Zwickler v. Koota Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Zwickler v. Koota Brief Amicus Curiae, 1967. e50a19ce-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e2cb6cd7-943c-4d3d-9358-4100b9e4cd9a/zwickler-v-koota-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

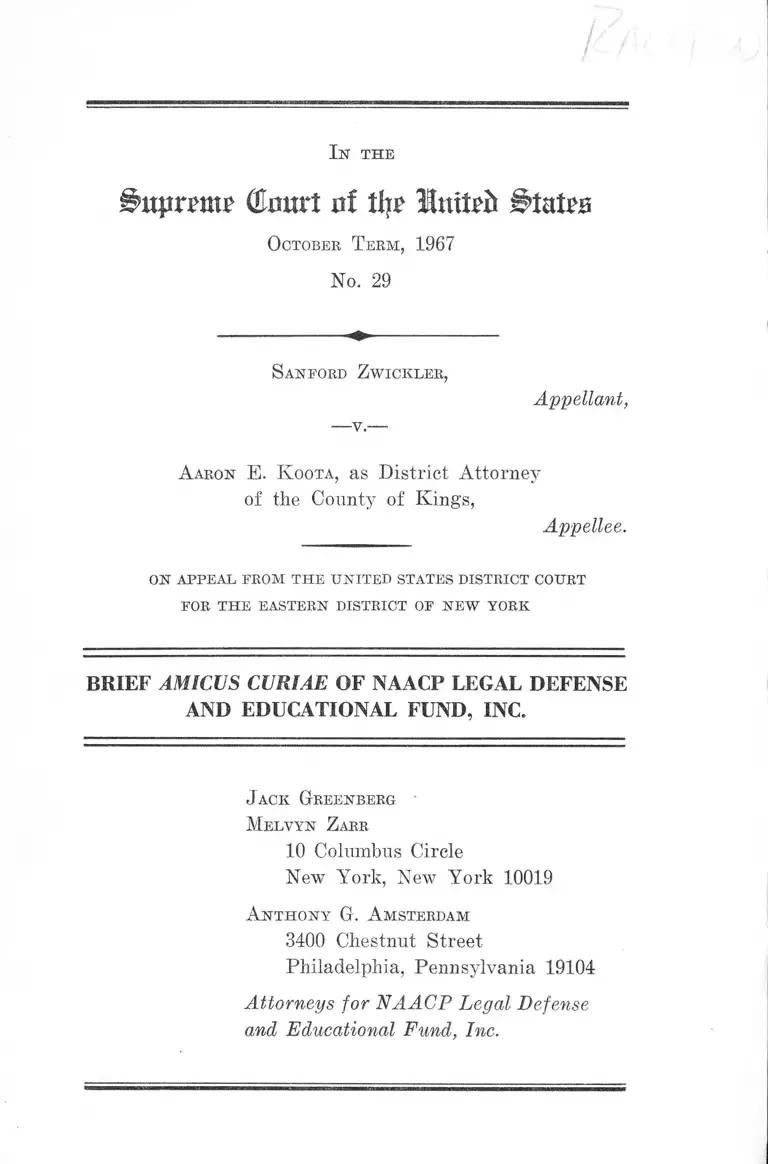

I n th e

m p x m x (Emtrt of tl ̂ little B M xb

October T erm, 1967

No. 29

Sanford Zwickler,

Appellant,

A aron E. K oota, as District Attorney

of the County of Kings,

Appellee.

on appeal from the united states district court

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

J ack Greenberg '

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

NewT York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

I N D E X

PAGE

Interest of Amiens .............................................................. 1

Argument ............... ............................. ......................... ....... 2

I. The State Statute Challenged by This Suit Is

Vague, Overbroad and Susceptible of Sweeping

and Imroper Application Trenching Upon Eights

of Free Expression ........................................... 3

II. The Court Below Erred in Abstaining.............. 5

Conclusion................................................................................. 9

Table op Cases

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 (1964), reversing

206 F. Supp. 700 (E. D. La. 1962) ........................... 5, 7

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360 (1964) ........................... 6, 8

Bond v. Floyd, 385 U. S. 116 (1966) ............................. 7

Cameron v. Johnson, 262 F. Supp. 873 (S. D. Miss.

