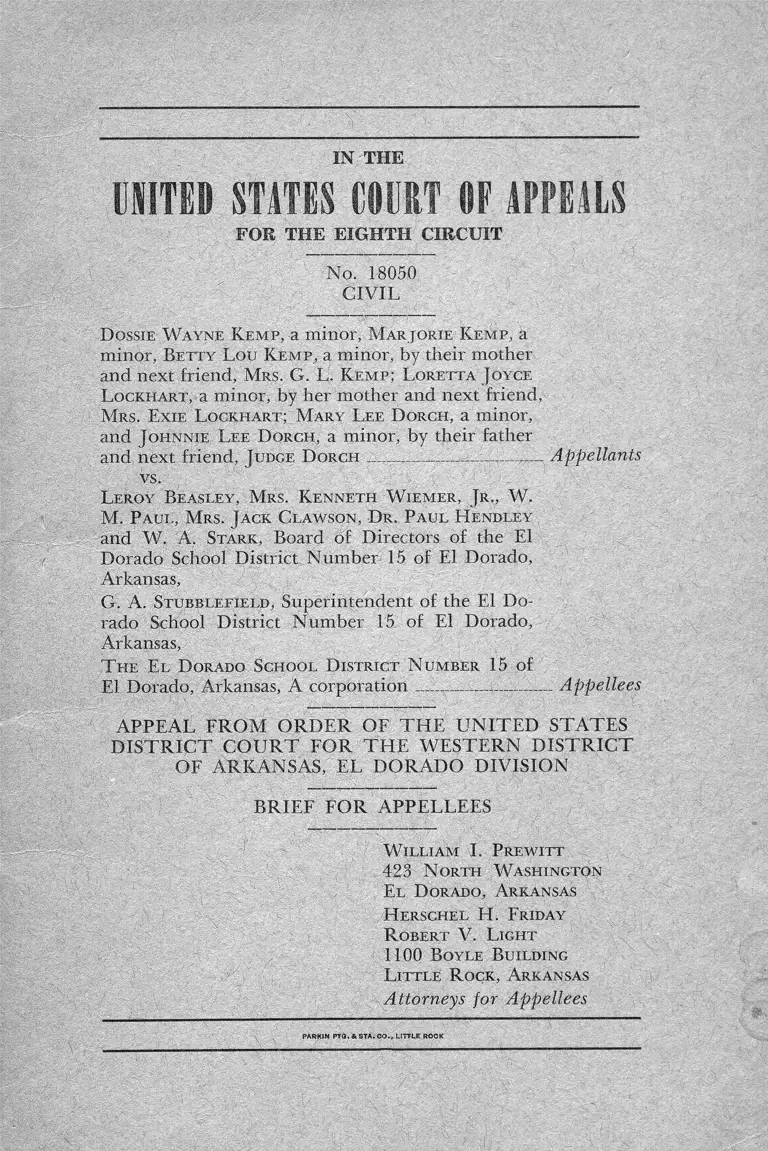

Kemp v. Beasley Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

April 29, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kemp v. Beasley Brief for Appellees, 1965. 122df3da-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e2a25a7e-0721-47b9-9777-568eb7781755/kemp-v-beasley-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

UNITES STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

IN THE

No. 18050

CIVIL

D ossie W ayne K e m p , a m in o r, M a r jo r ie Ke m p , a

m in o r, Betty L ou Ke m p , a m in o r, by th e ir m o th e r

a n d n e x t frien d , M rs. G. L. Ke m p ; L oretta J oyce

L ockhart , a m in o r, by h e r m o th e r an d n e x t frien d ,

M rs. E xie L ock h a rt ; M ary L ee D orch , a m in o r,

a n d J o h n n ie L ee D orch , a m in o r, by th e ir fa th e r

and n e x t friend, J udge D o r c h __________-__ T.—-— Appellants

vs.

L eroy Beasley , M rs. Ken n eth W ie m e r , J r ., W .

M. P aul , M rs. J ack C law son , Dr. P aul H endley

and W. A. Stark , Board of Directors of the El

Dorado School District Num ber 15 of El Dorado,

Arkansas,

G. A. Stu bblefield , Superintendent of the El Do

rado School District Num ber 15 of El Dorado,

Arkansas,

T h e E l D orado Sch o o l D istrict N um ber 15 of

El Dorado, Arkansas, A corporation ___ _— ------Appellees

APPEAL FROM ORDER OF T H E U N ITED STATES

D IST R IC T C O U R T FO R T H E W ESTERN D IST R IC T

OF ARKANSAS, EL DORADO DIVISION

BRIEF FO R APPELLEES

W illia m I. P rew itt

423 N orth W ashington

E l D orado, Arkansas

H erschel H . Friday

R obert V. L ight

1100 Boyle Building

L ittle R ock, A rkansas

Attorneys for Appellees

PARKtN PTQ. & STA. CO. , LITTLE ROCK

I N D E X

Page

Statement of the Case _________________________________ 1

Statement of Points to be A rg u ed _______________________ 5

Argument

I. Appellees’ desegregation plan approved by dis

trict court is consistent with the standards

prescribed by the Supreme court and is not

in conflict with the Civil Rights Act of 1964--------- 6

II. Appellants are not entitled to the award of

attorneys’ fees „ _______________________________ 18

Conclusion _________________________________________ 20

Appendix ____________________________________________ 21

Table of Cases

Bell v. School Board, 321 F.2d 494 (4 Cir., 1963) .... -....... . 18

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, 345

F.2d 310 (4 Cir., 1965) ....-_________ ___-..~ 9, 15, 19

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (1955) ________________ 6

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U.S.

294 (1955) _________ __________________ 4,6, 10, 16, 17

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 LI.S. 263 (1964) ______________ 9

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) _________________ 10, 14

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8 Cir., 1960) _____________ 13

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.2d

988 (10 Cir., 1964) cert d e n ie d ___U .S .______________ 7

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 373 U.S.

683 (1963) _______________________________________ 9

Page

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) ------------------------ - 2

Rogers v. Paul, 345 F.2d 117 (8 Cir., 1965)____ 7, 11, 13, 14, 19

Rogers v. Paul, 232 F.Supp. 833 (1964) --------------------------- 8

Rolax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 186 F.2d 473

(4 Cir., 1951) _____________________________________ 18

Text Books

Barron & Holtzoff, Federal Practice & Procedure, Vol.

