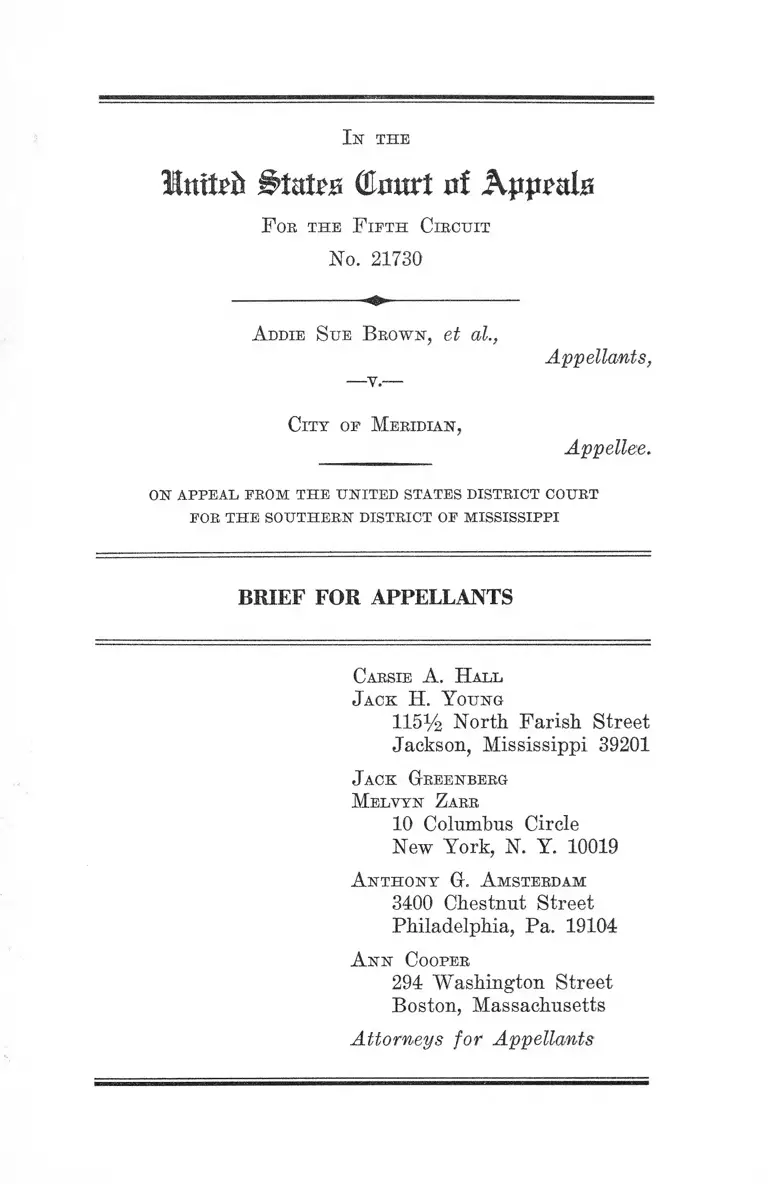

Brown v. City of Meridian Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. City of Meridian Brief for Appellants, 1964. 02d16d9f-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e2a0e47a-52a0-40e4-925b-52ef812887b7/brown-v-city-of-meridian-brief-for-appellants. Accessed March 03, 2026.

Copied!

I n ' T H E

Inttpft Btntm Glmtrt u! Appmlz

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 21730

A ddie Sue Brown, et al.,

Appellants,

City of Meridian,

Appellee.

ON A P PE A L FRO M T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E SO U T H E R N DISTRICT OF M ISSISSIP PI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Carsie A. Hall

Jack H. Y oung

115% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

J ack Greenberg

Melvyn Zarb

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

A nn Cooper

294 Washington Street

Boston, Massachusetts

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ................................... -................. 1

Specifications of Error ...................................................... 6

A rgument

I. This Court Has Jurisdiction to Review the

Remand O rders...................................................... 6

II. Appellants’ Removal Petitions Sufficiently State

a Removable Case Under 28 U. S. C. § 1443(2) 7

A. “ Color of Authority” .......................................... 9

B. “Law Providing for Equal Rights” ............. 14

C. The Acts for Which Appellants Are Prose

cuted ...................................................................... 18

III. Appellants’ Removal Petitions Sufficiently State

a Removable Case Under 28 U. S. C. § 1443(1) 19

A. The State Laws Under Which Appellants

Are Prosecuted Offend the Constitution of

the United States ............................................ 19

B. The Pendency of These Prosecutions in the

State Courts Is Designed to Harass Appel

lants and to Suppress Their First Amend

ment Rights ........................................................ 25

C. The State Courts in Which Appellants Are

Prosecuted Are Hostile to Appellants ......... 27

IV. Appellants’ Removal Petitions Were Timely

Filed .......................................................................... 34

Conclusion.................................................................................. 36

PAGE

Statutory A ppendix

28 U. S. C. § 1443.......................................................... la

28 U. S. C. § 1446....................................................... . la

28 U. S. C. § 1447(d) .................................................. 2a

Miss. Code Ann. 1942, Kec., §2089.5 (1962 Supp.) 2a

Code of Ordinances of the City of Meridian, Sec.

3-1, Sec. 3-2 ...................................................... 3a

Table of Cases

Arkansas v. Howard, 218 F. Snpp. 626 (E. D. xlrk.

1963) .................................................................................. 7

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964) ...................... 25, 26

Braun v. Sauerwein, 10 Wall. 218 (1869) ....... ............... 8

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 IT. S. 110 (1882) .................... ..... 19

Colorado v. Symes, 286 U. S. 510 (1932) ....................... 33

Congress of Racial Equality y. Town of Clinton, No.

20960 (5th Cir., September 22, 1964) ....................... 7

Dienstag v. St. Paul Fire and Marine Ins. Co., 164 F.

Supp. 603 (S. D. N. Y. 1957) .......................................... 35

Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 TJ. S. 157 (1943) ................... 16

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 TJ. S. 229 (1963) ..... ..18, 24

Egan v. Aurora, 365 U. S. 514 (1961) .............................. 16

England v. Louisiana State Board of Medical Exam

iners, 375 U. S. 411 (1964) .......................................... 30

Feiner v. New York, 340 IT. S. 315 (1951) ....................... 26

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 (1963) ...............18, 24

Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U. S. 67 (1953) ................... 16

11

PAGE

111

PAGE

Georgia v. Tuttle, 377 U. S. 987 (1964) ........................... 33

Gibson v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565 (1896) ...............19,24

Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 IT. S. 496 (1939) ........................... 16

Harris v. Pace, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1355 (M. D. Ga.,

November 1, 1963) ........................................................ 22

Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964) ....................... 18, 25

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 (1937) ..... ................. 22

Hillv. Pennsylvania, 183 F. Supp. 126 (W. D. Pa. 1960) 15

Hodgson v. Millward, 12 Fed. Cas. 285 (E. D. Pa. 1863) 8

Hodgson v. Millward, 3 Grant (Pa.) 412 (1863) ........... 8

In re Duane, 261 Fed. 242 (D. Mass. 1919) ................... 35

Jamison v. Texas, 318 U. S. 413 (1943) ........................... 23

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906) ...............19, 20, 23,

26, 28, 33

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 IJ. S. 451 (1939) ............... 22

Lefton v. Hattiesburg, No. 21441 (5th Cir., June 5,

1964) ................................................................................. 34

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938) ............................... 23

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 IT. S. 501 (1946) ....................... 25

Maryland v. Soper, 270 IT. S. 9 (1926) ......................... 33

Monroe v. Pape, 365 IT. S. 167 (1961) .......................16,17, 32

Murray v. Louisiana, 163 IT. S. 101 (1896) ...... ............ 19

N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama ex rel. Flowers, 377 IT. S. 288

(1964) ............................................................................... 16

N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 IT. S. 415 (1963) ....16, 22, 25, 27

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1880) .......................19, 24

Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F. 2d 110 (5th Cir. 1963) ........... 22

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 IT. S. 268 (1951) .............-.... 16

IV

Rachel v. Georgia, No. 21354 (5th Cir., March 12, 1964) 33

PAGE

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 85 (1955) ........................... 29

