Tompkins v. Texas Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Tompkins v. Texas Brief Amicus Curiae, 1988. 65956a4d-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e24f2d98-5af2-4576-8fc7-9610bf490437/tompkins-v-texas-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

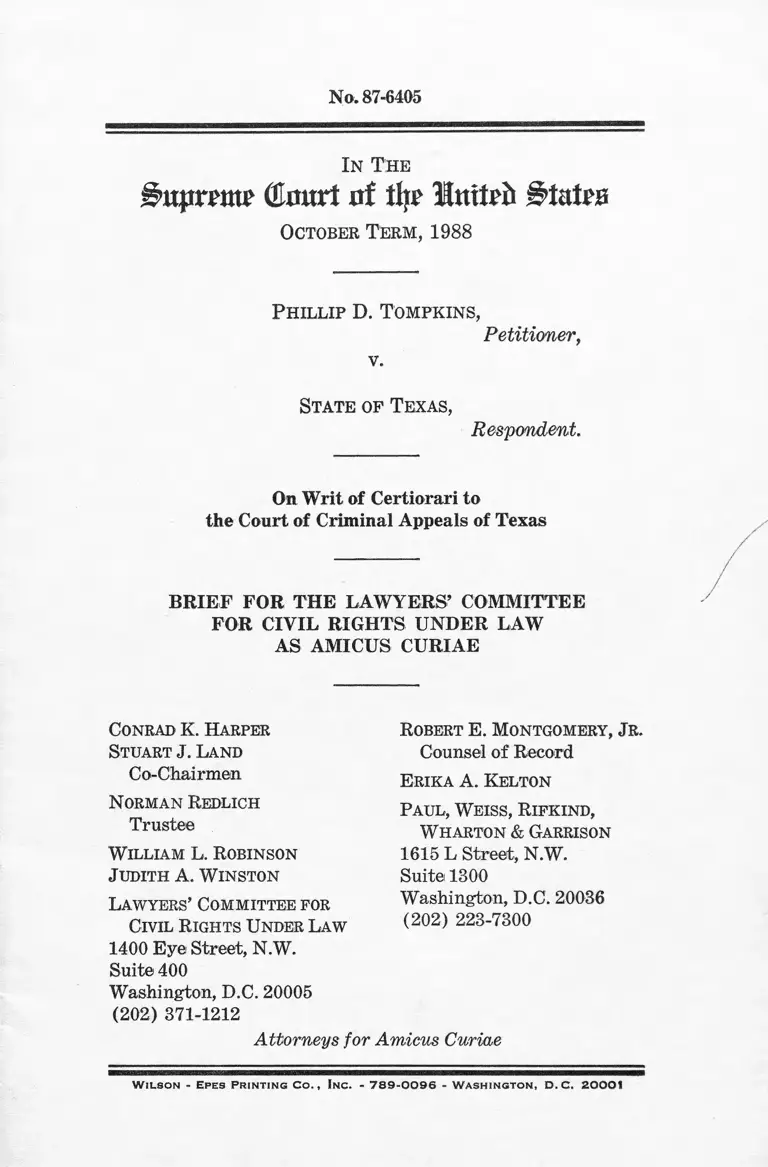

No. 87-6405

In The

(tart at tfyr Mnftrft BtaUa

October Term, 1988

Phillip D. Tompkins,

Petitioner,

v.

State of Texas,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to

the Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Conrad K. Harper

Stuart J. Land

Co-Chairmen

Norman Redlich

Trustee

W illiam L. Robinson

Judith A. W inston

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Robert E. Montgomery, Jr.

Counsel o f Record

Erika A. Kelton

Paul, W eiss, Rifkind,

W harton & Garrison

1615 L Street, N.W.

Suite 1300

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 223-7300

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

W il s o n - Ep e s P r in t in g C o . , In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h in g t o n , D .C . 2 0 0 0 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................... iii

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS

CURIAE....... .................................................................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .......................................... 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................................... 3

ARGUMENT.......... ....1,........................................... ........... 5

I. BATSON v. KENTUCKY REAFFIRMS LONG-

ESTABLISHED PRECEDENT THAT JURY

SELECTION MUST BE TOTALLY RACE

NEUTRAL............................................ 5

II. THE TRIAL COURT ABDICATED ITS RE

SPONSIBILITY TO EYAULATE THE LEGIT

IMACY OF THE PROSECUTOR’S EXPLANA

TION OF PEREMPTORY CHALLENGES

AGAINST WHICH A PRIMA FACIE CASE

HAD BEEN M ADE............................................. 9

A. The Trial Court Must Actively Scrutinize

The Prosecutor’s Explanation For Pretext

And Mixed Motives.......................... .............. 9

B. The Trial Court Utterly Failed To Fulfill Its

Duty To Determine The Legitimacy Of The

Prosecutor’s Explanations ............ 15

C. The Trial Court May Consider Only The

Prosecutor’s Actual Reasons For Challenge.. 18

III. THE APPELLATE COURT APPLIED IN

CORRECT STANDARDS OF REVIEW ........... 19

A. The Court Of Criminal Appeals Failed To

Review The Legal Sufficiency Of The Trial

Court’s Findings ............................................. 20

B. The Court Of Criminal Appeals Erred By

Reviewing The Trial Court’s Findings Ac

cording To A “Rational Basis” Standard,

Instead Of The “ Clearly Erroneous” Stan

dard Required By Batson ............................... 22

11

1. The Court Of Criminal Appeals Failed

To Review The Entire Record Before

Upholding- The Trial Court’s Findings

Regarding The Prosecutor’s Intent....... 24

2. The Court Of Criminal Appeals Failed

To Hold The Trial Court’s Findings

Clearly Erroneous, Despite Its Convic

tion That Those Findings Were Not

Credible......................... 25

CONCLUSION ................ 28

TABLE OF CONTENTS— Continued

Page

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) ..................................................................... 12

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625 (1972) ...A, 5, 9,11

Amadeo v. Zant, 108 S. Ct. 1771 (1988) ............... 24

Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564 (1985) ..5, 23, 27

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Dev.

Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) ................~~....... 4,8,9,15

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986) ....... ....... passim■

Bose Corp., Inc. v. Consumers Union of United

States, Inc., 466 U.S. 485 (1984).......... 21,24

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282 (1950)---------------- 6

Commonwealth v. DiMatteo, 12 Mass. App. Ct.

547, 427 N.E.2d 754 (1988) ......... 14

Commonwealth v. Soares, 377 Mass. 461, 387 N.E.

2d 499, cert, denied, 444 U.S. 881 (1979)....... 14

Ex parte Branch, No. 86-500, slip op. (Ala. Dec. 4,

1987) ______ ______ _____ _________________ - 10,23

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880) ..... ......... 5

Floyd v. State, 511 So. 2d 762 (Fla. 1987) ........... 13

Gamble v. State, 257 Ga. 325, 357 S.E.2d 792

(1987) ......... ........................................... ..... -..... - 10,14

Garrett v. Morris, 815 F.2d 509 (8th Cir.), cert,

denied sub nom. Jones v. Garrett, 108 S. Ct.

233 (1987) ........ .............. ................... ............ 10,13

Gray v. Mississippi, 107 S. Ct. 2045 (1987)------ 21

Hopkins v. Price Waterhouse, 825 F.2d 458 (D.C.

Cir. 1987), cert, granted, 108 S. Ct. 1106 (1988).. 8

Inwood Laboratories, Inc. v. Ives Laboratories,

Inc., 456 U.S. 844 (1982) .................................... 23

Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307 (1979) .... ........ 20

Johnson v. State, No. 57,526, slip op. (Miss. May

18, 1988) (en banc).............. ........ ...................... 23

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co., 427 U.S.

