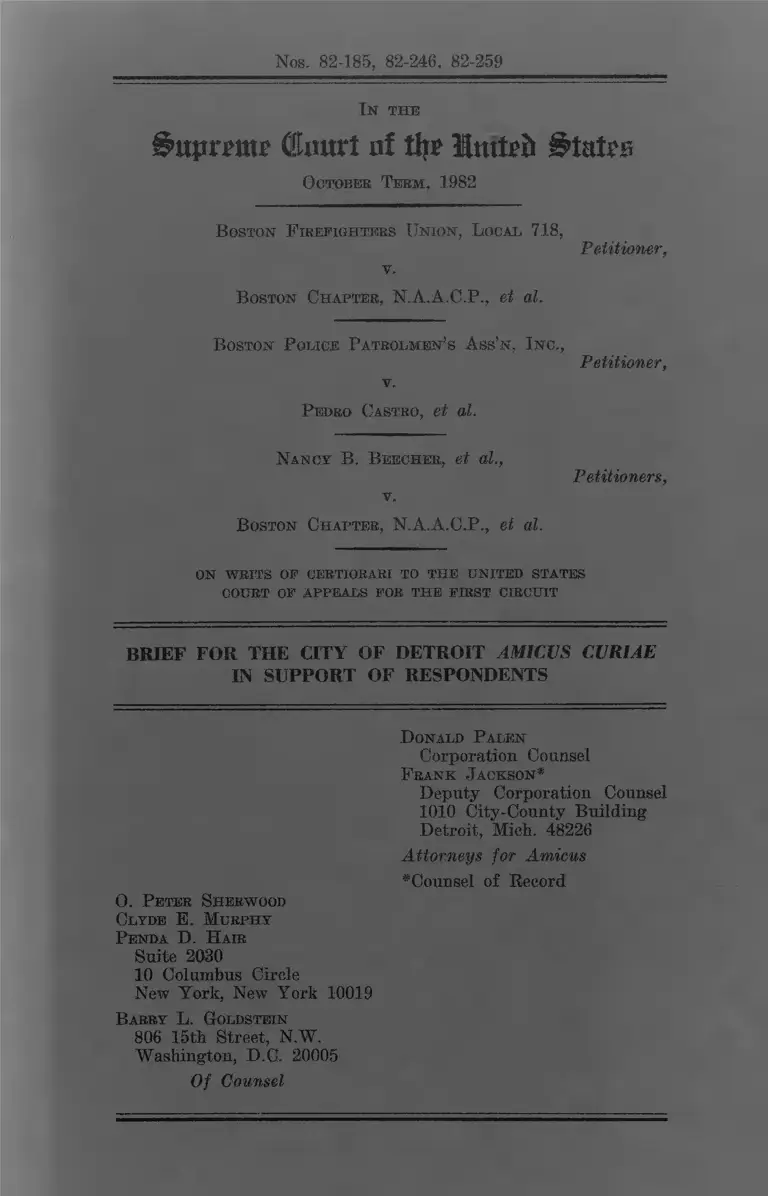

Boston Firefighters Union v. Boston Chapter, NAACP Brief for the City of Detroit Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boston Firefighters Union v. Boston Chapter, NAACP Brief for the City of Detroit Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1982. 04c0252f-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e2c3890d-f999-4ad3-95dc-1055371b4707/boston-firefighters-union-v-boston-chapter-naacp-brief-for-the-city-of-detroit-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 82-185, 82-246, 82-259

In t h e

Bnpremt (fiwrt nt % lutfrib BMzb

October Teem, 1982

B oston F irefighters Union, L ocal 718,

Petitioner,v.

Boston Chapter, N.A.A.C.P., et at.

Boston P olice P atrolmen’s Ass’n , I nc.,

Petitioner,

v,

P edro Castro, et al.

Nancy B. Beecher, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

B oston Chapter, N.A.A.C.P., et al.

ON WRITS OP CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOE THE CITY OF DETROIT AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

D onald P alen

Corporation Counsel

F rank -Jackson*

Deputy Corporation Counsel

1010 City-County Building

Detroit, Midi. 48226

Attorneys for Amicus

^Counsel of Record

0 . P eter Sherwood

Clyde E. Murphy

P enda D. H air

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Barry L. Goldstein

806 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities ............... i

Interest of Amicus ................. 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...... 3

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISCRETION EXERCISED BY THE

DISTRICT COURT IN THIS CASE

SERVED TO FACILITATE CRITICALLY

IMPORTANT PUBLIC SAFETY CON

SIDERATIONS ................... 5

II. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER IS

THE MOST FLEXIBLE AND LEAST

INTRUSIVE MEANS OF ACHIEVING

THE GOALS OF TITLE VII ........ 20

III. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER IS

CONSISTENT WITH SECTIONS

703(h) AND 706(g) OF TITLE

VII ................. 31

A. Statutory Preferences Are

Not Protected by 703(h) .. 31

B Section 703(h) Defines

What Constitutes A

Violation of Title

VII. It Does Not Limit

The Scope of Remedial

Orders .................. 38

C. Title VII Authorizes

Affirmative Remedies ..... 40

D. The District Court's Order

Is Consistent With Section

706(g) .................... 54

i

Page

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER

IS CONSISTENT WITH THE FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENT ............... 56

Conclusion ...... 60

Appendix ........... 1a

- ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Adams v. United States ex rel McCann,

317 U.S. 269 (1942).............. 24

Aeronautical Lodge v. Campbell, 337

U.S. 521 (1949).................. 35

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 (1975) .................. 20

American Tobacco Co., v. Patterson,

U.S. 71 L.Ed.2d 748

(1982) .......... 32,35,39

Ass'n Against Discrimination v. City

of Bridgeport, 647 F.2d 256 (2d

Cir.) cert, denied, 454 U.S. 897

(1981)......................... 42

Baker v. City of Detroit, 483 F. Supp.

930 (E.D. Mich. 1979)...... 3,16,17,18

Bonner v. City of Pritchard, 661 F.2d

1206 (11th Cir. 1981)..... 43

Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc. v. Beecher,

504 F.2d 1017 (1st Cir. 1974),

cert, denied, 421 U.S. 910

(1975)......... 24,42

Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc. v. Beecher,

679 F.2d 695, cert. granted sub

nom., Boston Firefighters Union,

Local 718 V. Boston Chapter,

NAACP, U.S. , 103 S.Ct.

293 ( 1982) .................. 24,42

Bridgeport Guardians Inc. v. Members

of the Bridgeport Civil Service

Comm., 482 F.2d 1333 (2d Cir.

1973)................ ............ 9

- iii

Cases; Page

California Brewers Association v.

Bryant, 444 U.S. 598 (1980)....- 35,39

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315

(1971)......................... . 22,29

Castro v. Beecher, 334 F. Supp. 930

(D. Mass. 1971), aff'd in part andrev'd in part, 459 F.2d 725

(1st Cir.), on remand, 365

F. Supp. 655 ( 1 973) ............. 8,9

Castro v. Beecher, 522 F. Supp. 873

(D. Mass. 1981), aff *d sub nom. ,Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc. v.

Beecher, 679 F.2d 965 (1st

Cir. 1982), cert. granted sub

nom., Boston Firefighters

Union, Local 718 v. Boston

Chapter, NAACP, Inc., U.S.

, 103 S.Ct. 293 (1982) ... 9,26,29,31

Chisholm v. United States Postal

Service, 665 F.2d 482 (4th Cir.

1981).................... 42

Contractors Association of Eastern

Pennsylvania v. Secretary of Labor,

442 F.2d 159 (3d Cir. 1971), cert,

denied 404 U.S. 854 (1971)........ 49

Davis v. City of Los Angeles, 566

F.2d 1334 (9th Cir. 1977), vacated

on other grounds, 440 U.S. 625 (1979)....... 43

Detroit Police Officers Assn. v.

Young, 608 F.2d 671 (6th Cir. 1979) cert. denied 452 U.S. 940

(1981) ............. 2,9,11,43

xv

Cases: Page

EEOC v. American Telephone & Telegraph

Co., 556 F.2d 167 (1977), cert,

denied, 438 U.S. 915............. 42,

EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co., 515 F.2d

301 (6th Cir. 1975), vacated on other grounds 431 U.S. 951

(1977) ........................

