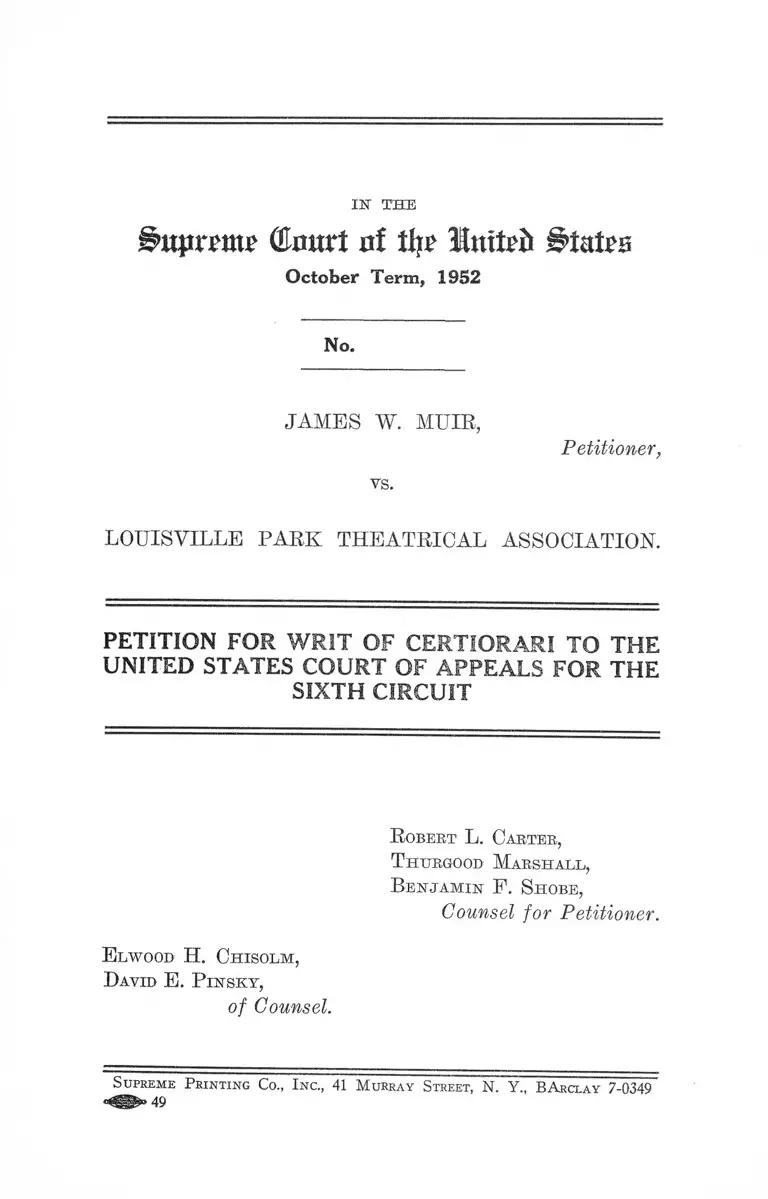

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Public Court Documents

May 20, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Association Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, 1953. 6ed713eb-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e2ecb1c8-06b2-43f0-989a-5fe41f904728/muir-v-louisville-park-theatrical-association-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN' TH E

(tort ni tlir Initri*

October Term, 1952

No.

JAMES W. MUIR,

vs.

Petitioner,

LOUISVILLE PARK THEATRICAL ASSOCIATION.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

SIXTH CIRCUIT

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

Benjamin F. Shobe,

Counsel for Petitioner.

E lwood H. Chisolm,

David E. P insky,

of Counsel.

Supreme Printing Co., Inc., 41 M urray Street, N. Y „ BArclay 7-0349

49

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Opinions Be l o w ............................. 1

J urisdiction .............................................................. 1

Question P resented ............................................................. 2

Statement ............................................. 2

General Background........................... 2

The Leasing Agreement Between the City and

Respondent............................................................ 4

Specifications of E rror .................................................... 7

R easons F or A llowance of the W r i t ............................. 8

1. This case seriously affects the right of Negro

citizens to enjoy the benefits of publicly-owned

recreational facilities......................................... 8

2. Whether the respondent’s operations in this

case constitute state action presents a sub

stantial federal question which should be inde

pendently determined by this C ourt................. 11

3. Decisions among state and lower federal courts

with respect to the status of leasing arrange

ments between municipalities and private or

ganizations are in conflict and should be re

solved ................................................................... 14

4. The decision below is in conflict with principles

established in decisions of this Court, particu

larly Nixon v. Herndon ..................................... 18

5. The decision in this case is in conflict with the

principles enunciated by this Court in Nixon

v. Condon, Smith v. Allright and Terry v.

Adams with respect to the delegation of state

authority.............................................................. 20

PAGE

11

6. The decision of the Court below conflicts with

well-settled doctrine of this Court that rights

guaranteed under the 14th Amendment are per

PAGE

sonal and present ........................................... 24

Conclusion..................................................................... 25

A ppendix A—Agreement............................. 26

A ppendix B—Statutes of Kentucky—Applicable to

Parks in Cities of the First-Class.......................... 31

Table of Cases Cited

Baskin v. Brown, 174 F. 2d 391 (C. A. 4th 1949)___ 21n

Beal v. Holcombe, 193 F. 2d 384 (C. A. 5th 1951)___ 9n

Board of Park Commissioners v. Speed, 215 Ky. 319,

285 S. W. 212 (1926) ................................... .13,18, 20

Boyer v. Garrett, 183 F. 2d 582 (C. A. 4th 1950),

cert, denied 340 U. S. 912......................................... 9n

Camp v. Recreation Board for the District of Colum

bia, 104 F. Supp. 10 (D. C. 1952) .......................... 9n

Culver v. City of Warren, 84 Ohio App. 373, 83 N. E.

2d 82 (1948) .................................................. 9n, 12n, 15, 22

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corp., 299 N. Y. 512, 87

N. E. 2d 541 (1949), cert, denied 339 U. S. 981 . . . . 22

Draper v. City of St. Louis, 92 F. Supp. 546 (E. D.

Mo. 1950), appeal dismissed 186 F. 2d 307 (C. A. 8th

1950)........................................................................... 9n

Durkee v. Murphy, 181 Md. 259, 29 A. 2d 253 (1942) 9n

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U. S. 4 5 ________________ 15

Hague v. Congress of Industrial Organization, 307

U. S. 496 ................................................................. 20n

Harris v. City of Daytona Beach, 105 F. Supp. 572

(S. D. Fla. 1952) ....................................................... 9n

Harris v. City of St. Louis, 233 Mo. App. 911, 111

S. W. 2d 995 (1938) ...............................................15,16,22

I l l

Kern v. City Commissioners, 151 Kans. 565,100 P. 2d

709 (1940 ) ...................................................... 9n, 12n, 15, 22

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 149 F. 2d 212

(C. A. 4th 1945), cert, denied 326 U. S. 721 ......... 15, 22, 23

Law v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 78 F.

Supp. 346 (Md, 1948).............................................. 9n

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S. D. W. Va.

1948).............................................................9n,13,15,16,22

Lopez v. Seccombe, 71 F. Supp. 769 (S. D. Cal. 1944) 9n

McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. Ey. Co., 235 U. S. 151 25

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Eegents, 339 U. S. 637 19

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 . . . . 19

Modern Amusements, Inc. v. New Orleans Public

Service, 183 La. 848, 165 So. 137 (1935).............15,16, 23

Nash v. Air Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545 (E. D.

