Novick v. Levitt & Sons, Inc. Reply Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1951

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Novick v. Levitt & Sons, Inc. Reply Brief of Appellants, 1951. 1d1ccc0e-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/e30a3e10-677b-429e-b9c0-7a4649666dc6/novick-v-levitt-sons-inc-reply-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

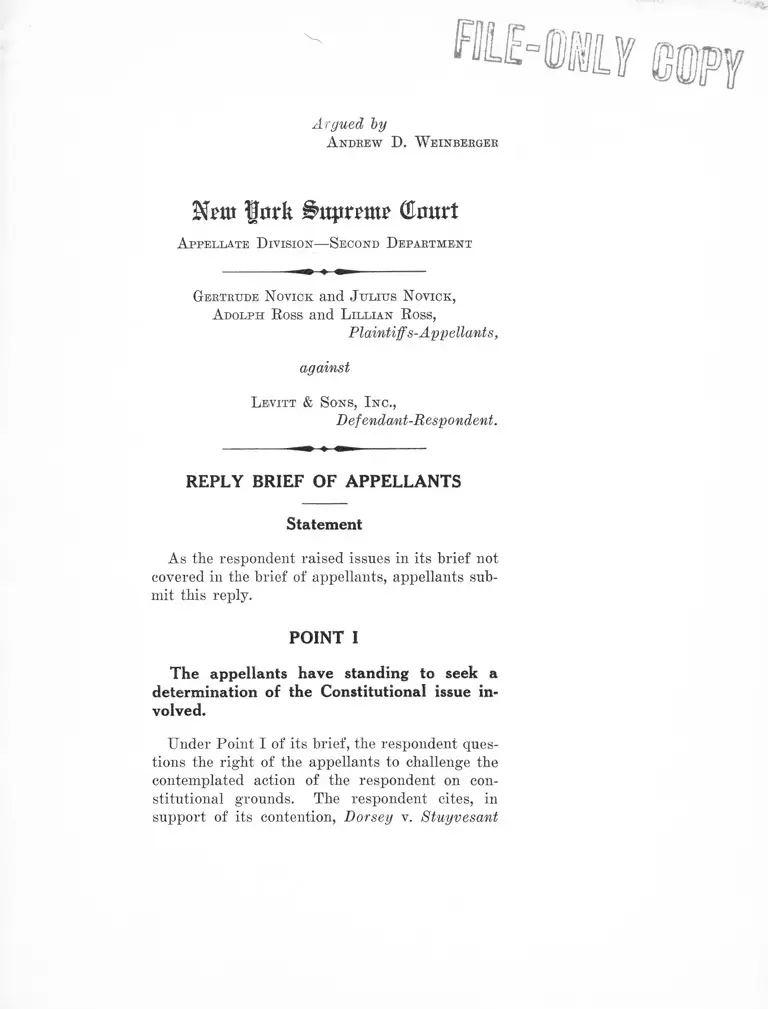

Argued by

A ndrew D. W einberger

f a fork Supreme (tart

A ppellate D ivision— Second Department

Gertrude Novick and J ulius Novice,

A dolph R oss and L illian R oss,

Plaintiff s-Appellants,

against

L evitt & Sons, I nc.,

Defendant-Respondent.

REPLY BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

Statement

As the respondent raised issues in its brief not

covered in the brief of appellants, appellants sub

mit this reply.

POINT I

The appellants have standing to seek a

determination of the Constitutional issue in

volved.

Under Point I of its brief, the respondent ques

tions the right of the appellants to challenge the

contemplated action of the respondent on con

stitutional grounds. The respondent cites, in

support of its contention, Dorsey v. Stuyvesant

2

Town Corporation, 299 N. Y. 512 (1949) wherein

the Court of Appeals of this state refused to hear

the case of a white taxpayer who brought an

action to enjoin the City of New York from enter

ing into a contract with the defendant Stuyvesant

Town Corporation. The Court refused to hear

the case on the ground that the taxpayer was not

a member of the class allegedly discriminated

against by the said corporation. In a separate

action, which the Court of Appeals heard, Negro

veterans, members of the class discriminated

against, sought to compel their admission to the

housing project to be built by said corporation

under contract with the City of New York on the

ground that the city had given such aid to the

corporation as to make the project developed by

it a city function. Unlike the appellants in this

case, who will be directly affected by the uncon

stitutional action contemplated by the respondent,

the taxpayer in Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Cor

poration, supra, was not in any way affected by

the unconstitutional discrimination alleged. If

the respondent in this case is allowed to proceed

to evict the appellants for the reason that the

appellants allowed Negro children to play with

their children in violation of the respondent’s

prohibition against the use of the premises by

persons other than Caucasians, then the appel

lants will be evicted from their home and denied

the right to have Negroes as guests by the action

of the state in violation of the prohibitions of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitu

tion.