3, §1197__________________________________________ 19

Statutes

Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. §2000a,

et seq) _____________________________________ 16, 17, 19

IN THE

IIJITEB STATES COURT I F APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

No. 18050

CIVIL

D ossie W ayne K e m p , a m in o r, M a r jo r ie Ke m p , a

m in o r, Betty L ou Ke m p , a m in o r, by th e ir m o th e r

a n d n e x t frien d , M rs. G. L. Ke m p ; L oretta J oyce

L ockhart , a m in o r, by h e r m o th e r an d n e x t frien d ,

M rs. E xie L ockhart ; M ary Lee D orch , a m in o r,

and J o h n n ie L ee D orch , a m in o r, by th e ir fa th e r

and next friend, J udge D o r c h ___________________Appellants

vs.

L eroy Beasley , M rs. Ken n eth W ie m e r , J r ., W .

M. P a u l , M rs. J ack C law son , Dr. P aul H endley

and W. A. Stark , Board of Directors of the El

Dorado School District Num ber 15 of El Dorado,

Arkansas,

G. A. Stu bblefield , Superintendent of the El Do

rado School District Num ber 15 of El Dorado,

Arkansas,

T he E l D orado School D istrict N um ber 15 of

El Dorado, Arkansas, A co rpora tion______________ Appellees

APPEAL FROM ORDER OF T H E U N ITED STATES

D IST R IC T C O U R T FOR T H E W ESTERN D IST R IC T

OF ARKANSAS, EL DORADO DIVISION

BRIEF FO R APPELLEES

STA TEM EN T OF T H E CASE

This is another school desegregation case. After thorough

exposition of the issues in the district court, the School Board’s

plan for desegregation of the school system was found to con

2

stitute “a prom pt and reasonable start toward ending compul

sory segregation” and was approved.1 O n this appeal the ap

pellants assert that the three-year period comprehended by

the plan to complete the transition from a segregated to a de

segregated system is not fast enough, that the plan is not cal

culated to discharge the Board’s legal obligations, and that the

fees of appellants’ counsel should be assessed against the school

district.

By selective omission of pertinent facts in the record ap

pellants imply in their statement of the case that the Board has

been operating a grossly unequal educational program for

white and Negro students that would not pass muster even

under the test of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537. T he record

does not support the implicaton. For example, they point out

that there are several courses offered in the high school a t

tended by white students that are not offered in the Negro

school. They neglect to m ention that elective courses are

selected on the basis of demand from the students of each

school, and that if as many as ten students request a particular

course the administration endeavors to offer it. (T r. 106-108) .2

Nor do they mention that courses are offered in the Negro

school that are unavailable in the white school. (Interrogatory

No. 33 (c) propounded by plaintiffs). Latin, one of the

courses not offered at the Negro school at the time of the trial,

had previously been offered there and had been dropped due

to lack of demand for it. (Tr. 145). There is no indication

that any of the m inor plaintiffs had made any inquiry about

the unavailability at their school of the courses in which they

professed an interest at trial. (T r. 81).

1 T h e m em orandum opinion of the District C ourt filed A pril 29, 1965 is

unreported. It is reproduced herein as Appendix.

8 T r. refers to the transcript of hearing on January 25, i965. T r. II refers

to the transcript of hearing on April 12, 1965.

3

Appellants point out that enrollment in the Negro ele

mentary schools is 97 per cent of capacity while it is only 70

per cent of capacity at the white elementary schools. Cer

tainly as long as enrollm ent does not exceed capacity in either

group of schools the comparison is not meaningful with respect

to any issue on this appeal. In this connection it should be

noted, however, that the white high school is the most over

crowded building in the system (Tr. 108), and that white

students occupy the three oldest buildings in the District (Tr.

101).

Appellants cite a pupil-teacher ratio of 21 in the white

schools compared to 25 in the Negro schools. T he difference

is obviously minimal, bu t to the extent that instructional qual

ity can be measured statistically it should be noted that the

white high school has a pupil-teacher ratio of 21 and the

Negro high school attended by all bu t one of the m inor plain

tiffs has the more favorable ratio of 16. (Def. Ex. 3).

However, reference to a more meaningful evaluation than

simply counting either teachers’ noses or degrees reveals that

both the Negro and white high schools and junior high schools

have the highest ratings that are conferred by the accrediting

agencies (Tr. 106) and that the salary scales for Negro and

white teachers are identical (Tr. 118) as is the expenditure

per pupil on libraries, supplies, and things of that sort. (Tr.

119).

In summary, the record abundantly supports the proposi

tion that while the schools had been operated on a segregated

basis (there having been no demand from any of the patrons

of the District indicating a contrary desire), the Board and ad

m inistration conscientiously had pursued a policy of providing

4

equal facilities and educational oportunities to all of the stu

dents.

Appellants’ assertion that the Board had taken no steps

to comply with the Brown decision until July, 1964 simply re

flects a misconception of the nature of the legal obligations of

school boards growing out of Brown. This will be fully de

veloped in the argument and it will suffice to say at this

point that the school board has no affirmative legal obliga

tion to mix the races; its obligation is to refrain from dis

crim ination in the form of compulsory segregation based on

race. There is no unlawful discrimination so long as stu

dents choose to voluntarily attend schools, churches or social

functions with others of their own race, and the complete

lack of demand for any desegregation in the El Dorado School

District until July, 1964 reflects that this was essentially the

situation there prior to that date. This is confirmed by para

graph 4 of the district court’s findings of fact filed January 28,

1965.

5

STA TEM EN T OF PO IN TS T O BE ARGUED

I .

APPELLEES’ DESEGREGATION PLAN APPROVED BY

D IST R IC T C O U R T IS CO NSISTENT W IT H T H E

STANDARD PRESCRIBED BY T H E SUPREME C O U R T

AND IS N O T IN CO N FLIC T W IT H T H E CIVIL R IG H TS

A CT OF 1964.

BRADLEY V. SCHOOL BOARD OF CITY OF RICHMOND,

345 F.2d 310 (4 Cir., 1965)

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F.Supp. 776 (1955)

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U.S. 294 (1955)

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U.S. 263 (1964)

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958)

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8 Cir., 1960)

DOWNS V. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF KANSAS CITY,

336 F.2d 988 (10 Cir., 1964) cert denied ____ U.S. ____

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683 (1963)

ROGERS v. PAUL, 345 F.2d 117 (8 Cir., 1965)

Rogers v. Paul, 232 F.Supp. 833 (1964)

Civil Rights Act of 1964

II.

APPELLANTS ARE N O T E N TIT LED T O T H E AWARD

OF A TTORNEY S’ FEES.