Va. 1949) .......................................................10n,19,22,23

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73 ............................14,15, 20-24

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U. S. 536 ........................ 15,18,19, 20

Norris v. Mayor & City Council of Baltimore, 78 F.

Supp. 451 (Md. 1948)............................................... 10n

Park Commissioners of Ashland v. Shanklin, 304 Ky.

43, 199 S. W. 2d 721 (1947)............................13,14,18, 20

Public Utilities Commission of the District of

Columbia v. Pollack, 343 IT. S. 4 5 1 .......................... 19

Eice v. Arnold, 340 U. S. 848, vacating 45 So. 2d 195

(Fla. 1950), reaffirmed 54 So. 2d 114 (Fla. 1951),

cert, denied 342 U. S. 896 ........................................ 9n

Eice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (C. A. 4th 1947), cert,

denied 333 U. S. 875 .................................................15, 21n

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ............................ 15, 25

Sipuel v. Board of Eegents, 332 U. S. 631 ................. 19

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 ............................15, 20-24

PAGE

IV

Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R, R. Co., 323 U. S.

192 ............................................................................. 15

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ................................ 19

Terry v. Adams,------U. S .------- , 21 U. S. L. Week

4346 (May 4 ,1953)...........................................15, 20-22, 24

Tunstall v. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, 323

U. S. 2 1 0 ................................................................... 15

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299 ................ 15

Warley v. Board of Park Commissioners, 233 Ky

688, 26 S. W. 2d 554 (1930)..................................... 18

Williams v. Kansas City, 104 F. Supp. 848 (W. I) Mo

1952) .................................................................. . gn

Other Authorities Cited

Barnett, What is State Action Under the Fourteenth,

Fifteenth, and Nineteenth Amendments of the Con

stitution? 24 Ore. L. Rev. 227 (1945)____________ Ion

Dulles, America Learns to Play (1940)..................... 8n

Gardner, Recreation’s Part in Mental Health, 45

Recreation 446 (1952) ............................................. 8n

Hewitt, A Backward Glance at ’49, 35 Equity 11

(April, 1950) ............................................................ 12n

Hewitt, The Survey of Summer Stock, 34 Equity 13

(April, 1949) ................................. 12n

Hjelte, The Administration of Public Recreation

(1940) ....................................................................... 8n

Institute for Training in Municipal Administration,

Municipal Recreation Administration (1945) . . . . 8n

National Park Service, U. S. Dept, of Interior, Fees

and Charges for Public Recreation (1939) .......... 10n

PAGE

V

National Recreation Association, Recreation and

Park Year Book (Mid-century edition 1951) ___8n, 9n

Neumeyer, Leisure and Recreation (1936) ............. 8n

Recreation, Encyclopedia of Social Sciences (1934). 8n

Rogers, The Child at Play (1932) ............................ 8n

Slavson, Recreation and the Total Personality (1946) 8n

Steiner, Americans at Play (1933) ............................ 8n

The Thirty-third National Recreation Congress-in

Review, 45 Recreation (1951) ............................... 8n

Statutes Cited

Ky. Rev. Stat. § 97.252 (1948) .................................... 20n

Ky. Rev. Stat. §97.290' (Baldwin’s certified ed., 1942)

as incorporated into Ky. Rev. Stat. § 97.250’ (1948) 20n

{

PAGE

IN THE

(Emtrt rtf ttj? Inttrri States

October Term, 1952

No.

------------------- —o---------— •———

James W. Muir,

Petitioner,

vs.

L ouisville P ark T heatrical A ssociation.

------------------------o--------------------—

p e t i t i o n f o r w r i t o f c e r t i o r a r i t o t h e

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

SIXTH CIRCUIT

Petitioner, James W. Muir, prays that a writ of

certiorari issue to review the judgment of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit entered in the

above-entitled case on February 20, 1953.

Opinions Below

The memorandum opinion of the United States District

Court for the Western District of Kentucky is reported

at 102 F. Supp. 525 (R. 20). The opinion of the Court of

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit is not yet reported and may

be found in the record at page 83.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

February 20, 1953 (R. 83). The jurisdiction of this Court

is invoked under Title 28, United States Code, Section

1251(1).

2

Question Presented

Whether respondent, who leases from the City of Louis

ville a publicly owned and maintained amphitheatre located

in a public park, can refuse petitioner admission thereto

on tender of the required admission fee solely because of

race and color, without violating his rights to equal pro

tection of the laws within the meaning of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Statement

General Background

Petitioner, together with two other plaintiffs below—

Mona Carroll and P. 0. Sweeney—brought an action in

the District Court against the City of Louisville, T. Byrne

Morgan, Director of Parks and Recreation for the City,

and the Louisville Park Theatrical Association, respondent

here. The action, brought as a class suit on behalf all other

Negroes similarly situated, sought to establish the right of

Negro citizens of Louisville to the use of park and recre

ational facilities without discrimination on account of race

and color where such facilities are owned by the City and

maintained in whole or in part out of public funds (R. 2-8).

The City of Louisville maintains segregated parks for

its Negro and white citizens. Since 1928 regulations have

been in effect whereby certain parks are designated for the

exclusive use of white persons while others are maintained

for the exclusive use of Negroes (R. 43). There are 21

white parks with a total acreage of 2,027 acres; in contrast,

10 parks are provided for Negroes with a combined acreage

of 112 acres (R. 44-45).

While neither a golf course, a fishing lake nor an

amphitheatre is provided in the Negro parks, such facilities

are provided by the City in the white parks (R. 43). Plain-

3

tiff Sweeney, desiring to play golf, requested of the City

and its Director of Parks and Recreation permission to play

golf on the above City-operated golf courses. His request

was admittedly denied solely because he was a Negro (R.

43). Similarly, plaintiff Carroll, an infant, through her

father, asked permission to use the fishing lake in Cherokee

Park. This request, too, was denied solely because of

plaintiff Carroll’s race and color (R. 43).

In Iroquois Park, the largest park in Louisville and

one designated for the use of white persons, the City main

tains an open-air amphitheatre known as Iroquois Amphi

theatre (R. 46). Under an agreement with the City, the

Louisville Park Theatrical Association, respondent here,

presents musical entertainment during the summer season.

On July 22, 1949, petitioner, James Muir, sought admission

to Iroquois Amphitheatre to see a performance of “ Blossom

Time” , a musical production presented by respondent

association. Although this was a performance to which

the general public could gain admission by paying an admis

sion fee, respondent refused to sell petitioner a ticket solely

because he was a Negro (R. 19, 47).

The three plaintiffs below instituted this action on

July 28, 1949, seeking a declaratory judgment and injunc

tive relief on the ground that the refusal to admit them

to the several facilities violated the right of each plaintiff

to the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States (R. 2-9). A stipulation of facts was filed on August

6, 1951 (R. 18-19), and on the same date a hearing on the

merits was held in the District Court (R. 41-62).

On September 14, 1951, the District Court filed its

opinion and findings of fact and conclusions of law (R.

20-35). On January 18, 1952, final judgment was entered

(R. 36-38). That court found that the City violated the

Fourteenth Amendment in providing golf facilities for

4

white citizens without furnishing similar recreational

facilities for Negroes. The City was enjoined from exclud

ing plaintiff Sweeney and other Negroes from such golf

courses on the basis of race and color. The District Court

dismissed the complaint with respect to plaintiff Carroll

on the ground that she had failed to produce any evidence

to support her claim that the fishing facilities afforded

Negroes were substantially inferior to those provided for

white persons (R. 37). Plaintiff Carroll took no appeal.

