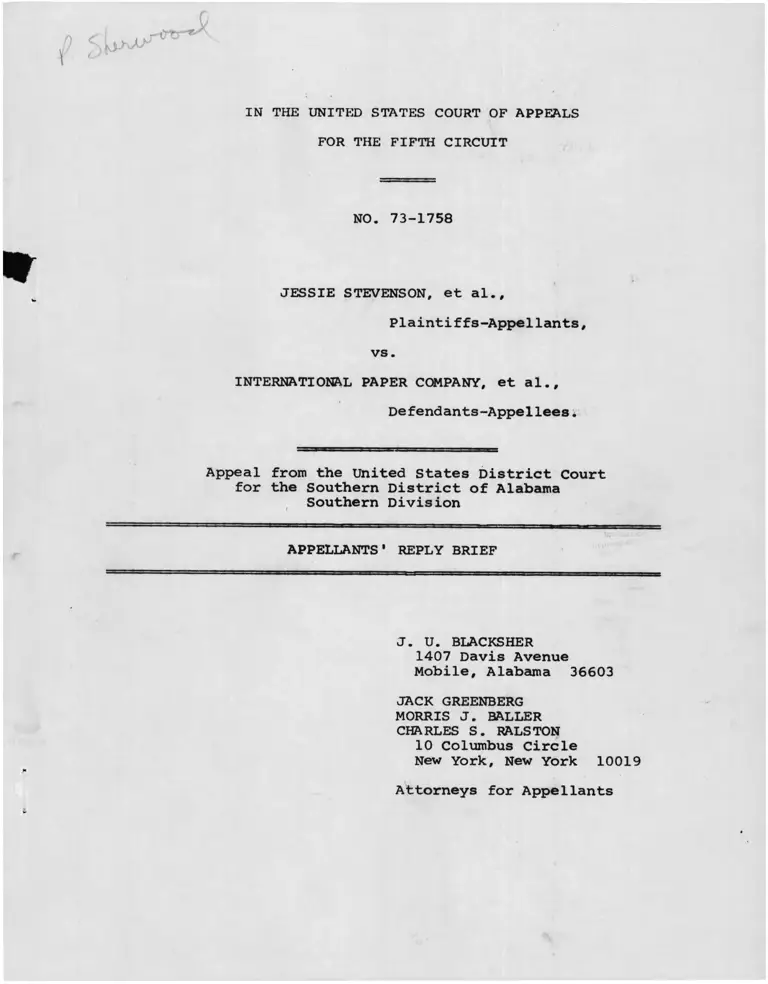

Stevenson v. International Paper Company Appellants' Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

July 11, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stevenson v. International Paper Company Appellants' Reply Brief, 1974. 4f7aa235-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e21f6db0-3904-41f3-a282-2f8a9956720a/stevenson-v-international-paper-company-appellants-reply-brief. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-1758

JESSIE STEVENSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

INTERNATIONAL PAPER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the united States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama

Southern Division

APPELLANTS' REPLY BRIEF

J. U. BLACKSHER 1407 Davis Avenue

Mobile, Alabama 36603

JACK GREENBERG

MORRIS J. BALLER

CHARLES S. RALSTON

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

INDEX

1• IP's Approach To All The Issues in This Case Reflects Two Erroneous Themes Contrary ToBasic Title VII Law................. ... ............... 1

A. The Defenses Based On OFCC Approval Of

Defendants' Discriminatory Practices.............. 2

B. The Defenses Based on the "Evolving"State of Title VII Law............................ 5

11 * Appellees Offer No Persuasive Arguments To Support

The District Court's Decision Holding That The

1968 Jackson Memorandum Cured All Effects of Past Discrimination ....................................... 7

A. Appellees Do Not Seriously Argue That the

1968 Jackson Memorandum Remedied Discrimination Insofar As Possible........................ 9

B. IP's Arguments Fail to Justify the unnecessary

Limitations of the Jackson Memorandum ............ 12

111• The Company's Testing Battery Screens Out Blacks

From Maintenance Positions And Has Not Been Properlv Validated.......................... *-------------- - ^7

A. Evidence of Disparate Impact...................... 17

B. Validation................................. 21

IV* IP's Brief Fails To Rebut Plaintiffs' Showing That

It Unlawfully Excludes Blacks From Maintenance And Supervisory Positions.......... 26

A. Maintenance Positions............................. 26

B. Supervisory Positions............................. 29

Under Recent Controlling Authority The Court MustAward Plaintiffs Class Back Pay........................ 31

VI• The Union's Argument That The District Court Did

Not Erroneously Raise Prior Litigation In Bar To This Action Is Contrary To This Record And To The

Union's Position In Related Litigation......... 33

A. The UPIU Argument Rests on Faulty

Characterizations and Assumptions................. 34

B. The upiu Position Here Contradicts Its

Position In Related Litigation.................... 37

PAGE

x

PAGE

Conclusion 39

Table of Authorities

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 39 L.Ed.2d 147 (1974)..... 3,16

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., __ F.2d

(5th Cir. No. 73-1039, June 6, 1974)........... 7,8,32,33,34nBoles v. Union Camp Corp., 57 F.R.D. 46

(S.D. Ga. 1972)......................................... 3

Buckner v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 339 F. Supp. 1108

(N.D. Ala. 1972) aff'd 476 F.2d 1287 (5th Cir. 1973).... 28

Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 494 F.2d 817

(5th Cir. 1974)......................................... 32

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., __ F.2d

(5th Cir. No. 72-3239, June 3, 1974)........... 7,8, 29, 32,34n

Glover v. St. Louis-San Francisco Rwy. Co.,

393 U.S. 324 (1969)..................................... 16

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).............. 18n

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364

(5th Cir. 1974)........................... 6,7,8,9,14,18n, 29,

31,32,33,3 4n,39Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers

v. united States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied 397 U.S. 919 (1970)............. 3,4,8, 9n, lln, 12n

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534(5th Cir. 1970)......................................... 6

Miller v. Continental Can Co., __ F. Supp. __,

5 EPD f8536 (S.D. Ga. 1973)............................. 3

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134 (4th Cir.

1973), pending on rehearing en banc................... 18n,21

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974)............... 8

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974).............. 4,6, 7,8,9, lln, I2n, 13,14,15n, 16,

28,31,32,32n,33,34nRobinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791(4th Cir. 1971)......................................... 4

Rogers v. International Paper Co. (W.D. Ark.

No. PB-C-71-47)..................................... 37,38,39Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348

(5th Cir. 1972) ........................................ 30

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906

(5th Cir. 1973)................. 7,8,9,18n, 19, 23,24, 26,31, 33nUnited States v. Hayes International Corp.,

456 F. 2d 112 (5th Cir. 1972)............................ 27

ii

PAGE

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971) cert, denied

406 U.S. 906 (1972).................................. 14, 18nUnited States v. Operating Engineers, Local 3,

__ F. Supp. __, 4 EPD 1(7944 (N.D. Cal. 1972)........... . . 4

Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 468 F.2d 1201

(2d Cir. 1972), cert, denied 411 U.S. 931 (1973)......... 4

Other Authorities

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-12(b) ..................................... 4

EEOC Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures,

29 C.F.R. § 1607.3 (b) ................................... 26

EEOC Guidelines, 29 C.F.R. § 1607.4(c)(1) .................. 23

i n

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

)

NO. 73-1758

JESSIE STEVENSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

INTERNATIONAL PAPER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the united States District Court

for the Southern District of Alabama

Southern Division

APPELLANTS’ REPLY BRIEF

Plaintiffs-appellants hereby reply to the briefs filed on

behalf of defendants-appellees international Paper Company (IP) on

June 4, 1974 and United Paperworkers International union (UPIU) on

May 20, 1974. Plaintiffs first address two recurrent themes of the

IP brief which pervade its treatment of all the issues; then plain

tiffs respond with regard to the specific issues raised by this

appeal.

I. IP's Approach To All The issues In This Case Reflects

Two Erroneous Themes Contrary To Basic Title VII Law.

IP's entire brief is shot through with two recurrent themes:

that the federal courts cannot hold IP liable for practices condoned

by a federal administrative agency (OFCC), nor for practices made

illegal by Title VII which had not explicitly been judicially

condemned at the time ip maintained them. Each of these themes

reflects a fundamental misconception of the nature of Title VII

law.

A. The Defenses Based On OFCC Approval Of Defendants* Discriminatory Practices.

Again and again, in support of practices now conceded to be

discriminatory or remedially inadequate, IP interposes the defense

that the OFCC had approved them or failed to recognize the practices

as unlawful.