EEOC v. Longshore (ILA), Locals 829

and 858, F. Supp. , 9 E.P.D.

II 10,159 (D. Md. 1975)..........

EEOC v. Plummer & Pipefitters Local

189, 438 F.2d 408 (6th Cir.1971) . ...........................

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1977)..... 32,34,37,39,

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448

(1980).................. 43,56,57,

Harris v. Nelson, 394 U.S. 266

(1969).........................

International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 324(1977) .................. 32,34,37,

James v. Stockham Valves and Fittings

Co., 559 F.2d 310 (5th Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1034

(1978) .......................

Local 53, Asbestos Workers v. Volger,

407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969)___

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S.

145 (1964)...................... 21,

45

43

23

23

41

59

24

39

42

49

29

v

Cases: Page

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39

(1971)........................... 58

NAACP, Detroit Branch v. Detroit

Police Officers Assn., 525 F. Supp.1215 (E.D. Mich. 1981)........... 3

North Carolina Board of Education v.

Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971)...... 58

Pullman Standard v. Swint, U.S.

, 102 S.Ct. 1781 (1982)....... 39

Regents of the University of California

v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265

(1978) ........................ 43,56,59

Rios v. Enterprise Association of

Steamfitters Local 638, 501 F.2d

622 (2d Cir. 1974)............... 42

Southern 111. Builders Ass'n v.

Ogilvie, 471 F.2d 680 (1972)..... 49

Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193

(1979) ......... 41,44,48

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971).. 58

Talbert v. City of Richmond, 648 F„2d

925 (4th Cir. 1981), cert, denied

454 U.S. 1145 (1982) ........... 9

Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257 (D.C.

Cir. 1982).................. 43

United States v. City of Chicago, 549

F.2d 415, cert, denied, 434 U.S. 875

(1977)...... .................... 43

vx

Cases: Page

United States v. Hall, 472 F.2d 261

(5th Cir. 1 972)................ 22

United States v. International Brother

hood of Electrical Workers, Local

38, 428 F.2d 144 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 943 (1970)..___ 42,49

United States v. International Union

of Elevator Constructors, Local 38,

538 F.2d 1012 (3d Cir. 1975)..... 42

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86,

443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir.), cert,

denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971).... 49

United States v. Lee Way Motor

Freight, Inc., 625 F.2d 918 (10th

Cir. 1979).................... . 43

United States v. New York Telephone

Co., 434 U.S. 159 (1977)________ 24

United States v. N.L. Industries,

Inc., 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir.1973)........................... 43

United States v. Swift and Company,

286 U.S. 106 (1932) .............. 22,23

United States v. United Brotherhood of

Carpenters and Joiners, Local 169,

451 F.2d 210, cert, denied, 409U.S. 851 (1972)........... 49

United States v. United Shoe Machinery

Corp., 391 U.S. 244 (1968)....... 23

Van Aken v. Young, 541 F. Supp.

448 (E.D. Mich. 1982)... 19

- vii -

Cases: Page

Washington v. Fishing Vessel Ass'n,

443 U.S. 658 (1979)...... ....... 29

Williams v. The City of New Orleans

694 F.2d 987 (5th Cir. 1982) ... 41

Zipes v. Trans World Airlines,

U.S. , 71 L.Ed„2d 234 (1982).. 40

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes

and Regulations;

United States Constitution,

Fourteenth Amendment............. 56

28 U.S.C. § 1651................... 23

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, et seq........ passim

42 Op. Att'y Gen. No. 37 (Sept. 22,

1969)........___................ 41

Uniform Guidelines on Employee

Selection Procedures, 29 C.F.R.

§ 1607. .......... 41

Mass. Gen. Laws, ch. 30 § 9A...... 33

Mass. Gen. Laws c. 31, § 39........ 25

Oregon House Bill 3306, Feb. 22,

1982. ........ 27

Arizona Senate Bill 1005 Jan. 1,

1982. . ........... 27

Detroit City Chapter, § 7-806...... 19

- viii

Page

Legislative History:

110 Cong. Rec. 6548 (1964)........ 46

110 Cong. Rec. 7207 (1964)........ 34

118 Cong. Rec. 7214 (1964)........ 46

110 Cong. Rec. 7217 (1964)........ 34

117 Cong. Rec. 321 1 (1971 )___ ..... 50

118 Cong. Rec. 2298 (1972)........ 54

118 Cong. Rec. 578 (1972)........ 52

118 Cong. Rec. 7166 (1972)........ 52

118 Cong. Rec. 789-811 (1972)..... 14

118 Cong. Rec. 1676............... 51

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1963).................... 33

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, 92nd Cong.,

1st Sess. (1971)................ 14, 50

S.Rep. 92-415, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess.

(1971) at 10.................... 13,53

Legislative History of Title VII

and XI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964.............. 33

Legislative History of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of

1972............................ 14,15

xx

Other Authorities: Page

Aaron, Reflections on the Legal

Nature and Enforcement of Seniority

Rights, 75 Harv. L. Rev. 1532

(1962)............. . 19

Brief for Petitioners the United

States and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Steelworkers

v. Weber, No. 76-432............. 41,46

Brief for United States and the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission

as Amici Curiae, Minnick v. Calif.

Dept, of Corrns., No. 79-1213 .. 6

Leonard Greenhalgh, A Cost Benefit

Balance Sheet For Evaluating

Layoffs As A Policy Strategy,

October 1, 1978.................. 28

Legislative History of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of

1972...... ..................... . 14

Legislative History of Title VII and

XI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

(hereinafter Legislative History)

2071. ..................... 33

Moran and McPherson, Union Leader

Responses to California's Work

Sharing Unemployment Insurance

Program, Bureau of National Affairs,

Daily Labor Report, Vol. 102, D.

1 (May 28, 1981)............. 27,28

Short Time Compensation Act, P.L.

92-248, Part of the Tax Equity Act

of 1982, Section 194....... . 28

X

Other Authorities: Page

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures (Policy Statement on

Affirmative Action), 29 C.F.R.

§ 1607.......................... 41

U.S., Civil Rights Commission on

Confronting Racial Isolation in

Miami (1982), p. 290............ 12

U.S., Commission on Civil Rights, Who

Is Guarding the Guardians: A Report

On Police Practices (1981), p.... 12

Vass, Title VII: Legislative History,

70 B.C. Ind. & Comm. C. Rev. 431(1966)..................... 47

xi

Nos. 82-185, 82-246, 82-259

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1982

BOSTON FIREFIGHTERS UNION, LOCAL 718,

Petitioner,

v.

BOSTON CHAPTER, NAACP, et al.

BOSTON POLICE PATROLMEN'S ASSOCIATION, INC.,

Petitioner,v.

PEDRO CASTRO, et al.,

NANCY B. BEECHER, et al.,

Petitionersv.

BOSTON CHAPTER, NAACP, et al.

On Writs of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals For The First Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE CITY OF DETROIT AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Interest of Amicus

The City of Detroit has suffered

2

adverse consequences because of prior

discriminatory practices of its public

safety agencies particularly its Depart

ment of Police and a failure to correct

the effects of that discrimination.

For the past nine years Detroit has

implemented affirmative action plans to

eradicate the effects of past discrimina

tion against minorities and the debilitat

ing effects of that discrimination on

the ability of its public safety agencies

to operate effectively. The outcome of

this case may have a crucial impact on

the lawfulness of those plans. Presently

pending in the lower courts are two cases

brought on behalf of white police officers

which challenge the lawfulness of Detroit's

race-conscious affirmative action plan

in the police department. See Detroit

Police Officers Assn, v. Young, 608 F.2d

671 (6th Cir. 1979) cert. denied, 452 U.S.

3

938 (1981) and Baker v. City of Detroit,

483 F. Supp. 930 (E.D. Mich. 1979). In a

third lawsuit, NAACP, Detroit Branch v.

Detroit Police Officers Assn., 525 F. Supp.