273 (1976) ................... ........ ............................... 8,12

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ......... ................ .. ......................... ............ 4, 11,12

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) _______4,11, 20

People v. Hall, 35 Cal. 3d 161, 672 P.2d 854

(1983) .................................................... -.............. - 10,13

IV

People v. Trevino, 39 Cal. 3d 667, 704 P.2d 719

(1985) ............................. ........................ .................. 13,14

People v. Turner, 42 Cal. 3d 711, 726 P.2d 102

(1986) .................................................. ............ ..... 13

People v. Wheeler, 22 Cal. 3d 258, 583 P.2d 748

(1978) ................................................................... 13,14

Peters v. Kiff, 407 U.S. 493 (1972) ....... ................ 11

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982).. 21

Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534 (1961)............... 21

Roman v. Abrams, 822 F.2d 214 (2d Cir. 1987).... 13, 14

Schneckloth v. Bustamonte, 412 U.S. 218 (1973).. 20

Schuessler v. State, 719 S.W.2d 320 (Tex. Grim.

App. 1986)............................ - .................... ............. 23

State v. Alvarado, 226 Neb. 195, 410 N.W.2d 118

(1987) ................................................................... 23

State v. Antwine, 743 S.W.2d 51 (Mo. 1987),

cert, denied, 108 S. Ct. 1755 (1988) .................... 10

State v. Gilmore, 103 N.J. 508, 511 A.2d 1150

(1986)......... ..................................... ........................- 10,14

State v. Gonzalez, 206 Conn. 391, 538 A.2d 210

(1988) - ....................................................................... 24

State v. Jackson, No. 477A87, slip op. (N.C. May

5, 1988) ....................................................................... 23

State v. Slappy, 522 So. 2d 18 (Fla. 1988) ___ __ 13,14

Stone v. Powell, 428 U.S. 465 (1976).................... . 24

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880).... 5

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965) ________ 3

Texas v. Mead, 465 U.S. 1041 (1983).................. 19

Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v. Burdine,

450 U.S. 248 (1981) ____ _______________ __ ..11,12,18

Time, Inc. v. Firestone, 424 U.S. 448 (1976)....... 21

United States v. Chalan, 812 F.2d 1302 (10th Cir.

1987) ....... .................................................................. 14

United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333

U.S. 364 (1948) ...... ........ .......................... ...........5,23,27

Van Guilder v. State, 709 S.W.2d 178 (Tex. Crim.

App. 1985), cert, denied, 106 S. Ct. 2891 (1986).. 23

Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. 412 (1985) ................ 15

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ...... ....... 4, 8

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967)..................6,11, 20

Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971) .................... 19

Rule and Statutes

Supreme Court Rule 36.2........................................... 2

28 U.S.C. §§ 2254 (b ) , (d) ..... .............. ..................... 20

Article

Monaghan, Constitutional Fact Review, 85 Colum.

L. Rev. 229 (1985) ............................................... 21

In T he

B>ujrrottP ( t a i l nf % Hntteft JHata

October T e r m , 1988

No. 87-6405

P h illip D. T om pkins ,

v Petitioner,

State op T e xa s ,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to

the Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

AS AMICUS CURIAE

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963, at the request of the President

of the United States, to involve private attorneys in the

national effort to assure the civil rights of all Americans.

During the last 25 years the Lawyers’ Committee and its

local affiliates have enlisted the services of thousands of

members of the private bar in addressing the legal prob

lems of minorities and the poor. The Committee’s mem

bership today includes former United States Attorneys

General and Solicitors General, past presidents of the

American Bar Association, a number of law school deans

and many of the nation’s leading lawyers. The wide

spread perception that prosecutors have exercised per

emptory challenges in a discriminatory manner, and the

2

importance of the principle of equal justice under law,

prompted the Lawyers’ Committee to file a brief amicus

curiae in Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986). The

same concerns, coupled with the fact that the Batson

principles will remain extremely fragile until this Court

provides more guidance concerning their implementation,

prompt the Lawyers’ Committee to file a brief amicus

curiae in support of petitioner in this case. The parties

have consented to the filing of this brief, which is there

fore submitted pursuant to Supreme Court Rule 36.2.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioner Phillip Daniel Tompkins, a black man, was

convicted by a Texas jury of capital murder, based on his

alleged intentional killing of a white woman while in the

course of committing or attempting to commit robbery

and kidnapping. (J.A. 56.) He was sentenced to death.

(J.A. 56.)

The venire at petitioner’s trial included thirteen blacks.

Of these prospective black jurors, eight were challenged

for cause. The remaining five black venirepersons were

excluded by the prosecutor’s peremptory challenge. Peti

tioner objected and moved to quash the jury on grounds

that the prosecution had exercised its peremptory strikes

to purposefully exclude venirepersons on the basis of

race. The trial court overruled petitioner’s motion, and

did not inquire into the State’s reasons for striking all

the black venirepersons. (J.A. 57-58.)

While petitioner’s appeal was pending review by the

Court of Criminal Appeals of Texas, this Court decided

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986). In April 1987,

the reviewing court abated the appeal, and sent the case

back to the trial court with instructions to conduct a

Batson hearing. Following that hearing, the trial court

ruled that although petitioner had made a prima facie

showing of prosecutorial discrimination in the exercise of

3

peremptory challenges, that showing had been rebutted

by the State’s explanations for the suspect peremptory

strikes. (J.A. 47-49.)

The Court of Criminal Appeals affirmed the trial

court’s Batson findings and petitioner’s conviction, re

jecting petitioner’s constitutional claim under Batson on

the ground that the trial court had not acted irrationally

in finding that there was no discrimination. (J.A. 72-73.)

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case raises squarely the question of whether the

increased protection for defendants’ fourteenth amend

ment rights which the Court mandated in Batson v. Ken

tucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986) will be vitiated by ineffective

trial court procedures and overly deferential appellate

review. In Batson, this Court once again acknowledged

that “ [discrimination within the judicial system is [the]

most pernicious,” id. at 87-88, and that the potential for

such discrimination is especially great in connection with

prosecutors’ exercise of peremptory challenges. Id. at 96.

In response to this continuing threat, Batson altered

the twenty-year-old evidentiary ruling of Swain v. Ala

bama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965), to allow a defendant to rely

on evidence from his own trial to establish a pmma facie

inference of discrimination in the prosecutor’s use of

peremptory challenges. Once established, the burden then

shifts to the State to justify the suspect challenge by ar

ticulating “ a [legitimate] neutral explanation related to

the particular case to be tried.” Batson,, 476 U.S. at 98.

Having established the legal standards and the general

framework within which they should be applied, how

ever, the Batson court left important procedural ques

tions unanswered. Id. at 99. Justice White’s prediction

—that “ [m]uch litigation will be required to spell out the

contours of the Court’s equal protection holding today”

4

id. at 102 (White, J., concurring)—has proven correct.

Nov/, two years later, the Court must return to the Bat

son. problem and provide further guidance, without which

clearly unconstitutional peremptory challenges such as

those at issue here will he effectively immunized by in

adequate judicial scrutiny.

Petitioner Tompkins’ conviction should be held consti

tutionally defective under Batson on three separate

grounds. First, the decisions of the Texas courts were

apparently premised on the incorrect belief that peremp

tory challenges based in part, though not solely, on racial

grounds are permissible under Batson. This Court has

repeatedly held that where an individual’s fourteenth

amendment right to equal protection is threatened, con

duct based on mixed racial and nonracial motives is not

insulated from challenge. See, e.g., Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 265-66

(1977) ; cf. Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 240-42

(1976). Mixed-motive explanations are especially dan

gerous where, as in the case of peremptory challenges,

nonracial reasons may be easily generated. To allow any

thing but totally nonracial explanations would rapidly

undermine Batson’s protections.