Thus, IP relies on OFCC approval of the 1968 Jackson Memoran

dum (Br. 11, A. 1527a) and the McCreedy letter policy (Br. 12-14,

54-55). It relies on OFCC*s alleged failure at the Jackson Confer

ence to notice the absolute exclusion of blacks from maintenance

jobs (Br. 29). it notes extensively how pleased OFCC has been with

IP's partial and reluctant reforms (Br. 37 and n.27). It falls back

2/on OFCC's abandonment of its earlier judgment that job skipping was

necessary (Br. 48-49, n.39), and defends the failure to generate

scores permitting validation of its testing program as it was used,

in battery form, on the ground that OFCC had not requested it (Br. 85).

Finally, IP falls back on "authoritative administrative (not judicial]

determinations" of OFCC "under the law" [Executive Order 11246, not

Title VII] as a barrier to back pay (Br. 95-96).

By these arguments, IP in effect urges the judiciary to abdi

cate its Congressionally assigned functions under Title VII. Congress

—^ The "Twelve Points" which OFCC initially demanded that defendants

satisfy at the Jackson Conference included a job skipping provision

(A. 1422a). OFCC may have relied on the promise in the Jackson Memo

randum, never fulfilled, that defendants would establish job skipping and advanced level entry by subsequent negotiations (A. 1522a).

-2-

did not intend federal judges to be mere handmaidens to the admini-

strative officers of the OFCC, or any agency of the executive branch.

On the contrary, as the Supreme Court recently held:

1

. . . final responsibility for enforcement of Title VII

is vested with federal courts .... Courts retain these

broad remedial powers [of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (g)] despite

a [EEOC] Commission finding of no reasonable cause to

believe that the Act has been violated. McDonnell-

Douglas Corp. v. Green, supra, 411 U.S., at 798-799.Taken together, these provisions make plain that federal

courts have been assigned plenary powers to secure compliance with Title VII.

* * *

The purpose and procedures of Title VII indicate that

Congress intended federal courts to exercise final

responsibility for enforcement of Title VII.

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 39 L.Ed.2d 147, 156 (1974).

Employers in this and other industries have frequently raised

OFCC approval as a defense to Title VII proceedings, and the federal

courts have uniformly rejected this defense. in the leading paper

industry case of Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied 397 U.S. 919

(1970), the lower court rejected an OFCC-sponsored "A / B" seniority

remedy as legally inadequate, 416 F.2d at 985, and this Court affirmed.

In Boles v. Union Camp Corp., 57 F.R.D. 46 (S.D. Ga. 1972), the court

held that the defendant paper company was not insulated from attack

under Title VII by an OFCC-approved affirmative action plan settlement

similar to the Jackson Memorandum. Accord, Miller v. Continental Can

Co., ___ F. Supp. ___, 5 EPD f8536 (S.D. Ga. 1973). Most recently,

IT- Indeed, OFCC has no function whatever under Title VII, and only meekly administers the far more limited E.O. 11246. For the judiciary

to relegate Title VII enforcement to administrative proceedings under

different authority would in effect repeal Title VII wherever the

Department of Labor acts first.

-3-

in Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211 (5th Cir.

1974), this Court had no difficulty finding the company's testing

program unlawful even though the responsible OFCC review official

had approved and highly praised the program, 494 F.2d at 219, 221,

n. 21.

The rule that federal administrative determinations do not

bar judicial findings of Title VII liability applies with particular

force to private suits. Even where a federal court has previously

granted partial relief in a Title VII action brought by the Attorney

General, private plaintiffs are not thereby precluded from obtaining

further relief where necessary to vindicate their rights. Williamson

v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 468 F.2d 1201, 1203-1204 (2nd Cir. 1972),

cert, denied 411 U.S. 931 (1973); United States v. Operating Engineers,

Local 3, ___ F. Supp. ___, 4 EPD f7944 (N.D. Cal. 1972). Ipso facto,

private plaintiffs can seek more complete relief than that obtained

by a non-judicial federal agency like OFCC.

Section 713 (b) of Title VII does provide a mechanism for

employers subject to the Act to seek administrative interpretations

on which they may rely, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-12 (b). That procedure is

committed by statute to EEOC, not OFCC, and is narrowly restricted by

appropriate precautions, see Local 189, etc, v. United States, supra,

at 997; Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791, 801 (4th Cir. 1971).

The whole purpose of the narrow and specific statutory provisions is

to preclude the kind of whitewash of discrimination that IP has

attempted to purchase by placating the undemanding minions of the

Department of Labor.

OFCC's failure to seek or require full relief from defendants'

discrimination cannot diminish the court's duty to assure plaintiffs

-4-

their complete remedy,

B. The Defenses Based on the "Evolving" State of Title VII Law.

Apparently conceding that many of its post-1965 practices fall

short of what clear law holds Title VII to require, IP stresses the

"evolutionary nature" of this law (Br. 41-42) as a defense to its

illegal practices. Thus, IP asserts that the 1968 Jackson Memorandum

paralleled then-current remedial decisions (Br. 42-43); that the case-

law which conclusively condemns the inadequate 1968 Memorandum was

not crystallized until after 1971 (Br. 44-46); that whatever the inade

quacies of the $3.00 red circle ceiling and the lack of job skipping,

the state of the law was not clear as to such remedies in 1968-1969

(Br. 47-49); that the principal authorities supporting plaintiffs'

testing argument were decided following trial in this case (Br. 78-79

and n.77); and that it had no way to know that OFCC's advice would

leave IP exposed to back pay liability (Br. 95-96).

These points amount to no more than an artful recasting of the

now-discredited proposition that good faith operates as a defense to

2/

Title VII liability. While judicial decisions clarifying the remedial

requirements of Title VII have certainly crystallized, there has been

no change in pertinent statutory language embodying the original

Congressional intent or in the underlying judicial standards of com

pliance. Title VII today says and means exactly what it has since

July 2, 1965 (insofar as the issues presented here are concerned).

The basis for IP's "judicial evolution" defense is a mistaken

notion that a Congressional enactment becomes meaningful not on its

See cases cited in part V, infra.V

-5-

effective date but only when the federal courts have given it

authoritative interpretation. The law is contrary. As this Court

held with regard to Title II of the 1964 Civil Rights Act,

... the [discriminatory] actions ... became subject to the prescribed judicial relief not because the Court

said so, but rather because the Court said — even

perhaps for the very first time — that the Congress

said so.

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534, 536 (5th Cir.

1970).

This Court has rejected a similar defense in the context of

the class back pay issue, in the strongest possible terms, Johnson

1 7v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974). More

over, the "unsettled law" theory makes even less sense as a defense

to a finding of discrimination and a right to complete injunctive

relief than it does as a back pay bar. In Pettway, supra, this Court

held a testing program validation illegal under Griggs and Georgia

Power even though it long antedated those decisions, 494 F.2d at 221,

W There Goodyear had contended that "it had proceeded at all times subsequent to the Act to remedy its past discriminatory practices,"

491 F.2d at 1376. The Court of Appeals found the contention "totally

irrelevant" as it amounts to nothing but a plea of benign motivation,

id. It concluded,

In sum, we feel that an employer's alleged reliance on

the unsettled character of employment discrimination law

as a defense to back pay is unpersuasive. At least since

July 2, 1965, the effective date of Title VII, the

employers of this nation have been on notice that employment

discrimination based on race, whether overt, covert, simple

or complex, is illegal. In this case, the employer has

been violating the Act as to some employees since that date.

If we were to accept the employer's position the effective

date would be advanced at least to the date of the Griggs

opinion. This result would be untenable and completely at odds with the Congressional purpose evidenced by enacting

Title vil. Title VII is strong medicine and we refuse to

vitiate its potency by glossing it with judicial limita

tions unwarranted by the strong remedial spirit of the

act. 491 F.2d at 1377.

-6-

n.21, and granted back pay as a remedy for the testing discrimination.

Repeating Johnson succinctly, the Court in Pettway held that M[t]he

specific prohibitions of Title VII were adequate notice to employers

post July 2, 1965," ib. at 255. It makes no difference that many of

the judicial clarifications crucial to this case involve the nature

of appropriate remedies. Any employment system that fails to open

up opportunities to blacks formerly barred from them to the greatest

extent practicable, unnecessarily perpetuates past discrimination and

is, therefore, itself discriminatory. (See main Br. at 41-42).

