United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education Brief on Rehearing for Intervenors and Appellants

Public Court Documents

March 4, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education Brief on Rehearing for Intervenors and Appellants, 1967. 2571b147-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e2abdd2f-5651-4e20-ae4a-9b4f0790f54f/united-states-v-jefferson-county-board-of-education-brief-on-rehearing-for-intervenors-and-appellants. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

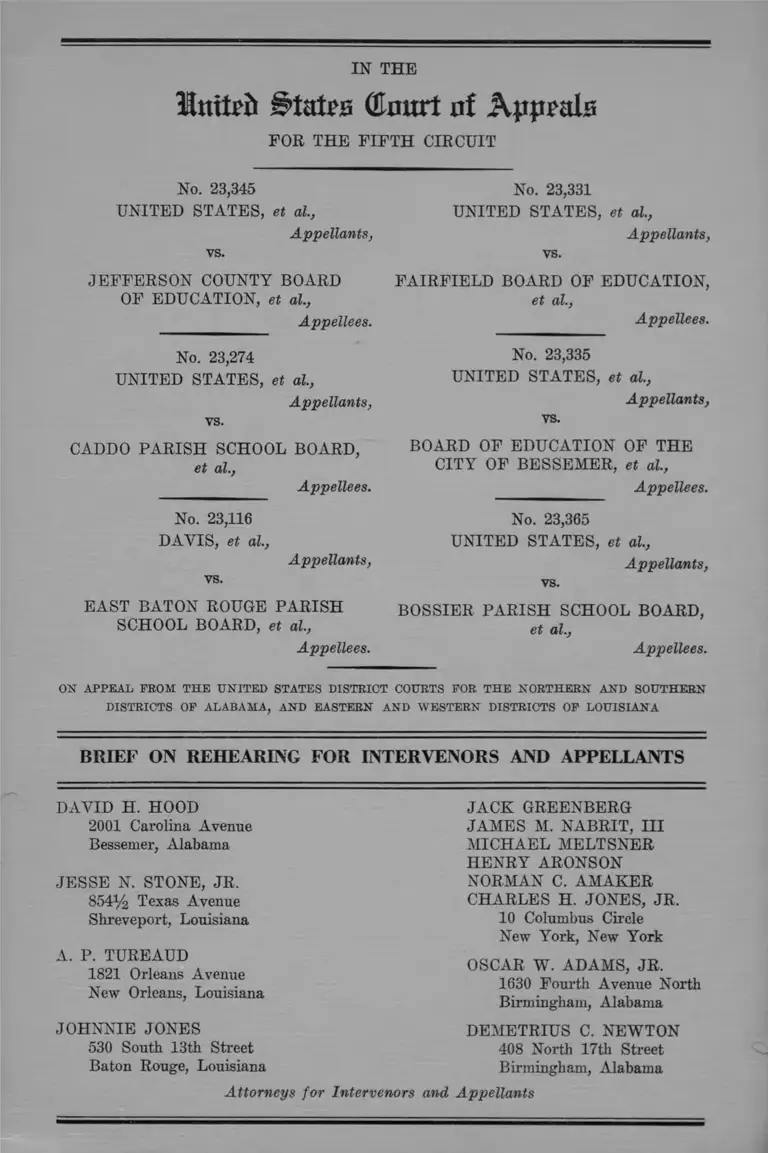

IN THE

■Huttib States Court of Ayprals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 23,345

UNITED STATES, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD

OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Appellees.

No. 23,274

UNITED STATES, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD,

et al.,

Appellees.

No. 23,116

D AYIS, et al.,

Appellants,

No. 23,331

UNITED STATES, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Appellees.

No. 23,335

UNITED STATES, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY OF BESSEMER, et al,

Appellees.

No. 23,365

UNITED STATES, et al,

Appellants,

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH

SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Appellees.

BOSSIER PARISH SCHOOL BOARD,

et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURTS FOR THE NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN

DISTRICTS OF ALABAMA, AND EASTERN AND WESTERN DISTRICTS OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF ON REHEARING FOR INTERVENORS AND APPELLANTS

DAVID H. HOOD JACK GREENBERG

2001 Carolina Avenue JAMES M. NABRIT, III

Bessemer, Alabama M ICHAEL MELTSNER

HENRY ARONSON

JESSE N. STONE, JR. NORMAN C. AM AKER

854% Texas Avenue CHARLES H. JONES, JR.

Shreveport, Louisiana 10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

A. P. TUREAUD OSCAR W. ADAMS, JR.

New Orleans, Louisiana 1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

JOHNNIE JONES DEMETRIUS C. NEWTON

530 South 13th Street 408 North 17th Street

Baton Rouge, Louisiana Birmingham, Alabama

Attorneys for Intervenors and Appellants

I N D E X

Statement ............................................................................... 2

I. No. 23,335, United States, et al. v. Board of

Education of the City of Bessemer ................... 2

A. Pupil Assignment Policy ................................. 3

B. The Plan Approved by the Court B elow ....... 5

C. Faculty and Administrative Assignments .... 8

D. Inequality ................................ 9

E. School Construction ........................................... 10

P. Other Matters .................... 10

G. Administration of the P lan ............................... 10

II. No. 23,345, United States, et al. v. Jefferson

County Board of Education........... ....................... 11

A. Pupil Assignment Procedures......................... 11

B. The Plan Approved by the Court B elow ....... 16

C. Faculty Assignments ......................................... 18

D. Bus Transportation ........................................... 18

E. Inequality in Facilities for N egroes.... .......... 19

F. Other Matters ..................................................... 20

G. Administration of the Plan ............................. 20

III. No. 23,331, United States, et al. v. Fairfield

Board of Education ............................................. ... 21

IV. No. 23,274, United States, et al. v. Caddo Parish

School Board ................................... 26

PAGE

11

V. No. 23,365, United States of America, et al. v.

The Bossier Parish School B oa rd ......................... 30

VI. No. 23,116, Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish

School B oa rd ............................................................. 40

A. The 1965 P la n ..................................................... 42

B. Aspects of the. 1963 Plan ................................. 45

C. Exclusion of Evidence on Adequacy of the

Plan ....................................................................... 46

A rgum ent—

Introduction ....................................................................... 47

I. The Plans Approved by the Courts Below Are

Not Adequate to Effectuate Transitions to

Racially Nondiscriminatory School Systems ....... 48

II. The Recent Decision of the Court of Appeals for

the Tenth Circuit Demonstrates the Soundness

of the Panel’s Opinion and D ecree....................... 54

III. The Adequacy of Freedom of Choice Plans Must

Be Determined in the Context of Particular

Cases ........................................................................... 58

IV. The Adoption of a Uniform Decree Is Essential 64

C onclusion ........................................................................... 69

Certificate of Service........................................................... 70

A ppen dix—

Excerpts from R acial I solation in th e P ublic

S c h o o l s .................................................................................... l a

PAGE

Ill

T able of Cases

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 . 61

PAGE

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 ................................... 60

Baskin v. Brown, 174 F.2d 391 (4th Cir. 1949) ........... 60

Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Public

Schools v. Dowell, No. 8523, 10th Cir., Jan. 23,

1967 .......................................................................47,48,54,56

Bossier Parish School Board v. Lemon, No. 22,675,

5th Cir. Jan. 5, 1967 ...................................................30, 33

Bradley v. Board of Education, 382 U.S. 103 ........... 52

Bradley v. Board of Education of the City of Rich

mond, 345 F.2d 310 (4th Cir. 1965), vacated on

other grounds, 382 U.S. 103 ....................................... 50

Briggs v. Elliott, 98 F. Supp. 529 (E.D. S.C. 1951) .... 63

Briggs v. Elliott, 103 F. Supp. 920 (E.D. S.C. 1952) .... 63

Briggs v. Elliott, 342 U.S. 350 ......................................... 63

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E.D. S.C. 1955)

53, 57, 62, 63

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 ........... 58, 63

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955)

48, 53, 59, 64, 68

Brunson v. Board of Trustees of School Dist. No. 1,

30 F.R.D. 369 (E.D. S.C. 1962) ................................. 63

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 311 F.2d 107 (4th Cir.