Second, the trial court made factual findings that were

clearly insufficient as a matter of law. The Tompkins

trial court abdicated its obligation to ascertain the legiti

macy of the prosecutor’s justifications in light of Bat

son’s requirement that such explanations be racially neu

tral, non-speculative and logically related to the particular

case. Batson., 476 U.S. at 98. The lower court accepted

the prosecutor’s rebuttal at face value, thereby vio

lating that court’s duty to probe nonracial justifica

tions for pretext in light of the evidence and circum

stances of the case. See, e.g., McDonnell Douglas Corp.

v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 804 (1973); Alexander v.

Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625, 632 (1972); Norris v. Alabama,

294 U.S. 587, 593-96 (1935). Were trial courts not re

5

quired to make an earnest attempt to judge the legal

sufficiency and legitimacy of prosecutors’ rebuttal the

equal protection rights safeguarded by Batson would be

meaningless.

Finally, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals erred

both by failing to review the legal sufficiency of the trial

court’s determination, and by failing to apply a “ clearly

erroneous” standard of review. In the first instance, the

appellate court inappropriately deferred to the trial

court’s finding that the prosecutor lacked discriminatory

intent, even though such finding was based on an ob

vious misapplication of federal law. Second, the review

ing court failed to employ the “clearly erroneous” stand

ard of review contemplated by Batson. 476 U.S. 98 n.21.

Contrary to its obligation, the appeals court deferred

blindly to the court below, even though its independent

examination of the record “ east considerable doubt upon

the neutral explanations offered by counsel for the State.”

(J.A. 66 n.6A.) Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U.S.

564, 573 (1985) ; United States v. United States Gypsum

Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395 (1948).

ARGUMENT

I. BATSON v. KENTUCKY REAFFIRMS LONG-

ESTABLISHED PRECEDENT THAT JURY SELEC

TION MUST BE TOTALLY RACE NEUTRAL

An unbroken line of cases, beginning over a century

ago, has held that the Equal Protection Clause demands

that a person’s ability to serve on a jury be evaluated

exclusively in terms of individual characteristics, rather

than in terms of racial identity. Strauder v. West Vir

ginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880) ; Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S.

339 (1880).1 Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 76 (1986)

1 See, e.g., Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625, 632 (1972) (hold

ing that in order to constitutionally validate a prima facie case of

discrimination in venire selection the state must show that “permis

sible racially neutral selection criteria and procedures have produced

6

reaffirmed this promise of equal protection, by requiring

that where an inference of discrimination is raised by

prosecutors’ use of peremptory challenges, the State may

validate the suspect challenge only by providing specific,

logical and entirely nonracial reasons. Prosecutors are

duty bound “ to exercise their challenges only for legiti

mate purposes.” 476 U.S. at 99 n.22. Thus, once a

defendant has made a prima facie showing that the

prosecutor exercised his peremptory challenges in a dis

criminatory manner, the prosecutor “ must articulate a

neutral explanation” for his strikes. Id. at 98.

Batson’s requirement of racial neutrality must be con

strued to validate only those challenges that are moti

vated entirely by nonracial reasons. In Tompkins, the

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals implies that even

though challenges based on racial grounds alone are pro

hibited by Batson, challenges that are based on both

racial and nonracial grounds may be permissible. The

appellate court stated that if the prosecutor “admits a

racially motivated reason for exclusion, without more,

the trial judge should never find” that strike constitu

tional. (Emphasis added.) (J.A. 65 n.6.) The appellate

court further stated that a defendant’s prima facie show

ing of discrimination would stand unless the prosecutor

“ could come forward and demonstrate some ‘neutral’—

non-race related—explanation . . . .” (Emphasis added.)

(J.A. 61.) That court concluded that no constitutional

violation had occurred at trial, because the trial judge

“ found, implicitly, that the prosecuting attorneys did not

exercise their peremptories against the five black venire-

persons complained about solely on account of their race.

. . .” (Emphasis added.) (J.A. 62.)

the monochromatic result” ) ; Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545, 552

(1967) (holding that in venire selection procedures, where “ the

opportunity for discrimination was present . . . it [must not be]

resorted to” ) ; Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282, 286 (1950) (holding

that “ [j Jurymen should be selected as individuals on the basis of

individual qualifications, and not as members of a race” ).

7

While the above opinion language may not conclusively

demonstrate that the Texas courts have misread Batson,2

the transcript of the Batson hearing in this case leaves

little doubt on the point. Throughout the trial court’s

interrogation, the prosecutors freely and repeatedly con

ceded that even after this Court’s decision in Batson it

was the practice of the Harris County District Attorney’s

office to exercise their peremptory challenges based in

part on considerations of race.3

The Texas courts’ interpretation of Batson is mani

festly incorrect, Batson cannot fairly be read to allow

challenges which are based, even in part, on assumptions

that rely on race to judge an individual’s fitness as a

juror. If race-based assumptions contribute in any way

to the prosecutor’s decision to use a peremptory chal

lenge, the State’s reasons are not neutral— as Batson

expressly requires— and the strike violates the Equal

Protection Clause. To allow anything but totally non

2 Indeed, although Batson is replete with references to the princi

ple that the prosecutor’s explanation of suspect challenges must be

racially neutral, this Court’s opinion does contain language prac

tically identical to the last of the above quotations. 476 U.S. at 89.

8 Testimony elicited from Harris County District Attorneys at

the Batson hearing confirms that the race of veniremembers played

a part in those prosecutors’ decisions to retain or strike an indi

vidual, even though race may not have been the sole basis for exclu

sion. One prosecutor, when asked whether race would “enter into

[his] decision . . . to use a peremptory challenge,” answered that

he “would not exclude that person solely because of his race.” When

reminded that he was asked whether “ it would enter into [his]

decision making process” he responded: “ Oh, certainly. Certainly.”

Supp. R. vol. 1, 82-33. Indeed, Thomas Royce, the prosecutor who

exercised two of the three disputed peremptory challenges, agreed

that in selecting juries he presumed that blacks as a group were

more inclined to be sympathetic and lenient towards black defen

dants. Id. at 156, 162. Other members of the District Attorneys’

office noted that, in general, “ there was a caution exercised when

dealing with minorities,” id. at 182, and that “many of those people

have preconceived notions about law enforcement and government,”

Id. at 184.

8

racial explanations would quickly subvert Batson’s prom

ise of discrimination-free peremptory challenges.4 5

This conclusion is inescapable in light of this Court’s

repeated rejection of mixed-motive explanations in other

contexts. In Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Dev. Corp., the Court noted that racial discrimination

need not be the “ sole,” “primary,” or “ dominant” factor

in an official decision for the Equal Protection Clause to

be violated. It is enough that “ a discriminatory purpose

has been a motivating factor.” 429 U.S. 252, 265-66

(1977).6 Cf. Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 240-42

(1976). Where the constitutional right to equal protec

tion is threatened, therefore, mixed-motive explanations

will simply not suffice.

The standard applied by the Texas courts to the

sufficiency of the State’s explanation of its peremptory

challenges was thus fundamentally defective. Contrary

to those courts’ apparent understanding, a peremptory

challenge need not be based “solely” on racial considera

tions to be constitutionally impermissible. Where as

sumptions based on race play even a minor part in the

prosecutor’s decision to strike a potential juror, that chal

4 As Justice Marshall observed in Batson: “ Any prosecutor can

easily assert facially neutral reasons for striking a juror . . . . If

such easily generated explanations are sufficient to discharge the

prosecutor’s obligation to justify his strikes on nonracial grounds,

then the protection erected today may be illusory.” 476 U.S. at

106 (Marshall, J., concurring).