Bell v. School Board, 321 F.2d 494 (4 Cir., 1963)

BRADLEY V. SCHOOL BOARD OF CITY OF RICHMOND,

345 F.2d 310 (4 Cir., 1965)

ROGERS v. PAUL, 345 F.2d 117 (8 Cir., 1965)

Relax v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 186 F.2d 473 (4 Cir., 1951)

Civil Rights Act of 1964

Barron & Holtzoff, Federal Practice & Procedures, Vol. 3, §1197

6

A R G U M EN T

I.

APPELLEES’ DESEGREGATION PLAN APPROVED BY

D IST R IC T C O U R T IS CO N SISTEN T W IT H T H E

STANDARD PRESCRIBED BY T H E SUPREM E C O U R T

AND IS N O T IN C O N FLIC T W IT H T H E CIVIL R IG H TS

A CT OF 1964.

T he recurrent theme of appellants’ argument is that the

Board has been derelict in failure to take affirmative action

to desegregate the school system at an earlier date and that it

is therefore to be penalized or punished in this proceeding.

T he penalty suggested is that the appellants be perm itted to

usurp the authority of the Board to assess and solve the prob

lems of desegregation in this District. T h a t this responsibil

ity and authority is vested in the school authorities was ex

pressly recognized in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka,

349 U.S. 294. T he principle was perhaps best expressed in

Briggs v. E lliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 when the three judge dis

trict court said:

“Having said this, it is im portant that we point out exact

ly what the Supreme Court has decided and what it has

not decided in this case. It has not decided that the fed

eral courts are to take over or regulate the public schools

of the states.”

T hus appellants’ basic premise is faulty. T he only charge

of which the Board could be found guilty on this record is

that it failed to take action to affirmatively mix the races prior

to July, 1964, and it was certainly under no legal obligation to

do that. Most courts have considered this point settled since

Judge John J. Parker, one of the giants of American jurispru

dence, said in Briggs v. E lliott, supra, with respect to the

Supreme Court’s in tent in Brown:

7

“It has not decided that the states must mix persons of dif

ferent races in the schools or must require them to attend

schools or must deprive them of the right of choosing the

schools they attend. * * # if the schools which it maintains

are open to children of all races, no violation of the Con

stitution is involved even though the children of different

races voluntarily attend different schools, as they attend

different churches. # # # It (the Constiution) does not

forbid such segregation as occurs as the result of voluntary

action.”

T he better reasoned decisions have consistently followed this

view, and as recently as Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas

City, 336 F.2d 988 (10 Cir., 1964), cert d e n ie d ___U .S .___ , it

was said:

“W hile there sems to be authority to support that conten

tion,3 the better rule is that although the Fourteenth

Amendment prohibits segregation, it does not command

integration of the races in the public schools and Negro

children have no consitutional right to have white chil

dren attend school with them .”

This language was quoted by this Court with approval in

Rogers v. Paul, 345 F.2d 117 (8 Cir., 1965).

Paragraph 4 of the district court’s findings of fact filed

January 28, 1965 to the effect that there had been no demand

on the present or prior members of the Board for any change

in the method of school assignments prior to July, 1964 is

supported by the undisputed proof. W ith total community

acceptance of the school attendance practices, and with no

disorder or even discord to interfere with the orderly conduct

of the school program, the Board would have been chargeable

with dereliction on better grounds than those advanced by ap-

pelants if it had unilaterally undertaken a program of mixing

the races in the schools.

8 In Downs appellants contend that the Board had “a positive and affirm

ative duty to elim inate segregation in fact as well as segregation by in tention .”

8

However, it should be noted that the Board members had

discussed the potential desegregation of the District many times

prior to July, 1964, and as expressed by the president of the

Board: “We recognized this problem, and simply were groping

for an answer as to how to im plem ent the 1954 decision of the

Supreme Court.” (Tr. II 39). T he Board moved promptly

after demand for desegregation was made, and there is ample

support in the record for these findings set out in the district

court’s memorandum opinion:

“* * * the Court finds that the present plan has been

adopted in good faith and in recognition of the fact that

the Board is required to proceed with diligence and in

good faith to pu t an end to racial segregation in the

schools w ithin a reasonable time. As a m atter of fact,

the evidence discloses that the Board was giving serious

consideration to the form ulation of a transitional plan

prior to the filing of this suit.”

W hile there is no suggestion in the record that a demand

for desegregation did not develop earlier because of fears of

any nature on the part of the Negro parents, appellants do

assert that concept in their attack on the freedom of choice

plan, claiming that such fears will lim it the exercise of choices.

In either context the argum ent is entirley unrealistic and ig

nores the patterns of school desegregation that have evolved

in recent years. T he desire to attend school with members of

another race is not universally held, either among Negroes or

whites. In one school district after another only a small m i

nority of the Negro students avail themselves of the opportun

ity to attend with white sudents although they are given a

free and unfettered choice in the matter. I t is such a situa

tion that prompted Judge M iller to rem ark in Rogers v. Paul,

232 F. Supp. 833, 838 (1964) :

9

“It seems clear that the great majority of pupils, white and

Negro, do not desire to attend an integrated school.”

In the case at bar, only 4 Negro students in the first grade, and

7 in the second grade, chose to attend previously all white

schools, although the Board’s plan approved by the district

court gave all Negro students in those grades the right to do so.

Counsel who prosecute these cases against school boards

are also aware of the vast num ber of Negroes who prefer vol

untarily to attend schools with children of their own race. In

Bradley v. School Board of City of R ichm ond, 345 F.2d 310

(4 Cir., 1965) they attacked a freedom of choice assignment

plan because of the substantial num ber of Negroes who, when

given such a choice, elected to attend schools with other Ne

groes. T he Court summarized their position at page 315:

“ # # # plaintiffs insist that there are a sufficient num ber

of Negro parents who wish their children to attend schools

populated entirely, or predominantly, by Negroes to re

sult in the continuance of some schools attended only by

Negroes. T o that extent, they say that, under any freedom

of choice system, the state ‘perm its’ segregation if it does

not deprive Negro parents of a right of choice.”

This absurd contention was, of course, rejected by the Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, sitting en banc. T o the ex

tent that the attack of appellants in the case at bar is directed

to the freedom of choice plan as an appropriate device to dis

charge the Board’s obligation in this field, Bradley is cited as a

well-reasoned, contemporaneous and authoritative decision sus

taining such plans. In so doing, the court understandably draws

support for its conclusion from the language of the Supreme

Court in Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 373 U.S.