1215 (E.D. Mich. 1981) the City and the

union representing police officers are

being sued for failure to agree on workable

alternatives to the collectively bargained

reverse seniority sequence order of lay

offs. That failure has had the effect of

undoing some of the hiring gains achieved

through implementation of the City's

affirmation action plan. We believe that

Detroit's experience with undoing the

effects of longstanding racial discrimina

tion by means of affirmative action may

provide an important perspective to the

issues presented in this case.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case raises important questions

concerning the discretion of a district

4

court to preserve gains made pursuant to a

remedial consent decree where fiscal

considerations require a municipal govern

ment to achieve economies. In this case

the employer elected initially to effec

tuate these economies through the expedient

of layoffs which, under state law, could

only be made in reverse sequence seniority.

After the district court barred

layoffs in a manner which adversely affect

ed minorities and which undid gains made

under nearly a decade of court ordered

remedies, the employer managed to solve its

financial problems without laying off any

employees. If, as petitioners argue, the

district court were stripped of its

equitable powers, then the catalyst — ■ the

order of the district court — to a crea

tive solution which averted layoffs would

have been absent. Moreover, important

public safety benefits derived from having

5

public safety institutions which reflect

the racially diverse character of the

community served would have been sacri

ficed. Neither Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§2000e, et seq. nor the Fourteenth Amend

ment of the United States Constitution

requires a result that would strip a

district court of the power to preserve

remedial gains particularly where, as here,

larger public interests are at stake.

I. THE DISCRETION EXERCISED BY THE

DISTRICT COURT IN THIS CASE SERVED

TO FACILITATE CRITICALLY IMPORTANT

PUBLIC SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS_______

Petitioners' contention that the

seniority expectations of non-minority

officers may not be upset except to the

extent necessary to slot in proven victims

of unlawful racial discrimination^ see

]_/ Some of the amicus briefs filed

on behalf of petitioners take similar

6

e .g . Brief of Petitioner

Patrolman's Assn., at 18

Boston Police

would stifle

continued

positions . £5 £e>, e ^ ^ B r i e f For The

United States, 20. This claim on the

part of the United States contrasts sharply

with positions it has taken in the past in

this Court. For example in Minnick v.

California Dept, of Corrections , No.

79-1213, at p. 20, the United States and

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission advised this Court that:

[a] state agency is not confined

merely to seeking to identify individual victims of past discriminatory

decisions and, if it finds them,

affording relief on a case-by-case

basis. As Congress so plainly recog

nized when it extended Title VII to

state and local governments, the

effects of employment discrimination

in this setting extend well beyond the

loss of employment opportunites by

particular individuals. Such dis

crimination deprives the agency of the

perspective of minority persons re

garding the impact of its programs

on minorities? it fosters distrust on

the part of minorities of governmental

functions carried out by personnel

who are not representative of the

community at large, thereby perhaps

deterring minorities from full parti

cipation in government programs; and

it sets a highly visible example of

7

efforts to end the mistrust and antagonisms

that have developed in our cities between

law enforcement agencies and minority-

citizens as a result of long-standing

policies and practices of exclusion of

minorities from employment in such agen

cies. Reliance on reverse seniority

sequence layoffs as the only means of

addressing Boston's fiscal crisis would

serve to resegregate these agencies and

thereby exacerbate existing racial ten

sions .

]_/ continued

discrimination, or acquiescence in the

results of past discrimination. In

order to remedy these broader effects

of discrimination, the agency may

appropriately take measures designed

to bring minority representation in

its work force to the same percentage

that obtains in the relevant labor

market, and thereby to place the agency in the position it presumably

would have been in had there been no

discrimination.

8

When the first of these cases,

Castro v. Beecher , Civil Action No.

70-1220-W, was filed, the existence of an

on-going hostility between the Boston

police and that city's minority commu

nity was immediately apparent and that

hostility affected the willingness of

minority citizens to apply for employ

ment. See Castro v. Beecher , 334 F .

Supp. 930, 936 (D. Mass. 1971) and 365

F. Supp. 655, 659 (1973). The district

court recognized the need to end this

unfortunate alienation between citizens and

the police as well as the general positive

effect on the public interest to be ac

hieved by a police force which reflects

the racial diversity of the community.

9

See, e„g., Castro v. Beecher, 365 F. Supp.

659 and 522 F. Supp. 873, 877 (1981).

Moreover, the First Circuit stated:

We do not need expert testimony to make the point that, unless the public

safety departments of a city reflect

its growing minority population, there

is bound to be antagonism, hostility,

and strife between the citizenry and

those departments. The inevitable

result is poor police and fire protec

tion for those who need it the most.

679 F.2d at 977.

Other courts of appeals have agreed

2/with the First Circuit.— The Sixth Cir

cuit recently collected and summarized the

many studies that make the importance of

having racially representative police

forces in our cities judicially noticeable.

2/ See Detroit Police Officers Assn, v.

Young, 608 F.2d 671 , 695 (6th Cir. 1 979);

Talbert v. City of Richmond, 648 F. 2d 925,

931 (4th Cir. 1981); Bridgeport Guardians

Inc, v. Members of the Bridgeport Civil

Service Comm., 482 F.2d 1333, 1341 (2d Cir.

1973).

The operational need to have a minority

presence in public safety agencies that

is representative of the miniority popula

tion of the community served:

is based on law enforcement expe

rience and a number of studies

conducted at the highest levels.

E.g., National Advisory Commission

on Criminal Justice Standards and

Goals, Pol ice (1 973); National Commis

sion on the Causes and Prevention of

Violence, Pinal Report: To Establish

Justice, To Insure Domes tic Tran

quility (1969); Report of the National Advisory Commission an Law Enforcement

and Administration of Justice, Task

Force Report: The Police (1967). As

these reports emphasize, the relation

ship between government and citizens

is seldom more visible, personal and

important than in police-citizen

contact. See To Establish Justice,

supra at 145; Report on Civil Dis

orders , supra a 300 (New York Times

edition). It is critical to effective

law enforcement that police receive

public cooperation and support.

Report on Civil Disorders, supra at

301; Task Force Report: The Police,

supra at 144-45, 167; Police, supra at

330.

These national commissions recommend the recruitment of addi

tional numbers of minority police

officers as a means of improving

community support and law enforcement

effectiveness. In fact, the benefits

of Negro officers were recognized as

early as 1931 by the "Wickersham

Commission." Report on the Causes of

Crime 242, National Commission on Law Observance and Enforcement (Vol.

I, 1931 ) .

In 1967, a presidential commis

sion stated the proposition offered by

the defendants in this case:

In order to gain the general

confidence and acceptance of a community, personnel within a

police department should be repre

sentative of the community as

a whole.

Detroit Police Officers Assn., 608 F.2d at

695. More recently completed studies have

reached the same conclusion. In a report,

published in October 1981, the United

States Commission on Civil Rights found:

Finding 2.1; Serious underutiliza

tion of minorities and women in

local law enforcement agencies con

tinues to hamper the ability of police

departments to function effectively

12

in and earn the respect of predomi

nantly minority neighborhoods, thereby increasing the probability of tension

and violence.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Who Is

G u a rding the Guardians:__A Report On

Police Practices 5 (1981). Following an

investigation into the May 1 980 racial

disturbance in Miami, Florida the U.S.

Civil Rights Commission observed:

In Dade County, an essentially

white system administers justice to

a defendant and victim population

that is largely black. The lack of

minorities throughout the criminal

justice system maintains the percep

tion of a dual system of justice.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Confront

ing Racial Isolation In Miami 290 (1982).

Congress was acutely aware of the

deleterious community effect of maintenance

of segregated employment patterns in

government and it identified the need to

remedy this condition as one of the pur-

13

poses of the 1 972 amendment to Title VII.

When Title VII was amended in 1972 to cover

state and local governments, the accompany

ing Report of the Senate Committee on Labor

and Public Welfare stated that

The failure of State and local

governmental agencies to accord

equal employment opportunities is

particularly distressing in light

of the importance that these agencies

play in the daily lives of the average citizen. From local law enforcement

to social services, each citizen is in

constant contact with many local

agencies. . . . Discrimination by

goverment therefore serves a doubly

destructive purpose. The exclusion of

minorities from effective participa

tion in the bureaucracy not only

promotes ignorance of minority prob

lems in the particular community, but

also creates mistrust, alienation, and

all too often hostility towards the

entire process of government.

S. Rep. 92-415, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess. 10

(1971). Congress was particularly con

cerned with protecting the operational

ability of police departments to provide

effective law enforcement.