1966), on remand from 381 U. S. 741 (1965), appeal

pending, 0. T. 1967, No. I l l Misc................ .............. . 6

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965) ................... 5, 7

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202 (1958) ...... ........... ........ 6, 7

Gayle v. Browder, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956),

affirmed per curiam 352 U. S. 903 (1956) ............... 5,6,7

11

PAGE

Jacobs v. New Y ork ,------ U. S . ------- , 18 L. ed. 2d 1294

(1967)...................................................................................... 8

Mills v. Alabama, 384 U. S. 214 (1966) .......................3, 4, 8

Strother v. Thompson, 372 F. 2d 654 (5th Cir. 1967) .... 2

Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 60 (1960) ...................... 3,4

Tannenbaum v. New Y ork,------ U. S .------- , 18 L. ed. 2d

1300 (1967) ...................................................................... 8

Thomas v. Mississippi, 380 U. S. 524 (1965) ................... 2

Zwicker v. B o ll,------ F. Supp.--------, W. D. Wise., No.

67-C-36, decided June 7, 1967, appeal pending, O. T.

1967, No. ------ Misc......................................................... 6

Statutes

28 U. S. C. §2283 ................................................................ 6

New York Penal Law, §781-b (McKinney’s Consol.

Laws, c. 40) .......................................................... 2, 3,4, 6, 8

I n th e

Court of % Itutrft States

October T erm, 1967

No. 29

Sanford Zwickler,

—v.—

Appellant,

A aron E. K oota, as District Attorney

of the County of Kings,

Appellee.

on a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

Interest of Amicus

Amicus is a New York corporation organized for the

purpose, among other things, of securing equality before

the law, without regard to race, for all citizens. In this

connection, amicus’ staff attorneys often have represented

citizens before various courts, including this Court, on

claims that they have been denied equal protection of the

laws, due process of law, and other rights secured by the

Constitution and laws of the United States. Moreover,

2

its attorneys have represented citizens who have been de

nied First Amendment rights while attempting to secure

equal treatment before the law without regard to race.

In Strother v. Thompson, 372 F. 2d 654 (5th Cir.

1967), amicus’ attorneys represented civil rights workers

prosecuted under a Jackson, Mississippi municipal ordi

nance restricting the distribution of handbills in that city.

Having had experience with the pains, perils and pro

longations of litigation in the state courts—litigation which

in the Jackson Freedom Rider cases alone required delay

of four years and expenditure of many thousands of dol

lars before the vindication of precious constitutional rights

in this Court, Thomas v. Mississippi, 380 IT. S. 524 (1965)—

amicus’ attorneys sought and obtained pretrial federal de

claratory and injunctive relief against the handbill prose

cutions.

Because of the broad significance of this case, which may

not adequately appear in argument on behalf of the parties,

amicus respectfully submits that its views may be of

interest to the Court.

Argument

Amicus submits that the state statute challenged by this

suit1 is on its face offensive to the First and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States and

that the court below erred in refusing to so hold.

1 Section 781-b of the New York Penal Law, McKinney’s Consol.

Laws, c. 40.

3

I.

The State Statute Challenged by This Suit Is Vague,

Overbroad and Susceptible of Sweeping and Improper

Application Trenching Upon Rights of Free Expression.

Appellant unsuccessfully sought below injunctive and

declaratory relief against Section 781-b of the New York

Penal Law. That statute makes it a crime, among other

things, to distribute “ in quantity” any anonymous literature

concerning any person “ in connection with” any election.

The court below, one judge dissenting, took no position

on the validity of the statute. However, it is plain that

!§781-b cannot stand consistently with Talley v. California,

362 U. S. 60 (1960), and Mills v. Alabama, 384 U. S. 214

(1966).

In Talley, the Court invalidated a municipal ordinance

making it a crime to distribute anonymous handbills “ under

,any circumstances.” The Court reserved the question

whether a more limited ordinance— “ limited [so as] to

prevent [fraud, false advertising, libel] or any other sup

posed evils” (362 U. S. at 64)—could pass constitutional

muster.

The New York statute purports to be more limited than

the Talley ordinance in two ways. It proscribes distribu

tion of anonymous literature only if the literature is: (1)

“ in quantity” ; and (2) “ in connection with” any election.