5 The principle that mixed-motive explanations are not sufficient

to rebut a prima facie ease of discrimination is also found in Title

VII case law. See, e.g., McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation

Co., 427 U.S. 273, 282 n.10 (1976) (noting that a Title VII plaintiff

need not prove that he was “ rejected or discharged solely on the

basis of his race” ) ; Hopkins v. Price Waterhouse, 825 F.2d 458

(D.C. Cir. 1987), cert, granted, 108 S. Ct. 1106 (1988) (holding

that mixed-motive explanations are insufficient to rebut the infer

ence of impermissible gender discrimination in employment

decision).

9

lenge is tainted. To satisfy Batson, the state’s explana

tion must convince the trial court that the race of the

juror had no bearing whatsoever on the decision to

strike.

II. THE TRIAL COURT ABDICATED ITS RESPON

SIBILITY TO EVALUATE THE LEGITIMACY

OF THE PROSECUTOR’S EXPLANATION OF

PEREMPTORY CHALLENGES AGAINST WHICH

A PRIMA FACIE CASE HAD BEEN MADE

A. The Trial Court Must Actively Scrutinize The

Prosecutor’s Explanation For Pretext And Mixed

Motives

Batson charged trial courts with responsibility for en

suring that prosecutors exercise their peremptory chal

lenges for only legitimate, race-neutral purposes. Batson,

476 U.S. at 98-99. Accordingly, trial courts are required

“ to be sensitive to the racially discriminatory use of

peremptory challenges.” Id. at 99. This obligation to

scrutinize thoroughly the State’s conduct for discrimina

tory purpose is not new to equal protection doctrine. As

this Court stated in Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 266

“ [d]etermining whether invidious discriminatory pur

pose was a motivating factor demands a sensitive in

quiry into such circumstantial and direct evidence of

intent as may be available.” Where discriminatory mo

tives are alleged to underlie official decisions, the trial

court has an active role in “ examin [ing] the purpose

underlying the decision.” Id. at 268. See also Alexander

v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. 625, 630 (1971) (trial courts may

find it necessary to undertake a “factual inquiry” that

“takes into account all possible explanatory factors” ).

Under Batson, a defendant alleging the impermissible

exclusion of veniremembers “may make out a prima facie

case of purposeful discrimination by showing that the

totality of the relevant facts gives rise to an inference of

discriminatory purpose. . . . Once the defendant makes

10

the requisite showing, the burden shifts to the State to

explain adequately the racial exclusion.” 476 U.S. at 93-

94. Accordingly, the adequacy of the prosecutor’s rebut

tal explanation must be tested by the trial court. To

ensure that only legitimate explanations are accepted,

the trial court’s inquiry must be designed to distinguish

sincere from contrived reasons, and wholly nonracial

from mixed motives.6

To fulfill its Batson obligations the trial judge must

take the initiative to evaluate each proffered explanation

in light of the factual and legal issues in the case, his

observation of the prosecutor’s voir dire and his knowl

edge of trial techniques. This role is fully consistent

with Batson’s requirement that trial courts be “alert”

and “ sensitive” to racially discriminatory challenges

while supervising voir dire. 476 U.S. at 99, n.22.’7

An active role for the trial court is also suggested by

numerous prior holdings of this Court that once a prima

facie inference of discrimination is raised, a probing 8

8 See, e.g., Garrett v. Morris, 815 F.2d 509, 511 (8th Cir.), cert,

denied sub nom. Jones v. Garrett, 108 S. Ct. 233 (1987) ( “ the

court has a duty to satisfy itself that the prosecutor’s challenges

were based on constitutionally permissible trial-related considera

tions, and that the proffered reasons are genuine ones, and not

merely a pretext for discrimination” ) ; People v. Hall, 35 Cal. 3d

161, 167, 672 P.2d 854, 858 (1983) (“ [I]t is imperative, if the con

stitutional guarantee is to have any real meaning, that . . . the

allegedly offending party . . . come forward with explanation to the

court that demonstrates other bases for the challenges and that

the court satisfy itself that the explanation is genuine. This de

mands of the trial judge a sincere and reasoned attempt to evaluate

the prosecutor’s explanation.” ) (Emphasis in original.)

1 See Garrett v. Morris, 815 F.2d at 511; Ex parte Branch, No.

86-500 slip op. at 21-22 (Ala. Dec. 4, 1988); People v. Hall, 35 Cal.

3d at 167, 672 P.2d at 858; Gamble v. State, 257 Ga. 325, 327, 357

S,E.2d 792, 794-95 (1987); State v. Antwine, 743 S.W.2d 51, 64-65

(Mo. 1987), cert, denied, 108 S. Ct. 1775 (1988); State v. Gilmore,

103 N.J. 508, 536-37, 511 A.2d 1150, 1164-65 (1986).

11

review of assertedly reasonable and neutral conduct is

necessary. Such is the teaching of Norris v. Alabama,

294 U.S. 587, 593-96 (1935) which found the State’s

rebuttal of a pnma facie inference of discrimination in

the selection of jury venires inadequate when that ex

planation was considered in light of the evidence in the

record. The sufficiency of the rebuttal must be assessed

in view of the entire circumstances as they have been

presented. See Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S. at 632;

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545, 550-51 (1967).

Likewise, in the employment discrimination context,

this Court has consistently ruled that the inquiry into a

complainant’s prima, facie case of discriminatory employ

ment practices or treatment is not complete once an em

ployer presents his explanation. The court’s inquiry must

also consider whether the “stated reason . . . was in fact

pretext,” McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

792, 804 (1972) ; Texas Dept, of Community Affairs v.

Burdine, 450 U.S. 248, 255-56 (1981).

In criminal prosecutions, earnest trial court scrutiny

of the legitimacy of the prosecution’s explanation of its

peremptory challenges is especially crucial.® Exclusion of

a cognizable class “may have unsuspected importance in

any case that may be presented.” Peters v. Kiff, 407

U.S. 493, 503-504 (1972). Certainly in petitioner’s case,

where he faces a sentence of death, the consequences of

constitutionally impermissible discrimination in jury se

lection could not be greater. To require less than the

closest scrutiny of a prosecutor’s explanation would

transform the Batson inquiry into a mere formality. 8

8 The trial court s duty to probe the State’s rationale is especially

critical where, as here, defense counsel was not afforded a mean

ingful opportunity to rebut the prosecutor’s explanation. Even

though defense counsel had no way of anticipating the explanations

the prosecutor would offer at the Batson hearing, the trial court

required that defense comment on the prosecutor’s explanations be

made within a few days of the Batson hearing’s close, but 2%

weeks before the record was transcribed. Supp. E. vol. 1 at 227-28.

12

The trial court must, first, elicit all of the prosecutor’s

reasons for a suspect strike, in order to ensure that

mixed motives are not present. To require less than all

of the prosecutor’s actual reasons would enable the state

to sustain impermissible mixed-motive strikes by identi

fying a single nonracial consideration. Once all of the

prosecutor’s reasons have been elicited and determined,

at least facially, to arise from completely nonracial mo

tives, the trial court must assure that each rationale is

legitimate and not pretextual. Batson requires that each

legitimate explanation be “neutral” and “related to the

particular case to be tried.” 476 U.S. at 98.9 These

criteria are most effectively tested by considering, gen

erally (1) whether similarly situated white and minority

veniremembers were treated differently, and (2) whether

the justification for challenge was legally or factually

relevant to the case at bar.

Analogous factors were credited by this Court in

McDonnell Douglas v. Green, 411 U.S. at 804, and

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co., 427 U.S.

273, 282-83 (1976), where evidence that similarly situ

ated white and black employees were treated differently

was considered especially relevant to the showing of pre

text in the Title VII context. Likewise, Albemarle Paper

Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 431 (1975) held that where

employers are required to show that an employment prac

tice bears a job-related reason, such reason must be

judged to be “ predictive of or significantly correlated

with important elements of work behavior which com

prise or are relevant to the job.”