In cases involving state court enforcement of

racial restrictive covenants, the challenge to the

validity of the action of the state in such cases

3

was not necessarily raised by the member of tbe

racial group discriminated against. On the con

trary, in most of those cases a party to the agree

ment sought the aid of the court to enjoin another

party to the agreement who sought to break the

agreement, and the constitutional issue was

raised by the party sought to be enjoined. In

Kemp v. Rubin, 297 N, Y. 955 (1948), plaintiffs,

Kemp and another, (both white persons) sought

to enjoin Sophie Rubin (also white) from selling

her property to a Negro, Richardson, in violation

of a restrictive covenant agreement to which

Sophie Rubin was a party. In their complaint,

the plaintiffs alleged:

“ 7. On information and belief that the

defendant Sophie Rubin has entered into

negotiations with persons of the Negro race

for the sale of the premises owned in fee by

her and known as 112-03 177th Street,

St. Albans, New York.

“ 8. On information and belief that the

defendant Sophie Rubin has made a contract

of sale with, and received a deposit from a

person or persons of the Negro race, for the

sale of the premises known as 112-03 177th

Street, St. Albans, New York.

“ 9. On information and belief that the

defendant Sophie Rubin intends to carry out

the negotiations for the sale of the premises

known as 112-03 177th Street, St. Albans,

New York, and to carry out the sale of said

premises to a person or persons of the Negro

race.

“ 10. That said sale of the said premises

112-03 177th Street, St. Albans, New York,

would be in violation of the agreement for

restrictive covenant duly recorded and men

tioned in paragraph 1 of this complaint, and

which the defendant Sophie Rubin duly

signed and is a party thereto.”

4

An injunction was issued against Sophie Rubin

by the Supreme Court of Queens County and af

firmed by the Appellate Division, Second Depart

ment. The order of the Supreme Court read in

part as follows:

‘ ‘ Ordered, adjudged and degreed that the

defendant Sophie Rubin be and she hereby

is permanently restrained and enjoined until

December 31, 1975, from permitting the use

or occupancy by, or selling, conveying, leas

ing, renting or giving to Samuel Richardson,

a Negro, or to any person or persons of the

Negro race, blood or descent the premises

112-03 177th Street, St. Albans, New York,

* # *

The person discriminated against because of

race and color in that case was not Sophie Rubin,

who was white, but Richardson, a third party who

was a Negro. However, the constitutional issue

whether the Court could, consistent with the

Fourteenth Amendment, enjoin violation of the

agreement and thus give force and effect to same,

was raised by Sophie Rubin. Therefore, it is

clear that the constitutional issue in cases in

volving the use of state power to give force and

effect to private discrimination need not be raised

by persons who would be discriminated against

because of race and color by the action of the

state, but may be raised by one who is in the

position of the appellants in this case, that is, by

a person who seeks to sell his house to a Negro

in violation of a restrictive covenant as in the

case of Kemp v. Rubin-, supra, or by a tenant who

seeks to entertain Negro children in violation of

a prohibition against the use of leased premises

by persons other than Caucasians.

5

In the restrictive covenant cases, the respond

ent contends, unlike this case, there was a willing

buyer and a willing seller. In this case, the ap

pellants are willing to invite Negroes as guests

and the Negroes are willing to accept this invita

tion. The respondent would seek to invoke its

prohibition to prevent the appellants from ex

tending the invitation and to prevent the Negroes

from accepting. However, the respondent’s pro

hibition in this situation would be of no effect

without invoking the “ full coercive power of the

state.” In the restrictive covenant cases, there

was a willing seller and a willing buyer. A third

party sought to intervene to prevent the seller

from selling his property and the buyer from

buying the property in violation of an agreement

between the third party and the seller. The third

party’s interference wTas without force and effect

until the “ full coercive power of the state” was

invoked. Shelley v. Kraemer and Sipes v. Mc

Ghee, 334 U. S. 1.

POINT II

A tenant has a constitutionally protected

right to have in his home Negroes as guests

without the interference of the state which

has been invoked by the landlord to give

effect to the landlord’s prohibition against

such action on the part of the tenant.

Contrary to the contention of the respondent

herein, the appellants do not seek in this action

to have their lease renewed. Neither do the ap

pellants seek to have the respondent accept Ne

groes as tenants. Therefore, Dorsey v. Stuyve-

6

sard Town Corporation, supra, upon which the

respondent relies, is completely inapplicable to

this case. The appellants herein rightfully gained

possession of the respondent’s premises. The

only question which they raise in this action is

whether they may be evicted for the sole reason

that they violated the respondent’s prohibition

against the use of the premises by persons other

than Caucasians. In other words, the appellants

question the respondent’s right to the aid of the

state to evict them for a reason which will result

in unconstitutional discrimination against third

persons.

In Shelley v. Kraemer and Sipes v. McGhee,

supra, the United States Supreme Court specifi

cally said at page 22:

“ The Constitution confers upon no indi

vidual the right to demand action by the

state which results in a denial of equal pro

tection of the laws to other individuals. And

it would appear beyond question that the

power of the state to create and enforce prop

erty interests must be exercised within the

boundaries defined by the Fourteenth Amend

ment. ’ ’

This portion of the United States Supreme

Court’s decision in the restrictive covenant cases

is omitted from the brief of the respondent here

in. It is omitted from their brief for the plain

reason that it is the essence of the appellant’s

case. This language is without equivocation. It

means that the landlord in this case does not have

the right to invoke the aid of a court to evict the

tenants for the reason alleged.

