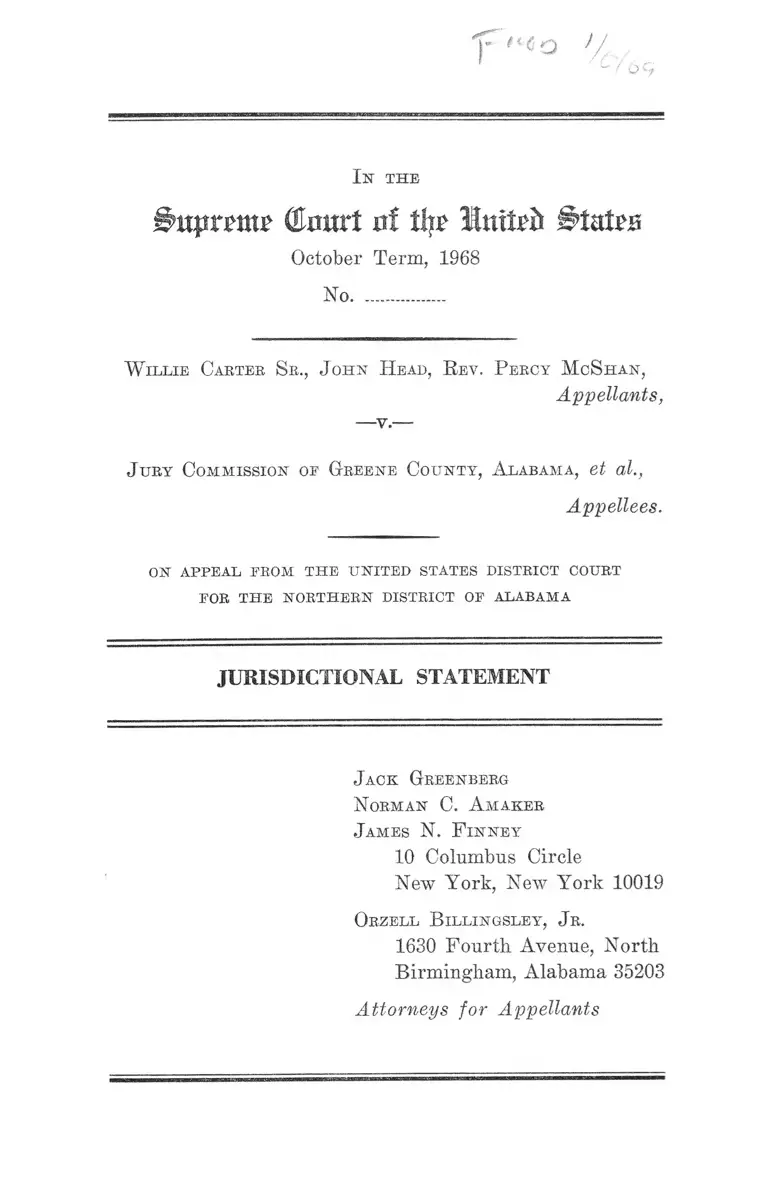

Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, Alabama Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

January 6, 1969

57 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carter v. Jury Commission of Greene County, Alabama Jurisdictional Statement, 1969. 7ecdd906-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e2ea85a1-a386-4091-9d32-fe00b06fefbe/carter-v-jury-commission-of-greene-county-alabama-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

-/69

I n t h e

(Emtrt ni tin Btutvs

October Term, 1968

No..................

W illie Carter Sr., J ohn Head, R ev. P ercy McShan,

Appellants,

---y.---

J ury Commission oe Greene County, A labama, et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E N O R T H E R N D ISTRICT OF ALAB A M A

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Jack Greenberg

Norman C. A maker

James N. F inney

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Orzell B illingsley, J r.

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Opinion B elow ......................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ........ ........ ................................ -.............. -..... - 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved....... 3

Questions Presented.............................-........... ....... — .... 4

Statement ......... .......... -...... - ....................... .............. -....... 5

A. Introduction.............................................. 5

B. Selection Process of Jury Commissioners and

Jurors .................................................................... - 7

T he Questions Presented A re Substantial.................. 9

I. Code of Alabama, Title 30, §21 Is Unconstitu

tionally Vague Because It Permits the Arbitrary

Exclusion of Negroes From Service as Jurors

in Violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States................... 10

II. The Jury Commission of Greene County Is Un

constitutionally Constituted Because It Per

petuates Racially Discriminatory Juror Selec

tion in Violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States............. 16

Conclusion......... .................... -..................................... ........... 18

A ppendix :

Opinion and O rder...................................................... la

Final Judgment .........................-................................ 25a

Statutory Provisions Involved (Text) .................... 29a

PAGE

11

Table of A uthorities

Cases: page

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360 (1964) ....................... 11

Banks, et al. v. Holley, C.A. 735-E (MJD. Ala. 1967) 14

Bokulich, et al. v. Jury Comm, of Greene Co., No.

1255 Misc., O.T. 1968 .............................................. 2n, 6

Board of Supervisors v. Ludley, 252 F.2d 372 (5tlx

Cir. 1958), cert, denied, 358 U.S. 819 (1958) ........... 11

Bostick v. South Carolina, 386 U.S. 479 (1967) ....... 11

Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. en banc, 1966)

16,17

Bush, et al. v. Woolf, C.A. 68-206 (N.D. Ala. 1968) .... 14

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129 (1964) ................... 5

Coleman v. Alabama, 389 U.S. 22 (1967) ...................5 ,12n

Coleman v. Barton, C.A. 63-4 (N.D. Ala. June 10,

1964) ............................................................................ 12,13

Dennard, et al. v. Baker, C.A. 2654-N (M.D. Ala.

1968) ................................................... 14

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872 (S.D. Ala.), a ffd

336 U.S. 933 (1949) .................................................... 11

Good, et al. v. Slaughter, C.A. 2677-N (M.D. Ala.

1968) .............................................................................. 14

Hadnott, et al. v. Narramore, C.A. 2681-N (M.D. Ala.

1968) .............................................................................. 14

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242 (1937) ....................... 11

Huff, et al. v. White, C.A. 68-223-N (M.D. Ala.) ..... 14

Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corporation v. Epstein,

370 U.S. 713 (1962) ............ 3

Jones, et al. v. Davis, C.A. 967-S (M.D. Ala.) ........... 14

Jones, et al. v. Wilson, C.A. 66-92 (N.D. Ala.), on ap

peal sub nom. Salary v. Wilson (No. 25978, 5th

Cir.) _..............- ............................................................... 14

I l l

Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. en banc,

1966) .............................................................................. 13

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) .....11,17

McNab, et al. v. Griswold, C.A. 2653 (M.D. Ala. 1968) 14

Mitchell v. Johnson, 250 F. Supp. 117 (M.D. Ala.

1966) ......................... 14

Palmer, et al. v. Davis, C.A. 967-S (M.D. Ala.) ....... 14

Palmer, et al. v. Steindorff, C.A. 2679-N (M.D. Ala.

1968) .............................................................................. 14

Preston, et al. v. Mandeville, C.A. 5059-68 (S.D.

Ala.) ..... .......... -........................................... -................ 14

Rabinowitz v. United States, 366 F.2d 34 (5th Cir.

en banc, 1966) ....................................................... 13

Reese, et al. v. Pickering, C.A. 3839-65 (S.D. Ala.

1968) .............................................................................. 14

Richardson, et al. v. Wilson, C.A. 68-300 (N.D. Ala.) 14

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940) .............................. 13

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966)

11,17

Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 U.S. 313 (1958) ............. 11

Turner v. Spencer, 261 F. Sapp. 542 (S.D. Ala.

1966) .......................................... ...... -........................... 14

Umted States v. L. Cohen Grocery Co., 255 U.S. 81

(1921) ......................................... -................................. 10

White v. Crook, 241 F. Supp. 401 (M.D. Ala. 1966)

12n, 14

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) ..................... 11

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 (1948) ............... 11

PAGE

IV

Federal Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1253 ...................................... 3

28 U.S.C. §1331 ................................................................ 2

28 U.S.C. §1343 ................................................................ 2

28 U.S.C. §1865 ................................................................ 15n

28 U.S.C. §2201 ....... 2

28 U.S.C. §2202 .............. 2

28 U.S.C. §2281 ................................................................ 2, 5

28 U.S.C. §2283 ............... ....... ....... ............... ....... .......... 2

28 U.S.C. §2284 ................................................................ 2, 5

42 U.S.C. §1973 ................................................................ 15n

42 U.S.C. §1981 ................................................................ 2

State Statutes-.

