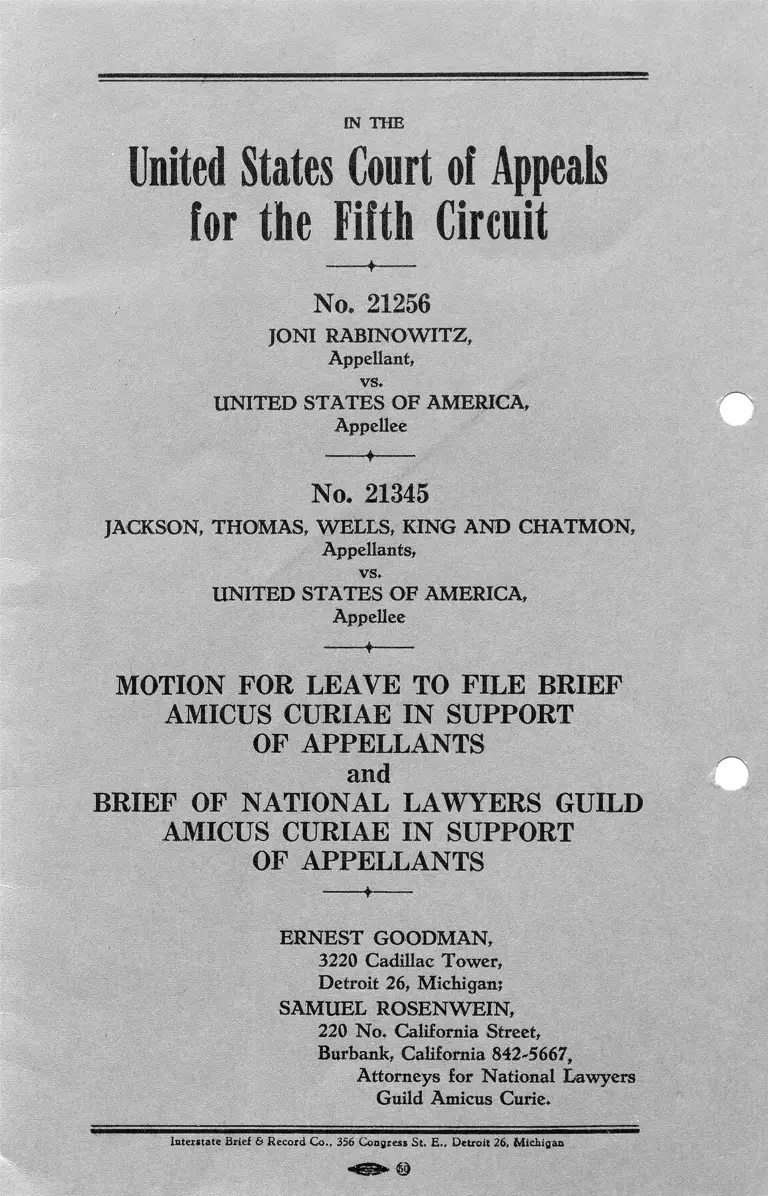

Rabinowitz v. United States Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rabinowitz v. United States Motion for Leave to File and Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Appellants, 1962. aa75c4b7-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e2c5a8ae-6a29-4775-8e11-0331d07d5059/rabinowitz-v-united-states-motion-for-leave-to-file-and-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

No. 21256

JONI RABINOWITZ,

Appellant,

vs.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

Appellee

No. 21345

JACKSON, THOMAS, WELLS, KING AND CHATMON,

Appellants,

vs.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT

OF APPELLANTS

and

BRIEF OF NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD

AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT

OF APPELLANTS

ERNEST GOODMAN,

3220 Cadillac Tower,

Detroit 26, Michigan?

SAMUEL ROSENWEIN,

220 No. California Street,

Burbank, California 842-5667,

Attorneys for National Lawyers

Guild Amicus Curie.