683, and from that C ourt’s rem and of Calhoun v. Latimer, 377

U.S. 263.

10

Respecting the other alleged insufficiencies of the plan,

it should be rem embered in the second Brown decision (349

U.S. 294) the Supreme Court recognized that im plem entation

of its prior decision would require the “elim ination of a variety

of obstacles in making the transition to school systems oper

ated in accordance with the constitutional principles” it had

enunciated in the earlier decision. In Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. 1 it said:

“On the other hand, a District Court, after analysis of the

relevant factors (which, of course, excludes hostility to

racial desegregation), m ight conclude that justification

existed for not requiring the present nonsegregated ad

mission of all qualified Negro children.”

I t is clear from these decisions that the district courts are

vested with discretion to be exercised with “practical flexibil

ity” in passing on the sufficiency of desegregation plans in

light of local circumstances. Obviously, there is no set pat

tern, plan or procedure that will guarantee a successful transi

tion w ithin a particular period of time in all localities and

under all circumstances. Thus the determ ination of the dis

trict courts made against a background of intimate knowledge

of the extent to which the “variety of obstacles” exist in a par

ticular school district should be given great weight on appeal.

T he record reflects, and the district judge was no doubt

influenced in approving the plan by, a m ultitude of serious

obstacles to immediate and complete desegregation in this

District. In response to Interrogatory No. 13 propounded by

appellants, the Board named some of these difficulties4, and

d W hat obstacles are there, if any, which will prevent the racially non-

discrim inatory assignment of all students to the El Dorado public schools for

the Septem ber 1965 school term and how?

Such obstacles are innum erable. In the judgm ent of the Board the personal p re

ference of the vast m ajority of the students of the El Dorado School District,

and of their parents, to attend schools where their own race is in the m ajority,

11

listed the disparity between the achievement levels of Negro

and white students at the same grade level as im portant among

them.

T he Superintendent testified respecting this achievement

differential. T he National M erit Scholarship Qualifying Test,

a nationally recognized achievement test, is administered to

eleventh grade students in both high schools each year. (Tr.

110). He testified that the most recently administered tests

reflected a composite score for students in the El Dorado High

School to fall in the 93rd percentile, and a like score for the

students in W ashington High School to fall in the 44th per

centile. (T r. 115). T he difficulties incident to sudden whole

sale mixing of students with such a great disparity of achieve

m ent must be as obvious to the layman as it was to the Super

intendent who testified that it would be wrong from an edu

cational standpoint. (Tr. 127-29). T here can be no doubt as

to his competence to express such an opinion in view of his

service as Superintendent in this District for 21 years. See

Rogers v. Paul, supra.

T he president of the Board testified (Tr. II 36) :

“One of the real problems probably is the lack of achieve

m ent on the part of the m inority race; the record is com

plete—I am not in position to evaluate the cause of the

lack of achievement. It m ight be social, it m ight be eco

nomic, bu t the record indicates that the achievement of

the two races is not equal, and that is one of the truly dif

ficult problems we must solve; and it seems to me by giv

ing these youngsters an opportunity to start at the lower

and the disparity between the achievement levels of negro and white students

at the same grade level, are im portant obstacles in this respect. Also, the ad

m inistrative burden involved in changing the m anner in which students have

been assigned for many years imposes a lim itation upon the extent to which

changes can be made w ithin a given period w ithout disruption of the educa

tional program . Disciplinary problem s peculiar to the negro students, difference

in socio-economic levels of the white and negro students, and lack of support

from m any negro parents for the school program also furnish obstacles to hasty

desegregation.

12

grade they will be better prepared to compete when they

get into the upper grades.”

O n these facts, the conclusion of the witness is inescapable.

It would be a gross injustice to the children of both races to

start the desegregation process anywhere except at the lower

grades.5

» T h e district court recognized the significance of the achievement differ

ential, and the resulting difficulties as evidenced by this exchange with counsel

for appellants (T r. II 48-50):

“T H E C OU RT: Mr. Howard, let me see if I can shorten this pa rt of it a

little for you. Of course, the C ourt has no access to any tests, and has no idea

as to w hat the scores m ight be. I ’ve been sitting in this Division, in this Court

since late 1959 or early 1960. I see - I'm speaking now of negro citizens - I see

some very fine negro citizens here on our juries, people obviously above aver

age in intelligence and achievement. I ’m talking about coming from w ithin the

City of El Dorado and its environments, the County. I see also standing at the

bar in this C ourt some negro citizens, who are almost unbelieveably ignorant.

Now, you’d have a very difficult time, in view of w hat I ’ve seen here, in con

vincing me th a t there is no t a wide disparity, a very wide disparity between

your better educated, professional or semi-professional groups here among the

negro citizens and these people I ’m talking about who are unbelievably ignor

ant. I just know th a t common sense teaches th a t children th a t come from these

homes, th a t latter class of people, will be found to be low in achievement in

their early years because of the background. On the o ther hand, common sense

would teach that the children in the homes of the o ther folks of whom Iv e

spoken ought to achieve in any place they were. Now, you can testify all day

about this. I don’t want to be a rb itrary about it, b u t I think I ’ve seen enough

to know of th a t wide disparity th a t exists here among the negro people. I ’m

no t talking about between the negro and white races, but I think it is clear

from what comes, the parade th a t passes in this very Courtroom, th a t the chil

dren of the one group of which I ’ve spoken w ill achieve at a satisfactory level

in any situation; the children th a t come out of the o ther group of people could

no t be expected to.

Isn’t th a t about w hat the situation is?

MR. HOW ARD: If Your H onor please, let me say this: Here is our point.

T h e fact that there may be generally speaking a low achievement accomplish

m ent, say with the negro children. T h a t would not ru le ou t some negro who

is eligible to attend, and, of course, the p lan of the defendants here is simply

one grade, I mean starting a t the lower grade it would rub out even one of the

plaintiffs here who may have scored high on a test.

T H E COURT: T h a t no doubt is true, bu t what the Court thought you

were talking about a t this time, and the witness was talking about, was the

m atter of the adm inistrative problem s in m aking the change. T h a t is he was

talking about, and I thought you were talking about, adm inistrative problems

in the desegregation at this point, ra ther than whether or not it is hard on one

group or h ard on another, and the C ourt can very well see th a t there would be,

as the witness has testified, problems, particularly w ith this subcultural ̂group

of whom I ’ve spoken, hard to transfer them any place. I ’m not saying it isn’t

harder on the o ther negro children, to go to school w ith them too, I suspect

it is, bu t I can see th a t it would present adm inistrative problems, and num er

ous ones, if you tried to undo the whole m ishmash in one fell-stroke.”