The court also dismissed the complaint as to petitioner,

holding that respondent was a private corporation not

subject to the Fourteenth Amendment. The court further

held that the City, in allowing respondent to lease Iroquois

Amphitheatre for a “ private operation for a short period

of time” , did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment where

there was no showing that Negro organizations were not

allowed to lease the Amphitheatre under similar terms on

a non-discriminatory basis (R. 37). On appeal the Court

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit affirmed (R. 83).

The Leasing Agreement Between the

City and Respondent

The facts with respect to the use of Iroquois Amphi

theatre are not in dispute. They are contained in the

stipulation of facts (R. 18-19, 42-47), three agreements

entered between the Association and the City (R. 62-79)

and the current agreement appended hereto as Appendix A.

In 1938, the Board of Park Commissioners of the City

of Louisville erected an open-air amphitheatre in Iroquois

Park (R. 18). Iroquois Amphitheatre was constructed and

equipped out of public funds supplied by the Federal Works

Progress Administration, with the exception of $5000 con

tributed by respondent (R. 18). Since 1938 a series of

agreements have been in effect between the City and respond

ent, a non-profit domestic corporation, whereby the latter

5

was given the exclusive use of the Amphitheatre during the

summer season.

The first agreement granted respondent the exclusive

use of the Amphitheatre from May 1 until September 30

during the years 1938-1942 (R. 62-71). The second agree

ment extended these provisions for a period of five addi

tional years (R, 71-74). The third agreement, the one in

force at the time petitioner was refused admission, covered

the period 1947-1951 and is substantially similar to the

earlier contracts (R. 74-79).

Under the terms of this agreement, respondent was

granted the exclusive use of the Amphitheatre during the

period May 1 to September 30 for the purpose of rehears

ing or presenting musical, dramatic, athletic or any other

form of entertainment it might select (R. 74-75). Respond

ent was permitted to charge an admission fee, provided

such admission fees and charges were “ reasonable and

consistent with the desire of both [the City and the Associa

tion] to increase the use of Iroquois Park by making the

entertainment presented at said Amphitheatre available

to the public at low cost” (R. 75-76).

Respondent was not required to pay rent. It agreed

to pay the electric bill from May 1 until September 30

and the salaries of all persons employed in connection with

any entertainment provided (R. 76). It further agreed

to pay over to the City all net profits realized from its

operations after deducting the initial $5000 contributed by

it to the cost of constructing the Amphitheatre (R. 77-78).

The Association was required to furnish to the City

on January 1 of each year an audited statement of monies

received and expended in connection with its operation

of the Amphitheatre (R. 77). This statement was also

to include a listing of all entertainment produced under

its auspices during the preceding season, the admission

fees charged, the number of persons attending, and such

6

other information as would help the City in determining

whether the operation of the Amphitheatre had “ in fact

contributed materially to the use and enjoyment of the

park system by the public” (R.77).

The City retained the care, management, and custody

of the Amphitheatre and all its equipment and appurten

ances (R. 78). No new structure could be erected, no work

begun to replace, maintain or repair equipment, appurten

ances or physical property connected with the Amphitheatre

except on the joint decision of the City and respondent

(R. 76).

The City agreed to furnish water (R.76) and to provide

roads, paths and parking areas necessary to accommodate

persons desiring to attend entertainment given under re

spondent’s auspices (R. 77). The City reserved the right

to make and enforce reasonable rules and regulations, to

insure good order, to prohibit any entertainment indecent,

immoral or calculated to create racial or religious antago

nism or to disturb the public peace (R. 79).

The City retained the right to authorize the use of the

Amphitheatre for any purpose not inconsistent with rights

conferred upon respondent (R. 78). However, the City

agreed not to permit any other party to use the Amphi

theatre between May 1 and September 30 for the purpose

of presenting entertainment at which an admission fee is

charged or from which monetary profit is expected unless

such party first sought to sublease the Amphitheatre from

respondent and the latter arbitrarily refused (R. 78).

Finally, the City retained the right to unilaterally terminate

the agreement if it deemed it not in the best interest of

the public (R. 79).

On September 30, 1951, after the filing of the trial

court’s memorandum opinion but before entry of judg

ment, the agreement then in effect between the City and

7

respondent expired. A new agreement was entered which

is set forth in Appendix A. While this agreement was for

the year 1952, it has now been renewed for the year 1953.

This agreement for the first time sets forth the City’s

desire to have “ similar organizations use the facilities of

Iroquois Amphitheatre.” Respondent is granted the ex

clusive right to use the Amphitheatre between June 14 and

August 23. The City expressly agrees that it will not

give permission to any other party to use the Amphitheatre

during the above period without first obtaining the written

consent of respondent. Moreover, this agreement, unlike

its predecessors, does not reserve to the City the right

to overrule an arbitrary refusal to sublease on the part

of respondent. Further, the present lease requires the

payment by respondent of a rental fee of $1000. In most

other respects, the present agreement is the same as the

prior agreements.

Specifications of Error

The court erred:

1. In refusing to hold that respondent was operating

for and on behalf of the Department of Parks and Recrea

tion of the City of Louisville.

2. In refusing to hold that respondent, as lessee of the

City of Louisville, was subject to the same limitations and

restrictions as the City itself with respect to its power to

deny admission or exclude persons solely on the basis of

race and color.

3. In refusing to hold that petitioner had been denied

the equal protection of the laws by respondent’s refusal

to admit him to a city owned structure located in a public

park.

8

Reasons For Allowance of the Writ

1. This case seriously affects the right of Negro citi

zens to enjoy the benefits of publicly-owned recreational

facilities.

Public recreation has come to play an important role in

20th century America.1 Recognition of the importance of

recreation to the maintenance of strong democratic institu

tions has come only within the past thirty to forty years.2

It is now understood that effective recreational outlets are

essential to the proper functioning of many of the impor

tant aspects of modern living. Appropriate recreation is

now considered an essential factor in the development of

sound mental and physical health,3 a necessary aid to the

building of good morale in the armed services,4 and an

effective preventive to juvenile delinquency.5

The public has now accepted the notion that recreation

is properly a governmental function 6 since only if the state

assumes .some obligation in this field can there be any assur

ance that needed recreational facilities will be available to

the large mass of our population.7 * A recent survey lists

1 See Recreation, Encyclopedia o f Social Sciences 176 (1934 );

Dulles, America Learns to Play (1940) ; Steiner, Americans at Play

(1933).

2 Neumeyer, Leisure and Recreation 1-72 (1936). For a statis

tical survey, see National Recreation Association, Recreation and

Park Year Book (Mid-century edition 1951).

3 Gardner, Recreation’s Part in Mental Health, 45 Recreation

446 (1952) ; Slavson, Recreation and the Total Personality, Ch. 1-2

(1946).

4 The Thirty-third National Recreation Congress— in Review,

45 Recreation 370 (1951).

B Rogers, The Child at Play 34-36, 192 (1932).

6 Hjelte, The Administration of Public Recreation 24 (1940).

7 Institute for Training in Municipal Administration, Municipal

Recreation Administration 30 (1945).