Even if we could accept at face value IP's insistence that it

kept pace with administrative and judicial precedent — and the record

will not support any such assumption — IP's defense would still fail.

Its duty was to cease discrimination and eradicate its lingering

effects — not to imitate any particular directive. ip failed to meet

that basic obligation.

II. Appellees Offer No Persuasive Arguments To Support

The District Court's Decision Holding That The 1968

Jackson Memorandum Cured All Effects of Past Discrimination.

The inconsistent, often contradictory arguments presented by

appellees in the sections of their briefs that defend the 1968 Jackson

Memorandum result from their desperate attempt to avoid the applica

tion of recent on-point caselaw to this action. This Court's recent

landmark Title VII decisions, handed down since trial below, are

dispositive of this issue on appeal. Pettway v. ACIPCO, supra;

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., supra; Franks v. Bowman Trans

portation Co., ___ F.2d ___ (5th Cir. No. 72-3239, June 3, 1974);

Baxter v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., ___ F.2d ___ (5th Cir. No.

73-1039, June 6, 1974); United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d

-7-

906 (5th Cir. 1973). In every one of those cases, this Court reit

erated in strong terms its previous commitment to the governing

principles of the Local 189 line of cases. Simply stated, the Court

insists that in a Title VII industrial case all the effects of past

discrimination against black employees must be eliminated insofar as

possible by granting them full seniority, transfer, and promotion

rights. Pettway, Johnson, and Baxter each involved employers who had

made substantial changes in their discriminatory practices and who

argued these modifications in defense of their cdse. in each instance

this Court, looking to the defendants' failure actually to cure the

continuing racial stratification of their plants, rejected the defense.

See, e.g., Pettway, supra, 494 F.2d at 222-230? Johnson, supra at

1370-1377? Baxter, supra, Slip Op. at 4377-4380.1/IP's brief attempts to distinguish this case from such control

ling authorities on the ground that these defendants instituted a

rudimentary mill seniority system in 1968 (IP Br. 1-4). It would

apparently have this Court hold that its sweeping decisions in Georgia

Power, Pettway, Johnson, and Franks only apply to companies with

departmental seniority systems at time of trial. This approach mis

reads the underlying thrust of Georgia Power and its progeny: we are

confident that this Court intended to put broader handwriting on the

wall for all practitioners of employment discrimination, of whatever

form, in this Circuit. Johnson, supra at 1377? cf. Baxter, supra, and

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974), cases not involving any

seniority system to which the Court has applied a similar remedial

J7~ We deal in reply only with IP's brief on this issue since the

UPIU merely adopts and summarizes the IP's position in conclusory

terms (UPIU Br. 35-41).

-8-

analysis.

In light of the principles of the cases cited above, the 1968

Jackson Memorandum cannot serve as a whitewash of the stains of all

defendants' past discrimination.

A. Appellees Do Not Seriously Argue That the 1968 Jackson

Memorandum Remedied Discrimination Insofar As Possible.

Although IP goes through the motions of defending the suffi

ciency of the 1968 Jackson Memorandum on its merits, its primary

response is a twofold legal smokescreen. IP misses the point when it

argues that defendants' actions and inactions can be justified first

by their alleged good faith reliance on governmental approval, and

additionally by their alleged adherence to developing judicial pre

cedents. See part I, supra. Neither of these defenses goes to the

heart of the question: did the 1968 Jackson Memorandum fail to

eliminate the effects of discrimination insofar as possible?

The "relevant legal standards" (IP Br. 39) by which this

question must be answered are, of course, those now controlling in

this Circuit - the progeny of Georgia Power and most particularlv

1/Pettway.

Thus, while this appeal is obviously not in every factual respect

identical to Johnson or Pettway, it is governed by the same well-

established legal precedents. Plaintiffs here seek no "new standard

for review" (IP Br. 39). Instead, we have merely restated the

settled rule that continued racial segregation and stratification

places upon Title VII defendants the burden of proving that all lin

gering impediments to discriminatees' advancement are required by

IT" There has in truth been no change in Title VII law in this Circuit

since Local 189, but only a progressive clarification of its holding and rationale.

-9-

business necessity (main Br. 44). ip addresses this precise burden

almost parenthetically and with more rhetoric than proof.

Although IP quibbles with the accuracy of plaintiffs' statis

tical proof, it has not denied the continuing racial stratification

of its production LOPs. Rather, IP merely attempts to explain these

a e Ccaufe1ofnS r f o n o S f “ “ trial and int«rogatory exhibits reveals

° ° f t h e f o l l o W i n g apparent discrepancies cited in IP's brief (page citations are to the ip brief) ; onet

omitted^from *our"n pa?!!f ”achine department "laborers" were

s e n i S t y S L S inlx ' f ? Pp6ar Separate1^ the

the name implies (A. 12813-12893®! nGS' Whlle cleanuP do what

Ki-H srSlsSrSS

i S ) ip^sidatrStainSfinf°rniation c o n ^ i l ^ a s ^ f ^ c i n ^ r . 'Illl'

as of JU!y 1. 1972. There Is S'iiconsist^cy in s ^ t ^ i s M n e

- :jt s " c i n e ??-

wage" rate S i 5 i * «

Power plant^LOP IrS c?nFernin9 the number of Acs in the

enabled Z T o l e Inti thJt^Tne?7 Claim ^ GVen 3 AC Was

T/fTr̂ PflCOritê S b^ab aPPeH-ants ' statistical comparisons of the rela- lve economic situations of white and black employees are "meanincrless as a device for exploring the relative opportunitj for blacks ?o

advance,'• because they include blacks who have "signed out" for nr«m«

tions and are based on the permanent job wage raJefof ?£e employes

not actual earnings which take into account temporary setup (Br Y16-'

on!' ,b l f e„ T ^ admits that whites as well as blac^hive'signed out (Br. 19, n. 9) and, of course, whites also frecuentlv i-aVp

raJYinG!UPS above their permanent job classifications pi ex 9Pand

“ « “ = L ra ^ ? a | r farS ̂

-10-

hard facts away. IP does not seriously contend that the deficien

cies of the 1968 Jackson Memorandum, under which the stratification

persists, can be justified by the standard of business necessity.

Instead, IP admits that it subsequently agreed to provide residency

requirements, job skipping, a higher red circle ceiling, and the

subordination of recall rights through the 1972 Jackson Memorandum

(Br. 45-46), and argues only that by 1972 defendants "have gone as

8/far as business necessity permits" (Br. 36).

Whatever the substance and results of the 1972 Jackson Memoran

dum - and this Court cannot pass on that issue before supplementation

77 cont'demployees due to temporary setup is discernible - in fact, the con

verse is more apparent. This indicates that inclusion of temporary

rate data would not change the comparative standing of the two racial groups.

In any event, IP was in sole possession of the (putative) informa

tion required to discredit the value of plaintiffs' statistics, but declined to produce it. As this Court held in Pettway, supra, the

variables suggested by the company "do not ... weigh heavily enough to

lessen the appellants' empirical conclusions." 494 F.2d at 231.

"Without information on the percentage of white employees refusing

promotions and the types of promotions offered white employees, we

think the [statistic on blacks' promotion refusals] inconclusive."Id. 494 F.2d at 231, n.46.

We note that plaintiffs' data here in Pi.Ex. 1, 9, and 10 is simi

lar in form and content to the statistical proof relied on in the

Pettway decision, 494 F.2d at 227-230.

8/ Apart from the legal insufficiency of its argument, IP is factually

in error when it contends "that the 1968 Jackson Memorandum met and

exceeded the requirements of appellate court decisions through early

1971 ---" (IP Br. 44). Local 189 v. United States, 416 F.2d 980,

988-89 (5th Cir. 1969) made it plain that "all 'but-for' consequences

of pre-Act racial classification warrant relief under Title VII ...

unless there is an overriding, legitimate, non-racial business

purpose." This Court in Local 189 approved the very same residency

and job-skipping remedies that the defendants here failed to imple

ment under the 1968 Jackson Memorandum, 416 F.2d at 986 n.6, 990.

-11-

of the record - nothing in defendants' briefs gives any basis for

denying plaintiffs a decision that, at least until 1972, defendants

had failed to provide adequate remedy for their past discrimination.

B. IP's Arguments Fail to Justify the Unnecessary

Limitations of the Jackson Memorandum.

IP's attempts to justify the shortcomings of the 1968 Jackson

Memorandum fail on every count.