Ala. Code Tit. 30, §4 ...................................................... 2

Ala. Code (Supp. 1967) Tit. 30, § 9 ...........................2,4,16

Ala. Code Tit. 30, §10 .............................................2, 4, 9,16

Ala. Code Tit. 30, §15 .................................................... 7

Ala. Code Tit. 30, §18 .................................................... 4, 7

Ala. Code Tit. 30, §20 .............................................. 2, 4, 6, 7

Ala. Code Tit. 30, §21 ............................ 2, 4 ,10 ,12n, 14,17

Ala. Code Tit. 30, §24 ......................................... ......... 2, 4

Ala. Code Tit. 30, §30 .................................................... 2,4

Other Authorities

Kuhn, “ Jury Discrimination: The Next Phase” , 41

U.S.C. Law Rev. 235 (1968) ....................,.................. 15n

Note, “ The Congress, The Court and Jury Selection”,

52 Va. L. Rev. 1069 (1966) ........................................ 15n

PAGE

I n t h e

g>upremi> ©Hurt ni % 'MnxUb Bt&tzs

October Term, 1968

No..................

W illie Carter Sr., J ohn H ead, R ev. P ercy M cShan,

Appellants,

— y.—

J ury Commission of Greene County, Alabama, et al.,

Appellees.

ON A PPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR T H E N O R T H E R N DISTRICT OF ALABAM A

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants appeal from the final judgment of the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama

entered September 13, 1968, refusing to declare Alabama

Code, Title 30, Sections 4 and 21 unconstitutional on their

face because of vagueness and as applied and to enjoin

their operation and enforcement, and further refusing to

declare the all-white jury commission of Greene County,

Alabama unconstitutional. This statement is submitted to

show that this Court has jurisdiction of the appeal and

that substantial questions are presented.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the District Court for the Northern Dis

trict of Alabama is as yet unreported and is set forth in

2

the Appendix, p. la, infra. (Hereinafter, references to the

Appendix will be designated by A.)

Jurisdiction

This is an action for injunctive and declaratory relief

in which the jurisdiction of a District Court of three judges

was invoked under 28 TJ.S.C. §§1331, 1343, 2201, 2202, 2281,

2283 and 2284, and under 42 TJ.S.C. §1981 to vindicate and

enforce rights of the plaintiffs guaranteed by the due

process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment alleged to be violated by a statute of the State

of Alabama (Title 30, §21) governing the qualifications of

jurors and by the practice of selecting only white jury

commissioners by the State’s Governor pursuant to Title

30, §§9 and 10, Code of Alabama (1958), as amended.

The final judgment of the Court below entered Septem

ber 13, 1968, inter alia, adjudged that there is systematic

exclusion of Negroes from jury rolls of Greene County,

Alabama, by reason of purposeful discrimination and en

joined the jury commission, its clerk, and agents from such

exclusion. However, the Court upheld the constitutionality

of the challenged statutory provisions against plaintiffs’

prayer that they be declared unconstitutional on their face.

Notice of Appeal on behalf of appellants Carter, Head,

McShan, and the class they represent was timely filed on

November 7, 1968. A certified copy of the record from the

district court was filed in this court on December 16, 1968

and the Clerk has been advised that it will serve as the

basis for this appeal and the separate appeal of three other

plaintiffs in the district court relating to other issues.1

1 That appeal was docketed here on Dee. 11, 1968 as BoTculich v.

Jury Commission of Greene Co., No. 1255 Misc. O.T. 1968.

3

Receipt of the record was acknowledged by the office of the

Clerk of the Court December 17, 1968.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1253 to review the judgment of the three-judge

district court denying, after notice and hearing, interlocu

tory and permanent injunctive relief against the enforce

ment of the statutes of the State of Alabama on the ground

that they violate the Federal Constitution. See, e.g., Idle-

wild Bon Voyage Liquor Corporation v. Epstein, 370 TJ.S.

713 (1962).

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

The primary statutory provision involved in this litiga

tion is Code of Alabama Tit. 30, Section 21, as amended

Sept. 12, 1966 which reads as follows:

“ The jury commission shall place on the jury roll and

in the jury box the names of all citizens of the County

who are generally reputed to be honest and intelli

gent and are esteemed in the community for their in

tegrity, good character and sound judgment; but no

person must be selected who is under twenty-one or

who is an habitual drunkard, or who, being afflicted

with a permanent disease or physical weakness is unfit

to discharge the duties of a juror; or cannot read

English or who has ever been convicted of any offense

involving moral turpitude. If a person cannot read

English and has all the other qualifications prescribed

herein and is a freeholder or householder his name

may be placed on the jury roll and in the jury box.

No person over the age of sixty five years shall be

registered to serve on a jury or to remain on the panel

of jurors unless willing to do so. When any female

shall have been summoned for jury duty she shall

4

have the right to appear before the trial judge, and

such judge, for good cause shown shall have the judicial

discretion to excuse said person from jury duty. The

foregoing provision shall apply in either regular or

special venire.”

The following additional provisions are material to an

understanding of the issues presented: Code of Alabama,

Tit. 30, Sections 9, 10, 18, 20, 24 and 30. These enactments

are set out in full in the Appendix at pp. 29a-32a, infra.

This action also involves the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

1. Whether Code of Alabama, Title 30 §21 is unconsti

tutionally vague in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

because its requirement that jurors be persons “who are

generally reputed to be honest and intelligent and are

esteemed in the community for their integrity, good char

acter and sound judgment” provides Alabama jury officials

with the opportunity to discriminate on racial and other

grounds, an opportunity shown by the record to have been

resorted to in this case?

2. Whether Alabama’s practice of appointing only white

persons to serve as jury commissioners violates the Four

teenth Amendment where the all-white jury commissioners

customarily resort to the opportunity to discriminate pro

vided by statute or are so unrepresentative of a cross-

section of the community, particularly a community with

a majority black population, that they fail to produce jury

rolls reflecting that cross-section?

5

Statement

A. Introduction

This civil action challenging the constitutionality of

Alabama’s juror selection statute on its face and as ap

plied arises from Greene County, Alabama, the locus of

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129 (1964) (Coleman I ) ;

389 U.S. 22 (1967) (Coleman II). It was initiated by Paul

M. Bokulich, Willie Carter, Sr., John Head, and Rev. Percy

McShan. Paul Bokulich was in 1966 when he was arrested

and charged with grand larceny, a white civil rights worker

associated with the Southern Christian Leadership Con

ference. Arrested at the same time as Bokulich and also

charged with grand larceny were George Greene and

Hubert G. Brown, both Negro civil rights workers. Before

filing this action, Bokulich obtained an order from the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit enjoining and re

straining the prosecution of the criminal action. Since the

action involved a claim of the unconstitutionality of stat

utes of the state of Alabama, it was appropriately tried

by a federal district court of three judges. 28 U.S.C.

§§2281, 2284. George Greene and Hubert Brown subse

quently joined in the civil action as plaintiffs-intervenors.

Appellants Carter, Head and McShan are Negro citizens

and residents of Greene County, and joined in this action

as plaintiffs on behalf of themselves individually and as

representatives of a class consisting of all potentially

eligible Negro jurors of Greene County who are excluded

from such service because of their race.

As to plaintiff Bokulich, and plaintiffs-intervenors Greene

and Brown, the Court below held that the discriminatory

exclusion of Negroes from the grand jury constituted a

violation of both equal protection and due process (A-20a).

6

In considering relief to be granted, however, the Court

held:

The normal and most appropriate method for Bokulich,

Brown and Greene to raise the composition of the

jury roll and the operation of the jury selection sys

tem is in criminal prosecutions in the state courts, if

indictments issue. (A-22a).

The court thus refused to continue in effect the stay of the

state criminal prosecutions. They have taken a separate

appeal to this court from the district court’s refusal to

enjoin their state court prosecutions. (Bokulich, et al. v.