1 4

The problem of employment discrimi

nation is particularly acute and

has the most deleterious effect in

those government activities which

are most visible to the minorit

communities (notably education, la

enforcement, and the administration

of justice) with the result that the credibility of the government's

claim to represent all the people

is negated. H. R. Rep. No. 92-238,

92nd Cong., 1st Sess. 17 (1971).

Senator Harrison Williams, chairman

of the Labor and Public Welfare Commit

tee and sponsor of the bill in the Senate,

emphasized strongly the Congressional

concern for the ability of units of state

and local government to carry out their

assigned responsibilities. He stated that

the Committee had acted out of a belief

that their work was "essential to the

viability of State and local governmental

units" 118 Cong. Rec. 789-811 (1972),

reprinted in EEOC, Legislative History of

the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972, at 1116 (hereinafter 1972 Legislative

1 5

History.) The Committee's concern with

employment discrimination was based, in

large part, upon the unfavorable impact

which it had on "the ability of . . .

governmental units to deal equitably in

their contacts with those groups against

whom they discriminate in employment."

Id. As Senator Williams succinctly phrased

the matter, "if they are to carry out their

jobs with any success whatever, public

confidence in their impartiality is vital."

Id. This expressed Congressional solicitude

for protecting the ability of local govern

mental units to carry out their essential

functions requires a construction of Title

VII that permits use of racial criteria,

when needed, to assist in the provision of

public safety services.

Amicus has experienced — and federal

court records document, see Baker, 483 F.

Supp. at 996-97 — racially-based police

community tensions caused in substantial

16

part by years of neglect in the recruit

ment, hiring and advancement of black

public safety officers. Major riots in

1943 and 1967 as well as several other less

noted civil disturbances before and after

1 967 were just one of the many manifesta

tions of the breakdown of police community

relations. Prior to 1974, six to eight

Detroit police officers were killed in the

line of duty each year. Moreover the

widespread belief in Detroit’s black

community that the police lacked interest

in investigating black on black crime

resulted in a loss of essential black

citizen cooperation in the police depart-

3 /ment's crime fighting efforts.-' Id .

See Baker 483 F. Supp. at 996-97.

3/ In the appendix to this brief we have

reproduced the district court's fuller

description of these events. See Appendix

pp. 1a-5a.

The willingness of amicus to recognize

and act on the destructive consequences of

failure to correct the extreme under-utili

zation of black officers came painfully.

The riots in 1967 jolted the City of

Detroit into a realization that something

would have to be done to correct these

imbalances. See 483 F. Supp. 946. Between

1967 and 1973 some efforts were made to

recruit, hire and promote blacks, but these

efforts were not successful. 483 F .

Supp. at 447-52. In the interim the City

continued to hemorrhage. See 483 F. Supp.

at 996-99. Finally, in 1974, the City

adopted a voluntary affirmative action

plan of hiring and promotion. These

efforts have resulted in dramatic improve

ments in the ability of amicus to deliver

effective police service.

In Baker the district court detailed

4/these improvements and concluded:—

There is clear evidence in the

record that before 1974 there existed

enormous tension between the Depart

ment and the black community. There

is clear evidence in the record that

after the institution of the affirma

tive action program, police-community

relations improved substantially,

crime went down, complaints against

the Department went down, and no

police officers were killed in the

line of duty. High ranking police

officials attributed this change to

the affirmative action program and

its general aim of having the Depart

ment -- at all levels -- reflect the

City's population.

483 F. Supp. at 1000.

In the experience of amicus the

ability to make race conscious employ

ment decisions has been the critical

ingredient in efforts to restore community

trust in Detroit's public safety agencies

and to facilitate Detroit's ability to pro

tect the lives and property of its people.

See _id. , 483 F. Supp at 999.

4/ We have set forth in the appendix, pp.

5a-8a, the full text of the portion of the

opinion detailing these improvements.

Detroit, and we suspect all municipalities,

approached the point of decision slowly

and with maximum caution, for the path to

that decision and the road beyond it

are covered with political, practical

5 /and legal o b s t a c l e s . A s the district

court's summary of the breakdown of police

community relations in Detroit shows,

5/ For example, amicus has attempted to

implement an affirmative action plan in

its fire department. Initially we were

unable to proceed because of an archaic

City Charter provision which required that

promotions up to the rank of Deputy Fire

Commissioner be filled on the basis of seniority. See Detroit City Charter, §

7-806. As a result that department was

saddled with many undistinguished and unproductive supervisors at virtually all

levels. This system of advancement served

primarily to perpetuate the prior racially

exclusionary practices of that department.

Cf. Van Aken v. Young, 28 F.E.P. Cases 1669

(E.D. Mich 1982). After several years of effort the voters approved a charter

amendment which substituted a merit system

for promotions. Despite this change the

City has not been able to implement the new

merit plan due to an ongoing arbitration

proceeding instituted by the union which

represents firefighters.

20 -

the human and financial costs of that delay

were enormous. We submit that without the

presence of a perceived legal duty to

correct prior discrimination and the

threat that a federal court might impose

tough remedial obligations as a result of

the City's failure to act, it would have

been virtually impossible for amicus to

take the necessary affirmative action steps

it took in 1 974 to correct prior racial

discrimination and its debilitating effects.

II. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER IS THE MOST

FLEXIBLE AND LEAST INTRUSIVE MEANS OFACHIEVING THE GOALS OF TITLE VII

As this Court has repeatedly noted, a

critical purpose of Title VII is "to

eliminate, so far as possible, the last

vestiges of an unfortunate and ignominious

page in this country's history," Albemarle

Paper Co . v . Mood y , 422 U.S. 405, 418

(1975) (citation omitted), and to "eliminate

21 -

the discriminatory effects of the past as

well as bar like discrimination in the

future," id. (quoting Louisiana v. United

States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965)).

The District Court's order represents

an attempt to salvage the limited progress

made toward achievement of these goals.

The public safety crisis caused by the

exclusion of minorities from the police and

fire departments is clearly a vestige of

the City's prior discriminatory conduct.

In view of the legislative history of the

1972 Act, discussed above, it is clear that

Title VII mandates that the District Court

eliminate this vestige. Similarly, the

District Court had to devise a means of

overcoming the reluctance of minorities to

apply for employment with these City

agencies in order to eliminate the dis

criminatory effects of the past and prevent

22

6 /future discrimination.—

Title VII gives district courts broad

powers to achieve these goals. Section

706(g) authorizes the courts to order "such

affirmative action as may be appropriate,"

as well as "any other equitable relief as

the court deems appropriate." Clearly,

these provisions are sufficient to encom

pass both the original hiring goals

incorporated into the consent decree

7 /and the layoff order now at issue.-

6/ See, e.g. , Carter v. Gallagher, 452

F.2d 315, 331 (8th Cir. 1971) (en banc)

cert. denied, 406 U.S 950 (1972).

1/ A court of equity may modify a decree of injunction even though it was entered

by consent, and whether or not the power

to modify was reserved by its terms.

United States v. Swift and Company, 286

U.S. 106 (1932). This expression of the

inherent authority of a court to enforce

its own decrees is frequently noted

throughout the case law, generally, in

civil rights cases, United States v. Hall,

472 F.2d 261 (5th Cir. 1972), and in cases

23

7/ continued

involving the enforcement of consent

decrees under Title VII, EEOC v. Longshore

(ILA), Locals 829 and 858, F. Supp.

____, 9 E.P.D. 1f 10,159 (D. Md. 1975). In

EEOC v. Plummer & Pipefitters Local 189,

438 F. 2d 408 , 414 ( 6th Cir. 1971), the

court asserted:

And beyond question, the district

court had authority either sua sponte

or on petition to reshape its injunction so as to achieve its original

and wholly appropriate purpose,

(citation omitted).

See also United States v. United Shoe

Machinery Corp., 391 U.S. 244, 251 (1968)

(district court had the power to modify its

decree entered ten years earlier, where the

decree had not achieved the adequate relief

to which the government was entitled).