13

T he president of the Board also testified that differences

in the degree of disciplinary problems encountered among

white and Negro students, and the poorer attendance practices

of the Negro students, would present administrative problems

in the desegregation program. (Tr. II 36-7).

As an additional significant factor m itigating against de

segregation of the high school grades at this time it should be

rem embered that the high school attended by white students

is presently the most over-crowded building in the system,

while enrollm ent at W ashington High School is less than the

building’s capacity. (Def. Ex. 3).

It is submitted that the plan adopted by the Board is a

much more certain vehicle to insure that those students who

desire desegregation will obtain it than previous procedures

and plans employed by school districts in Arkansas with the

approval of this Court involving the Pupil Assignment Law

and geographic zoning. U nder the plan here, the Board does

not retain the right to select among qualified applicants as

was the case under the Pupil Assignment Law in Dove v. Par

ham, 282 F.2d 256 (8 Cir., 1960). Here, the pupil whose grade

is desegregated has an absolute right to attend the school of

his choice, subject only to the lim itation of over-crowding the

facility. In the event of overcrowding at the school of his first

choice, he is perm itted to make a second choice.

Nor does the plan here present the potential re-segregation

inherent in geographic zoning plans such as approved in Rogers

v. Paul, supra, resulting in de facto segregation.

Appellants assert that due to their present grade levels,

only one of the m inor appellants will have an opportunity to

attend a desegregated school under the plan. As the district

14

court observes in its opinion, this is not an unusual concomitant

of any transitional plan. T he basic concept of a transitional

plan is the extension of desegregation to a part of the group

or system while temporarily denying it to the whole, in the

interest of achieving an orderly transition. T his result was

expressly recognized and approved in Cooper v. Aaron, 358

U.S. 1.

Objection is also made that the plan affords a choice of

schools to the student only when he enters the school system

for the first time, and again when he is promoted to the next

higher school, i.e. to junior high school and then to high

school. We are confident that this Court will have no more

difficulty than did the district court in concluding that sound

educational and administrative principles require that once a

child has enrolled in a school and become acclimated to its

rules, customs, facilities, faculty and to his fellow students, he

should not be transferred to another school except in over

riding circumstances such as moving his residence nearer an

other school, (provision for this contingency is made in the

Board’s plan) N either should any school district be saddled

with the overwhelming burden on its planing and adminis

trative functions that would result from wholesale transfers

available to every student in the district as a m atter of right

at least once a year as advocated by appellants.

Appellants further objected to the plan because it makes

no provision for desegregation of the teachers, l i r e district

court, noting that the problem was addressed to its discretion

and that were were no teachers who were parties to the suit,

declined to withhold approval of the plan on this ground. This

action was clearly w ithin its discretion recognized by this Court

in Rogers v. Paul, supra. In further support of the district

court’s action we note that the question of teacher assignment

15

was only incidentally touched upon in the hearings in the dis

trict court and the undeveloped record provides no more basis

for judicial action here than it did in Bradley v. School Board

of City of Richm ond, supra. In affirming the district court’s

discretionary refusal to enjoin consideration of race in the

assignment of teachers, that court observed:

“W hen all direct discrimination in the assignment of pu

pils has been eliminated, assignment of teachers may be

expected to follow the racial patterns established in the

schools.”

Objections are made to the plan because of its failure to

treat the questions of budgets, contracts, school construction

sites or plans, extra-curricular activities, and the like. Of

course, it would be impossible to draw a plan that would cover

every conceivable potential problem in this field. T he as

surance that the constitutional rights of all parties will be pro

tected in such matters lies in the action of the district court in

retaining jurisdiction of the cause for the purpose of entertain

ing further proceedings if necessary in the Decree of April 29,

1965.

Appellants also argue that the courts should adopt the

guidelines and policies published by the Office of Education

of the Departm ent of Health, Education and Welfare. Cited

in support of this suggestion are two recent decisions of the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit which are not yet re

ported and are unavailable to counsel at the time of prepara

tion of this brief. We will comment on those decisions more

fully at the time of oral argument, however it should be noted

now that it is quite clear from those portions quoted by ap

pellants that the Court did not regard such guidelines or poli

cies to be in any way binding upon it. Certainly such adm in

16

istrative guidelines are not in any way binding upon any court

in a case like this.

T he Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Act of July 2, 1964, Pub.

L. 88-352, 42 U.S.C. § 2000a.) did not purport to alter the ob

ligations of school boards, or the rights of students, with re

spect to the principles of Brown and the subsequent cases.

T itle IV of the Act entitled Desegregation of Public Education

authorizes the Attorney General to institute suits in the district

courts under certain circumstances, bu t this is simply to en

force rights already spelled out and defined by Brown and its

progeny. T he other provisions of T itle IV authorize a survey,

technical assistance and grants, relating to desegregation and

discrimination in public education, bu t do not purport to af

fect the substantive law as to the obligation of school authori

ties.

T itle VI of the Act (under which the guidelines and poli

cies heretofore referred to were published) is entitled N on

discrimination in Federally Assisted Programs and provides:

“Sec. 601. No person in the U nited States shall, on the

ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from

participation in, be denied the benefit of, or be subjected

to discrimination under any program, or activity receiving

Federal financial assistance.” (emphasis supplied)

T he rem ainder of the T itle deals with the methods of w ith

drawing Federal funds in the event of such discrimination.

T hus it is quite clear that the function of the Office of Edu

cation in the Departm ent of Health, Education and W elfare

involving the sufficiency of desegregation plans of the public

schools relates only to the availability of Federal funds to the

various school districts and other educational facilities.

17

T he guidelines or policies published by that Office are

directed solely to that problem —they don’t purport to usurp

the authority of the courts to determine the constitutional

rights of the interested parties in disputes arising out of the

interpretation of the Constitution in Brown. In that decision

the Supreme Court made it clear that this was a question for

the courts. T he Congress did not undertake to change that

in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It is still a question for the

courts.

Appellants recognize this at page 17 of their brief where

they say:

“However, with the enactment of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, the necessity that all school boards comply with

.the mandate and spirit of the Brown decision became so

clear * # (emphasis supplied).

T hus it is the constitutional principle of Brown, not any new

duty imposed by the Act, with which the school boards must

comply.