1962) ................................................................................. 63-64

Brunson v. Trustees of School Dist. No. 1, 244 F. Supp.

859 (E.D. S.C. 1965) ....................................................... 64

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 .................................60, 61

Buckner v. School Board of Greene County, 332 F.2d

452 (4th Cir. 1964) ....................................................... 50

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F.2d 491

(5th Cir. 1961) 49

IV

City of Birmingham v. Monk, 185 F.2d 859 (5th Cir.

1950), cert, denied 341 U.S. 940 ......... .......................... 61

Clark v. School Board of City of Little Bock, 369 F.2d

661 (8th Cir. 1966) ....................................................... 50, 52

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 ........................................... 48

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 364 F.2d 896 -(5th Cir. 1966) ........................... 66

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 214

F. Supp. 624 (E.D. La.) ............................................... 41

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 219

F. Supp. 876 (E.D. La. 1963) ..... ................................. 41

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

971 (W.D. Okla. 1965), affirmed No. 8523, 10th Cir.,

Jan. 23, 1967 ............................................................... 54-55, 62

East Baton Rouge Parish School Board v. Davis, 289

F.2d 380 (5th Cir. 1961), cert. den. 831 ......................40,41

Elmore v. Rice, 72 F. Supp. 516 (E.D. S.C. 1947),

affirmed Rice v. Elmore, 165 F.2d 387 (4th Cir. 1947),

cert, denied 333 U.S. 875 ............................................... 60

Goss v. Board of Education of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683 54

Greene v. School Board of City of Roanoke, 304 F.2d

118 (4th Cir. 1962) ......................................................... 49

Jimerson v. City of Bessemer, Civil No. 10054, N.D.

Ala., Aug. 3, 1962 ............................... .......... .................. 61

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, Vir

ginia, 278 F.2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ..................... ......... 49

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsbor

ough County, 277 F.2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960) ............... 49

PAGE

V

Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County, 305

F.2d 94 (4th Cir. 1962) ................................................... 49

Miller v. School District No. 2, Clarendon County, S. C.,

253 F. Supp. 552 (D. S.C. 1966) ................................. 64

Miller v. School District No. 2, Clarendon County,

256 F. Supp. 370 (D. S.C. 1966) ................................... 64

Nesbit v. Statesville Board of Education, 345 F.2d 333

(4th Cir. 1965) ................................................................. 55

PAGE

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73 ........................................... 60

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 IT.S. 536 ....................................... 60

Northcross v. Board of Education of City of Memphis,

302 F.2d 819 (6th Cir. 1962) .... .................... ...... ........ 49

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) ....... 49

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 ....................................... 60

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) ............................... 67

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) ............................... 50

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649 ....................................... 60

Sutton v. Capitol Club, Inc., No. LR-64-C-124, W.D.

Ark., April 12, 1965, 10 Race Rel. L. Rep. 791 ........... 60

United States v. Bossier Parish School Board, 220 F.

Supp. 243 (W.D. La. 1963), aff’d per curiam 336 F.2d

197 (5th Cir. 1964), cert. den. 379 U.S. 1000 ...... . 30

United States v. Bossier Parish School Board, 349 F.2d

1020 (5th Cir. 1965) ..................................... ......... 28, 30, 34

United States v. City of Bessemer Board of Education,

349 F.2d 1021 (5th Cir. 1965) ....................................... 5

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

349 F.2d 1021 (5th Cir. 1965) 16

VI

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 309 F.2d

630 (4th Cir. 1962) ........................................................... 49

Wheeler v. Durham Board of Education, 346 F.2d 729

(4th Cir. 1965) ................................................................. 50

Other Authorities:

Civil Bights Act of 1964, Section 409 ........................... 68

Southern School News, Vol. II, No. 2, August 1955 .... 63

U. S. Comm, on Civil Bights, Beport, Survey of School

Desegregation in the Southern and Border States—

1965-66 ............................................................................. 59-60

IT. S. Commission on Civil Bights, Racial Isolation in

the Schools (1967) ................................. ....................... 52, 61

PAGE

IN THE

Imteft States Qlourt of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 23,345

UNITED STATES, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD

OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Appellees.

No. 23,274

UNITED STATES, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

No. 23,331

UNITED STATES, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Appellees.

No. 23,335

UNITED STATES, et al,

Appellants,

vs.

CADDO PARISH SCHOOL BOARD,

et al.,

Appellees.

No. 23,116

DAVIS, et al,

Appellants,

BOARD OF EDUCATION OP THE

CITY OF BESSEMER, et al,

Appellees.

No. 23,365

UNITED STATES, et al,

Appellants,

EAST BATON ROUGE PARISH

SCHOOL BOARD, et al,

Appellees.

BOSSIER PARISH SCHOOL BOARD,

et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURTS FOR THE NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN

DISTRICTS OF ALABAMA, AND EASTERN AND WESTERN DISTRICTS OF LOUISIANA

BRIEF ON REHEARING

FOR INTERVENORS AND APPELLANTS

2

Statement

This consolidated Brief on Beargument is submitted on

behalf of the Negro pupils and parents who, as private

parties plaintiff, initiated these six school desegregation

suits involving the public schools of the cities of Bessemer,

and Fairfield, Alabama, Jefferson County, Alabama, and

Caddo, Bossier, and East Baton Bouge Parishes in Louisi

ana. In each of the cases, except No. 23,116, Davis v. East

Baton Rouge Parish School Board, the United States of

America intervened as a party plaintiff and appealed from

a district court order approving a proposed desegrega

tion plan. The private plaintiffs in these cases were per

mitted to intervene as appellants in this Court. In the

Davis case, supra, the appeal from a district court order

approving a desegregation plan was taken by the private

plaintiffs.

Several briefs have been submitted before and after the

original arguments in these cases. However, in order that

the entire Court may have access to a statement of the

proceedings and facts in each case, in a single volume,

we restate them below. The opinion of the panel of this

Court which decided the cases on the original arguments

stated that the Court had “ carefully examined each of the

records” and that: “ In each instance the record supports

the decree” (Slip Opinion, p. 111). We agree.

I. IVo. 23,335, United States, et al. v. Board of

Education of the City of Bessemer

The complaint in this action was filed by Negro students

and parents on May 24, 1965, to desegregate the public

schools of Bessemer, Alabama (B. 11-19). The City of

Bessemer maintained ten schools for the 5,286 Negro and

2,920 white pupils enrolled during the school year 1964-65

3

(R. 100). The system has 1 white high school (grades

10-12), 1 white junior high school (grades 7-9), 4 white

elementary schools (grades 1-6), 2 Negro schools offering

grades 1-12, and 2 Negro schools offering grades 1-8 (R.

95-97).

The procedures in the Bessemer desegregation plan

presently before this Court adopt with minor modifica

tions pupil assignment procedures utilized by the Bessemer

board prior to the plan to maintain a rigidly segregated

public school system. Detailed descriptions of these assign

ment procedures, of other aspects of the system, and of

the approved plan follow :

A. Pupil Assignment Policy

Bessemer maintained a dual system of schools, “ one set

of schools for Negroes and one set for whites,” at the

time this action was filed (R. 116). One map sets out the

attendance zones for each of the 4 Negro schools (R. 95)

and a second map sets out zones for each of the white

schools (R. 96). When asked at the hearing below if the

racial zone maps were “ being used at the present time,”

the Superintendent responded: “ To the best of my knowl

edge, we are still following these maps” (R. 98). Counsel

for the board asked that these maps be withdrawn from

the court at the conclusion of the hearing because “ Dr.

Knuckles has told us these are maps we need constantly”

(R. 99).