While this exercise of a Court's

power to protect the efficacy of its

orders is commonly viewed as an expression

of the court's inherent authority, United

States v. Swift & Co., supra; United

States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp.,

supra, the All Writs Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1651,

offers another basis for this authority. Under the All Writs Act a federal court may

issue such commands as may be necessary or

appropriate to effectuate and prevent

frustration of orders it has previously

issued, even if they extend to persons "not

partners to the original action or engaged

24

In this case a municipal employer

entered into consent decrees following

specific judicial findings of past dis

crimination. In upholding the district

court's imposition of color-conscious

relief, the First Circuit held that the

remedy went "no further than to eliminate

the lingering effects of previous practices

that bore more heavily than was warranted

on minorities." Boston Chapter, NAACP,

Inc, v. Beecher, et al. , 504 F.2d 1017,

1027 (1st Cir. 1974), cert. denied, 421

U.S. 910 (1975).

In subsequent rulings, now before

this Court for review, the district court

7/ continued

in wrongdoing" United States v. New York

Telephone Co., 434 U.S. 159, 172 (1977).See also, Harris v. Nelson, 394 U.S. 266,

299 (1969); Adams v. United States ex rel

McCann, 317 U.S. 269, 273 (1942).

25

and the Court of Appeals imposed a modifi

cation of those decrees which would allow

the City of Boston to respond to its

unforeseen fiscal restraints, subject only

to a reasonable deference to its obligations

under the decrees. In so doing, the

district court, working within the context

of a judicially imposed consent decree and

a state statute governing the manner of

8 /layoffs for the affected agencies,-'

achieved a modification that offered the

defendants great flexibility in responding

to the City’s fiscal constraints. The

court's order allowed the City to seek

alternatives to layoffs, or, if layoffs

were unavoidable and the state civil

service statute proved in conflict with the

ongoing judicial remedy, the order relieved

the City from the operation of the statute

8/ Mass. Gen. Laws c. 31, § 39.

26

on a limited and temporary basis in order

to prevent nullification of prior court

orders.

The district court restrained the

defendant employer from implementing any

program of reductions which reduced the

level of minority firefighters or police

officers below the level that had been

obtained pursuant to the decree, i.e. , 14.7

percent of all firefighters and 11.7

percent of all police officers The

district court did not order layoffs nor

did it order any specific response to the

fiscal problems of Boston. The flexibility

and generality of the court's rented ial

order was effective. The State and City

subsequently developed a plan which both

alleviated the need for any layoffs and

10/ Castro, 522 F. Supp. at 877.

27

incorporated the pre-layoff staffing

patterns of the respective departments.

Moreover, the plan developed by the

City and State was only one of several

options available to the City under the

court's order. For example, the presumed

fiscal constraints of Proposition 2-1/2

could have been met via plans which in-

1 2/eluded work sharing,— pay reductions,

or early retirements, none of which would

1 2 / In recent years the concept of

voluntary work-saving has received widen

ing consideration as a fair and effective

alternative to layoffs. For example,

anticipating the layoff of thousands of

public employees because of the passage of

Proposition 13, California became the

first state to adopt a Work Sharing

Unemployment Insurance plan in 1978,

§ 1279.5 of the California Unemployment

Insurance Code. This plan allowed Cali

fornia employers to reduce the work week

instead of reducing the work force and

further allowed each employee to get a pro rata share of unemployment compensation.

Similar bills have been adopted in Oregon,

House Bill 3306, Feb. 22, 1982, and Arizona,

Senate Bill 1005 Jan. 1, 1982, and in 1982,

28 -

have reduced the percentages of minorities

obtained under the decrees or required any

conflict with the state civil service

statute.

Indeed it was only if the city

determined that layoffs were inevitable

and that such layoffs "would allow the

substantial eradication of all progress

made by blacks and hispanics in securing

public employment as members of either

the police or fire departments since

12/ continued

U.S. Representative Patricia Schroeder

introduced the Short-Time Compensation Act,

P.L. 92-248, Part of the Tax Equity Act of

1982, Section 194 which would achieve a

similar result. See, Morand and McPherson, Union Leader Responses To California's

Work Sharing Unemployment Insurance

Program, Bureau of National Affairs, Daily

Labor Report, Vol. 102, D. 1 (May 28,

1981). See also Leonard Greenhalgh, A

Cost_Benefit Balance Sheet for EvaluatingLayoffs As A Policy Strategy, October 1 ,

1978 (study conducted under the auspices

the State of New York and the Civil Service

Employees Association).

29

1 3 /1 9 7 0 " — / that any interference with

the operation of the statute would be

required.

The district court did not hold that

the civil service statute which established

a reverse seniority system for layoffs of

public employees was invalid. The court

simply held that the implementation of

the statute cannot eradicate the results

gained over the past eleven years from the

. . . 1 4 /judicially imposed remedy.— /

The district court specifically strove

13/ Castro, 522 F. Supp. at 877.

14/ Moreover, as noted by the court below,

"remedies to right the wrong of past

discrimination may suspend valid state

laws." Boston Chapter, NAACP v. Beecher,

679 F.2d at 975. See also, Louisiana v.

United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1964); Carter

v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d at 328. A " [s]tate

law prohibition against compliance with the

District Court's decree cannot survive the

command to the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution." Washington v.

Fishing Vessel Ass'n, 443 U.S. 658, 695

( 1979).

30

to limit the effect, if any, its order

would have on the state statute. The order

did not prohibit layoffs of members of

either department. It did not bar the

layoff of all minority officers. Moreover,

notwithstanding the fact that the hiring

goals of the original order had not

yet been obtained, the order did not

require any increase in minority represen

tation .

On the contrary, the court settled for

an order that merely prohibited the reduc

tion of minority personnel below the

levels which had been obtained pursuant to

the prior operation of its decree. Thus

the district court's order represents a

careful balancing of interests of the City,

the non-minority employees and the impor

tance of preserving progress toward the

goals of Title VII.

31

Consistent with the goal of maintain

ing the gains achieved by its remedial

order, the district court paid maximum

respect to the procedures and other pre

ferences established by the state statute.

Castro, 522 F. Supp. at 878, 879. The

district court's allowance of strict

statutory layoffs until the achieved

levels were threatened, its establishment

of separate lists and allowance of layoffs

pursuant to those lists in reverse order

and its provision for recall in reverse

order of layoff, all follow the require

ments of the statute.

III. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER IS CONSIS

TENT WITH SECTIONS 703(h) AND 706(g)

OF TITLE VII

A. Statutory Preferences Are Not

Protected by Section 703(h)

Section 703(h) of Title VII offers

limited exemption from some of the require-

32

ments of Title VII for bona fide seniority-

systems. Section 703(h) has no applicabil

ity to the statutory preference established

by Mass. Gen. Laws c.31, § 39. This is

simply not a case in which expectations

based upon collectively bargained seniority

rights must be harmonized with the remedial

requirements of Title VII. Franks v. Bow

man Transp. Co. , 424 U.S. 747 (1976);

International Bhd. of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977); and American

Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, ____ U.S. ____ 71

L.Ed.2d 748 (1982). Indeed the collective

bargaining agreements between the unions

and the Police and Fire Departments are

silent on the method of layoffs. Here, a

statutory provision, which incorporates a

1 5 /variety of preferences— and which is

subject to amendment or repeal by the

15/ For example, one reason for layoffs of

police officers hired as early as 1970,

33

Massachusetts legislature at any time,

cannot be viewed as creating a bona fide

seniority system.

The 1964 legislative history defines

bona fide seniority systems as being syn-

onomous with a collectively bargained

agreement. For example, the House Minority

Report on the Act— ^ explained its insist

ence on protection of seniority as follows:

Seniority is the base upon which

unionism is founded. Without its

system of seniority, a union would

lose one of its greatest values to

its members.

The provisions of this act grant the

power to destroy union seniority...

• • •

To disturb this traditional practice

is to destroy a vital part of unionism

... (emphasis in original)

15/ continued

was the absolute preference for veterans

in the statutory layoff scheme. Mass.

Gen. Laws, ch. 30 § 9A. See Brief For

The United States As Amicus Curiae, In Support of Petitioners, 8.