W hat may be sufficient as a desegregation plan to satisfy

the courts of good faith im plem entation of Broivn in any par

ticular set of circumstances may not satisfy an administrative

officer in the Office of Education as meeting his Office’s re

quirem ents to qualify for Federal funds. Conversely, a plan

that might qualify a school district for funds in the judgment

of such an adm inistrator may fall far short of meeting consti

tutional standards when tested in the traditional m anner for

the resolution of such issues in the courts.

T he discussion of this point is not expanded because of

confidence that this Court will not abdicate its judicial re

sponsibility in this field concerned with constitutional rights

18

and the vital public interest to administrative employees in

the Departm ent of Health, Education and Welfare.

II.

APPELLANTS ARE N O T E N T IT L E D T O T H E AWARD

OF A TTO R N EY S’ FEES.

At the first hearing in the district court appellants moved

orally for the award of attorneys’ fees, and after calling for

briefs on the question the district court entered an O rder on

February 26, denying the M otion because “the Court is not

persuaded that the conduct of the defendants up to this time

has been such as to justify the award of a fee.”

In support of their application for attorneys’ fees appel

lants cite only two cases, both distinguishable here. In Bell v.

School Board, 321 F.2d 494 (4 Cir., 1963) attorneys’ fees were

awarded to punish conduct and tactics of defendants that the

court regarded as “discreditable.” Exam ination of the conduct

ascribed to the school officials there which, if believed, indi

cates an active program of resistance directed at defeating the

efforts of Negroes seeking admission to previously all white

schools, reveals that there is no parallel to the case at bar.

In Rolax v. Atlantic Coast L ine R. Co., 186 F.2d 473 (4

Cir., 1951) the award of attorneys’ fees was in favor of Union

members against a labor organization that was their bargain

ing agent required to protect their rights, and while in that

capacity entered into a collective bargaining agreement which,

in effect, deprived them of their seniority rights. T he U nion’s

conduct was characterized by the court as “* * * discriminatory

and oppressive.” But, even while holding that the district

court had not abused its discretion in allowing attorneys’ fees,

Judge Parker noted: “Ordinarily, of course, attorneys’ fees ex

19

cept as fixed by statute, should not be taxed as a part of the

costs recovered by the prevailing party; * * *".

Appellants note that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 provides

for the award of attorneys’ fees in suits brought under its public

accommodations provisions. It is more significant for the pu r

poses of this case to note that it contains no such provisions for

suits brought against public school districts.

There can be no quarrel with the general proposition

that in this country it has been thought desirable to require

the litigant for whom legal services are rendered to assume

the burden of paying for those services and that ordinarily at

torneys’ fees are not taxable as costs. See Barron & Holtzoff,

Federal Practice & Procedure, Vol. 3, §1197, p. 65 et seq. Cer

tainly this court is committed to this view as evidenced by

Rogers v. Paul, supra, where the district court’s exercise of dis

cretion in refusing to award attorneys’ fees in a school desegre

gation case was sustained.

T he recent observations of the Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit, sitting en banc, in Bradley v. School Board of

City of R ichm ond, supra, are an excellent summary of current

judicial views on the point:

“ It is only in the extraordinary case that such an award of

attorneys’ fees is reqtiisite. In school cases throughout the

country, plaintiffs have been obtaining very substantial

relief, bu t the only case in which an appellate court has

directed an award of attorneys’ fees is the Bell case in this

Circuit. Such an award is not commanded by the fact

that substantial relief is obtained. Attorneys’ fees are ap

propriate only when it is found that the bringing of the

action should have been unnecessary and was compelled by

the school board’s unreasonable, obdurate obstinacy.

W hether or not the board’s prior conduct was so unreason

able in that sense was initially for the District Judge to

20

determine. Undoubtedly he has large discretion in that

area, which an appellate court ought to overturn only in

the face of compelling circumstances.”

T he discretion of the district court was clearly not abused

in the case at bar.

CONCLUSION

Appellees submit that the Decree of district court of April

29, 1965 approving appellees’ plan of desegregation, and its

denial of appellants’ application for an award of attorneys’ fees,

should be affirmed in all respects.

Respectfully submitted,

W il l ia m I. P r ew itt

423 N orth W ashington

E l D orado, Arkansas

H erschel H . F riday

R obert V. L ight

1100 Boyle Building

L ittle R ock , Arkansas

Attorneys for Appellees

21

A PPEND IX

IN T H E U N IT ED STATES D IST R IC T C O U R T

W ESTERN D IST R IC T OF ARKANSAS

EL DORADO DIVISION

DOSSIE WAYNE KEMP, A Minor, M ARJO RIE^

KEMP, A Minor, BETTY LOU KEMP, A Minor,

by their m other and next friend, Mrs. G. L. KEMP;

L O R E T T A JOYCE LO CK H A RT, A Minor, by

her mother and next friend, MRS. EXIE LOCK

H A R T; MARY LEE DORCH, A M inor, and

JO H N N IE LEE DORCH, A M inor, by their father

and next friend, JUDGE D O R C H ______Plaintiffs

v.

LEE ROY BEASLEY, MRS. K EN N ETH W IEM-

ER, JR ., W. M. PAUL, MRS. JACK CLAWSON,

DR. PAUL HENLEY and W. A. STARK, Board of

Directors of the El Dorado School District Num ber

15 of El Dorado, Arkansas

G. A. STUBBLEFIELD, Superintendent of the El

Dorado School District Num ber 15 of El Dorado,

Arkansas

T H E EL DORADO SCHOOL D IST R IC T N U M

BER 15 of EL DORADO, ARKANSAS, A Cor

poration ------------ ---------------------------- Defendants

M EM ORANDUM O PIN IO N

This desegregation case involves the public schools of El

Dorado, Arkansas.1 T he cause is now before the Court on

the School Board’s amended, substituted, and revised transi

tional plan of desegregation and the objections of plaintiffs

thereto. T he case has been tried to the Court, and this

1 Defendants are Independent School District No. 15, El Dorado, Arkansas,

the members of the Board of Directors of said District, and the Superintendent

of Schools.

CIVIL

> NO.

E.D.I048

22

mem orandum incorporates the C ourt’s findings of fact and

conclusions.

T he El Dorado Schools have always been operated on a

racially segregated basis with separate schools being provided

for white students and Negro students. T he schools for white

students have been staffed exclusively by white principals and

teachers, and the faculties of the Negro have been composed

entirely of Negroes. T he administrative staff of the system

has been made up entirely of white persons, and the school

bus system of the District has been operated on a racially segre

gated basis.