The board also maintained a map showing the residence

and race of each student and location of each of the schools

within the system, with “red dots showing the location

o f the Negro pupils” and “green dots indicating the resi

dential location of the white pupils enrolled in school

during this year” (R. 105-106).

4

The superintendent testified that the school system “ is

geared to placing students in schools that are closest to

their neighborhood” (R. 108). Yet, adherence to a policy

of strict separation of the races in the schools did not al

ways result in students being so assigned. Superintendent

Knuckles further testified:

Q. Do you have very many students who are at the

present time passing by schools which are closest to

their neighborhood!? A. I am sure we have some.

Q. Do you have any of your white students . . .

who are passing by Negro schools to go to white

schools? A. I expect there are some.

Q. And vice versa? A. And vice versa, yes sir.

(R. 108-109)

Some students were required to pass a school maintained

for children of the opposite race and “ cross a railroad

track and some more than one railroad track” to reach a

school maintained for their race (R. 159).

School zone lines were changed periodically as condi

tions changed, and in some instances the superintendent

and the hoard “have administratively transferred the pupils

who live in a particular area from one school to another

as the school was built or as a school was added to or

particular facilities were abandoned” (R. 146). The super

intendent testified that when a particular zone contained

more students than the school could accommodate “we just

had to arbitrarily assign them to another school” (R. 147).

Through this system of assignments the schools within

the City of Bessemer were kept completely segregated.

No white students attended Negro schools and no Negroes

attended white schools (R. 28).

5

B. The Plan Approved by the Court Below

On July 30, 1965, the conrt below entered an order ap

proving with minor modifications the first plan submitted

by appellees (R. 64-66). An appeal was taken from that

order and on August 17, 1965, this Court vacated the

judgment and remanded for further consideration, United

States v. City of Bessemer Board of Education, 349 F.2d

1021 (5th Cir. 1965) (R. 71-72). Thereafter, appellees filed

an amended plan (R. 81-84) which was approved by the

conrt below on August 27, 1965 (R. 85-86). The amended

plan is the subject of this appeal.

The plan adopts the racial assignment policy based upon

a dual set of zones described above, subject to minor modi

fications. Initially, pursuant to the plan, “ all pupils in

all grades of the Bessemer system will remain assigned

to school to which they are assigned or will be assigned

to schools in accordance with the custom and practice for

assignment of pupils that have prevailed in the school

system prior to the entry of the judgment of the District

Court in this case on June 30, 1965, such method of assign

ment being necessary in order to prevent a disruption of

the school system and to maintain an orderly administra

tion of the schools in the interests of all pupils” (R. 45-46).

Students entering the first grade are specifically required

to report to the elementary school located in the zone

maintained for their race—Negro students reporting to

Negro schools and white students reporting to white schools

(R. 44). Only after this segregated racial assignment

procedure may “ an application may be made by the parents

for the child’s assignment to any school (whether formerly

attended only by white children or only by Negro children)”

(R. 44).

Similarly, students in all other grades are initially as

signed to segregated schools maintained by appellees for

6

students of their race (R. 45).1 Once assigned to these

schools, students in grades 1, 4, 7, 10 and 12 during the

school year 1965-66, students in grades 2, 3, 8 and 11 dur

ing the school year 1966-67, and students in grades 5, 6

and 9 during 1967-68 may apply for transfer “ to a school

heretofore attended only by pupils of a race other than

the race of the pupils in whose behalf the applications are

filed” (R. 43-44, 88-83). Transfer forms must be picked

up, completed, and returned to the superintendent’s

office during the designated transfer period (R. 82).

Transfer applications will thereafter “be processed and

determined by the board pursuant to its regulations as

far as is practicable” (R. 44).2 No regulations were ever

introduced, and on cross-examination the superintendent

was unable to say what regulations were referred to by

1 Q. Am I correct that the plan in essence will assign particular schools

on the basis of race? A. Most of the pupils in Bessemer with the ex

ception of the first graders are presently assigned to schools they are

enrolled in and their records are there.

Q. Even in the grades you are desegregating you contemplate they will

attend the school that heretofore has been for their race unless a transfer

application is filed and approved? A. That is correct. (R. 264)

2 Prior to the adoption o f the plan and the possibility of desegregation

o f the schools, the board liberally granted transfers.

Q. Is it fair to say you granted that request more or less as a

matter of course as long as there was capacity in the school to which

they were transferring? A. I think that is true. W e attempted to

accomodate people where we didn’t overburden the school, the classes

or the teachers. (R. 148)

* * *

Q. Mr. Knuckles, you have testified in answer to some of my ques

tions about transfers from one zone to another. Have they been

initiated normally by either a letter or a telephone call? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. No particular form being used? A. No form.

Q. And there has been no time limit for submitting them to the

board? A . No, but I did tell you we have discouraged transfer

during the school year.

Q. After school is started? A. Yes, sir.

7

the plan or their subject, except that they were “general

regulations under which we have operated for a long time”

(R. 260).

The above described transfer requirements do not ap

ply to Negro students applying for transfers from one

Negro school to another Negro school or to white students

applying for a transfer from one white school to another

white school.

The Court: I think this plan after the first para

graph only refers in cases where Negro pupils apply

to transfer to schools heretofore attended only by

white pupils in these classes and vice versa. I think

that is the plan.

Q. Is that the way you expect to administer the

plan? A. Yes, sir.

Q. So that procedure will be used only when a

Negro applies to attend a white school or a white

applies to attend a previous Negro school? A. In

these grades. (R. 261)

Students new to the system are similarly assigned on

the basis of race.3 The plan is silent and the board is

undecided on how applications to overcrowded schools

will be processed.

Q. I f a Negro child applies for the Bessemer Junior

High School [a white school] in the seventh grade, a

3 A. They will appear at a school to enroll and will abide by the same

regulations. I£ a child asks to transfer to the school o f another race and

it is after the deadline date, I would assume that he, like other children

who let the deadline pass for this time, just wait until his grade is open

at another time.

Q. Dr. Knuckles, a white child moving into the school district and is

due to enter the seventh grade will automatically go into the seventh grade

without making out any papers at all in a white school? A. A Negro

child would do the same thing in a Negro school. We are proposing in

this instance to follow the custom that has been followed for some time

in the interim period. (R. 265)

8

desegrated [sic] grade, and lives closer to Bessemer

Junior High School than white children who will seek

enrollment in the Junior High School, is there any

decision which will have priority under the plan?

Which will have priority if there isn’t room for both?

A. That question has not been determined.

Q. You don’t know? A. That is correct.

Under the plan students will not be permitted to transfer

from a school to which they are racially assigned to a

school maintained for children of the other race to take

a course not offered at their school unless the student is

enrolled in a grade reached by the plan.4

The plan provides for notice through publication in a

local newspaper. No individual notices are contemplated

(R. 266).

C. Faculty and Administrative Assignments

The plan makes no provision for non-raeial faculty

assignments.

The board employs 285 classroom teachers, 175 Negro

and 110 white (R. 115). For the 1964-65 school year

the board had a teacher turnover rate of 11.85% (R. 119).

The superintendent testified that all Negro teachers in

the system have met the minimum requirements of the

board and that they possessed “ the same or similar quali

fications as . . . white teachers” (R. 122, 123).

The faculty remains totally segregated with Negro

teachers instructing Negro students and white teachers

4 Q. And it [the transfer application] will be considered even though

the child is in a grade that has not yet been reached by the plan? A. I

think we will live with and operate under the provisions laid out in this

plan during this interim period.

Q. And that is your answer to that question? A. Yes, sir. (R. 267)

9

instructing whites (R. 120). The board has considered

desegregating the faculty but has not reached a conclu

sion “ simply because the request had not come from

parents at the time for the assignment of Negro children

to schools other than those they were attending” (R. 118-

119).

Teachers were freely assigned by the board when such

transfers met the administrative convenience of the dis

trict. “ [W ]e had three rooms in this small school and we

closed them and moved the children to one of the larger

schools and moved the teachers and consequently we saved

the operational cost of that building” (R. 244).