16/ See H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1963), reprinted in EEOC, Legisla-

34

This association of seniority and col

lective bargaining agreements was consist

ently expressed. For example, the Justice

Department statement concerning Title VII,

placed in the Congressional Record by

1 7/Senator Clark— ' speaks specifically of

seniority rights obtained pursuant to a

"collective bargaining contact," Teamsters,

supra, 431 U.S. at 351; a set of questions

and answers introduced by Senator Clark

references "last hired, first fired agree-

ments"--/ 110 Cong. Rec. 7217 (1964;

Franks, 424 U.S. at 760 n.16; Teamsters,

431 U.S. at 351 n.36.

The court also has consistently recog-

16/ continued

tive History of Title VII and XI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 2071 (hereinafter

1964 Legislative History).

V7/ 110 Cong. Rec. 7207 (1964).

18/ This language was also adopted by

Senator Dirkson. 110 Cong. Rec. 7212 (1964) .

35

nized that Section 703(h) protects the

variety of uses for seniority that are

included as part of the process of collec-

, , 1 9 /five bargaining.— ' For example, in Cali

fornia Brewers Association v. Bryant, 444

U.S. 598, 608 (1980), the Court specifically

refers to the ability of employers and

unions to develop such systems:

Significant freedom must be afforded

employers and unions to create differ

ing seniority systems.

Similarly, in American Tobacco Co., the

Court specifically noted the "policy favor

ing minimal governmental intervention in

collective bargaining," 71 L.Ed.2d at 760 n.

17, and several times underscored the

inextricable relationship between seniority

19/ Aaron, Reflections on the Legal Nature

and Enforcement of Seniority Rights, 75

Harv. L. Rev. 1532 (1962). See also

Aeronautical Lodge v. Campbell, 337 U.S.

521 (1949).

36 -

systems and collective bargaining:

Seniority provisions are of "over

riding importance" in collective

bargaining, Humphrey v. Moore, 375

U.S. 335, 346, 11 L.Ed.2d 370, 84 S.Ct.

363 (1964), and they "are universallyincluded in these contracts." Trans-

World Airlines v. Hardison, 2264. See

also Aaron, Reflections on the Legal Nature and Enforcement of Seniority

Rights, 75 Harv. L. Rev. 1532 (1962).

The collective bargaining process "lies at the core of our mature

labor policy..." Trans-World Airlines,

Inc. v. Hardison, supra, at 79, 53L.Ed. 2d 113, 97 S.Ct. 2264. See, e.g.,

29 U.S.C. § 151 [29 U.S.C. § 151].

Id. at 760.

It is clear that Congress intended

Section 703(h) as being protective of a

primary aim of collective bargaining, and

it is that adherence to collective bargain

ing and the notion of hard won seniority

rights obtained thereby, that informs

the Section 703(h) protections written

into Title VII in 1964.

Since 1971 all hiring in the Police

and Fire Departments has been subject to a

37

court ordered system that includes judicial

oversight of the hiring and employment

process because of judicially determined

racial discrimination. Hired under the

constraints of this judicial oversight,

these employees' expectations of job

security and other employment benefits are

necessarily colored by the court's ongoing

duty to eradicate the discriminatory evil

at which the decree was directed. Franks,

424 U.S. at 758, certainly holds that even

employee expectations based on collective

ly bargained seniority rights may be

modified to remedy unlawful discrimination.

Certainly in this case where there is no

collective bargaining agreement which

addresses seniority; where the applicable

provision is part of a statutory scheme

which has been judicially determined to be

discriminatory; and where all hiring for

38

the past eleven years and virtually all

those subject to layoff were hired pursu

ant to the court's supervision of its

remedial order, the court's power is no

less.

B. Section 703(h) Does Not Limit The

Scope of Remedial Orders

Even if the Court determines that the

statutory preference scheme constitutes

a seniority system within the meaning of

Section 703(h), petitioners are incorrect

in their suggestion that Teamsters and its

progeny preclude the remedial relief or

dered below. Such assertions misperceive

the essence of this case for several

reasons.

First, as the Court of Appeals

observed below:

None of the Supreme Court cases apply

to the basic issue at stake here; the

power of a court in a litigated

discrimination case to ensure that

relief already ordered not be evis-

39

cerated by senioriy based layoffs.

To hold a seniority system inviolate

in such circumstances would make a

mockery of the equitable relief

already granted.

Boston Chapter, NAACP, 679 F.2d at 974-75.

Second, Section 703(h), merely helps

define what is and what is not a violation

of the Act. Franks, 424 U.S. at 758.

Thus, in every case in which this Court

has ruled regarding a seniority system that

is claimed to be bona fide, it was address

ing the question of whether or not a

violation of the Act has been established.

See, Teamsters, 431 U.S. 324; California

Brewers Ass 'n, 444 U.S. 598 ; American

Tobacco Co., 71 L.Ed .2d at 760. Pullman

Standard v. Swint, U.S. , 102 S.

Ct. 1781 (1982). Here the issue is whether

or not a remedial order, which seeks to

preserve the integrity of a prior court

decree, may require departures from the

routine operation of an arguably bona fide

- 40

seniority system . Where the contours of

remedial orders are involved, this Court

has repeatedly approved alteration of

seniority rules. See Franks, and Zipes v.

Trans World Airlines, ____ U.S. ____, 71

L.Ed.2d 234, 247 (1982).

C. Title VII Authorizes Affirmative

Remedies

The amicus briefs for the United

States and the AFL-CIO argue that the

remedy under Title VII is limited to

providing make-whole relief. Thus, they

conclude that Title VII absolutely pro

scribes affirmative remedies that inciden

tally benefit individual members of the

disadvantaged class who have not proved

that they were directly victimized by the

employer's unlawful conduct.— /

20/ The United States does not explicitly

state to this Court that its reasoning

would result in absolute prohibition of

affirmative measures.

41

However, the Court repeatedly has

concluded that make whole relief is only

"one of the central purposes of Title VII."

Franks, 424 U.S. at 763 (emphasis added).— /

20/ continued

However, the United States has taken its

argument to this conclusion in other cases.

See Motion to Intervene As A Party Appellee

and Suggestion of Rehearing En Banc,

Williams v. The City of New Orleans, No.

82-3435 , 694 F.2d 987 (5th Cir. 1982).

This position is contrary to the prior con

sistent interpretation of Title VII by the

Attorney General, the Solicitor General, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion, the Department of Justice and other

agencies of the federal government. See,

e.g., Brief for Petitioners the United

States and the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, Steelworkers v. Weber N o .

76-432, at 26-35; 42 Op. Att'y Gen. No. 37

(Sept. 22, 1969); Uniform Guidelines onEmployee Selection Procedures , Appendix

(Policy Statement on Affirmative Action),

29 C.F.R. § 1607.

21 / In Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S.

193, 204 (1979), the Court concluded that

affirmative measures are "effective

steps to accomplish the goal that Congress

designed Title VII to achieve," and that such measures "hasten the elimination of

[the vestiges of past discrimination]."

42

The lower federal courts have concluded

that a proscription on judicially-imposed

affirmative remedies for proven Title VII

violations "would allow complete nullifica

tion of the stated purposes of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964." United States v .

Inti. Bro. of Elec. Wkrs, L. No. 38, 428

F.2d 144, 149-50 (6th Cir.), cert. denied,

400 U.S. 943 (1970). Indeed, every federal

circuit has concluded that use of affirma

tive remedies is not proscribed by Title

Yu. 22/

22/ See , e . g . , Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc. , 504 F. 2d at 1026-28; Ass'n Against

Discrimination v. City of Bridgeport, 647

F.2d 256, 279-84 (2d Cir.), cert. denied,

454 U.S. 897 (1981); Rios v . Enterprise

Assn., Steamfitters Loc. 638, 501 F.2d 622,

631 (2d Cir. 1974); E.E.O.C. v. American

Tel. & Tel. Co. , 556 F.2d 167, 1 74-77 (3rd

Cir. 1 977), cert, denied, 438 U.S. 915

( 1 9 7 8) ; United States v. Intern. Union of

Elevator Constrs., Local 38, 538 F.2d 1012

1017-20 (3d Cir. 1975); Chisholm v. United

States Postal Service, 665 F.2d 482, 498-99 (4th Cir. 1981); James v. Stockham Values &

43

22/ continued

Fittings Co., 559 F.2d 31 0, 356 ( 5th Cir.