Jury Commission of Greene Co., Ala., et al., No. 1255 Misc.

O.T. 1968.)

With respect to plaintiffs Carter, Head and McShan and

the class they represent, the Court below held:

. . . that Negro citizens of Greene County are dis-

criminatorily excluded from consideration for jury

service, in violation of the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment, and Title 30, §21 has been

unconstitutionally applied to as them. (A-20a).

They, the Court continued, “ . . . are entitled to an injunc

tion against discriminatory exclusion of Negroes from con

sideration for jury service in Greene County.” (A-21a).

In the implementation of the holding, defendants were

ordered to “take prompt action to compile a jury list for

Greene County, Alabama . . . [and] to file with this [Dis

trict] court within sixty days a jury list as so compiled,

showing thereon the information required by Title 30, §20,

Code of Alabama (1958), as amended, plus the race of

each juror, and if available the age of each juror, and a

report setting forth the procedures, system and method by

which said list was compiled. . . . ” (A-27a).

7

But the Court refused to declare §21 unconstitutional

on its face (A-26a) and refused to declare the county jury

commission unconstitutionally constituted (A-27a), and it

is from this portion of the order and judgment that this

appeal is taken.

B. Selection Process of Jury Commissioners and Jurors

The standards and procedure for selecting jury Com

missioners and Jurors are contained in Code of Alabama,

Title 30.

Each county has a jury commission comprised of three

members appointed by the Governor. The Commission is

charged with the duty of preparing a jury roll containing

the names of every citizen living in the county who pos

sesses the prescribed qualifications and who is not exempted

by law from serving on juries.

The selection process contemplated by the statute op

erates in two stages. First there is the collection of names

of substantially all persons potentially eligible for jury

service. The clerk of the Circuit Court may be employed

as clerk of the Commission, Title 30, §15, and in Greene

County was so employed. Title 30, §18 directs the clerk

of the commission to obtain the name of every citizen of

the county over twenty-one and under sixty-five. Sources

from which such names are to be collected are contained in

Title 30, §24, which directs the commission, through its

clerk, to scan the registration lists, the tax assessor’s lists,

any city directories and telephone directories “ and any and'

every source of information from which he may obtain

information, and to visit every precinct at least once each

year.”

The second stage involves application of the statutory

qualifications to the general pool of potential jurors so

8

selected. “ The jury commission . . . shall make in a well

bound book a roll containing the name of every citizen

living in the county who possesses the qualifications herein

prescribed and who is not exempted by law from serving

on juries.” Title 30, §20.

A qualified juror is one who is “generally reputed to

be honest and intelligent . . . and esteemed in the com

munity for [his] integrity, good character and sound

judgment.” Title 30, Section 21.

In Greene County, the clerk of the commission did not

obtain the names of all potentially eligible jurors as pro

vided by §18. She testified below that she never prepared

a list of all potentially eligible persons between the ages

of 21 and 65 (T. 93).* Everyone on the jury roll is con

sidered qualified and remains on the roll unless he dies or

moves away (T. 148). New names are added to the old

roll. Both the clerk and the jury commissioners secure

names of persons suggested for consideration as new

jurors.

In securing the new names, the clerk testified that she

did not use the tax assessor’s list (T. I l l ) , that she did

not use all available telephone directories (T. 100), and

that she did not know the reputation of most of the Negroes

in the county (T. 138). She visits each of the eleven beats

in the county annually and talks with persons she knows

to secure names (Yarborough, Deposition, p. 13). The

names suggested to her and to the commissioners by

Negroes in the community are accepted without further

investigation to see that they meet the qualifications neces

sary (T. 136-137).

The commissioners, who exercise their subjective judg

ment in applying these qualifications, are appointed pursu

* ( “ T.” references are to the transcript of the. trial below).

9

ant to statute. Title 30, §10 provides that they are to be

appointed by the governor. Title 30, §9 requires the com

missioners so appointed to “ be persons reputed for their

fairness, impartiality, integrity and good judgment.”

In practice, the Jury Commissioners appointed in Greene

County are now and, as far as appellants have been able

to ascertain have always been, entirely white (T. 88). They

share with the clerk the responsibility for adding new

names to the general pool. Their procedures are even less

formalized than the clerk’s. The commissioners “ ask

around” for names of possible jurors usually in the area

of the county in which they reside (T. 183). At the

August 1966 meeting one commissioner was new and sub

mitted no names (T. 143). Another had been ill and un

able to seek many names at all (T. 142). The third could

remember only one Negro name that he suggested (Gray

Deposition, p. 17).

Thus in practice, as the court below noted, “ the system

operate[s] exactly in reverse from what the state statutes

contemplate.” (A-12a) It produces a small group of indi

vidually selected or recommended names for consideration,

provided by white administrators and citizens with limited

contact with the Negro community. No meaningful pro

cedure exists for the inclusion of Negro names.

Evidence produced at the trial below established that

although approximately 74% of the male population of

Green County over 21 years of age was Negro, at no time

during the period from 1961 to 1966 did the percentage

of Negroes on the jury roll exceed 19% (Summary of

Evidence, E.132).

The 1961 jury roll was 95% white, 5% Negro. Before

the extraordinary session of January 1967, it had become

81% white, 19% Negro (Summary of Evidence, R.132).

10

After the extraordinary session, in which women were

added to the roll for the first time, it was 68% white, 32%

Negro (Summary of Evidence, R.132). This is to be con

trasted with the estimate of population at that time of

65% Negro and 35% white (A-15a).

Appellants contend that this gross disparity resulted

not only from the discriminatory administration of the

statutes as the district court found but principally from

the vague statutory standards for juror qualification which

invested the all white jury commissioners with sufficient

discretion to permit them to discriminate on racial grounds.

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED ARE SUBSTANTIAL

I.

Code of Alabama, Title 30, §21 Is Unconstitutionally

Vague Because It Permits the Arbitrary Exclusion of

Negroes From Service As Jurors In Violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

Alabama’s statutory standards for prospective jurors

are vague. Jury Commissioners must select only those

persons:

“ generally reputed to be honest and intelligent . . .

and . . . esteemed in the community for their integ

rity, good character and sound judgment.” Code of

Ala., Tit. 30, §21.

In numerous cases involving a variety of rights, this

Court has declared similar statutory or regulatory language

permitting public officials to make subjective decisions un

constitutionally vague: United States v. L. Cohen Grocery

Co., 255 U.S. 81 (1921); economic regulation legislation:

11

“Unreasonable Charges” ; Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360

(1964), due process: “ subversive person” ; Herndon v.

Lowry, 301 U.S. 242 (1937), free speech and assembly:

“ insurrection” ; Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 (1948),

due process and freedom of the press: “ obscene” .

In Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 U.S. 313 (1958), the Court

applied the rule to an ordinance which prohibited soliciting

without a license from the mayor and city council who, in

passing upon the application were to consider the character

of the applicant. Similarly, a statute requiring a certifi

cate of “ good moral character” as a prerequisite to college

admission was invalidated by the Fifth Circuit. Board of

Supervisors v. Ludley, 252 F.2d 372 (5th Cir. 1958), cert,

denied, 358 U.S. 819 (1958).

Because Alabama’s statutory qualifications are vague,

they furnish jury commissioners with an opportunity to

discriminate on a variety of grounds. Cf. Whitus v. Georgia,

385 U.S. 545, 552 (1967); Bostick v. South Carolina, 386

U.S. 479 (1967).

In the hands of all-white jury commissioners, against

the backdrop of the racial history of the state and region,

Alabama’s vague statutory standards provide an oppor

tunity to discriminate on racial grounds. Cf. Louisiana v.

United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965); Davis v. Schnell, 81

F. Supp. 872 (S.D. Ala.), aff’d per curiam, 336 U.S. 933

(1949). In South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301

(1966), this Court, at pp. 312-313 said:

“ . . . the good morals requirements is so vague and sub

jective that it has constituted an open invitation to

abuse at the hands of voting officials.”

The record in this case shows that the opportunity to

discriminate racially has been resorted to in Greene County.