Schneider v. Irvington, 308 U. S. 147 (1939) ....... ....... 23

Smith v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 592 (1896) ................... 19

Steele v. Superior Court, 164 F. 2d 781 (9th Cir. 1948),

cert, denied, 333 U. S. 861 (1948) .............................. 15

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 IJ. S. 303 (1879) .......19, 25

Talley v. California, 362 IJ. S. 60 (1960) .......................23, 25

Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S. 257 (1879) ......... ............. 19

Valentine v. Chrestensen, 316 U. S. 52 (1942) .............. 23

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313 (1879) ..... ..19, 20, 26, 28, 33

Williams v. Mississippi, 170 TJ. S. 213 (1898) ............... 19

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 (1963) ...................... 22, 25

F edebal Statutes

28 IT.

28 IT.

28 U.

28 U.

28 IT.

28 TJ.

28 U.

28 U.

42 IT.

42 U.

S. C. §74 (1940) ..................... 11,31,35

S. C. §1442(a) (1) ............ 14

S. C. §1443(1) ............................. 14,15,19,21,26,27

S. C. §1443(2) ..........7,8,11,12,14,15,16,17,18,19

S. C. §1446 (a) ...................................................... 34

S. C. §1446 (c) .............................................. 35

S. C. §1446(e) ....................................................... 3,4

S. C. §1447(d) ...................................................... 6,7

S. C. §1981 ............................................................ 32

S. C. §1983 .......................................................... 16,17

V

Rev. Stat. §641 .......................................... 10,11,15,18, 31, 35

Judicial Code §31 (1911) ........................-............. U> 15, 31, 35

Judicial Code §297 (1911) ................................................ 11

Act of September 24, 1789,1 Stat. 7 3 .............................. 31

Act of February 4, 1815, 3 Stat. 195...............................13, 31

Act of March 2,1833, 4 Stat. 632 .................................... 14, 31

Act of March 3,1863, 12 Stat. 755 ..............................9,12,18

Act of June 30, 1864, 13 Stat. 223 .......... ............... -......... 14

Act of March 3, 1865, 13 Stat. 507 .......... ........................ 13

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 2 7 ...................9,12,13,15,

17,18, 31, 32

Act of July 13, 1866, 14 Stat. 9 8 ...................................... 14

Act of July 16, 1866, 14 Stat. 173 ................................... 13

Act of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 140...................-.10,15,17, 32

Act of April 20, 1871, 17 Stat. 13 ....................... 10,16,17,18

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241 ..................... -.... 7

State Statutes and Obdinances

Miss. Code Ann. 1942, Ree., §1202 ................................ 35

Miss. Code Ann. 1942, Rec., §2089.5 (1962 Supp.) ....2,21

Section 3-1, Code of Ordinances of the City of Meridian 23

Section 3-2, Code of Ordinances of the City of Meridian

1, 22

PAGE

VI

Other A uthorities

PAGE

Amsterdam, Note, The Void-for-Vagueness Doctrine in

the Supreme Court, 109 U. of Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960) .... 27

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess..................................... 32

I Farrand, Records of the Federal Convention (1911) 31

The Federalist, No. 80 (Hamilton) ........................ ........ 30

The Federalist, No. 81 (Hamilton) ......... ....................... 30

In t h e

ItttW (tort of Ajtpoalo

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 21730

A ddie Sue Brown, et al.,

Appellants,

—■y.—

City op Meridian,

Appellee.

ON A PPE A L PROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E SO U TH E R N DISTRICT OP M ISSISSIPPI

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement o f the Case

On May 23, 1964, appellant Watson handed leaflets to

Negro pedestrians on a city street in Meridian, Mississippi

(Mimeographed Record 4-5). Mr. Watson acted as a mem

ber of the Mississippi Student Union, a civil rights organi

zation which was attempting to eliminate segregation prac

tices in employment and in public accommodations in the

City of Meridian (M. R. 4). The leaflets urged Negroes

not to make purchases in stores that discriminated against

Negroes in their hiring policies and operated segregated

lunch counters (M. R. 5). Watson did not obstruct the

movement of persons on the sidewalk, and at all times acted

in an orderly manner (M. R. 5). Watson was placed under

arrest and charged with distribution of advertising matter,

in violation of Section 3-2 of the Code of Ordinances of

2

the City of Meridian. (See Statutory appendix, infra,

p. 3a.)

On May 30, 1964, about 12:45 p.m., appellant Hosley,

a participant in the Mississippi Student Union program,

appeared in the vicinity of the Woolworth store on Fifth

Street in Meridian (M. R. 5). Shortly thereafter, a

Meridian police officer approached Hosley and arrested

him for “ interfering with a man’s business” (M. R. 5).

During the afternoon of May 30, appellants Brown, Harris,

Johnson, Jones, Packer, Smith and Waterhouse, all par

ticipants in the Mississippi Student Union program, ap

peared in the same vicinity and conversed with Negro

pedestrians, advising them of the Mississippi Student

Union program (M. E. 5-6). Appellants did not obstruct

the movement of persons on the sidewalk and at all times

acted in an orderly manner (M. R. 5-6). After a time,

appellants left and then reappeared. While appellants

Harris, Packer and Waterhouse were standing on a street

corner, waiting for a traffic light to change, they were

arrested (M. R. 6 ); appellants Brown, Johnson and Smith,

across the street at the time, were also placed under

arrest (M. R. 6). Appellant Jones, president of the local

branch of the Mississippi Student Union, was arrested

while talking with a friend at the Negro lunch counter

in the Woolworth store (M. R. 6-7). All these appellants

were charged with disturbing the peace, in violation of

Miss. Code Ann. 1942, Rec., §2089.5 (1962 Supp.). (See

Statutory Appendix, infra, p. 2a.)

Appellants’ cases were called in the Police Court of

the City of Meridian at 2:00 p.m., June 3, 1964 (M. R.

8). Appellants appeared in person and, by their counsel,

John Due of the Florida bar, moved for a continuance

to enable counsel to adequately prepare the cases (M. R.

3

8). A continuance was granted until 2 p.m., June 10, 1964

(M. R. 8).

Mr. Due was working in association with Carsie Hall of

the Mississippi bar (Supplemental Mimeographed Record

3). On June 6, 1964, Mr. Hall attempted to file in the

United States District Court for the Southern District

of Mississippi a petition for removal covering the prosecu

tions against appellants (S. M. R. 6). The petition was

refused for filing by the District Court on the grounds

that (1) separate removal petitions were required for each

criminal defendant and (2) that the separate removal

petitions were required to be verified by the appellants

(S. M. R. 6). Although believing that these require

ments for filing were not lawful, counsel nevertheless

attempted to comply with them (S. M. R. 6).

At 11:30 a.m., June 10, 1964, several hours before ap

pellants’ trial in the Police Court, Mr. Due presented to

the clerk of the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi, Meridian Division, sepa

rate removal petitions individually verified by appellants

(S. M. R. 7). The clerk refused to file these petitions on

the ground that the petitions were required to be filed in

duplicate (S. M. R. 8). Mr. Due had no knowledge or

notice of such a requirement (S. M. R. 8). He did not

have duplicate copies of the petitions, having prepared,

under pressure of time, only enough copies for filing and

for service under 28 U. S. C. § 1446(e), nor could duplicate

petitions be prepared in the remaining time (S. M. R. 8).

Before the cases were called in the Police Court, Mr. Due,

with the consent of the clerk, left the petitions in her pos

session and personally served notices of removal with

attached petitions on the Meridian city attorney and the

clerk of the Police Court (S. M. R. 8).

4

At 2 p.m., June 10, 1964, appellants’ eases were called

for trial in the Police Court. Mr. Due entered formal

objection to the jurisdiction of the Police Court on the

ground that the lodging of the removal petitions with the

clerk of the District Court and proper service on the

clerk of the Police Court and the city attorney had per

fected removal jurisdiction of the District Court—thereby

ousting the Police Court of jurisdiction under the express

terms of 28 U. S. C. § 1446(e) (S. M. R. 9-10). The objection

was overruled (S. M. R. 10). The cases proceeded to

trial; appellants advanced their numerous constitutional

defenses, which were rejected, and appellants were each

convicted and fined $50.00 (S. M. R. 10).