These “ limitations” only serve to incorporate impermis

sible vagueness into the statute and do not cure its over

breadth. As the court below noted (261 F. Supp. at 988),

the phrase “ in quantity” is not defined. Nor, amicus adds,

is there a definition of the phrase “ in connection with”

4

any election. The public is required to play “ guessing

games” (see 261 F. Supp. at 988) as to how proximate in

time and content to an election a handbill must be to meet

the statutory standard.

But even if §781-b were more limited than the Talley

ordinance, it would still not be limited enough to meet First

Amendment objections.

In Mills v. Alabama, 384 U. S. 214 (1966), this Court in

validated a state statute which made it a crime to solicit any

votes on election day in support of or in opposition to any

proposition being voted on that day. The state sought to

justify the statute on the ground that its limitation as to

time (only one day) and content (only “ electioneering” )

made it reasonable. But the Court rejected this defense,

holding (384 U. S. at 220):

We hold that no test of reasonableness can save a

state law from invalidation as a violation of the First

Amendment when that law makes it a crime for a news

paper editor to do no more than urge people to vote

one way or another in a publicly held election.2

Amicus submits that §781-b cannot escape invalidation

under the First Amendment when it makes it a crime for

a person to do no more than distribute “ in quantity” anony

mous handbills “ in connection with” a publicly held election.

2 The fact that Mills involved newspaper publishing rather than

handbill distribution has no constitutional significance (384 U. S.

at 219) :

The Constitution specifically selected the press, which includes

not only newspapers, books, and magazines, but also humble

leaflets and circulars, see Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444, 82

L. ed. 949, 58 S. Ct. 666, to play an important role in the dis

cussion of public affairs.

5

The Court Below Erred in Abstaining.

The court below, by abstaining, put itself in conflict with

several prior decisions of this Court. The court held that

appellant should first seek declaratory relief in an appro

priate state court (261 F. Supp. at 993). However, in An

derson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 (1964), reversing 206 F.

Supp. 700 (E. D. La. 1962) (three-judge court), also a fed

eral suit seeking to restrain the enforcement of a state

statute regulating the electoral process, this Court author

ized federal injunctive relief. No suggestion was made

either in this Court or below that such relief should first

have been sought in the appropriate state court, although

Louisiana,3 like New York,4 has a declaratory judgment

procedure. Such a suggestion was, however, made in Gayle

v. Browder, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956) (three-

judge court), affirmed per curiam, 352 U. S. 903 (1956), and

firmly rejected (142 F. Supp. at 713):

The short answer is that [comity] has no application

where the plaintiffs complain that they are being de

prived of constitutional civil rights, for the protection

of which the Federal courts have a responsibility as

heavy as that which rests on the State courts.

And in DombrowsTci v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479, 491 (1965),

this Court unambiguously held that when a statute broadly

overreaching First Amendment freedoms is challenged in

a federal court, the state must “ assume the burden of ob

taining a permissible narrow construction in a noncriminal

proceeding.”

8 See Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479, 491, footnote 6 (1965).

1 See 261 F. Supp. at 993.

II.

6

The court below also appeared to suggest that appellant’s

federal suit was premature, since appellant was not threat

ened with imminent arrest (see 261 F. Supp. at 988).5 But,

as this Court has pointed out, one is not required to risk

arrest in order to test the validity of a state statute in

fringing upon his federal rights, Evers v. Dwyer, 358 IT. S.

202, 204 (1958) ; Gayle v. Browder, supra. Moreover, this

suggestion ignored the practical restraints imposed upon

appellant by the statute. Appellant had to guess whether

he was within the time perimeter described by “ in connec

tion with any election.” If he guessed “ yes” , and the state

court disagreed, then it could dismiss his declaratory judg

ment suit by parity of reasoning with the court below.6 If

he wrongly guessed “ no” , distributed his handbills and was

arrested and charged under §781-b, then a federal court

might well hold relief barred by comity or 28 U. S. C. §2283.

See Cameron v. Johnson, 262 F. Supp. 873 (S. D. Miss.