Statistics in the record show:

12

1960 Census, Greene County

Persons over 21 Years of Age

White

%

White Negro

%

Negro

Male 775 26% 2,247 74%

Female 874 24% 2,754 76%

Total 1,649 5,001

Composition of Jury Bolls

1961-65 (Males Only)2

White Males

Year on Jury Bolls

% of 1960 Pop.

(White Males)

Negro Males

on Jury Rolls

% of 1960 Pop.

(Negro Males)

1961 337 43% 16 0.7%

1962 348 45% 26 1%

1963 349 45% 28 1%

1964 — —

1965 382 49% 47 2%

1966

(A-14a)

389 50% 82 4%

The statistics post-1964 are particularly pertinent for

they reflect the jury commission’s performance subsequent

to a declaratory judgment by the district court directing

that the jury selection system be administered in a racially

nondiscriminatory way. Coleman v. Barton, No. 63-4 (N.D.

Ala. June 10, 1964 (A-3a).3 In 1967 the number of whites

on the jury roll was increased to 810 or 49% of the 1960

census figures for adult whites. Negroes on the roll in

2 Until 1966 Alabama restricted jury service to males. See White

V. Crook, 241 F.Supp. 401 (M.D. Ala. 1966); Code of Ala. (Supp.

1967) Tit. 30, §21.

3 Subsequently, in a direct review of Coleman’s murder convic

tion, this Court held that an unrebutted prima facie case of sys

tematic racial exclusion in jury selection in Greene County had

been established. Coleman v. Alabama, 389 U.S. 22 (1967).

13

creased to 388 or 7%% of the 1960 census figure for Negro

adults.4

The Court below found that the practice of racial dis

crimination in jury selection had continued but limited its

relief to an injunction against discriminatory administra

tion of the Alabama statute (A-27a), thus leaving un

touched the vague statutory standards which, by lodging

excessive discretion in the hands of the all-white jury

commissioners, are chiefly accountable for the result of

racially discriminatory jury selection in Greene County and

elsewhere in the state.

This relief was clearly inadequate. As the Fifth Circuit

has said: “ It is this broad discretion located in a non

judiciary office which provides the source of discrimina

tion in the selection of juries.” Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d

698, 713 (5th Cir. en banc 1966); see also Smith v. Texas,

311 U.S. 128 (1940); Rabinowits v. United States, 366 F.2d

34 (5th Cir. en banc 1966). Just four years ago the selec

tion practices of the Greene County jury commission were

declared racially discriminatory and ordered discontinued,

but as the record shows, the practices have persisted. They

have persisted principally because Alabama’s statutory

scheme permitted white jury officials to continue finding

almost no Negroes who in their judgment could meet the

intelligence and character standards of the statute. Cole

man v. Barton, supra.

4 There was testimony at the trial below that by 1967, through

migration of Negroes, the population ratio for all Negroes and all

whites had decreased to 65%-35%. In its opinion, the Court said:

“Assuming that this change was reflected in the numbers of

adults as in non-adults, and that the number of adult whites

remained approximately constant, then the approximate num

ber of adult Negroes in the county (male and female) had

declined from 5001 to 3065, of whom approximately 12%%

were on the rolls in 1967 after the January special meeting.”

(A-15a).

14

Because Title 30, §21 is of state-wide applicability, it is

not surprising that the problem exposed in Greene County

is not restricted to it, but is state-wide. Civil suits suc

cessfully challenging racially discriminatory jury selection

have been brought in federal district courts in counties

throughout the state of Alabama. See, e.g,, Dennard, et al.

v. Baker, C.A. 2654-N (M.D. Ala. 1968) (Barbour County);

Hadnott, et al. v. Narramore, C.A. 2681-N (M.D. Ala. 1968)

(Autauga County); McNab, et al. v. Griswold, C.A. 2653

(M.D. Ala. 1968) (Bullock County); Palmer, et al. v. Stein-

dorff, C.A. 2679-N (M.D. Ala. 1968) (Butler County); Bush,

et al. v. Woolf, C.A. 68-206 (N.D. Ala. 1968) (Calhoun

County); Good, et al. v. Slaughter, C.A. 2677-N (M.D. Ala.

1968) (Crenshaw County); Banks, et al. v. Holley, C.A.

735-E (M.D. Ala. 1967) (Tallapoosa County); Turner v.

Spencer, 261 F.Supp. 342 (S.D. Ala. 1966) (consolidated

from cases which arose in Perry, Hale and Wilcox Coun

ties); Mitchell v. Johnson, 250 F. Supp. 117 (M.D. Ala.

1966) (Macon County); White v. Crook, 241 F.Supp. 401

(M.D. Ala. 1966) (Lowndes County); Reese, et al. v. Pick

ering, C.A. 3839-65 (S.D. Ala. 1968 (Dallas County).

Similar cases have been initiated and are pending in

the following counties: Huff, et al. v. White, C.A. 68-223-N

(M.D. Ala.) (Bibb County); Palmer, et al. v. Davis, C.A.

967-S (M.D. Ala.) (Dale County); Jones, et al. v. Holli

man, C.A. 3944-65 (S.D. Ala.) (Mareng’o County); Preston,

et al. v. Mcmdeville, C.A. 5059-68 (S.D. Ala.) (Mobile

County); Richardson, et al. v. Wilson, C.A. 68-300 (N.D.

Ala.) (Jefferson County); Jones, et al. v. Wilson, C.A. 66-

92 (N.D. Ala.) (Jefferson County), pending on appeal sub

nom Salary v. Wilson (No. 25978, 5th Cir.).

These cases impose a heavy burden on already crowded

court dockets, however their necessity will continue until

jury selection throughout the state is made on the basis of

15

objective standards. This has been the response of Con

gress with respect to invidious discrimination in federal

jury selection,5 and in the area of voting rights.6

Until there are objective standards to guide the discre

tion of jury selectors in Alabama an effective cure to prob

lems of racially disproportionate jury rolls is unlikely.7

5 28 U.S.C. §1865: Qualifications for Jury Service

(b) In making such determination [i.e., juror qualifica

tions], the chief judge of the district court, or such other

district court judge as the plan may provide, shall deem any

person qualified to serve on grand and petit juries in the dis

trict court unless he—

(1) is not a citizen of the United States twenty-one years

old who has resided for a period of one year within the

judicial district;

(2) is unable to read, write, and understand the English

language with a degree of proficiency sufficient to fill out

satisfactorily the juror qualification form;

(3) is unable to speak the English language;

(4) is incapable, by reason of mental or physical infirm

ity, to render satisfactory jury service; or

(5) has a charge pending against him for the commission

of, or has been convicted in a State or Federal court of

record of, a crime punishable by imprisonment for more

than one year and his civil rights have not been restored by

pardon or amnesty.

6 Voting Rights Act of 1965 (42 U.S.C. §1973 et seq.).

7 See Kuhn, “Jury Discrimination: The Next Phase,” 41 U.S.C.

Law Rev. 235, 266-82 (1968); Note, “ The Congress, The Court and

Jury Selection: A Critique of Titles I and II of the Civil Rights

Bill of 1966,” 52 Va. L.Rev. 1069, 1140-56 (1966).

16

II.

The Jury Commission of Greene County Is Uncon-

stitionally Constituted Because It Perpetuates Racially

Discriminatory Juror Selection In Violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

The non-objective standards of juror qualification are

a crucial element in racially discriminatory juror selection,

as appellants have urged. An equally crucial and inter

related element is the racial composition of Alabama’s jury

commissions.

Jury commissions are appointed by the Governor. (Code

of Ala., Tit. 30, §10); members are required to be persons

“ reputed for their fairness, impartiality, integrity and good

judgment.” Code of Ala. (Supp. 1967) Tit. 30, §9.

The Court below held that “the attack on the racial

composition of the commission fails for want of proof.”

(A-20a). However, the record established by compelling in

ference the causal relationship between the all-white char

acteristic of the Greene County jury commission, the ex

cessive statutory discretion and the resulting racial dis

crimination in selection.

Assuming the sincere impartiality of all-white jury com

missioners “ in the reality of the segregated world,” (Brooks

v. Beto, 366 F.2d 1, 12 (5th Cir. en banc, 1966)), the likeli

hood that they would normally be in a position to know

very many Negroes who are “generally reputed to be

honest and intelligent . . . and esteemed in the community

for . . . integrity, good character and sound judgment,”

is slight. Also, given the reality of that world, Negroes

generally are regarded by white jury officials as incapable

of meeting those standards.