Subsequently, counsel for appellants prepared, inter alia,

petitions for writ of habeas corpus for submission to the

Honorable William Harold Cox, Chief Judge of the United

States District Court for the Southern District of Missis

sippi, in which Mr. Due set forth under oath the above facts

(S. M. R.).

On June 12, 1964, at 8:30 a.m., Mr. Hall presented the

petitions to Judge Cox (Mr. Hall’s affidavit). Judge Cox

directed Attorney Hall to call the city attorney and stay

the commitment of appellants, which had been scheduled

for later that morning (Mr. Hall’s affidavit).

On June 16, 1964, duplicate petitions were submitted to,

and accepted by, the clerk (M. R. 3).

On June 30, 1964, the City of Meridian moved to remand

the cases to the Police Court, contending that the petitions

for removal had not been timely filed and that a case for

removal under 28 IT. S. C. § 1443 had not been sufficiently

alleged therein (M. R. 14). Appellants responded to the

motions to remand, contending that the petitions had in

fact been timely filed, having been wrongfully refused by

the clerk of the United States District Court prior to the

5

Police Court trial, and that a case for removal under 28

U. S. C. § 1443 had been sufficiently alleged therein (M. R.

15).

On July 13, 1964, a hearing on appellee’s motions to

remand was had before the Honorable Sidney C. Mize,

Judge of the United States District Court for the Southern

District of Mississippi. No affidavits were submitted by the

parties (M. R. 22), but counsel for appellants submitted a

memorandum of law (M. R. 22). Counsel for appellants

treated appellee’s motions to remand— since they did not

controvert any of the factual allegations contained in the

petitions—as in the nature of demurrers testing the suffi

ciency in law of the petitions (M. R. 29). Judge Mize

granted the motions to remand, holding that the removal

petitions had not been timely filed (M. R. 35), and that

they did not state a removal case under 28 U. S. C. § 1443

(M. R. 36). Judge Mize also denied appellants’ motion for

a stay of the remand orders pending appeal (M. R. 40).

On July 14, 1964, appellants offered into evidence one

of the petitions for writ of habeas corpus, setting forth

under oath of Mr. Due the circumstances of the filing of the

removal petitions (M. R. 41). Judge Mize refused to

allow the petition into evidence, on the ground that it was

irrelevant and immaterial (M. R. 41), but allowed it to be

made part of this record (M. R. 42). The orders granting

remand and appellants’ notices of appeal were filed on

July 14, 1964, as well as an order consolidating the cases

for purposes of filing a record on appeal in this court

(M. R. 1).

The orders granting remand stated:

. . . 28 U. S. C. [§]1443 has no application to the

matters alleged and set forth in the petition [s] for

removal (M. R. 17).

6

On July 16, 1964, appellants filed a motion for a stay

pending appeal in this Court.

This Court granted a stay of the remand orders on

July 23, 1964, saying:

The petition for removal in these cases was based

in part on alleged unconstitutionality of certain city

ordinances and thus would warrant the District Court’s

retaining jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. A. § 1443.

Specifications of Error

1. The District Court erred in remanding the cases for

failure of the removal petitions to state a removable

case under 28 U. S. C. § 1443.

2. The District Court erred in remanding the cases for

failure of the removal petitions to be timely filed.

A R G U M E N T

I.

This Court Has Jurisdiction to Review the Remand

Orders.

The present cases were removed from the state court

by petitions filed in June, 1964, relying on 28 U. S. C.

§ 1443. They were remanded on July 14, 1964 and notices

of appeal were filed July 14, 1964. Prior to July 2, 1964,

28 IT. S. C. § 1447(d) read:

An order remanding a case to the State court from

which it was removed is not reviewable on appeal or

otherwise.

7

On July 2, 1964, Congress enacted the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 78 Stat. 241, which provides in § 901, 78 Stat. 266:

Section 901. Title 28 of the United States Code,

Section 1447(d), is amended to read as follows:

An order remanding a case to the State court

from which it was removed is not reviewable on

appeal or otherwise, except that an order remanding

a case to the State court from which it was removed

pursuant to § 1443 of this title shall he reviewable

by appeal or otherwise.

The applicability of the new statute to the present

cases—pending in the District Court at the time of its

enactment, but neither remanded nor appealed until after

the statute took effect—is plain. Congress of Racial

Equality v. Town of Clinton, No. 20960 (5th Cir., Septem

ber 22,1964), and cases cited.

II.

Appellants’ Removal Petitions Sufficiently State a Re

movable Case Under 28 U. S. C. § 1 4 4 3 (2 ) .

Subsection 2 of 28 U. S. C. § 1443 allows removal by a

defendant of any prosecution ‘‘ [f]or any act under color

of authority derived from any law providing for equal

rights” . This provision has seldom been litigated and has

never been construed in its application to circumstances

like those in the present case.1 Appellants here contend:

1 In Arkansas v. Howard, 218 F. Supp. 626 (E. D. Ark. 1963),

removal was sought of prosecutions for assault with intent to kill

and for carrying a knife, charges arising out of a fight between the

defendant and a white student after rocks were thrown at the

station wagon in which defendant was escorting home from school

8

(A) That an act is under “ color of authority” of law

if it is done in the exercise of freedoms protected by that

law;

(B) That 42 IT. S. G. § 1983 is a “ law providing for

equal rights” and protects, inter alia, acts in the exercise

of freedom of speech to protest racial discrimination; and

(C) That appellants are being prosecuted for such pro

tected acts.

two Negro students (one, defendant’s niece) who had that day

been enrolled under federal court order in a previously segregated

school. Defendant invoked §1443(2) on the theory that in escort

ing the children and in protecting himself and them from persons

who sought to frustrate enrollment, he was acting under color of

authority derived from the Civil Rights Act of 1960, under which

the enrollment order was made. The District Court assumed argu

endo that in some circumstances removal under §1443(2) was

available to a private individual charged with an offense arising out

of his act of escorting pupils to a school being desegregated under

federal court order, but held that this defendant, in his knife fight

with the white student, was not implementing the court’s integra

tion order, since that order made no provision for transporting or

escorting the children to school (in light of the previously peaceful

history of the school controversy, by virtue of which, prior to the

day of enrollment, there was no reason to anticipate violence) ;

hence there was no “proximate connection,” 218 F. Supp. at 634,

between the court’s order and defendant’s fight.

In Hodgson v. Millward, 12 Fed. Cas. 285 (E. D. Pa. 1863), ap

proved in Braun v. Sauerwein, 10 Wall. 218, 224 (1869), Justice

Clifford held that a sufficient showing of “color of authority” was

made to justify removal under the 1863 predecessor of 28 U. S. C.

§1443(2) where it appeared that the defendants in a civil trespass

action, a United States marshal and his deputies, seized the plain

tiff’s property under a warrant issued by the federal district attor

ney, purportedly under authority of a Presidential order, notwith

standing that the order might have been invalid. For the facts of

the case, see Hodgson v. Millward, 3 Grant (Pa.) 412 (Strong, J.

at nisi prim, 1863). This ease establishes the proposition that

“color of authority” may be found where a federal officer acts under

an order which is illegal. But it does not advance inquiry as to

whether “ color of authority” exists in any other than the evident

case of a regular federal officer acting under express warrant of his

office.

9

A. “ Color of Authority

On its face, the authorization of removal by a defendant

prosecuted for any act “under color of authority derived

from” any law providing for equal civil rights might mean

to reach (a) only federal officers enforcing the civil rights

acts, (b) federal officers enforcing the civil rights acts

and also private persons authorized by the officers to

assist them in enforcing the acts, or (c) federal officers

and persons enforcing or exercising rights under the civil

rights acts. Legislative history supports the third con

struction.

In 1863, Congress enacted the first removal provision

applicable to other than revenue-enforcement cases. The

Act of March 3, 1863, 12 Stat. 755, was a Civil War meas

ure. It undertook principally to authorize Presidential

suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, and to immunize

from civil and criminal liability persons making searches,

seizures, arrests and imprisonments under Presidential

orders. Section 5, 12 Stat, 756, allowed removal of all

suits or prosecutions “ against any officer, civil or military,

or against any other person, for any arrest or imprison

ment made, or other trespasses or wrongs done or com

mitted, or any act omitted to be done, at any time during

the present rebellion, by virtue or under color of any

President of the United States, or any act of Congress.”