1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1034 (1978);

Detroit Police Officers Assn., 608 F.2d at

696; EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co., 515 F.2d

301 (6th Cir. 1975); vacated on other

grounds, 431 U.S. 951 (1977); United States

v. City of Chicago, 549 F.2d 415, 436,

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 875 (1 977); United

States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d

354 (8th Cir. 1973); Davis v. County of Los

Angeles, 566 F.2d 1334, 1342-44 ( 9th Cir.

1977), vacated on other grounds, 440 U.S. 625 (1979); United States v. Lee Way Motor

Freight, Inc. , 625 F.2d 918 (10th Cir.

1979); Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257,

293-95 (D. C... Cir. 1 982). See also cases

listed at n.26, infra.

Although the new Eleventh Circuit has

not itself addressed this issue, the

decisions of the former Fifth Circuit are

controlling in the new Eleventh Circuit.

See Bonner v. City of Pritchard, 661 F.2d

1206, 1207 (11th Cir. 1981).

Several of the lower court deci

sions imposing affirmative remedies have

been cited with approval in opinions of

this Court. See , e_̂cj . , University of

California Regents v. Bakke , 4 3 8 U.S.

265, 353-54, n.28 (1978) (opinion of

Justices Brennan, White, Marshall and

Blackmun); Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448, 510-11 (1980) (opinion of Justice

Powell).

44

Amicus the AFL-CIO relies on one sen

tence of Title VII — • the last sentence

of Section 706(g) — to support its asser

tion that Title VII proscribes a remedy

which this Court has found to be "effec

tive," Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193,

204 (1979), and which the federal courts of

appeals unanimously have found to be

necessary. As discussed below, Section

706 (g), like Section 7 0 3 ( j ) of Title

2 3/VII,— / was intended to make clear that

the Act does not require any particular

racial composition of the workforce solely

for the purpose of racial balance, and does

not speak to the issue of affirmative

remedies for Title VII violations.

The last sentence of Section 706(g)

sets out a factual predicate for its

23/ 42 U.S.C.. § 2000e-2(j).

45

application: that "an individual ...

was refused employment or advancement or

was suspended or discharged for any reason

other than discrimination on account of

race, color, sex, or national origin or in

violation of section 704(a)." Affirmative

measures do not require the hiring or

promotion of an individual; rather they

direct the employer to select from among

qualified members of the class against whom

the employer has discriminated. Thus, as

the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

has found, the last sentence of Section

706(g) was designed to preserve the em

ployer's defense against a claim for indi

vidual relief. See EEOC v. American Tel. &

Tel. Co., 556 F.2d 167, 177 (1977), cert.

denied, 438 U.S. 915 (1978).

The 1964 legislative history of Title

VII provides no clear indication concerning

46

Congress' view on affirmative action. See,

e . g . , Brief for Petitioners the United

States and the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, Steelworkers v. Weber, No.

76-432, at 28-31. However, the 1964 leg

islative history supports amicus' conclu-

s ion that the last sentence of Section

706(g) is directed toward individual rem-

ed ies and that the 1964 Congress did not

address the issue of affirmative relief.— ^

24/ We have located only three explana

tions of the last sentence of Section

706(g). Congressman Celler explained that

the sentence was to preclude the finding of "any violation of the act which is based on

facts other ... than discrimination." 110

Cong. Rec. 2567 (1964) (emphasis added).

An interpretative memorandum intro

duced into the Congressional record by the

Senate floor leaders Senators Clark and

Williams also suggests that the sentence

addresses violations of the Act, and not

affirmative remedies. 110 Cong. Rec. 7214 (1964).

Finally Senator Humphrey explained

that the "hiring, firing, or promotion of

employees [will not be permitted] in order

to meet a racial 'quota' or to achieve a

certain racial balance." 110 cong. Rec.

6548. This statement also is consistent

with the view that Section 706 (g) bars

47

The brief for the AFL-CIO cites

several "anti-quota" statements made during

the 1964 debates. However, these state

ments were not specifically directed

at Section 706(g). As a result of concerns

about the imposition of quotas, Section

703(j) was added to the bill which became

Title VII. See Vaas, Title VII: Legisla

tive History, 7 B.C. Ind. & Comm. L. Rev.

431, 447-57 (1966). There is simply no

basis for believing that the statements

cited in the brief of the AFL-CIO refer to

Section 706(g), rather than the concern

addressed by Section 703(j).— ^

24/ continued

affirmative remedies imposed solely for the

purpose of achieving a specific racial

balance, but does not prohibit such remedies

where they are necessary to achieve the

valid remedial purposes of Title VII.

2_5/ Thus, since "Section 703(j) speaks to

substantive liability under Title VII and

does not concern whether race can be taken

into account for remedial purposes,"

48

Any doubts that Title VII authorized

affirmative remedies were put to rest with

enactment of the Equal Employment Opportun

ity Act of 1972, Pub. L. No. 92-261, which

comprehensively revised Title VII. The

intent of Congress when it passed the 1972

Act is particularly significant to this

case, because the Act extended Title VII

to state and local governments, including

the City of Boston. Moreover, Congress in

1972 carefully considered the court's

remedial powers and amended Section 706(g)

to expand the remedial authority of the

courts. Thus, with respect to the remedies

that can be imposed against local govern-

25/ continued

Weber, 443 U.S. at 204, n.5, the remarks

cited by the AFL-CIO have no relevance to

this case.

49

mental bodies, Congress' intent in 1972 is

of much greater relevance than the ambigu

ous 1964 legislative history.

By the time Congress enacted the 1972

Act, the case law firmly established that

affirmative remedies are necessary and

appropriate in some situations to correct

2 6/Title VII violations. These court deci —

26/ See, e^g^ United States v . United

Brotherhood of Carpenters & Joiners, Local

169, 457 F.2d 210 (7d Cir.), cert, denied,

409 U.S. 851 (1972); U n_i t e d_ S t a t e s_ v .

Ironworkers Local 86 , 443 F.2d 544 (9th

Cir.), cert. denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971);

United States v. International Bro. of

Elec. Wkrs. L. No. 38, 428 F.2d 144, 149-50

(6th Cir.), cert. denied, 400 U.S. 943

(1970); Local 53, Asbestos Workers v.

Volger , 407 F.2d 1047, 1055 (5th Cir.

1969).

The federal courts had also upheld the

affirmative measures required of federal

contractors under Executive Order 11246

against challenges that such measures were prohibited by Title VII. See , e^g^,

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsyl

vania v. Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159, 173 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854

(1971); Southern 111. Builders Ass'n v.

Ogilvie, 471 F.2d 680, 684-86 (7th Cir.

1972).

50 -

sions were well-known to Congress and

figured predominantly in the Committee

2 7/Reports and debates on the 1972 Act.— 7

The House Report explicitly stated:

"Affirmative action is relevant not only to

the enforcement of Executive Order 11246

but is equally essential for more effective

enforcement of Title VII in remedying

employment discrimination." H. R. Rep. NO.

92-238, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess. 16 (1971).

Moreover, amendments were introduced

in both the House and the Senate to re

strict federal agencies and courts from

ordering affirmative hiring remedies, and

all of these amendments were defeated. See

117 Cong. Rec. 32111 (1971); 118 Cong. Rec.

2 7/ Both the House and Senate reports

cited with approval several of the court

decisions upholding affirmative remedies.

See, e.g., S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92nd Cong.,

1st Sess. 5 n. 1 (1971); H.R. Rep. No.

92-238 , 92 Cong., 1st Sess. 8 n. 2, 13

(1971).

51

1676 (1972); _ic3. , at 4 918.-̂ -// in opposing

such amendments offered by Senator Ervin,

Senator Javits, the co-floor leader of the

bill, specifically defended the affirmative

measures ordered by several federal courts,

and had two of the courts' opinions

printed in their entirety in the Congres

sional Record. 118 Cong. Rec. 1664-1676

28_/ The Brief for the AFL-CIO, at 17-21

asserts that statements made in connection

with the rejection of the Dent Amendment

establish Congress' common understanding

that such an amendment was unnecessary

because Title VII already prohibited

quotas. There is no doubt that Congress

believed that quotas were prohibited;

in fact Section 7 0 3 ( j ) of Title VII

explicitly so provides. However, this

understanding provides no insight as to

whether Congress thought that court-imposed

affirmative remedies were proscribed quotas. For example, Representative Hawkins

(quoted at Brief for AFL-CIO, at 18)

explained that the Philadelphia Plan,

which provided numerical hiring guide

lines, did not constitute establishment of

quotas. 118 Cong. Rec. 8465. See, also

id. at 8520 (remarks of Representative Ford.)