17

The Clerk of the Greene County commission testified that

for the previous eleven years all of the commissioners had

been white (T.88). It is judicially noticeable that a Negro

has never been appointed to a jury commission in the state

of Alabama. There was also evidence that the clerk and

the three members of the jury commission (one of whom

was seriously ill and another who was new to the com

mission and had not yet participated in selection) were

almost totally unfamiliar with the Negro community and

relied instead on only eight Negroes and fourteen whites

for recommendations. In fact, the Clerk and one commis

sioner used the same Negro for recommendations (T.182).

The too-discretion-giving provisions of §21 (Code of Ala.

Tit. 30) are a vice no matter by whom administered,8 but

certainly in the contest of racially segregated southern

society, excessive discretion in the hands of all-white offi

cials is fatal to Negro participation in jury service as it

was in voting. Louisiana v. United States, supra; South

Carolina v. Katsenbach, supra.

Thus so long as the statutory standards of selection re

main unchanged, it is of crucial importance that a jury

commission be representaive of the whole community in

which it functions. Brooks v. Beto, supra. Particularly

must this be so with respect to communities like Greene

in which Negroes constitute so large a majority of the

residents.

8 The provisions of §21 would allow the continued exclusion of

most of the eligible Negroes by virtue of the fact that its provisions

could be misapplied by Negro appointees deemed to be “safe” .

Cf. Brooks v. Beto, supra, Judge Wisdom, concurring opinion.

18

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons probable jurisdiction should

be noted.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Norm an C. A maker

James N. F inney

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Orzell B illingsley, Jr.

1630 Fourth Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Appellants

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe the Northern D istrict of Alabama,

W estern D ivision

Civil Action No. 66-562

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

Paul M. B okulich, W illie Carter, Sr., J ohn H ead, R ev.

P ercy McShan, on their own behalf and on behalf o f

all others similarly situated,

Plaintiffs,

—and—

George Greene and H ubert G. B rown,

Intervenors-Plaintiff s,

J ury Commission of Greene County, A labama, W alter

Morrow, A lbert Gray, and Melvin D urrette, as mem

bers of the Jury Commission of Greene County, Ala

bama, Mary C. Y arborough, as Clerk of the Jury Com

mission of Greene County, Alabama, E. F. H ildreth, as

Circuit Judge for the 17th Judicial District of Alabama,

T. H. B oggs, as District Attorney for Greene County,

Alabama, R alph B anks, Jr,, as County Attorney for

Greene County, Alabama, and L urlene B. W allace, as

Governor of the State of Alabama,

Defendants.

2a

Before Godbold, Circuit Judge, and Grooms and Allgood,

District Judges.

Godbold, Circuit Judge:

This suit is an attack on the jury system of Greene

County, Alabama. The plaintiffs charge that there is

systematic exclusion of Negroes from grand and petit juries

by reason of purposeful discrimination, in violation of the

Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of

the State of Alabama. They charge that Tit. 30, §§4 and 21

of the Code of Alabama (1958) establishing qualifications

for jurors are, on their face and as applied, in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States. And they claim that the all-white jury com

mission of Greene County is unconstitutionally constituted.

Both declaratory and injunctive relief are sought. Juris

diction of this court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1343 and

42 U.S.C.A. §1983. A three-judge court has been convened

pursuant to 28 U.S.C.A. §2281. Notice of the suit has been

given to the Attorney General and Governor of Alabama

as required by 28 U.S.C.A. §2284(2).

The court has considered the evidence consisting of oral

testimony, testimony by deposition, numerous exhibits, and

stipulations of the parties, and pursuant to Fed. R. Civ.

P. 52 makes and enters in this opinion the appropriate

findings of fact and conclusions of law.

Each plaintiff sues on his own behalf and, pursuant to

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23, on behalf of a class of those similarly

situated. Plaintiff Paul Bokulich is a white civil rights

wmrker associated with the Southern Christian Leadership

Conference. He was arrested in Greene County and

charged with two counts of grand larceny. His arrest

followed soon after a sharply-contested primary election

in which Negroes were successful candidates for county

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

3a

office. Plaintiffs Willie Carter, Sr., John Head and Rev.

Percy McShan are Negro residents of Greene County who

allege that they are qualified under the laws of Alabama

to serve as jurors in the Circuit Court of Greene County

and desire to serve but never have been summoned for

jury service. Plaintiffs-intervenors George Greene and

Hubert G. Brown are Negro civil rights workers for the

Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. While work

ing in Greene County in connection with the general elec

tion to be held in November 1966 they were arrested on

charges of grand larceny.

Temporary restraining orders have been granted against

presentation to the Greene County grand jury of charges

against Bokulich, Greene and Brown.

The defendants are the members and the clerk of the

Greene County jury commission, the Circuit Judge and

District Attorney of the state judicial circuit in which

Greene County is located, the County Attorney, and the

then Governor of Alabama.

The claim of systematic exclusion of Negroes from the

Greene County jury roll has been in the courts before.

Coleman v. Barton, No. 63-4, N.D. Ala., June 10, 1964, was

a suit against the members and clerk of the jury commis

sion. The district judge granted a declaratory judgment

but on grounds of comity declined to grant injunctive re

lief. Pertinent extracts from the judgment then entered

are as follows:

“ 1. The Jury Commission of Greene County, Ala

bama, is under a statutory duty of seeing that the

names of every person possessing the qualifications to

serve as jurors, and not exempt by law from jury duty,

be placed on the jury roll and in the jury box of said

County.

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

4a

“2. The Clerk of the Jury Commission of Greene

County, Alabama, is under a duty to comply with

Section 24 of Title 30 of the Code of Alabama, 1940,

to visit every precinct in Greene County at least once

a year to enable the Jury Commission to properly per

form its duties as Commissioners as required by law.

“3. The jury commissioners of Greene County, Ala

bama, are under a duty to familiarize themselves with

the qualifications of eligible jurors without regard to

race or color.

“ 4. The jurors be selected and the roll made up and

the box filled on the basis of individual qualifications

and not as a member of a race.

“5. No person otherwise qualified be excluded from

jury service because of his race.

“ 6. The Commission not pursue a course of conduct

in the administration of its office which will operate

to discriminate in the selection of jurors on racial

grounds.

“7. In making up and establishing the jury roll and

in filling the jury box mere symbolic or token repre

sentation of Negroes will not meet the constitutional

requirements and that numerical or proportional limi

tations as to race are forbidden.

“ 8. The jury roll and the jury box as presently

constituted be examined for compliance with these

standards and the declaration herein made.”

Contemporaneously the same Coleman was making his

way through the state courts, and the United States Su

preme Court, on a direct appeal from a conviction of

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

5a

murder in Greene County.1 The conclusion of the United

States Supreme Court in its second opinion, 389 U.S. 22,

88 S.Ct. 2, 19 L.Ed. 2d 22, was that Coleman had estab

lished a prima facie case of denial of equal protection by

systematic exclusion of Negroes from Greene County

juries, and the state had not adduced evidence sufficient

to rebut the prima facie case.

1. Standing.

Brown and George Greene are Negroes, charges against

whom are proposed to be submitted to the grand jury.

Their standing to sue is apparent. Bokulich does not lack

standing because he is white. Rabinowits v. United States,

366 F.2d 34 (5th Cir. 1966); Rabat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d

698 (5th Cir. 1966); United States v. Hunt, 265 F. Supp.

178 (W.D. Tex., 1967); Allen v. State, 110 Ga. App. 56, 137

S.E. 2d 711 (1964); State v. Lowry, 263 N.C. 536, 139 S.E.

2d 870 (1965).2

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

1 Coleman v. State, 276 Ala. 513, 164 So. 2d 704 (1963), rev’d,

377 U.S. 129, 84 S.Ct. 1152, 12 L.Ed. 2d 190 (1964), remanded after

reversal to trial court for hearing on motion for new trial, 276 Ala.