To satisfy their duties under Batson, therefore, trial

courts must conduct an independent inquiry sufficient to

ensure that the state’s explanations are legitimate,

9 Batson further rioted that “the prosecutor must give a ‘clear

and reasonably specific’ explanation of his ‘legitimate reasons’ for

exercising the challenges.” 476 U.S. at 98 n.20 (quoting Texas Dept,

of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. at 258).

13

racially neutral and logically related to the case. At a

minimum, the trial court should undertake a detailed sua

sponte examination of whether: (a) minority veniremem-

bers were stricken, while similarly situated white venire-

persons escaped challenge;10 (b) the voir dire of minority

venirepersons appeared designed to elicit a particular re

sponse, and similar examination was not undertaken of

white venirepersons;11 (c) the challenged venireperson

was examined in a perfunctory manner, if at all; 12 and

10 Roman v. Abrams, 822 F.2d 214, 228 (2d Cir. 1987) (dissimilar

treatment raises suspicion that reason is pretextual); Garrett v.

Morris, 815 F.2d at 514 (challenges based on “ lack of education,

background, and knowledge” were invalid where whites with sim

ilar backgrounds survived challenge); People v. Trevino, 39 Cal. 3d

667, 691-92, 704 P.2d 719, 733 (1985) (challenges of Hispanic sur-

named venirepersons invalid where similarly situated whites ex

pressed similar ambivalence towards the death penalty but went

unchallenged); State v. Slappy, 522 So. 2d 18, 19-20 (Fla. 1988)

(peremptory challenge invalid where prosecutor explained that a

black elementary school teacher was struck as possibly being too

liberal while a white elementary school teacher was not challenged);

Floyd v. State, 511 So. 2d 762, 765 (Fla. 1987) (where prosecutor

struck black veniremember because he was a student, failure to

strike a white student was “ strong evidence” that the reason was

“a subterfuge to avoid admitting discriminatory use of the per

emptory challenge” ).

11 People v. Turner, 42 Cal. 3d 711, 726-27, 726 P.2d 102, 111

(1986) (minority venireperson struck because of single, ambiguous

response to prosecutor’s question); People v. Hall, 35 Cal. 3d at

165, 672 P.2d at 856 (only minority venirepersons were asked where

they grew up which served as basis for exclusion).

12 Garrett v. Morris, 815 F.2d at 514 (prosecutor’s reasons pre

textual when he had not explored in voir dire the purported basis

for challenge) ; People v. Turner, 42 Cal. 3d at 714, 726 P.2d at 111

( “prosecutor’s failure to engage . . . ‘in more than desultory voir

dire . . .’ is one factor supporting an inference that the challenge

is in fact based on group bias” ) ; People v. Wheeler, 22 Cal. 3d

258, 281, 583 P.2d 748, 764 (1978) ( “ the failure of [the prosecutor]

. . . to engage these jurors in more than desultory voir dire” may

support the demonstration of discrimination); State v. Slappy, 522

So. 2d at 23 n.2 (where two black veniremembers excused without

14

(d) the explanation offered by the State was not logi

cally related to the elements of the offense.13

In this last regard, it is essential that a logical correla

tion is established between the prosecutor’s rationale and

the legal issues and facts as they are known at the time

of voir dire. This inquiry is not simply an evaluation

questioning, the safeguards would be “meaningless . . . if, by sim

ply declining to ask any questions at all, the state could excuse all

blacks from the venire” ) ; Gamble v. State, 257 Ga. at 329-30, 357

S.E.2d at 795 (prosecutor’s explanations invalid where no voir dire

of challenged venireperson).

13 Roman v. Abrams, 822 F.2d at 228 (prospective jurors’ knowl

edge of computers, electronics, and bookkeeping not basis for ex

clusion on grounds that they may not be able to accept reasonable

doubt standard of proof); United States v. Chalan, 812 F.2d 1302,

1314 (10th Cir. 1987) (unspecified dissatisfaction with venireper-

son’s background and juror’s questionnaire not acceptable grounds

for exclusion ) ; People v. Trevino, 39 Cal. 3d at 689, 704 P.2d at 731

(prosecutor must show venireperson’s “ specific bias,” i.e., “bias re

lating to the particular case on trial or the parties or witnesses

thereto” (quoting People v. Wheeler, 22 Cal. 3d at 276, 583 P.2d

at 761)); People v. Wheeler, 22 Cal. 3d at 282, 583 P.2d 748,

765 (1978) (burden of justification will be satisfied where prose

cutor explains suspect challenges on grounds that are “ reasonably

relevant to the particular case on trial or its parties or witnesses—

■i.e., for reasons of specific bias” ) ; State v. Slappy, 522 So. 2d at 20,

23 (invalid strike where prosecutor stated that challenged venire-

member was too liberal because she was a school teacher but failed

to demonstrate that she shared that tra it); Gamble v. State, 257 Ga.

at 328, 357 S.E.2d at 795-96 (exclusion of potential juror because

he is a Mason invalid where “ it is not clear how Masonic member

ship is related to this case” ) ; Commonwealth v. Soares, 377 Mass.

461, 485, 387 N.E.2d 499, 514 (1979) (peremptory challenges valid

where a juror’s “ unique relationship to the particular case raises the

spectre of individual bias” ) ; Commonwealth v. DiMatteo, 12 Mass.

App. Ct. 547, 552-53, 427 N.E.2d 754, 757 (1981) (widowhood an

insufficient indicator of bias in a trial for armed robbery of a ser

vice station); State v. Gilmore, 103 N.J. at 542, 511 A.2d at 1168

(purported lack of intelligence not grounds for challenge where

issues to be resolved by the jury do not demand “high intellectual

achievement of the jurors” (quoting State v. Gilmore, 199 N.J.

Super. 389, 411-12, 489 A.2d 1175, 1187 (1985))).

15

of the prosecutor’s credibility as a witness during the

Batson hearing. Nor is the judge merely “ applying some

kind of legal standard to what he sees and hears,” as the

judge does, for example, when he determines juror bias

against the death penalty. See Wamwright v. Witt, 469

U.S. 412, 429 (1985). Rather, the prosecutor’s explana

tion must be rationally and analytically related to the

case being tried.

Finally, the trial court’s formal findings must supply

sufficient detail to assure that upon review the basis for

each Batson-related conclusion is clear. Absent such ex

planation, a reviewing court will lack the necessary un

derstanding to distinguish those findings entitled to great

deference from those which are not.

B. The Trial Court Utterly Failed To Fulfill Its Duty

To Determine The Legitimacy Of The Prosecutor’s

Explanations

In Tompkins, the trial court completely abdicated its

Batson obligations. The repetitious and conclusory nature

of the court’s findings is itself a strong indication that

the State’s rebuttal explanations were accepted on their

face. In each instance, the court recited as if by rote

that “ the State’s excusal . . . was neutral, relative, clear

and legitimate as required by Batson and was not racially

motivated.” (J.A. 47-49.) When the stated basis for those

findings is examined, the court’s failure to evaluate in

dependently the State’s explanations is obvious with re

spect to three of the five veniremembers challenged

peremptorily. In each case, the record reflects that the

prosecutor’s explanations were neither neutral nor logi

cally related to the matter at bar.14

14 Although in this case three peremptory challenges are suspect,

it should be noted that the improper exclusion of only one of the

veniremembers would be constitutionally offensive. As Batson

stated: “ ‘A single invidiously discriminatory governmental act’

is not ‘immunized by the absence of such discrimination in the

making of other comparable decisions’.” 476 U.S. at 95 (quoting

Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at 266, n.14).