In July 1964 parents of certain of the individual plaintiffs

requested that their children be assigned to schools for white

students for the current school year. T he Board after giving

those requests careful consideration denied them, and this suit

was commenced. T he object of the suit is to bring about

compete desegregation throughout the entire school system,

including desegregation of the faculty and administrative

staff and the bus service.

Following a hearing held at El Dorado on January 25, of

the current year, the Court entered a decree on January 28

declaring that the existing system of racially segregated schools

being m aintained by the District is unconstitutional in the

light of the holding of the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board

of Education, 349 U.S. 294, and enjoining the defendants

“from m aintaining and operating racially segregated schools

in the defendant District.” T he defendants were also enjoined

mandatory “to eliminate with all deliberate speed and within

a reasonable time the existing racial segregation of students

in the public schools.” However, the decree provided that if

the defendants should desire to submit a transitional plan for

23

the elim ination of segregation, a proposed plan might be sub

m itted not later than March 1, 1965.

W ithin due time the Board filed its original plan, and the

plaintiffs objected to it on a num ber of grounds. T he m atter

was set down for hearing on April 12. At the opening of

Court on that day the Board tendered an amended and sub

stituted plan which was more liberal in certain respects than

the original plan, and which met, at least to some extent,

some of the objections of plaintiffs to that plan.2 T he hearing

proceeded as scheduled with plaintiffs being given leave to

file formal objections to the new plan w ithin a few days after

the conclusion of the hearing, and they did so.

T he plan presented to the Court on April 12, while per

haps ambiguous in certain respects, provided in substance for

the elim ination of segregation over a period of six years starting

with grades 1 and 2 at the commencement of the 1965-66 term.

W hen the plaintiffs renewed their objections, the Board re

vised the plan again, and now proposes to eliminate segrega

tion of the student body in a m anner to be described over a

three year transitional period. It is this particular revised

plan which is now before the Court.

T he plan provides that public notice of its provisions is

to be given by publication in a newspaper once a week for

two consecutive weeks with the first publication to be at least

14 days prior to pre-school registration of first grade students

and 14 days prior to the distribution of school preference

forms for assignments in the first grade for the approaching

school year. O ther portions of the plan provide that the pre

2 For example, the amended and substituted plan provides for the elim ina

tion of segregation in connection with the school buses commencing with the

1965-66 session which begins late in August or early in September of this year.

T h is particu lar m atter will not be m entioned further.

24

school registration for children who will enter school at the

first grade level this fall will be held during May, and that

the assignment preference forms for students who are now in

the first grade are to be mailed out during that month.

T he Court thinks it proper that the pre-school registration

be held and the assignment preference forms be mailed out in

May, and also thinks that the notice provisions of the plan

are adequate. However, that schedule creates a time problem

of which all interested parties are aware, and renders it neces

sary for the Court to pass upon the plan expeditiously.

T he plan does not contemplate that the Board will on its

motion assign any Negro children to presently all-white schools

or any white children to presently all-Negro schools; nor does

it set up any fixed attendance areas based on residence, an ac

tion which would or might automatically integrate certain

schools. Rather, the Board plans to eliminate segregation by

giving students of both races at varying times and at varying

grade levels an opportunity to express, or to have expressed for

them, a choice of the schools which they desire to attend.

Proper expressions of choice will be honored as a m atter of

course unless to honor all of such expressions would result in

the overcrowding of particular schools. In the event a prob

lem of overcrowding a particular school arises, it will be solved

by non-discriminatory means with preference to be given to the

students living closest to the school. Those students whose

choices are rejected because of overcrowding will be given a

second choice which will be honored as a m atter of course

unless to do so would result in overcrowding of the school of

second choice, in which case the problem will be solved in a

racially non-discriminatory m anner with preference being

given to the applicants living closest to the school.

25

W ith respect to the 1965-66 school year choices will be

given to all students who are entering the schools of the Dis

trict for the first time at the first grade level and to those

who are now in the first grade and who will be promoted to

the second grade.

Before the end of the 1965-66 school year students who

are enrolled for that year in Grades 3, 4, and 5 and wTho will

be promoted, respectively, to Grades 4, 5, and 6, will be given

a choice with respect to the 1966-67 school year. I t will be

observed that students who will be promoted to Grade 3 for

the 1966-67 session will already have had a choice.

Before the end of the 1966-67 session students enrolled in

Grades 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11, and who are being promoted, re

spectively, to the 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th grades for

the 1967-68 session, will be given a choice for that session.

W ith respect to the 1968-69 session and subsequent ses

sions every child entering school for the first time at the first

grade level, and every child being promoted from the 6th to

the 7th grade, and every child being promoted from the 9th

to the 10th grade, will be given a preferential choice.

Under the plan students who are now enrolled in the 10th,

11th, and 12th grades will not be given a preferential choice,

bu t all other students now enrolled in the District or who

hereafter enter school at the first grade level will at some

stage have a choice of spending at least one year of their pub

lic school education in an integrated school. Desegregation of

the elementary grades will be completed in the 1966-67 session,

and the jun io r and senior high school grades will be de

segregated in the 1967-68 session.

26

Students who at the end of the 1965-66 session are en

rolled in the 1st, 2nd, 7th, 8th, 10th, and 11 grades, and stu

dents enrolled in the 6th, 9th, and 12th grades and who are

not promoted or graduated, will be assigned initially for the

1966-67 session to the same school which they attended

during the 1965-66 session. Each student enrolled during the

1965-66 session in the 6th grade and who is promoted to the

7th grade will be assigned initially for the 1966-67 session to

the jun ior high school in the District to which the students

graduating from the elementary school involved have cus

tomarily attended in years past. Likewise, students being pro

moted from the 9th to the 10th grade at the end of the 1965-66

session will be assigned initially to the high school which stu

dents being promoted from the junior high school in question

have customarily attended in past years. This simply means

that the jun ior and senior high grades will not be desegre

gated by means of preferential choices until the commence

m ent of the 1967-68 session.

A student who does not exercise a choice when his grade

level is reached in the course of the transition will not have

another choice until he is promoted from the sixth to the

seventh grade or from the n inth to the tenth grade as the case

may be. This is in line with the Board’s announced policy

against “lateral tranfers” from one school to another at the

same school level in circumstances other than exceptional, al

though the Board reserves the right in its discretion and for

valid cause to transfer a student from one school to another at

any grade or school level.3

8 T o be specifiic a “lateral transfer” is a transfer from one elementary

school to another, or from one junior high school to another, o r from one senior

high school to another. A “prom otional transfer” is one resulting from prom o

tion from an elem entary school to a ju n io r high school, or from a jun ior high

school to a senior high school.