9

36 different types of recreational facilities commonly oper

ated by municipalities.8 There are alone 217 publicly-

owned outdoor theatres and 504 publicly-owned stadiums

reported.9

With the increase in governmental operations in this

area, securing equal recreational opportunities for Negroes

without discrimination on account of race or color, as in

other phases of governmental activity, has become a prob

lem which courts have been called upon to resolve.10 Courts

have had little difficulty in bringing recreational facilities

within the reach of the Fourteenth Amendment where they

have been operated exclusively and openly by the state.11

Confusion as to the application of constitutional principles,

however, has arisen where the public recreational facility

was operated pursuant to an agreement between the state

and a private agency, e.g., the leasing arrangement in the

8 National Recreation Association, Recreation and Park Year

Book (Mid-century edition, 1951).

9 Ibid.

10 See Rice v. Arnold, 340 U. S. 848, vacating 45 So. 2d 195

(Fla. 1950), reaffirmed 54 So. 2d 114 (Fla. 1951), cert, denied 342

U. S. 896; Beal v. Holcombe, 193 F. 2d 384 (C. A. 5th 1951); Boyer

v. Garrett, 183 F. 2d 582 (C. A. 4th 1950), cert, denied 340 U. S.

912; Harris v. City of Daytona Bench, 105 F. Supp. 572 (S . D. Fla.

1952) ; Camp v. Recreation Board for the District of Columbia., 104

F. Supp. 10 (D . C. 1952) ; Williams v. Kansas City, 104 F. Supp.

848 (W . D. Mo. 1952), appeal pending; Draper v. City o f St. Louis,

92 F. Supp. 546 (E. D. Mo. 1950), appeal dismissed 186 F. 2d 307

(C. A. 8th, 1950) ; Law v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore,

78 F. Supp. 346 (M d. 1948); Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp.

1004 (S. D. W . Va. 1948); Lopez v. Seccombe, 71 F. Supp. 769

(S . D. Cal. 1944) ; Kern v. City Commissioners, 151 Kan. 565,

100 P. 2d 709 (1940); Durkee v. Murphy, 181 Md. 259, 29 A. 2d

253 (1942 ); Culver v. City o f Warren, 84 Ohio App. 373 83 N E

2d 82 (1948).

11 See Law v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, supra; Beal

v. Holcombe, supra.

10

instant case. The arrangement here involved is not an iso

lated or singular case but a common feature in this field.

A 1939 survey revealed that 128 governmental agencies re

ported that they had leased certain facilities on a commer

cial basis.12 Thirty out of 156 such agencies reporting leased

one or more facilities to a private club or association on a

non-commercial basis.13

The decision of the Court of Appeals will thus have rami

fications far beyond the narrow facts of the instant case.

In the light of this case the constitutional right of Negroes

and other minority groups to receive the services of all

presently leased municipal recreational facilities without

discrimination becomes questionable. If the view of the

court below is correct, Negroes may now be effectively ex

cluded from given public recreational facilities by a simple

leasing device. Indeed, the same stratagem can be used

not only in the case of recreational facilities, but with re

spect to all types of governmental property.14

It is vital for this Court to grant certiorari in this case

in order to determine the extent to which the operation of

a public recreational facility under a leasing arrangement

with a private organization is subject to constitutional limi

tations. Only in this way can Negro citizens be assured of

protection in obtaining the benefits of public recreational

facilities on the basis of equality required by the Four

teenth Amendment.

12 National Park Service, U. S. Dept, o f Interior, Fees and

Charges for Public Recreation, 20-21, 29 (1939).

13 Ibid.

14 Compare Nash v. Air Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545

(E. D. Va. 1949), with Norris v. Mayor & City Council of Baltimore,

78 F. Supp. 451 (M d. 1948).

11

2. Whether the respondent’s operations in this case

constitute state action presents a substantial federal ques

tion which should be independently determined by this

Court.

The stipulations of fact and the terms of the leasing

agreements which provide the predicate of the decision in

this case establish a picture of state ownership and control.

The Department of Public Parks conceived of the construc

tion of Iroquois Amphitheatre as a means of increasing

the use and enjoyment of its public park system (R. 62-63).

It was able to secure all but $5,000 of the necessary funds

from the United States Works Progress Administration

(R. 63). Respondent, which was organized to enable the

general public to enjoy musical and dramatic entertain

ment, agreed to assist the City in procuring the necessary

$5,000 to construct the Amphitheatre and undertook to

present entertainment at the Amphitheatre. Thus, from the

very inception of this relationship respondent acted as the

chosen instrument of the City.

Under the lease in force when this cause arose respond

ent had exclusive use of the Amphitheatre from May 1-Sep-

tember 30 (R. 18, 74-75)—the entire period of its useful

ness for open air presentation. Respondent paid no rent,

and was required to pay all net profits over to the City

(R. 78). It had but a qualified right to set admission prices

(R. 75-76). Moreover, just as any other self-sustaining

governmental agency, respondent was required to submit

an annual report of its operations, including an audited

financial statement (R. 77), and to conduct its activities for

the benefit of the public (R. 75, 76, 77).

The City, on its part, retained the care, management and

custody of the structure. Yet the City could make no repairs

or replacements of any structure or equipment except upon

the joint decision of both parties (R. 76) and retained only

a qualified right to sublease (R. 78). Finally, the City re-

12

served the right to unilaterally terminate the agreement

(R. 79).

These factors, we submit, show clearly that respondent

was acting for and under the supervision and control of the

Department of Public Parks. Indeed, respondent here was

merely aiding the City in accomplishing one of its objec

tives.

The present lease requires the respondent to pay a

modest rental fee of $1000,15 and does not require the sub

mission of an annual financial statement.

Respondent is granted exclusive use for a somewhat

shorter season (June 14 through August 23),16 but the

dates pre-empted are those most favorable for presenta

tion of outdoor cultural entertainment. Furthermore, this

is the traditional outdoor musical season.17

The City can now sublease to others only with respond

ent’s written consent. It may no longer overrule respond

ent’s arbitrary refusal to sublet. The duty to keep and

maintain the structure in good repair is placed upon

respondent. Other than style, the current agreement is iden

tical in all major respects with the one detailed above.

15 Payment of rental is not a crucial indication o f private action.

See Culver v. City of Warren, supra, note 10; Kern v. City Commis

sioners, supra, note 10.

16 This merely conforms more realistically to the period when re

spondent actually presented productions in the outdoor theatre in pre

vious years (R . 19) : July 1-August 10, inclusive, 1947; July 5-

August 14, inclusive, 1948; July 11-August 21, inclusive, 1949; July

10-August 6, inclusive, 1950 and July 6-August 19, inclusive, 1951.

These dates do not include periods when respondent used the prem

ises for rehearsals, etc.

17 Hewitt, A Backward Glance at ’49, 35 Equity 11 (April, 1950);

Hewitt, The Survey of Summer Stock, 34 Equity 13 (April, 1949).

13

Thus, in our view, under the present agreement respond

ent remains an instrument of the state in its operation of

the Iroquois Amphitheatre. The words of the court in

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004, 1008 (S. D. W. Va.

1948), seem particularly appropriate to describe this rela

tionship :

“ Justice would be blind indeed if she failed to

detect the real purpose in this effort of the City

* * * to clothe a public function with the mantle of

private responsibility. ‘ The voice is Jacob’s voice,’

even though ‘ the hands are the hands of Esau. ’ It is

clearly but another in the long series of stratagems

which governing bodies of many white communities

have employed in attempting to deprive the Negro

of his constitutional birthright; the equal protection

of the laws.”

Moreover, it is equally clear under Kentucky law that the

City is required to control the operation of the Amphithea

tre. This duty is imposed upon the Director of the Depart

ment of Parks and Recreation and cannot be delegated.