518, 164 So. 2d 708 (per curiam), 280 Ala. 509, 195 So. 2d 800

(affirming trial court’s denial of motion for new trial), rev’d, 389

U.S. 22, 88 S.Ct. 2, 19 L.Ed. 2d 22 (1967) (per curiam), judgment

affirming trial court vacated, conviction annulled and. remanded

with direction to quash the indictment, Nov. 27, 1967, unpublished

order, Ala. Sup. Ct. (2d Div. 487).

2 Murphy v. Holman, 242 F. Supp. 480 (M.D. Ala. 1965), Blau-

velt, v. Holman, 237 F. Supp. 385 (M.D. Ala. 1964), Hollis v. Ellis,

201 F. Supp. 616 (S.D. Tex. 1961), and Alexander v. State, 160

Tex. Crim. App. 460, 274 S.W. 2d 81, cert, denied 348 U.S. 872,

75 S.Ct. 108, 99 L.Ed. 686 (1954), hold that a white, man may not

raise the issue of exclusion of Negroes from the jury. In none of

those cases was there shown to be substantial identity of interest or

concern of the complaining party with the group alleged to be ex-

6a

Head was shown to meet standards for jurors established

by Alabama law.3 We find that he represents the interests

of a class composed of Negro citizens of Greene County

qualified under state law for jury service, entitled to be

considered for such service, and in such consideration to

have applied to them non-discriminatory standards and

procedures, and as such he has standing to sue. Billingsley

v. Clayton, 359 F.2d 13 (5th Cir.), cert, denied 385 U.S.

841, 87 S.Ct. 92, 17 L.Ed. 2d 74 (1966); White v. Crook,

251 F. Supp. 401 (M.D. Ala. 1966); Mitchell v. Johnson,

250 F. Supp. 117 (M.D. Ala. 1966); Brown v. Rutter, 139

F. Supp. 679 (W.D. Ky. 1956).

2. The selection methods of the jury commission.

There is a jury commission of three members in each

county appointed by the governor. The clerk of the Cir

cuit Court may be employed as clerk of the commission,

Tit. 30, §15, and in Greene County was so employed. The

commission is charged with the duty of preparing a jury

roll containing the name of every citizen living in the

county who possesses the prescribed qualifications and

who is not exempted by law from serving on juries. Tit.

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

eluded. We are concerned with the essential realities of the situa

tion. The case in which the complaining party is of the same racial

group as that alleged to be excluded is the clearest instance of

potential violation of equal protection, but it does not set the outer

limits of equal protection guarantees or of the right to complain of

violations thereof. Nor does the “same class” theory limit due

process, the requirements of basic fairness of trial and the integrity

of the fact finding process. In the exclusion of an identifiable class

from jury service equal protection and due process merge. Labat

v. Bennett, supra; United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263

F.2d 71, 81 (5th Cir. 1959).

3 There was no such proof as to McShan and Carter.

7a

30, §§20, 21 and 24. Tit. 30, §21 prescribes the qualifica

tions and is quoted in the margin.4 *

The statutory scheme for the selection process begins

with the names of substantially all persons potentially eli

gible for jury service and that group then is narrowed to

exclude those not eligible. See. 18 provides:

The clerk of the jury commission shall, under the di

rection of the jury commission obtain the name of

every citizen of the county over twenty-one and under

sixty-five years of age and their occupation, place of

residence and place of business, and shall perform all

such other duties required of him by law under the

direction of the jury commission.6

This section, as well as §§20 and 21, was amended by Act

No. 285, Acts of Alabama, Special Session 1966, p. 428,

adopted September 12, 1966, so as to embrace all citizens

rather than male citizens only.

4 “ Section 21. The jury commission shall place on the jury roll

and in the jury box the names of all citizens of the county who are

generally reputed to be honest and intelligent and are esteemed

in the community for their integrity, good character and sound

judgment; but no person must be selected who is under twenty-one

or who is an habitual drunkard, or who, being afflicted with a per

manent disease or physical weakness is unfit to discharge the duties

of a juror; or cannot read English or who has ever been convicted

of any offense involving moral turpitude. If a person cannot read

English and has all the other qualifications prescribed herein and

is a freeholder or householder his name may be placed on the. jury

roll and in the jury box. No person over the age of sixty-five years

shall be required to serve on a jury or to remain on the panel of

jurors unless willing to do so. When any female shall have been

summoned for jury duty she shall have the right to appear before

the trial Judge, and such Judge, for good cause shown, shall have

the judicial discretion to excuse said person from jury duty. The

foregoing provision shall apply in either regular or special venire.”

6 Under §21 persons over the age of 65 are not required to serve

but may do so if willing.

Opinion by Godbold, G.J.

8a

The commission is directed to require the clerk to scan

the registration lists, the tax assessor’s lists, any city di

rectories and telephone directories “ and any and every

source of information from which he may obtain informa

tion, and to visit every precinct at least once each year.”

Tit. 30, §24.

Necessarily there are two steps in the selection of jurors

for the jury roll. First there must be a selection of per

sons to be considered, i.e., the persons to whom the com

missioners are to apply the statutory qualifications. Then

the criteria of the statutes must be applied to those who

are up for consideration.6* The end product of the system

established by the Alabama legislature is placing on the

jury roll the names of all adult persons who are qualified

and not exempted. “ The jury commission * * * shall make

in a well bound book a roll containing the name of every

citizen living in the county who possesses the qualifica

tions herein prescribed and who is not exempted by law

from serving on juries.” Tit. 30, §20. “The jury commis

sion shall place on the jury roll and in the jury box the

names of all citizens of the county who are generally re

puted (etc.).” Tit. 30, §21. “ The jury commission is

charged with the duty of seeing that the name of every

person possessing the qualifications prescribed in this chap

ter to serve as a juror and not exempted by law from jury

duty, is placed on the jury roll and in the jury box.” Tit.

30, §24. These directions of the statute have been re

affirmed by the Supreme Court of Alabama:

5a “ The sole purpose of these requirements [of the full list di

rected by §18, and use of the sources of information directed by

§24 to be considered] is to insure that the jury commissioners will

have as complete a list as possible of names, compiled on an ob

jective basis, from which to select qualified jurors.” Mitchell v.

Johnson, 250 F. Supp. 117, 123 (M.D. Ala. 1966).

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

9a

The first step [in obtaining jurors to serve on grand

and petit juries] is to get only qualified men on the

jury roll. That is those having the qualifications pre

scribed by law and not exempt. The names of all

such men in the county should be placed on the roll

and in the jury box each year.

Fikes v. State, 263 Ala. 89, 95, 81 So. 2d 303, 309 (1955),

rev’d on other grounds, 352 U.S. 191, 77 S.Ct. 281, 1 L.Ed.

2d 246 (1957), and by the Court of Appeals of Alabama,

Inter-Ocean Casualty Co. v. Banks, 32 Ala. App. 225, 23

So. 2d 874 (1945). Failure to put on the roll the name of

every qualified person may not be the basis for quashing

an indictment or venire absent fraud or a denial of con

stitutional rights, Fikes v. State, supra, at 96, 81 So. 2d at

309, but substantial compliance with these legislative safe

guards established to protect litigants and to insure a fair

trial by an impartial jury is necessary in order to safe

guard the administration of justice. Inter-Ocean Casualty

Co. v. Banks, supra.

The manner is which the system, actually works in Greene

County is generally as follows. The clerk does not obtain

the names of all potentially eligible jurors as provided by

§18, in fact was not aware that the statute directed that

this be done and knew of no way in which she could do it.

The starting point each year is last year’s roll. Everyone

thereon is considered to be qualified and remains on the

roll unless he dies or moves away (or, presumably, is con

victed of a felony). New names are added to the old roll.

Almost all of the work of the commission is devoted to

securing names of persons suggested for consideration as

new jurors. The clerk performs some duties directed to

ward securing such names. This is a part-time task, done

Opinion by Godbold, G.J.

10a

without compensation, in spare time available from per

formance of her duties as clerk of the Circuit Court, She

uses voter lists but not the tax assessor’s lists. Telephone

directories for some of the communities are referred to,

city directories not at all since Greene County is largely

rural.