This was the predecessor of the removal provision of the

Civil Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27:

Sec. 3. And be it further enacted, That the district

courts of the United States, within their respective

districts, shall have, exclusively of the courts of the

several States, cognizance of all crimes and offences

committed against the provisions of this act, and

also, concurrently with the circuit courts of the United

States, of all causes, civil and criminal affecting per

10

sons who are denied or cannot enforce in the courts

or judicial tribunals of the State or locality where

they may be any of the rights secured to them by the

first section of this act; and if any suit or prosecution,

civil or criminal, has been or shall be commenced in

any State court, against any such person, for any

cause whatsoever, or against any officer, civil, or mili

tary, or other person, for any arrest or imprisonment,

trespasses, or wrongs done or committed by virtue

or under color of authority derived from this act or

the act establishing a Bureau for the relief of Freed-

men and Refugees, and all acts amendatory thereof,

or for refusing to do any act upon the ground that it

would be inconsistent with this act, such defendant

shall have the right to remove such cause for trial to

the proper district or circuit court in the manner

prescribed by the “ Act relating to habeas corpus and

regulating judicial proceedings in certain cases,” ap

proved March three, eighteen hundred and sixty-three

and all acts amendatory thereof . . .

The 1866 provision was reenacted by reference in the

second civil rights act (Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870,

16 Stat. 140, 144), and, as affected by the third civil rights

act (Ku Klux Act of April 20, 1871, 17 Stat. 13), became

Rev. Stat. § 641:

Sec. 641. When any civil suit or criminal prosecu

tion is commenced in any State court, for any cause

whatsoever, against any person who is denied or can

not enforce in the judicial tribunals of the State, or

in the part of the State where such suit or prosecution

is pending, any right secured to him by any law pro

viding for the equal civil rights of citizens of the

United States, or of all persons within the jurisdiction

11

of the United States, or against any officer, civil or

military, or other person, for any arrest or imprison

ment or other trespasses or wrongs, made or com

mitted by virtue of or under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights as aforesaid,

or for refusing to do any act on the ground that it

would be inconsistent with such law, such suit or

prosecution may, upon the petition of such defendant,

filed in said State court, at any time before the trial

or final hearing of the cause, stating the facts and

verified by oath, be removed, for trial, into the next

circuit court to be held in the district where it is

pending. Upon the filing of such petition all further

proceedings in the State courts shall cease, and shall

not be resumed except as hereinafter provided . . .

In 1911, in the course of abolishing the old circuit courts,

Congress technically repealed Rev. Stat. §641 (Judicial

Code of 1911, Sec. 297, 36 Stat. 1087, 1168) but carried its

provisions forward without change (except that removal

jurisdiction was given the district courts in lieu of the

circuit courts) as Sec. 31 of the Judicial Code (Judicial

Code of 1911, Sec. 31, 36 Stat. 1087, 1096). Section 31

verbatim became 28 U. S. C. § 74 (1940), and in 1948, with

changes in phraseology, the removal provision assumed its

present form as 28 U. S. C. § 1443.

This history indicates that, of the three suggested alter

native constructions of § 1443(2), alternative (a), reading

“ color of authority” as restricted to federal officers, is

untenable. The 1866 Act in terms authorized removal by

“ any officer . . . or other person, for [enumerated wrongs]

. . . by virtue or under color of authority derived from this

act . . . ,” and the language “ officer . . . or other person”

was retained in the Revised Statutes and the Judicial

12

Code of 1911. Both “ officer” and “ person” were dropped

in the 1948 revision, but, as the Revisor’s Note indicates

(“ Changes were made in phraseology” ), no substantive

change in the section was intended. Thus § 1443(2) reaches

“ persons” other than “ officers” .

This history also requires rejection of alternative (b),

which would restrict that class of “ persons” to persons

authorized by federal officers to assist in the enforcement

of the civil rights acts. The strongest argument for such a

restriction of removal would be that the 1866 act desig

nated as removable any suit or prosecution of officers or

persons “for any arrest or imprisonment, trespasses, or

wrongs done or committed by virtue or under color of

authority derived from this act or the act establishing a

Bureau for the relief of Freedmen and Refugees, and all

acts amendatory thereof . . .” (emphasis added). This

language might on its face seem directed to actions arising

from law enforcement activity rather than to actions aris

ing from the exercise of the rights given by the law. The

language is patterned on the identical phraseology of the

1863 habeas corpus act, 12 Stat. 755, where the authori

zation of removal of actions against officers or persons

“ for any arrest or imprisonment made, or other trespasses

or wrongs done or committed, or any act omitted to be

done, at any time during the present rebellion, by virtue

or under color of any authority derived from or exercised

by or under the President of the United States, or any act

of Congress” pretty clearly was addressed to actions aris

ing from arrests, seizures and injuries performed by Union

officers and persons acting under them.

However, although the 1866 act adopted the basic frame

work of the act of 1863, it is evident that it adopted it for

other and broader purposes. Whereas the 1863 legisla

tion was concerned principally with protecting Union offi

13

cers in their conduct of wartime activities, and gave no

rights or immunities to private individuals, the later

statutes to which the 1866 act refers—the 1866 Civil Eights

Act itself, the Freedmen’s Bureau Act of March 3, 1865,

13 Stat. 507, and the amendatory Freedmen’s Bureau Act

of July 16, 1866, 14 Stat. 173 (which was debated by the

1866 Congress as companion legislation to the 1866 Civil

Eights Act)—did grant to private individuals extensive

rights and immunities in the exercise of which it was fore

seeable that “ trespasses or wrongs” might be charged

against them. Section 1 of the 1866 Civil Eights Act, 14

Stat. 27, and Sec. 14 of the amendatory Freedmen’s Bureau

Act, 14 Stat. 176, for example, gave all citizens the right

to acquire and hold real and personal property and to

full and equal benefit of all laws for the security of person

and property. In the exercise of self-help to defend their

property or to resist arrest under discriminatory state

legislation, citizens exercising their federally-granted

rights would doubtlessly commit acts for which they might

be civilly or criminally charged in the state courts. By

Section 3 of the 1866 Civil Eights Act, Congress meant to

authorize removal in such cases, and not merely in cases

in which the freedmen acted under the authority of a

federal officer. This appears clearly from the absence of

any words of limitation in the allowance of removal of

actions against any person for “ wrongs done or committed

by virtue or under color of authority derived from” the

various acts granting civil rights.

When Congress wanted in removal statutes to limit

“persons” acting “ under color of” law or authority to

persons assisting or authorized by a federal officer, Con

gress several times stated this limitation expressly. It did

so in the revenue act of 18152 and again in the revenue

2 Act of February 4, 1815, §8, 3 Stat. 195, 198.

14

act of 1866.3 By the latter, the same Congress which passed

the Civil Rights Act of 1866 limited the broader removal

provisions of the 1833 and 1864 revenue acts.4 Comparison

of the revenue-act removal provisions with those of the

civil rights acts strongly supports the conclusion that the

latter are not limited to persons acting under the directions

of a federal enforcement officer.

Indeed, this interpretation is the only plausible one

under the pattern of removal jurisdiction presently in

force by virtue of the 1948 Judicial Code. Section

1442(a)(1) authorizes removal of suits or prosecutions

against any federal officer or person acting under him for

any act under color of his office, whether in civil rights

cases or otherwise. If the separate removal provision of

§1443(2)—“For any act under color of authority derived

from any law providing for equal rights”—is not entirely

redundant, it must reach cases of action by private in

dividuals not “ acting under” a federal officer in the asser

tion of their civil rights. Since private individuals acting

as such derive authority from federal law only by exer

cising privileges under it, appellants submit that it is

inescapable that § 1443(2) authorizes removal by any per

son exercising rights guaranteed by “ any law providing

for equal rights.”