1966) (three-judge court), on remand from 381 U. S. 741

(1965), appeal pending, 0. T. 1967, No. I l l Misc.; Zwicher

v. Boll, ------ F. Supp. - — , W. D. Wise., No. 67-C-36,

decided June 7, 1967 (three-judge court), appeal pending,

0. T. 1967, No. ------ Misc. In either event, he would he

required to wait until shortly before the election to com

5 Notwithstanding appellant had previously been arrested and

prosecuted under §781-b, the majority thought that appellant’s al

legation of future arrest and prosecution for the same acts “pre

sume [d] to read [the prosecutor’s] mind” (261 F. Supp. at 988).

6 Moreover, here, as in Baggett v. Bullitt, 311 U. S. 360, 378

(1964), “it is difficult to see how an abstract construction of the

challenged terms . . . in a declaratory judgment action could elim

inate the vagueness from these terms. It is fictional to believe that

anything less than extensive adjudications, under the impact of a

variety of factual situations, would bring the oath within the

bounds of permissible constitutional certainty. Abstention does not

require this.”

7

mence his suit—with the likelihood that the election would

come and go before he could obtain a protective judicial

ruling vindicating his plain First Amendment rights.

It is true that Anderson v. Martin, Gayle v. Browder and

Evers v. Dwyer were all equal protection cases rather than

First Amendment cases. But that fact cannot diminish the

propriety or necessity of federal relief. As this Court stated

in Bond v. Floyd, 385 U. S. 116, 131 (1966):

We are not persuaded by the state’s attempt to dis

tinguish, for purposes of our jurisdiction, between

[legislative action] alleged to be on racial grounds and

[legislative action] alleged to violate the First Amend

ment.

The fact that this suit seeks the vindication of First

Amendment rights should, if anything, make this a more

compelling case for federal relief. As this Court held in

Dombrowski v. Pfister, supra, 380 II. S. at 486-87:

A criminal prosecution under a statute regulating ex

pression usually involves imponderables and contin

gencies that themselves may inhibit the full exercise

of First Amendment freedoms . . . When the statutes

also have an overbroad sweep, as is here alleged, the

hazard of loss or substantial impairment of those

precious rights may be critical. For in such cases, the

statutes lend themselves too readily to denial of those

rights. The assumption that defense of a criminal

prosecution will generally assure ample vindication of

constitutional rights is unfounded in such cases . . .

The chilling effect upon the exercise of First Amend

ment rights may derive from the fact of the prosecu

8

tion, unaffected by the prospects of its success or fail

ure. (Emphasis added)

Notwithstanding this Court’s clear holding, and appel

lant’s express reliance upon it (261 F. Supp. at 988), the

court below brushed it aside, saying (261 F. Supp. at 992):

“ There is no suggestion . . . that the [appellant’s] defense

to any such prosecution [under §781-b] will not assure him

adequate vindication of his alleged constitutional rights.”

Unless this Court reasserts the primacy of its doctrine

over that of the district court, First Amendment rights will

entail only the right to have one’s arrest and conviction for

constitutionally protected activity overturned some years

later7—not the right to engage in the protected activity

itself. First Amendment rights should be the province not

only of law professors but of those persons whose criti

cisms and clamor “ the Framers of our Constitution thought

fully and deliberately selected to improve our society and

keep it free”, Mills v. Alabama, supra, 384 U. S. at 219. As

long as §781-b deters this socially vital and constitutionally

protected activity, abstention defeats rather than serves a

healthy federalism.8

7 And sometimes not even then, see Jacobs v. New Y o rk ,------

U. S. ------ ■, 18 L. ed. 2d 1294 (1987) ; Tannenbaum v. New York,

---- - U. S .------ , 18 L. ed. 2d 1300 (1967).

8 See Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U. S. 360, 378-79 (1964) :

We also cannot ignore that abstention operates to require

piecemeal adjudication in many courts, England v. Louisiana■

State Board of Medical Examiners, 375 U. S. 411, thereby de

laying ultimate adjudication on the merits for an undue length

of time, a result quite costly where the vagueness of a statute

may inhibit the exercise of First Amendment freedoms. . . .

Remitting these litigants to the state courts . . . would further

protract these proceedings, . . . with only the likelihood that

the case, perhaps years later, will return to the . . . District

Court and perhaps this Court for a decision on the identical

issue herein decided.

9

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the decision below should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

SB MORTON STRICT

NEW YORK M.N.*

38