Interstate Brief 6 Record Co., 356 Congress St, E.. Detroit 26, Michigan

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae in

Support of Appellants........................................ 1

Brief of National Lawyers Guild Amicus Curiae in

Support of Appellants........................................ 3-13

Interest of the National Lawyers Guild... . 3-4

Statement ..................................................... 4

Argument ..................................................... 5-13

I. The historic role of the Grand Jury

is that of guardian against oppres

sive governmental action. ............... 5-8

II. The Grand Jury serves in its his

toric role because of its representa

tive character................................... 8-10

III. The Constitution and our historical

heritage are particularly under

mined by the practice of racial ex

clusion from Grand Juries............... 11-13

INDEX TO AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases

Beck v. Washington, 369 U.S. 541, 582-83, 82 S. Ct.

955 [dissenting opinion]...................................... 8

College’s Case (1681) 8 How. St. Tr. 550.................. 6

Earl of Shaftesbury’s Case (1681) 8 How. St. Tr. 759' 6

Hale v. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43, 59................................. 8

Smith v. 'Texas, 311 U.S. 128,130, 61 S. Ct. 164,165.. 10

Thiel v. Southern Pac. Co., 328 UJS. 217, 2!20‘, 66 S.

Ct. 984, 985.......................................................... 10

United States v. Wells, 163 F. 313, 324...................... 8

XI

Miscellaneous Page

Burnstein, Grand Jury Secrecy, 22 Law In Transi

tion 93 [1962]....... ,............................................. 9

Edwards, The Grand Jury 27 (1906)......................... 5

Edwards, The Grand Jury 1-44 ([1906].................... 6

Kennedy & Briggs, Grand Jury ‘System 10 [1955]... 6

Kuh, The Grand Jury “ Presentment” : Foul Blow or

Fair Play? 55 Colum. L. Rev. 1103, 1108 [1955] 6

Weinstein and Shaw, Grand Jury Reports—-A Safe

guard of Democracy, 1962 Wash. TJ.L.Q1 191

[1962] ....................*............................................ 10

Younger, The People’s Panel, 74-75........................... 9

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

— f—

No. 21256

JONI RABINOWITZ,

Appellant,

vs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee

-------- f _ — .

No. 21345

JACKSON, THOMAS, WELLS, KING AND CHATMQN,

Appellants,

vs.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee

----- ♦-----

MOTION FOE LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF

AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT

OF APPELLANTS

-----*---- -

The National Lawyers Guild moves for leave to file the

attached Brief Amicus Curiae. The interest of the Guild

in the ease is set forth in the brief.

ERNEST GOODMAN,

SAMUEL ROSENWEIN,

Attorneys for National Lawyers Guild.

3

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

— +— -

No,, 21256

JONI RABINQWITZ,

Appellant,

vs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee

-----+---- -

No. 21345

JACKSON, THOMAS, WELLS, KING AND CHATMON,

Appellants,

vs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee

— — 4 ---- -

BRIEF OF NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD

AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT

OF APPELLANTS

---- #----

INTEREST OF THE NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD

The National Lawyers Guild is a national bar associa

tion which, throughout its history, has supported the in

dependence of the institutions of bar, bench and jury as

bulwarks in the struggle to preserve the civil liberties of

all. It was the first national bar association to admit all

members of the bar without regard to color. It also ac-

4

lively engages in the legal arena for the elimination of dis

crimination and segregation in all forms.

The appellants were active participants in the struggle

to assist those citizens denied their constitutional rights

in the state of Georgia. They were indicted by a racially

constituted Federal Grand Jury.

The Guild believes that justice can never be secured until

racial considerations are eliminated as factors in the func

tioning of every aspect of the judicial process—including

the Grand Jury.

For these reasons it seems appropriate that the Guild

submit its views as amicus curiae in this case.

STATEMENT

This brief is limited to the grand jury issue. On this

question, amicus does not repeat the arguments briefed

by appellant or other amici. The emphasis of the discussion

which follows is on the historical development of the grand

jury in England and in the United States as an institu

tional device intended to assure the fair and impartial ad

ministration of criminal justice. That history, it is sub

mitted, casts significant light on the importance of main

taining exacting standards in the selection of members of

a grand jury to the end that the grand jury, as an instru

ment of public justice, shall be truly representative of the

community. On the record here, it does not appear that

the grand jury was legally selected, and such an invalidly

constituted jury, it is submitted, does not meet the con

stitutional and democratic standards which history de

mands.