27

It will thus be seen that when the transitional period has

been completed at the end of the 1967-68 session a student who

is entering school for the first time as a first grader will have

three opportunities to express a preference; a student who at

that time is in the elementary grades will have two opportuni

ties; and a student who is in jun ior high school will have one

opportunity.

A student who transfers into the District from elsewhere

during the transition period will have a choice if at the time

of his transfer his grade has been desegregated under the plan.

From the record before it, including the evidence pro

duced at the hearing held in January and the testimony of Mr.

Lee Roy Beasley, President of the Board, taken in the course

of the April 12 hearing, the Court finds that the present plan

has been adopted in good faith and in recognition of the fact

that the Board is required to proced with diligence and in

good faith to put an end to racial segregation in the schools

w ithin a reasonable time. As a m atter of fact, the evidence

discloses that the Board was giving serious consideration to the

form ulation of a transitional plan prior to the filing of this

suit.

T he Court further finds that it is appropriate for the

District to eliminate compulsory and discriminatory segrega

tion in the schools by means of a transitional plan designed to

and capable of bringing such segregation to an end w ithin a

reasonable time and within what has been term ed the “tol

erance” of the Brown decision.

And the Court is persuaded that the present plan of the

Board constitutes a prom pt and reasonabe start toward ending

compulsory segregation and that it should be approved, sub

ject, of course, to the power of the Court to enter such further

28

orders, if any, with respect to the desegregation of the District’s

schools as future developments may justify or necessitate.

In appraising the plan it should be recognized at the out

set that although in theory preferential choices will be extended

to all students from time to time with regard to race, neverthe

less from a practical standpoint the really significant expres

sions of choice, at least for a time, will be those made by or on

behalf of Negro students who desire, or whose parents desire

for them, an integrated education.

It has been held frequently that the Brown decision does

not require affirmative integration of the schools; it simply

prohibits compulsory racial segregation. And the constitu

tional right of a student to a desegregated education is, in the

C ourt’s estimation, satisfied if he is not excluded from the

school of his choice on account of his race.

It is the prim ary function of the local school officials and

not that of the federal courts to assign students to particular

schools, and local school boards are free to adopt such methods

of assignment as they deem best, provided that the methods

chosen are not such as to create, foster, or perpetuate compul

sory racial segregation. A school board is not required by the

Fourteenth Amendment to adopt any particular m ethod of as

signment, and the Court is of the opinion, and now holds, that

it is permissible for a board to eliminate segregation either at

once or in a proper case over a period of transition by employ

ing a preferential choice m ethod of assignment, as the El

Dorado Board proposes to do, whereby Negro students who

desire to do so will be allowed to enter formerly all-white

schools.

T he Court is also of the opinion that a Negro student

need not be given an opportunity to exercise a choice each and

29

every year of his public school education. From a purely edu

cational and administrative standpoint there is a good deal

to be said for a policy against lateral transfers, provided that

such policy is applied nondiscriminatorily. If any student is

given a free choice of schools when he first goes into the system,

and again when he moves from the elementary to the junior

high grades, and again when he moves on to the senior high

grades, no constitutional problem would appear to be in

volved. Those choices the defendant District proposes to give,

and the plan makes clear that the choices are to be those of

the students and their parents, and that the school authorities

are not to attem pt to influence the exercises of choice. Nor is

any student to be rewarded or penalized because of the choice

made.

It is true, of course, that an expression of choice involves

the exercise of initiative by a Negro student or his parents, bu t

the initiative called for is minimal, and to require its exercise

is not unreasonable in the eyes of the Court. As stated, subject

to the qualification relative to overcrowding, expressions of

choice will be honored as a m atter of course. N either the stu

dents nor their parents will be required to go through burden

some administrative procedures, nor will the assignment of

students be governed by the application of detailed and techni

cal “assignment criteria.”

T he three year period of transition contemplated by the

Board is not unreasonably long. W hen the plan goes into

effect this fall, it is capable of bringing into the present all

white system substantial num ber of Negro students at the first

and second grade levels, and as the plan proceeds, it is capable

of introducing into that system substantial numbers of Ne

groes at the higher grade levels. If during or after the transi

tional period so many Negro students apply for admission to

30

the present all white system as to create conditions of over

crowding, then, as stated, the problems are to be solved in a

m anner which is racially nondiscriminatory.

As has been pointed out, the plan does not contemplate

that all of the Negro students who are now enrolled in the

system will be given a preferential choice to complete all or

any part of their education under integrated conditions. Stu

dents who are now in high school, including some of the

plantiffs, will be required to finish their public school work

in segregated facilities unless they can persuade the Board

that their circumstances are so exceptional as to justify lateral

transfers notwithstanding the general policy of the Board

against such transfers. But that situation is not an unusual

comcomitant of any transitional plan which is to operate pro

gressively through the lower to the higher grades and over a

period of years. T he Court does not say that the denial to

certain students in the El Dorado District of any opportunity

to express a preferential choice of school assignment is not dis

criminatory. But, in the circumstances the Court finds the dis

crim ination involved is tolerable.

One objection of plaintiffs to the plan is that it makes

no provision for the desegregation of the administrative staff

and faculty. Assuming without deciding that a Negro student,

as a student, is entitled to such desegregation and has standing

to seek it in a suit of this kind to which no member of the

faculty is a party, the Court, in the exercise of its discretion, is

not willing to withhold approval of the plan because of its

failure to deal with the staff and faculty.

T he Court takes judicial notice and the Board is presum

ably cognizant of the relevant provisions of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964. T he Court is not blind to matters of general knowledge

31

in Arkansas, and knows that many school districts all over the

State, doubtless including the El Dorado District, are endeavor

ing to bring themselves w ithin the Act so that the flow of fed

eral funds to them in aid of education will not be cut off. T he

Court thinks it quite probable that if and when the Board

brings itself into compliance with the Act and the regulations

promulgated thereunder, the problem of staff and faculty de

segregation will take care of itself. In any event, the Court is

not inclined to order the Board at this time to take any steps

in that area.

T he Court has not undertaken in this opinion to state or to

discuss in detail all of the objections of the plaintiffs to the

plan. Suffice it to say that the Court has considered all of

such objections in coming to its conclusion that the plan as

finally revised should be approved.

An appropriate decree will be entered.

Dated this 29th day of April, 1965.

J. S m i t h H e n l e y

United States District Judge.