16

(i) Isabella Thomas was purportedly challenged be

cause she had “problems” following the law of circum

stantial evidence. Supp. R. vol. 1, 109. The trial court

accepted this rationale without the slightest attention to

its adequacy. When tested, the proffered explanation is

plainly insufficient to overcome the defendant’s prima

facie inference. First, at the time the strike was exer

cised the prosecutor’s case was based on direct evidence.

(J.A. 68.) Hence, the law of circumstantial evidence was

not relevant or sufficiently correlated to the case to be a

proper basis for challenge. Second, Ms. Thomas’ problem

atic responses were elicited through the prosecutor’s own

confused hypothetical; when the questions were clarified,

Thomas Responded without problem.15 16 Finally, similarly

situated white veniremembers also responded with diffi

culty to questions pertaining to the laws of circumstan

tial evidence, intent and causation, but went unchal

lenged. R. vol. 11, 1550-53; R. vol. 6, 316-19; R. vol.

15, 2261-65.

(ii) Leroy Green was purportedly challenged because

he was a postal employee, and because he responded non

verbally. Supp. R. vol. 1, 208-18. Again, this explana

tion does not even come close to meeting Batson’s re

quirements. The prosecutor never explained how postal

employees as a group were biased, in what way Green

shared that bias or how any such bias was related to the

case. Indeed, no such explanation is logically possible.18

16 The prosecutor asked Ms. Thomas whether she could find some

one guilty of burglary if he was caught several days after the crime

with the victim’s property. Ms. Thomas responded negatively.

After further explanation, she responded that she could if “shown

all the possibilities beyond a reasonable doubt.” R. vol. 9, 1006-11.

16 Neither of the Texas courts who considered this rationale

found it plausible. Although the appellate court found that Green

“was . . . struck solely . . . because he had been an employee of the

United States Postal Service for some thirteen years . . .” (J.A.

70-71), the trial judge omitted all reference to this part of the

State’s explanation from its “ Findings of Fact and Conclusions of

Law.” (J.A. 49.)

17

The remainder of the State’s explanation cannot be con

sidered race-neutral, since similarly situated white ve-

nirepersons were not challenged even though they also

responded to questions nonverbally.17

(iii) Frank Samuel was purportedly challenged be

cause he appeared to be illiterate, a conclusion based on

the prosecutor’s suspicion that his data sheet might have

been filled out by another person, and because he re

sponded to three questions by nodding. Supp. R. vol. 1,

135-43. This explanation is plainly insufficient. First,

nearly a dozen unchallenged white veniremembers also

responded nonverbally to examination.18 Second, Samuel

was never questioned directly on the subject of his liter

acy or about the data sheet. Indeed, at the Batson hear

ing the prosecutor acknowledged that Mr. Samuel could

read when asked to do so at voir dire. Supp. R. vol. 1, 138.

Further, the prosecutor undermined the veracity of this

rationale by disputing, in another context, the impor

tance and verifiability of the same questionnaire. Supp.

R. vol. 1, 71.

The trial court, when faced with explanations that were

clearly implausible or suggestive of bias, inexplicably

failed to recognize its obligation to assess the legitimacy

of these justifications. Rather than pursue further in

quiry, or engage in a serious evaluation of their suffi

ciency, the court blindly accepted the explanations at face

value. In so doing, the court woefully failed to meet the

legal standard set forth in Batson. 17 18

17 Nonverbal responses from unchallenged venirepersons are

scattered throughout the voir dire transcript. Charles Yana, R. vol.

11, 1469, 1472; Denise Hollingsworth, R. vol. 11, 1544-47, 1556, 1565,

R. vol. 12, 1590; William Wright, R. vol. 12, 1761-62, 1773; Sharon

Miller, R. vol. 16, 1827-28, 1832, 1834, 1838, 1842-43, 1846; Carol

Moore, R. vol. 16, 1885-86, 1890-91, 1903, 1917; Peggy Whitley, R.

vol. 5, 172, 179, 186, 189, 192-93; and Curtis Sumrall, R. vol. 7, 500,

571, 588, 664, 672, all responded nonverbally.

18 See supra note 17.

1 8

C. The Trial Court May Consider Only The Prosecu

tor’s Actual Reasons For Challenge

Implementation of Batson presents special problems

where, as here, prosecutors are unable to recall the pre

cise basis for a suspect challenge. In Tompkins, the

Batson hearing was held six years after the original

voir dire. Situations such as these are particularly ripe

for speculative, equivocal, and possibly disingenuous ex

planations.

The only satisfactory rebuttal of a prima facie show

ing of discriminatory purpose is testimony by the prose

cutor of his actual, nonracial reason or reasons for

peremptorily challenging the venireperson. Under Bat

son, a prosecutor must offer an “ explanation of his

legitimate reasons’ for exercising the challenge.” 476

U.S. at 95 n.20 (quoting Texas Dept, of Community

Affairs v. Bur dine, 450 U.S. at 258). This standard is

meaningless unless the prosecutor is obligated to present

his actual reasons, and not simply his best guess. Ex

planations formulated in hindsight and composed largely

of speculation or impressionistic reasoning cannot, as a

general matter, fulfill the Batson obligations.

A trial court’s invitation to speculate concerning facts

of which the prosecutor has no honest recollection cannot

fail to encourage calculated responses or selective recall

that may consciously or unconsciously arise from, prej

udice. As Justice Marshall emphasized in Batson, such

reasons may be easily generated, 476 U.S. at 106. Be

cause post hoc reconstructions will, if accepted, inevi

tably erode the safeguards Batson was designed to erect,

this Court should make explicit the logic of Batson that

only by properly explaining its actual motivations may

the State rebut a defendant’s prima facie showing of dis

crimination.

The fact that the Batson hearing in the present case

was fraught with examples of the prosecutor’s specula

19

tive reasoning18 * thus provides an independent ground

for reversal.

HI. THE a p p e l l a t e c o u r t a p p l i e d i n c o r r e c t

STANDARDS OF REVIEW

Batson held that an appellate court should give “ ap

propriate deference” to trial court findings of intentional

discrimination. 476 U.S. at 98 n.21. The Texas Court

of Criminal Appeals, however, was blindly deferential in

this case to the trial court’s finding that the State did

not challenge any of five black venirepersons based on

their race. Because the trial court’s findings are deter

minative of petitioner’s equal protection claim, this

Court should declare erroneous the appellate court’s lax

review of those findings.20

10 For instance, when the prosecutor was asked whether she

could recall why she asked a particular question of a challenged

venireperson, the prosecutor responded: “No, I can just go on what

it indicates from the questions and what I asked and the answers

I got and from what I asked him here, which was unusual for me

to ask, I have to assume there was a reason I asked it and that is

the type of thing I would have asked if I were getting nonverbal

communications coming from the person in the witness box.” Supp.

R. vol. 1, 224. Later, when asked why nonverbal responses to voir

dire made her inclined to strike a venireperson, the prosecutor

could only respond generally, “ [t]here are all sorts, of reasons, that

are nonverbal that give you a feeling about whether a juror would

make a good juror in your case or how they feel about you or how

you feel about them.” Counsel responded: “ Okay, you just don’t

remember. Is that correct?” ; to which the prosecutor answered

“ Right, and if we had done it at the time . . .” Id. at 225.

20 This Court’s examination of the standards of appellate review

applied by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in this case would

not “unduly interfere with the legitimate activities of the States.”

Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37, 44 (1971). Generally, a state ap

pellate court is free, as a matter of state law, to decide the level of

deference to accord to a trial court’s factual findings. Texas v.

Mead, 465 U.S. 1041, 1044 n.2 (1983) (Rehnquist, J., dissenting

from denial of certiorari). Notwithstanding this freedom, however,

where federal constitutional rights are concerned, a state court is

20

The Court of Criminal Appeals was overly deferential

to the trial court’s findings in two respects. First, the

appellate court failed to review the legal sufficiency of

the trial court’s process for evaluating the legitimacy of

the prosecutor’s explanations, as required by Batson.