52

(1 9 7 1) /

Third, Congress indicated its ap

proval of affirmative measures when it

added Sections 717 and 718 to Title

VII. Section 718 was proposed by Senator

Ervin for the purpose of correcting

inconsistency of administration of the

affirmative action program under Executive

Order 11246. See 118 Cong. Rec. 578-81

(1972) .— / Enactment of Section 718

29/ Congress' awareness of the decisions

that had ordered affirmative measures

in Title VII cases is particularly sig

nificant in view of the understanding

expressed in the section-by-section anal

ysis submitted with the conference report

to both Houses of Congress that in any area

not addressed by the 1 972 Act "the present

case law as developed by the courts would

continue to govern the applicability and

construction of Title VII." 118 Cong. Rec.

7166 (1972).

30/ Thus, contrary to the assertion in the

Brief for the AFL-CIO, at 24, Congress did

not reject all amendments offered by

Senator Ervin in order to end the filibus

ter.

53

demonstrates that Congress carefully-

considered the Executive Order program,

modified one aspect of that program and

deliberately left intact the substance of

the program, including its affirmative

action requirements. Congress' approval of

the affirmative measures used under the

Executive Order program necessarily in

cluded the Congressional decision that such

measures do not violate Title VII.

Section 717 extended Title VII to

federal government employees. Section 717

requires, among other things, that each

department and agency develop an affirma-

3 1 /tive action plan for employment.— /

31/ The Civil Service Commission "is to

review, modify and approve each department or agency developed [plan] with full

consideration of particular problems and

employment opportunity needs of individual minority group populations within each

geographic area." S. Rep. No. 92-415, supra, at 15.

54

The purpose of section 717 was to make the

Federal Government a "model employer."

118 Cong. Rec. 2298 (statement of Mr.

Williams). Thus requirement of affirmative

measures by the Federal Government is

inconsistent with the notion that Congress

intended to prohibit, or thought it had

already prohibited, court-imposed affirma

tive remedies for proven violations of

Title VII.

D. The District Court's Order Is

Consistent With Section 706(g)

The Brief for the United States,

at 22-24, asserts that the District

Court's order is contrary to Section

706(g). The position of the United States

is based on its view that "make whole"

relief for proven victims is the only

purpose of a Title VII remedy. Because the

United States' position would result in

prohibition of all affirmative remedies

55

under Title VII, the arg ument o f the

United States must be rej ected for the

reasons stated in Part C, above.

Moreover, it is clear that the

layoff order is consistent with Section

706(g). As discussed above, the order

served important Title VII goals and the

first sentence of Section 706(g) is broad

enough to encompass relief which is neces

sary to preserve the court's original

decree.

The last sentence of Section 706(g)

simply does not pertain to the Court's

layoff order. The order does not require

the City to hire, reinstate, etc., any

particular individual. Rather, the order

gives the City the option of engaging

in no layoffs, or utilizing any layoff

program that does not interfere with the

purposes of the original decree. Moreover,

because the order is designed to preserve a

56

decree aimed at achieving goals of Title

VII other than individual make-whole

relief, the order is not within the purpose

of the last sentence.

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER IS CONSIST

ENT WITH THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

It is beyond serious question that

imposition of affirmative measures in

appropriate situations to remedy Title VII

violations is consistent with the equal

protection guarantees of the Constitution.

See, e.g., University of California Regents

v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 363 (1978) (opinion

of Justices Brennan, White, Marshall and

Blackmun). Indeed, the standards developed

by the courts of appeals in the Title VII

area have been used for guidance in deter

mining the constitutionality of other types

of affirmative action. See, e.g., Fulli-

love v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448, 510-11

57

(1980) (opinion of Justice Powell); Bakke,

438 U.S. at 301 (opinion of Justice

Powell).

"Where federal antidiscrimination

laws have been violated, an equitable

remedy may in the appropriate case include

a racial or ethnic factor." Fullilove,

448 U.S. at 483 (opinion of Justice Bur

ger). While the Court has insisted that

such a remedy is appropriate only in cases

of "identified discrimination", id., at 498

(opinion of Justice Powell) the Court has

never suggested that the remedy is consti

tutionally limited to make-whole relief for

identified victims. Rather, the scope of

the constitutionally permitted relief is

defined by what is necessary to ”repai[r]

the effects of discrimination," id. at

510.— /

32/ For example, the Court repeatedly has

held that race-conscious numerical remedies

- 58

The District Court's order in this

case is a remedial measure that is consist

ent with the Fourteenth Amendment. The

District Court imposed its layoff order

only when it became apparent that the

remedy it had previously ordered would

otherwise be nullified. The same compel

ling necessity that mandated the initial

affirmative relief also mandated action to

preserve that remedy.

The court's layoff order satisfies all

of the requirements for constitutional

32/ continued

are necessary to remedy unconstitutional

school desegregation. See, e,g. , Swann v.

Chariotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971); McDaniel v. Barresi,

402 U.S. 39 (1971); North Carolina Board

of Education v. Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1971).

The race-conscious remedies in these cases

were not limited to "make-whole" relief

for children in the school system during

the years in which violations occurred.

Rather, race-conscious remedies affecting

future generations of schoolchildren were

found necessary to overcome the effects of

past discrimination and to assure future compliance with the law.

59

affirmative action. The order

only way possible to preserve the

remedy, see , e,g . , Fullilove, 448

480-89 (opinion of Justices

White and Powell); id., at 498-99

was the

original

U.S. at

Burger,

(opinion

of Justice Powell); Bakke, 438 U.S. at 315

(opinion of Justices Brennan, White,

Marshall and Blackmun), and it did not

stigmatize or single out any politi

cally weak non-minority group to bear the

brunt of the remedy. Id., at 361. 33/

While the burdens of discriminatory

conduct and its remedy may be harsher in a

recessionary, financially-depressed econ

omy, the constitutional issues and analysis

33/ Indeed, the strong political power of

the affected non-minority employees is

demonstrated by the fact that the state

legislature appropriated funds sufficient

to prevent any layoffs when the district

court determined that non-minority rather

than minority employees primarily would be

laid off.

60

must remain the same. Where such measures

are necessary to achieve the remedial

purposes of Title VII, the constitutional

requirements for their imposition are

satisfied.

CONCLUSION

We have focused on an aspect of the

issues in this case as they impact on

factors that affect the well being of our

Nation's cities. We believe that it is of

some significance that no City, not even

the City of Boston which is the immediate

city involved, has sought to support

the position espoused by petitioners. In

this case the discretion exercised by Chief

Judge Cafferty served as a spur to release

the creative energies that produced a

solution which served well the interests of

the citizens of the City of Boston. It

appears that, so long as the last-hired

61

first-fired system of layoffs was followed,

resulting in placement of the entire burden

on the shoulders of politically-weak

minorities, there was little incentive for

the diverse actors to devise alternatives

that would not undo the progress made

pursuant to the district court's earlier

orders. If this Court were to approve the

arguments being advanced by petitioners,

the ability of financially strapped cities

to find alternatives to destructive layoffs

would be undermined. The decision of

the United States Court of Appeals for the

First Circuit should be affirmed.

62

Respectfully submitted,

Donald Palen

C o rporation Counsel,

City of Detroit

Frank Jackson

Supervising Asst. Corp.

Counsel1010 City-County Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Attorneys, City of Detroit,

for A m i c u s C u r i a e

0. Peter Sherwood

Clyde E. Murphy

Penda D. Hair10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030New York, New York 10019

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

In Baker v. City of Detroit, 483 F.

Supp. 930, 996 (E.D. Mich. 1979) a

district court described fully the causes

and public safety consequences of the

Detroit Police Department's discriminatory

conduct as follows:

[T] he Police Department and the

black community were at each other's throats at least until the early

1970's. ... the Police Department was

regarded as an "occupation army" in

the black community and was treated as