Park Commissioners of Ashland v. S'hcmMin, 304 Ky. 43,

199 S. W. 2d 721 (1947). In Board of Park Conwiissioners

v. Speed, 215 Ky. 319, 285 8. W. 212 (1926), the court

enjoined the Board of Park Commissioners of Louisville

from entering into a contract with the Louisville Memorial

Commission whereby the latter was to be given the power to

erect and manage an auditorium on public park property.

In so holding, the Court declared at page 333:

“ If an auditorium is to be erected and maintained

upon park property, it must be under the control of

the park board since the board has been designated

by law, and its members elected by popular choice, to

manage and control that property.”

14

More recently, in the Shanklin case, the Court of Appeals

of Kentucky reiterated this view in saying at page 47:

“ It seems to us that the proposed contracts would

in effect give to the various clubs the right and

power to exclude the general public from the use of a

substantial part of the park for an indefinite although

substantial period of time. This would be con

sistent with its free public use. The Board would

surrender its sole and exclusive control of the man

agement of this part of the public property. Its

dominion and administration would be less than abso

lute. ’ ’

The decision here is at war with these state authorities.

Since under Kentucky law, respondent can only act for and

through the Department of Public Parks, its action in the

instant case is bound by the requirements of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

In holding to the contrary, the court below committed

fundamental error. Determination as to whether respond

ent’s action is private or state in character presents a

substantial federal question which this Court should deter

mine for itself. Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73, 88-89. For

these reasons, we respectfully submit, this petition should

be granted.

3. Decisions among state and lower federal courts with

respect to the status of leasing arrangements between

municipalities and private organizations are in conflict and

should be resolved.

The central constitutional problem here presented is to

distinguish private action from public action. The Four

teenth Amendment has foreclosed, at least as a constitu

tional issue, discriminatory action by public authority.

The difficulty in thinking of any private rights independent

15

of recognition and protection by government indicates that

“ public” and “ private” are not separate compartments but

titles for opposing' ends of a continuous spectrum.18 This

Court has already faced the problem of isolating unconsti

tutional public discrimination in the primary cases, Terry v.

Adams, — U. S, —, 21 U. S. L. Week 4346 (May 4, 1953);

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649; United, States v. Classic,

313 U. S. 299; Nixon v. Condon, 286 U. S. 73; Grovey v.

Townsend, 295 O’. 8. 45; Nixon v. Herndon, 263 O. S. 536;

see Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (C. A. 4th 1947), cert,

denied 333 U. S. 875; the restrictive covenant cases, Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 O. S. 1; and the railway labor cases, Steele

v. Louisville d Nashville R. R. Co., 323 U. S. 192; Tunstall

v. Rrotherhood of Locomotive Fireman, 323 U. S. 210. The

Fourth Circuit was also faced with the same problem in

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 149 F. 2d 212 (C. A. 4th

1945), cert, denied 326 U. 8. 721. In petitioner’s opinion,

the court below in the instant case has misconceived the

thrust of these decisions and thus ignores the pith of the

matter here involved.

In the absence of a definitive decision by this Court,

considerable confusion exists among lower federal and

state appellate courts as to where to draw the line between

“ public” and “ private” action where a public agency owns

and a private organization operates a recreational facility

pursuant to a leasing arrangement. Compare Lawrence

v. Hancock, supra, with the instant case; Culver v. City

of Warren, 84 Ohio App. 373, 83 N. E. 2d 82 (1948), and

Kern v. City Commissioners, 151 Kans. 565, 100- P. 2d

709 (1940) with Harris v. City of St. Louis, 233 Mo. App.

911, 111 S. W. 2d 995 (1938) and Modern Amusements, Inc.

v. New Orleans Public Service, 183 La. 848, 165 So. 137

(1935).

18 Barnett, What is State Action Under the Fourteenth, Fifteenth,

and Nineteenth Amendments of the Constitution?, 24 Ore L Rev

227, 229-30 (1945).

16

Since doctrinally the discriminatory action has to he

that of the state in order to bring the broad constitutional

prohibition into play, the question which arises here is

what circumstances are to be deemed sufficient to give rise

to state action. In Lawrence v. Hancock, supra, there was

involved a lease of a city owned and constructed swimming

pool to a private corporation which paid no rent, received

no profits and had to maintain the facility. The court

held that the lessee’s exclusion of Negroes was unconsti

tutional state action. The Kern and Culver cases, supra,

also involving publicly-owned swimming pools, both held

that the leasing arrangement did not divest the facilities

of their public characteristics. In the former case, the

lease established the hours when the pool was to be oper

ated, set the admissions charges, and required the lessee

to pay an annual rental of $1,000. In the latter case, the

contract required the City to maintain the pool and the

lessee to pay over 10% of the gross profits as rent.

Contrary holdings, however, resulted in the Harris and

Modern Amusements cases, supra,. In the Harris case, a

municipal auditorium and community center was leased to

various private groups. Negroes, however, were restricted

to a segregated section in the balcony by one private lessor

who almost exclusively pre-empted the use of the audi

torium for a series of musical and dramatic presentations.

The City reserved the right of revocation, control, manage

ment, and the power to establish charges and enforce all

necessary rules for the operation of the facility. The court

held that the City had a legal right to let the facility and

permit the lessee to regulate the admission policy because

the City, in such instance, acts not in its governmental

capacity but rather in a quasi-private capacity free of

constitutional limitations.

The Modern Amusements case developed out of a lease

of a city-owned stadium to a private corporation under an

agreement whereby the lessee covenanted not to operate it

17

in an objectionable or offensive manner. When the City-

terminated the lease after the lessee permitted a game

between Negro teams to be played on the premises and the

lessee sought to recover for breach of the lease on the

ground that the City’s action constituted unconstitutional

racial discrimination, the court ruled that the agreement

was a private contract to which the Fourteenth Amendment

did not extend.

In the instant case, the decisions below were bottomed

on the Harris case, supra. While cognizance was appar

ently taken of the indicia of state action surrounding the

construction of the Amphitheatre and reserved in the leas

ing contracts, crucial weight was placed upon the fact that

respondent is a private association which assumed all finan

cial risks arising incidental to its use of the facility. Thus,

the court held that respondent was not a governmental

agency and could discriminate against petitioner without

constitutional restriction.

In sum, the courts which have regarded leasing agree

ments as mere private contracts entered into by city govern

ments in their quasi-proprietary capacity have upheld the

racial discriminatory policies and practices of private

lessees. On the other hand, those courts which have stressed

the public dedication of the leased premises, the vestiture

of ownership, and the various indicia of governmental con

trol retained in the agreement, have viewed lessees as gov

ernmental instrumentalities managing the leased premises

under a contract entered into by municipalities in their

trusteeship capacity. Therefore, petitioner urges this Court

to grant certiorari in order to resolve this conflict and set

appropriate standards by which lower courts should be

guided in this area.

18

4. The decision below is in conflict with principles estab

lished in decisions of this Court, particularly Nixon v.

Herndon.

While petitioner was refused admission to Iroquois

Amphitheater by respondent because of his race and color

(R. 19), respondent in fact did not have the power to freely

determine its own admission policy. The Amphitheatre is

located in a park which the Department of Parks and

Recreation has set aside for the exclusive use of white

persons (R. 44). The authority of the City to promulgate

rules and regulations assigning certain parks exclusively

to Negroes and others to white persons was sustained by

the Court of Appeals of Kentucky in Warley v. Board of

Park Commissioners, 233 Ky. 688, 26 8. W. 2d 554 (1930).

It is admitted that Negroes were denied admission to parks

set aside for the exclusive use of white citizens solely on

account of their race (R. 43). To view respondent’s action,

therefore, as the independent action of a private person, as

did the court below, is to distort facts.