1. Red Circling Limitations

IP asserts no business justification for any of its red circle

limitations. Instead, it terms the $3.00 ceiling of 1968 "reasonable"

(Br. 47). But the authorities teach that as a matter of law the red

circle protection must be not "reasonable," but sufficient to assure

. 9/that no AC is penalized for moving away from segregated black LOPs.

The company seeks to minimize the impact of this artificial ceiling

by pointing out that "only 24 out of 324 ACs were at or above $3.00

in 1968" (Br. 47, n.37). But IP doesn't deny that shortly thereafter

in 1969, due to general wage increases, many more ACs earned more

than $3.00 in their permanent, traditionally black jobs; nor that

many more who regularly enjoyed temporary setups above their perma

nent job level were in fact not fully protected.

2. Job Skipping and Residency

The company's position on job skipping and residency is at

best ambivalent. It admits the importance of these remedies and

states that they will be negotiated as part of the 1972 Jackson Memo-

•2/ See main Br. 45, and see Pettway, supra, 494 F.2d at 248, prohibi

ting the imposition of any pay cut, even temporarily, upon ACs moving

into formerly all-white lines. Contrary to the inference on page 47

of IP's Brief, there is no indication in Judge Heebe's Local 189 opin

ion, 301 F. Supp. at 918, 923, that the $3.00 limit he approved was at that time below the highest paid traditionally black job.

-12-

randum (Br. 22). Yet it argues that even without them the district

court properly found that IP had fully complied with the relevant

legal standards for demonstrating seniority practices which are with

out present or continuing discriminatory effect" (Br. 39) (emphasis

added). Patently, these two assertions are irreconcilable under

correct legal standards.

IP attempts to confuse the issue by presenting job skipping,

advanced level entry, and minimum residency periods as merely lawyers'

concepts, not shown helpful to AC advancement (Br. 48-49, 57-58, cf.

10/ ' *UPIU Br. 39-40). Nothing could be further from the truth. IP admits

that limited availability of vacancies may retard AC movement (Br. 38).

As a corollary, if vacancies in long LOPs like the Pulp Mill (with

over 20 job levels to traverse) are infrequent, the "plugging effect"

described by IP (Br. 60—61 n.51) will make it impossible for signifi

cant members of ACs ever to reach their rightful places unless they

can bypass jobs not needed for training or remain for only necessarv

11/training periods m other jobs.

In Pettway, supra, this Court reaffirmed the importance of

advanced level entry and minimum residency periods as indispensable

parts of a complete remedy. The Court there notes, in language

equally applicable to a mill seniority system shackled by an unneces

sary step-by-step progression requirement,

1^/ Had appellees in 1968 met their legal obligation to designate those LOP jobs which could be skipped and to formulate minimum resi

dency periods for the others, the problem that produced the McCreedy Letter would never have arisen.

11/ The deterrent effect on ACs faced with the renewed prospect of step-by-step progress through lengthy job ladders after years climbing their old ones is obvious.

-13-

... a departmental seniority system is effective and

efficient as an instruction program only as to those positions in a line of progression where the jobs below them on the ladder serve as pre-pequisite

training steps. Thus, in a departmental line of pro

gression where the positions do not require specific

training or where on-the-job experience in another

department qualifies an employee, a departmental

seniority system is not efficient and is certainly not the best training method.

Pettway, supra, 494 F.2d at 246 (footnotes omitted). In providing

a remedy for such a system, the court required advanced entry (or

skipping) where feasible and establishment of minimum residency periods

for jobs necessary for training purposes, 494 F.2d at 248-249 and n.

106; cf. Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., supra, at 1374, n.28.

IP has "failed to demonstrate that every position at the plant

is so complex or specialized as to require, without exception, step-

by-step job progression within each department." Pettway, supra,

494 F.2d at 246. Indeed, IP has not proved the business necessity

of any of its LOP jobs. Rather it advanced at trial much the same

argument firmly rejected by this Court in Pettway and United States

v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert.

denied 406 U.S. 906 (1972) (see Pettway, supra, 494 F.2d at 245-247)

of "necessity" based only on the general theory that LOPs are a good

12/idea in an industrial situation.

±4/ IP incorrectly contends that the district court found "that each

job in the [LOPs] provides training and experience necessary to

develop the skills required to perform higher jobs in the LOP" (Br. 6) .

Actually, the court said only that "in the main ... jobs within a line

are functionally related to each other" (A. 126a, n.5), and "the evi

dence shows that with each advance the jobs affected tend to become

more complex and place demand for greater ... skill on the employees"

(A. 127a, n.6). These findings were taken verbatim from IP's post

trial Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, pp. 9-10,

except that Judge Hand omitted the proposed language that the LOPs

"meet the needs of business necessity," and "the court finds the same

considerations of business necessity have been served by [the require

ment of step by step advancement]."

-14-

[fn cont'd]

3. Discriminatory Implementation of the 1968 Jackson Memorandum. 13/

Understandably, IP argues that the Jackson Memorandum's success

should not be measured by its results in terms of AC advancement (Br.

60-61). By this standard, as UPIU recognizes, it was a "flop" (UPIU

Br. 38).

The problem of implementation is shown crucial by the stagger

ing statistic that almost 75% of all remaining ACs had, as of trial,

"signed out" (refused further promotion). Plaintiffs do not seek to

conceal this fact, as defendants suggest (main Br. 53, cf. IP Br. 61,

UPIU Br. 38); rather we deem it central.

IP attributes the sign-out phenomenon exclusively to the ACs'

own purported shortcomings and denies that its admittedly compromised

mill seniority system had any part in the problem (Br. 62-64). The

district court adopted IP's position unquestioningly. It agreed that

defendants fulfilled their duty when, under OFCC pressure, they nego

tiated a mill seniority system, cursorily published this change, and

then let nature take its course.

IP makes no apology for its failure to investigate or follow

up, even once, the massive promotion and transfer waivers among the

affected class, in spite of the harassment, intimidation and difficulty

H7~ cont' d

The Court's findings were based entirely on the trial judge's brief

tour of the mill and the general and conclusory testimony of IP Engi

neer Williamson (A. 124a, n.3). The company has never conducted a

technical job-by-job analysis of its lines (see A. 1144a-1145a). To

rebut these patently overbroad generalities, plaintiffs presented the

same kind of expert testimony found persuasive by this Court in Pettway, supra, 494 F.2d at 247 n.97. See main Br. 49-50.

13/ The portion of the pre-trial order set out on p.60 of IP's brief

plainly exonerates defendants only from failing correctly to apply

"the mill seniority provisions" of the 1968 Jackson Memorandum." Else

where in the pre-trial order plaintiffs set out in detail their com

plaints about harassment, intimidation, lack of training, and other

failures in implementation of the Memorandum (A. 87a-88a).

-15-

in obtaining training about which ACs complained at trial (main Br.

14/

54-56) .

On these facts, failures of implementation are indicated, and

the root cause is not hard to find. The law cannot turn a blind eye

to the fact that the "rightful place" remedy for prior racial segre

gation commits hopeful black employees to the tender mercies of the

same parties who, before the federal government intervened, devised

and operated a system of overt discrimination. <3f. Alexander v.

Gardner-Denver Co., 39 L.Ed.2d 147, 164, n.19 (1974); Glover v. St.

Louis-San Francisco Rwy. Co., 393 U.S. 324, 330-331 (1969) (employees

complaining of racial discrimination need not exhaust or be exclusively

bound to grievance/arbitration procedures controlled by discriminators).

The Jackson Memoranda provide no alternative to these unsatisfactory

channels for resolution of black employees' problems. A "necessary"

element of complete affected class relief is "a complaint procedure

by which a member of the class may question the interpretation or

implementation of the district court's decree," Pettway, supra, 494

F.2d at 263, 266-267, or likewise question the implementation of the

mill seniority system. Notwithstanding the district judge's opinion

that it will constitute "pampering" and "paternalism" (A. 123a), this

Court should remand with specific instructions to establish such a

procedure as part of the affirmative relief to which plaintiffs are

entitled.

n r IP incorrectly states that the issue of AC intimidation by white

employees and lower level supervisors was found to be "without merit"

by Judge Pittman in Herron-Fluker. That court did not discredit George

Herron's allegations of harassment and lack of training, but held only that the union (IP, of course, was not a party) was not guilty of

failing to represent Mr. Herron, because he had not filed a formal

grievance over these matters (A. 1939a, 1942a) .

-16-

Ill. The Company's Testing Battery Screens Out Blacks From

Maintenance Positions And Has Not Been Properly

Validated.

