d 732

(1984). These decisions reflect the fact

that ordinarily only an employer knows

what non-racial factors, if any, might

have been the reasons for its actions, and

only that employer has control of the

evidence which would tend to substantiate

or undermine that defense.

The danger of accepting such a

speculation defense is well illustrated by

the facts of this case. The fourth

Circuit concluded there was no salary

discrimination primarily because that

court thought that black employees might

have been earning less simply because they

were concentrated in the counties in

66

western North Carolina that paid all their

employees below average salaries. (Pet.

App. 388a) But the district court found

that blacks were in fact concentrated in

the higher salaried counties in the

eastern portion of the state. (J. App.

77; Pet. App. 48a, 110a; see C.A. 1612—

15). Similarly, although the district

court thought it possible that the salary

disparities might have been caused by

differences in performance ratings, the

defendants own analysis showed that in

1975 the lower paid blacks had actually

received higher ratings than their better

paid white colleagues. (See n.12, supra).

To overcome the presumption created

by a prima facie case, a defendant "must

clearly set forth, through the introduc

tion of admissible evidence, the reasons

40

for" the disputed action. Texas Dept, of

40 A defendant may also attack the accuracy

67

Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S.

248, 255 (1981). Where that explanation

is based on the utilization by the

employer of one or more selection cri

teria, the criteria must, of course, be

job-related. Griggs v, Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971). Evidence that a

defendant utilizes one or more legitimate

non-discriminatory criteria is not by

itself sufficient; those asserted criteria

could not be the "reasons for" a disputed

action unless the application of those

criteria would in fact have produced the

of the raw data utilized by plaintiffs, or

object on technical statistical grounds to

the method by which plaintiffs analysed

that data. But the mere existence of

minor inaccuracies or technical flaws will

not dispel the evidentiary value of

statistics unless there is substantial

reason to believe that the elimination of

those alleged errors would have fundament

ally altered the outcome of the analysis.

Craik v. Minnesota State University

Bd. ,731 F ̂ 2d 465, ~477 n.5 (8th Cir7

T984) .

68

result of wh ich a plaintiff complains.

Thus, although an employer does not bear

the burden of proving what its actual

motive was, the employer's proposed

explanation simply is not an explanation

of all unless the employer demonstrates

that its asserted motive, if present,

would have led to the employment action at

issue. Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346,

361 (1 9 7 0).

In an individual action, for example,

a salary disparity could not be rebutted

merely by evidence that an employer had a

job-related policy of paying higher

salaries to workers with Ph.D.'s; the

employer would also have to show, of

course, that the black complainant

actually lacked a Ph.D. , and that applica-

tion of the Ph.D. rule could thus explain

69

his particular salary level. Similarly,

in response to evidence of systematic

salary discrimination, an employer does

not offer evidence of the "reason for" a

disparity merely by proving it uses some

non-racial criteria to fix salaries; the

41

employer must also show, by statistical or

other methods, that application of those

racially neutral criteria to the work

force in question would yield, and thus

tend to explain, the salary patterns of

which a plaintiff complains.

In the instance case the respondents

did not meet, or even attempt to meet,

this standard. A defense witness did

41 The lower courts have generally regarded

such more refined statistics as the most

appropriate and reliable form of rebuttal

evidence. Movement for Opportunity v.

General Motors , Inc . , 622 F.2d 1235, 1245

(7th Cir.~i9"80) 7 Trout v. Lehman, 702

F.2d at 1102; Falcon v. General Telephone

Co., 628 F.2d 369, 381 (5th Cir. 1980),

rev'd on other grounds, 457 U.S. 147

(1982)

70

identify several non-racial criteria which

respondents asserted affected salaries,

but respondents made no effort to satisfy

its burden of showing that these criteria

were "the reasons for" the apparent salary

disparity, since there was simply no

evidence that an analysis including those

criteria would have explained away the

obvious disparities. The strong prima

facie case of salary discrimination thus

stood essentially unrebutted.

III. TITLE VII AND THE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT PLACE ON PUBLIC

AGENCIES A NON-DELEGABLE DUTY TO

PROMOTE EMPLOYEES IN A NONDIS-

CRIMINATORY MANNER

The evidence of discrimination in

promotion showed, inter alia, that NCAES

never promoted a black into a committee

chairmanship for which a white male had

applied. (See pp.13-17, supra) . The

71

district court concluded that that

evidence "certainly create[d] a prima

facie case of discrimination". (Pet. App.

83a). The district court,, relying on a

somewhat unorthodox form of statistical

42

analysis, held that petitioners had failed