Petitioner was in truth denied admission to the Iroquois

Amphitheatre pursuant to state regulations and in conform

ity to state law. Under the City’s rules only white persons

were entitled to use Iroquois Park. Thus petitioner, in

going into the Park in his attempt to attend the perform

ance at the Amphitheatre, actually violated the City’s regu

lations. In the absence of state law, respondent had no

authority or power to refuse admission to any law-abiding

citizen who tendered the requisite admission fee. See Park

Commissioners of Ashland v. ShamMin, supra; Board of

Park Commissioners v. Speed, supra.

Indeed, it would seem clear that had respondent arbi

trarily refused admission to a white person, it would have

breached the agreement between it and the City, for the

entire purpose of the agreement as expressed therein is to

19

bring about an increased use of Iroquois Park by making

entertainment at the Amphitheatre available to the public

at low cost (R. 75, 76, 77). An affirmative duty is thus placed

on respondent to admit all white members of the public.

And it is only by virtue of the City’s regulations and state

court decisions upholding the City’s right to maintain segre

gated parks that respondent had the authority to deny

petitioner admission to the Amphitheatre. Of. Public Utili

ties Commission of the District of Columbia v. Pollack, 343

U. S. 451.

Since respondent here was in fact enforcing state law,

it was the state’s regulations which prevented petitioner’s

admission. To this extent respondent was acting for the

state and under color of state law, and its action is there

fore subject to the restraints of the Fourteenth Amendment

under principles enunciated by this Court in Nixon v.

Herndon, supra. See also Nash v. Air Terminal Services,

supra.

The Fourteenth Amendment imposes a duty on the City

to make public park property available to all persons with

out discrimination based upon race and color. Since the

Amphitheatre was a unique piece of public property, exclu

sion therefrom of Negroes pursuant to state authority was

clearly an unconstitutional act. See Missouri ex rel. Caines

v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337; Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332

U. S. 631; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629; McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637.

It is clear that the Department of Public Parks could

not present entertainment at the Amphitheatre under its

exclusive auspices and deny petitioner’s admission. Nor,

we submit, can the requirements of the 14th Amendment be

avoided by leasing the site to respondent subject to City

regulations limiting use of the park to white persons.

The decision of the court below in holding respondent’s

action to be private action free of constitutional limitations

20

is in fatal conflict with principles settled by this Court in

Nixon v. Herndon, swpra. We respectfully submit that

this Court grant this petition in order that this conflict be

resolved.

5. The decision in this case is in conflict with the prin

ciples enunciated by this Court in Nixon v. Condon, Smith v.

Allright and Terry v. Adams with respect to the delega

tion of state authority.

Under applicable Kentucky statutes, the title to Iroquois

Amphitheatre is held by the City, ‘ ‘ in strict and inviolable

trust” for public park purposes.19 The Department of

Public Parks and Recreation is entrusted with the care,

management, and custody of all park grounds used fox-

park purposes.20 Board of Park Commissioners of Ash

land v. Shanklin, supra; Board of Park Commissioners v.

Speed, supra.

The record reveals that the City here looked upon the

arrangement not as a lease of property held in its quasi

proprietary capacity, cf. Harris v. City of St. Louis, supra,

but as a method of carrying out its statutory duty to man

age the City parks for the public good. The agreements

between the City and respondent highlight this intention.

The first agreement of lease, entered into just prior to the

construction of the Amphitheatre, recites that the Park

Board of the City of Louisville is of the opinion that “ the

construction of an outdoor amphitheatre, suitable for the

production of musical, dramatic, operatic, and other forms

of exxteiTainment, out-of-doors, in Iroquois Park, would

greatly increase the recreational facilities available to the

19 Ky. Rev. Stat., § 97.252 (1948). See Appendix B. Cf. Hague

v. Congress oj Industrial Organization, 307 U. S. 496, 514.

20 Ky. Rev. Stat. § 97.290 (Baldwin’s certified ed., 1942) as incor

porated into Ky. Rev. Stat., § 97.250 (1948). See Appendix B.

21

public in said Park, and the use and enjoyment of said

Park by the Public * * * ” (E. 62-63). All agreements

require that admission fees and charges be reasonable so

as to “ increase the use of Iroquois Park by making the

entertainment presented at said Amphitheatre available

to the public at low cost” (R. 66, 75-76, App. B). These

provisions thus manifest the intention of the City to trans

fer to respondent the performance of a governmental func

tion.

In Nixon v. Condon, Smith v. Allright and Terry v.

Adams, this Court was faced with instances of delegation

of a governmental function fundamentally similar to that

in the instant case. In Nixon v. Condon, a state statute

granted to the executive committee of each political party

the power to prescribe the qualifications of its members.

This Court held that the refusal of the election judges to

permit petitioner to vote in a primary election was violative

of his rights under the Fourteenth Amendment, because

“ [delegates of the State’s power have discharged their

official functions in such a way as to discriminate invidi

ously between white citizens and black.” at page 89. A

strict principal-agency test in the determination of state

action was there expressly rejected.

While the delegation of state authority in Smith v. All-

right was not as clear-cut, this Court found such delega

tion in “ the duties imposed upon [the party] by state

statutes.” More recently, in Terry v. Adams where the

picture was even more blurred,21 again this Court found

state action. Mr. Justice Clark, concurring, speaking for

three other members of this Court, expressed the guiding

principle succinctly in these words:

“ Accordingly, when a state structures its elec

toral apparatus in a form which devolves upon a

21 See Rice v. Elmore, supra; Baskin v. Brown, 174 F 2d 391

(C. A. 4th 1949).

2 2

political organization the uncontested choice of pub

lic officials, that organization itself, in whatever dis

guise, takes on those attributes of government which

draw the Constitution’s safeguards into play.”

— U. S. —, 21 U. S. L. Week at 4351.

The principal-agency test for determining state action

was again repudiated, Mr. Justice Black stating:

“ It is immaterial that the state does not control

that part of this elective process which it leaves for

the Jaybirds to manage.” —• U. S. —, 21 U. S. L.

Week at 4349.

The decisions in the above cases are of course limited

to the field of primary elections. But the general principles

involved cannot be so narrowly restricted, for the philoso

phy of state action upon which these decisions rest is an

all-pervasive one. If the state allows the performance of

a governmental function to devolve upon a private organi

zation, that organization assumes those attributes of gov

ernment which bring the constitutional safeguards into

play.

Indeed, state and lower federal courts have almost

invariably held that the principles underlying Nixon v.

Condon and Smith v. Allright are ones of general validity

and thus applicable to other areas of governmental activity.

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, supra (library); Nash

v, Air Terminal Services, supra (restaurant); Lawrence v.

Hancock, supra; Kernel. City Commissioners, supra; Culver

v. City of Warren, supra (swimming pool). See Dorsey v.

Stuyvescmt Town Corp., 299 N. Y. 512, 87 N. E. 2d 541

(1949), cert, denied 339 U. S. 981.22 But cf. Harris v. City

22 The New York Court of Appeals there stated, at page 532:

“ In a more recent series of cases, the federal courts have held

private groups subject to the constitutional restraints when

they perform functions of a governmental character in matters

of great public interest.”

23

of St. Louis, supra; Modern Amusements Inc. v. New

Orleans Public Service, supra.

In the Kerr case, the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit, expressly refusing* to be guided by technical prin

ciples of principal and agent, gave forceful recognition to

the proposition that the principles of Nixon v. Condon and

Smith v. Allright are applicable to any grant of state

power to a private organization for the performance of a

state function.

While the Nash case involves federal action rather than

state action, it is particularly illuminating. The defendant

there operated restaurants at Washington National Airport

as a concessionaire of the United States Government. In

holding that defendant was under a constitutional duty to

serve all persons without discrimination on account of race

or color, the court based its decision solely on the fact that

defendant had been granted authority to perform a govern

mental function. The heart of the court’s decision is stated

in these words at page 549:

“ In effect, the concessionaire here is conducting

the facility in the place and stead of the Federal

government. To conclude otherwise would overlook

not only the status and purpose of the airport, but

also the purpose of the concession. It is to provide

food and refreshment to the public in travel and to

complement the facilities offered by the United States

Government in support of air transportation # * *

we * * * hold its restaurants are too close, in origin

and purpose, to the functions of the public govern

ment to allow them the right to refuse service with

out good cause.”

The decision in the instant case departs from the gener

ally prevailing view. The basic conflict between the deci

sion below and the above cases makes this case one peeu-

24

liarly appropriate for review by this Court. In deciding

that the acts of respondent did not constitute state action,

the court below, in effect, reverted to traditional principles

of agency law as the single standard—a test rejected by

this Court in the primary election cases and generally

abandoned by other courts in other areas of governmental

activity.

The factual differences between the primary election

cases and the instant one should not be allowed to blur the

fundamental oneness of the problems involved. Of course,

there is hardly any duty on a municipality to acquire land

for park purposes or to invest public funds in the construc

tion of a public amphitheatre thereon. Nevertheless, once

the City of Louisville here acquired Iroquois Park and con

structed the Amphitheatre, there developed upon the Direc

tor of Parks and Recreation the statutory duty to manage

the Amphitheatre for public park purposes. Thus, the

delegation of governmental authority here is of the same

nature as that in Nixon v. Condon, Smith v. AUright, and

Terry v. Adams.

It is respectfully submitted that this Court grant this

petition in order to resolve the conflict between the decision

below and the principles enunciated by this Court in the

primary election cases.

6. The decision of the Court below conflicts with well-

settled doctrine of this Court that rights guaranteed under

the 14th Amendment are personal and present.

The district court placed considerable emphasis upon

the fact that neither petitioner nor any organization to

which he belonged had sought to secure possession of the

Amphitheatre for the purpose of providing entertainment

procured and paid for by them without expense to the City.

What the court was in effect stating is that if a sufficient

number of Negroes were interested in supporting the pro-

25

duction of musical entertainment, then the City would be

obliged to allow them to use the Amphitheatre when it

wasn’t being used by respondent. Thus it conditions peti

tioners’ right to enjoy the recreational benefits available

to white persons at the Iriquois Amphitheatre on what may

or may not be done by other members of petitioner’s racial

group.

This Court has often reiterated that rights secured under

the 14th Amendment are personal and present and can

not be made dependent on what course of action other per

sons may take. See Sweatt v. Painter, 339, U. S. 629;

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1; McCabe v. Atchison,

T .S S. F. Ry. Co., 235 U. S. 151. In basing its decision on

the fact that there had been no showing that any Negro

group or organization had applied for permission to use

the Amphitheatre and had been refused, the court below

applied principles in basic conflict with a well-settled con

stitutional doctrine of this Court and committed fatal error.

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, for the reasons hereinabove stated,

it is respectfully submitted that this petition for writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

R obebt L. Cabter,

T hus,good Marshall,

Benjamin F. Shobe,

Counsel for Petitioner.

E lwood H. Chisolm,

David E. P insky,

of Counsel.

Dated: May 20, 1953.

26

APPENDIX A

Agreement

This AGREEMENT made and entered into this 5th day

of February, 1952, by and between the Department of Parks

and Recreation of the City of Louisville, Kentucky by its

Director, T. Byrne Morgan (hereinafter called the Depart

ment), and Louisville Park Theatrical Association (herein

after called The Association), a corporation having no

capital stock and from whose operations no private pecu

niary profit is derived,

Witnesseth That

W hereas, the purpose of the Association is to present

musical and theatrical entertainment in the City of Louis

ville at low cost and,

W hereas, The Department owns a structure, located in

Iroquois Park, known as Iroquois Amphitheatre which has

facilities suitable for use in presenting musical and theatri

cal entertainment, and

W hereas, The Association is desirous of using such

facilities for the presentation of its musical and theatrical

entertainments and The Department is desirous of having

The Association and other similar organizations use the

facilities of Iroquois Amphitheatre,

Now, T herefore, in consideration of the premises and

of the covenants and agreements hereinafter set out, the

said parties do hereby covenant and agree as follows:

1. The Department in consideration of the agreements

and covenants of the Association as hereinafter set out,

does hereby give and grant to the Association the exclusive

27

right and privilege to use said Iroquois Amphitheatre,

together with the equipment, buildings and land appur

tenant thereto, on such dates between June 14, 1952, and

August 23, 1952, as The Association may, by written notice

to the Department, designate; and agrees that it will not

lease, or give to any other person, firm or corporation the

right to use said Amphitheatre during* said period, without

having first obtained the written consent of The Association

thereto.

2. The Association shall have the right to use the

Amphitheatre on any, or all, of said dates, for the purposes

of rehearsing, and/or presenting, such musical, dramatic,

operatic, and other forms of entertainment, both amateur

and professional, as it may select; for the sale and service

on such occasions of such food, soft drinks, tobacco, cigars,

cigarettes, candy, programs, musical scores, etc., as are

customarily sold or offered for sale in similar places of

public entertainment and for the rendition of such other

services as are customarily rendered in such places, and

for no other purpose.

The Association shall have the right to produce the

entertainment, sell and serve the items, and render the

services aforesaid, itself, or to contract with any other

person, firm, or corporation, for the production of said

entertainments, the sale and service of said items, and the

rendition of said services or any of them.

3. The Association, or any person, firm or corporation

with whom The Association has contracted for the pro

duction of any entertainment at said Amphitheatre, shall

have the right to charge any person seeking to attend said

entertainment such admission fee as may be fixed by the

Board of Directors of the Association. Likewise, The

Association, or any person, firm or corporation with whom

it has contracted to furnish food, soft drinks, programs,

28

musical scores, etc., or to render said services as are cus

tomarily rendered in connection with - such entertainment,

shall have the right to charge such prices as may he

approved by the Board of Directors of The Association.

Provided, however, that such admission fees and charges

shall be reasonable and consistent with the desire of both

parties thereto to increase the use of Iroquois Amphi

theatre by making the entertainment presented at said

Amphitheatre available at low cost.

4. The Association agrees that it will not erect, or main

tain, any signs or advertisements, in, upon, or about the

Amphitheatre, except only such signs or advertisements,

as may with the approval of the Department be placed

thereon to advertise attractions to be presented at said

Amphitheatre, and as are contained in programs distrib

uted at any performance given in said Amphitheatre, and

agrees that the Department may remove, or obliterate, any

sign, or advertisement, erected or maintained by the Asso

ciation in violation of the Agreement.

5. The Department agrees that:

(a) It will turn over said Amphitheatre to The

Association, on June 14, 1952, in good order and repair

and in suitable condition for use by The Association;

(b) Furnish all water necessary to enable The Asso

ciation, or any person, firm or corporation with whom The

Association may have contracted, to produce the entertain

ment contemplated by this Agreement. The Association

is to pay all other utility bills during the period of its use

(June 14, 1952 to and including August 23, 1952) of said

Amphitheatre.

6. The Association agrees to pay to the Department

on or before August 23, 1952, the sum of One Thousand

($1,000.00) Dollars for the rights and privileges granted

29

to it by this Agreement in connection with the use of said

Amphitheatre, to re-imburse the Department for additional

expenses occasioned by this use.

7. The Association agrees that during the period of its

use of said Amphitheatre it will keep said premises in good

order and repair and at the expiration of its term of use

will return said premises to the Department in as good con

dition as reasonable and careful use will permit,

8. The Association shall have the exclusive right to

select, and agrees to assume full responsibility for employ

ing, fixing and the compensation of, and paying the salaries

and wages of, all artists, actors, musicians, ticket takers,

ushers, stage hands, and persons other than police, employed

in connection with the presentation of any entertainment

produced by, or under the auspices of, The Association at

said Amphitheatre.

9. The Association agrees that The Department shall

at all times have the right to make and enforce such reason

able rules and regulations as it deems necessary for the

preservation of said Amphitheatre and the equipment and

appurtenances thereto belonging, and for the preservation

of good order therein, and shall have the right to prohibit

the production at said Amphitheatre of any entertainment

which is, in the opinion of The Department or any other

department, indecent or immoral or calculated to create or

incite racial or religious antagonism or disturbance of the

public peace.

10. It is further mutually understood and agreed by

and between the parties hereto that The Association shall

have the right, at its option, to renew this Agreement on

the same terms and conditions and for the same or similar

period of time for the use of said Amphitheatre for the

30

Summer season of 1953. The Association must notify, in

writing, The Department of its election to renew the said

Agreement on or before October 1, 1952.

I n Testimony W hereof, the parties have caused their

corporate names to be subscribed and their corporate seals

to be affixed hereto, The Department of Parks and Recrea

tion, by its Director, and the Louisville Park Theatrical

Association by its President, all at Louisville, Kentucky,

the day and year first above mentioned.

T he City of L ouisville

By T. Byrne Morgan

Director of Parks and Recreation

L ouisville P ark T heatrical A ssociation

By: G. E. Gans

(Seal of City of Louisville)

Approved

Charles P. Farnsley

Mayor

I, Wm. D. Meyers, Director of Finance of the City of

Louisville, Kentucky, and by virtue of Kentucky Revised

Statutes Section 91.060, custodian of ordinances and records

of the City of Louisville do hereby certify that the fore

going is a full and true copy of an agreement of the City

of Louisville entered into the 5th day of February, 1952.

Wm. D. Myers

31

APPENDIX B

Statutes of Kentucky

Applicable to Parks In Cities of the First-Class

K entucky Revised Statutes (1948)

97.250 [2840; 2841; 2844; 2847] Powers of department of

public parks and recreation in first-class cities; employes;

director of parks and recreation. (1) The department of

public parks and recreation of any city of the first class

shall, from and after the effective date of KRS 97.250 to

97.258, be vested with and exercise all of the powers and

perform all of the functions and duties of any then existing

board of park commissioners of such city, except as may be

otherwise provided by law or by KRS 97.250 to 97.258,

From and after said date any such board of park commis

sioners of -such city shall cease to exist. The agents and

employes of said department of public parks and recrea

tion, except as provided herein, shall be employed and

governed in accordance with the merit system, as provided

by any law or laws, or amendments thereof, and any rules

and regulations issued pursuant thereto, authorizing, cre

ating and governing any city board or commission empow

ered to administer and enforce civil service laws, rules and

regulations in and for such city.

(2) The department of public parks and recreation of

any city of the first class shall be under the supervision and

direction of a director to be designated director of parks

and recreation, and shall have exclusive direction, super

vision and control of all park property, as herein defined,

except as otherwise provided by law or by KRS 97.250 to

97.258 or by ordinance of the legislative body of said city;

and shall provide for and supervise all public amusements

and recreation in parks, playgrounds, and community cen-

32

ters. The director of said department shall have power to

adopt rales and regulations for the reasonable and proper

use, management and control of public park, playground

and community center property, and may organize the said

department for administrative purposes into such divisions

as may be necessary for the proper conduct of the business

of said department, and appoint heads or chiefs of such

divisions, who, under the supervision and control of said

director, shall have the direction of such divisions. (1942,

c. 34, § 2) [Emphasis supplied.]

97.251 Definition of “ park property.” The term “ park

property” includes all parks, squares and areas of land

owned or used by said city for park purposes, and all build

ings, structures, improvements, seats, benches, fountains,

walks, drives, roads, trees, plants, herbage, flowers, and

other things thereon, and inclosures of the same; all shade

trees on streets or thoroughfares throughout park property

and said city; all resting places, watering stations, play

grounds, parade grounds, community centers, or the like;

all connecting parkways and roads or drives between parks,

and all avenues, roads, ways, drives, walks, with all trees,

shrubbery, vines, flowers and ornaments of any description

thereon, acquired for park purposes; and all birds, animals

or curiosities, or objects of interest or instruction placed in

or on any of such inclosures, ways, parkways, roads or

places; and said term shall be liberally construed. (1942,

c. 34, § 2)

97.252 Title to and control of park property; exemption

from taxation; use for streets; contracts for use of aviation

fields; control of public ways acquired for park purposes.

(1) The title to all property with all improvements and

equipment acquired for park, airport or aviation field pur

poses, owned by the board of park commissioners of a city

of the first class at the time KRS 97.250 to 97.258 become

effective, is hereby transferred to the city subject to any

33

existing leases thereof, and shall be held by the city in strict

and inviolable trust for such public purposes, free from all

taxation, imposts or assessments by state, county, district,

municipal, or other governmental subdivision; provided,

however, that the city may use any portion of such property

as may be necessary and proper for the construction, exten

sion, or widening of streets, boulevards, thoroughfares or

other public ways, and may enter into contracts or agree

ments, with reference to properties acquired for airport or

aviation field purposes, for the use of such field and airport

for aviation purposes, with the United States government

or any agency thereof, or any state government or any

agency thereof, or any board of aviation established under

any Act of the General Assembly of this Commonwealth,

or of any other commonwealth or state, or any individual,

firm or corporation; provided, however, it shall at no time

and in no way enter into any contract or agreement that

prevents its carrying out the main purpose of the establish

ment and maintenance of a public municipal aviation field

and airport, for the general use of the citizens of said city

as a park purpose. [Emphasis supplied.]

(2) Such park property as consists of all connecting

parkways and roads or drives between public parks, and all

avenues, roads, ways, drives and walks outside of the

boundaries of public parks, which were or are acquired for

park purposes, from and after the effective date of KRS

97.250 to 97.258, shall be under the direction, control, main

tenance and management of the department of public works

of said city. (1942, c. 34, § 2)

34

Pertinent Prior Statutes

K entucky R evised Statutes

(1942 Baldwin’s Certified Edition)

97.270 Powers and duties of board of park commissioners

in first class cities. (1) The board shall have the

care, management and custody of all parks and

grounds used for park purposes. . . .

# * #

Cabroll’s K entucky Statutes A nnotated

(Bald. Rev. 1936 ed.)

§ 2840. Board of park commissioners; controlled by.—The

public parks in a city of the first class shall be held,

managed and controlled by a board under the name

and style of the board of park commissioners.

-y. -y. -V.vr w vr

§ 2848. Powers and duties of commissioners.—The board,

constituted as aforesaid, shall have the care, man

agement and custody of all parks and grounds used

for park purposes. . . .

* * #