5

ARGUMENT

L

THE HISTORIC ROLE OF THE GRAND JURY IS THAT

OF GUARDIAN AGAINST OPPRESSIVE

GOVERNMENTAL ACTION

The formative period in the history of the grand jury

saw that body develop into the accusatory arm of the

government. By the Fourteenth Century, the form of the

grand jury, and its function of handing down indictments

was much as it is today. [See, Edwards, The Gramd Jwy

27 (1906).] This function of the grand jury was soon ex

panded to include its more significant role—defender of

the people’s liberty.

The history was summarized by Mr. Justice Field, sitting

as Circuit Justice, as follows:

“The institution of the grand jury is of very an

cient origin in the history of England; it goes back

many centuries. For a long period its powers were

not clearly defined; and it would seem, from accounts

of commentators on the laws of that country, that

it was at first a body which not only accused, but

which also tried public offenders. However this

may have been in its origin, it was, at the time of

the settlement of this country, an informing and

accusing tribunal only * * *. And in the struggles

which at times arose in England between the powers

of the king and the rights of the subject, it often

stood as a barrier against persecution in his name;

until, at length, it came to be regarded as an in

stitution by which the subject was rendered secure

against oppression from unfounded prosecution of

the crown.”

(Charge to Grand Jury, 30 Fed. Cases 992, 993,

No. 18,255.)

6

The independence of the grand jury was established by

College’s Case, (1681) 8 How. St. Tr. 550, and the Earl of

Shaftesbury’s Case (1681) 8 How. St. Tr. 759. In each

case, the accused was charged with treason, but the grand

jury found a bill “ignoramus” (the jury knows nothing

of the charge). When the jurors in College’s case were

asked why they had refused to indict, the answer was that

they had acted “ ‘according to their consciences and that

they would stand by it.’ ” (Kuh, The Grand Jury “ Present

ment” : Foul Blow or Fair Play? 55 Colum. L. Key. 1108,

1108 [1955].)

The true significance of these early cases can best be

understood when it is realized that the grand jurors’ politi

cal sympathies were with the accused, not with the king.

In this sentiment they had the agreement of many people.

(For an extensive discussion of the early history of the

grand jury, see, Edwards, The Grand Jury 1-44 [1906].

See also, Kennedy & Briggs, Grand Jury System 10 [1955];

Kuh, op. cit., supra, 1108.) The action of the jury had a

dual character: it was a demonstration of independence

from the government and a reflection of popular support

for the accused. The king’s solution to the action of the

juries was the obvious: pick a new jury and get the desired

indictment. This was done in the case of Stephen College,

who was eventually executed. (Kuh, op. cit., supra, 1108;

Edwards, op. cit., supra, 30.) But the grand jury had,

by then, taken its place as protector of the people.

In Colonial America the grand jury was noted as an

instrument of the people. The most celebrated example of

the democratic role of the early American grand jury is

in the case of John Peter Zenger. Zemger, editor and pub

lisher of the Weekly Journal, a New York paper, used his

paper to express anti-royalist sentiment. In 1735 a grand

7

jury twice refused to indict him for libel. (Edwards,

op. tit., supra, 32.) Again, the grand jury acted as an in

strument of the people; as a barrier against oppression.

Its primary concern at the time of the Zenger trial was

to insure liberty and freedom of the press for the people.

By the end of the Colonial period in American history,

the grand jury had established itself as an indispensable

arm of democratic government. Juries “ enforced or re

fused to enforce laws as they sawT fit and stood guard

against indiscriminate prosecution by royal officials.”

(Younger, op. \dt., supra, 26.) The colonists were so firmly

convinced that the grand jury was “a necessary and funda

mental safeguard of individual rights against governmental

oppression” (17 U. Miami L. Rev. 110 [1962]) that they

overtly manifested such belief in the Fifth and Sixth

Amendments of the United States Constitution.