B. Law Providing for Equal Rights.

It is clear that “ any law providing for equal rights” in

28 IT. S. C. § 1443(2) means the same thing as the language

of Sec. 1443(1): “ any law providing for the equal civil

3 Act of July 13, 1866, §67, 14 Stat. 98,171.

4 Act of March 2, 1833, §3, 4 Stat. 632, 633; Act of June 30, 1864,

§50, 13 Stat. 223, 241.

15

rights of citizens of the United States, or of all persons

within the jurisdiction thereof.” 5

Cases may be found holding that the only right protected

by this latter language is the right of equal protection of

the laws.6 Even under such a restrictive view, the removal

petitions filed by appellants adequately state a case for

removal, for they allege both (a) that the prosecution of

appellants has the purpose and effect of harassing them

and unequally depriving them of their right of free ex

pression—that is, of diserirninatorily denying them their

rights to speak, assemble and protest grievances (M. R.

5 As originally enacted by Sec. 3 of the 1866 Civil Rights Act,

the provision authorized removal by any persons who could not en

force in the state courts “any of the rights secured to them by the

first section of this act” and also by officers or persons for wrongs

done under color of authority “ derived from this act or the act

establishing a Bureau for the relief of Freedmen and Refugees, and

all acts amendatory thereof.” Sections 16 to 18 of the Act of May

31, 1870, 16 Stat. 140, 144, slightly extended the civil rights pro

tected by Sec. 1 of the 1866 Act and provided that the rights thus

created should be enforced according to the provisions of the 1866

Act. In the Revised Statutes, §641, the removal provision extended

to any person who could not enforce in the state courts “any rights

secured to him by any law providing for the equal civil rights of

citizens of the United States, or of all persons within the jurisdic

tion of the United States,” and to officers or persons charged with

wrongs done under color of authority “derived from any law pro

viding for equal rights as aforesaid.” These two removal authoriza

tions (now respectively subsections (1) and (2) of Sec. 1443)

appeared in the 1911 Judicial Code, §31, 36 Stat. 1087, 1096, exactly

as they had appeared in the Revised Statutes, with the “ color of

authority” passage referring explicitly back to the “as aforesaid”

laws described in the “cannot enforce” passage. Omission of “ as

aforesaid” in the 1948 revision effected no substantive change, for

as indicated by the Revisor’s Note, the 1948 revision intended only

“ Changes . . . in phraseology.”

6 Steele v. Superior Court, 164 P. 2d 781 (9th Cir. 1948) (alter

native ground), cert, denied, 333 U. S. 861 (1948) ; Mill v. Penn

sylvania, 183 P. Supp. 126 (W. D. Pa. 1960).

1G

8-9),7 and (b) that their prosecution has the purpose and

effect of suppressing the exercise of free speech to protest

racial discrimination in the City of Meridian (M. E. 8-9).8

However, the pertinent statutes are persuasive that the

statement of an equal protection claim is not a requisite to

invoking § 1443, and that free speech and other due process

claims are rights “ under any law providing for the equal

civil rights of citizens of the United States, or of all persons

within the jurisdiction thereof” (§1443(2)).

42 U. S. C. § 1983 provides that “ Every person who,

under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom,

or usage, of any State or Territory, subjects, or causes

to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other

person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation

of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the

Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured

in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceed

ing for redress.” This provision, which protects due proc

ess rights,9 including the right of free speech10 derives

from Sec. 1 of the Ku Klux Act of April 20, 1871, 17 Stat.

13, the third civil rights act—clearly, in its history and

7 Supporting such a substantive claim, see Niemotho v. Maryland,

340 U. S. 268, 272 (1951) (adverting to “ The right to equal pro

tection of the laws, in the exercise of those freedoms of speech and

religion protected bv the First and Fourteenth Amendments . . . ” ) ;

cf. Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496 (1939) ; Fowler v. Rhode Island,

345 U. S. 67 (1953).

8 Supporting such a substantive claim, see N. A. A. C. P. v. But

ton, 371 U. S. 415, 428-431 (1963) ; N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, ex

rel. Floivers, 377 U. S. 288, 307-309 (1964).

9 Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961).

10 Egan v. Aurora, 365 IT. S. 514 (1961) ; Douglas v. Jeannette,

319 U. S. 157, 161-162 (1943) (relief denied on other grounds);

Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496, 518, 527 (1939) (opinion of Justice

Stone).

17

purposes, a “ law providing for . . . equal civil rights.” 11

This, as a matter of plain language, brings a civil rights

demonstrator’s free speech claim, founded on the First

and Fourteenth Amendments and 42 U. S. C. § 1983, and

unaccompanied by ancillary equal protection claims, within

the removal provisions of 28 U. S. C. §1443(2).

Closer inspection of the original statutes is conclusive.

The language (<any law providing for . . . equal civil rights”

first appeared in § 641 of the Revised Statutes, and that

language clearly meant to include not only the rights to

equality assured by the first (1866) and second (1870)

civil rights acts, but also the rights protected by the third

civil rights act (1871), now 42 U. S. C. § 1983.12

11 The history of the 1871 act is extensively discussed in the opin

ions in Monroe v. Pape, supra, note 9.

12 Section 1 of the 1871 act provided:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of

the United States of America in Congress assembled, That any

person who, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regula

tion, custom or usage of any State, shall subject, or cause to be

subjected, any person within the jurisdiction of the United

States to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immuni

ties secured by the Constitution of the United States, shall, any

such law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage of

the State to the contrary notwithstanding, be liable to the

party injured in any action at law, suit in equity, or other

proper proceeding for redress; such proceeding to be prose

cuted in the several district or circuit courts of the United

States, with and subject to the same rights of appeal, review

upon error, and other remedies provided in like cases in such

courts, under the provisions of the act of the ninth of April,

eighteen hundred and sixty-six, entitled ‘An act to protect all

persons in the United States in their civil rights, and to furnish

the means of their vindication’ ; and the other remedial laws of

the United States which are in their nature applicable in such

eases.

The sweeping language “other remedies provided in like cases in

[the federal] . . . courts, under the provisions of the [1866 A ct]”

was broad enough to include the 1866 Act’s removal provisions; and

18

C. The Acts for Which Appellants Are Prosecuted.

Under the construction of 28 U, S. C. § 1443(2) advanced

in the preceding paragraphs, state criminal defendants

prosecuted for acts in the exercise of First Amendment

freedoms may remove their prosecutions to the federal

courts. That appellants’ petitions bring them within the

statute so construed is evident. The petitions allege, and

appellee does not controvert, the fact that appellants are

being prosecuted (1) for communicating to Negro pedes

trians on a public sidewalk the information that certain

stores in the City of Meridian, Mississippi discriminate

aaginst Negroes and (2) for urging the pedestrians not to

patronize those stores. After Edwards v. South Carolina,

372 U. S. 229 (1963), Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44

(1963), and Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964), it is

not to be doubted that such conduct is within the scope of

constitutionally protected freedom of speech.

Of course, in order to establish the jurisdiction of a fed

eral district court on removal, a defendant need not make

out his federal constitutional defense on the merits, and

need not conclusively show that his conduct was protected

by the federal law on which he relies. That defense is the

very matter to be tried in the federal court after removal is

effected. To support federal jurisdiction, it is sufficient that

the acts charged against the defendant be acts “under color

of authority derived from” a federal civil rights law. 28

U. 8. C. §1443(2). (Emphasis added.)

the still more sweeping reference to “ the other remedial law's of the

United States which are in their nature applicable in such eases”

was effective to invoke the removal provisions of the 1863 statute,

upon which those of 1866 were also based. Plainly, the 1871 Act

in terms extended that class of rights in service of which removal

was available, and it was properly on this assumption that the 1873

revision leading to Rev. Stat. §641 proceeded.

19

This has been clear since the earliest application of the

criminal removal statutes in Tennessee v. Davis, 100 U. S.

257, 261-62 (1879). In short, sidewalk communication is

clearly colorable First Amendment activity.

Hence, appellants submit that their cases are removable

under §1443(2).

III.

Appellants’ Removal Petitions Sufficiently State a Re

movable Case Under 28 U. S. C. §1443 ( 1 ) .

A. The State Laws Under W hich Appellants A re Prosecuted

Offend the Constitution of the United States.