The company's brief in defense of its testing program does not

dispute plaintiffs' analysis of the applicable legal standards or

case law in any consequential respect. Rather, it tries to lift the

program out of the analytical context of those authorities by asserting

certain factual distinctions purportedly present in this case.

Because the company's argument rests primarily on a partisan view of

the facts, this reply will focus on the factual disputes indicated by

►

the parties' initial briefs.

15/A. Evidence of Disparate impact

Except in two very minor details (see infra), IP makes no sub

stantive reply to any of the plaintiffs' evidence of the tests' adverse

impact on blacks other than its lengthy, harsh, and somewhat misleading

attack on the weight of Pi.Ex. 6 (IP Br. 29, 70-75). While Pi.Ex. 6

(A. 1402a) is in fact a significant indicator of disparate impact when

fairly reviewed (see infra), we initially note that plaintiffs pre

sented a variety of other proof, all of recognized value, and IP has

not rebutted the substantive accuracy of any of that proof. (See main

Br. 24-26, 60-61; cf. IP Br. 70-77).

Instead, IP remonstrates that no experience other than specific

results at IP's own mills can have probative relevance to the issue

(Br. 76-77). This ostrich-like attitude, of course, runs contrary to

the federal courts' duty and practice of seeking out the truth from

n r We note initially but in passing that IP nowhere cites, and appar

ently refrains from defending, the district court's erroneous finding that "no evidence was offered concerning the impact of the testing

program on the ability of blacks to obtain employment at the Mobile

Mill" (A. 145a).

-17-

whatever sources available, subject to the rules of evidence. That

practice has been repeatedly endorsed by the courts in dealing with

this very question which is by its nature a relatively novel and16/

complicated one. IP's approach is not just unwise and unwarranted.

It sits particularly uncomfortably on this record because ip itself

has done everything possible to avoid the introduction of exactly

the kind of comprehensive, specific testing results which it now

claims alone will suffice. See, e.g., ip Br. 71, n.64 (ip refused

discovery of test scores of all applicants or employees), main Br. 61

and n.78 (IP objects to Personnel Manager, who knows, giving his best

impression of passing rates at Mobile Mill).

In two minor points that quickly crumble under analysis, IP does

contest the plaintiffs' evidence aside from Pi.Ex. 6.

(1) IP seeks to diminish the force of proof showing the over

whelmingly white composition (3 blacks out of 324, or 7 of 362) of its

maintenance force by generally asserting that "opportunities for

movement into these positions have been few" (Br. 76). Plaintiffs

can only guess what IP means by "few" since ajt least 97 craft job

vacancies occurred between July 2, 1965 and December 31, 1971 as

12/follows:

1§/ Griggs v. Duke Power Co.. 401 U.S. 424, 430, n.6 (1971); Moody v.

Albemarle paper Co., 474 F.2d 134, 138, n.1 (4th Cir. 1973), pending

on rehearing en banc; united States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

supra at 456; cf_. Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., supra at

1371, nn.8-10; and United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906,918 (5th Cir. 1973) (high school education requirements).

17/ Source: Seniority lists, Ex. K to IP's Answers to Plaintiffs'

First Interrogatories (A. 1859a-1863a, 1868a-1869a). A vacancy was

presumed to have existed in each case where an employee on the list

carries a departmental seniority date after July 2, 1965. This tabu

lation does not, of course, include person who filled vacancies after

1965 but were no longer on the lists as of 1971. Of the 97 individuals

counted, five were blacks — two Oilers, two Instrument Man Apprentices,

-18-

Shift Electrician and

Repairman — 2 5

Repairman Apprentice — 6

Shift Instrument Man — 7

Instrument Man — 2

Shift Electrician — 1Millwright Apprentice — 25

(2) IP also claims that the

Pipefitter Apprentice — 13

Steel Worker — 5

Sheet Metal Worker — 2 Welder — 7

Machinist — 4

Machinist Apprentice — 4

Oilers — 10

Minnesota Paper Form Board

Test, which is one-third of its maintenance test battery (A. 1463a),

was not involved in Georgia Power (Br. 70, n.62, 76, n.73). This is

incorrect. While the Court did not explicitly discuss the Minnesota

test there, it was a part of Georgia Power Company's testing program

which the Court found had disparate impact and had not been validated.

See, e.g., 5th Cir. No. 71-3447,

18/

Georgia Power Co. Ex. 1(b), Appendix,

Exhibit Volume pp. 21-44.

The most direct answer to IP's brief is that Pi.Ex. 6 is sound

evidence which, together with plaintiffs' other evidence including

the near-total absence of blacks from maintenance jobs, proves

adverse impact. IP's attack on the exhibit distorts its figures and

then extrapolates to draw conclusions based on the modified data.

PI.Ex. 6 only records the pass/fail rates of 57 whites and 6

blacks who applied for apprenticeship positions in 1970-1971 and who

were accepted or rejected by December 31, 1971. It does not, and

could not, include those 11 whites and 2 blacks whose applications

17/ cont'd

and one Millwright Apprentice. While many of the 97 vacancies were in

journeyman slots, 63 of them (including the lesser-skilled Oilers)

were not.

If the count had included persons who entered their craft depart

ment after September 1, 1962 - the date IP claims to have opened main

tenance jobs to blacks - the total number would be considerably higher (but the number of blacks would remain at five).

18/ Georgia Power used the Minnesota test to screen for the jobs of

draftsman, field estimator, and instrument man with a passing score of

40. (IP requires a score of 45, A. 1463a).

-19-

had not been acted upon when IP provided plaintiffs with Ex. Q (A.

1876a-1879a), of which Pi.Ex. 6 is a summary: Ex. Q does not indicate

test success or failure except as a comment on whether and/or why an

applicant obtained an apprentice position in 1970-1971.

IP has juggled the numbers on PI.Ex. 6 by adding in the two

blacks whose applications were accepted after service of Ex. Q but

before trial (IP Br. 72-73). Simultaneously and without record evi

dence that this actually occurred, IP lumps in all 11 whites listed

on Pi-Ex. 6 as "no action" with the other 35 who are shown on Pi.Ex.

6 as not accepted, treating all 46 as "failed to be accepted" (Br. 73)

The record does not show whether some or all of these 11 whites may

have been rejected - or accepted - by the time of trial, or for what

reason. Nor does the record show how many other whites, apart from

the 68 on Pi.Ex. 6, may have applied, passed the tests, and been

accepted for apprenticeship between January 1, 1972 and the date of

trial. For all these reasons, the Court must regard Pi.Ex. 6 as what

it is - a survey of limited but relevant information (all that IP

would produce) over a specific period of time. As such, it is proba-

tive of disparate impact notwithstanding IP's selective use (and

19/selective withholding) of further information to undercut its value.

19/ “IP further diverts attention from the true meaning of Pi.Ex. 6

by its clever statistical analysis of acceptance rates (Br. 74-75)

But the issue here is not acceptance rates (which reflect a variety

of factors, c_f. Pi. Ex. 6) - but rates of passing the tests. Pi. Ex.

6 shows that, excluding the "no action" group, only 16.7% (1 of 6) of

blacks passed, compared to 47.8% (22 of 46) of whites passed. (Pi.Ex.

6 and Ex. Q contain no test-success information about the 11 whites rejected for reasons other than test failure.) Addition of the two

subsequently successful blacks brings the black figures to 37.5% (3

of 8), thus reducing but not eliminating the disparate passing rates. One can only wonder what the final score would have been had IP chosen

at trial to include the 11 whites from the "no action" list.

20-

Plaintiffs have thoroughly proved that IP's testing battery

disproportionately excludes black employees from maintenance positions.

IP's response fails to show otherwise and succeeds only in muddying

the waters.

B. Validation

Plaintiffs' attack on the Tiffin-Scott validation study is not

a series of super-technical quibbles as IP suggests (Br. 78-79), but

a broad challenge rooted in plain common sense as well as professional

and legal standards.

1. Ihe narrowness of the data base for the Tiffin-Scott study

Plaintiffs have shown that the total number of employees studied

in the Tiffin-Scott validation survey was but a tiny fraction (2%-3%)

of those in jobs for which the tests were thereby purportedly validated

(main Br. 64-65). The percentage of the total number of jobs in the

Southern Kraft Division that was actually studied is not much higher (id.).

IP does not dispute this striking fact, although it attempts to

obscure it (see infra). Thus, it remains uncontested that the company

seeks judicial approval for a sweepingly broad testing program, but

has given the courts only a minuscule sample on which to base that

approval. Under proper standards, IP cannot buy so much for so little.

See, Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., supra at 138-140.

Nowhere is IP's tactic more clearly visible than in the group

of jobs most pertinent here - maintenance positions at Mobile Mill.

IP attempts to obscure the narrowness of its survey by a chart (Br.

87-88, n.86) which combines "apples and oranges" - a listing of the

number of craft job incumbents a_t Mobile coupled with a listing of

significant correlations anywhere in the Southern Kraft Division. A

more accurate depiction of the actual scope of validation would either

-21-

show only those jobs and tests for which correlations were found at

20/

Mobile or would indicate the sparsity of the correlation data viewed

21/on a Division-wide basis.

IP's weak argument that a broader data base was not necessary

is without support in its brief. ip cites plaintiffs' expert as con

ceding that not every job need be studied (Br. 86 and n.85); this is

a far cry from agreeing that a 2%-3% sample of affected employees is

-̂ 2/ Such a chart would show correlations as follows (Source: D.ExA. 1466a-1470a) :

Wonderlic Bennett Minnesota

Electrician X None NoneInstrument Man X None NoneMillwright, Pipefitter, )

Steelworker, Sheet Metal )

Worker, Welder, Machinist,)i None None NoneInsulator, Auto Mechanic, )Carpenter )

All crafts 2 0 0

This, of course, looks quite different from IP’s chart in n.86.

21/ Such a chart would indicate the following (Source: D.Ex. 6):

Wonderlic Bennett Minnesota

Millwright (10 mills) X (3 mills) X (3 mills) X (1 mill)Pipefitter (10 mills) X (2 mills) X (1 mill)Steelworker (10 mills)

Sheet Mtl. Wrkr. (10 mills) X (1 mill)Welder (10 mills) X (2 mills) X (1 mill)Machinist (10 mills) X (3 mills) X (2 mills) X (1 mill)Insulator (10 mills) X (3 mills)Auto Mech. (10 mills) X (1 mill) X (1 mill)Carpenter (10 mills) X (3 mills)Instr. Man (10 mills) X (2 mills)Electrician (10 mills) X (1 mill) X (2 mills)

All crafts (11 crafts 7 crafts, 8 crafts, 3 crafts,each in 10 mills) = 110 14 valida- 16 valida- 3 valida-possible validations tions tions tionsfor each test. total total total

Once again, this chart tells a much different - and more accurate -story than IP's n.86.

-22-

sufficient. IP also cites to the EEOC Guidelines, 29 C.F.R. § 1607.4

(c)(1) (id.); however that subsection obviously contemplates partial

sampling in the context of lengthy production LOPs and is not appli

cable to craft jobs which have either no progression or a one-step

progression, e.g., apprentice to journeyman.

2. Battery test usage vs. individual test validation

IP does not answer plaintiffs' argument, anchored on Georgia

Power, supra at 916, that where tests are used in a battery they must

be validated as a battery (main Br. 67-68). Although IP has some

ready excuses (in part involving, once again, what OFCC requested)

(Br. 85-86), the company in effect concedes that it made no valida

tion studies of the battery. For example, even if one sets aside the

point made in (1) above and deems validation of a test at any mill

sufficient to show validity at Mobile, IP's maintenance battery is

validated for only two of the eleven crafts (millwright and machinist)

shown in its chart (Br. 87 n.86). Yet nobody can get into an appren

ticeship program at Mobile by passing only two of the three tests.

3. Accuracy and reliability of validation survey

IP tries to hedge on the unprofessional practice (cf. A. 799a)

of the responsible person who deleted all the "unsuccessful" results

from the purported survey of validation results (Br. 27 n.19, 85).

The pertinent testimony (quoted only in part by IP) will resolve this

dispute:

Q. Did you just testify that O.F.C.C. did ask for the negative data?

A. [Dr. Scott] As I recall, they did. In any event,

we submitted it to them.

Q. When was that?

A. Well, my memory is vague. i prefer that that question

be directed to somebody who did for certain.

-23-

(A. 746a-747a). That "somebody" was Mr. Oliphant (A. 583a). He

testified (A. 662a):

Q. Did O.F.C.C. direct you to report summaries of all

or only of those studies which showed a significant correlation?

A. They directed that we report to them, studies that showed evidence of validity.

Q. And you interpret that as requiring - not requiring

to report evidence which does not show that validity?

A. I interpreted it as they said. , They said, "what

evidences did you have of validity?"

Likewise, in response to plaintiffs' interrogatory concerning

validation studies (Pi. First Int. to IP No. 65, 66) and on direct

examination IP discussed only its "good" results (A. 592a). That

there were others only appeared through cross-examination. Together

with other indicated omissions (main Br. 66), such practices cast

doubt on the whole study.

4. Differential validation

In light of Georgia Power, IP has now fallen back to reliance

on its argument that differential validation, even if a good idea,

was not feasible (Br. 82-84). IP bases that position on the fact that

there were only a handful of blacks in maintenance jobs (id. 83—84).

If by taking this position, IP wishes to concede that the purported

validation of Wonderlic and Bennett for a number of production jobs

22/is not material to the narrow issue in this appeal, we would

heartily endorse that suggestion and proceed to a closer examination

of the validations for maintenance jobs alone.

^~/ if it is material, of course, then the Court must accept plain

tiffs' unanswered suggestion that IP could have separately tested

black production workers (main Br. 68-69). It then follows that IP defaulted on its legal burden.

-24

5. Does the maintenance test battery predict success in maintenance jobs?

After reviewing all of IP's arguments, the Court must clearly

answer this question in the negative. Most obviously, the Minnesota

test has not been shown predictive of anything (main Br. 67), and it

forms an integral part of the battery. As to Wonderlic, a 12-minute,

50-question speed test of verbal and language skills, the somewhat

spotty results (A. 1466a-1467a) inevitably focus attention on the

Bennett.

One common-sense commentary on the Bennett test requirement

emerges from an analysis of the "expectancy charts" attached to Dr.

Tiffin's validation survey (A. 1471a-1508a). (See explanation at

A. 752a-754a). According to IP's own data on this concurrent valida

tion study (testing employees who already hold the jobs), one can

determine how many of the incumbents in the sample would pass the

test now required for their own jobs. For the Bennett test, in seven

of the nine maintenance samples studied, roughly half or more of the

incumbent journeymen could not now qualify for the apprenticeship23/

program. Since there is no suggestion that half or more of IP's

craft workers are incapable of performing their jobs adequately, the

±A/ The following table summarizes these data, showing the percentage of incumbent maintenance workers whose Bennett scores fall below theminimum scores of 45 (Form AA) or 37 (Form BB) (A. 1463a):

Mill Job (s) # in Sample % Failing

Springhill Electrician 20 40-60 %Springhill Millwright 21 60-80 %Georgetown Machinist, etc • 21 40-60 %Camden Welder, etc. 23 40-60 %Panama City Carpenter, etc • 5 40-60 %Springhill Carpenter, etc • 16 80 %Natchez Carpenter, etc • 18 40-60 %

Source: A. 1490a, 1492a-1497a ; see A . 754a-765a. These incumbentsapparently originally entered their jobs without having to pass theBennett, with its present high passing score.

-25-

Bennett test is manifestly not a necessary screening device. cf.

EEOC Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures, 29 C.F.R. § 1607.3(b).

6. The company has failed to prove its tests valid

Perhaps sensing that the present record will not support a find

ing of test battery validation, IP refers to the Georgia Power

decision, in which this Court remanded in effect to give the company

a second chance under the newly-articulated standards, 474 F.2d at

917-918. Plaintiffs note the history of that testing program on

remand. On April 1, 1973, Georgia Power Company suspended all test

ing, and on January 31, 1974, the district court entered a final

decree permanently enjoining the use of any testing program not first

validated in accordance with the EEOC Guidelines and this Court's

decision. 7 EPD ^9167.

Plaintiffs urge a similar result here without delay. This Court

should direct IP to suspend all testing unless and until it can

shoulder the burden of validation under proper standards which it has

not yet even approached.

IV. IP's Brief Fails To Rebut Plaintiffs' Showing That It

Unlawfully Excludes Blacks From Maintenance And Supervisory Positions.

A. Maintenance Positions

IP's brief makes no direct attempt to refute plaintiffs' argu

ments that they proved discriminatory exclusion of blacks from main

tenance craft positions. IP does not dispute plaintiffs' showing of

historical and statistical patterns of racial exclusion (main Br. 20-

21; cf. IP Br. 27-31). It does not dispute the existence of the 29

year age limit which, standing alone, effectively locks out ACs from

the crafts (ib.) . It quibbles confusingly and inaccurately about

the education requirement (IP Br. 28 n.21, see infra), and with

-26-

certain details of the testimony of the AC witnesses who testified

about their efforts to obtain maintenance positions (main Br. 21-22,24/

cf. IP Br. 29-31). It stresses the immaterial fact that at the

Jackson conference OFCC blindly failed to see any discrimination in

maintenance jobs (IP Br. 29, main Br. 71, n.92) see part 1(A), supra.

In fact, IP offers no substantive defense to its practices in regard

to craft jobs except that the maintenance test battery was non-dis-

criminatory. IP's defense does not even begin to address the burden

assigned in such cases by the court's opinion in United States v. Hayes

International Corp., 456 F.2d 112, 120 (5th Cir. 1972), to show that

qualified blacks are unavailable.

We argue elsewhere that the maintenance test battery violates

the Title VII rights of the plaintiff class. Here, we note only two

points about the tests. First, it is strange indeed that IP should

contest the fact that the test battery has a disparate adverse impact

on blacks, while not disputing the facts showing their near-total

absence from craft jobs and not explaining that absence on the basis

of any requirement other than the tests. Second, this Court can and

must reach the non-test issues presented by the maintenance problem,

/whatever its ruling on the tests. Not to reach those issues would

leave intact several discriminatory devices that, wholly apart from

the tests, would severely handicap blacks seeking to enter maintenance

jobs.

24/ ip~s points fail to meet the thrust of the testimony. Although

Louis Robinson was no longer interested in becoming a welder at the

time of trial (A. 938a), he certainly was an active candidate when IP

rejected him in 1968 (A. 935a-936a). (Cf. IP Br. 30). While IP takes

Dave Houston to task for failing to exercise Jackson Memorandum rights

to transfer to a mechanical job (IP Br. 31), it fails to note that the

1968 Jackson Memorandum did not give ACs any rights whatever for craft

positions (main Br. 20 and n.34). Griffin Williams' testimony does show

that he was excluded from maintenance jobs because, although he passed

the Wonderlie and Bennett tests, he failed the Minnesota Test (A. 1017a-

1018a). It also shows that IP would not in any event consider him because he was over 29 years old (A. 1335a).

-27-

IP's assertion that a high school education is not a requirement

for maintenance jobs (Br. 28 n.21) contradicts its own prior sworn

statement to the contrary (IP Answers to Plaintiffs' First Interroga

tories, Ex. H) . The cited testimony (A. 1141a-1142a) states that the

apprenticeship standards do require a high school education, but pass

age of the tests would be deemed acceptable in lieu of the educational

requirement. If the tests are modified or struck down, the educational

requirement would remain. Likewise, this Court must also deal with

25/an age requirement that serves to screen out 100% of the ACs.

This Court has recently struck down both a high school education

requirement and an age limit of 25 or 29 years as restrictions on entry

into apprenticeship programs, on a record substantially identical to

that presented here. Pettway v. ACIPCO, supra at 238-239, 245, 250.

There the court held, with respect to ACIPCO's apprenticeship program,

494 F.2d at 239,

The historical formal exclusion and the statistical and

testimonial evidence demonstrating disproportionate

exclusion of blacks by the testing and educational re

quirements, when combined with the continuing use of

the high school education or its equivalent standard

and the present age requirement and lengthy apprentice

ship term, constitutes not merely a prima facie case,

but conclusive proof of present effect from past dis

crimination. (footnotes omitted)

The Court has by now become familiar with the pattern prevalent

throughout this Circuit of industrial employers who reserve maintenance

and mechanic positions for whites only. See, e.g., Pettway v. ACIPCO,

supra; Buckner v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 339 F. Supp. 1108 (N.D.

£2/ The age requirement was shown to bar ACs from maintenance jobs.

Pi.Ex. 6 (A. 1402a) indicating that 8 whites but no blacks were

rejected in 1970-1971 because of age (see IP Br. 75 n.70), does not

prove the contrary. A number of black witnesses were prevented from

competing for vacancies when Personnel officials eliminated them because of their age (main Br. 22 and n.37).

-28-

Ala. 1972) , a f f1 d 476 F.2d 1287 (5th Cir. 1973) ; Johnson v. Goodyear

Tire & Rubber Co., supra; Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra.

IP has clung to this traditional pattern with unusual tenacity. The

time has now come to declare that employers in this Circuit, as exem

plified by IP, must open these highly sought after jobs to blacks on

an equal basis. This Court should order IP to take down its discrimi

natory barriers and take other appropriate affirmative action including

a specific requirement for promotion and hiring of a representative

number of black craft workers within a specified time period.

B. Supervisory Positions

IP's argumentative technique on the supervisory job issue seems

to be to confuse and obscure the facts as much as possible. Thus,

it claims there are two straw bosses and one supervisor who are black

(IP Br. 33), when in fact, as IP well knows, straw bosses are not

supervisors but hourly paid union members, and the single supervisor

is only a part-time relief man on that job, as IP elsewhere admits

(A. 373a-374a, IP Br. 90-91). Again, IP calls the cited record "barren

of any testimony whatever to support plaintiffs' contention that the

company had no intention of considering blacks for promotion to super

visor in the future." in fact, the cited record reads as follows:

Q. Are any black employees presently being considered for supervisory material?

A. [Mr. Carrie] Not to my knowledge.

(A. 375a, 376a). Mr. Carrie was then Personnel Director of Mobile Mill.

At its most obfuscatory, IP argues that there has been no proof

of any vacancies in line (non-professional) supervisory positions since

1965 (Br. 33, 88-91). IP implies, but with considerable art does not

state, that there were in fact no such vacancies. In fact, the record

makes clear that such vacancies must have been numerous.

-29-

Pi.Ex. 2 (A. 1389a), on which IP's discussion is based, shows

IP's supervisory staff only by date of original hire. That exhibit

does not purport to show when persons who were hired as production

employees and later promoted to management first reached the super

visory rank. Since IP's practice, as to such persons, is to require

that they spend a substantial period in hourly positions before pro

moting (Br. 90) , it is not surprising that no one hired as an hourly

worker since 1965 had by 1972 become a supervisor. It does not, how

ever, follow that there were no promotions of any hourly paid employees

to supervisory levels since 1965.

All the evidence points to a contrary conclusion. Exhibit E-4 of

IP's Answers to Plaintiffs' First Interrogatories shows a total of 55

exempt salaried employees who are line supervisors in the production

departments and whose initial salaried job was first line production

26/supervisor or supervisor trainee. These men promoted from hourly ranks

- the exhibit does not show when. It strains credulity to imply, as

IP does (without so stating), that none reached management ranks after

July 2, 1965. Once again IP, with full possession of all the facts

in its records, has chosen not to reveal all the pertinent information

while arguing that plaintiffs' partial - and strongly suggestive - data

does not really mean what it plainly indicates.

IP offers no defense to plaintiffs' argument that its system for

selecting line supervisors is a classic model of discrimination (Br.

26-27, 77-78; Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972)).

Instead of showing any business necessity or even any legitimate ratio

nale for that system, IP relies on a "common knowledge" not reflected

Maintenance supervisors are not included in this figure.

-30-

in the record (Br. 90) . it is not within plaintiffs' "common knowl

edge to divine why IP has never had a full time black supervisor at

Mobile Mill, unless the knowledge referred to is awareness of the

caste structure of employment at the International Paper Company.

And in this Court, such "common knowledge" cannot substitute for

record evidence.

In Pettway v. ACIPCO, supra at 241—243, this Court reiterated

the principles it first enunciated in Rowe, condemning a subjective

system for supervisory promotions. The Court remanded the issue in

Pettway only because of evidence that ACIPCO had recently begun to

strive to promote blacks to supervisory ranks (id. at 242-243 and n.81)

and because it was possible that illegal testing (since discontinued)

had been the sole cause of the exclusion of blacks (id. at 243). The

record here presents no such problems. IP had no intention of

changing its ways, see p. 29, supra, and the supervisory test had no

precise application and no specifiable effect (A. 371a-372a).

The question here is why, among IP's hundreds of loyal and long

time black production workers, none has reached supervisory positions.

The answer can only be race. The remedy must include a mandatory

injunction and affirmative remedial measures to assure the promotion

of qualified affected class members to supervisory positions.

v- Under Recent Controlling Authority the Court Must Award Plaintiffs Class Back Pay.

Since the submission of appellants' main brief, this Court has

entered a series of landmark decisions clarifying its conviction,

previously announced in United States v. Georgia Power Co., supra, that

class back pay is an appropriate and necessary component of Title VII

relief. Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., supra; Pettway v.

-31-

ACIPCO, supra; Duhon v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 494 F.2d 817

(5th Cir. 1974); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra; Baxter

v. Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., supra. The standard in this Circuit

is now clearly the same as that cited in our main brief (at 80-81) and

27/previously articulated by the Fourth and Sixth Circuits.

This Court's recent decisions specifically refute each of IP's

feeble arguments against a back pay award. Neither the subjective

reasons why IP continued to discriminate nor the purportedly unsettled

state of the law can provide any defense to back pay.

Whether an employer is beneficent or malevolent in

implementing its employment practices, the same pro

hibited result adheres if they are discriminatory;

economic loss for the class of discriminatees. In

Title VII litigation, neither benign neglect nor

activism will be judicially tolerated if the outcome

of such practices is racially discriminatory and

results in monetary loss.

Baxter, supra. Slip Op. at 4382. See also, Johnson, supra, at 1377;

Pettway, supra, at 255-256. IP cannot defeat liability by alleging

good-faith reliance on OFCC determinations (IP Br. 95), see part I(A),28/

supra. IP's attempt to elevate the weak and erroneous administrative

advice of OFCC — not the Title Vll-designated agency, EEOC — to the

level of state law, as a "special circumstance" justifying denial of

back pay (Br. 97), does not even merit further argument in light of

/// "... [W]here employment discrimination has been clearly demonstra

ted, employees who have been victims of that discrimination must be

compensated if financial loss can be established." Johnson, supra, at 1375.

"Once a court has determined that a plaintiff or complaining class

has sustained economic loss from a discriminatory employment practice,

back pay should normally be awarded unless special circumstances are present." Pettway, supra, at 252-253.

28/ In Pettway, the company unsuccessfully argued that it should not

be held to back pay liability resulting from OFCC-approved testing

practices, both in its initial brief and in its rehearing petition, which was denied (494 F.2d 1296).

-32-

the "special circums tances" discussion of Johnson (491 F.2d at 1377)

and Pettway (494 F.2d at 253-254).

Johnson, Pettway, and Baxter establish detailed guidelines for

the further proceedings necessary here to determine the scope and

2 9/

amount of appellees' back pay liability. The district court should be

directed to adhere to these standards. At least one separate, bifur

cated proceeding will be necessary, £f. Baxter, supra, at 4382. In

that proceeding, the district court must follow the procedures with

regard to allocation of burdens of proof, elements forming the basis

for any award, and resolution of uncertainties, adopted in Johnson,

Pettway, and Baxter. This Court should instruct the court below to30/

do so.

VI. The Union's Argument That The District Court Did Not

Erroneously Raise Prior Litigation In Bar To This

Action Is Contrary To This Record And To The Union's Position In Related Litigation.

Defendant UPIU has chosen for its major thrust to exhort this

Court not to reach the substantive merits of plaintiffs' claims, by

strenuously supporting the district court's application in bar of the

31/

Herron-Fluker litigation (UPIU Br. 12-35). Defendant IP, evidently

2.9/ Of course, as noted in Johnson, supra, 491 F.2d at 1381-1382, the

union appellees must share in this liability since they participated in perpetuating the discrimination.

30/ Perhaps sensing the weakness of its back pay argument, IP has pre

maturely raised issues as to the statute of limitations (Br. 92n.89).

If this Court chooses to rule on that question, we submit that the

correct limitations period is obviously the two (2) year period prior

to the filing of EEOC charges, as explicitly stated in Section 706(g)

of the Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g). To the extent that Georgia Power

may imply a shorter period, it is inapplicable because it was initially

decided prior to the 1972 amendments to Title VII which added the two

year statute to § 706(g). As all the cases hold, the applicable period

is tolled under both statutes by the filing of EEOC charges.

31/ The remainder of the UPIU brief is a perfunctory seniority argument,

based entirely upon unsubstantiated generalities (Br. 3 5-41) , in which even UPIU apparently does not seriously believe, see part B, infra.

-33-

more cognizant of this Court's insistence on painstaking factual

32/review of records of industrial discrimination, merely nods toward

the union's Herron-Fluker argument but does not press it at any length

(Br. 40).

A. The UPIU Argument Rests on Faulty Characterizations

and Assumptions

The union's res judicata argument rests on serious factual dis

tortions relating to both appellants' position and the Herron-Fluker

record and fails completely to address the bulwark of plaintiffs'

legal argument.

UPIU has attempted to confuse and distort the facts concerning

what Herron-Fluker did and did not decide. The defendant pulls iso

lated lines, fragmented findings, and particular statements - all out

of context - from a lengthy record. UPIU would have this Court attri

bute talismanic significance to those few words. But reality dashes

UPIU's hopes: a review of the basic documents from Herron-Fluker (set

out at A. 1881a-1948a) clearly demonstrates that UPIU's carefully

3 3/edited selections are more artful than meaningful. Compare, e.g.,

UPIU Br. 22-24 setting forth a few of the Herron-Fluker plaintiffs'

32/ cf. Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., supra; Pettway v.

ACIPCO, supra; Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra; Baxter v.

Savannah Sugar Refining Corp., supra.

33/ Plaintiffs do not contend, and never have contended, that no word

was breathed in Herron-Fluker about the underlying IP-UPP practices

of employment discrimination. Rather, we pointed out that such dis

cussion was necessary background to the real subject matter of that

suit - union-representation discrimination (Br. 35).

At the heart of the matter, the Jackson Memorandum's factual and

legal sufficiency was not in issue in Herron-Fluker (see colloquy set

out at UPIU Br. 19), but Stevenson centers on that question. Thus,

in comparing the Jackson Memorandum to the Local 189 principle, the

Herron-Fluker plaintiffs' counsel obviously did not and could not

maintain that such a solution necessarily ends all of the discrimina

tion's effects. See appellants' main Br. 43-44.

-34-

proposed fact findings, which mention the "Jackson Agreement" and

related seniority provisions, with those plaintiffs' proposed legal

conclusions and post-trial prayer for relief, which concern only

union-representation issues (A. 1927a-1929a). UPIU has conveniently

omitted any mention of the latter.

A full review of what plaintiffs actually sought to litigate or

could have litigated in Herron-Fluker (see main Br. 32-36) - as opposed

to what UPIU says they did - will strongly confirm that this case is

correctly characterized as "a completely different cause of action"

from Herron-Fluker (id. 37). Nor is this characterization any product

of tardy or result-oriented reformulation. Even in their prayer for

limited relief in Herron-Fluker, the plaintiffs expressly noted to

Judge Pittman the pendency of Stevenson, "in which a broadened class

of plaintiffs challenges the alleged unlawful employment practices of

the company and the union throughout the Mobile plant" (A. 1928a, n.1).

This Court should not be misled by UPIU's attempts to confuse

34/the record as to plaintiffs' positions here and in Herron-Fluker.

Nor can it fail to pierce through UPIU's argumentative technique, in

characterizing the Herron-Fluker decision, of lumping what is obvious

35/and uncontested together with what is wholly unsubstantiated.

*2/ UPIU's effort to infer that present counsel did not know what

Herron-Fluker involved (UPIU Br. 13-16) is utterly unfounded. Colloquy cited infra indicates that counsel had carefully reviewed the Herron-

Fluker record, except for the transcript which had been unavailable

to them (A. 282a-283a). After they had read the transcript, it only

reaffirmed their position and their prior understandings.

35/ E.g., UPIU asserts,

"the Herron-Fluker decision is clearly res judicata as

to the issues of fl] union merger, [2] processing of grievances, [3] promotion, and [4] seniority, as well

as [5] any individual claims of black employees who

worked within the former Papermaker jurisdiction."

[fn cont'd]

-35-

Finally, this Court must reject UPIU's facile assertion that

Judge Hand did not really take Herron-Fluker to bar plaintiffs' case

(UPIU Br. 12, 16-18). in fact, the court below allowed plaintiffs to

put on most of their evidence only after long and often heated collo

quy (see, for example, A. 182a-185a, 218a-225a, 349a-365a, 506a-509a).

It refused to allow some evidence into the record and refused to

accept proffers pursuant to Rule 43(c), F.R.C.P. It indicated that

in allowing such evidence it was only permitting plaintiffs to make

their record and repeatedly interjected its viewpoint that Herron-