Faculty meetings are held on a segregated basis (R. 251).

Administrative and supervisory staff is also segregated.

Of 10 administrators employed by the board, 9 are white.

The one Negro administrator is in charge of Negro schools

(R. 116) and is provided an office apart from the other

administrators in a Negro school. No Negroes work in

the central office (R. 118).

D. Inequality

The record contains many examples of the inequality

between Negro and white schools, including:

1. Pupil-Teacher Ratios (R. 162-164):

Negro High Schools White High School

Carver 25 “ plus” / l Bessemer H. S. 19.08/1

Abrams 25/1

2. Library Boohs per Pupil (R. 164-165):

Abrams 8/1 Bessemer H. S. 19.08/1

Carver 3.17/1

10

3. Elective Subjects Offered in High Schools

The superintendent admitted that more electives were

offered in the white than the Negro high school but at

tributed this disparity to “ community pressure” (E. 166).

Latin, Spanish, and two years of French are offered in the

white high school; the only language taught in the Negro

high school is one year of French. Journalism is taught

in the white but not the Negro schools (E. 167-168, 229,

233-234).

The plan makes no provision for equalizing the facilities

between Negro and white schools.

E. School Construction

The Bessemer school district contemplates expending

approximately $460,000 for rebuilding or adding to exist

ing segregated facilities (E. 125). The plan makes no

provision to require that a rebuilding program be designed

so as to aid in abolishing the dual system.

F. Other Matters

The plan contains no provisions for individual notice

to pupils, no provision with respect to locating new school

buildings or additional facilities in such a manner as to

eliminate segregation, no provisions with respect to non

discrimination in various school connected or sponsored

activities or in extracurricular activities, and no provi

sions with respect to periodic reports to the court con

cerning desegregation.

G. Administration of the Plan

In the first year of the plan, 1965-66, only 13 of approxi

mately 5,284 Negroes attended formerly white schools.

(Affidavit of St. John Barrett attached to Motion to Con

11

solidate and Expedite Appeals in these cases, filed in this

Court April 4, 1966.) In the second year of the plan, the

current 1966-67 term, about 64 Negro pupils attend for

merly white schools. (Information supplied to intervenors

and appellants by U. S. Department of Health, Education

and Welfare.)

II. No. 23,345, United States, et al. v. Jefferson

County Board of Education

This action was filed June 4, 1965, by Negro students

and parents against the Jefferson County Board of Edu

cation requesting that the hoard be enjoined from continu

ing to operate a system of dual and unequal public schools

(R. 9-16). The Jefferson County Board of Education main

tains approximately 117 schools for 45,000 white students

and 18,000 Negro students (B. 80).

The procedures incorporated in the plan for desegrega

tion approved by the court below (R. 30-37, 66-68), adopt

with minor modifications the pupil placement procedures

utilized by the Jefferson County Board of Education since

1959 to maintain a rigidly segregated public school system.

Descriptions of these pupil assignment procedures, of other

aspects of the system, and of the plan follow.

A. Pupil Assignment Procedures

From 1959 until adoption of the plan under considera

tion in 1965 the Board assigned all pupils pursuant to a

pupil placement plan (R. 96-107). During this period the

district remained completely segregated. On June 22, 1965,

Superintendent Kermit A. Johnson testified that “at the

present time” Negro and white children are separated

within the school district.5 Total separation of the races 6

6 Q. Heretofore, and at the present time, it is the policy o f the Board

o f Education to separate Negro and white children in the school; isn’t

that true? A. W e have had them separated, and there has not been any

12

within the Jefferson County School District was effected

by utilizing the following pupil assignment procedures:

a. Assignments: Students entering the first grade, stu

dents newly moving into the jurisdiction of the board, and

students residing within the district who have been attend

ing school in another “ school community” 6 were “ accepted,

approved and enrolled” by a principal to his school upon

determining that the student resides in his “ school com

munity” and that the student “would normally attend his

school.” * 6 7 (E. 101-102). Without exception, students as

signed to schools they “would normally attend” resulted

in Negroes being assigned to Negro schools and whites

being assigned to white schools (E. 164).

other operation up until this point. I would hesitate to say the policy o f

the Board, because we have not had an application up until this time.

Q. But the Board has never authorized you— A. Never taken the

initiative for it or authorized me to make any changes. (R. 94)

6 Dr. Johnson described how a principal would define the boundaries of

his “ school community” as follow s:

A. They are not defined except those who live relatively close to the

school and then there is a broad area there where they might go to

his school or some other school and this is a case where he would

raise the question whether he should or shouldn’t take such students.

Q. You state the only way the principal o f any school would know

what pupils reside in his school community is on the basis of addresses

of the students already in school and who had attended the school in

the past? A. That is one of the best guides. He doesn’t have a defi

nition of a school community. It is a general thing. We don’t have

the geographical zones. In general it is always the closest to his

school would go to his school. (R. 163)

7 “How would a principal of a white school, elementary school, know

who would normally attend his school? What students would normally

attend his school? A. Well, there would be the brothers and sisters of

the students he had who lived in that general area.

Q. Assuming a Negro child or a white child lived next door to one

another, would that child be a person the principal would consider nor

mally would attend his school? A. In the past they would not come

under the general definition o f “ normally attending that school.” (R.

163-164)

13

b. Transfers: Students who desired to attend a school

other than the one they “would normally attend” (a school

provided exclusively for students of the white or Negro

race) or the school within his “ school community” (the

school nearest his home) were required to apply for a

transfer (R. 101-104). Requests for transfers were granted

only by the Central Office (R. 101-104). Seventeen “ fac

tors” were considered by the Central Office in evaluating

transfers.8 The list includes such matters as “home en

vironment,” “ severance of established social and psycho-

8 The 17 factors (R. 103-104) :

“Assignment, transfer and continuance o f pupils; factors to be

considered—

1. Available room and teaching capacity in the various schools.

2. The availability of transportation facilities.

3. The effect of the admission of new pupils upon established or

proposed academic programs.

4. The suitability of established curricula for particular pupils.

5. The adequacy of the pupil’s academic preparation for admission

to a particular school and curriculum.

6. The scholastic aptitude and relative intelligence or mental energy

or ability o f the pupil.

7. The psychological qualification of the pupil for the type of

teaching and associations involved.

8. The effect o f admission of the pupil upon the academic progress

o f other students in a particular school or facility thereof.

9. The effect o f admission upon prevailing academic standards at

a particular school.

10. The psychological effect upon the pupil o f attendance at a

particular school.

11. The possibility or threat o f friction or disorder among pupils

or others.

12. The possibility of breaches of the peace or ill will or economic

retaliation within the community.

13. The home environment o f the pupil.

14. The maintenance or severance of established social and psycho

logical relationships with other pupils and with teachers.

15. The choice and interests of the pupil.

16. The morals, conduct, health and personal standards of the

pupil.

17. The request or consent of parents or guardians and the reasons

assigned therefor.”

14

logical relationships” and the “morals, conduct, health and

personal standards” of the pupil requesting transfer (R.

103-104, 158). Applications for “ transfers” 9 required the

signature of both parents, the occupation and name of the

employer of both the students’ mother and father or guard

ian, the race of the applicant. This information was to

be included upon a transfer application and submitted to

the Superintendent’s Office. In considering transfer appli

cations :

“ [T]he superintendent may in his discretion require

interviews with the child, the parents or guardian, or

other persons and may conduct or cause to be con

ducted such examinations, tests and other investiga

tions as he deems appropriate. In the absence of

excuse satisfactory to the superintendent or the board,

failure to appeal for any requested examination, test

or interview by the child or the parents or guardian

will be deemed a withdrawal of the application.” (R.

100).

Superintendent Johnson testified that he never notified

parents, students or anyone else in the County that Negro

pupils could request assignment to a white school (R.