Subsection 1 of 28 U. S. C. § 1443 allows removal of any

criminal prosecution in which the defendant “ is denied or

cannot enforce in the courts of [the] . . . State a right under

any law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States . . . ” Unlike subsection 2, discussed in

Argument II, subsection 1 has several times been before the

Supreme Court of the United States. Strauder v. West Vir

ginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1879); Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313

(1879); Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1880); Bush v.

Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110 (1882); Gibson v. Mississippi, 162

U. S. 565 (1896); Smith v. Mississippi, 162 U. S. 592 (1896);

Murray v. Louisiana, 163 U. S. 101 (1896); Williams v.

Mississippi, 170 U. S. 213 (1898); and Kentucky v. Powers,

201 U. S. 1 (1906). All of these cases involved the claim

that a state criminal defendant held for trial on a murder

charge was denied federal rights under the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by reason of sys

tematic discrimination in the selection of the grand and

petit juries.13 In Strauder, where a Negro .defendant seek

ing removal could point to a statute in force in a state

13 The discrimination complained of in Powers was along political

party lines; in all the other cases it was racial. An additional claim-

20

where he was held for trial expressly restricting eligibility

for jury service to whites, removal was upheld. In the other

cases, from Rives to Powers, the Court found that the state

legislation controlling jury selection was non-discrimina-

tory and even-handed, and that what the defendants com

plained of was systematic discriminatory exclusion of

jurors practiced by jury-selection officials absent sanction

of state constitutional or statutory law. In these cases,

removal was disallowed on the following grounds, stated in

Rives, 100 U. S. at 321-322:

Now, conceding as we do, and as we endeavored to

maintain in the case of Strauder v. West Virginia

(supra, p. 303), that discrimination by law against the

colored race, because of their color, in the selection of

jurors, is a denial of the equal protection of the laws

to a Negro when he is put upon trial for an alleged

criminal offense against a State, the laws of Virginia

make no such discrimination. If, as was alleged in the

argument, though it does not appear in the petition or

record, the officer to whom was intrusted the selection

of the persons from whom the juries for the indictment

and trial of the petitioners were drawn, disregarding

the statute of the State, confined his selection to white

persons, and refused to select any persons of the col

ored race, solely because of their color, his action was a

gross violation of the spirit of the State’s laws as well

as of the act of Congress of March 1, 1875, which pro

hibits and punishes such discrimination. He made

himself liable to punishment at the instance of the

State and under the laws of the United States. In one

sense, indeed, his act was the act of the State, and was

prohibited by the constitutional amendment. But inas-

—state court refusal to honor a state-granted pardon—was ad

vanced in Powers, but that claim presented no genuine issue of a

denial of a federal right.

21

much as it was a criminal misuse of the State law, it

cannot be said to have been such a “ denial or disability

to enforce in the judicial tribunals of the State” the

rights of colored men, as is contemplated by the re

moval act. Sec. 641. It is to be observed that act gives

the right of removal only to a person “who is denied,

or cannot enforce, in the judicial tribunals of the State

his equal civil rights.” And this is to appear before

trial. When a statute of the State denies his right, or

interposes a bar to his enforcing it, in the judicial

tribunals, the presumption is fair that they will be

controlled by it in their decisions; and in such a case a

defendant may affirm on oath what is necessary for a

removal. Such a case is clearly within the provisions

of sect. 641. But when a subordinate officer of the

State, in violation of State law, undertakes to deprive

an accused party of a right which the statute law*

accords to him, as in the case at bar, it can hardly be

said that he is denied, or cannot enforce, ‘in the judicial

tribunals of the State’ the rights which belong to him.

In such a case it ought to be presumed the court will

redress the wrong. . . ”

Under these decisions, the least to which appellants are

plainly entitled is removal of the prosecution insofar as

based upon a state statute or local ordinance which—like

the Strauder statute—is on its face unconstitutional under

a federal law “ providing for . . . equal civil rights.” 14

Miss. Code Ann. 1942, Rec. §2089.5 (1962 Supp.), see

statutory appendix, p. 2a, infra, proscribing disturbance

of the peace, under which all appellants other than appel

« The meaning of the quoted phrase in 28 U. S. C. §1443(1) is

discussed in Argument II B, and appellants’ position is there docu

mented that the language includes a federal law e.g., 42 U. S. C.

§1983, protecting First and Fourteenth Amendment rights.

lant Watson are prosecuted, is invalid under First-Four

teenth Amendment doctrines of vagueness and overbreadth

as developed in Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 (1937);

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 254 (1963); and Harris v.

Pace, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1355 (M. D. Ga., November 1,

1963). This statute does not warn that it punishes merely

the act of communicating one’s views to passers-by on a

public sidewalk; it requires persons such as appellants to

speculate at peril of liberty as to its meaning. See Lan-

zetta v. Hew Jersey, 306 U. S. 451, 453 (1939). The Su

preme Court of the United States has consistently warned

that, where freedom of expression is involved, vague penal

laws cannot be tolerated. N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S.

415, 433 (1963). One important reason for this ban is that

statutes such as § 2089.5 provide law enforcement officers

with a blank check. In effect, § 2089.5 gives a policeman

discretion to arrest any person on a public street whom he

finds offensive. Thus, a person may not only be forced to

relinquish his constitutional right of free speech, but may

also be forced to answer criminally for its exercise. As this

Court recognized in Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F. 2d 110, 121

(5th Cir. 1963):

. . . [L]iberty is at an end if a police officer may with

out warrant arrest, not the persons threatening vio

lence, but those who are its likely victims merely be

cause the person arrested is engaging in conduct which,

though peaceful and legally and constitutionally pro

tected, is deemed offensive and provocative to settled

social customs and practices. When that day comes . . .

the exercise of [First Amendment rights] must then

conform to what the conscientious policeman regards

the community’s threshold of intolerance to be.

Section 3-2 of the Code of Ordinances of the City of

Meridian (see Statutory Appendix, p. 3a, infra, under

23

which appellant Watson is charged), taken alone, seems to

be nothing more than a permissible proscription of com

mercial handbills. See Valentine v. Chrestensen, 316 U. S.

52 (1942). However, taken in the context of the open-ended

definition of “ advertising matter” contained in section 3-1,

see Statutory Appendix, p. 3a, infra, the proscription is

exposed as an indefensible abridgment of the right of free

speech. By these ordinances, the City of Meridian seeks to

make criminal any distribution of any circular or pamphlet

upon a public sidewalk in Meridian. This it may not con

stitutionally do. Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444 (1938);

Schneider v. Irvington, 308 U. S. 147 (1939); Jamison v.

Texas, 318 IT. S. 413 (1943); and Talley v. California, 362

U. S. 60 (1960) (reversing a conviction for distribution of

handbills urging a boycott of stores having racially dis

criminatory hiring policies). As the Supreme Court of

the United States said in Jamison v. Texas, 318 U. S. 413,

416 (1943):

[0]ne who is rightfully on a street . . . carries with

him there as elsewhere the constitutional right to ex

press his views in an orderly fashion . . . by handbills

and literature as well as by the spoken word.

Further, under the rationale of Supreme Court decisions,

all of the charges against appellants are severally remov

able by reason of the showing in the removal petitions that

even those charges which are not unconstitutional on their

face are unconstitutional if applied to make criminal appel

lants’ federally protected conduct. The most restrictive

test of removal, as enunciated in Kentucky v. Powers, 201

U. S. 1 (1906), is whether or not state statutory law dic

tates the federally unconstitutional result complained of in

the removal petition. Under this test, whenever one who is

prosecuted in a state court makes a substantial showing that

the substantive statute under which he is charged is uncon

24

stitutional in its application to him, denying him his fed

eral civil rights, his case is eo ipso removable, notwithstand

ing that he cannot point to any other, procedural provision

of state statutory law which impedes the enforcement of his

rights in the state courts. And for these purposes, it mat

ters not whether the state statute in question is unconsti

tutional on its face (i.e., in all applications) or unconsti

tutional as applied (i.e., insofar as it condemns his fed

erally protected conduct), for in each case it is the statute

which directs the state court to the constitutionally imper

missible result.