The Court said further something else which is

specifically applicable to this case and to which

7

the respondent does not refer for the simple rea

son that the language is clearly determinative of

the issue here. The Court said at page 20, refer

ring to the Fourteenth Amendment:

“ Nor is the Amendment ineffective simply

because the particular pattern of discrimina

tion, which the state has enforced, was initi

ally defined by the terms of a private agree

ment. ’ ’

The tenants therefore have a constitutionally pro

tected right to have in their homes Negroes as

guests without the interference of the state which

has been invoked by the landlord to give effect

to his private prejudices as such action on the

part of the state would result in a denial of the

equal protection of the laws to other individuals.

The appellants do not deny that the Court said,

as pointed out by the respondent in its brief at

page 13:

“ That Amendment erects no shield against

merely private conduct however discrimina

tory or wrongful.”

But this is not where the Court stopped as re

spondent would like to believe. What the Court

held was that the Amendment erects no shield

against merely private conduct which is discrim

inatory where there is no necessity for invoking

the aid of the state to give effect to such conduct,

but where it is necessary to invoke the aid of the

state to give effect to such conduct, then the Four

teenth Amendment is effective. The appellants

stated at the bottom of page 8 of their brief:

“ It may be true that the respondent in this

case has the right under the law of this state

to let its property to whomever it chooses

8

and the appellants in the instant case do not

question that right in this action.”

This statement is made by the appellants for the

reason that appellants recognize that in refusing

to rent to Negroes it is not necessary for the

respondent to invoke the aid of the state to give

effect to this discriminatory policy. The respond

ent says on page 9 of its brief, if A and B may

agree not to sell (or rent) to C because of his

color, then, a fortiori, A may alone decide that he

will not so sell (or rent). This is obviously true,

and the restrictive covenant cases, Shelley v.

Kraemer and Sipes v. McGhee, supra, so stated.

But this was not the issue or the holding in those

cases, nor is it the issue raised in this case. The

issue raised in those cases and in this case is

whether the power of the state might be invoked

to give effect to such agreement (or decision).

The Court held specifically that the aid of the

state could not be invoked to give effect to the

agreement between A and B. A fortiori, the aid

of the state could not be invoked to give effect

to the decision of A alone that he will not sell (or

rent) to C because of his color.

POINT III

Courts may appropriately withhold their

aid where one seeking to assert an otherwise

valid right is motivated by a bad purpose.

The respondent in its brief disposes of the pub

lic policy argument advanced by the appellants

in their brief by referring to the fact that in

Dorsey v. Stuyvesant Town Corporation, supra,

(which is not in any way determinative of the

9

issue raised in this case, as pointed out above),

the Court of Appeals did not regard the statutes

cited by the appellants in their brief as directing

the Court to the public policy of the State of New

York. In the case which is determinative of the

issue raised in the instant case, Kemp v. Rubin,

supra, these statutes were brought to the atten

tion of the Court of Appeals, and although the

Court of Appeals merely reversed, citing Shelley

v. Kraemer and Sipes v. McGhee, it did not reject

the argument made by the appellants in that case

that these statutes indicate that the public policy

of the State of New York is contrary to judicial

enforcement of private discrimination.

If the statutes cited by the appellants in their

brief are not sufficient to demonstrate that the

public policy of the State of New York is opposed

to judicial enforcement of private discrimination,

then it should be sufficient that there is a general

principle of law that the courts may appropri

ately withhold their aid where the plaintiff is

using the right asserted contrary to the public

interest. Morton Salt Co. v. G. S. Suppliger Co.,

314 U. S. 488 (1941); Rehearing denied 315 U. S.

826 (1941). Virginian R. Co. v. System Federa

tion, R. E. I)., 300 IT. S. 515, 552; Central Ken

tucky Natural Gas Co. v. Railroad Commission,

290 U. S. 264, 270-273; Harrisonville v. W. S.

Dickey Mfg. Clay Co., 289 IT. S. 334, 337, 338;

Beasley v. Texas $ P. R. Co., 191 U. S. 492, 497;

Securities & Exch. Commission v. United States

Realty & Improv. Co., 310 U. S. 434, 455; United

States v. Morgan, 307 IT. S. 183, 194. In other

words, relief may be denied by reason of the fact

that the plaintiff in instituting suit has been in

fluenced by bad motives. 19 Am. Jur. Section 479.

10

Here the respondent admits that its otherwise

perfect right to evict the appellants herein is

motivated hy the fact that the appellants invited

Negro children to play with their children on the

respondent’s premises. In short, the respondent

admits that its motive is bad, yet the respondent

brazenly seeks the aid of a court of the state to

give effect to such a bad motive. As the cases

above cited held, where this is true the courts in

the interest of the public should refrain from

aiding the person who is motivated by such bad

purpose.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert L. Carter,

Constance B aker Motley,

J ack Greenberg and

A ndrew D. W einberger,

Attorneys for Appellants.

(4235)

J udicial Printing Co., Inc. 182

32 B eekman St ., New Y ork 7, N. Y . - - - BEekman 3— 9084-5-6