The importance of the grand jury as an instrument of

democracy did not end with the revolution. Grand juries

supervised law enforcement activities of sheriffs and eon-

stables, and watched the activities of public officials. “At

the time of the Alien and Sedition trials Judge Harry Innes

advised a Frankfort, Kentucky, grand jury that its proper

place was ‘as a strong barrier between the supreme power

of the government and the citizens,’ rather than an instru

ment of the state * * * Innes told the grand jurors that

their duty was to shield the innocent from ‘unjust persecu

tions.’ ” (Younger, op. cit., supra, 54-55.)

From the early post-Revolutionary days to the present,

grand juries have been thought of as a means of protect

ing citizens from injustice. Again, in the words of Justice

Field:

“ In this country, from the popular character of

our institutions, there has seldom been any contest

8

between the government and the citizen, which re

quired the existence of the grand jury as a pro

tection against oppressive action of the government.

Yet the institution was adopted in this country from

considerations similar to those which gave it its

chief value in England, and is designed as a means,

not only of bringing to trial persons accused of

public offenses upon just grounds, but also as a

means of protecting the citizen against unfounded

accusation, whether it come from government or be

prompted by partisan passion or private enmity # # #

“ [TJhere is a double duty cast upon the jurors of

this district; one a duty to the government, or more

properly speaking, to society, to see that parties

against whom there is a just ground to charge the

commission of a crime, shall be held to answer the

charge; and on the other hand, a duty to the citizen

to see that he is not subjected to prosecution upon

accusations having no better foundation than public

clamor or private malice.”

(30 Fed. Cases, supra, at 993;

See also :

Beck v. Washington, 369 U.S. 541, 582-83, 82 S.

Ct. 955 [dissenting opinion];

Hale v. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43, 59.)

II.

THE GRAND JURY SERVES IN ITS HISTORIC ROLE BECAUSE

OF ITS REPRESENTATIVE CHARACTER

Two significant characteristics of the grand jury have

made it possible for that institution to function “ as a safe

guard against arbitrary or oppressive action.” (United

States v. Wells, 163 F. 313, 324.) Secrecy is the first of

9

these. Briefly, it was necessary for jurymen to deliberate

in secret in order to protect themselves from royal dis

pleasure. It still remains an important safeguard against

harassment of grand jurors. (See, generally, Burnstein,

Grand Jwny Secrecy., 22 Law In Transition 93 [1962].)

The other feature of importance is the grand jury’s repre

sentative character. The earliest American grand juries

were elected, usually by the town meeting. They reflected

the revolutionary tenor of the colonists, and were in the

lead in opposing the imperial government. (Younger, op.

cit., s%pra, 27.)

The broad, popular character of the grand jury of the

frontier is described by Younger (The People's Panel 74-

75) as follows:

“ Jurymen were indistinguishable from other per

sons gathered at the county seat to trade and enjoy

themselves. The only thing that set them apart

from their neighbors was the summons they had

received from the sheriff, telling them to appear for

grand jury duty at the approaching session of the

court. In most western territories and states the

clerk of the court chose the grand jurors by lot from

the list of eligible persons * # * All qualified electors

were eligible for jury duty in most western areas.

In only a few states was land ownership a prerequi

site. However, as in the Colonial period, the re

quirements were not high. Preemption claimants

and those who had made their first payment on gov

ernment land were regarded as landowners.”

The relationship of the composition of the grand jury

to its function was recognized by Chief Justice Shaw, Su

preme Judicial Court of Massachusetts.

“ Coming from the various parts of the country,

first designated by their townsmen, as persons well

fitted by their capacity, integrity, and personal

10

worth of character, to discharge the important func

tions of jurors, and then for each particular service,

designated by lot, without regard to sect or party,

rank or condition, the Grand Jury may justly be

regarded as a fair representation of the county,

participating in all the interests and feelings of the

people, and well acquainted with their condition and

circumstances. They bring with them all the local

knowledge and information, which are requisite to

enable them to perform their important duties with

efficiency, impartiality, and success.”

(Charge to Grand Jury, 8 Am. Jurist 216.)

The modern grand jury is thought to be as much a

representative of the people as it was in the past.

“A grand jury is a short-lived, representative,

non-political body of citizens functioning without

hope of personal aggrandizement. It comes from

the citizens at large and soon disappears into its

anonymity * * *”

(Weinstein and Shaw, Grand Jury Reports—A

Safeguard of Democracy, 1962 Wash. U.L.Q.

191 [1962].)

The historical position of the jury, in this case the grand

jury, has been recognized by the Supreme Court. Thus,

it has been said: “ It is a part of the established tradition

in the use of juries as instruments of public justice that

the jury be a body truly representative of the community.”

Smith v. Terns, 311 IJ.S. 128, 130, 61 S, Ct. 164, 165. To

the same effect is Thiel v. Southern, Pac. Go., 328 IJ.S. 217,

220, 66 S. Ct. 984, 985.

Unless a grand jury has been selected in a manner which

permits it to carry out its historic function—-people’s rep

resentative and guardian against oppression—it is respect

fully submitted it has been improperly selected.

11

III.

THE CONSTITUTION AND OUR HISTORICAL HERITAGE ARE

PARTICULARLY UNDERMINED BY THE PRACTICE OF

RACIAL EXCLUSION FROM GRAND JURIES

A n official policy which, denies participation in the in

strumentalities of justice to one class of citizens because

of race is, of course, a denial of the equal protection of the

laws, and a subversion of the true administration of crimi

nal justice. Such policy, moreover, strikes at the very heart

of a grand jury system where fair representation of a

cross-section of the community is integral to the historic

function of the grand jury.

In the Southern States, the disparity between the quali

fied Negro population and those Negroes who appear on

grand and petit jury lists is so great as to make it plain

that the requisite representative character of such juries

is non-existent. In 1960, the twelve iSouthern States ( Ala

bama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi,

North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee,

Texas and Virginia) had a total population of 45,781,599

persons. Bureau of the Census, World Almanac (1962)

255. Of this population, 10,180,688, or some 22%, were

non-white, predominantly Negroes. Bureau of the Census,

World Almanac (1962 ) 257. In the same year, these South

ern States had a population of voting age (generally 21

years, except Florida where the voting age is 18) totaling

26,528,885. Statistical Abstract of the United States (1962)

374. At the same time, there were 5,131,042 non-whites, or

20%, of similar voting age in such Southern States. The

Black Belt, which extends from Tidewater, Virginia down

12

the Coast of the Carolinas, and westward across Central

Georgia and Alabama to the Mississippi Delta; up through

Mississippi and Louisiana into Tennessee and Arkansas,

touching Florida and 'Texas (1981 Report of United States

Commission on Civil Rights, vol. 1, p. 143) has an even

greater percentage of qualified Negro inhabitants. Swpra,

331-341.

There is every indication that a substantial number of

Negroes in the Southern States are eligible for service

on grand and petit juries, but repeated investigations have

demonstrated that in many sections of the South “ the

only service rendered by Negroes in the courts of justice

is janitorial”. 1961 Report of the United States Commis

sion on Civil Rights, vol. 1, p. 179. There are counties in

the Southern States in which Negroes constitute the ma

jority of the residents but take no part in government

either as voters or jurors, swpra, p. 179. It is common

knowledge that Negro citizens are qualified educationally

and by other legal standards but are excluded from serv

ing as jurors solely because of their race or color. The

inference is plain from long-continued exclusion of Negroes

from any jury service in the Southern States that whole

sale discrimination exists in law and in fact. “ The serious

and continuing nature of the problem is revealed by the

frequency of cases in which the issue of jury exclusion

is raised and by local situations which the facts in those

cases disclosed; by the plain statements of judges and of

ficial observers; and by various field studies conducted by

the Commission’s staff.” 1961 Report of the United States

Commission on Civil Rights, vol. 5, p. 90.

13

It is plain, in the light of the aforesaid, that the grand

jury system which functions in the Southern States is in

large measure alien to onr historic traditions and to

American concepts of even-handed justice.

Respectfully submitted,

ERNEST GOODMAN,

3220 Cadillac Tower,

Detroit 26, Michigan.

SAMUEL ROSENWEIN,

220 No. California St.,

Burbank, California 842-5667,

Attorneys for National Lawyers

Guild Amicus Curiae.