It is significant that the whole line of Supreme Court

decisions from Rives to Powers involved claims of denial

of federal rights by reason of an unconstitutional trial pro

cedure, viz., discrimination in the selection of jurors. In

none of these cases did the defendant claim that the sub

stantive criminal statute on which the prosecution was

based was invalid (either on its face or as applied to his

conduct) by reason of federal limitations on the kind of

conduct which a state may punish. Neal v. Delaware, 103

U. S. 370, 386 (1880), and subsequent cases, e.g., Gibson v.

Mississippi, 162 U. S. 565, 581 (1896), explain the Rives-

Powers line as holding that “ since [the removal] . . . section

only authorized a removal before trial, it did not embrace

a case in which a right is denied by judicial action during

the trial . . . ” But a defendant who attacks the underlying

criminal statute as unconstitutional does not predicate his

attack on “ judicial action during the trial.” He says that

if he is convicted at all under the statute his conviction will

be illegal.

Here appellants maintain that their acts of communicat

ing to pedestrians on a public sidewalk information about

racially discriminatory practices may not constitutionally

be punished. Edwards v. South, Carolina, 372 U. S. 229

(1963); Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U. S. 44 (1963);

25

Henry v. Rode Hill, 376 U. S. 776 (1964); Talley v. Cali

fornia, 362 U. S. 60 (1960); Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S.

284 (1963); and N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415

(1963). Thus, irrespective of the procedure forthcoming

at trial (but cf. I l l C, infra), they may not be constitu

tionally punished under the statute and ordinance invoked,

and thus “ cannot enforce in the courts of [the] . . . State”

their federal civil rights.15

B. The Pendency of These Prosecutions in the State Courts

Is Designed to Harass Appellants and to Suppress Their

First Amendment Rights.

The United States Supreme Court has consistently said

that First-Fourteenth Amendment rights occupy a consti

tutionally “ preferred position.” 16 It has recognized that

“ the threat of sanctions may deter their exercise almost as

potently as the actual application of sanctions.” 17 Where

a state defendant petitioning for removal can show a fed

eral court that the prosecution against him is maintained

with the purpose and effect of harassing and punishing him

for the past exercise of these rights, and deterring him and

others similarly situated from the future exercise of these

rights, a particularly strong case for immediate federal

court intervention is made.18

15 Except, of course, that the state court may hold the statute

unconstitutional and enforce appellants’ federal claims. But it is

always possible to say that a state court may do this, and if this

possibility blocks removal, the removal statute is entirely read off

the books. This would require repudiation of Strauder v. West Vir

ginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1879), and rejection of the assumption on

which the Rives-Powers line of cases was decided, viz., that if an

unconstitutional state statute were found, removal would be proper.

16 Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 509 (1946), and cases cited.

17 N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 433 (1963) (voiding a

state statute whose vagueness and overbreadth the Court found

likely to deter the exercise of First Amendment freedoms).

18 See Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964).

26

Removal, which brings before the federal courts at an

early stage the very litigation which the defendant claims

is an instrument for infringing his rights, allows timely

vindication of those rights. Were it otherwise, the defen

dant would likely be disadvantaged during “ an undue length

of time,” 19 while he attempted to assert his rights in un

sympathetic state trial and appellate courts. In cases in

volving free speech, unlike cases of the Rives-Powers type,

the very pendency of prosecution in the state courts denies

the defendant his civil rights, and disables him from enforc

ing them, within the meaning of 28 U. S. C. §1443(1).

Moreover, the essential purpose of removal jurisdiction

—to provide the removing party with a federal trial court

expert in hearing issues of fact underlying federal claims—

has particular application to cases involving First Amend

ment defenses. The scope of First Amendment protection

turns largely on questions of fact, and the power of the

trier of fact to find the facts adversely to defendant is the

power to effectively deprive him of his First Amendment

freedoms. See, e.g., Feiner v. New Torh, 340 IT. S. 315, 319,

321 (1951). When one who is charged with crime for the

exercise of colorable First Amendment freedoms is required

to try the facts in state courts which, as the removal legis

lation recognizes, are likely to be less sympathetic to pro

tect federal freedoms than the federal judiciary, the major

danger is not the existence of state constitutional or statu

tory law, which on its face denies federal constitutional

rights, but the risk of biased or incompetent fact-finding.

Recent Supreme Court development of the void-for-

vagueness doctrine has recognized that a cardinal constitu

tional objection to the vague or overbroad state statute op

erating in the First Amendment area is its susceptibility to

improper application by a trier of fact insulated against

19 Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360, 379 (1964).

27

federal appellate review.20 Historically, Congress has used

the device of federal removal precisely to protect litigants

having preferred federal claims from the risk of hostile

state court fact-finding, which fact-finding not only works

to impede vindication of federal rights of defendants who

actually go to trial in state courts but which also deters

the exercise of those rights by those defendants and others

similarly situated in the future. In any realistic sense,

appellants’ liability to trial in state court for colorable

First Amendment conduct in itself denies them—and makes

them unable to enforce—their federal civil rights within

the meaning of 28 U. S. C. § 1443(1).

C. The State Courts in Which Appellants Are Prosecuted Are

Hostile to Appellants.

Appellants’ removal petitions state that appellants “ are

unable to enforce their federal rights . . . in the courts of

Mississippi, and particularly in the Municipal Court of

Meridian and the Circuit Court of Lauderdale County,

because [those] courts are hostile to [appellants] by rea

20 Striking down Virginia barratry statutes on the ground that

their overbreadth threatened First Amendment guarantees, the

Court in N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415, 432-433 (1963),

wrote: “The objectionable quality of vagueness and overbreadth

does not depend upon absence of fair notice to a criminally accused

or upon unchanneled delegation of legislative powers, but upon the

danger of tolerating, in the area of First Amendment freedoms, the

existence of a penal statute susceptible of sweeping and improper

application.14” ,

Footnote 14 cites: “Amsterdam, Note, The Void-for-Vagueness

Doctrine in the Supreme Court, 109 U. of Pa. L. Rev. 67 (I960).”

The cited note points out (109 TJ. of Pa. L. Rev. at 80) : “ . . . Fed

eral review of the functioning of state judges and juries in the

administration of criminal and regulatory legislation is seriously

obstructed by statutory unclarity. Prejudiced, discriminatory, or

over-reaching exercises of state authority may remain concealed

beneath findings of fact impossible for the Court to redetermine

when such sweeping statutes have been applied to the complex,

contested fact constellations of particular cases.”

28

son of race and by reason of the commitment of those

courts to enforce Mississippi’s policy of racial discrimina

tion” (M. E. 11).

Appellee’s motions to remand do not controvert this

allegation (M. E. 15-16).

Judge Mize held that “ the matters alleged and set forth

in the petition[s] for removal” have “no application” to

28 II. S. C. § 1443 (M. E. 17).

Appellants submit that hostility on the part of a state

court is a sufficient ground for removal to federal court

under 28 U. S. C. § 1443. Thus, appellants submit that

the doctrine of Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906),

should be rejected insofar as it teaches that removal under

§ 1443 is proper only where the removal petitioner claims

an inability to enforce his federal rights in a state court

arising out of the destruction of his rights by the con

stitution or statutory laws of the state wherein the action

is pending.

The doctrine of the Powers case seems the product of a

development which misconceived what was held in Virginia

v. Rives, 100 lT. S. 313 (1879). In Rives, the Court held

that removal was improperly allowed on a petition which

alleged that petitioners were Negroes charged with murder

of a white man; that there was strong race prejudice

against them in the community; that the grand jury which

indicted them and the jurors summoned to try them were

all white; that the judge and prosecutor had refused peti

tioners’ request that a portion of the trial jury be composed

of Negroes; and that, notwithstanding that state laws re

quired jury service of males without discrimination as to

race, Negroes had never been allowed to serve as jurors

in the county. The Court found that these allegations

“ fall short of showing that any civil right was denied, or

29

that there had been any discrimination against the de

fendants because of their color or race. The facts may have

been as stated, and yet the jury which indicted them, and

the panel summoned to try them, may have been impar

tially selected.” Id. at 322. What was wanting as a matter

of pleading (in those early days before experience in the

trial of jury discrimination claims bred the “ prima facie”

showing doctrine of, e.g., Reece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 85

(1955)) was an allegation of purposeful or intentional

discrimination, and the Court said that this might have

been supplied by averment that a statute of the State

barred Negroes from jury service:

When a statute of the State denies his right, or

interposes a bar to his enforcing it, in the judicial

tribunals, the presumption is fair that they will be

controlled by it in their decisions; and in such a case

a defendant may affirm on oath what is necessary for

a removal (100 U. S. at 321).