143). No Negro ever applied for a transfer to an all-white

school (R. 94). During 1964-65, 200 requests for transfer

were made and 95% were granted (R. 157), but none of

these were requests for desegregation (R. 94). No trans

fer period was designated; requests could be made at any

time (R. 93).

c. Reassignments: Once enrolled, either by assignment

or transfer “ [A ] 11 school assignments shall continue with

out change until or unless transfers are directed or ap- 8

8 Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2-A (R. 97-98).

15

proved by the superintendent or liis duly authorized rep

resentative.” (R. 99). Negro elementary school graduates

were automatically assigned to a Negro junior high school

and Negro junior high school graduates were automati

cally assigned to a Negro senior high school. Similarly,

white students were automatically assigned on a racial

basis.10 The district specifically recognized these automatic

assignments or “ feeder” arrangements: “An application

for Assignment or Transfer of Pupils Card must be filled

out for each pupil entering your school for the first time

either by original entry or transfer except pupils coming

from feeder schools.” (R. 101) (emphasis supplied). Thus

students were initially assigned to segregated schools and

thereafter locked into these assignments. This lock-in

effect continued on throughout the students’ public school

career.

Assignments—whether through transfer, reassignment or

initial assignment—were all made to schools which were

admittedly constructed exclusively for students of the

white or Negro race (R. 130-131). Even as to proposed

future school construction, the Superintendent was able to

identify the race of the students for whom schools were

planned but not yet constructed (R. 131-132). Racial dot

maps, indicating the race and residence of every student

within the district, are maintained by the Board (R. 89).

10 Q. What about students who axe, for example, in the sixth grade

going to the seventh grade in another school that is separate and distinct?

A. Their names are passed over to the high school principal from the

elementary principal and their permanent records kept in the individual

folders. Every child has a folder with his records in it. They are passed

on to the high school and by that procedure the principal knows the

number and who it is he is expecting.

Q. That is an automatic process? A. That has been the way it has

operated in the past. (R. 195)

16

B. The Plan Approved by the Court Below

On July 22, 1965 the court helow entered an order

approving the first plan submitted by appellees (R. 52-53).

The United States appealed that order and on August 17,

1965 this Court vacated the judgment and remanded the

cause for further consideration. United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, 349 F.2d 1021 (5th Cir. 1965).

Thereafter appellees filed an amended plan (R. 66-68)

which was approved.by the court helow on August 27,

1965. This amended plan is the subject of this appeal.

The amended plan adopts the pupil assignment proce

dures discussed above—procedures which effectively per

petuated a totally segregated dual system of schools—

subject to the following modifications:

1. Every student is initially assigned to a segregated

school. Students entering grades 1, 7, 9, 11 and 12 during

school year 1965-66, grades 2, 3, 8 and 10 during 1966-67

and grades 4, 5 and 6 during 1967-68 may therafter apply

for a transfer from the segregated schools they are

initially assigned to. Transfer applications are to be con

sidered in light of the “ factors” set out in footnote 8,

supra}1 Transfer applications must be picked up and

completed application forms must he deposited at the

office of the superintendent (R. 67).

2. Students entering grade 1 shall register at schools

provided for students of their race— Negro students at

Negro schools and white students at white schools. Any

entering first grade student may apply for a transfer to

another school by following the steps set out in para- 11

11 White students are thereby insured o f space in the formerly white

schools. Applications for transfer by Negro students are to be considered

in light o f the space available at the school applied for. A ground for

rejecting an application is overcrowding. See footnote 8, supra.

17

graph 1 above only after registering at a segregated

school (R. 164).

3. Negro students new to the district may attend a

school formerly provided for whites only if the student

is entering a grade being desegregated under the plan

(E. 213).

4. Notice of the plan shall be published three times in

a newspaper of general circulation within the county

(R. 34).

Superintendent Johnson was asked:

Q. How then does this plan change the method of

assignment which by your testimony has not resulted

in any Negro attending any white school and white

attending any Negro school? A. The biggest change

I can think of is this will be the first time we have

advertised the fact in the daily newspapers that they

may do this and the requests will be considered

seriously and probably approved. We have never

done that before and this would be a change (R. 162).

Appellees’ plan permits Negroes to transfer out of the

segregated schools to which they are initially assigned,

providing they submit a request for transfer on a form

which they must pick up at, and after completion deliver

to, the superintendent’s office; and, they are not dis

qualified by one or more of the 17 tests set out in foot

note 8, supra.

Superintendent Johnson’s justification for initially as

signing all entering Negro first graders to Negro schools

is “we feel this would be the logical place for him to go.

His brothers and sisters have gone there in the past and

he would be in an atmosphere of people he had known

18

in the past and we think it is the easiest way for him to

make his wishes known” (R. 164).

C. Faculty Assignments

The plan contains no provisions for ending faculty as

signments based on race.

The hoard employed a total of 2,268 school teachers, in

cluding approximately 600 Negroes (R. 118). All Negro

teachers possess qualifications required by the school

board (R. 121); 35 white teachers failed to fulfill the

school board’s minimum requirements (R. 136-137). Negro

teachers teach only Negro students (R. 121). White

teachers teach only white students (R. 122). Negro super

visory personnel are confined to supervising Negro stu

dents and schools (R. 122) and are provided offices apart

from white supervisory staff (R. 123, 144). Teacher turn

over within the system averages approximately 13% per

year (R. 120). Dr. Johnson testified that the 2,200 teachers

in the system were qualified to each any child in the

system within their subject specialty but that “ the main

problem” to teacher desegregation would be “ acceptance

on the part of the parents” (R. 135), and Negro teachers

would encounter difficulties in teaching white students

“because of the traditions and practices of our people up

until this time” (R. 144).

D. Bus Transportation

The plan contains no provision for desegregating trans

portation facilities.

The 253 buses maintained by the district were operated

on a segregated basis (R. 123-124) pursuant to separate

route maps—one setting out routes for Negro students

and a second for white students. These routes overlapped

each other in some instances (R. 127-128).

19

E. Inequality in Facilities for Negroes

The plan contains no provision for eliminating various

tangible inequalities in the facilities for Negroes and

whites.

The superintendent testified that although there is only

one vocational school for white boys, Negro high schools

have comparable vocational subjects not offered in white

schools (R. 146). The only high school not accredited by

the Southern Association is Negro Praco High which

the superintendent said had not applied for an accredita

tion (R. 220). The Negro Rosedale school has grades 1-12;

white Shades Valley school has grades 10-12 (R. 221).

The two schools are about half a mile from each other.

Rosedale has five or six acres; Shades Valley has about

twenty acres. Shades Valley has an auditorium, a stadium

and a separate gymnasium; Rosedale lacks a stadium and

a gymnasium (R. 221-222, 232).12 Although the superin

tendent could name five white schools having summer

school sessions, he could not “ recall” other schools hav

ing such sessions (R. 232). Negro Gary-Ensley Elemen

tary School has outdoor toilet facilities (R. 234). In

Negro Docena Junior High School, there are pot-bellied

stoves rather than central heating. Students must go a

block away to use indoor toilet facilities (R. 233-34). The

superintendent could not recall a Negro school which had

a stadium with seats and lights. He stated that Negroes

have not wanted to play football at night (R. 235). Most

stadiums and lights, including an $80,000 stadium at white

Berry High School, have been provided, according to the

superintendent, by citizen efforts (R. 235-36). He did

state, however, that the school system gives assistance to

12 By way o f contrast to the Rosedale-Shades Valley situation, the

superintendent testified that Negro Wenonah High School had facilities

superior to white Lipscomb Junior High School (R. 240-41).

20

such efforts by grading the ground and furnishing the

light fixtures (R. 236).

An appendix to Intervening Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 1,

shows that of the 79 white and 32 Negro schools listed,

81.3% of the Negro schools and only 54.4% of the white

schools had a student enrollment above capacity. Thus

33.3% of the Negro students (or 4,587 Negroes) were

enrolled in schools having over capacity population, while

only 10.1% of the white students (or 4,125 whites) were

enrolled in such schools. The United States also proved

that 45.6% of white schools but only 18.7% of the Negro

school enrollments were under capacity (R. 203).

F. Others Matters

The plan contains no provisions for individual notice

to pupils, no provision with respect to locating new school

buildings or additional facilities in such a manner as to

eliminate segregation, no provisions with respect to non

discrimination in various school connected or sponsored

activities or in extracurricular activities, and no provi

sions with respect to periodic reports to the court con

cerning desegregation.

G. Administration of the Plan

In the first year of the plan, 1965-66, only 24 of approxi

mately 18,000 Negroes attended formerly white schools.

(Affidavit of St. John Barrett attached to Motion to Con

solidate and Expedite Appeals in these cases, filed in this

Court April 4, 1966.) In the second year of the plan,

the current 1966-67 term, about 75 Negro pupils attend

formerly white schools. (Information supplied to inter-

venors and appellants by U. S. Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare.)

21

III. No. 23,331, United States, et al. v. Fairfield

Board of Education

The board maintains nine public schools in the City of

Fairfield, Alabama which serviced a total school-age pop

ulation of 3,095 children during the 1964-65 school term.

Of this number 2,273 were Negro and 1,822 were white

(Intervenor’s Exhibit No. 3).

By long term policy and practice, the board segregates

Negro school children from white school children through

the use of dual racial school zones (R. 182, 183, Inter

venor’s Exhibit 3). In 1954 Negro parents petitioned the

board to desegregate the schools and again in May, 1965,

Negro parents petitioned for desegregation. The board

did not respond to either petition (R. 125-27, 220-23). On

July 21, 1965, Negro parents and school children brought

suit against the board asking for a preliminary and

permanent injunction against continuing segregation of

students and teaching staffs (R. 14-23). The district

court found there was an illegally segregated system in

Fairfield (R. 84), and pursuant to a court order the board

filed a Plan and later an Amended Plan for Desegrega

tion of Fairfield Schools System (R. 59).13

13 On August 17, 1965, the board filed a Plan for Desegregation of

Fairfield School System (R. 48), which the court failed to approve. This

first plan provided in part that

(1) Negro children in the 9th, 11th, and 12th grades would be permitted

to apply for transfers which transfers would “ be processed and deter

mined by the board pursuant to its regulations . . (R. 49).

(2) Negro children entering the 1st grade would be assigned to Negro

schools, but if both parents accompany the child and sign an application

on the first day o f school, the child would be permitted to apply to a

white school (R. 50, 151-155).

(3) Applications to be acted upon for the 1965-66 term had to be filed

at the office of the board between 8:00 A.M. and 4:30 P.M. on August

30, 1965 (R. 50, 151).

(4) During the 1966-67 terms, the 2nd, 3rd, 8th and 10th grades would

be desegregated. During the 1967-68 terms the remaining 4th, 5th, 6th

22

The amended plan, which the district court approved,

provides that:

(1) Negro students in the 7th, 8th, 10th and 12th would

be allowed to apply for transfer to white schools if their

applications were submitted to the board on or before

August 30, 1965, the applications to be processed by the

board “pursuant to its regulations” (E. 60).

(2) Negro children entering the 1st grade must attend

a Negro school unless the parents of the child on the first

day of school apply for his assignment at a white school

(R. 61).

(3) Applications of Negro children for admission to

white schools or white children to Negro schools are to

be reviewed by the superintendent “pursuant to the reg

ulations of the board” (R. 61). (A similar process is not

required for applications of Negroes for transfer to

Negro schools or white children to white schools.)

(4) During the entire month of May 1966 applications

by Negro children for transfer to white schools in the

2nd, 3rd, 9th, and 11th grades for the 1966-67 school term

will be accepted. (No provision is made for publication

of notice prior to May of 1966) (R. 61-62 and 157-158).

(5) During May of 1967 applications by Negro students

for transfer to the remaining segregated 4th, 5th, and

6th grades will be accepted by the board for the 1967-68

and /th grades would be desegregated. Applications by students entering

desegregated grades would be accepted from the period of May 1 through

May 15 preceding the September school term opening for the desegre

gated grades (R. 50-51).

(5) Unless Negro students applied for and obtained transfer, they

would be assigned to Negro schools (R. 51).

(6) The Board would publish in a newspaper o f general circulation the

provisions o f the plan on three occasions prior to August 30, 1965 (R. 51).

23

school term. (No provision is made for publication of

notice prior to May of 1967) (R. 62 and 157-158).

(6) Except for those students applying for and receiv

ing transfer, the schools within the Fairfield system will

remain segregated.

(7) One notice of the plan is to he published for three

days prior to August 30, 1965 (R. 63).

The plan is silent as to admission of named plaintiffs,

desegregation of faculty and extracurricula activities,

abolition of dual zone lines, and filing of progress reports

with the Court. The plan also does not mention the con

struction and location of new schools and their effect on

desegregation.

Under the plan, transfer applications are not granted

as a matter of course, but the board, in its discretion,

may deny transfer (R. 149, 166).

As understood by school officials, the plan requires both

parents request transfer to a white school before an ap

plication will be considered (R. 150-152). This is also true

for students applying to the first grade, although they are

required to present themselves at schools with an applica

tion signed by both parents and application forms are

not available prior to the time of initial enrollment (R.

153) . Transfer forms are distributed to principals of

schools in Fairfield but are not distributed to parents or

students unless a request is made of the principal (R.

154) . A Negro unable to obtain certain courses because

they are taught only in the white schools will not be

considered for transfer unless the plan covers the grade

in which he is enrolled (R. 159). The plan is also silent

as to the standards to be applied to transfer requests

from students moving into the district subsequent to the

transfer period (R. 158).

24

Prior to desegregation the board permitted applica

tions for transfer during a three-month period but the

desegregation plan reduces this period (ft. 145). When

asked by the district judge to explain why “ such a restric

tive period” had been decided upon the superintendent

stated:

My reaction to that point would be we are moving,

it seems, from a segregated school to an integrated

school system, and the rules of the game are just

going to be different in the future from what they

have been in the past (R. 145).

The record shows that the tangible facilities and ser

vices available at the Negro and white schools are not

equal. The white schools in the City of Fairfield are

organized on a 6-3-3 plan, i.e. the first six grades in an

elementary school; the seventh, eighth, and ninth grades

in a junior high school; and the tenth, eleventh, and

twelfth grades in a senior high school (R. 87, 96, 189-190).

Although the 6-3-3 system is thought to be the most edu

cationally sound school-organization plan by the school

authorities, Negro schools are not organized on a 6-3-3

plan (R. 87, 96, 189-190, 192).

The teacher-pupil ratios for the 1964-65 school term at

the various schools are these:

Grades 1-6

Negro

Robinson 34/Teacher

Englewood 25/Teacher

White

Forest Hills 26/Teaeher

Donald 26/Teaeher

Grades 7-9

Interurban 35/Teacher Fairfield Junior High 28/Teacher

Grades 10-12

Industrial High 29/Teacher Fairfield 20/Teacher

(Computed from Intervenor’s Exhibits No. 3)

25

The plant facilities provided for the Negro children

are inferior to those provided for white students. The

buildings are in disrepair (R. 217-218, 207-210); the lava

tory facilities are unusable, in part, or otherwise of in

ferior quality or condition (R. 108-109 and Defendant’s

Exhibits 7 & 8). Vermin and ants have been found in

eating facilities (R. 161-167, 218) and there is little recrea

tional area provided around the Negro schools while

each white school is provided with ample grounds (R. OI

OS, 97, 98, 210, 211, 212, 218). The per pupil values of

the plant facilities

these:

of the Fairfield school system are

Negro White

Robinson Elementary $ 258 Donald Elementary j ; 743

Englewood Elementary 492 Forest Hills Elementary 920

Glen Oaks Elementary 817

Interurban Junior High 130 Fairfield Junior High 699

Industrial High 1,525 Fairfield High 2,476

(Computed from Defendant’s Exhibit No. 11)

Numerous courses which are offered to the white stu

dents in the junior and senior high schools are not offered

to the Negro students in comparable grades in the various

Negro schools (R. 90, 131-132, 215, 201). A full-time

guidance counselor was provided for the white students

at Fairfield High School and not for the Negro students

at Industrial High School (Intervenor’s Exhibit 3).

On August 23, 1965, the District Court overruled the

objections of the Negro plaintiffs and the United States

and approved the amended plan of the board (R. 65).

On September 8, 1965, the court formalized its findings

and ordered the desegregation of that system pursuant

to the amended plan (R. 67-72). On August 20, 1965,

the court rejected the objections raised by the Negro

plaintiffs and the United States (R. 84). An attempt was

26

made to show that the inferior condition of the Negro,

schools should have some effect upon the rate of desegre

gation and the provisions of the plan, but the district

court held this evidence to be irrelevant (R. 169-170).

On October 22, 1965, the United States filed a Notice

of Appeal from the order of the district court overruling

its objections and approving the plan of the Fairfield

Board of Education (R. 73).

During the 1965-60 school year only 31 of 2,273 Negroes

attended formerly all-white schools.14 15 The Department of

Health, Education and Welfare informs intervenors and

appellants that a total of 49 Negroes attend white schools

during the present school year. None of the system’s

1,779 whites attended formerly Negro schools.16

IV. No. 23,274, United States, et al. v. Caddo

Parish School Board

There are approximately 72 schools under the jurisdic

tion of the board (R. 191) which includes the city of

Shreveport and rural areas of the parish. Attending these

schools are approximately 55,000 children of whom 24,000

are Negroes (R. 191, 189). The board employs approxi

mately 2,200 teachers (R. 191).

Racial separation within the system was maintained

through the use of dual attendance zones (R. 69, 81). No

Negro child attended any school in which white children

were in attendance; no Negro teacher was employed at

any school at which white children were in attendance

(R. 74-75, 81, 91-92). Athletic facilities and bus trans

portation were segregated (R. 107-08, 110-12).

14 Affidavit o f St. John Barrett attached to Motion to Consolidate and

Expedite Appeals filed April 4, 1966.

15 Ibid.

27

After the decision of the Supreme Court in Brown v.

Board of Education, the board made no effort to end

segregation in the schools, being of the opinion that it

had no duty or responsibility to do so until, and only to

the extent that, it was so ordered by a court of the

United States (E. 87-89).

On March 23, 1965, Negro school children and their

parents notified the board that they and other Negro

children desired to attend the public schools of the Parish

without discrimination on the basis of their race (R. 60).

The hoard replied that it had “gone the extra mile” in

its efforts to provide the best education for all students,

but took no affirmative action to desegregate or honor

the request of these Negro children and their parents

(R. 62, 73).

On June 14, 1965, the district court found that the

school board had operated a compulsory segregated sys

tem, enjoined the board from continuing and maintaining

a racially segregated school system, and ordered the

board to submit a plan to desegregate the schools of the

parish (R. 133-36). The court stated that it issued the

decree “not willfully or willingly, but because we are com

pelled by decisions of the Supreme Court . . . [and] . . .

the Fifth Circuit . . . ” (R. 131). The board submitted

a desegregation plan on July 7, 1965 (R. 138-50). Ob

jections were filed July 21, 1965 (R. 158-60) and hearing

was held on the objections August 3, 1965 (R. 161 et seq.).

The board first proposed a plan in which students, after

being initially assigned on the basis o f race, would be

permitted to request transfer to the school closest to their

residence (R. 141). It was established at the hearing that

in many instances this would result in Negro children

applying for transfer from one Negro school (the original

28

assignment) to another Negro school (the school closest

to residence) (R. 273-274).

As a result of the hearing, the plan was approved, as

modified, and incorporated into an order by the District

Court August 3, 1965 (R. 291-98). On August 20, 1965

the district court altered the plan in light of the deci

sion of this Court in United States v. Bossier Parish School

Board, 349 F.2d 1020 (August 17, 1965) (R. 300-04).

The plan as finally approved provides for transfer ap

plications for grades one, two, eleven and twelve during

the 1965-66 school year, remaining grades to he covered

during the 1966-67 and 1967-68 terms (R. 303-04). All

initial school assignments of children entering the first

grade and those presently enrolled from prior years,

would “be considered adequate” subject only to these

transfer provisions (R. 291-95).

The community is to he advised of the plan by publica

tion in a local newspaper advising of the right to request

transfers. There are to he no individual notices.

Negro children in the covered grades could apply for

transfer to white schools only if they applied within a

five-day period extending from August 9, 1965 through

August 13, 1965, although prior to issuance of the plan

transfer applications were permitted throughout the school

year (R. 85, 95, 96). Application forms would not be dis

tributed to all students but would be available from princi

pals on request.

Transfer applications would be granted if in “ the best

interest of the child” and if applicants met transfer criteria

(R. 182, 292-94) such as available space,16 age of the

pupil as compared with ages of pupils already attending

16 AO schools in the Parish are overcrowded (R. 258-59, 281).

29

the school to which transfer is requested, availability of

desired courses of instruction, and an aptitude test (E.

147, 217, 243-48). These criteria are part of “ the pro

cedures pertaining to transfers currently in general use

by the Caddo Parish School Board” and are incorporated,

in the plan (E. 292). An interview may be required and

if parents fail to attend the transfer application is con

sidered withdrawn (E. 145, 146).

The board specifically refused to obligate itself to pro

vide busing for transfer students to formerly all-white

schools although in some cases this would require students

to arrange trips of about 19 miles (E. 70, 143, 206).17

The board was granted the right to reassign a transfer

applicant to a “ comparable” school nearer his residence.

However, “comparable” is not defined in the plan.

Students moving into the parish are initially assigned

according to race to formerly all-white or all-Negro schools

(E. 177-78, 295).

The order did not provide for assignment of named

plaintiffs to white schools or for desegregation of faculty,

extracurricular activities or transportation facilities. Prog

ress reports to the court are not required. A spring pre

registration of future first graders “ is very important”

(E. 95, 94) to administration of the system but the plan

is silent regarding its desegregation. The plan does not

mention the construction and location of new schools and

their effect on desegregation.

During the first year of the plan’s operation, only one

Negro child of the 24,457 attending public schools in Caddo

17 There was testimony that all or nearly all the white children from

the rural area of Caddo Parish were bussed into Shreveport from as much

as 19 miles away. Rural Negro children were provided with three Negro

high schools located at various points about the county closer to their

residence than the Shreveport schools (R. 274-75).

30

Parish (of whom approximately 1,720 are entering first-

graders) has been admitted to a formerly white school

(E. 78). (See the affidavit of Mr. St. John Barrett attached

to motion to consolidate and expedite filed in this Court

April 4, 1966).

July 19, 1965, the United States sought leave to inter

vene as of right as party plaintiff and to file objections

to the desegregation plan submitted by the board. At the

August 3, 1965 hearing on the plan, the district court

denied the motion to intervene (E. 166) on October 4, 1965,

the United States filed notice of appeal to this Court from

the order denying intervention (E. 305). The panel found

that “ the motion was timely filed and should have been

granted” (Slip Opinion p. 116).

V. No. 23,365, United States of America, et al. v.

The Bossier Parish School Board

This is the fourth appeal to this Court involving segre

gation in the Bossier Parish schools. See United States v.

Bossier Parish School Board, 220 F. Supp. 243 (W.D. La.

1963), aff’d per curiam 336 F.2d 197 (5th Cir. 1964), cert,

den. 379 U.S. 1000, an unsuccessful attempt by the United

States to sue for desegregation prior to the 1964 Civil

Eights Act. See also two prior appeals in the present

suit, sub nom. United States v. Bossier Parish School Board,

349 F.2a 1020 (5th Cir. 1965) (per curiam) and Bossier

Parish School Board v. Lemon, No. 22,675, 5th Cir., Janu

ary 5, 1967 (not yet reported).

This suit was commenced in December 1964 by a group

of Negro servicemen and their families who were assigned

to the Barksdale Air Force Base near Bossier City, Louisi

ana; the United States intervened and brought this appeal.

31

The present appeal involves the “ adequacy,” underBrown

v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 297, 301, of a court-ordered

plan of desegregation (R. Yol. II, 251-258; as amended R.

Yol. II, 261-263). (NB The record on this appeal is in

two volumes. Volume I consists of the record multilithed

for use in 5th Cir. Case No. 22,675, a prior appeal. Volume

II is marked as Case No. 23,365 and consists of 281 pages.)

Bossier Parish, which adjoins Caddo Parish in north

west Louisiana, is a rapidly growing area (R. 11-40) which

embraces both urban (Bossier City) and rural areas and

several large federal installations, including the Barksdale

Air Force Base. Its Superintendent of Schools described

the system as the most federally impacted system of its

size in the South (R. 11-38). The Superintendent also de

scribed the areas as a “hard core segregation area” where

people have “ strong and fixed opinions in opposition to

integration,” and said in March 1965 that “Bossier Parish

is not ready for integration” (R. 1-56).18

The school system had (in the spring of 1965) 15,267

students, including 10,894 white pupils and 4,375 Negroes, * 66

18 The quoted remarks are from a written answer to an interrogatory

inquiring what obstacles there were to complete desegregation in the 1965-

66 term (R. Vol. I, 40). The Superintendent responded (R. Yol. I, 56)

with the following:

Bossier Parish, Louisiana can properly be termed a “ hard core”

segregation area. The people in Bossier Parish have strong and fixed

opinions in opposition to integration. People here feel that negroes

in Bossier Parish are treated fairly and with justice and there has

been an unusual degree of racial harmony. Indeed, from the negroes

in Bossier Parish there has been no desire expressed for integration

of the races other than that which come from Barksdale Air Force

Base; that is, from non-Bossier Parish negroes.

In contrast to some other areas o f the South which have maintained

segregated school systems, Bossier Parish is not ready for integration.

/ s / E mmett Cope

E mmett Cope, Individually and

on behalf o f the Bossier Parish

School Board

32

in 23 school buildings (R. Vol. I, 45-46). There were 17

all-white and 6 all-Negro schools (Ibid.). About 1,100

students live on the Barksdale Air Force Base, and ap

proximately 4,400 students are “ federally connected” (R.

Yol. II. 36). The student population has a large turnover

which includes an average of 1,000 to 1,500 newcomers

each year, largely due to the federal installations and re

lated industries (R. Vol. II. 38). The system received more

than $1,860,000 for school construction from the Federal

Government between 1951 and 1964 (R. Vol. I. 104), and

also received substantial annual amounts of federal funds

for maintenance and operation of the schools, including

more than half a million dollars in November 1964 (R. Vol.

I. 108).

There was no desegregation of the Bossier schools until

September 1965 when twenty-five (25) Negroes were ad

mitted to six previously all-white schools (R. Vol. II. 266).

Until 1965, the schools were completely segregated with

a system of dual school zones for Negroes and whites (R.

Vol. II. 43-45). The 700 teachers in the system were also

assigned on the basis of race (R. Vol. II. 175, 179). In

school taxation district 13, the urban area, all Negro

children, regardless of residence, were assigned to either

Butler School (grades 1-6) or Mitchell School (grades 7-

12) (R. Vol. I. 45-46; Vol. II. 160). White pupils in dis

trict 13 were assigned to elementary, junior high or high

schools on the basis of geographic attendance areas re

flected on maps which were revised annually to adjust to

changing conditions (R. Vol. II, 44, 67-69, 159-161, 168).

Similarly, there were dual zones in the rural areas, all

pupils having been assigned on a dual zone racial basis

(R. Vol. II. 127, 130). Under the segregated system pupils

were placed in schools by assignment and not by choice

(R. Vol. II. 130). The board also maintained separate

33

school buses, and bus route maps for Negroes and whites

(R. Yol. II. 244-245).

After the trial judge in April 1965 ordered the board

to submit a desegregation plan, the board appealed that

order19 but, as there was no stay in effect, submitted three

alternative proposals for desegregation (R. Vol. II. 1-12).

None of the proposals involved a start of desegregation

until 1966, and the proposed completion dates ranged from

1970-71 (the board’s first choice) to 1968-69. We omit any

detailed description of the board’s proposed plan, except

to state that under the proposal all prior initial assign

ments— all of which were segregated—were “ considered

adequate” , subject to a pupil’s right to transfer to “ the

nearest formerly all-white or all-colored school” (R. II. 4).

Although the plan was labeled as one considering both

“ freedom of choice” and “proximity” by the superintendent

(R. Yol. II. 92), all Negro first graders were directed to

register at the all-Negro Butler School and white children

were directed to the white schools. The superintendent

sought to justify this by his assumptions that the major

ity of Negroes would want to go to Butler, and that they

would get better registration advice from teachers of their

own race (R. Vol. II. 124-125). The private plaintiffs and

the United States filed objections to the plan (R. Yol. II.

13-15, 30-33), and a hearing was held on July 28, 1965.

On July 28, 1965, the District Court entered an order re

quiring desegregation in September 1965, in grades 1 and 12

(R. Vol. II, 251-258). The United States promptly appealed

(R. Yol. II, 258), and this Court within a few weeks vacated

the judgment and remanded for reconsideration (R. Vol.

19 This court rejected the board’s arguments on appeal calling them

a “ bizarre excuse” for segregation. Bossier Parish School Board v. hemon,

No. 22,675, 5th Cir., January 5, 1967. Undaunted, the board promptly

filed a rehearing petition, still resisting the order to desegregate in Janu

ary 1967. Rehearing was denied February 6, 1967.

34

II, 260; see 349 F.2d 1020). The plan was then amended hy

the trial judge to permit desegregation in two additional

grades in 1965 (R. Vol. II, 261-263). There were no other

changes in the plan, and the United States then brought

this appeal, in which the private plaintiffs were permitted

to intervene.

The Court Ordered Plan, as Amended

(R. Vol. II, 251-258, 261-263)

•F

1. Rate of desegregation.

The plan, as amended, provides for desegregation in three

years, as follows:

School Year Grades Desegregated

The plan also provided that all pupils newly entering

the school system would he eligible for desegregation in 1965

without regard to their grades (R. Vol. II, 255).

2. Method of assignment.

a. 1965-66 school year. Initial assignments, already made

on a completely segregated dual racial zone basis were “con

sidered adequate” subject to certain transfer rights (R. Vol.

II, 251). Transfer provisions for the various grades af

fected were as follows:

Grade 1—Notice to be published in newspaper for three

days advising that applications to first grade in any school

could be made by applying in person at school board office

during four day period (R. Vol. II, 252-25 ). As imple

mented, the board ran a notice of this provision for “Any

Negro child . . . who desires to attend a formerly all-white

1965- 66

1966- 67

1967- 68

1, 2, 11, 12

1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12

All Grades

35

school” to apply in person at the school hoard office in

Benton, Louisiana accompanied by his parents or guardian

(R. Yol. II, 271).

Grades 2 and 11—The procedure prescribed in the order

was similar to that for grade 1. The board’s newspaper

notice, said that “Any Negro child .. . who desires to attend

a formerly all white school, will report . . . in person, ac

companied by his or her parents or guardian to the School

Board office at Benton, Louisiana.” A three-day period was

prescribed (R. Vol. II, 273).

Grade 12— The order provided that all 12th grade stu

dents, regardless of race, were to be mailed notices advising

of the right to transfer to any school by applying in person,

accompanied by parents, during a four day period (R. Vol.

II, 252). The notice actually mailed to pupils (R. Vol. II,