Second, the Court of Criminal Appeals improperly ap

plied a “ rational basis” standard in its review of the trial

court’s findings, rather than the more stringent “ clearly

erroneous” standard called for in Batson.

A. The Court Of Criminal Appeals Failed To Review

The Legal Sufficiency Of The Trial Court’s Findings

The court of appeals failed to assure that the trial

court’s ultimate findings of no discrimination reflected

the Batson requirements that the prosecutor’s explana

tions be “ legitimate,” “ neutral” and “ related to the par

ticular case to be tried.” 476 U.S. at 98. As explained

obligated to “ consider federal claims in accord with federal law.”

Schneckloth v. Bustamonte, 412 U.S. 218, 259 (1973) (Powell, J.,

concurring).

Where, as in the context of Batson challenges, the factual find

ings of a state trial court control the outcome of a defendant’s

federal constitutional claims, this Court has insisted on examining

the adequacy of state appellate review. For example, this Court

has independently examined evidence in cases concerning the exclu

sion of blacks from juries. The state appellate court’s review of the

trial court’s fact-finding was closely scrutinized because, as in this

case, the “conclusion of law of a state court as to a federal right

and findings of fact are so intermingled that the latter control the

former.” Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. at 590; see also Whitus v.

Georgia, 385 U.S. at 550. In federal habeas corpus proceedings, 28

U.S.C. §§ 2254(b), (d), federal courts are permitted to review state

appellate court findings of evidentiary sufficiency to assure that

state convictions have been secured in accord with the federal con

stitution. Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307, 323 (1979). Otherwise,

states might attempt to satisfy the “beyond a reasonable doubt”

standard with nothing more than “ a trial ritual.” Id. at 316-17.

Thus, where important constitutional rights are at stake, this Court

may review both the facts found by state courts and the standards

of state appellate review applied to such facts without offending

principles of federalism.

21

above, the trial court must elicit and evaluate, as a pred

icate to its ultimate finding on intent, the prosecutor’s

explanation for each suspect challenge. The trial court’s

failure to conduct this evaluation in terms of the legal

standards established by Batson necessarily invalidated

the ultimate finding, and required the appellate court to

set aside the trial court’s finding that the prosecutor

lacked discriminatory intent.

Deference to a finding of fact is not due where there

has been no “conscious determination” by the trial court

of the existence or nonexistence of critical subsidiary

facts or legal conclusions. Cf. Time, Inc. v. Firestone,

424 U.S. 448, 463 (1976). Moreover, deference to a

state trial court’s factual finding is “ inappropriate where

. . . the trial court’s findings are dependent on an ap

parent misapplication of federal law.” Gray v. Missis

sippi, 107 S. Ct. 2045, 2053 n.10 (1987) (citing Rogers

v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534, 547 (1961)). The trial

court’s findings in this case clearly reflect an erroneous

view of the requirements of Batson, and should have

been set aside on that ground. See Pullman-Standard

v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 287 (1982).

A trial court’s obligation under Batson to find legally

sufficient facts attenuates the degree of deference that a

reviewing court should give to the ultimate finding. Cf.

Bose Carp., Inc. v. Consumers Union of United States,

Inc., 466 U.S. 485, 500 n.16 (1984) (“ The conclusive

ness of a ‘finding of fact’ depends on the nature of the

materials on which the finding is based.” ). Less defer

ence is due when the sufficiency of the trial court’s ulti

mate factual finding is based, in part, on legal conclu

sions.121 In the Batson context, the trial court’s ultimate

intent finding “ is inseparable from the principles through 21 * * *

21 “ [Wjhile ‘what happened’ may be. viewed as a question of

fact, the legal sufficiency of the evidence may be viewed as the

equivalent of a question of law.” Monaghan, Constitutional Fact

Review, 85 Colum. L. Rev. 229, 236 (emphasis in original).

22

which it is deduced,” id. at 501 n.17, and should there

fore be independently reviewed on appeal. Id.

In the present case, the Court of Criminal Appeals did

not properly evaluate whether the trial court’s findings

were legally sufficient.122 In fact, they were not. See dis

cussion, supra, 15-17. Even the Court of Criminal

Appeals recognized that at least one of the prosecutor’s

explanations, while nonracial, was so patently unrelated

to the case as to be “ shocking and totally not under

standable” based on the record. (J.A. 68.) Nevertheless,

apparently believing that it was bound to review only the

trial court’s ultimate factual findings— not the legal

sufficiency of the court’s underlying compliance with the

Batson standards—the appellate court declined to over

rule the court below.

The petitioner’s conviction thus suffers from a whole

sale abdication by the Texas courts of their judicial obli

gation to test the legal sufficiency of a proffered conclusion.

Just as the trial court blindly accepted the prosecutor’s

explanation, so the court of appeals closed its eyes

in undiscerning deference to the trier of fact’s ulti

mate findings. Carried to its logical conclusion, the ju

dicial philosophy of the courts below would allow a pros

ecutor to rebut a prima facie case through mere denial

of discriminatory intent or affirmation of personal good

faith; precisely the result that Batson expressly prohibits.

476 U.S. at 97-98.

B. The Court Of Criminal Appeals Erred By Review

ing The Trial Court’s Findings According To A

“ Rational Basis” Standard, Instead Of The “ Clearly

Erroneous” Standard Required By Batson

Even assuming that the ultimate findings of the trial

court were not legally deficient, the appellate court in

s'2 The error is made all the more obvious by the fact that the

trial court, apparently recognizing the hybrid nature of its Batson

hearing findings, styled them “ Findings of Fact and Conclusions of

Law.” (J.A. 47.)

23

correctly applied a “ rational basis” standard in review

ing the finding that the State’s exercise of its peremptory

challenges was not racially discriminatory. (J.A. 66

n.6A.) That standard would require reversal of the

trial judge’s findings of fact “ only if no rational trier

of fact could have failed to find his factual allegation

true by a preponderance of the evidence.” Id. at 8,

citing Van Guilder v. State, 709 S.W.2d 178 (Tex. Grim.

App. 1985), cert, denied, 106 S. Ct. 2891 (1986); Schues-

sler v. State, 719 S.W.2d 820 (Tex. Grim. App. 1986).

Because such a standard of review does not insure proper

scrutiny of the basis for trial court findings regarding

discrimination, it is inadequate to protect the fundamen

tal rights guaranteed under Batson.

Indeed, this Court suggested in Batson, by referring

to its opinion in Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U.S.

564, 573 (1985), that the appropriate level of appellate

review for Batson findings of purposeful discrimination

was the “ clearly erroneous” standard. Batson, 476 U.S.

at 98 n.21. The clearly erroneous standard requires, at a

minimum, that an appellate court (1) review the entire

record before assessing the validity of a trial court’s fac

tual findings and (2) hold the findings clearly erroneous

when, based on the entire record the reviewing court “ is

left with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake

has been committed.” United States v. United States

Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395 (1948); Inwood Labora

tories, Inc. v. Ives Laboratories, Inc., 456 U.S. 844, 855

(1982). The Court of Criminal Appeals failed to satisfy

either of these requirements.123 23

23 Numerous state supreme courts have adopted the clearly er

roneous standard in reviewing the Batson hearing findings of trial

courts. See, e.g., Ex parte Branch, No. 86-500 slip op. (Ala. May 13,

1988); State v. Alvarado, 410 N.W.2d 118 (Neb. 1987); Johnson v.