Thus, the Court thought that the inability to enforce fed

eral rights of which the removal statute spoke “ is pri

marily, if not exclusively, a denial of such rights, or an

inability to enforce them, resulting from the Constitution

or laws of the State, rather than a denial first made mani

fest at the trial of the case.” Id. at 319. But the Court did

not suggest as an inflexible prerequisite to removal that the

bar to effective enforcement of federal rights be statutory.

Nor could it reasonably have done so. The case in which

there exists a state statutory or constitutional provision

barring enforcement of a federal right is the case in which

removal to a federal trial court is least needed. The impact

of such a written obstruction of federal law is relatively

easily seen and dealt with on direct review of the state

court judgment by the Supreme Court of the United States.

30

Where removal is most needed is the case in which the

impingement on federal rights is more subtle, more im

pervious to appellate correction, as where state-court hos

tility and bias warp the process by which the facts under

lying the federal claim are found. As was said in England

v. Louisiana State Board of Medical Examiners, 375 U. S.

411, 416-417 (1964):

How the facts are found will often dictate the de

cision of federal claims. “ It is the typical, not the

rare, case in which constitutional claims turn upon the

resolution of contested factual issues.” Townsend v.

Sain, 372 U. S. 293, 312.

The case in which local prejudice and local resistance

pitch the risk of biased fact-finding strongly against fed

eral claims presents the clearest justification for federal

trial jurisdiction. It is in such situations that Congress

has, from the beginning, authorized removal.21

21 Since the inception of the government, federal removal juris

diction has been progressively expanded by Congress to protect

national interests in cases “ in which the state tribunals cannot be

supposed to be impartial and unbiased” ( T h e F e d e r a l is t , No. 80

(Hamilton)). Hamilton wrote: “ The most discerning cannot fore

see how far the prevalency of a local spirit may be found to

disqualify the local tribunals for the jurisdiction of national

causes . . . ” ( T h e F e d e r a l is t , No. 81 (Hamilton)). In the fed

eral convention Madison pointed out the need for such protection:

Mr. [Madison] observed that unless inferior tribunals were

dispersed throughout the Republic with final jurisdiction in

many cases, appeals would be multiplied to a most oppressive

degree; that besides, an appeal would not in many eases be a

remedy. What was to be done after improper Verdicts in State

tribunals obtained under the biassed directions of a dependent

Judge, or the local prejudices of an undirected jury? To

remand the cause for a new trial would answer no purpose. To

order a new trial at the supreme bar would oblige the parties

to bring up their witnesses, tho’ ever so distant from the seat

of the Court. An effective Judiciary establishment commensu

31

The language and statutory history, as well as the pur

pose, of the 1866 statute which, without change of sub

stance, is present 28 U. S. 0. § 1443, refute any rigid

requirement of civil rights removal being predicated on a

state statute or constitution. Section 3 of the 1866 Civil

Rights Act, 14 Stat. 27, provided that removal might be

had by persons “who are denied or cannot enforce in the

courts or judicial tribunals of the State or locality where

they may he any of the rights secured to them by the first

section of this act.” (Emphasis added.) The reference to

“ locality” suggests that something less than statutory

obstruction to the enforcement of rights was thought to be

sufficient.22 The rights enumerated in Section 1 included

“ full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the

security of person and property, as is enjoyed by white

citizens . . . , any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or

custom, to the contrary notwithstanding.” (Emphasis

rate to the legislative authority, was essential. A Government

without a proper Executive & Judiciary would be the mere

trunk of a body without arms or legs to act or move. I P a r -

b a n d , R e c o r d s o f t h e F e d e r a l C o n v e n t io n 124 (1911).

The Judiciary Act of 1789 allowed removal in specified classes of

cases where it was particularly thought that local prejudice would

impair national concerns (Act of September 24, 1789, §12, 1 Stat.

73, 79-80), and extensions of the removal jurisdiction were em

ployed in 1815 and 1833 to shield federal customs officials (Act of

February 4, 1815, §8, 3 Stat. 195, 198; Act of March 2, 1833, §3, 4

Stat. 632, 633).

22 The “locality” provision was rephrased in Rev. Stat. §641,

which turned removal on the inability to enforce federal rights “ in

the judicial tribunals of the State, or in the part of the State where

such suit or prosecution is pending.” This wording was carried for

ward in §31 of the Judicial Code of 1911, 36 Stat. 1087, 1096, and

appeared in 28 U. S. C. §74 (1940). In the 1948 revision it was

“omitted as unnecessary,” Revisor’s Note, presumably on the theory

that one who may remove from a state court may thereby remove

from the court of any part of the state. The omission tokens no sub

stantive change in the statute.

32

added.)23 24 “ Proceedings” was certainly intended to add

something to “ laws” , and the inclusion of reference to

“ custom” was not inadvertent. Senator Trumbull, who

introduced, reported and managed the hill which became

the aet2i twice told the Senate that it was intended to allow

removal “ in all cases where a custom prevails in a State,

or where there is a statute-law’ of the State discriminating

against [the freedman].” (Emphasis added.)25 Cf .Monroe

v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 (1961). Indeed, the Senator ex

pressly said that it was not the existence of a statute, any

more than that of a custom, that constituted such a failure

of state process as to authorize removal; rather, in each

case, ’whether custom or statute, it was the probability that

the state court would fail adequately to enforce federal

guarantees.26

23 Section 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was reenacted by

Sections 16 and 18 of the Enforcement Act of 1870, 16 Stat. 140,

144. It appeared in Rev. Stat. §1977, now 42 U. S. C. §1981, with

out the “notwithstanding” clause. No intention to effect a substan

tive change appears. The “notwithstanding” clause, although in

dicative of legislative purpose respecting application of the statute,

was not an effective provision, since the Supremacy Clause of the

Constitution made it unnecessary.

24 Introduced, Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 129 (1/5/1866).

Reported, id. at 184 (1/11/1866). Taken up, id. at 211 (1/12/1866).

25 Id. at 1759 (4/4/1866). See id. at 475 (1/29/1866).

26 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1759 (4/4/1866) :

So in reference to this third section, the jurisdiction is given

to the Federal courts of a case affecting the person that is dis

criminated against. Now, he is not necessarily discriminated

against, because there may be a custom in the community dis

criminating against him, nor because a Legislature may have

passed a statute discriminating against him; that statute is

of no validity if it comes in conflict with a statute of the United

States with which it was in direct conflict, and the case would

not therefore rise in which a party was discriminated against

until it was tested, and then if the discrimination was held

valid he would have a right to remove it to a Federal court—

33

There is recent case support for re-examining the doc

trine of Kentucky v. Powers.

Georgia v. Tuttle, 377 U. S. 987 (1964), involved the at

tempted removal under § 1443 of a number of criminal

trespass prosecutions in Atlanta, Georgia. The circum

stances and legal theories of the removal were quite similar

to those in the present case (with the possible difference

that the First Amendment claims and the allegations of

state-court hostility were weaker than those of appellants

here). The federal district court remanded the cases, and

the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit Court stayed

the remand order pending appeal. Rachel v. Georgia, No.

21354 (5th Cir., March 12, 1964). The State of Georgia

petitioned for writs of prohibition and mandamus from the

United States Supreme Court to vacate the stays. On the

last day of the term, the Court denied Georgia’s petition

without opinion.

In view of the Court’s traditional willingness to issue

the prerogative writs, at the instance of a State, to correct

lower federal courts’ improper assumptions of jurisdiction

in criminal removal cases,27 the summary disposition of

Georgia v. Tuttle indicates that the Court had no difficulty

in concluding that the argument for removal was tenable.

or, if undertaking to enforce his right in a State court he was

denied that right, then he could go into the Federal court; but

it by no means follows that every person would have a right