The clerk goes into each of the eleven beats or precincts

annually, usually one time. Her trips out into the county

for this purpose never consume a full day. At various

places in the county she talks with persons she knows and

secures suggested names. She is acquainted with a good

many Negroes, but very few “ out in the county.” She does

not know the reputation of most of the Negroes in the

county. Because of her duties as clerk of the Circuit Court

the names and reputations of Negroes most familiar to

her are those who have been convicted of crime or have

been “ in trouble.” She does not know any Negro ministers,

does not seek names from any Negro or white churches or

fraternal organizations. She obtains some names from the

county’s Negro deputy sheriff.

The commission members also secure some names, but

on a basis no more regular or formalized than the efforts

of the clerk. The commissioners “ask around,” each usu

ally in the area of the county where he resides, and secure

a few names, chiefly white persons.6 Some of the names

are obtained from public officials, substantially all of whom

are white.

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

6 The commissioner who concentrates on four precincts in the

south of the county could not say that he visited each of those

precincts in the year August 1965-August 1966. The commissioner

who had been concentrating on the northern precincts had been

ill in August 1966, and his participation in affairs of the commis

sion around that time is acknowledged to have been nominal.

11a

One commissioner testified that he asked for names and

that if people didn’t give him names he could not submit

them.7 He accepts pay for one day’s work each year, stat

ing that he does not have a lot of time to put on jury

commission work. The same commissioner considered that

Negroes are best able to judge which Negroes are good

and outstanding citizens and best qualified for jury ser

vice, that the best place to get information about the Negro

citizen is from Negroes. He takes the word of those who

recommend people, checks no further and sees no need to

check further, considering that he is to rely on the judg

ment of others.7a He makes no inquiry or determination

whether persons suggested can read or write, although §21

excludes persons who cannot read English. Neither com

missioners nor clerk have any social contacts with Negroes

or belong to any of the same organizations.

Through its yearly meeting in August, 1966, the jury

commission met once each year usually for one day, some

times for two, to prepare a new roll.8 New names pre

sented by clerk and commissioners, and some sent in by

letter, were considered. The clerk checked them against

7 A portion of his testimony was as follows:

Q. And these are the four precincts you provided names

for? A. That I sort of worked around.

Q. Am I also correct you could not find any list that you

submitted to the jury commission? A. I couldn’t find them

when they wouldn’t submit them to me.

Q. Pardon A. They were not submitted; there was no

way for me to find them: I asked for them, and that is all

I could do ; if they don’t send them, I can’t submit them.

7a The clerk testified that if one recommending another for jury

duty did not know the reputation of the person recommended there

was no way for her to find it out.

8 An annual meeting is required to be held between August 1

and December 20. Tit. 30, §20.

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

12a

court records of felony convictions. New names decided

upon as acceptable were added to the old roll. The names

of those on the old roll who had died or moved away were

removed.

At the August, 1966 meeting one commissioner was new

and submitted no names, white or Negro, and merely did

clerical work at the meeting. Another had been ill and

able to seek names little if at all. The third could remember

one Negro name that he suggested. This commissioner

brought the name, or names, he proposed on a trade bill

he had received, and after so using it threw it away. All

lists of suggested names were destroyed. As a result of

that meeting the number of Negro names on the jury roll

increased by 37. (Approximately 39 were added but it is

estimated that two were lost by death or removal outside

the country.) Approximately 32 of those names came from

lists given the clerk or commissioners by others. The testi

mony is that at the one-day August meeting the entire

voter list was scanned. It contained the names of around

2,000 Negroes.

Thus in practice, through the August, 1966 meeting the

system operated exactly in reverse from what the state

statutes contemplate. It produced a small group of indi

vidually selected or recommended names for consideration.

Those potentially qualified but whose names were never

focused upon were given no consideration. Those who pre

pared the roll and administered the system were white

and with limited means of contact with the Negro com

munity. Though they recognized that the most pertinent

information as to which Negroes do, and which do not,

meet the statutory qualifications comes from Negroes there

was no meaningful procedure by which Negro names were

fed into the machinery for consideration or effectual means

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

13a

of communication by which the knowledge possessed by

the Negro community was utilized. In practice most of

the work of the commission has been devoted to the func

tion of securing names to be considered. Once a name has

come up for consideration it usually has been added to the

rolls unless that person has been convicted of a felony.

The function of applying the statutory criteria has been

carried out only in part, or by accepting as conclusive the

judgment of others, and for some criteria not at all.

Testimony that most of the emigration out of the county

is by younger and better educated Negroes, tending to

leave in the county those older and illiterate, proves little

in the overall picture. In late 1966 there were at least an

estimated 2,000 Negroes on the voting rolls.9 The minimum

voting age in Alabama is 21. It cannot be presumed that

all of these adults, or anywhere near all, were over age

65, which in any event is a basis for excuse and not ex

clusion, or were unable to read English and not free

holders. (In any event it appears that the requirement of

ability to read English has been the subject of little in

quiry.)

The grand jury panel which met and would have con

sidered the charges against Bokulich had it not been en

joined consisted of ten whites and eight Negroes. The

racial composition of a single drawn jury panel cannot

cure the disparity on the roll or the deficient system by

which the roll is set up and maintained.

In January, 1967, after this suit was filed, an extraordi

nary session of the jury commission was held. Part of its

work was to add females to the jury list, as a result of

9 Between November 8, 1965 and August 16, 1966 federal voting

registrars registered approximately 1800 to 1900 Negroes as voters

in Greene County.

Opinion by Godbold, G.J.

14a

the September, 1966, amendments by the Alabama legis

lature extending jury service to women. The procedure

for obtaining names to be added to the list, including the

names of Negroes, was the same as that previously em

ployed. There is evidence that more persons, including

more Negroes, were asked for suggestions than in the past,

but the system remained the same.10

3.

We turn to consideration of the statistical results pro

duced by the operation of the system.

1960 Census, Greene County,

Persons over 21 Years of Age

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

% %

White White Negro Negro

Male 775 26% 2,247 74%

Female 874 24% 2,754 76%

Total 1,649 5,001

Composition of Jury Rolls,

1961-65 (Males Only)

White Males % of 1960 Pop. Negro Males % of 1960 Pop.

Year on Jury Bolls (White Males) on J ury Bolls (Negro Males)

1961 337 43% 16 0.7%

1962 348 45% 26 1%

1963 349 45% 28 1%

1964 — —

1965 382 49% 47 2%

1966 389 50% 82 4%

10 “ [T]he mere change in state law, whose previous commands

had already been consciously ignored, did not remove the central

15a

The January, 1967 meeting of the jury commission in

creased the number of whites and Negroes, a substantial

part of the increase coming from inclusion of females for

the first time. Whites on the roll increased to 810, which

was 49% of the 1960 census figure for adult white males

and females. Negroes on the roll increased to 388, which

was 7% % of the 1960 census figure for adult Negro males

and females. There was testimony that by 1967, through

migration of Negroes, the population ratio for all Negroes

and all whites had decreased to 65%-35%. Assuming that

this change was reflected in the numbers of adults as in

non-adults, and that the number of adult whites remained

approximately constant, then the approximate number of

adult Negroes in the county (male and female) had de

clined from 5001 to 3065, of whom approximately 12%%

were on the rolls in 1967 after the January special meeting.

Recognizing the assumptions and approximations involved

that prevent exact figures, the disparity is nevertheless

evident, for at the same time approximately half of the

adult whites (male and female) were on the rolls, a con

tinuation of the previous practice of maintaining on the

roll approximately half of the eligible white population.

In 1961 the jury roll was 95% white, 5% Negro. Before

the extraordinary session of January 1967 it had become

81% white, 19% Negro. After the extraordinary session it

was 68% white, 32% Negro. This is to be contrasted with

the estimate of population at that time of 65% Negro and

35% white.

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

issue of the pattern and practice of racial discrimination. The

change of merely one of the sources or tools of the conduct did

not demonstrate a change in the conduct itself.” Pullum v. Greene,

5 Cir. 1968, 396 F.2d 251, 254 (5th Cir. 1968).

16a

The discriminatory administration of jury selection laws

fair on their face achieving a result of exclusion of Ne

groes from juries has been a violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment for almost 100 years. Neal v. Delaware, 103

U.S. 370, 26 L.Ed. 567 (1881). Discrimination in the selec

tion of grand juries has been the basis for reversal of

state criminal convictions since 1883. Bush v. Kentucky,

107 U.S. 110, 1 S.Ct. 625, 27 L.Ed. 354 (1883).

It is part of the established tradition in the use of

juries as instruments of public justice that the jury

be a body truly representative of the community. For

racial discrimination to result in the exclusion from

jury service of otherwise qualified groups not only

violates our Constitution and the laws enacted under

it but is at war with our basic concepts of a demo

cratic society and a representative government. We

must consider this record in the light of these impor

tant principles. The fact that the written words of a

state’s laws hold out a promise that no such discrim

ination will be practiced is not enough. The Fourteenth

Amendment requires that equal protection to all must

be given—not merely promised.

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 130, 61 S.Ct. 164, 165, 85

L.Ed. 84, 86 (1940).

The Constitution does not require representation of a

litigant’s race on the jury panel which tries his case, Bush

v. Kentucky, supra. It does not demand that the jury roll

or venire be a perfect mirror of the community or accu

rately reflect the proportionate strength of every identifi

able group. Sivain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 85 S.Ct. 824,

13 L.Ed. 2d 759 (1965). It does require that there be no

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

17a

systematic exclusion of Negroes on account of race from

participation as jurors in the administration of justice.11

The statistical results produced by the system employed

in Greene County, and the testimony of those who admin

ister the system, establish that there is invalid exclusion

of Negroes on a racially discriminatory basis. The modus

operandi of the selection system, as described by those in

charge of it, rather than satisfactorily explaining dispari

ties reaffirms what the figures show, that there has been

followed “a course of conduct which results in discrimina

tion ‘in the selection of jurors on racial grounds.’ ” 12

Davis v. Davis, 361 F.2d 770 (5th Cir. 1966); United States

ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53 (5th Cir. 1962); White

v. Crook, supra.

The Constitution easts upon jury commissioners, as judi

cial administrators, affirmative duties which must be car

ried out in order to have a constitutionally secure system.

—Cassell v. Texas, supra, at 289, 70 S.Ct. at 633, 94

L.Ed. at 848. “When the commissioners were appointed as

judicial administrative officials, it was their duty to fa-

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

11 Discrimination against Negroes is not the only factor produc

ing imbalances in jury selection which may be unconstitutional.

Prior to its recent amendment the provisions of Tit. 30, §21, quoted

supra, denying women the right to serve on juries, was held un

constitutional. White v. Crook, supra. Exclusion of persons of

identifiable national origin (Mexican-Americans) has been struck

down. Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475, 74 St.Ct, 667, 98 L.Ed.

866 (1954). Maryland has held invalid discrimination on religious

grounds. Schowgurow v. State, 240 Md. 121, 213 A.2d 475 (1965).

Those of low economic status have been kept off the rolls. E.g.,

Labat v. Bennett, supra. California has disciplined a prosecuting

attorney who assisted the jury commissioner in eliminating defense-

prone jurors from the jury rolls. Noland v. State Bar, 63 Cal.2d

298, 405 P.2d 129 (1965).

12 Akins v. Texas, 325 U.S. 398, 403, 65 S.Ct. 1276, 1279, 89 L.Ed.

1692, 1696 (1945).

18a

miliarize themselves fairly with the qualifications of the

eligible jurors of the county without regard to race and

color. They did not do so here, and the result has been

racial discrimination. We repeat the recent statement of

Chief Justice Stone in Hill v. Texas, 316 US 400, 404, 86

L ed 1559, 1562, 62 S Ct 1159:

‘Discrimination can arise from the action of commission

ers who exclude all negroes whom they do not know to be

qualified and who neither know nor seek to learn whether

there are in fact any qualified to serve. In such a case,

discrimination necessarily results where there are quali

fied negroes available for jury service.’ ”

—Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559, 561, 73 S.Ct. 891, 892,

97 L.Ed. 1244, 1247 (1953): “ The Jury Commissioners,

and the other officials responsible for the selection of this

panel, were under a constitutional duty to follow a pro

cedure— ‘a course of conduct’—which would not ‘operate to

discriminate in the selection of jurors on racial grounds.’

Hill v. Texas, 316 US 400, 404, 86 L ed 1559, 1562, 62

S Ct 1159 (1942). If they failed in that duty, then this

conviction must be reversed—no matter how strong the

evidence of petitioner’s guilt.”

—United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, supra, at 65

(5th Cir. 1962): “Those same cases, however, and others,

recognize a positive, affirmative duty on the part of the

jury commissioners and other state officials. . . . ”

Conscious or intentional failure of jury commissioners

to carry out their duties, or evil motive, or lack of good

faith, is not necessary for a system to be unconstitutional

in its operation.

—Vanleeward v. Rutledge, 369 F.2d 584, 586 (5th Cir.

1966). “ It is not necessary to determine that any of the

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

19a

commissioners, consciously or intentionally, failed to carry

out the duties of their office, to conclude that the jury

list from which the panel that tried Vanleeward was se-

lected was totally defective.”

—United States ex ret. Seals v. Wiman, supra, at 65.

“ [I]t is not necessary to go so far as to establish ill will,

evil motive, or absence of good faith, but objective results

are largely to be relied on in the application of the con

stitutional test.”

The consequences of the discrimination resulting from

failure to seek out and become acquainted with the quali

fications of Negroes were described in Smith v. Texas,

supra, at 132, 61 S.Ct. at 166, 85 L.Ed. at 87. “Where jury

commissioners limit those from whom grand juries are

selected to their own personal acquaintance, discrimina

tion can arise from commissioners who know no negroes

as well as from commissioners who know but eliminate

them. If there has been discrimination, whether accom

plished ingeniously or ingenuously, the conviction cannot

stand.”

Alabama is among the most enlightened of the states in

requiring that broadly inclusive community lists be con

sulted and that all eligible persons be shown on the rolls.13

The purpose of the Alabama system is to insure that the

jury roll is a cross-section of the community. White v.

Crook, supra; Mitchell v. Johnson, supra. Compliance with

selection procedures set by a state legislature does not

necessarily meet constitutional standards. But if a jury

selection system as provided by the Alabama statutes is

13 See Note, The Congress, The Courts and Jury Selection: A

Critique of Titles I and II of the Civil Rights Bill of 1966, 52 Ya.

L. Rev. 1069, 1079 n. 54 (1966).

Opinion by Oodbold, C.J.

20a

fairly and efficiently administered, without discrimination

and in substantial compliance with the state statutes—

which the state courts of Alabama already require—the

odds are very high that it will produce a constitutional

result of a jury fairly representative of the community.

Failure to comply with state procedures does not neces

sarily produce an unconstitutional exclusion. But the fact

of, and the extent of, the failure in this case to comply

with the procedures and the results contemplated by the

Alabama system is strong evidence of unconstitutionality.

The selection procedures are not validated by the fact

that traditionally the system always has been that way,

or that the clerk and the commissioners are in effect per

sons who as a public service contribute their time and

effort, or that funds are not provided for the commission

to operate in the manner directed by the state statutes

and required by constitutional standards.

We hold that Negro citizens of Greene County are dis-

criminatorily excluded from consideration for jury service,

in violation of the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment, and that Tit. 30, §21 has been uncon

stitutionally applied as to them. We hold also that the

discriminatory exclusion of Negroes is, as to the plain

tiffs Bokulich, Brown and Greene, a violation of both equal

protection and due process.

5.

The attack on racial composition of the commission fails

for want of proof. No proof was adduced except that the

commission in Greene County now is and for many years

has been composed entirely of white men appointed by the

governor.14

14 Cf. Clay v. United States, 5 Cir.,

May 6, 1968].

Opinion by Godbold, C.J.

F.2d [No. 24,991,

21a

The statutory criteria in §21 of good character, honesty,

intelligence, integrity, sound judgment and sobriety are

attacked as facially unconstitutional for vagueness. Many

states join Alabama in some of these requirements and in

excluding convicted felons.16 The Supreme Court has not

held criteria such as these void for vagueness in the selec

tion of jurors. And it has recognized the validity of wide

discretion in jury commissioners. Cassell v. Texas, supra;