State, No. 57,526 slip op. (Miss. May 18, 1988) (en banc). Other

state supreme courts have applied ambiguous standards of review

by referring to the high level of deference owed to trial court find

ings. See, e.g., State v. Jackson, No. 477A87 slip op. (N.C. May 5,

24

1. The Court Of Criminal Appeals Failed To Re

view The Entire Record Before Upholding The

Trial Court’s Findings Regarding The Prosecu

tor’s Intent

The appellate court reviewed the record of this case

selectively, to the detriment of petitioner’s fourteenth

amendment rights. The Court refused to consider the

prosecutor’s disparate treatment of similarly situated

white and black venirepersons during voir dire, despite

defense counsel’s offer of such a comparison. (J.A. 66

n.6A.) The appellate court’s failure to consider such

evidence in the record is plainly contrary to the independ

ent examination of the entire record contemplated by the

clearly erroneous standard of appellate review. Bose,

466 U.S. at 499 (1984). The Court of Criminal Appeals

mistakenly treated defense counsel’s proposed comparison

of evidence already in the record as new evidence. It

thus failed to recognize that analysis of evidence in the

record is well within the obligation of a reviewing court.

See, e.g., Amadeo v. Zant, 108 S. Ct. 1771, 1777 (1988).

The Court of Criminal Appeals’ failure to review the

entire record in this regard was not a harmless proce

dural default ; it was an egregious abdication of its re

sponsibility to safeguard petitioner’s constitutional rights.

Stone v. Powell, 428 U.S. 465, 493-94 n.35 (1976). The

appellate court recognized that defense counsel’s compar

ison of similarly situated white and black venirepersons

“ cast considerable doubt upon the neutral explanations

offered by counsel for the State,” (J.A. 66 n.6A), and

might have “ materially affected the trial judge’s ulti

mate findings of fact” had it been presented at the

Batson hearing. Id. With its head firmly planted in the

1988) (special deference); State v. Gonzalez, 206 Conn. 391 (1988)

(great deference). This growing plethora of state standards can

only be rationalized through the confirmation by this Court that the

clearly erroneous standard is constitutionally required.

25

Texas sand, however, the court observed that “we do not

consider this circumstance in reviewing the trial judge’s

findings in this cause.” Id.

The appellate court’s refusal to consider defense coun

sel’s supplemental brief was not only perversely unjust;

it was also patently illogical in light of the mechanics of

the Batson hearing. The trial judge and defense counsel

did not hear the prosecutor’s race-neutral explanations

for having struck certain venirepersons until the Batson

hearing was held. By effectively requiring the defense

counsel at the Batson hearing spontaneously to analyze

multi-volume voir dire transcripts and to compare simi

larly situated white and black venirepersons vis-a-vis the

prosecutor’s explanation in order to preserve the eviden

tiary question on appeal, the appellate court placed an

impossible burden on defense counsel. To disregard a

compelling presentation of evidence on this basis, absent

some legitimate procedural justification, is both unfair

and impermissible under Batson. 476 U.S. at 96-98.

2. The Court Of Criminal Appeals Failed To Hold

The Trial Court’s Findings Clearly Erroneous,

Despite Its Conviction Thai Those Findings Were

Not Credible

The Court of Criminal Appeals accepted the trial

court’s intent findings even though the court felt, based

on its own review of the record, that certain of the

prosecutor’s race-neutral explanations were not credible.

This unwarranted degree of deference violates the clearly

erroneous standard of review and undermines the degree

of judicial inquiry contemplated by Batson.

As noted above, the record raises serious questions

about the veracity and sufficiency of the prosecutor’s

explanations. The appeals court recognized the apparent

inconsistencies in the trial court’s findings. In the case

of the prosecutor’s strike on grounds that the venireper-

son had problems with the law of circumstantial evi

26

dence, the appeals court described this explanation as

“ shocking and totally not understandable.” (J.A. 68.)

“Without more,” the court continued, “we would have to

hold that only an irrational trier of fact could have ac

cepted this reason as a ‘neutral explanation’ .” Id. None

theless, the court, on its own initiative, supplied further

justification for the strike— that a jury instruction on

circumstantial evidence would still have been a theoreti

cal possibility.2 * * 24 In the case of the prosecutor’s strike on

grounds that the venireperson was a postal employee, the

appeals court was given “great concern” (J.A. 70), be

cause of the “difficulty in understanding the relevancy of

a venireperson’s employment as a postman . . . as far as

2i In the face of implausible and ambiguous facts in the record,

the appellate court impermissibly supplemented the trial court’s

findings by engaging in its own speculation concerning the prose

cutor’s reasons for two of the suspect peremptories. First, with

regard to the venireperson struck because of her reservations about

circumstantial evidence, the appeals court substituted an imputed

motive for the prosecutor’s stated motive for exercising the peremp

tory challenge: “ [W ]e hold that the prosecuting attorney exer

cised a peremptory on the venireperson rather than risk a hung

jury.” (J.A. 70.) Second, the prosecutor struck a venireperson

alleged to be illiterate. Yet it was the Court of Criminal Ap

peals, and not the prosecutor, that attempted to correlate this

explanation to the case by concluding that the case was going to

include “ detailed written jury instructions” (J.A. 70), thus making

the alleged illiteracy a legitimate basis for challenge. In fact, at

the Batson hearing, the prosecutor admitted that the foreman jury

charge was usually read to the jury. Supp. R. vol. 1, 144.

Faced with this clear failure by the State to meet its burden under

Batson, the Court of Criminal Appeals should have moved without

hesitation to set aside the conviction. If it is inconsistent with the

values protected by Batson to allow the prosecution to speculate

concerning his reasons for exercising a suspect peremptory chal

lenge (see discussion, swpra, at 18-19), it is all the more im

permissible for a court of appeals far removed in time, space and

orientation from the event at issue, to substitute its own “best

guess” as to the State’s motive. This error, also, constitutes an

independent cause for reversal.

27

his qualifications for jury service.” (J.A. 71.) However,

the court overlooked not only this grave insufficiency,

but also the fact that the trial court had not even men

tioned the employment issue in its findings (J.A. 49),

and affirmed the legitimacy of the State’s explanation for

the sole reason that it was not race-related. (J.A. 71-

72.)

In light of its stated reservations, the appeals court’s

uncritical deference to the trial court finding on these

venirepersons was wholly unjustified. A reviewing court

must set aside a finding, even if there is some evidence

in the record to support it, when the court feels based

on the entire evidence that a mistake has been made.

Anderson, 470 U.S. at 573; Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. at

395. The Court of Criminal Appeals should have clearly

rejected findings which it found “shocking and totally

not understandable” and the cause for “great concern,”

rather than sustain them on the basis of its own specula

tion or artificially narrow view of the record.

This is no less true where the trial court’s findings is

in part based on a “credibility” determination. See J.A.

65. A witness’ facially credible testimony may be con

tradicted or rendered inconsistent by other evidence.

Anderson, 470 U.S. at 575. Here, the prosecutor’s race-

neutral explanation concerning the venireperson’s hesi

tancy about circumstantial evidence was squarely con

tradicted by the prior admission into evidence of defend

ant’s confession. In such a case, a reviewing court should

find clear error, even though the finding is purportedly

based on a credibility determination. Id. The Court of

Criminal Appeals committed reversible error when it de

clined to act on the glaring contradictions in the record

before it.

2 8

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the Court of Criminal Appeals of

Texas should be reversed and the cause remanded.

Respectfully submitted,

Conrad K. Harper

Stuart J. Land

Co-Chairmen

N orman Redlich

Trustee

W illiam L. R obinson

Judith A. W inston

Lawyers ’ Committee for

Civil R ights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, NW.

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

R obert E. Montgomery, Jr .

Counsel of Record

Erika A. Kelton

Paul, W eiss, R ifkind

W harton & Garrison

1615 L Street, N.W.

Suite 1300

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 223-7300

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae